Abstract

Objective

The present study aimed to give an overall view of the pattern of high-dose vitamin A supplementation (VAS) coverage in twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries and factors associated with receipt of VAS among children aged 6–59 months.

Design

Cross-sectional data from the twenty-three Demographic and Health Surveys conducted from 2011 to 2015 in twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries were pooled. A multilevel logistic regression model was used to explore factors associated with VAS.

Setting

Twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries.

Participants

Children (n 215 511) aged 6–59 months.

Results

The overall coverage of VAS among children aged 6–59 months for the surveys included was 59·4 %. In the multivariable analysis, children whose mothers had primary (adjusted OR (aOR)=1·43; 95 % CI 1·39, 1·47) or secondary or above (aOR=1·72; 95 % CI 1·67, 1·77) educational status were more likely to receive VAS than children whose mothers had no formal education. Other factors associated with significantly increased likelihood of VAS were: living in urban areas; children of working mothers; children whose mothers had higher media exposure; children of older mothers v. children of mothers aged 15–19 years; and older children v. children aged 6–11 months. At the country level, lower media exposure was significant and negatively associated with VAS.

Conclusions

Broader VAS coverage is needed according to our data. More efforts are needed to scale up coverage, focusing mostly on groups at risk of non-receipt of vitamin A.

Keywords: Vitamin A, Supplementation, Sub-Saharan Africa, Coverage, Children

Vitamin A is an essential nutrient needed for the normal functioning of the visual system, maintenance of cell function for growth, red blood cell production, immunity and reproduction( 1 , 2 ). Globally, in 2013 one-third of children aged 6–59 months had vitamin A deficiency with one of the highest rates (48 %) observed in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)( 3 ). Furthermore, in the regions of South Asia and SSA, vitamin A deficiency accounted for about 2 % of child deaths( 4 ).

The WHO recommends semi-annual high-dose vitamin A supplementation (VAS) for children aged 6–59 months in countries where vitamin A deficiency is recognised as a public health problem and in countries with under-5 mortality rate above 70 per 1000 live births( 5 ). According to a previous study, vitamin A supplements can improve a child’s chance of survival by 12 to 24 %( 6 ). Recent food-based approaches, such as food fortification and consumption of foods rich in vitamin A, are ongoing and are essential to ending vitamin A deficiency in the long term. However, until such programmes are sustained at a large scale, delivery of high-dose supplements remains the principal strategy in use for controlling vitamin A deficiency for children aged 6–59 months, despite its inability to maintain normal serum retinol levels( 7 , 8 ). In addition, VAS has been proven to be safe, with a cost:benefit ratio of 17:1 for South Asia, East Asia and SSA, and an equitable way of reaching the most vulnerable children( 7 , 9 ). Ensuring universal VAS coverage (100 %) in SSA or at least effective coverage (≥80 %) needed to improve child survival is important( 10 ) and is also a central component of the child survival agenda in the region. In the literature, some studies have been done with the aim of identifying differentials for uptake of VAS among children aged 6–59 months( 11 – 24 ). Identifying these differentials for vitamin A uptake among children aged 6–59 months in SSA will aid international efforts aimed at increasing VAS coverage in SSA. Thus, the present study’s objective was to give an overall view of the pattern of high-dose VAS coverage for the surveys we included as well as examine factors associated with receipt of VAS among children aged 6–59 months.

Methods

Study sample

Out of fifty-four countries in Africa, forty-six are listed as sub-Saharan Africa( 25 ). We used pooled cross-sectional data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted in twenty-three SSA countries from 2011 to 2015, with the countries selected based on availability of comparative data( 26 ). The pooled DHS data have a hierarchical structure with individuals nested within countries. Our study sample was restricted to children aged 6–59 months and the sample size ranged from 4279 in Namibia to 25 607 in Nigeria (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Demographic and Health Surveys conducted from 2011 to 2015 in the sub-Saharan African countries included in the present study

| Received vitamin A supplementation in the last 6 months† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Survey year | Children aged 6–59 months (n)* | n | % |

| Benin | 2011–12 | 11 422 | 5485 | 48·6 |

| Congo DR | 2013–14 | 15 255 | 10 587 | 70·4 |

| Congo | 2011–12 | 7883 | 4479 | 64·9 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 2011–12 | 6299 | 3714 | 60·8 |

