Abstract

目的

探讨儿童青少年抑郁、社交焦虑的现状,并分析儿童青少年脂肪分布与抑郁和社交焦虑的关联。

方法

采取分层整群随机抽样法纳入北京市7~18岁儿童青少年1 412名,使用双能X线吸收法获得其脂肪分布,使用儿童抑郁量表和儿童社交焦虑量表评价其抑郁和社交焦虑情况,采用多元线性回归和限制性立方样条分析估计儿童青少年脂肪分布与其抑郁、社交焦虑的线性与非线性关联。

结果

13.1%和31.1%的儿童青少年分别存在抑郁症状和社交焦虑症状,且男生、低年龄组的抑郁和社交焦虑检出率显著低于女生、高年龄组。儿童青少年的总脂肪率、Android脂肪率、Gynoid脂肪率、Android与Gynoid脂肪比(Android-to-Gynoid fat ratio,AOI)与抑郁和社交焦虑不存在显著性线性关联,但总脂肪率和Gynoid脂肪率与抑郁的非线性关联显著,表现为倒“U”型曲线关系,切点分别为26.8%和30.9%。脂肪分布与抑郁、社交焦虑的关联在不同性别和高低年龄组间差异不存在统计学意义。

结论

儿童青少年的脂肪分布与抑郁和社交焦虑不存在显著性线性关联; 脂肪分布与抑郁呈现倒“U”型曲线,主要表现在总脂肪率和Gynoid脂肪率上,且这种趋势在不同性别和不同年龄组上均表现出一致性。将儿童青少年的脂肪分布维持在一个合适的水平,是未来儿童青少年抑郁、社交焦虑防控关注的方向。

Keywords: 抑郁, 社交焦虑, 体脂分布, 限制性立方样条

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the status of depression and social anxiety in children and adolescents, and to analyze the association between body fat distribution and depression, social anxiety in children and adolescents.

Methods

A total of 1 412 children aged 7 to 18 years in Beijing were included by stratified cluster random sampling method. Body fat distribution, including total body fat percentage (total BF%), Android BF%, Gynoid BF% and Android-to-Gynoid fat ratio (AOI), were obtained by dual-energy X-ray absorption method. Depression and social anxiety were evaluated by Children Depression Inventory and Social Anxiety Scale for Children. Multivariate linear regression and restricted cubic spline analysis were used to estimate the linear and non-linear correlation between body fat distribution and depression and social anxiety.

Results

13.1% and 31.1% of the children and adolescents had depressive symptoms and social anxiety symptoms respectively, and the detection rate of depression and social anxiety in the boys and young groups was significantly lower than those in the girls and old groups. There was no significant linear correlation between total BF%, Android BF%, Gynoid BF%, AOI and depression and social anxiety in the children and adolescents. However, total BF% and Gynoid BF% had significant nonlinear correlation with depression, showing an inverted U-shaped curve relationship with the tangent points of 26.8% and 30.9%, respectively. In terms of the nonlinear association of total BF%, Android BF%, Gynoid BF% and AOI with depression and social anxiety, the change trends of the boys and girls, low age group and high age group were consistent. The overall anxiety risk HR of body fat distribution in the boys was significantly higher than that in the girls, and the risk HR of depression and social anxiety were significantly higher in the high age group than those in the low age group.

Conclusion

There was no significant linear correlation between body fat distribution and depression and social anxiety in children and adolescents. Total BF% and depression showed an inverted U-shaped curve, mainly manifested in Gynoid BF%, and this trend was consistent in different genders and different age groups. Maintaining children and adolescents' body fat distribution at an appropriate level is the future direction of the prevention and control of depression and social anxiety in children and adolescents.

