Abstract

Intrinsic stressors associated with life-history stages may alter the responsiveness of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and responses to extrinsic stressors. We administered adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) to 24 free-ranging adult female northern elephant seals (NESs) at two life-history stages: early and late in their molting period and measured a suite of endocrine, immune, and metabolite responses. Our objective was to evaluate the impact of extended, high-energy fasting on adrenal responsiveness. Animals were blood sampled every 30 min for 120 min post-ACTH injection, then blood was sampled 24 h later. In response to ACTH injection, cortisol levels increased 8- to 10-fold and remained highly elevated compared with baseline at 24 h. Aldosterone levels increased 6- to 9-fold before returning to baseline at 24 h. The magnitude of cortisol and aldosterone release were strongly associated, and both were greater after extended fasting. We observed an inverse relationship between fat mass and the magnitude of cortisol and aldosterone responses, suggesting that body reserves influenced adrenal responsiveness. Sustained elevation in cortisol was associated with alterations in thyroid hormones; both tT3 and tT4 concentrations were suppressed at 24 h, while rT3 increased. Immune cytokine IL-1β was also suppressed after 24 h of cortisol elevation, and numerous acute and sustained impacts on substrate metabolism were evident. Our data suggest that female NESs are more sensitive to stress after the molt fast and that acute stress events can have important impacts on metabolism and immune function. These findings highlight the importance of considering life-history context when assessing the impacts of anthropogenic stressors on wildlife.

Keywords: HPA axis, pinniped, stress, thyroid hormone

INTRODUCTION

All vertebrates experience stressors that challenge homeostasis. An intrinsic stressor is an internal stimulus that results in a significant change to homeostatic set points. Intrinsic stressors may arise from specific periods associated with life-history stages. Stress responses may directly influence the timing of life-history transitions (1). Conversely, an extrinsic stressor is a factor in the external environment that triggers a stress response (2). Extrinsic stressors can be of anthropogenic origin (e.g., pollutants, entanglement, noise) or natural origin, which can also be influenced by anthropogenic activity (resource limitation, environmental changes, and intra- and interspecies interactions). A significant objective in modern conservation includes quantifying population-level changes in response to stress induced by the disturbance of wildlife (3). How individuals respond to stressors is highly important for individual health; impacts of environmental stressors typically manifest in individual physiology before noticeable changes occur at the population level, thus highlighting the importance of physiological measurements as a means for early detection and prediction of disturbance effects (4). Conservation physiology aims to describe population susceptibility to disturbance and variation in this susceptibility to disturbance based on the life-history stage through physiological data (5).

Many stressors result from, or are influenced by, anthropogenic activities (6). Recently, the population consequences of multiple stressors (PCoMS) framework was developed to quantify health-related changes in the physiology and behavior of marine mammals in response to anthropogenic stress exposure (7). This framework illustrates that changes in behavior or physiology in response to a disturbance or stressor may alter individual vital rates, including survival, fitness, and growth (8). Linking functions of this framework include physiological and behavioral changes in response to acute or chronic stressors and the effects of those changes on individual health and reproduction (9). A key research question is how intrinsic stressors that arise from natural life histories influence the cumulative or aggregate responses to other stressors (7).

The neuroendocrine stress axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal, hereafter HPA axis) is a highly conserved system activated in response to stressors in all vertebrates. This axis triggers the release of glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol) and allows animals to respond to and recover from stress. The hypothalamus releases a corticotropin-releasing hormone, which acts upon the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), initiating the release of cortisol from the adrenal cortex. Cortisol is essential for maintaining homeostatic conditions in the body and generates widespread effects on metabolism, reproduction, and immune function (10, 11). Cortisol mobilizes energy stores to meet energy requirements, including the nutrient demands associated with specific life-history characteristics (12). Increased cortisol release in response to unpredictable events (an acute stress response) promotes escape behaviors and suppresses activities not essential to survival. However, chronic elevation of cortisol can negatively impact health (13). The physiological impact of maintaining high cortisol levels is called allostatic load; in the past decade, there has been increased interest in how anthropogenic stressors trigger population health changes through increased allostatic load of individuals (5, 14).

The seasonal variations in cortisol levels across many taxa that are associated with intrinsic stressors (15) emphasize the importance of describing natural variation in HPA axis responsiveness. Such information is critical to interpret baseline cortisol levels and the impacts of extrinsic anthropogenic stressors (16). Though challenging to study due to their life at sea, marine mammals face stressors at critical life-history stages. These stressors include pollution, ocean noise, declining prey stocks, and interactions with vessels and fisheries (17–20). There is evidence of individual stress responses to these extrinsic stressors (21–23) and that the characteristics of these stress responses vary with life-history stage (24–26). Underlying these responses are changes in HPA axis responsiveness.

Increases in circulating cortisol levels can be experimentally induced by the exogenous injection of ACTH. ACTH injection (also referred to as ACTH challenge) has been performed in a small number of marine mammal systems. For example, the ACTH challenge was compared with handling-induced stress in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) (27). In harbor seals, there was a lack of seasonal variation in response to ACTH (Phoca vitulina) (28, 29), whereas seasonal variability was evident in Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) (30). Adult male northern elephant seals (NESs; Mirounga angustirostris) maintain their HPA axis responsiveness across life-history stages but with metabolic responses to ACTH and HPA axis feedback that varied with the stage (31). Juvenile NESs mounted endocrine responses to additional stressors despite variations in baseline cortisol levels (32). Despite these advancements, little is known about how cortisol modulates physiological changes within adult female NESs across life-history stages. No study has investigated HPA responsiveness in a free-ranging adult female pinniped.

Activation of the HPA axis influences the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis, which produces thyroid hormones that regulate whole animal metabolism (33). Reductions in thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and biologically active thyroid hormones are associated with HPA axis activation (34). Deiodinase enzymes convert thyroxine (T4) to active thyroid hormone triiodothyronine (T3), or inactive thyroid hormone reverse triiodothyronine (rT3) (35, 36). Food deprivation, illness, and high cortisol levels alter deiodinase enzyme conversion, effectively suppressing T3 levels and enhancing rT3 conversion (34, 37).

The HPA axis is also linked to the immune system. However, cortisol concentrations, the immune analyte in question, and species contribute to observed differences in the influence of cortisol on immune parameters (38, 39). Cortisol demonstrates immunosuppressive effects in many wildlife systems including downregulating lymphocytes, suppressing monocyte proliferation, and altering cytokines (40–43).

Aldosterone, a hormone necessary for electrolyte balance, has gained attention as an important marine mammal stress response indicator. Increases in aldosterone in response to acute stress have been observed in Atlantic bottlenose dolphins, harbor seals, and NESs (28, 29, 31, 32, 44). These strong correlations between aldosterone and cortisol occur across all life-history stages in juvenile NESs, suggesting dual regulation by the HPA axis and renin-angiotensin system in times of stress (37). Though the role played by aldosterone in the adaptive stress response for mammals in hyperosmotic environments is not clear, we evaluated aldosterone as a potential stress hormone.

NESs are capital breeding marine mammals that separate foraging and breeding spatially and temporally. They forage at sea to gain energy stores that sustain them through prolonged fasting periods on shore. NESs undergo two extended fasting periods, ∼1 mo for breeding and ∼1 mo for molting. Maintenance metabolism during prolonged fasting is met primarily by lipid catabolism, facilitated by significant increases in cortisol levels (31, 32, 45). After their postbreeding foraging trip, between April and June, adult female NESs come on shore to undergo a catastrophic molt that involves synthesizing new pelage and underlying epidermis across ∼42 days on shore, rapidly losing ∼25% of their body mass due to the high energetic demand of this process (46). NESs are a highly tractable system to study stress responses in animals that forage over a large spatial and temporal scale. Champagne et al. (47) previously showed that NESs do not mount a stress response to handling when properly sedated for sampling; this allows accurate measurement of baseline cortisol levels and subsequent cortisol level changes due to ACTH stimulation.

