Abstract

Objectives:

Information professionals have supported medical providers, administrators and decision-makers, and guideline creators in the COVID-19 response. Searching COVID-19 literature presented new challenges, including the volume and heterogeneity of literature and the proliferation of new information sources, and exposed existing issues in metadata and publishing. An expert panel developed best practices, including recommendations, elaborations, and examples, for searching during public health emergencies.

Methods:

Project directors and advisors developed core elements from experience and literature. Experts, identified by affiliation with evidence synthesis groups, COVID-19 search experience, and nomination, responded to an online survey to reach consensus on core elements. Expert participants provided written responses to guiding questions. A synthesis of responses provided the foundation for focus group discussions. A writing group then drafted the best practices into a statement. Experts reviewed the statement prior to dissemination.

Results:

Twelve information professionals contributed to best practice recommendations on six elements: core resources, search strategies, publication types, transparency and reproducibility, collaboration, and conducting research. Underlying principles across recommendations include timeliness, openness, balance, preparedness, and responsiveness.

Conclusions:

The authors and experts anticipate the recommendations for searching for evidence during public health emergencies will help information specialists, librarians, evidence synthesis groups, researchers, and decision-makers respond to future public health emergencies, including but not limited to disease outbreaks. The recommendations complement existing guidance by addressing concerns specific to emergency response. The statement is intended as a living document. Future revisions should solicit input from a broader community and reflect conclusions of meta-research on COVID-19 and health emergencies.

Keywords: Collaboration, emergency response, rapid review, systematic review, methods, information retrieval

INTRODUCTION

Effective public health emergency responses rely on accurate, relevant, up-to-date evidence [1–3]. However, traditional evidence retrieval methods could not sufficiently address challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, including the urgency of requests; the novelty and reach of the emergency; the transformation in publication processes and proliferation of new information portals; and the numerous teams conducting evidence syntheses of varying quality [4–6].

Librarians, particularly in hospitals, have previously searched for emergency and disaster-related literature [7,8]. However, the rapidly evolving COVID-19 pandemic prompted information professionals to seek new guidance. Existing search standards were not readily applicable, and explication was needed to implement them [9]. Preprint and grey literature became more critical, and, because the pandemic spanned medical, public health, economic, and social topics, librarians were tasked with searching outside their fields of expertise [10, 11]. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, searches were conducted to support decision making, clinical practice, and evidence synthesis. However, systematic review search strategies were often of poor quality or insufficiently reported [12,13].

The Librarian Reserve Corps (LRC), a volunteer network of over 140 medical and public health librarians from 14 countries, convened an expert panel to develop best practices for searching in public health emergencies. “Public health emergency”, in this context, encompasses a “serious, sudden, unusual or unexpected” [14] event “presenting risk to life, health, and infrastructure” [15].

Public health emergencies reveal gaps in decision making supports and guidelines. While guidelines for searching and reporting search strategies predate the writing of this statement, the rule-like nature of these guidelines can make them insufficiently flexible for guidance during public health emergencies. “The best practice approach,” as described by Sethi, “represents a middle ground between principle-like and rule-like guidelines and offers valuable interpretative support to decision-makers whilst simultaneously capturing and reflecting lessons learned” [16].

This statement provides recommendations for 1) evaluating and using core resources; 2) designing, evaluating, and sharing search strategies; 3) locating, including, and monitoring non-peer-reviewed publication types; 4) maintaining transparency and reproducibility; 5) collaborating within and across communities; and 6) conducting information science research, all during a public health emergency. Underpinning these recommendations are principles of timeliness, openness, balance, preparedness, and responsiveness.

METHODS

On November 20, 2020 (Figure 1), 15 information professionals, database creators, and evidence synthesists attended a virtual launch meeting to discuss the scope of the best practices for searching during public health emergencies and identify organizations to involve in their development. This meeting grew out of conversations among many of the attendees, who had connected via COVID-19 information response networks.

Figure 1.

The best practices for searching for evidence during public health emergencies were developed through 8 stages over 15 months

Following the meeting, we developed a protocol and identified additional experts with experience searching for literature, conducting reviews, and maintaining specialized databases to support response efforts in COVID-19 or previous public health emergencies. We made efforts to diversify subject expertise and global representation by presenting the project to international networks and requesting nominations from underrepresented regions. To accommodate individual schedules and allow for varying levels of commitment, we offered options to participate in development or review:

Participants were required to submit written responses to guiding questions, attend meetings, and review the draft statement. Participants would be named under group authorship.

Reviewers were required to review the draft statement before submission for publication. Reviewers would be named in acknowledgements.

Identification of Core Elements of the Best Practices Statement

We identified six core elements to address in the best practices statement:

Core Resources

Search Strategies

Publication Types

Transparency and Reproducibility

Collaboration

Conducting Research

Core elements were abstracted from minutes of meetings of COVID-19 database and collections creators; professional experiences searching for and monitoring COVID-19 publications, policies, and research; meta-research on COVID-19 publication trends, e.g. [4,17]; literature describing searching and evidence-based response in previous public health emergencies, e.g. [11]; and guidance for searching and conducting reviews during non-emergency situations, e.g. [18–20]. References were managed in Zotero [21].

We surveyed experts from December 2020 through February 2021, to achieve consensus on the core elements. The survey [22], administered via LibWizard [23], asked experts for contact information, preferred level of involvement, recommended references, and nominations for additional experts.

Ten experts, including academic librarians, database creators, government librarians, and clinical information specialists, responded to the survey.

Guiding Questions

On February 24, 2021, we emailed a request for written responses to questions for each core element. These guiding questions [22] were informed by the literature and reflected COVID-19 literature searching challenges.

By March 8, 2021, nine participants submitted written responses via Box [24].

Beginning in early April, LRC volunteers (Mark Mueller, MM; Stacy Brody, SB; Jennifer Coffman, JC; and Nicole Askin, NA) synthesized responses and identified discussion questions [25].

