Abstract

Recent years have seen significant advances in compact, portable capillary LC instrumentation. This study explores the performances of several commercially available columns within the pressure and flow limits of both the columns and one of these compact LC instruments. The commercially available compact capillary LC system with UV-absorbance detector used in this study is typically operated using columns in the 0.15 – 0.3 mm internal diameter (i.d.) range. Efficiency measurements (i.e., theoretical plates, ) for six columns with i.d.s in this range and of varying lengths and pressure limits, packed with stationary phases of different particle diameters and morphologies, were made using a mixture of standard alkylphenones. Kinetic plot comparisons between columns that vary by one (or more) of these parameters are described, along with calculated kinetic performance and Knox-Saleem limits. These theoretical performance descriptions provide insight into optimal operating conditions when using capillary LC systems. Based on kinetic plot evaluation of available capillary columns in the 0.2 – 0.3 mm i. d. range with a conservative upper pressure limit of 330 bar packed with superficially porous particles, a 25 cm column could generate ~47,000 plates in 7.85 min when operated at 2.4 μL/min. For comparison, more robust 0.3 mm i.d. columns (packed with fully porous particles) that can be operated at higher pressures than can be provided by the pumping system (conservative pump upper pressure limit of 570 bar), a ~20 cm column could generate nearly 40,000 plates in 5.9 min if operated at 6 μL/min. Across all capillary LC columns measured, higher pressure limits and shorter columns can provide the best throughput when considering both speed and efficiency.

Keywords: Capillary Liquid Chromatography, Compact, Portable, Kinetic Plot, Chromatographic Efficiency

1. Introduction

Reduction in solvent usage is a primary goal of green analytical chemistry [1-4], and for liquid chromatography (LC), this can be most easily achieved through a reduction in mobile phase consumption [5,6]. With analytical-scale high pressure LC (i.e., HPLC), this has been achieved by reducing column internal diameter (i.d.) from 4.6 mm down to 3.0 mm [7]. In ultrahigh pressure HPLC (UHPLC), where 2.1 mm i.d. columns have been typically used because of performance losses that can occur due to viscous friction at pressures exceeding 400 bar, 1.5 mm i.d. columns have recently demonstrated comparable separation performance while reducing mobile phase flow rates by approximately 50% [8,9]. However, to truly achieve the greatest reduction in mobile phase consumption, capillary- and nano-scale LC columns are most effective because of their dramatically reduced flow rates [6].

With the recent advent of integrated, compact capillary LC instruments [10-13], which simplify operation and minimize extra-column volume, there is now greater potential to broaden the adoption of capillary-scale LC techniques. These systems have recently been used for the characterization of biocides [14], cannabinoids [13,15], polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) [16], perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) [17], pharmaceutical compounds [13,18], and illicit drug compounds [13,19], as well as for on-line reaction monitoring [11,18]. To enhance UV-absorbance detector sensitivity when using capillary LC, flow cells with long pathlengths have been developed [20,21]. However, longer pathlength, which leads to greater detector flow cell volume, can reduce chromatographic performance due to increased extra-column band broadening. Placing an on-capillary light-emitting diode (LED) UV-absorption detector directly adjacent to the column outlet frit adds minimal extra-column volume, but limits the pathlength to the capillary column i.d. (e.g., 150 μm for a 150 μm i.d. column) [22].

In this report, a re-designed version of an on-capillary LED UV-absorption detector that uses similar optics but integrates a z-cell design that increases the pathlength to 1.2 mm is described. To accommodate the increase in detector volume, column internal diameters of 200 μm and 300 μm were investigated. Specifically, the effects of column length, column i.d., and particle size/morphology on separation performance were measured within the limitations of each column maximum operating pressure limit, the LC instrument maximum pressure limit, and the balance between mobile phase flow rate and analysis time. For such comparisons, the kinetic plot approach with emphasis on the overall kinetic performance limit (KPL) for a given set of operating conditions was adopted [23]. These results provide guidance on column selection within the given parameters afforded by modern compact capillary LC instrumentation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Other Materials

