Abstract

Crisismanship performance is an acid test of governance. Legitimate policies can significantly contribute to the crisismanship performance because they can ensure the willing obedience of public stakeholders and citizens. Therefore, a key research question is how a government can frame crises and pertinent policies to ensure its legitimacy and crisismanship performance? To legitimate policies, this study proposes a contingent model which is based on matching the legitimation strategies (i.e., input, throughput, and output) with different types of value decisions involved in a crisis (i.e., taboo, routine, and tragic trade-offs). This study provides three main propositions. First, in the most salient crises, characterized by taboo trade-offs, the vital role of the input legitimacy (i.e., the responsiveness of a government) can rule out the throughput (i.e., the quality of policy-making process) and the output legitimacy (i.e., the quality of policy outcome). Second, regarding the moderately salient crises, characterized by tragic trade-offs, the throughput legitimacy plays a significant role in determining the crisismanship performance. Finally, in the least salient crises, characterized by routine trade-offs, the output legitimacy can make up for the lack of input and throughput legitimacy.

Keywords: Legitimacy, Crisismanship, Public stakeholders, Value-based decision making

Introduction

Crises test the legitimacy, capacity, and performance of governments. The effectiveness of these concepts in action is most manifest when serious crises like pandemics, wars, and multi-disaster hit a nation with potentially massive consequences (Farazmand, 2007, 2009, 2017). Each of these concepts has deep literature in the background, but what is not studied as much until recently is the theory or concept of “crisismanship” (Farazmand & Danaeefard, 2021). As the first scholars who coined the term, Farazmand and Danaeefard (2021: 1) defined crisismanship as the art and science of effectively and consistently making sense of, responding to, managing, and communicating about crises at different levels of governance, administration, and operations.

The mainstream literature on crisis management promotes an objective and apolitical notion of crises (e.g., Coombs & Holladay, 2002; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993) where the government’s role is mainly limited to ex-post reactions. In contrast, those who adopt a constructivist approach to crisis management emphasize the distinct political nature of governments’ crisis management activities. Similarly, by acknowledging the politics of crisis policies, the theory of crisismanship, as developed by Farazmand and Danaeefard (2021), indicates that defining, sensemaking, policy-making, and responding to crises is a ground for political contests between governments and stakeholders. Each side of the contest will gain certain political advantages if they can define the situation at hand as a “crisis”. The stakeholders, on the one hand, can be assured of allocating the government’s attention and resources as their pertinent issue is included in the agenda in this way. On the other hand, governments can (ab)use crises as excuses to break with norms of policy and decision-making and enforce their unilateral authority accordingly (see ‘t Hart & Boin, 2001 for a review). This study also takes a constructivist position to assert the active role of governments and public stakeholders in (re)framing crises based on their administrative and political purposes.

As mentioned, crises as socially constructed phenomena open up political maneuvering windows for governments, thus, incentivizing them to enter emergency politics (e.g., Boin & ‘t Hart, 2000). However, they also impose some costs that make governments risk-averse to do so. Firstly, crises increase public expectations and policy scrutiny. This puts the governments’ performance in the spotlight and their legitimacy at stake. Additionally, crises intensify the interdependence of policies’ performance and legitimacy. This makes the situation more wicked. As a result, if governments fail to legitimize their crisis governing activities, they will undoubtedly end up with unacceptable crisismanship performance. The reason is that citizens’ active engagement and widespread participation are critical success factors in implementing crisis-related policies (Farazmand, 2004, 2007, 2009). However, citizens’ participation depends on how legitimate they perceive the governmental policies and decisions. Thus, governments should consciously pay attention to legitimacy whenever they engage with crisismanship.

Thus, a critical question about crisismanship is how governments can successfully legitimize their governing activities regarding crises? Here, a deeper analytical look at the types of government decisions and the stakeholders’ expectations in times of crisis will be helpful. As discussed in more detail below, citizens, at large, and social actors, in particular, usually shape conflicting stakeholder groups. These groups have different values and interests and therefore they face the government with various demands. Real-world restrictions make it impossible to satisfy all these requests. Thus, governments must make decisions for balancing these different interests while striving to act in the public interest. Therefore, crisismanship as a balancing act (Pesch, 2008) inevitably entails value-based decision-making, i.e., prioritizing stakeholders’ values and trading off between them. This means that some stakeholders should ignore or postpone their requests. Therefore, this is undoubtedly unfavorable for some stakeholders. Nonetheless, to the extent that stakeholders believe that the government legitimately balances their values, they will obey and support the resultant crisismanship’s policies and decisions.

Accordingly, governments’ most challenging yet inevitable decision task during crises is to strike a trade-off between stakeholders’ conflicting values while protecting their legitimacy claims. The capacity to successfully handle such difficult value-based balancing decisions (i.e., trade-offs) is pivotal for a government’s crisismanship performance because it ensures the public acceptance of the crisis policies. In this way, this study argues that classifying crises according to the type of involved trade-offs is insightful to overcome this challenge. The point is that not all values and interests involved in a trade-off have the same moral valence as well as the same effect on public opinion. Here, we draw on Fiske and Tetlock (1997), who introduced a value-based decision-making framework based on two main kinds of values (i.e., secular and sacred) and three resultant trade-offs (i.e., routine, taboo, and tragic) between them. Sacred values are core values such as human life, freedom, equality, security, honor, and so on. People treat sacred values as possessing infinite significance, absolute, and protected from trade-offs, especially against secular values such as monetary benefits (Baron & Spranca, 1997; Fiske & Haslam, 1996). In a routine trade-off, two secular values such as the “price” and “delivery time” of services would be exchanged. In a tragic trade-off, two sacred values such as the citizens’ right to “liberty” and “health” are pitted against each other. And, in a taboo trade-off, a sacred value would be pitted against a secular value.

