Abstract

The DNA methyltransferase 2 (DNMT2) is an RNA modifying enzyme associated with pathophysiological processes, such as mental and metabolic disorders or cancer. Although the development of methyltransferase inhibitors remains challenging, DNMT2 is not only a promising target for drug discovery, but also for the development of activity-based probes. Here, we present covalent SAH-based DNMT2 inhibitors decorated with a new type of aryl warhead. Based on a noncovalent DNMT2 inhibitor with N-benzyl substituent, the Topliss scheme was followed for optimization. The results showed that electron-deficient benzyl moieties highly increased affinity. By decorating the structures with strong electron-withdrawing moieties and leaving groups, we adjusted the electrophilicity to create covalent DNMT2 inhibitors. A 4-bromo-3-nitrophenylsulfonamide-decorated SAH derivative (80) turned out to be the most potent (IC50 = 1.2 ± 0.1 μM) and selective inhibitor. Protein mass spectrometry confirmed the covalent reaction with the catalytically active cysteine-79.

Keywords: DNMT2, covalent SAH-based inhibitors, aryl warhead, Topliss scheme, microscale thermophoresis, protein mass spectrometry

RNA and its modifications play a significant role in epigenetic inheritance.1,2 Studies revealed that some RNA modifications are linked to mental3 and metabolic disorders.4 Inheritance of metabolic disorders has been found to be caused by increased levels of m2G and m5C modifications.5 The human DNA methyltransferase 2 (hDNMT2), which among others is responsible for m5C modifications, is involved in this process.6 Due to its similar sequence and structure, hDNMT2 is part of the DNA methyltransferase family, but its main substrate is tRNA at position C38.7,8 hDNMT2 plays a role in different physiological processes but is also linked to cancer.8

To transfer a methyl group to tRNA, hDNMT2 requires S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) as a cofactor, releasing m5C38-tRNAAsp and S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (SAH) as a byproduct.7 Besides the natural inhibitors SAH and sinefungin (SFG),9 the chemotherapeutic agents 5-azacytidine, decitabine, and zebularine are known to inactivate DNMTs.10

Methyltransferases are hard-to-drug targets, especially due to the high cellular concentration of SAM11 that competes with a potential inhibitor. Furthermore, most of the over 200 different methyltransferases (MTases)12 in humans are SAM-dependent, which increases the challenge to find selective SAH-based inhibitors. Because covalent inhibitors are capable of competing with high natural ligand concentrations,13 these issues can be overcome with a warhead-decorated SAH derivative. Moreover, high selectivity can be achieved by targeting the catalytically active cysteines found in the hDNMT14 or NOL1/NOP2/sun domain (NSUN)15 families since various other MTases follow different mechanisms.16 Such covalent modifiers can also be a suitable basis for the development of fluorescently labeled activity-based probes (ABPs),17 which can be used to improve the understanding of RNA methyltransferases and their RNA modifications.

Here, we present covalent SAH-based hDNMT2 inhibitors with 4-halo-3-nitrophenylsulfonamide warheads. This warhead class represents a well-fitting substructure for the cytidine binding site of the enzyme, as it not only mimics the cytidine residue of tRNA but also provides proper orientation and length to reach the catalytically active cysteine-79. Recently, we published hDNMT2 inhibitors based on the SAH scaffold.9 We replaced the sulfur atom with various N-alkylated substructures, and the N-but-3-yn-2-yl derivative 1 turned out to be the most potent inhibitor of hDNMT2 in a tritium-incorporation assay (3H-assay) (IC50 = 12.9 ± 1.9 μM). We also tested the N-benzylated derivative 2, which showed moderate affinity (57% at 100 μM). Because the phenyl moiety allows a huge space for modifications, we considered the scaffold as a basis for optimization.