HiPerSolv HPLC grade water and acetonitrile were purchased from VWR (Radnor, PA, USA) for use in mobile phases and sample diluent. HPLC grade trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Sample analytes (all at least 99% purity) included thiourea and propiophenone purchased from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ, USA), and acetophenone and butyrophenone obtained from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). The dimensions and stationary phase morphology of columns used in this study are listed in Table 1. Columns 1-5 in this table were acquired from Advanced Materials Technology (Wilmington, DE, USA) and columns 6 and 7 were acquired from Waters (Milford, MA, USA). Example chromatograms from each column are shown in the Supporting Information. The new LED-UV detector housing was manufactured by GearWurx (Nibley, UT, USA) and utilizes a capillary electrophoresis (CE) high sensitivity flow cell (p/n G1600-60027) from Agilent Technologies (Waldbronn, Germany).

Table 1.

Description of columns used in this investigation.

| Column Number |

ID (mm) |

Length (mm) |

Particle Diameter (μm) |

Particle Morphology | Column Pressure Limit (bar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.2 | 50 | 2.7 | Superficially Porous | 400 |

| 2 | 0.2 | 100 | 2.7 | Superficially Porous | 400 |

| 3 | 0.2 | 150 | 2.7 | Superficially Porous | 400 |

| 4 | 0.2 | 100 | 5 | Superficially Porous | 400 |

| 5 | 0.3 | 50 | 2.7 | Superficially Porous | 400 |

| 6 | 0.3 | 50 | 1.8 | Fully Porous | 1000 |

| 7 | 0.3 | 150 | 1.8 | Fully Porous | 1000 |

2.2. Instrumentation and Methodology

All chromatographic data were collected using a Focus LC instrument (Axcend, Provo, UT, USA). Columns were connected to the injector valve (40 nL internal loop) using a 15 cm length of tubing, and the column inlet was connected to the detector flow cell using a 5 cm length of tubing (both PEEKsil, 25 μm i.d.). A 255 nm LED was used as the detector light source. Mobile phase A was 97:3 water/acetonitrile and mobile phase B was 3:97 water/acetonitrile, both with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. A sample mixture of thiourea (void time marker), acetophenone, propiophenone, and butyrophenone (all 50 ppm) was used for column characterization. Mobile phase composition for isocratic analysis varied between 42% B and 51% B to achieve a retention factor of approximately 5 for butyrophenone on all columns tested. Each column was initially operated at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/min, which was then increased until a set threshold of 82.5% of the maximum pressure (either column or instrument, whichever was lower) had been reached. This threshold was selected because in the pressurization and equilibration phase of the flow sequence, pressures can rise higher than the equilibrated operating pressure. It was therefore necessary to set at a set pressure below the maximum pressure to avoid exceeding the limit of either the column or system (whichever was lower). The sample mixture was injected in triplicate for each flow rate. Data were acquired using the Axcend Drive software and transferred to Igor Pro 6.0 (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA) for the calculation of plate counts (based on full width at half max) and the generation of kinetic plots.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Updated Design of Detector Optics to Integrate the Flow Cell

With the use of a direct on-capillary LED UV-absorption detector [22], post-column broadening is nearly eliminated, although the detector pathlength is limited to the i.d. of the column itself. In one version of the Axcend Focus LC [13], a 100 mm long, 0.150 mm i.d. column is followed by an on-capillary detector placed immediately at the exit of the outlet frit. With a standard slit width of 0.1 mm, the detector cell volume was calculated to be 1.8 nL. In a more recent detector design (Figure 1), a flow cell with a 1.2 mm pathlength (100 μm i.d. channel) is used to increase overall signal intensity nearly eight-fold and signal-to-noise ratio more than three-fold (see Supporting Information). However, this increases the detector volume to 12 nL and requires the use of a short length of small i.d. connection tubing between the column outlet and detector flow cell (in our case, adding an extra-column volume of 24.5 nL). The net result is a 20-fold increase in detector-associated volume, which slightly reduces the expected gain in signal intensity based on pathlength ratio due to the additional post-column broadening. To reduce the effect of this added extra-column volume on chromatographic performance, the column diameter can be increased to 200 μm or 300 μm i.d., which increases the column volume by 1.8-fold or 4-fold, respectively. Since commercial columns are readily available in these diameters, the variety of stationary phases that can be utilized with the compact capillary LC instrument is expanded significantly. In the following section, the effects of various column parameters on chromatographic efficiency based on new choices afforded by this increase in column i.d. are explored using kinetic plot analysis.

