Keywords: air-liquid interface, culture, interleukin-13, preterm, respiratory epithelium

Abstract

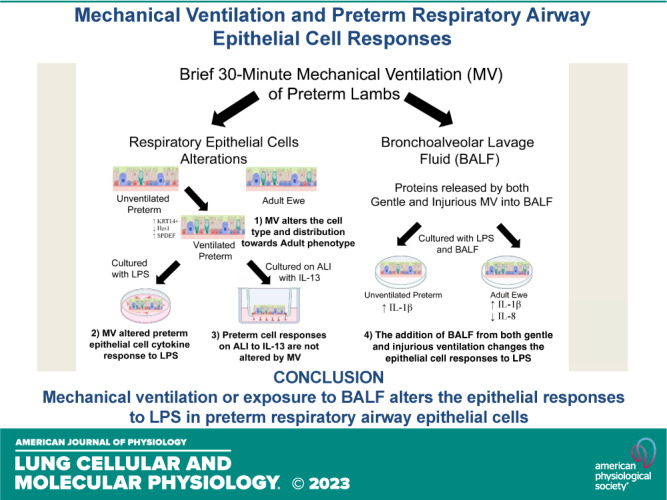

Mechanical ventilation causes airway injury, respiratory epithelial cell proliferation, and lung inflammation in preterm sheep. Whether preterm epithelial cells respond similarly to adult epithelial cells or are altered by mechanical ventilation is unknown. We test the hypothesis that mechanical ventilation alters the responses of preterm airway epithelium to stimulation in culture. Respiratory epithelial cells from the trachea, left mainstem bronchi (LMSB), and distal bronchioles were harvested from unventilated preterm lambs, ventilated preterm lambs, and adult ewes. Epithelial cells were grown in culture or on air-liquid interface (ALI) and challenged with combinations of either media only, lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10 ng/mL), bronchoalveolar fluid (BALF), or interleukin-13 (IL-13). Cell lysates were evaluated for mRNA changes in cytokine, cell type markers, Notch pathway, and acute phase markers. Mechanical ventilation altered preterm respiratory epithelium cell types. Preterm respiratory epithelial cells responded to LPS in culture with larger IL-8 induction than adults, and mechanical ventilation further increased cytokines IL-1β and IL-8 mRNA induction at 2 h. IL-8 protein is detected in cell media after LPS stimulation. The addition of BALF from ventilated preterm animals increased IL-1β mRNA to LPS (fivefold) in both preterm and adult cells and suppressed IL-8 mRNA (twofold) in adults. Preterm respiratory epithelial cells, when grown on ALI, responded to IL-13 with an increase in goblet cell mRNA. Preterm respiratory epithelial cells responded to LPS and IL-13 with responses similar to adults. Mechanical ventilation or exposure to BALF from mechanically ventilated animals alters the responses to LPS.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Preterm lamb respiratory epithelial cells can be extracted from the trachea and bronchi and frozen, and the preterm cells can respond in culture to stimulation with LPS or IL-13. Brief mechanical ventilation changes the distribution and cell type of preterm respiratory cells toward an adult phenotype, and mechanical ventilation alters the response to LPS in culture. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from preterm lambs receiving mechanical ventilation also alters unventilated preterm and adult responses to LPS.

INTRODUCTION

Long-term airway disease occurs in many extreme preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (1–3). Decreased 1-s forced expiratory volume (FEV1) measurements and increases in wheezing disorders are persistent into at least adolescence (4, 5). Increased airway reactivity, though less severe, can also be found in moderate or late preterm infants (6). Mechanical ventilation at birth leads to distention of the airways, disruptions in the epithelial barrier, and alterations in the cell type and distribution in the respiratory epithelium in preterm sheep (7–10). Even in the era of less invasive ventilator support, many extremely preterm infants unfortunately still receive large tidal volume ventilation in the delivery room (11). Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) can also increase airway reactivity in preterm murine models, and epidemiological associations with airway disease have been temporally found in preterm infants receiving prolonged CPAP therapies (3, 12). However, increased airway pressures, without mechanical ventilation, did not cause airway injury in fetal sheep (13).

The airway epithelium in the sheep closely resembles that of the human, making it a good model for evaluating airway injury at birth (10, 14). Mechanical ventilation causes airway epithelial injury, but fetal sheep have the ability to repair it if the mechanical ventilation is stopped (15, 16). Unfortunately, most preterm infants require continued respiratory support after the delivery room. The repair mechanisms in sheep resemble those found through transgenic models in rodents, although the locations are different (17–19). Cellular proliferation and differentiation are based on location in the airway: goblet cells proliferate in the trachea, basal cells proliferate in the mainstem bronchi and larger bronchi, and club cells proliferate in smaller bronchioles in preterm sheep (10). Abnormal airway remodeling and epithelial maturation may be the initial process that progresses to lifelong airway abnormalities in survivors of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) (9, 10).

Primary epithelial cell cultures have been used to study airway diseases, such as asthma, in both adult and pediatric populations (20, 21). Preterm epithelial cells have been difficult to study because preterm murine or small animal models often do not produce enough cells (22). Recent studies of respiratory epithelium from the nasal passages of preterm infants have provided additional insights into the effects of prematurity on epithelial function (23, 24).

In this study, we isolated the respiratory epithelial cells from the trachea, left mainstem bronchi, and more distal bronchi of preterm lambs at 85% gestation (∼28 wk gestation in humans) and compared these cells to those from preterm lambs receiving mechanical ventilation and cells from adult ewes. We tested the hypothesis that preterm respiratory epithelial cells would respond to stimuli differently from adult cells and that mechanical ventilation would alter the cells to respond more like adult cells. We evaluated the responses of preterm cells to Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS; a potent, sterile inducer of Toll-like receptor 2- and 4-driven inflammation), bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from mechanical ventilate lambs, and IL-13 exposure during air-liquid interface (ALI) culture.

