Abstract

Mercury methylation frequently occurs at the active oxic/anoxic boundary between the sediment bed and water column of lakes and reservoirs. Previous studies suggest that the predominant mercury methylation zone moves to the water column during periods of stratification and that high potential methylation rates () in sediment require oxygenated overlying water. However, simultaneous measurements of methylmercury (MeHg) production in both the sediment and water column remain limited. Understanding the relative importance of sediment versus water column methylation and the impact of seasonal stratification on these processes has important implications for managing MeHg production. This study measured and potential demethylation rates () using stable isotope tracers of unfiltered inorganic mercury and MeHg in sediments and water of the littoral and profundal zones of a shallow branch of the Nacimiento Reservoir in California’s central coastal range. Field sampling was conducted once during winter (well-mixed/oxygenated conditions) and once during late summer (thermally stratified/anoxic conditions). The results showed very high ambient MeHg concentrations in hypolimnetic waters (up to 7.5 ng L−1; 79% MeHg/total Hg). During late summer, littoral sediments had higher (0.024 day−1) compared to profundal sediments (0.013 day−1). Anoxic water column were of similar magnitude to in the sediment (0.03 day−1). Following turnover, profundal sediment did not change significantly, but water column became insignificant. Summer and winter sediment were higher in profundal (2.35, 3.54 day−1, respectively) compared to the littoral sediments (0.52, 2.56 day−1, respectively). When modelled, in the water column could account for approximately 40% of the hypolimnetic MeHg. Our modelling results show that the remaining MeHg in the hypolimnion could originate from the profundal sediment. While further study is needed, these results suggest that addressing methylation in the water column and profundal sediment are of equal importance to any remediation strategy.

Keywords: Mercury, Methylmercury, Methylation, Surface water, Sediment

1. Introduction

Regardless of the source, anthropogenic releases of mercury (Hg) have been dominated by inorganic forms (non-methylation); however, methylmercury (MeHg) is the predominate form of mercury that bioaccumulates in individual organisms and biomagnifies through aquatic food webs (Driscoll et al., 2013; Ullrich et al., 2001). Reducing levels of environmental MeHg requires knowledge on the sources and variables that control MeHg production. In aquatic systems, microbial processes are the major drivers of Hg methylation (Benoit et al., 2003; Eckley and Hintelmann, 2006; Korthals and Winfrey, 1987; Ullrich et al., 2001). Under reducing conditions, divalent Hg (Hg2+) can be converted to MeHg by sulfate-reducing, iron-reducing, methanogenic bacteria and archaea (Bravo et al., 2018; Gilmour et al., 2013; Gilmour et al., 1998; Kerin et al., 2006).

In lakes and reservoirs, a major source of MeHg has been internal production (Watras et al., 2005). Numerous studies, focused on water column methylation, have noted that MeHg concentrations are the highest in the anoxic hypolimna of seasonally stratified waterbodies, but have not simultaneously measured MeHg production in sediment (McCord et al., 2016; Sellers et al., 2001; Watras et al., 1995). Sources of MeHg that contribute to the hypolimnetic pool include production in the sediment and diffusion into the overlying water and/or production within the water column (Eckley and Hintelmann, 2006; Skyllberg et al., 2003; Tsui et al., 2008; Watras et al., 1995). Maximum potential methylation rates () in both water and sediment typically, but not exclusively, occur along the transition between oxic and anoxic conditions (redox boundary) where terminal electron accepters such as sulfur can be cycled between oxidized and reduced forms (Watras et al., 1995). In a well oxygenated systems, this redox boundary occurs in the top few cm of sediments or the terrestrial-aquatic boundary (McClain et al., 2003). The oxic/anoxic boundary has been shown to move seasonally between the sediment bed and water column of thermally stratified lacustrine systems (Watras et al., 1995).

Within sediments, there may be differences between and maximum potential demethylation rates () in near-shore environments (littoral zone) versus deeper sections of the lake/reservoir (profundal sediments). The relative importance of these different zones may be impacted by seasonal variations in water-column redox conditions, as well as by water levels (wet dry cycles that can result in sediment exposure to air followed by inundation). Seasonal sediment inundation remains a particularly important feature of reservoir systems that have been used as a municipal/agricultural water source or managed for flood-control (Eckley et al., 2017), but have also occurred in natural lakes impacted by climatic variability (Sorensen et al., 2005; Watras et al., 2018).

Adding oxygen to the hypolimnia of lakes and reservoirs can decrease MeHg production by directly preventing water column methylation (Dent et al., 2014; Duvil et al., 2018; McCord et al., 2016). However, The effectiveness of this technique is dependent on the water column being the dominant source of MeHg with minimal sediment or watershed inputs (Stewart et al., 2008). Hypolimnion oxygen has been shown to decrease MeHg concentration in bottom waters; however, the impact on MeHg in biota has been less definitive (Beutel et al., 2014; McCord et al., 2016).

Another important control on MeHg concentrations in lakes and reservoirs is demethylation. Research has shown that demethylation can occur following both biotic and abiotic pathways (Li and Cai, 2013; Oremland et al., 1991; Poste et al., 2015; Tjerngren et al., 2011). Abiotic demethylation, through photodegradation, may be the dominant pathway in surface waters (Hammerschmidt and Fitzgerald, 2006; Li et al., 2010; Sellers et al., 1996) accounting for as much as 80% of MeHg degradation (Hammerschmidt and Fitzgerald, 2006). While efficient, photo-demethylation is limited by light penetration. Below the photic zones and within sediments, biotic processes are the primary mechanism responsible for demethylation (Hsu-Kim et al., 2013). This limited light penetration is relevant in lakes and reservoirs which stratify as the photic zone can be relatively shallow, causing a buildup of MeHg in the hypolimnion.

Previous studies on have focused on production in sediment (Cesario et al., 2017; Hintelmann et al., 2000; Oremland et al., 1991) or the water column (Eckley and Hintelmann, 2006; Eckley et al., 2005; Hammerschmidt et al., 2006) resulting in uncertainty about the relative importance of these two processes contributing to the buildup of MeHg in an anoxic hypolimnion and the overall budget of MeHg within an aquatic system. Information about the specific zones of MeHg production has been critical to designing effective remediation strategies to reduce MeHg accumulation in aquatic biota. Remediation strategies targeting sediment MeHg production may focus on the application of sediment amendments and/or reservoir processes affecting water-level fluctuations; whereas, strategies aimed at water column production may focus on hypolimnion aeration and/or selective water withdrawals, among other options. The primary objective of our study was to determine the relative importance of MeHg production and degradation in the water-column and littoral and profundal sediments of a reservoir that experiences seasonal stratification. The study hypothesis was that MeHg concentrations observed in the water of the Las Tablas branch of the Nacimiento Reservoir were derived primarily from production within the water column with minor contributions from sediment sources. In addition, we had a sub-objective of better understanding experimental procedures involved with measuring (see supplemental information).

