Abstract

Introduction:

The present systematic review and meta-analysis aims to conduct a comprehensive and complete search of electronic resources to investigate the role of administrating Chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) in improving complications following Spinal Cord Injuries (SCI).

Methods:

MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Sciences databases were searched until the end of 2019. Two independent reviewers assessed the studies conducted on rats and mice and summarized the data. Using the STATA 14.0 software, the findings were reported as pooled standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results:

A total of 34 preclinical studies were included. ChABC administration improves locomotion recovery after SCI (SMD=0.90; 95% CI: 0.61 to 1.20; P<0.001). The subgroup analysis showed that the differences in the SCI model (P=0.732), the severity of the injury (P=0.821), the number of ChABC administrations (P=0.092), the blinding status (P=0.294), the use of different locomotor score (P=0.567), and the follow-up duration (P=0.750) have no effect on the efficacy of ChABC treatment.

Conclusion:

The findings of the present study showed that prescribing ChABC has a moderate effect in improving locomotion after SCI in mice and rats. However, this moderate effect introduces ChABC as adjuvant therapy and not as primary therapy.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Chondroitinase ABC, Animal, Locomotion

Highlights

ChABC improves locomotion recovery after SCI.

ChABC can improves locomotion recovery in all severity of SCI.

The treatment can improve locomotion in all follow-up duration.

Plain Language Summary

The present review aims to conduct a comprehensive and complete search of electronic resources to investigate the role of administrating Chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) in improving complications following Spinal Cord Injuries (SCI). We searched the databases and two independent reviewers assessed the studies conducted on rats and mice and summarized the data. A total of 34 preclinical studies were included. Our results showed that ChABC administration improves locomotion recovery after SCI. In addition, analysis showed that the differences in the mechanism of spinal cord injury, the severity of the injury, the number of ChABC administrations, the blinding status of observer, the use of different locomotor score, and the follow-up duration have no effect on the efficacy of ChABC treatment. As a conclusion, the findings of the present study showed that prescribing ChABC has a moderate effect in improving locomotion after SCI in mice and rats. However, this moderate effect introduces ChABC as adjuvant therapy and not as primary therapy.

1. Introduction

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) is one of the most important traumas in adulthood, leading to long-term and probably permanent disabilities in patients. This type of injury is seen at all ages and in both genders (White & Black, 2016; Yousefifard, et al., 2016). However, there is no definite cure to resolve all the symptoms of this disease. Thus, several treatment strategies have been proposed in recent years. These strategies range from pharmacological to cellular and molecular therapies, having often moderate efficacies, and none can entirely resolve the symptoms of SCI (Hosseini et al., 2014; Hosseini, Yousefifard, Aziznejad, & Nasirinezhad, 2015; Hosseini et al., 2016; Mojaradet al., 2016; Nasirinezhad, Hosseini et al., 2016; Arash Sarveazad et al., 2016; Yousefifard, Nasirinezhad et al., 2016; Yousefifard et al., 2016). The cause of this failure in treatment can be attributed to the pathophysiology and factors associated with SCI, which decrease the efficacy of the treatments. These factors include decreased growth mediators (Lu et al., 2012), poor ability of the nervous tissue to repair spontaneously (Finnerup & Baastrup, 2012), myelin-associated outgrowth inhibitors (Filbin, 2003; Simonen et al., 2003), and inhibitory factors related to glial scars, such as the up-regulation of Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycans (CSPGs) (Silver & Miller, 2004; Yuan & He, 2013). Therefore, if these inhibitory factors are eliminated, acceptable treatment for SCI may be achieved.

Research has demonstrated that among the mentioned factors, the formation of glial scars and chronic inflammation is probably the most important factor in reducing the efficacy of treatment (Muramoto et al., 2013; Yuan & He, 2013). Glial scar, the most important component of which is the CSPGs, leads to the activation of pathways that inhibit tissue repair in the central nervous system. These proteoglycans are extracellular matrix molecules whose expression begins one day after the injury at the lesion site and reaches its maximum level a week later (Jones, Margolis, & Tuszynski, 2003). CSPGs stimulate cascading pathways leading to the activation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3β (GSK3β), which is a key factor in inhibiting the repair of the central nervous system tissues and axons (Dill et al., 2008). In recent years, studies have shown that the digestion of CSPGs using the bacterial enzyme chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) can promote axonal growth and ultimately improve sensory-motor function following SCI (Dyck et al., 2015; Shinozaki et al., 2016); however, in some studies, ChABC has had a moderate effect or was ineffective in the recovery process following SCI (Alluin et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2013; Zhao & Fawcett, 2013).

Although several studies have been conducted in recent years to investigate the efficacy of ChABC to treat SCI, inconsistencies in these studies have been an obstacle to drawing a possible conclusion. One way to achieve an overall result is to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis; however, no meta-analyses have been performed yet. Therefore, the present systematic review and meta-analysis aims to conduct a comprehensive and complete search of electronic resources to investigate the role of administrating ChABC in improving the complications following SCI.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design

To achieve the purpose of the present study, the PICO framework was defined as follows: Problem (P): animals (rats or mice) with traumatic SCI; Intervention (I): intravenous or intracranial administration of ChABC; Comparison (C): comparison with non-treated SCI group or vehicle-treated group; Outcome (O): locomotion assessment of the animals using appropriate tests, including the Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan (BBB) test, the grid walking test, the pellets retrieved test, and the ladder walking test. BBB is the most common test to assess motor function which is performed by capturing animals' free movement on a circular field (open field walking test) for 4 min on a film, and each animal is blindly scored by 2 trained observers watching the film. The scoring is based on a 21-point scoring scale, categorizing recovery patterns into early (0 to 7), intermediate (8 to 13), and late phases (14 to 21) of recovery. The mean score for each animal is considered its BBB score (Basso et al., 1995). The grid walking test is another examination that is performed on a grid runway (27 cm×180 cm), with 50×50 mm holes, and after training, the average number of limb placement errors in every run is calculated for each animal (Kunkel-Bagden et al., 1993). In the pellets retrieved test, the animals were trained to reach food pellets through a 1.5 cm slot in an acrylic box (15 cm×36 cm×30 cm), and the number of pellets successfully retrieved out of 20 offered pellets will be calculated as the success rate (Montoya et al., 1991). In the ladder walking test, animals' walk on a 120-cm-long horizontal ladder with unevenly spaced bars is captured, and each step of each forepaw is given a score according to a 0–6 scoring system (0=total miss, 1=deep slip, 2=slight slip, 3=replacement, 4=correction, 5=partial placement, and 6=correct placement). The average score of each step for 3 rounds is calculated as the final score (Metz & Whishaw, 2009).

Selection criteria

Studies on rats and mice that assessed the role of ChABC in SCI were included. The exclusion criteria were as follows: combination therapy, follow-up of fewer than 4 weeks, lack of non-treated SCI group, lack of locomotion assessments, studies performed on non-rodent species, and review studies. Since locomotion recovery in animal models requires at least 4 weeks of follow-up, studies with a follow-up period of fewer than 4 weeks were excluded as well.