Consequently, the art of crisismanship is based on recognizing the trade-off at hand and taking the appropriate decisional behavior. While striking a taboo trade-off is intolerable for stakeholders, they are more tolerable of a tragic trade-off. For example, pitting the lives of crisis-affected citizens against economic considerations (i.e., a taboo trade-off) is totally unacceptable for stakeholders, and its significant moral ramifications seriously will threaten the legitimacy of the government. However, there can be different crises that do not necessarily involve taboo trade-offs. For example, public protests against COVID-19 lockdowns indicate a “tragic trade-off” where the sacred value of health collides with the right to liberty, another sacred value. These are two distinct crisis decision-making situations that require different patterns and procedures to be adopted by the governments if they want to make legitimate decisions in the judgmental eyes of the stakeholders (e.g., Gunia et al., 2012; Hanselmann & Tanner, 2008; Schoemaker & Tetlock, 2012).

Given the centrality of value-based decision-making in legitimizing governing activities in crisis, a key relevant research question that this study addresses is how a government can frame crises, stakeholders’ expectations, and its governing activities according to different types of value-based decisions (i.e., trade-offs) to ensure its legitimacy and crisismanship performance? To answer this question, firstly a framework for determining the saliency of crises based on the involved trade-offs and the level of stakeholders’ expectations will be proposed. Then, by differentiating between three types of policy legitimacy (i.e., input, throughput, and output as suggested by Schmidt, 2013), it will be showed how governments can legitimize their crisismanship activities by matching the types of trade-offs, the appropriate procedures of decision-making, and the different types of policy legitimacy.

To achieve this goal, in the next section, a brief introduction on the stakeholder approach to crisismanship will be provided. Here, this study draws on Luhmann’s theory of society to determine the role of governments and stakeholders in crisismanship. Then, different types of legitimacy and how they can affect the crisismanship performance will be discussed. Following that, the theoretical propositions based on crisis saliency and legitimacy frameworks will be proposed. This study will be concluded by discussing the framework’s implications and contributions to the theory and practice of crisismanship as well as providing the new research avenues that future research can follow.

A Stakeholder Approach to Modern Society: The Roots of Government Legitimacy

According to Luhmann’s (2020) theory of society, modern society as a whole system is composed of several independent functional systems, namely science, law, religion, politics, and economy. He (2020) argued that the functional differentiation is the distinct character of modern society compared to the preceding differentiation regimes (i.e., segmentary, hierarchical, and organizational regimes). It enables the society to deal with external complexity at the expense of higher internal complexity. Each of these functional systems follows its incommensurable internal logic and promotes its values insensitive to the others: science limits itself to the reductionist logic of true/untrue; economy sees the world through the lens of gain and loss; politics understands it as a ground of power struggles and so on (Djanibekov et al., 2016). Over time, insensitivity to other systems enables the functional systems to increase their internal complexity and performance, a situation that Luhmann calls “operational closure” (Luhmann, 2020). Operational closure increases, in turn, the total number of distinct environmental elements and possible relationships between them, which leads to a more complex society. More complexity would reduce the sustainability of the entire system, i.e., society. To countervail the effects of functional differentiation, which can lead to anarchy, modern society has introduced and used the integrating power of the modern government to harmonize the intersystem interactions (Valentinov et al., 2019).

In this sense, modern governments are the product of inevitable defects of functional differentiation. The main problem with this differentiation regime is that the individual functional systems fail to govern interdependencies in their environment. This failure causes new problems and crises that need more complexity and differentiation to deal with (Valentinov et al., 2019). To stop this vicious cycle, concentrated authority and resources of governments can be helpful to harmonize internal and external interdependencies of society. In this way, governments and policy-makers create value for the whole society mainly by balancing the values and interests of constituent stakeholders who have a narrow view of the society. Governments, in fact, are to be the eyes of a system that suffers from the blindness of its constituents. Whenever the blindness or short-sightedness of the constituents hinders society from functioning, the government intervenes as a balancing mechanism acting in the public interest (Pesch, 2008). Providing public goods that may be out of private sector sight is a well-known economic example. Political intervention when the values and interests of constituent stakeholders collide is another example (Pesch, 2008). Thus, governance, and crisismanship as a particular area of national governance, necessarily entail balancing decisions and value trade-offs. Although inevitable, trading off between stakeholders’ conflicting values and interests can fire back. The reason is that any deficiency in the process or the outcome of these trade-offs may result in the de-legitimization of the policies and government.

Back to our main track, it is notable that another outcome of functional differentiation (Luhmann, 2020) is the exponential growth of the number of interest groups and stakeholders in society. Social grouping does not follow the logic of functional differentiation. The functional sphere of society can be divided into incommensurable and independent parts. However, the totality of organic human existence does not allow for functional differentiation in the same way. As a result, the mass public would shape various intra-functional, inter-functional, or even supra-functional stakeholder groups, including advocacy groups, interest groups, and policy subsystems (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993). These different stakeholders try to promote their values in the governance of society. They may raise social issues and use various tools such as public demonstrations, protests, campaigning, etc., to affect the policy-making process and the government’s agenda. Given the high sensitivity and responsiveness that crises require, it is not surprising that stakeholders use the triggering events to turn their issues into crises urging for an immediate response (Nohrstedt & Weible, 2010; ‘t Hart & Boin, 2001). Now the question is how responsive should governments be to the issues raised by stakeholders?

In contrast to other functional systems of modern society, the government as a system is supposed to be ambidextrous or multifunctional (Djanibekov et al., 2016). This means the ability to maintain the precarious balance between “responsiveness” and “effectiveness” (Scharpf, 1988, 1999) where more responsiveness to stakeholders equals less effectiveness. Denhardt and colleagues (2013) describe this inevitable tension between efficiency and responsiveness as follows: “You must operate with one eye toward managerial effectiveness and the other toward the desires and demands of the public” (p. 9). The more a government inclines toward effectiveness, which means operational closure and insensitivity to other systems, the less responsiveness it can show, and vice versa. A significant inclination to each side would cast shadows of doubt on the publicness, performance, and hence, the legitimacy of the government and its governing activities.

