Abstract

Coptis plants (Ranunculaceae) contain high levels of isoquinoline alkaloids and have a long history of medicinal use. Coptis species are of great value in pharmaceutical industries and scientific research. Mitochondria are considered as one of the central units for receiving stress signals and arranging immediate responses. Comprehensive characterizations of plant mitogenomes are imperative for revealing the relationship between mitochondria, elucidating biological functions of mitochondria and understanding the environmental adaptation mechanisms of plants. Here, the mitochondrial genomes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis were assembled through the Nanopore and Illumina sequencing platform for the first time. The genome organization, gene number, RNA editing sites, repeat sequences, gene migration from chloroplast to mitochondria were compared. The mitogenomes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis have six, two, two circular-mapping molecules with the total length of 1,425,403 bp, 1,520,338 bp and 1,152,812 bp, respectively. The complete mitogenomes harbors 68-86 predicted functional genes including 39-51 PCGs, 26-35 tRNAs and 2-5 rRNAs. C. deltoidea mitogenome host the most abundant repeat sequences, while C. chinensis mitogenome has the largest number of transferred fragments from its chloroplasts. The large repeat sequences and foreign sequences in the mitochondrial genomes of Coptis species were related to substantial rearrangements, changes in relative position of genes and multiple copy genes. Further comparative analysis illustrated that the PCGs under selected pressure in mitochondrial genomes of the three Coptis species mainly belong to the mitochondrial complex I (NADH dehydrogenase). Heat stress adversely affected the mitochondrial complex I and V, antioxidant enzyme system, ROS accumulation and ATP production of the three Coptis species. The activation of antioxidant enzymes, increase of T-AOC and maintenance of low ROS accumulation in C. chinensis under heat stress were suggested as the factors for its thermal acclimation and normal growth at lower altitudes. This study provides comprehensive information on the Coptis mitogenomes and is of great importance to elucidate the mitochondrial functions, understand the different thermal acclimation mechanisms of Coptis plants, and breed heat-tolerant varieties.

Keywords: Coptis species, mitochondrial genome, repeat sequence, genome size variation, thermal acclimation

1. Introduction

The constant increase in the accumulation of greenhouse gases has increasingly led to rise in average global temperature (Rivero et al., 2022). Temperature changes are closely related to plant growth and development. Medicinal plants exposed to high temperatures have impaired growth and medicine quality (Heydari et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2022). Global warming has also reduced the area of suitable habitats for medicinal plants that grow at higher altitudes (e.g. Panax notoginseng) (Zhan et al., 2022). Therefore, to maintain the sustainable use of medicinal resources in the face of climate change, it is important to understand the mechanisms of differential adaptation to high temperatures in medicinal plants and to obtain genetic resources for heat tolerance.

As pharmaceutically and economically important plants, Coptis genus (Ranunculaceae) mainly distributes in eastern Asia and North America (Xiang et al., 2018). Five Coptis species (Coptis chinensis Franch., C. deltoidea C. Y. Cheng et Hsiao, C. teeta Wall., C. omeiensis (Chen) C. Y. Cheng, and C. quinquesecta W. T. Wang) are distributed in southern and southwestern China. The dried rhizomes of Coptis plants named Coptidis Rhizoma with definitive pharmacological roles in anti-inflammatory, anti-bacteria, anti-diabetic and neuroprotection have a long history of medicinal use in China (Li et al., 2019; Ran et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Coptidis Rhizoma is rich in berberine (Qi et al., 2018) which shows considerable potential as resource with various pharmacological activities for pharmaceutical and healthcare market (Song et al., 2020). C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. teeta are the sources of Coptidis Rhizoma stipulated in Chinese Pharmacopoeia, while the other Coptis species have been used as alternative folk herbs. The three Pharmacopeia-recorded Coptis species have been cultivated on different scales for several hundred years, while C. omeiensis has not been artificially cultivated (Mukherjee and Chakraborty, 2019). In China, the wild populations of these species are restricted distribution and almost endangered. The three closely related Coptis species exhibit significant differences in the altitudinal distribution ranges (http://www.iplant.cn/frps). The high temperatures in summer are one of the most important factors affecting the survival and herb production of Coptis plants and global warming will reduce the suitable growth areas of Coptis species (Li et al., 2020). C. chinensis with stronger environmental adaptability has a wider distribution range and become a widely cultivated species nowadays (He et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the molecular and physiological mechanisms of the differences in the thermal adaptation of Coptis species are poorly understood and the breeding of heat-tolerant cultivars has not been carried out. Limitations of the growing environment and the lack of improved varieties have limited the cultivation and industrial development of Coptis species.

In plants, mitochondria are essential organelles and responsible for plant energy metabolism. Mitochondria are considered as one of the central units for receiving stress signals and arranging immediate responses (Rasmusson and Møller, 2011). To counteract the environment stress, plants require high energetic demand, and mitochondria produce energy through oxidative phosphorylation, which determines the efficiency of ATP production and the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Luo et al., 2013). Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is considered to be an important metabolic participant in plants under environmental stress, since the ATP synthesis capacity of the mitochondria and mitochondrial complex V activity greatly varies according to environmental stress, such as temperature and salt (Rurek, 2014; Zancani et al., 2020). In addition, mitochondria ROS generation is particularly important in signaling systems that integrate energy metabolism and stress responses in plants (Waszczak et al., 2018). The mitochondrial electron transport chain is responsible for the production of mitochondria ROS, which is thought to generate at the inner mitochondrial membrane and is associated particularly with Complex I. The rapid accumulation of ROS occurred in plants when they exposed to heat and drought (Medina et al., 2021), which can severely cause oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, and membrane lipids. A considerable amount of work has demonstrated that the ROS scavenging mechanisms play an important role in plant tolerance to high temperature stress.

Comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial genome is important to reveal the function of plant mitochondria (Cheng et al., 2021). Comparing to the counterparts of animals and fungi, land plant mitochondrial genomes exhibit some unique features, such as extreme diversity in size (Levings and Brown, 1989; Rodríguez-Moreno et al., 2011), complex genome structures (Ogihara et al., 2005; Guo et al., 2016), numerous repetitive sequences of various sizes and numbers (Cole et al., 2018; Dong et al., 2018), multiple RNA editing modifications (Kovar et al., 2018; Small et al., 2020), and frequent gene losses and foreign DNA migration during evolution (Cole et al., 2018; Dong et al., 2020). The sizes of plant mitogenome range from 66 kb (Viscum scurruloideum) (Skippington et al., 2015) to 11.3 Mb (Silene conica) (Sloan et al., 2012). Compared with nuclear and chloroplast genomes in plants, most angiosperm mitochondrial genomes have meager base substitution rates (Drouin et al., 2008). In contrast, the mitochondrial genomes of angiosperms evolve very rapidly in terms of structural rearrangements and gene transfer (Gualberto and Newton, 2017). The significant variation and different gene orders may occur within closely related species (Van de Paer et al., 2018), for example, within Cucumis (Cucurbitaceae) (Xia et al., 2022), Monsonia (Geraniaceae) (Cole et al., 2018), Mangifera (Anacardiaceae) (Niu et al., 2022). The high complexity of the plant mitochondrial genome makes it difficult to sequence and assemble. With the development of sequencing technology, the assembly and annotation of plant organelle genomes are promoted (Shearman et al., 2016). Approximately 437 plant mitochondrial genomes have been assembled and submitted to NCBI GenBank, that shed new light on the structure features and genetic composition of plant mitogenomes (Bi et al., 2022). In recent years, more researches have shown that comparative analysis of plant mitochondrial genomes can reflect the genetic information and evolutionary relationships between different species (Wang et al., 2021; Bi et al., 2022; Fan et al., 2022). Plant mitochondrial genome mainly encodes genes related to respiratory metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation, and these genes coordinate with the nucleus to ensure the function of plentiful proteins involved in the mitochondrial respiratory chain and the metabolic adaptations of plants (Osellame et al., 2012). Therefore, comprehensive characterizations of plant mitogenomes are imperative for revealing the relationship between mitochondria, elucidating biological functions of mitochondria and understanding the environmental adaptation mechanisms of plants.