Discussion Series

Though the current project does not aim to develop reporting guidelines, several parallels were noted. The “Guidance for Developers of Health Research Reporting Guidelines” [26], as followed by authors of PRISMA-S [19], provided insights for project facilitation. On March 26, 2021, the project lead (SB) emailed participants an information packet detailing the project [26].

Between April and June 2021, we held six virtual meetings at alternating times to accommodate diverse time zones; all meetings were conducted in English only. Virtual meetings enabled broad participation and rapid development and obviated the need for external funding.

The first meeting included introductions, a project overview, and time for questions. Subsequent meetings focused on each core element. Ahead of each meeting, LRC volunteers (MM, JC) summarized points of consensus from participants' responses to the guiding questions and prepared discussion questions [22]. Participants were invited to email comments if unable to attend. The final meeting, on June 17, 2021, addressed writing, authorship, and dissemination.

Five to 11 participants attended six 90-minute meetings. One LRC volunteer (MM, JC) facilitated each discussion, and the project lead (SB) provided introductory and closing remarks. One librarian volunteer (Mary Beth McAteer) took minutes from meeting recordings.

Materials for all participants were posted on the project LibGuide [27], and LRC volunteers used Box [24] to collaborate. Materials for dissemination were posted to Open Science Framework (OSF) in July 2021 [22].

Writing the Statement

Guidance for developing reporting guidelines recommends “a small writing group made up primarily of members of the executive team” be responsible for drafting [26]. The lead author (SB) developed a writing plan and statement outline, which included recommendations and examples to “illustrat[e] how principles are worked through in practice [and] reflect real-world examples and lessons learned” [16]. Librarian volunteers (MM, JC, NA, and Sara Loree, SL) and experts (Cheryl Hamill, Emma Wilson) authored sections independently. Sections were collated (NA) and edited for style and consistency (Heather Staines).

Dissemination

The explanation and elaboration document (Supplementary Material) is being disseminated alongside the statement, as per guidance [26]. Efforts were made to ensure openness and accessibility by identifying opportunities to present and selecting an open access, PubMed-indexed journal that permitted author archiving.

A project overview was presented during webinars for the Network of the National Library of Medicine (NNLM) and the Evidence for Global and Disaster Health Special Interest Group (E4GDH) of the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) in April 2021 and June 2021, respectively.

The draft statement was shared with expert participants and reviewers in November 2021. Substantive feedback was requested via LibWizard [23].

RECOMMENDATIONS

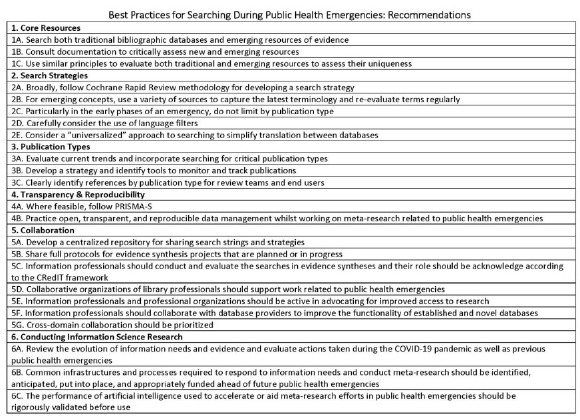

See Table 1 for the list of recommendations. See Supplementary Material for elaboration and examples.

Table 1.

The best practices for searching for evidence during public health emergencies include 23 recommendations across 6 core elements.

|

1. Core Resources

Retrieving timely and authoritative evidence is paramount to any emergency. During the COVID-19 emergency, publishers allowed open access to COVID-19 resources [28] and rapid reviews [29] and preprint articles [30] gained prominence for urgent health issues [31,32]. New and emerging COVID-19 collections such as LitCOVID [33] and the WHO COVID-19 Research Database [34] were developed to provide access to the latest specialized evidence. As research was published at a rapid pace, these resources became valuable supplements to traditional databases [35,36].

1A. Search both traditional bibliographic databases and emerging resources of evidence.

1B. Consult documentation to critically assess new and emerging resources.

1C. Use similar principles to evaluate both traditional and emerging resources to assess their uniqueness.

2. Search Strategies

Development, reporting, sharing and evaluating search strategies are essential to searching during public health emergencies. Public health emergencies pose challenges such as resource limitations and rapidly evolving search terminology and necessitate complex search strategies. Recommendations on how to design, share, report and evaluation search strategies are given below.

They also highlight opportunities for sharing: for example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Medical Library Association (47) and the Australian Library and Information Association (48) made search strings publicly available for information specialists to access and adapt.

2A. Broadly, follow Cochrane Rapid Review methodology for developing a search strategy.

2B. For emerging concepts, use a variety of sources to capture the latest terminology and re-evaluate terms regularly.

2C. Particularly in the early phases of an emergency, do not limit by publication type.

2D. Carefully consider the use of language filters.

2E. Consider a “universalized” approach to searching to simplify translation between databases.

3. Publication Types

During public health emergencies, publication trends may change quickly. Existing guidance on finding and managing non-peer-reviewed publications is not always sufficient for emergency settings. Non-peer-reviewed publication types include research outputs like preprints, clinical trial registration records, and datasets; and media publications like news articles and press releases. Recommendations in this section address how to utilize, monitor/track, and contextualize non-peer reviewed literature.

3A. Evaluate current trends and incorporate searching for critical publication types.

3B. Develop a strategy and identify tools to monitor and track publications.

3C. Clearly identify references by publication type for review teams and end users.

4. Transparency and Reproducibility

Transparency and reproducibility of search strategies allow for critical appraisal and reduce research waste. Public health emergencies generate multifaceted questions [82]. In such high-pressure environments, researchers need a clear understanding of the sources used and how they have been searched to:

have clarity and confidence that appropriate search strategies have been used

ensure that no bias has been introduced

update or validate searches

The COVID-19 pandemic stimulated a tsunami of papers and new information sources [83]. Some use artificial intelligence or custom search algorithms, which makes reproducibility uncertain. As terminology standardizes or diverges and new aspects (such as virus variants) emerge, future searches may be improved. Though it may not be desirable to reuse the exact search strategy, documentation is crucial to inform future searches and those relying on the evidence. Transparent, reproducible searches are key to producing trustworthy, quality guidelines [84,85].