By the same token, Scharpf (1988, 1999) noticed that democratic national governance always oscillates between “responsiveness” and “effectiveness” which is culminated in liberal democracies. Explaining this paradox, he (1988) notes that compared to anarchy, the existence of government in modern society is justified by the logic of effectiveness: “as an arrangement for improving the chances of purposive fate control through the collective achievement of goals” (p. 239). However, on the other hand, the logic of democratic legitimacy favors the smaller units of government because by increasing the scale of a united government, the chance of different stakeholders and their interests to be represented in the government would be lowered. Following this, he (1988, 1999, 2009) distinguishes between two distinct sources of legitimacy, namely, “input” ad “output”, recalling the responsiveness and effectiveness of governance activities, respectively.

In the next section, we will address the issue of legitimacy.

Crisismanship and the Legitimacy of Governing Activities

As discussed, legitimacy has a significant impact on the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of people toward government authorities and governing activities, especially during crises (Christensen et al., 2016; Farazmand, 2014, 2017). Consequently, legitimacy may critically facilitate or hinder the crisis performance of a government (Boin et al., 2014; Demiroz & Unlu, 2018; Ma & Christensen, 2019; Dolamore et al., 2021; Christensen et al., 2020). By increasing public trust, legitimacy makes citizens more willing to comply and put their resources voluntarily at the disposal of authorities to implement policies (Bogliacino et al., 2021; Levi & Sacks, 2007). This is why a sizable literature is devoted to the different types of legitimacy, legitimation processes, strategies, and the role of legitimacy in government policies, performance, and effectiveness (Stillman, 1974; Tyler, 1994; Farazmand, 1989; François & Sud, 2006; Scharpf, 2009; Cho, 2017).

Similar to many other social concepts, legitimacy is inherently a vague concept (François & Sud, 2006; Hybels, 1995). Definitions abound based on the scholars’ point of view. Generally, legitimacy is defined as a value that provides the moral grounds that something or someone is recognized and accepted as righteous (Chen, 2016). From a psychological viewpoint, it is viewed as a psychological property of a social entity that leads those connected to it to believe that it is appropriate and proper (Tyler, 2006). For those who have a political background, legitimacy is the right to exercise power and a process of persuasion to bolster willing obedience and cooperation on the part of those subject to power (Beetham, 1991; Tankebe, 2013). Still, for institutionalists and organizational researchers, legitimacy is the right to exist that a system should justify to its stakeholders (Hybels, 1995; Suchman, 1995).

While the same definitional dispersion marks the field of public policy, there is a growing consensus among scholars and practitioners that legitimacy in this context has to do with citizens’ and other stakeholders’ perceptions of whether the actions and decisions of authorities are appropriate compared to publicly defined systems of values and interests (Suchman, 1995; Christensen et al., 2016; Deephouse et al., 2017). Schmidt (2022) takes this policy-centered view by noting that while in a broad and classical sense, legitimacy refers to the citizens’ consent to a governing authority, it also indicates the acceptance of such an authority’s governing activities, especially in crisis times.

Given the importance of legitimacy for governments’ performance, scholars have proposed different typologies of policy legitimacy and legitimization strategies. However, most congruent with our approach is the before-mentioned input/output legitimacy distinction of Scharpf (1999). Input legitimacy has to do with representing and considering all stakeholders’ values and interests in policy-making. Put differently, it denotes the chance for different stakeholders and their claims to be represented in the government. Another source of legitimacy for a democratic government is “output legitimacy”. It has to do with the policy performance and effectiveness for the public good.

More recently, Schmidt (2013), following the systemic logic of Scharpf (1999), added a third kind of legitimacy to the original typology: “throughput legitimacy,“ which indicates “the quality of governance procedures, including the efficacy of the policy-making processes, the accountability to relevant forums of those engaged in making the decisions, the transparency of their actions and access to information, along with their openness and inclusiveness with regard to civil society” (Schmidt, 2022: 983).

Now the question is how governments and policy-makers can appropriately use these sources of legitimacy to legitimize and push forward their crisis policies? Many public policy scholars, who have especially addressed the issue of policy failure, have addressed this question (see, for example, Wallner, 2008). Considering the time dimension of policies and crises, some scholars (e.g., Wallner, 2008) argued that according to the available time for developing, implementing, and communicating about policies, policymakers should choose different types of policy legitimacy to invest (Schmidt, 2022; ‘t Hart & Boin, 2001). Here, a possible trade-off between input and output legitimacy is quite obvious, where the good performance can offset the lack of citizens’ participation or the bad outcomes can still be legitimate if citizens voted for the related policies (Schmidt, 2020). Other scholars who have mainly worked on emergency politics and political exceptionalism (e.g., Schmidt, 2022; Honig, 2014; White, 2015) have warned that this trade-off equation is too simplistic and symmetrical. They argue that the ever-increasing presence of crises in today’s world favors the concentration of authority and an asymmetric shift to output legitimacy on the part of the policy-makers (Honig, 2014). This increasing level of resorting to the emergency politics (i.e., the concentration of authority and overusing output legitimacy) can finally erase the faint traces of democratic legitimacy in modern societies. To the extent that stakeholders take these warns seriously, even the necessary and righteous appeals to emergency politics would face policy-makers with delegitimizing allegations of power abuse in the name of crisismanship (‘t Hart & Boin, 2001).

The implication is obvious. The ability to consciously maintain the precarious balance between effectiveness and responsiveness plays a vital role in policy legitimacy and crisismanship performance. The literature on exceptionalism and emergency politics, as mentioned above, has provided some insightful ideas on this subject, mainly by focusing on the time dimension of crisis policies. However, this study argues that an almost ignored aspect of crisismanship is the role of value-based decision-making and its different types of value trade-offs. In the sections below, therefore, it will be discussed how governments and policy-makers can use the different types of value trade-offs to make sense and frame the stakeholders’ expectations about crises and choose the right strategy to legitimize crisis policies accordingly.

