Abstract

Macrophage (Mϕ)-lineage cells are integral to the immune defences of all vertebrates, including amphibians. Across vertebrates, Mϕ differentiation and functionality depend on activation of the colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF1) receptor by CSF1 and interluekin-34 (IL34) cytokines. Our findings to date indicate that amphibian (Xenopus laevis) Mϕs differentiated with CSF1 and IL34 are morphologically, transcriptionally and functionally distinct. Notably, mammalian Mϕs share common progenitor population(s) with dendritic cells (DCs), which rely on fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3L) for differentiation while X. laevis IL34-Mϕs exhibit many features attributed to mammalian DCs. Presently, we compared X. laevis CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs with FLT3L-derived X. laevis DCs. Our transcriptional and functional analyses indicated that indeed the frog IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs possessed many commonalities over CSF1-Mϕs, including transcriptional profiles and functional capacities. Compared to X. laevis CSF1-Mϕs, the IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs possess greater surface major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, but not MHC class II expression, were better at eliciting mixed leucocyte responses in vitro and generating in vivo re-exposure immune responses against Mycobacterium marinum. Further analyses of non-mammalian myelopoiesis akin to those described here, will grant unique perspectives into the evolutionarily retained and diverged pathways of Mϕ and DC functional differentiation.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Amphibian immunity: stress, disease and ecoimmunology’.

Keywords: amphibian myelopoiesis, interleukin-34, colony stimulating factor-1, fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand, macrophages, dendritic cells

1. Introduction

Myelopoiesis is the branch of hematopoiesis through which common myeloid progenitor cells give rise to megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitors or granulocyte/macrophage progenitors (GMPs) [1–3]. GMPs differentiate into either macrophage (Mϕ)- or granulocyte (Grn)-lineage cells in response to lineage-specific growth factors [4]. With progressive lineage commitment, GMPs lose their Grn-producing capacity, resulting in monocyte/Mϕ and dendritic cell (DC) progenitors (MDPs). MDPs give rise to either common dendritic cell precursor (CDP), or common monocyte progenitors (these myelopoiesis steps are depicted in the electronic supplementary material, figure S1) that are precursors to extensive repertoires of morphologically and functionally distinct subsets of Mϕs [5]. While these disparate Mϕ subsets acquire their respective functional dichotomies in response to tissue- and immune response-specific factors, all Mϕ development requires signalling through the colony stimulation factor-1 receptor (CSF1R, i.e. macrophage colony stimulating factor receptor) on the surface of GMPs and CDPs [6]. Signalling through the CSF1R is elicited by two ligands, CSF1 (i.e. M-CSF) and interleukin-34 (IL34) [7,8], which determines Mϕ differentiation and functionality [9–11].

Whereas the consequences of CSF1R activation by CSF1 have been relatively well explored in mammals, how IL34 contributes to vertebrate Mϕ biology and heterogeneity is less understood [12]. In mammals, IL34 is known to mediate the development and maintenance of tissue Mϕs and Langerhans cells [13,14], osteoclasts [15], microglia [16] as well as the development of B cell-stimulating mononuclear phagocytes [17]. The mammalian CSF1 and IL34 cytokines appear to generate Mϕs with some non-overlapping functional states [13,14].

In addition to CSF1R, MDPs also express the fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 receptor (FLT3), which is activated by the FLT3 ligand (FLT3L), resulting in differentiation of DCs [18,19]. As such, the generation of Mϕs or DCs from MDPs depend on whether CSF1R or FLT3 signalling predominates [18,19]. Consistent with lineage commitment, conventional and plasmacytoid DCs (cDCs and pDCs, respectively) reduce their surface CSF1R, whereas Mϕ-lineage cells decrease their surface FLT3 levels [20,21].

The mechanisms controlling non-mammalian myelopoiesis are poorly understood. In this respect, amphibians represent a key stage in the evolution of vertebrate immunity and thus offer unique perspectives into the diverged and conserved aspects of vertebrate myelopoiesis [22,23]. Our ongoing studies using the Xenopus laevis frog model indicate that amphibian Mϕs differentiated by IL34 and CSF1 are morphologically, transcriptionally and functionally distinct [22,24–27] and suggest that at least some of these differences have been evolutionarily conserved [28,29]. Notably, across our studies, we have noted that X. laevis IL34-Mϕs possess many features attributed to mammalian DCs [26,27]. To expand upon these observations, we produced a recombinant X. laevis FLT3L and compared the gene expression and functionality of the frog DCs generated by this factor to the X. laevis IL34- and CSF1-Mϕs.

2. Results

(a) . Frog interleukin-34-macrophage morphology and transcriptional profiles resemble fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand-dendritic cells over colony stimulation factor-1-macrophages

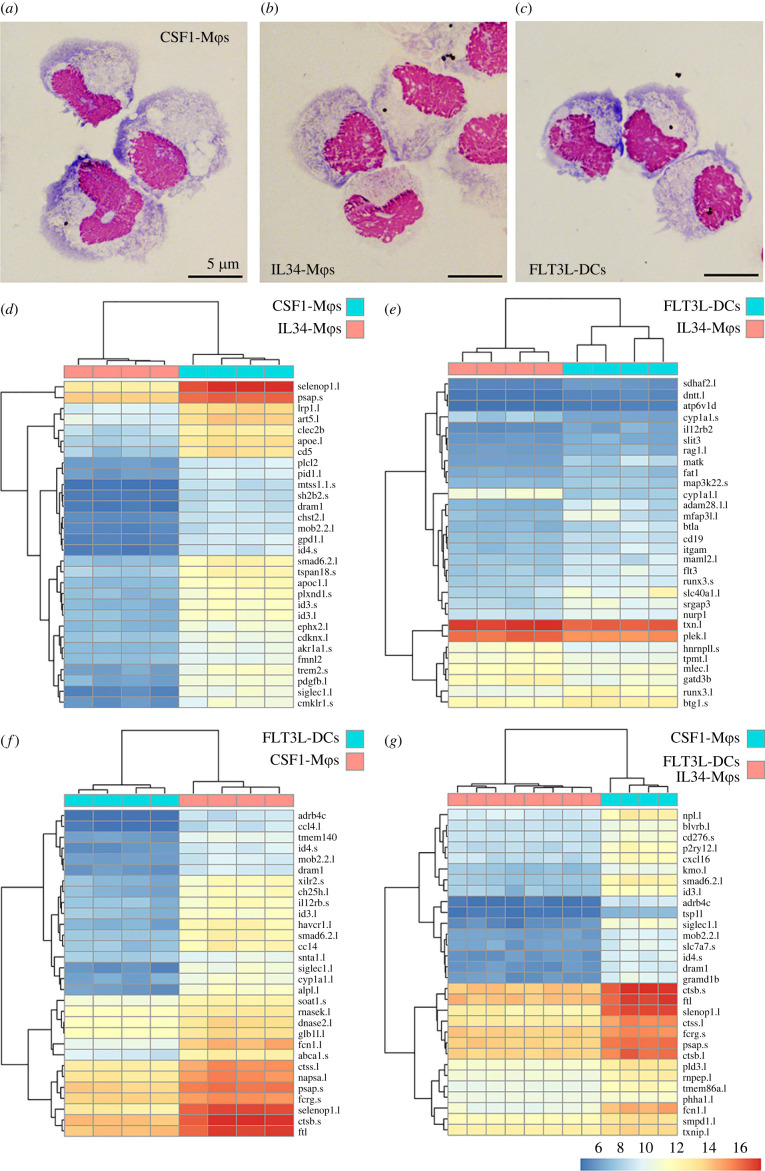

We previously showed that while most X. laevis hematopoiesis takes place in their subcapsular liver, their GMPs reside in their bone marrow [22,23]. Since MDPs are thought to arise from GMPs, we reasoned that X. laevis bone marrow should thus contain cells with CDP potential. To compare the CSF1- and IL34-Mϕs with FLT3L-DCs, we produced CSF1, IL34 and FLT3L in recombinant form and generated the respective Mϕ and DC cell types from X. laevis bone marrow cells. Our cytological analysis confirmed our previous observations that the X. laevis CSF1-Mϕs possess more vacuolation and membrane ruffling than the IL34-Mϕs (figure 1a,b; [26]). The X. laevis bone marrow-derived FLT3L-DCs resembled the IL34-Mϕs more than the CSF1-Mϕs in their size and morphology but possessed more membrane protrusions (figure 1b,c, respectively).

