Abstract

Psychological dysfunction is one of the considerable health-related outcomes among critically-ill patients and their informal caregivers. Follow-up of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors has been conducted in a variety of different ways, with different timing after discharge, targets of interest (physical, psychological, social) and measures used. Of diverse ICU follow-up, the effects of follow-ups which focused on psychological interventions are unknown. Our research question was whether follow-up with patients and their informal caregivers after ICU discharge improved mental health compared to usual care. We published a protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis in https://www.protocols.io/ (https://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bvjwn4pe). We searched PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycInfo from their inception to May 2022. We included randomized controlled trials for follow-ups after ICU discharge and focused on psychological intervention for critically ill adult patients and their informal caregivers. We synthesized primary outcomes, including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and adverse events using the random-effects method. We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach to rate the certainty of evidence. From the 10,471 records, we identified 13 studies (n = 3, 366) focusing on patients and four (n = 538) focusing on informal caregivers. ICU follow-up for patients resulted in little to no difference in the prevalence of depression (RR 0.89, 95% CI [0.59–1.34]; low-certainty evidence) and PTSD (RR 0.84, 95% CI [0.55–1.30]; low-certainty evidence) among patients; however, it increased the prevalence of depression (RR 1.58 95% CI [1.01–2.46]; very low-certainty evidence), PTSD (RR 1.36, 95% CI [0.91–2.03]; very low-certainty evidence) among informal caregivers. The evidence for the effect of ICU follow-up on adverse events among patients was insufficient. Eligible studies for informal caregivers did not define any adverse event. The effect of follow-ups after ICU discharge that focused on psychological intervention should be uncertain.

Keywords: Intensive care units, Critical care, Mental disorders, Post intensive care syndrome

Introduction

Adult patients who are admitted to intensive care units (ICU) and their informal caregivers may experience psychological dysfunction, which can persist following discharge (Needham et al., 2012). Psychological dysfunction of critically-ill adult patients and their informal caregivers is called post intensive care syndrome (PICS) and PICS-Family (PICS-F), respectively. Other symptoms of PICS include cognitive and physical impairments. Previous studies found that the prevalence of these patients with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety was approximately 29% (Rabiee et al., 2016), 34% (Parker et al., 2015), and 34% (Nikayin et al., 2016) after one year of ICU discharge. Studies have also reported that the prevalence of acquired psychological dysfunction among informal caregivers was similar to that among patients (Johnson et al., 2019). Therefore, psychological dysfunction is a considerable health-related outcome among critically-ill patients and their informal caregivers.

According to the current guidelines and a systematic review (SR), follow-up with patients who have been admitted to the ICU is comprised of a variety of contents, targets, and times of initiation (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Rosa et al., 2019). The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines for follow-ups recommended providing enhanced or individualized physical intervention from early mobilization to home rehabilitation (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009). One SR found that the intervention that was initiated in the ICU and continued after ICU discharge included diary and physical rehabilitation (Rosa et al., 2019). In addition, the SR did not separately investigate patients and informal caregivers. Similarly, the counterplan for PICS-F was the ICU diary and communication in the ICU. Another SR showed that care providers and informal caregivers regarded the ICU diary as beneficial (Brandao Barreto et al., 2021), while another SR asserted that communication in the ICU might reduce symptoms of depression and PTSD (DeForge et al., 2022). It would be obvious that these interventions which initiated in the ICU reduced psychological problems of patients and informal caregivers. Moreover, a recent SR studied psychological intervention for patients’ informal caregivers, but did not separately investigate adult patients and pediatric patients (Cherak et al., 2021). In a pediatric randomized controlled trial (RCT), interventions were specifically designed for children such as skin-to-skin contact (Mörelius et al., 2015), kangaroo care (Ettenberger et al., 2017), or guidance for baby care (Fotiou et al., 2016). There was clinical heterogeneity among the included studies in the previous SR. Hence, the effects of follow-ups for adult patients and informal caregivers that focused on psychological interventions after ICU discharge have remained unknown.

Thus, the objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis (SR/MA) was to investigate the following research question: does follow-up with adult patients and their informal caregivers following ICU discharge improve mental health compared to usual care?

Materials & Methods

Protocol and registration

We published a protocol for this SR/MA in http://www.protocols.io (Yoshihiro et al., 2021). We conducted this SR/MA in accordance with guidelines prescribed by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al., 2020) and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021). The principles listed in the PRISMA statement formed the basis of our SR/MA report (Page et al., 2021) (Table S1).

Eligibility criteria

Studies

We included randomized controlled trials that assessed the effects of follow-up after ICU discharge on mental health outcomes among adult patients and informal caregivers. We analyzed papers including published and unpublished articles, abstracts of conferences, and condolence letters. We excluded studies with cluster randomized or quasi-randomized trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, and case series. Furthermore, while including studies for this SR/MA, we did not apply restrictions pertaining to language, country, observation period, or publication year.

In May 2021, we searched the following databases: MEDLINE (PubMed), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Cochrane Library), EMBASE (Dialog), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (accessed via EBSCO), and APA PsycInfo (Ovid). In May 2021, we searched for ongoing and unpublished trials in trial registers such as ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Platform Search Portal (WHO ICTRP), respectively. Details of these searches have been listed in the protocol (Yoshihiro et al., 2021). We conducted a ‘snowball’ search to identify studies that used reference lists of publications eligible for full-text review (including international guidelines) (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Nolan et al., 2021) and used Google Scholar to identify and screen those studies. We reconducted these searches in May 2022. Additionally, we contacted the authors of the original studies for unpublished or additional data.

Population

We included trials with adult patients (age ≥18 years) admitted to ICUs and their informal caregivers; these trials were randomized during both ICU and hospital discharge. We included studies involving informal caregivers regardless of whether the admitted patient survived. We excluded studies involving patients and their caregivers who were younger than 18 years, did not provide consent for participation, or showed cognitive impairment. Furthermore, studies involving patients or caregivers who had experienced myocardial infarction or were in their perioperative period were excluded. In this article, we have referred to our target population of “critically-ill adult patients” as “patients.” if not necessary.

Interventions

We defined intervention as a service or program initiated after ICU discharge (within one month after hospital discharge), including multidisciplinary interventions, follow-up clinics, and other programs. In the included studies, we recognized counseling such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, that interventions target mental health conditions. In addition, we included psychological intervention performed as needed after monitoring. We incorporated all intervention periods by all professionals. In the included studies, nurses and physicians intervening in therapies had been trained for each study.

We excluded studies involving interventions in the ICU that were comprised of participant-led initiatives like ICU diaries and ICU records, interventions that provided general information pertaining to post-intensive care syndrome using web tools or video materials, or that compared enhanced physical rehabilitation with usual care. We did not predefine the details of the psychological interventions because we wanted to verify interventions that improved psychological outcomes other than physical and diary interventions.

Outcomes

We included trials with defined clinical outcomes, such as symptoms of depression and PTSD, and all adverse events were considered primary outcomes among patients and caregivers (Marra et al., 2018). Additional outcomes among patients included anxiety, health-related quality of life (HR-QoL), pain, readmission, and long-term mortality; additional outcomes among caregivers included anxiety and HR-QoL. We followed core outcome sets (Angus & Carlet, 2003; Major et al., 2016; Needham et al., 2017). We selected outcomes for mental health as primary outcomes. We defined depression, PTSD, and anxiety as the prevalence rate of significant symptoms based on definitions by the included studies’ authors, measured between three months and one year after randomization or ICU discharge. We defined adverse events using the incidence proportion of all adverse events set by the original authors during the follow-up period of included studies. We defined HR-QoL using a mental component summary of the Medical Health Survey Short-Form 36 (SF-36), measured between three months and one year after randomization or ICU discharge. SF-36 was used for self-reported evaluation scales for the evaluation of HR-QoL (Angus & Carlet, 2003; Needham et al., 2017). If the outcome of HR-QoL was measured by other self-reported evaluation scales in included studies, we assessed whether the scales could be synthesized with SF-36. We defined pain using self-reported evaluation scales for pain set by the original authors, measured between three months and one year after randomization or ICU discharge. We defined readmission as the proportion of readmission (at least once) during the follow-up period of the included studies. For long-term mortality, we collected the reported mortality at the longest timepoint available in the study, which ranged between 3 and 12 months after randomization.

