Abstract

Introduction

Malaria is a devastating infectious illness caused by protozoan Plasmodium parasites. The circumsporozoite protein (CSP) on Plasmodium sporozoites binds heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) receptors for liver invasion, a critical step for prophylactic and therapeutic interventions.

Methods

In this study, we characterized the αTSR domain that covers region III and the thrombospondin type-I repeat (TSR) of the CSP using various biochemical, glycobiological, bioengineering, and immunological approaches.

Results

We found for the first time that the αTSR bound heparan sulfate (HS) glycans through support by a fused protein, indicating that the αTSR is a key functional domain and thus a vaccine target. When the αTSR was fused to the S domain of norovirus VP1, the fusion protein self-assembled into uniform S60-αTSR nanoparticles. Three-dimensional structure reconstruction revealed that each nanoparticle consists of an S60 nanoparticle core and 60 surface displayed αTSR antigens. The nanoparticle displayed αTSRs retained the binding function to HS glycans, indicating that they maintained authentic conformations. Both tagged and tag-free S60-αTSR nanoparticles were produced via the Escherichia coli system at high yield by scalable approaches. They are highly immunogenic in mice, eliciting high titers of αTSR-specific antibody that bound specifically to the CSPs of Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites at high titer.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our data demonstrated that the αTSR is an important functional domain of the CSP. The S60-αTSR nanoparticle displaying multiple αTSR antigens is a promising vaccine candidate potentially against attachment and infection of Plasmodium parasites.

Keywords: malaria, Plasmodium, αTSR domain, receptor binding domain, S60 nanoparticle, malaria vaccine, norovirus

Introduction

Malaria is a deadly, transmissible human disease caused by unicellular protozoan parasites that are members of the Plasmodium genus in the family Plasmodiidae. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that about 40% of the global population is at risk of Plasmodium infection and that Plasmodium infection resulted in approximately 241 million malaria cases in 2020, claiming around 627,000 lives worldwide.1 Thus, malaria remains a major threat to global public health. Various countermeasures have been attempted to prevent malaria, including control of mosquito vectors carrying Plasmodium parasites, generations of antimalarial drugs, and development of vaccines.2 However, due to the resistance against insecticide by mosquitos and the diminished effects of antimalarial medicines owing to the resistance developed by the Plasmodiidae parasites, current efforts focus on vaccine development,3,4 mostly targeting Plasmodium sporozoites that occur in the early stage of human infection.5,6

Plasmodium protozoans that infect humans exhibit a common life cycle with an early development stage in the liver, followed by further proliferation in host bloods. During a mosquito bite by an infected female anopheline mosquito, Plasmodium sporozoites are transmitted from the mosquito into the dermis of a human host. The sporozoites then make their way into the liver via the bloodstream and invade hepatocytes, where they undergo proliferation known as schizogony, resulting in merozoites.3,7 The merozoites are released back into the bloodstream to invade erythrocytes where the merozoites proliferate asexually.8,9 Some merozoites differentiate into gametocytes, which is the end stage of the parasites’ life cycle in humans.10,11 This asexual blood stage involves fast and iterative invasion of erythrocytes, leading to symptoms of malaria disease. Development beyond the gametocyte stage occurs in mosquito, where the male and the female gametes fuse for sexual reproduction.12

Sporozoites appear in the first stage of human infection, representing a bottleneck in the Plasmodium life cycle, as only 10 to 100 sporozoites are transmitted during a mosquito bite13 and they are exposed to host antibodies before they invade the liver.14 In addition, since the sporozoites occur before the symptomatic stage, they are ideal targets for antimalarial drugs and vaccines. The sporozoites are coated densely and homogeneously with circumsporozoite proteins (CSPs)15 with multiple functions. The CSP is 414 amino acids in length, consisting of an N-terminal domain, region I with a protease cleavage site, a repeat region, region III with conserved sequences, a region II plus that is homologous with the thrombospondin type-1 repeat (TSR) superfamily, and a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor site at the C terminus.16 CSPs are associated with the plasma membrane via the GPI anchors.17

The CSP is essential for sporozoite development, including host cell targeting and invasion. It interacts with heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) as receptors for sporozoites to be arrested in the liver, facilitating liver infection,15,18–20 likely using the TSR (region II plus) as the HSPG-binding domain,20–23 although contradictory data were reported.16,24 The CSP is an immunodominant, protective antigen.25 Immunization with irradiated sporozoites resulted in strong protection against malaria infection in rodents,26 monkeys,27 and humans28 by eliciting CSP-specific antibodies that inhibited sporozoite infectivity. Irradiated sporozoites also elicited T cell responses that destroy the exo-erythrocytic forms of the parasites, including sporozoites.29 In addition, polymorphic T-cell epitopes were mapped to the TSR region, such as CS.T3 that induces a CD4+ T-cell response correlated with protection.30 Thus, the CSP and TSR are excellent vaccine targets.

Among the malaria vaccine candidates tested to date, the most clinically advanced one is RTS, S/AS01 (Mosquirix) that was developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).5,6 This vaccine contains the tandem repeats, region III, and TSR of P. falciparum CSP that are fused with the hepatitis B surface antigen that can self-assemble into virus-like particles (VLPs),5,6 although the morphology or structure of the resulted vaccine candidates have not been reported. In a Phase III clinical study, RTS S/AS01 vaccine revealed an average efficacy of about 39% against clinical malaria in children aged 5–17 months over a 4-year period, which, however, diminished over time.5,6,31,32 The continued absence of an effective malaria vaccine indicates an urgent need of an immunoprophylactic approach with improved efficacy and long-lasting immunity.

In this study, we first provided evidence that the αTSR domain covering CSP region III and TSR16 binds heparan sulfate (HS) after fusion with GST protein, showing it as an important functional domain and a vaccine target. We then took advantage of our S60 protein nanoparticle platform33–35 to display the αTSR antigens of P. falciparum CSP for improved immunogenicity as a vaccine candidate. The P. falciparum αTSR is selected, because its crystal structure is known16 and P. falciparum is the most prevalent and most deadly species of Plasmodium parasites.2,36 The resulted S60-αTSR nanoparticle was produced, bound HS glycan receptors, structurally elucidated, and is highly immunogenic, eliciting high αTSR-specific antibody titers in mice. The αTSR-specific antibody bound the CSPs of P. falciparum sporozoites at high titer, which could potentially block the receptor-binding function of CSPs. Thus, the S60-αTSR nanoparticle may be a promising malaria vaccine candidate.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids for αTSR-Hisx6 and GST-αTSR Protein Expressions

A DNA fragment encoding the αTSR domain16 of P. falciparum 3D7 strain (GenBank AC#: CAB38998.2, from E309 to C375, 67 residues) was codon-optimized to Escherichia coli (E. coli) and synthesized via GenScript (Piscataway). This DNA fragment was cloned into the pET-24b vector (Novagen) for expression of αTSR-Hisx6 protein (Figure 1A, top panel). The DNA fragment was also cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 vector (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) for production of GST (glutathione s-transferase)-tagged αTSR (GST-αTSR) protein (Figure 1A, middle panel). In addition, GST was also expressed using the pGEX-4T-1 plasmid alone (Figure 1A, bottom panel).

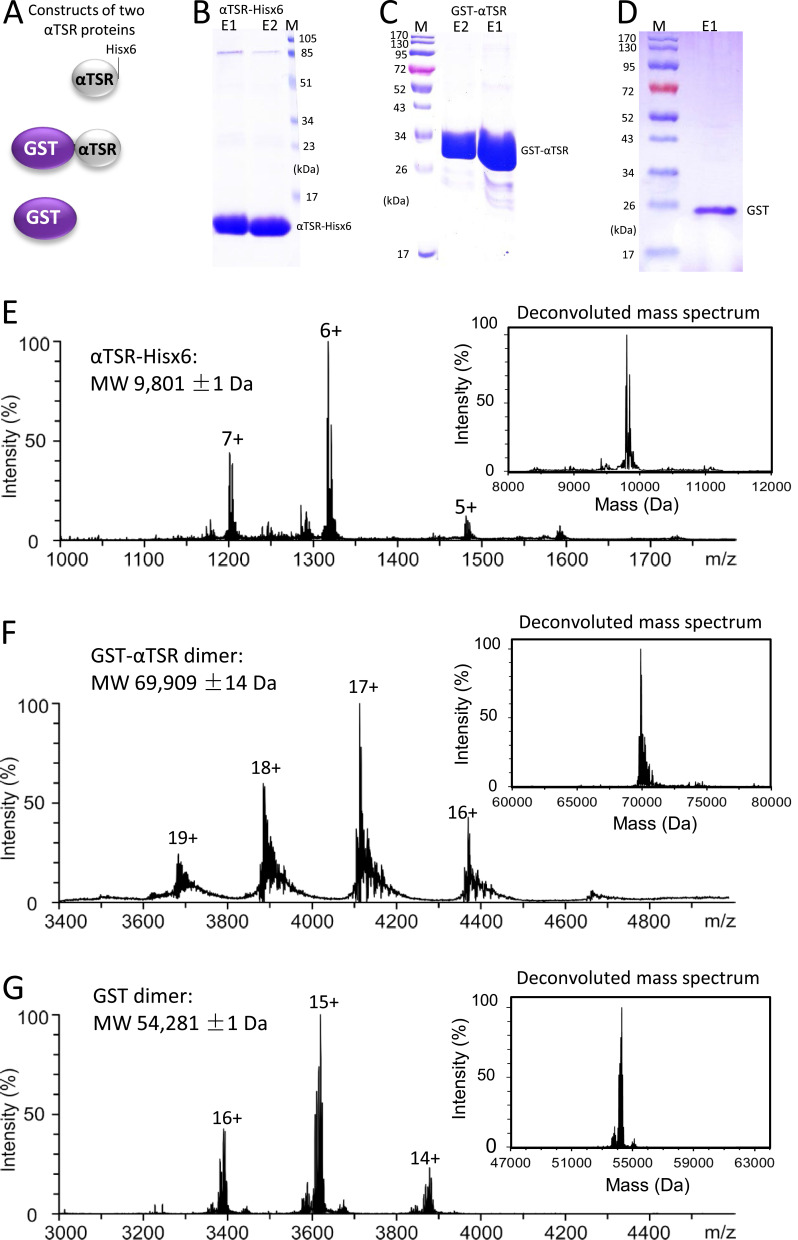

Figure 1.

