Abstract

Targeting structured RNA elements in the SARS-CoV-2 viral genome with small molecules is an attractive strategy for pharmacological control over viral replication. In this work, we report the discovery of small molecules that target the frameshifting element (FSE) in the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome using high-throughput small-molecule microarray (SMM) screening. A new class of aminoquinazoline ligands for the SARS-CoV-2 FSE are synthesized and characterized using multiple orthogonal biophysical assays and structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies. This work reveals compounds with mid-micromolar binding affinity (KD = 60 ± 6 μM) to the FSE RNA and supports a binding mode distinct from previously reported FSE binders MTDB and merafloxacin. In addition, compounds are active in in vitro dual-luciferase and in-cell dual-fluorescent-reporter frameshifting assays, highlighting the promise of targeting structured elements of RNAs with druglike compounds to alter expression of viral proteins.

Keywords: Frameshifting, SARS-CoV-2, RNA, small-molecule microarrays

Over 14.83 million deaths are attributed to infection with COVID-19, a respiratory illness caused by the SARS-CoV-2 RNA virus.1 When the COVID-19 pandemic began, researchers scrambled to develop vaccines and other treatments to mitigate infections. Lopinavir/ritonavir, remdesivir, and several other broad-spectrum antivirals were initially pursued due to their efficacy against a wide range of viral pathogens.2,3 The clinical success of paxlovid, coupled with a lack of alternative therapies, led to it receiving emergency fast-track approval from the FDA, although concerns have been raised.4−6 Despite the success of the newly approved drugs as well as widespread adoption of mRNA-based vaccines, novel therapeutics are still needed.

The SARS-CoV-2 genome comprises ∼30 kilobases (kB) of single-stranded RNA that encode 29 proteins.7,8 Computational and experimental investigation has identified numerous highly conserved structural elements that drive processes required for viral replication.9 For example, the stem-loop II-like motif (s2m) is a small hairpin that plays an essential role in viral infection10,11 and has been targeted extensively with oligos, small molecules, fragments, etc.12−14 Another highly conserved element that has garnered substantial interest is the frameshifting element (FSE), which shifts the ribosomal reading frame in the 5′ direction by one nucleotide to maintain a precise stoichiometric ratio of viral proteins translated.15 The FSE contains three key motifs: (1) a 5′ slippery site that allows the ribosome to change reading frames when the ribosome is stalled, (2) a short linker sequence that plays a role in determining the extent of frameshifting, and (3) a downstream pseudoknot that impedes ribosomal translation to promote programmed −1 ribosomal frameshifting (−1 PRF).16,17 Mutations and small molecules that affect −1 PRF efficiency have been shown to decrease viral replication and reduce infectivity in HIV-1 as well as in coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.18−20 Structures of the SARS-CoV-2 FSE pseudoknot have been determined by cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography.21,22 However, structure-probing studies also indicate that alternative conformations of this RNA may be relevant in different sequence contexts, in which long-range contacts may be important for one biologically relevant conformation. As viral FSEs are mechanistically validated and highly attractive targets for small molecules, several laboratories have pursued inhibitors of this important RNA element by either direct binding or targeted RNA degradation.23−25

To discover small molecules that bind to the SARS-CoV-2 FSE, we performed a small-molecule microarray (SMM) screen using a fluorescently tagged FSE construct. A total of ∼40,000 compounds from commercial libraries were printed as high-density microarrays on glass slides as previously described (Figure 1A).26,27 We observed that many hits presented characteristic RNA-binding scaffolds such as quinazoline, benzoxazole, and 1,3,4-oxadiazole (Table S1), consistent with our recent efforts to characterize nucleic acid-binding chemotypes.28 Binding selectivity of each hit was evaluated by comparing the observed Z-scores to those of previous SMM screens against 30 different nucleic acid targets (including 13 RNA hairpin/pseudoknot structures, 7 DNA G-quadruplexes, and 10 RNA G-quadruplexes). Compound 1 was a hit only for the SARS-CoV-2 FSE RNA, suggesting a high degree of selectivity (Figure 1C). From this initial screen, 39 hit compounds (hit rate: 0.08%) were identified as binding to the FSE RNA with good selectivity.

Figure 1.