Keywords: Depression, Social anxiety, Body fat distribution, Restrictive cubic splines

抑郁和社交焦虑是常见的精神障碍,其患病率在全球范围内呈上升趋势[1],是中国儿童青少年生长发育中的一个重要问题[2],严重危害着儿童青少年的健康成长[3]。多项研究表明,肥胖与社交焦虑和抑郁之间存在关联[4-5],与正常体质量的同龄人相比,肥胖儿童更有可能经历抑郁和社交焦虑[6-7]。

体重指数(body mass index,BMI)是国际公认的超重肥胖评价标准[8],我国也推出了基于中国儿童青少年群体参考值建立的BMI卫生行业标准[9],但由于BMI不能区分人体的脂肪成分和非脂肪成分,以BMI作为肥胖的评价标准会忽视体脂率过高导致的脂肪聚积问题[10-11]。一项针对18岁以下儿童青少年肥胖研究的元分析结果显示,BMI对过度肥胖的检测特异性高、敏感性低,有超过25%的体脂率过高的儿童青少年未被识别出来[10]。

双能X线吸收法(dualenergy X-ray absorptiometry,DXA)是测量身体成分的金标准,其可以得到全身和局部身体成分含量,具有很高的稳定性和可重复性[12]。儿童青少年正处于身体发育和脂肪分布变化的关键时期,尤其是青春期。因此,研究儿童青少年身体成分与心理障碍的关系,对社交焦虑、抑郁的精准干预具有重要意义。本研究将通过DXA测量中国儿童青少年的脂肪分布,并探究其与抑郁和社交焦虑之间的关联。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 研究对象

于2020年9—12月选取北京市一所小学、一所初中和一所高中的所有班级,采用分层整群随机抽样的方法抽取每个班级的部分学生进行横断面调查,纳入在父母陪同下自愿完成全部体检的7~18岁儿童青少年,排除近期手术、身体发育缺陷及身体内安置金属医疗器械者(如心脏起搏器、金属钢钉等)。最终样本包含1 412名儿童青少年,其中716名(50.71%)为男生。

本研究已经获得北京大学生物医学伦理委员会审查批准(批准号为IRB00001052-20024)。研究开始前向所有儿童青少年及其家长详细介绍项目的研究目的和内容,并由学生和家长签署书面知情同意书。体检前将问卷分发给学生和家长,小学三年级及以下的学生在监护人的协助下完成问卷,体检当天回收问卷。

1.2. 指标与方法

1.2.1. 身高与体质量

体格检查由经过培训的调查员严格按照“中国学生体质与健康调研”的操作规范进行。身高测量使用统一校准的机械式体尺(TZG型,中国江苏省江阴市第二医疗设备厂,精确度0.1 cm),要求受试者赤足,自然站立。体质量使用统一校准的电子秤(RGT-140型,上海大川电子衡器有限公司,精确度0.1 kg),要求受试者赤足,仅着轻薄衣物。身高和体质量均测量两次,计算平均值。BMI的计算方法为体质量(kg)除以身高(m)的平方。

1.2.2. 脂肪分布

由专业医务人员使用双能X线骨密度仪(GE lunar prodigy)扫描全身并收集图像,以获得全身及局部脂肪质量。受试者按要求平躺在扫描床上,身体置于仪器中间,拇指朝上,手掌面向但不接触腿部。每个受试者测量5~7 min。总脂肪率(total body fat precentage,BF%)为全身脂肪质量/体质量。Android区域是腰椎中点和骨盆顶部之间的腰部区域,通常被用于表示腹部区域; Android区域脂肪率(Android BF%)为Android区域脂肪质量/体质量。Gynoid区域位于股骨头和大腿中部之间,通常被用于表示臀部区域; Gynoid区域脂肪率(Gynoid BF%)为Gynoid区域脂肪质量/体质量。腰臀脂肪比(Android-to-Gynoid fat ratio,AOI)为Android区域脂肪质量/Gynoid区域脂肪质量,是身体脂肪分布或中心性肥胖的主要指标[13-14]。

1.2.3. 抑郁和社交焦虑

抑郁症状由儿童抑郁量表(children’s depression inventory,CDI)测量[15],其包括5个分量表(消极情绪、人际问题、低效能、快感缺乏和消极自尊),共27个项目(每个项目的编码为:0,无症状; 1,有症状且轻微; 2,可能的最高严重程度),其中13个项目为反向编码; 计算所有项目的总分(均值为10.54,标准差为6.39),得分越高代表其抑郁症状程度越高。本研究中CDI总量表的Cronbach’s α系数为0.87,参考前人研究[16],将CDI评分≥19定义为抑郁。社交焦虑采用儿童社交焦虑量表(social anxiety scale for children,SAS-C)[17]进行测量,主要考察消极评价恐惧、社会回避两个维度,共10个项目,每个项目的编码采用三点计分(0,从不; 1,有时; 2,经常); 计算所有项目总分(均值为5.14,标准差为3.89),得分越高表明个体的社交焦虑程度越高。本研究中SAS-C总量表Cronbach’s α系数为0.85,将SAS-C评分≥8定义为存在社交焦虑。