4A. Where feasible, follow PRISMA-S.

4B. Practice open, transparent, and reproducible data management whilst working on meta-research related to public health emergencies.

5. Collaboration

Given the resource limitations associated with public health emergencies, openness and collaboration are key for improving evidence synthesis and reducing duplication of effort. Recommendations in this section address the need for collaboration among information professionals as well as with other stakeholders.

5A. Develop a centralized repository for sharing search strings and strategies.

5B. Share full protocols for evidence synthesis projects that are planned or in progress.

5C. Information professionals should conduct and evaluate searches in evidence syntheses and their roles should be acknowledged according to the CRediT framework.

5D. Collaborative organizations of library professionals should support work related to public health emergencies.

5E. Information professionals and professional organizations should be active in advocating for improved access to research.

5F. Information professionals should collaborate with database providers to improve the functionality of established and novel databases.

5G. Cross-domain collaboration should be prioritized.

6. Conducting Information Science Research

During the COVID-19 pandemic, information professionals raced to develop systematic search strategies and artificial intelligence algorithms to identify relevant research. Quick and collaborative validation of these methods has been essential to ensure confidence in their comprehensiveness and utility. This section recommends best practices for the conduct of meta-research to support evidence-based information responses to public health emergencies.

6A. Review the evolution of information needs and evidence and evaluate actions taken during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as previous public health emergencies.

6B. Common infrastructures and processes required to respond to information needs and conduct meta-research should be identified, anticipated, put into place, and appropriately funded ahead of future public health emergencies.

6C. The performance of artificial intelligence used to accelerate or aid meta-research efforts in public health emergencies should be rigorously validated before use.

DISCUSSION

This statement on best practices for searching during public health emergencies aims to support evidence-based decision making in emergency response efforts and complements existing guidance [19,20]. Although examples and recommendations are shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic, we hope that, even as technologies and tools evolve, the lessons learned and underlying principles will “render us better prepared” [16] for future public health emergencies.

Evaluation of core resources can ensure comprehensiveness and efficiency of searching. Transparent documentation of search strategies enables trustworthiness and supports reuse. Collaboration among information professionals, researchers, and decision makers can streamline efforts for finding and synthesizing evidence and reduce duplication. Conducting information science research can support a timelier response.

Woven throughout the recommendations are five principles to guide searching during public health emergencies:

- Timeliness: considering urgency, trade-offs, and efficiencies [127]

- Openness: documenting strategies and protocols for transparency and provenance

- Balance: using a combination of new and traditional tools

- Preparedness: taking proactive measures and planning for future emergencies

- Responsiveness: maintaining situational awareness and flexibility

We developed the best practices through a semi-structured qualitative method to synthesize expertise and experience with evidence and commentary from the literature. Due to time constraints and the dynamic nature of the response, and to enable rapid development, we allowed for flexibility rather than following traditional methodologies. We were thus able to complete the project in less than 12 months. We share materials for full transparency [22].

Limitations

The panel of participants and reviewers was primarily comprised of information professionals from higher-income, Western countries. Materials were provided, and meetings were conducted, solely in English. This limited diversity may reduce the applicability and utility of recommendations in other contexts. We may not have adequately appreciated the needs and challenges of information professionals working in low-resource settings or responding to geographically specific disasters.

Future Directions for the Statement

The statement was developed rapidly to respond to the COVID-19 public health emergency of international concern. To engage policy makers and researchers, the project team will disseminate the statement and seek assistance translating the statement into other languages for wider dissemination. The authors anticipate lessons learned and additional information needs of researchers and policy makers will be revealed in after-action reviews [128]. Furthermore, this statement provides recommendations for the current information landscape with some anticipation of its evolution. Standards continue to evolve. For instance, the Communication of Retractions, Removals, and Expressions of Concern (CORREC) working group, formed by the National Information Standards Organization (NISO) [129], may provide clarity and consistency for monitoring retractions and evaluating databases. Though we anticipate changes will be required as technologies, opportunities, and norms evolve, the underlying principles will remain.

The authors have no plans at present to assume ongoing ownership.

Following Sethi [16], our statement has been “generated from the ground up, and [the] examples offered genuinely reflect the experiences of those involved with conducting” searches for evidence. Although there is no formal plan to update the statement, one year after the official end of the COVID-19 pandemic could be an opportune time to review, engaging a broader community and drawing on conclusions from meta-research on COVID-19. To complement the best practices for searching during public health emergencies, a statement of best practices for databases and collections should be drafted (e.g. [41, 43, 45, 46]).

Future Directions for Research, Development, and Advocacy

Research

Future research should explore behaviors and beliefs around reusing, licensing, and citing search strategies and on search strategy as a research object. Research may also include creating and validating search filters for response, reviewing the evolution of information needs through stages of various types of emergencies, and studying trade-offs between time searching and appraising alternative evidence sources (e.g. preprints) and impact on decision making.

We recommend exploring strategies to increase sharing of trial identifiers across protocols, publications, press releases, preprints, and presentations. Consistent use of identifiers facilitates linking research objects and implementation of recommendations 3B and 5F.

Information Science Curricula and Competencies

The best practices inform information science competencies, training, and curricula. Information professionals involved in response must demonstrate specialized search skills, knowledge of the information landscape, and the ability to adapt and collaborate. Due to the unique nature and volume of evidence disseminated during public health emergencies and the need to respond quickly, searchers may need to perform preliminary critical appraisal [7]. Existing certificates [130], curricula [131], and trainings [132] should be updated. Professional networks and cross-domain collaborations (see: 5. Collaboration) can support these efforts.