Figure 1.

Schematic of new UV-absorbance detector module for use in a capillary column cartridge. Light from a UV LED source is focused through a z-shaped flow cell with a ball lens. Transmitted light is then detected by a photodiode on the opposite end of the detector flow cell optical path.

3.2. Kinetic Plot Characterization of Capillary LC Columns with Varying Lengths and the Same Upper Pressure Limit

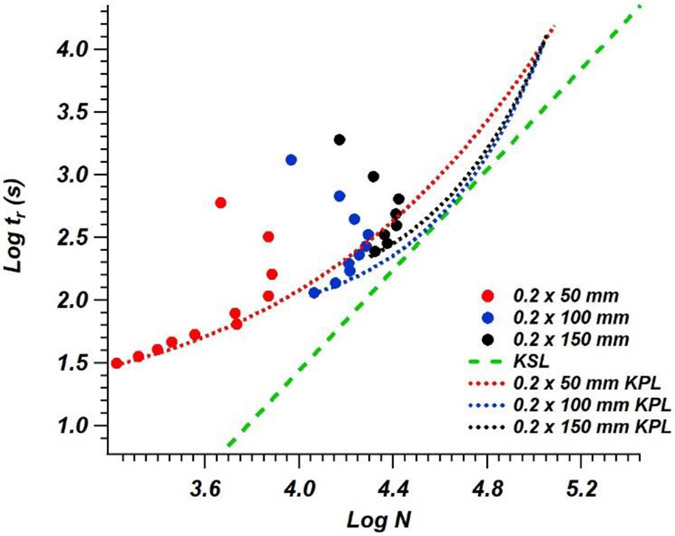

Kinetic plots are a commonly used graphical approach to compare chromatographic efficiency and method throughput for columns with different dimensions and/or stationary phase morphologies. In this study, kinetic plots were used to assess these characteristics and compare capillary LC columns that were appropriate for use with the new detector format described in Section 3.1. Initially, three 200 μm i.d. columns of varying lengths, all packed with 2.7 μm superficially porous particles, were compared (Columns 1-3 in Table 1). Because a maximum pressure limit of 400 bar was specified for all three columns, the maximum flow rate (and thus, highest mobile phase velocity) that could be achieved decreased with increasing column length (). Combined with the inherent increase in hold-up time for longer columns, if all columns were operated at the same linear velocity, the shortest analysis time (represented by the lowest y-axis position for the retention time of the last eluting peak in the kinetic plot) is observed with the 50 mm long column (Figure 2). By increasing the column length, higher chromatographic efficiency is achieved (especially at the furthest point along the x-axis on each, which represents the maximum chromatographic efficiency), albeit with longer total analysis time.

Figure 2.

Kinetic plot comparison of 50 mm x 0.2 mm i.d. (red points), 100 mm x 0.2 mm i.d. (blue points), and 150 mm x 0.2 mm i.d. (black points) columns packed with 2.7 μm superficially porous particles. KPL curves for each column are fit with the matching color dotted lines and the KSL is represented by a green dashed line.

