Abstract

Herein we report the development of an automated deoxygenative C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling of aryl bromide with alcohols to enable parallel medicinal chemistry. Alcohols are among the most diverse and abundant building blocks, but their usage as alkyl precursors has been limited. Although metallaphotoredox deoxygenative coupling is becoming a promising strategy to form C(sp2)-C(sp3) bond, the reaction setup limits its widespread application in library synthesis. To achieve high throughput and consistency, an automated workflow involving solid-dosing and liquid-handling robots has been developed. We have successfully demonstrated this high-throughput protocol is robust and consistent across three automation platforms. Furthermore, guided by cheminformatic analysis, we examined alcohols with comprehensive chemical space coverage and established a meaningful scope for medicinal chemistry applications. By accessing the rich diversity of alcohols, this automated protocol has the potential to substantially increase the impact of C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-coupling in drug discovery.

Keywords: fraction Csp3, deoxygenative coupling, parallel medicinal chemistry, automation

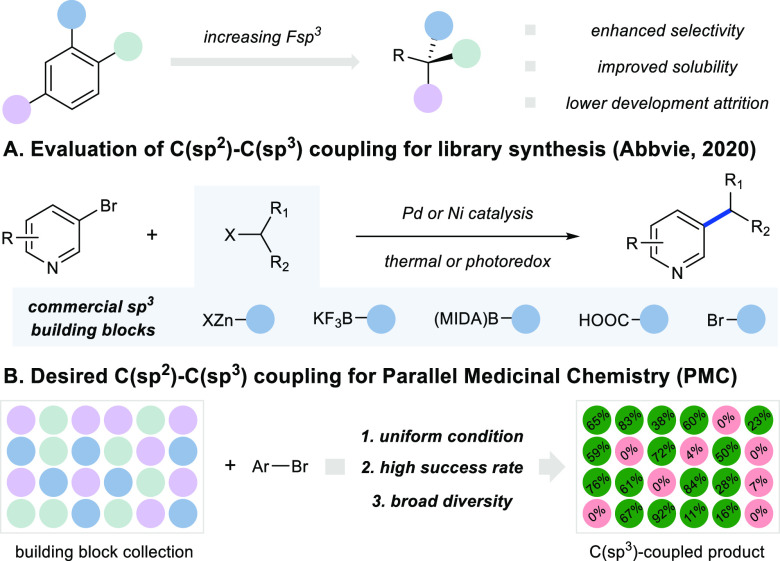

Small molecule drug candidates with flat structures and high fractions of sp2-hybridized C atoms have increased development attrition, driven by poor pharmaceutical properties and off-target activity.1,2 As a result, an increasing fraction Csp3 has become a widespread strategy to enhance solubility and selectivity (Figure 1).1−4 From a synthetic standpoint, the high aromatic ring count in drug candidates can be partly attributed to the widespread adoption of Suzuki-Miyaura coupling by medicinal chemists.5−9 The robust and uniform conditions of Suzuki-Miyaura coupling and the wide availability of the required building blocks have greatly enabled high-throughput library synthesis and extensive exploration of C(sp2) chemical space. On the contrary, challenges associated with C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-coupling have resulted in a much slower uptake by pharmaceutical industry,10−15 despite significant advances in last 10 years, particularly in base-metal catalysis16,17 and photoredox chemistry.18,19

Figure 1.

(A) Evaluation of existing C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-coupling. (B) Desired C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-coupling for PMC.

