Abstract

Background

Acute chest syndrome (ACS) is a leading cause of death in patients with sickle cell disease. Lung ultrasound (LUS) is emerging as a point-of-care method to diagnose ACS, allowing for more rapid diagnosis in the ED setting and sparing patients from ionizing radiation exposure.

Research Question

What is the diagnostic accuracy of LUS for ACS diagnosis, using the current reference standard of chest radiography?

Study Design and Methods

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines were followed for this systematic review and meta-analysis. Embase, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were used to compile all relevant studies. Two reviewers screened the studies for inclusion in this review. Cases of discrepancy were resolved by a third reviewer. Meta-analyses were conducted using both metadta and midas STATA software packages to retrieve summary receiver operating characteristic curves, sensitivities, and specificities. Three reviewers scored the studies with QUADAS-2 for risk of bias assessment.

Results

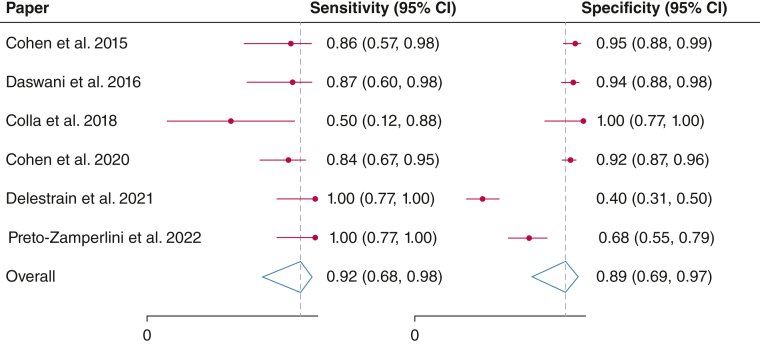

From a total of 713 unique studies retrieved, six studies were included in the final quantitative synthesis. Of these, five studies were in pediatric EDs. Two studies were conference abstracts and not published manuscripts. Data were available for 625 possible ACS cases (97% of cases in patients aged ≤ 21 years) and 95 confirmed ACS diagnoses (pretest probability of 15.2%). The summary sensitivity was 0.92 (95% CI, 0.68-0.98) and the summary specificity was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.69-0.97) with an area under the curve of the summary receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.94-0.97).

Interpretation

LUS has excellent sensitivity and very good specificity for ACS diagnosis and may serve as an initial point-of-care test to facilitate rapid treatment of ACS and spare pediatric patients from ionizing radiation; however, further research is warranted to improve the generalizability to the adult sickle cell disease population.

Key Words: acute chest syndrome, diagnosis, point-of-care testing, radiograph, sickle cell anemia, sickle cell disease, ultrasound

Graphical Abstract

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 1351

Take-home Points.

Study Question: What is the accuracy of lung ultrasound for acute chest syndrome diagnosis in a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature?

Results: From six studies and out of 625 patients, 97% of whom were 21 years old or younger, the summary sensitivity was 0.92 and the summary specificity was 0.89.

Interpretation: Lung ultrasound can be used to rule out acute chest syndrome in a primarily pediatric sample.

Acute chest syndrome (ACS) is an extremely common complication and a leading cause of death among patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).1 ACS is caused by vaso-occlusion in the pulmonary microvasculature and leads to a vicious cycle of hemoglobin S deoxygenation, sickling of erythrocytes, hemolysis, endothelial injury, further microvascular occlusion, and subsequent tissue ischemia.2 It can be triggered by multiple etiologies, including acute pain episodes, infection, pulmonary embolism or infarction, and fat embolism.3 Patients may experience chest pain, fever, dyspnea, or other respiratory symptoms.4,5 ACS can evolve rapidly to acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, multiorgan failure, and eventual death.4,5

The clinical presentation of ACS is highly variable, which makes it challenging to diagnose through medical history and physical examination alone. In one study, only 39% of diagnosed ACS cases were clinically suspected before imaging.6 Considering this variability and the high associated morbidity and mortality, all patients hospitalized with SCD are closely monitored for ACS. The current definition of ACS includes respiratory symptoms and/or fever along with a new pulmonary infiltrate involving at least one complete lung segment on chest radiography (CXR).7 In addition, patients with SCD frequently undergo repeat CXR 24 to 48 hours after admission because of the delayed nature of infiltrate appearance.4