Figure 1.

Morphology and transcriptional profiles of X. laevis CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs. Representative morphology of Giemsa-stained (a) CSF1-Mϕs, (b) IL34-Mϕs and (c) FLT3L-DCs. Comparisons of differentially expressed genes between respective myeloid populations were conducted using DESeq2 and the top 30 significantly differentially expressed genes between (d) CSF1-Mϕs and IL34-Mϕs, (e) IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs, (f) CSF1-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs, and (g) FLT3L-DCs and IL34-Mϕs compared to FLT3L-DCs are shown as heatmaps (padj value of less than 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change > [1]). For respective comparisons, cells derived from bone marrow of distinct frogs are organized by columns and the differentially expressed genes are presented in rows with the magnitudes of differential expression denoted by colour, as indicated by the colour bar. Any gene names that appear multiple times within respective heat plots were detected as distinct based on model identities, being transcripts from distinct loci and/or being transcript from short and long arm of X. laevis chromosomes, as indicated by ‘.s' or ‘.l' suffixes, respectively. All heatmaps were visualized using the ‘pheatmap' package in R (4.0.2 version). Statistical comparisons were carried out between each of myeloid cell types (d–f) or by comparing FLT3L-DCs and IL34-Mϕs together against CSF1-Mϕs (g; n = 4/cell type). (Online version in colour.)

In a comprehensive comparison of CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs, we performed next generation RNA sequencing analyses of these populations (figures 1–3). Figure 1d–g depicts the top 30 differentially expressed genes between these respective myeloid populations. These analyses confirmed that the transcriptional profiles of the X. laevis IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs were significantly different from CSF1-Mϕs (figure 1d,f,g). Conversely, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs shared substantially similar transcriptional profiles than those observed when comparing either or both populations against the CSF1-Mϕs (figure 1e,d,f,g, respectively).

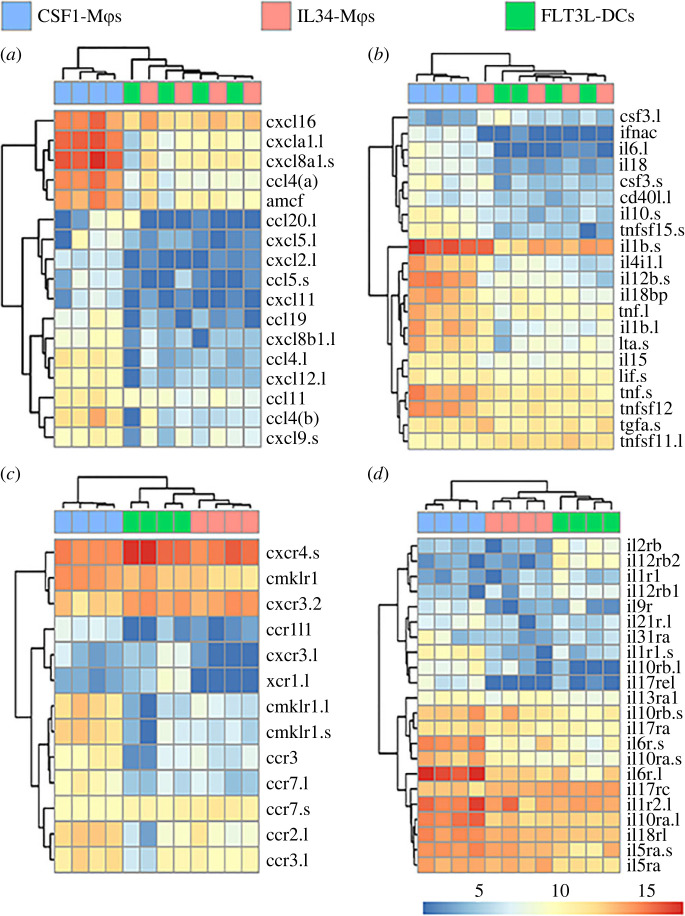

Figure 3.

Differentially expressed chemokine and cytokine ligand and receptor genes between X. laevis CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs. Heatmap plots were curated to depict differentially expressed immune genes: (a) hallmark chemokine genes, (b) cytokine genes, (c) chemokine receptor genes, and (d) cytokine receptor genes were compared between all three cell types (n = 4/cell type). All plotted genes were selected from the statistically significant (as defined by padj value of less than 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change > [1]) differentially expressed genes across all tested comparisons. For each comparison, individual samples are shown in columns and immune genes in rows with colour representation of relative expression, as indicated by the colour bar. Any gene names that appear multiple times within respective heat plots were detected as distinct based on model identities, being transcripts from distinct loci and/or being transcript from short and long arm of X. laevis chromosomes, as indicated by ‘.s’ or ‘.l' suffixes, respectively. All heatmaps were visualized using ‘pheatmap' package in R (4.0.2 version). (Online version in colour.)

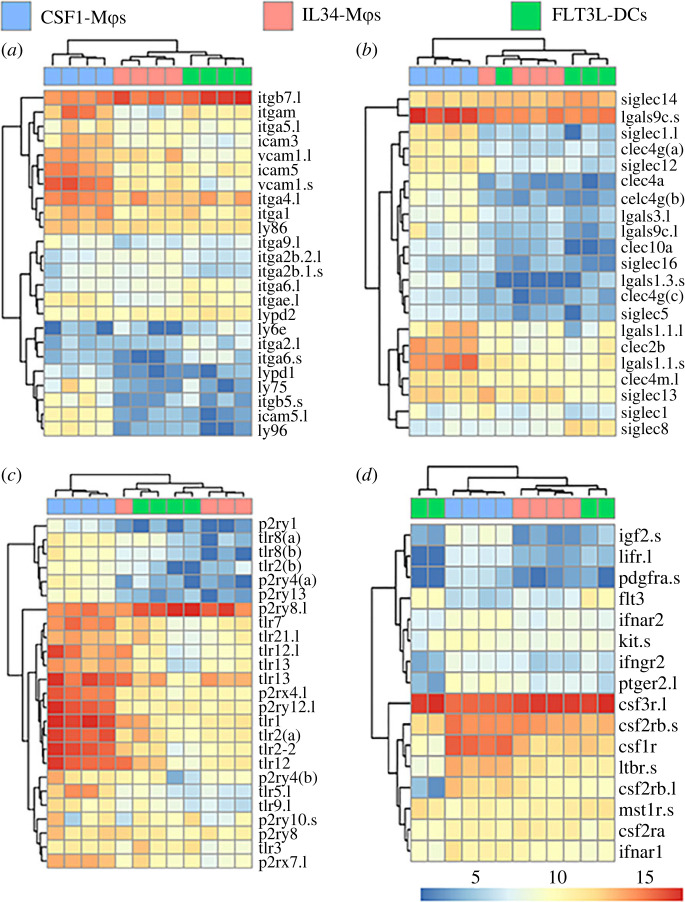

We next compared CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs transcript levels of those genes that significantly differed in expression during our pairwise expression analyses. Several surface marker and immune receptor genes were differentially expressed across the three populations (figure 2). For example, FLT3L-DCs possessed the highest expression levels of integrin beta 7 (itgb7), with IL34-Mϕs showing intermediate expression of this gene and CSF1-Mϕs possessing the lowest itgb7 transcript levels (figure 2a). IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs also possessed greater transcript levels of sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectin-14 (siglec14) than CSF1-Mϕs (figure 2b). Conversely, CSF1-Mϕs had greater transcript levels of intracellular adhesion molecule-5 (icam5), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (vcam1) and galectin-9c (igals9c.l) than IL34-Mϕs or FLT3L-DCs (figure 2a,b, respectively).