In this study, the complete mitochondrial genomes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis were assembled and annotated. The gene content, codon usage, RNA editing sites, repeat sequences, genome rearrangement, gene transfer among chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of three Coptis species were characterized. Mitogenomic synteny analysis and comparative analysis of plant mitochondrial genomes are helpful to understand mitochondrial DNA differentiation and evolution in Coptis species. Furthermore, we carried out preliminary research on the heat stress-induced responses of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis. The expression level of several genes of mitochondrial complex I and V in were three Coptis species under 5 d heat stress were compared. The variations in accumulation of ROS, ATP content, activities of the antioxidant enzymes and activities of complex I and V were also evaluated. This study revealed the genetic information of three Coptis mitogenomes, and will provide important genetic resources for cultivation and utilization of these pharmaceutical species, contribute to better understanding of the thermal acclimation mechanisms of Coptis plants and provide a basis for the identification and cultivation of germplasm resources with a high degree of heat tolerance.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials

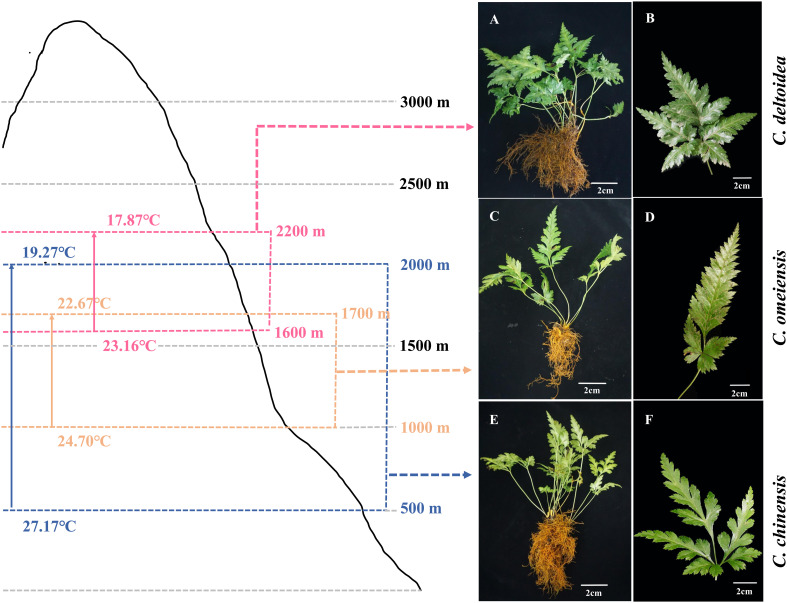

The C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis plants ( Figure 1 ) used in this study were grown in experiment field in Hongya, Sichuan, China (29°29′10.91″ N, 103°9′39.9″ E). Fresh leaves of the three Coptis plants were collected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at -80°C.

Figure 1.

Distribution range and the plant morphology of C. deltoidea (A, B), C. omeiensis (C, D) and C. chinensis (E, F). Pink, orange and blue range represent C. deltoidea, C. omeiensis, and C. chinensis, respectively. The average summer temperatures (June-August) at different altitudes of the Coptis distribution areas were marked with different colors.

2.2. DNA extraction, sequencing and assembly

High-quality genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves using a modified CTAB method (Porebski et al., 1997). DNA degradation and contamination were monitored on 1% agarose gels. After libraries construction using SQK-LSK109 (Nanopore Technologies), DNA sequencing was performed using Nanopore PromethION sequencing platform (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, US). NanoFilt and NanoPlot in Nanopack were used to filter and re-edit the raw data (De Coster et al., 2018). Meanwhile, the high-quality DNA from each sample was used to construct the libraries with average fragment length of 350 bp by the NexteraXT DNA Library Preparation Kit. Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to sequence the DNA samples and the raw sequencing data were edited using the NGS QC Tool Kit v2.3.3 (Patel and Jain, 2012). After trimming adapter sequences with Porechop (Wick et al., 2017a), Miniasm (Li, 2016) was applied to obtained a rough but computationally efficient assembly, which was then polished with Racon (Vaser et al., 2017). We selected contigs with homology to the Hepatica maxima (NCBI Sequence: MT568500.1) mitochondrial genome using Bandage (Wick et al., 2015). Retaining contigs with at least one ≥5 kb were aligned to the Hepatica maxima mitochondrion by BlastN. We then proceeded to align back the Nanopore reads to our draft assemblies of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis with minimap2 (Li, 2018). The aligned reads were de novo assembled with Unicycler (Wick et al., 2017b) and Flye (Kolmogorov et al., 2019). The final mitogenome sequences of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis were obtained by polishing with Pilon using Illumina Novaseq 6000 sequencing reads.

2.3. Mitogenomes annotation and sequence analysis

The mitogenomes of three Coptis species were annotated using the MITOFY webserver (http://dogma.ccbb.utexas.edu/mitofy/) (Alverson et al., 2010). The putative genes were manually checked and further adjusted according to relative species as the reference sequence. The tRNAs were annotated with the tRNA scan-SE software (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/) with default settings (Schattner et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2021). The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values and amino acid composition of PCGs were calculated by MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018). The circular maps of the Coptis mitochondrial genomes were visualized by using OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW v1.3.1) (Greiner et al., 2019).

The possible RNA editing sites in the PCGs of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis mitogenomes were predicted using the PREP-Mt Web-based program (http://prep.unl.edu/) with the cut-off value set as 0.2 (Mower, 2005). Genome synteny and rearrangements among the three Coptis mitogenomes were analyzed following Guo et al. (Guo et al., 2016), implementing the progressiveMauve algorithm in Mauve ver. 2.4.0 software (Darling et al., 2004). KaKs_Calculator v.2.0 was used to calculate the synonymous (Ks) and nonsynonymous (Ka) substitution rates for all PCGs in three Coptis mitogenomes (Zhang et al., 2006).

2.4. Identification of repeat sequences and chloroplast gene insertion in Coptis mitogenomes

The position and type of SSR sequences were analyzed with the MISA-web (https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/) (Beier et al., 2017). The minimum thresholds of repeats were set to 8, 4, 4, 3, 3, and 3 for mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotides, respectively. The online program REPuter (https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer) (Kurtz et al., 2001) was used to detect forward (F), reverse (R), palindromic (P), and complement (C) repeats with a minimum repeat size of 30 bp and the repeat identity was > 90%.

To identify plastid derived mitochondrial sequences of three Coptis species, the mitogenomes were searched against the chloroplast genomes of C. chinensis (NC_036485), C. deltoidea (MT576696), C. omeiensis (NC_054330) using the BLASTN tool with the default settings. The circular maps of mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes and gene transfer segments of three Coptis species were visualized by using Circos v0.69 software.

2.5. Phylogenetic analysis

The 9 conserved mitochondrial PCG genes (atp8, ccmB, ccmC, cob, cox1, cox3, nad3, nad4L and nad9) from the three Coptis mitogenomes and 26 plant mitochondrial genomes were aligned using the MAFFT 7.037 software (Katoh and Standley, 2013). A maximum likelihood (ML) tree was constructed in MEGA 7.0 using the GTR+G+I nucleotide substitution model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Oryza sativa, Zea mays and Ginkgo biloba were used as outgroups. To further reveal the phylogenetic relationships of the three Coptis species, a maximum likelihood (ML) tree of seven Ranunculaceae species (Pulsatilla chinensis, P. dahurica, Anemone maxima, Aconitum kusnezoffii, C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis) and three outgroups (Liriodendron tulipifera, Magnolia officinalis and M. biondii) was constructed based on 21 conserved mitochondrial PCGs (atp4, atp8, ccmB, ccmC, ccmFN, cob, cox1, cox3, mttB, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L nad5, nad7, nad9, rpl5, rpl16, rps13, sdh4) using MEGA 7.0. The mitochondrial genomes used to perform phylogenetic analysis were listed in Supplementary Table S1 .

2.6. High-temperature treatment and sampling

The C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis plants were grown in pots (10*15 cm) containing paddy soil. The plants were divided into two groups and placed in growth chamber set at 20°C (control) and 30°C (heat treatment group) for 5 days, with 6 individuals in each treatment group. The relative humidity of the growth chamber was set at 85% and the light intensity was set at 100 μmol m-2 s-1 with an 8 h/16 h light/dark cycle. To determine physiological and biochemical indices and RNA extraction, fully expanded leaves with three biological replicates from three Coptis species were collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately and then stored at -80°C.

2.7. Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from 50 mg of fresh leaves from control and heat treatment group by using HP plant RNA kit (Omega HP-Plant, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNAs were synthesized with total RNA (0.5 μg) from different treatments following the instruction of Master Premix for first-strand cDNA synthesis (FOREGENE, Chengdu, China). RT-qPCR were performed using 2 μL of a tenfold dilution of the cDNA in 20 μL solution system composed of 2× Real PCR Easy™ Mix-SYBR (FOREGENE, Chengdu, China). The 18S ribosomal RNA was used as an internal control gene for normalization (Ref) and the primers of each genes (nad1, nad2, nad5 and nad6) are listed in Supplementary Table S2 . The condition of PCR amplification reaction was conducted as follow: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 61°C for 30 s. The relative expression levels of target genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method.

2.8. Determination of superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, ATP content, activities of antioxidant enzymes, total antioxidant capacity and activities of mitochondrial complex I and V

The concentrations of superoxide anion and H2O2 were measured using detection assay kits (Solarbio, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The ATP content was measured using phosphomolybdic acid colorimetry according to the ATP assay kit (G0815W96) purchased from Suzhou Grace Biotechnology Co. (Suzhou, China). For the enzyme assays, superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured using a SOD detection kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and catalase (CAT) activity was measured following the instruction of CAT detection kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and peroxidase (POD) activity was detected with a POD detection kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). T-AOC, mitochondrial complex I and V activities were measured by T-AOC assay kit, complex I assay kit and complex V (Solarbio, Beijing, China).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data from all treatments were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) by the SPSS statistical software package version 25 (SPSS Inc., USA). Significant differences between treatment means were identified by Student’s t-test and Duncan’s multiple range test at the p < 0.05. Origin (Origin 2019, USA) was used for figure construction.

