Abstract

The early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated stay-at-home orders resulted in a stark reduction in daily social interactions for children and adolescents. Given that peer relationships are especially important during this developmental stage, it is crucial to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social behavior and risk for psychopathology in children and adolescents. In a longitudinal sample (N=224) of children (7–10y) and adolescents (13–15y) assessed at three strategic time points (before the pandemic, during the initial stay-at-home order period, and six months later after the initial stay-at-home order period was lifted), we examine whether certain social factors protect against increases in stress-related psychopathology during the pandemic, controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms. Youth who reported less in-person and digital socialization, greater social isolation, and less social support had worsened psychopathology during the pandemic. Greater social isolation and decreased digital socialization during the pandemic were associated with greater risk for psychopathology after experiencing pandemic-related stressors. In addition, children, but not adolescents, who maintained some in-person socialization were less likely to develop internalizing symptoms following exposure to pandemic-related stressors. We identify social factors that promote well-being and resilience in youth during this societal event.

Keywords: Developmental psychopathology, social behavior, adolescence, stress, life events

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unparalleled changes to the lives of children and adolescents. To contain the spread of the virus, public health officials recommended social distancing measures and many cities adopted stay-at-home orders during the early stages of the pandemic. These social distancing measures resulted in a sudden and stark reduction in daily social interactions for children and adolescents, including school closures, disrupted extracurricular activities, and limited socializing with peers. These declines in social interaction have had meaningful consequences for youth wellbeing. Given that peer relationships are especially important during this developmental stage, it is crucial to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social experiences and risk for psychopathology in youth. In a longitudinal sample assessed at three strategic timepoints—prior to the pandemic, during the initial stay-at-home orders, and after the initial stay-at-home orders were lifted six months later—we examine how the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the social lives of children and adolescents, and whether certain social factors mitigated worsening internalizing and externalizing problems or buffered against stress-related psychopathology during the pandemic.

Over the past two years, much work has focused on the unprecedented challenges the COVID-19 pandemic has created for families (i.e., illness, unemployment) and the associated increase in psychopathology in children and adults (Achterberg et al., 2021; Barendse et al., 2022; Chahal et al., 2020; Ellis et al., 2020; Fegert et al., 2020; Gassman-Pines et al., 2020; Gruber et al., 2020; Hawes et al., 2021; Holman et al., 2020; Loades et al., 2020; Patrick et al., 2020; Pfefferbaum & North, 2020; Pierce et al., 2020; Racine et al., 2020). However, there has been less focus on the impact of the pandemic on the social lives of children and adolescents. Difficulties in peer relationships are strongly associated with youth psychopathology (La Greca & Lopez, 1998; Platt et al., 2013). Higher levels of peer-related stressors (La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Siegel et al., 2009), being rejected or excluded from peer groups (Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003; Nolan et al., 2003; Prinstein & Aikins, 2004; Rudolph et al., 2011), and feelings of loneliness (Erzen & Çikrikci, 2018; Witvliet et al., 2010) are each associated with elevated risk for anxiety and depression. As such, we hypothesized that the pervasive disruptions in social activities related to the pandemic and social distancing measures may contribute to risk for mental health problems by reducing in-person socialization, increasing isolation, and reducing access to social support.

Given that social communication through mobile devices has become one of the most prominent modes of peer communication among adolescents (Lenhart et al., 2010), it is also important to consider the ways in which peer interactions through digital means may relate to adolescent wellbeing during the pandemic. On the one hand, digital socialization can facilitate positive peer interactions, and it is possible that youth who maintain connections using digital technology may be less likely to experience mental health problems during the pandemic. Some work suggests that youth who engage in digital socialization experience lower levels of loneliness, stronger relational bonds, increased perceived social support, and fewer internalizing symptoms (George et al., 2018; Padilla-Walker et al., 2012), particularly following social exclusion (Knowles et al., 2015). On the other hand, digital socialization provides ample opportunity for negative peer interactions online, which have been associated with increased depression symptoms (Landoll et al., 2015). Moreover, especially high volumes of digital communication have been associated with greater symptoms of depression and anxiety (Coyne et al., 2019; Redmayne et al., 2013; Roser et al., 2016). In fact, one study showed that young adults who engaged in high levels of texting experienced greater emotional distress following interpersonal stressors (Murdock, 2013). However, previous work has primarily been conducted outside of the context of such stark reductions of social interactions in-person, such as during the current pandemic, when socialization of any kind, including digital, may have increased importance. Therefore, we hypothesized that increased digital social interactions in the context of reduced in-person interactions relates to enhanced wellbeing among youth during the early stages of the pandemic.

We also examine whether maintenance of social relationships during the pandemic protected youth from psychopathology following exposure to pandemic-related stressors. Exposure to stress is a well-established risk factor for internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in children and adolescents (Grant et al., 2003, 2004; McLaughlin, 2016; McLaughlin et al., 2012). Social support is a key protective factor known to buffer against the onset of psychopathology following stressful life events (Herman-Stahl & Petersen, 1996; Pine & Cohen, 2002; Trickey et al., 2012), such that adolescents who report greater social support and higher quality friendships are less likely to develop psychopathology following exposure to stressors (Alto et al., 2018; Gaertner et al., 2010; Harmelen et al., 2017; Havewala et al., 2019; Mackin et al., 2017; Trickey et al., 2012). Thus, we hypothesized that maintenance of positive social bonds early on in the pandemic may mitigate the negative effects of pandemic-related stressors. Indeed, recent work has shown that positive relationships may buffer adolescents from psychological stress during the pandemic (Asscheman et al., 2021; Cohodes et al., 2021; Wright & Wachs, 2022). Determining whether certain social factors confer resilience against stress-related psychopathology during the pandemic is important for theory and practice. Research in this area is needed, as underscored by calls to identify concrete, actionable protective factors for youth mental health during the pandemic (de Figueiredo et al., 2021).

The consequences of pandemic-related changes in social experiences may have been particularly pronounced for adolescents. Adolescence is a developmental phase characterized by dramatic changes in the complexity of social roles and experiences (Crone & Dahl, 2012). Peer relationships become especially important and adolescents show increased preoccupation with social belonging (Somerville, 2013). Compared to children, adolescents spend more time with peers than family (Lam et al., 2014; Larson, 2001), are more sensitive to peer evaluation (Rodman et al., 2017; Somerville et al., 2013; Stroud et al., 2009), and are increasingly dependent on peer relationships (Brown, 1990). Some have argued that social isolation is particularly detrimental during adolescence (Orben et al., 2020), and this may be especially true in the context of this pandemic (Fegert et al., 2020; Loades et al., 2020). As such, we hypothesized that social experiences during the early stages of the pandemic are more strongly associated with risk for psychopathology in adolescents than children.

Emerging research has begun to examine this critical area of investigation. Researchers have found that a primary concern of adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic was disconnection from friends (Ellis et al., 2020; Magson et al., 2021; McKinlay et al., 2022; Silk et al., 2021). Less time with family and friends during the pandemic was also associated with internalizing problems (Ellis et al., 2020). In addition, reported feelings of disconnection, lack of support, alienation, and conflict within parental and peer relationships were associated with increased internalizing symptoms (Campione-Barr et al., 2021; Espinoza & Hernandez, 2022; Houghton et al., 2022; Hutchinson et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2022; Magson et al., 2021; Qi et al., 2020; Silk et al., 2021; M.-T. Wang et al., 2021, 2022) and mood volatility (Asscheman et al., 2021; Green et al., 2021) during the pandemic. Critically, there is a need for studies that have examined whether social factors promote resilience in the face of pandemic-related stressors. One study has explored whether time spent socializing moderates the relationship between stress and depression during the pandemic, finding no such effect (Ellis et al., 2020); however, this study did not account for pre-pandemic symptoms or examine more established protective factors such as social connection or support. Others examining the impact of peer and parental relationship quality on stress-related adjustment find mixed-effects (Campione-Barr et al., 2021; Espinoza & Hernandez, 2022). Further, studies have yet to examine age-related differences in these effects across childhood and adolescence. The current study addresses this gap in the literature by contributing the first study completed in both children and adolescents across three key time points (i.e., pre-pandemic, during the initial stay-at-home orders, and after the initial stay-at-home orders were lifted) and examining various social factors (i.e., socialization, social isolation, social support) that predict psychopathology and moderate the link between pandemic-related stress exposure and psychopathology.