The lowest point on the y-axis for each curve represents the highest pressure at which the column was operated and identifies the highest efficiency that can be observed within a given time. This point can be defined as the kinetic performance limit (KPL) [24]. To extrapolate the values that could be observed for any given column length with a set maximum pressure, the retention time () and plate count () can be calculated using Equations 1 and 2 [23]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

In these equations, represents the mobile phase viscosity calculated based on [25], represents the maximum pressure limit, and represents the experimentally determined plate height [23]. The column permeability, , is calculated by plotting vs (the mobile phase linear velocity) and observing the slope (equal to ). It is important to note that as column length decreases, the effects of extra column band broadening become increasingly apparent, with observed and plate heights shifting by ~15% from a 50 mm long column to a 150 mm long column. In order to account for this, and plate counts were adjusted for extra-column effects based on recommendations described in [26] and [27]. In Figure 2, a KPL curve was constructed based on experimental data from Column 2. Because experimental column pressures did not exceed 82.5% of the maximum value to avoid bed disruptions and/or leaks in column connections, the KPL was calculated for slightly lower than the maximum pressure limit of the column. As plate count increases linearly, the separation time required to achieve these plates increases exponentially, which is expected because longer columns must be used to achieve higher plate counts. However, to remain below , the flow rate (and therefore, linear velocity) must be reduced to account for the additional column length. Equations 1 and 2 show that this reduction impacts retention times exponentially and plate counts linearly.

At a given , the Knox-Saleem Limit (KSL) represents an efficiency that cannot be exceeded by merely changing the flow rate, column dimensions, or particle size [28]. The KSL can be graphed on a kinetic plot based on the following relationship [28]:

| (3) |

where is the minimum plate height. A KSL curve is shown in Figure 2. The KSL line is tangential to the KPL curve, and the intersection of these lines represents the optimal plates per minute achievable for any given particle size. There are some limits to this approach that sometimes limit the full intersection of the KPL curve and KSL line. This error that is primarily seen when using shorter columns (e.g., 50 mm length column in Figure 2) related to assumptions of values that are independent of length. However, this assumption is often not the case due to differences in packing quality between columns of different lengths and broadening contributions from column hardware [29,30]. However, it still provides a reasonable estimate of where optimal performance would theoretically be observed. Based on the experimental observations for these 200 μm i.d. columns with a 330 bar pressure limit (again selected for an operating value of 82.5% of the column pressure limit), the extrapolated intersection point for optimal plates per time predicts that a 30 cm long column operated at 2 μL/min would have a hold-up time around 113 s and would generate over 58,000 theoretical plates. By modeling the maximum performance of various commercially available columns packed with similar particles, the column dimensions required for the highest plate generation in the least amount of time can be predicted. However, these specific column dimensions, and others mentioned later in the article related to this intersection point, may not be readily available to users. In practical operation, based on column dimensions that are widely commercially available and lengths that are compatible with the column cartridge design used in this system, a 25 cm column could be utilized to achieve ~47,000 plates in 7.85 min when operated at 2.4 μL/min.