Our objective was to characterize endocrine and physiological responses to an ACTH challenge across the molt fast in adult female NESs. This capital-breeding marine mammal experiences high levels of intrinsic stress related to extended fasting periods. In early and late molting females, we evaluated the magnitude of the stress response and adrenal hormones cortisol and aldosterone as metrics of HPA axis activation. Thyroid axis hormones and immune analytes were quantified to assess the influence of cortisol on thyroid and immune function. Select metabolites were measured as protein catabolism, lipolysis, and carbohydrate metabolism metrics. These data provide insights into how disturbance affects physiological functions and, by extension, health in individual adult female NESs and how these effects are influenced by natural fasting.

METHODS

Study Site and Study Animals

All animal handling procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Sonoma State University and University of California Santa Cruz and the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED) and were conducted under National Marine Fisheries Service Permit No. 19108, 23188. Twenty-four adult female NESs were studied at Año Nuevo State Reserve in San Mateo County, California during the 2020 and 2021 molting seasons (May–June). Different females were sampled at two stages: early molt (EM, n = 12) and late molt (LM, n = 12). Females were visually assessed for molt status. EM females exhibited minimal signs of molting, whereas LM females were 100% molted and exhibited regrowth of hair. Animals were considered adult based on body mass. If not already present, animals were marked with rear flipper tags (Dalton jumbo Roto-tags, Oxon, UK) and hair dye (Lady Clairol, Stamford, CT).

Field Procedures

Each female was sedated with an intramuscular injection of ∼1.0 mg·kg−1 of tiletamine HCl and zolazepam HCl (Telazol, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA). Immobilization was maintained with intravenous injections of ketamine HCl (Ketaset, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA). Blood samples were obtained from the extradural vein with an 18-g spinal needle and collected into chilled serum and sodium heparin blood tubes. After initial (pre) blood samples, the animal was given an intramuscular injection of 0.204 ± 0.014 (SD) IU·kg−1 corticotrophin LA gel (ACTH; Westwood Pharmacy, Richmond, VA). ACTH dosages were chosen based on previous investigations in other age classes (32, 48). Blood samples were taken every 30 min for 2 h post-ACTH injection. Blood samples were placed on ice until returned to the laboratory.

Immediately after ACTH injection, females were given an intravenous injection of 24.4 MBq of tritiated water (HTO) in 2 mL sterile water to determine body composition. Serum samples collected at ∼120 min postinjection were used as postequilibration samples. Animals were weighed using an aluminum tripod, weighing sling, and hanging scale (MSI, Seattle, WA). Approximately 24 h later [23.53 ± 1.71 (SD) h], subjects were relocated and briefly immobilized using the identical sedation procedure for a single blood sample collection. We were unable to obtain 24-h samples for one EM and five LM animals due to proximity to the waters’ edge, the density of haulout, or inability to locate the animal, reducing the total number of individuals for this time point to n = 11 for EM and n = 7 for LM.

Laboratory Procedures

Blood samples were centrifuged for 15 min (1,500 g at 4°C), then plasma and serum were collected and frozen at −80°C for later analysis. Analyte concentrations were measured in duplicate with commercially available kits (Table 1). Glucose and lactate were measured in duplicate using a YSI2300 STAT plus auto-analyzer (YSI, Yellow Springs, OH). Blood urea nitrogen (BUN; Stanbio, Boerne, TX), nonesterified fatty acids (NEFAs; Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA), and β-hydroxybutyrate (β-HBA; Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI) were measured in duplicate using enzymatic colorimetric assays. All assays have been validated previously for use in elephant seals (31, 47, 49, 50). Cortisol and aldosterone were assayed for the full-time series. In contrast, tT4, tT3, rT3, glucose, lactate, BUN, NEFAs, β-HBA, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), total immunoglobulin G (IgG), and total immunoglobulin M (IgM) were assayed at three time points (pre, 120 min, and 24 h).

Table 1.

Analytes, intra-assay coefficients of variation, assay type, and manufacturer used for each immunoassay analyte

| Analyte | CV% | Assay | Manufacturer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone | Cortisol | 3.17 | RIA | MP Biomedical, Washington, DC |

| Hormone | Aldosterone | 3.98 | RIA | MP Biomedical, Washington, DC |

| Hormone | tT4 | 3.16 | RIA | MP Biomedical, Washington, DC |

| Hormone | tT3 | 3.79 | RIA | MP Biomedical, Washington, DC |

| Hormone | rT3 | 4.34 | RIA | Alpco, Salem, NH |

| Cytokine | IL-1β | 3.27 | Canine IL-1β ELISA | RayBio, Norcross, GA |

| Cytokine | IL-6 | 3.79 | Canine IL-6 ELISA | RayBio, Norcross, GA |

| Immunoglobulin | IgG | 2.63 | Easy-Titer Human IgG | Fisher Easy-titer |

| Immunoglobulin | IgM | 2.49 | Easy-Titer Human IgM | Fisher Easy-titer |

CV%, coefficients of variation; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; rT3, reverse triiodothyronine; tT4, total thyroxine; tT3, total triiodothyronine.

Water was collected from serum samples (∼250 µL) into scintillation vials by way of dry-ice distillation (51). Betaphase scintillation cocktail (7 mL; Westchem, San Diego, CA) was added to each scintillation vial. The plasma activity of each sample was determined using a Beckmann model LS 6500 liquid scintillation counter (Beckmann, Orange County, CA). All samples were analyzed in triplicate. The amount of tracer injected was determined by gravimetric calibration of the syringes used for isotope administration. Total body water (TBW) was calculated as the total amount of radioactivity injected divided by the radioactivity of the postequilibration sample. TBW determinations were decreased by 4%, as the tritium dilution method slightly overestimates TBW volume (52–54). Body composition was calculated from measurements of TBW estimated by the tritium dilution method (55), assuming that lipid has no free water and that fat-free mass has a hydration state of 73.3% free water (46, 55). Lipid mass was calculated as:

| (1) |

where Mlipid is the lipid mass and Mtotal is the total body mass.

Data Analysis

All analyses were performed in JMP Pro 15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Linear mixed models (LMMs) for the full-time series were used for cortisol and aldosterone with an unequal variance repeated measures covariance structure and seal ID as a random effect to identify significant changes from baseline. Area under the curve above baseline (AUC) values were calculated for cortisol and aldosterone using the trapezoid rule in Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) to evaluate the magnitude of change across the 2-h postinjection period in both life-history stages. Student’s t tests were used to compare AUC values, mass, and percent body fat between life-history stages. Linear regressions were used to assess relationships between AUCs and to determine the effects of body composition on the response. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to identify AUC association slope differences between stages.

LMMs were used to evaluate differences between the pre, 120-min, and 24-h time points, with seal ID as random effect and stage, time, and stage × time as fixed effects. Denominator degrees of freedom were approximated for F statistics using the Kenward–Rogers method. Model residuals were visually assessed for normality and homoscedasticity, and data were log-transformed if necessary. Post hoc comparisons between life-history stages and time points were performed using a Student’s t test to compare least square means after significant effects tests. All data are expressed as means ± SE. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Mass and Body Composition

Mass and body composition (%fat) varied between molt stages. EM females had significantly greater mass (372 ± 62 vs. 297 ± 52, t = 3.20, df = 22, P = 0.004) and body fat (29.2 ± 2.0% vs. 27.1 ± 1.16% t = 3.09, df = 22, P = 0.005) than LM females. Mass and body composition data were highly correlated (r = 0.50, P = 0.01).