We examined these questions in a longitudinal sample of children and adolescents whose mental health was comprehensively assessed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were recruited from two ongoing longitudinal studies (Rosen, Hagen, et al., 2019; Rosen, Meltzoff, et al., 2019) of children (aged 7–10) and adolescents (aged 13–15) in the greater Seattle, WA area. We assessed social behaviors and experiences during the early stages of the pandemic, pandemic-related stressors, and internalizing and externalizing symptoms during six weeks between April and May of 2020 pandemic—a period when initial stay-at-home orders were in place (Wave 1). We again measured symptoms of psychopathology six months later between November 2020 and January 2021, after the initial stay-at-home orders were lifted (Wave 2). First, we examined how the pandemic and associated stay-at-home orders influenced in-person and digital socialization. Next, we investigated whether social factors (i.e., socialization, social isolation, social support) during the pandemic were concurrently and prospectively associated with increases in internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, controlling for pre-pandemic psychopathology. We additionally examined whether social factors (i.e., socialization, social isolation, social support) during the pandemic moderated the association of pandemic-related stressors with concurrent or prospective increases in internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, controlling for pre-pandemic psychopathology. Finally, we tested whether any of these associations varied by age to determine whether these associations were similar for children and adolescents.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from two ongoing longitudinal studies (Lengua et al., 2015; Rosen, Meltzoff, et al., 2019) of children and adolescents in the greater Seattle, WA area about environmental experiences, cognitive development, and mental health (more details below). A sample of 224 children (aged 7–10) and adolescents (aged 13–15) and their caregivers completed a battery of questionnaires to assess social behaviors and experiences, pandemic-related stressors, and symptoms of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology during the initial stay-at-home orders of the pandemic. Six months later, after the initial stay-at-home-orders were lifted, 188 participants and caregivers again completed an assessment of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The racial and ethnic background of participants reflected the Seattle area, with 66% of participants identifying as White, 11% as Black, 11% as Asian, 8% as Hispanic or Latino, and 3% as another race or ethnicity. These two samples came from community-based samples of the same general population (youth in the Seattle area) from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds, as measured by the income-to-needs ratio (MSES =3.95, SDSES =1.83, range: 0.35–8.41). Critically, these two samples did not differ with regards to socioeconomic status, sex distribution, or in exposure to pandemic-related stressors (ps > .80).

Child participants, aged 7–10 years at the time of the current study, were drawn from a parent study examining the associations between the home environment, cognitive development, and mental health (Rosen, Hagen, et al., 2019; Rosen, Meltzoff, et al., 2019). The original sample (N=90) had completed a prior assessment of mental health between March 2018 and November 2018 at the age of 6–8 years. All 90 participants were contacted for the current study. Of this sample, 70 caregiver/child pairs participated in the current study during the initial stay-at-home order period (Wave 1; retention rate: 77% of the original sample; Mage = 8.88, range: 7.64 – 10.21, 51% female) and 55 caregiver/child pairs completed a follow-up assessment six months later (Wave 2), after the initial stay-at-home order period was lifted. Mental health assessments from prior to the pandemic (2018) were used to control for pre-pandemic psychopathology. Three participants had not completed the 2018 assessment, therefore a previous mental health assessment from January 2016 – September 2017 at age 5–6 was used as a measure of pre-pandemic psychopathology. Five additional children (not included in Wave 2 N=55 above) completed the mental health assessment at the six-month follow-up after the stay-at-home order period, but had not completed the assessment during the initial stay-at-home orders, and are not included in analyses.

Adolescent participants, aged 13–15 years at the time of the current study, were drawn from a second parent study investigating early environmental experiences, cognitive development, and mental health (Lengua et al., 2015). The original sample (N=227) had completed a prior assessment of mental health between June 2017 and October 2018 at the age of 11–12 years. All 227 participants were contacted for the current study. Of this sample, 154 caregiver/adolescent pairs participated in the current study during the initial stay-at-home order period (Wave 1; retention rate: 68% of the original sample, Mage = 14.3, range: 13.12 – 15.24, 46% female) and 122 caregiver/adolescent pairs completed a follow-up assessment six months later (Wave 2), after the initial stay-at-home orders had been lifted. Mental health assessments from prior to the pandemic (2017–2018) were used to control for pre-pandemic psychopathology. Eight additional adolescents (not included in Wave 2 N=122 above) completed the mental health assessment at the six-month follow-up after the initial stay-at-home order period, but had not completed the assessment during the initial stay-at-home orders, and are not included in analyses.

Participants were excluded from the parent studies based on the following criteria: IQ < 80, active substance dependence, psychosis, presence of pervasive developmental disorders (e.g., autism), and psychotropic medication use. Across both samples, legal guardians provided informed consent and youth provided assent via electronic signature obtained using Qualtrics (Provo, UT). All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Harvard University. Youth and their caregivers were each paid $50 for participating in the first wave of the study and $35 for the second wave.

Procedure

Once consent was obtained, parents and children completed surveys separately. Data were collected from three critical time points: 1) mental health assessments prior to the pandemic; 2) pandemic-related experiences and mental health assessments during initial stay-at-home orders between April and May of 2020 (Wave 1); and 3) mental health assessments six months later between November 2020 and January 2021, after the initial stay-at-home orders were lifted (Wave 2). Stay-at-home orders and public school closures persisted throughout the entire data collection period of Wave 1.

Pandemic-related Stressors

We developed a novel questionnaire to assess pandemic-related stressors (https://osf.io/drqku/). The assessment included health, financial, social, school, and physical environment stressors that occurred within the preceding month, based on both caregiver and child report (See Table S1). Given that the COVID-19 pandemic presented a wide range of unique stressors that have not occurred in prior community-wide disruptions, it was necessary to create a novel measure to assess these types of experiences. It is standard practice in the field to do so when novel events occur for which existing stress measures do not adequately capture the full extent of specific types of stressful experiences (e.g., to understand the unique hurricane-related stressors that occurred during Hurricane Katrina or experiences specific to the terrorist attacks on September 11th or the Oklahoma City bombing (Galea et al., 2002, 2007; Mclaughlin et al., 2009; Pfefferbaum et al., 2000).

We created a composite of pandemic-related stressors using a cumulative risk approach (Evans et al., 2013), by determining the presence of each potential stressor (exposed versus not exposed), and creating a risk score reflecting a count of these stressors. This count of exposure to pandemic-related stressors was used as the measure of pandemic-related stress exposure in analyses. All items were based on child/adolescent report unless otherwise noted. To probe health-related stressors, we included five items to assess whether participants, their family members, or a close friend/partner contracted COVID-19, whether someone they knew died from COVID-19, and whether their parent was an essential worker during the pandemic (parent report), each scored as a yes/no. Of note, these questions assessed health-related stress before mitigating factors, such as availability of vaccines, and novel variants arose. To probe financial-related stressors, we included four items based on parent report to assess whether a parent was laid off/experiencing sudden lack of employment, family experienced food insecurity (based on a validated measure, Blumberg et al., 1999), family was evicted or otherwise forced to leave their home due to financial hardship, or family experienced significant financial losses, scored as yes/no. To probe social stressors, we included three items to assess whether participants had a difficult relationship with a parent or other household member that had worsened during the pandemic and whether they or someone in the household was experiencing racism, prejudice, or discrimination related to the pandemic, scored as yes/no. Finally, three items probed other stressors likely to have been impacted by the pandemic, including whether there was crowding in the home (total number of people / home square footage; based on parent report using a validated measure (Evans, 2006)), difficulty getting schoolwork done at home, and whether the environment where schoolwork was done is noisy, scored as yes/no. Of each of the pandemic-related stress domains, the social and school-related stressors had the strongest association with psychopathology (Table S2).

Social Behaviors and Experiences

In the same survey, we also included a set of questions that probed social behaviors and experiences during the pandemic while initial stay-at-home orders were in place and asked participants (child/adolescent report only) to respond to survey items reflecting the previous thirty days (https://osf.io/drqku/). The social factors examined included: a) change in in-person and digital socialization; b) feelings of social isolation from peers; and c) perceived support from peers. In-person socialization was assessed with questions regarding the frequency and duration of time spent with peers outside of the household. This measure was based on two items, “How often do you see your friends?” and “How much time per day do you spend socializing with non-household members?” which were both scored on a 1–6 Likert scale from “Never” to “Multiple times a day” and “None” to “6 or more hours,” respectively. Digital socialization was assessed with questions examining frequency and duration of interactions with peers via various digital means (i.e., texting, phone calls, video calls, messaging apps, and social media). This measure was based on five items, “How often do you speak to your friends by phone call/text/social media/other apps?” and “How much time per day do you spend socializing with non-household members?” which were both scored on a 1–6 Likert scale from “Never” to “Multiple times a day” and “None” to “6 or more hours,” respectively. We also asked participants to retroactively indicate their typical level of these social interactions before the pandemic. This allowed for analyses examining the relative change in participants’ socialization compared to pre-pandemic levels. For analyses examining absolute levels, see Table S3. Social isolation was assessed with questions probing feelings of social connection, missing friends, and loneliness. This measure was based on three items: 1) “Do you feel more or less connected to close friends?” reverse scored on a 1–5 Likert scale from “Much less connected” to “Much more connected”; 2) “How much have you missed being with close friends?” scored on a 1–4 Likert scale from “Not at all“ to “Very”; and 3) “How often have you felt lonely?” scored on a 1–5 Likert scale from “Never” to “Nearly every day.” Finally, social support was assessed using a validated questionnaire of six items (Harter, 1985) that probed relationship quality and emotional support from peers. Items included whether participants had a close friend who “I could tell problems to,” “really understands me,” “I can talk to about things that bother me,” “I like to spend time with,” “really listens to what I say,” and “cares about my feelings” scored on a 1–4 Likert scale from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree.” For analyses examining parental support, see Table S3. See Table S4 for items, scoring, and reliability metrics.