(A) Scheme of SARS-CoV-2 FSE RNA screening using SMM technology. (B) Representative hit 1 from SMM and the corresponding fluorescent images. (C) Selectivity profiling (Z-score) of 1 on SMM for 30 different nucleic acid targets screened by SMM. Z-score > 3 (dotted line) was considered as binding. (D) Binding validation of 1 by waterLOGSY.

Binding of hit compounds to the FSE was next validated using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Each compound was injected at 100 μM into the SPR chip with immobilized FSE RNA. From this analysis, 15 of 39 hit compounds showed binding. Among these, we further focused on compounds 1–3 due to their similar structures (Figure 1B and Table S1) and the observations that quinazolines had been found to interfere with SARS-CoV-2 RNA synthesis and bind other RNA elements.23,29 Next, we used water ligand observed gradient spectroscopy (waterLOGSY) to confirm that compounds bind to unlabeled RNA in solution without aggregating. Here, the waterLOGSY spectrum for 1 (150 μM) alone showed negative peaks, while the spectrum showed the opposite phase in the presence of 5 μM RNA (Figure 1D). N-Methyl-l-valine was used as an internal, nonbinding control and exhibited negative signals throughout the experiment. In contrast to 1, compounds 2 and 3 did not provide usable data in this experiment, potentially due to weak binding and/or aggregation. Taken together, these experiments demonstrated that compound 1 could be used as a good candidate for further RNA binding studies.

Next, the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) of compound 1 with the SARS-CoV-2 RNA was measured by both SPR and microscale thermophoresis (MST). For SPR experiments, the 5′-biotin-labeled SARS-CoV-2 FSE RNA was immobilized on a streptavidin-coated surface. Compound 1 was injected at concentrations ranging from 15.6 to 1000 μM, and a saturable, dose-dependent response was observed. The binding stoichiometry was estimated to be 1:1 by calculating the Rmax and molecular ratio.30 By fitting the response to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model, the KD was measured to be 147 ± 56 μM (Figure 2A). An MST titration with 5′-Cy5-RNA was also performed. In presence of compound 1 in a range of 4.9–500 μM, the MST curves showed negative shifts with increasing concentration. The fitted T-jump curve showed a KD value of 139 ± 80 μM, consistent with SPR results (Figure 2B). Compounds 2 and 3 were also investigated by MST but exhibited aggregation at concentrations above 50 μM (Figure S1). Taken together with findings from waterLOGSY assays, these results led us to focus on compound 1.

Figure 2.

Affinity measurement of binding between 1 and SARS-CoV-2 FSE RNA. (A) SPR compound titrations (left) and steady-state fitting (right). (B) MST compound titrations into Cy5-labeled RNA solution (left) and concentration-dependent curve fitting based on T-jump values (right).