How to Make Sense of Crises: Toward a Theory of Crisis Saliency

The increasing rate of local, regional, and global crises has led many scholars from different fields to scribble on causes, outcomes, and types of crises (e.g., Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993). Consequently, different definitions and typologies of crises have been provided in the field of public policy. They mainly concentrate on objective attributes of crises such as urgency and unexpectedness (see, for example, Ardito et al., 2021; Nohrstedt & Weible, 2010). As a mostly cited instance, Barton (1993) posited that a crisis often happens quickly and unfolds in unexpected ways. This narrow conception cannot reflect the broad range of issues that this study placed under the term “crisismanship” as a distinct governing activity (Farazmand & Danaeefard, 2021). The main reason is that it presumes an objective status for crises as if they are deemed to exist only once they are acknowledged and received a quick and urgent response from the government. However, as it could be inferred from the multiple-streams framework (Kingdon, 1995), like many other policy issues, there can be many crawling crises in a society that are quite urgent from the stakeholders’ point of view but not yet represented in the governments’ agenda (Tregidga & Laine, 2022). For example, many crisis-related issues, such as the high rates of young unemployment, immigration, ecological degradation, etc., are currently noticeable in many societies. However, they may not appear on the government’s agenda or receive emergent responses (Boswell, 2011; Papadopoulos, 2016).

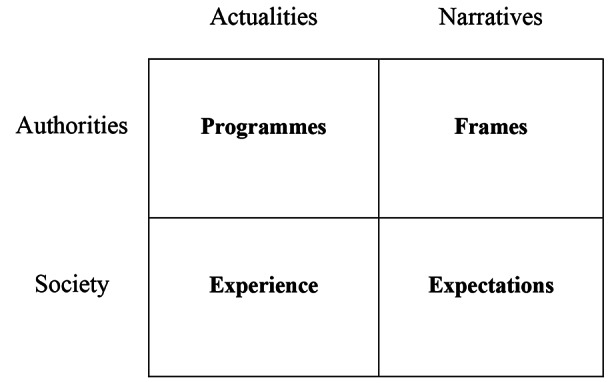

Therefore, more consistent with this study’s approach are those definitions that have taken a more constructivist conception of crises. In this category, some definitions distinguish between human-made and natural crises (e.g., Rosenthal & Kouzmin, 1993; Boin et al., 2016; Tokakis et al., 2019). Some others define an (organizational) crisis as “an event perceived by managers and stakeholders as highly salient, unexpected, and potentially disruptive.“ (Bundy et al., 2017: 1662). Of particular help for this study is the crisis diagnosis framework presented by Seabrooke and Tsingou (2019). Congruent with our government/stakeholders distinction, these authors divide the actors involved in crisismanship into “authorities” and “society” with their respective backward (i.e., actualities”), and forward (i.e., “narratives”) subjective engagements with crises (see Fig. 1). The nexus of “programmes/frames” on the part of authorities refers to their current mental conceptions that shape their first response to a potential crisis and the frames they use to determine the way forward. Similarly, the nexus of “experience/expectations” on the part of stakeholders indicates their current mental map that determines what they perceive as politically salient and what they expect to happen. Interactions between these aspects have critical implications for crisismanship performance. According to Expectancy Violations Theory (EVT) (Burgoon, 1993), any significant expectation violation of stakeholders due to incongruency between the authorities’ and stakeholders’ sensemaking of the situation can threaten the legitimacy of policies and crisismanship overall performance.

Fig. 1.

Crisis diagnosis framework (adopted from Seabrooke & Tsingou, 2019)

To sum up, it is therefore obvious that the art of crisismanship lies in the power of sensemaking, which means the ability of authorities to properly recognize the saliency of crisis issues from the perspective of stakeholders and their framing ability to guide stakeholders’ expectations. Now the critical question is how should the government make sense of potential crises to provide the appropriate response and legitimization strategy? Here, by enumerating factors affecting crisis saliency and, hence, stakeholders’ expectations, this study presents its answer in the form of some theoretical propositions regarding the relationships between crisis saliency, value trade-off, and policy legitimization strategies.

Crisis saliency indicates the degree of noticeability and sensitivity that a crisis has on the part of stakeholders. The salient crises cause higher levels of cognitive arousal and public scrutiny. A review of the crisis management literature shows that three critical factors, among others, affect the saliency of a crisis:

The level of culpability; critical differences exist between human-induced crises and natural disasters. Weiner’s (1982) attribution theory (WAT) suggests that following a negative event, stakeholders make attributions about its cause. Making attributions involves a responsibility judgment that, in turn, results in cognitive and emotional arousal and consequent influencing behavior. Based on the responsibility judgment and the resulting level of culpability, Coombs (2006) draws a line between three clusters of crises: the victim cluster (such as natural disasters); the accidental cluster (such as technological breakdowns); and the preventable cluster (such as institutional misdeeds). Citizens and public stakeholders generally react more negatively to human-induced, preventable, and internally-caused crises than to natural disasters (Pearson & Mitroff, 1993). Therefore, the more stakeholders can put their finger on someone or something (government, maybe) as the agent behind a crisis or its effects, the more salient the crisis.

The degree of emergency; considering that crises unfold at different tempos, it is reasonable to distinguish slow-burning crises from fast-burning crises. ‘t Hart and Boin (2001) were the first scholars to use this distinction to typify events for crisis management. Fast-burning crises are instant and abrupt shocks, such as natural disasters, communities may cope, while slow-burning crises are gradual and creeping events, such as increasing rates of young unemployment and environmental crises, where there is political and scientific uncertainty about the solution to the issue (Seabrooke & Tsingou, 2019). Typically, as emergency politics shows, fast-burning crises are more salient than slow-burning ones.

The scope of impact; societal issues that a government may engage with can be viewed at three levels of local, regional, and global based on their scope of impact and the number of affected stakeholders; ranging from local issues such as unemployment to more significant regional issues such as the refugees’ wave (e.g., 2015 European migrant crisis), and to worldwide issues such 2008 financial crisis, global warming, and the worst, so far, COVID-19 pandemic. Generally, the larger the scope of negative impacts and the number of involved stakeholders, the more salient the issue and the more likely it turns into a mega-crisis (see Yen & Salmon, 2017; Lagadec, 2012).