METHODS

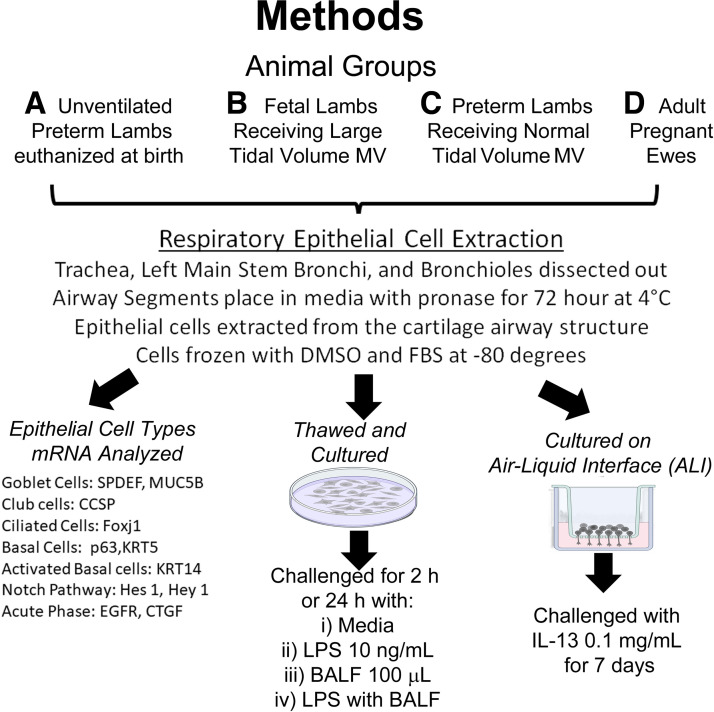

Animal experiments were performed following review and approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia. The airways from 12 lambs at 126 ± 1 days gestational age (term ∼150 days) were extracted (see extraction section) from lambs included in a larger research study (Fig. 1) (25). Before necropsy, the lambs (n = 4 or 5/group) were randomized to one of the following groups: 1) unventilated preterm lambs euthanized at birth; 2) 200 mg/kg surfactant treatment (Curosurf, Chiesi S.p.A) then ventilation for 30 min with normal tidal volumes (7–8 mL/kg; Brief VT Preterm); or 3) fetal lambs that received 15 min of injurious high tidal volume ventilation (10–15 mL/kg), followed by a 24 h in utero recovery period, then 30 min of newborn ventilation (Fetal Inj VT) (25).

Figure 1.

Schematic for methods used for experiments. [Image created with BioRender.com and published with permission.]

When reported as ventilated preterm, both Brief VT Preterm and Fetal Inj VT groups were included. The lambs were euthanized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg iv) before necropsy. After delivery of the preterm lambs, the ewe (n = 4) was euthanized and the chest was opened to extract the trachea and lung.

Extraction of Primary Lung Epithelial Cells

The trachea and the left bronchus extending into the distal lung were resected during necropsy. Peripheral lung tissues were hand dissected off the airways until no blood vessels or parenchyma were visible and placed in sterile Ham’s F-12/Penicillin/Streptomycin (26, 27). The left bronchus was separated at the level of four divisions past the tracheal bifurcation into the left mainstem bronchi (LMSB) and smaller distal bronchioles. Airway segments were treated with 0.15% pronase in media for 72 h at 4°C with gentle periodic rotations (26). After the incubation period, the epithelial cells were washed using Ham’s F-12/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cell-containing media was centrifuged at 500 g at 4°C for 10 min to obtain a pellet of epithelial cells. The cell pellets were suspended in DNase solution, centrifuged at 500 g at 4°C for 5 min, then placed in 10% DMSO and 10% FBS (26, 27). The cells were divided into 3 × 105 cells/mL aliquots, placed at −20°C briefly, before being stored at −80°C.

Cell Culture and Exposure to LPS Exposure and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid

Primary epithelial cells and second passage epithelial cells were used for all experiments. All experiments used three wells per experimental condition, and exposure experiments were repeated for consistency. Briefly, the respiratory epithelial cells were defrosted, washed, then seeded onto collagen-coated 12-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well) with BTEC media and retinoic acid (RA) (26, 27). Media were changed three times per week, and the cells were grown until reaching confluence (∼5–7 days) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Additional cells were grown to confluence in 100-mL culture vials, trypsinized, then frozen as second passage respiratory epithelial cells. Fibroblast removal using Primaria (BD Bioscience) was tested on adult ewe tracheal cells and found to not affect the response to LPS (Supplemental Table S2) in standard culture. To conserve preterm cells, fibroblast removal was not completed for some experiments. Adult ewe tracheal cells and unventilated preterm tracheal cells were challenged with E. coli O111:B4 LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) at concentrations of 10 ng/mL, 100 ng/mL, and 1,000 ng/mL to determine dosing for other experiments. Respiratory epithelial cells from the trachea, LMSB, or the distal bronchioles were then challenged with 10 ng/mL for either 2 h or 24 h. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), collected from saline lavage at necropsy from a further experiment, was used to challenge cells (28). BALF from lambs receiving 6 h of gentle ventilation (normal tidal volume of 7–8 mL/kg after intratracheal surfactant administration) or injurious ventilation (12 mL/kg, large tidal volume ventilation before surfactant treatment) was used (28). Confluent unventilated preterm and ewe LMSB cultures were challenged with either 100-µL BALF, LPS 10 ng/mL, or BALF + LPS for 2 h.