Generation and characterization of two αTSR proteins. (A) Schematic constructs of the αTSR-Hisx6 (top panel), the GST-αTSR (middle panel), and the GST (bottom panel) proteins. (B–D) SDS-PAGE showing the purified αTSR-Hisx6 protein at ~10 kDa (B), the GST-αTSR protein at ~35 kDa (C), and the GST at ~26 kDa (D), respectively. Lanes E1 and/or E2 are elution fractions from the purification resin. M is protein markers with indicated molecular weights. 16% gel was used in (B), whereas 10% gels were used for (C and D). (E–G) Molecular weight (MW) determinations of the αTSR-Hisx6 (E), GST-αTSR (F), and GST proteins by electrospray ionization (ESI) and corresponding deconvoluted (insets) mass spectra, revealing 9801 Da, and 69,909 Da, and 54,281 Da, respectively.

DNA Construct for S-αTSR Protein Production

The DNA fragment encoding the αTSR antigen was cloned into the previously generated, pET-24b-based plasmid for production of the SR69A-VP8* fusion protein that self-assembles into the S60-VP8* nanoparticle,34 in which the VP8*-encoding sequences were replaced with the αTSR encoding DNA fragment. The resulting new plasmid expresses a Hisx6-tagged S-αTSR fusion protein. This new pET-24b-based plasmid was also modified to express a tag-free S-αTSR fusion protein by inserting a stop codon in front of the Hisx6-encoding sequences.

Recombinant Protein Production and Purification

Recombinant proteins were expressed using the E. coli (BL21, Arctic strain) system after induction by 0.25 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 13°C overnight as described elsewhere.34,37,38 Soluble Hisx6-tagged proteins were purified using the Cobalt resins (Thermo Fisher Scientific), while GST and GST-tagged protein were isolated using the Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow medium (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) according to the instructions of the manufacturers. The tag-free S-αTSR protein was purified by a two-step procedure, including a precipitation of the target protein from the bacteria lysate using ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4], and an ion exchange chromatography (see below).35 (NH4)2SO4 at 1.6 M end concentration was used to effectively precipitate the tag-free S-αTSR protein at room temperature (20–22°C).

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

Purified recombinant proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 10% separating gels, except for the small αTSR-Hisx6 protein (~9.8 kDa) that needed a 16% separating gel. The gels were stained using commercial Coomassie Stain (Bio-Rad) as instructed by the manufacturer.

Gel Filtration Chromatography

Gel filtration was performed as described previously37–39 using an ÄKTATM Fast Performance Liquid Chromatography system (FPLC, ÄKTATM pure 25L, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using a size exclusion column (Superdex 200, 10/300 GL, GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The size exclusion column was calibrated using gel filtration calibration kits (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), whereas the elution peaks of the proteins were defined using the formerly prepared S60-VP8* nanoparticle (~3.4 mDa) [33] and GST-dimer (~52 kDa). Relative protein concentrations in the effluents were shown by absorbance at A280.

Anion Exchange Chromatography

This was conducted to purify the tag-free S-αTSR protein as described previously.35,40 Briefly, the ÄKTA FPLC system equipped with a HiPrep Q HP 16/10 column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) was used. First, the column was equilibrated with 7 column volumes (CVs) of 20 mM tris buffer (pH 8.0, buffer A). After sample load, the column was washed by 7 CVs of buffer A, followed by elution of bound proteins by 8 CVs of buffer B (1 M NaCl in buffer A) via a linear gradient from 0% to 100%. Proteins in the effluent were indicated as UV absorbance at A280, while the elution positions of the proteins were reported by percentages of buffer B.

CsCl Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation

This method was used to determine the density of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle as described previously.34 Briefly, 0.5 mL of the resin purified S-αTSR protein was blended with 10 mL of CsCl solution with a density of 1.3630 g/mL. After centrifugation for 45 hours at 288,000 x g using the Optima L-90K ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter), the CsCl gradient was fractionated by bottom puncture into 22 fractions (~0.5 mL each). After 200-fold dilution in PBS, the S-αTSR protein in fractions was detected by EIA (see below) using antibody against norovirus VLPs.41 The CsCl densities of fractions were determined based on the refractive index.

Negative Stain Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

After staining with 1% ammonium molybdate, the purified S-αTSR nanoparticles were inspected using an EM10 C2 microscope (Zeiss, Germany) at 80 kV at magnifications between 15,000x to 30,000x as described previously.34

Image Processing and Modelling

Acquired micrographs of negatively stained S60-αTSR nanoparticles were initially processed in RELION v4.0.42 A total of 874 particles were selected using the particle autopicking tool in RELION. After 2 rounds of reference-free 2D classification, a total of 689 particles remained after removing junk particles. The particle stack was split into even and odd numbered half datasets. JSPR43,44 was then used to reconstruct 5 independent initial models using a random subset of 200 particles at each iteration from each half dataset for 8 iterations. All particles for each half dataset were globally searched and further refined against the initial models. The resulting orientation parameters of each particle were compared and those with the most stable orientations were kept using the calcImageParamVariance.py script from the JSPR software package. The final density map was produced after 2 additional iterations of refinement of the most stable particles. Fitting of the density map was performed through UCSF Chimera software45 using the S60 nanoparticle cryo-EM structure of norovirus (strain VA387) S domain (residue 46 to 218) and the crystal structure of the αTSR monomer of P. falciparum (PDB code: 3VDJ).16 The crystal structures of the inner shell of the 60-valent feline calicivirus (FCV) VLP (PDB code: 4PB6)46 was used to show the exposed C-terminal ends of the S domain.

Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA)-Based Glycan Binding Assay

EIA assays were utilized to determine interaction between the αTSR domains and HS glycans. Heparin sodium salt from porcine intestinal mucosa (Sigma-Aldrich) at 25 µg/mL was coated on 96-well microtiter plates (Thermo Scientific) at 4°C overnight. After blocking with 5% (w/v) skim milk, the plates were incubated with serially diluted αTSR-Hisx6, GST-αTSR, or S60-αTSR proteins. The bound proteins were detected using three different antibodies: 1) our in house made mouse sera after immunization with S60-αTSR (1:2000 dilution) for detections of the αTSR-Hisx6 and the GST-αTSR proteins, 2) rabbit antibody against norovirus VLP41 (1:3000 dilution) for detection of the S60 protein, or 3) rabbit antibody against GST for detection of the GST protein. The bound antibody was measured by corresponding horse-radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse or rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 1:5000 dilution. The signal intensity was shown by optical density at wavelength 450 nm after incubated with the HRP substrates as described previously.35

Mass Spectrometry

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was carried out in positive ion mode using a Q Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with the Nanospray FlexTM ion source. The nanoflow ESI (nanoESI) was performed using tips pulled from a borosilicate capillary (1.0 mm o.d., 0.75 mm i.d.) by a micropipette puller (P-1000, Sutter Instruments). A voltage of 0.9 kV was applied to a platinum wire inserted into the nanoESI tip and in contact with the sample solution. The capillary temperature 160°C, maximum inject time 200 ms, microscans 10, S-lens RF level 100, and resolution 17,000 were applied, whereas other instrument parameters were set at default values. Data acquisition and processing were performed using Xcalibur (Thermo Fisher Scientific, version 4.4).

Deconvolution of ESI Mass Spectra

Deconvolution of the ESI mass spectra was performed using UniDec software (version 3.2.0)47 to determine the molecular weights of the GST-αTSR, αTSR-Hisx6, and GST proteins. The following parameters were used: m/z range 2000–5000 (for GST-αTSR and GST), and 1000–3000 (for αTSR); bin every 0.5 (ie, the raw MS data points were resampled at every 0.5 m/z to UniDec); charge range 5–20; mass range 60,000–80,000 for GST-αTSR, 46,000–64,000 for GST, and 8000–12,000 for αTSR-Hisx6; sample mass every 1.0 Da; Peak FWHM (Th) 1.0; peak shape function Gaussian; and maximum number of iterations 100. A full description of the UniDec deconvolution parameters can be found from the User Manual at http://unidec.chem.ox.ac.uk/.

ESI-MS Binding Measurements

The affinities for the interactions between the two αTSR proteins (GST-αTSR and αTSR-Hisx6) or GST and the glycans in our HS library were quantified using ESI-MS binding assay. The measurements were performed in 200 mM aqueous ammonium acetate solution (pH 6.8, 25°C), whereby each protein was incubated with each ligand (separately) for 10 min and then subjected to ESI-MS analysis. The apparent (ie, macroscopic) dissociation constant (KD) was calculated (Equation 1), from the total abundance (Ab) ratio (R, Equation 2) of the ligand-bound (PL)-to-free protein (P) ions and the initial concentrations of P ([P]0) and ligand ([L]0):

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

In all cases, a single chain fragment (scFv, MW 26,539 Da) of the monoclonal antibody Se155-4, served as the reference protein (Pref) to correct for any nonspecific binding during the nanoESI process. A detailed description of the method can be found elsewhere.48 The reported affinities are average values from replicate measurements performed at a minimum of three different L concentrations.

Mass Photometry

Mass photometry was carried out with a OneMP mass photometer (Refeyn Ltd, Oxford, UK) to determine the molecular weights of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle. Briefly, the microscope coverslips (Thorlabs Inc) were pre-cleaned with isopropanol (LC-MS grade) and Milli-Q H2O, followed by drying with a clean nitrogen stream. Clean coverslips were assembled for sample delivery using silicone CultureWellTM gaskets (Grace Bio-Labs, OR). For each acquisition, 15 µL of sample diluted in 200 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.8, 25°C) was introduced into a gasket. Following autofocus stabilization, a movie of 60s duration was recorded at 1 kHz, with exposure times varying between 0.6 ms and 0.9 ms. Each sample was measured at least three times independently. Data acquisition was performed using AcquireMP (Refeyn Ltd, version 2.5). The data were analyzed with DiscoverMP (Refeyn Ltd, version 2.5), which detects the events of proteins in the solution landing onto the glass coverslip surface and determines the respective interferometric scattering contrasts. The mean peak contrast of each sample solution was determined using Gaussian fitting, and converted to the mass value through contrast comparison with known mass standard calibrants (ie, contrast-to-mass calibration). The calibration curve was performed daily, including measuring bovine serum albumin (66, 132, 198 kDa), thyroglobulin (660 kDa) and apoferritin (480 and 960 kDa). The detailed description of the principles and data analysis method for the mass photometry can be found elsewhere.49

HS Glycan Library

The 15 HS compounds in the HS glycan library, including HS DP2, HS DP4, HS DP6, HS15 to HS20, and HS22 to HS27 (see Figure 2, were provided by Prof. Geert-Jan Boons at Utrecht University and University of Georgia.