3.3. Additional Column Parameters to Consider with Compact Capillary LC Instrumentation

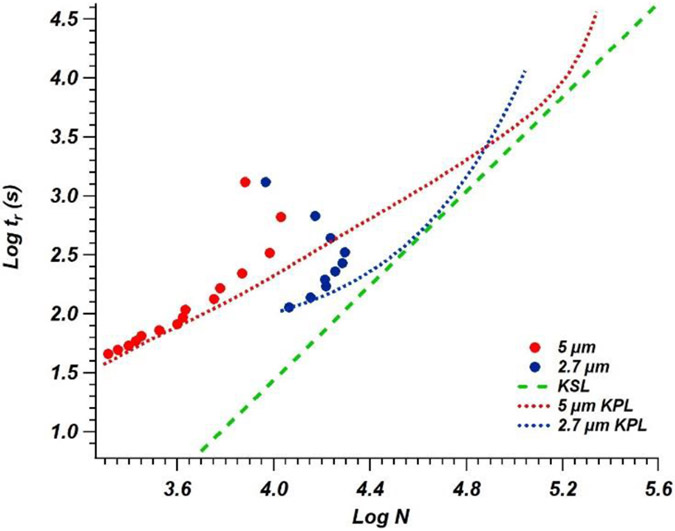

In addition to column length, several other comparisons between various column parameters were made using a similar kinetic plot approach. In Figure 3, kinetic plots for two 100 mm long columns (both 200 μm i.d.) are shown. Both were packed with superficially porous particles, with one column containing 2.7 μm diameter particles while the other column contained 5 μm diameter particles (Columns 2 and 4 in Table 1). Although lower efficiency was expected for the larger particles, the lower flow resistance enabled higher flow rates near the column operating pressure limit. By generating KPL curves (Figure 3), it is shown that the 2.7 μm particles offer higher efficiencies when columns of shorter lengths are compared; however, as column lengths are increased, the pressures generated with smaller particles require a reduction in linear velocity to remain below . This reduction in linear velocity increases the analysis time to a point at which similar plate counts can be achieved in shorter time using columns packed with larger particles. By observing the intersection of the KSL line with the KPL curves calculated with a 330 bar column limit, the peak efficiency of a 1.44 m long column containing 5 μm particles operated at 1 μL/min exceeds ~154,000 plates. In comparison, a 1.2 m long column containing 2.7 μm particles operated at 0.5 μL/min (the minimum programmable flow rate with this system) would achieve slightly less than 110,000 plates at the same column pressure limit. However, these column lengths are somewhat impractical as the analysis times would be prohibitively long. For the 1.44 m column described above, would be nearly 18 min and a peak with would result in a total analysis time of just under 2 h per sample, which is not viable for routine testing. Moreover, because the flow rate is generated using two 135 μL syringes, a 1 μL/min flow rate of 42% B could only be maintained for 232 min before the pumps would have to be refilled. Depending on the solvent composition and retention factor of the last eluting peak, it may not be possible to complete some runs without a syringe refill cycle.

Figure 3.

Kinetic plot comparison of 100 mm x 0.2 mm i.d. columns packed with 2.7 μm (blue points) and 5.0 μm (red points) superficially porous particles. KPL curves for each column are fit with the matching color dotted lines and the KSL is represented by matching color dashed lines.

All of the columns examined in the comparisons described above had a 400 bar pressure limit (with an operating limit set at 330 bar), which falls below the maximum operating pressure of the capillary LC instrument (690 bar) and precludes the attainment of better chromatographic efficiency that may be achieved at higher pressures. There are few commercially available capillary LC columns that have internal diameters in the 200 – 300 μm i.d. range, upper pressure limits that exceed 400 bar, and correct end fittings to be easily utilized in the capillary LC system used in this study. Of those that were available, Columns 6 and 7 (Table 1) were included in this study because of their 1000 bar limit, which permitted an increase in maximum operating pressure to 690 bar limited now by the pumps.

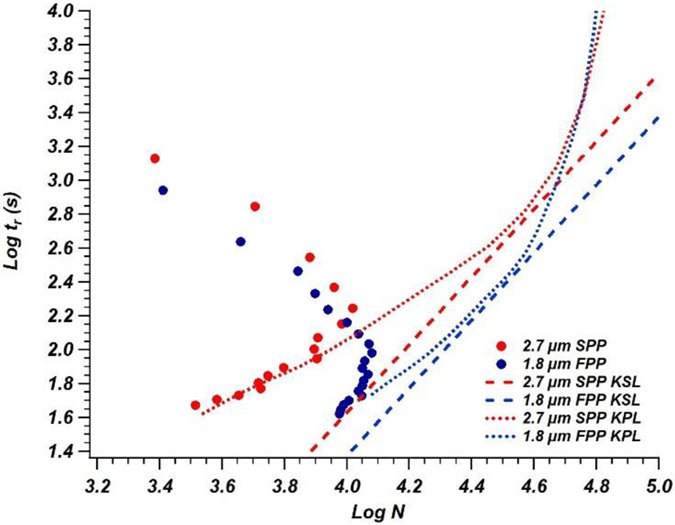

For measurements to be comparable to those made using the lower pressure columns, a maximum pressure of 570 bar was selected to be consistent with the operation requirement of 82.5% maximum pressure. The higher pressure columns contained 1.8 μm diameter fully porous particles and were only available in a 300 μm i.d. format. Results obtained from comparison between 50 mm and 150 mm column lengths (Figure 4) were similar to those obtained from comparison between the lower pressure column lengths (Figure 2). The intersection points in the plot of Columns 6 and 7 indicate a chromatographic efficiency slightly under 40,000 plates with a hold-up time of 54 s for a 19.4 cm long column at 6 μL/min. Under these conditions, an analysis time for a compound with would be 5.9 min, thus reducing potential issues resulting from limited LC pump volume.