Unfortunately, the current diagnostic model has high dependence on an imaging modality that necessitates exposing patients repeatedly to ionizing radiation. This is especially troubling for children, who may need to provide numerous chest radiographs and CT scans starting at an early age. With improved life expectancy over recent decades and more patients with SCD living into older adulthood,8 there may be cumulative toxicity from radiation exposure, such as the development of malignancies.9 Point-of-care ultrasound is emerging as a means to assist in rapid diagnosis and treatment planning in an increasing number of settings.10, 11, 12 Lung ultrasound (LUS) is safe, inexpensive, portable, and convenient, making it a promising diagnostic modality,13 particularly in low-resource settings. The first reported use of LUS to diagnose ACS was described in a case report by Stone in 2009,14 in which LUS identified a diffuse B-line pattern in the anterior fields bilaterally and consolidations in the posterior fields bilaterally, leading to an early diagnosis of ACS in a patient whose initial chest radiograph result was negative. The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to observe the diagnostic test accuracy of LUS for the diagnosis of ACS, using the current reference standard of CXR. We hypothesized that LUS has comparable sensitivity and specificity to CXR and can be used clinically for the diagnosis of ACS in SCD.

Study Design and Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed for this systematic review and meta-analysis.15 Given only publicly available data were sought and no human subjects were included, no institutional review board approval was obtained.

Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted on March 17, 2022, using the following databases: Embase, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. No date restrictions were used. The specific databases were selected on the basis of evidence-based recommendations published by Bramer and colleagues,16 which included using only the first 200 references sorted by Google Scholar relevance ranking. All the references from the other three database queries were retained. e-Table 1 includes details regarding the search terms used. Endnote 20 (Clarivate) was used to remove duplicates and to screen studies. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts for study inclusion. A third reviewer settled any disparities in deciding which studies to assess more thoroughly. The two reviewers then chose studies for meta-analysis following full-text review. Once again, the third reviewer settled differences or disparities in title/abstract screening and full-text review stages. The reference lists of the included studies were used to identify additional potential studies meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria not captured in the initial database search.

Inclusion Criteria

To be included in this systematic review and meta-analysis, studies must have provided data from patients with SCD of any genotype, have a sample size of at least five patients, and provided data on test characteristics of LUS compared with the reference standard of CXR for ACS (ie, provided the number of patients with true positive, false positive, false negative, and true negative results). Conference abstracts could be included if the time period of the study did not overlap with subsequent manuscript publication, to avoid duplication of patient data. Studies with no English language translation available were excluded. Review articles were also excluded.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers extracted the following data: clinical setting, study location, time period over which patients were included, research design, inclusion criteria, criteria for ACS diagnosis (reference standard), criteria for ACS diagnosis with LUS, mean/median age of patients, SD/range of ages of patients, proportion of sex, distribution of SCD genotypes, symptom presentation, percentage of patients with prior episode of ACS, and patients with true positive, false positive, false negative, and true negative LUS diagnoses compared with the reference standard of CXR.

Statistical Analysis

Meta-analysis was performed with the metadta and midas modules in the STATA statistical software program (STATA version 17.0; StataCorp). Metadta is a macro that employs a random effects model to generate a summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve, along with summary sensitivities and specificities.17 Individual study sensitivities and specificities were plotted on a forest plot, and interstudy heterogeneity statistics were observed. The midas module18 was used to verify SROC curve data from metadta and for additional statistical analysis and data visualization tools. A Fagan plot was used to apply the negative and positive likelihood ratios (LRs) to the pretest probability to calculate posttest probabilities. An LR scattergram (graphical representation of the distribution of individual studies’ LRs with a summary point) was also created.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

The QUADAS-2 tool was used independently by reviewers to evaluate the included studies for risk of bias and applicability to the research question.19 The QUADAS-2 tool contains four domains of bias assessment (patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing); three of these domains (patient selection, index test, and reference standard) were also analyzed for applicability. Cases of discrepancy were resolved by discussion.

A Deeks funnel plot was retrieved to assess for possibility of publication bias. Sensitivity analyses were conducted with removal of conference abstracts to ensure that these studies did not meaningfully change the results.

Results

A total of 713 unique studies were retrieved. Of these, 86 were included after title and abstract screening. A total of 80 of these studies were excluded after a full-text screen because of reasons provided in Figure 1, leaving six studies in the quantitative synthesis. No additional studies were identified through a manual search of the included studies’ reference lists.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart detailing study inclusion. ACS = acute chest syndrome; DTA = diagnostic test accuracy; LUS = lung ultrasound.