Air-Liquid Interface Culture and Exposure to IL-13

Primary tracheal and LMSB epithelial cells were plated on Primaria plates (BD Bioscience) for 30 min to remove fibroblasts, then 1 × 105 cells were transferred to the top of collagen-treated, six-well ALI Transwell plates (Corning) (29). Media were placed in the apical and basal areas and changed every other day for 1 wk, or until confluence was achieved (26, 27). Apical media were then removed and the cells were allowed to differentiate on ALI for 7 days with either media or media with IL-13 (0.1 mg/dL) in the basal layer (21, 29).

mRNA Production, RT-PCR, and IL-8 ELISA

After the challenge period ended, the cells were lysed using QIA Shredder (Qiagen), and mRNA was extracted for RT-PCR using PureLink RNA Mini kit spin cartridges. cDNA was produced using the Verso cDNA kit (Thermo Scientific) as per manufacturer’s protocols (25). Custom Taqman gene primers (Life Technologies) for ovine sequences were used to determine the relative expression of transcript for 1) cytokines: interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1); 2) cell type markers: club cell secretory protein (CCSP), Forkhead box protein J1 (FoxJ1), Keratin 5 (KRT5), KRT8, KRT14, Mucin 5B (MUC5B), p63, and SAM-Pointed Domain-Containing ETS Transcription Factor (SPDEF); 3) Notch pathway: Hes Family BHLH Transcription Factor 1 (Hes1), Hes2, and Hey2; and 4) acute phase response and other factors: epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) were used (10, 30). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in triplicate with iTaq Universal mix (Bio-Rad) on a CFX Connect (Bio-Rad). 18S primers (Life Technologies) were used as the internal loading control. Fold increases were determined by the ΔΔCq method (CFX manager, Bio-Rad). Average ΔΔCq for unventilated preterm lambs was set as 1, and group changes were reported as fold increases over unventilated preterm lambs for primary cell types. For culture experiments, the average ΔΔCq for cells exposed to media only was set as 1, and results were reported as increased values over media controls. IL-8 measurements were performed on media collected at the time of cell harvest, using a sandwich ELISA [MsαOv IL8 1:1,000, RbαOv IL8 1:1,000 (Chemicon)], and reported as fold increase of arbitrary units over media control animals (31).

Data Analysis and Statistics

Values for mRNA are reported as fold increase over media control for the experimental exposure and were tested for normality of distribution before mean or median values for each animal group were compared with one another. Statistics were analyzed with Prism 6 (GraphPad) using the Student’s t test, Mann–Whitney nonparametric, or ANOVA tests as appropriate. Significance was accepted as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Markers of Cell Types and Distributions along Main Airways

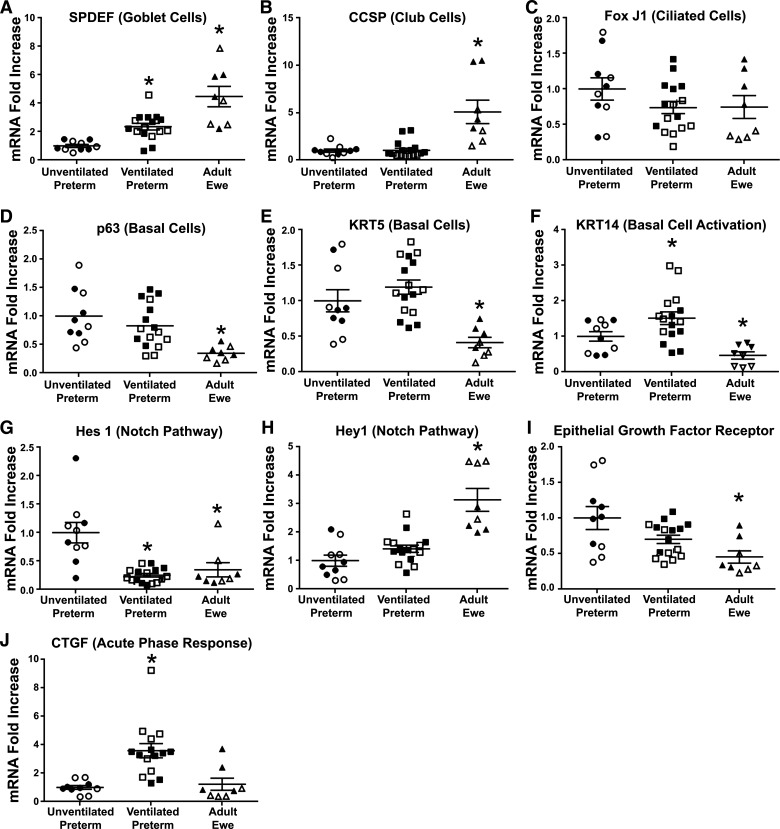

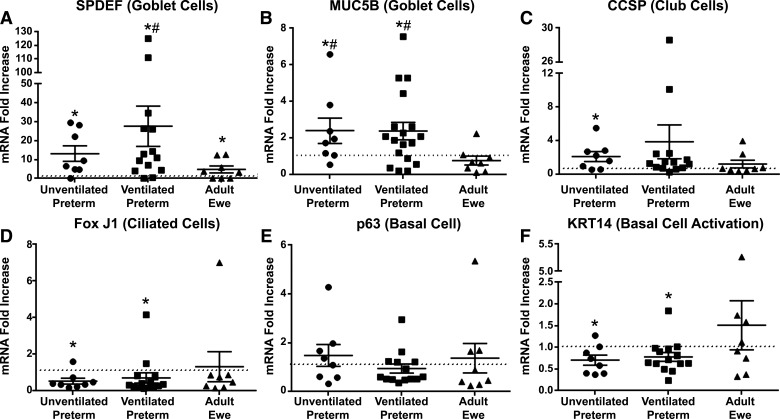

There were modest differences in the magnitude of mRNA changes between the trachea and the left mainstem bronchi (LMSB), but similar differences between cell types in the adult ewe and the unventilated preterm controls (Supplemental Table S1). Compared with unventilated preterm lambs, the adult ewes had higher and statistically significant changes in mRNA marker expression for goblet cells (SPDEF four- to fivefold) and club cells (CCSP three- to sevenfold), but fewer activated basal cells (p63 0.3- to 0.6-fold, KRT5 0.3- to 0.6-fold, and KRT14 0.2-fold) (Fig. 2). There were no differences in ciliated cells (Fox J1) between ewes and unventilated controls. The adult ewe had lower Hes 1 mRNA (0.2-fold), but higher Hey 1 mRNA (2.4-fold). There were no differences between preterm lambs receiving brief 30-min ventilation and injurious fetal ventilation (Supplemental Table S1). The mechanical ventilation of preterm lambs induced SPDEF mRNA and decreased Hes 1 to levels similar to adult ewes (Fig. 2). Mechanical ventilation also caused increased mRNA for the acute phase gene CTGF (three- to fivefold) and increased basal cell activation (KRT14 2.5-fold) (Fig. 2). Hey 1 mRNA was not altered by mechanical ventilation. EGFR mRNA was lower in adult trachea and LMSB, but not altered by mechanical ventilation.