2. Methods

2.1. Site description

Nacimiento Reservoir (35.7483, −120.931 WGS-84) is located in the Santa Lucia mountains in the central coastal area of California (Fig. 1). This reservoir was created by a 64 m high dam that was constructed in 1957 for multiple purposes including groundwater recharge for agricultural areas, flood control, domestic water supply and hydropower. The reservoir has an annual maximum depth of 73 m depending on precipitation levels and reservoir water releases. Our specific study locations within the reservoir focused on areas within and near the Las Tablas branch. Based on satellite images and maps it was estimated that the las Tablas branch of the reservoir contained approximately 9.51 × 106 m3 of water and 1.63 km2 of sediment. The seasonal change in water level within the reservoir results in near-shore sediments being seasonally exposed to the air during low-pool conditions and then inundated during high-pool conditions.

Fig. 1.

Area map showing sampling locations within the Nacimiento Reservoir (35.7483, −120.931 WGS-84) in the Santa Lucia mountains in the central coastal area of California, U.S.A. Purple site markers are Profundal sample sites and green markers are littoral sample sites. Solid color markers are in the Las Tablas branch while markers with an inset white circle are in the Central basin of Nacimiento Reservoir. Inset shows the location of the Klau and Buena Vista former mine sites within the watershed of the Las Tablas branch of the reservoir in relation to Morro Bay (Pacific Ocean).

The Las Tablas branch of Nacimiento Reservoir was of particular interest because it receives the inflowing water from Las Tablas Creek, which drains two abandoned Hg mines (Klau and Buena Vista) located approximately 10 km upstream. The mines and on-site ore processing operated from 1868 until 1970 and produced over 4,000 tons of Hg. Since 2006, the U.S.A. EPA has conducted several removal and remediation activities at the mine site to reduce the amount of Hg mobilized in runoff. However, legacy impacts of the mining operations continue to result in significantly elevated MeHg concentrations in fish (>1 μg g−1) and public health fish consumption advisories (California Department of Public Health, 2010; IRIS, 2001).

2.2. Field sampling

Sediment and water samples were collected from two general locations within the reservoir—within the Las Tablas branch and from the central basin near where the Las Tablas branch connects to the larger reservoir (Fig. 1). In each of these general areas, samples were collected from the near-shore littoral zone of the reservoir (water-level ~1 m deep) and from the deeper mid-channel zone of the reservoir (water level between 9 and 15 m deep).

Sediment from each of the sample locations was collected as four replicates from each of the four sample locations (n = 16 per sampling event). Each location was sampled during the summer (September 2015), and winter (January 2016) resulting in a total of 32 sediment samples. Sediment samples were collected using a large-bore (9.5 cm diameter) sediment corer (Aquatic Research Instruments, U.S.A.) with polycarbonate core tubes.

Sediment samples analyzed for acid-volatile sulfide (AVS) and loss-on-ignition (to estimate organic matter content) were collected into 125 mL glass jars from subsamples of the top 4 cm of sediment from each core and were immediately frozen until analysis.

Water samples were collected from the surface (<1m deep) at each of the four sample locations using a peristaltic pump. The sample lines were acid-cleaned with 10% HCl and rinsed with ultrapure water prior to use. At the two deeper mid-channel locations samples from three depths were collected from the hypolimnion during the summer period when the reservoir was stratified and from one depth during the winter when the reservoir was well mixed. Resulting in a total of 16 water samples for the methylation/demethylation assays. Reservoir water column temperature, pH, oxidation/reduction potential (ORP), conductivity, and dissolved oxygen (DO) were measured at eight depths using a multi-probe data sonde (Horiba S-50 Multiparameter Data Sonde, Kyoto Japan) that was calibrated prior to each sampling event.

Whole water samples were collected for total and methylmercury (Teflon bottle, preserved with ultra-pure HCl) and filtered water samples were collected for anions (polyethylene bottle; preserved at 4 °C), dissolved organic carbon (DOC; amber glass bottle, preserved with sulfuric acid) and sulfide (amber glass bottle preserved with zinc acetate) from each location and depth. All filtered samples were filtered in the field using an in-line 0.45 μm capsule filter. Ultra-clean methods were followed during water sample collection and processing of samples for mercury analysis (EPA, 1996). Field sampling techniques used in this study were similar to those previously reported (Eckley et al., 2017; Eckley et al., 2021).

2.3. Mercury isotope assays

Sediment samples for the stable isotope methylation/demethylation assays were sub-sampled from the larger core tubes using small-diameter (5 cm) core tubes with a minimum of 10 cm of overlying water and capped. The general procedure for the methylation/demethylation assays followed similar techniques as described elsewhere (Mitchell and Gilmour, 2008). The primary isotope spike solution (obtained from the USGS Mercury Research Laboratory at the Wisconsin Water Science Center) consisted of enriched 198Hg and Me204Hg created 1 h prior to the injections by mixing filtered reservoir water with a concentrated spike stock solution for a final 198Hg concentration of 330 μg L−1 and 204MeHg concentration of 10 μg L−1. During the summer sampling event, two additional isotope spike solutions were created using deionized (DI) water and high-DOC wetland water to identify the influence of dissolved organic carbon source and concentration on mercury .

The top 4 cm of the sediment cores were spiked with 0.7 mL of 198Hg and Me204Hg isotope solution which were applied using a syringe through small holes in the core tube that were drilled 1 cm apart and sealed with silicone. Each 1 cm section of the core received 0.23 μg of 198Hg isotope and 7.3 ng of Me204Hg resulting in an initial 198Hg concentration of 8.6 ± 0.9 ng g−1 (n = 12) and an initial Me204Hg concentration of 1.2 ± 0.2 ng g−1 (n = 12). The sediment cores were incubated in a cooler for 12 h prior to experiment termination by extracting the sediment into 120 mL glass jars and rapidly freezing using dry ice. The entire duration of the incubation experiment was performed within 24 h of the initial sample collection from the reservoir. Minimum detection limits for were calculated based on the instrument precision of replicate measurements passed through the rate calculation (; ).

Water samples for the stable isotope methylation/demethylation assays were collected into 100 mL amber glass serum bottles. To preserve in situ redox conditions, the bottles were overfilled with twice their volume and capped by displacing air and water through a needle inserted into the rubber stopper. The general procedure for the methylation/demethylation assays followed similar techniques as described elsewhere (Eckley and Hintelmann, 2006). The primary isotope spike solution consisted of enriched 198Hg and 204MeHg and was created 1 h prior to the injections by mixing filtered reservoir water with a concentrated spike stock solution for a final 198Hg concentration of 84 ng L−1 and 204MeHg concentration of 45 ng L−1. During the summer sampling event, two additional isotope spike solutions were created using the same procedures described above. Additional details from this experiment can be found in the SI.