Figure 2.

Differentially expressed surface marker and myeloid growth factor receptor genes between X. laevis CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs. Heatmaps were curated to depict differentially expressed immune genes: (a,b) hallmark surface marker genes, (c) pathogen/pattern recognition receptor genes, and (d) myeloid growth factor receptor genes were compared between all three cell types (n = 4/cell type). All plotted genes were selected from the statistically significant (as defined by padj value of less than 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change > [1]) differentially expressed genes across all tested comparisons. For each comparison, individual samples are shown in columns and immune genes in rows with colour representation of relative expression, as indicated by the colour bar. Any gene names that appear multiple times within respective heat plots were detected as distinct based on model identities, being transcripts from distinct loci and/or being transcript from short and long arm of X. laevis chromosomes, as indicated by ‘.s’ or ‘.l' suffixes, respectively. All heatmaps were visualized using ‘pheatmap' package in R (4.0.2 version). (Online version in colour.)

Compared to CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs possessed greater messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of the P2Y purinoreceptor 8 (p2ry8.l; figure 2c). By contrast and compared to IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs, CSF1-Mϕs had greater transcript levels of several purine and toll-like receptor genes including p2rx4, p2ry12 and tlrs1, 2, 2–2, 12, 13 and 21 (figure 2c).

Intuitively, FLT3L-DCs possessed the greatest expression levels of FLT3 (figure 2d). We previously reported that X. laevis IL34-Mϕs possess greater levels of the colony stimulating factor-3 receptor (csf3r) than CSF1-Mϕs [26] and our present data confirmed these previous observations wherein IL34-Mϕs as well as FLT3L-DCs possessed greater csf3r transcript levels than CSF1-Mϕs (figure 2d). By contrast, CSF1-Mϕs had greater levels of csf1r transcripts than IL34-Mϕs or FLT3L-DCs (figure 2d).

Compared to IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs, CSF1-Mϕs possessed greater expression of several inflammatory chemokine (figure 3a) and cytokine (figure 3b) genes whereas IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs possessed greater transcript levels of csf3(.l) than CSF1-Mϕs (figure 3b). FLT3L-DCs had the greatest expression of CXC chemokine receptor-4 (cxcr4), followed by IL34-Mϕs, with CSF1-Mϕs having the lowest expression of this gene (figure 3c). Compared to CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs also had greater expression of cxcr3.2 and CC-chemokine receptor-7 (ccr7.s), whereas CSF1-Mϕs had greater transcript levels of chimerin chemokine-like receptor-1 (cmklr1), ccr2 and ccr3 (figure 3c). FLT3L-DCs possessed greater levels of interleukin-2 receptor beta (il2rb) and interleukin-12 receptor beta-2 (il12rb2) than IL34- or CSF1-Mϕs (figure 3d). By contrast, CSF1-Mϕs possessed greater transcript for several inflammatory cytokine receptors (figure 3d).

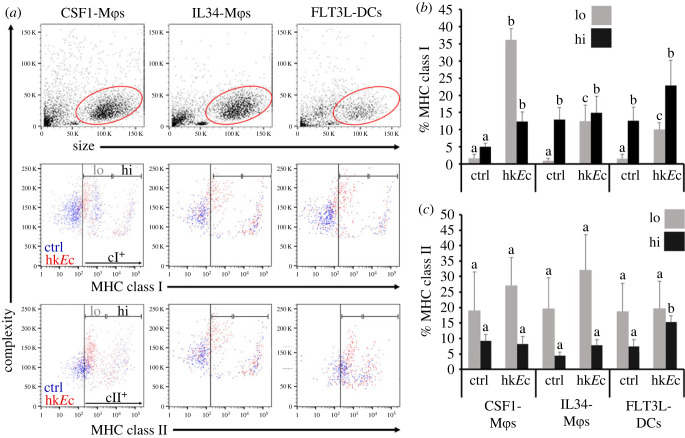

(b) I . nterleukin-34-macrophages, colony stimulation factor-1-macrophages and fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand-dendritic cells have disparate baseline and heat-killed Escherichia coli-induced major histocompatibility complex I and II cell surface expression

Mϕs and DCs are considered ‘professional' antigen presenting cells and thus, we used flow cytometry to assess the surface expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I (cI) and II (cII) on X. laevis bone marrow-derived IL34-Mϕs, CSF1-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs at steady state and following stimulation with heat-killed Escherichia coli (hkEc; figure 4). At baseline (unstimulated), each of the three myeloid subset cultures was composed of MHC class I negative (MHCI−), MHCI low (MHCIlo) and MHCI high (MHCIhi) expressing populations (figure 4a,b). In the absence of stimulation, the three culture types did not differ in their proportions of MHCIlo cells, while the IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs exhibited significantly greater proportions of MHCIhi cells compared to the CSF1-Mϕ cultures (figure 4a,b). Stimulation with hkEc resulted in significantly increased proportions of MHCIlo cells within all three culture types, with CSF1-Mϕ cultures comprising of significantly greater numbers of MHCIlo cells than IL34-Mϕ or FLT3L-DC cultures (figure 4a,b). In some, but not all these hkEc-stimulated CSF1-Mϕ cultures, the elicited MHCIlo populations possessed discernably lower MHCI surface levels than seen on the MHCIlo populations within respective (derived from the same individual frogs), unstimulated CSF1-Mϕ cultures (figure 4a). Notably, the hkEc-stimulation resulted in significantly increased proportions of MHCIhi cells within CSF1-Mϕ cultures, reaching levels seen in baseline and hkEc-stimulated IL34-Mϕ or FLT3L-DC cultures (figure 4a,b). By contrast, hkEc-stimulation did not result in significant changes to the proportions of MHCIhi cells within IL34-Mϕ or FLT3L-DC cultures, as compared to the respective (derived from the same individual frogs), unstimulated cultures (figure 4a,b).

Figure 4.

Comparisons of MHC class I and II surface expression by X. laevis CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs. CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DC cell cultures were incubated with amphibian phosphate buffered saline (control; ctrl) or heat-killed E. coli (hkEc) for 16 h and stained with anti-X. laevis class I (TB17) or class II (AM20) and secondary DyLight 650-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) antibodies and examined by flow cytometry. (a) Representative size versus complexity, class I and class II staining plots for respective myeloid populations. Events from control and heat-killed E. coli-stimulated cultures are depicted in blue and red, respectively. Gates for MHCI and MHCII negative, low (lo) and high (hi) expressing cells were established through preliminary analyses and implemented to examine the control and stimulated cultures; representative plots in (a). (b) Proportions of MHC class I and (c) MHC class II low (lo) and high (hi) CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs (n = 6). Results in (b and c) are means + s.e.m. The letters above bars indicate statistical significance, with distinct letters representing statistically different groups, p < 0.05. (Online version in colour.)

The three unstimulated myeloid subset cultures possessed comparable proportions of MHC class II negative (MHCII−), MHCII low (MHCIIlo) and MHCII high (MHCIIhi) expressing populations (figure 4a,c). HkEc-stimulation did not result in significant changes to the proportions of MHCIIlo cells within the any of the three culture types (figure 4a,c). HkEc-stimulated FLT3L-DC cultures possessed significantly higher proportions of MHCIIhi cells than seen in the respective unstimulated FLT3L-DC cultures, as well as greater numbers of MHCIIhi cells than seen in unstimulated or stimulated IL34-Mϕ or CSF1-Mϕ cultures (figure 4a,c). HkEc-stimulation did not alter the MHCIIhi cell compositions within IL34-Mϕ or CSF1-Mϕ cultures (figure 4a,c).

It is notable that the MHCIlo and MHCIIlo cells within HkEc-stimulated IL34-Mϕ, CSF1-Mϕ and FLT3L-DC cultures had greater internal complexity than the MHCI− and MHCII− cells within the baseline or stimulated cultures, possibly owing to activation/maturation, phagocytosis of the HkEc, or both (figure 4a).