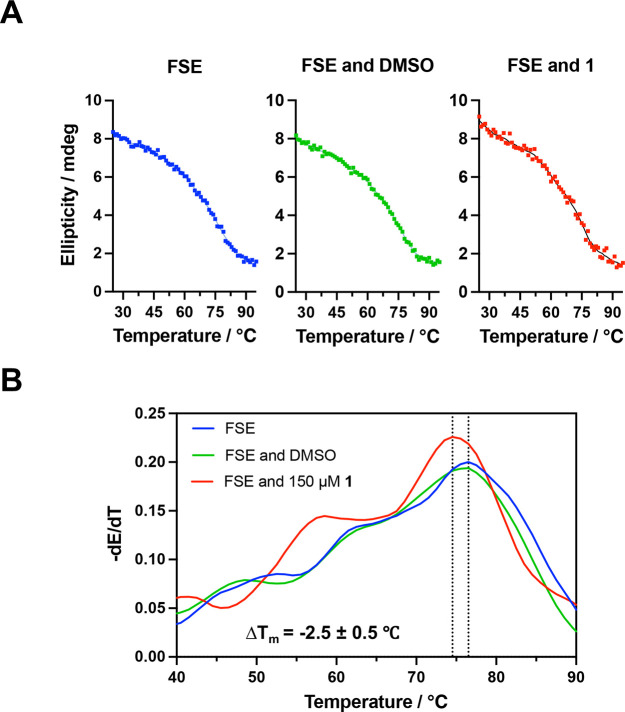

Next, we compared compound 1 to two other compounds reported to bind the SARS-CoV-2 FSE, merafloxacin and MTDB.16,25 The melting temperature (Tm) of the RNA was measured in the presence or absence of 1 by circular dichroism (CD) (Figure 3A). During RNA melting, two unfolding transitions were observed, indicating a complex unfolding pathway consistent with a previous study.20 A major peak appearing at 76.5 °C was observed, indicating complete unfolding of the pseudoknot, which was not significantly affected by addition of 5% DMSO. In the presence of 150 μM compound 1, the major peak shifted, exhibiting a ΔTm of −2.5 ± 0.5 °C (Figure 3B), and a more profound effect was observed in the presence of 500 μM 1 (ΔTm = −4.5 ± 0.5 °C) (Figure S2). In contrast, MTDB had a stabilizing effect on the thermal stability of SARS-CoV-2 FSE RNA (ΔTm = 2.2 ± 0.5 °C), which was also observed previously for the SARS-CoV pseudoknot.31 In contrast, merafloxacin, another previously reported FSE-binding control compound,25 decreased the Tm of the FSE (ΔTm = −3.7 ± 0.5 °C) (Figure S3). These results suggest that 1 and merafloxacin may have different modes of interaction with the FSE RNA compared to MTDB.

Figure 3.

Thermal stability of FSE RNA in the presence and absence of compound 1. (A) CD melting curves (260 nm peak) of the RNA incubated with/without 1. (B) Tm measurement using first derivative curves of data in (A).

MST titration experiments next tested compound 1, MTDB, and merafloxacin. For MTDB, the overall fluorescence was enhanced with increasing ligand concentration, while the fluorescence remained stable during the titrations of compound 1 or merafloxacin (Figure S4). Therefore, we conclude that the effects of these three FSE-binding compounds on FSE stability might vary due to distinct binding modes.

To evaluate the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of the hit compound 1, a series of quinazoline-based derivatives of 1 were synthesized. Twenty-four analogues were designed to explore the effects of altering chemical substituents around the core quinazoline ring on binding affinity to the FSE pseudoknot. Three key sites of substitutions were investigated: (1) substitution on the phenyl ring at position 2 of the heteroaromatic core, (2) substitution at positions 5, 6, 7, and 8 of the core, and (3) alkylamino substitution at position 4 of the core (see Table 1). The focused library was synthesized from readily available starting reagents via a three-step sequential reaction (Scheme 1). Substituted anthranilamides were reacted with derivatized aldehydes in the presence of I2 under reflux conditions. The resulting quinazolinones were further treated with phosphorus oxychloride under reflux condition for 4 h. After subsequent workup, the obtained chloroquinazolines were reacted with aliphatic amines in an SNAr fashion to yield the desired quinazolines in moderate overall yields (Scheme 1).

Table 1. SAR Study of the Lead Compound 1.

SPR screening was performed using 100 μM compound solution. A compound with binding signal greater than that of the lead compound was considered as a hit.

MST screening was carried out using 100 μM compound solution. A compound with MST shift greater than 3SD of DMSO signal (out of the dotted line region) was considered as a hit.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Quinazoline Derivatives of Compound 1 for SAR Study.

Binding activities were assayed via SPR and MST at 100 μM using the lead compound 1 as a positive control (Figures S5 and S6). Compounds demonstrating equal or greater binding response than the positive control in both SPR and MST experiments were considered hits, which resulted in five analogues (10, 13, 16, 22, and 24) to follow up (Table 1). It suggested that substitution on R1 impeded binding, as no binding was observed via MST, and only compounds 5 and 6 showed comparable binding in SPR. Furthermore, aliphatic amino substitutions on R3 showed little to no improvement in binding affinity compared to the control, though binding was observed with compound 24. In contrast, substitution at position 5, 6, 7, or 8 (R2) of the quinazoline core was more successful. Substituents at positions 6 and 7 showed the most promise, as compounds 10, 13, 16, and 22 afforded greater binding signals than the control in both single-concentration SPR and MST experiments. The most promising of these, compound 13, yielded an improved KD of 60 ± 6 μM measured by SPR, demonstrating a saturable dose-dependent response (Figure S7).

