Abstract

Background

The aim of the study was to analyze the relationship between pretreatment inflammatory biomarkers (IBs) and survival outcomes for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (neo‐CRT) and pembrolizumab.

Methods

Clinical variables and IBs (absolute monocyte count [AMC], absolute lymphocyte count [ALC], platelet count [PLT], neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio [NLR], platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio [PLR], lymphocyte‐to‐monocyte ratio [LMR], pan‐immune inflammation value [PIV], systemic immunoinflammatory index [SII], systemic immunoreactivity index [SIRI] and prognostic nutritional index [PNI]) were collected. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to identify the independent factors for outcomes of ESCC.

Results

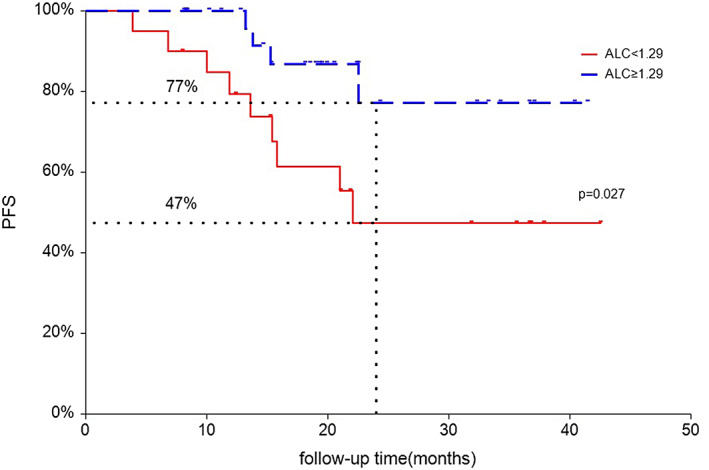

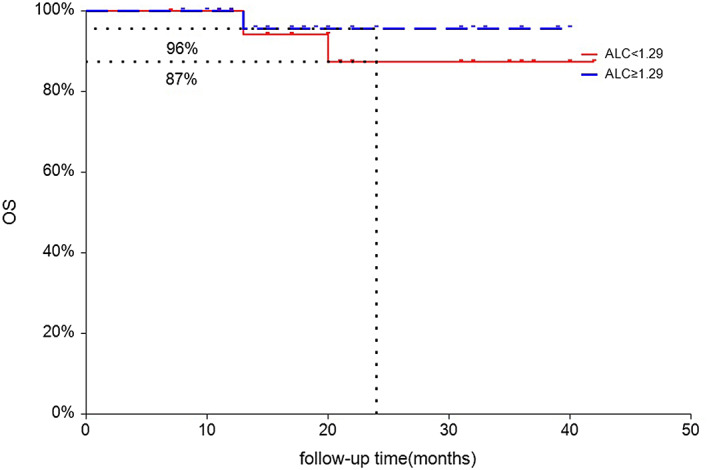

A total of 51 patients were included. Of these, 35 patients achieved pathological complete response (pCR) after neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab (pCR: 68.6%). With a median follow‐up of 20 months, the two‐year PFS and OS of the cohort was 64% and 91%, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that ALC (overall response [OR] 4.4, p = 0.051) and PLT (OR 6.7, p = 0.023) were two independent predictors for achieving pCR among ESCC treated with neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab. Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that ALC (HR 0.27, p = 0.028) and SIRI (HR 3.13, p = 0.048) were two independent predictors associated with PFS. Kaplan Meier analysis demonstrated that the PFS of ESCC with high baseline ALC was significantly better than those with low ALC (2‐year PFS: 77% vs. 47%, p = 0.027), but not for overall survival (2‐year OS: 96% vs. 87%, p = 0.46).

Conclusions

This retrospective analysis based on a prospective cohort for the first time demonstrates that pretreatment ALC is an independent predictor for achieving pCR and favorable outcomes of ESCC treated with neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab.

Keywords: absolute lymphocyte count, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, pathological complete response, pembrolizumab

Baseline absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) is associated with PFS among ESCC treated with neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab.

INTRODUCTION

According to the 2020 global cancer statistics, esophageal cancer ranks as the seventh most commonly diagnosed cancer, accounting for 604 000 new cases and the sixth in mortality with 544 000 deaths around the world. 1 In China, about 90% of the histological types are esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Since the publication of the CROSS 2 , 3 and NEOCRTEC 5010 trials, 4 , 5 neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (neo‐CRT) followed by curative surgery has become the standardized treatment for locally advanced esophageal cancer (LAEC). However, the prognosis for patients with LAEC remains poor with a 10‐year overall survival of 38%, and more than half of these patients develop cancer recurrence. 6 Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel and efficient treatments to improve the long‐term outcomes of LAEC patients.

