Abstract

This paper describes the DNA sequence of the photosynthesis region of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T. The photosynthesis gene cluster is located within a ~73 kb AseI genomic DNA fragment containing the puf, puhA, cycA and puc operons. A total of 65 open reading frames (ORFs) have been identified, of which 61 showed significant similarity to genes/proteins of other organisms while only four did not reveal any significant sequence similarity to any gene/protein sequences in the database. The data were compared with the corresponding genes/ORFs from a different strain of R.sphaeroides and Rhodobacter capsulatus, a close relative of R.sphaeroides. A detailed analysis of the gene organization in the photosynthesis region revealed a similar gene order in both species with some notable differences located to the pucBAC=cycA region. In addition, photosynthesis gene regulatory protein (PpsR, FNR, IHF) binding motifs in upstream sequences of a number of photosynthesis genes have been identified and shown to differ between these two species. The difference in gene organization relative to pucBAC and cycA suggests that this region originated independently of the photosynthesis gene cluster of R.sphaeroides.

INTRODUCTION

Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T is an extremely versatile facultative photoheterotroph belonging to the α-3 subgroup of the Proteobacteria (1). Rhodobacter sphaeroides is metabolically flexible and can grow aerobically, anaerobically with DMSO, photosynthetically in the light under anaerobic conditions and also fermentatively. Because of this multiplicity of growth modes there has been considerable interest in studying the regulation of photosynthesis gene expression (2–4) in R.sphaeroides and its close relative, Rhodobacter capsulatus. In the past, most of the essential genes involved in photosynthesis from both species have been identified and mapped to a single photosynthesis gene cluster (PGC) (5,6). An ~46 kb DNA region in R.capsulatus containing most of the photosynthesis genes has been sequenced (7), and DNA sequencing of the same region of R.sphaeroides has recently been undertaken in our laboratory (8–13, this study) as well as elsewhere (14–16). Recently an ~41 kb DNA sequence has been reported from a different strain of R.sphaeroides (16).

In this paper we present DNA sequence analysis of a contiguous ~67 kb DNA region comprising an expanded photosynthesis region of R.sphaeroides 2.4.1. Sixty-five open reading frames (ORFs) of 300 bp or longer were identified of which 61 exhibited strong matches to genes/orfs of related organisms, and only four ORFs do not show any significant homologies in the current database. In order to determine whether R.sphaeroides and R.capsulatus conserve the same linkage arrangement in the photosynthesis region, the sequence data obtained in this study as well as from another strain of R.sphaeroides (16) were compared with the sequence of the photosynthesis gene cluster from R.capsulatus (7).

The PGC contains many genes involved in bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis (bch), carotenoid biosynthesis (crt), light harvesting polypeptides (puc and puf), reaction center proteins (puhA, pufLM) and their regulators, ppsR, tspO and ppaA (M.Gomelsky and S.Kaplan, unpublished). Rhodobacter sphaeroides and R.capsulatus have a similar genetic organization in most of the photosynthesis region, but they differ in their genetic organization around pucBAC and cycA. Importantly, both species differ in the locations of many of their upstream regulatory sequences. The data presented here suggest that while conservation of the main PGC between these two species is maintained, possibly due to similar functional constraints which could impose limits on the genetic rearrangement in this region, this is not true for the region encompassing pucBAC and cycA. These differences in the context in which pucBAC and cycA are found suggests that these genes were not an integral part of the ‘original’ photosynthesis unit, and may have originated independently of the PGC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequencing strategy

The entire photosynthesis region spans somewhat more than five overlapping cosmids (pUI8711, pUI8714, pUI8626, pUI8461 and pUI8487) which have previously been identified from an ordered chromosome-specific cosmid collection (Choudhary and Kaplan, unpublished data). Cosmid inserts were digested with BamHI, EcoRI and PstI, and resulting DNA fragments were subcloned into a pBluescript vector (17). Cosmid and plasmid templates were prepared using Prep-A-Gene or Quantum prep kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) as described elsewhere (18). Plasmid subclones were sequenced from both ends using the universal T3 and Ext’-7 primers. Many of the photosynthesis genes and their regulators have previously been sequenced in our laboratory, and these sequences have been submitted earlier to the GenBank. All of these sequence ends were further used as anchors to fill in the remaining gaps using primer walking (19). The sequence data for this study was generated by the dideoxy termination method using a fluorescent based sequencing gel (Models 373 and 377, Applied Biosystems).