Figure 4.

Kinetic plot comparison of 50 mm x 0.3 mm i.d. (red points) and 150 mm x 0.3 mm i.d. (blue points) columns packed with 1.8 μm fully porous particles. KPL curves for each column are fit with matching color dotted lines and the KSL is represented with a green dashed line.

Finally, kinetic plot comparisons were made for columns with identical dimensions but packed with particles of various sizes, morphologies, and maximum pressure limits. Figure 5 shows KPL and KSL plots for Columns 5 and 6. Again, an improvement in performance for smaller particle sizes at similar pressures was observed. There is a significant downward shift between the two KSL plots. As previously mentioned, the KSL represents the theoretical fastest time to generate a given plate count for a given . By increasing the maximum pressure, an analysis can be performed at faster speeds. Because of this, an increase in maximum pressure results in a downward shift in the KSL plot, as seen in Figure 5. While superficially porous particles typically outperform fully porous particles with regard to separation efficiency and throughput when similar column dimensions and operating pressures [31] are compared, the higher pressure limits of fully porous packed columns available in these dimensions allow for faster separations and higher analytical throughput. This can be seen in Figure 5, where the intersection points of the KPL and the KSL for both fully and superficially porous particles generate nearly 40,000 theoretical plates; however, the higher pressure limit of the fully porous particles allows these plates to be generated in 5.9 min, while the lower pressure limit of the superficially porous particles requires a separation time of 10.3 min.

Figure 5.

Kinetic plot comparison of 50 mm x 0.3 mm i.d. columns packed with 2.7 μm superficially porous particles (330 bar operating limit, red points) and 1.8 μm fully porous particles (570 bar operating limit, blue points). KPL curves for each column are fit with matching color dotted lines and the KSL for each operating limit is represented with matching color dashed lines.

A limitation of a portable LC system with small volume syringe pumps is the small total mobile phase volume available in a single syringe fill cycle. As was briefly mentioned before, the system used in this study utilizes a pair of syringe pumps to generate flow, each with a maximum volume of 135 μL. In this study, a maximum flow rate of 20 μL/min was used. At this flow rate, if the system was operated under isocratic conditions with 50% of the total flow generated by each pump (i.e., 10 μL/min each), a maximum of 13.5 min of operation would result. Of this 13.5 min, a portion of the time must be utilized for pressurization and equilibration before an injection can take place. Depending on column volume, this process can take anywhere from 2-3 min, reducing the available analysis time to ~10 min. Given a 7 s hold-up time demonstrated for Column 6, a theoretical maximum of 84 would be possible, which would provide ample separation space for most standard applications.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a new miniaturized LED-based UV-absorption detector was described that can be integrated into a capillary column cartridge for use in a compact, portable LC system. The increased volume of the detector flow cell compared to a previous on-column version of the detector prompted an increase in the typical column diameter used in the system from 0.150 mm i.d. to the 0.2 – 0.3 mm i.d. range. Kinetic plot comparisons of various commercially available columns with i.d. values in this range provided insight into the achievable chromatographic performance across the mobile phase flow rate operating range, which varies based on column length, particle diameter, column diameter, and pressure limit. Theoretical performance limits demonstrated optimal efficiency at faster run times with smaller particles, which is most applicable to systems for which long runs at high flow rates are limited to the combined volume of the miniaturized syringe pumps that enable portability. In the future, the optimal balance between total mobile phase volume available for a single run and total analysis time under both isocratic and gradient conditions will be explored.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Investigation of columns coupled to compact absorbance detector module

Kinetic plot characterization of columns in 200 – 300 μm diameter range

Effects of column length, particle type, and pressure limits are examined

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by the National Institutes of Health through award R44 GM137649. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Matthew Morse and Greg Ward (Axcend Corporation) are acknowledged for technical assistance. SWF was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-2043212).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

EPG, PAP, SC, WRW, and MLL are associated with Axcend Corporation, a company that develops and commercializes compact LC technology that was used to obtain data for this study.