Each serum bottle was spiked with 1 mL of the 198Hg and 204MeHg isotope solution which was applied using a syringe that was injected through the rubber stopper with displacement water removed through a separate needle inserted into the stopper. This resulted in a final concentration in each bottle of 1.2 ng L−1 198Hg and 0.25 ng L−1 204MeHg. The water samples were incubated in a cooler for 20 h prior to experiment termination by addition of HCl. The entire duration of the incubation experiment was performed within 30-h of the initial sample collection from the reservoir. Minimum detection limits for were calculated based on the instrument precision of replicate measurements passed through the rate calculation (; ).

2.4. Laboratory analysis

Sediment and whole water total mercury (THg) and MeHg, Hg stable isotopes (whole water and sediment; Reference material: THg = IAEA SL-1, MeHg = SQC 1238 (DeWild et al., 2004; Olund et al., 2004);), and Loss On Ignition (LOI) were analyzed at the USGS Mercury Research Laboratory (DeWild et al., 2002; DeWild et al., 2004; Olund et al., 2004). Water samples for MeHg isotopes were distilled, pH adjusted to 4.9 using acetate, ethylated using sodium tetraethyl borate, purged with nitrogen gas for preconcentration on carbotraps, thermally desorbed and separated using a gas chromatographic column, reduced using a pyrolytic column, and detected using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP/MS, Limit of Detection [LoD] = 0.01 ng L−1). Water samples for THg isotopes were oxidized using bromine chloride and reduced with stannous chloride and purged with nitrogen gas, captured on a gold trap, thermally desorbed and detected with an ICP/MS (LoD = 0.2 ng L−1). A summary of isotope daily detection limits can be found in Table S1. Sediment samples for THg and MeHg analysis followed a similar technique as the waters but were first digested using aqua regia for THg (LoD = 0.5 ng g−1) and potassium bromide, copper sulfate, and dichloromethane for MeHg (LoD = 0.01 ng g−1). Additional quality control information for mercury analysis in water samples can be found in Table S2.

Sediment sample results have been reported on a dry weight basis. Sediment samples were analyzed for AVS at ALS-Columbia (Kelso, WA) following Allen et al. (1991, LoD = 0.1 mg kg−1). Filtered water samples were analyzed for sulfide following Standard Method 4500-S2- D (Methylene Blue Method) and organic carbon following EPA Method 415.3 at ALS-Columbia (Kelso, WA). Sulfate was analyzed following EPA Method 300.0 at Alpha Analytical (Sparks, NV). All sediment digestions included a blank, blank spike, reference, and sample spike for every 10 digestions. All analytical procedures included the same quality control procedures (blank, blank spike reference, and sample spike every 10 samples). If there was a difference of more than 10% between quality control samples the preceding 10 samples were reanalyzed. Additional quality control information for mercury analysis in sediment samples can be found in Table S3. Laboratory analysis for this study was similar to previously published research (Eckley et al., 2017).

The mean ± standard error of whole water field blanks (n = 3) for unfiltered THg were 0.36 ± 0.16 ng L−1 and for unfiltered MeHg were <0.02 ng L−1. Field blanks for all other water measurements (sulfide, sulfide, and DOC) were all less than their method reporting limits. The relative percent difference (RPD) of the field replicate water samples for whole surface water THg was 19 ± 3% (n = 24) and MeHg was 29 ± 4% (n = 23); for filtered water (n = 3) sulfate was 4.1 ± 0.6%, DOC was 2.5 ± 0.1%, and sulfide was 0.6 ± 0.6%. The relative percent difference (RPD) of the field replicate sediment samples (n = 24) for THg was 30 ± 9%, for MeHg was 30 ± 8%, LOI was 14 ± 3% and AVS was 28 ± 6%.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Shapiro-Wilks, Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn’s test, and linear regression tests were conducted using Rv3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2019). The Shapiro-Wilks test was used to check our data for normality, and the Kruskal-Wallis was used as a non-parametic ANOVA test. These tests were used to look for differences in the and found during the incubation experiment. The Kruskal-Wallis test () was used to look for seasonal and location differences in 1) concentrations of THg, MeHg in the water column and sediment and 2) and in the water column and sediment. The Kruskal-Wallis test was also used to determine interaction between season and location. Where there was a significant interaction (), a Dunn’s test was used to compare the groups ().

2.6. Modelling

Modelling methylation/demethylation in both sediments and the water column used the equation developed by Hintelmann et al. (2000):

| (1) |

where was the amount of MeHg (kg) in the top 4 cm of sediment at a given time interval, was the potential methylation rate constant , was the potential demethylation rate constant , was the initial THg (kg) in the top 4 cm of sediment, and was the timestep. This equation calculates the amount of MeHg expected in the sediment, or water column based on an initial condition and assumed first-order kinetics. The sediment and water volumes were estimated using the depth profiles to separate the epilimnion and the hypolimnion. The oxycline and underlying sediment were included in the epilimnion/littoral sediment for modelling purposes as our study did not conduct separate experiments for this transitional zone. Sediment mass was estimated from a 2013 bathymetry study (Fig. S1 to find surface area) and our depth profiles such that littoral sediment had overlying oxic water and profundal sediment had overlying anoxic water.

A second equation was needed to convert the sediment MeHg concentration from weight/weight to weight/volume:

| (2) |

where was the w/v concentration of MeHg, 2.65 as the sediment bulk density and (1-porosity) was approximately the % dry for the collected sediment.

A third equation was used to calculate the potential MeHg load from sediments to the water column:

| (3) |

where MeHg Load was calculated in mg m−2 d−1, Dispersion as the rate at which sediment re-suspends in the water column (m2 s−1) and was estimated based on modelling work that has been conducted in other western U.S.A. reservoirs (Eckley et al., 2021). Dispersion Length was the distance (m) through sediment the MeHg traveled (m). This result was normalized by the sediment surface area, estimated from the 2013 bathymetry study (Fig. S1), for comparison with observed concentrations in the water column. Model error was estimated by adding (or subtracting) the standard error from our observed THg, and subtracting (or adding) the standard error from to generate a maximum (and minimum) estimate of MeHg loading. A Monte Carlo analysis of the Dispersion and Dispersion Length was conducted to determine model sensitivity to these parameters. Random normal distributions for Dispersion (m = 0.4 m2 s−1 and SD = 0.4 m2 s−1, n = 100,000) and Dispersion Length (m = 4 cm and SD = 0.4 cm, n = 100,000) were generated and used to calculate a mean and standard error for MeHg Load (Table S4). Numerical models and calculations were constructed and performed using Rv3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2019).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. 1Reservoir seasonal limnology

Nacimiento Reservoir undergoes seasonal thermal stratification with anoxic conditions developing in the hypolimnion in the summer followed by well-mixed, oxygenated conditions in the winter (Fig. 2A). At all our sample sites the water column was anoxic ~7.5 m below the water surface during the summer sampling period. A similar pattern can be seen with ORP and Temperature (Fig. 2B and C, respectively) where the summer profiles were consistent above 7.5 m depth below which temperature declined to a minimum of 16.2 °C at the bottom (12.5 m). The winter profiles of DO, temperature and ORP remained almost uniform from surface to sediment indicating Las Tablas branch stratifies over the course of the summer with the potential for elevated MeHg concentrations in the hypolimnion.