Hormone Response to ACTH

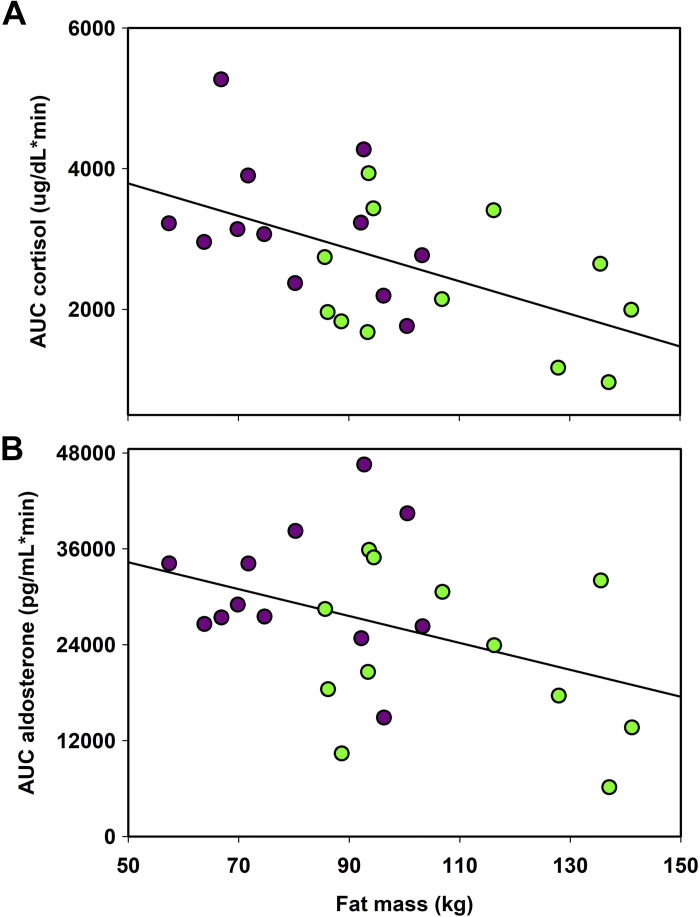

The small variation in mass-specific ACTH dose did not significantly affect any responses. It was removed from all of the following models. In the repeated measures analysis, cortisol concentrations increased relative to baseline by 30 min and remained elevated across sampling in both life-history stages (F4,92 = 154.0, P < 0.001; Fig. 1A). The magnitude of cortisol release (AUCcort) was greater in LM females than EM females (t = 2.64, df = 22, P = 0.001). Because mass and body composition were highly correlated (r = 0.50), we multiplied mass by the proportion of adipose tissue to create a new variable, fat mass (kg), as a measure of body reserves to evaluate the effect of body reserves on AUC values. Fat mass was predictive of the AUCcort response (r2 = 0.30 F1,22 = 9.38, P = 0.006, Fig. 2A). For evaluation of differences between pre, 120 min, and 24-h samples, cortisol levels varied between time points and molt stages (Table 2, Fig. 3A). Serum cortisol was significantly elevated above baseline at 120 min and remained elevated at 24 h for both EM and LM. Serum cortisol concentrations were higher in LM females than in EM females at baseline and at 120 min (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Time series of changes in cortisol (A) and aldosterone (B) concentrations in response to ACTH injection in adult female NESs at two life history stages. EM females are green symbols (n = 12), LM females are purple symbols (n = 12). Time 0 represents preinjection. Hormone concentrations were different from time 0 at 30 min and after for both groups. Error bars are SE. ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; EM, early molt; LM, late molt; NESs, northern elephant seals.

Figure 2.

Relationship between fat mass and area under the curve (AUC) for cortisol (A) and aldosterone (B). A: r2 = 0.30 F1,22 = 9.38, P = 0.00 r 6; B: r2 = 0.18, F1,22 = 4.82, P = 0.04. Green symbols are EM females and purple symbols are LM females. EM, early molt; LM, late molt.

Table 2.

Model results from a generalized linear model examining effects of explanatory variables on hormone levels

| Stage |

Time |

Stage × Time |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID VC% | Den df | F | P | Den df | F | P | Den df | F | P | |

| Cortisol | 39.3 | 22.05 | 19.57 | 0.0002 | 39.17 | 192.60 | <0.0001 | 39.17 | 7.89 | 0.001 |

| Aldosterone | 37.1 | 22.10 | 5.29 | 0.03 | 39.30 | 194.73 | <0.0001 | 39.30 | 1.59 | 0.22 |

| tT4 | 84.1 | 22.28 | 2.25 | 0.15 | 38.45 | 35.42 | <0.0001 | 38.45 | 1.17 | 0.32 |

| tT3 | 72.4 | 22.31 | 0.17 | 0.68 | 36.84 | 35.00 | <0.0001 | 36.84 | 2.06 | 0.14 |

| rT3 | 73.1 | 22.33 | 1.05 | 0.32 | 38.64 | 162.0 | <0.0001 | 38.64 | 4.46 | 0.02 |

Stage represents early molt (EM) and late molt (LM) groups, time represents pre, 120 min, and 24-h time points. Statistically significant results are in boldface. Seal ID was included in the model as random effect. Den df, denominator degrees of freedom; rT3, reverse triiodothyronine; tT4, total thyroxine; tT3, total triiodothyronine; VC%, %variance described by the individual random effect.

Figure 3.

Baseline, 120 min, and 24-h serum concentrations of cortisol (A) and aldosterone (B) in adult female NESs following ACTH injection. Different numbers denote significant difference between time points, and asterisks denote significant differences between stages (P < 0.05) based on post hoc comparisons of least square means from the LMM. Green bars represent EM females (n = 12, baseline and 120 min; n = 11, 24 h), purple bars represent LM females (n = 12 baseline and 120 min; n = 7, 24 h). Horizontal bar is the mean. Whiskers are minimum and maximum values. Boxes are 25–75 percentiles. ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; EM, early molt; LM, late molt; LMM, linear mixed model; NESs, northern elephant seals.

Aldosterone concentrations increased relative to baseline by 30 min and remained elevated through 120 min sampling (F4,92 = 192.68, P < 0.001, Fig. 1B). When the magnitude of the aldosterone response to life history stages were compared, AUCald was greater in LM females than EM females (t = 2.27, df = 22, P = 0.03). Fat reserves also showed a weak negative association with AUCald response (r2 = 0.18, F1,22 = 4.82, P = 0.04, Fig. 2B). For evaluation of differences between pre, 120-min, and 24-h samples, aldosterone concentrations varied between time points and stages (Table 2, Fig. 3B). Aldosterone concentrations were higher at 120 min and returned to baseline at 24 h in both groups. AUCald showed a strong positive association with AUCcort (r2 = 0.31, F1,22 = 10.00, P = 0.0005). The slope of the relationship between AUCs was greater in EM females compared with LM females (ANCOVA; F1,20 = 4.64, P = 0.04).