1.3. 质量控制

项目开始前对全部工作人员进行培训,包括项目流程和检测内容、检测仪器的使用方法和注意事项等。现场调查中使用的所有仪器每日使用前均经过校准以确保测量的准确性,数据录入采用双盲模式,并且及时进行逻辑检查以保证数据录入质量。

1.4. 统计方法

采用R 4.2.2进行数据分析。连续变量用均值±标准差表示,采用独立样本t检验进行差异性检验; 分类变量用频率表示,采用卡方检验进行差异性检验。在控制了性别、年龄、体质量、身高和BMI后,采用多元线性回归模型分析儿童青少年的脂肪分布与抑郁、社交焦虑之间的关系; 采用限制性立方样条(restricted cubic spline,RCS; 设置为4个节点)拟合多元线性回归模型分析脂肪分布与儿童青少年抑郁、社交焦虑之间的非线性关系,并进行可视化。

2. 结果

2.1. 研究对象的基本情况

如表 1所示,男生的平均身高显著高于女生[(158.24±17.09) cm vs.(152.33±13.27) cm,t=7.26,P < 0.001],平均体质量亦显著高于女生[(53.98±19.99) kg vs. (43.60±16.15) kg,t=5.57,P < 0.001],但两者的BMI差异无统计学意义(t=1.71,P=0.088)。此外,7~12岁儿童的BMI显著低于13~18岁青少年[(18.67±3.79) kg/m2 vs. (22.51±4.76) kg/m2,t=-16.80,P < 0.001]。

表 1.

研究对象的基本情况

Baseline characteristics of included population

| Items | Total | Gender | Age group | |||||||

| Boys | Girls | t | P | 7-12 years | 13-18 years | t | P | |||

| Data are expressed as n, n(%) or x±s. BMI, body mass index; BF%, total body fat precent; AOI, Android-to-Gynoid fat ratio; CDI, children’s depression inventory; SAS-C, social anxiety scale for children. | ||||||||||

| Sample size | 1 412 | 716 | 696 | 688 | 724 | |||||

| Age/years | 11.93±3.60 | 12.43±3.35 | 12.35±3.29 | 9.46±1.7 | 15.18±1.66 | |||||

| Height/cm | 152.77±17.57 | 158.24±17.09 | 152.33±13.27 | 7.26 | < 0.001 | 142.49±11.07 | 167.53±7.26 | -49.97 | < 0.001 | |

| Weight/kg | 49.33±19.09 | 53.98±19.99 | 43.60±16.15 | 5.57 | < 0.001 | 38.63±11.82 | 63.39±15.06 | -34.45 | < 0.001 | |

| BMI/(kg/m2) | 20.34±4.72 | 20.85±4.78 | 20.42±4.65 | 1.71 | 0.088 | 18.67±3.79 | 22.51±4.76 | -16.80 | < 0.001 | |

| Body composition | ||||||||||

| BF% | 0.29±0.08 | 0.26±0.09 | 0.32±0.07 | -12.92 | < 0.001 | 0.30±0.07 | 0.28±0.09 | 4.62 | < 0.001 | |

| Android BF% | 0.28±0.12 | 0.26±0.13 | 0.30±0.11 | -7.03 | < 0.001 | 0.28±0.11 | 0.28±0.12 | -0.56 | 0.573 | |

| Gynoid BF% | 0.32±0.09 | 0.28±0.09 | 0.36±0.06 | -17.40 | < 0.001 | 0.34±0.08 | 0.30±0.10 | 7.34 | < 0.001 | |

| AOI | 0.34±0.11 | 0.36±0.12 | 0.32±0.09 | 7.08 | < 0.001 | 0.33±0.10 | 0.35±0.11 | -4.41 | < 0.001 | |

| CDI score | 10.80±6.92 | 10.54±6.39 | 11.06±7.40 | -1.40 | 0.163 | 8.77±5.74 | 12.73±7.38 | -11.29 | < 0.001 | |

| SAS-C score | 5.66±4.16 | 5.14±3.89 | 6.20±4.39 | -4.82 | < 0.001 | 4.85±3.79 | 6.43±4.36 | -7.29 | < 0.001 | |

| Depression | 199 (13.1) | 87 (11.2) | 112 (15.0) | 4.53 | 0.033 | 58 (8.4) | 141 (19.5) | 35.54 | < 0.001 | |

| Social anxiety | 439 (31.1) | 153 (26.2) | 286 (36.1) | 15.84 | < 0.001 | 188 (22.2) | 251 (39.5) | 40.08 | < 0.001 | |