Parallel medicinal chemistry (PMC) enables rapid optimization of a hit or lead compound via high-throughput analogue synthesis and iterative design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycle. To enable this approach, a highly robust synthetic method with uniform reaction setup and wide reagent availability is required.20 Several analyses of the synthetic methods used in PMC have shown that C-C bond formation is dominated by the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling.5−9 In contrast, C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-couplings in PMC have been limited due to lower reaction generality, requiring the development of substrate-specific reaction conditions in multiple rounds of reaction optimization.10−15 In a recent elegant study by Abbvie evaluating state-of-the-art C(sp2)-C(sp3) couplings, seven catalytic conditions with five classes of commercial building blocks were examined for their applicability in medicinal chemistry (Figure 1A).12 While chemical space coverage could be achieved with multiple conditions and building block classes, a uniform condition was not identified to deliver a high synthesis success rate with a single widely available building block class. Therefore, it remains an important goal to develop novel synthetic methods that enable C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling using a diverse reagent pool with a broad substrate scope (Figure 1B).

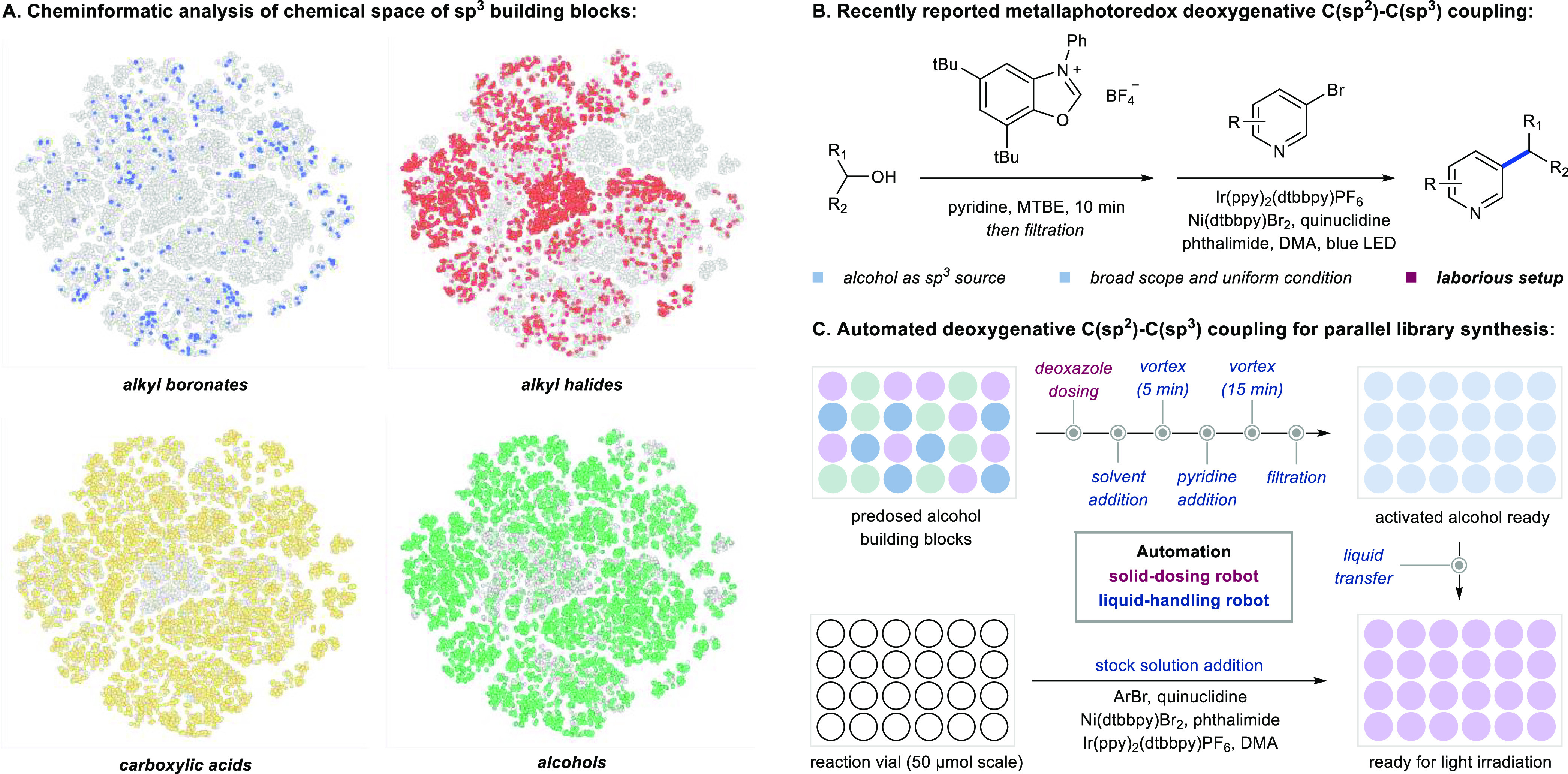

In PMC, the diversity of synthesized compounds is directly linked to the chemical space of building blocks being utilized.21−24 Therefore, in considering a synthetic method for library synthesis, the availability and chemical diversity of its reagent pool becomes imperative.21−24 We conducted cheminformatic analysis on common alkyl precursors for C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling reported in literature including boronates, trifluoroborate salts, alkyl halides (from which organozinc reagents may be derived), carboxylic acids and alcohols (Figure 2A).25,26 Specifically, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) dimensionality reduction of the first 50 principal components using 512-bit Morgan fingerprint descriptors was employed to quantify structural similarities and visualize the commercially accessible chemical space for each sp3 building block.27−29 As shown in Figure 2A, alkyl boronates, including potassium trifluoroborate salts, are commercially available in limited numbers and represent