Sequence analysis

In a typical sequencing run ~600 nt were obtained. All sequence chromatograms were visually examined and ambiguous nucleotides were edited. Sequence files were then assembled using the Genetics Computer Group and Staden software packages. From the sequence data, all six possible reading frames were screened with the DNA strider program. The direction of transcription of the genes is based on starting codons ATG or GTG preceded by a putative Shine–Dalgarno sequence and alignment with the R.capsulatus photosynthesis gene cluster. For searching the DNA and protein databases we used the BLAST program (20) and the BLAST server at the National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI, Bethesda, MD).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The complete DNA sequence of the photosynthesis gene region of R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 was deposited into GenBank (NCBI) with the accession number AF195122. The DNA sequence is also available on our R.sphaeroides genome database (RsGDB) which can be accessed at http://www-mmg.med.uth. tmc.edu/sphaeroides/ (21).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

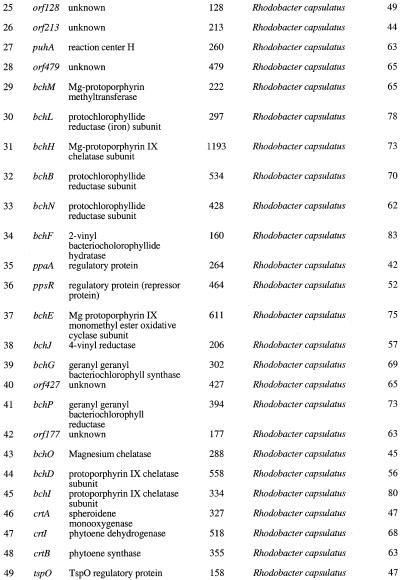

The complete photosynthesis region of R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 is contained within five overlapping cosmids. DNA sequencing of these cosmid inserts resulted in a single contiguous 66 280 nt sequence. The percentage G+C composition of this region was determined to be 68.6%. Figure 1 shows the physical and genetic map of the photosynthesis region of R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 and Table 1 summarizes the description of the ORFs, sizes of the polypeptides, their degree of amino acid similarity to their homologs and the name of the species to which they strongly match. We have identified a total of 65 ORFs of which 61 reveal strong database matches and only four have no homologies to any entry in the database (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Physical and genetic map of the photosynthesis gene cluster of R.sphaeroides 2.4.1. The number of orfs is shown from left to right. The arrows show the likely direction of the transcription of genes/orfs.

Table 1. Description of ORFs.

1The organisms shown had the strongest match after excluding R.sphaeroides. In the case of pufK, no other matches were found significant to any other species.

The sequence of R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 differs from the sequence of R.sphaeroides NCIB 8253 (16) at several locations mostly in nucleotide substitutions and these small changes may be due to strain differences. However, the gene organization in this region (puhA–puf) in both strains of R.sphaeroides remains identical. The cycA–pucBAC region has not been completely sequenced from R.sphaeroides NCIB 8253 and therefore is not available for sequence comparison over this whole region. The overall gene organization of the main PGC of R.sphaeroides is also similar to that of the closely related bacterium, R.capsulatus. A total of 41 genes/orfs (orf25–orf65, from left to right) of this region exhibit similar gene-linkage relationships in both species. All of these genes encode structural and regulatory functions: for example, genes encoding bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis (bch), carotenoid biosynthesis (crt), light harvesting complexes I (puf), reaction center protein (puhA, pufLM) and regulatory proteins (ppsR, ppaA, tspO). Most of these genes, if not all, are required for optimal photosynthetic growth of both organisms. In R.sphaeroides, the crt biosynthesis genes are clustered and are flanked by bch biosynthesis genes as in R.capsulatus (14). The bch biosynthesis genes are further surrounded by genes encoding reaction center proteins (puhA and the puf operon).