Figure 2.

Comparison of baseline mRNA levels for tracheal (open symbols) and LMSB cells (filled symbols) at time of harvest. Median level for unventilated preterm lambs (n = 5) was set at one and other groups compared to them. A: SPDEF mRNA increased with mechanical ventilation in preterm lambs (n = 8). B: CCSP is more abundant in adult ewe (n = 4) and did not change with mechanical ventilation. C: Fox J1 was similar between groups. p63 (D) and KRT5 (E) were lower in adult ewes than unventilated preterm lambs. F: KRT14 was increased in ventilated preterm lambs and lower in adult ewe. G: Hes1 decreased with mechanical ventilation to adult ewe levels. H: Hey 1 is higher in adult ewe without change from mechanical ventilation. I: EGFR is lower in adult ewe than preterm unventilated lambs. J: CTGF increases with mechanical ventilation in preterm lambs. Means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. unventilated controls. CCSP, club cell secretory protein; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; EGFR, epithelial growth factor receptor; FOX J1, Forkhead box protein J1; Hes1, Hes family BHLH transcription factor 1; KRT5, keratin 5; LMSB, left mainstem bronchus; SPDEF, SAM-pointed domain-containing ETS transcription factor.

In the more distal bronchioles, the adult ewe had similar differences to unventilated preterm lambs found in the trachea and LMSB (Supplemental Table S1). Other than goblet cell mRNA increases, other cellular mRNA markers were similar between unventilated preterm lambs and those receiving mechanical ventilation.

Cell Culture Response to LPS Stimulation

Preliminary studies demonstrated no differences in the responses of the ovine cell cultures to 10 ng/mL, 100 ng/mL, or 1,000 ng/mL of LPS for either the ewe or the unventilated preterm lambs. Accordingly, 10 ng/mL was used for subsequent experiments (Supplemental Table S2).

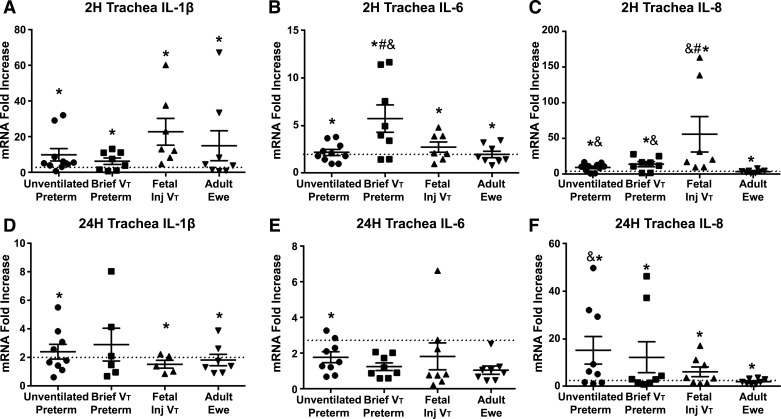

Adult fibroblasts respond to LPS in a manner similar to that of epithelial cells. Removing them from the culture did not change the cytokine mRNA response of epithelial cells when they were plated at same cell concentrations (Supplemental Table S2). To conserve preterm epithelial cells, experiments with and without fibroblasts were combined for results. Both preterm and adult ewe tracheal epithelial cell cultures responded to LPS exposure by 2 h with increased expression of mRNA transcripts for IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 (Fig. 3, A–C) compared with media-only cultures. Some elevation of mRNA was found at 24 h after exposure (Fig. 3, D–F). There were no differences in the tracheal cell responses for IL-1β between the groups at 2 h or 24 h (Fig. 3, A and D). IL-6 was highest in preterm lambs exposed to a brief period of mechanical ventilation at 2 h, but differences between groups had resolved at 24 h. IL-8 mRNA increases were higher in all the preterm lambs, with or without ventilation, than the adult ewes (Fig. 3C) at 2 h, and remained higher in the unventilated preterm cells at 24 h. Fetal injurious ventilation increased the tracheal cell IL-8 mRNA response compared with unventilated preterm and adult tracheal cells. The differences between the preterm and adult ewe cells were less consistent in the LMSB and the more distal bronchioles (Supplemental Table S3), but all the epithelial locations responded to LPS. MCP-1 mRNA did not change with LPS stimulation in the cell cultures in which it was assessed. Consistent with mRNA, protein levels in the tracheal cell media for IL-8 increased 17 ± 8-fold in unventilated preterm, 7 ± 6-fold in preterm brief mechanical ventilation, 7 ± 4-fold in fetal injurious ventilation, and 5 ± 2-fold in ewes after 2 h of exposure to LPS (P < 0.05 vs. media controls in all groups). Exposure to 10 ng/mL of LPS did not alter mRNA levels for p63, KRT14, or SPDEF in either unventilated preterm or adult ewes (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Cytokine mRNA responses in tracheal cells exposed to 10 ng/mL LPS for 2 h and 24 h. A: IL-1β mRNA increased in all groups with LPS exposure at 2 h. B: IL-6 mRNA increased with LPS exposure at 2 h, but was highest in the preterm animals exposed to a brief ventilation. C: IL-8 mRNA increased more in preterm cells than adult cells, and fetal mechanical ventilation increased the IL-8 mRNA response to LPS at 2 h. D: IL-1β remained slightly elevated at 2 h compared with media. E: IL-6 returned to baseline in all groups except unventilated preterm cells. F: IL-8 was higher at 24 h in the unventilated preterm cells than adult cells. Values are means ± SE; *P < 0.05 vs. media; &P < 0.05 vs. adult ewe; #P < 0.05 vs. unventilated preterm. LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Effects of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid on Cell Responses to LPS