Generally, the more noticeable the agent of a crisis issue, the faster its effects spread among the stakeholders, or, the more conflicting fundamental values it contains, the more salient the issue. Additionally, more salient crisis issues are more likely to be imposed upon authorities by stakeholders who urge them to allocate resources and take the necessary measures abruptly. The reason is that more salient crises are along with the high level of consensual stakeholders’ expectations. As the crisis’s saliency increases, the consequent consensus and convergence among the stakeholders make their expectations unanimous and unidirectional so that the correct response is already determined for the government. For example, a terrorist attack, a sweeping natural disaster, or even a social triggering event like a governmental scandal can amount to the most salient crisis to respond to. In these short periods of public emotionality and unanimity, the responsiveness of a government is more important than its effectiveness. Put differently, the most salient crises make it reasonable to abandon concerns about output legitimacy in favor of input legitimacy. In such situations, taking action or acknowledging the public is more important than the outcome of policy. Therefore, regarding the most salient crises, the very responsiveness of a government (i.e., input legitimacy), can maintain or even promote its legitimacy regardless of the policy outcome.

According to the value trade-off framework of Fiske and Tetlock (1997), most salient crises can be described as taboo trade-offs, where a sacred value (the “right” choice) such as public health is pitted against a secular value (the “wrong” choice) such as an economic lockdown. Making a taboo trade-off or even contemplating it would erode the legitimacy of the decision-maker (public authorities or policy-makers here). The reason is that the decision-maker is expected to choose the sacred value at the outset as the high and unidirectional stakeholders’ expectations have already marked the right option. Therefore, this study argues that when crises appear as taboo trade-offs accompanied by a high level of unanimous and unidirectional stakeholders’ expectations, sacrificing effectiveness in favor of responsiveness is reasonable and essential as well. Additionally, any significant delay, refusal to intervene, or resorting to inaction policy (McConnell & Hart, 2019) in this case is completely unacceptable.

Proposition 1a

considering the most salient crisis issues (i.e., high unidirectional stakeholders’ expectations), the overall crisismanship performance of a government is significantly determined by the input legitimacy.

Proposition 1b

considering the most salient crisis issues, taking an inaction policy is significantly and negatively associated with the overall government’s crisismanship performance.

Given the increasing rates of local and global crises, the above situation is not very uncommon and often marks the only perception of crises we are focused on. However, in many other crises, the initial triggering events and issues are more ambiguous (‘t Hart & Boin, 2001). For example, as Albala-Bertrand (2000) indicates, due to the institutional endogeneity of the triggering events, socially-made disasters (e.g., economic crises) are more complex and ambiguous than natural ones. In the case of a socially-made crisis, “both the causes and the solutions pertain to the societal realm, interacting in not very predictable ways” (p. 189), which leads to higher levels of complexity and ambiguity. On the flip side, the exogeneity of the natural crises’ causes and solutions decreases the situation’s complexity. The same is true for slow-burning crises and those that their behind agent is not evidently noticeable or that their scope of impact is limited. For example, even high rates of young unemployment or environmental crises may not reach more than a moderate level of saliency. In such crises, stakeholders’ values and interests are convergent but conflicting, leading to a high level of bidirectional or polarized stakeholders’ expectations. Polarized expectations moderate the overall saliency of crises. Such expectations are typically the result of higher degrees of disagreement between different stakeholders (including authorities, policy-makers, and the mass public) about the essential values and the way forward (Kingdon & Stano, 1984). These crises are usually at work where two or more sacred values collide, a tragic trade-off. The most recent instance is the COVID-19 pandemic, where due to the lockdown policy, the citizens’ right to “liberty” was pitted against “public health.“ The field of morality policy (Tatalovich et al., 2014) is marked by many morality issues calling for the policy-makers’ attention, such as abortion, sexual freedom, and euthanasia. These examples are the potential candidates for tragic trade-offs because of the sacred value conflicts (Hurka et al., 2017).

In a taboo trade-off, it is expected that the decision-maker immediately chooses the sacred value without any contemplation. However, in a tragic trade-off like this, a decision-maker should choose between two lesser devils. This situation requires a long contemplation and deliberation. Therefore, long contemplation and postponing the final decision in order to gain more certainty is the acceptable and legitimate behavior in a tragic situation (e.g., Gunia et al., 2012; Hanselmann & Tanner, 2008). Accordingly, in tragic situations, the quality of the policy-making process (or “effective policy design” in Knill’s, 2013: 310 words) is more important than the final choice (i.e., the policy outcome). This means that paying attention to the throughput legitimacy of crisis policies is the most appropriate strategy to increase the overall crisismanship performance (see proposition 2a). As discussed, throughput legitimacy had to do with efficacy, transparency, and openness of the policy-making process. Consequently, to the extent that a government can successfully frame a moderately salient crisis as a tragic trade-off, it can legitimately abandon the public requests for urgent action (i.e., input legitimacy) in favor of more deliberative policy-making (i.e., throughput legitimacy).

Nonetheless, it is obvious that using the legitimizing power of a deliberate process of policy-making (i.e., throughput legitimacy) is impossible without initial acknowledgment and responsiveness to moderately salient crises. This means that firstly the government should accept the status of the issue as a “crisis” by putting it on the agenda (see Proposition 2b). Therefore, the existence of a high, even though bidirectional, level of public stakeholders’ expectations regarding moderately salient crises would also necessitate the government’s responsiveness.

Proposition 2a

considering the moderately salient crisis issues (i.e., high bidirectional stakeholders’ expectations), the overall crisismanship performance of a government is significantly determined by the throughput legitimacy.

Proposition 2b

considering the moderately salient crisis issues, the input legitimacy has a significant but lesser effect on the overall government’s crisismanship performance than the throughput legitimacy.

Finally, the least salient crisis issues are those in which two or more secular values collide, that is, routine trade-offs. Many creeping and enduring social crises such as class inequalities or even natural disasters are manifested and framed in this form of value conflict. For example, besides the brutal economic impacts a pandemic would impose on some industries or stakeholders, it is not surprising that it can drastically increase the revenue of some others. This impact asymmetry, especially in economic terms or other secular areas, indicates potential slow-burning crises, which can be fertile soil for political maneuvering. Although in a normal situation, issues such as these cannot produce the political momentum needed to urge a government’s responsiveness, governments, politicians, and public stakeholders can charge and spotlight these issues via crisis promotion activities to pursue their political purposes (‘t Hart, & Boin, 2001). Therefore, while many scholars may exclude these issues from the main foci of crisis management, this study argues that crisismanship performance also depends on consciously considering and responding to these least salient crises. Far away from the stakeholders’ cognitive and political arousal threshold, responding and policy-making about the least salient crises can be done in the “black box” of governance (Schmidt, 2013), providing that the outcome would be acceptable in the end. This means that responsiveness and the quality of the policy-making process regarding these crises are not as important as the outcome of the policies. Accordingly, to the extent that governments can frame the least salient crises as routine trade-offs, they can reasonably abandon input and throughput legitimacy in favor of output legitimacy.