2.2. 儿童青少年抑郁、社交焦虑及脂肪分布情况

如表 1所示,13.1%的儿童青少年存在抑郁症状,其中男生的抑郁症状比例为11.2%,显著低于女生的15.0%(χ2=4.53,P=0.033); 7~12岁儿童的抑郁得分和抑郁症状比例均显著低于13~18岁青少年(t=-11.29,P < 0.001; χ2=35.54,P < 0.001)。儿童青少年社交焦虑症状比例为31.1%,其中男生的社交焦虑比例为26.2%,显著低于女生的36.1%( χ2=15.84,P < 0.001); 7~12岁儿童的社交焦虑症状比例也显著低于13~18岁青少年(22.2% vs. 39.5%,χ2=40.08,P < 0.001)。

在脂肪分布上,男生的总脂肪率、Android脂肪率和Gynoid脂肪率均显著低于女生(P均 < 0.001),但AOI显著高于女生(P < 0.001)。在年龄分组上,两个年龄组的Android脂肪率差异无统计学意义(P=0.537),但7~12岁儿童总脂肪率和AOI均显著高于13~18岁青少年(P < 0.001),Gynoid脂肪率则显著低于13~18岁青少年(P < 0.001)。

2.3. 儿童青少年抑郁和社交焦虑与脂肪分布的关系

如表 2所示,总体来看,儿童青少年的总脂肪率、Android脂肪率、Gynoid脂肪率和AOI与社交焦虑和抑郁的线性关联均不显著(P均>0.05),按性别分组后也得到类似的结论(P均>0.05)。但按年龄分组后发现,尽管13~18岁青少年群体中各测量指标与社交焦虑和抑郁的线性关联均不显著(P均>0.05),但对于6~12岁儿童,随着Android脂肪率的升高,儿童青少年抑郁和社交焦虑的风险降低(β=-0.50,95%CI:-0.98~-0.02; β=-0.72,95%CI:-1.24~-0.20);随着Gynoid脂肪率的升高,正向预测儿童青少年社交焦虑的风险也随之升高(β=0.36,95%CI:0.02~0.71);随着AOI的升高,儿童青少年社交焦虑的风险升高(β=0.31,95%CI:0.02~0.59)。

表 2.

儿童青少年脂肪分布与抑郁和社交焦虑(标准化回归系数β)的关系

Association between fat distribution, depression and social anxiety (standardized regression coefficient, β) among children and adolescents

| Items | Total | Boys | Girls | |||||

| β (95%CI) | P | β (95%CI) | P | β (95%CI) | P | |||

| The standardized regression coefficient of β was calculated using the general linear model. All models were controlling for gender, age, weight, height and body mass index. BF%, total body fat precent; AOI, Android-to-Gynoid fat ratio. | ||||||||

| Depression | ||||||||

| BF% | -0.36 (-0.13, 0.52) | 0.421 | -0.02 (-0.14, 0.09) | 0.713 | -0.05 (-0.20, 0.10) | 0.520 | ||

| Android BF% | -0.12 (-0.51, 0.27) | 0.536 | -0.46 (-1.01, 0.1) | 0.109 | -0.20 (-0.78, 0.38) | 0.501 | ||

| Gynoid BF% | 0.07 (-0.19, 0.32) | 0.621 | 0.30 (-0.09, 0.68) | 0.128 | 0.07 (-0.32, 0.46) | 0.720 | ||

| AOI | 0.02 (-0.17, 0.21) | 0.862 | 0.17 (-0.08, 0.43) | 0.182 | 0.17 (-0.16, 0.49) | 0.319 | ||

| Social anxiety | ||||||||

| BF% | -0.02 (-0.11, 0.07) | 0.695 | -0.02 (-0.13, 0.10) | 0.129 | -0.03 (-0.19, 0.12) | 0.120 | ||

| Android BF% | -0.18 (-0.57, 0.22) | 0.385 | -0.52 (-1.10, 0.05) | 0.073 | -0.08 (-0.68, 0.51) | 0.788 | ||