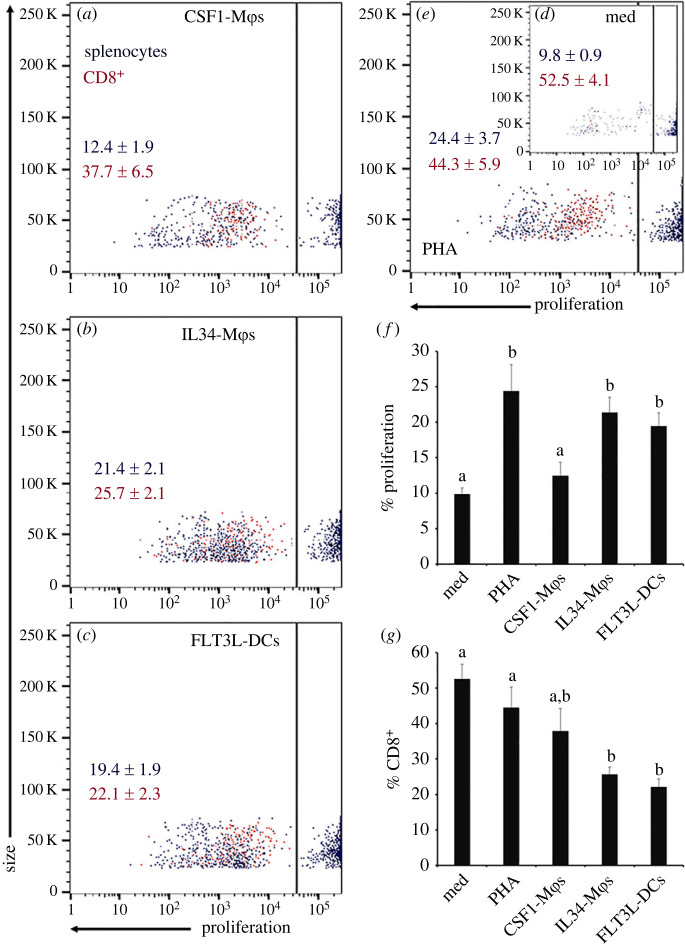

(c) . Interleukin-34-macrophages and fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand-dendritic cells elicit more robust mixed leucocyte responses than colony stimulation factor-1-macrophages

To expand our comparison of CSF1-Mϕ, IL34-Mϕ and FLT3L-DC antigen presentation capacities, we next performed mixed leucocyte reactions by co-incubating the respective myeloid subsets with splenocytes from allogenic frogs. To this end, we incubated CSF1-Mϕ, IL34-Mϕ and FLT3L-DC cultures with cell tracer violet-labelled allogenic splenocytes and two days later examined the extent of cell tracer violet-dilution and hence splenocyte proliferation, as a measure of their activation (figure 5). The proliferation of splenocytes co-incubated with IL34-Mϕs or FLT3L-DCs was significantly greater than that seen in splenocytes incubated in media alone or splenocytes co-incubated with CSF1-Mϕs (figure 5a–d,f) and was comparable to the magnitudes of proliferation seen in splenocytes stimulated with the phytohemagglutinin (PHA; positive control) T cell mitogen (figure 4e,f). Surprisingly, the proliferating fraction of IL34-Mϕ- and FLT3L-DC-activated splenocytes consisted of fewer CD8+ cells compared to control cultures, splenocytes co-incubated with CSF1-Mϕs or splenocytes stimulated with PHA (figure 5a–d,g).

Figure 5.

Comparing the capacities of X. laevis CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs to generate allogeneic (mixed leucocyte) responses. Frog splenocytes were stained using the CellTrace Violet Cell Proliferation Kit and co-incubated with CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs or FLT3L-DC cell cultures (five splenocytes per myeloid cell), incubated with medium alone or with phytohemagglutinin-P (PHA; 1 µg ml−1) for 48 h. Cultures were then stained with an anti-X. laevis CD8 (AM22) and DyLight 650-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies and analysed by flow cytometry. Representative scatter plots of splenocyte proliferation following co-incubation with (a) CSF1-Mϕs, (b) IL34-Mϕs, (c) FLT3L-DCs, (d, inset) medium alone of (e) PHA. Within respective scatter plots, the means + s.e.m. of per cent proliferating splenocytes are in black font and the means ± s.e.m. of the per cent of the proliferating splenocytes that were CD8+ are in red font. (f) Means + s.e.m of proliferating splenocytes (n = 6). (g) Means + s.e.m. of per cent of CD8+ proliferating splenocytes (n = 6). Letters above bars (f,g) indicate statistical significance, with distinct letters representing statistically different groups, p < 0.05.

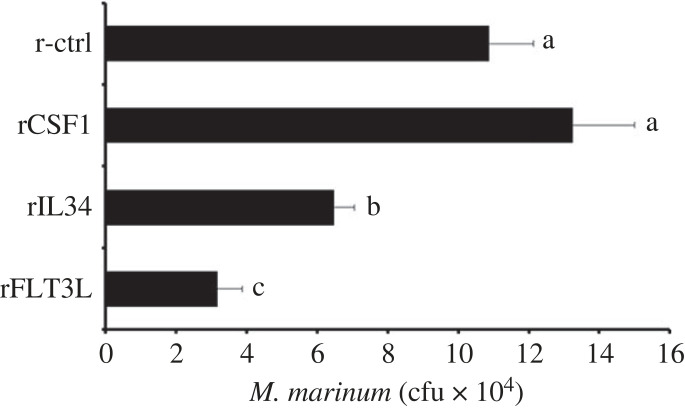

(d) . Interleukin-34-macrophages and fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand-dendritic cells appear to contribute more to re-exposure responses than colony stimulation factor-1-macrophages

We previously showed that injecting frogs with recombinant CSF1 or IL34 polarizes their Mϕs towards the respective Mϕ types [24,25,30]. To get further insight into the antigen presentation capacities of these Mϕ subsets and the frog FLT3L-DCs, we primed frogs with recombinant forms of CSF1, IL34 or FLT3L and challenged them with heat-killed Mycobacterium marinum (107 colony forming units (cfu) frog−1) or with UV-inactivated Frog Virus 3 (FV3; 5 × 106 plaque forming units (pfu) frog−1). We reared the animals for one month and re-challenged them with viable M. marinum (105 cfu frog−1) or FV3 (106 pfu frog−1), respectively. Mycobacterium marinum prominently targets frog liver [28,31–33], and we observed that the animals that had received recombinant IL34 or FLT3L prior to stimulation and rechallenge, had significantly lower M. marinum burdens in their livers compared to control or recombinant CSF1-adminsitered and challenged frogs (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Anti-M. marinum memory responses of CSF1-Mϕ-, IL34-Mϕ-, FLT3L-DC-enriched X. laevis. Frogs were enriched for Mϕs or DCs through intraperitoneal injection with 2.5 µg of recombinant (r) CSF1, rIL34, or rFLT3L or equal volumes of the recombinant control (r-ctrl). After 3 days, six frogs from each treatment group (n = 6) were intraperitoneally injected with heat-killed M. marinum (107 cfu frog−1). Thirty days following immune challenge, animals were rechallenged with viable M. marinum (105 cfu frog−1). After an additional 7 days, frog livers were collected and processed for M. marinum cfu loads. The results are presented as means + s.e.m. of M. marinum cfu per tissue. Letters above bars (f,g) indicate statistical significance, with distinct letters representing statistically different groups, p < 0.05.

Frog kidneys are a central site of FV3 replication [34–36]. Compared to control animals, we observed a non-significant trend towards lower kidney FV3 DNA loads in the kidneys of recombinant IL34-pretreated frogs and towards higher kidney FV3 DNA loads in recombinant FT3L-treated frogs (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

3. Discussion

In mammals, IL34 participates in the ontogeny and maintenance of the Langerhans cells [13,14], which share many characteristics with DCs. It is thus not surprising that the frog IL34-Mϕs share many features with the frog FLT3L-DCs. Our past work indicates that like mammalian plasmacytoid DCs [37], the X. laevis IL34-Mϕs also play important antiviral roles including the production of antiviral interferon cytokines [27] and express many of the surface markers, transcription factors and immune genes associated with mammalian DCs [26]. Indeed, in some inflammatory settings, monocytes give rise to monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) or inflammatory DCs [38], underscoring that even after lineage-commitment/differentiation, mammalian Mϕ-lineage cells retain the capacity to transition into DC (like) cells. Moreover, with the exception of their high Fc-gamma receptor 1 expression [39], these MoDCs share many features with conventional DCs including conserved expression of certain markers and immune genes [4].

