Abstract

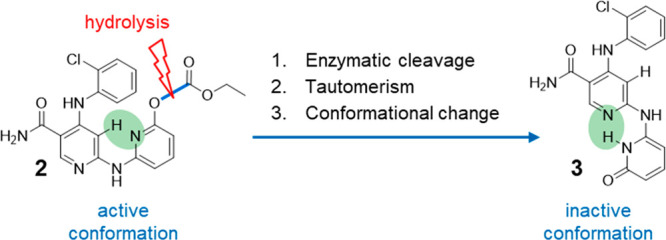

We present a novel concept for the design of supersoft topical drugs. Enzymatic cleavage of the carbonate ester of the potent pan Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor 2 releases hydroxypyridine 3. Due to hydroxypyridine-pyridone tautomerism, 3 undergoes a rapid conformational change preventing the compound to assume the bioactive conformation required for binding to JAK kinases. We demonstrate that the hydrolysis in human blood and the subsequent shape change lead to the deactivation of 2.

Keywords: JAK kinases, soft drug, topical, inhibitor

Soft drugs display their therapeutic activity at the disease-relevant sites of action, however, are rapidly inactivated when leaving these tissues. Usually, they are topically administered directly to the desired tissues (e.g., skin, lung, eye, intestines, nasal mucosa). When reaching the systemic circulation, they are rapidly transformed into inactive metabolites, limiting systemic exposure as well as systemic pharmacology and, therefore, improve the therapeutic index.1

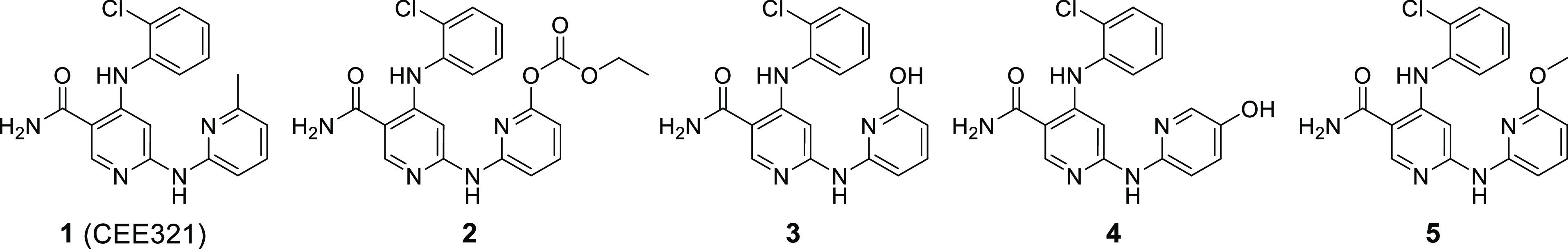

Recently, we disclosed the topical soft JAK inhibitor CEE321 (1, Table 1), which underwent phase 1 trials for the treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD).2 The JAK kinases JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2 play key roles in cytokine signaling. Therefore, JAK inhibition is a promising therapeutic approach for auto immune diseases including AD and several oral drug candidates are under clinical investigation (Table 1).3

Table 1. Structures and Selected Data of Topical JAK Inhibitors in Clinical Trials in Atopic Dermatitis.

| tofacitiniba | delgocitinibb | ruxolitinibb | CEE321c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cellular potencyd INFa (JAK1/TYK2) | 68 | 42 | 65 | 85 |

| whole blood potencyd IL2 (JAK1/3) | 30 | 30 | 329 | 2349 |

| Clinte | <25 | <25 | 40 | 166 |

Phase 2.

Approved.

Phase 1.

IC50 [nM], assay protocols in the Supporting Information.

Intrinsic clearance in human liver microsomes [μL/min mg].

However, systemic JAK inhibition results in side effects leading to boxed warnings in the prescribing information of oral JAK inhibitors recently approved for rheumatoid arthritis.4−6 To reduce systemic exposure topical administration of JAK inhibitors has been considered and several repurposed oral drugs have been approved or investigated in clinical trials (Table 1).7−9 These compounds exhibit low clearance and good potency in blood.2 As a consequence, even topical application of these compounds to larger body surface areas - in particular to patients with reduced skin barrier function, such as pediatric AD patients - could lead to relevant systemic exposure.10 Thus, systemic target-related side effects due to JAK inhibition cannot be excluded.11 In contrast to these repurposed oral drugs, we consider CEE321 to be a soft JAK inhibitor because it exhibits good potency in cellular assays and in human skin but high hepatic clearance and limited potency in blood (Table 1).2