CREDIT Statement

Samuel W. Foster: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Elisabeth P. Gates: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization. Paul A. Peaden: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization. Serguei Calugaru: Investigation. W. Raymond West: Project administration, Funding acquisition. Milton L. Lee: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition. James P. Grinias: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Armenta S, Garrigues S, de la Guardia M, Green Analytical Chemistry, TrAC - Trends Anal. Chem 27 (2008) 497–511. 10.1016/j.trac.2008.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tobiszewski M, Mechlinska A, Namie J, Green analytical chemistry—theory and practice, Chem. Soc. Rev 39 (2010) 2869–2878. 10.1039/b926439f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gałuszka A, Migaszewski Z, Namieśnik J, The 12 principles of green analytical chemistry and the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic of green analytical practices, TrAC - Trends Anal. Chem 50 (2013) 78–84. 10.1016/j.trac.2013.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Armenta S, Garrigues S, Esteve-Turrillas FA, de la Guardia M, Green extraction techniques in green analytical chemistry, TrAC - Trends Anal. Chem 116 (2019) 248–253. 10.1016/j.trac.2019.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yabré M, Ferey L, Somé I, Gaudin K, Greening Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography Methods Using Alternative Solvents for Pharmaceutical Analysis, Molecules. 23 (2018) 1065. 10.3390/molecules23051065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shaaban H, Górecki T, Current trends in green liquid chromatography for the analysis of pharmaceutically active compounds in the environmental water compartments, Talanta. 132 (2015) 739–752. 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Majors RE, Anatomy of an LC column: From the beginning to modern day, LCGC North Am. 24 (2006) 742–753. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fekete S, Murisier A, Losacco GL, Lawhorn J, Godinho JM, Ritchie H, Boyes BE, Guillarme D, Using 1.5 mm internal diameter columns for optimal compatibility with current liquid chromatographic systems, J. Chromatogr. A 1650 (2021) 462258. 10.1016/j.chroma.2021.462258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Libert BP, Godinho JM, Foster SW, Grinias JP, Boyes BE, Implementing 1.5 mm internal diameter columns into analytical workflows, J. Chromatogr. A 1676 (2022). 10.1016/j.chroma.2022.463207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Coates LJ, Lam SC, Gooley AA, Haddad PR, Paull B, Wirth HJ, Modular, cost-effective, and portable capillary gradient liquid chromatography system for on-site analysis, J. Chromatogr. A 1626 (2020) 461374. 10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Foster SW, Xie X, Hellmig JM, Moura-Letts G, West WR, Lee ML, Grinias JP, Online monitoring of small volume reactions using compact liquid chromatography instrumentation, Sep. Sci. Plus 5 (2022) 213–219. 10.1002/sscp.202200012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chatzimichail S, Casey D, Salehi-Reyhani A, Zero electrical power pump for portable high-performance liquid chromatography, Analyst. 144 (2019) 6207–6213. 10.1039/c9an01302d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Foster SW, Xie X, Pham M, Peaden PA, Patil LM, Tolley LT, Farnsworth PB, Tolley HD, Lee ML, Grinias JP, Portable capillary liquid chromatography for pharmaceutical and illicit drug analysis, J. Sep. Sci 43 (2020) 1623–1627. 10.1002/jssc.201901276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cortés-Bautista S, Navarro-Utiel R, Ballester-Caudet A, Campíns-Falcó P, Towards in field miniaturized liquid chromatography: Biocides in wastewater as a proof of concept, J. Chromatogr. A 1673 (2022) 463119. 10.1016/j.chroma.2022.463119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].La Tella R, Rigano F, Guarnaccia P, Dugo P, Mondello L, Non-psychoactive cannabinoids identification by linear retention index approach applied to a hand-portable capillary liquid chromatography platform, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 414 (2022) 6341–6353. 