| Gynoid BF% | 0.10 (-0.17, 0.36) | 0.469 | 0.33 (-0.06, 0.72) | 0.098 | 0.003 (-0.40, 0.39) | 0.982 | ||

| AOI | 0.06 (-0.13, 0.26) | 0.527 | 0.22 (-0.05, 0.48) | 0.105 | 0.09 (-0.24, 0.42) | 0.601 | ||

| Items | 6-12 years | 13-18 years | ||||||

| β (95%CI) | P | β (95%CI) | P | |||||

| Depression | ||||||||

| BF% | -0.08 (-0.19, 0.04) | 0.141 | 0.004 (-0.14, 0.15) | 0.153 | ||||

| Android BF% | -0.50 (-0.98, -0.02) | 0.040 | 0.06 (-0.57, 0.70) | 0.845 | ||||

| Gynoid BF% | 0.26 (-0.06, 0.57) | 0.110 | -0.04 (-0.47, 0.39) | 0.865 | ||||

| AOI | 0.23 (-0.03, 0.49) | 0.082 | 0.01 (-0.28, 0.31) | 0.926 | ||||

| Social anxiety | ||||||||

| BF% | -0.11 (-0.23, 0.02) | 0.085 | -0.07 (-0.08, 0.21) | 0.211 | ||||

| Android BF% | -0.72 (-1.24, -0.20) | 0.007 | 0.27 (-0.35, 0.88) | 0.395 | ||||

| Gynoid BF% | 0.36 (0.02, 0.71) | 0.037 | -0.14 (-0.56, 0.27) | 0.499 | ||||

| AOI | 0.31 (0.02, 0.59) | 0.034 | -0.03 (-0.32, 0.26) | 0.824 | ||||

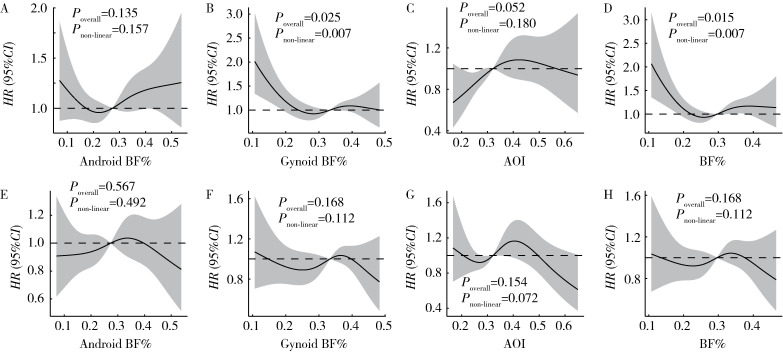

采用RCS拟合线性回归模型分析脂肪分布与社交焦虑、抑郁之间的关系,结果如图 1所示,儿童青少年总脂肪率、Android脂肪率、Gynoid脂肪率和AOI均与抑郁的风险相关。具体而言,总脂肪率和Gynoid脂肪率与抑郁风险呈近似的“U”型曲线,儿童青少年抑郁风险随总脂肪率和Gynoid脂肪率的升高而降低,但当总脂肪率>26.8%、Gynoid脂肪率>30.9%时,抑郁风险会随之上升; 儿童青少年抑郁风险与Android脂肪率和AOI的非线性关系不显著(图 1A~D)。

图 1.

儿童青少年Android脂肪率、Gynoid脂肪率、AOI、总脂肪率与抑郁(A~D)和社交焦虑(E~H)的非线性关系

Nonlinear association of Android BF%, Gynoid BF%, AOI, BF% and depression (A-D), social anxiety (E-H)

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BF%, total body fat precent; AOI, Android-to-Gynoid fat ratio.