To investigate the effects of small molecules on −1 PRF efficiency, we performed in vitro dual-luciferase reporter assays. Compounds (1, 13, MTDB, and merafloxacin) were added to rabbit reticulocyte lysate translation reactions of either the SARS-CoV-2 or Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) frameshifting pseudoknot (Table 2). The RSV frameshifting element is a complex pseudoknot from an avian retrovirus and has no structural or sequence similarity to coronaviral frameshifting elements.32 In these assays, the frameshifting pseudoknot sequences are placed between Renilla and firefly luciferases in the 0 and −1 frames, respectively, allowing frameshifting to be determined from the ratio of their luminescence. In addition, total translation was reported by considering only Renilla luciferase, which was noisier due to the lack of a second in-well luminescence measurement (Table 2). For both frameshifting and translation, values reported were normalized to wild-type (WT) values in the presence of DMSO to account for its presence in compound stocks.

Table 2. In Vitro Frameshifting Assays.

| SARS-CoV-2 |

RSV |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Frameshifting | Translation | Frameshifting | Translation |

| WT | 0.99 ± 0.02 | 1.11 ± 0.14 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 1.09 ± 0.11 |

| WT + DMSO | 1.00 ± 0.00a | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 |

| 5′ controlb | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 1.05 ± 0.24 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.98 ± 0.14 |

| 3′ control | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.97 ± 0.29 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.61 ± 0.35 |

| SF control | 1.24 ± 0.05 | 1.20 ± 0.32 | 4.69 ± 0.62 | 0.94 ± 0.20 |

| WT + MTDB | 1.02 ± 0.04 | 1.01 ± 0.20 | 1.13 ± 0.04 | 0.96 ± 0.13 |

| WT + 1 | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 1.35 ± 0.23 | 1.21 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.01 |

| WT + 13 | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.14 | 1.13 ± 0.03 | 0.82 ± 0.01 |

| WT + Merafloxacin | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.07 | 0.59 ± 0.21 | 0.70 ± 0.07 |

Frameshifting and translation are reported normalized to values obtained for the WT frameshifting pseudoknot sequences in the presence of DMSO (see Supplementary Methods). Values are reported as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Controls include a stop codon placed 5′ to the pseudoknot sequence (5′ control), a stop codon placed 3′ to the pseudoknot sequence (3′ control), and the two luciferases placed in the same frame (SF control).

For compounds 1, 13, and MTDB, frameshifting efficiencies were largely unchanged for SARS-CoV-2 and RSV reporters (Table 2). In contrast, merafloxacin reduced frameshifting by 79% for SARS-CoV-2 (0.21 ± 0.01) and 41% for RSV (0.59 ± 0.21). However, translation was reduced by 30% for the RSV reporter, indicating that this compound might inhibit translation in addition to modulating frameshifting for both reporters at these concentrations. Meanwhile, compounds 1 and 13 were also found to modestly affect the translation of viral frameshifting constructs, suggesting that these compounds could potentially impact in vitro translation as well.

In-cell frameshifting assays employed a WT plasmid containing the SARS-CoV-2 FSE between mCherry and GFP. As a negative control, second plasmid features a stop codon between the mCherry and the slippery sequence that abolishes the GFP. As a positive control, a plasmid lacking the FSE (no FSE plasmid) was used, in which an in-frame GFP is translated constitutively. MCF-7 cells were treated with compounds 1 and 13 at various concentrations and transfected with the three reporter plasmids. As shown in Figure 4A, dose-dependent inhibition of GFP expression of the WT plasmid in the presence of compound 1 indicated that it inhibited −1 PRF in cells. No GFP inhibition was observed for 1 with the control lacking an FSE. Additionally, the improved analogue (compound 13) showed ∼50% inhibition of −1 PRF at 50 μM (Figure 4B). Importantly, this ∼2-fold improvement in cellular potency agrees well with the observed increase in binding affinity of 13 to the FSE in biophysical studies. In the same assay, merafloxacin inhibited −1 PRF in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 33.5 ± 7.3 μM, in good agreement with published results (Figure 4C).25 However, the dissociation constant between merafloxacin and FSE RNA could not be determined by SPR or MST (Figure S8). This could indicate a stoichiometry of binding greater than 1:1 or an alternative mechanism of action. MTDB was not assayed in this experiment, as it was previously reported to have no effect on FSE in this reporter assay.17

Figure 4.

Effect of compounds 1, 13, and merafloxacin on SARS-CoV-2 −1 PRF in cells. (A) Dose-dependent inhibition of compound 1 on SARS-CoV-2 frameshifting reporters for the WT and FSE-lacking (no FSE) plasmids in MCF-7 cells. (B) Dose-dependent inhibition of compound 13. (C) Dose-dependent inhibition of merafloxacin. The results are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3) of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis is relative to DMSO control (0 μM). (D) Cytotoxicity results for compounds 1, 13, and merafloxacin in MCF-7 cells after 48 h. *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.0005.