Search strategy

Selection process

Three reviewers (SY, YK, and KS) independently screened the titles and abstracts of records during the initial screening. We assessed records—included in the initial screening—for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria by reading the full texts. We resolved disagreements between two reviewers via discussion with a third reviewer (TS) to achieve consensus. We combined machine learning classifiers during the selection process (Marshall et al., 2018).

Data collection process

Three reviewers (SY, YK, and KS) independently extracted data from the included studies using a standardized data collection form. We pre-checked the form by using 10 randomly selected studies. We extracted the following characteristics:

Methods: Study design, study follow-up period, and study country;

Participants: Country, setting, mental condition (depression, PTSD, and anxiety), sample size, age, relationship of informal caregivers with patients, and attrition;

Interventions: type, intervention about the psychological problem, providers, media, initiation, duration, and frequency;

Outcomes: primary and additional outcomes specified and collected, and the timepoints reported.

Data items

Study risk-of-bias assessment

Two to three reviewers (SY, YK, and KS) independently classified the risk of bias as “low”, indicating “some concerns”, or “high” based on the Risk-of-Bias 2.0 (Sterne et al., 2019). We resolved disagreements between two reviewers via discussion with the third reviewer (TS) to achieve consensus. As participants could not be blinded to the intervention owing to its nature, we assessed the overall risk-of-bias using four domains, which excluded the estimation of measurement-of-outcome.

Effect measures

We analyzed the dichotomous variables by calculating risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We analyzed the continuous variables using standard mean differences (SMD) with 95% CI.

Synthesis methods

We synthesized the collected variables (except for adverse events) using the random-effects method; data for patients and informal caregivers were synthesized separately. We used the Review Manager software (RevMan 5.4.2) for quantitative synthesis.

Dealing with missing data

We used available data published and inquired to authors. We performed (modified) intention-to-treat data for all dichotomous data as much as possible. For continuous data, we did not impute missing data and performed a meta-analysis of the available data in the original studies and the converted data from available data based on the method in the Cochrane handbook (Higgins et al., 2020).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot and I2 statistics (I2 values of 0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity). We performed Cochrane Chi2 test(Q-test) for I2 statistic and defined P values less than 0.10 as statistically significant.

Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis

We conducted the sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis for the primary outcomes where sufficient data were available. We conducted sensitivity analysis of patients using studies measured by the Depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale(HADS-D) score for depression, studies measured by the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) score for PTSD, and exclusion of imputed data. We conducted the sub-group analyses by timing for initiation of follow-up(in-hospital, out-hospital, or in- and out-hospital). For analysis for informal caregivers, we conducted sensitivity analysis using studies measured by IES-R scores for PTSD. We divided the ICU survivors and non-survivors in the sub-group analyses for informal caregivers.

Reporting bias assessment

We identified the number of studies that had not been published on ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO ICTRP. We assessed outcome reporting bias by comparing the outcomes defined in trial protocols with the outcomes reported in the publications. We assessed the publication bias of outcomes by visual inspection of the funnel plots.

Certainty assessment

Two reviewers (SY and TU) evaluated the certainty of evidence based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Hultcrantz et al., 2017). We resolved disagreements between two reviewers via discussion with the third reviewer (KY) to achieve consensus. We generated a table to summarize the findings of the seven outcomes (except for long-term mortality) using GRADE Pro GDT (https://gradepro.org) based on the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins et al., 2020). We selected the following outcomes for patients: (1) depression, (2) PTSD, (3) all adverse events, (4) anxiety, (5) HR-QoL, (6) pain, and (7) readmission. We selected the following outcomes for informal caregivers: (1) depression, (2) PTSD, (3) all adverse events, (4) anxiety, and (5) HR-QoL.

Difference between protocol and review

We did not conduct Egger’s test as we synthesized data from fewer than 10 studies. We could not conduct planned sensitivity and sub-group analyses for PTSD and adverse events among patients and depression and adverse events among informal caregivers. We added a sub-group analysis for the endpoints of the measured outcomes, dividing them into 6 months and 12 months.

Results

Study selection

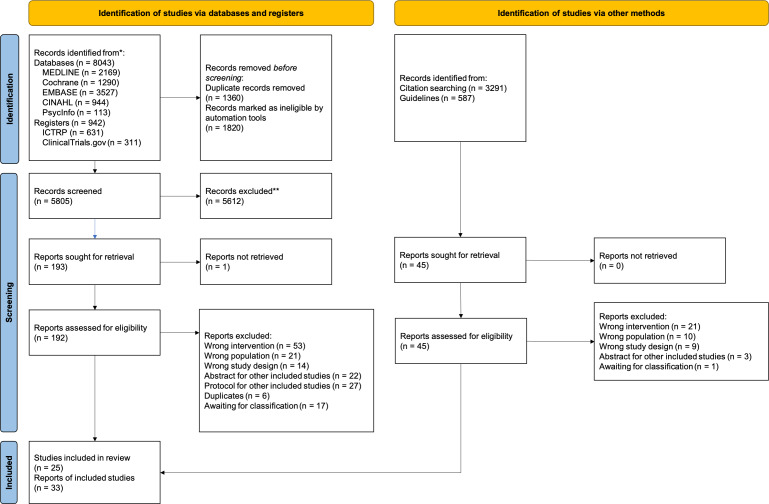

We identified 10,425 records from databases and registers, and 46 records from citation searches and guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Nolan et al., 2021). After excluding duplicates, we could not retrieve the full text for one record from the Cochrane Library and confirmed that the record was an error through author inquiry. We assessed 240 full texts for eligibility and identified 119 studies. The flow diagram for study selection is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow.

We identified six ongoing studies and one no-information study with patients, and one ongoing study with informal caregivers via ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO ICTRP. The details of all studies without results are outlined in Table S2. We excluded 92 studies after conducting full-text reviews; the reasons for their exclusion are listed in Table S3.

Since 12 of the included studies did not include results (Chen et al., 2022; Ewens et al., 2019; Friedman et al., 2022; Gawlytta et al., 2020; Gawlytta et al., 2017; Haines et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2018; Moulaert et al., 2015; Ojeda et al., 2021; Rohr et al., 2021) (NCT03431493, NCT03926533, NCT04329702), we included 15 studies for quantitative analysis. Of these 15 studies, 11 focused on patients (Abdelhamid et al., 2021; Bloom et al., 2019; Cox et al., 2018; Cox et al., 2019; Cuthbertson et al., 2009; Daly et al., 2005; Douglas et al., 2005; Douglas et al., 2007; Hernández et al., 2014; Kredentser et al., 2018; McWilliams, Benington & Atkinson, 2016; Schmidt et al., 2016; Schmidt et al., 2020; Valsøet al., 2020; Vlake et al., 2021), two focused on informal caregivers (Ågren et al., 2019; Kentish-Barnes et al., 2017), and two focused on both patients and informal caregivers (Bohart et al., 2019; Jensen et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2004; Jones et al., 2003). One study (Cox et al., 2018) was conducted with both patients and informal caregivers, but we could not retrieve outcome data for the informal caregivers. The details of these studies are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Included studies.