Internalizing and Externalizing Psychopathology

Psychopathology was assessed prior to the pandemic by caregiver and child report on the Youth Self Report (YSR) and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), respectively (Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach et al., 2003). The YSR and CBCL scales are among the most widely used measures of youth emotional and behavioral problems and use normative data to generate age-standardized estimates of the severity of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. We used the Internalizing and Externalizing symptoms subscales from the youth and caregiver report and used the highest reported symptom value across the two reporters as measures of pre-pandemic Internalizing and Externalizing symptoms. The use of the higher caregiver or child report for psychopathology is an implementation of the standard “or” rule used in combining caregiver and child reports of psychopathology. In this approach, if either a parent or child endorses a particular symptom it is counted with the assumption that if a symptom is reported, it is likely present. This is a standard approach in the literature on child psychopathology–for example it is how mental disorders are diagnosed in population-based studies of psychopathology in children and adolescents (Kessler et al., 2012; Merikangas et al., 2010).

To assess psychopathology during the pandemic, both caregivers and youth completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a widely-used assessment of mental health in youth that consists of 25 items, and includes subscales assessing internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (R. Goodman, 2001). The SDQ has good reliability and validity (Dickey & Blumberg, 2004; A. Goodman et al., 2010) and correlates strongly with the CBCL/YSR (R. Goodman & Scott, 1999). We chose to use the SDQ to reduce participant burden, as it has substantially fewer items than the CBCL/YSR. We used the Internalizing and Externalizing symptoms subscales from the youth and caregiver report and used the highest reported symptom value across the two reporters as measures of Internalizing and Externalizing symptoms during the pandemic. When compared to recent longitudinal studies and systematic reviews (Barendse et al., 2022; Fegert et al., 2020; Hawes et al., 2021; Racine et al., 2020) the magnitude of symptom increase from before to during the pandemic in the current sample is consistent with that seen in previous work (i.e., 2–3x increase), lending confidence in this approach.

Statistical Analysis

We first examined whether levels of social behavior changed from before to during the pandemic while initial stay-at-home orders were in place. To do so, we estimated mixed-effects linear regression models with socialization (i.e., in-person, digital) as the outcome, a covariate indicating pre vs. during the pandemic, and subject as a random effect. All regression analyses were carried out in a using lme4 package (Bates & Maechler, 2018) in R (R Core Team, 2020).

Next, we examined whether social behaviors and experiences were associated with psychopathology during the pandemic, while controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms. To test this, we estimated linear regression models with internalizing or externalizing symptoms as the outcome, social experiences as the predictor (i.e., socialization, social isolation, social support) and pre-pandemic levels of internalizing or externalizing symptoms as a covariate.

Finally, we investigated whether social behaviors and experiences moderated the association between pandemic-related stressors and psychopathology during the pandemic, controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms. To do so, we estimated linear regression models with internalizing or externalizing symptoms as the outcome, pandemic-related stressors as the predictor, and social experiences (i.e., socialization, social isolation, social support) as the moderator, and pre-pandemic symptoms as a covariate.

Separate models examined predictors assessed concurrently with psychopathology symptoms during the initial stay-at-home order period, and prospective associations with psychopathology six months later, after the initial stay-at-home orders were lifted. Age and sex were included as covariates in all models. To examine age-related differences, we included age as a moderator to each of the models above to examine whether observed associations differed for children and adolescents. Simple slopes analysis using a binary variable for children (ages 7–10) and adolescents (ages 13–15) was used to follow-up on significant age interactions using the pequod package (Mirisola & Seta, 2016) in R (R Core Team, 2020). Standardized coefficients are presented below. Analyses were not pre-registered. All code and data for the current study are posted to Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/7fs2r/.

Results

Pandemic-related changes in social behavior

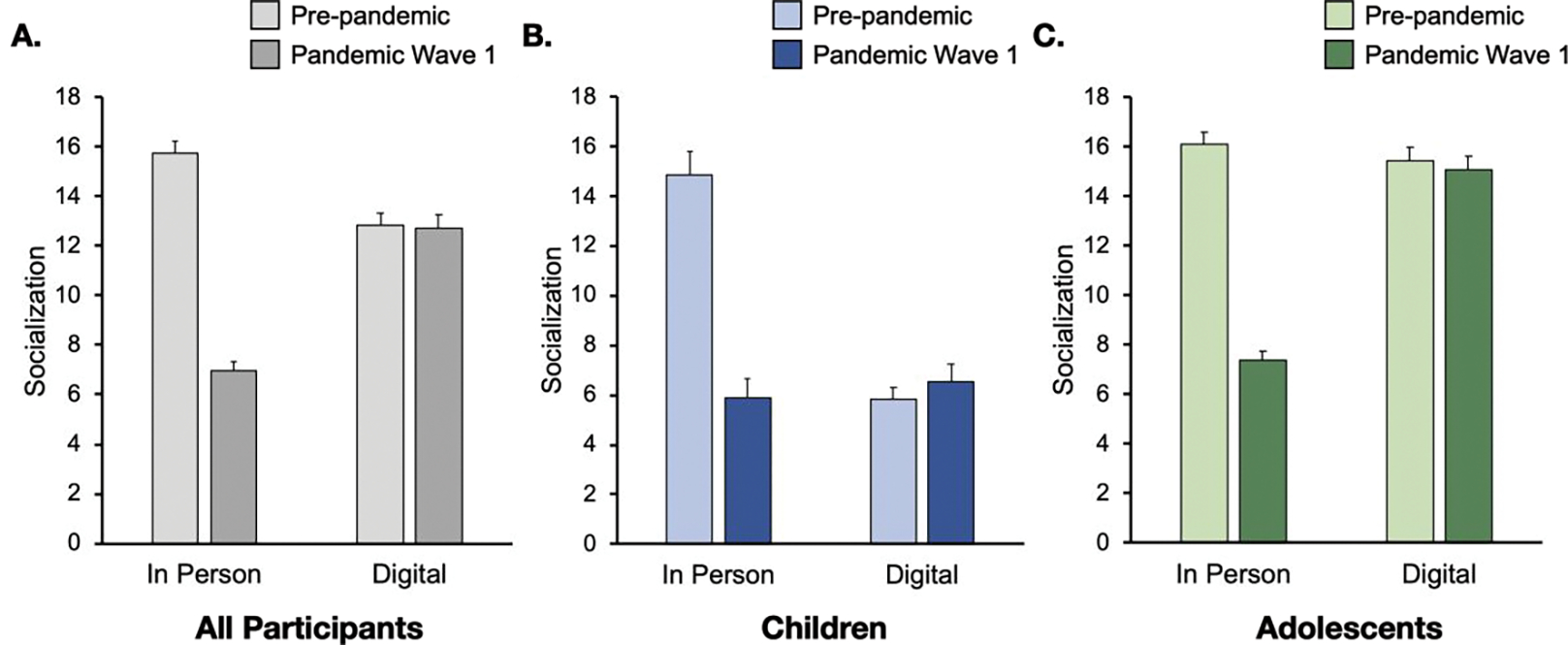

We examined changes in social behavior from before the pandemic to during pandemic while the initial stay-at-home orders were in place. Youth reported a significant decline in in-person socialization (β=1.049, p<.001), whereas digital socialization did not change (β=0.037 p=.501). Changes in socialization did not differ by age (ps>.182) (Figure 1). See Supplemental Materials for descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations tables (Tables S5 and S6).

Figure 1.

Socialization behaviors before and during the early stages of the pandemic while initial stay-at-home orders were in place (Wave 1). A. Across all participants, steep declines in in-person socialization were reported, whereas digital socialization remained about the same. B-C. Both children and adolescents showed this pattern, although adolescents engaged in more digital socialization than children, overall. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SE).