Study Characteristics

Data were available for 625 possible ACS cases and 95 confirmed ACS diagnoses (pretest probability of 15.2%). An overview of the included studies can be seen in Table 1. Daswani et al,20 Colla et al,21 Cohen et al,22 and Preto-Zamperlini et al23 are full-text manuscripts, whereas Cohen et al24 and Delestrain et al25 are conference abstracts. Four of the six studies were conducted in the United States, one in France, and one in Brazil. All six included studies were prospective observational studies. Of the studies with reported enrollment periods, studies began as early as August 201320 and finished as late as October 2018,23 but Delestrain et al25 did not report the enrollment period. Most studies enrolled primarily pediatric populations from EDs, with maximum included ages of either 18 or 21 years; however, Colla et al21 enrolled adult patients in a general ED. The median ages at enrollment ranged from 5 years in Daswani et al20 to between 33 and 41 years for Colla et al.21 Five of the six studies reported the proportion of female participants, ranging from 33% in Preto-Zamperlini et al23 to 65% in Colla et al.21 The average percentage of female patients from the studies in which it was reported was 41%.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies

| Study/Year | Clinical Setting | LUS Diagnostic Criteria | Median Age (y) | Presenting Symptoms | PMH of ACS, No. (%) | TP (No.) | FP (No.) | FN (No.) | TN (No.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen et al24/2015 | Two urban pediatric EDs (USA) | N/A | 7 | N/A | N/A | 12 | 4 | 2 | 80 |

| Daswani et al20/2016 | Urban pediatric ED (USA) |

|

5.7 | Fever (100%),a cough (52%), abdominal pain (19%), chest pain (16%), vomiting (13%), dyspnea (11%) | 61 (53%) | 13 | 6 | 2 | 95 |

| Colla et al21/2018 | ED (USA) |

|

+ACS: 41 –ACS: 33 |

Chest pain (50%), tachypnea (40%), tachycardia (20%) | 20 (100%) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 14 |

| Cohen et al22/2020 | Two urban pediatric EDs (USA) |

|

8 | URI (50%), cough (50%), nonchest pain (43%), chest pain (43%), abnormal lung examination (24%), vomiting (12%), SOB (8%), chills (3%), wheezing (2%) | 116 (61%) | 27 | 12 | 5 | 147 |

| Delestrain et al25/2021 | Four urban pediatric EDs (France) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 14 | 64 | 0 | 43 |

| Preto-Zamperlini et al23/2022 | Academic urban tertiary pediatric ED (Brazil) |

|

8 | Cough (67%), fever (58%), hypoxia (48%), tachypnea (34%), chest pain (30%), wheezing (4%) | 46 (58%) | 14 | 21 | 0 | 44 |

+ACS = positive ACS diagnosis from reference standard; –ACS = negative ACS diagnosis from reference standard; ACS = acute chest syndrome; FN = false negative; FP = false positive; LUS = lung ultrasound; N/A = not available; PMH = past medical history; SOB = shortness of breath; TN = true negative; TP = true positive; URI = upper respiratory infection.

Fever in last 24 h was an inclusion criterion for Daswani et al.20

Presenting symptoms are also listed in Table 1 in order of most to least prevalent. The two most common symptoms seen in patients were coughing and chest pain. Other reported symptoms found in multiple studies included nonchest pain, fever, vomiting, and other respiratory symptoms. Although the criteria for ACS diagnosis using CXR are universal, the standard diagnostic criteria for ACS, using LUS, were not clearly established. Most of the studies defined some combination of radiologic findings of new pulmonary consolidations, air bronchograms, B-lines, or pleural effusions on LUS to be positive for a diagnosis of ACS (Table 1).

Reported interrater reliability in LUS interpretation ranged from a Cohen’s κ of 0.62 in Colla et al21 to 0.86 in Cohen et al.24 Within the range, Cohen’s κ for LUS interrater reliability was 0.65 in Preto-Zamperlini et al,23 0.67 in Cohen et al,22 0.77 in Daswani et al,20 and not reported in Delestrain et al.25 There was variability in the level of training of individuals conducting the LUS for each study. Pediatric emergency medicine physicians conducted them in Daswani et al20 and Preto-Zamperlini et al.23 In Colla et al,21 LUS was conducted by an emergency medicine physician credentialed in point-of-care ultrasound along with a trained undergraduate student under direct supervision. Medical students along with clinicians trained in LUS conducted the scans in Cohen et al,24 and experienced clinicians conducted them in Delestrain et al.25 Finally, Cohen et al22 had five different novice trainees in LUS with expert oversight from a physician with more than six years of ultrasound experience.