limited chemical diversity. A significant number of alkyl halide building blocks are commercially available, but there are significant gaps in their chemical space coverage. On the contrary, both carboxylic acids and alcohols display high commercial availability (∼14,000 alcohols and ∼17,000 carboxylic acids)30 and wide chemical diversity, rendering both optimal building blocks for introducing chemically diverse Csp3 character.

Figure 2.

(A) Chemical space and diversity analysis of sp3 building blocks. (B) A recently reported deoxygenative coupling reaction. (C) Automated deoxygenative C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-coupling.

Recently, the MacMillan group reported a novel metallaphotoredox-enabled deoxygenative C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling of aryl bromides and alcohols.31 Recognizing the vast number and chemical diversity of alcohol building blocks, the authors developed this innovative method and characterized its performance using uniform conditions, a broad scope of drug-like substrates, and a wide range of primary, secondary, tertiary, benzylic, and basic amine containing alcohol building blocks (Figure 2B).31 Our initial experience applying this methodology in parallel medicinal chemistry confirmed its potential to dramatically improve the synthesis of high Csp3 drug candidates, but the reaction setup proved labor-intensive and time-consuming. In addition, and presenting a greater challenge for high-throughput synthesis, the alcohols need to undergo in situ activation followed by filtration and addition of the filtrate to a stock solution of the remaining reactants. To maximize conversion, these manipulations must be conducted under an inert atmosphere.31

Automated solid-dosing robots and liquid handlers have successfully addressed similar challenges across a range of reactions, performing repetitive tasks and delivering high reproducibility.32−34 We became interested in developing an automated workflow to enable deoxygenative C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling for parallel medicinal chemistry (Figure 2C).35,36 We envisioned the weighing and dosing of the deoxazole reagent could be achieved by solid-dispensing robotics and the complex sequence of liquid addition/transfer, vortex and filtration could be accomplished by automated liquid handlers. By housing the robotics inside a purge box, the reaction yields would be maximized without the need for manual setup, filtration, liquid transfer or solvent sparging.