| (A) Patients | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors year | Registry Number Country Observational period | No of participants Age, years Intervention/Control | Mental condition Intervention/Control | Attrition, % | Type of intervention | Type of intervention against psychological problem | Professionals/ sources of intervention | Timing, duration, and/or frequency of intervention |

| Jones et al. (2003) | Not stated about registration the United Kingdom six months after ICU discharge | 69/57 Mean ± SD, 57 ± 17/59 ± 16 | Depression not stated; PTSD not stated; Anxiety not stated | 19 | Semi-structured programs for psychological, psychosocial, and physical problems | Provision of coping skills | Print media | After ICU discharge six weeks from one week |

| Daly et al. (2005) | No detail of registration the United States of America two months after hospital discharge | 231/103 Mean ± SD, 60.7 ± 16.6/ 61.4 ± 16.1 | Depression not stated; PTSD not stated; Anxiety not stated | 26 | Multidisciplinary intervention by nurse with support from a physician | Provision of coping skills | Nurse | After hospital discharge Two months |

| Cuthbertson et al. (2009) | ISRCTN24294750 The United Kingdom 12 months after ICU discharge | 143/143 Median (IQR), 59 (46–49)/60 (46–71) | Depression not stated; PTSD not stated; Anxiety not stated | 32.9 | Multidisciplinary intervention by nurse with support from an intensivist | Psychological intervention required after monitoring | Nurse | After hospital discharge Two times at 3 months and 9 months |

| Jensen et al. (2016) | NCT01721239 Denmark 12 months after ICU discharge | 190/196 Median (IQR), 66 (57.75–73.5)/67.5 (58–75) | Depression not stated; PTSD not stated; Anxiety not stated | 39.1 | Individualized, semi-structured program for psychological problem | Therapy: Cognitive behavioral therapy | Nurse | After ICU discharge Three times at 1–3, 5, and 10 months |

| McWilliams, Benington & Atkinson (2016) | NCT02491021 The United Kingdom seven weeks after hospital discharge | 37/36 Mean ± SD, 55.0 ± 12.9, 60.8 ± 12.3 | Depression not stated; PTSD not stated; Anxiety not stated | 13.7 | Rehabilitation program consisted of exercise and education component | Education | Nurse; Facilitators other than physician and nurse | After hospital discharge Total 6 educational sessions, 1 h per session, for 7 weeks |

| Schmidt et al. (2016) | ISRCTN61744782 Germany 12 months after ICU discharge | 148/143 Mean ± SD, 62.1 ± 14.1/ 61.2 ± 14.9 | Depression not stated; PTSD not stated; Anxiety not stated | 30.6 | Case management, telephone monitoring, and education of behavioral activation for patients, which consisted of general practitioner, case manager, and liaison physician | Provision of coping skills | Nurse; Physician | After ICU discharge Monthly for 6 months, and once every 3 months for the final 6 months |

| Cox et al. (2018) | NCT01983254 The United States of America 12 months after randomization (within two weeks after hospital discharge) | 39/47 Mean ± SD, 49.7 ± 13.8/53.7 ± 13.5 | Patients Depression 27/20 PTSD 4/6 Anxiety 24/17 | Patients 25.1 | Training for psychological problems, combined with Telephone and web | Provision of coping skills | Facilitators other than physician and nurse; Digital media | After hospital discharge six telephone sessions for thirty minutes, once per week |

| Bloom et al. (2019) | NCT03124342 The United States of America 30 days after hospital discharge | 145/157 Median (IQR), 56 (44–67), n = 111/56 (48–66), n = 121 | Depression Not stated; PTSD not stated; Anxiety Not stated | 27.5 | Multidisciplinary case management based on ICU recovery program | Psychological intervention required after monitoring | Nurse; Physician; Facilitators other than physician and nurse | After hospital discharge At least 30 days |

| Cox et al. (2019) | NCT02701361 The United States of America Three months after hospital discharge | 1) Telephone-based mindfulness training, 31/18 Mean ± SD, 48.1 ± 16.1/53.3 ± 12.6 | 1) Depression 4/1 PTSD 1/1 Anxiety 6/1 | 1) 10.2 | 1) Telephone-based training for psychological problems | 1) Provision of coping skills | 1) Facilitator other than physician and nurse | After hospital discharge Four sessions each week for one month |

| 2) Self-directed mindfulness training by mobile app, 31/18 Mean ± SD, 48.7 ± 15.3/53.3 ± 12.6 | 2) Depression 1/1 PTSD 2/0 Anxiety 2/1 | 2) 22.4 | 2) Self-directed training for psychological problems | 2) Provision of coping skills | 2) Digital media | |||

| Kredentser et al. (2018) | NCT02067559 Canada 90 days after ICU discharge | Sample size of usual care and psychoeducation in four arms 14/14 Mean ± SD, 59.3 ± 15.5/49.9 ± 16.9 | Depression not stated; PTSD not stated; Anxiety not stated | 60.7 | Education for psychological problem | Provision of coping skills | Print media | After ICU discharge or after return of the ability to provide consent |

| Valsøet al. (2020) | NCT02077244 Kingdom of Norway Twelve months after ICU discharge | 111/113 Mean ± SD, 53 ± 16/50 ± 18 | Depression not stated; PTSD 111/113; Anxiety not stated | 23.7 | Individualized, semi-structured program for psychological and psychosocial problems | Therapy: Cognitive behavioral therapy | Nurse | After ICU discharge three times in the first week, one and two months later |

| Abdelhamid et al. (2021) | ACTRN12616000206426 Australia six months after hospital discharge | 21/21 Mean ± SD, 64 ± 11/68 ± 8 | Depression not stated; PTSD not stated; Anxiety not stated | 38.1 | Multidisciplinary intervention by an intensivist and endocrinologist | Psychological intervention required after monitoring | Physician | After hospital discharge At least one time, repeated as needed for six months from one month |

| Vlake et al. (2021) | NL6611 Netherlands six months after ICU discharge | 25/25 Median (95% range), 61 (23-75)/59 (59–80) | Depression 6/12 PTSD 12/13; Anxiety not stated | 16 | ICU-specific virtual reality for psychological problem | Therapy: Virtual reality exposure therapy | Digital media | After ICU discharge The number of desired sessions was offered daily |

Notes.

- IQR

- Interquartile range

- ICU

- intensive care unit

- SD

- standard deviation

- PTSD

- post-traumatic stress disorder

Study characteristics

We selected 13 studies that included 3,366 patients (Table 1A). These studies were conducted in eight countries: the USA (n = 4), the UK (n = 3), and Denmark, Germany, Norway, Netherlands, Canada, and Australia (n = 1 in each country). Patients in two studies had sepsis, and patients in six studies were provided mechanical ventilation. One study included patients with moderate PTSD symptoms after ICU discharge. Interventions in six studies focused on psychological problems among patients following critical illness. Interventions in seven studies included rehabilitation programs, multidisciplinary programs, and case management for monitoring and therapy for psychological problems.

We selected four studies, which included 538 informal caregivers (Table 1B). These studies were conducted in four countries: the UK, Denmark, France, and Sweden (n = 1 in each country). Most caregivers were spouses (47.8%), followed by children (16.8%), parents (9.3%), and siblings (1.3%) of the patients. All the studies included informal caregivers with or without psychological problems. Follow-ups were conducted on patients and caregivers in three studies, while one study conducted interventions on caregivers of the ICU non-survivor.