Whereas mammalian Mϕs are primarily thought to survey tissues and orchestrate immune responses therein [40], upon encountering foreign/altered-self antigens DCs traffic to lymphoid organs where they present these antigens to T cells [21]. Despite this oversimplified view of the respective roles of these cell types, under some conditions Mϕs also travel to lymph nodes [41,42]. Thus, even in mammals there is a propensity for Mϕs to adopt functional roles attributed to DCs. Amphibians lack lymph nodes and their spleens serve as their major secondary lymphoid organs [43]. Also, while little is known about how antigens are trafficked to amphibian spleens, a growing body of literature suggests that this may be conferred by myeloid DC-like cell subset(s) coined XL cells [44]. Possibly, in the absence of lymph nodes, amphibian IL34-Mϕs may have adopted roles associated with mammalian DCs, including contributing to antigen trafficking to the spleen and/or may even give rise to these XL cells. It is notable that the X. laevis IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs were equally effective at enhancing reexposure responses against M. marinum. Perhaps because amphibian lymphoid systems are less complex than those of mammals, amphibian (IL34-derived) Mϕs and DCs are comparably responsible for T cell activation. It will be interesting to learn with future studies which immune roles are shared between these frog immune subsets, and which are unique to the respective cell types.

We previously observed that bone marrow-derived Mϕs expressed low levels of MHC class II [45] and here we observed that CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs possessed low surface expression of MHC class I and II. This is consistent with what is seen in mammalian Mϕs [46,47] and DCs [48], wherein unstimulated mammalian bone marrow-derived Mϕs and DCs likewise express low levels of MHC. The expression of MHC and other immune effector molecules on myeloid cells depends on the microenvironment/condition that the cells are in [49]. Presumably, CSF1, IL34 and FLT3L each culminate in myeloid subsets with unique baseline activation/differentiation states that are further honed to meet the immunological and physiological needs of the tissues that they occupy. This is supported by our observation that heat-killed E. coli stimulation resulted in distinct changes in the compositions of low and high MHC class I- and II-expressing cell populations within each of these three myeloid culture types. Moreover, the differences in the observed mixed leucocyte responses and the immunological memory conferred by these disparate myeloid subsets may also reflect differences in the in vitro and in vivo cellular/milieu interactions, possibly culminating in distinct capacities of these respective cell types to process/present antigens and co-stimulate/activate lymphocytes. Considering that at least some of the functional features of frog IL34-Mϕs are shared by their mammalian counterparts [28,29,45], it will be most interesting to learn what features of CSF1- IL34- and FLT3L-mediated myeloid cell differentiation, and by extension antigen presentation capacities, are evolutionarily conserved and which aspects are dependent on amphibian versus mammalian physiologies.

Daily FLT3L administration to mice for over a week result in significantly increased numbers of mature DCs [50]. Conversely, we found that optimal frog Mϕ expansion occurred three days following single injections of animals with rCSF1 or rIL34 [24,25]. Based on these past studies and out of concerns for possible confoundment from immune activation and/or stress owing to repeated animal handling/injections, we chose to implement our previous approach when expanding frog CSF1-/IL34-Mϕ and FLT3L-DCs. We acknowledge that these enrichment approaches may be further refined in future studies, using different permutations of our expansion approaches and with greater availability of reagents by which to visualize amphibian DCs in vivo.

In the present study, we employed cells from outbred allogeneic X. laevis to examine the capacities of CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DC to elicit mixed leucocyte reactions in allogeneic splenocytes and in vivo memory responses to M. marinum and FV3. Except for the FV3 re-exposure study, these experiments yielded meaningful results. However, we believe that future studies of this nature could be improved by using inbred J-strain X. laevis as sources of bone marrow cells for the CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DC cell cultures towards the mixed leucocyte response studies, and for the in vivo re-exposure studies. Indeed, the variability of responses seen in FV3 re-challenge experiments presented here would undoubtedly be minimized by using J strain animals to perform follow-up experiments akin to that one.

We previously observed that CSF1-Mϕs and IL34-Mϕs isolated from X. laevis possess the respective morphologies and overall functionalities of their in vitro bone marrow-derived counterparts but differ in their gene expression profiles [24,25,27]. As described above, we anticipate that the phenotypes of the bone marrow-derived CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DCs represent general polarization states that would be further honed and/or altered in vivo by the local tissue milieu wherein such frog cells would reside.

Mϕs and lineage-related cells play integral roles in vertebrate immune systems, serving as both vectors and combatants of pathogens as diverse as those contributing to the amphibian declines [51] to the one that has caused the current human pandemic [52,53]. Comparative studies exploring the functional relationships between respective myeloid cell subsets and across diverged species will grant unique perspectives into evolutionarily shared and species-specific aspects of these cell types. In turn, such new perspectives into the evolution of vertebrate myelopoiesis will yield new avenues by which to improve both ecological and human health.

4. Methods

(a) . Animals and cell culture

All animals were purchased from the Xenopus 1 (Dexter, MI, USA) and reared in-house under strict laboratory conditions in accordance with IACUC regulations (approval number 15-024).

Amphibian serum-free (ASF) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.25% X. laevis serum, 10 µg ml−1 gentamycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 U ml−1 penicillin (Gibco), 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin (Gibco) was used for all cell culture. Amphibian phosphate buffered saline (APBS) has been described [54].

Xenopus laevis bone marrow CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DC cell cultures were generated as follows. Femur bones from adult (1–2 years old) frogs (n = 6–8) were aseptically removed and flushed with 10 ml of ice-cold APBS. Bone marrow cells were collected by centrifugation, washed and re-suspended in cell culture medium. Cells were seeded into 96-well plates for functional assays (104 cells well−1) and 48-well plates for transcriptomics (105 cells well−1). Cells were incubated with 250 ng ml−1 of rCSF1, rIL34 or rFLT3L at 27°C and 5% CO2. All cultures were again treated with corresponding cytokines after 3 days of culture and the cultures were harvested after 5 days. For all experiments described in this manuscript, CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DC cell cultures were established using bone marrow cells from the same respective animals.

(b) . Production of recombinant colony stimulation factor-1, interleukin-34 and recombinant fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand cytokines

The X. laevis rCSF1 , rIL-34 and rFLT3L cytokines were produced as previously described [25]. Briefly, sequences corresponding to the signal peptide-cleaved CSF1, IL34 or FLT3L were cloned into pMIB/V5 His A vectors and these constructs were transfected into Sf9II insect cells (cellfectin II, Invitrogen). Recombinant protein production by the transfected Sf9II cells was confirmed by western blot, and the positive transfectants were selected using 10 µg ml−1 blasticidin. The expression cultures were scaled up as 500 ml liquid cultures, grown for 5 days, pelleted, and the supernatants collected. These supernatants were concentrated against polyethylene glycol flakes (8 kDa) at 4°C, dialysed overnight at 4°C against 150 mM sodium phosphate, and passed through Ni-NTA agarose columns (Qiagen). Columns were washed with 2 × 10 volumes of high stringency wash buffer (0.5% Tween 20; 50 mM sodium phosphate; 500 mM sodium chloride; 100 mM Imidazole) and 5 × 10 volumes of low stringency wash buffer (as above, but with 40 mM imidazole). Recombinant cytokines were eluted using 250 mM imidazole and their presence was confirmed by western blots against the V5 epitopes on the proteins. Protein concentrations were determined by Bradford protein assays (Bio-Rad). Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (containing AEBSF, aprotinin, bestatin, E-64, leupeptin and pepstatin A; Thermo Scientific) was added to the purified proteins, which were then stored at −20°C in aliquots until use.