Advocacy

Information professionals require funding, time, and recognition to conduct research, participate in evidence synthesis, support and inform databases and information retrieval systems development, and present at conferences alongside researchers [133]. Funders of evidence synthesis methods research should require applicants to involve information professionals. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, various initiatives supported the development of AI-enabled information retrieval systems [134]. The work of ensuring trustworthiness was often provided by volunteers [103]. Funders must also provide sustained support for infrastructure, such as database and protocol registration platforms.

As noted in 5. Collaboration, information professionals and professional organizations should advocate for access to research. In addition to advocating for the suspension of paywalls and the expansion of interlibrary loan allowances during emergencies, the information professional community must join efforts to advocate for sustainable infrastructure, including electricity and Internet connectivity. These are indispensable for information sharing and searching.

CONCLUSION

The authors anticipate that the best practices for searching during public health emergencies will help information specialists, researchers, and decision makers respond to public health emergencies. Our recommendations are influenced by our experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, unique in its novelty and global impact. Information trends sparked and accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic are unlikely to stop with the pandemic's end, and information professionals will continue to play important roles in emergency response and decision making.

DISCLAIMER

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Mention of any company, product, or resources does not constitute endorsement by CDC.

This study was commissioned by the World Health Organization (WHO). Copyright in the original work on which this article is based belongs to WHO. The authors have been given permission to publish this article. The author(s) alone is/are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and do not necessarily represent views, decisions or policies of the World Health Organization.

CODA

Since the drafting of this statement, Cochrane Convenes and the Global Commission issued reports on using evidence in emergency preparedness and response and addressing societal challenges, respectively [135, 136]. These documents support the need for best practices for searching for evidence during public health emergencies and describe key roles for information professionals. We encourage interested readers to review these documents.

Also in the intervening time, searchrxiv has made steady progress and issued a recommended metadata structure [137], and JCHLA published a code of practice for searching [138]. These documents may also be of interest to readers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all draft reviewers:

Leah Hagerman, MPH, Research Assistant at National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (NCCMT) McMaster University, School of Nursing, Canada

Kaitlyn Hair, BSc (Hons), Research Assistant, Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland

Megan Kocher, MLIS, Science Librarian, University Libraries, at University of Minnesota, United States

Melissa Rethlefsen, MLS, Executive Director for the Health Sciences Library and Informatics Center (HSLIC) at The University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, United States

Jodi Schneider, PhD, Assistant Professor, Information Sciences, at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Faculty Affiliate at Illinois Informatics Institute, the Beckman Institute, the Health Care Engineering Systems Center at the Coordinated Science Laboratory, and the European Union Center

Mirkuzie Woldie, Senior Research Advisor, Ministry of Health, Ethiopia

We extend our gratitude to our peer reviewers.

We are also thankful to Springshare, LLC for providing the Librarian Reserve Corps with LibGuides and LibWizard.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data associated with this article are available in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/dujqe/.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Stacy Brody: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing- Original draft preparation, Writing – Review & editing. Sara Loree: Conceptualization, Writing- Original draft preparation. Margaret Sampson: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. Shaila Mensinkai: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. Jennifer Coffman: Data Curation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Formal Analysis. Mark Heinrich Mueller: Writing- Original draft preparation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & editing. Nicole Askin: Writing- Original draft preparation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & editing. Cheryl Hamill: Writing- Original draft preparation. Emma Wilson: Data Curation, Writing- Original draft preparation. Mary Beth McAteer: Data Curation.

Best Practices for Searching During Public Health Emergencies Working Group, comprising expert panelists writing in response to guiding questions and participating in discussion meetings. Working Group members include:

Cheryl Hamill, FALIA, AALIA (CP) Health

Maureen Dobbins, RN, PhD

Amy M Claussen, MLIS

Kavita Umesh Kothari, MPH

Caroline De Brún, PhD

Sarah Young

Sarah E Neil-Sztramko

Shaila Mensinkai, MA, MLIS

Emma Wilson

Robin M Featherstone MLIS

Margaret Sampson, MLIS, PhD, AHIP

Heather Staines, PhD, MA

Martha Knuth, MLIS

SUPPLEMENTAL FILES

Appendix A: Best Practices Explanation and Elaboration

All other Supplementary files are available on OSF: https://osf.io/dujqe/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegfried AL, Carbone EG, Meit MB, Kennedy MJ, Yusuf H, Kahn EB. Identifying and Prioritizing Information Needs and Research Priorities of Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Practitioners. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2017. Oct;11(5):552–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Evidence-Based Practices for Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Evidence-Based Practice for Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response [Internet]. Calonge N, Brown L, Downey A, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2020. [cited 2021 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25650. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. International Health Regulations (2005) [Internet]. 2016. [cited 2021 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241580496.

- 4.Raynaud M, Zhang H, Louis K, Goutaudier V, Wang J, Dubourg Q, et al. COVID-19-related medical research: a meta-research and critical appraisal. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021. Dec;21(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Else H. How a torrent of COVID science changed research publishing — in seven charts. Nature. 2020. Dec 16;588(7839):553–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearson H. How COVID broke the evidence pipeline. Nature. 2021. May 12;593(7858):182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Featherstone RM, Boldt RG, Torabi N, Konrad S-L. Provision of pandemic disease information by health sciences librarians: a multisite comparative case series. J Med Libr Assoc JMLA. 2012. Apr;100(2):104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donahue AE, Featherstone RM. New roles for hospital librarians: a benchmarking survey of disaster management activities. J Med Libr Assoc JMLA. 2013. Oct;101(4):315–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schünemann HJ, Santesso N, Vist GE, Cuello C, Lotfi T, Flottorp S, et al. Using GRADE in situations of emergencies and urgencies: certainty in evidence and recommendations matters during the COVID-19 pandemic, now more than ever and no matter what. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020. Nov;127:202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clyne B, Walsh KA, O'Murchu E, Sharp MK, Comber L, O' Brien KK, et al. Using preprints in evidence synthesis: Commentary on experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021. Oct 1;138:203–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revere D, Turner AM, Madhavan A, Rambo N, Bugni PF, Kimball A, et al. Understanding the information needs of public health practitioners: A literature review to inform design of an interactive digital knowledge management system. J Biomed Inform. 2007. Aug;40(4):410–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butcher R, Sampson M, Couban RJ, Malin JE, Loree S, Brody S. The currency and completeness of specialized databases of COVID-19 publications. J Clin Epi [in press, 2022] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Nascimento IJB do, O'Mathúna DP, Groote TC von, Abdulazeem HM, Weerasekara I, Marusic A, et al. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. medRxiv. 2020. Apr 22;2020.04.16.20068213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Emergencies: International health regulations and emergency committees [Internet]. [cited 2021 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/emergencies-international-health-regulations-and-emergency-committees.