| Cameroon | 2011 | 9582 | 5284 | 55·3 |

| Gabon | 2012 | 5101 | 2317 | 53·8 |

| Ghana | 2014 | 4982 | 3171 | 65·2 |

| Gambia | 2013 | 6818 | 4572 | 68·7 |

| Guinea | 2012 | 5692 | 2329 | 40·8 |

| Kenya | 2014 | 18 256 | 12 202 | 71·7 |

| Liberia | 2013 | 6329 | 3278 | 60·2 |

| Mali | 2012–13 | 8566 | 5273 | 60·8 |

| Mozambique | 2011 | 9221 | 7199 | 74·6 |

| Nigeria | 2013 | 25 607 | 10 723 | 41·3 |

| Niger | 2012 | 10 281 | 6422 | 59·6 |

| Namibia | 2013 | 4279 | 3417 | 83·6 |

| Rwanda | 2014–15 | 6845 | 6022 | 86·4 |

| Sierra Leone | 2013 | 9464 | 7959 | 83·2 |

| Senegal | 2015 | 5964 | 4826 | 88·4 |

| Chad | 2014–15 | 15 058 | 6607 | 44·1 |

| Togo | 2013–14 | 5918 | 4664 | 81·7 |

| Zambia | 2013–14 | 11 506 | 8745 | 76·5 |

| Zimbabwe | 2015 | 5183 | 3633 | 67·0 |

| All | 2011–2015 | 215 511 | – | 59·4‡ |

Unweighted case numbers.

Individual countries’ sample weight numbers and percentages.

Based on pooled sample weights, derived from women's individual weights and population size of women aged 15–49 years for respective countries.

Vitamin A supplementation

Our outcome variable VAS was defined as receipt of VAS in the last 6 months prior to the survey and was expressed as a dichotomous variable, with category 1 for receipt of VAS and category 0 for non-receipt of VAS. Explanatory variables were chosen based on previous studies and grouped into individual-level and contextual country-level variables. Individual-level variables included the following: mother’s age; mother’s educational status; mother’s occupational status; marital status; place of residence; sex of household head; sex of child; age of child; and media exposure score, which was created from the variables (i) frequency of reading newspapers or magazines, (ii) frequency of listening to the radio and (iii) frequency of watching television. To each of these variables, a score of 0 was given if the response was ‘not at all’, 1 if the response was ‘less than once a week’ and 2 if the response was ‘at least once a week or almost every day’ (five countries additionally measured response for ‘almost every day’). The three variables were later summed up to create the variable ‘media exposure score’. Contextual country-level factors included gross domestic product per capita based on purchasing power parity( 27 ) and proportion of respondents with media exposure score of 0 in the country.

Statistical analysis

The demographic and socio-economic characteristics of respondents are given as unweighted case numbers and percentages, whereas the overall prevalence of VAS among children aged 6–59 months in SSA and receipt of VAS according to demographic and socio-economic characteristics of respondents are reported as weighted percentages based on women’s individual weights and population size of women aged 15–49 years in the respective countries(

28

). Due to the hierarchical structure of the data, for the multivariable analysis we applied a multilevel logistic regression to explore factors associated with VAS among children aged 6–59 months using MLwiN multilevel software(

29

); mother–children pairs made up the first level, while countries made up the second level. Parameter estimates using MLwiN were based on the second-order predictive (or penalized) quasi-likelihood procedure. The proportion of the variance in VAS among children aged 6–59 months due to differences between countries, the intra-country correlation coefficient, was calculated as  where

where  is the total variance at the country level and

is the total variance at the country level and  is the total variance at the individual level. In multilevel logistic regression model, the level 1 residuals, e

ij

, are assumed to follow a standard logistic distribution with a mean of 0 and variance

is the total variance at the individual level. In multilevel logistic regression model, the level 1 residuals, e

ij

, are assumed to follow a standard logistic distribution with a mean of 0 and variance  (

30

). Country-level residuals were used to explore country-level variations in VAS among children aged 6–59 months by constructing simultaneous 95 % CI using caterpillar plots. The width of the interval to achieve a 5 % significance was set at 1·39σ

(

31

). Countries whose 95 % CI did not overlap were considered significant at the 5 % level. The simultaneous CI were constructed before (Model 0) and after controlling for individual and contextual factors (Model 1).