Search strategy

The search was conducted using keywords related to SCI and ChABC. MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science electronic databases were searched until the end of 2019. The Embase database search query was as follows:

‘chondroitin abc lyase’/exp OR ‘chondroitin abc eliminase’:ab,ti OR ‘chondroitin abc endolyase’:ab,ti OR ‘chondroitin abc lyase’:ab,ti OR ‘chondroitin sulfate abc endolyase’:ab,ti OR ‘chondroitin sulphate abc endolyase’:ab,ti OR ‘chondroitinase abc’:ab,ti OR ‘chondroitinases and chondroitin lyases’:ab,ti OR ‘condoliase’:ab,ti OR ‘anti-CSPG’:ab,ti OR ‘CSPGs’:ab,ti OR ‘Chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans’:ab,ti OR ‘chondroitinase’:ab,ti OR ‘Chondroitin Sulfate ABC Endolyas’:ab,ti

‘spinal cord injury’/exp OR ‘spinal cord contusion’/exp OR ‘spinal cord hemisection’/exp OR ‘spinal cord transection’/exp OR ‘cervical spine injury’/exp OR ‘Spinal compression’:ab,ti OR ‘spinal cord trauma’:ab,ti OR ‘trauma, spinal cord’:ab,ti OR ‘injured spinal cord’:ab,ti OR ‘spinal cord injured’:ab,ti OR ‘spinal cord injuries’:ab,ti OR ‘nerve transection’ #1 AND #2

To find additional articles, a manual search was done from the list of relevant articles and related journals. In addition, grey literature was explored by adopting 3 search strategies, namely ProQuest's dissertation section, contacting the authors of related articles to obtain unpublished or pre-printed data, and using Google and Google Scholar search engines.

Data extraction

The articles obtained from the systematic and manual search in the present study were integrated using End-Note software (v. X7, Thomson Reuters, 2014) and duplicate articles were removed. Two independent reviewers studied the titles and abstracts of the initial screening articles. Afterward, the full texts of the potentially related articles were assessed. Disagreements were resolved using a discussion with a third researcher.

The extracted data included the first author's name, year of publication, animal species, gender, age/weight of the animal, number of samples examined, SCI induction model, the severity of the injury, the time interval between SCI and ChABC prescription, ChABC treatment protocol, the duration of follow-up, and animal's locomotion status on the last day of the follow-up. As in some cases, there was an article comparing several treatment protocols of ChABC, the data in these articles were recorded as separate experiments and entered into the analysis. Also, most animal studies present their findings in the form of diagrams. To overcome this limitation, the method of extracting data from charts was performed using Sistrom and Mergo with the help of the Plot Digitizer software (Sistrom & Mergo, 2000).

Risk of bias assessment

The quality of the included studies was investigated using the proposed guidelines of Hassannejad et al. (Hassannejad et al., 2016). Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third researcher.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in the STATA 14.0 statistical program. To evaluate the efficacy of ChABC, the mean locomotion score of animals was compared between ChABC-treated groups and non-treated animals. The findings were pooled together and a Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) was reported. The heterogeneity between the studies was investigated using the I2 index, and since an obvious heterogeneity between the studies was observed, we used the random effect model. The Egger test and Funnel Plot were used to evaluate publication bias (Egger, Smith et al., 1997).

3. Results

Study characteristics

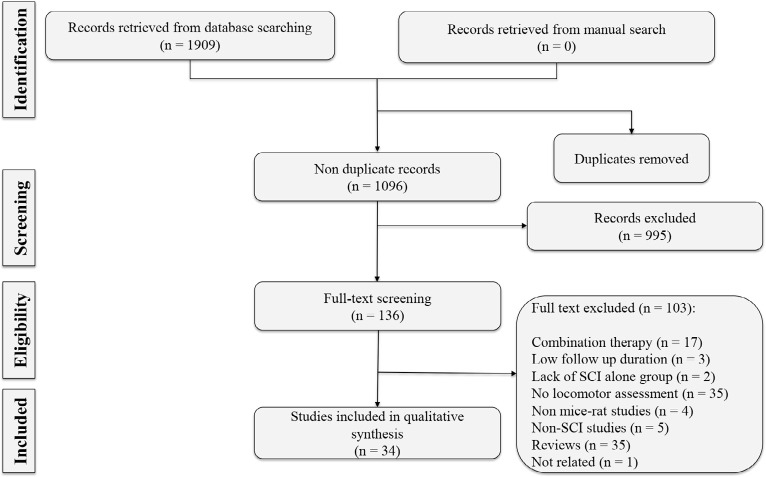

The search resulted in 1,096 non-duplicate articles. After studying the titles and abstracts of these articles, 136 articles were regarded as potentially eligible to enter this review, and finally, 34 articles were included (Bai et al., 2010; Bradbury et al., 2002; Caggiano et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2015; Führmann et al., 2018; García-Alías et al., 2009; García-Alías et al., 2008; García-Alías et al., 2011; Grosso et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2006; Ishikawa et al., 2015; Janzadeh et al., 2017; Karimi-Abdolrezaee et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2012; Liu, et al., 2018; Mountney et al., 2013; Ni et al., 2015; Novotna et al., 2018; Raspa, Bolla et al., 2019; Sarveazad et al., 2017; Sarveazad et al., 2014; Shinozaki et al., 2016; Takeuchi et al., 2013; Tom et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011a; Wang et al., 2011b; Xia et al., 2017; Xia et al., 2015; Xiong et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2009; Yoo et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2013) (Figure 1). These 34 studies contained 44 separate experiments evaluating several different protocols, including variations in the SCI severity, the prescription method, the prescription dose, and the interval time between SCI and ChABC administration. Three experiments were performed on mice and 41 experiments were performed on rats. In these studies, 272 animals were in the non-treated SCI group and 340 animals were in the ChABC-treated SCI group. Eleven studies performed cervical SCI, 31 studies thoracic SCI, and 2 studies thoracolumbar SCI. Ten experiments used the contusion injury model, and 10 experiments used the transaction model. Compression, crash, and hemisection models were adopted in 8 experiments. The severity of SCI was moderate in 20 studies and severe in 24 studies. ChABC was administrated immediately after SCI in 33 experiments (ranging between 0 and 42 days). A total of 17 experiments used a single dose of ChABC, while 27 experiments used multiple or continuous doses of ChABC (using subcutaneous pumps). In multi-dose protocols, the number of doses varied between 2 and 14. The place of administration was intrathecal in 25 experiments and intraspinal in 19. The total dose received ranged from 0.024 U to 560 U, indicating a range from very low doses to very high doses. A total of 28 experiments followed the observer blinding principle. Moreover, the follow-up duration ranged from 4 to 15 weeks (maximum frequency=42 weeks). The most common locomotion test was BBB (32 experiments). Table 1 demonstrates the characteristics of the articles, separately.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selecting the included papers