In recent years, immunotherapies have revolutionized the treatment of advanced solid tumors including esophageal cancer. Among them, the PD‐1/PD‐L1 pathway is a major checkpoint pathway for immune responses, which has been a common mechanism of immune escape used by tumor cells. 7 , 8 Therefore, multiple phase III trials have been conducted to investigate the efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) for the treatment of LAEC. Indeed, several large phase III trials, including ATTRACTION‐3, CheckMate 648, KEYNOTE‐181 and KEYNOTE‐590, have confirmed that ICIs alone, or combined with chemotherapy as first‐ or second‐line therapy, significantly improved the outcomes of LAEC when compared to controls. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 However, the role of ICIs as neoadjuvant treatment for ESCC remains unknown. We thus performed a prospective phase I trial (PALACE‐1) to investigate the efficacy and toxicity of neoadjuvant CRT combined pembrolizumab for LAEC, and the addition of ICIs to neo‐CRT induced a pathological complete response (pCR) of 55.6% for resected tumors. 9 A phase II multicenter study (PALACE‐2) is also underway to further confirm our findings.

Prior to the present study, multiple studies have been performed and demonstrated that the inflammation‐based index, such as the neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio (NLR), 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio (PLR), 15 , 16 , 17 and prognostic nutritional index (PNI) 18 , 19 , 20 are significantly associated with outcomes in LAEC patients treated with neoadjuvant CRT. More recently, Wu et al. 21 performed a retrospective study and found that NLR at 6 weeks post treatment is a predictor of the response to anti‐PD‐1 treatment in patients with ESCC. However, there is a lack of studies which have assessed the relationship between hematological biomarkers and outcomes of ESCC patients treated with neo‐CRT with ICIs. As a result, we performed the present study to comprehensively identify hematological biomarkers associated with outcomes of ESCC treatment with neo‐CRT with ICIs in order to tailor the treatments.

METHODS

Data collection

A total of 51 patients with ESCC treated with CRT and pembrolizumab were prospectively collected at the Department of Radiation Oncology, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine between March 2019 and March 2022 in two prospective trials (PALACE‐1, NCT04435197l; part of enrolled patients in PALACE‐2: NCT04435197), and approved by the ethics committee of Ruijin Hospital. The latest follow‐up time was June 20, 2022. All procedures were conducted according to the institutional and national standards on human experimentation and with the declaration of Helsinki of 1964.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been reported in our previous study. 9 Medical records were reviewed and the following information including age at diagnosis, baseline ECOG performance status, sex, baseline weight and height and smoking/drinking history, comorbidities, BMI (body mass index), tumor location of ESCC (upper, middle, lower segment), tumor length (cm), histological types, primary tumor (T) stage, regional lymph nodes (N) stage, distant metastasis (M) stage, clinical TNM stage according to eighth AJCC, start and completion of neo‐CRT, surgery time, time interval between completion of neo‐CRT end and surgery, the peripheral inflammatory biomarkers (IBs) before treatment including baseline absolute neutrophil count, absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), absolute monocyte count (AMC), absolute platelet count and absolute leukocyte count, albumin (g/L), and C reactive protein (CRP) were recorded. Moreover, the pathological results and the pCR status after surgery was recorded. The primary outcome of the present study was to identify the independent IBs for predicting pCR, which was defined as no evidence of vital residual tumor cells. The secondary outcome of the study was to identify the independent IBs for predicting favorable progression‐free survival (PFS), which was defined as the time from diagnosis of esophageal cancer to the time of disease progression or death/last follow‐up.

Neoadjuvant CRT regimen

The chemotherapy regimen consisted of carboplatin (area under the curve of 2 mg/mL per min) and paclitaxel (50 mg/m2 of body surface area), which were administered intravenously on days 1, 8, 15, 22. Concurrent radiotherapy was performed on day 1 of chemotherapy with a total dose of 41.4 Gy in 23 fractions, on five fractions per week. The gross tumor volume (GTV) was determined by the contrast‐enhanced CT, barium swallow, endoscopic examination, or PET‐CT, which contained both the primary tumor (GTVp) and the positive regional lymph nodes (GTVn). The clinical target volume included the GTVp with an additional 3.0‐cm proximal and distal margin and 0.5 cm radial margin, as well as GTVn with 0.5 cm uniform margin. The planning target volume was expanded to include a 0.5 cm margin from the clinical target volume for setup variations and respiratory‐induced tumor motion. Pembrolizumab was given on days 1 and 22 of the neoadjuvant therapy at a dose of 200 mg. After the completion of neoadjuvant treatment, all patients received curative surgery excluding those patients where there was a contraindication to surgery. During the first year after treatment completion, patients were followed‐up every 3 months, and once every 6 months thereafter.