Risk of bias in studies

The domains and overall risk of bias for each outcome are outlined in Fig S1. On the assessment of the randomization process, we found that one study (Daly et al., 2005) showed risk-of-bias concerns owing to no description of the details of concealment, and two studies (Ågren et al., 2019; Bloom et al., 2019) showed high risk of bias owing to an imbalance of patient characteristics. On the assessment of deviation from the intended interventions, we found that three studies (Ågren et al., 2019; Cox et al., 2019; Daly et al., 2005) showed some risk-of-bias concerns owing to the difference of drop-outs between each group, and one study (Kredentser et al., 2018) had a high risk of bias owing to no information and no conduct of modified intention for treatment. On the assessment of the missing outcome data, we found that four studies (Cox et al., 2018; Cox et al., 2019; Jensen et al., 2016; Vlake et al., 2021) had a low risk of bias for implementation of missing values; however, 10.2–52.1% of the participants dropped out in all eligible studies. The assessment of the outcome measurement indicated that all studies had a high risk of bias for outcomes estimated via self-reported questionnaires as patients could not be blinded to the interventions owing to their nature.

Patient outcomes

Depression

As shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2, ICU follow-ups resulted in little to no differences in the prevalence rate of depressive symptoms among patients (RR 0.89, 95% CI [0.59, 1.34]; I2 = 1%; four studies, 758 patients; low-certainty evidence) (Abdelhamid et al., 2021; Jensen et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2003; Schmidt et al., 2016; Vlake et al., 2021); we detected slight heterogeneity. Planned sensitivity analyses of studies using the Depression subscale scores of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) yielded similar findings (RR 0.90, 95% CI [0.50–1.63]). Planned sensitivity analysis that excluded the imputed data showed a similar trend (RR 1.08, 95% CI [0.55–2.09]). Sub-group analysis for the timing of follow-up initiation showed a similar trend in the group of initiation from both ICU discharge and hospital discharge. In the sub-group analysis, there was no difference in the endpoint to measure depressive symptoms between 6 months and 12 months. Details of the analysis are provided in Fig S2.

Figure 2. Forest plot and funnel plot of primary outcomes for patients.

(A) Depression, (B) Post-traumatic stress disorder. Adverse events were not pooled.

Table 2. Summary of findings for patients.

| ICU follow-up compared to usual care for critically ill patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient or population: Critically ill patients | ||||||

| Setting: | ||||||

| Intervention: ICU follow-up | ||||||

| Comparison: Usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with Usual care | Risk with ICU follow-up | (95% CI) | (studies) | (GRADE) | ||

| Proportion of patients with depression | Median 114 per 1,000 | 101 per 1,000 | RR 0.89 | 758 | ||

| (67 to 152) | (0.59 to 1.34) | (5 RCTs) | Lowa,b | |||

| Proportion of patients with PTSD | Median 145 per 1,000 | 122 per 1,000 | RR 0.84 | 732 | ||

| (80 to 188) | (0.55 to 1.30) | (4 RCTs) | Lowa,b | |||

| All adverse events | Median 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 | Not estimable | 42 | ||

| (0 to 0) | (1 RCT) | Very lowa,c | ||||

| Proportion of patients with anxiety | Median 206 per 1,000 | 214 per 1,000 | RR 1.04 | 488 | ||

| (140 to 329) | (0.68 to 1.60) | (2 RCTs) | Lowa,b | |||

| HR-QoL | – | SMD 0.05 higher | – | 905 | ||

| (0.08 lower to 0.18 higher) | (8 RCTs) | Lowa,b | ||||

| Pain | – | SMD 0.08 lower | – | 258 | ||

| (0.32 lower to 0.17 higher) | (3 RCTs) | Lowa,b | ||||

| Readmission | Median 274 per 1,000 | 261 per 1,000 | RR 0.95 | 1016 | ||

| (211 to 318) | (0.77 to 1.16) | (8 RCTs) | Lowa,b | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| Confidence interval, CI; health-related quality of life; HR-QoL; intensive care unit, ICU; odds ratio; OR; risk ratio RR; standardized mean difference, SMD; post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD; randomized controlled trial, RCT. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

|

Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | ||||||

| Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

| Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

Notes.

Downgrade for a high risk of bias: Some included studies assessed presented some concerns.

Downgrade for imprecision: The sample size was small.

Downgrade for imprecision: Outcome was reported in only 1 study.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

ICU follow-ups resulted in little to no differences in the prevalence rate of PTSD symptoms among patients (RR 0.84, 95% CI [0.55–1.30]; I2 = 53%; four studies, 732 patients; low-certainty evidence) (Jensen et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2003; Schmidt et al., 2016; Vlake et al., 2021); we detected moderate heterogeneity (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Planned sensitivity analysis of studies using the Impact of Event Scale- Revised scores (IES-R) yielded similar results (RR 0.51, 95% CI [0.08–3.23]). The planned sensitivity analysis that excluded the imputed data generated similar findings (RR 1.06, 95% CI [0.75–1.50]; Fig. S2). Sub-group analysis for the endpoint to measure PTSD symptoms showed a similar trend in the endpoint to measure depressive symptoms between 6 months and 12 months. Details of the analysis are provided in Fig. S2.

Adverse events

Although evidence indicates considerable uncertainty, ICU follow-ups resulted in little to no differences in the occurrence of adverse events (Vlake et al., 2021) (Table 2). Two studies included adverse events as outcome measures (Bloom et al., 2019; Vlake et al., 2021). One published article (Bloom et al., 2019) did not report the results pertaining to adverse events, and we could not obtain information about adverse events from its authors. This study defined adverse events as the need for intervention to prevent events such as mortality, prolonged hospitalization, acquisition of disability, congenital anomalies, and birth defects. Another study (Vlake et al., 2021) defined adverse events as incidents of cybersickness, delirium, or the use of haloperidol. Considering the clinical heterogeneity in studies, we included all types of adverse events except for cybersickness.

Anxiety

ICU follow-ups resulted in little to no differences in the prevalence rate of anxiety symptoms among patients (RR 1.04, 95% CI [0.68–1.60]; I2 = 0%; two studies, 488 patients; low certainty of evidence) (Jensen et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2003); no significant heterogeneity was detected (Table 2 and Fig. S3).

Health-related quality of life

ICU follow-ups resulted in little to no differences in the HR-QoL scores among patients (SMD 0.05, 95% CI [−0.08–0.18]; I2 = 0%; seven studies, 905 patients; low-certainty evidence) (Abdelhamid et al., 2021; Cox et al., 2018; Cox et al., 2019; Cuthbertson et al., 2009; Jensen et al., 2016; Schmidt et al., 2016; Vlake et al., 2021); no significant heterogeneity was detected (Table 2 and Fig. S3). Of the seven studies, four measured the HR-QoL using the Mental Component Summary (MCS) of the Short-Form-36 (SF-36) (Abdelhamid et al., 2021; Cuthbertson et al., 2009; Jensen et al., 2016; Schmidt et al., 2016), one study used the MCS of the SF-12 (Vlake et al., 2021), and two studies used the EuroQoL Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) (Cox et al., 2018; Cox et al., 2019). The analysis of studies using the MCS of the SF-36 and the SF-12 yielded similar findings (SMD 0.04, 95% CI [−0.11–0.19]).

Pain

ICU follow-ups resulted in little to no differences in the pain scores among patients (SMD −0.08, 95% CI [−0.32, 0.17]; I2 = 0%; three studies, 258 patients; low-certainty evidence) (Abdelhamid et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2016; Vlake et al., 2021); no significant heterogeneity was detected (Table 2 and Fig. S3). One study (Schmidt et al., 2016) measured pain intensity using the Graded Chronic Pain Scale; one study (Abdelhamid et al., 2021) used the pain comportment of the SF-36. For one study (Vlake et al., 2021), we obtained data for the pain comportment of the SF-12 which was converted to the VAS 100 scale via author inquiry.