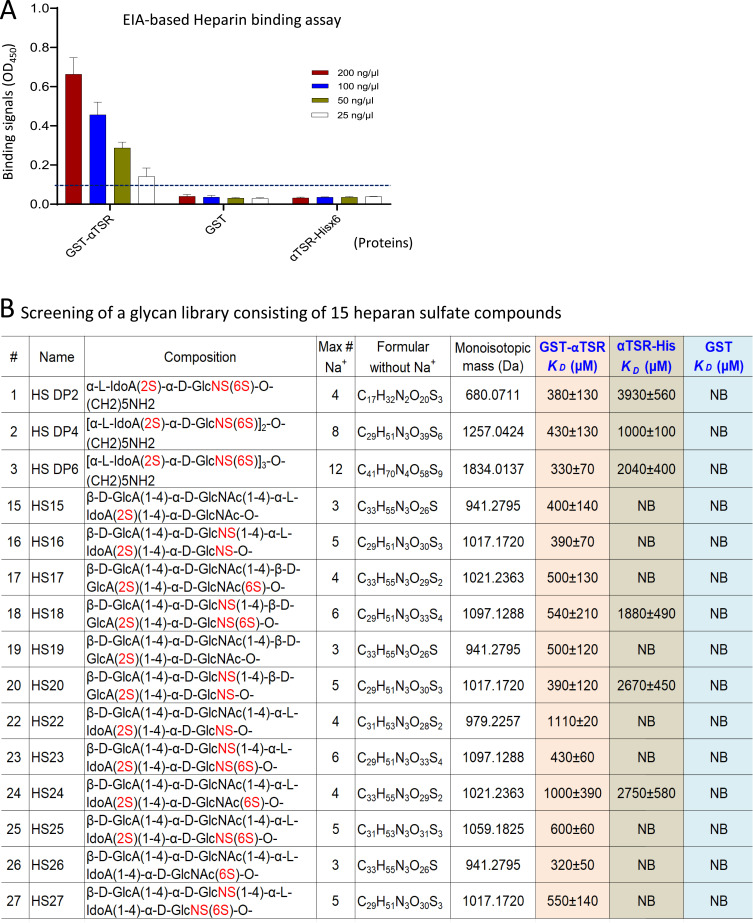

Figure 2.

Binding of the αTSR proteins to heparan sulfate (HS) glycans. (A) Binding of the αTSR containing proteins to heparin sodium salt by EIA based binding assays. Y-axis shows binding signals in optical density (OD450), while X-axis denotes the proteins at indicated concentrations: red columns, 200 ng/µL; blue columns, 100 ng/µL; brown columns, 50 ng/µL; and while columns, 250 ng/µL. The cutoff signal value (OD450=0.1) is shown by a dashed line. (B) Screening of a HS glycan library consisting of 15 HS glycans using the αTSR-Hisx6, the GST-αTSR, and GST (indicated by blue fonts) as probes, respectively, through electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). The order (#), name, composition, maximum number of sodium (Max # Na+), formula without sodium (Na+), and monoisotopic mass (Da) of each HS glycan, as well as their binding affinities in dissociation constants (KD, µM) to each of the GST-αTSR, the αTSR-Hisx6, or GST protein are shown. In the composition column, the numbers of sulfates are shown in red fonts. The KD is an average value (µM) ± standard deviation. NB ≡ no binding.

Immunization of Mice

Pathogen free BALB/c mice at age ~6 weeks from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar harbor, ME) were maintained at the Division of Veterinary Services of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Mice were divided randomly into four groups with 6 to 8 mice per group (n = 6–8) and the grouped mice were immunized with one of the following reagents: 1) S60-αTSR nanoparticle (S60-αTSR); 2) GST-αTSR fusion protein (GST-TSR); 3) αTSR-Hisx6 protein (TSR-Hisx6); and 4) S60 nanoparticle without the αTSR antigens (S60). Immunogens that contained Alum adjuvant (Imject Alum, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 25 μL/dose (20 μg/mouse/dose) were administered intramuscularly (IM) in the thigh muscle three times with 50 μL injection volume at 2-week intervals. Blood samples were collected two weeks after the second immunization through the tail vein and two weeks after the final vaccination via heart puncture and sera were processed via an established protocol.50

EIAs for αTSR-Specific IgG Titer Determination

EIAs were applied to define αTSR specific IgG antibody titers as described previously.51,52 Briefly, gel-filtration purified GST-αTSR (for S60-αTSR, αTSR-Hisx6, or S60 protein immunized mouse sera) or αTSR-Hisx6 (for GST-αTSR protein immunized mouse sera) proteins at 5 µg/mL were coated to plates as capture antigens. After blocked with nonfat milk, plates were incubated with serially diluted mouse sera. The bound IgG was detected by goat-anti-mouse IgG-HRP conjugate (1:5000, MP Biomedicals). The αTSR-specific antibody titers were defined as maximum dilutions of sera with positive signals (OD450 ≥ 0.2).

Immunofluorescence Assays (IFAs)

Air dried P. falciparum sporozoites were stained using the mouse sera after immunization of the αTSR containing proteins as described previously.53,54 Briefly, sporozoites of P. falciparum from mosquito salivary glands on slides (kindly provided by Dr. Photini Sinnis at Johns Hopkins University) were warmed to ambient temperature. After blocked with 1% BSA in 1x TBS (pH 7.4), the slide was incubated with 2-fold serially (2000x to 256,000x) diluted mouse sera after immunization of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle or the αTSR-Hisx6 protein (see above) in a humid chamber. After washing, fluorophore–conjugated secondary antibody (Millipore-Sigma) was added. The slide was washed and mounted using Citifluor Mountant Media by placing a cover glass on the slide and seal with nail polish. The slide was viewed with fluorescence microscope at 20x to 40x magnifications. Stain titers were defined as the maximum dilutions of the mouse sera that showed recognizable staining of Plasmodium sporozoites.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences between two data groups were calculated by GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) using unpaired t test. Differences were considered non-significant when P-values are >0.05 (marked as “ns”), significant when P-values are <0.05 (marked as “*”), highly significant when P-values are <0.01 (marked as “**”), and extremely significant when P-values are <0.001 (marked as “***”), respectively.

Ethics Statement

All animal studies were completed in compliance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (23a) of the National Institute of Health (NIH). The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation (Animal Welfare Assurance No. A3108-01). No human subjects were involved in this study.

Results

Generation and Characterization of the αTSR-Hisx6 and GST-αTSR Proteins

After expression in E. coli, soluble αTSR-Hisx6 protein in the bacteria lysate was purified using the Cobalt resin at a yield of ~15 mg/L bacteria culture. SDS-PAGE using a 16% gel showed the protein band at ~10 kDa (Figure 1B). Similarly, soluble GST-αTSR protein was isolated using the Glutathione Sepharose 4 Fast Flow medium (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) at a yield of ~40 mg/L bacteria culture. SDS-PAGE revealed the GST-αTSR protein at ~35 kDa (Figure 1C). Soluble GST with a ~26 kDa was also produced as a control (Figure 1D). The purified proteins were further analyzed by MS, revealing a molecular weight of 9801 Da for the αTSR-Hisx6 protein (Figure 1E) as monomers, 69,909 Da for the GST-αTSR protein (Figure 1F) as dimers, and 54,281 Da for GST protein (Figure 1G) as dimers.

Binding of the αTSR Fusion Proteins to HS Glycans

The CSP is known to interact with HSPGs as receptors to facilitate Plasmodium infection in the liver,15,18–20 likely using the αTSR region as the HSPG binding domain,20–23 although this has been contradicted in some studies.16,24 To clarify this issue, the two αTSR proteins generated above were tested for their binding to heparin glycans by EIA-based binding assays. The results (Figure 2A) showed that the GST-αTSR fusion proteins bound well heparin, but the αTSR-Hisx6 did not bind. As negative controls, both GST without the αTSR domain did not bind heparin (Figure 2A), indicating the binding signals were from the αTSR protein. It was noted that the αTSR-Hisx6 protein did not bind heparin, consistent with a previous observation.16

To further verify these observations, the GST-αTSR, αTSR-Hisx6, and GST proteins were used as probes to screen a HS glycan library consisting of 15 HS compounds, respectively, by highly sensitive ESI-MS binding assays. The results (Figure 2B) demonstrated that the GST-αTSR bound all 15 HS glycans in the library, revealing dissociation constants (KD values) in the µM range to 13 HS glycans (Figure 2B, GST-αTSR column), which are in typical affinity range for protein–glycan interactions. Noteworthy, the αTSR-Hisx6 protein also bound weakly six HS glycans with KD values in mM range between 1.0 and 3.9 mM (Figure 2B, αTSR-His column) which were substantially higher than those of the GST-αTSR protein. The remaining nine glycans in the library did not reveal detectable binding to the αTSR-Hisx6 protein. As the negative control, GST did not bound any of the 15 HS compounds (Figure 2B, GST column). While the screening data verified the EIA-based binding results, they also showed that αTSR-Hisx6 protein bound some HS glycans with low affinity. These data strongly suggested that, as part of the CSP, the αTSR may need a fused protein as a foundation to support its proper conformations for high binding affinity to HS glycans, a scenario resembling the VP8* domain of rotavirus VP4 in binding to its glycan receptors55–58 (see discussion).