Validation studies used methyl 5-bromopicolinate 1 and 1-Boc-3-hydroxypiperidine 2 as model substrates in a 24-well plate format (Table 1). Solid dispensing was performed using the Chronect Quantos and liquid handling and filtration was carried out using an Unchained Laboratories (UL) Junior robotic system housed inside a nitrogen purge box (O2 level <20 ppm). Due to dead volume considerations of liquid transfer by robots, 3.5 equiv of alcohol, which is usually the less costly and more abundant coupling partner, proved optimal. Using the UL Junior to automate the reaction manipulations described in the original deoxygenative coupling publication,31 the 24-well plate delivered highly consistent results with an average 89% yield and standard deviation of 0.7%. This demonstrated the reproducibility of the automated workflow and increased confidence in pursuing subsequent scope studies. Notably, the whole sequence on UL Junior was completed in ∼1 h, whereas manual work to execute a 24-compound library synthesis in the purge box would take ∼3 h, underscoring the efficiency of automation with high precision.

Table 1. Cross-Platform Validation of Automated Workflowa.

Yield determined by UPLC analysis on reaction crude.

With a validated automation workflow in hand, we examined the applicability of the deoxygenative coupling in the context of PMC. To benchmark, we selected 24 alcohols that contain the identical alkyl fragments evaluated in the Abbvie study (vide supra) across different C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling conditions (Table 2).12 Using only one uniform automated deoxygenative coupling condition, 18 out of 24 alcohols yielded satisfactory results (>10% isolated yield). With a larger reagent pool, the deoxygenative coupling provided comparative yields and functional group tolerance as the other cross-coupling reactions, with primary, secondary, and primary benzylic alcohols using a single method. Limitations in substrate scope are consistent with prior reports: for example, basic amines are challenging substrates for nickel photoredox chemistry (A12), α-oxy and α-amino alcohols were low yielding (A22) and tertiary (A24) or secondary benzylic (A10) C(sp3) centers were challenging.

Table 2. A Comprehensive Evaluation of sp3 Space Coverage by Automated Deoxygenative C(sp2)-C(sp3) Cross-Couplinga.

Isolated yields. Reaction performed on UL Junior system. See Supporting Information for detailed protocol and reaction condition.

17% yield with manual setup.

Primary alcohol was reacted.

Product isolated as the boronic acid.

Secondary alcohol was reacted.

The ease and throughput of our automated protocol prompted us to examine alcohols with more chemical space coverage to establish an expanded scope for medicinal chemistry applications. Using t-SNE analysis, we visualized the chemical space covered by previously examined alkyl fragments (represented as blue dots in Table 2) and mapped out space that has not been explored in C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling before. Within this space, we selected 48 alcohol building blocks (represented by orange dots in Table 2) based on drug-likeness (heterocycles, hydrogen-bond donors/acceptors, lipophilicity) and functional group diversity (nitrile, ketone, protic groups) to probe the performance of the automated deoxygenative coupling. The synthesis success rate was high, with 32 out of 48 alcohols yielding satisfactory results (>10% isolated yield). A variety of heterocycles and functional groups were successfully tolerated such as pyridine, imidazole, pyrazole, amide, ketone, aldehyde, alcohol, boronate and nitrile. Notably, all secondary benzylic alcohols were unsuccessful coupling partners, despite extensive explorations (B41–B45). Hydroxyl groups that are α to carbonyl groups are also a low-yielding substrate class with the exception of β-lactam (B33). Furthermore, the coupling of tertiary alcohols to form quaternary centers was found to be challenging (B30, B38 and B46).