Overall Diagnostic Accuracy

The area under the curve (AUC) is 0.96 (95% CI, 0.94-0.97) with a summary sensitivity of 0.92 (95% CI, 0.68-0.98) and a summary specificity of 0.89 (95% CI, 0.69-0.97) (Figs 2 and 3). The summary positive LR was 8.4 (95% CI, 3.0-23.6), and the summary negative LR was 0.09 (95% CI, 0.02-0.38). The summary positive predictive value was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.81-0.95), and the summary negative predictive value was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.83-0.98). The cumulative diagnostic OR was 89 (95% CI, 32-244) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of study sensitivities and specificities of lung ultrasound for acute chest syndrome diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Summary receiver operating characteristic curve of lung ultrasound for acute chest syndrome diagnosis, using chest radiography as the reference standard. AUC = area under the curve; SENS = sensitivity; SPEC = specificity; SROC = summary receiver operating characteristic.

Table 2.

Summary of Diagnostic Test Accuracy of Lung Ultrasound for Acute Chest Syndrome Diagnosis, Using Chest Radiography as Reference Standard

| Sensitivity Analysis | Positive Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | Negative Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Diagnostic OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUS with conference abstracts | 8.4 (3.0-23.6) | 0.09 (0.02-0.38) | 0.88 (0.81-0.95) | 0.90 (0.83-0.98) | 0.92 (0.68-0.98) | 0.89 (0.69-0.97) | 89 (32-244) |

| LUS without conference abstracts | 10.8 (4.1-28.3) | 0.14 (0.04-0.52) | 0.90 (0.84-0.96) | 0.86 (0.81-0.92) | 0.87 (0.58-0.97) | 0.92 (0.77-0.97) | 78 (30-206) |

LUS = lung ultrasound; NPV = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value.

In a sensitivity analysis removing the abstract-only studies, the summary sensitivity was similar at 0.87 (95% CI, 0.58-0.97), and the summary specificity was similar at 0.92 (95% CI, 0.77-0.97). The AUC remained unchanged at 0.96 (95% CI, 0.94-0.97). In addition, the summary positive LR and the summary negative LR were slightly higher at 10.8 (95% CI, 4.1-28.3) and 0.14 (95% CI, 0.04-0.52), respectively. Finally, the summary positive predictive value and the summary negative predictive value were similar at 0.90 (95% CI, 0.84-0.96) and 0.86 (95% CI, 0.81-0.92), respectively. The cumulative diagnostic OR was slightly lower at 78 (95% CI, 30-206) (Table 2).

According to the midas STATA command, the between-study heterogeneity was I2 = 67.01% (95% CI, 38.40%-95.63%) for sensitivity and I2 = 97.36% (95% CI, 96.21%-98.50%) for specificity. Nonetheless, the generalized bivariate variability, a measure generated by the metadta STATA command, was low: I2 = 0.01%. The generalized bivariate variability is a synthesis of the variance in both logit sensitivity and specificity and integrates their inherent relationship.17 Using a bivariate box plot, we found data from Colla et al21 and Delestrain et al25 to be outside of the 95% CI for the median data (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Bivariate box plot to explore studies contributing to statistical heterogeneity. Points outside the 95% CI of the median distribution represent studies with outliers in the data.

An LR is the probability of having a clinical finding (either presence or absence) in those with a disease compared with in those without a disease and allows clinicians to reach a posttest probability from a pretest probability.26 Figure 5 displays a Fagan nomogram with the observed pretest probability of 15.2% for ACS in our included sample data; a positive LUS increases the posttest probability to 60% whereas a negative LUS reduces the posttest probability to 2%. The LR scattergram in Figure 6 provides the summary diagnostic data for LUS with a summary point in the left lower quadrant (positive LR < 10 and negative LR < 0.1).

Figure 5.

A Fagan nomogram with the observed pretest probability of 15.2% for acute chest syndrome in our included sample data. A positive lung ultrasound result increases the posttest probability to 60%, whereas a negative lung ultrasound result reduces the posttest probability to 2%. LR_Positive = positive likelihood ratio; LR_Negative = negative likelihood ratio; Post_Prob_Pos = posttest probability following positive test; Post_Prob_Neg = posttest probability following negative test.