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author/Year | Gender; Spices; Strain; Weight | Sample Size SCI/Treated | Injury Location | Injury Model | Injury Severity | Antibiotic | Injury to ChABC Injection (Day) | Duration Of Injection (Day) | Location of Injection | Total Dose | FU | Name of Locomotion Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai et al., 2010 | F; Wistar; rat; 220–240 | 8/8 | T10 | Transection | Severe | Yes | 0 | 1 | IS | 0.025 | 84 | BBB |

| Bradbury et al., 2002 | M; Wistar; rat; none | 9/5 | C4 | Crush | Severe | No | 0 | 10 | IT | 0.6 | 42 | Grid walking |

| Caggiano et al., 2005 | F; Long-Evans; rat; none | 10/34 | T9–T10 | Crush | Moderate; severe | No | 0 | 14 | IT | 0.84 | 80 | BBB |

| Cheng et al., 2015 | F; SD; rat; 200–250 | 10/26 | T8 | Transection | Severe | Yes | 0; 14 | 1; 14 | IT; IS | 14; 50; 70; 100 | 70 | BBB |

| Führmann et al., 2018 | F; SD; rat; 300 | 9/9 | T1–T2 | Compression | Moderate | Yes | 7 | 1 | IS | 0.3 | 56 | BBB |

| García-Alías et al., 2008 | M; Lister Hooded; rat; 250–300 | 6/10 | C4 | Contusion | Moderate | No | 0 | 3 | IS; IT | 1.7 | 42 | Pellets retrieved |

| García-Alías et al., 2009 | M; Lister Hooded; rat; 250–300 | 6/24 | C4 | Crush | Moderate | No | 0; 2; 4; 7 | 3 | IS | 1.7; 10.8 | 42 | Pellets retrieved |

| García-Alías et al., 2011 | F; Sprague Dawley; rat; 200 | 9/10 | T8 | Transection | Severe | No | 0 | 1 | IT | 0.2 | 42 | BBB |

| Grosso et al., 2014 | F; SD; rat; 250–300 | 10/10 | T8 | Hemisection | Severe | Yes | 7 | 1 | IS | 0.06 | 42 | Grid walking |

| Huang et al., 2006 | F; SD; rat; 250–300 | 4/4 | T8–T9 | Transection | Severe | Yes | 14 | 8 | IT | 0.096; 0.48 | 56 | BBB |

| Ishikawa et al., 2015 | F; SD; rat; 200–230 | 5/5 | C3–C4 | Hemisection | Severe | No | 0 | 14 | IT | 0.84 | 42 | Pellets retrieved |

| Janzadeh et al., 2017 | M; Wistar; rat; 150–170 | 8/6 | T13–L1 | Compression | Moderate | Yes | 0 | 1 | IS | 1 | 28 | BBB |

| Karimi-Abdolrezaee et al., 2010 | F; Wistar; rat; 250 | 13/13 | T6–T8 | Compression | Moderate | Yes | 42 | 7 | IT | 0.42 | 105 | BBB |

| Kim et al., 2006 | F; Sprague Dawley; rat; 200–250 | 5/5 | C4 | Hemisection | Severe | No | 0 | 4 | IT | 0.8 | 49 | Grid walking |

| Lee et al., 2012 | F; C57BL/6; mice | 7/7 | T10–T11 | Compression | Moderate | No | 21 | 1 | IS | 0.06 | 105 | BBB |

| Liu et al., 2018 | M; Wistar; rat; 150–170 | 8/8 | T13–L1 | Compression | Severe | No | 7 | 1 | IS | 1 | 28 | BBB |

| Mountney et al., 2013 | F; Sprague Dawley; rat; 250–275 | 12/10 | T9 | Contusion | Moderate | No | 0 | 12 | IT | 0.436 | 35 | BBB |

| Ni et al., 2015 | F; Wistar; rat; 200–230 | 6/6 | T7–T9 | Hemisection | Severe | Yes | 0 | 10 | IT | 85 | 28 | BBB |

| Novotna et al., 2011 | M; Wistar; rat; 290–320 | 16/16 | T8–9 | Compression | Moderate | No | 2 | 3 | IT | 0.048 | 28 | BBB |

| Pan et al., 2018 | F; Wistar; rat; 250+20 | 8/12 | T10 | Transection | Severe | Yes | 0 | 1 | IT | 0.06 | 84 | BBB |

| Raspa et al., 2019 | NR; SD; rat; 250–275 | 5/5 | T9–T10 | Contusion | Moderate | Yes | 28 | 1 | IT | 0.036 | 42 | BBB |

| Sarveazad et al., 2014 | M; Wistar; rat; 250–350 | 6/6 | T8–T9 | Contusion | Moderate | Yes | 7 | 1 | IS | 1 | 63 | BBB |

| Sarveazad et al., 2017 | M; Wistar; rat; 200–250 | 6/6 | T8–9 | Contusion | Moderate | Yes | 7 | 1 | IS | 1 | 63 | BBB |

| Shinozaki et al., 2016 | F; SD; rat; 200–220 | 9/7 | T10 | Contusion | Severe | Yes | 42 | 7 | IT | 33.6 | 98 | BBB |

| Takeuchi et al., 2013 | M; C57BL/6J; mice; 8–10 weeks | 9/9 | T10 | Contusion | Moderate | No | 0 | 14 | IS | 560 | 58 | BBB |

| Tom et al., 2009 | F; SD; rat; 225–250 | 7/8 | C5 | Hemisection | Severe | Yes | 0 | 1 | IS | 0.125 | 35 | Grid walking |

| Wang et al., 2011a | F; SD; rat; 220–280 | 4/4 | T9–10 | Contusion | Severe | Yes | 0 | 2 | IS | 0.12 | 30 | BBB |

| Wang et al., 2011b | M; Lister hooded; rat; 150–200 | 13/10 | C4 | Hemisection | Severe | No | 28 | 5 | IT | 1.7 | 98 | Ladder walking |

| Xia et al., 2015 | F; SD; rat; 250–300 | 6/6 | T9–T10 | Hemisection | Severe | No | 0 | 14 | IT | 0.84 | 56 | BBB |

| Xia et al., 2017 | F; Wistar; rat; 200–230 | 6/6 | T7–T9 | Hemisection | Severe | Yes | 0 | 8 | IT | 0.48 | 28 | BBB |

| Xiong et al., 2016 | F; No; rat; 200±20 | 8/8 | T10 | Transection | Severe | No | 0 | 4 | IT | 0.024 | 28 | BBB |

| Yang et al., 2009 | M and F; SD; rat; 180–250 | 6/6 | T9 | Compression | Moderate | Yes | 0 | 6 | IT | 0.036 | 56 | BBB |

| Yoo et al., 2013 | F; C57BL/6; mice; 8 weeks | 6/9 | T7–T9 | Compression | Moderate | No | 0 | 1 | IS | 0.03 | 63 | BBB |

| Zhao et al., 2013 | M; Lister hooded; rat; 150–200 | 18/22 | C4 | Crush | Severe | No | 21 | 6 | IS | 1.7 | 84 | Ladder walking |

Abbreviations: F, female; FU, follow up duration; M, male; SD, Sprague-Dawley; IT, intrathecal; IS, intra-spinal; ChABC, Chondroitinase ABC.