To accelerate the inactivation of the parent drug in circulation even further and to improve the therapeutic index, we explored extrahepatic metabolism pathways for the inactivation of a topically active drug. Here we present a novel concept for the design of topical soft drugs based on the very rapid hydrolysis of the potent pyridin-2-yl carbonate 2 by blood esterases12,13 to release 3, which, due to hydroxypyridine-pyridone tautomerism, undergoes a substantial conformational change preventing binding to the target and thus, inactivating the parent drug (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Novel concept for the design of topical soft drugs. Carbonate 2 can adopt the bioactive compact conformation required to bind to and to inhibit JAK kinases in the skin after topical administration. After crossing the skin rapid hydrolysis of 2 by blood esterases releases 3. Due to hydroxypyridine-pyridone tautomerism and a subsequent structural rearrangement, 3 adopts a stretched conformation, which cannot bind to and inhibit JAK kinases. As a consequence, the active drug 2 is disarmed instantaneously.

The analysis of the bioactive conformation of CEE321 and the conformation of its HCl-salt in the solid state provided the inspiration for the design of the new concept. Modeling of the binding mode of CEE321 in JAK2 indicated a compact conformation (Figure 2) with a pseudo H-bond established between the N-atom of the terminal pyridine and a sp2-H-atom of the central pyridine.14 Both pyridine rings and the amide group are in the same plane. Three important H-bonds can be established with the backbone of the kinase (Glu930, Tyr931, and Leu932). Interestingly, the crystalline HCl-salt of CEE321 adopts a stretched conformation (Figure 2). An internal H-bond is established between the protonated N-atom of the central pyridine and the N-atom of the terminal pyridine. Like in the bioactive conformation the pyridine rings and the amide group are in the same plane. However, in contrast to the bioactive compact conformation, the stretched conformation would not allow establishing the critical H-bonds to Tyr931 and Leu932 required for binding to JAK kinases. In addition, the stretched conformation cannot be accommodated in the binding site for steric reasons. Under physiological conditions CEE321 (pKa = 6.2) is not substantially protonated, adopts the compact conformation and therefore, inhibits all four JAK kinases (Table 2). However, a compound related to CEE321 assuming the stretched conformation of protonated CEE321 is not expected to be a potent JAK inhibitor.

Figure 2.

Analysis of conformations of neutral and protonated CEE321 and X-ray structures of the hydrochloride of CEE321 and compound 3 (CCDC Deposition Numbers: 2262925 and 2262926, respectively).

Table 2. Structures and Key Data on Compounds 1–5.

| compound | enzyme JAK1a | enzyme JAK2a | enzyme JAK2a | enzyme TYK2a | cell IL15a JAK1/3 | cell INFαa JAK1/TYK2 | blood IL2a JAK1/3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (CEE321) | 50 ± 12 | 48 ± 8 | 59 ± 6 | 60 ± 11 | 54 ± 10 | 85 ± 16 | 2349 ± 306 |

| 2 | 131 ± 50 | 52 ± 23 | 76 ± 36 | 59 ± 25 | 116 ± 20 | 71 ± 9 | >30000 |

| 3 | 3272 ± 1038 | 3154 ± 786 | 4563 ± 1418 | 2094 ± 680 | >10000 | >10000 | >30000 |

| 4 | 14 ± 12 | 20 ± 8 | 20 ± 6 | 17 ± 11 | 218 ± 120 | 290 ± 105 | 525 ± 96 |

| 5 | 103 ± 11 | 76 ± 6 | 89 ± 8 | 77 ± 11 | 169 ± 36 | 271 ± 34 | 2169 ± 142 |

IC50 values [nM]; assay protocols in the Supporting Information.

The hydroxypyridine-pyridone tautomerism of an analog of CEE321, such as compound 3 with a hydroxyl group instead of the methyl group adjacent to the N atom of the terminal pyridine would lead to similar conformational effects as observed for neutral and protonated CEE321 (Figure 2). The hydroxypyridine tautomer could adopt a compact conformation similar to the bioactive conformation of CEE321. The pyridone tautomer should prefer a stretched conformation. The X-ray structure of 3 showed that in the solid state the pyridone tautomer is indeed preferred and that it is adopting the stretched conformation with a stabilizing H-bond between the pyridine rings (Figure 2). ReSCoSS (Relevant Solution Conformer Sampling and Selection Workflow) calculations in aqueous solution indicated that the stretched conformation of the pyridone is at least 7 kcal lower in energy compared to any hydroxypyridine conformation.15 The 1H–15N HMBC NMR spectrum of 3 in CD3OH showed a signal for the terminal pyridine N atom at 168.4 ppm, which is indicative for the pyridone tautomer (see the Supporting Information). The Mnova NMR software predicted 157 ppm for the pyridone but 285 ppm for the hydroxypyridine. The 15N-shift for unsubstituted pyridone in deuteroethanol was determined to be 172 ppm a value very similar to the 168.4 ppm found for 3.16 Overall, there is compelling evidence that 3 prefers the pyridone tautomeric form and assumes the stretched conformation. Indeed, 3 was found to be a poor JAK inhibitor (IC50 values between 2094 and 4563 nM in biochemical assays; inactive in cellular assays; Table 2), as expected for a compound that does not adopt the required bioactive conformation. Compound 3 was also found to be a poor inhibitor of non-JAK kinases, such as GSK3b, KDR, AuroraA, IRAK4, FLT3, STK4, LCK, and p70S6K (IC50 values > 2500 nM).