Social behavior and psychopathology

We then examined how changes in-person and digital socialization from before to during the pandemic were associated with psychopathology, while controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms. We did not find significant associations between changes in levels of in-person and digital socialization and internalizing or externalizing symptoms during or after the initial stay-at-home orders (ps>.124; Table 1). There were no age-related differences in the association between changes in socialization and psychopathology (ps>.233). Secondary analyses examining these associations with absolute levels of in-person and digital socialization during the pandemic can be found in Table S3.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for all models

| Pandemic-related changes in socialbehavior | In-person | Digital | ||||||

| β | p-value | β | p-value | |||||

| Pre vs. post pandemic | 1.049 | < 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.501 | ||||

| Pre vs. post pandemic by Age | −0.017 | 0.818 | 0.075 | 0.182 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Social behavior and vsvchovathologv | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | ||||||

| Internalizing | Externalizing | Internalizing | Externalizing | |||||

| Social behaviors | β | p-value | β | p-value | βitalic | p-value | β | p-value |

| Change in in-person socialization | 0.020 | 0.751 | 0.032 | 0.611 | −0.041 | 0.573 | −0.003 | 0.969 |

| Change in digital socialization | −0.001 | 0.983 | −0.015 | 0.809 | −0.114 | 0.124 | 0.031 | 0.673 |

| Social isolation | 0.234 | < 0.001 | 0.289 | < 0.001 | 0.241 | 0.001 | 0.185 | 0.010 |

| Peer support | −0.234 | < 0.001 | −0.060 | 0.358 | −0.195 | 0.007 | −0.040 | 0.579 |

| Social behaviors by Age | ||||||||

| Change in in-person socialization | 0.096 | 0.308 | 0.064 | 0.486 | 0.019 | 0.855 | −0.101 | 0.330 |

| Change in digital socialization | 0.079 | 0.233 | −0.055 | 0.401 | 0.063 | 0.397 | −0.086 | 0.238 |

| Social isolation | 0.104 | 0.733 | 0.095 | 0.749 | −0.406 | 0.242 | 0.305 | 0.382 |

| Peer support | −0.631 | 0.036 | −0.501 | 0.104 | 0.087 | 0.816 | 0.117 | 0.758 |

|

| ||||||||

| Social moderation of stress-related vsvchovathologv | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | ||||||

| Internalizing | Externalizing | Internalizing | Externalizing | |||||

| Social behaviors | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value |

| Change in in-person socialization | −0.161 | 0.223 | −0.097 | 0.467 | −0.277 | 0.082 | −0.110 | 0.470 |

| Change in digital socialization | −0.051 | 0.632 | −0.072 | 0.509 | −0.274 | 0.034 | −0.167 | 0.180 |

| Social isolation | 1.310 | < 0.001 | 0.819 | 0.016 | 0.482 | 0.241 | 0.331 | 0.406 |

| Peer support | 0.527 | 0.069 | −0.286 | 0.340 | 0.099 | 0.772 | −0.215 | 0.522 |

| Social behaviors by Age | ||||||||

| Change in in-person socialization | 0.599 | 0.003 | −0.087 | 0.680 | 0.314 | 0.213 | 0.098 | 0.684 |

| Change in digital socialization | 0.196 | 0.111 | 0.116 | 0.358 | 0.038 | 0.799 | 0.155 | 0.270 |

| Social isolation | −0.808 | 0.128 | 0.723 | 0.182 | −0.416 | 0.530 | −0.391 | 0.544 |

| Peer support | 0.044 | 0.926 | −0.229 | 0.645 | −0.160 | 0.787 | −0.606 | 0.301 |

Note: all models examining symptoms as outcomes controlled for pre-pandemic symptoms. Wave 1 refers to the assessment conducted at the start of the pandemic between April and May 2020, Wave 2 refers to the assessment conducted six months later between November 2020 and January 2021; β = standardized coefficient; Bold denotes significant effect.

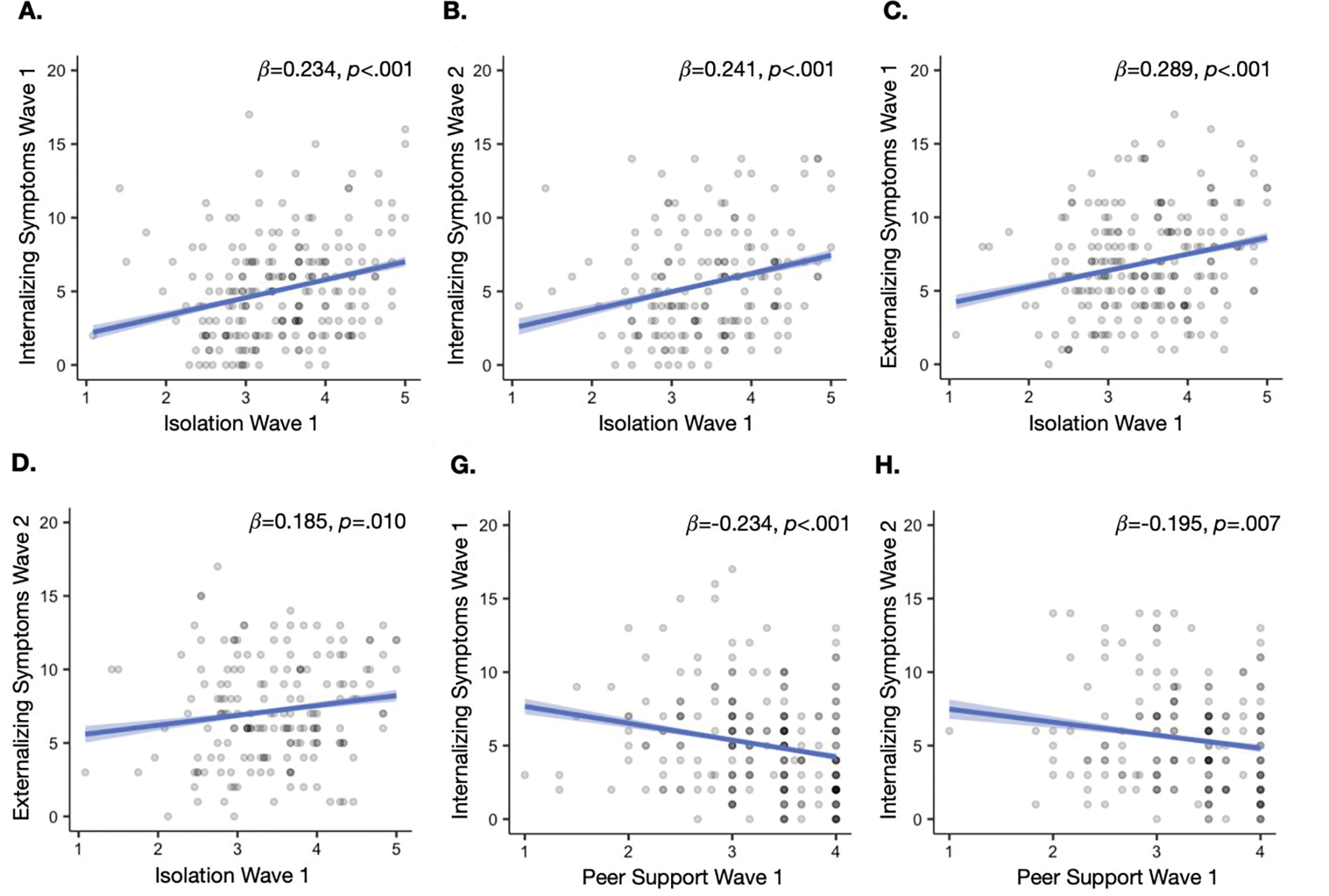

Youth reported moderate levels of isolation, such as feeling less connected to friends relative to before the pandemic, missing friends, and feeling lonely a few times a month during the initial stay-at-home order period. Greater peer isolation was concurrently and prospectively associated with increased internalizing (β=0.234, p<.001; β=0.241, p<.001, respectively) and externalizing symptoms (β=0.289, p<.001; β=0.185, p=.010, respectively) (Figure 2). There were no age-related differences in peer isolation and its relation to psychopathology (ps>.242)

Figure 2.

Associations between social experiences and psychopathology. Greater isolation during the early stages of the pandemic was associated with worsened internalizing and externalizing symptoms at Wave 1 and 2 (A-D). Lower levels of peer support during the early stages of the pandemic were associated with worsened internalizing symptoms at Wave 1 and 2 (G, H). Shaded region indicates SE.