Figure 6.

Likelihood ratio scattergram with summary likelihood ratio. This graph suggests that LUS is most reliable when used for exclusion of ACS, due to a negative likelihood ratio less than 0.1 and a positive likelihood ratio less than 10. The likelihood ratio thresholds are widely accepted for recommending tests for clinical use and are scientifically supported by Bayesian decision theory.27 LLQ = left lower quadrant; LRN = negative likelihood ratio; LRP = positive likelihood ratio; LUQ = left upper quadrant; RLQ = right lower quadrant; RUQ = right upper quadrant.

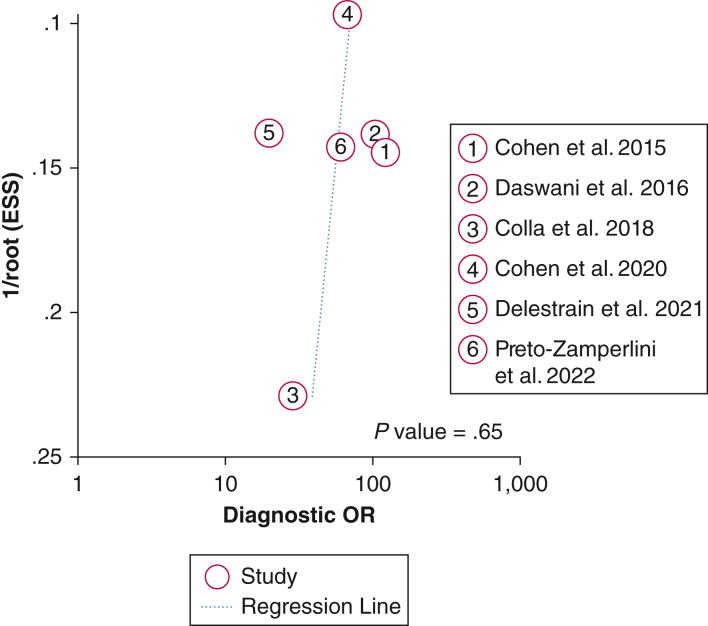

Assessment of Risk of Bias

We next aimed to evaluate the likelihood of publication bias given the small number of studies evaluated in this meta-analysis. A Deeks funnel plot asymmetry test was performed and demonstrated symmetry in the data, with P = .65, suggesting a low likelihood of publication bias (Fig 7).

Figure 7.

Deeks funnel plot with an overlaid regression line demonstrates symmetry in the data, with P = .65, suggesting a low likelihood of publication bias. ESS = effective sample size.

Figure 8 displays consensus risk of bias and applicability concern assessments for the included studies. Two studies had a low risk of bias in patient selection, whereas Cohen et al22 was assessed as having a high risk of bias given that they excluded patients who arrived at the ED with a recent chest radiograph produced elsewhere. This decision was thought to disproportionately exclude patients of higher acuity. All studies had low applicability concern for patient selection. For the index test, two studies were given unclear risk of bias and unclear applicability concerns because of limited detail provided in the conference abstracts. The reference standard had low risk of bias and low applicability concern across all studies, given the longstanding use of CXR as the modality of choice in ACS diagnosis along with established standards for CXR interpretation. One-half of the studies had an unclear risk of bias in flow and timing due to inadequate detail provided to discern the difference in timing between LUS and CXR.

Figure 8.

Consensus QUADAS-2 risk of bias and applicability concern assessments for the included studies. Patient selection refers to whether there were systemic differences between the target population (all patients with sickle cell disease who present with symptoms concerning for acute chest syndrome) as compared with the included sample population. The index test for this study was lung ultrasound (LUS) and refers to how the LUSs were interpreted and whether the interpreters had knowledge of the chest radiography results. The reference standard for this study was chest radiography and refers to how the chest radiographs were interpreted and whether the interpreters had knowledge of the LUS results. Flow and timing refer to whether there was an appropriate time interval between the index test and reference standard (ie, within a few hours).