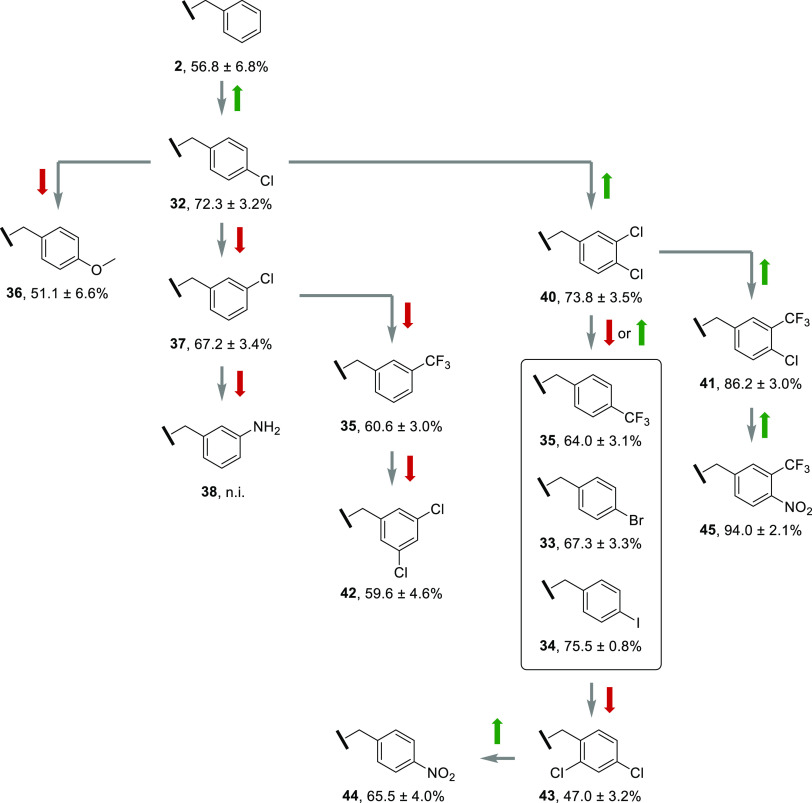

Starting from this structure, we developed N-benzyl containing compounds according to the Topliss scheme (Figure 1). This is an operational scheme in drug design for the derivatization of aromatic compounds considering hydrophobic (π), electronic (σ), and steric (Es) values of different substituents.18 Starting from an unsubstituted phenyl moiety, the 4-chloro analogue is initially proposed as it increases the π value. Subsequently, we followed the scheme suggestions depending on the inhibitory effects. Selected derivatives of nonproposed paths were also tested for comparison.

Figure 1.

Derivatization of the benzylamine derivative 2 according to the Topliss scheme. Based on the 4-chloro-3-trifluoromethyl and the 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethyl derivatives, an additional SAR study was conducted. First, the aminomethyl substructure was exchanged with a sulfonamide unit to increase the electrophilicity. The aryl moiety was decorated with electron-withdrawing groups and leaving groups to allow a potential covalent reaction with the catalytically active cysteine of hDNMT2.

We performed an additional structure–activity relationship study based on the scaffold that exhibited the highest activity. The methylenamine substructure of the N-benzyl moiety was replaced with a sulfonamide to test the influence of an additional −I and −M effect. To allow a covalent reaction with the catalytically active cysteine in the cytidine site, electron-deficient aryls with halogen leaving groups were designed to increase electrophilicity. To confirm the covalent reaction between ligand and hDNMT2, protein mass spectrometric experiments were conducted.