Fig. 2.

Depth profiles measured at Nacimiento Reservoir for Dissolved Oxygen (A), Oxidation-Reduction Potential (B) and Temperature (C). Example summer profile has green circles (Sept. 2015) and winter has purple triangles (Jan. 2016).

There were also significant changes in the reservoir water depth throughout the year. For example, at our study locations the water level varied by over 7 m between sampling events (9 m deep in the spring; 16 m deep in the winter). This seasonal variation in water levels within our year of study was relatively small compared to inter-annual changes in water levels that can occur during periods of prolonged drought or precipitation (55–64 m; Monterey County Water Resources Agency (2022)). These seasonal and interannual changes in water-levels can result in near-shore sediments being exposed to the atmosphere for months (or years) followed by re-wetting when water levels rise. Several previous studies have shown that seasonal wetting and drying of sediments can result in increased MeHg production due to enhanced sulfur cycling and organic matter degradation (Eckley et al., 2017; Sorensen et al., 2005; Willacker et al., 2016).

3.2. Ambient water column and sediment THg and MeHg

Water column Hg concentrations were higher closer to the sediment bed in both seasons sampled (Fig. 3A). This would be consistent with hypolimnetic enrichment of Hg due to 1) additional loading from sediment dispersion and, 2) poor light penetration for abiotic removal. Water column MeHg concentrations were relatively low throughout the water column during well mixed winter conditions (0.2–0.4 ng L−1), and higher concentrations closer to the sediment surface during stratified summer conditions (5.1–7.1 ng L−1), reaching greater than 50% of THg concentrations within 2 m of the sediment-water boundary (Fig. 3). In the summer, water-column THg concentrations showed a significant negative relationship with sulfate (m = −0.7 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.901, p < 0.001; Fig. S2A); and a significant positive relationship with sulfide (m = 14.1 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.871, p < 0.001; Fig. S2C). These results were consistent with previous studies showing a strong affinity of Hg for sulfide, which has the potential to preferentially bind Hg from settling metal oxides and/or other seston (Dent et al., 2014; Morel et al., 1998). During the summer MeHg also showed a positive linear relationship with sulfide (m = 11.5 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.938, p < 0.001; Fig. S2D), as well as THg (m = 0.761, Adj-R2 = 0.913, p < 0.001), and a negative relationship with sulfate (m = −0.56 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.923, p < 0.001; Fig. S2C). These results were similar to those observed in several other studies and were consistent with the involvement of sulfate-reducing bacteria in the methylation of Hg (Acha et al., 2012; Compeau and Bartha, 1985; Ullrich et al., 2001). In winter, THg concentrations increased with sulfate concentrations (m = 3.36 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.800, p = 0.010; Fig. S2A), potentially indicating linked watershed inputs. Sulfide was below detection in the oxygenated water in the winter and therefore did not show any trends with THg or MeHg (Figs. S2C and S2D, respectively).

Fig. 3.

One depth profile obtained for A) MeHg and B) THg of the Las Tablas Branch of the Nacimiento Reservoir. The Y-axis is displayed as distance above sediment due to the potential importance of sediments as a source of MeHg.

Sediment Hg and MeHg concentrations also varied by location and season within Nacimiento Reservoir. The profundal sediments had the highest THg and MeHg concentrations (Fig. 4A and B) with THg being significantly higher (Kruskal-Wallis, χ2 = 13.6, p < 0.001, n = 32) in the profundal sediment (637.1 ng g−1) than the littoral sediment (181.4 ng g−1). The sediment THg concentrations also varied between the seasonal measurements, but reflect spatial heterogeneity in THg concentrations and sampling locations, rather than seasonal changes (Fig. 4A). Total Hg in the sediments showed a significant positive regression with LOI (m = 94.9 ng g−1, Adj-R2 = 0.489, p < 0.001). These results suggest that the sediment Hg may be bound to organic matter but may also reflect similar depositional patterns of organic matter and THg in the reservoir. While many waterbodies have shown a strong relationship between THg and organic matter (Schartup et al., 2013; Scudder et al., 2009); areas receiving significant inputs from historical mining sources, often contain recalcitrant forms of mercury (cinnabar/metacinnabar) that do not interact strongly with organic matter while other base cations such as calcium are present (Biester et al., 2000; Covelli et al., 2001; Ravichandran et al., 1998).

Fig. 4.

Ambient sediment concentrations of A) THg, B) MeHg, and C) %MeHg (MeHg THg−1). Littoral values are on the left; profundal on the right. Summer observations (Sept. 2015) are green circles on the left of each pair; winter observations (Jan. 2016) are purple triangles on the right of each pair. Individual datapoints are displayed with the box plot.

MeHg concentrations were also statistically significantly higher in profundal sediment (mean = 0.980 ng g−1; Kruskal-Wallis, χ2 = 11.3, p < 0.001, n = 32) than littoral sediment (mean = 0.607 ng g−1). Despite differences in sediment THg concentrations, MeHg concentrations were not significantly different seasonally, but were highest in winter profundal sediment (1.07 ng g−1; Fig. 4B). Due to the large amount of THg present, all sediments had mean percent MeHg of THg <1.1% (Fig. 4C). Percent MeHg was highest in the summer littoral sediment which could be related to water level fluctuations and fresh organic matter accelerating methylation. Methyl Hg in the sediment also had a significant linear relationship with profundal AVS (m = 0.04 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.346, n = 16, p = 0.009; Fig. S3A), LOI (profundal: m = 0.367 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.214, n = 16, p = 0.041; littoral: m = 0.51 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.419, n = 16, p = 0.004; note these slopes are not significantly different p = 0.524; Fig. S3B), and THg (m = 0.009 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.181, n = 32, p = 0.009; Fig. S3C). These relationships were consistent with the general understanding of methylation as a microbial process mediated by anerobic bacteria utilizing organic matter as an electron source and sulfide as the by-product of sulfate-reducing bacteria activity (Ullrich et al., 2001). Significant relationships between THg and MeHg have been observed in many studies, especially in areas predominantly impacted by atmospheric deposition (Hsu-Kim et al., 2018). However, this relationship does not always hold at point source contaminated sites, either because sources of inorganic Hg were so elevated that concentration was no longer limiting MeHg production and/or high concentrations of Hg were present in more recalcitrant forms and were not methylated at similar rates as occurs for lower concentrations of more bioavailable forms of Hg (Chiasson-Gould et al., 2014; Eckley et al., 2017). Our data suggests a significant source of bioavailable Hg within the Nacimiento Reservoir watershed similar to areas predominantly impacted by atmospheric deposition.