Production of the S60-αTSR Nanoparticle

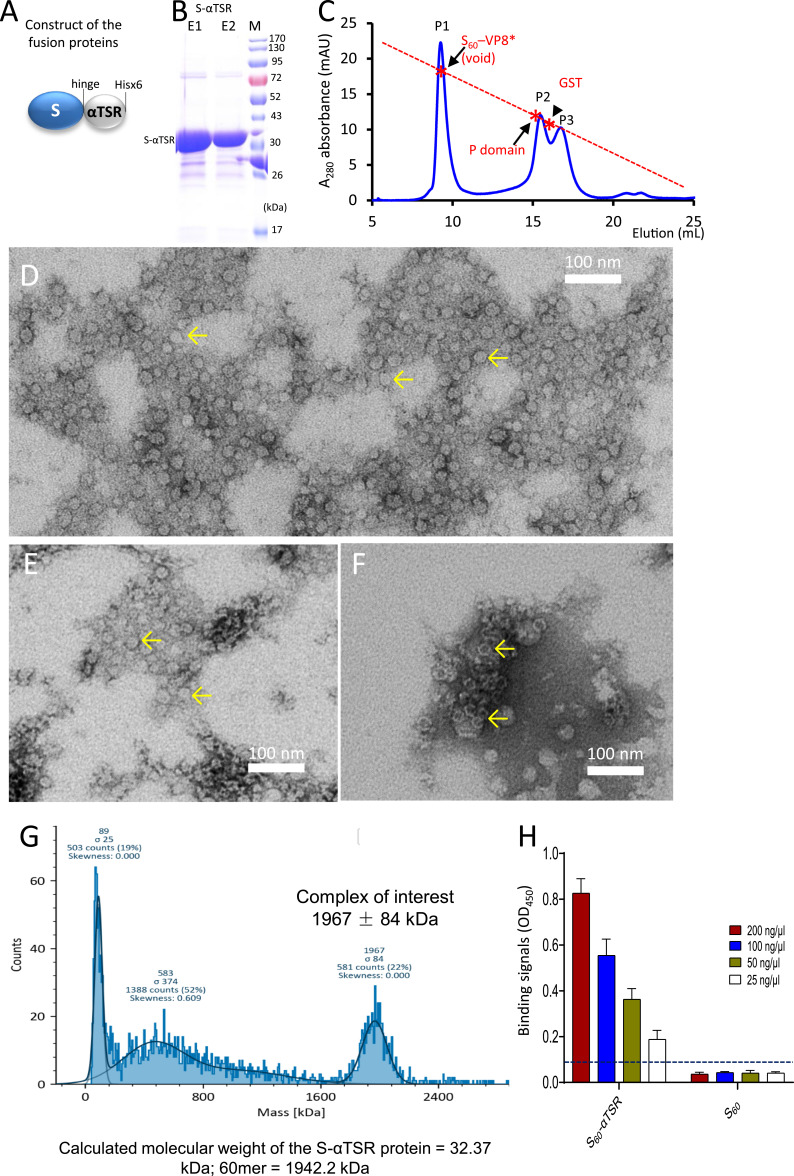

Soluble S-αTSR protein with a C-terminal Hisx6 tag (Figure 3A) was produced via the E. coli system at yields of ~20 mg/L bacterial culture using the Cobalt resin. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed the target protein at expected ~35 kDa (Figure 3B). Gel-filtration chromatography of the protein showed a major (P1) and two minor (P2 and P3) elution peaks (Figure 3C). The major peak (P1) at high molecular weights represented the self-assembled S60-αTSR nanoparticle (see below), while the minor P2 and P3 were at similar positions like the previously observed S-VP8* dimer and S-VP8* monomer,34 suggesting that they were the S-αTSR dimers and monomers, respectively. Negative stain TEM inspection of the P1 sample showed nanoparticles at ~25 nm in diameter (Figure 3D), confirming that most S-αTSR protein self-assembled into S60-αTSR nanoparticle. Interestingly, TEM examination of the P2 and P3 samples also revealed similar nanoparticles (Figure 3E and F) at less numbers compared with that of the P1. This observation suggested that the nanoparticle assembly may be dynamic, in which the S-αTSR dimers and monomers can further assemble into S60-αTSR nanoparticles.

Figure 3.

Production of the S60-αTSR nanoparticles. (A) Schematic construct of the S-αTSR fusion protein with a C-terminal Hisx6 tag. S, modified norovirus S domain; hinge, the hinge region of norovirus VP1. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of the resin purified S-αTSR fusion protein showing a band at ~32 kDa. M, protein standards with indicated molecular sizes. (C) A gel-filtration elution curve of the S-αTSR protein through a size exclusion column, showing a major peak (P1, void volume) representing the S60-αTSR nanoparticle and two minor peaks (P2 and P3) representing the dimers and monomers of the S-αTSR protein. The elution peaks were calibrated using the S60-VP8* nanoparticle (~3.4 mDa) [20], norovirus P dimer (~69 kDa),38 and GST dimers (54 kDa) with their elution positions being shown by star symbols and arrows on a red dashed line. Y-axis shows UV absorbances at A280 (mAU), while X-axis indicates elusion volume (mL). (D–F) Micrographs of transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of protein samples from the P1, P2, and P3, respectively, showing typical S60-αTSR nanoparticles (arrows). (G) Molecular weight determinations of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle by mass photometry. The complex of interest showed a molecular weight of 1967 ± 84 kDa, matching well with calculated molecular weight (1942.2 kDa) of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle. (H) Binding of the S60-αTSR proteins to heparin sodium salt by EIA based binding assays. Y-axis shows binding signals in optical density (OD450), while X-axis denotes the S60-αTSR proteins and its control proteins without the αTSR domain at indicated concentrations. The cutoff signal value (OD450=0.1) is shown by a dashed line.

Validation of the S60-αTSR Nanoparticle Formation

The assembly of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle was further demonstrated using mass photometry analysis of the resin-purified S-αTSR protein. The results (Figure 3G) revealed only one form of large complexes with the molecular weights of 1967 ± 84 kDa. This matches well with the expected 1942 kDa of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle as a 60mer (T = 1 icosahedron) of S-αTSR protein with each copy having a mass of 32.37 kDa, which is calculated based on the amino acid sequences. No signals corresponding to a T = 3 (180-mer = 5826 kDa) or a T = 4 (240-mer = 7769 kDa) icosahedral particles of the S-αTSR protein were detected. The remaining signals from the mass photometry analysis did not match with the fold numbers of the S-αTSR protein, thus may represent the co-purified bacterial proteins (Figure 3B) or degraded forms of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle. The formation of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle was further demonstrated by 3D structural reconstruction (see below).

Density Analysis of the S60-αTSR Nanoparticle

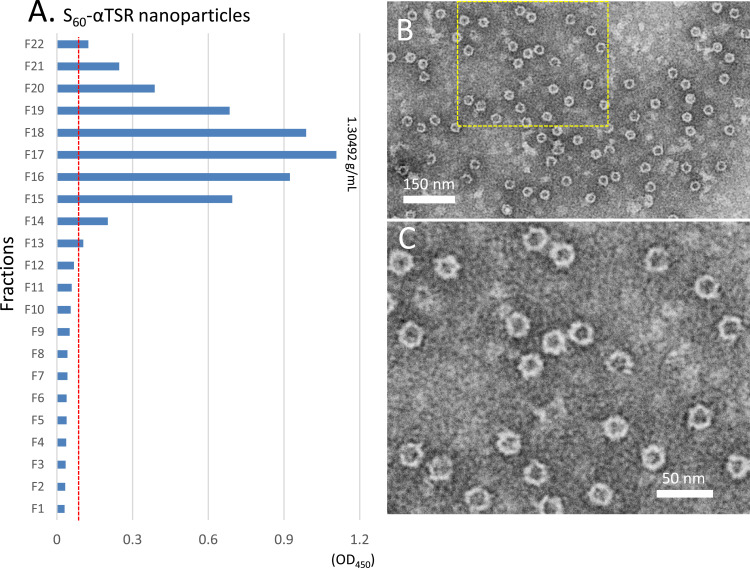

The resin purified S-αTSR protein was analyzed by CsCl density gradient ultracentrifugation. After centrifugation, the S-αTSR protein formed a visible band in the top quarter of the gradient (data not shown). EIA assays to detect the S-αTSR protein in the 22 factions of the gradient confirmed that the S-αTSR protein formed a peak around fraction 17 (Figure 4A, F17) with a density of 1.305 g/mL. Negative stain TEM inspection of fraction 17 showed uniform S60-αTSR nanoparticles in ring-like images (Figure 4B and C). It was noted that, unlike the S60 nanoparticle with smooth surface,34 the S60-αTSR nanoparticles revealed recognizable protrusions on the surface representing the displayed αTSR antigens (Figure 4C). These nanoparticle images appeared to be more uniform compared with those of gel-filtration purified ones (compared Figure 3D with Figure 4B and C).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the S60-αTSR nanoparticles after purification by cesium chloride (CsCl) density gradient centrifugation. (A) Following centrifugation, the CsCl density gradient containing the S60-αTSR nanoparticles was fractionated into 22 portions. The relative concentrations of the S60-αTSR protein in the fractions were measured by EIA assays using antibody against norovirus VLP. Y-axis indicates the fraction numbers, while X-axis shows signal intensities in optical density (OD450) with a red dashed line showing the cut-off signal at OD450=0.1. (B and C) A TEM micrograph of the S-αTSR protein of fraction 17 showing uniform S60-αTSR nanoparticles (B) with an enlargement of the framed area in (C) showing recognizable protrusions of αTSR antigens on the surface.