对于社交焦虑风险而言,儿童青少年的总脂肪率、Gynoid脂肪率、Android脂肪率和AOI与社交焦虑的非线性关系均不显著,呈现复杂曲线关系(图 1E~H)。

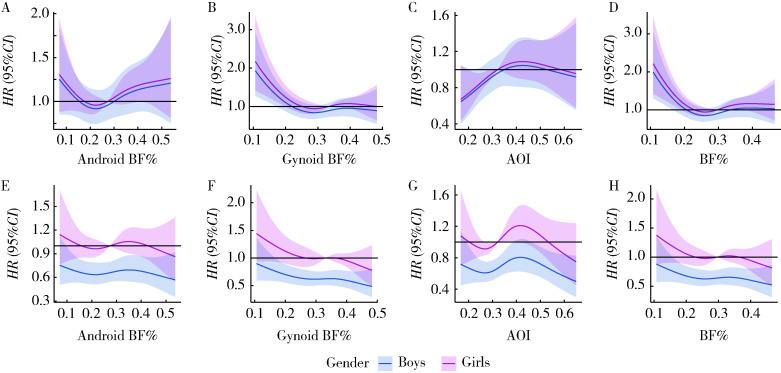

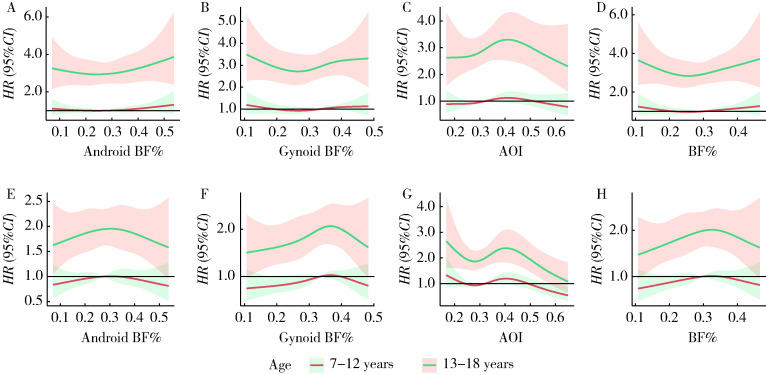

2.4. 不同性别和年龄的儿童青少年抑郁和社交焦虑与脂肪分布的非线性关联

在总脂肪率、Android脂肪率、Gynoid脂肪率及AOI与抑郁和社交焦虑的非线性关联上,不同性别的变化趋势一致,但整体上男生脂肪分布的社交焦虑风险HR值显著高于女生(图 2)。不同年龄的差异分析发现,7~12岁儿童和13~18岁青少年的总脂肪率、Android脂肪率、Gynoid脂肪率及AOI与抑郁和社交焦虑的非线性关联变化趋势一致,但整体上13~18岁青少年脂肪分布的抑郁和社交焦虑风险HR值均显著高于7~12岁儿童(图 3)。

图 2.

不同性别Android脂肪率、Gynoid脂肪率、AOI、总脂肪率与抑郁(A~D)和社交焦虑(E~H)的非线性关系

Nonlinear association of Android BF%, Gynoid BF%, AOI, BF% and depression (A-D), social anxiety (E-H) in different gender

Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

图 3.

不同年龄Android脂肪率、Gynoid脂肪率、AOI、总脂肪率与抑郁(A~D)和社交焦虑(E~H)的非线性关系

Nonlinear association of Android BF%, Gynoid BF%, AOI, BF% and depression (A-D), social anxiety (E-H) in different age groups

Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

3. 讨论

通过使用DXA金标准测量身体成分,本研究初步探索了脂肪分布与儿童青少年抑郁和社交焦虑之间可能的线性和非线性关联。相较于多元线性回归模型,RCS实现了关联强度的剂量-反应关系的连续呈现,更具有实际意义。

本研究结果显示,儿童青少年中抑郁和社交焦虑水平较高,女生的抑郁和社交焦虑症状百分比显著高于男生,13~18岁青少年抑郁和社交焦虑症状百分比高于7~12岁儿童。有研究发现,与肥胖男性相比,肥胖女性抑郁症和焦虑症的检出率大约是其两倍[18]。以往的研究也发现,进入青春期前,人体脂肪组织发育水平差异不明显; 进入青春期后,人体脂肪组织的分布在性别之间存在差异,女生体脂率高于男生[19]。与此同时,儿童青少年时期是身体和心理社会发展的关键时期,女生可能更容易由于肥胖和外形的改变而导致负面情绪,如社交焦虑和抑郁、自尊心降低等问题[20]。