3.3. Water column microbial methylation and demethylation

There was no significant difference in water column when the Hg isotope spike was equilibrated with reservoir water or wetland water (see SI for details). The Hg spike equilibrated with DI water resulted in significantly lower . This showed that reservoir surface water used as the spike equilibration solution in this study was appropriate for the water column experiments. Microbial in the water column varied with depth and season (Table S5). Methylation occurred throughout the water column during both winter and summer; however, summer methylation increased as DO decreased. Peak were observed in the summer, 2 m above the sediment (mean = 0.046 d−1, SE = 0.008 d−1, Fig. 5A). This was consistent with other research suggesting that methylation primarily occurs along the sulfur redox boundary within the water column (Watras et al., 1995).

Fig. 5.

Water column A) methylation, and B) demethylation rates. Green circles are summer (Sept. 2015) and blue triangles are winter (Jan. 2016) observations. Vertical error bars indicate the data has been pooled between depths. Horizontal error bars are the calculated standard error from the replicate rates. A summary of methylation and demethylation rates can also be found in Table S5.

Summer microbial also varied with depth and season (Table S5). Demethylation occurred throughout the water column during both winter and summer; however, summer demethylation potential decreased with decreasing DO resulting in maximum demethylation at the surface (mean = 0.455 d−1, SE = 0.178 d−1; Fig. 5B). While UV demethylation was not measured in this study, it likely had a significant impact on ambient mercury concentrations in the epilimnion/water overlying littoral sediment.

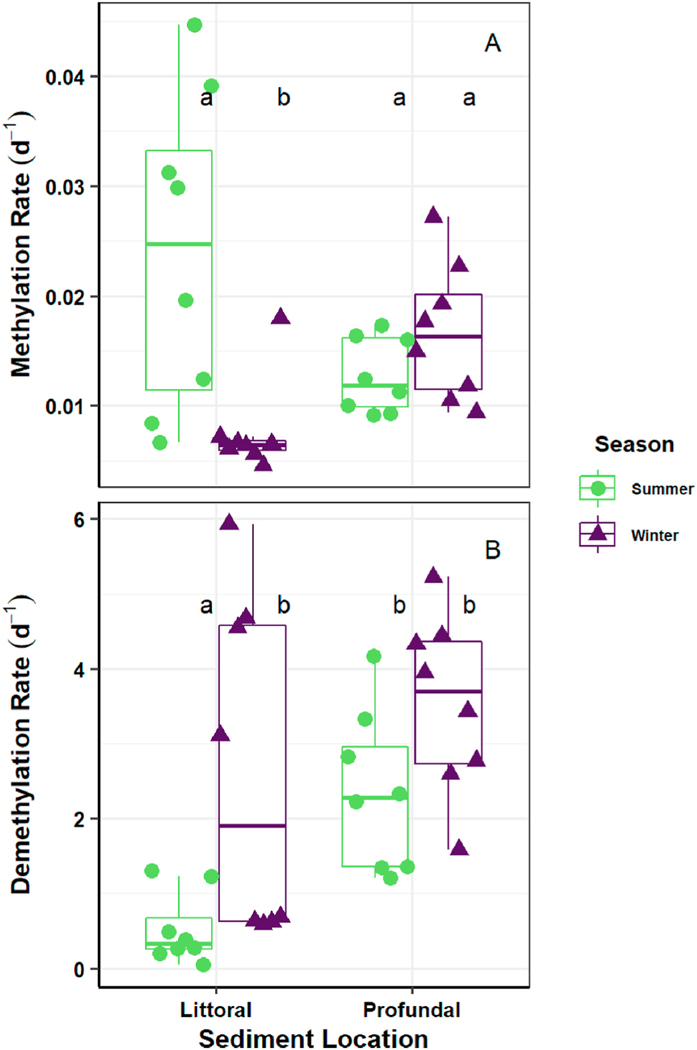

3.4. Sediment microbial methylation and demethylation

There was no significant difference in sediment when the Hg isotope spike was equilibrated with reservoir water or wetland water (see SI for details). The Hg spike equilibrated with DI water resulted in significantly lower . This showed that reservoir surface water used as the spike equilibration solution in this study was appropriate for the sediment experiments. Summer littoral sediments had the highest (mean = 0.024 d−1 SE = 0.005 d−1 n = 8; Fig. 6A), and the lowest (mean = 0.526 d−1 SE = 0.158 d−1, n = 8; Fig. 6B). This appeared to be influenced by seasonal, or water level fluctuations as were significantly lower in the winter littoral sediment (mean = 0.007 d−1, SE = 0.001 d−1, n = 8; Dunn’s test, p < 0.001). The winter littoral sediments also had significantly higher (mean = 2.60 d−1, SE = 0.739 d−1, n = 8) than the summer littoral sediment (mean = 0.526 d−1, SE = 0.158 d−1, n = 8; Dunn’s test, p = 0.004, n = 16). The profundal sediments did not exhibit the same seasonal variation in . This could be due to the absence of photo demethylation at this depth resulting in a larger MeHg pool for biotic demethylation throughout the year. Only one significant positive linear regression was found for which was with AVS in the winter littoral sediment (m = 179 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.540, n = 8, p = 0.023). was found to have a significant positive linear regression with AVS in the summer profundal sediment (m = 2.39 ng mg−1, Adj-R2 = 0.418, n = 8, p = 0.050).

Fig. 6.

Sediment A) methylation and B) demethylation rates. Summer boxplots are green (Sept. 2015; left of each pair); winter boxplots are purple (Jan. 2016; right of each pair). Individual datapoints used to construct each boxplot are displayed as circles (summer) and triangles (winter). A summary of methylation and demethylation rates in sediment can also be found in Table S6.

Our sediment methylation results were consistent with other freshwater research and suggest that the littoral sediments may be important sources of MeHg during summer months (Table S6). These sediment areas would be more highly influenced by reservoir management strategies resulting in increased methylation from more frequent wet/dry cycling (Driscoll et al., 2013; Eckley et al., 2017).