Discussion

In the first systematic review of ACS diagnosis, we investigated the accuracy of LUS in 625 cases of possible ACS, 97% of which were in patients 21 years of age or younger. Compared with the reference standard of CXR, we found that LUS provided reasonable sensitivity and specificity at 92% and 89%, respectively, with a positive LR of 8.4 and a negative LR of 0.09. Given the negative LR is less than 0.1 and the positive LR is not greater than 10,27 LUS may be used to exclude ACS but may not be adequate for independently confirming an ACS diagnosis. In addition, the AUC for the SROC curve is 0.96, indicating very good accuracy of this imaging modality.28 Overall, given the high sensitivity, low negative LR, and high AUC, LUS may be a valuable screening test for ACS, particularly in children, as a simple point-of-care test that avoids radiation exposure from CXR. Although the data suggest that LUS may be useful in ruling out ACS, it may not be as useful in providing a diagnosis of ACS. However, LUS results may provide a helpful early readout to guide further workup and to stratify management, such as pursuing conservative management with supportive care vs confirmatory imaging by CXR or CT scanning, empiric antibiotic coverage, and blood transfusion therapy. Last, given the potential severity and rapid progression of ACS, a sensitive test that can be deployed at the bedside is highly desirable for initial screening, and low false-positive rates should be acceptable.

Although few studies have compared the diagnostic usefulness of LUS vs CXR in patients with ACS, Preto-Zamperlini et al23 compared the initial LUS and CXR assessments with the final diagnosis of ACS by follow-up CXR and found the initial LUS to have a significantly higher sensitivity (100% vs 67%).23 This finding reaffirms the benefit of LUS as a highly sensitive initial screening test for ACS.

In addition, multiple studies have compared these two imaging modalities for pneumonia diagnosis. Although CXR is considered a standard diagnostic imaging modality for pneumonia, a meta-analysis by Ye et al29 found that LUS had much higher sensitivity, specificity, and AUC in an SROC curve (0.93, 0.72, and 0.901) compared with that of CXR (0.54, 0.57, and 0.590) using a reference standard of lung CT scan. Because the diagnosis of ACS also requires the detection of a new pulmonary infiltrate, the studies of pneumonia diagnosis with LUS further support our findings that LUS can be helpful in the workup of ACS. In addition, LUS is portable and inexpensive, making it a useful imaging modality in both high-resource and low-resource settings.

In the only study, to our knowledge, comparing admission LUS and CXR directly with lung CT scanning in patients with ACS, Razazi et al30 evaluated and scored the ability of LUS and CXR to detect three different findings: consolidations, ground-glass opacities, and pleural effusions. The results showed that the reference standard CT scan findings were in closer agreement with initial LUS compared with CXR. The sensitivity of LUS was higher than that of CXR, whereas the specificity was high for both imaging modalities. In addition, prognostic value was observed with LUS; patients with an “LUS score” above the median of 11 had a larger volume of transfused and exsanguinated blood, greater oxygen requirements, more need for mechanical ventilation, and a longer ICU length of stay.30 The results of this study suggest that LUS might be used both diagnostically and prognostically during ACS episodes.

Broad familiarity with CXR and lack of experience and training in LUS in the point-of-care setting may be a barrier to uptake among providers. However, a study by Chiem et al31 found that after brief intervention, physicians who had not previously performed LUS were able to detect pulmonary abnormalities with a level of accuracy similar to that of physicians with prior experience with this imaging modality. The idea that lung ultrasound can be implemented in the clinical setting with short-term training and little concern for improper use or technique is further supported by our review, which found that individuals of varying levels of experience (including undergraduate and medical students) conducting the LUS still had strong agreement among the LUS raters. The Cohen’s κ is a useful value to consider in assessing interrater reliability. On the basis of Landis and Koch’s guidelines32 to interpreting Cohen’s κ, four of the studies were calculated to have a value that fell in the range of 0.61 to 0.80, signifying substantial agreement. One additional study was calculated to have a value of 0.86, which signified almost perfect strength of agreement according to the same guidelines.

The generalizability of the results of our meta-analysis is also important to consider. Although the isolated sensitivity and specificity I2 statistics suggest moderate to considerable heterogeneity, the generalized variability was low with an I2 close to zero. This bivariate I2 measure may be better suited for diagnostic test accuracy studies as it improves on the limitations of applying the traditional I2 statistic, which uses a normal-normal model designed for univariate meta-analysis, to binomial data sets.17 Regardless, all I2 values should be interpreted with caution in the context of this review as only six studies are included.33 From a bivariate box plot of the data, two studies with possible outlier data were identified. Data from Colla et al21 may have been outliers because this is the only study conducted in an adult population. In addition, as the Colla et al study21 included only patients with a known history of ACS, it had the highest pretest probability of ACS (30%). The Delestrain et al25 data could have contained outliers due to differences in ultrasound practices in France or other methodologic differences, although it is difficult to evaluate the details of this study, given that only data from the conference abstract are available.