3. Results

3.1. A panel of three complete Coptis mitogenomes and basic characteristics

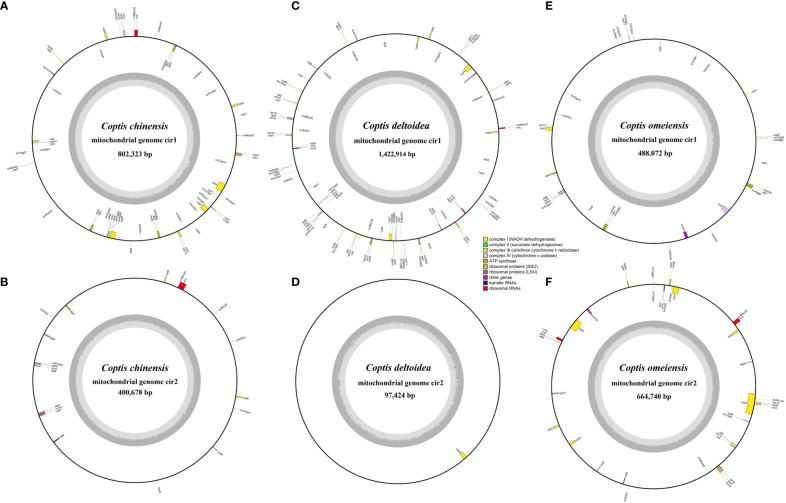

Based on analysis of DNA sequences generated from high-throughput sequencing, we performed mitochondrial genome assemblies of three Coptis species ( Supplementary Tables S3 , S4 and Supplementary Figure S1 ) and investigated the divergence of genome-wide sequence. The mitochondrial genome sizes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis are 1,425,403 bp, 1,520,338 bp and 1,152,812 bp, respectively ( Table 1 ), which are similar to the reported mitochondria of Anemone maxima (1,122,546 bp) (Park and Park, 2020) and are longer than the mitochondrial sequences of Aconitum kusnezoffii (440,720 bp) (Li et al., 2021), which also belong to in the Ranunculaceae species with reported mitochondrial sequences. The mitogenome of C. chinensis comprises six circular molecules with the size from 26,641 to 802,323 bp ( Figures 2A, B ; Supplementary Figure S2 ), whereas the C. deltoidea mitogenome was assembled into two circular molecules with sizes of 1,422,914 and 97,424 bp ( Figures 2C, D ), and the assembled mitochondrial genome of C. omeiensis is two complete circular scaffolds with the length of 488,072 and 664,740 bp ( Figures 2E, F ; Supplementary Table S5 ). The fragments migrated from the chloroplast genome accounted for a variable proportion (4.28%, 2.34% and 2.07%) of the three Coptis mitochondrial genomes, with the highest proportion in C. chinensis mitogenome ( Supplementary Figure S3 ).

Table 1.

Genomic features of Coptis mitochondrial genomes.

| Genome feature | C. chinensis | C. deltoidea | C. omeiensis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 1,425,403 | 1,520,338 | 1,152,812 |

| GC (%) | 45.7 | 45.8 | 45.8 |

| Number of genes | 84 | 86 | 68 |

| Number of tRNAs | 35 | 30 | 26 |

| Number of rRNAs | 2 | 5 | 3 |

| Number of PCGs | 47 | 51 | 39 |

| Cis-spliced introns | 16 | 16 | 15 |

| Number of large repeats (> 1 kb) |

22 | 31 | 4 |

| Total length of PCGs (bp) | 37,224 (2.61%) | 36,273 (2.38%) | 31,878 (2.77%) |

| Total length of tRNAs (bp) | 2,571 (0.18%) | 2,229 (0.15%) | 1,925 (0.17%) |

| Total length of rRNAs (bp) | 7,522 (0.53%) | 6,877 (0.45%) | 6,015 (0.52%) |

| Total length of cis-spliced introns (bp) | 31,053 (2.18%) | 29,749 (1.96%) | 26,311 (2.28%) |

| Mitochondrial DNA of chloroplast origin (bp) |

61,038 (4.28%) | 35,596 (2.34%) | 23,847 (2.07%) |

| Gross length of long repeats (bp) | 293,491 (20.59%) | 692,208 (45.53%) | 78,461 (6.81%) |

Figure 2.

Circular gene map of three Coptis mitogenomes. (A, B) The two large molecules of C. chinensis mitogenome. (C, D) The circular map of two molecules of C. deltoidea mitogenome. (E, F) The circular map of two molecules of C. omeiensis mitogenome. Genes shown on the outside and inside of the circle are transcribed clockwise and counterclockwise, respectively. The dark gray region in the inner circle represents GC content.

Overall guanine-cytosine (GC) content of the three Coptis species are 45.7%, 45.8% and 45.8% respectively ( Supplementary Table S5 ), indicating mitochondrial DNA similarity between these species and other angiosperms. The three complete Coptis mitogenomes encode 68-86 predicted functional genes, including 39-51 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 26-35 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes specifying 16-20 amino acids, and 2-5 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes and share nearly intron content accounting for 2.18%, 1.96%, and 2.28% of the Coptis mitochondrial genomes ( Table 1 ). Most PCGs have no introns, however, nine genes (nad1, nad2, nad4, nad5, nad7, cox2, ccmFC, rps3, rps10) are found to contain one or more introns in three Coptis mitochondrial genomes ( Table 2 ). The distribution of amino acid residues across the mitochondrial proteins share very highly similarity in Ranunculaceae plants ( Supplementary Figure S3 ). Moreover, a total of 637, 605 and 653 RNA editing sites is predicted in PCGs of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis respectively ( Supplementary Figure S4 and Supplementary Table S6 ). Among the functionally different genes, respiratory complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) genes, cytochrome C biogenesis genes and transport membrance protein (mttB) exhibit the largest average numbers of editing sites ( Supplementary Figure S4 ).

Table 2.

Gene profile and organization of the C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis mitogenomes.

| Group of genes | C. chinensis | C. deltoidea | C. omeiensis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) |

nad1 *, nad2***, nad3, nad4 ***, nad4L, nad5 *, nad6(3), nad7 ****, nad9 |

nad1

*(2), nad2

*, nad3, nad4

***, nad4L(2), nad5

*, nad6(2), nad7 ****, nad9 |

nad1 *, nad2 **, nad3, nad4 ***, nad4L, nad5 *(2), nad6, nad7 ****, nad9 |

| Complex II (succinate dehydrogenase) |

sdh4(2) | sdh4 | sdh3, sdh4 |

| Complex III (ubichinol cytochrome c reductase) |

cob | cob(2) | cob |

| Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) |

cox1, cox3(2) | cox1, cox2 *(2), cox3 | cox1, cox2 *, cox3 |

| Complex V (ATP synthase) |

atp1(3), atp4, atp6, atp8(2), atp9(5) |

atp1, atp4 (2), atp8, atp9 (6) |

atp1(2), atp4, atp6, atp8, atp9(2) |

| Cytochrome c biogenesis | ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc *, ccmFN | ccmB, ccmC, ccmFN | ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc *, ccmFN |

| Small subunit ribosomal proteins (SSU) | rps3 *(2), rps7(2), rps10 *, rps11, rps12, rps13, rps14, rps19 |

rps3

*(2), rps4, rps7, rps10

*, rps11(2), rps12, rps13(2), rps14(2), rps19(2) |

rps3 *, rps4, rps7, rps10 *, rps11, rps12, rps13, rps14, rps19 |

| Large subunit ribosomal proteins (LSU) | rpl5, rpl16(2) | rpl5(2), rpl16(2) | rpl5, rpl16 |

| Transfer RNAs | trnA-CGC(2), trnC-GCA(2), trnD-GTC, trnE-TTC(4), trnF-AAA(3), trnfM-CAT, trnG-GCC, trnH-GTG(2), trnI-CAT, trnI-TAT, trnK-TTT(2), trnL-CAA, trnL-TAA, trnM-CAT(5), trnN-GTT, trnQ-TTG, trnR-ACG, trnS-TGA, trnT-GGT, trnV-GAC, trnW-CCA, trnY-GTA | TrnC-GCA, trnD-GTC, trnE-TTC(4), trnF-AAA, trnfM-CAT(2), trnG-GCC, trnH-GTG, trnI-TAT, trnK-TTT(3), trnL-TAA(4), trnM-CAT(3), trnN-GTT(2), trnQ-TTG(2), trnT-GGT, trnW-CCA, trnY-GTA(2) | TrnC-GCA, trnD-GTC, trnE-TTC(2), trnF-AAA, trnfM-CAT(2), trnG-GCC(2), trnH-GTG(2), trnI-TAT(2), trnK-TTT(4), trnL-TAA(2), trnM-CAT, trnN-GTT, trnQ-TTG(2), trnT-GGT, trnW-CCA, trnY-GTA |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrnL(2) | rr5(2), rrL, rrS(2) | rrn5, rrnL, rrnS |

| Transport membrane protein | mttB | mttB | mttB |

*for introns, and the number of *represent the number of introns. For example, ***represents the number of three introns. Gene(2): The numbers after the gene names indicate the number of copies of multi-copy genes. For example, nad6(2) represents that two copies of nad6 are found in the mitogenome.