Quality assessment and publication bias

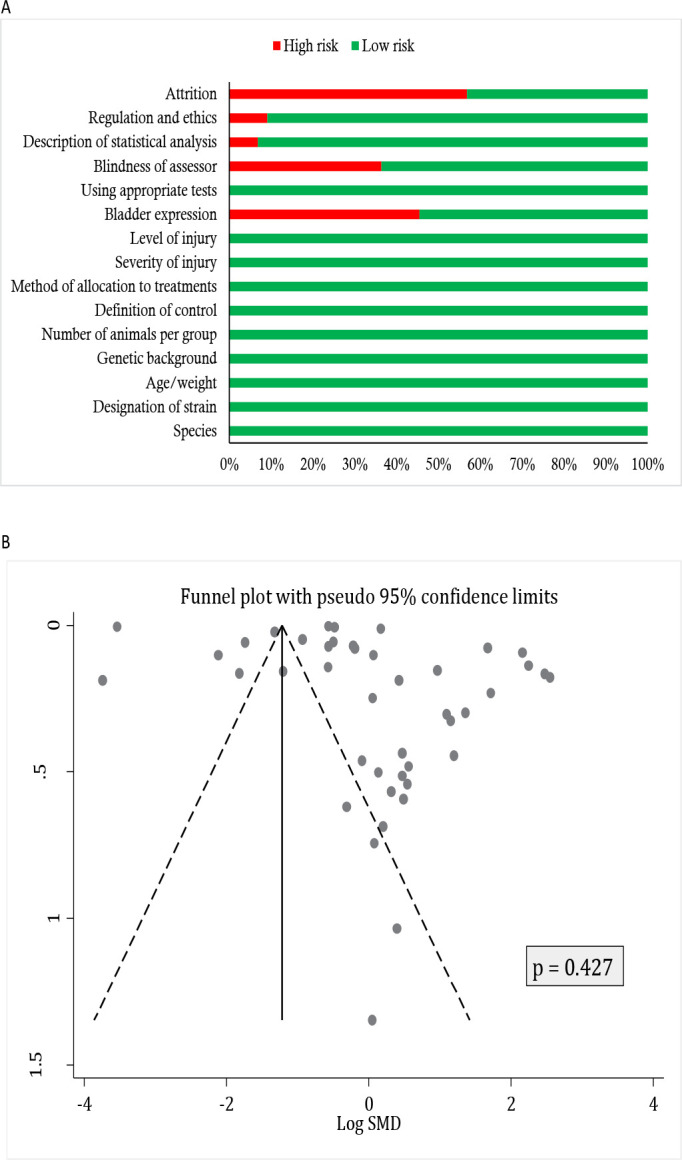

Risk of bias in bladder expansion, attrition, blinding of the observer, regulation, and ethics, and description of statistical analysis were high risk in 45.45%, 56.81%, 36.36%, 9.09%, and 6.81% of the studies, respectively. The risk of bias in other items was low. Figure 2 and Table 2 show the findings of this section. In the present study, no publication bias was observed (P=0.427) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A: Risk of bias assessment and B: Funnel plot for the assessment of publication bias across studies

There is no evidence for publication bias (P=0.380). SMD: Standardized Mean Difference.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment in studies

| Author/Year | Items | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| Bai et al., 2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Bradbury et al., 2002 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | --- |

| Caggiano et al., 2005 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cheng et al., 2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Führmann et al., 2018 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| García-Alías et al., 2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| García-Alías et al., 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| García-Alías et al., 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Grosso et al., 2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Huang et al., 2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- |

| Ishikawa et al., 2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | --- |

| Janzadeh et al., 2017 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Karimi-Abdolrezaee et al., 2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kim et al., 2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Lee et al., 2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | --- |

| Liu et al., 2018 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Mountney et al., 2013 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Ni et al., 2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Novotna et al., 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Pan et al., 2018 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Raspa et al., 2019 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Sarveazad et al., 2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sarveazad et al., 2017 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Shinozaki et al., 2016 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Takeuchi et al., 2013 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Tom et al., 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Wang et al., 2011a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Wang et al., 2011b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Xia et al., 2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

| Xia et al., 2017 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Xiong et al., 2016 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ |

| Yang et al., 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Yoo et al., 2013 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- |

| Zhao et al., 2013 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | --- | ✓ | --- | ✓ | ✓ | --- |

Notes: ✓: Low risk; ---: High risk.

- 1) Species;

- 2) Designation of strain;

- 3) Age/weight;

- 4) Genetic background;

- 5) Number of animals per group;

- 6) Definition of control;

- 7) Method of allocation to treatments;

- 8) Severity of injury;

- 9) Level of injury;

- 10) Bladder expression;

- 11) Using appropriate tests;

- 12) Blindness of assessor;

- 13) Description of statistical analysis;

- 14) Regulation and ethics;

- 15) Description of the reasons to exclude animals from the experiment during the study (attrition).

Meta-analysis

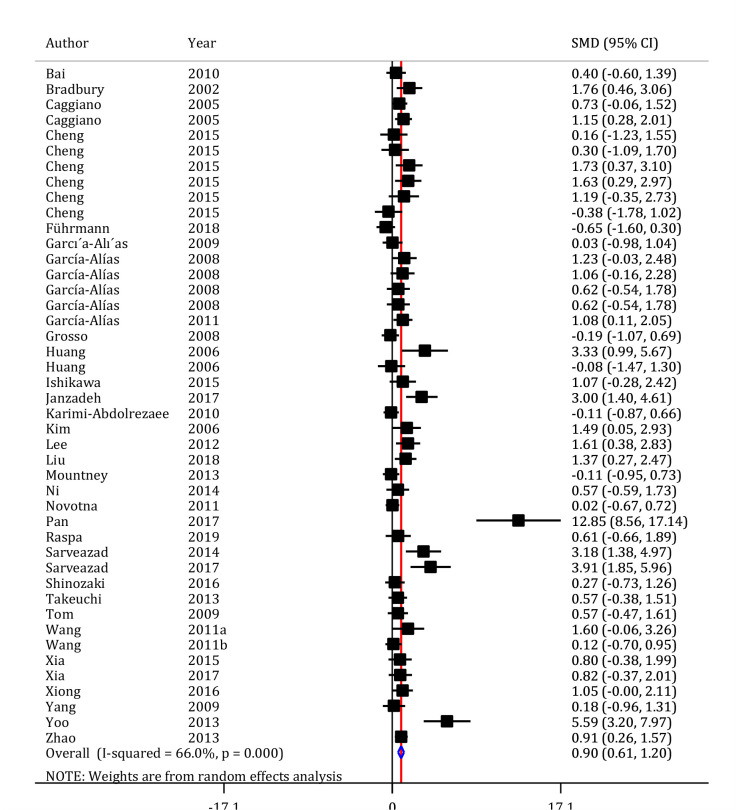

ChABC administration moderately improves locomotion recovery after SCI (SMD=0.90; 95% CI: 0.61 to 1.20; P <0.001) (Figure 3). The presence of heterogeneity between studies (I2=66%; P<0.001) led to performing subgroup analysis (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for the effects of chondroitinase ABC on locomotion recovery after spinal cord injury

The pooled analysis showed that the administration of Chondroitinase ABC can improve the locomotion of animals with injured spinal cord. Some of the included studies used several treatment protocols for Chondroitinase ABC; therefore, separate experiments from a study were included in the meta-analysis.