10.1007/s00216-021-03871-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chatzimichail S, Rahimi F, Saifuddin A, Surman AJ, Taylor-Robinson SD, Salehi-Reyhani A, Hand-portable HPLC with broadband spectral detection enables analysis of complex polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mixtures, Commun. Chem 4 (2021) 17. 10.1038/s42004-021-00457-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hemida M, Ghiasvand A, Gupta V, Coates LJ, Gooley AA, Wirth HJ, Haddad PR, Paull B, Small-Footprint, Field-Deployable LC/MS System for On-Site Analysis of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Soil, Anal. Chem 93 (2021) 12032–12040. 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c02193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hemida M, Haddad PR, Lam SC, Coates LJ, Riley F, Diaz A, Gooley AA, Wirth HJ, Guinness S, Sekulic S, Paull B, Small footprint liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry for pharmaceutical reaction monitoring and automated process analysis, J. Chromatogr. A 1656 (2021) 462545. 10.1016/j.chroma.2021.462545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jornet-Martínez N, Herráez-Hernández R, Campíns-Falcó P, Scopolamine analysis in beverages: Bicolorimetric device vs portable nano liquid chromatography, Talanta. 232 (2021) 122406. 10.1016/j.talanta.2021.122406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Li Y, Nesterenko PN, Stanley R, Paull B, Macka M, High sensitivity deep-UV LED-based z-cell photometric detector for capillary liquid chromatography, Anal. Chim. Acta 1032 (2018) 197–202. 10.1016/j.aca.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hemida M, Coates LJ, Lam SC, Gupta V, Macka M, Wirth H-J, Gooley AA, Haddad PR, Paull B, Miniature Multi-Wavelength Deep UV-LED-Based Absorption Detection System for Capillary LC., Anal. Chem 92 (2020) 13688–13693. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c03460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Xie X, Tolley LT, Truong TX, Tolley HD, Farnsworth PB, Lee ML, Dual-wavelength light-emitting diode-based ultraviolet absorption detector for nano-flow capillary liquid chromatography, J. Chromatogr. A 1523 (2017) 242–247. 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Desmet G, Clicq D, Gzil P, Geometry-independent plate height representation methods for the direct comparison of the kinetic performance of LC supports with a different size or morphology, Anal. Chem 77 (2005) 4058–4070. 10.1021/ac050160z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Desmet G, Cabooter D, Broeckhoven K, Graphical Data Representation Methods to Assess the Quality of LC Columns, Anal. Chem 87 (2015) 8593–8602. 10.1021/ac504473p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Thompson JD, Carr PW, High-Speed Liquid Chromatography by Simultaneous Optimization of Temperature and Eluent Composition, Anal. Chem 74 (2002) 4150–4159. 10.1021/ac0112622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Broeckhoven K, Stoll DR, But Why Doesn’t It Get Better? Kinetic Plots for Liquid Chromatography, Part I: Basic Concepts, LC-GC North Am. 40 (2022) 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Li J, Carr PW, Accuracy of Empirical Correlations for Estimating Diffusion Coefficients in Aqueous Organic Mixtures, Anal. Chem 69 (1997) 2530–2536. 10.1021/ac961005a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Broeckhoven K, Desmet G, Advances and Innovations in Liquid Chromatography Stationary Phase Supports, Anal. Chem 93 (2021) 257–272. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Broeckhoven K, Cabooter D, Desmet G, Kinetic performance comparison of fully and superficially porous particles with sizes ranging between 2.7 μm and 5 μm: Intrinsic evaluation and application to a pharmaceutical test compound, J. Pharm. Anal 3 (2013) 313–323. 10.1016/j.jpha.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Broeckhoven K, Desmet G, Methods to determine the kinetic performance limit of contemporary chromatographic techniques, J. Sep. Sci 44 (2021) 323–339. 10.1002/jssc.202000779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Guiochon G, Gritti F, Shell particles, trials, tribulations and triumphs, J. Chromatogr. A 1218 (2011) 1915–1938. 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.