To be effective inhibitors, compounds 1 and 13 must also be nontoxic to human cells, which was assessed via a viability assay. Both compounds had minimal impact on MCF-7 cell viability at the concentrations used in the cell-based fluorescent reporter assay, while merafloxacin as a control did not decrease cell viability (Figure 4D). The tighter binder 13 was slightly more toxic to cells, but neither compound showed a significant impact on viability at 50 μM (91.6% and 95.6% remaining, respectively).

In summary, we used SMM screening to identify ligands for the SARS-CoV-2 FSE pseudoknot. We utilized multiple orthogonal biophysical analyses to validate the interaction of hit molecules with the RNA and measured KD values in the mid-micromolar range for the best hits. Preparation of several diverse analogues revealed a structure–activity relationship that resulted in the discovery of improved analogue 13. Together, these analyses demonstrated that these compounds bind to the RNA in a saturable, reversible interaction despite having modest affinities. Analysis of thermal melt data revealed a complex, multistate unfolding pathway for the FSE pseudoknot. MTDB, merafloxacin, and new ligands have diverse modes of interacting with the FSE RNA, and further study will be required to reveal the molecular basis of these interactions.

Evaluation of both the initial hit 1 in in vitro frameshifting assays and both 1 and 13 in cell-based frameshifting assays revealed that both compounds have FSE-dependent effects on gene output. In the in vitro dual-luciferase-based reporter system, 1 showed effects on translation but not frameshifting. Similarly, MTDB did not affect frameshifting or translation, consistent with a previous report.17 Merafloxicin reduced frameshifting for both the SARS-CoV-2 and RSV reporter constructs. In contrast, using a dual-fluorescent-protein reporter system in live cells, 1 and 13 reduced frameshifting and had no effects on negative control reporters lacking the FSE, similar to merafloxacin.

The complex behavior of these compounds in diverse reporter systems highlights the challenges of using and interpreting results from frameshifting reporters. In vitro assays are more focused tests for frameshifting inhibition, and in-cell assays report on additional translational effects that manifest as frameshifting modulation, as illustrated by many classes of compounds that modulate frameshifting.33 Previous studies demonstrated that the SARS-CoV-2 FSE adopts a pseudoknot conformation in isolation, enabling X-ray crystal structure determination.22 In contrast, high-throughput structure-probing studies revealed that the FSE adopts a complex conformational ensemble in the context of the entire SARS-CoV-2 genome.34−36 Analysis of long-range RNA–RNA interactions suggested that the FSE makes contacts to distant sequences in a 1.5 kB window,37 which is not represented in either of the reporter constructs used here. Despite the limitations of these model systems, compounds that bind to the FSE can clearly function by multiple complex mechanisms of action, including modulating frameshifting and impacting translation. The reliance of betacoronaviruses on discrete, functional, highly conserved RNA structures, such as the s2m and FSE, indicates these elements as potential targets for the development of small-molecule inhibitors of these viruses. Targeting RNA structures in a currently known virus could inform the development of a new line of defense against future outbreaks, for example by developing panviral frameshifting inhibitors. Here we have identified a new class of small molecules that bind to the FSE and modulate frameshifting in cells. Future work on these and other compounds to determine their binding modes and mechanisms of action will broadly advance the goal of developing anticoronaviral small molecules targeting viral RNA motifs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (NCI), Center for Cancer Research, Projects BC011585 07 and BC011970 02 (PI, J.S.S.), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (A.R.F.-D.), and awards from the NIH Intramural Targeted Anti-COVID-19 (ITAC) Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (A.R.F.-D., S.F.J.L.G., and J.S.S.). C.P.J. is the recipient of a K22 Career Transition Award from the NHLBI. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The authors thank the members from biophysics resource (Dr. Sergey G. Tarasov and Marzena Dyba) for helpful comments and suggestions on biophysical experiments. We thank Dr. Joel P. Schneider from NCI/CBL for providing SPR instrument.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- FSE

frameshifting element

- SMM

small-molecule microarray

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- –1 PRF

programmed −1 ribosomal frameshifting

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- MST

microscale thermophoresis

- waterLOGSY

water ligand observed gradient spectroscopy

- CD

circular dichroism

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00051.