Proposition 3

considering the least salient crisis issues (i.e., the lowest level of stakeholders’ expectations), the overall crisismanship performance of a government is significantly determined by the output legitimacy.

Discussion

Navigating through the uncertainty of crises and coping with their governance performance fluctuating aspects are an undeniable fact of modern life. This situation increasingly challenges the policy performance, legitimacy, and capacity of governments. Actually, crisis events have become an important part of “larger, ongoing relationships” (Coombs & Holladay, 2002: 324) between public authorities and citizens. Therefore, crisismanship performance is an acid test of the governments’ credibility that can damage a quality relationship if mismanaged.

The crisismanship performance of modern governments depends on how they can maintain the precarious balance between effectiveness and responsiveness and how they can acquire the willing obedience and cooperation of stakeholders and the mass public through legitimizing crisis policies. Many scholars with different theoretical approaches have contributed to this fast-growing field of study. However, this study argues that policy legitimacy as a proxy for the quality of government-stakeholders relationships plays a critical role in crisismanship performance. Therefore, policy-makers can use the different types of policy legitimacy (i.e., input, throughput, and output legitimacy) to enhance their crisismanship performance. However, using inappropriate policy legitimacy to invest in can backfire. To address this problem, we suggest a value-based decision-making framework consisting of different types of value trade-offs (i.e., routine, tragic, and taboo) that policymakers can use as a basis for making sense of varying crisis issues. Once the situation is framed in this way, policy-makers can consciously choose the proper policy legitimacy to improve their crisismanship performance.

In particular, this study suggests three main theoretical propositions. First, the most salient crises, characterized by high unidirectional stakeholders’ expectations, can be framed as taboo trade-offs. In such situations, the vital role of input legitimacy can rule out the throughput and output legitimacy. Second, the moderately salient crises, characterized by high yet bidirectional levels of stakeholders’ expectations, can be regarded as tragic trade-offs in which the quality of the policy-making process (i.e., the throughput legitimacy) can significantly determine the crisismanship performance. Third, the least salient crises that yield the lowest level of stakeholders’ expectations can be considered routine trade-offs where the policy outcome (i.e., the output legitimacy) can make up for the lack of input and throughput legitimacy.

By providing policy-makers with a crisis diagnosis tool, the original model of this study contributes to the practice of crisismanship as a particular segment of governing activities. Crisismanship is becoming even more important as crises of all types pervade our societies. Policy-makers can use the model to maintain a mindful balance between effectiveness and responsiveness of governing activities in line with the managerial and political approaches to crisis management, respectively (‘t Hart & Boin, 2001). As the second contribution, this study suggests a new theoretical framework to reconcile and reintegrate different and even conflicting approaches to crisis management. Until now, abundant typologies of crises, crisis management approaches, and various types of policy legitimacy have been suggested. However, lacking from the literature is a dynamic value-based decisional framework to integrate these various contributions and guide policy-makers’ decision-making behavior. In order to address the existing gap, the present study offers a comprehensive model for assessing the salience of crises. This model takes into account three key factors: the level of culpability, the degree of emergency, and the scope of impact. By evaluating these factors, policymakers and researchers can utilize the framework to effectively determine the level of salience of a given crisis, and subsequently evaluate the appropriateness of the government’s response.

It is beyond the scope of this study to address the dynamics of crisismanship. However, it should be acknowledged that the policies’ time dimension and the processual nature of decision-making in crisismanship are of importance. It is quite possible and common that crises’ types change over time. This fact indicates that a crisis may need different kinds of trade-offs as it unfolds. Another important issue is that authorities can take an active role in framing and re-framing crises based on the involved trade-offs, which is a vital dynamic element in crisismanship performance. “How policy-makers can use the proposed value-based decision-making framework to manage the temporal and framing dynamics of crisis policies?“ is a key research question that future research can focus on more deeply.

Conclusion

Crisismanship is a sectoral example of the challenging act of balancing that governance systems are typically required to perform between responsiveness and effectiveness or between performance and legitimacy. On the one hand, without legitimacy, performance is often lost and meaningless, because the performers as well as the policy lack legitimacy. On the other hand, legitimacy without performance is also problematic and often short-lived as people expect to see actions that deliver results and satisfy needs (Farazmand, 1989), especially when citizens are engaged through “sound governance and collaborative organizations” (Farazmand, 2004). Here, the quality of governance depends on the balanced relationships that a political system re/constructs with its stakeholders, not on the “capacity and autonomy” of the bureaucratic system as Fukuyama (2013) argues, nor on merely delivering bundles of political good as Rotberg (2003, 2014) says. Accordingly, our conceptualization of crisismanship provides a “sectoral” manifestation of the “sound governance” as an inclusive, responsive, and both political and organizational/institutional governance system (Farazmand & Danaeefard, 2021; Farazmand, 2004). Contrary to “good governance”, in our integrative and more comprehensive “sound governance” framework, governance and its quality are not a transcendent and globalized way of thinking that can be imposed on the bureaucratic and instrumental level of local public administration (Farazmand, 2004). But, sound governance and its sectoral instantiation such as crisismanship are the indigenous emerging properties of a political system that harmonize its three levels of governance, public administration, and operations based on the dynamic balanced relationship with its stakeholders. In such a relationship, demonstrating the appropriate type of governance performance would create value for stakeholders as their expectations are considered by policymakers and would also benefit policymakers as the stakeholders would support and legitimize the policy.