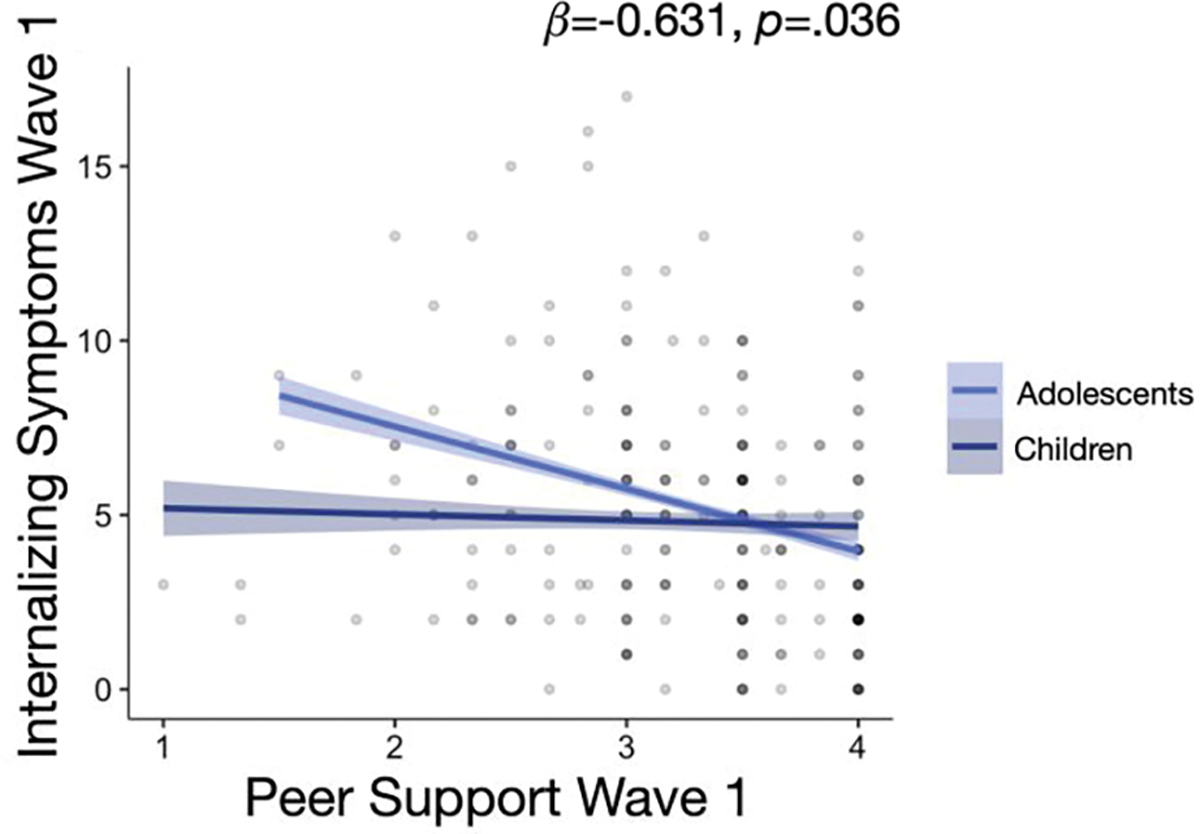

Finally, we examined perceived support from peers during the initial stay-at-home order period. Lower levels of peer support were concurrently and prospectively associated with greater internalizing symptoms (β=−0.234, p<.001 and β=−0.195, p=.007, respectively; Figure 2). Peer support was not associated with externalizing symptoms at either time point (ps>.358). Age moderated the association of peer support with concurrent internalizing symptoms (β=−0.631, p=.036), such that greater peer support was associated with fewer symptoms for adolescents (b=−1.979, p<.001), but not in children (b=−0.675, p=.122) (Figure 3). No other age interactions were found (ps>.104). Secondary analyses examining these associations with parental support during the pandemic can be found in Table S3.

Figure 3.

Age moderated the relationship between peer support and concurrent internalizing symptoms, such that the relationship between peer support and internalizing symptoms was stronger for adolescents than children. Shaded region indicates SE.

Social factors and stress-related psychopathology

We then examined whether social experiences interacted with pandemic-related stressors in ways that predicted psychopathology during the early stages of the pandemic, controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms. Experiencing more pandemic-related stressors was concurrently and prospectively associated with heightened internalizing (β=0.289, p<.001; β=0.186, p=.013, respectively) and externalizing (β=0.259, p<.001; β=0.271, p<.001, respectively) symptoms. The association between pandemic-related stressors and concurrent internalizing symptoms varied by age (β=0.202, p=.040), where the association was stronger for adolescents (b=0.877, p<.001) relative to children (b=0.391, p=.023).

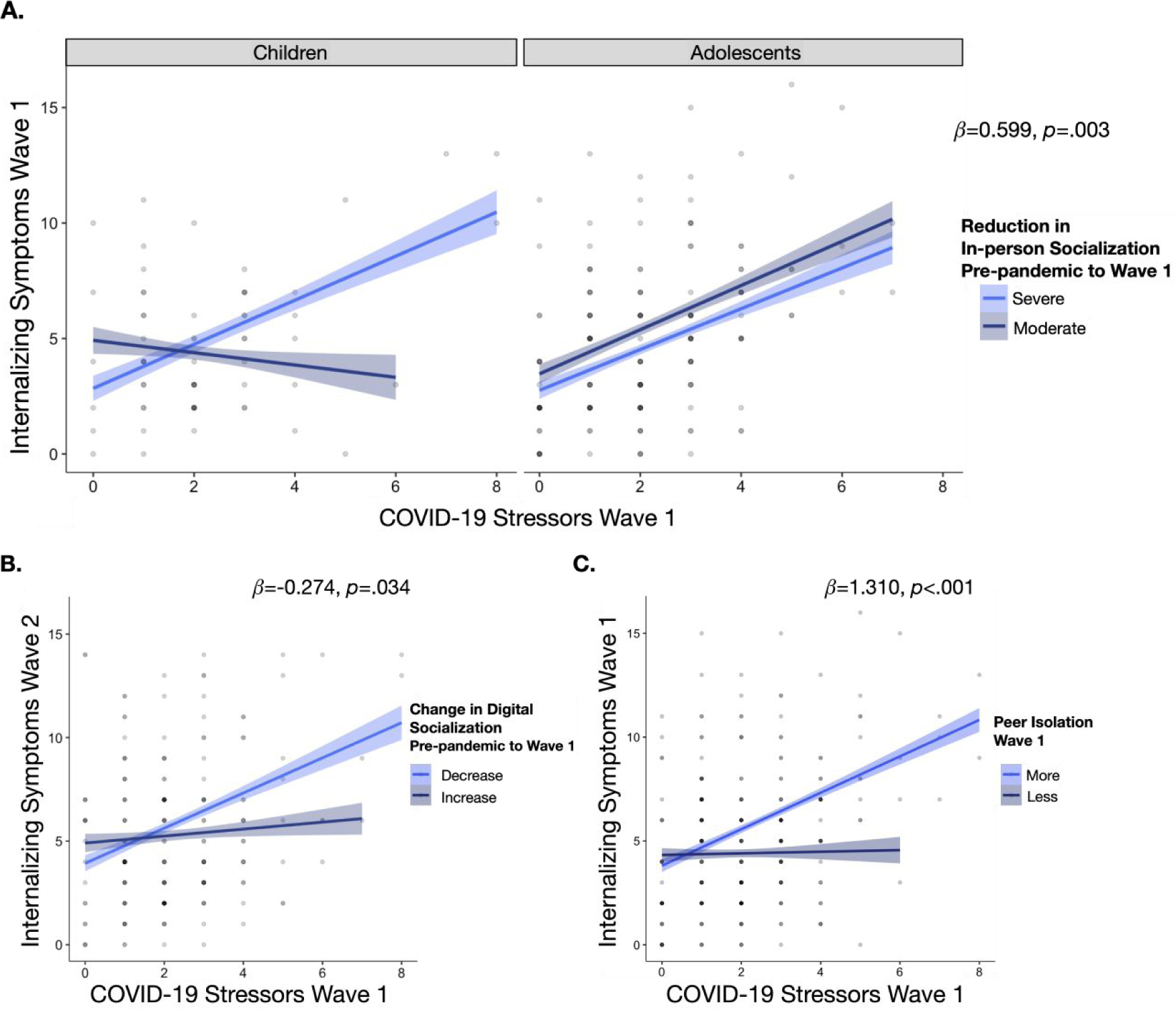

We observed a three-way-interaction between age, changes in in-person socialization from pre-pandemic levels, and pandemic-related stressors in predicting concurrent internalizing symptoms (β=0.599, p=.003). Specifically, the association of pandemic-related stressors with internalizing symptoms was positive only for children with greater reductions in in-person socialization (b=1.019, p<.001), and not children with small to moderate reductions in in-person socialization (b=−0.684, p=.070). For adolescents, a strong association between pandemic-related stressors and internalizing psychopathology existed, regardless of socialization (b=0.751–1.130, p=.004-<.001).

Changes in digital socialization from pre-pandemic levels moderated the prospective link between pandemic-related stressors and internalizing symptoms six months later, after the initial stay-at-home orders had been lifted (β=−0.274, p=.034). Youth who decreased digital socialization from pre-pandemic levels showed stronger associations between pandemic-related stress and internalizing symptoms six months later (b=0.795, p<.001), whereas those who increased digital socialization showed no relationship between pandemic-related stress and internalizing symptoms six months later (b=0.144, p=.512). No other relationships with digital socialization or age interactions were found (ps>.111).

Social isolation during the initial stay-at-home-orders moderated the association between exposure to pandemic-related stressors with concurrent internalizing (β=1.310, p<.001) and externalizing symptoms (β=0.819, p=.016) (Figure 4), but not six months later (ps>.241). The association of pandemic-related stressors with concurrent internalizing and externalizing symptoms was positive for youth with high levels of social isolation (b=0.873, p<.001 and b=0.602, p<.001, respectively), but absent in those with low levels of isolation (b=−0.126, p=.566 and b=−0.024, p=.913, respectively). Peer support did not interact with pandemic-related stressors to predict psychopathology (ps>.069). There were no interactions with age (ps>.301).

Figure 4.

Social experiences moderated the association between pandemic-related stressors and psychopathology. A. Children with more severe reductions of in-person socialization during initial stay-at-home orders showed a positive association between pandemic-related stressors with internalizing symptoms, but this pattern was absent in children with only moderate reduction of in-person socialization. Adolescents showed this strong relationship, regardless of the extent of change in in-person socialization. B. Youth who decreased digital socialization from pre-pandemic levels showed a positive relationship between pandemic-related stressors and internalizing and externalizing symptoms six months later, while this relationship was absent in those who reported increased digital socialization. C. Youth who reported greater isolation showed a positive relationship between pandemic-related stressors and concurrent internalizing and externalizing symptoms, while this relationship was absent in those who reported low peer isolation. Shaded region indicates SE.