关于抑郁与肥胖关系的研究得出的结论并不一致,有研究显示,BMI的增加与抑郁症状显著相关[21],但另一些研究并没有发现两者的显著关联[22]。国内也有学者通过对减重门诊的706例肥胖患者和非肥胖人群对比分析发现,肥胖人群与非肥胖人群的焦虑和抑郁评分差异无统计学意义,且与BMI不存在相关性[23]。本研究也发现了类似的结论,儿童青少年的脂肪分布与其抑郁和社交焦虑不存在线性关联,进一步研究发现其脂肪分布与抑郁呈现倒“U”型曲线关系,即脂肪率(包括总脂肪率和Gynoid脂肪率)过高或者过低都会增加儿童青少年的抑郁风险,且在不同性别和年龄间具有相同趋势。以前的研究多使用BMI作为判断肥胖的指标,忽略了脂肪和非脂肪的区分,可能得到不准确的结果[24]。本研究使用RCS将脂肪分布与抑郁、社交焦虑的结局事件结合,更加直观、深入地刻画了关联强度的变化,可以为未来研究肥胖与抑郁、社交焦虑的关联提供一定的启示。

目前,肥胖与社交焦虑、抑郁关联的病理学机制尚未完全清楚。肥胖与大脑中的各种结构和功能变化相关联,这些变化与抑郁症中观察到的变化非常相似,例如特定区域的细胞密度增加、神经连通性和兴奋性受损[25]。一种可能的解释是与下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺(hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal,HPA)轴控制的皮质醇激素有关,肥胖可能通过刺激HPA轴而与精神疾病的发展相关[26]。特别是对于儿童青少年来说,中枢神经系统正处于脆弱的发育窗口期,这一阶段持续且增强的应激事件,如肥胖和肥胖导致的应激事件,会通过HPA轴导致大脑中介质水平的变化,与随后的焦虑和抑郁呈正相关[27]。另一种机制是炎症的发生。肥胖可能使促炎细胞因子分泌增加从而导致炎症,炎症因子(如白细胞介素)水平的升高可能导致情绪调节异常,与抑郁症、焦虑症的发病率呈正相关[28]。而抑郁症等可导致HPA轴异常和慢性炎症状态,促进肥胖的发生和发展[29]。有研究也发现,社交焦虑状态在肥胖人群中与C反应蛋白及炎症状态相关[30],进一步支持了上述机制。因此,我们猜测,脂肪分布在达到某一个程度时,可能会作用于HPA轴并使促炎细胞因子分泌增加,从而导致儿童青少年抑郁和社交焦虑症状的增强。

与BMI相比,身体成分测量可以更好地体现出成人对体型的不满[31],从而更好地预测个体的情绪、行为等因素。本研究的优势在于采用DXA对身体成分进行测量,高精度地评估了脂肪分布,且本研究样本量大,纳入的儿童青少年年龄范围广泛,但同时本研究也具有一些潜在的限制。首先,研究为横断面设计,只能初步探讨儿童青少年的脂肪分布与其社交焦虑和抑郁的关联,无法确定两者之间的因果性,将来的研究可以通过队列数据进行完善; 其次,抑郁和社交焦虑的测量采用的是自我报告的问卷形式,由于社会称许效应的影响,可能与实际情况存在偏差; 再次,本研究取样为北京地区的中小学生,不能完全代表中国儿童青少年群体的整体情况,将来可在全国范围内进行抽样以进一步研究; 最后,尽管本研究的多因素模型中对一些人口学因素进行了控制,但是仍无法完全排除可能的混杂因素,例如饮食、运动和睡眠问题等。

综上所述,中国儿童青少年存在抑郁和社交焦虑问题,需要引起广泛的重视。本研究使用DXA对身体成分进行测量,初步探索了脂肪分布与抑郁和社交焦虑之间的线性和非线性关联,结果发现脂肪分布与抑郁和社交焦虑均不存在线性关联; 脂肪分布与抑郁呈现倒“U”型曲线,且这种趋势在不同性别和不同年龄组上均表现出一致性。通过控制饮食、增强运动等方式,将儿童青少年的脂肪分布维持在一个合适的水平区间而不是过度的追求低水平的脂肪分布,是未来抑郁、社交焦虑防控需要考虑的方向。

Funding Statement

国家自然科学基金(81673192)和北京市自然科学基金(7222244)

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81673192) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7222244)