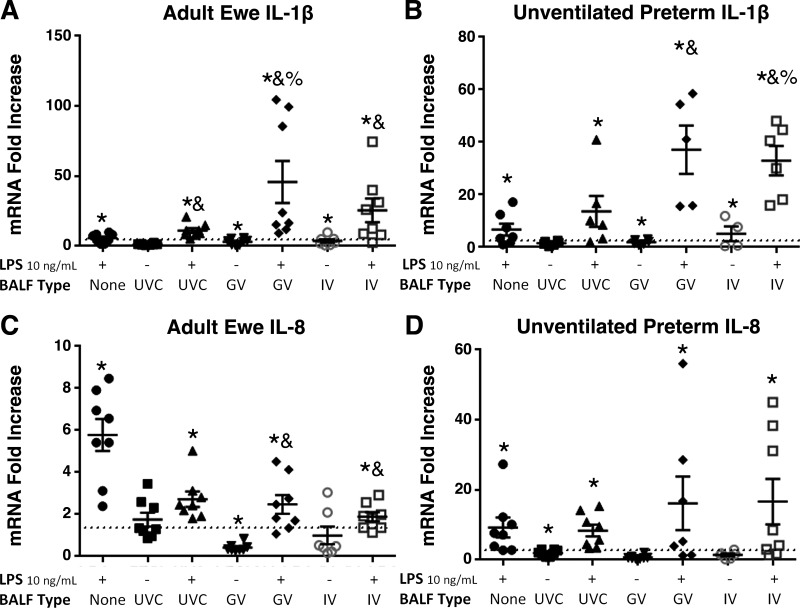

LMSB epithelial cell cultures from ewes and unventilated preterm lambs were exposed to BALF fluid from preterm lambs receiving no ventilation (UVC), gentle ventilation (GV) strategy, or an injurious ventilation (IV) (Fig. 4). IL-1β mRNA was not increased by UVC BALF, whereas there were moderate increases in both adult and unventilated preterm lambs (Fig. 4, A and B) when exposed to GV BALF and IV BALF. In adults, UVC BALF increased the response to LPS, whereas there was no significant difference in cells from unventilated preterm lambs. The GV BALF and IV BALF further increased the IL-1β response to LPS (Fig. 4, A and B). IL-8 mRNA responses to LPS were decreased in adult cells exposed to BALF GV and BALF IV (Fig. 4C). Unventilated preterm cells had variability in the IL-8 mRNA response to the combination of BALF and LPS (Fig. 4D) with trends P < 0.1 for increases. IL-8 protein in cell media also increased with exposure to BALF. Unventilated controls exposed to LPS had a 17 ± 8-fold increase in IL-8, whereas LPS + BALF causes a 54 ± 9-fold increase (P < 0.05). Adult epithelial cells also had an increase from 5 ± 2-fold for LPS to 21 ± 8-fold for LPS + BALF for IL-8 protein (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) on response to LPS in ewe and unventilated preterms. A and B: when exposed to BALF from lambs receiving gentle ventilation (GV) or injurious ventilation (IV), IL-1β mRNA increased compared with LPS 10 ng/mL or unventilated control BALF (UVC). C and D: IL-8 mRNA was decreased in the adult cells exposed to BALF compared with LPS alone. Preterm cells had increased IL-8 mRNA when exposed to GV and IV. *P < 0.05 vs. media; &P < 0.05 vs. LPS only; %P < 0.05 vs. UVC + LPS. LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Response to IL-13 Stimulation on Air-Liquid Interface

When grown on ALI for 7 days, preterm tracheal and LMSB cells respond to IL-13 stimulation with increased SPDEF mRNA production (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Table S4). Ventilated preterm cells had a larger SPDEF response to IL-13 than adult ewes (Fig. 5A). MUC5B mRNA was not increased in adult cells, whereas it was increased in both unventilated and ventilated preterm cells. CCSP was increased and FoxJ1 mRNA was decreased in preterm cells on ALI exposed to IL-13 versus media-only ALI. The mRNA for p63 basal cells did not change, but the KRT14 mRNA decreased with IL-13 exposure in preterm cells. Although some variability existed between tracheal and LMSB (Supplemental Table S4), similar patterns existed.

Figure 5.

Tracheal and LMSB epithelial cell responses to IL-13 on ALI. A: SPDEF mRNA in with IL-13 exposures in all groups, with a larger increase in ventilated preterm cells. B: MUC5B mRNA increased in unventilated and ventilated preterm cells, but no change was found in adult cells. C: variable responses in CCSP mRNA with overall increases in preterm cells. D: FoxJ1 mRNA was decreased in preterm cells. No change in p63 mRNA was found (E), though KRT14 activation was decreased (F) in preterm cells. *P < 0.05 vs. media; #P < 0.05 vs. adult ewe. ALI, air-liquid interface; CCSP, club cell secretory protein; LMSB, left mainstem bronchus; MUC5B, Mucin 5B; SPDEF, SAM-pointed domain-containing ETS transcription factor.

DISCUSSION

The principal findings of this study are 1) brief mechanical ventilation of preterm lambs altered epithelium cell types along the airway (trachea, LMSB, and bronchioles); 2) mechanical ventilation changes responses of preterm respiratory epithelium to stimulation; 3) preterm epithelial cells grown on ALI can respond to IL-13 with goblet cell mRNA induction; and 4) BALF from mechanically ventilated lambs, either normal or injurious, changed the response to LPS (Graphical Abstract). The ability to extract and culture respiratory epithelial cells from the airways of preterm lambs, which have similar cell types distributions to the human, provides a useful model for determining epithelial changes due to mechanical ventilation or environmental exposures. Although we did not conduct advanced immunohistochemistry or protein localization, these experiments demonstrated the ability of the preterm airway epithelium to respond to both LPS and IL-13 (21, 24, 27). Preterm infants can have long-term airway abnormalities, and cell culture experiments could provide insights into the mechanisms for these changes (1–3). Clinically, these data support efforts to decrease even short periods of mechanical ventilation in preterm infants, since both BALF from gentle and injurious ventilation can alter cytokine response to LPS. This epithelial cell model system could be used to study the effects of other lung diseases in different pediatric ages.