ACTH injection also elicited significant changes to total T4 concentrations (Table 2, Fig. 4A). tT4 levels increased by 17% from baseline at 120 min, then showed a 21% decrease relative to baseline at 24 h post-ACTH. EM females had higher tT4 concentrations at 120 min postinjection than LM females. Total T3 concentrations were strongly impacted by the ACTH challenge (Table 2, Fig. 4B). On average, tT3 was elevated 13% above baseline at 120 min, then suppressed 23% at 24 h relative to baseline. rT3 levels were also significantly altered by the ACTH challenge (Table 2, Fig. 4C) by showing a delayed 49% increase from baseline at 24 h post-ACTH injection (P < 0.05). EM females had higher rT3 concentrations at 24 h post-injection than LM females (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Pre-ACTH, 2 h, and 24-h serum concentrations of total thyroxine (tT4) (A), total triiodothyronine (tT3) (B), and reverse triiodothyronine (rT3) (C) in adult female NESs following ACTH injection. Different numbers denote significant differences between time points, and an asterisk denotes a significant difference between stages (P < 0.05) based on post hoc comparisons of least square means from the LMM. Green bars represent EM females (n = 12, baseline and 120 min; n = 11, 24 h), purple bars represent LM females (n = 12 baseline and 120 min; n =7, 24 h). Horizontal bar is the mean. Whiskers are minimum and maximum values. Boxes are 25–75 percentiles. ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; EM, early molt; LM, late molt; LMM, linear mixed model; NESs, northern elephant seals.

Metabolite Response to ACTH

Glucose levels increased relative to baseline at 120 min in response to ACTH injection, then declined below baseline at 24 h (Table 3, Fig. 5A) in both EM and LM. Furthermore, a significant stage × time interaction in the LMM showed that glucose levels were higher in LM females at every time point (Table 3). Cortisol AUC was strongly associated with glucose concentrations at 120 min (i2 = 0.67, F1,23 = 44.4, P < 0.001). Conversely, lactate concentrations decreased relative to baseline at 120 min in response to ACTH injection and then returned to baseline at 24 h postinjection (Table 3, Fig. 5B). Cortisol AUC was associated with lactate concentrations at 120 min (r2 = 0.33, F1,23 = 10.9, P = 0.003). A significant stage × time interaction in the LMM showed that lactate levels were higher in LM females at baseline and 120 min postinjection (Table 3). BUN did not change in response to ACTH at 120 min but declined at 24 h in both life-history stages (Table 3, Fig. 5C). NEFA concentrations were elevated from pre-ACTH to 120 min and remained elevated at 24 h (Table 3, Fig. 5D). For ketone β-HBA concentrations, a significant increase from baseline was observed at 120 min, followed by a decrease from baseline at 24 h (Table 3, Fig. 5E) for both EM and LM. Cortisol AUC was not associated with NEFA or β-HBA concentrations at 120 min (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Results from a generalized linear model examining the effects of explanatory variables on metabolite levels

| Stage |

Time |

Stage × Time |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC% | Den df | F | P | Den df | F | P | Den df | F | P | |

| Glucose | 73.7 | 21.66 | 13.90 | 0.001 | 39.76 | 56.08 | <0.0001 | 39.76 | 4.06 | 0.03 |

| Lactate | 59.5 | 21.36 | 5.40 | 0.03 | 37.93 | 18.06 | <0.0001 | 37.93 | 3.98 | 0.03 |

| BUN | 71.7 | 22.28 | 3.62 | 0.07 | 38.61 | 19.05 | <0.0001 | 38.61 | 0.90 | 0.41 |

| NEFA | 69.3 | 22.11 | 9.79 | 0.005 | 38.49 | 10.48 | 0.0002 | 38.49 | 2.92 | 0.07 |

| β-HBA | 21.9 | 20.07 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 37.95 | 9.03 | 0.0006 | 37.95 | 2.26 | 0.12 |

| IL-1β | 86.6 | 22.18 | 0.19 | 0.67 | 38.31 | 9.92 | 0.0003 | 38.31 | 0.30 | 0.74 |

| IL-6 | 99.6 | 22.01 | 1.79 | 0.20 | 38.01 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 38.01 | 0.60 | 0.56 |

| IgM | 72.1 | 20.87 | 8.35 | 0.0009 | 37.19 | 2.54 | 0.09 | 37.19 | 0.21 | 0.82 |

| IgG | 88.2 | 21.98 | 3.54 | 0.07 | 38.10 | 3.37 | 0.04 | 38.10 | 0.89 | 0.42 |

Stage represents early molt (EM) and late molt (LM) groups, time represents pre, 120 min, and 24-h time points. Statistically significant results are in boldface. Seal ID was included in the model as a random effect. β-HBA, β-hydroxybutyrate; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; den df, denominator degrees of freedom; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acids; VC%, %variance described by the individual random effect.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of pre-ACTH, 2 h, and 24 h concentrations of glucose (A), lactate (B), BUN (C), NEFA (D), and β-HBA (E) in adult female NESs following ACTH injection. Different numbers denote significant difference between time points, and asterisks denote significant differences between stages (P < 0.05) based on post hoc comparisons of least square means from the LMM. Green bars represent EM females (n = 12, baseline and 120 min; n = 11, 24 h), purple bars represent LM females (n = 12 baseline and 120 min; n = 7, 24 h). Horizontal bar is the mean. Whiskers are minimum and maximum values. Boxes are 25–75 percentiles. ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; β-HBA, β-hydroxybutyrate; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; EM, early molt; LM, late molt; LMM, linear mixed model; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acids; NESs, northern elephant seals.

Immune Response to ACTH

IL-1β concentrations did not change relative to baseline at 120 min. Still, they were strongly suppressed by 37% at 24 h postinjection (P < 0.05, Table 3, Fig. 6A). IL-6 levels did not show significant changes from baseline at any time point in response to ACTH (Table 3, Fig. 6B). Baseline IgM was higher in LM females but also showed no alterations in response to ACTH challenge (Table 3, Fig. 6C). IgG levels increased relative to baseline at 120 min and returned to baseline at 24 h postinjection (Table 3, Fig. 6D) in both life history stages.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of pre-ACTH, 2 h, and 24 h concentrations of IL-1β (A), IL-6 (B), IgM (C), and IgG (D) in adult female NESs following ACTH injection. Different numbers denote significant difference between time points (P < 0.05) based on post hoc comparisons of least square means from the LMM. Green bars represent EM females (n = 12, baseline and 120 min; n = 11, 24 h), purple bars represent LM females (n = 12 baseline and 120 min; n = 7, 24 h). Horizontal bar is the mean. Whiskers are minimum and maximum values. Boxes are 25–75 percentiles. ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; EM, early molt; IgG, total immunoglobulin G; IgM, total immunoglobulin M; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; LM, late molt; LMM, linear mixed model; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acids; NESs, northern elephant seals.

DISCUSSION

Animals may be more sensitive to stressors during specific life-history stages, and physiological responses may be altered due to life-history stage (56). Our data suggest that female NESs have greater HPA axis responsiveness at the end of their molting period as shown by a substantially greater cortisol and aldosterone response to identical doses of ACTH. The strong inverse relationship between the release of stress hormones and body reserves (fat mass) suggests that fasting reduction in body condition is an important driver of adrenal responsiveness to ACTH. These data indicate that the initial phase of the foraging migration following molting is a life-history stage where animals may be more sensitive to additional or subsequent stressors. Across life-history stages, individuals with lower body conditions may mount greater stress responses than conspecifics with greater body conditions. This finding has important implications for the understanding of anthropogenic stressor impacts and how they might interact with life-history patterns and variation in foraging success related to ocean climate. This finding directly informs the attempt to integrate allostatic load and stress hormones into population models that have previously largely been based on body condition (e.g., PCoMS). A potential mechanism for this effect is the well-established effects of adipokines, especially leptin, on inhibiting adrenal steroidogenesis (57). Previous work on leptin in female NESs revealed positive associations of leptin with adiposity but not cortisol concentrations, whereas adiponectin was negatively associated with cortisol (58). Future studies should explore the relationship of a suite of adipokines on adrenal responsiveness in NESs.