Definition of inflammatory biomarkers

All hematological examinations were tested before neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab. Inflammatory biomarkers (IBs) were defined as follows: NLR = (the ratio of neutrophil count to lymphocyte count);22 LMR = (the ratio of lymphocyte count to monocyte count);23 PLR = (the ratio of platelet count to lymphocyte count). 24 The PNI was the sum of albumin value (g/L) and five times lymphocyte count (109/L);25 SII = (platelet count) × NLR; 26 , 27 SIRI = neutrophils × monocytes/lymphocytes; 28 PIV = (neutrophil count × platelet count × monocyte count)/lymphocyte count29, 30 BMI = weight (kg)/height (m)2. 31

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of included patients were simply described by using frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables of IBs were converted into binary variables by measuring the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Univariate and multivariate logistic‐regression analyses were performed to investigate predictors for pCR. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was performed for identifying factors associated with PFS. Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate PFS, and the log‐rank test was applied to test statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted through MedCalc version 19.6.4 statistical software.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. All patients received neo‐CRT combined with pembrolizumab before radical surgery. Of these, the median age of patients was 62 years, and 51 (100%) had a performance status of 1 or less. There were 44 male and seven female patients. As for smoking histology, 13 patients had no history of smoking, while 38 patients had a history of smoking. All 51 ESCC patients were treated with esophagectomy after neoadjuvant treatment. Of these, 35 patients achieved pCR (68.6%). A total of 44 patients (86.3%) achieved disease progression‐free survival until the last follow‐up on June 20, 2022 (Table 1); the two‐year PFS and OS of the cohort was 64% and 91%, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patients.

| Variable | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Median, (range) | 62 (39–75) years | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 44 | 86.3 |

| Female | 7 | 13.7 |

| Histology | ||

| SCC | 51 | 100 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Yes | 22 | 43.1 |

| No | 29 | 56.9 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 38 | 74.5 |

| No | 13 | 25.5 |

| Drinking | ||

| Yes | 32 | 62.7 |

| No | 19 | 37.3 |

| Tumor location | ||

| Upper thoracic | 11 | 21.6 |

| Middle thoracic | 13 | 25.5 |

| Low thoracic | 27 | 52.9 |

| Tumor length, cm | 4.7 (range: 1.2–14 cm) | |

| cT stage | ||

| T3 | 43 | 84.3 |

| T4 | 8 | 15.7 |

| cN stage | ||

| N0–1 | 18 | 35.3 |

| N2–3 | 33 | 64.7 |

| Stage | ||

| II–IIIA | 16 | 31.4 |

| IIIB | 20 | 39.2 |

| IVA | 15 | 29.4 |

| ECOG status | ||

| 0 | 26 | 51 |

| 1 | 25 | 49 |

| BMI | 22.83 (range: 17.1–28.93) | ‐ |

| Time interval from radiation to surgery, days | 52 (range: 34–99) | ‐ |

| pCR | ||

| Yes | 35 | 68.6 |

| No | 16 | 31.4 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; LMR, lymphocyte‐to‐monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; pCR, pathological complete response; PFS, progression‐free survival; PIV, pan‐immune inflammation value; PLR, platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutrition index; SII, systemic immune‐inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index.

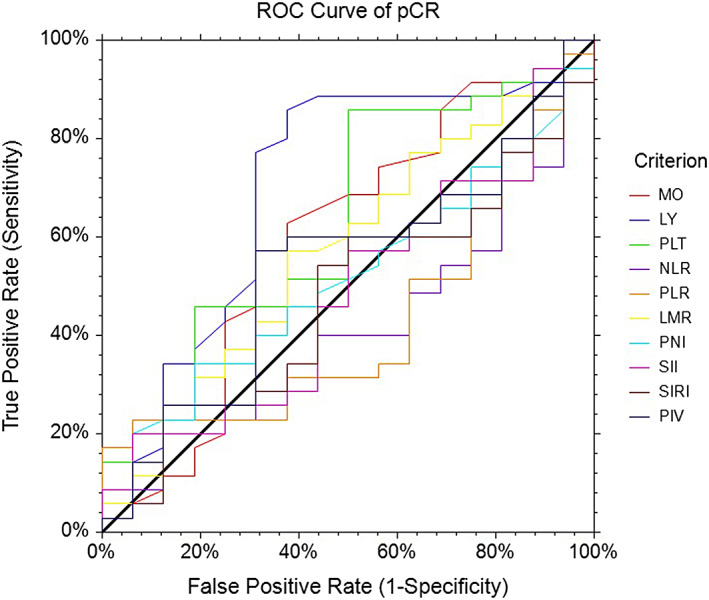

Optimal cutoff analysis

We performed ROC curve analysis to evaluate the predictive capability of these IBs for pCR and PFS. The optimal cutoff values of the ALC, AMC, PLT, NLR, PLR, LMR, PNI, SII, SIRI and PIV are listed in Table 2 and Figure 1.