Discussion

Understanding how youth are impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic is critical to help families identify strategies that promote wellbeing during similar societal-level events. Here, we leveraged longitudinal assessments prior to the pandemic, during the initial stay-at-home order period, and six months later after the initial stay-at-home orders were lifted to examine how the pandemic has influenced the social lives of children and adolescents, and whether changes in social experiences were related to internalizing and externalizing problems. Unsurprisingly, marked declines in in-person socialization occurred during the early stages of the pandemic. Youth who reported greater social isolation and less support from peers experienced increased internalizing and externalizing symptoms during the pandemic. Critically, youth who reported less social isolation, maintained some in-person socialization, and increased digital socialization during the pandemic were more protected from developing psychopathology following exposure to pandemic-related stressors.

As expected, we observed a marked decline in in-person socialization during the initial stay-at-home order period of the pandemic for both children and adolescents. However, contrary to our expectations, we observed no change in digital socialization. While these findings are in line with recent work (Asscheman et al., 2021) and appear to show that overall youth did not engage in more digital socialization to compensate for less in-person socialization, it is important to examine individual differences in these behaviors. Our data show that greater reductions in-person socialization during the pandemic were associated with greater feelings of isolation (Table S6), suggesting a possible mechanism underlying increased vulnerability to stress-related psychopathology (Barbieri & Mercado, 2022). Consistent with this possibility, youth who reported greater feelings of isolation from peers and lower perceived support from peers also exhibited increased internalizing symptoms relative to pre-pandemic levels. These links remained six months later after the stay-at-home order period. Together, these findings are aligned with prior work showing that children and adolescents who experience social disconnection, isolation, and lower quality peer relationships are at increased risk for psychopathology (Erzen & Çikrikci, 2018; La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Spithoven et al., 2017; Troop-Gordon et al., 2019; Witvliet et al., 2010) and emerging work finding similar links during the pandemic (Asscheman et al., 2021; Campione-Barr et al., 2021; Ellis et al., 2020; Espinoza & Hernandez, 2022; Green et al., 2021; Hutchinson et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2022; Magson et al., 2021; D. Wang et al., 2022). Of note, the negative association between peer support and internalizing symptoms was stronger for adolescents relative to children. This suggests that peer support may be particularly important for adolescents during periods of stress (Alto et al., 2018; Gaertner et al., 2010; Harmelen et al., 2017; Havewala et al., 2019; Mackin et al., 2017; Trickey et al., 2012), especially considering the heightened importance of peer relationships during adolescence (Brown, 1990).

We also examined potential protective social factors by testing their interaction with pandemic-related stressors in predicting psychopathology. Indeed, the strong association of pandemic-related stressors with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology was absent in youth who reported lower levels of social isolation from peers. These findings align with extensive evidence demonstrating that youth who experience greater social belonging, peer support, and high friendship quality protected from developing psychopathology following stress exposure, even relatively severe experiences like trauma and child maltreatment (Alto et al., 2018; Gaertner et al., 2010; Harmelen et al., 2017; Mackin et al., 2017; Pine & Cohen, 2002; Trickey et al., 2012).

Findings also showed that children who had less severe reductions of in-person socialization during the initial stay-at-home order period were at lower risk for increased internalizing symptoms following exposure to pandemic-related stressors. In contrast, the relationship between pandemic-related stressors and internalizing psychopathology remained strong in adolescents regardless of the extent to which levels of in-person socialization decreased during the pandemic. These age-related differences may be explained by adolescents’ heightened sensitivity to stress, wherein the association between stress exposure and psychopathology is more tightly coupled during adolescence than other developmental periods (Espejo et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2003, 2004; Larson & Ham, 1993; Monroe et al., 1999). Indeed, recent work has shown that adolescents were more negatively impacted by pandemic-related stress than adults, resulting in greater depression symptoms (Green et al., 2021). This possibility is supported by our data, where the association between pandemic-related stressors and internalizing symptoms was stronger for adolescents than children.

Finally, children and adolescents who increased digital socialization were less likely to develop pandemic stress-related internalizing problems over time than those who decreased digital socialization. This prospective relationship may be key, as previous work has found that increased digital socialization with peers was concurrently associated with greater depression (Ellis et al., 2020), though this study did not control for pre-pandemic symptoms. Further, findings have been mixed as to whether social media use during the pandemic was associated with internalizing symptoms (Cauberghe et al., 2021; Ellis et al., 2020; Magson et al., 2021). Future work should disentangle the components of digital socialization that contribute to these associations, as the quality rather than quantity of socialization may be more predictive of mental health outcomes (Asscheman et al., 2021; Hamilton et al., 2022; Swerdlow et al., 2021). Ultimately, findings support the notion that augmented digital socialization may mitigate the negative effects of social distancing during the pandemic (Espinoza & Hernandez, 2022; Orben et al., 2020), given prior work showing that digital socialization can enhance relational bonds, perceived social support, and reduce loneliness (George et al., 2018; Padilla-Walker et al., 2012). Thus, we provide evidence that maintenance of social connections using digital technology during the pandemic promotes resilience among children and adolescents. These findings highlight the importance of examining these questions in a longitudinal fashion, as recent work did not find such protective effects of digital socialization against concurrent depression related to pandemic stress exposure (Ellis et al., 2020).

Together, the current study identifies several social factors that promote wellbeing and resilience in children and adolescents during the early stages of the pandemic. A primary strength of this study was the use of a longitudinal sample that allowed us to track psychopathology across three strategic time points (i.e., pre-pandemic, during the initial stay-at-home orders, and after the initial stay-at-home orders were lifted six months later), and examine both concurrent and prospective effects of social factors and stress on psychopathology, while controlling for pre-pandemic psychopathology. However, findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, we relied on self-report measures, which are subject to bias and inaccuracy. Future work examining socialization should leverage mobile phone data for objective accounts of social interaction. Second, findings are correlational and limit our ability to make causal inferences, despite the longitudinal nature of this study. Third, we used a different measure of psychopathology prior to the pandemic (CBCL/YSR) than after the onset of the pandemic (SDQ). While it would have been ideal to have the same measure at all time points, the CBCL/YSR is much longer than the SDQ and we were focused on minimizing participant burden during a period of time when families were facing numerous stressors and loss of access to typical childcare options. Thus, we chose to use a shorter questionnaire that is strongly correlated with the CBCL/YSR (R. Goodman, 2001; R. Goodman & Scott, 1999; Klasen et al., 2000; Van Roy et al., 2008). We also note that recent longitudinal studies and systematic reviews examining the impact of the pandemic on adolescent mental health (Barendse et al., 2022; Fegert et al., 2020; Hawes et al., 2021; Racine et al., 2020) identify a 2–3 fold increase in internalizing symptoms from before to during the pandemic. This magnitude of symptom increase is consistent with the increase in clinical symptoms seen in our sample, reducing concern over the use of different measures. Fourth, to examine the relevant risk and resilience factors that motivated our hypotheses, we conducted a number of regression models that examined direct effects, moderation effects, and age effects. This may increase risk for Type 1 errors. To mitigate this concern, we conducted sensitivity analyses correcting for multiple comparisons when testing the same association for both internalizing and externalizing symptoms using the false discovery rate correction method from the function p.adjust of the package stats in R (R Core Team, 2020). All findings held, except for two which became non-significant, though patterns remained consistent (Table S7). Fifth, we combined data from two separate samples of children (aged 7–10 and 13–15 at Wave 1). Both samples were recruited from the general community using similar methods, and we had identical measures of pre-pandemic psychopathology on both samples. Moreover, the samples did not differ in demographics, SES, or exposure to pandemic-related stressors. However, using two samples with a gap in age limited our ability to understand age effects across the entire spectrum of childhood and adolescence. Sixth, we demonstrate the predictive validity of the pandemic-related stress measure via moderate associations with psychopathology at both waves as well as a measure of perceived stress. However, this cumulative risk approach is limited in that it weights stressors equally that could have variable impacts (see Table S2 for domain-specific associations with psychopathology). Seventh, we acknowledge that the reliability for our measure of social isolation is relatively low (alpha=0.57; Table S4). Eighth, we only explicitly assessed for change in socialization behaviors, thereby making it impossible to determine how other social factors (social isolation and support) changed over time. Finally, the current study was conducted in the Seattle area, which was hit particularly hard early in the pandemic and was accompanied by strict stay-at-home orders; however, across the country, there has been substantial variability in city and state-level ordinances of social distancing, thereby limiting generalizability of findings to other geographic areas with less severe stay-at-home orders.