Readmission

ICU follow-ups resulted in little to no significant in the proportion of patients readmitted to the hospital during follow-up periods (RR 0.95, 95% CI [0.77–1.16]; I2 = 18%; seven studies, 1,016 patients; low certainty evidence) (Abdelhamid et al., 2021; Bloom et al., 2019; Cox et al., 2018; Cox et al., 2019; Daly et al., 2005; Jensen et al., 2016; McWilliams, Benington & Atkinson, 2016); no significant heterogeneity was detected (Table 2 and Fig. S3).

Long term mortality

ICU follow-ups resulted in little to no differences in long-term mortality among patients (RR 0.95, 95% CI [0.74–1.21]; I2 = 0%; nine studies, 1,608 patients) (Abdelhamid et al., 2021; Cox et al., 2018; Cuthbertson et al., 2009; Jensen et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2003; Kredentser et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2016; Valsøet al., 2020; Vlake et al., 2021) (Fig. S3); no significant heterogeneity was detected.

Informal caregiver outcomes

Depression

Although the evidence indicated considerable uncertainty, ICU follow-ups increased the prevalence rate of depressive symptoms—measured using the HADS-D—among informal caregivers (RR 1.58 95% CI [1.01–2.46]; one study, 188 caregivers; very low-certainty evidence) (Kentish-Barnes et al., 2017) (Table 3). However, the other two studies (Bohart et al., 2019; Cox et al., 2018) did not report the proportion of informal caregivers with depressive symptoms, but instead provided their HADS-D scores. The point estimate of HADS-D score was higher in the ICU follow-up groups than control; thus, no inconsistencies were observed.

Table 3. Summary of findings for informal caregivers.

| ICU follow-up compared to usual care for caregivers of critically ill patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient or population: Caregivers of critically ill patients | ||||||

| Setting: | ||||||

| Intervention: ICU follow-up | ||||||

| Comparison: Usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with Usual care | Risk with ICU follow-up | (95% CI) | (Studies) | (GRADE) | ||

| Proportion of caregivers with depression | Median 242 per 1,000 | 382 per 1,000 | RR 1.58 | 188 | ||

| (244 to 595) | (1.01 to 2.46) | (1 RCT) | Very lowa,b | |||

| Proportion of caregivers with PTSD | Median 352 per 1,000 | 478 per 1,000 | RR 1.36 | 303 | ||

| (320 to 714) | (0.91 to 2.03) | (2 RCTs) | Very lowa,b | |||

| All adverse events | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | (0 RCTs) | – | |

| Proportion of caregivers with anxiety | Median 318 per 1,000 | 372 per 1,000 | RR 1.17 | 272 | ||

| (264 to 518) | (0.83 to 1.63) | (2 RCTs) | Very lowa,b | |||

| HR-QoL | – | SMD 0.07 lower | - | 133 | ||

| (0.41 lower to 0.27 higher) | (2 RCTs) | Very lowa,c | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| Confidence interval, CI; health-related quality of life; HR-QoL; intensive care unit, ICU; risk ratio RR; standardized mean difference, SMD; post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD; randomized controlled trial, RCT. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

|

Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. | ||||||

| Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. | ||||||

| Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

Notes.

Downgrade for a high risk of bias: This intervention was not able to blind the assessors because of both the nature of intervention and the use of self-reported outcomes.

Downgrade for imprecision: The sample size was small.

Downgrade for imprecision: CI included possibility of both reasonable benefit and harm.

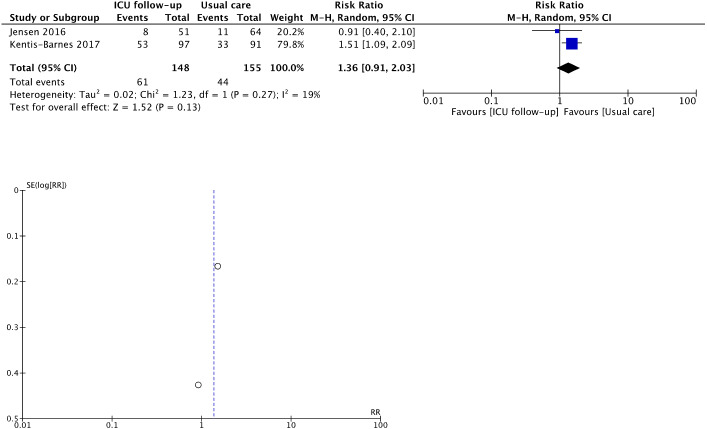

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Although the evidence indicated considerable uncertainty, ICU follow-ups increased the prevalence rate of PTSD symptoms—measured using the IES-R—among informal caregivers (RR 1.36, 95% CI [0.91–2.03]; I2 = 19%; two studies, 303 caregivers; very low certainty of evidence) (Bohart et al., 2019; Kentish-Barnes et al., 2017) (Fig. 3 and Table 3); we detected slight heterogeneity. Planned sensitivity analysis of studies using the IES-R showed that ICU follow-ups significantly increased the proportion of patients with PTSD(RR 1.51, 95% CI [1.09–2.09]) (Fig. S4). One study (Cox et al., 2018) measured the IES-R scores and not the proportion of informal caregivers with PTSD; the point estimate of the IES-R scores was higher for the ICU follow-up group. In a sub-analysis, we found that only caregivers with non-survivors developed PTSD owing to ICU follow-ups (Fig. S4). In another sub-analysis, there was no difference in the endpoint to measure PTSD symptoms between 6 and 12 months.

Figure 3. Forest plot and funnel plot of primary outcomes for informal caregivers.

Post-traumatic stress disorder. Since the outcome of depression was reported in only 1 RCT, we do not show the forest plot and funnel plot. Adverse events were not pooled.

Adverse events

Eligible studies with informal caregivers did not define any adverse events (Table 3).

Anxiety

Although the evidence indicated considerable uncertainty, ICU follow-ups increased the prevalence rate of anxiety symptoms, measured using the Anxiety subscale of the HADS (HADS-A), among informal caregivers (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.63; two studies, 272 caregivers; very low-certainty evidence) (Jones et al., 2004; Kentish-Barnes et al., 2017) (Table 3 and Fig. S5); no significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 0%). One study (Cox et al., 2018) measured the HADS-A scores and not the proportion of caregivers with anxiety; the point estimate of the HADS-A scores was higher for the ICU follow-up group.

Health-related quality of life

Although the evidence indicated considerable uncertainty, ICU follow-ups had little to no effect on the HR-QoL measured using the MCS of the SF-36 among informal caregivers (MD −0.70, 95% CI [−4.51, 3.11]; I2 = 0%; two studies, 133 caregivers; very low certainty of evidence); no significant heterogeneity was detected (Ågren et al., 2019; Bohart et al., 2019) (Table 3 and Fig. S5).

Discussion

Our SR/MA revealed that ICU follow-ups did not decrease the prevalence of depression, PTSD, and anxiety among patients. On the contrary, ICU follow-ups increased the prevalence of depression and PTSD among informal caregivers; however, there was low certainty of evidence. Furthermore, sensitivity and sub- analyses yielded similar results. Although the certainty of the evidence was low, the ICU follow-up did not decrease pain among patients.

The follow-up initiated after ICU discharge did not reduce psychological dysfunction among critically-ill patients. A Cochrane SR focusing on ICU survivors included four RCTs and concluded that the evidence for the efficacy of post-ICU follow-ups was insufficient (Schofield-Robinson et al., 2018). Our SR/MA revealed the ineffectiveness of post-ICU follow-ups for depression and anxiety with greater certainty than the Cochrane SR (Schofield-Robinson et al., 2018). The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009) suggested that medical staff should conduct psychological intervention to monitor and develop preventive or treatment strategies for psychological dysfunction. However, our findings contradicted this guideline. Two reasons may explain this finding. First, the intervention content differed. The guideline (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009) was based on interventions comprised of enhanced or individualized physical rehabilitation; however, we focused on psychological intervention and excluded interventions pertaining to mobilization. Second, the timings of initiation of interventions were different. The guideline (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009) suggested that medical staff might be suitable to assess the need for patient rehabilitation before ICU discharge; however, we focused on interventions initiated after ICU discharge and interventions for psychological dysfunction. Considering our findings, follow-ups focusing on psychological intervention initiated after ICU discharge need not be conducted for patients.