Chemistry

The benzyl derivatives were synthesized by reductive amination using protected adenosyl-2,4-diaminobutyric acid (adenosyl-Dab)93 and substituted benzaldehydes 4–17 (Scheme 1). For this, sodium triacetoxyborohydride and acetic acid were used as reagents in 1,2-dichloroethane. The building block 3 was prepared according to a previously described procedure.9 In the final step, the protecting groups were removed by treatment with 50% (v/v) TFA in dichloromethane at 5 °C, followed by treatment with 14% (v/v) TFA in water at 5 °C. To further increase the electrophilicity of the aromatic ring, the methylenamine substructure of the benzyl moiety was exchanged by a sulfonamide group. With its −I and −M effects, this compound class shows interesting properties as electron-withdrawing substituents seemed to increase the affinity for hDNMT2. Electron-withdrawing groups which can potentially act as leaving groups, such as halides, were chosen as substituents to enable a possible covalent reaction with the catalytically active cysteine of hDNMT2. To obtain the sulfonamide-based inhibitors, building block 3 was brought to reaction with substituted phenylsulfonyl chlorides 46–58 either in the presence of triethylamine in DCM under reflux or using a two-phase system consisting of DCM and saturated NaHCO3 solution at room temperature (Scheme 2). In the final step, the resulting precursors 59–71 were deprotected using 50% (v/v) TFA in dichloromethane at 5 °C, followed by treatment with 14% (v/v) TFA in water at 5 °C to give the inhibitors 72–84. To investigate the effect of intracyclic nitrogens as replacements for the nitro groups, pyridine and pyrazine derivatives decorated with chlorine were synthesized (Scheme 3). The pyridine derivative 90 was prepared by combining the building block 3 and 6-chloropyridine-3-sulfonyl chloride 85 with triethylamine in DCM under reflux to yield the protected precursor 88. For the synthesis of the pyrazine derivative 91, 2,5-dichloropyrazine 86 was substituted with benzyl mercaptan in the presence of sodium hydride in THF to give 87. In the next step, 87 was treated with sulfuryl chloride19 and was reacted with the building block 3 using a two-phase system consisting of DCM and saturated NaHCO3 solution at room temperature to yield the protected pyrazine derivative 89. The precursors 88 and 89 were finally deprotected using 50% (v/v) TFA in dichloromethane at 5 °C, followed by treatment with 14% (v/v) TFA in water at 5 °C to yield the inhibitors 90 and 91. A 2-chloropyrimidine derivative was also to be synthesized, but due to its high reactivity already with weak nucleophiles such as methanol and water, which led to substitution of chlorine, it was not further pursued.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Benzylamine Derivatives 32–45.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaBH(OAc)3, HOAc, 1,2-DCE, 0 °C to rt, overnight, 37–96%; (b) (1) TFA/DCM (1:1 v/v), 5 °C; (2) TFA/H2O (1:6 v/v), 5 °C, 99%.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Sulfonamide Derivatives 72–84.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NEt3, DCM, Δ, 2 h, 52–73%; (b) NaHCO3, H2O, DCM, rt, overnight, 43–82%; (c) (1) TFA/DCM (1:1 v/v), 5 °C; (2) TFA/H2O (1:6 v/v), 5 °C, 99%.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of the Heterocycles 90 and 91.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NEt3, DCM, Δ, 2 h, 62%; (b) benzyl mercaptan, NaH, THF, 1 h at 0 °C, 16 h at rt, 91%, (c) (1) sulfuryl chloride, –5 °C, 2 h; (2) 3, NaHCO3, H2O, DCM, rt, overnight, 34%; (d) (1) TFA/DCM (1:1 v/v), 5 °C; (2) TFA/H2O (1:6 v/v), 5 °C, 99%.

Biological Evaluation: hDNMT2 Binding and Inhibition

To determine the binding affinity of the compounds toward hDNMT2, a screening was performed with full-length hDNMT2 (if not described otherwise, full-length protein was used) based on a microscale thermophoresis (MST) displacement method using the fluorescent ligand FTAD.20 Potent binders were defined as compounds that were able to displace FTAD appoximately to the same extent as SFG (MST shift ≥13‰; cut-off ≥10‰). For all potent binders an apparent KD value (KDapp) was determined using MST. All other compounds were not further evaluated. Ligands with the highest affinity toward hDNMT2 (41, 45, 78–80, and 91; 32 for comparison), were subjected to isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), which served as an orthogonal method to quantify the binding affinity of those ligands. The results from ITC measurements confirmed the data of the MST measurements, as the results of both methods showed a high consistency. Finally, to investigate their actual inhibitory effect, the most potent binders and some selected weak binders were evaluated using a 3H-assay. The assay was performed with tRNAAsp as substrate and tritium-labeled SAM (3H-SAM) as cosubstrate at a compound concentration of 100 μM. For the most potent inhibitors IC50 values were determined. All results are summarized in Table 1. Within the benzyl series, 7 out of 14 compounds (32, 34, 35, 40, 41, 44, and 45) could be classified as promising binders, as they caused an MST shift ≥10‰. Starting with the 4-chloro substituent 32 in the Topliss scheme, an increase in inhibition from 57% to 72% was achieved. According to the scheme, the proposed modification in this case is the 3,4-dichloro substitution (40). With an inhibition of 74%, it did not show a significant increase in potency, resulting in the proposed modifications 4-CF3, 4-Br, and 4-I. While the 4-bromo (33) and 4-trifluoro (35) derivatives showed reduced inhibition (67% and 51%, respectively), the 4-iodo modification (34) was equipotent (75%). Based on alternative modifications in this branch, we tested the 2,4-dichloro derivative 43, which further reduced inhibition to 47%. Because the proposed modifications of this branch did not significantly improve inhibition, we followed the branch proposed if the 3,4-dichloro substitution (40) would be classified as more potent (73.8 ± 3.5% vs 72.3 ± 3.1%) than the 4-chloro modification (32) after all. As a result, the proposed modification 4-chloro-3-trifluoromethyl 41 was tested and exhibited a significant increase in inhibition of up to 86%. Based on this result, the scheme proposed the 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethyl derivative 45 as a final modification. Notably, an even higher inhibition of 94% (IC50 = 2.5 ± 0.2 μM) was achieved. To identify potential inhibitors that were likely omitted due to incorrect prediction of the scheme we selected different structures of the remaining branches: 4-OMe (36), 3-Cl (37), 3-NH2 (38), 3-CF3 (39), 3,5-diCl (42), and 4-NO2 (44). The tests revealed that the derivatives 36, 37, 39, and 42 showed moderate inhibition of 59–67%, whereas the 3-amino structure 38 was inactive. Interestingly, the nitro derivative 44 showed a significant increase in inhibition compared to its direct branch precursor 43 (66% vs 47%). However, its inhibition was still lower than that of compounds 33–35 of the same branch. Evaluation of the inhibition of hDNMT2 in correlation with the substituent effects revealed that the results were in high accordance with the Topliss scheme suggestions (Figure 2). It could be observed that the more electron-withdrawing groups were introduced, the stronger was the inhibition of hDNMT2, which was demonstrated by the following branch: 4-Cl (32) → 3,4-diCl (40) → 4-Cl-3-CF3 (41) → 4-NO2-3-CF3 (45) with increasing inhibition of 72% → 74% → 86% → 94%, respectively. While substituents in position 2 significantly reduced inhibition, probably due to steric hindrance within the binding pocket, introduction of several groups at position 3 was tolerated. However, the potency compared to the phenyl derivative 2 was only slightly increased from 56% to 67% by introducing the 3-Cl substituent (37). Position 4 also allowed several substituents, e.g., 4-Cl (32), 4-Br (33), 4-I (34), 4-CF3 (35), 4-OMe (36), and 4-NO2 (44), all of which increased the potency compared to the unsubstituted inhibitor 2. A significant increase in inhibition was achieved with the 4-Cl (72%) and the 4-I (75%) substituents. Interestingly, they differ in electronegativity and volume, yet they showed equipotent inhibition of hDNMT2. So far, a disubstituted, electron-deficient benzyl group appeared to be most effective at enhancing inhibition.