Conclusion

We investigated social factors that might promote wellbeing in children and adolescents during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Critically, emerging research suggests that the impact of the pandemic demonstrates a remarkable level of stability (von Soest et al., 2022), suggesting that current findings are relevant to later stages of the pandemic. In all, results demonstrate that mitigating feelings of social isolation from peers, experiencing greater support from peers, continuing some degree of in-person socialization, and enhancing digital socialization are all key to youth resilience and wellbeing during the early stages of the pandemic. These findings have implications for current and future societal-level crises that are accompanied by social isolation. In particular, youth should engage in some level of in-person social interaction, while following safety protocols to the greatest extent possible. For example, during the early stages of the current pandemic, community centers facilitated outdoor activities that involve safely distanced, yet social and physical engagement (e.g., dance, non-contact sports, etc.). Additionally, youth would benefit from fostering supportive and connected relationships with peers, including through digital means (e.g., phone and video calls, text messages, messaging apps). Importantly, it is critical that digital socializing be active and engaging, given previous work demonstrating high levels of passive screen time may negatively impact wellbeing (Burke & Kraut, 2016; Clark et al., 2018; Rosen et al., 2021). Given their heightened sensitivity to stress and loss of peer support, adolescents, in particular, should aim to maintain regular social interactions with their peers to increase social connection. Ultimately, strategies that foster greater social support and connection among youth during a time of social deprivation, such as during the early stages of the current pandemic, are likely to be beneficial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bezos Family Foundation (to ANM) for collection of data. This work was also supported by the National Institute of Health (R01 MH106482 to KAM; K99 HD099203 to MLR; K99 MH126163 to AMR). The authors would also like to acknowledge Reshma Sreekala and Malila Freeman for help with data collection and Frances Li for help with compiling surveys. Funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest, competing interests, or disclosures.

References:

- Achenbach TM (1991). Integrative guide for the CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF profiles. In Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, & Rescorla LA (2003). DSM-oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing scales from the same item pools. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg M, Dobbelaar S, Boer OD, & Crone EA (2021). Perceived stress as mediator for longitudinal effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on wellbeing of parents and children. Scientific Reports, 11(1), Article 1. 10.1038/s41598-021-81720-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alto M, Handley E, Rogosch F, Cicchetti D, & Toth S (2018). Maternal relationship quality and peer social acceptance as mediators between child maltreatment and adolescent depressive symptoms: Gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 63, 19–28. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asscheman JS, Zanolie K, Bexkens A, & Bos MGN (2021). Mood Variability Among Early Adolescents in Times of Social Constraints: A Daily Diary Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 3635. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri M, & Mercado E (2022). The impact of stay-at-home regulations on adolescents’ feelings of loneliness and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 94(7), 1022–1034. 10.1002/jad.12084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barendse MEA, Flannery J, Cavanagh C, Aristizabal M, Becker SP, Berger E, Breaux R, Campione-Barr N, Church JA, Crone EA, Dahl RE, Dennis-Tiwary TA, Dvorsky MR, Dziura SL, van de Groep S, Ho TC, Killoren SE, Langberg JM, Larguinho TL, … Pfeifer JH (2022). Longitudinal Change in Adolescent Depression and Anxiety Symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Research on Adolescence, n/a(n/a). 10.1111/jora.12781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, & Maechler M (2018). lme4: Mixed-effects models in R using S4 classes and methods with RcppEigen [HTML]. lme4. https://github.com/lme4/lme4 [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg SJ, Bialostosky K, Hamilton WL, & Briefel RR (1999). The effectiveness of a short form of the Household Food Security Scale. American Journal of Public Health, 89(8), 1231–1234. 10.2105/AJPH.89.8.1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB (1990). Peer groups and peer cultures. In Feldman SS & Elliott GR (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 171–196). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke M, & Kraut RE (2016). The Relationship Between Facebook Use and Well-Being Depends on Communication Type and Tie Strength. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(4), 265–281. 10.1111/jcc4.12162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campione-Barr N, Rote W, Killoren SE, & Rose AJ (2021). Adolescent Adjustment During COVID-19: The Role of Close Relationships and COVID-19-related Stress. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 608–622. 10.1111/jora.12647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauberghe V, Wesenbeeck IV, Jans SD, Hudders L, & Ponnet K (2021). How Adolescents Use Social Media to Cope with Feelings of Loneliness and Anxiety During COVID-19 Lockdown. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 10.1089/cyber.2020.0478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahal R, Kirshenbaum JS, Miller JG, Ho TC, & Gotlib IH (2020). Higher executive control network coherence buffers against puberty-related increases in internalizing symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JL, Algoe SB, & Green MC (2018). Social Network Sites and Well-Being: The Role of Social Connection. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(1), 32–37. 10.1177/0963721417730833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohodes EM, McCauley S, & Gee DG (2021). Parental Buffering of Stress in the Time of COVID-19: Family-Level Factors May Moderate the Association Between Pandemic-Related Stress and Youth Symptomatology. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(7), 935–948. 10.1007/s10802-020-00732-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne SM, Stockdale L, & Summers K (2019). Problematic cell phone use, depression, anxiety, and self-regulation: Evidence from a three year longitudinal study from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 78–84. 10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, & Dahl RE (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(9), 636–650. 10.1038/nrn3313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Figueiredo CS, Sandre PC, Portugal LCL, Mázala-de-Oliveira T, da Silva Chagas L, Raony Í, Ferreira ES, Giestal-de-Araujo E, dos Santos AA, & Bomfim PO-S (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 106, 110171. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey WC, & Blumberg SJ (2004). Revisiting the Factor Structure of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: United States, 2001. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(9), 1159–1167. 10.1097/01.chi.0000132808.36708.a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WE, Dumas TM, & Forbes LM (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 52(3), 177–187. 10.1037/cbs0000215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erzen E, & Çikrikci Ö (2018). The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(5), 427–435. 10.1177/0020764018776349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo EP, Hammen CL, Connolly NP, Brennan PA, Najman JM, & Bor W (2007). Stress Sensitization and Adolescent Depressive Severity as a Function of Childhood Adversity: A Link to Anxiety Disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(2), 287–299. 10.1007/s10802-006-9090-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza G, & Hernandez HL (2022). Adolescent loneliness, stress and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: The protective role of friends. Infant and Child Development, 31(3), e2305. 10.1002/icd.2305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW (2006). Child Development and the Physical Environment. Annual Review of Psychology, 57(1), 423–451. 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Li D, & Whipple SS (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1342–1396. 10.1037/a0031808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, & Clemens V (2020). Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1), 20. 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner AE, Fite PJ, & Colder CR (2010). Parenting and Friendship Quality as Predictors of Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms in Early Adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(1), 101–108. 10.1007/s10826-009-9289-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, & Vlahov D (2002). Psychological Sequelae of the September 11 Terrorist Attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(13), 982–987. 10.1056/NEJMsa013404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, Jones RT, King DW, King LA, McNally RJ, Ursano RJ, Petukhova M, & Kessler RC (2007). Exposure to Hurricane-Related Stressors and Mental Illness After Hurricane Katrina. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(12), 1427–1434. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassman-Pines A, Ananat EO, & Fitz-Henley J (2020). COVID-19 and Parent-Child Psychological Well-being. Pediatrics, 146(4). 10.1542/peds.2020-007294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MJ, Russell MA, Piontak JR, & Odgers CL (2018). Concurrent and Subsequent Associations Between Daily Digital Technology Use and High-Risk Adolescents’ Mental Health Symptoms. Child Development, 89(1), 78–88. 10.1111/cdev.12819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Lamping DL, & Ploubidis GB (2010). When to Use Broader Internalising and Externalising Subscales Instead of the Hypothesised Five Subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British Parents, Teachers and Children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1179–1191. 10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, & Scott S (1999). Comparing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist: Is Small Beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(1), 17–24. 10.1023/A:1022658222914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, & Halpert JA (2003). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 447–466. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, & Gipson PY (2004). Stressors and Child and Adolescent Psychopathology: Measurement Issues and Prospective Effects. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 33(2), 412–425. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KH, van de Groep S, Sweijen SW, Becht AI, Buijzen M, de Leeuw RNH, Remmerswaal D, van der Zanden R, Engels RCME, & Crone EA (2021). Mood and emotional reactivity of adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Short-term and long-term effects and the impact of social and socioeconomic stressors. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 11563. 10.1038/s41598-021-90851-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Prinstein MJ, Clark LA, Rottenberg J, Abramowitz JS, Albano AM, Aldao A, Borelli JL, Chung T, Davila J, Forbes EE, Gee DG, Hall GCN, Hallion LS, Hinshaw SP, Hofmann SG, Hollon SD, Joormann J, Kazdin AE, … Weinstock LM (2020). Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. American Psychologist. 10.1037/amp0000707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Nesi J, & Choukas-Bradley S (2022). Reexamining Social Media and Socioemotional Well-Being Among Adolescents Through the Lens of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theoretical Review and Directions for Future Research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(3), 662–679. 10.1177/17456916211014189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmelen A.-L. van, Kievit RA, Ioannidis K, Neufeld S, Jones PB, Bullmore E, Dolan R, Consortium, T. N., Fonagy P, & Goodyer I (2017). Adolescent friendships predict later resilient functioning across psychosocial domains in a healthy community cohort. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2312–2322. 10.1017/S0033291717000836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1985). The Social Support Scale for Children and Adolescents: Manual and Questionnaire. University of Denver. https://portfolio.du.edu/SusanHarter/page/44343 [Google Scholar]