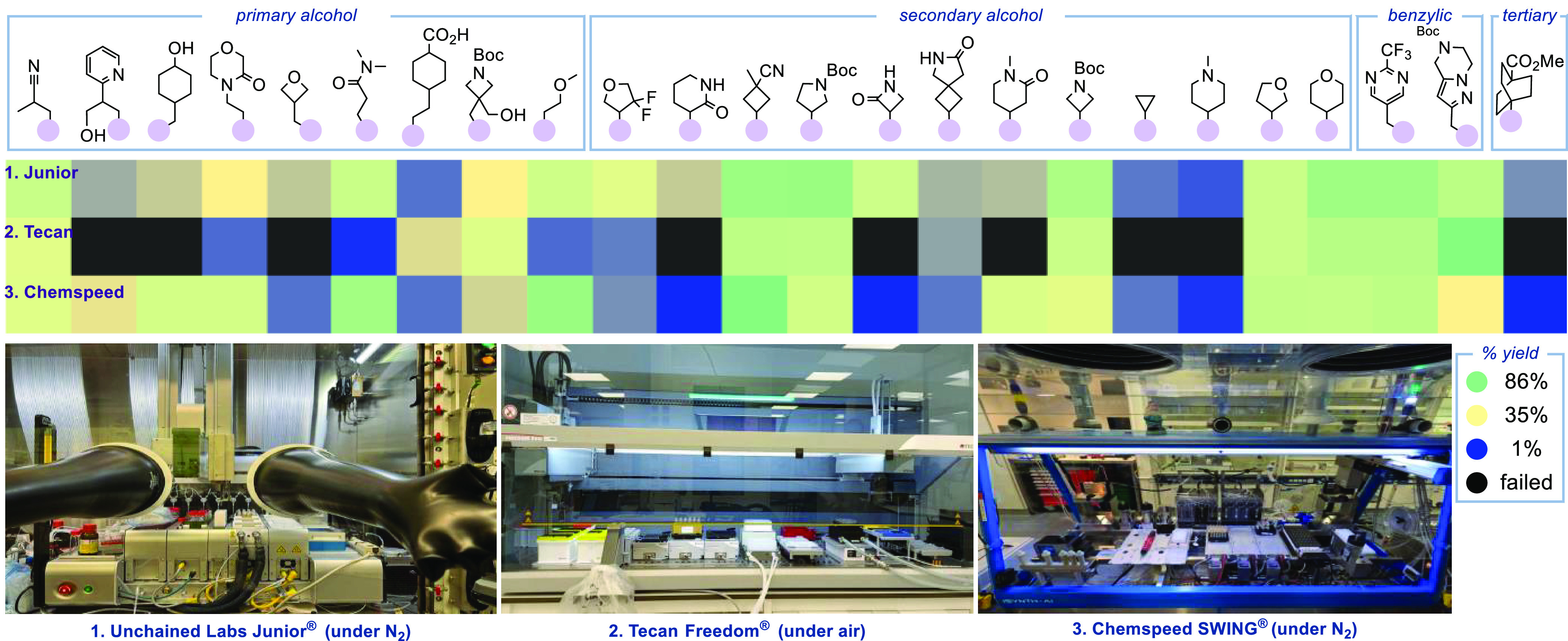

Because medicinal chemists have access to a variety of automation platforms, we validated the novel automated deoxygenative coupling on multiple systems (Table 1). The results are consistent across platforms: The new automated protocol provides consistent yields, dramatically accelerates the time-consuming manual manipulations, and provides high precision, reproducible data. Our validation study included these configurations: (1) Chronect Quantos (solid dispensing) + UL Junior (liquid handling), inert atmosphere; (2) Chronect Quantos (solid dispensing) + Tecan Freedom (liquid handling), ambient atmosphere; and (3) Chemspeed GDU (solid and liquid dispensing), inert atmosphere. Importantly, Tecan’s automated sequence was conducted outside the inert atmosphere without precautions to exclude moisture or oxygen, which only led to a small compromise of yield (avg. 5% lower). For the Chemspeed, a slow flow rate of liquid aspiration and dispense was found to be critical to ensure consistent distribution of stock solutions (see Supporting Information for detailed description of automation protocols).

To examine these automated protocols under PMC setting, a diverse set of alcohol building blocks encompassing primary, secondary, benzylic and tertiary alcohols was used in the automated deoxygenative coupling in all three automation platforms (Figure 3). Despite the significant differences in their operating environments, highly comparable results were observed across platforms, demonstrating the generality of the automated deoxygenative coupling (see Supporting Information for detailed results).

Figure 3.