In contrast, no changes in adrenal responsiveness to ACTH were evident in previous studies in molting juveniles, where AUC for cortisol and aldosterone were similar across the molt despite wide variation in baseline concentrations (32). That study sample included both females and males. This difference may reflect the higher proportional adipose reserves of juveniles (59), the reduced surface area and nutrient demands for pelage synthesis, or age-related changes associated with prior breeding fasts or intrinsic stress exposure in adult females. Differentiating these hypotheses would be facilitated by similar comparisons across breeding fasts and with wider variation in age classes. Baseline cortisol levels and cortisol responses to ACTH challenge were highly variable in LM animals, reflecting substantial individual variation in adrenal responsiveness to ACTH. Together these differences suggest pronounced life-history and individual variation in the effects of intrinsic stressors on responses to subsequent stressors.

Both study groups showed cortisol levels that remained highly elevated above baseline at 24 h post-ACTH injection, indicating a sustained adrenal response to an acute dose of ACTH. Adult male NESs showed a similar sustained response (48-h postinjection) early in the breeding season. However, this feature was not evident after several months of fasting (31). This difference may reflect the adaptive need for sustained cortisol release during the high levels of combat and activity in males during early breeding. In contrast, in repeated ACTH challenges in juvenile NESs that were not molting, cortisol concentrations consistently returned to baseline by 24 h post-ACTH injection (60). In juveniles, this life-history stage is associated with lower energy and nutrient demands (61). These differences may reflect differences in cortisol metabolism or changes in the dose-response curve resulting in longer responses. Together, these important differences suggest substantial life-history variation in HPA axis negative feedback and the duration of cortisol response to an acute stressor. The physiological impacts of single acute stress exposure may be greater in adult females.

ACTH stimulation affected aldosterone levels in both study groups, further demonstrating that aldosterone is part of the acute stress response in marine mammals. In response to low blood pressure, aldosterone is responsible for the renal reabsorption of sodium and water, benefiting a fasting state (62). Given that marine mammals incidentally ingest salt water while foraging and exist in a hyperosmotic environment, their ability to regulate aldosterone levels during stress is essential (10). Aldosterone and cortisol were positively associated, suggesting parallel synthesis and release in response to the challenge. In juvenile NESs, the relationship between cortisol and aldosterone concentrations after ACTH challenge varied by molting stage and was lower late in the molt fast compared with early in the molt fast (32). An identical pattern was found in the current study suggesting reduced aldosterone responsiveness to ACTH when the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system has been activated by fasting. The lack of a sustained aldosterone response at 24 h indicates stronger negative feedback in response to sustained stress, similar to that observed in adult male NESs (31).

Cortisol affects the production of thyroid hormones through modulating deiodination (63). After the ACTH injection, we observed a small transient upregulation of tT3, which has been documented as an acute stress response in rats but not in marine mammals (64–66). Increased metabolism in response to stress may be adaptive for escape behavior. Sustained stress downregulated tT3 and upregulated rT3 at 24 h post-ACTH, emphasizing the influence of cortisol on deiodinase enzyme transcription. Adult male NESs showed a similar suppression of tT3 and upregulation of rT3 following stress during breeding. These associations are held for juvenile NESs at various life-history stages (31, 37). A noteworthy difference is that our experiment also elicited elevated tT4 concentrations in response to acute stress, then suppression with sustained stress. Associations between cortisol and tT4 have not been documented in NESs, including adult male NESs (31) or juvenile NESs (37) but have been observed in other marine mammals. Disturbance at rookeries elicited decreases in tT3 and tT4 in Steller sea lion pups (67). Free-ranging beluga whales showed similar thyroid suppression within 24 h following capture (65). In our study, deiodinase enzymes likely converted tT4 into rT3, while sustained stress at 24 h likely suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone release. tT3 has been shown to stimulate erythropoietin production and erythroid precursors in rats (68, 69) and protect against reperfusion injury, and increase post-ischemic tissue functions (70). Conversely, hyperthyroidism decreased dive duration in harbor seals (71). Together these findings suggest the potential for complex effects of at-sea stress responses on breath-hold ability in foraging seals that are exercising and increasing blood stores under the condition of extreme hypoxemia (72, 73).

Cortisol stimulates gluconeogenesis which uses lactate, glycerol, and amino acids as substrates for glucose synthesis. Lactate has been suggested as the primary gluconeogenic substrate in fasting NESs (74). We saw an increase in glucose concentrations and a corresponding decrease in lactate concentrations that was associated with the magnitude of cortisol release. LM animals had higher baseline glucose levels than EM animals (Table 3). LM individuals likely showed a greater gluconeogenic effect of cortisol than EM individuals because of the need for glucose for skin and pelage synthesis during the molt. Previous studies on fasting phocids have shown that protein stores are generally spared while most energetic demands are met through the oxidation of fatty acids (75). Baseline BUN levels in our study were double of those seen in yearling NESs at corresponding life history stages, and half of those observed in adult male NESs, implying that BUN varies with body size and is related to the amount of glucose needed for skin synthesis (31, 32). Our observed suppression of BUN values at 24 h post-ACTH (Fig. 5C) is consistent with previous observations that, in fasting NESs, cortisol does not follow the traditional model of enhancing protein catabolism (76). Amino acids were not likely being used for enhanced gluconeogenesis; instead, cortisol may have stimulated glucose production from lactate. Studies using cell culture of elephant seal myocytes found that cortisol stimulated enhanced glycolysis but prevented the entrance of glucose carbon into the TCA cycle, consistent with recycling of glucose through the Cori cycle (77). Together these findings suggest that cortisol may enhance glucose recycling in elephant seals.

Concurrent with an increase in NEFA at 120 min, we observed an acute elevation of ketone β-HBA (Fig. 5, D and E), indicating enhanced lipolysis in response to acute stress but not chronic stress. Phocid skeletal muscles have been shown to maintain aerobic lipid-based metabolism while diving (78, 79). Thus, mobilizing NEFA in response to stress may have adaptive significance through enhanced replenishment of muscle lipid stores and diving ability. Diminished ketone levels 24 h post-ACTH indicate a reduction in β-oxidation of fatty acids. Adult male NESs have also shown modest increases of ketone β-HBA during the molt with acute stress (31). Avoidance of ketone accumulation in NESs suggests a tight coupling of β-oxidation and tricarboxylic acid cycle (76, 80). Overall, cortisol increased glucose without catabolizing protein and enhanced lipid mobilization and use. Similar to adult male NESs, cortisol is a key modulator of fasting metabolism in adult female NESs during molting.

Many studies in wildlife and model systems show immunosuppression in response to glucocorticoid treatment or sustained stress (81–83). However, acute stress may also stimulate some aspects of immune function (81). These contrasting trends highlight the importance of understanding the potential additive effects of stressors on immunocompetence (84). In our study, IL-1β was suppressed by nearly half in response to sustained stress (Fig. 5F). This delayed effect at 24 h aligns with the general trend that cortisol suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine release; however, cytokine IL-6 did not follow this trend. Conversely, some studies report positive associations between acute stress and IL-1β levels in humans (85, 86), whereas a different study reports no association (85). A sizeable cross-sectional data set with adult female NESs previously found no relationship between baseline cortisol and IL-1β or IL-6 in adult female NESs (50). Our data suggest that IL-1β shows substantial alterations in response to sustained stress but not acute stress in adult female NESs.