Table 1. Binding of Compounds to hDNMT2 as Determined by MST and Inhibition of hDNMT2 as Determined in the 3H-Assaysa.

n.d. = not determined, n.i. = no inhibition.

Figure 2.

Synthesized compounds and corresponding results with depiction of positions in the Topliss scheme. Arrows indicate either increase (green) or decrease (red) in inhibition.

To further increase electrophilicity of the aromatic ring, we replaced the methylenamine substructure of the N-benzyl moiety with a sulfonamide that introduces additional −I and −M effects. Based on this modification, a subsequent structure–activity relationship (SAR) study was conducted using different aryl sulfonyl moieties with strong electron-withdrawing groups such as NO2 and CF3 as well as intracyclic nitrogen atoms. To enable a possible covalent reaction with the catalytically active cysteine, the aromatic rings were decorated with halogen leaving groups. First, we started with the 4-chloro-3-trifluoromethyl analogue 72 for comparison with one of the most active compounds (41). With an inhibition of 54%, it showed a significantly lower inhibition than 41 with 86%, which indicates a negative effect of the sulfonamide group. The same holds true for 73 (4-Cl, no inhibition), 74 (3,4-diCl, 28% inhibition), 75 (2,4-diCl, no inhibition), 76 (unsubstituted, no inhibition), and 77 (4-NO2, no inhibition), which caused significantly lower inhibition compared to their corresponding benzyl derivatives. Interestingly, the 4-chloro-3-nitro derivative 78 had the highest inhibitory activity of 98% (IC50 = 2.3 ± 0.5 μM). Given 78 as the new lead structure, we analyzed changes in the substitution pattern. For the 4-F-3-NO2 modification (79), a slightly lower inhibition of 93% (IC50 = 8.5 ± 1.3 μM) was observed, while the 4-Br-3-NO2 derivative 80 was found to be equipotent with an inhibition of 99% (IC50 = 1.2 ± 0.1 μM). Other structural changes such as 3-NO2 (81), 2-Cl-5-NO2 (82), and 2-F-5-NO2 (83) did not lead to inhibition of hDNMT2. The 3-Cl-4-NO2 derivative 84 showed only moderate inhibition of 67%. Replacing the 3-nitro group of 78 with an intracyclic nitrogen (90) atom resulted in a strong reduction of inhibition to 33%. However, a second intracyclic nitrogen located in the opposite position, as found in pyrazine moieties, increased the inhibition to 100% (91, IC50 = 1.1 ± 0.2 μM). Comparing the benzyl derivatives with the sulfonamide-based compounds, an obvious trend is observable. The sulfonamide derivatives showed significantly lower inhibition compared to their benzyl analogues, e.g., 32 vs 73 (4-Cl), 40 vs 74 (3,4-diCl), and 41 vs 72 (4-Cl-3-CF3). Yet the 4-Cl/Br-3-NO2 substituted sulfonamide-based derivatives 78 and 80 as well as the 4-chloropyrazine derivative 91 showed the highest inhibition (IC50 < 2.5 μM). The results also highlight the quality of our FTAD-based MST screening method20 because the screening results showed high consistency with the measured inhibition in the 3H-assay.