SMD: Standardized Mean Difference; CI: Confidence Interval.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of chondroitinase abc efficacy in improving locomotion after spinal cord injury

| Variables | Subgroups | Number of Experiments | SMD (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (P) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Rat | 41 | 0.83 (0.54 to 1.12) | 62.9% (<0.001) | <0.001 |

| Mice | 3 | 2.30 (0.11 to 4.49) | 86.6% (0.001) | 0.040 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.218 | ||||

| SCI model | Contusion | 10 | 0.85 (0.17 to 1.52) | 65.6% (0.002) | 0.014 |

| Compression | 8 | 1.07 (0.13 to 2.01) | 83.5% (<0.001) | 0.026 | |

| Crush | 8 | 0.96 (0.62 to 1.30) | 0.0% (0.900) | <0.001 | |

| Hemisection | 8 | 0.49 (0.11 to 0.87) | 0.0% (0.513) | 0.012 | |

| Transection | 10 | 1.40 (0.47 to 2.34) | 78.2% (<0.001) | 0.003 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.732 | ||||

| Injury location | Cervical | 11 | 0.75 (0.44 to 1.07) | 0.0% (0.533) | <0.001 |

| Thoracic | 31 | 0.96 (0.55 to 1.37) | 73.5% (<0.001) | <0.001 | |

| Thoracolumbar | 2 | 1.48 (0.65 to 2.30) | 0.0% (0.780) | <0.001 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.632 | ||||

| Severity of injury | Moderate | 20 | 0.900 (0.41 to 1.39) | 72.3% (<0.001) | <0.001 |

| Severe | 24 | 0.92 (0.55 to 1.29) | 59.1% (<0.001) | <0.001 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.821 | ||||

| Phase of treatment after spinal cord injury | Immediate-acute (0 to 4 days) | 26 | 0.96 (0.57 to 1.35) | 66.3% (<0.001) | <0.001 |

| Subacute (7 to 14 days) | 12 | 1.11 (0.35 to 1.87) | 74.2% (<0.001) | 0.004 | |

| Chronic (21 to 42 days) | 6 | 0.50 (0.03 to 0.97) | 38.0% (0.153) | 0.037 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.431 | ||||

| Number of Administrations | Single dose | 17 | 1.63 (0.87 to 2.39) | 82.4% (<0.001) | <0.001 |

| Multi dose | 27 | 0.58 (0.37 to 0.80) | 13.8% (0.261) | <0.001 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.092 | ||||

| Total administrated dose | Very low (<0.2 U) | 12 | 1.45 (0.58 to 2.32) | 82.9% (<0.001) | 0.001 |

| Low (0.2 to 1.7 U) | 19 | 0.88 (0.46 to 1.30) | 65.8% (<0.001) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate (10.8 to 14 U) | 5 | 0.75 (0.20 to 1.30) | 0.0% (0.813) | 0.007 | |

| High (33.6 to 560 U) | 8 | 0.68 (0.22 to 1.14) | 11.2% (0.343) | 0.004 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.488 | ||||

| Blinding of observer | No | 16 | 0.61 (0.36 to 0.86) | 0.0w% (0.776) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 28 | 1.12 (0.71 to 1.67) | 76.5% (<0.001) | <0.001 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.294 | ||||

| Test for locomotor assessment | BBB | 32 | 1.03 (0.63 to 1.44) | 72.7% (<0.001) | <0.001 |

| Other | 12 | 0.66 (0.33 to 0.98) | 14.7% (0.301) | <0.001 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.567 | ||||

| Follow-up duration | 4–7 weeks | 20 | 0.76 (0.45 to 1.08) | 35.8% (0.057) | <0.001 |

| 8–15 weeks | 24 | 1.06 (0.57 to 1.56) | 76.2% (<0.001) | <0.001 | |

| Overall significance among subgroups | 0.750 | ||||

BBB: Basso, Beattie and Bresnahan Scale; CI: Confidence Interval; SCI: Spinal Cord Injury; SMD: Standardized Mean Difference.

Subgroup analysis revealed that the animals' species does not affect the efficacy of ChABC treatment (P=0.218); however, a small number of experiments were performed on the mice subgroup (3 experiments) compared to the rat subgroup, and therefore, the analysis may not identify the differences between the subgroups. On the other hand, the location of the SCI had similarly no effect on the efficacy of ChABC treatment (P=0.632). However, in this analysis, only two experiments were performed on the thoracolumbar region. Thus, differences between the cervical, thoracic, and thoracolumbar injuries may not have been identified properly. Similar findings were observed regarding the phase of treatment. Analyses of subgroups discrepancies did not show any statistical differences between treatment in immediate-acute (26 experiments), subacute (12 experiments), and chronic (6 experiments) phases post-injury (P=0.431). The small number of experiments in chronic subgroups has resulted in the findings being uncertain. In addition to the above results, the difference between the total administered dose of ChABC did not affect the efficacy of ChABC treatment (P=0.488). Again, the small number of moderate and high dose experiments cast doubt over the adequacy of this analysis.

Regarding other factors, an acceptable number of experiments were entered in each subgroup. Therefore, with an acceptable confidence, it can be concluded that differences in the SCI model (P=0.732), the severity of the injury (P=0.821), the number of administrations (P=0.092), the blinding status (P=0.294), the use of different locomotor score (P=0.567), and the follow up duration (P=0.750) have no effect on the efficacy of ChABC treatment.

4. Discussion

The findings of the present study showed that prescribing ChABC has a moderate effect on the improvement of locomotion after SCI in rats and mice. The subgroup analysis showed that the efficacy of ChABC treatment is not affected by the differences in the SCI induction model, the severity of the injury, the number of ChABC administration, the blinding status, the use of different locomotor scores, and the follow-up duration.

The most important mechanism involved in improving motor function by prescribing ChABC after SCI is related to the restoration of neuronal plasticity in the spinal cord. SCI leads to the formation of a glial scar that is rich in CSPGs. Increased CSPGs after the central nervous system damage causes functional impairment both by preventing axonal regeneration and by preventing synaptic plasticity. The ChABC enzyme digests CSPGs, which, in addition to the axonal regeneration, by inducing axonal germination, restores lost circuits, neuronal plasticity, and ultimately functional changes (Hyatt et al., 2010; Massey et al., 2006; Vitellaro-Zuccarello et al., 1998). In 2011, via a systematic review, Kwon et el. demonstrated that ChABC promotes axonal regeneration in the spinal cord. Their results showed that the enzyme was less effective in cervical or thoracic injury models, but when used as adjuvant therapy in combination with cell therapy, its effects on improving motor functions were much greater (Kwon et al., 2011).

In the present meta-analysis, only studies that performed a follow-up of animals for at least 4 weeks were included. The reason for this choice was because it takes at least 4 weeks of follow-up to evaluate the effectiveness of a treatment for SCI models in rodents. Perhaps this is because the follow-up duration did not affect the efficacy of ChABC in improving locomotion. In other words, 4 weeks of follow-up was enough to see the effects of ChABC.