(

30

). Country-level residuals were used to explore country-level variations in VAS among children aged 6–59 months by constructing simultaneous 95 % CI using caterpillar plots. The width of the interval to achieve a 5 % significance was set at 1·39σ

(

31

). Countries whose 95 % CI did not overlap were considered significant at the 5 % level. The simultaneous CI were constructed before (Model 0) and after controlling for individual and contextual factors (Model 1).

Ethics

The surveys were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of ICF International at Calverton, MD, USA and by the National Ethics Committee of the various countries involved in the study. Permission to use and analyse the data set was obtained by registering the study on the DHS website.

Results

VAS coverage among children aged 6–59 months for the surveys we included was 59·4 % (Table 1). Of mothers, 27·9 % were in the age bracket 25–29 years old and 43·8 % had no formal education. A higher proportion of mothers were working mothers, 65·5 %, and 67·9 % resided in rural areas. Most (45·2 %) mothers had a media exposure score of 1–3 and males headed the majority of households (80·2 %). The majority of mothers were currently in a union/living with a man (88·1 %); male (50·2 %) and female children (49·8 %) were more or less equal; and the majority of children were in the age group 36–47 months (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of children aged 6–59 months who received vitamin A supplementation (VAS), by demographic and socio-economic characteristics, in twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries, 2011–2015, using pooled cross-sectional data from Demographic and Health Surveys

| Total* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % | VAS coverage (%)† |

| Mother’s age (years) | |||

| 15–19 | 11 901 | 5·5 | 53·6 |

| 20–24 | 46 091 | 21·4 | 57·4 |

| 25–29 | 60 193 | 27·9 | 59·9 |

| 30–34 | 45 867 | 21·3 | 61·4 |

| ≥35 | 51 459 | 23·9 | 60·0 |

| Mother’s educational status | |||

| No education | 94 316 | 43·8 | 46·9 |

| Primary | 66 778 | 31·0 | 65·6 |

| Secondary or above | 54 392 | 25·2 | 69·3 |

| Mother’s occupational status | |||

| Not working | 70 261 | 34·5 | 54·5 |

| Working | 133 447 | 65·5 | 60·7 |

| Type of place of residence | |||

| Urban | 69 230 | 32·1 | 65·7 |

| Rural | 146 281 | 67·9 | 56·2 |

| Mass media exposure score | |||

| 0 | 74 590 | 34·8 | 49·2 |

| 1–3 | 96 788 | 45·2 | 62·2 |

| 4 or above | 42 928 | 20·0 | 68·9 |

| Sex of household head | |||

| Male | 172 816 | 80·2 | 57·8 |

| Female | 42 695 | 19·8 | 67·0 |

| Marital status | |||

| Never in a union/formerly in a union | 25 722 | 11·9 | 67·1 |

| Currently in union/living with a man | 189 789 | 88·1 | 58·6 |

| Sex of child | |||

| Male | 108 288 | 50·2 | 59·5 |

| Female | 107 223 | 49·8 | 59·4 |

| Age of child (months) | |||

| 6–11 | 26 268 | 12·2 | 54·1 |

| 12–23 | 48 305 | 22·4 | 63·9 |

| 24–35 | 46 935 | 21·8 | 60·9 |

| 36–47 | 48 436 | 22·5 | 58·6 |

| 48–59 | 45 567 | 21·1 | 57·1 |

Unweighted case numbers and percentages.

Based on pooled sample weights, derived from women’s individual weights and population size of women aged 15–49 years for respective countries.

Descriptive, unadjusted associations with vitamin A supplementation in twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries

VAS coverage was higher among children whose mothers were in the age group 30–34 years (Table 2). However, this varied considerably by country (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1). At 69·3 %, VAS coverage was highest among children whose mothers had secondary or above educational status (Table 2). Coverage increased significantly with higher maternal education in sixteen countries (Supplemental Table 1). Coverage was also significantly higher in fourteen countries among children who had working mothers (Supplemental Table 1). Compared with male-headed households, in seven countries, female-headed households had significantly higher VAS coverage among children aged 6–59 months; on the other hand, in five countries, coverage among children aged 6–59 months was observed to be significantly higher in male-headed households (online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2). Coverage was significantly higher among children aged 12–23 months in eighteen countries (online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 3). Overall, coverage was observed to be higher among children living in urban areas, children whose mothers had a media exposure score of 4 or above, children whose mothers were never in a union/formerly in a union and among male children (Table 2).