Warhead Stability in the Presence of DTT

We found that the inhibition of hDNMT2 by compound 79 was highly dependent on the presence of the reducing agent used in the assays. While inhibition of 93% (IC50 = 8.5 ± 1.3 μM) was measured in the presence of TCEP, no inhibition could be observed in the presence of DTT. These findings strongly suggest a covalent reaction of the thiol-based agent with the electrophilic inhibitor. For this reason, we conducted stability tests with DTT and the inhibitors 78–80 in TRIS buffer pH = 8.0 at room temperature under assay-like conditions. The inactivation was determined by LC-MS after 2 min followed by 15 min intervals (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Stability test of inhibitors 78–80 in the presence of DTT under assay-like conditions. Percent inactivation was determined initially after 2 min and then at 15 min intervals.

LC-MS measurements confirmed the formation of a DTT substitution product in all three cases. Figure 3 shows that 79 already completely reacted with DTT after 2 min. 78 reacts with a rate comparable to 80, but much slower than 79. In the first 15 min, both react very quickly until a conversion of ca. 60% was reached. A full conversion was observed after 90 min, respectively.

Protein Mass Spectrometry

To investigate the binding of the ligands 45, 78–80, and 91 to hDNMT2, we used intact-protein LC-MS under denaturing conditions, which only preserve covalently bound ligands. Additionally, direct infusion nanoelectrospray ionization experiments were performed under nondenaturing conditions, which allow preservation of noncovalent binding. hDNMT2 harbors a flexible loop (residues 191–237) that decreases protein stability and prevents crystallization. However, a construct without this loop was cocrystallized with SAH (PDB 1G55). Based on this construct, a deletion mutant without residues 191–237 (hDNMT2Δ) was designed, which was better suited for mass spectrometry than hDNMT2.

hDNMT2Δ showed decreased but measurable activity in the 3H-assay, which supports the hypothesis that hDNMT2Δ binds SAH. For all experiments, the known noncovalent ligand SFG was used as a control. All LC-MS spectra exhibited the broad charge state distribution and high charge states typical for denatured proteins. In Figure 4A, the results of these measurements, zoomed in on the region around charge state 32+ (m/z 1293), are shown. For 78–80, the same mass shift of 551 Da, corresponding to addition of the structure highlighted in orange, was observed. This indicates loss of the halogen substituent and the formation of a covalent bond between the protein and ligand. A second addition of ligand 79 was detected, which suggests the existence of two potential binding sites of this ligand and therefore a less specific binding of the desired target cysteine. A comparable result was observed with ligand 91, where two mass shifts of 508 Da, corresponding to the blue-highlighted structure, were detected. Here, a very low amount of remaining free protein signal was observed, which indicates a fast and favorable reaction of this ligand with hDNMT2Δ. For 45 and the known noncovalent ligand SFG, no mass shift and thus no covalent irreversible binding was demonstrated. A table with observed and calculated masses, mass errors, and intensities can be found in the Supporting Information. Additional measurements under near-native conditions were performed with SFG and 45 (Figure 4B). As is typical in native MS, these spectra show a narrow charge state distribution with low charge states. For both ligands, a shift by the corresponding mass was detected (570 Da for 45; 381 Da for SFG). Furthermore, a second binding event of ligand 45 was observed. This demonstrates the noncovalent binding of 45 and SFG to hDNMT2Δ. This second, but weaker binding event observed for 45 and 74 could also explain the increased binding stoichiometry determined in the ITC experiments (1.37 ± 0.01 and 1.34 ± 0.04, respectively). On the other hand, for 91, a decreased binding stoichiometry (0.84 ± 0.01) was measured, leading to the assumption that this compound is too reactive and therefore could cause partial protein aggregation. All other compounds investigated with ITC showed binding stoichiometries in the range from 0.9 to 1.1 toward hDNMT2Δ, which correlates nicely with data obtained from protein MS. We determined the binding sites of the covalent ligands with a tryptic digest followed by bottom-up LC-MS/MS. A high sequence coverage of over 80% was achieved for all samples. For 78–80, binding to Cys79, which is known to be the catalytically active cysteine, was detected. In agreement with the denatured intact mass measurements, which indicated a second binding site for 79, an additional modified peptide containing the cysteine residue corresponding to Cys287 in the wild-type protein was detected. Similarly, binding of 91 was also observed at Cys79 and Cys287. As expected, no modified peptides were detected for 45 and SFG, which is consistent with a noncovalent binding mode. These findings indicated two covalent binding sites for 79 and 91, and the binding to only the desired target Cys79 for 78 and 80. Given that four surface-exposed cysteines can be found in the crystal structure of hDNMT2 (PDB 1G55), the results highlight the nonpromiscuous binding behavior of compounds 78 and 80, which only reacted with the catalytically active Cys79. A detailed overview of the results is shown in the Supporting Information.