The gene organization in the pucBAC=cycA region in R.sphaeroides differs from those of R.capsualtus. All predicted Orfs in this region except orf4 and orf23 do not show strong matches to orfs surrounding these same genes in R.capsulatus (see Table 1), instead these Orfs strongly match to those of other organisms such as Sinorhizobium meliloti, Ralstonia eutropha, Brucella melitensis, Synechocystis, Paracoccus denitrificans, Rhodovulum sulfidophilum and Erythrobacter sp. The majority of these genes/orfs comprising the pucBAC–cycA region encode for several metabolic functions unrelated to photosynthesis such as, transport, urea metabolism and other regulators (see Table 1). It is surprising that six of the 24 Orfs in this region show strongest matches to Synechocystis, a member of the cyanobacteria, which is not considered closely related to R.sphaeroides. Also, within this region, four Orfs did not show any significant homologies in the current database.

There is only the puc operon in the pucBAC–cycA region which encodes for light harvesting complex II and is required for optimal photosynthetic growth in both species. cycA which encodes for the cytochrome c2 apoprotein is also required for photosynthetic growth, but only in R.sphaeroides (8). On the contrary, R.capsulatus lacking cyt c2 is reported to be able to grow photosynthetically and it is therefore not essential for photosynthesis (22). Further investigation is required as to whether the newly identified ORFs of unknown functions in this region are actually involved in photosynthetic growth of this bacterium.

Sequences surrounding pucBAC from these two species exhibit remarkable differences in their gene organization. In R.capsulatus, the puc operon is located outside of the main PGC and its exact location is not yet apparent (23). In R.sphaeroides, the puc operon is located ~20 kb apart from the main PGC and the gene organization surrounding the pucBAC region in R.sphaeroides differs from that of R.capsulatus. In R.capsulatus, pucBACDE exists in a single operon (23,24) whereas in R.sphaeroides pucDE has not been observed (9). The only available DNA sequence ~200 bp upstream and ~50 bp downstream of pucBAC from R.capsulatus shows no homology to the corresponding region of R.sphaeroides. In addition, the data from the ongoing genome sequencing project of R.capsulatus shows no sequence conservation outside the pucBAC region. Similarly, the sequence around cycA in these two species are quite different. The upstream and downstream sequences of cycA in R.sphaeroides (8) do not strongly match the corresponding region of R.capsulatus (22).