The recombinant control (r-ctrl) was produced by transfecting an empty pMIB/V5 His A insect expression vector into Sf9II cells, isolating, and processing the resulting cell supernatants as above.

(c) . RNA and DNA isolation and frog virus 3 DNA load analysis

For all experiments, tissues and cells were homogenized by passage through progressively higher gauge needles in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), flash frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until RNA and DNA isolation. RNA isolation was performed using Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's directions. DNA was isolated from the Trizol following RNA isolation. In brief, following phase separation and extraction of RNA, the remaining Trizol layer was mixed with back extraction buffer (4 M guanidine thiocyanate, 50 mM sodium citrate, 1 M Tris pH 8.0), and centrifuged to isolate the DNA containing aqueous phase. The DNA was precipitated overnight with isopropanol, pelted by centrifugation, washed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). DNA was then purified by phenol: chloroform extraction and resuspended in molecular grade water.

For FV3 DNA copy number analyses, an FV3 standard curve was generated by serially diluting FV3 vDNA Pol (ORF 60R) fragment cloned into pGEM-T plasmid. This FV3 DNA Pol standard curve was used in absolute quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), assessing ‘absolute' FV3 DNA copies per 500 ng of input DNA from each sample of interest. All qPCR assays were performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and all experiments were analysed via CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and The BioRad CFX Manager software (SDS).

(d) . Frog virus 3

FV3 was propagated in baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cells by inoculating fresh BHK-21 cultures with FV3 (multiplicity of infection: 0.1 pfu of FV3 per cell) and maintained at 30°C and 5% CO2 until the cultures were completely lysed (approx. 5 days). The culture lysates were subjected to ultracentrifugation to obtain supernatant with FV3 using 30% sucrose. The supernatant was resuspended in saline, and plaque assay analysis on BHK- 21 cells was used for determining the viral titres.

FV3 was UV-inactivated by exposure to 150 mJ of UV energy at 56°C for 30 min (Spectro Linker XC-1000 UV crosslinker), which was previously shown to successfully inactivate this virus [55]. Successful virus inactivation was confirmed by no plaque formation or cell lysis after plating the UV-irradiated virus on BHK-21 cells.

(e) . Mycobacterium marinum

Mycobacterium marinum (strain TMC 1218) was purchased from ATCC and grown with shaking at 30°C in Middlebrook 7H9 (Difco, Leeuwarden, Netherlands) broth supplemented with 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween-80 and albumin dextrose catalase (0.5% bovine serum albumin fraction V, 0.2% dextrose and 0.85% NaCl). The bacteria were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and viable counts subsequently determined by plating onto Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates and thus determining the cfu.

Mycobacterium marinum was heat-inactivated by incubation in an 80°C water bath for 30 min. Heat-inactivation (lack of bacterial viability) was confirmed by plating the heat-killed M. marinum on Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates.

The M. marinum loads in frog livers were assessed by aseptically isolating whole livers, mincing and passing these respective suspensions through progressively smaller gage needles (BD PrecisionGlide, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) to reach cell suspension. These cell-suspensions were then washed twice with PBS and incubated in 50 µl of sterile 0.1% Tween-20 in distilled water for 10 min to lyse the cells. After lyses, 150 µl of Middlebrook 7H9 medium (Difco) broth was added to each sample. Each sample was serially diluted in Middlebrook 7H9 medium and plated onto Middlebrook 7H10 (Difco, Leeuwarden, Netherlands) agar plates. The plates were incubated at 30°C and the resulting colonies scored, averaged and presented as cfu mg−1 of tissue.

(f) . Frog macrophage and dendritic cell enrichment and immune challenges

Frogs were enriched for Mϕs and DCs via intraperitoneal injection with 2.5 µg of rCSF1, rIL34 or rFLT3L in APBS or equal volumes of the recombinant control (r-ctrl). After 3 days (optimal time for expanding and polarizing Mϕs in vivo [24,25]), six frogs from each treatment groups were intraperitoneally injected with either UV-irradiated FV3 (with 5 × 106 pfu frog−1) or heat-killed M. marinum (107 cfu frog−1). After 30 days of challenge, animals were respectively rechallenged with viable FV3 (106 pfu frog−1) or viable M. marinum (105 cfu frog−1). After an additional 7 days, frog kidneys (for FV3 DNA analysis) and livers (for M. marinum load analysis) were collected and processed for respective pathogen load analyses.

(g) . RNA sequencing and analyses

Towards RNA sequencing analyses, CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DC cell cultures were prepared as described above and sorted based on size/internal complexity parameters to ensure that only the fully differentiated populations were examined. The sorted cells were spun down, resuspended in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and RNA was immediately isolated using the methods described above. The RNA was flash-frozen over dry ice and sent to Azenta (formerly GeneWiz) for library preparation, RNA sequencing and analyses.

The RNA sample received was quantified using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) and RNA integrity was checked using TapeStation (Agilent Technologies). RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina via manufacturer's instructions (New England Biolabs). Briefly, mRNAs were initially enriched with Oligod(T) beads. Enriched mRNAs were fragmented for 15 min at 94°C. First strand and second strand complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were subsequently synthesized. cDNA fragments were end repaired and adenylated at 3′ends, and universal adapters were ligated to cDNA fragments, followed by index addition and library enrichment by PCR with limited cycles. The sequencing libraries were validated on the Agilent TapeStation (Agilent Technologies) and quantified by using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) as well as by qPCR (KAPA Biosystems). Paired-end RNA sequencing of these libraries was performed on an Illumina HiSeq, PE 2 × 150 platform. Sequence reads were trimmed to remove possible adapter sequences and nucleotides with poor quality using Trimmomatic v. 0.36. The trimmed reads were mapped to the Xenopus_laevis_30-624818564 reference genome available on ENSEMBL using the STAR aligner v. 2.5.2b. Unique gene hit counts were calculated by using feature counts from the Subread package v. 1.5.2. After extraction of gene hit counts, the gene hit counts table was used for downstream differential expression analysis. Comparisons of CSF1-Mϕ, IL34-Mϕ and FLT3L-DC transcriptional profiles were performed using DESeq2. The Wald test was used to generate p-values and log2 fold changes. Genes with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change > [1] were deemed to be differentially expressed for each comparison.

(h) . Flow cytometry analyses

CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DC cell cultures were generated as described above. For MHC class I and II staining, cells were collected by centrifugation and stained with anti-X. laevis class I (TB17) [56,57] or class II (AM20) [58,59], followed by DyLight 650-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Control samples were stained with the secondary antibody alone. For all stained cultures, 5000 cellular events were analysed on a BD FACSCelesta Cell Analyzer (BD Bioscience) and the resulting data was curated using FlowJo software.

For heat-killed E. coli (DH5) stimulations, E. coli were enumerated by growing serial dilutions of E. coli on agar plates and counting the resulting colonies. The enumerated E. coli were then heat killed by boiling for 1 h and confirmed to be non-viable by plating on agar plates and failing to observe growth. CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DC cell cultures were then established as described above and co-incubated with the either heat-killed E. coli (5 cfu myeloid cell−1) or APBS (in medium; control) for 16 h prior to staining and flow cytometry analyses for MHC class I or MHC class II expression, as described above. The control and heat-killed E. coli-stimulated CSF1-Mϕ, IL34-Mϕ and FLT3L-DC cultures were generated using bone marrow cells from the same respective frogs.