The inclusion of conference abstracts in our review has both potential positive and negative impacts on the interpretation of our results. Certainly, including studies that have not undergone a more rigorous peer-review process could introduce more variability and decrease the rigor of our data. However, our sensitivity analysis excluding abstract-only studies yielded similar results, reinforcing the validity of our findings. Furthermore, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions recommends searching all relevant gray literature when conducting a review.34 Therefore, the inclusion of conference abstracts may enhance the comprehensiveness of our analysis and decrease the potential impact of publication bias.

Another limitation of this review is the small number of studies included in the final analysis. Given that there is currently a paucity of studies investigating LUS for the diagnosis of ACS, it may be warranted to conduct another review on this topic in the next 5 to 10 years as more data are gathered. It may be especially important and useful to reassess in the future as health care providers become more comfortable using LUS. As this imaging modality becomes more commonly implemented, there may be potential to improve the diagnostic accuracy and positive predictive value of the test. In addition, given that most of the studies included only patients coming to the ED, we are limited in our ability to apply these results to other settings, particularly to the inpatient setting where patients’ clinical status is often changing rapidly. This applicability concern also pertains to patient age, with nearly all patients being 21 years or younger. Although the existing studies show that LUS may be useful in screening for ACS in pediatric patients, further studies in the older adult SCD population are warranted.

Finally, there is currently no established set of sonographic findings for the diagnosis of ACS by LUS. Although a consolidation on CXR defines a positive study for the diagnosis of ACS, there was considerable variability between the six studies on the definition of positive LUS findings, requiring further investigation. Head-to-head comparison of LUS with CXR, using a reference standard of CT scanning, would be useful to determine whether this imaging modality could supplant CXR as a standard of care. Additional research is also needed to investigate the usefulness of LUS beyond the initial diagnosis of ACS, such as its prognostic value. The use of serial ultrasounds to monitor response to treatment and progression of disease should be explored as a safer, faster, and more cost-effective alternative to serial CXR.

Interpretation

The results of our meta-analysis demonstrate that LUS may be a valuable tool in the evaluation of ACS in patients with SCD because of the lack of radiation exposure, low cost, and ease of use, especially in pediatric populations. Our results show that LUS provided excellent sensitivity and good specificity, favoring the use of LUS as an initial screening tool for ACS. Continued research is warranted to determine the usefulness of LUS as a potential diagnostic, prognostic, and monitoring tool in the management of ACS in SCD.

Funding/Support

This project was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (Grant UL1-TR-001857), Grant RO1-HL154629 to E. M. N., and Grant 5KL2TR001856-07.

Financial/Nonfinancial Disclosures

The authors have reported to CHEST the following: J. Z. X. has served on an advisory committee for GlaxoSmithKline. None declared (M. O., A. R. J., I. K., E. M. N.).

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: All authors took part in the conception of the study, and all authors approved the manuscript for publication and agree to be accountable for the work’s integrity. M. O. conducted search queries. A. R. J. and I. K. undertook screenings of the articles and collected all data. A. R. J., I. K., and M. O. performed bias assessments of included articles. M. O. analyzed the data with support from the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute. M. O., A. R. J., and I. K. drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. E. M. N. and J. Z. X. provided mentorship and guidance throughout the conduct of this work.

Role ofsponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Table is available online under “Supplementary Data.”