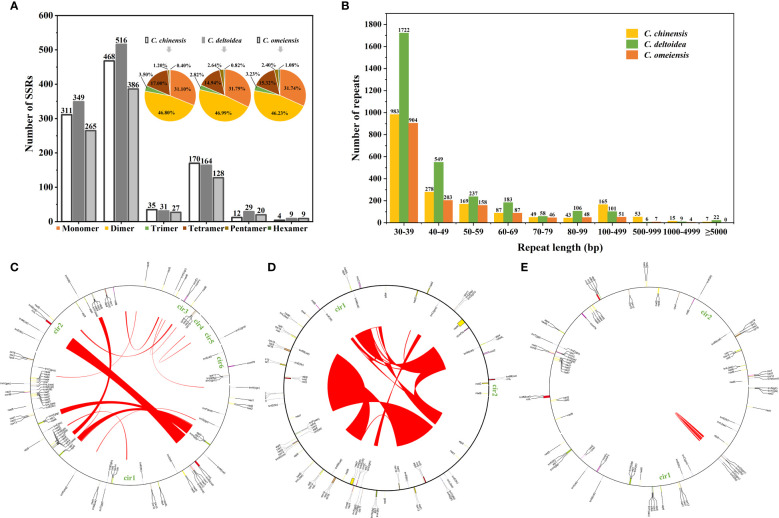

3.2. Repeats and structural variation among the three Coptis mitochondrial genomes

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) are sequence-repeating units with 1-6 nucleotides. 1,000, 1,098, and 835 SSRs were identified in the mitochondrial genomes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis, and Figure 3A displays the proportion of each kind. Among the three Coptis species, dimer repeats comprised 46.23- 46.99% of the total, followed by monomer repeats at 31.10-31.79%. Further analysis of the repeat unit of SSRs indicated that dinucleotide repeats (AG/CT) were more prevalent than the other repeat types. Based on the REPuter, we identified 1,849, 2,993 and 1,508 long repeats (> 30 bp) belonging to forward repeats in the mitogenomes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis. The total length of the long repeats was 293,491 bp, 692,208 bp and 78,461 bp, accounting for 20.59%, 45.53% and 6.81% of the entire mitogenomes, respectively. Most repeats were 30–49 bp long, whereas 22, 31 and 4 repeats were longer than 1,000 bp in the three Coptis species, respectively ( Figure 3B ). The largest repeats were 39,327 bp, 150,222 bp and 2,270 bp in the mitogenomes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis ( Figures 3C–E ).

Figure 3.

Detected repeats in the mitochondrial genomes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis. (A) Type and proportion of detected SSRs. (B) Length distribution of long repeats in the Coptis mitochondrial genomes. Histograms display the number of repeats with given lengths. (C–E) The locations of the large repeats (>1,000 bp) in the mitochondrial genomes of three Coptis species.

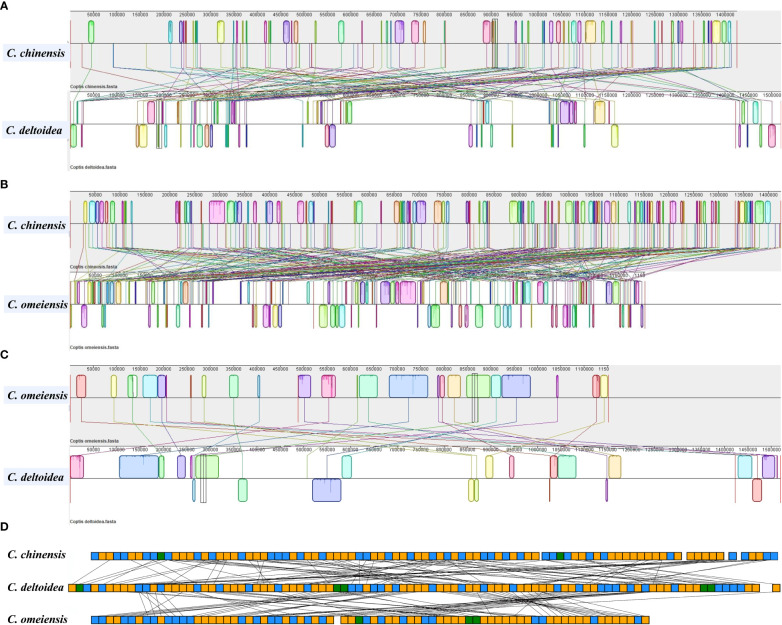

To further investigate structural variations in Coptis mitogenomes, the mitochondrial genome rearrangement and collinearity of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis were compared using the Mauve programs. Synteny analysis showed that there were many homologous regions among the three Coptis species ( Supplementary Table S7 ). A total of 246 synteny blocks were found between C. chinensis and C. omeiensis mitogenomes. And relatively long synteny blocks were found between C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis mitogenomes with the longest block being 62,375 bp in length. The relative positions of these homologous regions were different, indicating abundant rearrangements and inversions within the three mitogenomes which were also related to the differences in relative order of genes in the three Coptis species ( Figure 4 ). Different amounts and sizes of the locally collinear blocks and the expansion or contraction of regions between homologous sequences promoted the size dynamics of the Coptis mitogenomes.

Figure 4.

Colinearity and rearrangement analysis of C. deltoidea, C. omeiensis, and C. chinensis. (A–C) Mauve comparison of the three Coptis mitogenomes. (D) Relative order of PCGs in the three Coptis species. The orange, blue and green blocks represent CDS, tRNA and rRNA, respectively.

3.3. Phylogenetic analysis, gene loss and multi-copy gene of three Coptis mitogenomes

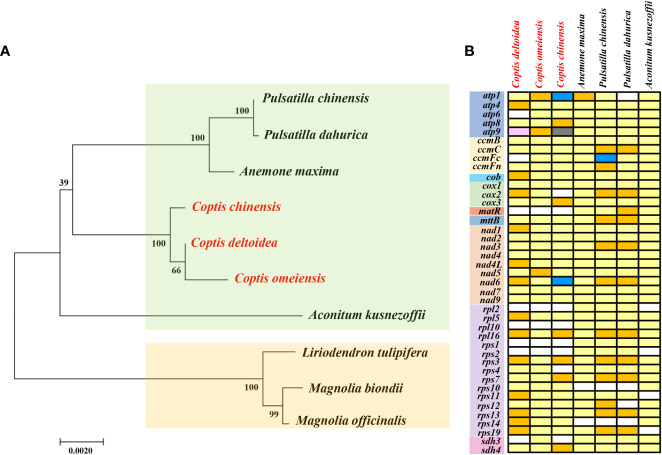

Mitochondrial genomes provide important genetic information for phylogenetic studies of different species (Xia et al., 2022). The ML tree inferred from 9 conserved mitochondrial PCG genes of 29 species from 19 families revealed that six Ranunculales species (Liriodendron tulipifera, Aconitum kusnezoffii, Anemone maxima, C. chinensis, C. deltoidea, and C. omeiensis) clustered closely together into one clade ( Supplementary Figure S6 ). To further reveal the phylogenetic relationships of the three Coptis species, a phylogenetic tree was constructed with three Magnoliaceae plants as outgroups ( Figure 5A ). It also strongly supports the closely related phylogenetic relationship of three Coptis spcies.

Figure 5.

The phylogenetic relationships (A) and PCGs distribution of three Coptis species and other 4 Ranunculaceae species (B). The Maximum Likelihood tree was constructed based on the sequences of 23 conserved protein-coding genes. Outgroup: Liriodendron tulipifera, Magnolia officinalis and M. biondii. About PCGs distribution, white boxes indicate that the gene is not present in the mt genomes. Light yellow, golden, blue, black and pink boxes indicate that one, two, three, five and six copies exist in the particular mitochondrial genomes, respectively.

Mitochondrial gene content is highly variable across extant angiosperm and the loss of PCGs occurs frequently, even in closely related species (Adams and Palmer, 2003). In comparison with the 41 protein-coding genes inferred to be present in the ancestral mitogenome of angiosperms (Guo et al., 2016), the matR, rpl2, rpl10, rps1 and rps2 were lost in C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis species ( Figure 5B ). In most land plants, the ribosomal proteins, cytochrome c biogenesis and succinate dehydrogenase genes were highly variable. The high diversity in the gene content among different angiosperm mitochondrial genomes was attributed to the variety of ribosomal protein genes (Liao et al., 2018). In addition, sdh3 was lost in C. chinensis and C. deltoidea, and the cox2 and rps4 were lost in C. chinensis mitochondrial genome, whereas the atp6 and ccmFc were lost in C. deltoidea. Overall, C. omeiensis has the relatively complete PCGs among the three Coptis species ( Figure 5B ).