Towards mixed leucocyte reaction assays, spleens were aseptically removed from outbred adult frogs (n = 3–5) and dissociated by passage through nylon cell strainers (Becton Dickinson Labware). Leucocytes were separated from red blood cells via Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich) gradient centrifugation, and the cells in the buffy coat layer were enumerated by trypan blue viability exclusion. These splenocytes were then stained using the CellTrace Violet Cell Proliferation Kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. Labelled splenocytes were co-incubated with CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs or FLT3L-DC cell cultures (5 splenocytes myeloid cell−1), incubated with medium alone or in the presence of the T-cell mitogen, PHA-p (1 µg ml−1) for 48 h. Cultures were then stained with an anti-X. laevis CD8 (AM22) [58,59], followed by DyLight 650-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) and analysed using a BD FACSCelesta Cell Analyzer (BD bioscience) with the resulting data curated using FlowJo software. For all mixed leucocyte reaction assays, CSF1-Mϕs, IL34-Mϕs and FLT3L-DC stimulating cells were derived from the same pools of bone marrow cells (same repertoires of MHCI and II) and the responding, labelled splenocytes were derived from distinct sets of animals.

(i) . Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses of transcriptomics data are described above. All other statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical software (v. 4.0.2). Datasets were assessed by one-way ANOVAs followed by post hoc Tukey's tests for multiple comparison and p-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Jacques Robert and the Xenopus Immunology Resource for kindly providing us with the anti-X. laevis MHC class I, anti-X. laevis MHC class II and anti-X. laevis CD8 antibodies. M.R.H.H., K.A.H. and C.M.G. thank the Wilbur V. Harlan endowment for summer research support. We thank Dr Gregory Cresswell and Dr Christopher Lazarski for their help with flow cytometry and cell sorting. We thank the reviewers whose insightful suggestions helped improve the content and scope of this manuscript.

Ethics

All animals were purchased from the Xenopus 1 (Dexter, MI, USA) and reared in-house under strict laboratory conditions in accordance with IACUC regulations (approval number 15-024).

Data accessibility

The data are provided in the electronic supplementary material [60].

Authors' contributions

M.R.H.H.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; K.A.H.: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft; C.N.G.: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—original draft; N.K.: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization; J.M.G.: data curation, formal analysis, validation; L.G.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by a grants from National Science Foundation-IOS:1749427 and IOS: 100839 to L.G.