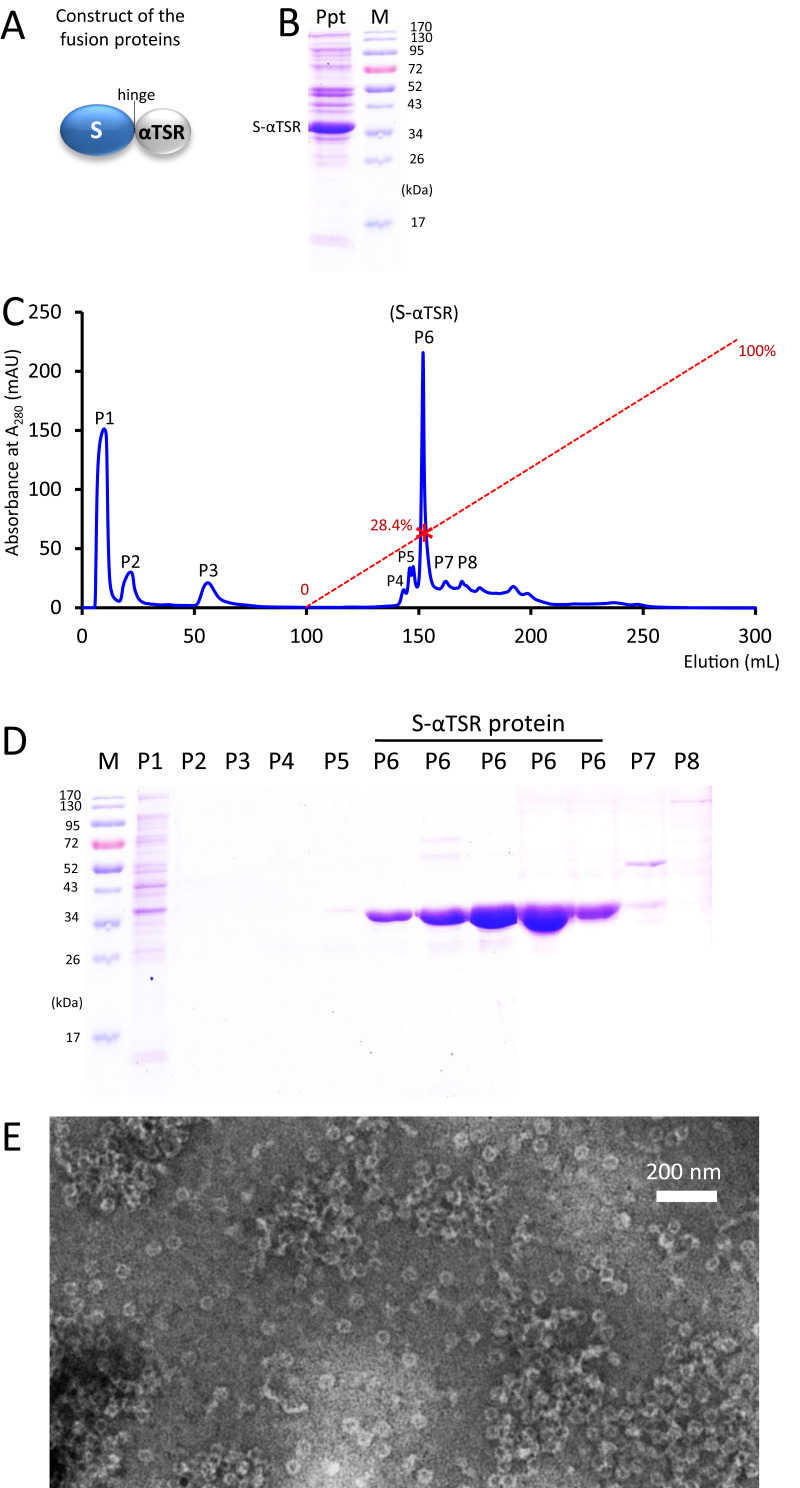

Production of Tag-Free S60-αTSR Nanoparticles

A scalable method was also developed for production of tag-free S60-αTSR nanoparticles, which contains two major steps. First, after expression the tag-free S-αTSR protein (Figure 5A) was precipitated from the bacterial lysate using 1.6 M (NH4)2SO4 (Figure 5B). Second, an anion exchange chromatography was performed to separate the (NH4)2SO4 precipitated proteins, resulting in several elution peaks (Figure 5C). The S-αTSR protein was eluted in peak 6 (P6), corresponding to a NaCl concentration of 284 mM (28.4% buffer B), reaching to a purity of >90% (Figure 5D). TEM inspection confirmed the assembly of S60-αTSR nanoparticles by the tag-free S-αTSR protein (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Production of tag-free S60-αTSR nanoparticles. (A) The schematic construct of the tag-free S-αTSR proteins. (B) SDS-PAGE showing the ammonium sulfate precipitated S-αTSR protein (Ppt) from the bacterial lysis. (C) An anion exchange elution curve of the ammonium sulfate precipitated proteins from (B). Y-axis shows UV absorbances at A280 (mAU), whereas X-axis indicates elusion volume (mL). The red dashed line indicates the linear increase of the elution buffer B (0–100%) with a red star symbol indicating the percentage of buffer B at the elution position of the S-αTSR protein (28.4%). Eight elution peaks (P1 to P8) that were analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated. (D) SDS-PAGE analyses of the eight elution peaks from the ion exchange (C). Five fractions from P6 were analyzed. M in (B and D) is protein standard with the molecular weights as indicated. The S-αTSR protein is eluted in P6. (E) A micrograph of transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the protein sample from P6 showing typical S60-αTSR nanoparticles.

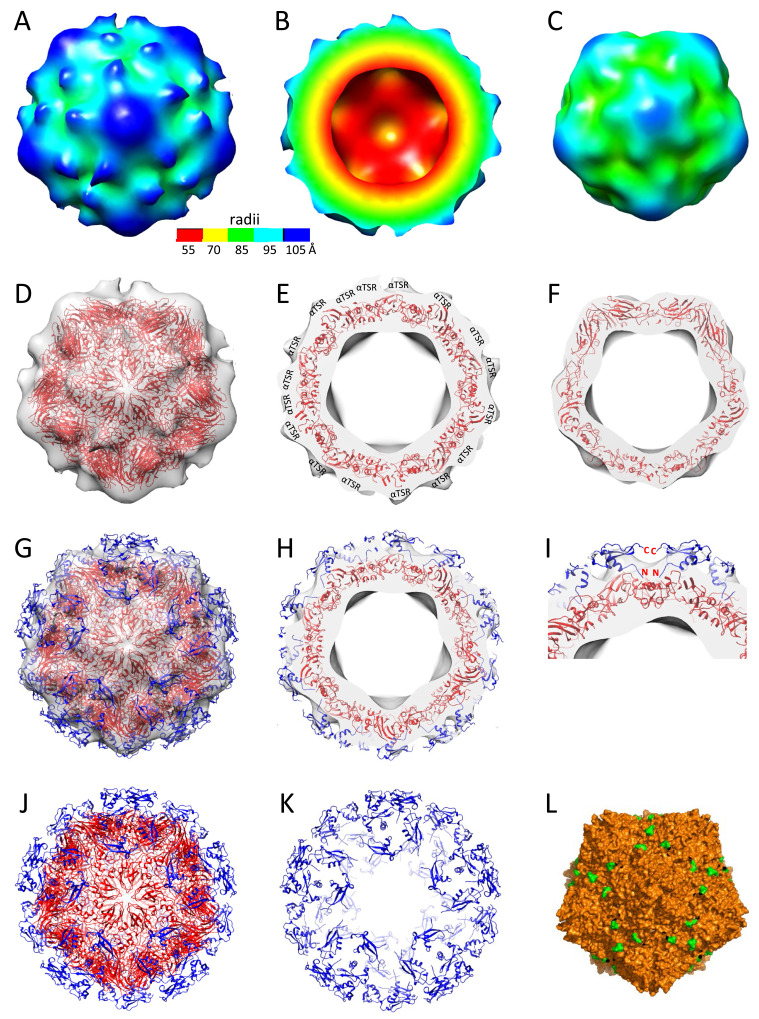

Structure of the S60-αTSR Nanoparticle

The 3D structure of the Hisx6-tagged S60-αTSR nanoparticle was reconstructed at a resolution of ~20 Å based on the negative stain TEM images using JSPR. The final structure indicated that each particle contains 60 S-αTSR proteins, organizing into a T = 1 icosahedral symmetry with a diameter of ~23 nm (Figure 6A). Sixty surface protrusions were noted, representing the displayed αTSR domains. The section view shows the outer αTSR domains, the middle S60 shell, and a central lumen (Figure 6B), respectively. Fitting of the S60 particle model into the density map confirms S60 in the interior shell region of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle (Figure 6D–F). This fitting also left the outer protrusions unoccupied, confirming the αTSR regions. The crystal structures of P. falciparum αTSR (PDB code: 3VDJ)16 fitted into the density maps of the protrusions well (Figure 6G and H). A zoom-in view of the fitting indicated that the N-terminal ends of the αTSRs go inward connecting to the inner shell (Figure 6I). This fitting further justified the S60 nanoparticle shell and the displayed αTSR domains, the two components of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle.

Figure 6.

3D structures of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle. (A to (C) The S60-αTSR nanoparticle in surface view (A) showing its external structure; section view (B) showing its cross section, internal lumen, and interior structure, as well as surface view (C) of the S60 inner shell, respectively, revealing a T = 1 icosahedral symmetry. The colored bar shows the radii of the structures in different color schemes. (D–F) Fitting of a GII.4 norovirus S60 nanoparticle model (strain VA387, red cartoon representation) into the electron density map of the S60 shell region, showing in full (D) and slice (E) views, as well as slice view of the S60 shell (F), respectively. The blank protrusions representing the displayed αTSR antigens are indicated in (E). (G and H) Fitting of the crystal structures of 60 αTSR antigens (blue cartoon representation) into the electron density maps of the protrusion regions, showing in full (G) and slice (H) views respectively. (I) A zoom-in view of the fitting region of (H) showing the N- and C-terminal ends of two αTSR antigens. (J and K) Structural model of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle (J), with its surface displayed αTSR antigens (K). (L) Crystal structure of the inner shell of the 60-valent feline calicivirus (FCV) VLP (PDB code: 4PB6, Orange surface representation) showing the surface exposed C-terminal ends of the S domain. All images are shown at five-fold axes.

While the locations of the protrusions match well the C-termini of the S60 nanoparticle (Figure 6, compared A with L), the sizes and shapes of the protrusion’s distal heads fit less well with the αTSR crystal structures. This may be due to the flexibility of the displayed αTSR domains relative to the S60 shell, attributing most likely to the flexible hinge and linker at the C terminal end of the S domains, as well as the flexible loop at the N terminus of the αTSR antigen. This phenomenon is commonly observed in structural biology. Based on the fitting, a structural model of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle in PDB format was made (Figure 6J), showing its 60-surface displayed αTSR antigens, providing a structural basis for the high αTSR specific immune response in mice (see below).

The Nanoparticle-Displayed αTSRs Retained HS Glycan Binding Function

The S60-αTSR nanoparticle was examined for their ability to bind HS glycan receptors. EIA-based binding assays showed that the resin purified S60-αTSR nanoparticle bound heparin (Figure 3H); as a negative control the S60 nanoparticle did not bind, indicating that the nanoparticle displayed αTSR antigens retained receptor binding function. The data further suggest that the nanoparticle-presented αTSR domains maintained their original structure and conformations, supporting the notion that the S60-αTSR nanoparticle can be used as a vaccine candidate.