Figure 4.

(A) LC-MS of intact, denatured hDNMT2Δ with and without ligands. Corresponding peak for free protein signal is highlighted in gray (32+ charge state). For 45 and SFG, no binding was detected under denaturing conditions. Binding to 78–80 all led to addition of the same 551 Da moiety (mass shift and corresponding structure shown in orange). Binding to 91 led to addition of a 508 Da moiety (structure and mass shift shown in blue). (B) Native MS of hDNMT2Δ in complex with 45 and SFG. Peaks corresponding to free protein signal (charge states 14+ and 15+) are highlighted in gray. Binding to 45 (two binding events) and SFG (one event) are highlighted in blue and orange, respectively.

Selectivity

Selectivity of the most promising inhibitors (45, 78–80, and 91) toward other tRNA modifying m5C MTases (NSUN2 and NSUN6) was measured in a 3H-assay at 100 μM (Figure 5). All selected inhibitors showed higher selectivity compared to SFG,9 with compound 80 being the most selective one as it did not inhibit NSUN2 and NSUN6. Compounds 78 and 91 appeared to be highly selective as they showed only slight inhibition of NSUN2 (12 ± 6.8% and 13 ± 9.2%) and NSUN6 (n.i. and 7 ± 4.9%). Lower selectivity was observed for 45 (12 ± 1.3% for NSUN2; 30 ± 0.1% for NSUN6) and 79 (23 ± 4.9% for NSUN2; 69 ± 4.8% for NSUN6). Given that 79 is highly reactive, a lack of selectivity was expected. Furthermore, detection of beyond active site binding to hDNMT2Δ for 45 and 79 via LC-MS already indicated a promiscuous binding behavior of those compounds. To investigate a concentration range more common in biochemical assays, the selectivity was also determined at 10 μM inhibitor concentration (Supporting Information). All tested inhibitors except 79 have been found to be highly selective yet potent hDNMT2 inhibitors at 10 μM.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of different RNA methyltransferases by most potent DNMT2 inhibitors at 100 μM. Triplicates ± SD are given. (a) Data from previous study.

Docking Studies Confirm Proper Orientation Allowing Covalent Reaction

To investigate the binding mode of compounds 45, 78–80, and 91 and confirm a proper orientation that enables a covalent reaction, docking studies using FlexX21 and MOE (Molecular Operating Environment, 2022.02 Chemical Computing Group ULC, Montreal, Canada, 2023) were performed (Supporting Information). Because the catalytic loop (residues 79–96) is not resolved in the crystal structure of hDNMT2 (PDB 1G55), it was introduced using the “Loop Modeler” functionality within MOE.

Based on the docking-predicted binding modes, the benzyl derivative 45 as well as the aromatic sulfonamides 78–80 and 91 expand from the SAM site toward the cytidine binding site. Figure 6 shows the binding poses of compound 80 as an example. The proximity of the electrophilic carbon atoms to the nucleophilic sulfur atom of the catalytic Cys79 of 3.9–4.2 Å (Table S3) indicated high likeliness of a covalent reaction.

Figure 6.

Noncovalent and covalent docking of compound 80 (cyan) with SAH as reference (salmon). (A) Crystal structure of SAH (PDB 1G55). (B) Noncovalent docking of compound 80. The distance of the electrophilic carbon to Cys79 is indicated with a red dotted line. (C) Covalent docking of compound 80.