Country variations

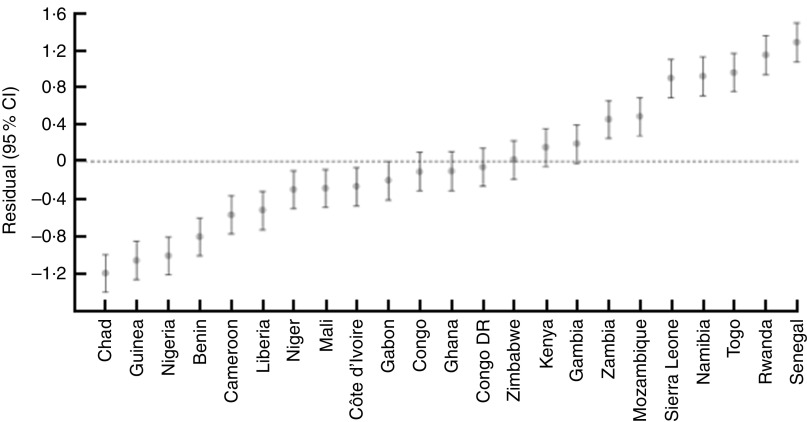

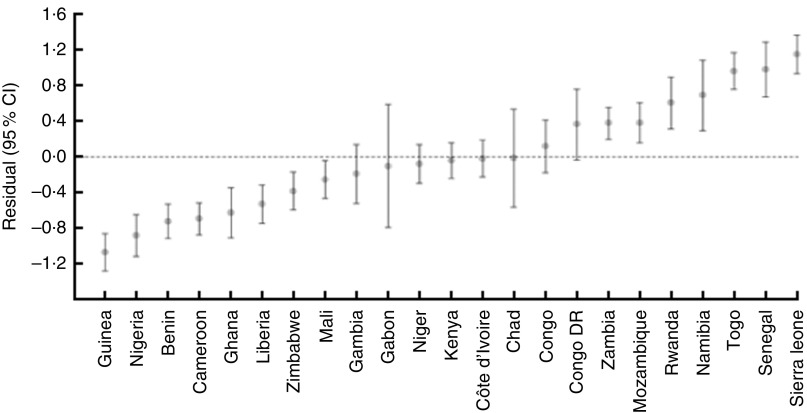

In Model 0 (null model), the intra-country correlation was 12·9 %; however, after taking account of background sociodemographic characteristics (Model 1), approximately 9·9 % of the total unexplained variation in VAS could be attributed to unobserved country-level factors. Figure 1 shows the simultaneous CI of country-level residuals in the null model (Model 0). Senegal had significantly higher likelihood of having received VAS than the remaining countries except Rwanda, Togo, Namibia and Sierra Leone, with which the simultaneous CI overlapped. Figure 2 shows the simultaneous CI of country-level residuals after controlling for contextual country-level factors (Model 1). Sierra Leone had significantly higher likelihood of coverage among children aged 6–59 months than the remaining countries with the exception of Senegal, Togo and Namibia, with which the simultaneous CI overlapped.

Fig. 1.

Simultaneous 95 % CI (vertical bars) for country-level residuals ( ) of vitamin A supplementation among children aged 6–59 months (n 215 511) in twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries, 2011–2015, using pooled cross-sectional data from Demographic and Health Surveys: Model 0 (null model)

) of vitamin A supplementation among children aged 6–59 months (n 215 511) in twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries, 2011–2015, using pooled cross-sectional data from Demographic and Health Surveys: Model 0 (null model)

Fig. 2.

Simultaneous 95 % CI (vertical bars) for country-level residuals ( ) of vitamin A supplementation among children aged 6–59 months (n 215 511) in twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries, 2011–2015, using pooled cross-sectional data from Demographic and Health Surveys: Model 1 (controlling for individual-level and contextual country-level factors)

) of vitamin A supplementation among children aged 6–59 months (n 215 511) in twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries, 2011–2015, using pooled cross-sectional data from Demographic and Health Surveys: Model 1 (controlling for individual-level and contextual country-level factors)

Explanatory factors associated with vitamin A supplementation among children aged 6–59 months