Using the single dose or multi-dose protocol did not affect the efficacy of ChABC treatment. Considering the course of motor improvement in animals with SCI in studies that have examined the effects of ChABC treatment on motor performance in rodents (Janzadeh et al., 2017; Sarveazad et al., 2017; Sarveazad et al., 2014), we observed that during the first week, without any intervention, the motor performance dramatically improves, and then, the speed of recovery decreases. As a result, it seems that the first week of SCI treatment in rodents is the most important period in terms of improving motor function and SCI management. The half-life of ChABC is 6 days (Lee et al., 2010). Since the use of the single dose or the multi-dose protocol did not affect the efficacy of ChABC treatment in the present study, it seems that the first dose of ChABC is the most important. Considering the half-life of ChABC, it can be concluded that this treatment is most effective in locomotion recovery during the first week following SCI. In other words, based on the half-life of the enzyme, if no prescriptions take place after the first dose, there is still enough amount of ChABC that can play a role in improving motor functions. The total dose received in most cases in single or multi-dose was similar. The prescribed dose in 76.5% of studies in the single dose group and 66.7% of studies in the multi-dose group was less than 1.7 U. Hence, there is still a need for further research to use different doses to become certain about the aforementioned conclusion.

Our results showed that prescribing ChABC has a moderate effect on the improvement of locomotion after SCI in rats and mice. Therefore, the combined application of ChABC and other therapeutic approaches may increase its effectiveness. For example, some studies used combinational therapy of ChABC along with stem cells, lasers, and various scaffolds (Novotna et al., 2020; Jevans et al., 2021; Raspa et al., 2021). These studies show that the effect of co-administration of ChABC with these therapies is more effective than single therapies. For example, Jevans et al. showed that co-administration of ChABC and neural stem cells had a greater effect on motor recovery compared to ChABC and cell therapy alone. Janzadeh et al. have reported similar findings in the simultaneous application of laser irradiation and ChABC administration (Janzadeh et al., 2020). Therefore, in future studies, more attention should be paid to the effects of combinational therapy on SCI.

As a result, it can be concluded that the addition of other therapies to the ChABC regimen may prove beneficial. For instance, studies point out that ChABC was administered along with stem cells, laser therapy, and different scaffolds. These studies demonstrate that the co-administration of ChABC with these treatments is more effective than single therapies. As an example, Jevans et al. showed that combination therapy of ChABC with neural stem cells has a greater effect on motor recovery following SCI than ChABC treatment alone (Jevans et al., 2021). Janzadeh et al. concluded the above-mentioned result as well (Janzadeh et al., 2020). Hence, future studies are suggested to contemplate the efficacy of combination therapies.

Another finding of the present study was that the efficacy of ChABC treatment in different severities of the injury is the same. The reason for this finding is that gliosis occurs in all severities of the lesion, and the administration of ChABC, via digesting the CSPGs, can play a role in the regeneration process. In addition, the severity of the damage in all models was in the moderate to severe range. The secondary mechanisms in both injury severities are almost identical, and this is another justification that the administration of ChABC is equally effective in both severities. Furthermore, the subgroup analysis on the effect of the phase of treatment, region of the injury, and the total administrated dose in ChABC efficacy were unreliable. The number of studies conducted on mice was small; therefore, reliable conclusions may not be supported desirably in this regard. In addition, the number of studies included in the efficacy of ChABC treatment in the chronic phase of SCI was low. Hence, it cannot be concluded whether ChABC administration in the chronic phase is different from its administration in immediate-acute and subacute phases.

Another limitation of the present study is the incomplete reporting bias in some studies. This is a common bias in animal studies and its assessment is difficult as there is no public registry for animal studies.

5. Conclusion

The findings of the present study showed that prescribing ChABC has a moderate effect on improving locomotion following SCI in mice and rats. The analyses showed that the efficacy of ChABC treatment is not affected by the differences in the SCI model, the severity of the injury, the number of administrations, the blinding status, the use of different locomotor scores, and the follow-up duration.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Code: 96-01-38-34312). The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

All expenses, charges, and costs, including software and hardware requirements in this research were supported by Sina Trauma and Surgery Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No: 96-01-38-34312).

Authors' contributions

Study design: Mostafa Hosseini, Mahmoud Yousefifard, Arash Sarveazad, Kosar Mohamed Ali; Data collection: Mahmoud Yousefifard, Atousa Janzadeh, Mohammad Hossein Vazirizadeh-Mahabadi; Data analysis: Mostafa Hosseini and Mahmoud Yousefifard; Drafting: Mahmoud Yousefifard; Critical Revision: All authors. First and second author have the same contribution.