Conclusion

In this letter, we presented covalent SAH-based hDNMT2 inhibitors with a new type of aryl warhead. By successfully applying the Topliss scheme to the moderate inhibitor N-benzyl-adenosyl-Dab 2,9 electron-deficient benzyl derivatives (4-Cl-3-CF341, 4-NO2-3-CF345) exhibiting stronger hDNMT2 inhibition were identified. Based on these findings, the electrophilicity was further increased by replacing the methylenamine substructure with a sulfonamide function. We performed a subsequent SAR study using different aryl sulfonyl building blocks with strong electron-withdrawing groups such as NO2 and CF3 as well as intracyclic nitrogen atoms. By attaching halogen leaving groups, the aromatic rings were adjusted to enable a covalent reaction with the catalytically active cysteine of hDNMT2. Protein mass spectrometry revealed that the 4-halogen-3-NO2-decorated phenylsulfonamide derivatives 78–80 and the 2-chloropyrazine structure 91 reacted covalently with the catalytically active Cys79 in the cytidine site of hDNMT2. However, compounds 79 and 91 exhibited too high reactivity as they also bound to Cys287 on the protein surface. Furthermore, a stability test showed that 79 was quickly inactivated by reaction with DTT (Figure 3). Our results highlighted the nonpromiscuous binding behavior of compounds 78 and 80, which exclusively reacted with the catalytically active Cys79, although four solvent-exposed cysteines can be found in the hDNMT2 crystal structure. The most promising covalent inhibitor turned out to be the 4-Br-3-NO2-phenylsulfonamide derivative 80, with an IC50 value of 1.2 ± 0.1 μM resulting in an improvement of 1 order of magnitude compared to our previously published inhibitors.9 Therefore, it outclasses the natural ligands SAH and SFG. Moreover, compound 80 showed high selectivity toward NSUN2 and NSUN6 (Figure 5). With the discovery of covalent hDNMT2 inhibitors, this study provides a suitable basis for the development of fluorescently ABPs. Such tool compounds can be used for future studies to improve the understanding of RNA methyltransferases and the biological impact of their RNA modifications.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), project numbers 439669440 TRR319 RMaP TP A01 (T.S.), C01, and C03 (M.H.) is gratefully acknowledged. Z.N. gratefully acknowledges financial support by the Volkswagen Stiftung. Financial support for F.L. was provided by LOEWE project TRABITA funded by the Hessian Ministry of Higher Education, Research, and the Arts (HMWK). The Synapt XS instrument was partially funded through project number 461372424 of the German Research Foundation (DFG). Additional support by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (Sachkostenzuschuss to F.L.) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Rebecca Federkiel (University of Mainz) for her practical support with the MST experiments.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ABP

activity-based probe

- 5-FAM

5-carboxyfluorescein

- Dab

2,4-diaminobutyric acid

- DCE

dichloroethane

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DNMT

DNA N-methyltransferase

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FTAD

5-FAM-triazolyl-adenosyl-Dab

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- MST

microscale thermophoresis

- MTase

methyltransferase

- NSUN

NOL1/NOP2/sun domain

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

- SAH

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SFG

sinefungin

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TRIS

tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00062.

Synthesis protocols and analytical data of all compounds, NMR spectra, LC-MS chromatograms of all tested compounds, MST traces, ITC curves, molecular docking results (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ M.S. and R.A.Z. contributed equally.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Mark Helm is a consultant for Moderna Inc.