- 15.Reynolds B, Lutfy C. Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication Manual. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sethi N. Research and Global Health Emergencies: On the Essential Role of Best Practice. Public Health Ethics. 2018. Nov;11(3):237–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abbott R, Bethel A, Rogers M, Whear R, Orr N, Shaw L, et al. Characteristics, quality and volume of the first 5 months of the COVID-19 evidence synthesis infodemic: a meta-research study. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2021. Jun 3;bmjebm-2021-111710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021. Mar 29;n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst Rev. 2021. Jan 26;10(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins J. Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR) [Internet]. London: Cochrane; 2019. Oct [cited 2020 Dec 11]. Available from: https://community.cochrane.org/mecir-manual. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zotero [Internet]. Corporation for Digital Scholarship; Available from: https://www.zotero.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brody S, Wilson E, Hamill C, Coffman J, Knuth M, Sampson M, et al. Best Practices for Searching During a Public Health Emergency. 2021. Jun 24 [cited 2021 Dec 23]; Available from: https://osf.io/dujqe/.

- 23.LibWizard [Internet]. Springshare; Available from: https://www.springshare.com/libwizard/. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Box [Internet]. Box; Available from: https://www.box.com/about-us. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller M, Coffman J, Askin N, Brody S.. Discussion Questions [Internet]. Available from: https://osf.io/tm8xu/.

- 26.Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLOS Med. 2010. Feb 16;7(2):e1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LibGuides [Internet]. Springshare; [cited 2021 Sep 23]. Available from: https://springshare.com/libguides/. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aviv-Reuven S, Rosenfeld A. Publication patterns' changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal and short-term scientometric analysis. Scientometrics. 2021. Aug;126(8):6761–6784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tricco AC, Garritty CM, Boulos L, Lockwood C, Wilson M, McGowan J, et al. Rapid review methods more challenging during COVID-19: commentary with a focus on 8 knowledge synthesis steps. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020. Oct;126:177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.What are preprints and preprint servers? [Internet]. Author Services. [cited 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/publishing-your-research/making-your-submission/posting-topreprint-server/.

- 31.Langnickel L, Baum R, Darms J, Madan S, Fluck J. COVID-19 preVIEW: Semantic Search to Explore COVID-19 Research Preprints. In: Mantas J, Stoicu-Tivadar L, Chronaki C, Hasman A, Weber P, Gallos P, et al. , editors. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics [Internet]. IOS Press; 2021. [cited 2021 Jun 10]. Available from: https://ebooks.iospress.nl/doi/10.3233/SHTI210124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrity C, Gartlehner G, Kamel C, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Stevens A, Hamel C, et al. Cochrane Rapid Reviews. Interim Guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://methods.cochrane.org/rapidreviews/sites/methods.cochrane.org.rapidreviews/files/public/uploads/cochrane_rr_-_guidance-23mar2020-final.pdf.

- 33.LitCovid [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/coronavirus/

- 34.Global research on coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/global-research-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov.

- 35.Fraser N, Brierley L, Dey G, Polka JK, Pálfy M, Nanni F, et al. The evolving role of preprints in the dissemination of COVID-19 research and their impact on the science communication landscape. Dirnagl U, editor. PLOS Biol. 2021. Apr 2;19(4):e3000959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JJH, Mogg R, Smith GE, Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Jehan F, Rayner CR, et al. How COVID-19 has fundamentally changed clinical research in global health. Lancet Glob Health. 2021. May;9(5):e711–e720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savolainen R. Information landscapes as contexts of information practices. J Librariansh Inf Sci. 2021. Dec 1;53(4):655–667. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Retraction Watch [Internet]. Retraction Watch. [cited 2021 Oct 25]. Available from: https://retractionwatch.com/.

- 39.Boutron I, Chaimani A, Devane D, Meerpohl JJ, Rada G, Hróbjartsson A, et al. Interventions for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19: a living mapping of research and living network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2022 Jan 17];(11). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/1465 1858.CD013769/full. [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools | COVID-19 Rapid Evidence Reviews [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.nccmt.ca/covid-19/covid-19-evidence-reviews.

- 41.Chen Q, Allot A, Lu Z. LitCovid: an open database of COVID-19 literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021. Jan 8;49(D1):D1534–D1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarker IH. Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions. SN Comput Sci. 2021. May;2(3):160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Cochrane Collaboration. About COVID-19 Study Register [Internet]. Cochrane Community. 2021. [cited 2021 Apr 7]. Available from: https://community.cochrane.org/about-covid-19-study-register. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Living Overview of the Evidence (L·OVE) [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 24]. Available from: https://app.iloveevidence.com/loves/5e6fdb9669c00e4ac072701d?population=5e7fce7e3d05156b5f5e032a§ion=methods&classification=all.

- 45.National Institutes of Health: Office of Portfolio Analysis. Data Sources [Internet]. iSearch COVID-19 Portfolio User Guide. [cited 2021 Mar 24]. Available from: https://icite.od.nih.gov/covid19/help/data-sources.

- 46.World Health Organization. Quick Search Guide for WHO COVID-19 Database [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2021 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/quick-search-guide-who-covid-19-database.

- 47.MLA : COVID-19 Literature Searching [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.mlanet.org/page/covid-19-literature-searching.