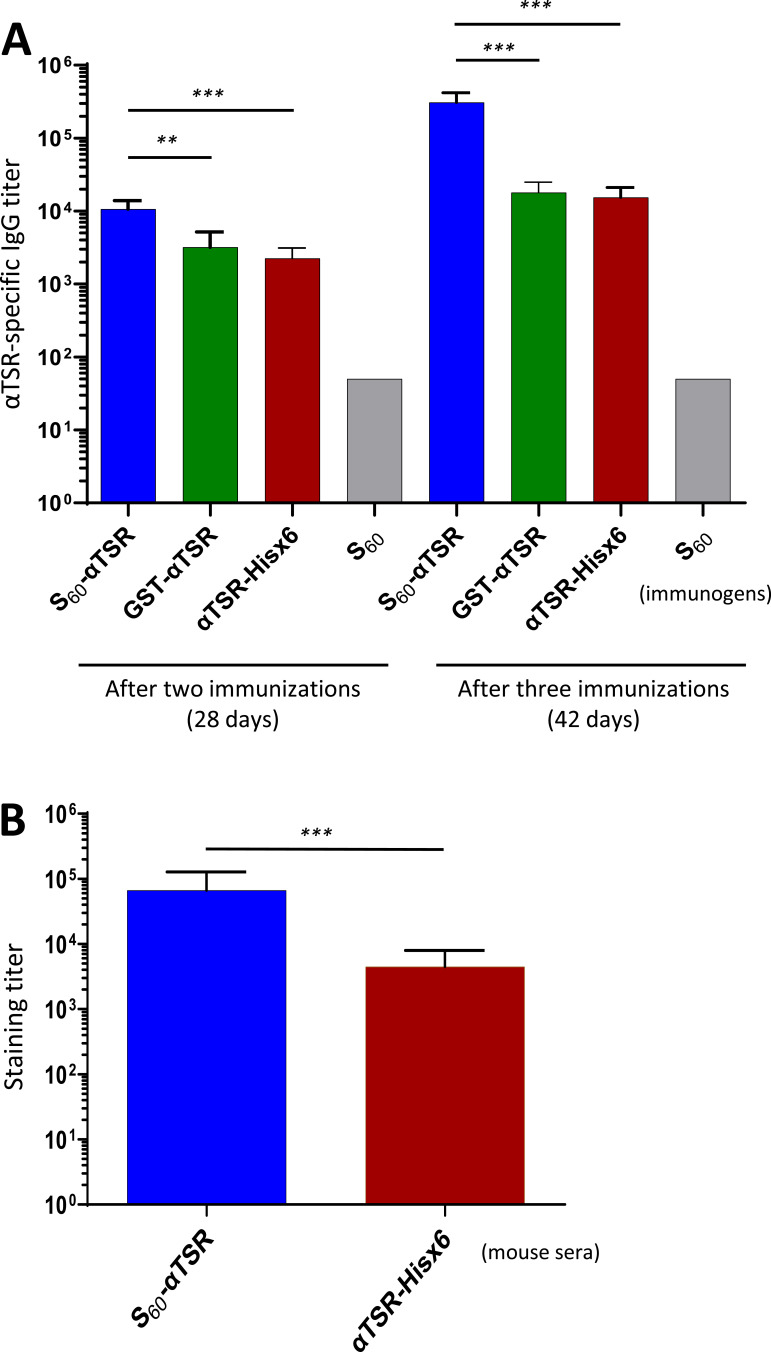

The S60-αTSR Nanoparticle Enhanced Immune Response Toward the Displayed αTSR Antigens

Literatures showed that antigens with pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) in polyvalent nature show higher immunogenicity compared with ones in mono- or low-valence.33,59–61 To test if this is true, mice were immunized with the S60-αTSR nanoparticle using the dimeric GST-αTSR (Figure 1F) and the monomeric αTSR-Hisx6 (Figure 1E) proteins for comparisons. After two and three immunizations, the nanoparticle elicited high αTSR-specific IgG titers, reaching to 10,667 and 307,200, respectively (Figure 7A). These titers were at least 3.3 folds (after two immunizations) or 17.1 folds (for three immunizations) higher than those induced by the dimeric GST-αTSR protein or those elicited by the monomeric αTSR-Hisx6 protein (Ps < 0.01). Thus, the nanoparticle displayed αTSR antigens improved their immune responses significantly.

Figure 7.

Immune response of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle in mice. (A) αTSR-specific IgG titers induced by the polyvalent S60-αTSR nanoparticle (S60-αTSR), the dimeric GST-αTSR protein (GST-αTSR), and the monomeric αTSR-Hisx6 protein (αTSR-Hisx6) after two (left four columns) and three (right four columns) immunizations are shown. Y-axes indicate αTSR-specific IgG titers, while X-axes indicate various immunogens. The S60 nanoparticle is a negative control. (B) Staining titers of the mouse sera after three immunizations of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle (S60-αTSR), and the αTSR-Hisx6 protein (αTSR-Hisx6) to air-dried P. falciparum sporozoites. Y-axis indicates staining titers, while X-axes indicate the two mouse sera. Statistic differences between data groups are shown as “**” for highly significant with P-values < 0.01 or “***” for extremely significant with P-values < 0.001.

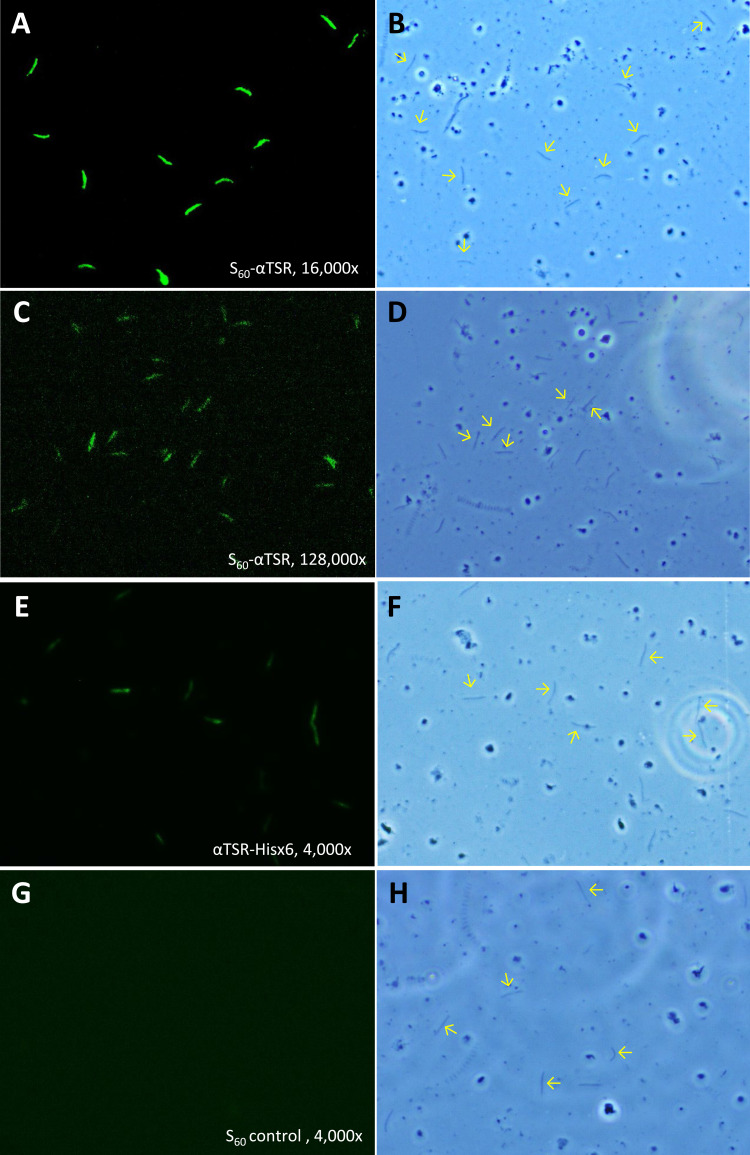

The Nanoparticle Immunized Mouse Sera Stain Sporozoite at High Titer

To further show that the αTSR-specific antibody bound the CSPs on Plasmodium sporozoites as a potential indication of the antibody to inhibit the receptor binding function of the CSPs and thus block the infection of the parasites, IFAs were performed to stain the P. falciparum sporozoites using the above mouse sera in serial dilutions between 1000x and 256,000x. The results showed that sporozoites were stained specifically by the mouse sera (Figures 7B and 8). Specifically, mouse sera after immunization with the S60-αTSR nanoparticle stained the P. falciparum sporozoites at a high titer of 66,560 that was 14.8 folds higher than the staining titer (4480) of sera after immunization with the αTSR-Hisx6 (Figure 7B). Several typical IFA micrographs, representing 16,000x (Figure 8A and B) and 128,000x (Figure 8C and D) dilutions of the sera after immunization with the S60-αTSR nanoparticle, respectively, and 4000x dilution of the sera after immunization with the αTSR-Hisx6 protein (Figure 8E and F) are shown as examples. As a negative control, mouse sera after immunization with the S60 nanoparticle did not stain the P. falciparum sporozoites even at much lower dilutions (Figure 8G and H). It was noted that, although many junks on the slides were seen under optical field using transmitted light, only the sporozoites are stained by the sera after immunization with the αTSR proteins specifically, supporting the potential of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle as a malaria vaccine candidate.

Figure 8.

Representative micrographs of immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) of P. falciparum sporozoites by the mouse sera after immunization with the S60-αTSR nanoparticle and controls. (A–D) Typical IFA micrographs representing 16,000x (A and B) and 128,000x (C and D) dilutions, respectively, of the sera after immunization with the S60-αTSR nanoparticle. (E and F) Typical IFA micrographs representing 4000x dilution of the sera after immunization with the αTSR-Hisx6 protein. (G and H) Typical IFA micrographs representing 4000x dilution of the sera after immunization with the S60 nanoparticle without αTSR antigens. Each pair of micrographs consists of an IFA staining result (A, C, E and G) and the optical view of the same field (B, D, F and H). Arrows in the optical field of view indicate some sporozoites showed in the corresponding IFA views.