Table 3 shows the adjusted associations between VAS and explanatory variables. Children with older mothers were significantly more likely to receive VAS than children with mothers aged 15–19 years. Children whose mothers had primary education and children whose mothers had secondary or above educational status had higher likelihood of receiving VAS than children whose mothers had no formal education. Children who resided in urban areas were significantly more likely to receive VAS compared with children living in rural areas. Children with working mothers were more likely to receive VAS compared with children who had non-working mothers. Children whose mothers had a media exposure score of 1–3 and of 4 or above had higher likelihood of receiving VAS compared with children whose mothers had a media exposure score of 0. Finally, older children were significantly more likely to receive VAS than those aged 6–11 months. At the country level, lower media exposure score was significantly associated with lower coverage.

Table 3.

Multilevel logistic regression analysis for the receipt of vitamin A supplementation among children aged 6–59 months in twenty-three sub-Saharan African countries, 2011–2015, using pooled cross-sectional data from Demographic and Health Surveys

| Model 0 | Model 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95 % CI | P value | OR | 95 % CI | P value |

| Fixed effects, constant | 2·07 | 1·56, 2·75 | <0·001 | 1·44 | 0·70, 2·98 | 0·327 |

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||

| 20–24 v. 15–19 | 1·10 | 1·06, 1·15 | <0·001 | |||

| 25–29 v. 15–19 | 1·20 | 1·15, 1·26 | <0·001 | |||

| 30–34 v. 15–19 | 1·27 | 1·21, 1·33 | <0·001 | |||

| ≥35 v. 15–19 | 1·31 | 1·25, 1·37 | <0·001 | |||

| Maternal educational status | ||||||

| Primary v. no education | 1·43 | 1·39, 1·47 | <0·001 | |||

| Secondary or above v. no education | 1·72 | 1·67, 1·77 | <0·001 | |||

| Type of place of residence | ||||||

| Urban v. rural | 1·13 | 1·11, 1·16 | <0·001 | |||

| Maternal occupational status | ||||||

| Working v. not working | 1·29 | 1·26, 1·32 | <0·001 | |||

| Mass media exposure score | ||||||

| 1–3 v. 0 | 1·33 | 1·30, 1·36 | <0·001 | |||

| 4–6 v. 0 | 1·52 | 1·47, 1·57 | <0·001 | |||

| Sex of household head | ||||||

| Female v. male | 1·03 | 1·00, 1·05 | 0·068 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Currently in union/living with a man v. never in a union/formerly in a union | 1·03 | 1·00, 1·07 | 0·076 | |||

| Sex of child | ||||||

| Male v. female | 1·00 | 0·98, 1·02 | 0·930 | |||

| Age of child (months) | ||||||

| 12–23 v. 6–11 | 1·63 | 1·58, 1·69 | <0·001 | |||

| 24–35 v. 6–11 | 1·38 | 1·34, 1·43 | <0·001 | |||

| 36–47 v. 6–11 | 1·24 | 1·20, 1·28 | <0·001 | |||

| 48–59 v. 6–11 | 1·15 | 1·11, 1·19 | <0·001 | |||

| Contextual country factors | ||||||

| GDP per capita PPP (thousands) | 0·95 | 0·88, 1·03 | 0·240 | |||

| Proportion wıth media exposure score of 0 | 0·14 | 0·02, 0·82 | 0·029 | |||

| Random effects | ||||||

| Country-constant, variance | 0·486 | 0·363 | ||||

| se | 0·143 | 0·107 | ||||

GDP, gross domestic product, PPP, purchasing power parity.

Discussion

Achieving substantial reductions in child mortality means that all children aged 6–59 months living in affected areas need to receive high-dose vitamin A supplements every 4–6 months. UNICEF strives for at least 80 % coverage as a measure of strong and effective VAS programming( 10 ). The overall VAS coverage based on our data was 59·4 %, which is below this recommended minimal coverage level and indicates a need for policy makers and public health practioners in the region to scale up VAS among children aged 6–59 months.

The factors significantly associated with receipt of VAS among children aged 6–59 months were maternal age, maternal education, place of residence, maternal occupational status, media exposure index and age of child. Furthermore, at the country level, media exposure also affected VAS.

We observed that children with older mothers were more likely to receive VAS than children with teenage mothers. This finding is similar to that in a study by Aremu et al., which revealed that children with younger mothers were less likely to receive VAS( 15 ). These results may be explained by the fact that on the mother’s part, nutritional knowledge may increase with age( 32 ).