Interestingly, compound 4 with a hydroxyl group in the 3-position of the terminal pyridine ring was highly potent in our biochemical JAK assays showing IC50 values between 14 and 20 nM (Table 1). Compound 4 cannot form a pyridone and therefore prefers the bioactive compact conformation. In order to prevent the formation of the pyridone and to “freeze” the bioactive conformation of the hydroxypyridine tautomer of 4 we methylated the O atom of the hydroxypyridine and prepared 5 with a methoxy group adjacent to the N atom of the terminal pyridine ring. As expected, 5 was found to be a potent JAK inhibitor with IC50 values between 77 and 102 nM (Table 2).

We reasoned that the enzymatic conversion of a potent analog of compound 5 releasing the corresponding hydroxypyridine 3 would rapidly lead to the formation of the preferred pyridone tautomer. The subsequent switch from the closed to the open conformation would inactivate the parent drug.

Blood esterases exhibiting a broad substrate specificity have been frequently utilized to release active drugs following absorption of more permeable ester prodrugs.12,13 We set out to explore this approach for the inactivation of a compound 5-like JAK inhibitor and designed the “hydroxypyridine precursor” 2 with a carbonate ester group adjacent to the N atom of the terminal pyridine (Table 2). Compound 2 can adopt the bioactive conformation and could be a substrate for blood esterases. We were pleased to find 2 to be as potent as CEE321 in both biochemical assays (IC50 values from 52–131 nM) and cellular assays (IC50 values of 71 and 116 nM). In addition, we found 2 to be a good substrate for blood esterases indicated by a short half-life in human blood of ∼4 min (Figure 3; details in the Supporting Information). The compound is rapidly converted into poorly active 3.

Figure 3.

Hydrolysis of 2 and formation of 3 in human blood (1 μM, 37 °C).

All compounds were evaluated in our human whole blood assay (Table 2). Compared to their promising cellular activity (54–271 nM), CEE321 and its analogs 5 and 4 showed reduced but still appreciable activity (525–2349 nM). However, 2 was completely inactive despite of its substantial potency in cell assays. Taking into account that the protocol of the whole blood assay involves 30 min preincubation in blood prior to stimulation with IL-2 and considering its rapid conversion in human blood, we believe that under the assay conditions 2 has been entirely hydrolyzed to inactive 3.

The carbonate ester 2 was stable in bulk and sufficiently stable to be tested in biochemical and cellular assays. However, 2 exhibited insufficient stability in aqueous mixtures of excipients used in topical formulations preventing us from testing the compound in skin models. So far, our attempts to improve chemical stability were either unsuccessful or led to analogs, which were poor esterase substrates.

Compounds 2–5 were prepared from known building block 62 (Scheme 1). Introduction of aminopyridines 7 and 8 led to JAK inhibitors 4 and 5, respectively. O-Demethylation of compound 4 with pyridine hydrochloride furnished compound 3, which was transformed into 2 by treatment with ethyl carbonochloridate.

Scheme 1. Syntheses of Compounds 2–5.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Pd2(dba)3, BINAP, Cs2CO3, TEA, dioxane, 100 °C, 12 h; (b) pyridine × HCl, 180 °C, 5 h; (c) TEA, DMF, 15 °C, 12 h; (d) tBuXPhos-Pd-G3, TEA, THF/H2O, 50 °C, 0.75 h.