Footnotes

Drs Omar and Jabir contributed equally to this manuscript.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Castro O., Brambilla D.J., Thorington B., et al. The acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease: incidence and risk factors. Blood. 1994;84(2):643–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melton C.W., Haynes J., Jr. Sickle acute lung injury: role of prevention and early aggressive intervention strategies on outcome. Clin Chest Med. 2006;27(3):487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballas S.K., Lieff S., Benjamin L.J., et al. Definitions of the phenotypic manifestations of sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(1):6–13. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vichinsky E.P., Neumayr L.D., Earles A.N., et al. National Acute Chest Syndrome Study Group. Causes and outcomes of the acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1855–1865. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novelli E.M., Gladwin M.T. Crises in sickle cell disease. Chest. 2016;149(4):1082–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris C., Vichinsky E., Styles L. Clinician assessment for acute chest syndrome in febrile patients with sickle cell disease: is it accurate enough? Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34(1):64–69. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yawn B.P., Buchanan G.R., Afenyi-Annan A.N., et al. Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA. 2014;312(10):1033–1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamideh D., Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(9):1482–1486. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunson A., Keegan T.H.M., Bang H., Mahajan A., Paulukonis S., Wun T. Increased risk of leukemia among sickle cell disease patients in California. Blood. 2017;130(13):1597–1599. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-783233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mojoli F., Bouhemad B., Mongodi S., Lichtenstein D. Lung ultrasound for critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(6):701–714. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201802-0236CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitson M.R., Mayo P.H. Ultrasonography in the emergency department. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):227. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1399-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhagra A., Tierney D.M., Sekiguchi H., Soni N.J. Point-of-care ultrasonography for primary care physicians and general internists. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(12):1811–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amatya Y., Rupp J., Russell F.M., Saunders J., Bales B., House D.R. Diagnostic use of lung ultrasound compared to chest radiograph for suspected pneumonia in a resource-limited setting. Int J Emerg Med. 2018;11(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12245-018-0170-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone M.B. Acute chest syndrome diagnosed by lung sonography. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(4):516.e5–516.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bramer W.M., Rethlefsen M.L., Kleijnen J., Franco O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):245. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0644-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyaga V.N., Arbyn M. Metadta: a Stata command for meta-analysis and meta-regression of diagnostic test accuracy data—a tutorial. Arch Public Health. 2022;80(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00747-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dwamena B., MIDAS: Stata module for meta-analytical integration of diagnostic test accuracy studies Statistical Software Components S456880, Boston College Department of Economics. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456880.html Updated February 5, 2009.

- 19.Whiting P.F., Rutjes A.W., Westwood M.E., et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daswani D.D., Shah V.P., Avner J.R., Manwani D.G., Kurian J., Rabiner J.E. Accuracy of point-of-care lung ultrasonography for diagnosis of acute chest syndrome in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease and fever. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(8):932–940. doi: 10.1111/acem.13002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colla J.S., Kotini-Shah P., Soppet S., et al. Bedside ultrasound as a predictive tool for acute chest syndrome in sickle cell patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(10):1855–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen S.G., Malik Z.M., Friedman S., et al. Utility of point-of-care lung ultrasonography for evaluating acute chest syndrome in young patients with sickle cell disease. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(3s):S46–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preto-Zamperlini M., Giorno E.P.C., Bou Ghosn D.S.N., et al. Point-of-care lung ultrasound is more reliable than chest X-ray for ruling out acute chest syndrome in sickle cell pediatric patients: a prospective study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69(5) doi: 10.1002/pbc.29283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen S.G., Malik Z.M., Hagbom R., et al. Utility of lung ultrasound for evaluating acute chest syndrome in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease [conference abstract] Blood. 2015;126(23):980. https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/126/23/980/136295/Utility-of-Lung-Ultrasound-for-Evaluating-Acute [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delestrain C., El Jurdi H., Guitton C., et al. Late breaking abstract—usefulness of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis and early detection of acute chest syndrome in children with sickle cell disease [conference abstract] Eur Respir J. 2021;58(suppl 65):PA3547. doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2021.PA3547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGee S. Simplifying likelihood ratios. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(8):646–649. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stengel D., Bauwens K., Sehouli J., Ekkernkamp A., Porzsolt F. A likelihood ratio approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic studies. J Med Screen. 2003;10(1):47–51. doi: 10.1258/096914103321610806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones C.M., Athanasiou T. Summary receiver operating characteristic curve analysis techniques in the evaluation of diagnostic tests. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(1):16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye X., Xiao H., Chen B., Zhang S. Accuracy of lung ultrasonography versus chest radiography for the diagnosis of adult community-acquired pneumonia: review of the literature and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Razazi K., Deux J.F., de Prost N., et al. Bedside lung ultrasound during acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(7) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiem A.T., Chan C.H., Ander D.S., Kobylivker A.N., Manson W.C. Comparison of expert and novice sonographers’ performance in focused lung ultrasonography in dyspnea (FLUID) to diagnose patients with acute heart failure syndrome. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(5):564–573. doi: 10.1111/acem.12651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landis J.R., Koch G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Hippel P.T. The heterogeneity statistic I2 can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:35. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins J.P.T., Thomas J., Chandler J., et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane; 2022. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook version 6.3. Updated February 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.