Experimental details and procedures, biophysical and biological assays, and NMR spectral data for all new compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Conceived and designed experiments: J.S.S., M.Y., F.P.O., C.R., S.B., K.D.-D., S.S., and C.P.J. Designed compounds or contributed to synthetic route design: J.S.S., F.P.O., and X.L. Analyzed data: M.Y., F.P.O., C.R., S.B., and C.P.J. Wrote/edited paper: J.S.S., M.Y., F.P.O., C.R., S.B., C.P.J., S.F.J.L.G., and A.R.F.-D.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Msemburi W.; Karlinsky A.; Knutson V.; Aleshin-Guendel S.; Chatterji S.; Wakefield J. The WHO estimates of excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 2023, 613 (7942), 130–137. 10.1038/s41586-022-05522-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qomara W. F.; Primanissa D. N.; Amalia S. H.; Purwadi F. V.; Zakiyah N. Effectiveness of Remdesivir, Lopinavir/Ritonavir, and Favipiravir for COVID-19 Treatment: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 8557–8571. 10.2147/IJGM.S332458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciorowski D.; El Idrissi S. Z.; Gupta Y.; Medernach B. J.; Burns M. B.; Becker D. P.; Durvasula R.; Kempaiah P. A Review of the Preclinical and Clinical Efficacy of Remdesivir, Hydroxychloroquine, and Lopinavir-Ritonavir Treatments against COVID-19. SLAS Discovery 2020, 25 (10), 1108–1122. 10.1177/2472555220958385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen W.; Chen C.; Tang J.; Wang C.; Zhou M.; Cheng Y.; Zhou X.; Wu Q.; Zhang X.; Feng Z.; Wang M.; Mao Q. Efficacy and safety of three new oral antiviral treatment (molnupiravir, fluvoxamine and Paxlovid) for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2022, 54 (1), 516–523. 10.1080/07853890.2022.2034936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzi M.; Vakil M. K.; Bahmanyar M.; Zarenezhad E. Paxlovid: Mechanism of Action, Synthesis, and In Silico Study. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 7341493. 10.1155/2022/7341493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. From Positive to Negative to Positive Again-The Mystery of Why COVID-19 Rebounds in Some Patients Who Take Paxlovid. JAMA 2022, 327 (24), 2380–2382. 10.1001/jama.2022.9925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.; Rao Z. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19 (11), 685–700. 10.1038/s41579-021-00630-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R. J.; O’Leary C. A.; Tompkins V. S.; Peterson J. M.; Haniff H. S.; Williams C.; Disney M. D.; Moss W. N. A map of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA structurome. NAR: Genomics Bioinf. 2021, 3 (2), lqab043. 10.1093/nargab/lqab043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khailany R. A.; Safdar M.; Ozaslan M. Genomic characterization of a novel SARS-CoV-2. Gene Rep. 2020, 19, 100682. 10.1016/j.genrep.2020.100682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C.; Cai Z.; Xiao X.; Rao J.; Chen J.; Hu N.; Yang M.; Xing X.; Wang Y.; Li M.; Zhou B.; Wang X.; Wang J.; Xue Y. The architecture of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome inside virion. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12 (1), 3917. 10.1038/s41467-021-22785-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangan R.; Watkins A. M.; Chacon J.; Kretsch R.; Kladwang W.; Zheludev I. N.; Townley J.; Rynge M.; Thain G.; Das R. De novo 3D models of SARS-CoV-2 RNA elements from consensus experimental secondary structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49 (6), 3092–3108. 10.1093/nar/gkab119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lulla V.; Wandel M. P.; Bandyra K. J.; Ulferts R.; Wu M.; Dendooven T.; Yang X.; Doyle N.; Oerum S.; Beale R.; O’Rourke S. M.; Randow F.; Maier H. J.; Scott W.; Ding Y.; Firth A. E.; Bloznelyte K.; Luisi B. F. Targeting the Conserved Stem Loop 2 Motif in the SARS-CoV-2 Genome. J. Virol. 2021, 95 (14), e00663-21 10.1128/JVI.00663-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Sczepanski J. T. Targeting a conserved structural element from the SARS-CoV-2 genome using l-DNA aptamers. RSC Chem. Biol. 2022, 3 (1), 79–84. 