Cross-platform evaluation of the automated deoxygenative C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling at Jansen Global Discovery Chemistry.

To further demonstrate the utility of the automated protocol, the aryl bromide reactant was varied. Ten complex, drug-like aryl bromides were selected to react with 2 alcohols in library format and automated on the UL Junior system (Table 3).37 Eight of 10 aryl bromides furnished product in synthetically useful yields (average 50% isolated), tolerating a wide range of functional groups and nitrogen-rich heterocycles. These results, along with our experience applying the automated deoxygenative coupling on medicinal programs at Janssen, increase confidence in the wide applicability of the automated protocol. Additionally, we also found that the scale-up of this reaction can be enabled by flow photoreactor, furnishing gram quantity of C(sp3)-coupled product in one run (0.6 mmol/h, see Supporting Information).

Table 3. PMC Library of Aryl Bromide in Automated Deoxygenative C(sp2)-C(sp3) Couplinga.

Isolated yields.

To conclude, we have successfully developed an automated protocol to achieve C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling of aryl bromide with alcohols for PMC. This study establishes the advantage of using automation to achieve operationally challenging synthetic transformations with improved throughput and consistency. Despite differences in automation technologies, our high-throughput protocol is robust and consistent across various robotic platforms. By harnessing the rich diversity of alcohol building blocks, this automated deoxygenative coupling protocol has the potential to dramatically increase the impact of C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-coupling in drug discovery. For future applications, the consistency of this automated workflow opens the door to conducting high-throughput experimentation on the deoxygenative coupling, which may dramatically accelerate the discovery of new conditions to enable challenging substrates. Furthermore, the high-quality data generated in this fashion could also be utilized in the artificial intelligence/machine learning model for reaction prediction.38−40

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Christopher Reiher and Dr. Peter Buijnsters for helpful discussions. We thank Dr. Fan Huang for help in obtaining HRMS data.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DMA

dimethylacetamide

- DMTA

design, make, test, analyze

- GDU

gravimetric dispensing units

- MIDA

methyliminodiacetic acid

- PMC

parallel medicinal chemistry

- t-SNE

t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

- UPLC

ultraperformance liquid chromatography

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00118.