Discussion

In this study, we first characterized two αTSR fusion proteins and provided solid evidence for the first time that the αTSR domain interacts with HS glycans and thus is a key functional domain of the CSP and an important vaccine target. Secondly, we generated a protein nanoparticle to display the αTSR antigens for enhanced immune response toward the displayed αTSR antigens, with a long-term goal to develop it into an effective malaria vaccine. The S60-αTSR nanoparticle with or without a tag can be produced via the E. coli system. Both structural and functional analyses revealed that 60 αTSR antigens are properly presented on the surface of the nanoparticle with authentic receptor binding function. Immunological evidence showed that the polyvalent S60-αTSR nanoparticle significantly improved the immunogenicity of the displayed αTSR antigens, eliciting high titer of αTSR-specific antibody that bound the CSPs of P. falciparum sporozoites at high titer. Therefore, the S60-αTSR nanoparticle may serve as a promising malaria candidate vaccine.

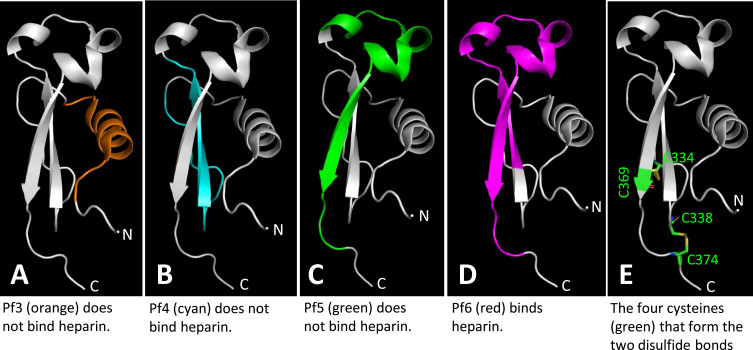

The CSP is known to recognize HSPG receptors to allow sporozoites being arrested in the liver, which is an important step of Plasmodium infection to humans.15,18–20 The TSR (region II plus) of the CSP was suggested to be the HSPG-binding domain,20–23 although discrepancy was also reported.16,24 A critical limitation of the previous studies aiming to map the HSPG-binding domain of the CSP was their usage of short synthetic peptides, mostly being smaller than 25 amino acids in length. Based on the known crystal structure,16 the αTSR domain assembles into a highly specific 3D structure (Figure 9), in which amino acid residues that are distant in linear sequence may be close in 3D structure. Therefore, the HSPG binding site on the αTSR domain is most likely conformational, which is unlikely to be well represented by a short synthetic peptide. Particularly, the crystal structure reveals two disulfide bonds that are required for the proper folding of the αTSR domain,16 but none of the tested peptides contains these two pairs of cysteines (Figure 9E).

Figure 9.

Structural analyses of four tested αTSR related peptides for binding to heparan sulfates and the two disulfide bonds reported in literature. The regions and structures of the four αTSR peptides, Pf3 (A, Orange), Pf4 (B, cyan), Pf5 (C, green), and Pf6 (D, purple),24 corresponding to the known crystal structure of the αTSR16 (in grey) are shown. The four cysteines forming the two disulfide bonds are shown in green in (E).

It is noted that, among the four peptides (Pf3 to Pf6) within the αTSR domain that were tested for HS glycan binding, only the longest one with 32 residues (Pf6, 341-IQVRIKPGSANKPKDELDYANDIEKKICKMEK-372) bound heparin/heparan sulfate.24 Analysis of the four peptides on the known αTSR crystal structure16 (Figure 9A–D) showed that only Pf6 contains full sequences to form the intact top structure of the αTSR domain (Figure 9D, purple portion), suggesting that the top moiety formed by sequences from I346 to I364 might contain the HSPG binding site. Noteworthy, the relative closeness between the N- and C-termini at the basis of the αTSR domain16 implies that the top region may form a distal head extending to the surface of parasite sheath. However, as discussed above, whether the synthetic peptides can fold into properly functional conformations remains in question. Particularly, none of these peptides contain the four cysteines for the disulfide bonds that are necessary for proper αTSR structures (Figure 9E).16

In a study focusing on the αTSR structure by crystallography, Doud et al showed that the C-terminally Hisx6-tagged αTSR did not reveal binding signals using a heparin-sepharose column.16 Similarly, we did not observe binding signals of the αTSR-Hisx6 protein to heparin in an EIA-based binding assay in this study. However, employing highly sensitive ESI-MS binding assays, we detected weak binding of the αTSR-Hisx6 to six different HS compounds in a HS glycan library with KD values in the mM range (Figure 2). Thus, the αTSR-Hisx6 does bind HS glycans at low affinity, which cannot be detected by an EIA- or column-based binding assays. Strikingly, unlike the αTSR-Hisx6 protein, two other αTSR fusion proteins, the GST-αTSR and S60-αTSR, bound both heparin and many other HS glycans in the HS glycan library strongly with KD values in the µM range (Figure 2). Since the Hisx6 tag is small, the αTSR-Hisx6 is basically a free protein (Figure 1E), whereas the αTSR in the GST-αTSR and the S60-αTSR proteins was supported by large (>21 kDa) protein. This scenario reminds us of the rotavirus VP8* domains. As the distal head of rotavirus spike protein VP4, the recombinant VP8* domain alone does not show detectable binding to its glycan receptors in EIA-based glycan binding assays, but GST-VP8* fusion proteins,55–58 S60-VP8*34,62 and P24-VP8*40 bound the same glycans well.

While the mechanism behind this phenomenon remains elusive, one explanation is that the αTSR domain, like rotavirus VP8* domain, is a part of a large protein and may need a structural support from a big protein to confer proper conformations for optimal binding affinity to the HS glycans. Structural support by a big protein may mimic the scenario that αTSR is a part of the CSP with ~400 amino acids, like the case of VP8* domain as a part of rotavirus VP4. As a next step, we plan to identify the HS glycan binding site of the αTSR domain using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and crystallography, following the footsteps of our previous studies on rotavirus VP8* domain interacting with its glycan receptors.63,64

The CSP has been shown as an immunodominant, protective antigen.25 We have now shown that the αTSR is a key functional domain of the CSP and the αTSR domain has been demonstrated to contain polymorphic T-cell epitopes eliciting CD4+ T-cell response with protection,30 strongly supporting that the αTSR is an excellent vaccine target. However, since the αTSR domain is small (~9.8 kDa) with apparently low immunogenicity in its free, monomeric form (Figure 7), a polyvalent platform will help to enhance its immune response. The 60 valent S60 nanoparticle has been shown to be a potent platform to display antigens for improved immunogenicity.34,35,65,66 Our results in this study showed that the S60-αTSR nanoparticle elicited significantly higher αTSR-specific antibody titers than those induced by the monomeric αTSR-Hisx6 or the dimeric GST-αTSR proteins. The mouse antisera after immunization with the S60-αTSR nanoparticle bound the CSPs of the P. falciparum sporozoites at a very high titer. We assume that such antibody-αTSR binding would block the HSPG binding function of the CSPs and thus would be able to prevent the liver invasion by the P. falciparum sporozoites, making the S60-αTSR nanoparticle a promising malaria vaccine candidate. Due to the lack of a suitable facility, we are reaching out to potential collaborators to evaluate the neutralization and/or protective efficacy of our S60-αTSR nanoparticle vaccine.

Another advantage of our technology is that the S60-αTSR nanoparticle can be produced using the E. coli system, providing a low-cost method for future production of our vaccine. This is particularly important because malaria occurs mostly in the source-deprived developing countries. The known crystal structure of the αTSR protein expressed by yeast Pichia did not reveal any glycosylation,16 indicating that production of our S60-αTSR nanoparticle via the E. coli system is appropriate. In fact, the data that the E. coli expressed S60-αTSR nanoparticle bound HS glycans and that the αTSR-specific antibody elicited by the S60-αTSR nanoparticle bound authentic CSPs on P. falciparum sporozoites supported our hypothesis.

Conclusion

In summary of the data presented in this study, we conclude that the αTSR is an important receptor-binding domain of the CSP and serves as an ideal vaccine target. The S60-αTSR nanoparticle displaying multiple αTSR antigens may be a promising vaccine candidate against attachment and infection of Plasmodium parasites.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Photini Sinnis at Johns Hopkins University for kindly providing air-dried sporozoites of Plasmodium falciparum on slides and the Purdue Life Science Microscopy Facility (https://ag.purdue.edu/department/arge/facilities-and-research/microscopy/index.html) for EM imaging of the S60-αTSR nanoparticle.

Funding Statement

The research described in this study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID, R56 AI148426-01A1 to M.T.), Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC, Innovation Funds 2018-2020, GAP Fund 2020-2021, and Research Innovation and Pilot Grant 2020-2021 to M.T.), and the Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training (CCTST) of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine (Pilot Collaborative Studies Grant 2018-2019 to M.T.) that was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR001425).

Abbreviations

TSR, thrombospondin type-I repeat; CSP, circumsporozoite protein; HSPG, heparan sulfate proteoglycan; HS, heparan sulfate; 3D, three-dimensional; WHO, the World Health Organization; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol; GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; VLP, virus-like particle; BSA, bovine serum albumin; SDS-PAGE, Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; FPLC, fast performance liquid chromatography system; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; FCV, feline calicivirus; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; ESI-MS, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry; HRP, horse-radish peroxidase; IFA, immunofluorescence assay; NIH, National Institute of Health; IACUC, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee; Ns, non-significant.