3.5. Relative importance of water-column and sediment MeHg production

Using the estimated volume of water in each layer, the observed concentrations of THg and MeHg, and the measured and , Eq. (1) was used to model the seasonal concentration of MeHg that could be expected in the summer epilimnion, hypolimnion, littoral sediment, and profundal sediment. Based on these efforts, the water column would be expected to contribute about 40% of the total observed mass of MeHg in the anoxic hypolimnion (Table 1). The epilimnion contained a far smaller mass of MeHg, however we found that the water column again could be expected to contribute about 50% of the total observed mass of MeHg in the epilimnion (Table 1). The observed mass of MeHg in the winter water column fell within the modelling error suggesting a limited influence of sediment processes during this period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Modelled and observed mercury mass contained in the different layers of the water column.

| Water Column | Time (d) | Modelled MeHg (g) | Modelled MeHg SE (g) | n | Observed MeHg (g) | Observed THg (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer Anoxic | 100 | 8.52 | 1.46 | 3 | 21.66 | 40.18 |

| Summer Oxic | 100 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 3 | 0.64 | 13.70 |

| Winter | 100 | 4.20 | 1.60 | 3 | 3.08 | 75.41 |

Given the low mass of observed MeHg in the epilimnion water (0.64 g, Table 1), the most likely source of the additional MeHg to the anoxic hypolimnion was loading from the profundal sediment. Over a 100-day period, there would need to be an additional MeHg load of 131 mg d−1 from the sediment to the water column. With Eq. (3) using a dispersion of 10−4 cm2 s−1 and a dispersion length of 4 cm, we estimate the MeHg contribution from sediment to the overlying water would range between 88.9 and 143.1 mg-MeHg d−1 or 101.1–162.6 ng-MeHg m−2 d−1. Based on a conservative dispersion coefficient, our estimated daily load coefficient could easily account for the load required for the water column to reach the observed concentration of MeHg in the anoxic hypolimnion (Fig. 7). This suggests that a significant portion of hypolimnetic MeHg in this area of Nacimiento Reservoir was derived from sediment methylation. The relative importance of sediment and water-column methylation may shift as the volume of hypolimnetic water increases in deeper sections of the reservoir outside of the Las Tables branch. Deeper sections of the reservoir with relatively larger anoxic hypolimna or a larger water:sediment ratio may have more MeHg being produced directly within the water column of that section.

Fig. 7.

Modelled rates into various mercury pools. Blue lines represent boundaries (air-epilimnion, epilimnion-hypolimnion). The curved arrow represents the modelled microbial methylation within the water column and large hashed arrows show the MeHg loading from sediment into the water column. Sample data suggests that there could be 3.1 g of MeHg present in the water column during the onset of stratification (spring) and 21.6 g of MeHg in hypolimnic water during the late-summer sampling. Littoral sediment also contributes a significant amount of MeHg to the water column (18.9 g), however this additional mercury would exceed the amount observed in the epilimnic water MeHg pool (0.6 g).

Without an estimate of abiotic demethylation this study could not provide an accurate mass balance of epilimnic MeHg. However, the potential load from littoral sediment was calculated following the same steps and conditions as with the anoxic hypolimnion. This modelling suggests the littoral sediment could contribute 83.4–337.0 mg-MeHg d−1, or 111–449 ng-MeHg m−2 d−1. This was at least an order of magnitude higher than the 2 mg-MeHg d−1 required over a 100-day period for the epilimnion to reach the observed pool of 0.64 g (Table 1). These results showed the littoral sediment was capable of contributing large amounts of MeHg to the epilimnion, as well as aquatic and terrestrial food webs.

Our estimates of sources of MeHg in Nacimiento Reservoir water focused on sediment fluxes and production within the water-column. While our estimates suggest these two sources may be the largest contributors of MeHg, there were still ~20 mg d−1 of hypolimnic MeHg for which our modelling could not account. This mass of MeHg could fall within measurement error, or have originated from other sources, such as thermocline methylation and inputs of MeHg from Las Tablas Creek. Las Tablas Creek drains from the abandoned Hg-mine sites upstream and flows through a small, impounded area, which may have provided additional sources of MeHg into the reservoir. Quantifying this source of MeHg has been planned as part of other Superfund Site assessment activities.

3.6. Summary and management implications

Our analysis shows that mercury methylation in lakebed sediment followed by dispersion into the hypolimnion and methylation occurring directly in the water-column can both be significant sources contributing to the mass of MeHg that accumulates in the hypolimnion in a stratified reservoir. The relative importance of these two sources of MeHg would be highly site-specific and dependent on the volume of water where methylation can occur relative to the sediment surface area as well as other biogeochemical factors. For example, in a deep reservoir with a larger ratio of anoxic water to sediment, MeHg production in the water-column may be relatively more important than the sediment. The opposite would be the case in a shallower reservoir with smaller zones of anoxic conditions and or bathymetry resulting in a smaller ratio of water volume to sediment surface area.

The fate of MeHg produced in littoral sediment was unable to be determined. With high and loading potential, it was possible for littoral sediment to be an important source of MeHg. A recent survey of lakes and reservoirs in New York State showed a strong positive relationship between shoreline length and percent MeHg (MeHg THg−1) in the water column (Millard et al., 2020). An abiotic demethylation would help provide context for the relative importance of littoralgenic MeHg.

Several previous studies have highlighted management options that can reduce MeHg production in reservoir sediments and/or water columns. Options targeting sediment processes include the application of biochar, activated carbon, or other amendments designed to reduce the availability of inorganic Hg for methylation (Eckley et al., 2020; Gomez-Eyles et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017). Options targeting water-column processes include oxygenation of the hypolimnion or addition of other constituents aimed at poising ORP above sulfate reduction. (Dent et al., 2014; Matthews et al., 2013; Seelos et al., 2020). Remediation strategies targeting either water column or sediment processes can be resource intensive. Therefore, an assessment of the relative importance of MeHg from the sediment versus the water column should be a critical step to developing effective remediation strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not, necessarily, reflect the official positions and policies of the U.S.A. EPA. Any use of trade, product, or firm names are for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S.A. Government. We would like to thank Carrie Austin (Cal EPA, SF Bay Water Board), Jim Sickles and Mike Gill (U.S.A. EPA Region-9), Mark Sorensen (Gilbane) and Joe Goulet and Kira Lynch (U.S.A. EPA Region-10) for their support and input on this project.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Author statement

Geoffrey Millard: Writing- Original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Chris S. Eckley: Writing- Original draft, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Todd P. Luxton: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Jenny Goetz: Investigation, Resources, Project administration, John McKernan: Funding acquisition, Investigation

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120485.