Multi-copy genes are pervasive in plant mitochondrial genome (Fang et al., 2021). In C. chinensis mitogenome, atp8, cox3 and sdh4 were located in the large repeat R7 (11,718 bp), which creates duplicate copies of these genes. And three copies of atp1 and two copies of atp9 are associated with large repeat sequences R2 (16,570 bp) and R5 (15,647 bp). In addition, rpl16, rps3, rps7 were also duplicated in C. chinensis mitogenome ( Figure 4C ). In C. deltoidea mitogenome, the genes including atp4, cob, cox2, nad1, nad4L, nad6, rpl5, rpl16, rps3, rps11, rps13, rps14, rps19 are duplicated by the large repeats of R1, R2, R5 and R8 ( Figure 4D ). Whereas, only atp1, atp9 and nad5 were duplicated in C. omeiensis mitogenome ( Figure 5B ).

3.4. PCGs under selected pressure in Coptis mitochondrial genomes mainly related to the mitochondrial respiratory chain

The nonsynonymous-to-synonymous substitution ratio (Ka/Ks) is used to reflect the selective pressure and the evolutionary dynamics of PCGs. In this study, the Ka/Ks ratio was determined by 36 PCGs in C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis ( Table 3 ). The PCGs shared between C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis were close homologs, as the Ka and Ks ratio of 27 PCGs was 0. The genes with sequence differences included atp9, nad1, nad2, nad5 and rps3. Among them, the Ka/Ks ratios of nad1, nad2 and rps3 were greater than 1, which indicated these genes had been under positive selection during evolution. Differences in some PCGs were found when comparing C. chinensis mitogenome to that of C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis. The Ka/Ks ratios of atp1, atp6, atp9, nad5, nad6, rpl5, rps3, rps7, rps11 and rps19 were less than 1, indicating that these PCGs were subject to purified selection during evolution, which may play vital roles in stabilizing the normal function of mitochondria (Betrán et al., 2006). These results indicated that the PCGs under selected pressure in Coptis mitochondrial genomes mainly belong to NADH dehydrogenase, ATP synthase and ribosomal proteins, which are closely related to the mitochondrial respiratory chain. In addition, the Ka/Ks ratios of nad1 and nad2 were greater than 1, indicating that nad1 and nad2 gene in C. chinensis mitogenome were under positive selection.

Table 3.

Ka/Ks ratios of PCGs in C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis.

| Gene |

Ka/Ks

(C. deltoidea vs C. omeiensis) |

Ka/Ks

(C. deltoidea vs C. chinensis) |

Ka/Ks

(C. chinensis vs C. omeiensis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| atp1 | NaN | 0.7089 | 0.7089 |

| atp9 | 0.0633 | 0.3634 | 0.3703 |

| nad1 | 1.1793 | 0.0000 | 1.0506 |

| nad2 | 1.5681 | 1.3961 | 1.0443 |

| nad5 | 0.5787 | 0.2194 | 0.3846 |

| nad6 | NaN | 0.8762 | 0.8762 |

| nad7 | NaN | * | * |

| rpl5 | NaN | 0.4374 | 0.4374 |

| rps3 | 2.9681 | 0.5424 | 0.4996 |

| rps7 | NaN | 0.1296 | 0.1296 |

| rps10 | NaN | * | * |

| rps11 | NaN | 0.1445 | 0.1445 |

| rps19 | NaN | 0.4182 | 0.4182 |

| sdh4 | NaN | * | * |

When Ks = 0, the value cannot be calculated, it was represented by *. When Ka = 0 and Ks = 0, it was represented by NaN.

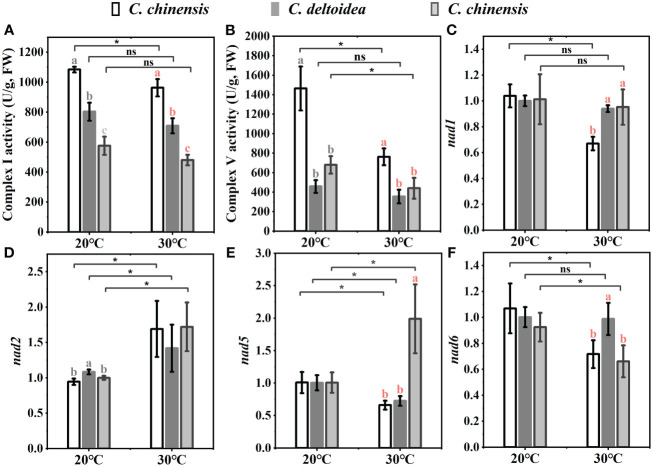

3.5. The expressions of gene members of NADH dehydrogenase which were under selection pressure and the activities of complex I and complex V and under heat stress

In China, C. deltoidea grows mainly in the montane understory at altitudes between 1600 and 2200 m, while C. omeiensis is mainly distributed at altitudes between 1000 and 1700 m ( Figure 1 ). Differently, the C. chinensis grows widely at altitudes from 500 to 2000 m. The three Coptis species exhibit significant differences in the altitudinal distribution ranges, indicating differences in thermo-tolerance. Mitochondria are dynamically involved in the stress response and key agents in how plants respond to oxidative stress (Jacoby et al., 2012). To preliminary characterize the biological functions of mitochondria in the environmental adaptation of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis, we compared the expressions of members of NADH dehydrogenase (nad1, nad2, nad5 and nad6) which were under selection pressure and activities of complex I and complex V of three Coptis species grown at 20°C and 30°C for 5 d. The high-temperature stress increased expression levels of nad2 and decreased expression levels of nad6 in three Coptis species. Compared with 20°C, nad1 expression in C. chinensis was significantly reduced under 30°C treatment, while the expression levels of nad1 in C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis were not significantly changed. Moreover, the activity of complex I (1,084.65 ± 19.40 U/g) and complex V (1,463.89 ± 225.56 U/g) of C. chinensis were maintained at a higher level compared to that of C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis at 20°C ( Figures 6A, B ). Meanwhile, the activity levels of complex I and complex V were found to decrease under heat stress (i.e. 30°C) in the three Coptis species, with the activities of complex I and complex V of C. chinensis remaining significantly higher than those of C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis ( Figure 6 ).

Figure 6.

The activities of complex I (A) and complex V (B), and the expressions of some PCGs involved in oxidative phosphorylation (C–F) of three Coptis species under 20°C and 30°C. Different letters with different color (gray and red) indicate a significant difference at P < 0.05 between three Coptis species under 20°C and 30°C, respectively. The asterisks indicate a significant difference between plants grown at 20°C and 30°C as determined by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) and ns means no difference between the treatment. Each column represents the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates.

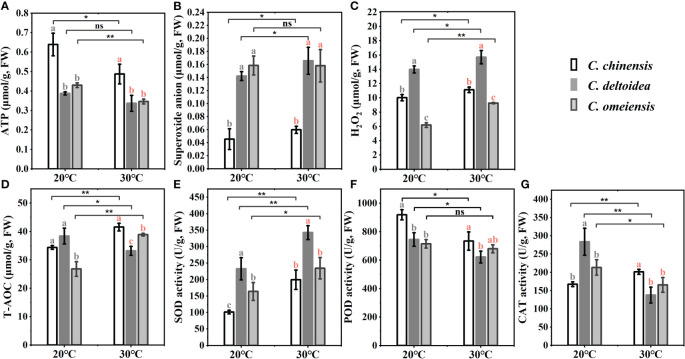

3.6. Concentration of superoxide anion, H2O2 and ATP, and antioxidant enzyme activity under heat stress

The mitochondrial DNA-encoded electron transport chain (ETC) complex and ATP synthase are closely linked to the production of ROS and ATP, which play important roles in plant resistance to stress. we found that the ATP content of C. chinensis was significantly higher than that of C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis at 20 °C, while the ATP content of C. omeiensis was slightly higher than that of C. deltoidea, but the significant difference was not found. The decreased level of ATP in C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis under heat stress was noticed, and the ATP concentration of C. chinensis remained significantly higher than that of C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis ( Figure 7 ). Meanwhile, the content of superoxide anion and H2O2 at low levels in C. chinensis at 20°C. High temperature stress caused a significant increase in ROS levels of the three Coptis species. The ROS levels of C. deltoidea were significantly higher than those of C. chinensis and C. omeiensis. The SOD and CAT activities and T-AOC (total antioxidant activity) of C. chinensis at 20 °C were lower than those of C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis. In three Coptis species, SOD activity was stimulated, while POD activity was depressed by heat stress ( Figure 7 ). A significant increase was detected in CAT activity in C. chinensis and a decrease was noted in those in C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis as compared to the plants under normal temperature ( Figure 7 ). Moreover, the concentration of T-AOC increased significantly in C. chinensis and C. omeiensis, while the T-AOC decreased significantly in C. deltoidea, and the T-AOC of C. chinensis under heat stress was more stimulated than that of C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis ( Figure 7 ).

Figure 7.