The current approaches to psychological intervention after ICU discharge were not helpful for patients and led to increased depression, PTSD, and anxiety in informal caregivers. Patients and informal caregivers have high levels of depression, anxiety, and PTSD, and the current approaches fail to address this, though it is important to screen for all components of PICS. The guidelines published by the European Resuscitation Council and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine pertained to cardiac arrests among adults (Nolan et al., 2021). Based on qualitative synthesis, the guideline panel suggested that medical staff should monitor and provide information about psychological problems among informal caregivers following patients’ hospital discharge (Nolan et al., 2021). Our SR scoped the only RCTs as a more rigorous study design with narrower eligible criteria than that of the previous SR (Rosa et al., 2019). As for the effect of ICU follow-up on psychological symptoms, our meta-analysis conclusions contradicted that of the previous SRs accordingly (Cherak et al., 2021; Rosa et al., 2019). This could be because of the differences in the target informal caregivers as well as the different design used in the two SRs. A recent SR showed that mental health interventions after ICU discharge may alleviate psychological problems among informal caregivers (Cherak et al., 2021). The primary relationship between informal caregivers and patients in the previous SR was that of parents of children. The primary informal caregivers of critically ill adults in our SR/MA were spouses, so the intervention to reduce psychological modulation in our SR was different from that of the previous SR. Moreover, the SR included quasi-experimental and uncontrolled trials and did not conduct sub-analyses of the relationship with patients. These reasons could lead to negative results. Although it is necessary to monitor psychological dysfunction among informal caregivers, follow-ups might have both positive and harmful effects on depression, PTSD, and anxiety among informal caregivers (after the ICU discharge) of adult patients.

Further research must generate a risk assessment model and other interventions to reduce psychological dysfunction and alleviate the intensity of risk factors among patients and their informal caregivers in the high-risk group. The prevalence of depression and PTSD among patients in the usual care group in our SR/MA was lower after 12 months from ICU discharge compared to patients in previous reviews (Parker et al., 2015; Rabiee et al., 2016). Furthermore, although the guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2009) suggested the need for risk assessment of psychological dysfunction among critically-ill patients, we find no risk assessment model suitable for psychological dysfunction. Previous studies showed that pain was associated with psychological dysfunction among patients in the ICU (Puntillo et al., 2018) and persisted after ICU discharge (Kemp et al., 2019); thus, pain could be one of the risk factors for psychological dysfunction. It is unclear whether follow-up would reduce pain or the risk (of psychological dysfunction) associated with factors like pain. Additionally, our eligible studies excluded patients with cognitive impairments due to the nature of the intervention. One cohort study reported that symptoms of PICS overlapped (Marra et al., 2018). Patients and their informal caregivers with cognitive impairments might not be able to find and avoid psychological intervention by themselves. Thus, in a future study, we should develop an effective intervention for participants with a high-risk of PICS.

Our SR/MA had several strengths. First, we searched databases like APA PsycInfo (Ovid), which covered the psychiatric domain, in addition to guidelines and citations via Google Scholar. Second, we conducted sensitivity and sub-analysis based on pre-registered protocols, yielding interesting findings. However, we could not verify the results for all primary outcomes owing to the small number of eligible studies. Third, several studies included in this SR/MA were well-designed except for the nature of the intervention. Finally, our definitions for the critical outcome measures were based on core outcomes among critically ill patients.

However, several limitations of our SR/MA need to be acknowledged. First, our search strategy involved using keywords for outcome measures instead of intervention strategies. Searches using outcome keywords might result in more favorable outcomes for intervention (Tsujimoto et al., 2021). Nevertheless, our SR/MA found negative results for the effectiveness of ICU follow-ups. Second, the attrition of participants in all eligible studies was higher than 20%. As participants who developed psychological dysfunction tended to withdraw from the studies, the compliance of participants with the needs of follow-ups decreased. Finally, there were several issues that require further investigation. Most reviewed studies did not report adverse events, which was a critical outcome measure for ICU survivors and their families. We could not verify the effective initiation, period, and type of intervention as they were outside the scope of our SR/MA. Similarly, the researchers’ experiences were unknown.

Conclusion

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis for ICU follow-ups initiated after ICU discharge, focusing on psychological intervention. We found that ICU follow-ups did not decrease the risk of psychological dysfunction and readmission among patients. The evidence of the effect of ICU follow-up on adverse events among patients was insufficient. Similarly, there was insufficient evidence for the effect of ICU follow-ups among informal caregivers. Future studies should focus on ICU follow-ups for high-risk patients and informal caregivers of surviving patients to monitor in order to prevent the development of psychological dysfunction.

Supplemental Information

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate Sara L. Douglas, Ronald L. Hickman Jr., Johan H. Vlake, V.R.M. Moulaert, Kimberley Haines, Konrad Schmidt, Nancy Kentish-Barnes, Christina Jones, and Janet F Jensen for providing additional information about their studies. We also appreciate Koichi Mino for providing information for this study. The authors greatly appreciate Editage for English language editing.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18K17719. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

Shunsuke Taito, Yusuke Tsutsumi, and Yuki Kataoka are affiliated Scientific Research WorkS Peer Support Group (SRWS-PSG), Osaka, JAPAN, which is an academic research group. Kota Yamauchi is employed by the Steel Memorial Yawata Hospital. Yuki Kataoka is employed by the Kyoto Min-iren Asukai Hospital. Yusuke Tsutsumi is employed by the National Hospital Organization Mito Medical Center. The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Shodai Yoshihiro conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Shunsuke Taito conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Kota Yamauchi conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Shunsuke Kina conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Takero Terayama conceived and designed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Yusuke Tsutsumi conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Yuki Kataoka conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Takeshi Unoki conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the article, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw measurements are available in the Supplemental Files.