References

- 1.Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, et al. New WHO pre-valence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: Asyste- matic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):240–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu J, Xu XF, Huang YQ, et al. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiat. 2021;8(11):981–990. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: A review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Australia. 2009;190(7):S54–S60. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaine B. Does depression cause obesity? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies of depression and weight control. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(8):1190–1197. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O'Brien PE. Depression in association with severe obesity: Changes with weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2058–2065. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quek YH, Tam WWS, Zhang MWB, et al. Exploring the association between childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: A meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):742–754. doi: 10.1111/obr.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao WW, Zong QQ, Zhang JW, et al. Obesity increases the risk of depression in children and adolescents: Results from a systema-tic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disorders. 2020;267:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, et al. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 学龄儿童青少年超重与肥胖筛查[S]. (2018-08-01)[2023-01-05]. https://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/yyhspws/xzdc/201804/P020180418380884895984.pdf.

- 10.Javed A, Jumean M, Murad MH, et al. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Obes. 2015;10(3):234–244. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, et al. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int J Obesity. 2008;32(6):959–966. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y, Hoglund P, Clyne N. Comparison of DEXA and bioimpedance for body composition measurements in nondialysis patients with CKD. J Ren Nutr. 2019;29(1):33–38. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu XJ, Zhang DD, Liu Y, et al. Dose response association between physical activity and incident hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Hypertension. 2017;69(5):813–820. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye SY, Zhu CN, Wei C, et al. Associations of body composition with blood pressure and hypertension. Obesity. 2018;26(10):1644–1650. doi: 10.1002/oby.22291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovacs M. The childrens depression inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21(4):995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helsel WJ, Matson JL. The assessment of depression in children: The internal structure of the child depression inventory (CDI) Behav Res Ther. 1984;22(3):289–298. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(84)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagreca AM, Dandes SK, Wick P, et al. Development of the social anxiety scale for children: Reliability and concurrent validity. J Clin Child Psychol. 1988;17(1):84–91. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1701_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao G, Ford ES, Dhingra S, et al. Depression and anxiety among US adults: Associations with body mass index. Int J Obesity. 2009;33(2):257–266. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.陈 曼曼, 马 莹, 苏 彬彬, et al. 北京市7~18岁儿童青少年体成分百分位值变化特征. 中国学校卫生. 2021;42(11):1703–1707. [Google Scholar]

- 20.He W, James S A, Merli MG, et al. An increasing socioeconomic gap in childhood overweight and obesity in China. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):E14–E22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung KH, Chiou HY, Chen YH. Psychological and physiological correlates of childhood obesity in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17439. doi: 10.1038/srep17439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merikangas AK, Mendola P, Pastor PN, et al. The association between major depressive disorder and obesity in US adolescents: Results from the 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Exa-mination Survey. J Behav Med. 2012;35(2):149–154. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9340-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.陆 迪菲, 袁 振芳, 杨 丽华, et al. 肥胖人群焦虑抑郁情况与肥胖程度相关性的调查分析. 中国糖尿病杂志. 2019;27(8):592–596. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung S. Body composition analysis and references in children: Clinical usefulness and limitations. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(2):236–242. doi: 10.1038/s41430-018-0322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapuano KM, Laurent JS, Hagler DJ, et al. Nucleus accumbens cytoarchitecture predicts weight gain in children. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(43):26977–26984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007918117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dionysopoulou S, Charmandari E, Bargiota A, et al. The role of hypothalamic inflammation in diet-induced obesity and its association with cognitive and mood disorders. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):498. doi: 10.3390/nu13020498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang JH, Lam SP, Li SX, et al. A community-based study on the association between insomnia and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: Sex and pubertal influences. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2014;99(6):2277–2287. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: A meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2017;135(5):373–387. doi: 10.1111/acps.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jantaratnotai N, Mosikanon K, Lee Y, et al. The interface of depression and obesity. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2017;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierce GL, Kalil GZ, Ajibewa T, et al. Anxiety independently contributes to elevated inflammation in humans with obesity. Obesity. 2017;25(2):286–289. doi: 10.1002/oby.21698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dos Santos RRG, Forte GC, Mundstock E, et al. Body composition parameters can better predict body size dissatisfaction than body mass index in children and adolescents. Eat Weight Disord. 2020;25(5):1197–1203. doi: 10.1007/s40519-019-00750-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]