- 48.COVID-19 Live Literature Searches [Internet]. Australian Library and Information Association. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://hla.alia.org.au/covid-19-live-literature-searches/. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, et al. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021. Feb;130:13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper C, Dawson S, Peters J, Varley-Campbell J, Cockcroft E, Hendon J, et al. Revisiting the need for a literature search narrative: A brief methodological note. Res Synth Methods. 2018;9(3):361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spry C, Mierzwinski-Urban M. The impact of the peer review of literature search strategies in support of rapid review reports. Res Synth Methods. 2018. Dec;9(4):521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016. Jul 1;75:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020. Nov 1;59(11):1218–1239.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norgaard O, Lazarus JV. Searching PubMed during a Pandemic. Gluud LL, editor. PLOS ONE. 2010. Apr 7;5(4):e10039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.VOSviewer - Visualizing scientific landscapes [Internet]. VOSviewer. [cited 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.vosviewer.com//.

- 56.Yu Y, Li Y, Zhang Z, Gu Z, Zhong H, Zha Q, et al. A bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer of publications on COVID-19. Ann Transl Med. 2020. Jul;8(13):816–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vílchez-Román C, Quiliano-Terreros R. Stability and change in public health studies in Colombia and Mexico: an exploratory approach based on co-word analysis. Rev Panam Salud Publica Pan Am J Public Health. 2018;42:e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.COVID-19 Article Filters [Internet]. PubMed. [cited 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/help/.

- 59.Levay P, Finnegan A. The NICE COVID-19 search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE and Embase: developing and maintaining a strategy to support rapid guidelines [Internet]. Health Informatics; 2021. Jun [cited 2021 Jun 16]. Available from: http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.06.11.21258749. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gianola S, Jesus TS, Bargeri S, Castellini G. Characteristics of academic publications, preprints, and registered clinical trials on the COVID-19 pandemic. Mathes T, editor. PLOS ONE. 2020. Oct 6;15(10):e0240123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Retracted coronavirus (COVID-19) papers [Internet]. Retraction Watch. 2020. [cited 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://retractionwatch.com/retracted-coronavirus-covid-19-papers/.

- 62.Metzendorf M-I, Featherstone RM. Evaluation of the comprehensiveness, accuracy and currency of the Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register for supporting rapid evidence synthesis production. Res Synth Methods. 2021. Sep;12(5):607–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bethel AC, Rogers M, Abbott R. Use of a search summary table to improve systematic review search methods, results, and efficiency. J Med Libr Assoc. 2021. Jan 7;109(1):97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Waltman L, Pinfield S, Rzayeva N, Oliveira Henriques S, Fang Z, Brumberg J, et al. Scholarly communication in times of crisis: The response of the scholarly communication system to the COVID-19 pandemic [Internet]. Research on Research Institute; 2021. Dec [cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://rori.figshare.com/articles/report/Scholarly_communication_in_times_of_crisis_The_response_of_the_scholarly_communication_system_to_the_COVID-19_pandemic/17125394/1. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Macdonald H, Loder E, Abbasi K. Living systematic reviews at The BMJ. BMJ. 2020. Jul 30;370:m2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abritis A, Marcus A, Oransky I. An “alarming” and “exceptionally high” rate of COVID-19 retractions? Account Res. 2021. Jan;28(1):58–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ortiz JR, Rudd KE, Clark DV, Jacob ST, West TE. Clinical Research During a Public Health Emergency: A Systematic Review of Severe Pandemic Influenza Management*. Crit Care Med. 2013. May;41(5):1345–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fidahic M, Nujic D, Runjic R, Civljak M, Markotic F, Lovric Makaric Z, et al. Research methodology and characteristics of journal articles with original data, preprint articles and registered clinical trial protocols about COVID-19. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020. Dec;20(1):161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.COVID-19 Primer [Internet]. COVID-19 Primer. [cited 2021 Oct 22]. Available from: https://covid19primer.com/.

- 70.Lever J, Altman RB. Analyzing the vast coronavirus literature with CoronaCentral. Proc Natl Acad Sci [Internet]. 2021. Jun 8 [cited 2021 Jun 10];118(23). Available from: https://www.pnas.org/content/118/23/e2100766118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rochwerg B, Agarwal A, Siemieniuk RA, Agoritsas T, Lamontagne F, Askie L, et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19. BMJ. 2020. Sep 4;370:m3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Living systematic reviews [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: https://community.cochrane.org/review-production/production-resources/living-systematic-reviews.

- 73.National COVID-19 Clinical Evidence Taskforce. Caring for people with COVID-19 [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: https://covid19evidence.net.au/.

- 74.Boutron I, Chaimani A, Meerpohl JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Devane D, Rada G, et al. The COVID-NMA Project: Building an Evidence Ecosystem for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020. Sep 15;173(12):1015–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kelly R. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Email Alerts [Internet]. [cited 2021 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/coronavirus/newsletter/.

- 76.Neil-Sztramko SE, Belita E, Traynor RL, Clark E, Hagerman L, Dobbins M. Methods to support evidence-informed decision-making in the midst of COVID-19: Creation and evolution of a rapid review service from the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2021;21(1):231. doi: 10.1186/s12874-021-01436-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Santos-d'Amorim K, Ribeiro de Melo R, Nonato Macedo dos Santos R. Retractions and post-retraction citations in the COVID-19 infodemic: is Academia spreading misinformation? Liinc Em Rev. 2021. May 21;17(1):e5593. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Piller C. Many scientists citing two scandalous COVID-19 papers ignore their retractions. Science [Internet]. 2021. Jan 15 [cited 2022 Jan 18]; Available from: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2021/01/many-scientists-citing-two-scandalous-covid-19-papers-ignore-their-retractions.

- 79.NIH Preprint Pilot: A Librarian Toolkit [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 3]. Available from: https://learn.nlm.nih.gov/documentation/training-packets/T000141112/.