References

- Ågren et al. (2019).Ågren S, Eriksson A, Fredrikson M, Hollman-Frisman G, Orwelius L. The health promoting conversations intervention for families with a critically ill relative: a pilot study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2019;50:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamid et al. (2021).Abdelhamid YAli, Phillips LK, White MG, Presneill J, Horowitz M, Deane AM. Survivors of intensive care with type 2 diabetes and the effect of shared-care follow-up clinics: the SWEET-AS Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Chest. 2021;159:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus & Carlet (2003).Angus DC, Carlet J. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Medicine. 2003;29:368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom et al. (2019).Bloom SL, Stollings JL, Kirkpatrick O, Wang L, Byrne DW, Sevin CM, Semler MW. Randomized clinical trial of an ICU recovery pilot program for survivors of critical illness. Critical Care Medicine. 2019;47:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohart et al. (2019).Bohart S, Egerod I, Bestle MH, Overgaard D, Christensen DF, Jensen JF. Reprint of Recovery programme for ICU survivors has no effect on relatives’ quality of life: secondary analysis of the RAPIT-study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2019;50:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandao Barreto et al. (2021).Brandao Barreto B, Luz M, Do Amaral Lopes SAV, Rosa RG, Gusmao-Flores D. Exploring family members’ and health care professionals’ perceptions on ICU diaries: a systematic review and qualitative data synthesis. Intensive Care Medicine. 2021;47:737–749. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06443-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen et al. (2022).Chen Y, Wang R, Yu J, Zhu L, Lu Y, Deng X. Effects of MBSR therapy on negative emotions, fatigue, and sleep quality in post-ICU patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial protocol. Medicine. 2022;101:e28331. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000028331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherak et al. (2021).Cherak SJ, Rosgen BK, Amarbayan M, Wollny K, Doig CJ, Patten SB, Stelfox HT, Fiest KM. Mental health interventions to improve psychological outcomes in informal caregivers of critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care Medicine. 2021;49:1414–1426. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000005011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox et al. (2018).Cox CE, Hough CL, Carson SS, White DB, Kahn JM, Olsen MK, Jones DM, Somers TJ, Kelleher SA, Porter LS. Effects of a telephone- and web-based coping skills training program compared with an education program for survivors of critical illness and their family members. A randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2018;197:66–78. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201704-0720OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox et al. (2019).Cox CE, Hough CL, Jones DM, Ungar A, Reagan W, Key MD, Gremore T, Olsen MK, Sanders L, Greeson JM, Porter LS. Effects of mindfulness training programmes delivered by a self-directed mobile app and by telephone compared with an education programme for survivors of critical illness: a pilot randomised clinical trial. Thorax. 2019;74:33–42. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson et al. (2009).Cuthbertson BH, Rattray J, Campbell MK, Gager M, Roughton S, Smith A, Hull A, Breeman S, Norrie J, Jenkinson D, Hernández R, Johnston M, Wilson E, Waldmann C. The PRaCTICaL study of nurse led, intensive care follow-up programmes for improving long term outcomes from critical illness: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The BMJ. 2009;339:b3723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly et al. (2005).Daly BJ, Douglas SL, Kelley CG, O’Toole E, Montenegro H. Trial of a disease management program to reduce hospital readmissions of the chronically critically ill. Chest. 2005;128:507–517. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeForge et al. (2022).DeForge CE, George M, Baldwin MR, South K, Beauchemin M, McHugh ME, Smaldone A. Do interventions improve symptoms among ICU surrogates facing end-of-life decisions? A prognostically-enriched systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care Medicine. 2022;50:e779-e790. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000005642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas et al. (2005).Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Kelley CG, O’Toole E, Montenegro H. Impact of a disease management program upon caregivers of chronically critically ill patients; A cost-effectiveness analysis of a health education programme for elderly persons with age-related macular degeneration: a longitudinal study. Chest. 2005;128(6):3925–3936. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas et al. (2007).Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Kelley CG, O’Toole E, Montenegro H. Chronically critically ill patients: health-related quality of life and resource use after a disease management intervention. American Journal of Critical Care. 2007;16:447–457. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2007.16.5.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettenberger et al. (2017).Ettenberger M, Rojas Cárdenas C, Parker M, Odell-Miller H. Family-centred music therapy with preterm infants and their parents in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) in Colombia—a mixed-methods study. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy. 2017;26:207–234. doi: 10.1080/08098131.2016.1205650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ewens et al. (2019).Ewens B, Myers H, Whitehead L, Seaman K, Sundin D, Hendricks J. A web-based recovery program (ICUTogether) for intensive care survivors: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols. 2019;8:e10935. doi: 10.2196/10935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotiou et al. (2016).Fotiou C, Vlastarakos PV, Bakoula C, Papagaroufalis K, Bakoyannis G, Darviri C, Chrousos G. Parental stress management using relaxation techniques in a neonatal intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2016;32:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman et al. (2022).Friedman D, Grimaldi L, Cariou A, Aegerter P, Gaudry S, Ben Salah A, Oueslati H, Megarbane B, Meunier-Beillard N, Quenot JP, Schwebel C, Jacob L, Robin Lagandré S, Kalfon P, Sonneville R, Siami S, Mazeraud A, Sharshar T. Impact of a Postintensive Care Unit Multidisciplinary Follow-up on the Quality of Life (SUIVI-REA): protocol for a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Research Protocols. 2022;11:e30496. doi: 10.2196/30496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawlytta et al. (2020).Gawlytta R, Kesselmeier M, Scherag A, Niemeyer H, Böttche M, Knaevelsrud C, Rosendahl J. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral writing therapy for reducing posttraumatic stress after severe sepsis in patients and their spouses (REPAIR): results of a randomized controlled trial. Reseach Square. 2020;12(3):e050305. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-74259/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawlytta et al. (2017).Gawlytta R, Niemeyer H, Böttche M, Scherag A, Knaevelsrud C, Rosendahl J. Internet-based cognitive-behavioural writing therapy for reducing post-traumatic stress after intensive care for sepsis in patients and their spouses (REPAIR): study protocol for a randomised-controlled trial. The BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014363. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines et al. (2019).Haines KJ, Holdsworth C, Cranwell K, Skinner EH, Holton S, MacLeod-Smith B, Bates S, Iwashyna TJ, French C, Booth S, Carmody J, Henningham L, Searle G, Shackell M, Maher L. Development of a peer support model using experience-based co-design to improve critical care recovery. Critical Care Explorations. 2019;1:e0006. doi: 10.1097/cce.0000000000000006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández et al. (2014).Hernández RA, Jenkinson D, Vale L, Cuthbertson BH. Economic evaluation of nurse-led intensive care follow-up programmes compared with standard care: the PRaCTICaL trial. The European Journal of Health Economics. 2014;15:243–252. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins et al. (2020).Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, LTC M, Page M, Welch V, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated 2020) 2020. [2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Hultcrantz et al. (2017).Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2017;87:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen et al. (2016).Jensen JF, Egerod I, Bestle MH, Christensen DF, Elklit A, Hansen RL, Knudsen H, Grode LB, Overgaard D. A recovery program to improve quality of life, sense of coherence and psychological health in ICU survivors: a multicenter randomized controlled trial, the RAPIT study. Intensive Care Medicine. 2016;42:1733–1743. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson et al. (2019).Johnson CC, Suchyta MR, Darowski ES, Collar EM, Kiehl AL, Van J, Jackson JC, Hopkins RO. Psychological sequelae in family caregivers of critically iii intensive care unit patients. A systematic review. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2019;16:894–909. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201808-540SR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones et al. (2003).Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, Humphris GH, Ingleby S, Eddleston J, Waldmann C, Gager M. Rehabilitation after critical illness: a randomized, controlled trial. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31:2456–2461. doi: 10.1097/01.Ccm.0000089938.56725.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones et al. (2004).Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, Humphris G, Ingleby S, Eddleston J, Waldmann C, Gager M. Post-traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive Care Medicine. 2004;30:456–460. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp et al. (2019).Kemp HI, Laycock H, Costello A, Brett SJ. Chronic pain in critical care survivors: a narrative review. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2019;123:e372-e384. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish-Barnes et al. (2017).Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Champigneulle B, Thirion M, Souppart V, Gilbert M, Lesieur O, Renault A, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Argaud L, Venot M, Demoule A, Guisset O, Vinatier I, Troché G, Massot J, Jaber S, Bornstain C, Gaday V, Robert R, Rigaud JP, Cinotti R, Adda M, Thomas F, Calvet L, Galon M, Cohen-Solal Z, Cariou A, Azoulay E. Effect of a condolence letter on grief symptoms among relatives of patients who died in the ICU: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Medicine. 2017;43:473–484. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4669-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan et al. (2018).Khan S, Biju A, Wang S, Gao S, Irfan O, Harrawood A, Martinez S, Brewer E, Perkins A, Unverzagt FW, Lasiter S, Zarzaur B, Rahman O, Boustani M, Khan B. Mobile critical care recovery program (m-CCRP) for acute respiratory failure survivors: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:94. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2449-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kredentser et al. (2018).Kredentser MS, Blouw M, Marten N, Sareen J, Bienvenu OJ, Ryu J, Beatie BE, Logsetty S, Graff LA, Eggertson S, Sweatman S, Debroni B, Cianflone N, Arora RC, Zarychanski R, Olafson K. Preventing posttraumatic stress in icu survivors: a single-center pilot randomized controlled trial of ICU diaries and psychoeducation. Critical Care Medicine. 2018;46:1914–1922. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major et al. (2016).Major ME, Kwakman R, Kho ME, Connolly B, McWilliams D, Denehy L, Hanekom S, Patman S, Gosselink R, Jones C, Nollet F, Needham DM, Engelbert RH, Schaaf Mvander. Surviving critical illness: what is next? An expert consensus statement on physical rehabilitation after hospital discharge. Critical Care. 2016;20:354. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1508-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra et al. (2018).Marra A, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Patel MB, Hughes CG, Jackson JC, Thompson JL, Chandrasekhar R, Ely EW, Brummel NE. Co-occurrence of post-intensive care syndrome problems among 406 survivors of critical illness. Critical Care Medicine. 2018;46:1393–1401. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall et al. (2018).Marshall IJ, Noel-Storr A, Kuiper J, Thomas J, Wallace BC. Machine learning for identifying randomized controlled trials: an evaluation and practitioner’s guide. Research Synthesis Methods. 2018;9:602–614. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, Benington & Atkinson (2016).McWilliams DJ, Benington S, Atkinson D. Outpatient-based physical rehabilitation for survivors of prolonged critical illness: a randomized controlled trial. Physiotherapy: Theory and Practice. 2016;32:179–190. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2015.1137663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mörelius et al. (2015).Mörelius E, Örtenstrand A, Theodorsson E, Frostell A. A randomised trial of continuous skin-to-skin contact after preterm birth and the effects on salivary cortisol, parental stress, depression, and breastfeeding. Early Human Development. 2015;91:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert et al. (2015).Moulaert VR, Van Heugten CM, Winkens B, Bakx WG, De Krom MC, Gorgels TP, Wade DT, Verbunt JA. Early neurologically-focused follow-up after cardiac arrest improves quality of life at one year: a randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Cardiology. 2015;193:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2009).National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Rehabilitation after critical illness in adults Clinical guideline [CG83] 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg83. [26 May 2021]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg83 [PubMed]