From our study, it is also envident that the mother’s educational status had a role in the reciept of VAS among children aged 6–59 months. Previous studies have also linked higher maternal educational status with receipt of VAS( 17 , 19 , 22 ). A plausible explanation for this finding is that formal education increases health and nutritional awareness vis-à-vis increasing awareness on the benefits of VAS.

Another study also found that rural children were approximately 10 % more likely never to have received a vitamin A supplement compared with their counterparts in urban locales( 7 ). The reasons for the disparity in VAS coverage between the two settings might be attributed to differences in accessabilty to health information and heath services, infrastructures and technological advancements.

In agreement with previously published studies( 13 , 15 ), children with working mothers where more likely to receive VAS compared with children with non-working mothers. This might be explained by the fact that working mothers have more access to information about the advantages of VAS and its use from sources such as peers in their workplace, or increased access to community mobilization efforts( 13 ).

In line with our study, previous studies have also shown an association between access to media and VAS coverage( 11 , 20 , 21 ). Gebremedhin( 23 ), in twenty-eight SSA countries, also reported that children in the age group 6–11 months had a lower likelihood of VAS. These results warrant further investigation in order to understand the factors leading to the age differential observed in the receipt of VAS.

The intra-country correlation coefficients suggest that 9·9 % of the total unexplained variation in VAS is attributable to unobserved country-level factors. Some other variables unaccounted for in the present study might have had an additional effect. Furthermore, after controlling for all study explanatory variables, Sierra Leone had a significantly higher likelihood of VAS than all but three of the other countries. This finding may be attributed to Sierra Leone having a higher proportion of women in the higher risk subgroup of VAS coverage with respect to background characteristics.

Study limitations and strengths

Coverage estimates from the DHS may be affected by the time interval between survey and mass supplementation and in addition, also subject to recall bias; however, estimates from the DHS can help inform improvements in routine coverage monitoring. It is also worth noting that difference in VAS delivery mechanisms between countries not accounted for in the present study might impact coverage. Future studies looking at VAS delivery mechanisms and coverage in SSA will help in enriching the knowledge on VAS in SSA. Futhermore, the cross-sectional nature of the data makes it possible to establish an association between VAS and explanatory variables but cannot establish causality. Although we controlled for potential confounding variables, there may have been confounding by other factors not included in the study. The main study’s strength lies in the fact that it is based on data that are nationally representative. In addition, information obtained from the study could be used in informing international efforts aimed at increasing VAS in SSA.

Conclusion

The coverage of VAS among children aged 6–59 months based on our data is not optimal and below the recommended minimal coverage level. The study highlighted groups at risk of non-receipt of VAS. Efforts are needed to scale up coverage in this region, mostly focusing on young, low-literate, rural and non-working mothers. It is also important to maximize the utilization of media channels during VAS campaigns.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018004056.

click here to view supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge Measure DHS for making available the data set for this study and Dr Nicole Claasen for her valuable suggestions and contribution to the manuscript. Funding source: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: A.S.B., P.B. and I.M.K. planned the study; A.S.B. wrote the manuscript; P.B. and I.M.K. made contributions to the interpretation of results and revised the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: The Ethics Committee of ICF International at Calverton, MD, USA and the National Ethics Committee of the various countries involved approved the DHS analysed in this study. Measure DHS gave permission to use and analyse the data set.

References

- 1. Sommer A & West KP (1996) Vitamin A Deficiency: Health, Survival and Vision. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Semba RD (2007) Handbook of Nutrition and Ophthalmology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3. UNICEF (2016) Current status and progress. https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/vitamin-a-deficiency/# (accessed October 2017).

- 4. Stevens GA, Bennett JE, Hennocq Q et al. (2015) Trends and mortality effects of vitamin A deficiency in children in 138 low-income and middle income countries between 1991 and 2013: a pooled analysis of population-based surveys. Lancet Glob Health 3, e528–e536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. UNICEF (2017) Vitamin A deficiency. https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/vitamin-a-deficiency/ (accessed October 2018).