- 80.Marcelline F. Evidence search: LGBT+ and the impact of COVID-19 [Internet]. Brighton, UK: Brighton and Sussex Library and Knowledge Service; 2021. Jul. Report No.: 29680. Available from: https://library.hee.nhs.uk/binaries/content/documents/lks/migrated-search-banks/lgbt-and-the-impact-of-covid-19/lgbt-and-the-impact-of-covid-19/hee%3AsearchDocument?forceDownload=true. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dicenso A, Bayley L, Haynes RB. Accessing pre-appraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. Evid Based Nurs. 2009. Oct;12(4):99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Context for the inventory [Internet]. McMaster Health Forum. [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.mcmasterforum.org/networks/covidend/resources-to-support-decision-makers/Inventory-of-best-evidence-syntheses/context.

- 83.Brainard J. New tools aim to tame pandemic paper tsunami. Science. 2020. May 29;368(6494):924–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Florez ID, Amer YS, McCaul M, Lavis JN, Brouwers M. Guidelines developed under pressure. The case of the COVID-19 low-quality “rapid” guidelines and potential solutions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022. Feb 1;142:194–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Amer YS, Titi MA, Godah MW, Wahabi HA, Hneiny L, Abouelkheir MM, et al. International alliance and AGREE-ment of 71 clinical practice guidelines on the management of critical care patients with COVID-19: a living systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021. Nov 14;S0895-4356(21)00363-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Batten J, Brackett A. Ensuring the rigor in systematic reviews: Part 3, the value of the search. Heart Lung J Crit Care. 2021. Apr;50(2):220–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bou-Karroum L, Khabsa J, Jabbour M, Hilal N, Haidar Z, Khalil PA, et al. Public health effects of travel-related policies on the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods systematic review. J Infect [Internet]. 2021. Jul 24 [cited 2021 Sep 2];0(0). Available from: https://www.journalofinfection.com/article/S0163-4453(21)00360-1/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Okoli GN, Rabbani R, Copstein L, Al-Juboori A, Askin N, Abou-Setta AM. Remdesivir for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Infect Dis. 2021. Sep 2;53(9):691–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IjJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 2016. Dec;3(1):160018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dahn B, Mussah V, Nutt C. Yes, we were warned about Ebola. The New York Times [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/08/opinion/yes-we-were-warned-about-ebola.html?_r=1.

- 91.Ganshorn H, Premji Z, Ronksley PE. Data Management Plan Template: Systematic Reviews. 2021. Apr 9 [cited 2021 Aug 16]; Available from: https://zenodo.org/record/4663434.

- 92.Wilson G, Bryan J, Cranston K, Kitzes J, Nederbragt L, Teal TK. Good enough practices in scientific computing. Ouellette F, editor. PLOS Comput Biol. 2017. Jun 22;13(6):e1005510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.ISSG Search Filters Resource [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jul 22]. Available from: https://sites.google.com/a/york.ac.uk/issg-search-filters-resource/home.

- 94.searchRxiv [Internet]. searchRxiv. [cited 2022 Jan 18]. Available from: https://searchrxiv.org/.

- 95.Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, Ghersi D, Moher D, Petticrew M, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2012. Dec;1(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.OSF [Internet]. Available from: https://osf.io/.

- 97.Systematic Reviews for Animals and Food [Internet]. SYREAF. [cited 2022 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.syreaf.org/.

- 98.Puga MEDS, Atallah ÁN. What editors, reviewers, researchers and librarians need to know about the PRESS, MECIR, PRISMA and AMSTAR instruments with regard to improving the methodological quality of searches for information for articles. Sao Paulo Med J Rev Paul Med. 2020. Dec;138(6):459–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rethlefsen ML, Murad MH, Livingston EH. Engaging medical librarians to improve the quality of review articles. JAMA. 2014. Sep 10;312(10):999–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.ICMJE | Recommendations | Defining the Role of Authors and Contributors [Internet]. [cited 2021 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html.

- 101.Iverson S, Seta MD, Lefebvre C, Ritchie A, Traditi L, Baliozian K. International health library associations urge the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) to seek information specialists as peer reviewers for knowledge synthesis publications. J Can Health Libr Assoc J Assoc Bibl Santé Can. 2020. Jul 30;41(2):77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rethlefsen ML, Farrell AM, Osterhaus Trzasko LC, Brigham TJ. Librarian co-authors correlated with higher quality reported search strategies in general internal medicine systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015. Jun;68(6):617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Callaway J. The Librarian Reserve Corps: An Emergency Response. Med Ref Serv Q. 2021. Jan 2;40(1):90–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Scholten RJPM, Clarke M, Hetherington J. The Cochrane Collaboration. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005. Aug;59 Suppl 1:S147–S149; discussion S195-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Evidence for Global and Disaster Health Special Interest Group [Internet]. IFLA. [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.ifla.org/units/e4gdh/.

- 106.Aiwuyor J. ARL Urges Publishers to Maximize Access to Digital Content during COVID-19 Pandemic [Internet]. Association of Research Libraries. 2020. [cited 2021 May 7]. Available from: https://www.arl.org/news/arl-urges-publishers-to-maximize-access-to-digital-content-during-covid-19-pandemic/.

- 107.Modjarrad K, Moorthy VS, Millett P, Gsell P-S, Roth C, Kieny M-P. Developing Global Norms for Sharing Data and Results during Public Health Emergencies. PLOS Med. 2016. Jan 5;13(1):e1001935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Search help - COVID-19 Study Register [Internet]. [cited 2021 Oct 15]. Available from: https://community.cochrane.org/search-help-covid-19-study-register.

- 109.Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register evaluation study [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.cochrane.org/news/cochrane-covid-19-study-register-evaluation-study.