The increase in the goblet cell mRNA and activation of basal cells (KRT14) with mechanical ventilation is consistent with our previous studies (10). The decrease in Hes 1 to near adult levels, and the trend toward more adult levels of other cell markers demonstrate that mechanical ventilation may possibly lead to the maturation of the airway epithelium, similar to the maturational effects found in the peripheral lung with mechanical ventilation (7, 9). The Brief VT preterm lambs underwent ventilation for only 30 min before cell isolation. This demonstrates that even a short period of mechanical ventilation can reprogram a cell and can contribute to the aberrant airway development consistent with the pattern found in preterm infants with BPD.

Other respiratory epithelial culture systems of premature infants have used nasal pharyngeal cultures, which require less invasive procedures to obtain (23, 24, 32). Prematurity affects upper airway epithelial cell proliferation, oxygen consumption, mitochondrial processes, and ciliary function compared with term nasal epithelium (32). Prematurity did not prevent basal cell expansion and repair in nasal pharyngeal cultures, but the expression of thousands of genes differed within the p63 basal cells of term and preterm infants (32). In vivo, preterm sheep repair airway injury through activation of basal cells similar to murine models (10, 19). Premature nasal epithelial cells also take longer to repair injury than term cells (23). Goblet cell induction, similar to our model, is also found in preterm nasal epithelial models (24). Epithelial cells from tracheal aspirates of premature infants have also recently been grown in three-dimensional (3-D) organelles and these organelles respond to cigarette smoke with enhanced IL-8 production compared with organelles from adult BALF (33). Premature ovine airway epithelial cells can also respond to viral infections (respiratory syncytial virus), with some differences between preterm and term lambs (34). Other groups have not found differences between preterm and term nasal pharyngeal cultures, but this may be due to the gestational age of the infants sampled (24). Overall, our current data, and data from the nasal epithelial cultures, demonstrate that a preterm infant’s airway epithelium can respond to stimuli, but in a slightly different manner than term or adult cells.

LPS increased inflammatory cytokine mRNA production in all animal groups but did not affect any epithelial cell differentiation markers. The increase in inflammatory cytokine production was expected due to the known proinflammatory properties of LPS (30). We have previously demonstrated the preterm peripheral lung can respond to other Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists and to live bacteria like ureaplasma (35, 36). Pediatric primary bronchial airway epithelial cultures can recognize environmental stimuli and respond with cytokine production (20). IL-8 mRNA induction was larger in preterm animals than in adult ewe cells, and both mechanical ventilation before cell harvest or exposure to BALF further increased IL-8 mRNA. Tracheal aspirates from preterm infants also increase IL-8 in culture (37). The lack of MCP-1 mRNA induction in epithelial cells with LPS is consistent with previous in situ localization in preterm lamb lung parenchyma, but not the airway epithelium (30). Mechanical stretch increases IL-6 mRNA localization to the airway epithelium, similar to the IL-6 response to LPS in epithelial cultures (7). The lack of change in cellular differentiation after LPS exposure indicates that TLR4 activation alone does not trigger the cascade of events that result in BPD and that injury to the underdeveloped epithelial tissue may be a prerequisite for BPD relayed airway disease development.

The combination of BALF from mechanically ventilated animals and LPS had a synergistic effect on IL-1β mRNA expression across all animal groups. The BALF had differential effects on IL-8 mRNA production in preterm and adult cells. Similarly, tracheal aspirates from mechanically ventilated preterm infants increased IL-8 in culture cells, and the effect on IL-8 can be decreased with anti-IL-1β neutralizing antibodies (37). BALF from preterm infants with chorioamnionitis inhibited alveolar epithelial repair in cultures (38). The BALF contains a variety of different proteins and cellular products, and it is unclear what is causing the effect. Previous research has shown that mechanical ventilation releases heat shock proteins (HSPs) and other inflammatory mediators from airway epithelial cells (7, 9). HSP70 modulates the inflammatory cascade through Toll-like receptor 4 in a manner similar to that of LPS (39). Therefore, the combination of BALF from mechanically ventilated animals may augment the TLR4 response and lead to an increase in the downstream inflammatory cascade response to LPS. Early effects on innate immunity training of the epithelial cells may have long-standing effects on airway function (40). The BALF from both lambs receiving gentle ventilation and injurious ventilation had these additive effects on LPS, suggesting that even protective ventilator techniques could lead to enhance inflammation.

Preterm respiratory epithelial cells were grown on ALI and demonstrated increased goblet cell mRNA when exposed to IL-13. IL-13 is a central cytokine mediator of asthma and contributes to both mucin production and airway hypersensitivity (41). A similar ability of premature nasal/pharyngeal epithelial cells to differentiate on ALI has been found (32). It is unclear if goblet cell hyperplasia found after fetal mechanical ventilation is due to IL-13 because it was not measured in previous studies, or through activation of other pathways such as EGFR (10, 42). These ALI experiments demonstrated the ability of preterm cells to respond to IL-13, suggesting many of the epithelial cell activation pathways are present in preterm infants.

Although we have focused on differences between preterm and adult ewes, many similarities exist between the epithelial cells. They both have the ability to respond to stimulation from LPS and IL-13. Since the airways were dissected and isolated within 30 min of mechanical ventilation and cells were frozen 72 h after removal, this suggests the epithelial alteration does not require a long period of stimulation or time to develop. The changes with a short mechanical ventilation period may represent maturational changes that are triggered by either airway stretch or epithelial injury and likely are present in the preterm human airways. The similarities between epithelial cell responses could signify that procedures that harm or medications that help airway responses in children and adults could have similar effects on preterm infants whose cells have been triggered to mature.