- 6. Imdad A, Herzer K, Mayo-Wilson E et al. (2010) Vitamin A supplementation for preventing morbidity and mortality in children from 6 months to 5 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev issue 12, CD008524. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7. UNICEF (2017) Vitamin A Supplementation: A Decade of Progress. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mason JB, Ramirez MA, Fernandez CM et al. (2011) Effects on vitamin A deficiency in children of periodic high-dose supplements and of fortified oil promotion in a deficient area of the Philippines. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 81, 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horton S, Begin F, Grieg A et al. (2008) Micronutrient supplements for child survival (vitamin A and zinc). https://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/research/best-practice-papers/micronutrient-supplements-for-child-survival (accessed October 2018).

- 10. UNICEF (2018) Coverage at a Crossroads: New Directions for Vitamin A Supplementation Programmes. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Janmohamed A, Klemm RD & Doledec D (2017) Determinants of successful vitamin A supplementation coverage among children aged 6–59 months in thirteen sub-Saharan African countries. Public Health Nutr 20, 2016–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hodges MH, Sesay FF, Kamara HI et al. (2013) High and equitable mass vitamin A supplementation coverage in Sierra Leone: a post-event coverage survey. Glob Health Sci Pract 1, 172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haile D, Biadgilign S & Azage M (2015) Differentials in vitamin A supplementation among preschool-aged children in Ethiopia: evidence from the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. Public Health 129, 748–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Semba RD, de Pee S, Sun K et al. (2010) Coverage of vitamin A capsule programme in Bangladesh and risk factors associated with non-receipt of vitamin A. J Health Popul Nutr 28, 143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aremu O, Lawoko S & Dalal K (2010) Childhood vitamin A capsule supplementation coverage in Nigeria: a multilevel analysis of geographic and socioeconomic inequities. Scientific World J 10, 1901–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hadzi D, Asalu GA, Avedzi HM, et al. (2016) Vitamin A supplementation coverage and correlates of uptake among children 6–59 months in the South Dayi District, Ghana. Cent Afr J Public Health 2, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Choi Y, Bishai D & Hill K (2005) Socioeconomic differentials in supplementation of vitamin A: evidence from the Philippines. J Health Popul Nutr 23, 156–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adamu MD, & Muhammad N (2016) Assessment of vitamin A supplementation coverage and associated barriers in Sokoto State, Nigeria. Ann Nigerian Med 10, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grover DS, de Pee S, Sun K et al. (2008) Vitamin A supplementation in Cambodia: program coverage and association with greater maternal formal education. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 17, 446–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bendech MA, Cusack G, Konaté F et al. (2007) National vitamin A supplementation coverage survey among 6–59 months old children in Guinea (West Africa). J Trop Pediatr 53, 190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ayoya MA, Bendech MA, Baker SK et al. (2007) Determinants of high vitamin A supplementation coverage among pre-school children in Mali: the National Nutrition Weeks experience. Public Health Nutr 10, 1241–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Semba RD, de Pee S, Sun K et al. (2010) The role of expanded coverage of the national vitamin A program in preventing morbidity and mortality among preschool children in India. J Nutr 140, issue 1, 208S–212S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gebremedhin S (2017) Vitamin A supplementation and childhood morbidity from diarrhea, fever, respiratory problems and anemia in sub-Saharan Africa. Nutr Diet Suppl 9, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thapa S (2010) Nepal’s vitamin A supplementation programme, 15 years on: sustained growth in coverage and equity and children still missed. Glob Public Health 5, 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. United Nations Development Programme (2018) About Sub-Saharan Africa. http://www.africa.undp.org/content/rba/en/home/regioninfo.html (accessed November 2017).

- 26. ICF Macro (2017) The Demographic and Health Surveys Program. http://dhsprogram.com/ (accessed November 2017).

- 27. The World Bank (2017) GDP per capita, PPP (current international $). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD (accessed November 2017).

- 28. United Nations ( 2017. ) 2017 Revision of World Population Prospects. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/ (accessed November 2017).

- 29. Charlton C, Rasbash J, Browne WJ et al. (2017) MLwiN Version 3.00. Bristol: Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hedeker D & Robert G (1996) MIXOR: a computer program for mixed effects ordinal regression analysis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 49, 157–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goldstein H & Michael JRH (1995) The graphical presentation of a collection of means. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 158, 175–177. [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Vriendt T, Matthys C, Verbeke W et al. (2009) Determinants of nutrition knowledge in young and middle-aged Belgian women and the association with their dietary behaviour. Appetite 52, 788–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018004056.

click here to view supplementary material