The concentration of superoxide anion, H2O2, ATP and T-AOC (A–D) and the activities of SOD, POD and CAT (E–G) of three Coptis species under 20°C and 30°C. Different letters with different color (gray and red) indicate a significant difference at P < 0.05 between three Coptis species under 20°C and 30°C, respectively. The asterisks indicate a significant difference between plants grown at 20°C and 30°C as determined by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) and ns means no difference between the treatment. Each column represents the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates.

4. Discussion

Mitochondria are the respiration sites of plants, which generate the ATP needed for cell maintenance and growth (Millar et al., 2011). Mitochondrial genome analysis is of great importance for understanding the biological functions of mitochondria, molecular evolution, genome structure and phylogenetic relationships of different plant species, especially closely related species (Niu et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). As pharmaceutically and economically important plants, C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis have different distribution ranges and requirements for environmental conditions. Under the extreme high temperature weather in summer, most leaves of C. deltoidea at the altitude of 1800 m were withered, while C. chinensis grew well ( Supplementary Figure 7 ). Therefore, to preliminary reveal the differential mechanism of thermal acclimation, this study is the first to comprehensively analyze the complete mitochondrial genomes of three Coptis species.

4.1. Mitochondrial genome comparison and variation of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis

Mitogenomes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis are conserved in GC content (45.7%, 45.8% and 45.8%) but differ substantially in genome size (1,425,403 bp, 1,520,338 bp and 1,152,812 bp), composition, and structure. The size variations in plant mitogenomes are primarily attributed to the proliferation of repeats, the migration of foreign sequences, and gain or loss of large intragenetic segments (Gualberto and Newton, 2017; Wu et al., 2022). Plant mitochondrial genomes have abundant non-tandem repeats (Wynn and Christensen, 2019). Previous study of several mitogenomes of Fabaceae species found that their size varied from 271,618 bp to 729,504 bp with large proportion of repeats (2.9–60.6%) accounting for most of the size variations (Choi et al., 2019). Positive correlations between mitogenome size and repeat content were identified in Rosaceae species (Sun et al., 2022). In our study, the proportion of long repeat sequences (>30 bp) in the C. deltoidea mitogenome (45.53%) was higher than that of C. chinensis (20.59%) and C. omeiensis (6.81%). These repeats may have contributed to the increase in the mitogenome size of C. deltoidea (bp). However, the mitogenome size of C. chinensis was close to that of C. deltoidea, which means that the mitogenome size is by no means only determined by repeats. The foreign sequences originating from chloroplast, nuclear, and mitochondrion of other species also contribute to the variable mitogenome size (Goremykin et al., 2012; Rice et al., 2013). Furthermore, large repetitive sequences and mitogenome expansion might led to multi-copy genes in plant mitogenomes (Miao et al., 2022). In C. deltoidea mitogenome, 16 large repeat sequences (>10,000 bp) were found. Among them, R1, R2, R5 and R8 were related to the duplicate copies of genes belonging to NADH dehydrogenase (nad1, nad4L and nad6), ubichinol cytochrome c reductase (cob), complex IV (cox1 and cox2), cytochrome c oxidase (cox2), ATP synthase (atp4) and small subunit ribosomal proteins (rps3, rps11, rps14, rps19). In C. chinensis mitogenome, three copies of atp1 and two copies of atp8, atp9, cox3 and sdh4 were also attributed to large repeats.

Although the phylogenetic analysis and synteny analysis indicated the closely related relationship and many homologous regions among the three Coptis species, large-scale gene rearrangements were detected in the mitochondrial genome of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis. In angiosperms, the accumulation of repeat sequences and repeat-mediated inversion are the predominant mechanism of rearrangement in mitogenome (Cole et al., 2018). The abundant rearrangements and significant variation in gene orders among these closely related Coptis species may be attributed to repeat sequences that were widely present in the mitogenomes.

Ka/Ks analysis of mitochondrial genome from the three Coptis species showed that the PCGs shared between C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis were close homologs. In addition, most of the PCGs in the three Coptis species were subject to purified selection as Ka/Ks ratios were less than 1.0, with nad5 and nad6 having relatively high Ka/Ks ratios. However, we also found genes in which the Ka/Ks >1, such as nad1, nad2 and rps3. The results indicated that several members of NADH dehydrogenase (complex I) had been under pressure selection during evolution. Mitochondrial complex I is the first and largest respiratory complex required in the process of the process of oxidative phosphorylation to generate ATP, which is involved in the mitochondrial electron transport chain and is one of the major production sites of ROS (superoxide anion) (Huang et al., 2016; Subrahmanian et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022a). Mutations in the members of complex I would change the metabolic capacity which may further affect adaptability of the organism (Zhao et al., 2022).

4.2. The different thermal acclimation in the three Coptis species and the physiological indices of mitochondrial complex, antioxidants and related substances

C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis exhibit significant differences in the altitudinal distribution ranges and thermal acclimation. Currently, C. chinensis is the most widely cultivated and is the dominant species on the market due to its environmental adaptability and ability to grow at low altitudes. In contrast, C. deltoidea suitable for growing alpine and humid climatic conditions, is highly susceptible to heat stress ( Supplementary Figure 7 ) and cannot be grown in areas with higher temperatures (Li et al., 2020). To understand the mechanism of the differences in heat acclimation of the three Coptis plants, mitochondrial genes, mitochondrial complex and antioxidase activities, and the physiological indices of related substances were compared under heat stress. The results showed that high temperature stress adversely affected the mitochondrial complex I and V, antioxidant enzyme system, ROS accumulation and ATP production of three Coptis species. It has been shown that abiotic stress can impair the complex I activity, while mitochondrial ROS produced during stress could occur by inhibition of the ETC (Møller, 2001; Jacoby et al., 2011). However, inhibition of complex I leads to a slowing of electron flow through the ETC and a decrease in respiration, thus inhibiting the synthesis of ATP (Rustin and Lance, 1986; Belhadj Slimen et al., 2014).

Compared to the control treatment (20°C), C. chinensis adapted better to high temperature through the activation of antioxidant enzymes, increase of T-AOC and maintenance of low ROS accumulation, which were suggested as the factors that maintained normal growth at lower altitudes. Nevertheless, the CAT activity and T-AOC reduced, ROS accumulation increased in the warming sensitive C. deltoidea under heat stress, which may indicate increased ROS production as well as diminished scavenging capacity of C. deltoidea. However, when ROS formation exceeds normal levels, it may cause damage to membranes and plant cell functions (Rhoads et al., 2006). The distribution altitude of C. omeiensis is lower than that of C. deltoidea and its range is narrower than that of C. chinensis. High temperature stress elevated the antioxidant capacity and ROS accumulation of C. omeiensis, but ROS accumulation was lower than that of C. deltoidea. Previous studies have shown that the thermotolerant cultivar greater activate antioxidant enzyme system compared to the sensitive cultivar. Increased activity of these antioxidant enzymes suppressed the levels of superoxide anion and H2O2 levels, which were otherwise high in sensitive cultivars (Xu et al., 2015; Tiwari et al., 2022). However, plants have evolved complex adaptive mechanisms to cope with environmental stress, which may involve several metabolic adjustments, gene expression and morpho-physiological alterations (Yadav et al., 2016; Tiwari and Yadav, 2019). Therefore, further studies are necessary to explore genes and molecular regulation mechanism involved in different heat acclimation in Coptis species to further comprehensive understanding the environmental adaptation mechanisms, which is of great significance for the breeding of heat-resistant varieties under the background of global warming and extreme heat intensification (Xu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022b).

5. Conclusions

In this study, we first assembled and characterized the complete mitochondrial genomes of C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis, the important medicinal members of the Ranunculaceae family. The mitogenomes are 1,425,403 bp, 1,520,338 bp and 1,152,812 bp, and harbors 68-86 predicted functional genes including 39-51 PCGs, 26-35 tRNAs and 2-5 rRNAs. The codon usage, repeat sequences, RNA editing edits, gene migration from chloroplast, repeat sequences and genome rearrangement in the Coptis mitochondrial genomes were extensively analyzed, contributing to our understanding of conservation and variation of Coptis mitogenomes during the evolution. C. chinensis, C. deltoidea and C. omeiensis exhibit significant differences in the altitudinal distribution ranges and thermal acclimation. High temperature stress adversely affected the mitochondrial complex I and V, antioxidant enzyme system, ROS accumulation and ATP production of three Coptis species. C. chinensis with strong environmental adaptability could effectively enhance antioxidant capacity, scavenge ROS, and maintain energy supply. This study provides comprehensive information on the Coptis mitogenomes and is of great importance to elucidate the mitochondrial functions, understand the different thermal acclimation mechanisms of Coptis plants, and breed heat-tolerant varieties.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, OP466716 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466716, OP466717 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466718, OP466718 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, OP466716 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466716, OP466717 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466717, OP466721 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466718, OP466722 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466722, OP466723 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466723, OP466724 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466724, OP466725 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466725.