Author Contributions

# These authors contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Dedication

The authors dedicate this work to the memory of our colleague and mentor, Pei-Pei Kung.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lovering F.; Bikker J.; Humblet C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6752–6756. 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaiah M. A. M.; Meanwell N. A. Bioisosteres of the Phenyl Ring: Recent Strategic Applications in Lead Optimization and Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 14046–14128. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M.; Hashimoto Y. Improvements in Aqueous Solubility in Small Molecule Drug Discovery Programs by Disruption of Molecular Planarity and Symmetry. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1539–1554. 10.1021/jm101356p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W.; Cherukupalli S.; Jing L.; Liu X.; Zhan P. Fsp3: a new parameter for drug-likeness. Drug Discovery Today 2020, 25, 1839–1845. 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughley S. D.; Jordan A. M. The Medicinal Chemist’s Toolbox: An Analysis of Reactions Used in the Pursuit of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3451–3479. 10.1021/jm200187y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters W. P.; Green J.; Weiss J. R.; Murcko M. A. What do medicinal chemists actually make? A 50-year retrospective. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6405–6416. 10.1021/jm200504p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider N.; Lowe D. M.; Sayle R. A.; Tarselli M. A.; Landrum G. A. Big Data from Pharmaceutical Patents: A Computational Analysis of Medicinal Chemists’ Bread and Butter. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4385–4402. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G.; Bostrom J. Analysis of Past and Present Synthetic Methodologies on Medicinal Chemistry: Where Have All the New Reactions Gone?. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4443–4458. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boström J.; Brown D. G.; Young R. J.; Keserü G. M. Expanding the medicinal chemistry synthetic toolbox. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2018, 17, 709–727. 10.1038/nrd.2018.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher S. D.; Dormer P. G.; Sandrock D. L.; Molander G. A. Efficient Cross-Coupling of Secondary Alkyltrifluoroborates with Aryl Chlorides – Reaction Discovery Using Parallel Microscale Experimentation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9257–9259. 10.1021/ja8031423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R.; Li G.; Wismer M.; Vachal P.; Colletti S. L.; Shi Z.-C. Profiling and Application of Photoredox C(sp3)-C(sp2) Cross-Coupling in Medicinal Chemistry. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 773–777. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski A. W.; Gesmundo N. J.; Aguirre A. L.; Sarris K. A.; Young J. M.; Bogdan A. R.; Martin M. C.; Gedeon S.; Wang Y. Expanding the Medicinal Chemist Toolbox: Comparing Seven C(sp2)-C(sp3) Cross-Coupling Methods by Library Synthesis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 597–604. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutner G. L.; Simmons E. M.; Ayers S.; Bemis C. Y.; Goldfogel M. J.; Joe C. L.; Marshall J.; Wisniewski S. R. A Process Chemistry Benchmark for sp2-sp3 Cross Couplings. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 10380–10396. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c01073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speckmeier E.; Maier T. C. ART-An Amino Radical Transfer Strategy for C(sp2)–C(sp3) Coupling Reactions Enabled by Dual Photo/Nickel Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 9997–10005. 10.1021/jacs.2c03220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdiaj I.; Cañellas S.; Dieguez A.; Linares M. L.; Pijper B.; Fontana A.; Rodriguez R.; Trabanco A.; Palao E.; Alcázar J. End-to-End Automated Synthesis of C(sp3)-Enriched Drug-like Molecules via Negishi Coupling and Novel, Automated Liquid–Liquid Extraction. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 716–732. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasker S. Z.; Standley E. A.; Jamison T. F. Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 2014, 509, 299–309. 10.1038/nature13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weix D. J. Methods and Mechanisms for Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Csp2 Halides with Alkyl Electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1767–1775. and references cited therein. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. Y.; Perry I. B.; Bissonnette N. B.; Buksh B. F.; Edwards G. A.; Frye L. I.; Garry O. L.; Lavagnino M. N.; Li B. X.; Liang Y.; Mao E.; Millet A.; Oakley J. V.; Reed N. L.; Sakai H. A.; Seath C. P.; MacMillan D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox: The Merger of Photoredox and Transition Metal Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1485–1542. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan J. A.; Phelan J. P.; Badir S. O.; Molander G. A. Alkyl Carbon–Carbon Bond Formation by Nickel/Photoredox Cross-Coupling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6152–6163. and references cited therein. 10.1002/anie.201809431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper T. W. J.; Campbell I. B.; Macdonald S. J. F. Factors determining the selection of organic reactions by medicinal chemists and the use of these reactions in arrays (small focused libraries). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 8082–8091. 10.1002/anie.201002238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalliokoski T. Price-Focused Analysis of Commercially Available Building Blocks for Combinatorial Library Synthesis. ACS Comb. Sci. 2015, 17, 600–607. 10.1021/acscombsci.5b00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seierstad M.; Tichenor M. S.; DesJarlais R. L.; Na J.; Bacani G. M.; Chung D. M.; Mercado-Marin E. V.; Steffens H. C.; Mirzadegan T. Novel Reagent Space: Identifying Unorderable but Readily Synthesizable Building Blocks. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 1853–1860. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Haight I.; Gupta R.; Vasudevan A. What Is in Our Kit? An Analysis of Building Blocks Used in Medicinal Chemistry Parallel Libraries. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 17115–17122. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabolotna Y.; Volochnyuk D. M.; Ryabukhin S. V.; Horvath D.; Gavrilenko K. S.; Marcou G.; Moroz Y. S.; Oksiuta O.; Varnek A. A Close-up Look at the Chemical Space of Commercially Available Building Blocks for Medicinal Chemistry. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 2171–2185. 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariofillis S. K.; Jiang S.; Zuranski A. M.; Gandhi S. S.; Martinez Alvarado J. I.; Doyle A. G. Using Data Science To Guide Aryl Bromide Substrate Scope Analysis in a Ni/Photoredox-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling with Acetals as Alcohol-Derived Radical Sources. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 1045–1055. 10.1021/jacs.1c12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felten S.; He C. Q.; Weisel M.; Shevlin M.; Emmert M. H. Accessing Diverse Azole Carboxylic Acid Building Blocks via Mild C-H Carboxylation: Parallel, One-Pot Amide Couplings and Machine-Learning-Guided Substrate Scope Design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 23115–23126. 10.1021/jacs.2c10557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Maaten L.; Hinton G. Visualizing Data Using T-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K.; Chupakhin V.; Vos A.; Morrison D.; Rassokhin D.; Dellwo M. J.; McCormick K.; Paternoster E.; Ceulemans H.; DesJarlais R. L. Development and Implementation of an Enterprise-wide Predictive Model for Early Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion Properties. Future Med. Chem. 2021, 13, 1639–1654. 10.4155/fmc-2021-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visualizing Chemical Space, 2020.https://github.com/PatWalters/workshop/blob/master/predictive_models/2_visualizing_chemical_space.ipynb (accessed March 14, 2023).