Limitations

Due to the labor-intensive nature of collecting epithelial cells during ongoing ventilation studies, the number of animals used in the studies (n = 4 per group) was small and may have affected our ability to find significant changes where trends existed (25). Another major limitation is that the majority of the data is mRNA data, whereas only the translation of IL-8 was confirmed through ELISA. Although we have previously demonstrated protein changes when mRNA changes exist at an earlier time point in sheep (7, 10), this is not always the case. The ELISA data also could have been partially biased from IL-8 still present in the BALF. Discrepancies between mRNA and protein data for IL-8 could be due to the timing of mRNA production and protein release. The ALI cultures were only completed for 7 days on ALI with exposures and the cells may not have fully differentiated into all cell types (26, 29, 32). Since mRNA was the eventual readout of the ALI cultures, the induction of goblet cells by IL-13 was not confirmed by more sophisticated methods such as immunohistochemistry. The limited number of epithelial cells, from a desire to limit the experiments to primary or second passage cells, reduced our ability to conduct additional experimental conditions. Though limited, these experiments provide strong evidence that preterm epithelial cells have the ability to respond to external stimuli in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Conclusions

Preterm respiratory epithelial cells responded to LPS and IL-13, with minor differences from the response of adult cells. Mechanical ventilation or exposure to BALF from mechanically ventilated animals altered the responses to LPS in both preterm and adult cells. Chronic changes in the airways of preterm infants with BPD may be due to maladaptive responses to stimuli early in life. The preterm ovine respiratory epithelium can be successfully collected and reanimated in culture, and this can provide a method of evaluating preterm airway responses to stimuli.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Tables S1–S4: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22223278.v2.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 HD072842 (to A.H.J.) and the Fleur-de-Lis Foundation (to N.H.H.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.W.K., A.H.J., and N.H.H. conceived and designed research; L.A., E.X.R., M.W.K., A.H.J., and N.H.H. performed experiments; L.A., E.X.R., and N.H.H. analyzed data; L.A. and N.H.H. interpreted results of experiments; N.H.H. prepared figures; L.A., M.W.K., A.H.J., and N.H.H. drafted manuscript; L.A., E.X.R., M.W.K., A.H.J., and N.H.H. edited and revised manuscript; L.A., E.X.R., M.W.K., A.H.J., and N.H.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Steven Brody (Washington University) and Dr. Laurie Shornick (Saint Louis University) assisted N. H. Hillman in learning cell extraction and culture techniques. Dr. Masatoshi Saito and Dr. Haruo Usuda (Tohoku University) assisted in the harvest of ewe lungs. Graphical abstract image created with BioRender.com and published with permission.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jobe AJ. The new BPD: an arrest of lung development. Pediatr Res 46: 641–643, 1999. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fawke J, Lum S, Kirkby J, Hennessy E, Marlow N, Rowell V, Thomas S, Stocks J. Lung function and respiratory symptoms at 11 years in children born extremely preterm: the EPICure study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182: 237–245, 2010. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1806OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doyle LW, Carse E, Adams A-M, Ranganathan S, Opie G, Cheong JLY; Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group. Ventilation in extremely preterm infants and respiratory function at 8 years. N Engl J Med 377: 329–337, 2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hennessy EM, Bracewell MA, Wood N, Wolke D, Costeloe K, Gibson A, Marlow N; EPICure Study Group. Respiratory health in pre-school and school age children following extremely preterm birth. Arch Dis Child 93: 1037–1043, 2008. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.140830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Been JV, Lugtenberg MJ, Smets E, van Schayck CP, Kramer BW, Mommers M, Sheikh A. Preterm birth and childhood wheezing disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 11: e1001596, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colin AA, McEvoy C, Castile RG. Respiratory morbidity and lung function in preterm infants of 32 to 36 weeks' gestational age. Pediatrics 126: 115–128, 2010. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hillman NH, Kallapur SG, Pillow JJ, Moss TJM, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Jobe AH. Airway injury from initiating ventilation in preterm sheep. Pediatr Res 67: 60–65, 2010. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181c1b09e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hillman NH, Moss TJM, Kallapur SG, Bachurski C, Pillow JJ, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Kramer BW, Jobe AH. Brief, large tidal volume ventilation initiates lung injury and a systemic response in fetal sheep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 575–581, 2007. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-051OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hillman NH, Polglase GR, Jane Pillow J, Saito M, Kallapur SG, Jobe AH. Inflammation and lung maturation from stretch injury in preterm fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300: L232–L241, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00294.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deptula N, Royse E, Kemp MW, Miura Y, Kallapur SG, Jobe AH, Hillman NH. Brief mechanical ventilation causes differential epithelial repair along the airways of fetal, preterm lambs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 311: L412–L420, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00181.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schilleman K, van der Pot CJM, Hooper SB, Lopriore E, Walther FJ, Te Pas AB. Evaluating manual inflations and breathing during mask ventilation in preterm infants at birth. J Pediatr 162: 457–463, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. MacFarlane PM, Mayer CA, Jafri A, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS, Martin RJ. CPAP protects against hyperoxia-induced increase in airway reactivity in neonatal mice. Pediatr Res 90: 52–57, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-01212-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petersen RY, Royse E, Kemp MW, Miura Y, Noe A, Jobe AH, Hillman NH. Distending pressure did not activate acute phase or inflammatory responses in the airways and lungs of fetal, preterm lambs. PLoS One 11: e0159754, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rackley CR, Stripp BR. Building and maintaining the epithelium of the lung. J Clin Invest 122: 2724–2730, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI60519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brew N, Hooper SB, Allison BJ, Wallace MJ, Harding R. Injury and repair in the very immature lung following brief mechanical ventilation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L917–L926, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00207.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brew N, Hooper SB, Zahra V, Wallace M, Harding R. Mechanical ventilation injury and repair in extremely and very preterm lungs. PLoS One 8: e63905, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hogan BLM, Barkauskas CE, Chapman HA, Epstein JA, Jain R, Hsia CC, Niklason L, Calle E, Le A, Randell SH, Rock J, Snitow M, Krummel M, Stripp BR, Vu T, White ES, Whitsett JA, Morrisey EE. Repair and regeneration of the respiratory system: complexity, plasticity, and mechanisms of lung stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell 15: 123–138, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumar PA, Hu Y, Yamamoto Y, Hoe NB, Wei TS, Mu D, Sun Y, Joo LS, Dagher R, Zielonka EM, Wang de Y, Lim B, Chow VT, Crum CP, Xian W, McKeon F. Distal airway stem cells yield alveoli in vitro and during lung regeneration following H1N1 influenza infection. Cell 147: 525–538, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rock JR, Onaitis MW, Rawlins EL, Lu Y, Clark CP, Xue Y, Randell SH, Hogan BLM. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 12771–12775, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906850106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McInnes N, Davidson M, Scaife A, Miller D, Spiteri D, Engelhardt T, Semple S, Devereux G, Walsh G, Turner S. Primary paediatric bronchial airway epithelial cell in vitro responses to environmental exposures. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13: 359, 2016. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13040359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Everman JL, Rios C, Seibold MA. Utilization of air-liquid interface cultures as an in vitro model to assess primary airway epithelial cell responses to the type 2 cytokine interleukin-13. Methods Mol Biol 1799: 419–432, 2018. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7896-0_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Looi K, Evans DJ, Garratt LW, Ang S, Hillas JK, Kicic A, Simpson SJ. Preterm birth: born too soon for the developing airway epithelium? Paediatr Respir Rev 31: 82–88, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hillas J, Evans DJ, Ang S, Iosifidis T, Garratt LW, Hemy N, Kicic-Starcevich E, Simpson SJ, Kicic A. Nasal airway epithelial repair after very preterm birth. ERJ Open Res 7: 00913-2020, 2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00913-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Groves HE, Guo-Parke H, Broadbent L, Shields MD, Power UF. Characterisation of morphological differences in well-differentiated nasal epithelial cell cultures from preterm and term infants at birth and one-year. PLoS One 13: e0201328, 2018. [Erratum in PLoS One 14: e0211611, 2019]. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kothe TB, Royse E, Kemp MW, Schmidt A, Salomone F, Saito M, Usuda H, Watanabe S, Musk GC, Jobe AH, Hillman NH. Effects of budesonide and surfactant in preterm fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 315: L193–L201, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00528.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. You Y, Brody SL. Culture and differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells. Methods Mol Biol 945: 123–143, 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-125-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fulcher ML, Gabriel S, Burns KA, Yankaskas JR, Randell SH. Well-differentiated human airway epithelial cell cultures. Methods Mol Med 107: 183–206, 2005. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-861-7:183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hillman NH, Kothe TB, Schmidt AF, Kemp MW, Royse E, Fee E, Salomone F, Clarke MW, Musk GC, Jobe AH. Surfactant plus budesonide decreases lung and systemic responses to injurious ventilation in preterm sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 318: L41–L48, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00203.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiang D, Schaefer N, Chu HW. Air-liquid interface culture of human and mouse airway epithelial cells. Methods Mol Biol 1809: 91–109, 2018. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8570-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shah TA, Hillman NH, Nitsos I, Polglase GR, Jane Pillow J, Newnham JP, Jobe AH, Kallapur SG. Pulmonary and systemic expression of monocyte chemotactic proteins in preterm sheep fetuses exposed to lipopolysaccharide-induced chorioamnionitis. Pediatr Res 68: 210–215, 2010. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181e9c556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kothe TB, Kemp MW, Schmidt A, Royse E, Salomone F, Clarke MW, Musk GC, Jobe AH, Hillman NH. Surfactant plus budesonide decreases lung and systemic inflammation in mechanically ventilated preterm sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 316: L888–L893, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shui JE, Wang W, Liu H, Stepanova A, Liao G, Qian J, Ai X, Ten V, Lu J, Cardoso WV. Prematurity alters the progenitor cell program of the upper respiratory tract of neonates. Sci Rep 11: 10799, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90093-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eenjes E, van Riet S, Kroon AA, Slats AM, Khedoe P, Boerema-de Munck A, Buscop-van Kempen M, Ninaber DK, Reiss IKM, Clevers H, Rottier RJ, Hiemstra PS. Disease modeling following organoid-based expansion of airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 321: L775–L786, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00234.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawashima K, Meyerholz DK, Gallup JM, Grubor B, Lazic T, Lehmkuhl HD, Ackermann MR. Differential expression of ovine innate immune genes by preterm and neonatal lung epithelia infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Viral Immunol 19: 316–323, 2006. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hillman NH, Moss TJM, Nitsos I, Kramer BW, Bachurski CJ, Ikegami M, Jobe AH, Kallapur SG. Toll-like receptors and agonist responses in the developing fetal sheep lung. Pediatr Res 63: 388–393, 2008. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181647b3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Polglase GR, Hillman NH, Pillow JJ, Nitsos I, Newnham JP, Knox CL, Kallapur SG, Jobe AH. Ventilation-mediated injury after preterm delivery of Ureaplasma parvum colonized fetal lambs. Pediatr Res 67: 630–635, 2010. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181dbbd18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shimotake TK, Izhar FM, Rumilla K, Li J, Tan A, Page K, Brasier AR, Schreiber MD, Hershenson MB. Interleukin (IL)-1 beta in tracheal aspirates from premature infants induces airway epithelial cell IL-8 expression via an NF-kappa B dependent pathway. Pediatr Res 56: 907–913, 2004. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000145274.47221.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Been JV, Zimmermann LJI, Debeer A, Kloosterboer N, van Iwaarden JF. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from preterm infants with chorioamnionitis inhibits alveolar epithelial repair. Respir Res 10: 116, 2009. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tsan M-F, Gao B. Cytokine function of heat shock proteins. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C739–C744, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00364.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nino G, Gutierrez MJ, Rodriguez-Martinez CE. Human neonatal and infant airway epithelial biology: the new frontier for developmental immunology. Expert Rev Respir Med 16: 145–147, 2022. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2022.2027757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marone G, Granata F, Pucino V, Pecoraro A, Heffler E, Loffredo S, Scadding GW, Varricchi G. The intriguing role of interleukin 13 in the pathophysiology of asthma. Front Pharmacol 10: 1387, 2019. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kothe TB, Royse E, Kemp MW, Usuda H, Saito M, Musk GC, Jobe AH, Hillman NH. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition with Gefitinib does not alter lung responses to mechanical ventilation in fetal, preterm lambs. PLoS One 13: e0200713, 2018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Tables S1–S4: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22223278.v2.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.