Supplementary Material

References

- Jonkhout N.; Tran J.; Smith M. A.; Schonrock N.; Mattick J. S.; Novoa E. M. The RNA Modification Landscape in Human Disease. RNA 2017, 23 (12), 1754–1769. 10.1261/rna.063503.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebers R.; Rassoulzadegan M.; Lyko F. Epigenetic Regulation by Heritable RNA. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004296. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Chen Z.-P.; Hu H.; Lei J.; Zhou Z.; Yao B.; Chen L.; Liang G.; Zhan S.; Zhu X.; Jin F.; Ma R.; Zhang J.; Liang H.; Xing M.; Chen X.-R.; Zhang C.-Y.; Zhu J.-N.; Chen X. Sperm MicroRNAs Confer Depression Susceptibility to Offspring. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd7605. 10.1126/sciadv.abd7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Shi J.; Rassoulzadegan M.; Tuorto F.; Chen Q. Sperm RNA Code Programmes the Metabolic Health of Offspring. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15 (8), 489–498. 10.1038/s41574-019-0226-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.; Yan M.; Cao Z.; Li X.; Zhang Y.; Shi J.; Feng G.; Peng H.; Zhang X.; Zhang Y.; Qian J.; Duan E.; Zhai Q.; Zhou Q. Sperm TsRNAs Contribute to Intergenerational Inheritance of an Acquired Metabolic Disorder. Science 2016, 351 (6271), 397–400. 10.1126/science.aad7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Zhang X.; Shi J.; Tuorto F.; Li X.; Liu Y.; Liebers R.; Zhang L.; Qu Y.; Qian J.; Pahima M.; Liu Y.; Yan M.; Cao Z.; Lei X.; Cao Y.; Peng H.; Liu S.; Wang Y.; Zheng H.; Woolsey R.; Quilici D.; Zhai Q.; Li L.; Zhou T.; Yan W.; Lyko F.; Zhang Y.; Zhou Q.; Duan E.; Chen Q. Dnmt2Mediates Intergenerational Transmission of Paternally Acquired Metabolic Disorders through Sperm Small Non-Coding RNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20 (5), 535–540. 10.1038/s41556-018-0087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll M. G.; Kirpekar F.; Maggert K. A.; Yoder J. A.; Hsieh C. L.; Zhang X.; Golic K. G.; Jacobsen S. E.; Bestor T. H. Methylation of TRNAAsp by the DNA Methyltransferase Homolog Dnmt2. Science (80-.) 2006, 311 (5759), 395–398. 10.1126/science.1120976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch A.; Ehrenhofer-Murray A.; Jurkowski T. P.; Lyko F.; Reuter G.; Ankri S.; Nellen W.; Schaefer M.; Helm M. Mechanism and Biological Role of Dnmt2 in Nucleic Acid Methylation. RNA Biol. 2017, 14 (9), 1108–1123. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1191737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwickert M.; Fischer T. R.; Zimmermann R. A.; Hoba S. N.; Meidner J. L.; Weber M.; Weber M.; Stark M. M.; Koch J.; Jung N.; Kersten C.; Windbergs M.; Lyko F.; Helm M.; Schirmeister T. Discovery of Inhibitors of DNA Methyltransferase 2, an Epitranscriptomic Modulator and Potential Target for Cancer Treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 9750. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan A.; Arimondo P. B.; Rots M. G.; Jeronimo C.; Berdasco M. The Timeline of Epigenetic Drug Discovery: From Reality to Dreams. Clin. Epigenetics 2019, 11 (1), 174. 10.1186/s13148-019-0776-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontecave M.; Atta M.; Mulliez E. S-Adenosylmethionine: Nothing Goes to Waste. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004, 29 (5), 243–249. 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrossian T. C.; Clarke S. G. Uncovering the Human Methyltransferasome. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2011, 10, M110.000976. 10.1074/mcp.M110.000976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cesco S.; Kurian J.; Dufresne C.; Mittermaier A. K.; Moitessier N. Covalent Inhibitors Design and Discovery. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 96–114. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyko F. The DNA Methyltransferase Family: A Versatile Toolkit for Epigenetic Regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19 (2), 81–92. 10.1038/nrg.2017.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack K. E.; Höbartner C.; Bohnsack M. T. Eukaryotic 5-Methylcytosine (M5C) RNA Methyltransferases: Mechanisms, Cellular Functions, and Links to Disease. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10, 102. 10.3390/genes10020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q.; Huang M.; Wei Y. Diversity of the Reaction Mechanisms of SAM-Dependent Enzymes. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11 (3), 632–650. 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.; Schapira M. The Promise and Peril of Chemical Probe Negative Controls. ACS Chem. Biol. 2021, 16, 579–585. 10.1021/acschembio.1c00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topliss J. G. Utilization of Operational Schemes for Analog Synthesis in Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 1972, 15 (10), 1006–1011. 10.1021/jm00280a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M.; Miller D.; Macleod A.; Van Wiltenburg J.; Thom S.; St-Gallay S.; Shannon J.; Alanine T.; Onions S.; Strutt I.. Novel Sulfonamide Carboxamide Compounds. WO2019/8025A1, 2019.

- Zimmermann R. A.; Schwickert M.; Meidner J. L.; Nidoieva Z.; Helm M.; Schirmeister T. An Optimized Microscale Thermophoresis Method for High-Throughput Screening of DNA Methyltransferase 2 Ligands. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5 (11), 1079–1085. 10.1021/acsptsci.2c00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rarey M.; Kramer B.; Lengauer T.; Klebe G. A Fast Flexible Docking Method Using an Incremental Construction Algorithm. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 261 (3), 470–489. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.