In this way, policy legitimacy acts like a turning point that may improve or weaken the crisismanship performance of governments or their quality of governance. Regardless of its type, policy legitimacy reflects the quality of government-stakeholders relationships and determines policy performance. However, it should be noted that policy legitimacy can change over time and per policy. Different types of crises require different policies and hence, different types of policy legitimacy. While the crisis management literature is covered by a ton of crisis typologies, the public administration literature lacks this abundance. Particularly, there is a paucity of crisis categorization that could help ensure pertinent policy legitimacy. This is why this study suggests a contingency model (i.e., a value-based decision-making model) for selecting the proper legitimation strategies regarding crisis policies.

Funding Information

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Author Ali Farazmand is the editor-in-chief of the Public Organization Review journal.

Informed Consent

None.

Ethical Approval

None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ali Farazmand, Email: afarazma@fau.edu.

Hasan Danaeefard, Email: hdanaee@modares.ac.ir.

Seyed Hosein Kazemi, Email: h.kazemi@modares.ac.ir.

References

- ’t Hart P, Boin A. Between Crisis and Normalcy: The Long Shadow of Post-Crisis Politics. In: Rosenthal U, Boin A, Comfort LC, editors. Managing crises: Threats, Dilemmas, Opportunities. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Albala-Bertrand JM. Complex emergencies versus natural disasters: An analytical comparison of causes and effects. Oxford Development Studies. 2000;28(2):187–204. doi: 10.1080/713688308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardito L, Coccia M, Messeni Petruzzelli A. Technological exaptation and crisis management: Evidence from COVID-19 outbreaks. R&d Management. 2021;51(4):381–392. doi: 10.1111/radm.12455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron J, Spranca M. Protected values. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1997;70(1):1–16. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1997.2690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L. Crisis in Organizations: Managing and communicating in the heat of Chaos. Cincinnati, OH: College Divisions South-Western Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Beetham D. The legitimation of power. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press International, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bogliacino F, Charris R, Gómez C, Montealegre F, Codagnone C. Expert endorsement and the legitimacy of public policy. Evidence from Covid19 mitigation strategies. Journal of Risk Research. 2021;24(3–4):394–415. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2021.1881990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boin A, ’t Hart PT. Government institutions: Effects, changes and normative foundations. Dordrecht: Springer; 2000. Institutional crises and reforms in policy sectors; pp. 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Boin A, Busuioc M, Groenleer M. Building European Union capacity to manage transboundary crises: Network or lead-agency model? Regulation & Governance. 2014;8(4):418–436. doi: 10.1111/rego.12035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2016). The politics of crisis management: Public leadership under pressure. Cambridge University Press.

- Boswell C. Migration control and narratives of steering. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 2011;13(1):12–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-856X.2010.00436.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bundy J, Pfarrer MD, Short CE, Coombs WT. Crises and crisis management: Integration, interpretation, and research development. Journal of Management. 2017;43(6):1661–1692. doi: 10.1177/0149206316680030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon JK. Interpersonal expectations, expectancy violations, and emotional communication. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 1993;12(1–2):30–48. doi: 10.1177/0261927X93121003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. (2016). Useful complaints: How petitions assist decentralized authoritarianism in China. Lexington Books.

- Cho W. Change and continuity in police organizations: Institution, legitimacy, and democratization. The Korean journal of public policy studies. 2017;32(1):149–174. doi: 10.52372/kjps32107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen T, Lægreid P, Rykkja LH. Organizing for crisis management: Building governance capacity and legitimacy. Public Administration Review. 2016;76(6):887–897. doi: 10.1111/puar.12558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (2020). Balancing governance capacity and legitimacy: how the Norwegian government handled the COVID-19 crisis as a high performer. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 774–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coombs WT. The protective powers of crisis response strategies: Managing reputational assets during a crisis. Journal of Promotion Management. 2006;12(3–4):241–260. doi: 10.1300/J057v12n03_13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT, Holladay SJ. Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly. 2002;16(2):165–186. doi: 10.1177/089331802237233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deephouse, D. L., Bundy, J., Tost, L. P., & Suchman, M. C. (2017). “Organizational legitimacy: Six key questions.“ In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, 2nd edition, edited by Royston Greenwood, Christine Oliver, Thomas B. Lawrence and Renate E. Meyer. Sage

- Demiroz F, Unlu A. The role of government legitimacy and trust in managing refugee crises: The case of Kobani. Risk Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy. 2018;9(3):332–356. doi: 10.1002/rhc3.12143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denhardt, R. B., Denhardt, J. V., & Blanc, T. A. (2013). Public administration: An action orientation. Cengage Learning.

- Djanibekov N, Van Assche K, Valentinov V. Water governance in Central Asia: A luhmannian perspective. Society & Natural Resources. 2016;29(7):822–835. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2015.1086460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dolamore S, Lovell D, Collins H, Kline A. The role of empathy in organizational communication during times of crisis. Administrative Theory & Praxis. 2021;43(3):366–375. doi: 10.1080/10841806.2020.1830661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farazmand, A. (1989). The State, Bureaucracy, and Revolution: Agrarian Reform and Regime Politics in Modern Iran. Praeger.

- Farazmand, A. (2004). Sound governance: Policy and administrative innovations. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Farazmand A. Learning from the Katrina crisis: A global and international perspective with implications for future crisis management. Public Administration Review. 2007;67(s1):149–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00824.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farazmand A. Hurricane Katrina, the crisis of leadership, and chaos management: Time for trying the ‘surprise management theory in action’. Public Organization Review. 2009;9(4):399–412. doi: 10.1007/s11115-009-0099-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farazmand, A. (2014). Crisis and Emergency Management: Theory and practice (2nd edition.). CRC Press/Taylor and Francis.

- Farazmand, A. (2017). Global cases of best and worst practice in Crisis and Emergency Management. CRC Press/Taylor and Francis.