Previous work in adult female elephant seals (50) described IgG levels that remained stable across the molt in adult female NESs. Our observed increase in IgG concentrations under acute cortisol elevation may be associated with enhanced glucose availability for seroconversion. Glucose metabolism is a critical factor driving IgG seroconversion in humans and laboratory animals when IgG antibodies can be detected in the blood (87, 88). Glucose and IgG are associated with Californian sea lion pups (89), and a study with South American fur seals showed that a sustained, targeted stress response from parasite loads may aid in mobilizing glucose for a strong immune response against infection (90). The rapid and sustained increase in IgG concentrations after ACTH injection concurrent with an elevation in plasma glucose suggests an important role for glucose in enhancing seroconversion of IgG in NESs.

It is important to note that despite higher serum cortisol release in response to identical ACTH stimulation, the physiological impacts of cortisol rarely varied between life history stages, as evidenced by a stage-by-time point interaction. The exceptions were apparent gluconeogenesis from lactate and enhanced production of the thyroid receptor blocker rT3 late in the molt fast. This lack of a stage-by-time interaction may be a result of our small sample size, especially at the 24 h post-ACTH sample. Alternatively, this suggests important modulation of cortisol effects at the receptor and gene expression level. Previous investigations of repeated ACTH stimulation effects on the blubber proteome and transcriptome in juveniles suggested alterations in gene expression despite similar elevations in cortisol in response to sustained stress. The number of differentially expressed genes relative to baseline declined with repeated stress. Different genes were expressed or downregulated in response to the repeated challenges (91, 92). Similarly, cross-sectional studies in unmanipulated juveniles suggested strong associations of gene expression with baseline concentrations of cortisol and thyroid hormones (93). The natural elevation in cortisol that occurs across the molt fast may help to dampen the physiological impacts of an acute stress response despite enhanced adrenal responsiveness associated with reduced body condition, resulting in more consistent physiological impacts relative to ACTH release by the HPA axis.

Perspectives and Significance

We evaluated the effect of a simulated stressor on HPA axis responsiveness, thyroid, and immune function, and metabolic analytes in a capital breeding marine mammal at the beginning and end of an energy-intensive molt fast. Our study suggests that the intrinsic stress of natural fasting can potentially change adrenal responsiveness to subsequent anthropogenic and environmental stressors in a top marine predator. Body reserves were associated with the magnitude of the cortisol and aldosterone responses, and adrenal responsiveness to ACTH was much greater after the molt fast. Impacts of ACTH stimulation on thyroid hormones and immune analytes suggested significant regulatory impacts of cortisol on metabolism and immune function. These findings indicate that it is critical to consider intrinsic life history stress interactions with subsequent stressors and that contextual information on life-history stage and body condition is needed to assess the potential impacts of those stressors on animal health.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Source data are available at doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.21433422.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) Research Award RC20-C2-1284 (to D. P. Costa and D. E. Crocker).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.D.N., D.P.C., and D.E.C. conceived and designed research; A.D.N., R.R.H., G.T.S., and D.E.C. performed experiments; A.D.N., G.T.S., and D.E.C. analyzed data; A.D.N. and D.E.C. interpreted results of experiments; A.D.N. and D.E.C. prepared figures; A.D.N. drafted manuscript; A.D.N., R.R.H., G.T.S., D.P.C., and D.E.C. edited and revised manuscript; A.D.N., R.R.H., G.T.S., D.P.C., and D.E.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank P. Robinson and University of California Santa Cruz’s Año Nuevo State Reserve for facilitating access to the animals and E. Sperou, C. Rzucidlo, and E. DeRango for assistance with sample collection.