- Based on Enamine building block collection. https://enamine.net/building-blocks (accessed October 2022).

- Dong Z.; MacMillan D. W. C. Metallaphotoredox-Enabled Deoxygenative Arylation of Alcohols. Nature 2021, 598, 451–456. 10.1038/s41586-021-03920-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider G. Automating drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2018, 17, 97–113. 10.1038/nrd.2017.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M.; Yunker L. P. E.; Shiri P.; Zepel T.; Prieto P. L.; Grunert S.; Bork F.; Hein J. E. Automation isn’t automatic. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 15473–15490. 10.1039/D1SC04588A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranczak A.; Tu N. P.; Marjanovic J.; Searle P. A.; Vasudevan A.; Djuric S. W. Integrated Platform for Expedited Synthesis-Purification-Testing of Small Molecule Libraries. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 461–465. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q.; Ma G.; Gong H. Ni-Catalyzed Formal Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Alcohols with Aryl Halides. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 14102–14109. 10.1021/acscatal.1c04239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chi B. K.; Widness J. K.; Gilbert M. M.; Salgueiro D. C.; Garcia K. J.; Weix D. J. In-Situ Bromination Enables Formal Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Alcohols with Aryl and Alkenyl Halides. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 580–586. 10.1021/acscatal.1c05208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutchukian P. S.; Dropinski J. F.; Dykstra K. D.; Li B.; DiRocco D. A.; Streckfuss E. C.; Campeau L.-C.; Cernak T.; Vachal P.; Davies I. W.; Krska S. W.; Dreher S. D. Chemistry informer libraries: a chemoinformatics enabled approach to evaluate and advance synthetic methods. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 2604–2613. 10.1039/C5SC04751J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahneman D. T.; Estrada J. G.; Lin S.; Dreher S. D.; Doyle A. G. Predicting Reaction Performance in C-N Cross-Coupling Using Machine Learning. Science 2018, 360, 186–190. 10.1126/science.aar5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.; Struble T. J.; Coley C. W.; Wang Y.; Green W. H.; Jensen K. F. Using Machine Learning to Predict Suitable Conditions for Organic Reactions. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 1465–1476. 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves P.; McClure K.; Verhoeven J.; Dyubankova N.; Nugmanov R.; Gedich A.; Menon S.; Shi Z.; Wegner J. K. Global reactivity models are impactful in industrial synthesis applications. J. Cheminform 2023, 15, 20. 10.1186/s13321-023-00685-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Based on Enamine building block collection. https://enamine.net/building-blocks (accessed October 2022).