Author contributions

FZ, ZY, YM designed the project and the strategy, YL, WK, and XC contributed to plant sample collection and processing. FZ, YL, and WK work on genome assembly, annotation and comparative analyses. FZ, YL, TZ and BX wrote and revised the manuscript. ZY and YM helped with a critical discussion on the work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (U19A2011) and Sichuan Development Service Center for Traditional Chinese Medicine-a major project for the development of traditional Chinese medicine industry (510201202109711).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1166420/full#supplementary-material

References

- Adams K. L., Palmer J. D. (2003). Evolution of mitochondrial gene content: gene loss and transfer to the nucleus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29, 380–395. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00194-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alverson A. J., Wei X., Rice D. W., Stern D. B., Barry K., Palmer J. D. (2010). Insights into the evolution of mitochondrial genome size from complete sequences of Citrullus lanatus and Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 1436–1448. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier S., Thiel T., Münch T., Scholz U., Mascher M. (2017). MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belhadj Slimen I., Najar T., Ghram A., Dabbebi H., Ben Mrad M., Abdrabbah M. (2014). Reactive oxygen species, heat stress and oxidative-induced mitochondrial damage. a review. Int. J. Hyperthermia 30, 513–523. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2014.971446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betrán E., Bai Y., Motiwale M. (2006). Fast protein evolution and germ line expression of a Drosophila Parental gene and its young retroposed paralog. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 2191–2202. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi C., Qu Y., Hou J., Wu K., Ye N., Yin T. (2022). Deciphering the multi-chromosomal mitochondrial genome of populus simonii. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.914635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., He X., Priyadarshani S. V. G. N., Wang Y., Ye L., Shi C., et al. (2021). Assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of Suaeda glauca . BMC Genomics 22, 167. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07490-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi I.-S., Schwarz E. N., Ruhlman T. A., Khiyami M. A., Sabir J. S. M., Hajarah N. H., et al. (2019). Fluctuations in fabaceae mitochondrial genome size and content are both ancient and recent. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 448. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-2064-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole L. W., Guo W., Mower J. P., Palmer J. D. (2018). High and variable rates of repeat-mediated mitochondrial genome rearrangement in a genus of plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 2773–2785. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling A. C. E., Mau B., Blattner F. R., Perna N. T. (2004). Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 14, 1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Coster W., D’Hert S., Schultz D. T., Cruts M., Van Broeckhoven C. (2018). NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 34, 2666–2669. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S., Chen L., Liu Y., Wang Y., Zhang S., Yang L., et al. (2020). The draft mitochondrial genome of Magnolia biondii and mitochondrial phylogenomics of angiosperms. PloS One 15, e0231020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S., Zhao C., Chen F., Liu Y., Zhang S., Wu H., et al. (2018). The complete mitochondrial genome of the early flowering plant Nymphaea colorata is highly repetitive with low recombination. BMC Genomics 19, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4991-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin G., Daoud H., Xia J. (2008). Relative rates of synonymous substitutions in the mitochondrial, chloroplast and nuclear genomes of seed plants. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 49, 827–831. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Liu F., Jia Q., Du H., Chen W., Ruan J., et al. (2022). Fragaria Mitogenomes evolve rapidly in structure but slowly in sequence and incur frequent multinucleotide mutations mediated by microinversions. New Phytol. 236, 745–759. doi: 10.1111/nph.18334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang B., Li J., Zhao Q., Liang Y., Yu J. (2021). Assembly of the complete mitochondrial genome of Chinese plum (Prunus salicina): characterization of genome recombination and RNA editing sites. Genes 12, 1970 doi: 10.3390/genes12121970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goremykin V. V., Lockhart P. J., Viola R., Velasco R. (2012). The mitochondrial genome of Malus domestica and the import-driven hypothesis of mitochondrial genome expansion in seed plants. Plant J. 71, 615–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner S., Lehwark P., Bock R. (2019). OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W59–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualberto J. M., Newton K. J. (2017). Plant mitochondrial genomes: dynamics and mechanisms of mutation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 68, 225–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-112232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Grewe F., Fan W., Young G. J., Knoop V., Palmer J. D., et al. (2016). Ginkgo and Welwitschia mitogenomes reveal extreme contrasts in gymnosperm mitochondrial evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1448–1460. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Hou P., Fan G., Arain S., Peng C. (2014). Comprehensive analyses of molecular phylogeny and main alkaloids for Coptis (Ranunculaceae) species identification. Biochem. Systematics Ecol. 56, 88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2014.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heydari M., Zanfardino A., Taleei A., Shahnejat Bushehri A. A., Hadian J., Maresca V., et al. (2018). Effect of heat stress on yield, monoterpene content and antibacterial activity of essential oils of Mentha x piperita var. mitcham and Mentha arvensis var. piperascens. Molecules 23, 1903. doi: 10.3390/molecules23081903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Van Aken O., Schwarzländer M., Belt K., Millar A. H. (2016). The roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in cellular signaling and stress response in plants. Plant Physiol. 171, 1551–1559. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby R. P., Li L., Huang S., Pong Lee C., Millar A. H., Taylor N. L. (2012). Mitochondrial composition, function and stress response in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 54, 887–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2012.01177.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby R. P., Taylor N. L., Millar A. H. (2011). The role of mitochondrial respiration in salinity tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 614–623. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-E., Han J.-E., Murthy H. N., Kwon H.-J., Lee G.-M., Park S.-Y. (2022). Response of cnidium officinale makino plants to heat stress and selection of superior clones using morphological and molecular analysis. Plants 11, 3119 doi: 10.3390/plants11223119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov M., Yuan J., Lin Y., Pevzner P.A. (2019). Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 540–546. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar L., Nageswara-Rao M., Ortega-Rodriguez S., Dugas D. V., Straub S., Cronn R., et al. (2018). PacBio-based mitochondrial genome assembly of Leucaena trichandra (Leguminosae) and an intrageneric assessment of mitochondrial RNA editing. Genome Biol. Evol. 10, 2501–2517. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. (2018). MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S., Choudhuri J. V., Ohlebusch E., Schleiermacher C., Stoye J., Giegerich R. (2001). REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levings C. S., Brown G. G. (1989). Molecular biology of plant mitochondria. Cell 56, 171–179. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90890-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (2016). Minimap and miniasm: fast mapping and de novo assembly for noisy long sequences. Bioinformatics 32, 2103–2110. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (2018). Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Fan G., He Y. (2020). Predicting the current and future distribution of three Coptis herbs in China under climate change conditions, using the MaxEnt model and chemical analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 698, 134141. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.-L., Tan L.-H., Wang Y.-F., Luo C.-D., Chen H.-B., Lu Q., et al. (2019). Comparison of anti-inflammatory effects of berberine, and its natural oxidative and reduced derivatives from rhizoma coptidis in vitro and in vivo . Phytomedicine 52, 272–283. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.09.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Tang H., Luo H., Tang J., Zhong N., Xiao L. (2023). Complete mitochondrial genome assembly and comparison of Camellia sinensis var. assamica cv. duntsa. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1117002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.-N., Yang Y.-Y., Xu L., Xing Y.-P., Zhao R., Ao W.-L., et al. (2021). The complete mitochondrial genome of Aconitum kusnezoffii rchb. (Ranales, ranunculaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 6, 779–781. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2021.1882894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao X., Zhao Y., Kong X., Khan A., Zhou B., Liu D., et al. (2018). Complete sequence of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) mitochondrial genome and comparative analysis with the mitochondrial genomes of other plants. Sci. Rep. 8, 12714. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30297-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Yang X., Gao Y. (2013). Mitochondrial DNA response to high altitude: a new perspective on high-altitude adaptation. Mitochondrial DNA 24, 313–319. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2012.760558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller I. M. (2001). Plant mitochondria and oxidative stress: electron transport, NADPH turnover, and metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 561–591. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina E., Kim S.-H., Yun M., Choi W.-G. (2021). Recapitulation of the function and role of ROS generated in response to heat stress in plants. Plants 10, 371. doi: 10.3390/plants10020371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., Chen H., Xu W., Liu C., Huang L. (2022). Cistanche Species mitogenomes suggest diversity and complexity in lamiales-order mitogenomes. Genes 13, 1791 doi: 10.3390/genes13101791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A. H., Whelan J., Soole K. L., Day D. A. (2011). Organization and regulation of mitochondrial respiration in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 79–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mower J. P. (2005). PREP-Mt: predictive RNA editor for plant mitochondrial genes. BMC Bioinf. 6, 96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee D., Chakraborty S. Coptis teeta: conservation and cultivation practice - a rare medicinal plant on earth. Curr. Invest. Agric. Curr. Res. 6, 845–851. doi: 10.32474/CIACR.2019.06.000244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y., Gao C., Liu J. (2022). Complete mitochondrial genomes of three Mangifera species, their genomic structure and gene transfer from chloroplast genomes. BMC Genomics 23, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08383-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogihara Y., Yamazaki Y., Murai K., Kanno A., Terachi T., Shiina T., et al. (2005). Structural dynamics of cereal mitochondrial genomes as revealed by complete nucleotide sequencing of the wheat mitochondrial genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 6235–6250. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osellame L. D., Blacker T. S., Duchen M. R. (2012). Cellular and molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial function. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 26, 711–723. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Park S. (2020). Large-Scale phylogenomics reveals ancient introgression in Asian Hepatica and new insights into the origin of the insular endemic hepatica maxima. Sci. Rep. 10, 16288. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73397-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R. K., Jain M. (2012). NGS QC toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PloS One 7, e30619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porebski S., Bailey L. G., Baum B. R. (1997). Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 15, 8–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02772108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L., Ma Y., Zhong F., Shen C. (2018). Comprehensive quality assessment for rhizoma coptidis based on quantitative and qualitative metabolic profiles using high performance liquid chromatography, Fourier transform near-infrared and Fourier transform mid-infrared combined with multivariate statistical analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 161, 436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran Q., Wang J., Wang L., Zeng H., Yang X., Huang Q. (2019). Rhizoma coptidis as a potential treatment agent for type 2 diabetes mellitus and the underlying mechanisms: a review. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 805. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson A. G., Møller I. M. (2011). “Mitochondrial electron transport and plant stress,” in Plant mitochondria advances in plant biology. Ed. Kempken F. (New York: NY: Springer; ), 357–381. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-89781-3_14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads D. M., Umbach A. L., Subbaiah C. C., Siedow J. N. (2006). Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. contribution to oxidative stress and interorganellar signaling. Plant Physiol. 141, 357–366. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D. W., Alverson A. J., Richardson A. O., Young G. J., Sanchez-Puerta M. V., Munzinger J., et al. (2013). Horizontal transfer of entire genomes via mitochondrial fusion in the Angiosperm Amborella . Science 342, 1468–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.1246275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivero R. M., Mittler R., Blumwald E., Zandalinas S. I. (2022). Developing climate-resilient crops: improving plant tolerance to stress combination. Plant J. 109, 373–389. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Moreno L., González V. M., Benjak A., Martí M. C., Puigdomènech P., Aranda M. A., et al. (2011). Determination of the melon chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequences reveals that the largest reported mitochondrial genome in plants contains a significant amount of DNA having a nuclear origin. BMC Genomics 12, 424. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rurek M. (2014). Plant mitochondria under a variety of temperature stress conditions. Mitochondrion 19, 289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustin P., Lance C. (1986). Malate metabolism in leaf mitochondria from the crassulacean acid metabolism plant kalanchoë blossfeldiana poelln. Plant Physiol. 81, 1039–1043. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.4.1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schattner P., Brooks A. N., Lowe T. M. (2005). The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W686–W689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman J. R., Sonthirod C., Naktang C., Pootakham W., Yoocha T., Sangsrakru D., et al. (2016). The two chromosomes of the mitochondrial genome of a sugarcane cultivar: assembly and recombination analysis using long PacBio reads. Sci. Rep. 6, 31533. doi: 10.1038/srep31533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skippington E., Barkman T. J., Rice D. W., Palmer J. D. (2015). Miniaturized mitogenome of the parasitic plant viscum scurruloideum is extremely divergent and dynamic and has lost all nad genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, E3515–E3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504491112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan D. B., Alverson A. J., Chuckalovcak J. P., Wu M., McCauley D. E., Palmer J. D., et al. (2012). Rapid evolution of enormous, multichromosomal genomes in flowering plant mitochondria with exceptionally high mutation rates. PloS Biol. 10, e1001241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small I. D., Schallenberg-Rüdinger M., Takenaka M., Mireau H., Ostersetzer-Biran O. (2020). Plant organellar RNA editing: what 30 years of research has revealed. Plant J. 101, 1040–1056. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D., Hao J., Fan D. (2020). Biological properties and clinical applications of berberine. Front. Med. 14, 564–582. doi: 10.1007/s11684-019-0724-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanian N., Remacle C., Hamel P. P. (2016). Plant mitochondrial complex I composition and assembly: a review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1857, 1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M., Zhang M., Chen X., Liu Y., Liu B., Li J., et al. (2022). Rearrangement and domestication as drivers of rosaceae mitogenome plasticity. BMC Biol. 20, 181. doi: 10.1186/s12915-022-01383-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari M., Kumar R., Min D., Jagadish S. V. K. (2022). Genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying root architecture and function under heat stress–a hidden story. Plant Cell Environ. 45, 771–788. doi: 10.1111/pce.14266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari Y. K., Yadav S. K. (2019). High temperature stress tolerance in maize (Zea mays l.): physiological and molecular mechanisms. J. Plant Biol. 62, 93–102. doi: 10.1007/s12374-018-0350-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Paer C., Bouchez O., Besnard G. (2018). Prospects on the evolutionary mitogenomics of plants: a case study on the olive family (Oleaceae). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 18, 407–423. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaser R., Sović I., Nagarajan N., Šikić M. (2017). Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27, 737–746. doi: 10.1101/gr.214270.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Shi X., Zhang R., Zhang K., Shao L., Xu T., et al. (2022. b). Impact of summer heat stress inducing physiological and biochemical responses in herbaceous peony cultivars (Paeonia lactiflora pall.) from different latitudes. Ind. Crops Products 184, 115000. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wang L., Lou G.-H., Zeng H.-R., Hu J., Huang Q.-W., et al. (2019). Coptidis rhizoma: a comprehensive review of its traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Pharm. Biol. 57, 193–225. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2019.1577466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Wang Y., Ni J., Li R., Zhu F., Wang R., et al. (2022. a). An MCIA-like complex is required for mitochondrial complex I assembly and seed development in maize. Mol. Plant 15, 1470–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhang R., Yun Q., Xu Y., Zhao G., Liu J., et al. (2021). Comprehensive analysis of complete mitochondrial genome of Sapindus mukorossi gaertn.: an important industrial oil tree species in China. Ind. Crops Products 174, 114210. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waszczak C., Carmody M., Kangasjärvi J. (2018). Reactive oxygen species in plant signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 69, 206–236. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick R. R., Judd L. M., Gorrie C. L., Holt K. E. (2017. a). Completing bacterial genome assemblies with multiplex MinION sequencing. Microb. Genom 3, e000132. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick R. R., Judd L. M., Gorrie C. L., Holt K. E. (2017. b). Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PloS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick R. R., Schultz M. B., Zobel J., Holt K. E. (2015). Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 31, 3350–3352. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.-Q., Liao X.-Z., Zhang X.-N., Tembrock L. R., Broz A. (2022). Genomic architectural variation of plant mitochondria–a review of multichromosomal structuring. J. Systematics Evol. 60, 160–168. doi: 10.1111/jse.12655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn E. L., Christensen A. C. (2019). Repeats of unusual size in plant mitochondrial genomes: identification, incidence and evolution. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 9, 549–559. doi: 10.1534/g3.118.200948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia L., Cheng C., Zhao X., He X., Yu X., Li J., et al. (2022). Characterization of the mitochondrial genome of Cucumis hystrix and comparison with other cucurbit crops. Gene 823, 146342. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2022.146342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang K.-L., Erst A. S., Xiang X.-G., Jabbour F., Wang W. (2018). Biogeography of Coptis salisb. (Ranunculales, ranunculaceae, coptidoideae), an eastern Asian and north American genus. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 74. doi: 10.1186/s12862-018-1195-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Burgess P., Huang B. (2015). Root antioxidant mechanisms in relation to root thermotolerance in perennial grass species contrasting in heat tolerance. PloS One 10, e0138268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Zhang L., Ou S., Wang R., Wang Y., Chu C., et al. (2020). Natural variations of SLG1 confer high-temperature tolerance in indica rice. Nat. Commun. 11, 5441 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19320-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S. K., Tiwari Y. K., Pavan Kumar D., Shanker A. K., Jyothi Lakshmi N., Vanaja M., et al. (2016). Genotypic variation in physiological traits under high temperature stress in maize. Agric. Res. 5, 119–126. doi: 10.1007/s40003-015-0202-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zancani M., Braidot E., Filippi A., Lippe G. (2020). Structural and functional properties of plant mitochondrial f-ATP synthase. Mitochondrion 53, 178–193. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan P., Wang F., Xia P., Zhao G., Wei M., Wei F., et al. (2022). Assessment of suitable cultivation region for Panax notoginseng under different climatic conditions using MaxEnt model and high-performance liquid chromatography in China. Ind. Crops Products 176, 114416. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Li J., Zhao X.-Q., Wang J., Wong G. K.-S., Yu J. (2006). KaKs_Calculator: calculating ka and ks through model selection and model averaging. Genomics Proteomics Bioinf. 4, 259–263. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(07)60007-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B., Gao S., Zhao M., Lv H., Song J., Wang H., et al. (2022). Mitochondrial genomic analyses provide new insights into the “missing” atp8 and adaptive evolution of mytilidae. BMC Genomics 23, 738. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08940-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, OP466716 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466716, OP466717 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466718, OP466718 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, OP466716 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466716, OP466717 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466717, OP466721 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466718, OP466722 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466722, OP466723 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466723, OP466724 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466724, OP466725 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OP466725.