Conflict of interest

All authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Alluin O., Delivet-Mongrain H., Gauthier M. K., Fehlings M. G., Rossignol S., Karimi-Abdolrezaee S. (2014). Examination of the combined effects of chondroitinase ABC, growth factors and locomotor training following compressive spinal cord injury on neuroanatomical plasticity and kinematics. PLoS One, 9(10), e111072. [PMID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F., Peng H., Etlinger J. D., Zeman R. J. (2010). Partial functional recovery after complete spinal cord transection by combined chondroitinase and clenbuterol treatment. Pflugers Archiv: European Journal of Physiology, 460(3), 657–666. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso D. M., Beattie M. S., Bresnahan J. C. (1995). A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. Journal of Neurotrauma, 12(1), 1–21. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury E. J., Moon L. D., Popat R. J., King V. R., Bennett G. S., Patel P. N., et al. (2002). Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature, 416(6881), 636–640. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano A. O., Zimber M. P., Ganguly A., Blight A. R., Gruskin E. A. (2005). Chondroitinase ABCI improves locomotion and bladder function following contusion injury of the rat spinal cord. Journal of Neurotrauma, 22(2), 226–239. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. H., Lin C. T., Lee M. J., Tsai M. J., Huang W. H., Huang M. C., et al. (2015). Local delivery of high-dose chondroitinase ABC in the Sub-acute stage promotes axonal outgrowth and functional recovery after complete spinal cord transection. PLoS One, 10(9), e0138705. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill J., Wang H., Zhou F., Li S. (2008). Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 promotes axonal growth and recovery in the CNS. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of The Society for Neuroscience, 28(36), 8914–8928. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck S. M., Alizadeh A., Santhosh K. T., Proulx E. H., Wu C. L., Karimi-Abdolrezaee S. (2015). Chondroitin Sulfate proteoglycans negatively modulate spinal cord neural precursor cells by signaling through LAR and RPTPσ and modulation of the Rho/ROCK pathway. Stem Cells (Dayton, Ohio), 33(8), 2550–2563. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filbin M. T. (2003). Myelin-associated inhibitors of axonal regeneration in the adult mammalian CNS. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 4(9), 703–713 [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup N. B., Baastrup C. (2012). Spinal cord injury pain: Mechanisms and management. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 16(3), 207–216. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Führmann T., Anandakumaran P. N., Payne S. L., Pakulska M. M., Varga B. V., Nagy A., et al. (2018). Combined delivery of chondroitinase ABC and human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neuroepithelial cells promote tissue repair in an animal model of spinal cord injury. Biomedical Materials (Bristol, England), 13(2), 024103. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Alías G., Barkhuysen S., Buckle M., Fawcett J. W. (2009). Chondroitinase ABC treatment opens a window of opportunity for task-specific rehabilitation. Nature Neuroscience, 12(9), 1145–1151. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Alías G., Lin R., Akrimi S. F., Story D., Bradbury E. J., Fawcett J. W. (2008). Therapeutic time window for the application of chondroitinase ABC after spinal cord injury. Experimental Neurology, 210(2), 331–338. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Alías G., Petrosyan H. A., Schnell L., Horner P. J., Bowers W. J., Mendell L. M., et al. (2011). Chondroitinase ABC combined with neurotrophin NT-3 secretion and NR2D expression promotes axonal plasticity and functional recovery in rats with lateral hemisection of the spinal cord. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 31(49), 17788–17799. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosso M. J., Matheus V., Clark M., van Rooijen N., Iannotti C. A., Steinmetz M. P. (2014). Effects of an immunomodulatory therapy and chondroitinase after spinal cord hemisection injury. Neurosurgery, 75(4), 461–471. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassannejad Z., Sharif-Alhoseini M., Shakouri-Motlagh A., Vahedi F., Zadegan S. A., Mokhatab M., et al. (2016). Potential variables affecting the quality of animal studies regarding pathophysiology of traumatic spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord, 54(8), 579–583. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini M., Karami Z., Janzadenh A., Jameie S. B., Haji Mashhadi Z., Yousefifard M., et al. (2014). The effect of intrathecal administration of muscimol on modulation of neuropathic pain symptoms resulting from spinal cord injury; an experimental study. Emergency, 2(4), 151–157. [PMID] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini M., Yousefifard M., Aziznejad H., Nasirinezhad F. (2015). The effect of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on allodynia and hyperalgesia in neuropathic animals: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation : Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 21(9), 1537–1544. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini M., Yousefifard M., Baikpour M., Rahimi-Movaghar V., Nasirinezhad F., Younesian S., et al. (2016). The efficacy of Schwann cell transplantation on motor function recovery after spinal cord injuries in animal models: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy, 78, 102–111. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. C., Kuo W. C., Cherng J. H., Hsu S. H., Chen P. R., Huang S. H., et al. (2006). Chondroitinase ABC promotes axonal regrowth and behavior recovery in spinal cord injury. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 349(3), 963–968. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt A. J., Wang D., Kwok J. C., Fawcett J. W., Martin K. R. (2010). Controlled release of chondroitinase ABC from fibrin gel reduces the level of inhibitory glycosaminoglycan chains in lesioned spinal cord. Journal of Controlled Release : Official Journal of The Controlled Release Society, 147(1), 24–29. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa Y., Imagama S., Ohgomori T., Ishiguro N., Kadomatsu K. (2015). A combination of keratan sulfate digestion and rehabilitation promotes anatomical plasticity after rat spinal cord injury. Neuroscience Letters, 593, 13–18. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzadeh A., Sarveazad A., Hamblin M. R., Teheripak G., Kookli K., Nasirinezhad F. (2020). The effect of chondroitinase ABC and photobiomodulation therapy on neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury in adult male rats. Physiology & Behavior, 227, 113141. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzadeh A., Sarveazad A., Yousefifard M., Dameni S., Samani F. S., Mokhtarian K., et al. (2017). Combine effect of Chondroitinase ABC and low level laser (660nm) on spinal cord injury model in adult male rats. Neuropeptides, 65, 90–99. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevans B., James N. D., Burnside E., McCann C. J., Thapar N., Bradbury E. J., et al. (2021). Combined treatment with enteric neural stem cells and chondroitinase ABC reduces spinal cord lesion pathology. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 12(1), 10. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L. L., Margolis R. U., Tuszynski M. H. (2003). The chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans neurocan, brevican, phosphacan, and versican are differentially regulated following spinal cord injury. Experimental Neurology, 182(2), 399–411. [DOI: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00087-6] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi-Abdolrezaee S., Eftekharpour E., Wang J., Schut D., Fehlings M. G. (2010). Synergistic effects of transplanted adult neural stem/progenitor cells, chondroitinase, and growth factors promote functional repair and plasticity of the chronically injured spinal cord. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 30(5), 1657–1676. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. G., Dai H. N., Lynskey J. V., McAtee M., Bregman B. S. (2006). Degradation of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans potentiates transplant-mediated axonal remodeling and functional recovery after spinal cord injury in adult rats. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 497(2), 182–198. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel-Bagden E., Dai H. N., Bregman B. S. (1993). Methods to assess the development and recovery of locomotor function after spinal cord injury in rats. Experimental Neurology, 119(2), 153–164. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon B. K., Okon E. B., Plunet W., Baptiste D., Fouad K., Hillyer J., et al. (2011). A systematic review of directly applied biologic therapies for acute spinal cord injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 28(8), 1589–1610. [PMID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., McKeon R. J., Bellamkonda R. V. (2010). Sustained delivery of thermostabilized chABC enhances axonal sprouting and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(8), 3340–3345. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. J., Bian S., Jakovcevski I., Wu B., Irintchev A., Schachner M. (2012). Delayed applications of L1 and chondroitinase ABC promote recovery after spinal cord injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 29(10), 1850–1863. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Wang J., Li G., Lv H. (2018). Effect of combined chondroitinase ABC and hyperbaric oxygen therapy in a rat model of spinal cord injury. Molecular Medicine Reports, 18(1), 25–30. [DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8933] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P., Wang Y., Graham L., McHale K., Gao M., Wu D., et al. (2012). Long-distance growth and connectivity of neural stem cells after severe spinal cord injury. Cell, 150(6), 1264–1273. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey J. M., Hubscher C. H., Wagoner M. R., Decker J. A., Amps J., Silver J., et al. (2006). Chondroitinase ABC digestion of the perineuronal net promotes functional collateral sprouting in the cuneate nucleus after cervical spinal cord injury. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of The Society for Neuroscience, 26(16), 4406–4414. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz G. A., Whishaw I. Q. (2009). The ladder rung walking task: A scoring system and its practical application. Journal of Visualized Experiments : JoVE, (28), 1204. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojarad N., Yousefifard M., Janzadeh A., Damani S., Golab F., Nasirinezhad F. (2016). Comparison of the antinociceptive effect of intrathecal versus intraperitoneal injection of paracetamol in neuropathic pain condition. Journal of Medical Physiology, 1(1), 10–16. [Link] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya C. P., Campbell-Hope L. J., Pemberton K. D., Dunnett S. B. (1991). The “staircase test”: A measure of independent forelimb reaching and grasping abilities in rats. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 36(2–3), 219–228. [DOI: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90048-5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountney A., Zahner M. R., Sturgill E. R., Riley C. J., Aston J. W., Oudega M., et al. (2013). Sialidase, chondroitinase ABC, and combination therapy after spinal cord contusion injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 30(3), 181–190. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramoto A., Imagama S., Natori T., Wakao N., Ando K., Tauchi R., et al. (2013). Midkine overcomes neurite outgrowth inhibition of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan without glial activation and promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Neuroscience Letters, 550, 150–155. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasirinezhad F., Hosseini M., Karami Z., Yousefifard M., Janzadeh A. (2016). Spinal 5-HT3 receptor mediates nociceptive effect on central neuropathic pain; possible therapeutic role for tropisetron. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 39(2), 212–219. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni S., Xia T., Li X., Zhu X., Qi H., Huang S., et al. (2015). Sustained delivery of chondroitinase ABC by poly(propylene carbonate)-chitosan micron fibers promotes axon regeneration and functional recovery after spinal cord hemisection. Brain Research, 1624, 469–478. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotna I., Slovinska L., Vanicky I., Cizek M., Radonak J., Cizkova D. (2011). IT delivery of ChABC modulates NG2 and promotes GAP-43 axonal regrowth after spinal cord injury. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 31(8), 1129–1139. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q., Guo Y., Kong F. (2018). Poly(glycerol sebacate) combined with chondroitinase ABC promotes spinal cord repair in rats. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. Part B, Applied Biomaterials, 106(5), 1770–1777. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raspa A., Bolla E., Cuscona C., Gelain F. (2019). Feasible stabilization of chondroitinase abc enables reduced astrogliosis in a chronic model of spinal cord injury. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 25(1), 86–100. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raspa A., Carminati L., Pugliese R., Fontana F., Gelain F. (2021). Self-assembling peptide hydrogels for the stabilization and sustained release of active Chondroitinase ABC in vitro and in spinal cord injuries. Journal of Controlled Release, 330, 1208–1219. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarveazad A., Babahajian A., Bakhtiari M., Soleimani M., Behnam B., Yari A., et al. (2016). The combined application of human adipose derived stem cells and Chondroitinase ABC in treatment of a spinal cord injury model. Neuropeptides, 61, 39–47. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarveazad A., Babahajian A., Bakhtiari M., Soleimani M., Behnam B., Yari A., et al. (2017). The combined application of human adipose derived stem cells and Chondroitinase ABC in treatment of a spinal cord injury model. Neuropeptides, 61, 39–47. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarveazad A., Bakhtiari M., Babahajian A., Janzade A., Fallah A., Moradi F., et al. (2014). Comparison of human adipose-derived stem cells and chondroitinase ABC transplantation on locomotor recovery in the contusion model of spinal cord injury in rats. Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, 17(9), 685–693. [PMID] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki M., Iwanami A., Fujiyoshi K., Tashiro S., Kitamura K., Shibata S., et al. (2016). Combined treatment with chondroitinase ABC and treadmill rehabilitation for chronic severe spinal cord injury in adult rats. Neuroscience Research, 113, 37–47. [DOI: 10.1016/j.neures.2016.07.005] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J., Miller J. H. (2004). Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 5(2), 146–156. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonen M., Pedersen V., Weinmann O., Schnell L., Buss A., Ledermann B., et al. (2003). Systemic deletion of the myelin-associated outgrowth inhibitor Nogo-A improves regenerative and plastic responses after spinal cord injury. Neuron, 38(2), 201–211. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sistrom C. L., Mergo P. J. (2000). A simple method for obtaining original data from published graphs and plots. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology, 174(5), 1241–1244. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi K., Yoshioka N., Higa Onaga S., Watanabe Y., Miyata S., Wada Y., et al. (2013). Chondroitin sulphate N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferase-1 inhibits recovery from neural injury. Nature Communications, 4, 2740. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom V. J., Kadakia R., Santi L., Houlé J. D. (2009). Administration of chondroitinase ABC rostral or caudal to a spinal cord injury site promotes anatomical but not functional plasticity. Journal of Neurotrauma, 26(12), 2323–2333. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitellaro-Zuccarello L., De Biasi S., Spreafico R. (1998). One hundred years of Golgi's “perineuronal net”: History of a denied structure. Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences, 19(4), 249–253. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Y., Chen J. K., Wu Y. T., Tsai M. J., Shyue S. K., Yang C. S., et al. (2011). Reduction in antioxidant enzyme expression and sustained inflammation enhance tissue damage in the subacute phase of spinal cord contusive injury. Journal of Biomedical Science, 18(1), 13. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Ichiyama R. M., Zhao R., Andrews M. R., Fawcett J. W. (2011). Chondroitinase combined with rehabilitation promotes recovery of forelimb function in rats with chronic spinal cord injury. The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 31(25), 9332–9344. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinal Cord Injury (SCI). Facts and Figures at a Glance. (2016) Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 39(2):243–244. [DOI: 10.1080/10790268.2016.1160676.] [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T., Huang B., Ni S., Gao L., Wang J., Wang J., et al. (2017). The combination of db-cAMP and ChABC with poly(propylene carbonate) microfibers promote axonal regenerative sprouting and functional recovery after spinal cord hemisection injury. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 86, 354–362. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Yan Y., Xia H., Zhao T., Chu W., Hu S., et al. (2015). Antisense vimentin cDNA combined with chondroitinase ABC promotes axon regeneration and functional recovery following spinal cord injury in rats. Neuroscience Letters, 590, 74–79. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L. L., Li Y., Shang F. F., Chen S. W., Chen H., Ju S. M., et al. (2016). Chondroitinase administration and pcDNA3.1-BDNF-BMSC transplantation promote motor functional recovery associated with NGF expression in spinal cord-transected rat. Spinal Cord, 54(12), 1088–1095. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. G., Jiang D. M., Quan Z. X., Ou Y. S. (2009). Insulin with chondroitinase ABC treats the rat model of acute spinal cord injury. The Journal of International Medical Research, 37(4), 1097–1107. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo M., Khaled M., Gibbs K. M., Kim J., Kowalewski B., Dierks T., et al. (2013). Arylsulfatase B improves locomotor function after mouse spinal cord injury. PLoS One, 8(3), e57415. [PMID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefifard M., Rahimi-Movaghar V., Baikpour M., Ghelichkhani P., Hosseini M., Jafari A., et al. (2016). Early versus late decompression for traumatic spinal cord injuries; A systematic review and meta-analysis. Emergency (Tehran, Iran), 5(1), e37. [PMID] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefifard M., Nasirinezhad F., Shardi Manaheji H., Janzadeh A., Hosseini M., Keshavarz M. (2016). Human bone marrow-derived and umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells for alleviating neuropathic pain in a spinal cord injury model. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 7, 36. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefifard M., Rahimi-Movaghar V., Nasirinezhad F., Baikpour M., Safari S., Saadat S., et al. (2016). Neural stem/progenitor cell transplantation for spinal cord injury treatment; A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience, 322, 377–397. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y. M., He C. (2013). The glial scar in spinal cord injury and repair. Neuroscience Bulletin, 29(4), 421–435. [PMID] [PMCID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R. R., Andrews M. R., Wang D., Warren P., Gullo M., Schnell L., et al. (2013). Combination treatment with anti-Nogo-A and chondroitinase ABC is more effective than single treatments at enhancing functional recovery after spinal cord injury. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 38(6), 2946–2961. [PMID] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R. R., Fawcett J. W. (2013). Combination treatment with chondroitinase ABC in spinal cord injury--breaking the barrier. Neuroscience Bulletin, 29(4), 477–483. [PMID] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]