References

- 1.Ciau-Uitz A, Monteiro R, Kirmizitas A, Patient R. 2014. Developmental hematopoiesis: ontogeny, genetic programming and conservation. Exp. Hematol. 42, 669-683. ( 10.1016/j.exphem.2014.06.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cumano A, Godin I. 2007. Ontogeny of the hematopoietic system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 745-785. ( 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141538) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orkin SH, Zon LI. 2008. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell 132, 631-644. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.025) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Kleer I, Willems F, Lambrecht B, Goriely S. 2014. Ontogeny of myeloid cells. Front. Immunol. 5, 423. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00423) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naik SH, Metcalf D, van Nieuwenhuijze A, Wicks I, Wu L, O'Keeffe M, Shortman K. 2006. Intrasplenic steady-state dendritic cell precursors that are distinct from monocytes. Nat. Immunol. 7, 663-671. ( 10.1038/ni1340) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin W, et al. 2019. Function of CSF1 and IL34 in macrophage homeostasis, inflammation, and cancer. Front. Immunol. 10, 2019. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulakirba S, et al. 2018. IL-34 and CSF-1 display an equivalent macrophage differentiation ability but a different polarization potential. Sci. Rep. 8, 256. ( 10.1038/s41598-017-18433-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chihara T, Suzu S, Hassan R, Chutiwitoonchai N, Hiyoshi M, Motoyoshi K, Kimura F, Okada S. 2010. IL-34 and M-CSF share the receptor Fms but are not identical in biological activity and signal activation. Cell Death Differ. 17, 1917-1927. ( 10.1038/cdd.2010.60) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belosevic M, Hanington PC, Barreda DR. 2006. Development of goldfish macrophages in vitro. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 20, 152-171. ( 10.1016/j.fsi.2004.10.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonifer C, Hume DA. 2008. The transcriptional regulation of the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (csf1r) gene during hematopoiesis. Front. Biosci. 13, 549-560. ( 10.2741/2700) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones CV, Ricardo SD. 2013. Macrophages and CSF-1: implications for development and beyond. Organogenesis 9, 249-260. ( 10.4161/org.25676) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin H, et al. 2008. Discovery of a cytokine and its receptor by functional screening of the extracellular proteome. Science 320, 807-811. ( 10.1126/science.1154370) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greer AL, Berrill M, Wilson PJ. 2005. Five amphibian mortality events associated with ranavirus infection in south central Ontario, Canada. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 67, 9-14. ( 10.3354/dao067009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Colonna M. 2014. Interkeukin-34, a cytokine crucial for the differentiation and maintenance of tissue resident macrophages and Langerhans cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 1575-1581. ( 10.1002/eji.201344365) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baud'huin M, Renault R, Charrier C, Riet A, Moreau A, Brion R, Gouin F, Duplomb L, Heymann D. 2010. Interleukin-34 is expressed by giant cell tumours of bone and plays a key role in RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. J. Pathol. 221, 77-86. ( 10.1002/path.2684) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greter M, et al. 2012. Stroma-derived interleukin-34 controls the development and maintenance of Langerhans cells and the maintenance of microglia. Immunity 37, 1050-1060. ( 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamane F, et al. 2014. CSF-1 receptor-mediated differentiation of a new type of monocytic cell with B cell-stimulating activity: its selective dependence on IL-34. J. Leukoc. Biol. 95, 19-31. ( 10.1189/jlb.0613311) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karsunky H, Merad M, Cozzio A, Weissman IL, Manz MG. 2003. Flt3 ligand regulates dendritic cell development from Flt3+ lymphoid and myeloid-committed progenitors to Flt3+ dendritic cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 198, 305-313. ( 10.1084/jem.20030323) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid MA, Kingston D, Boddupalli S, Manz MG. 2010. Instructive cytokine signals in dendritic cell lineage commitment. Immunol. Rev. 234, 32-44. ( 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00877.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hettinger J, Richards DM, Hansson J, Barra MM, Joschko AC, Krijgsveld J, Feuerer M. 2013. Origin of monocytes and macrophages in a committed progenitor. Nat. Immunol. 14, 821-830. ( 10.1038/ni.2638) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. 2013. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31, 563-604. ( 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074950) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yaparla A, Reeves P, Grayfer L. 2019. Myelopoiesis of the amphibian Xenopus laevis is segregated to the bone marrow, away from their hematopoietic peripheral liver. Front. Immunol. 10, 3015. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yaparla A, Wendel ES, Grayfer L. 2016. The unique myelopoiesis strategy of the amphibian Xenopus laevis. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 63, 136-143. ( 10.1016/j.dci.2016.05.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grayfer L, Robert J. 2014. Divergent antiviral roles of amphibian (Xenopus laevis) macrophages elicited by colony-stimulating factor-1 and interleukin-34. J. Leukoc. Biol. 96, 1143-1153. ( 10.1189/jlb.4A0614-295R) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grayfer L, Robert J. 2015. Distinct functional roles of amphibian (Xenopus laevis) colony-stimulating factor-1- and interleukin-34-derived macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 98, 641-649. ( 10.1189/jlb.4AB0315-117RR) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yaparla A, Koubourli D, Popovic M, Grayfer L. 2020. Exploring the relationships between amphibian (Xenopus laevis) myeloid cell subsets. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 113, 103798. ( 10.1016/j.dci.2020.103798) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yaparla A, Popovic M, Grayfer L. 2018. Differentiation-dependent antiviral capacities of amphibian (Xenopus laevis) macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 1736-1744. ( 10.1074/jbc.M117.794065) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popovic M, Yaparla A, Paquin-Proulx D, Koubourli DV, Webb R, Firmani M, Grayfer L. et al. 2019. Colony-stimulating factor-1- and interleukin-34-derived macrophages differ in their susceptibility to Mycobacterium marinum. J. Leukoc. Biol. 106, 1257-1269. ( 10.1002/JLB.1A0919-147R) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paquin-Proulx D, Greenspun BC, Kitchen SM, Saraiva Raposo RA, Nixon DF, Grayfer L. 2018. Human interleukin-34-derived macrophages have increased resistance to HIV-1 infection. Cytokine 111, 272-277. ( 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.09.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hossainey MRH, Yaparla A, Hauser K, Moore T, Grayfer L. 2021. The roles of amphibian (Xenopus laevis) macrophages during chronic Frog Virus 3 infections. Viruses 13, 2299-2313. ( 10.3390/v13112299) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aibar S, et al. 2017. SCENIC: single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering. Nat. Methods 14, 1083-1086. ( 10.1038/nmeth.4463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edholm ES, Banach M, Hyoe Rhoo K, Pavelka MS Jr, Robert J. 2018. Distinct MHC class I-like interacting invariant T cell lineage at the forefront of mycobacterial immunity uncovered in Xenopus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E4023-E4031. ( 10.1073/pnas.1722129115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhoo KH, Edholm ES, Forzan MJ, Khan A, Waddle AW, Pavelka MS Jr, Robert J. 2019. Distinct host-mycobacterial pathogen interactions between resistant adult and tolerant tadpole life stages of Xenopus laevis. J. Immunol. 203, 2679-2688. ( 10.4049/jimmunol.1900459) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grayfer L, De Jesus Andino F, Robert J. 2015. Prominent amphibian (Xenopus laevis) tadpole type III interferon response to the frog virus 3 ranavirus. J. Virol. 89, 5072-5082. ( 10.1128/JVI.00051-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hauser K, Singer J, Hossainey MRH, Moore T, Wendel ES, Yaparla A, Kalia N, Grayfer L. 2021. Amphibian (Xenopus laevis) tadpoles and adult frogs differ in their antiviral responses to intestinal Frog Virus 3 infections. Front. Immunol. 12, 737403. ( 10.3389/fimmu.2021.737403) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wendel ES, Yaparla A, Koubourli DV, Grayfer L. 2017. Amphibian (Xenopus laevis) tadpoles and adult frogs mount distinct interferon responses to the Frog Virus 3 ranavirus. Virology 503, 12-20. ( 10.1016/j.virol.2017.01.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Dai J, Singh S. 2008. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and type I IFN: 50 years of convergent history. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 19, 3-19. ( 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.10.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mildner A, et al. 2013. Mononuclear phagocyte miRNome analysis identifies miR-142 as critical regulator of murine dendritic cell homeostasis. Blood 121, 1016-1027. ( 10.1182/blood-2012-07-445999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plantinga M, et al. 2013. Conventional and monocyte-derived CD11b(+) dendritic cells initiate and maintain T helper 2 cell-mediated immunity to house dust mite allergen. Immunity 38, 322-335. ( 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Sousa JR, Da Costa Vasconcelos PF, Quaresma JAS. 2019. Functional aspects, phenotypic heterogeneity, and tissue immune response of macrophages in infectious diseases. Infect Drug Resist. 12, 2589-2611. ( 10.2147/IDR.S208576) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lan HY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Atkins RC. 1993. Trafficking of inflammatory macrophages from the kidney to draining lymph nodes during experimental glomerulonephritis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 92, 336-341. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb03401.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato K, Imai Y, Irimura T. 1998. Contribution of dermal macrophage trafficking in the sensitization phase of contact hypersensitivity. J. Immunol. 161, 6835-6844. ( 10.4049/jimmunol.161.12.6835) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robert J, Ohta Y. 2009. Comparative and developmental study of the immune system in Xenopus. Dev. Dyn. 238, 1249-1270. ( 10.1002/dvdy.21891) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neely HR, Guo J, Flowers EM, Criscitiello MF, Flajnik MF. 2018. "Double-duty" conventional dendritic cells in the amphibian Xenopus as the prototype for antigen presentation to B cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 48, 430-440. ( 10.1002/eji.201747260) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grayfer L, Robert J. 2013. Colony-stimulating factor-1-responsive macrophage precursors reside in the amphibian (Xenopus laevis) bone marrow rather than the hematopoietic subcapsular liver. J. Innate Immun. 5, 531-542. ( 10.1159/000346928) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrero C, Sebastian C, Marques L, Comalada M, Xaus J, Valledor AF, Lloberas J, Celada A. 2002. Immunosenescence of macrophages: reduced MHC class II gene expression. Exp. Gerontol. 37, 389-394. ( 10.1016/S0531-5565(01)00205-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xaus J, Comalada M, Barrachina M, Herrero C, Gonalons E, Soler C, Lloberas J, Celada A. 2000. The expression of MHC class II genes in macrophages is cell cycle dependent. J. Immunol. 165, 6364-6371. ( 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6364) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.N'Diaye M, Warnecke A, Flytzani S, Abdelmagid N, Ruhrmann S, Olsson T, Jagodic M, Harris RA, Guerreiro-Cacais AO. 2016. Rat bone marrow-derived dendritic cells generated with GM-CSF/IL-4 or FLT3L exhibit distinct phenotypical and functional characteristics. J. Leukoc. Biol. 99, 437-446. ( 10.1189/jlb.1AB0914-433RR) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sichien D, Lambrecht BN, Guilliams M, Scott CL. 2017. Development of conventional dendritic cells: from common bone marrow progenitors to multiple subsets in peripheral tissues. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 831-844. ( 10.1038/mi.2017.8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maraskovsky E, Brasel K, Teepe M, Roux ER, Lyman SD, Shortman K, Mckenna HJ. et al. 1996. Dramatic increase in the numbers of functionally mature dendritic cells in Flt3 ligand-treated mice: multiple dendritic cell subpopulations identified. J. Exp. Med. 184, 1953-1962. ( 10.1084/jem.184.5.1953) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grayfer L, Robert J. 2016. Amphibian macrophage development and antiviral defenses. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 58, 60-67. ( 10.1016/j.dci.2015.12.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dress RJ, Ginhoux F. 2021. Monocytes and macrophages in severe COVID-19 - friend, foe or both? Immunol. Cell Biol. 99, 561-564. ( 10.1111/imcb.12464) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Percivalle E, et al. 2021. Macrophages and monocytes: "Trojan Horses" in COVID-19. Viruses 13, 2178. ( 10.3390/v13112178) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramsey JP, Reinert LK, Harper LK, Woodhams DC, Rollins-Smith LA. 2010. Immune defenses against Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a fungus linked to global amphibian declines, in the South African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis. Infect. Immun. 78, 3981-3992. ( 10.1128/IAI.00402-10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chinchar VG, Bryan L, Wang J, Long S, Chinchar GD. 2003. Induction of apoptosis in frog virus 3-infected cells. Virology 306, 303-312. ( 10.1016/S0042-6822(02)00039-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flajnik MF, Du Pasquier L. 1988. MHC class I antigens as surface markers of adult erythrocytes during the metamorphosis of Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 128, 198-206. ( 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90282-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flajnik MF, Kaufman JF, Hsu E, Manes M, Parisot R, Du Pasquier L. 1986. Major histocompatibility complex-encoded class I molecules are absent in immunologically competent Xenopus before metamorphosis. J. Immunol. 137, 3891-3899. ( 10.4049/jimmunol.137.12.3891) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Du Pasquier L, Flajnik MF. 1990. Expression of MHC class II antigens during Xenopus development. Dev. Immunol. 1, 85-95. ( 10.1155/1990/67913) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flajnik MF, Ferrone S, Cohen N, Du Pasquier L. 1990. Evolution of the MHC: antigenicity and unusual tissue distribution of Xenopus (frog) class II molecules. Mol. Immunol. 27, 451-462. ( 10.1016/0161-5890(90)90170-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hossainey MRH, Hauser KA, Garvey CN, Kalia N, Garvey JM, Grayfer L. 2023. A perspective into the relationships between amphibian (Xenopus laevis) myeloid cell subsets. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6631150) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Hossainey MRH, Hauser KA, Garvey CN, Kalia N, Garvey JM, Grayfer L. 2023. A perspective into the relationships between amphibian (Xenopus laevis) myeloid cell subsets. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6631150) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

All animals were purchased from the Xenopus 1 (Dexter, MI, USA) and reared in-house under strict laboratory conditions in accordance with IACUC regulations (approval number 15-024).

The data are provided in the electronic supplementary material [60].