This paper has been recommended for acceptance by Philip N. Smith.

Data availability

Data is available online at science.gov

References

- Acha D, Hintelmann H, Pabon CA, 2012. Sulfate-reducing bacteria and mercury methylation in the water column of the lake 658 of the experimental lake area. Geomicrobiol. J 29, 667–674. [Google Scholar]

- Allen H, Gongmin F, Boothman W, Di Toro D, Mahony J, 1991. Draft Analytical Method for Determination of Acid-Volatile Sulfide and Selected Simultaneously Extractable Metals in Sediment. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Division of Health and Ecological Criteria, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit JM, Gilmour CC, Heyes A, Mason RP, Miller CL, 2003. Geochemical and Biological Controls over Methylmercury Production and Degradation in Aquatic Ecosystems. Biogeochemistry of Environmentally Important Trace Elements, pp. 262–297. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel M, Dent S, Reed B, Marshall P, Gebremariam S, Moore B, et al. , 2014. Effects of hypolimnetic oxygen addition on mercury bioaccumulation in Twin Lakes, Washington, USA. Sci. Total Environ 496, 688–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biester H, Gosar M, Covelli S, 2000. Mercury speciation in sediments affected by dumped mining residues in the drainage area of the Idrija mercury mine, Slovenia. Environ. Sci. Technol 34, 3330–3336. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AG, Peura S, Buck M, Ahmed O, Mateos-Rivera A, Herrero Ortega S, et al. , 2018. Methanogens and iron-reducing bacteria: the overlooked members of mercury-methylating microbial communities in boreal lakes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 84, 18 e01774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Public Health. Public Health Assessment Klau and Buena Vista Mines San Luis Obispo County, California EPA Facility ID CA1141190578 2010.

- Cesario R, Hintelmann H, Mendes R, Eckey K, Dimock B, Araujo B, et al. , 2017. Evaluation of mercury methylation and methylmercury demethylation rates in vegetated and non-vegetated saltmarsh sediments from two Portuguese estuaries. Environ. Pollut 226, 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson-Gould SA, Blais JM, Poulain AJ, 2014. Dissolved organic matter kinetically controls mercury bioavailability to bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol 48, 3153–3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compeau GC, Bartha R, 1985. Sulfate-reducing bacteria - principal methylators of mercury in anoxic estuarine sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 50, 498–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covelli S, Faganeli J, Horvat M, Brambati A, 2001. Mercury contamination of coastal sediments as the result of long-term cinnabar mining activity (Gulf of Trieste, northern Adriatic sea). Appl. Geochem 16, 541–558. [Google Scholar]

- Dent SR, Beutel MW, Gantzer P, Moore BC, 2014. Response of methylmercury, total mercury, iron and manganese to oxygenation of an anoxic hypolimnion in North Twin Lake, Washington. Lake Reservoir Manag. 30, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- DeWild JF, Olson ML, Olund SD, 2002. Determination of Methyl Mercury by Aqueous Phase Ethylation, Followed by Gas Chromatographic Separation with Cold Vapor Atomic Fluorescence Detection Middleton, Wis. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Denver, CO. U.S. Geological Survey ; Branch of Information Services; [distributor]. [Google Scholar]

- DeWild JF, Olund SD, Olson ML, Tate MT, 2004. Methods for the Preparation and Analysis of Solids and Suspended Solids for Methylmercury. Techniques and Methods. 5. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll CT, Mason RP, Chan HM, Jacob DJ, Pirrone N, 2013. Mercury as a global pollutant: sources, pathways, and effects. Environ. Sci. Technol 47, 4967–4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvil R, Beutel MW, Fuhrmann B, Seelos M, 2018. Effect of oxygen, nitrate and aluminum addition on methylmercury efflux from mine-impacted reservoir sediment. Water Res. 144, 740–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckley CS, Hintelmann H, 2006. Determination of mercury methylation potentials in the water column of lakes across Canada. Sci. Total Environ 368, 111–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckley CS, Watras CJ, Hintelmann H, Morrison K, Kent AD, Regnell O, 2005. Mercury methylation in the hypolimnetic waters of lakes with and without connection to wetlands in northern Wisconsin. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci 62, 400–411. [Google Scholar]

- Eckley CS, Luxton TP, Goetz J, McKernan J, 2017. Water-level fluctuations influence sediment porewater chemistry and methylmercury production in a flood-control reservoir. Environ. Pollut 222, 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckley CS, Gilmour CC, Janssen S, Luxton TP, Randall PM, Whalin L, et al. , 2020. The assessment and remediation of mercury contaminated sites: a review of current approaches. Sci. Total Environ 707, 136031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckley CS, Luxton TP, Knightes CD, Shah V, 2021. Methylmercury production and degradation under light and dark conditions in the water column of the hells Canyon reservoirs, USA. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 40 (7), 1829–1839. 10.1002/etc.5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA, U., 1996. Method 1669: Sampling Ambient Water for Trace Metals at EPA Water Quality Criteria Levels. EPA-821 R-96–008, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour CC, Riedel GS, Ederington MC, Bell JT, Gill GA, Stordal MC, 1998. Methylmercury concentrations and production rates across a trophic gradient in the northern Everglades. Biogeochemistry 40, 327–345. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour CC, Podar M, Bullock AL, Graham AM, Brown SD, Somenahally AC, et al. , 2013. Mercury methylation by novel microorganisms from new environments. Environ. Sci. Technol 47, 11810–11820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Eyles JL, Yupanqui C, Beckingham B, Riedel G, Gilmour C, Ghosh U, 2013. Evaluation of biochars and activated carbons for in situ remediation of sediments impacted with organics, mercury, and methylmercury. Environ. Sci. Technol 47, 13721–13729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt CR, Fitzgerald WF, 2006. Photodecomposition of methylmercury in an arctic alaskan lake. Environ. Sci. Technol 40, 1212–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt CR, Fitzgerald WF, Lamborg CH, Balcom PH, Tseng CM, 2006. Biogeochemical cycling of methylmercury in lakes and tundra watersheds of Arctic Alaska. Environ. Sci. Technol 40, 1204–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintelmann H, Keppel-Jones K, Evans RD, 2000. Constants of mercury methylation and demethylation rates in sediments and comparison of tracer and ambient mercury availability. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 19, 2204–2211. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu-Kim H, Kucharzyk KH, Zhang T, Deshusses MA, 2013. Mechanisms regulating mercury bioavailability for methylating microorganisms in the aquatic environment: a critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol 47, 2441–2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu-Kim H, Eckley CS, Acha D, Feng XB, Gilmour CC, Jonsson S, et al. , 2018. Challenges and opportunities for managing aquatic mercury pollution in altered landscapes. Ambio 47, 141–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerin EJ, Gilmour CC, Roden E, Suzuki MT, Coates JD, Mason RP, 2006. Mercury methylation by dissimilatory iron-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 72, 7919–7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthals ET, Winfrey MR, 1987. Seasonal and spatial variations in mercury methylation and demethylation in an oligotrophic lake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 53, 2397–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Cai Y, 2013. Progress in the study of mercury methylation and demethylation in aquatic environments. Chin. Sci. Bull 58, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Mao Y, Liu G, Tachiev G, Roelant D, Feng X, et al. , 2010. Degradation of methylmercury and its effects on mercury distribution and cycling in the Florida Everglades. Environ. Sci. Technol 44, 6661–6666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DA, Babcock DB, Nolan JG, Prestigiacomo AR, Effler SW, Driscoll CT, et al. , 2013. Whole-lake nitrate addition for control of methylmercury in mercury-contaminated Onondaga Lake, NY. Environ. Res 125, 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain ME, Boyer EW, Dent CL, Gergel SE, Grimm NB, Groffman PM, et al. , 2003. Biogeochemical hot spots and hot moments at the interface of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Ecosystems 6, 301–312. [Google Scholar]