In summary, we have presented a novel concept for the design of supersoft topical drugs. Enzymatic cleavage of the carbonate ester of the potent pan JAK inhibitor 2 releases hydroxypyridine 3. Due to hydroxypyridine-pyridone tautomerism, 3 undergoes a rapid conformational change preventing the compound to assume the bioactive conformation required for binding to JAK kinases. We demonstrated that ester-mediated hydrolysis in human blood and subsequent shape change led to deactivation of 2. Unfortunately, 2 exhibits insufficient stability in formulation-like aqueous mixtures. Thus, additional work is required to improve chemical stability and come up with analogs of 2, which would allow testing the concept in human skin models.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the expert assistance of Mailin Ashoff, Andrea Decker, Odile Decoret, Alice Hauchard, and Anne-Marie Jutzi-Spony.

Glossary

Abbreviations Used

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- HMBC

heteronuclear multiple bond correlation

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- JAK

Janus kinase

- ReSCoSS

relevant solution conformer sampling and selection workflow

- TYK2

tyrosine kinase 2

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00169.

Accession Codes

CCDC deposition numbers: CEE321, 2262925; compound 3, 2262926. Authors will release the atomic coordinates and experimental data upon article publication.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Buchwald P. Soft drugs: design principles, success stories, and future perspectives. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2020, 16, 645–650. 10.1080/17425255.2020.1777280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Aprile S.; Serafini M.; Pirali T. Soft drugs for dermatological applications: recent trends. Drug Discovery Today 2019, 24, 2234–2246. 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma G.; Duthaler R. O.; Waelchli R.; Hauchard A.; Bruno S.; Strittmatter-Keller U.; Orjuela Leon A.; Viebrock S.; Aichholz R.; Beltz K.; Grove K.; Hoque S.; Rudewicz P. J.; Zerwes H.-G. Discovery and characterization of the topical soft JAK inhibitor CEE321 for atopic dermatitis. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 2161–2168. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X.; Li J.; Fu M.; Zhao X.; Wang W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 402. 10.1038/s41392-021-00791-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M. A.; Torres T. JAK/STAT inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2020, 31, 33–40. 10.1080/09546634.2019.1577549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsky W.; King B. A. The JAK-STAT Pathway and the JAK Inhibitors. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 736–744. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harigai M. Growing evidence of the safety of JAK inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. (United Kingdom) 2019, 58, i34–i42. 10.1093/rheumatology/key287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonnette R.; Papp K. A.; Poulin Y.; Gooderham M.; Raman M.; Mallbris L.; Wang C.; Purohit V.; Mamolo C.; Papacharalambous J.; Ports W. C. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa randomized trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 902–911. 10.1111/bjd.14871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H.; Nemoto O.; Igarashi A.; Saeki H.; Murata R.; Kaino H.; Nagata T. Long-term safety and efficacy of delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 114–120. 10.1111/1346-8138.15173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. S.; Howell M. D.; Sun K.; Papp K.; Nasir A.; Kuligowski M. E. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with ruxolitinib cream (JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor) or triamcinolone cream. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 572–582. 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D. Y. M.; Paller A. S.; Zaenglein A. L.; Tom W. L.; Ong P. Y.; Venturanza M. E.; Kuligowski M. E.; Li Q.; Gong X.; Lee M. S. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of ruxolitinib cream in children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023, 130, 500–507. 10.1016/j.anai.2022.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The recently approved topical ruxolitinib (Opzelura) has similar warnings in the label as other JAK inhibitors administered by the oral route (Prescribing Information | OPZELURA (ruxolitinib)).

- Beaumont K.; Webster R.; Gardner I.; Dack K. Design of ester prodrugs to enhance oral absorption of poorly permeable compounds: challenges to the discovery scientist. Curr. Drug Metabol. 2003, 4, 461–485. 10.2174/1389200033489253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautio J.; Meanwell N. A.; Di L.; Hageman M. J. The expanding role of prodrugs in contemporary drug design and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2018, 17, 559–587. 10.1038/nrd.2018.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The modeling was based on the structure of ruxolitinib bound to JAK2 (6VGL).Davis R. R.; Li B.; Yun S. Y.; Chan A.; Nareddy P.; Gunawan S.; Ayaz M.; Lawrence H. R.; Reuther G. W.; Lawrence N. J.; Schönbrunn E. Structural insights into JAK2 inhibition by ruxolitinib, fedratinib, and derivatives thereof. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 2228–2241. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udvarhelyi A.; Rodde S.; Wilcken R. ReSCoSS: a flexible quantum chemistry workflow identifying relevant solution conformers of drug-like molecules. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. Transduct. 2021, 35, 399–415. 10.1007/s10822-020-00337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Someswara Rao N.; Babu Rao G.; Murthy B. N.; Maria Das M.; Prabhakar T.; Lalitha M. Natural abundance nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic resonance spectral studies on selected donors. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2002, 58, 2737–2757. 10.1016/S1386-1425(02)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.