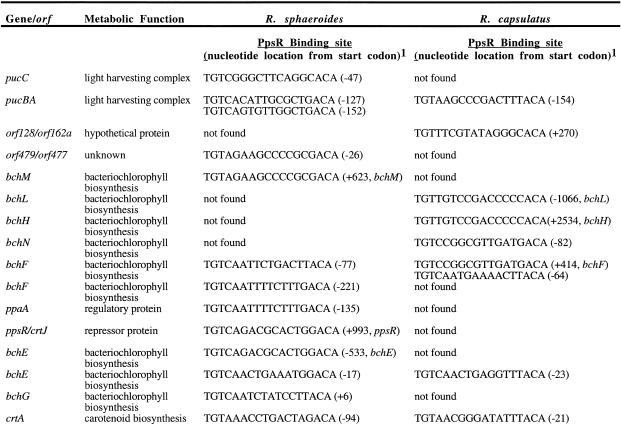

While the main PGC from R.sphaeroides and R.capsulatus reveal a great degree of similarity in genetic-linkage relationships, regulatory differences between these two species as listed in Table 2 are found in upstream sequences of a number of genes in this cluster. In R.sphaeroides, PpsR binding sites (TGT-N12-ACA) are present upstream of eight genes, including genes for Bchl biosynthesis (bchF, bchE, bchG, bchC), Crt biosynthesis (crtA, crtI, crtD, crtE), light harvesting complexes (pucC, pucBA) and also a regulator (ppaA). Additionally, PpsR binding motifs are also present within the coding sequences of bchM, bchG, bchZ and ppsR. Rhodobacter capsualtus contains the same dyad symmetry upstream of bchF, bchN, bchE, bchC, crtA, crtI, crtD and pucBAC, and also within the coding sequences of orf162b, bchH, bchF, bchZ and pufL. A number of PpsR binding sites located within the coding sequence of one gene are positioned in the upstream or regulatory region of yet another gene (see Table 2). The localization of this motif in the upstream sequences of photosynthesis genes was designated as a repressor binding site which probably results in the control of expression of these genes. Furthermore, PpsR has been shown to repress puc and bchF gene expression in R.sphaeroides (12), and was also shown to be expressed at approximately constant levels regardless of growth conditions (25). Therefore it is conceivable that, under aerobic growth conditions, the ppsR repressor binds to its motifs regardless of whether they are positioned upstream of, or within, the coding regions of genes. The genes involved in photosynthesis appear to be clustered into many transcriptional units, which suggests that the regulation of the first gene in the transcriptional unit may help ensure repression of these genes and/or downstream genes.

Table 2. PpsR, FnrL and IHF binding sites in the PGC.

1Nucleotide locations are relatively positioned from the start codon of the gene. + and – are designated for nucleotide position downstream from the start site in the coding sequence and in the upstream sequence of the gene, respectively. Some of the PpsR sites are listed twice. In R.sphaeroides: +623 in the bchM gene is the same as –26 upstream of orf479; –221 upstream of bchF is the same as –82 upstream of ppaA; +993 in the ppsR is the same as –533 upstream of bchE; –94 upstream of crtA is the same as –49 upstream of crtI; –82 upstream of crtD is the same as –73 upstream of crtI; +491 in the bchZ is the same as –965 upstream of pufQ. In R.capsulatus: –82 upstream of bchN is the same as +414 in the bchF; –21 upstream of crtA is the same as –120 upstream of crtI; –68 upstream of crtD is the same as –52 upstream of crtE; +2534 in the bchH is the same as –1066 upstream of bchL; +494 in the bchZ is the same as in –964 upstream of pufQ; +473 in the pufL is the same as –352 upstream of pufM.

The presence of the truncated FNR consensus binding sequence (TTGXX-N4-XXCAA) upstream of pucBAC and bchE in R.sphaeroides has been reported earlier (25), and it appears to be absent from upstream sequences of the corresponding genes of R.capsulatus. This is further suggested by the fact that an fnrL mutation in R.sphaeroides will not grow photosynthetically while in R.capsulatus there is no effect on photosynthetic growth (26). It has been recently shown in our laboratory that FnrL is required for the induction of bchE expression in response to lowering of the oxygen tension (J.I.Oh, J.Eraso and S.Kaplan, unpublished). In addition, the IHF binding motif is also present in the upstream sequence of pucBAC in both species, R.sphaeroides and R.capsulatus (26–28). There are three IHF binding regions (–215 to –200, –160 to –120 and –95 to 80 relative to the transcriptional start site) also found in the upstream sequence of the puf operon of R.capsulatus as suggested by in vitro foot-print analysis and gel retardation assay (27); however, there is no significant sequence similarity among these three regions. On the other hand, the IHF motif is absent in the corresponding sequence of R.sphaeroides. All these presumptive regulatory sites discussed above and presented in Table 2 are located at approximately the same location in both strains of R.sphaeroides.

Although different rates of sequence divergence could explain the regulatory differences that these two species possess, it could not alone account for the difference in gene arrangements around pucBAC and cycA. Rhodobacter sphaeroides and R.capsulatus were also found to be different in many characteristics: for example, presence of two chromosomes (29,30) and extensive gene duplications between the two chromosomes (31–35) in R.sphaeroides which is not the case in R.capsulatus. Detailed genome analysis of R.sphaeroides 2.4.1 have been undertaken in our laboratory, and ultimately the DNA sequence comparison with the R.capsulatus genome will further address the issues of their genome structure and evolution.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr Agnes Puskas for DNA sequencing in the DNA Core facility, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, University of Texas Medical school at Houston. We would also like to thank Dr Soufian Ouchane and Dr Mark Gomelsky for their suggestions on this manuscript. Also, we would like to thank Dr Chris Mechanzie for restoring our WWW server. This work was supported by grant #GM 55481 to S.K.

DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF195122

REFERENCES

- 1.Woese C.R., Stackebrandt,E., Weisburg,W.G., Paster,B.J., Madigan,M.T., Fowler,V.J., Hahn,C.M., Blanz,P., Gupta,R., Nealson,K.H. and Fox,G.E. (1984) Syst. Appl. Microbiol., 5, 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeilstra-Ryalls J., Gomelsky,M., Eraso,J.M., Yeliseev,A., O’gara,J. and Kaplan,S. (1998) J. Bacteriol., 180, 2801–2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer C. and Bird,T.H. (1996) Cell, 85, 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gregor J. and Klug,G. (1999) FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 179, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zsebo K.M. and Hearst,J.E. (1984) Cell, 37, 937–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coomber S.A., Chaudhri,M., Connor,A., Britton,G. and Hunter,C.N. (1990) Mol. Microbiol., 4, 977–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberti M., Burke,D.H. and Hearst,J.E. (1995) Structure and Sequence of the Photosynthesis Gene Cluster. Anoxygenic Bacteria. Kluwer Academic, The Netherlands, pp. 1083–1106.

- 8.Donohue T.J., McEwan,A.G. and Kaplan,S. (1986) J. Bacteriol., 168, 962–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiley P. and Kaplan,S. (1987) J. Bacteriol., 169, 3268–3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong L., Lee,J.K. and Kaplan,S. (1994) J. Bacteriol., 176, 2946–2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomelsky M. and Kaplan,S. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 4609–4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomelsky M. and Kaplan,S. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 1634–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeliseev A.A. and Kaplan,S. (1995) J. Biol. Chem., 270, 21167–21175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGlynn P. and Hunter,C.N. (1993) Mol. Gen. Genet., 236, 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang H.P., Cogdell,R.J., Takaichi,S. and Hunter,C.N. (1995) J. Bacteriol., 177, 2064–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naylor G.W., Gibson,L.C.D., Chaudri,M., Addlesee,H.A., Lang,H.P., McGlynn,P. and Hunter,C.N. (1999) Molecular Biology and Biotechnology (Accession no. AJ010302). University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, in press.

- 17.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 18.Choudhary M., Mackenzie,C., Nreng,K., Sodergren,E., Weinstock,G.W. and Kaplan,S. (1997) Microbiology, 143, 3085–3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mouncey N.J., Choudhary,M. and Kaplan,S. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 7617–7624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altschul S.F., Gish,W., Miller,W., Myers,E.W. and Lipman,D.J. (1990) J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choudhary M., Mackenzie,C., Mouncey,N.J. and Kaplan,S. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 61–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daldal F., Cheng,S., Applebaum,J., Davidson,E. and Prince,R. (1986) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 2012–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.. Tichy H.-V., Albien,K.-U., Gad’on,N. and Drews,G. (1991) EMBO J., 10, 2949–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youvan D.C. and Ismail,S. (1985) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 58–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomelsky M. and Kaplan,S. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeilstra-Ryalls J.H., Gabbert,K., Mouncey,N.J., Kaplan,S. and Kranz,R.G. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 7264–7273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jager K.M. and Klug,G. (1998) Mol. Gen. Genet., 258, 297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J.K., Wang,S., Eraso,J., Gardener,J. and Kaplan,S. (1993) J. Biol. Chem., 268, 24491–24497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suwanto A. and Kaplan,S. (1989) J. Bacteriol., 171, 5850–5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suwanto A. and Kaplan,S. (1992) J. Bacteriol., 174, 1135–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dryden S. and Kaplan,S. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 7267–7277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hallenbeck P.L., Lerchen,R., Hessler,P. and Kaplan,S. (1990) J. Bacteriol., 172, 1736–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hallenbeck P.L., Lerchen,R., Hessler,P. and Kaplan,S. (1990) J. Bacteriol., 172, 1749–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neidle E. and Kaplan,S. (1992) J. Bacteriol., 174, 6444–6454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neidle E. and Kaplan,S. (1993) J. Bacteriol., 175, 2292–2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]