- McCord SA, Beutel MW, Dent SR, Schladow SG, 2016. Evaluation of mercury cycling and hypolimnetic oxygenation in mercury-impacted seasonally stratified reservoirs in the Guadalupe River watershed, California. Water Resour. Res 52, 7726–7743. [Google Scholar]

- IRIS, 2001. Methylemercury (MeHg); CASRN 22967–92-6. In: System IRI, Editor. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, National Center for Environmental Assessment Cincinnati, OH. [Google Scholar]

- Millard G, Driscoll C, Montesdeoca M, Yang Y, Taylor M, Boucher S, et al. , 2020. Patterns and trends of fish mercury in New York State. Ecotoxicology 29, 1709–1720. 10.1007/s10646-020-02163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CPJ, Gilmour CC, 2008. Methylmercury production in a Chesapeake Bay salt marsh. Jof Geophys Res-Biogeosciences 113. [Google Scholar]

- Monterey County Water Resources Agency, 2022. Reservoir Data. Monterey County Water Resources Agency, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Morel FMM, Kraepiel AML, Amyot M, 1998. The chemical cycle and bioaccumulation of mercury. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Systemat 29, 543–566. [Google Scholar]

- Olund SD, DeWild JF, Olson ML, Tate MT, 2004. Methods for the Preparation and Analysis of Solids and Suspended Solids for Total Mercury. Techniques and Methods. 5. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Oremland RS, Culbertson CW, Winfrey MR, 1991. Methylmercury decomposition in sediments and bacterial cultures: involvement of methanogens and sulfate reducers in oxidative demethylation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 57, 130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poste AE, Braaten HF, de Wit HA, Sorensen K, Larssen T, 2015. Effects of photodemethylation on the methylmercury budget of boreal Norwegian lakes. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 34, 1213–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R, 2019. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran M, Aiken GR, Reddy MM, Ryan JN, 1998. Enhanced dissolution of cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) by dissolved organic matter isolated from the Florida everglades. Environ. Sci. Technol 32, 3305–3311. [Google Scholar]

- Schartup AT, Mason RP, Balcom PH, Hollweg TA, Chen CY, 2013. Methylmercury production in estuarine sediments: role of organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol 47, 695–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudder BC, Chasar LC, Wentz DA, Bauch NJ, Brigham ME, Moran PW, Krabbenhoft DP, 2009. Mercury in Fish, Bed Sediment, and Water from Streams across the United States, 1998–2005. U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report USGS, p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Seelos M, Beutel M, Austin CM, Wilkinson E, Leal C, 2020. Effects of hypolimnetic oxygenation on fish tissue mercury in reservoirs near the new Almaden Mining District, California, USA. Environ. Pollut 268, 115759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers P, Kelly CA, Rudd JWM, MacHutchon AR, 1996. Photodegradation of methylmercury in lakes. Nature 380, 694–697. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers P, Kelly CA, Rudd JWM, 2001. Fluxes of methylmercury to the water column of a drainage lake: the relative importance of internal and external sources. Limnol. Oceanogr 46, 623–631. [Google Scholar]

- Skyllberg U, Qian J, Frech W, Xia K, Bleam WF, 2003. Distribution of mercury, methyl mercury and organic sulphur species in soil, soil solution and stream of a boreal forest catchment. Biogeochemistry 64, 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JA, Kallemeyn LW, Sydor M, 2005. Relationship between mercury accumulation in young-of-the-year yellow perch and water-level fluctuations. Environ. Sci. Technol 39, 9237–9243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AR, Saiki MK, Kuwabara JS, Alpers CN, Marvin-DiPasquale M, Krabbenhoft DP, 2008. Influence of plankton mercury dynamics and trophic pathways on mercury concentrations of top predator fish of a mining-impacted reservoir. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci 65, 2351–2366. [Google Scholar]

- Tjerngren I, Karlsson T, Björn E, Skyllberg U, 2011. Potential Hg methylation and MeHg demethylation rates related to the nutrient status of different boreal wetlands. Biogeochemistry 108, 335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui MT, Finlay JC, Nater EA, 2008. Effects of stream water chemistry and tree species on release and methylation of mercury during litter decomposition. Environ. Sci. Technol 42, 8692–8697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich SM, Tanton TW, Abdrashitova SA, 2001. Mercury in the aquatic environment: a review of factors affecting methylation. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol 31, 241–293. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Gao B, Fang J, 2017. Recent advances in engineered biochar productions and applications. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol 47, 2158–2207. [Google Scholar]

- Watras CJ, Bloom NS, Claas SA, Morrison KA, Gilmour CC, Craig SR, 1995. Methylmercury production in the anoxic hypolimnin of a dimictic seepage lake. Water Air Soil Pollut. 80, 735–745. [Google Scholar]

- Watras CJ, Morrison KA, Kent A, Price N, Regnell O, Eckley C, et al. , 2005. Sources of methylmercury to a wetland-dominated lake in northern Wisconsin. Environ. Sci. Technol 39, 4747–4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watras C, Grande D, Latzka A, Tate L, 2018. Mercury trends and cycling in northern Wisconsin related to atmospheric and hydrologic processes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci 76, 831–846. [Google Scholar]

- Willacker JJ, Eagles-Smith CA, Lutz MA, Tate MT, Lepak JM, Ackerman JT, 2016. Reservoirs and water management influence fish mercury concentrations in the western United States and Canada. Sci. Total Environ 568, 739–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is available online at science.gov