Disclosure

Ming Tan has a financial interest in the S particle vaccine platform technology that Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center licensed to Blue Water Vaccines, Inc. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2021. World Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2019. World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappe SH, Buscaglia CA, Nussenzweig V. Plasmodium sporozoite molecular cell biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:29–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.011603.150935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menard R. The journey of the malaria sporozoite through its hosts: two parasite proteins lead the way. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(6):633–642. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00362-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gosling R, von Seidlein L. The Future of the RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine: an alternative development plan. PLoS Med. 2016;13(4):e1001994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laurens MB. RTS, S/AS01 vaccine (Mosquirix): an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(3):480–489. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1669415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prudencio M, Rodriguez A, Mota MM. The silent path to thousands of merozoites: the Plasmodium liver stage. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(11):849–856. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sturm A, Amino R, van de Sand C, et al. Manipulation of host hepatocytes by the malaria parasite for delivery into liver sinusoids. Science. 2006;313(5791):1287–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1129720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerald N, Mahajan B, Kumar S. Mitosis in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Eukaryotic Cell. 2011;10(4):474–482. doi: 10.1128/EC.00314-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josling GA, Llinas M. Sexual development in Plasmodium parasites: knowing when it’s time to commit. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(9):573–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bancells C, Llora-Batlle O, Poran A, et al. Revisiting the initial steps of sexual development in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(1):144–154. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0291-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennink S, Kiesow MJ, Pradel G. The development of malaria parasites in the mosquito midgut. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18(7):905–918. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medica DL, Sinnis P. Quantitative dynamics of Plasmodium yoelii sporozoite transmission by infected anopheline mosquitoes. Infect Immun. 2005;73(7):4363–4369. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4363-4369.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinnis P, Zavala F. The skin: where malaria infection and the host immune response begin. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34(6):787–792. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0345-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dundas K, Shears MJ, Sinnis P, Wright GJ. Important extracellular interactions between plasmodium sporozoites and host cells required for infection. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35(2):129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doud MB, Koksal AC, Mi LZ, Song G, Lu C, Springer TA. Unexpected fold in the circumsporozoite protein target of malaria vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(20):7817–7822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205737109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Fujioka H, Nussenzweig V. Mutational analysis of the GPI-anchor addition sequence from the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7(11):1616–1626. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinzon-Ortiz C, Friedman J, Esko J, Sinnis P. The binding of the circumsporozoite protein to cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans is required for plasmodium sporozoite attachment to target cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(29):26784–26791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104038200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coppi A, Tewari R, Bishop JR, et al. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans provide a signal to Plasmodium sporozoites to stop migrating and productively invade host cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2(5):316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frevert U, Sinnis P, Cerami C, Shreffler W, Takacs B, Nussenzweig V. Malaria circumsporozoite protein binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans associated with the surface membrane of hepatocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;177(5):1287–1298. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerami C, Kwakye-Berko F, Nussenzweig V. Binding of malarial circumsporozoite protein to sulfatides [Gal(3-SO4)beta 1-Cer] and cholesterol-3-sulfate and its dependence on disulfide bond formation between cysteines in region II. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90089-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerami C, Frevert U, Sinnis P, et al. The basolateral domain of the hepatocyte plasma membrane bears receptors for the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites. Cell. 1992;70(6):1021–1033. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90251-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinnis P, Clavijo P, Fenyo D, Chait BT, Cerami C, Nussenzweig V. Structural and functional properties of region II-plus of the malaria circumsporozoite protein. J Exp Med. 1994;180(1):297–306. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ancsin JB, Kisilevsky R. A binding site for highly sulfated heparan sulfate is identified in the N terminus of the circumsporozoite protein: significance for malarial sporozoite attachment to hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(21):21824–21832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401979200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar KA, Sano G, Boscardin S, et al. The circumsporozoite protein is an immunodominant protective antigen in irradiated sporozoites. Nature. 2006;444(7121):937–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nussenzweig RS, Vanderberg J, Most H, Orton C. Protective immunity produced by the injection of x-irradiated sporozoites of plasmodium berghei. Nature. 1967;216(5111):160–162. doi: 10.1038/216160a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gwadz RW, Cochrane AH, Nussenzweig V, Nussenzweig RS. Preliminary studies on vaccination of rhesus monkeys with irradiated sporozoites of Plasmodium knowlesi and characterization of surface antigens of these parasites. Bull World Health Organ. 1979;57(1):165–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clyde DF, McCarthy VC, Miller RM, Hornick RB. Specificity of protection of man immunized against sporozoite-induced falciparum malaria. Am J Med Sci. 1973;266(6):398–403. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197312000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romero P, Maryanski JL, Corradin G, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig V, Zavala F. Cloned cytotoxic T cells recognize an epitope in the circumsporozoite protein and protect against malaria. Nature. 1989;341(6240):323–326. doi: 10.1038/341323a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reece WH, Pinder M, Gothard PK, et al. A CD4(+) T-cell immune response to a conserved epitope in the circumsporozoite protein correlates with protection from natural Plasmodium falciparum infection and disease. Nat Med. 2004;10(4):406–410. doi: 10.1038/nm1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rts SCTP. Efficacy and safety of RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine with or without a booster dose in infants and children in Africa: final results of a Phase 3, individually randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9988):31–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Targett G. Phase 3 trial with the RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine shows protection against clinical and severe malaria in infants and children in Africa. Evid Based Med. 2015;20(1):9. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2014-110089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan M, Jiang X. Norovirus capsid protein-derived nanoparticles and polymers as versatile platforms for antigen presentation and vaccine development. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(9). doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11090472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xia M, Huang P, Sun C, et al. Bioengineered norovirus S60 nanoparticles as a multifunctional vaccine platform. ACS Nano. 2018;12(11):10665–10682. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b02776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia M, Hoq MR, Huang P, Jiang W, Jiang X, Tan M. Bioengineered pseudovirus nanoparticles displaying the HA1 antigens of influenza viruses for enhanced immunogenicity. Nano Res. 2022;2022:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cibulskis RE, Alonso P, Aponte J, et al. Malaria: global progress 2000–2015 and future challenges. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0151-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan M, Jiang X. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol. 2005;79(22):14017–14030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14017-14030.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan M, Hegde RS, Jiang X. The P domain of norovirus capsid protein forms dimer and binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol. 2004;78(12):6233–6242. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6233-6242.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L, Huang P, Fang H, et al. Polyvalent complexes for vaccine development. Biomaterials. 2013;34(18):4480–4492. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia M, Huang P, Jiang X, Tan M. A nanoparticle-based trivalent vaccine targeting the glycan binding VP8* domains of rotaviruses. Viruses. 2021;13(1):72. doi: 10.3390/v13010072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang P, Farkas T, Zhong W, et al. Norovirus and histo-blood group antigens: demonstration of a wide spectrum of strain specificities and classification of two major binding groups among multiple binding patterns. J Virol. 2005;79(11):6714–6722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6714-6722.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimanius D, Dong L, Sharov G, Nakane T, Scheres SHW. New tools for automated cryo-EM single-particle analysis in RELION-4.0. Biochem J. 2021;478(24):4169–4185. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20210708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun C, Gonzalez B, Vago FS, Jiang W. High resolution single particle Cryo-EM refinement using JSPR. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2021;160:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo F, Jiang W. Single particle cryo-electron microscopy and 3-D reconstruction of viruses. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1117:401–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goddard TD, Huang CC, Ferrin TE. Visualizing density maps with UCSF Chimera. J Struct Biol. 2007;157(1):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burmeister WP, Buisson M, Estrozi LF, et al. Structure determination of feline calicivirus virus-like particles in the context of a pseudo-octahedral arrangement. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marty MT, Baldwin AJ, Marklund EG, Hochberg GK, Benesch JL, Robinson CV. Bayesian deconvolution of mass and ion mobility spectra: from binary interactions to polydisperse ensembles. Anal Chem. 2015;87(8):4370–4376. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kitova EN, El-Hawiet A, Schnier PD, Klassen JS. Reliable determinations of protein-ligand interactions by direct ESI-MS measurements. Are we there yet? J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23(3):431–441. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0311-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sonn-Segev A, Belacic K, Bodrug T, et al. Quantifying the heterogeneity of macromolecular machines by mass photometry. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1772. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15642-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan M, Huang P, Xia M, et al. Norovirus P particle, a novel platform for vaccine development and antibody production. J Virol. 2011;85(2):753–764. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01835-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia M, Wei C, Wang L, et al. Development and evaluation of two subunit vaccine candidates containing antigens of hepatitis E virus, rotavirus, and astrovirus. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25735. doi: 10.1038/srep25735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xia M, Wei C, Wang L, et al. A trivalent vaccine candidate against hepatitis E virus, norovirus, and astrovirus. Vaccine. 2016;34(7):905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang M, Mandraju R, Rai U, Shiratsuchi T, Tsuji M. Monoclonal antibodies against plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein. Antibodies. 2017;6(3). doi: 10.3390/antib6030011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swearingen KE, Lindner SE, Shi L, et al. Interrogating the plasmodium sporozoite surface: identification of surface-exposed proteins and demonstration of glycosylation on CSP and TRAP by mass spectrometry-based proteomics. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(4):e1005606. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang P, Xia M, Tan M, et al. Spike protein VP8* of human rotavirus recognizes histo-blood group antigens in a type-specific manner. J Virol. 2012;86(9):4833–4843. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05507-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Y, Huang P, Jiang B, Tan M, Morrow AL, Jiang X. Poly-LacNAc as an age-specific ligand for rotavirus P[11] in neonates and infants. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y, Ramelot TA, Huang P, et al. Glycan specificity of P[19] rotavirus and comparison with those of related P genotypes. J Virol. 2016;90(21):9983–9996. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01494-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Y, Xu S, Woodruff AL, et al. Structural basis of glycan specificity of P[19] VP8*: implications for rotavirus zoonosis and evolution. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(11):e1006707. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tan M, Jiang X. Recent advancements in combination subunit vaccine development. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(1):180–185. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1229719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan M, Jiang X. Nanoparticles of Norovirus. In: Khudyakov Y, Pumpens P, editors. Viral Nanotechnology. Norwich, UK: CRC Press, Taylor &Francis Group; 2015:363–371. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tan M, Jiang X. Subviral particle as vaccine and vaccine platform. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;6:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu C, Huang P, Zhao D, et al. Effects of rotavirus NSP4 protein on the immune response and protection of the SR69A-VP8* nanoparticle rotavirus vaccine. Vaccine. 2020;2020:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu S, Ahmed LU, Stuckert MR, et al. Molecular basis of P[II] major human rotavirus VP8* domain recognition of histo-blood group antigens. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(3):e1008386. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu S, McGinnis KR, Liu Y, et al. Structural basis of P[II] rotavirus evolution and host ranges under selection of histo-blood group antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xia M, Huang P, Jiang X, Tan M. Immune response and protective efficacy of the S particle presented rotavirus VP8* vaccine in mice. Vaccine. 2019;37(30):4103–4110. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xia M, Huang P, Tan M. A pseudovirus nanoparticle-based trivalent rotavirus vaccine candidate elicits high and cross P type immune response. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(8):1597. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14081597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]