- Needham et al. (2012).Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, Zawistowski C, Bemis-Dougherty A, Berney SC, Bienvenu OJ, Brady SL, Brodsky MB, Denehy L, Elliott D, Flatley C, Harabin AL, Jones C, Louis D, Meltzer W, Muldoon SR, Palmer JB, Perme C, Robinson M, Schmidt DM, Scruth E, Spill GR, Storey CP, Render M, Votto J, Harvey MA. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Critical Care Medicine. 2012;40:502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham et al. (2017).Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Friedman LA, Bingham 3rd CO, Turnbull AE. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. An international modified delphi consensus study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2017;196:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikayin et al. (2016).Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, Huang M, Bienvenu OJ, Turnbull AE, Needham DM. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2016;43:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan et al. (2021).Nolan JP, Sandroni C, Böttiger BW, Cariou A, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Genbrugge C, Haywood K, Lilja G, Moulaert VRM, Nikolaou N, Olasveengen TM, Skrifvars MB, Taccone F, Soar J. European resuscitation council and european society of intensive care medicineicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Medicine. 2021;47:369–421. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06368-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda et al. (2021).Ojeda A, Calvo A, Cuñat T, Artigas RM, Comino-Trinidad O, Aliaga J, Arias M, Ahuir M, Ferrando C, Dürsteler C. Rationale and study design of an early care, therapeutic education, and psychological intervention program for the management of post-intensive care syndrome and chronic pain after COVID-19 infection (PAIN-COVID): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22:486. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05463-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page et al. (2021).Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker et al. (2015).Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Critical Care Medicine. 2015;43:1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puntillo et al. (2018).Puntillo KA, Max A, Timsit JF, Ruckly S, Chanques G, Robleda G, Roche-Campo F, Mancebo J, Divatia JV, Soares M, Ionescu DC, Grintescu IM, Maggiore SM, Rusinova K, Owczuk R, Egerod I, Papathanassoglou EDE, Kyranou M, Joynt GM, Burghi G, Freebairn RC, Ho KM, Kaarlola A, Gerritsen RT, Kesecioglu J, Sulaj MMS, Norrenberg M, Benoit DD, Seha MSG, Hennein A, Pereira FJ, Benbenishty JS, Abroug F, Aquilina A, Monte JRC, An Y, Azoulay E. Pain distress: the negative emotion associated with procedures in ICU patients. Intensive Care Medicine. 2018;44:1493–1501. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiee et al. (2016).Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, Huang M, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, Turnbull AE, Needham DM. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care Medicine. 2016;44:1744–1753. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000001811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr et al. (2021).Rohr M, Brandstetter S, Bernardi C, Fisser C, Drewitz KP, Brunnthaler V, Schmidt K, Malfertheiner MV, Apfelbacher CJ. Piloting an ICU follow-up clinic to improve health-related quality of life in ICU survivors after a prolonged intensive care stay (PINA): study protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2021;7:90. doi: 10.1186/s40814-021-00796-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa et al. (2019).Rosa RG, Ferreira GE, Viola TW, Robinson CC, Kochhann R, Berto PP, Biason L, Cardoso PR, Falavigna M, Teixeira C. Effects of post-ICU follow-up on subject outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Critical Care. 2019;52:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt et al. (2020).Schmidt KF, Schwarzkopf D, Baldwin LM, Brunkhorst FM, Freytag A, Heintze C, Reinhart K, Schneider N, Von Korff M, Worrack S, Wensing M, Gensichen J. Long-term courses of sepsis survivors: effects of a primary care management intervention. The American Journal of Medicine. 2020;133:381–385.e385. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt et al. (2016).Schmidt K, Worrack S, Korff MVon, Davydow D, Brunkhorst F, Ehlert U, Pausch C, Mehlhorn J, Schneider N, Scherag A, Freytag A, Reinhart K, Wensing M, Gensichen J. Effect of a primary care management intervention on mental health-related quality of life among survivors of sepsis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2703–2711. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield-Robinson et al. (2018).Schofield-Robinson OJ, Lewis SR, Smith AF, McPeake J, Alderson P. Follow-up services for improving long-term outcomes in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;11:Cd012701. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012701.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne et al. (2019).Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. The BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/TheBMJ.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto et al. (2021).Tsujimoto Y, Tsutsumi Y, Kataoka Y, Banno M, Furukawa TA. Around ten percent of most recent Cochrane reviews included outcomes in their literature search strategy and were associated with potentially exaggerated results: a research-on-research study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2021;141:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsøet al. (2020).Valsø Å, Rustøen T, Småstuen MC, Ekeberg Ø, Skogstad L, Schou-Bredal I, Myhren H, Sunde K, Tøien K. Effect of nurse-led consultations on post-traumatic stress and sense of coherence in discharged icu patients with clinically relevant post-traumatic stress symptoms—a randomized controlled trial. Critical Care Medicine. 2020;48:e1218-e1225. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000004628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlake et al. (2021).Vlake JH, Van Bommel J, Wils EJ, Korevaar TIM, Bienvenu OJ, Klijn E, Gommers D, Van Genderen ME. Virtual reality to improve sequelae of the postintensive care syndrome: a multicenter, randomized controlled feasibility study. Critical Care Explorations. 2021;3:e0538. doi: 10.1097/cce.0000000000000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihiro et al. (2021).Yoshihiro S, Taito S, Yamauchi K, Kina S, Terayama T, Tsutsumi Y, Kataoka Y, Unoki T. Efficacy of follow-up after intensive care unit (ICU) discharge for improving long-term outcomes and mental health in ICU patients and informal caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. https://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bvjwn4pe. [8 June 2021];2021 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw measurements are available in the Supplemental Files.