- Farazmand A, Danaeefard H. Iranian government’s responses to the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): An empirical analysis. International Journal of Public Administration. 2021;44(11–12):931–942. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2021.1903926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske AP, Haslam N. Social cognition is thinking about relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1996;5(5):143–148. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep11512349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske AP, Tetlock PE. Taboo trade-offs: Reactions to transactions that transgress the spheres of justice. Political Psychology. 1997;18(2):255–297. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- François M, Sud I. Promoting stability and development in fragile and failed states. Development Policy Review. 2006;24(2):141–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7679.2006.00319.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama F. What is governance? Governance. 2013;26(3):347–368. doi: 10.1111/gove.12035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunia BC, Wang L, Huang LI, Wang J, Murnighan JK. Contemplation and conversation: Subtle influences on moral decision making. Academy of Management Journal. 2012;55(1):13–33. doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.0873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanselmann M, Tanner C. Taboos and conflicts in decision making: Sacred values, decision difficulty, and emotions. Judgment and Decision Making. 2008;3(1):51–63. doi: 10.1017/S1930297500000164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honig B. Three models of emergency politics. boundary 2. 2014;41(2):45–70. doi: 10.1215/01903659-2686088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurka S, Adam C, Knill C. Is morality policy different? Testing sectoral and institutional explanations of policy change. Policy Studies Journal. 2017;45(4):688–712. doi: 10.1111/psj.12153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hybels RC. On legitimacy, Legitimation, and Organizations: A critical review and integrative theoretical model. Academy of Management Proceedings. 1995;1995(1):241–245. doi: 10.5465/ambpp.1995.17536509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2. NY: HaperCollins College Publisher; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW, Stano E. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown; 1984. pp. 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Knill C. The study of morality policy: Analytical implications from a public policy perspective. Journal of European Public Policy. 2013;20(3):309–317. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2013.761494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lagadec P. The Megacrisis unknown territory: In search of conceptual and strategic breakthroughs. In: Rosenthal U, Jacobs B, Comfort LK, Helsloot I, editors. Megacrises. Springfield, IL: CC Thomas; 2012. pp. 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, Sacks A. Legitimating beliefs: Concepts and indicators. Cape Town, South Africa: Afrobarometer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. (2020). Theory of society, volume 1. Stanford University Press.

- Ma L, Christensen T. Government trust, social trust, and citizens’ risk concerns: Evidence from crisis management in China. Public Performance & Management Review. 2019;42(2):383–404. doi: 10.1080/15309576.2018.1464478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell A, Hart PT. Inaction and public policy: Understanding why policy-makers ‘do nothing’. Policy Sciences. 2019;52(4):645–661. doi: 10.1007/s11077-019-09362-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nohrstedt D, Weible CM. The logic of policy change after crisis: Proximity and subsystem interaction. Risk Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy. 2010;1(2):1–32. doi: 10.2202/1944-4079.1035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos O. Economic crisis and youth unemployment: Comparing Greece and Ireland. European Journal of Industrial Relations. 2016;22(4):409–426. doi: 10.1177/0959680116632326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CM, Mitroff II. From crisis prone to crisis prepared: A framework for crisis management. Academy of Management Perspectives. 1993;7(1):48–59. doi: 10.5465/ame.1993.9409142058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pesch U. The publicness of public administration. Administration & Society. 2008;40(2):170–193. doi: 10.1177/0095399707312828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal U, Kouzmin A. Globalizing an agenda for contingencies and crisis management: An editorial statement. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 1993;1(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.1993.tb00001.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rotberg RI. Failed states, collapsed states, weak states: Causes and indicators. State failure and state weakness in a time of terror. 2003;1:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rotberg RI. Good governance means performance and results. Governance. 2014;27(3):511–518. doi: 10.1111/gove.12084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier P, Jenkins-Smith H. Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf FW. The joint-decision trap: Lessons from german federalism and european integration. Public Administration. 1988;66(3):239–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.1988.tb00694.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Governing in Europe: Effective and democratic? Oxford University Press.

- Scharpf FW. Legitimacy in the multilevel european polity. European Political Science Review. 2009;1(2):173–204. doi: 10.1017/S1755773909000204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt VA. Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: Input, output and ‘throughput’. Political Studies. 2013;61(1):2–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V. A. (2020). Europe’s crisis of legitimacy: Governing by rules and ruling by numbers in the eurozone. Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt VA. European emergency politics and the question of legitimacy. Journal of European Public Policy. 2022;29(6):979–993. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2021.1916061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker PJ, Tetlock PE. Taboo scenarios: How to think about the unthinkable. California Management Review. 2012;54(2):5–24. doi: 10.1525/cmr.2012.54.2.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seabrooke L, Tsingou E. Europe’s fast-and slow-burning crises. Journal of European Public Policy. 2019;26(3):468–481. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1446456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman PG. The concept of legitimacy. Polity. 1974;7(1):32–56. doi: 10.2307/3234268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suchman MC. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review. 1995;20(3):571–610. doi: 10.2307/258788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tankebe J. Viewing things differently: The dimensions of public perceptions of police legitimacy. Criminology. 2013;51(1):103–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00291.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatalovich, R., Daynes, B. W., & Lowi, T. J. (2014). Moral controversies in american politics. Routledge.

- Tokakis V, Polychroniou P, Boustras G. Crisis management in public administration: The three phases model for safety incidents. Safety Science. 2019;113:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2018.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tregidga H, Laine M. On crisis and emergency: Is it time to rethink long-term environmental accounting? Critical Perspectives on Accounting. 2022;82:102311. doi: 10.1016/j.cpa.2021.102311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TR. Governing and diversity: The effect of fair decision-making procedures on the legitimacy of government. Law & Society Review. 1994;28(3):809–831. doi: 10.2307/3053998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TR. Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57(1):375–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentinov V, Roth S, Will MG. Stakeholder theory: A luhmannian perspective. Administration & Society. 2019;51(5):826–849. doi: 10.1177/0095399718789076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner J. Legitimacy and public policy: Seeing beyond effectiveness, efficiency, and performance. Policy Studies Journal. 2008;36(3):421–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00275.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. (1982). An attribution theory of motivation and emotion. Series in Clinical & Community Psychology: Achievement Stress & Anxiety, 223–245.

- White J. Authority after emergency rule. The Modern Law Review. 2015;78(4):585–610. doi: 10.1111/1468-2230.12130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yen, V. Y. C., & Salmon, C. T. (2017). Further explication of mega-crisis concept and feasible responses. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 33).