- 110.Clifton VL, Flathers KM, Brigham TJ. COVID-19 - Background and Health Sciences Library Response during the First Months of the Pandemic. Med Ref Serv Q. 2021. Mar;40(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Groot G, Baer S, Badea A, Dalidowicz M, Yasinian M, Ali A, et al. Developing a rapid evidence response to COVID-19: The collaborative approach of Saskatchewan, Canada. Learn Health Syst. 2021;e10280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 112.Di Girolamo N, Meursinge Reynders R. Characteristics of scientific articles on COVID-19 published during the initial 3 months of the pandemic. Scientometrics. 2020. Oct;125(1):795–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li W, Sun K, Zhu Y, Song J, Yang J, Qian L, et al. Analyzing the Research Evolution in Response to COVID-19. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. 2021. Apr;10(4):237. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lavis J. COVID-END taxonomy of public-health measures, clinical management of COVID-19, health-system arrangements, and economic and social responses. McMaster Health Forum; 2021. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Noel-Storr A, Dooley G, Featherstone R, Wisniewski S, Shemilt I, Thomas J, et al. Crowdsourcing and COVID-19: a case study of Cochrane Crowd. JEAHIL. 17(2):27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 116.The CAMARADES COVID-SOLES Group. Building a Systematic Online Living Evidence Summary of COVID-19 Research. JEAHIL. 17(2):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 117.O'Mara-Eves A, Thomas J, McNaught J, Miwa M, Ananiadou S. Using text mining for study identification in systematic reviews: a systematic review of current approaches. Syst Rev 2015;4(5). doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Marshall IJ, Noel-Storr A, Kuiper J, Thomas J, Wallace BC. Machine learning for identifying Randomized Controlled Trials: An evaluation and practitioner's guide. Res Synth Methods. 2018. Dec;9(4):602–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Marshall IJ, Wallace BC. Toward systematic review automation: a practical guide to using machine learning tools in research synthesis. Syst Rev. 2019. Dec;8(1):163, s13643-019-1074–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bahor Z, Liao J, Macleod MR, Bannach-Brown A, McCann SK, Wever KE, et al. Risk of bias reporting in the recent animal focal cerebral ischaemia literature. Clin Sci. 2017. Oct 15;131(20):2525–2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Liao J, Ananiadou S, Currie LG, Howard BE, Rice A, Sena SE, et al. Automation of citation screening in pre-clinical systematic reviews [Internet]. Neuroscience; 2018. Mar [cited 2021 Aug 16]. Available from: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/280131. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Voorhees E, Alam T, Bedrick S, Demner-Fushman D, Hersh WR, Lo K, et al. TREC-COVID: constructing a pandemic information retrieval test collection. ACM SIGIR Forum. 2020. Jun;54(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Soni S, Roberts K. An evaluation of two commercial deep learning-based information retrieval systems for COVID-19 literature. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021. Jan 15;28(1):132–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang LL, Lo K, Chandrasekhar Y, Reas R, Yang J, Burdick D, et al. CORD-19: The COVID-19 Open Research Dataset. arXiv200410706 Cs [Internet]. 2020. Jul 10 [cited 2022 Jan 19]; Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2004.10706.

- 125.Baclic O, Tunis M, Young K, Doan C, Swerdfeger H. Challenges and opportunities for public health made possible by advances in natural language processing. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2020. Jun 4;161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 126.Shemilt I, Noel-Storr A, Thomas J, Featherstone R, Mavergames C. Machine Learning Reduced Workload for the Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register: Development and Evaluation of the Cochrane COVID-19 Study Classifier [Internet]. 2022. [cited 2022 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-689189/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 127.Rubin GJ, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Brooks SK. Quality appraisal of evidence generated during a crisis: in defence of ‘timeliness' and ‘clarity' as criteria. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2021. Jun 24;bmjebm-2021-111760. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 128.Parker GW. Best practices for after-action review: turning lessons observed into lessons learned for preparedness policy. Rev Sci Tech Int Off Epizoot. 2020. Aug;39(2):579–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.NISO Voting Members Approve Work on Recommended Practice for Retracted Research [Internet]| National Information Standards Organization. 2021. [cited 2022 Nov 23] Available from: https://www.niso.org/press-releases/2021/09/niso-voting-members-approve-work-recommended-practice-retracted-research. [Google Scholar]

- 130.MLA : Professional Development : Disaster Information Specialization [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.mlanet.org/page/disaster-information-specialization.

- 131.Ascher M. HSL Research Guides: Critical Appraisal Institute for Librarians: Home [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 19]. Available from: https://guides.library.nymc.edu/c.php?g=882161&p=6338244.

- 132.Accessing the Evidence During Times of Crisis (recording) [Internet]. Knowledge Connection. [cited 2022 Jan 19]. Available from: http://www.medlibed.org/products/1947/accessing-the-evidence-during-times-of-crisis-recording.

- 133.Grace and Harold Sewell Memorial Fund [Internet]. Grace and Harold Sewell Memorial Fund. 2019. [cited 2021 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.sewellfund.org/.

- 134.Huergo J. NIST and OSTP Launch Effort to Improve Search Engines for COVID-19 Research [Internet]. NIST. 2020. [cited 2021 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2020/04/nistand-ostp-launch-effort-improve-search-engines-covid-19-research.

- 135.Cochrane. Cochrane Convenes: Preparing for and responding to global health emergencies. What have we learnt from COVID-19? Reflections and recommendations from the evidence synthesis community [Internet]. 2022. [cited 2022 Dec 13]. Available from: https://convenes.cochrane.org/report.

- 136.Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges. The Evidence Commission report: A wake-up call and path forward for decisionmakers, evidence intermediaries, and impact-oriented evidence producers [Internet]. McMaster Health Forum. 2022. [cited 2022 Dec 13]. Available from: https://www.mcmasterforum.org/networks/evidence-commission/report/english. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Haddaway NR, Rethlefsen ML, Davies M, Glanville J, McGowan B, Nyhan K, Young S. A suggested data structure for transparent and repeatable reporting of bibliographic searching [Internet]. AgriRxiv, 2022. [cited 2022 Dec 13]. Available from: 10.31220/agriRxiv.2022.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 138.Ballantyne SB. Developing a code of practice for literature searching in health sciences: A project description. J Can Health Libr Assoc. 2022; 43(1). doi: 10.29173/jchla29409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A: Best Practices Explanation and Elaboration

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with this article are available in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/dujqe/.