- Havewala M, Felton JW, & Lejuez CW (2019). Friendship quality moderates the relation between maternal anxiety and trajectories of adolescent internalizing symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 41(3), 495–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Klein DN, Hajcak G, & Nelson BD (2021). Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine, 1–9. 10.1017/S0033291720005358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Stahl M, & Petersen AC (1996). The protective role of coping and social resources for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25(6), 733–753. 10.1007/BF01537451 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holman EA, Thompson RR, Garfin DR, & Silver RC (2020). The unfolding COVID-19 pandemic: A probability-based, nationally representative study of mental health in the United States. Science Advances, 6(42), eabd5390. 10.1126/sciadv.abd5390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton S, Kyron M, Hunter SC, Lawrence D, Hattie J, Carroll A, & Zadow C (2022). Adolescents’ longitudinal trajectories of mental health and loneliness: The impact of COVID-19 school closures. Journal of Adolescence, 94(2), 191–205. 10.1002/jad.12017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson EA, Sequeira SL, Silk JS, Jones NP, Oppenheimer C, Scott L, & Ladouceur CD (2021). Peer Connectedness and Pre-Existing Social Reward Processing Predicts U.S. Adolescent Girls’ Suicidal Ideation During COVID-19. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 703–716. 10.1111/jora.12652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SE, Ethier KA, Hertz M, DeGue S, Le VD, Thornton J, Lim C, Dittus PJ, & Geda S (2022). Mental Health, Suicidality, and Connectedness Among High School Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic—Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Supplements, 71(3), 16–21. 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, He J, Koretz D, McLaughlin KA, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Merikangas KR (2012). Prevalence, Persistence, and Sociodemographic Correlates of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(4), 372–380. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasen H, Woerner W, Wolke D, Meyer R, Overmeyer S, Kaschnitz W, Rothenberger A, & Goodman R (2000). Comparing the German Versions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-Deu) and the Child Behavior Checklist. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 9(4), 271–276. 10.1007/s007870070030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles ML, Haycock N, & Shaikh I (2015). Does Facebook Magnify or Mitigate Threats to Belonging? Social Psychology, 46(6), 313–324. 10.1027/1864-9335/a000246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, & Harrison HM (2005). Adolescent Peer Relations, Friendships, and Romantic Relationships: Do They Predict Social Anxiety and Depression? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 49–61. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, & Lopez N (1998). Social Anxiety Among Adolescents: Linkages with Peer Relations and Friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26(2), 83–94. 10.1023/A:1022684520514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, & Troop-Gordon W (2003). The Role of Chronic Peer Difficulties in the Development of Children’s Psychological Adjustment Problems. Child Development, 74(5), 1344–1367. 10.1111/1467-8624.00611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CB, McHale SM, & Crouter AC (2014). Time With Peers From Middle Childhood to Late Adolescence: Developmental Course and Adjustment Correlates. Child Development, 85(4), 1677–1693. 10.1111/cdev.12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landoll RR, La Greca AM, Lai BS, Chan SF, & Herge WM (2015). Cyber victimization by peers: Prospective associations with adolescent social anxiety and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 77–86. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R (2001). How U.S. Children and Adolescents Spend Time: What It Does (and Doesn’t) Tell Us About Their Development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(5), 160–164. 10.1111/1467-8721.00139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, & Ham M (1993). Stress and “storm and stress” in early adolescence: The relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 130–140. 10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Moran L, Zalewski M, Ruberry E, Kiff C, & Thompson S (2015). Relations of Growth in Effortful Control to Family Income, Cumulative Risk, and Adjustment in Preschool-age Children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(4), 705–720. 10.1007/s10802-014-9941-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Ling R, Campbell S, & Purcell K (2010). Teens and Mobile Phones: Text Messaging Explodes as Teens Embrace It as the Centerpiece of Their Communication Strategies with Friends. Pew Internet & American Life Project. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED525059 [Google Scholar]

- Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, Linney C, McManus MN, Borwick C, & Crawley E (2020). Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239.e3. 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackin DM, Perlman G, Davila J, Kotov R, & Klein DN (2017). Social support buffers the effect of interpersonal life stress on suicidal ideation and self-injury during adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 1149–1161. 10.1017/S0033291716003275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, & Fardouly J (2021). Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay AR, May T, Dawes J, Fancourt D, & Burton A (2022). ‘You’re just there, alone in your room with your thoughts’: A qualitative study about the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among young people living in the UK. BMJ Open, 12(2), e053676. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA (2016). Future Directions in Childhood Adversity and Youth Psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(3), 361–382. 10.1080/15374416.2015.1110823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlin KA, Fairbank JA, Gruber MJ, Jones RT, Lakoma MD, Pfefferbaum B, Sampson NA, & Kessler RC (2009). Serious Emotional Disturbance Among Youths Exposed to Hurricane Katrina 2 Years Postdisaster. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(11), 1069–1078. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b76697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2012). Childhood Adversities and First Onset of Psychiatric Disorders in a National Sample of US Adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(11), 1151–1160. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, & Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirisola A, & Seta L (2016). pequod: Moderated Regression Package (0.0–5). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pequod/pequod.pdf

- Monroe M, Rohde P, Seeley JR, & Lewinsohn PM (1999). Life Events and Depression in Adolescence: Relationship Loss as a Prospective Risk Factor for First Onset of Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(4), 606–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock KK (2013). Texting while stressed: Implications for students’ burnout, sleep, and well-being. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(4), 207–221. 10.1037/ppm0000012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan SA, Flynn C, & Garber J (2003). Prospective relations between rejection and depression in young adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(4), 745–755. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orben A, Tomova L, & Blakemore S-J (2020). The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(8), 634–640. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30186-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker LM, Coyne SM, & Fraser AM (2012). Getting a High-Speed Family Connection: Associations Between Family Media Use and Family Connection. Family Relations, 61(3), 426–440. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00710.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, Lovell K, Halvorson A, Loch S, Letterie M, & Davis MM (2020). Well-being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Pediatrics, 146(4). 10.1542/peds.2020-016824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B, & North CS (2020). Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), 510–512. 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B, Seale TW, Mcdonald NB, Brandt EN, Rainwater SM, Maynard BT, Meierhoefer B, & Miller PD (2000). Posttraumatic Stress Two Years after the Oklahoma City Bombing in Youths Geographically Distant from the Explosion. Psychiatry, 63(4), 358–370. 10.1080/00332747.2000.11024929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, Kontopantelis E, Webb R, Wessely S, McManus S, & Abel KM (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, & Cohen JA (2002). Trauma in children and adolescents: Risk and treatment of psychiatric sequelae. Biological Psychiatry, 51(7), 519–531. 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01352-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt B, Kadosh KC, & Lau JYF (2013). The Role of Peer Rejection in Adolescent Depression. Depression and Anxiety, 30(9), 809–821. 10.1002/da.22120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, & Aikins JW (2004). Cognitive Moderators of the Longitudinal Association Between Peer Rejection and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(2), 147–158. 10.1023/B:JACP.0000019767.55592.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Zhou S-J, Guo Z-C, Zhang L-G, Min H-J, Li X-M, & Chen J-X (2020). The Effect of Social Support on Mental Health in Chinese Adolescents During the Outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 514–518. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (3.5.2). R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Racine N, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Korczak DJ, McArthur B, & Madigan S (2020). Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: A rapid review. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113307. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmayne M, Smith E, & Abramson MJ (2013). The relationship between adolescents’ well-being and their wireless phone use: A cross-sectional study. Environmental Health, 12(1), 90. 10.1186/1476-069X-12-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodman AM, Powers KE, & Somerville LH (2017). Development of self-protective biases in response to social evaluative feedback. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(50), 13158–13163. 10.1073/pnas.1712398114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ML, Hagen MP, Lurie LA, Miles ZE, Sheridan MA, Meltzoff AN, & McLaughlin KA (2019). Cognitive Stimulation as a Mechanism Linking Socioeconomic Status With Executive Function: A Longitudinal Investigation. Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.13315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ML, Meltzoff AN, Sheridan MA, & McLaughlin KA (2019). Distinct aspects of the early environment contribute to associative memory, cued attention, and memory-guided attention: Implications for academic achievement. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ML, Rodman AM, Kasparek SW, Mayes M, Freeman MM, Lengua LJ, Meltzoff AN, & McLaughlin KA (2021). Promoting youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. PLOS ONE, 16(8), e0255294. 10.1371/journal.pone.0255294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roser K, Schoeni A, Foerster M, & Röösli M (2016). Problematic mobile phone use of Swiss adolescents: Is it linked with mental health or behaviour? International Journal of Public Health, 61(3), 307–315. 10.1007/s00038-015-0751-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]