REFERENCES

- 1. Crespi EJ, Williams TD, Jessop TS, Delehanty B. Life history and the ecology of stress: how do glucocorticoid hormones influence life‐history variation in animals? Funct Ecol 27: 93–106, 2013. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Killen SS, Marras S, Metcalfe NB, McKenzie DJ, Domenici P. Environmental stressors alter relationships between physiology and behaviour. Trends Ecol Evol 28: 651–658, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gill JA, Norris K, Sutherland WJ. Why behavioural responses may not reflect the population consequences of human disturbance. Biol Conserv 97: 265–268, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00002-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ellis RD, McWhorter TJ, Maron M. Integrating landscape ecology and conservation physiology. Landscape Ecol 27: 1–12, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10980-011-9671-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wikelski M, Cooke SJ. Conservation physiology. Trends Ecol Evol 21: 38–46, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maxwell SM, Hazen EL, Bograd SJ, Halpern BS, Breed GA, Nickel B, Teutschel NM, Crowder LB, Benson S, Dutton PH, Bailey H, Kappes MA, Kuhn CE, Weise MJ, Mate B, Shaffer SA, Hassrick JL, Henry RW, Irvine L, McDonald BI, Robinson PW, Block BA, Costa DP. Cumulative human impacts on marine predators. Nat Commun 4: 1–9, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Approaches to Understanding the Cumulative Effects of Stressors on Marine Mammals. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pirotta E, Booth CG, Costa DP, Fleishman E, Kraus SD, Lusseau D, Moretti D, New LF, Schick RS, Schwarz LK, Simmons SE, Thomas L, Tyack PL, Weise MJ, Wells RS, Harwood J. Understanding the population consequences of disturbance. Ecol Evol 8: 9934–9946, 2018. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Keen KA, Beltran RS, Pirotta E, Costa DP. Emerging themes in population consequences of disturbance models. Proc Biol Sci B 288: 20210325, 2021. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2021.0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Atkinson S, Crocker D, Houser D, Mashburn K. Stress physiology in marine mammals: how well do they fit the terrestrial model? J Comp Physiol B 185: 463–486, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00360-015-0901-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McEwen B, Wingfield J. Allostasis and allostatic load. In: Encyclopedia of Stress, ed, G. Fink. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2007, p. 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Landys MM, Ramenofsky M, Wingfield JC. Actions of glucocorticoids at a seasonal baseline as compared to stress-related levels in the regulation of periodic life processes. Gen Comp Endocrinol 148: 132–149, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions 1. Endocr Rev 21: 55–89, 2000. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wikelski M, Wong V, Chevalier B, Rattenborg N, Snell HL. Marine iguanas die from trace oil pollution. Nature 417: 607–608, 2002. doi: 10.1038/417607a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Romero LM. Seasonal changes in plasma glucocorticoid concentrations in free-living vertebrates. Gen Comp Endocrinol 128: 1–24, 2002. doi: 10.1016/s0016-6480(02)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Madliger CL, Love OP. The need for a predictive, context‐dependent approach to the application of stress hormones in conservation. Conserv Biol 28: 283–287, 2014. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brander KM. Global fish production and climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 19709–19714, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702059104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meltzer E. Global overview of straddling and highly migratory fish stocks: the nonsustainable nature of high seas fisheries. Ocean Develop Int Law 25: 255–344, 1994. doi: 10.1080/00908329409546036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nowacek SM, Wells RS, Solow AR. Short-term effects of boat traffic on bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus, in Sarasota Bay, Florida. Marine Mammal Sci 17: 673–688, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01292.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tanabe S. Contamination and toxic effects of persistent endocrine disrupters in marine mammals and birds. Mar Pollut Bull 45: 69–77, 2002. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(02)00175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rolland RM, Parks SE, Hunt KE, Castellote M, Corkeron PJ, Nowacek DP, Wasser SK, Kraus SD. Evidence that ship noise increases stress in right whales. Proc Biol Sci 279: 2363–2368, 2012. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trana MR, Roth JD, Tomy GT, Anderson WG, Ferguson SH. Increased blubber cortisol in ice-entrapped beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas). Polar Biol 39: 1563–1569, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00300-015-1881-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Trumble SJ, Norman SA, Crain DD, Mansouri F, Winfield ZC, Sabin R, Potter CW, Gabriele CM, Usenko S. Baleen whale cortisol levels reveal a physiological response to 20th century whaling. Nat Commun 9: 1–8, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07044-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chinn SM, Monson DH, Tinker MT, Staedler MM, Crocker DE. Lactation and resource limitation affect stress responses, thyroid hormones, immune function, and antioxidant capacity of sea otters (Enhydra lutris). Ecol Evol 8: 8433–8447, 2018. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DeRango EJ, Prager KC, Greig DJ, Hooper AW, Crocker DE. Climate variability and life history impact stress, thyroid, and immune markers in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) during El Niño conditions. Conserv Physiol 7: coz010, 2019. doi: 10.1093/conphys/coz010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. DeRango EJ, Greig DJ, Gálvez C, Norris TA, Barbosa L, Elorriaga‐Verplancken FR, Crocker DE. Response to capture stress involves multiple corticosteroids and is associated with serum thyroid hormone concentrations in Guadalupe fur seals (Arctocephalus philippii townsendi). Mar Mam Sci 35: 72–92, 2019. doi: 10.1111/mms.12517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thomson CA, Geraci JR. Cortisol, aldosterone, and leucocytes in the stress response of bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 43: 1010–1016, 1986. doi: 10.1139/f86-125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gulland F, Haulena M, Lowenstine LJ, Munro C, Graham P, Bauman J, Harvey J. Adrenal function in wild and rehabilitated pacific harbor seals (Phoca vitulina richardii) and in seals with phocine herpesvirus‐associated adrenal necrosis. Marine Mammal Sci 15: 810–827, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00844.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Keogh MJ, Atkinson S. Endocrine and immunological responses to adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) administration in juvenile harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) during winter and summer. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 188: 22–31, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mashburn KL, Atkinson S. Variability in leptin and adrenal response in juvenile Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in different seasons. Gen Comp Endocrinol 155: 352–358, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ensminger DC, Somo DA, Houser DS, Crocker DE. Metabolic responses to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) vary with life-history stage in adult male northern elephant seals. Gen Comp Endocrinol 204: 150–157, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Champagne C, Tift M, Houser D, Crocker D. Adrenal sensitivity to stress is maintained despite variation in baseline glucocorticoids in moulting seals. Conserv Physiol 3: cov004, 2015. doi: 10.1093/conphys/cov004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Danforth E Jr, Burger A. The role of thyroid hormones in the control of energy expenditure. Clin Endocrinol Metab 13: 581–595, 1984. doi: 10.1016/s0300-595x(84)80039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Charmandari E, Tsigos C, Chrousos G. Endocrinology of the stress response 1. Annu Rev Physiol 67: 259–284, 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.120816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bianco AC, Kim BW. Deiodinases: implications of the local control of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest 116: 2571–2579, 2006. doi: 10.1172/JCI29812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Helmreich DL, Tylee D. Thyroid hormone regulation by stress and behavioral differences in adult male rats. Horm Behav 60: 284–291, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jelincic J, Tift M, Houser D, Crocker D. Variation in adrenal and thyroid hormones with life-history stage in juvenile northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris). Gen Comp Endocrinol 252: 111–118, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haddad JJ, Saadé NE, Safieh-Garabedian B. Cytokines and neuro–immune–endocrine interactions: a role for the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal revolving axis. J Neuroimmunol 133: 1–19, 2002. [Erratum in J Neuroimmunol 145: 154, 2003]. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Khansari DN, Murgo AJ, Faith RE. Effects of stress on the immune system. Immunol Today 11: 170–175, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90069-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sheldon BC, Verhulst S. Ecological immunology: costly parasite defences and trade-offs in evolutionary ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 11: 317–321, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Råberg L, Grahn M, Hasselquist D, Svensson E. On the adaptive significance of stress-induced immunosuppression. Proc Biol Sci 265: 1637–1641, 1998. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bauer ME. Chronic stress and immunosenescence: a review. Neuroimmunomodulation 15: 241–250, 2008. doi: 10.1159/000156467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Davis A, Maney D, Maerz J. The use of leukocyte profiles to measure stress in vertebrates: a review for ecologists. Funct Ecol 22: 760–772, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01467.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Houser DS, Yeates LC, Crocker DE. Cold stress induces an adrenocortical response in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). J Zoo Wildl Med 42: 565–571, 2011. doi: 10.1638/2010-0121.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Crocker DE, Champagne CD, Fowler MA, Houser DS. Adiposity and fat metabolism in lactating and fasting northern elephant seals. Adv Nutr 5: 57–64, 2014. doi: 10.3945/an.113.004663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Worthy GAJ, Morris PA, Costa DP, Le Boeuf BJ. Moult energetics of the northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris). J Zool Lond 227: 257–265, 1992. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb04821.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Champagne CD, Houser DS, Costa DP, Crocker DE. The effects of handling and anesthetic agents on the stress response and carbohydrate metabolism in northern elephant seals. PloS One 7: e38442, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Khudyakov JI, Champagne CD, Preeyanon L, Ortiz RM, Crocker DE. Muscle transcriptome response to ACTH administration in a free-ranging marine mammal. Physiol Genomics 47: 318–330, 2015. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00030.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Champagne CD, Houser DS, Crocker DE. Glucose production and substrate cycle activity in a fasting adapted animal, the northern elephant seal. J Exp Biol 208: 859–868, 2005. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Peck HE, Costa DP, Crocker DE. Body reserves influence allocation to immune responses in capital breeding female northern elephant seals. Funct Ecol 30: 389–397, 2016. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ortiz CL, Costa DP, Le Boeuf BJ. Water and energy flux in elephant seal pups fasting under natural conditions. Physiol Zool 51: 166–178, 1978. doi: 10.1086/physzool.51.2.30157864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nagy KA, Dp C. Water flux in animals: an analysis of potential errors in the tritiated water method. Am J Physiol 238: R446–R473, 1980. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1980.238.5.R454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reilly JJ, Fedak MA. Measurement of the body composition of living gray seals by hydrogen isotope dilution. J Appl Physiol (1985) 69: 885–891, 1990. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.3.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bowen WD, Iverson SJ. Estimation of total body water in pinnipeds using hydrogen‐isotope dilution. Physiol Zool 71: 329–332, 1998. doi: 10.1086/515921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Iverson SJ, Bowen WD, Boness DJ, Oftedal OT. The effect of maternal size and milk energy output on pup growth in grey seals (Halichoerus grypus). Physiol Zool 66: 61–88, 1993. doi: 10.1086/physzool.66.1.30158287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dantzer B, Westrick SE, van Kesteren F. Relationships between endocrine traits and life histories in wild animals: insights, problems, and potential pitfalls. Integr Comp Biol 56: 185–197, 2016. doi: 10.1093/icb/icw051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bornstein SR, Uhlmann K, Haidan A, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Scherbaum WA. Evidence for a novel peripheral action of leptin as a metabolic signal to the adrenal gland: leptin inhibits cortisol release directly. Diabetes. 46: 1235–1238, 1997. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.7.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rzucidlo CL, Sperou ES, Holser RR, Khudyakov JI, Costa DP, Crocker DE. Changes in serum adipokines during natural extended fasts in female northern elephant seals. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 308: 113760, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2021.113760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Webb PM, Crocker DE, Blackwell SB, Costa DP, Boeuf BJ. Effects of buoyancy on the diving behavior of northern elephant seals. J Exp Biol 201: 2349–2358, 1998. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.16.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McCormley MC, Champagne CD, Deyarmin JS, Stephan AP, Crocker DE, Houser DS, Khudyakov JI. Repeated adrenocorticotropic hormone administration alters adrenal and thyroid hormones in free-ranging elephant seals. Conserv Physiol 6: coy040, 2018. doi: 10.1093/conphys/coy040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kelso EJ, Champagne CD, Tift MS, Houser DS, Crocker DE. Sex differences in fuel use and metabolism during development in fasting juvenile northern elephant seals. J Exp Biol 215: 2637–2645, 2012. doi: 10.1242/jeb.068833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ortiz RM, Adams SH, Costa DP, Ortiz CL. Plasma vasopressin levels and water conservation in fasting postweaned northern elephant seal pups (Mirounga angustirostris). Marine Mammal Sci 12: 99–106, 1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1996.tb00307.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Surks MI, Schadlow AR, Stock JM, Oppenheimer JH. Determination of iodothyronine absorption and conversion of L-thyroxine (T 4) to L-triiodothyronine (T 3) using turnover rate techniques. J Clin Invest 52: 805–811, 1973. doi: 10.1172/JCI107244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Friedman Y, Bacchus R, Raymond R, Joffe RT, Nobrega JN. Acute stress increases thyroid hormone levels in rat brain. Biol Psychiatry 45: 234–237, 1999. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. St. Aubin DJ, Geraci JR. Capture and handling stress suppresses circulating levels of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) in beluga whales Delphinapterus leucas. Physiol Zool 61: 170–175, 1988. doi: 10.1086/physzool.61.2.30156148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Champagne CD, Kellar NM, Trego ML, Delehanty B, Boonstra R, Wasser SK, Booth RK, Crocker DE, Houser DS. Comprehensive endocrine response to acute stress in the bottlenose dolphin from serum, blubber, and feces. Gen Comp Endocrinol 266: 178–193, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Keogh MJ, Atkinson S, Maniscalco JM. Body condition and endocrine profiles of Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus) pups during the early postnatal period. Gen Comp Endocrinol 184: 42–50, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Peschle C, Zanjani ED, Gidari AS, Mclaurin WD, Gordon AS. Mechanism of thyroxine action on erythropoiesis. Endocrinology 89: 609–612, 1971. doi: 10.1210/endo-89-2-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dainiak N, Hoffman R, Maffei LA, Forget BG. Potentiation of human erythropoiesis in vitro by thyroid hormone. Nature 272: 260–262, 1978. doi: 10.1038/272260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pantos C, Mourouzis I, Saranteas T, Brozou V, Galanopoulos G, Kostopanagiotou G, Cokkinos DV. Acute T3 treatment protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury via TRα1 receptor. Mol Cell Biochem 353: 235–241, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0791-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Weingartner G, Thornton SJ, Andrews RA, Ensitipp MR, Barts AD, Hochachka PW. The effects of experimentally induced hyperthyroidism on the diving physiology of harbor seals (Phoca vitulina). Front Physiol 3: 380, 2012. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hassrick JL, Crocker DE, Teutschel NM, McDonald BI, Robinson PW, Simmons SE, Costa DP. Condition and mass impact oxygen stores and dive duration in adult female northern elephant seals. J Exp Biol 213: 585–592, 2010. doi: 10.1242/jeb.037168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Meir JU, Champagne CD, Costa DP, Williams CL, Ponganis PJ. Extreme hypoxemic tolerance and blood oxygen depletion in diving elephant seals. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R927–R939, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00247.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Tavoni S, Champagne C, Houser D, Crocker D. Lactate flux and gluconeogenesis in fasting, weaned northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris). J Comp Physiol B 183: 537–546, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00360-012-0720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Crocker DE, Webb PM, Costa DP, Le Boeuf BJ. Protein catabolism and renal function in lactating northern elephant seals. Physiol Zool 71: 485–491, 1998. doi: 10.1086/515971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Champagne CD, Houser DS, Fowler MA, Costa DP, Crocker DE. Gluconeogenesis is associated with high rates of tricarboxylic acid and pyruvate cycling in fasting northern elephant seals. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 303: R340–R352, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00042.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Torres-Velarde JM, Kolora SRR, Khudyakov JI, Crocker DE, Sudmant PH, Vázquez-Medina JP. Elephant seal muscle cells adapt to sustained glucocorticoid exposure by shifting their metabolic phenotype. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 321: R413–R428, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00052.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kanatous SB, Davis RW, Watson R, Polasek L, Williams TM, Mathieu-Costello O. Aerobic capacities in the skeletal muscles of Weddell seals: key to longer dive durations? J Exp Biol 205: 3601–3608, 2002. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.23.3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Reed JZ, Butler PJ, Fedak MA. The metabolic characteristics of the locomotory muscles of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus), harbour seals (Phoca vitulina), and antarctic fur seals (Arctocephalus gazella). J Exp Biol 194: 33–46, 1994. doi: 10.1242/jeb.194.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Houser DS, Crocker DE, Tift MS, Champagne CD. Glucose oxidation and nonoxidative glucose disposal during prolonged fasts of the northern elephant seal pup (Mirounga angustirostris). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 303: R562–R570, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00101.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Dhabhar FS. Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol Res 58: 193–210, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8517-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Demas GE, Adamo SA, French SS. Neuroendocrine‐immune crosstalk in vertebrates and invertebrates: implications for host defence. Funct Ecol 25: 29–39, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01738.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tait AS, Butts CL, Sternberg EM. The role of glucocorticoids and progestins in inflammatory, autoimmune, and infectious disease. J Leukoc Biol 84: 924–931, 2008. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0208104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Acevedo-Whitehouse K, Duffus AL. Effects of environmental change on wildlife health. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 364: 3429–3438, 2009. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Heinz A, Hermann D, Smolka MN, Rieks M, Gräf K-J, Pöhlau D, Kuhn W, Bauer M. Effects of acute psychological stress on adhesion molecules, interleukins and sex hormones: implications for coronary heart disease. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 165: 111–117, 2003. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Altemus M, Rao B, Dhabhar FS, Ding W, Granstein RD. Stress-induced changes in skin barrier function in healthy women. J Invest Dermatol 117: 309–317, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mohammed N, Tang L, Jahangiri A, de Villiers W, Eckhardt E. Elevated IgG levels against specific bacterial antigens in obese patients with diabetes and in mice with diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance. Metabolism 61: 1211–1214, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Palmer CS, Ostrowski M, Balderson B, Christian N, Crowe SM. Glucose metabolism regulates T cell activation, differentiation, and functions. Front Immunol 6: 1, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Banuet-Martínez M, Espinosa-de Aquino W, Elorriaga-Verplancken FR, Flores-Morán A, García OP, Camacho M, Acevedo-Whitehouse K. Climatic anomaly affects the immune competence of California sea lions. PloS One 12: e0179359, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Seguel M, Perez-Venegas D, Gutierrez J, Crocker DE, DeRango EJ. Parasitism elicits a stress response that allocates resources for immune function in South American fur seals (Arctocephalus australis). Physiol Biochem Zool 92: 326–338, 2019. doi: 10.1086/702960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Deyarmin JS, McCormley MC, Champagne CD, Stephan AP, Busqueta LP, Crocker DE, Houser DS, Khudyakov JI. Blubber transcriptome responses to repeated ACTH administration in a marine mammal. Sci Rep 9: 1–13, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39089-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Deyarmin J, Hekman R, Champagne C, McCormley M, Stephan A, Crocker D, Houser D, Khudyakov J. Blubber proteome response to repeated ACTH administration in a wild marine mammal. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteomics 33: 100644, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2019.100644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Pujade Busqueta L, Crocker DE, Champagne CD, McCormley MC, Deyarmin JS, Houser DS, Khudyakov JI. A blubber gene expression index for evaluating stress in marine mammals. Conserv Physiol 8: coaa082, 2020. doi: 10.1093/conphys/coaa082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Source data are available at doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.21433422.