10.1039/D1CB00172H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramulu S.; Richter C.; Berg H.; Wirtz Martin M. A.; Ceylan B.; Matzel T.; Adam J.; Altincekic N.; Azzaoui K.; Bains J. K.; Blommers M. J. J.; Ferner J.; Furtig B.; Gobel M.; Grun J. T.; Hengesbach M.; Hohmann K. F.; Hymon D.; Knezic B.; Martins J. N.; Mertinkus K. R.; Niesteruk A.; Peter S. A.; Pyper D. J.; Qureshi N. S.; Scheffer U.; Schlundt A.; Schnieders R.; Stirnal E.; Sudakov A.; Troster A.; Vogele J.; Wacker A.; Weigand J. E.; Wirmer-Bartoschek J.; Wohnert J.; Schwalbe H. Exploring the Druggability of Conserved RNA Regulatory Elements in the SARS-CoV-2 Genome. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (35), 19191–19200. 10.1002/anie.202103693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlick T.; Zhu Q.; Dey A.; Jain S.; Yan S.; Laederach A. To Knot or Not to Knot: Multiple Conformations of the SARS-CoV-2 Frameshifting RNA Element. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (30), 11404–11422. 10.1021/jacs.1c03003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J. A.; Olson A. N.; Neupane K.; Munshi S.; San Emeterio J.; Pollack L.; Woodside M. T.; Dinman J. D. Structural and functional conservation of the programmed −1 ribosomal frameshift signal of SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295 (31), 10741–10748. 10.1074/jbc.AC120.013449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt P. R.; Scaiola A.; Loughran G.; Leibundgut M.; Kratzel A.; Meurs R.; Dreos R.; O’Connor K. M.; McMillan A.; Bode J. W.; Thiel V.; Gatfield D.; Atkins J. F.; Ban N. Structural basis of ribosomal frameshifting during translation of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. Science 2021, 372 (6548), 1306–1313. 10.1126/science.abf3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilimire T. A.; Chamberlain J. M.; Anokhina V.; Bennett R. P.; Swart O.; Myers J. R.; Ashton J. M.; Stewart R. A.; Featherston A. L.; Gates K.; Helms E. D.; Smith H. C.; Dewhurst S.; Miller B. L. HIV-1 Frameshift RNA-Targeted Triazoles Inhibit Propagation of Replication-Competent and Multi-Drug-Resistant HIV in Human Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12 (6), 1674–1682. 10.1021/acschembio.7b00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. J.; Kim Y. G.; Park H. J. Identification of RNA pseudoknot-binding ligand that inhibits the −1 ribosomal frameshifting of SARS-coronavirus by structure-based virtual screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (26), 10094–10100. 10.1021/ja1098325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupane K.; Munshi S.; Zhao M.; Ritchie D. B.; Ileperuma S. M.; Woodside M. T. Anti-Frameshifting Ligand Active against SARS Coronavirus-2 Is Resistant to Natural Mutations of the Frameshift-Stimulatory Pseudoknot. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432 (21), 5843–5847. 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; Zheludev I. N.; Hagey R. J.; Haslecker R.; Hou Y. J.; Kretsch R.; Pintilie G. D.; Rangan R.; Kladwang W.; Li S.; Wu M. T.; Pham E. A.; Bernardin-Souibgui C.; Baric R. S.; Sheahan T. P.; D’Souza V.; Glenn J. S.; Chiu W.; Das R. Cryo-EM and antisense targeting of the 28-kDa frameshift stimulation element from the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021, 28 (9), 747–754. 10.1038/s41594-021-00653-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. P.; Ferré-D’Amaré A. R. Crystal structure of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) frameshifting pseudoknot. RNA 2022, 28 (2), 239–249. 10.1261/rna.078825.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haniff H. S.; Tong Y.; Liu X.; Chen J. L.; Suresh B. M.; Andrews R. J.; Peterson J. M.; O’Leary C. A.; Benhamou R. I.; Moss W. N.; Disney M. D. Targeting the SARS-CoV-2 RNA Genome with Small Molecule Binders and Ribonuclease Targeting Chimera (RIBOTAC) Degraders. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6 (10), 1713–1721. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafferani M.; Haddad C.; Luo L.; Davila-Calderon J.; Chiu L. Y.; Mugisha C. S.; Monaghan A. G.; Kennedy A. A.; Yesselman J. D.; Gifford R. J.; Tai A. W.; Kutluay S. B.; Li M. L.; Brewer G.; Tolbert B. S.; Hargrove A. E. Amilorides inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro by targeting RNA structures. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7 (48), eabl6096 10.1126/sciadv.abl6096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Abriola L.; Niederer R. O.; Pedersen S. F.; Alfajaro M. M.; Silva Monteiro V.; Wilen C. B.; Ho Y.-C.; Gilbert W. V.; Surovtseva Y. V.; Lindenbach B. D.; Guo J. U. Restriction of SARS-CoV-2 replication by targeting programmed −1 ribosomal frameshifting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118 (26), e2023051118. 10.1073/pnas.2023051118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly C. M.; Abulwerdi F. A.; Schneekloth J. S. Jr Discovery of RNA Binding Small Molecules Using Small Molecule Microarrays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1518, 157–175. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6584-7_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M.; Carter S.; Parmar S.; Bume D. D.; Calabrese D. R.; Liang X.; Yazdani K.; Xu M.; Liu Z.; Thiele C. J.; Schneekloth J. S. Targeting a noncanonical, hairpin-containing G-quadruplex structure from the MYCN gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49 (14), 7856–7869. 10.1093/nar/gkab594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdani K.; Jordan D.; Yang M.; Fullenkamp C. R.; Calabrese D. R.; Boer R.; Hilimire T.; Allen T. E. H.; Khan R. T.; Schneekloth J. S. Machine Learning Informs RNA-Binding Chemical Space. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62 (11), e202211358. 10.1002/anie.202211358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J.; Zhang Y.; Wang M.; Liu Q.; Lei X.; Wu M.; Guo S.; Yi D.; Li Q.; Ma L.; Liu Z.; Guo F.; Wang J.; Li X.; Wang Y.; Cen S. Quinoline and Quinazoline Derivatives Inhibit Viral RNA Synthesis by SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7 (6), 1535–1544. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douzi B. Protein-Protein Interactions: Surface Plasmon Resonance. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1615, 257–275. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7033-9_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie D. B.; Soong J.; Sikkema W. K.; Woodside M. T. Anti-frameshifting ligand reduces the conformational plasticity of the SARS virus pseudoknot. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (6), 2196–9. 10.1021/ja410344b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T.; Madhani H. D.; Masiarz F. R.; Varmus H. E. Signals for ribosomal frameshifting in the Rous sarcoma virus gag-pol region. Cell 1988, 55 (3), 447–58. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90031-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi S.; Neupane K.; Ileperuma S. M.; Halma M. T. J.; Kelly J. A.; Halpern C. F.; Dinman J. D.; Loerch S.; Woodside M. T. Identifying Inhibitors of −1 Programmed Ribosomal Frameshifting in a Broad Spectrum of Coronaviruses. Viruses 2022, 14 (2), 177. 10.3390/v14020177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredonia I.; Nithin C.; Ponce-Salvatierra A.; Ghosh P.; Wirecki T. K.; Marinus T.; Ogando N. S.; Snijder E. J.; van Hemert M. J.; Bujnicki J. M.; Incarnato D. Genome-wide mapping of SARS-CoV-2 RNA structures identifies therapeutically-relevant elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48 (22), 12436–12452. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston N. C.; Wan H.; Strine M. S.; de Cesaris Araujo Tavares R.; Wilen C. B.; Pyle A. M. Comprehensive in vivo secondary structure of the SARS-CoV-2 genome reveals novel regulatory motifs and mechanisms. Mol. Cell 2021, 81 (3), 584–598. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan T. C. T.; Allan M. F.; Malsick L. E.; Woo J. Z.; Zhu C.; Zhang F.; Khandwala S.; Nyeo S. S. Y.; Sun Y.; Guo J. U.; Bathe M.; Naar A.; Griffiths A.; Rouskin S. Secondary structural ensembles of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome in infected cells. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13 (1), 1128. 10.1038/s41467-022-28603-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv O.; Price J.; Shalamova L.; Kamenova T.; Goodfellow I.; Weber F.; Miska E. A. The Short- and Long-Range RNA-RNA Interactome of SARS-CoV-2. Mol. Cell 2020, 80 (6), 1067–1077. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.