TABLE 2.

The optimal cutoff value for serum markers by ROC curves.

| Serum markers | Cutoff value |

|---|---|

| Tumor length | 2.8 cm |

| Time interval | 53 days |

| BMI | 25 |

| LY | 1.29 × 109/L |

| Mo | 0.4 × 109/L |

| PLT | 162 × 109/L |

| NLR | 2.60 |

| PLR | 150.63 |

| LMR | 3.36 |

| PNI | 52.35 |

| SII | 373.81 |

| SIRI | 0.94 |

| PIV | 232.83 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; LMR, lymphocyte‐to‐monocyte ratio; LY, lymphocytes; Mo, monocytes; NLR, neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; PIV, pan‐immune inflammation value; PLR, platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; PLT, platelets; PNI, prognostic nutrition index; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SII, systemic immune‐inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index.

FIGURE 1.

ROC curve of the preoperative inflammation markers for pCR. pCR, pathological complete response, ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Logistic regression analysis for factors associated with pCR

Data regarding age, ECOG performance status, smoking status, white blood cell count (WBC), neuron specific enolase (NSE), lymphocytes (LY), monocytes (MO), platelets (PLT), NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, SIRI, PNI and PIV score are included in the univariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3). Univariate logistic analysis indicated that T stage (overall response [OR] 0.21, p = 0.051), ALC (OR 6.36, p = 0.0053), PLT (OR 6.0000, p = 0.001), and AMC (OR 2.82, p = 0.096) were potentially related to achieving pCR after neo‐CRT. Given the limitations of univariate analysis, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed and indicated that ALC (OR 4.4, p = 0.051), and PLT (OR 6.7, p = 0.023) were two independent predictors for achieving pCR among ESCC patients treated with neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic analysis for factors for predicting pCR.

| Factors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR, 95% CI | p‐value | RR, 95% CI | p‐value | |

| Age | ||||

| ≤60 | 1 | |||

| >60 | 2.00 (0.54–7.47) | 0.30 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 | |||

| Male | 0.86 (0.15–4.97) | 0.86 | ||

| BMI | ||||

| ≤25 | 1 | |||

| >25 | 1.04 (0.27–4.05) | 0.96 | ||

| T stage | ||||

| cT3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| cT4 | 0.21 (0.042–1.01) | 0.051 | 0.13 (0.017–1.09) | 0.061 |

| N stage | ||||

| cN0–1 | 1 | |||

| cN2–3 | 0.77 (0.22–2.71) | 0.68 | ||

| Stage | ||||

| III | 1 | |||

| IVA | 0.51 (0.15–1.76) | 0.29 | ||

| Time interval | ||||

| ≤53 days | 1 | |||

| >53 days | 3.39 (0.66–17.56) | 0.15 | ||

| Tumor length | ||||

| ≤2.8 cm | 1 | |||

| >2.8 cm | 6.00 (0.70–51.66) | 0.10 | ||

| CRP | ||||

| <10 | 1 | |||

| ≥10 | 2.80 (0.54–14.63) | 0.22 | ||

| Absolute lymphocyte count | ||||

| <1.29 × 109/L | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥1.29 × 109/L | 6.36 (1.73–23.34) | 0.0053 | 4.40(1.00–19.46) | 0.051 |

| Absolute monocyte count | ||||

| <0.4 × 109/L | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥0.4 × 109/L | 2.82 (0.83–9.58) | 0.096 | 2.54 (0.53–12.05) | 0.24 |

| PLT | ||||

| <162 × 109/L | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥162 × 109/L | 6.00 (1.54–23.44) | 0.001 | 6.7 (1.30–34.42) | 0.023 |

| NLR | ||||

| <2.6 | 1 | |||

| ≥2.6 | 3.25 (0.78–13.48) | 0.10 | ||

| PLR | ||||

| <150.6 | 1 | |||

| ≥150.6 | 2.82 (0.83–9.58) | 0.096 | ||

| LMR | ||||

| <3.36 | 1 | |||

| ≥3.36 | 1.71 (0.52–5.65) | 0.38 | ||

| PNI | ||||

| <52.35 | 1 | |||

| ≥52.35 | 2.261 (0.54–9.51) | 0.27 | ||

| SII | ||||

| <373.8 | 1 | |||

| ≥373.8 | 2.42 (0.46–12.80) | 0.30 | ||

| SIRI | ||||

| <0.94 | 1 | |||

| ≥0.94 | 1.99 (0.47–8.42) | 0.35 | ||

| PIV | ||||

| <232.8 | 1 | |||

| ≥232.8 | 0.45 (0.13–1.51) | 0.20 | ||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; LMR, lymphocyte‐to‐monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; pCR, pathological complete response; PFS, progression‐free survival; PIV, pan‐immune inflammation value; PLR, platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutrition index; SII, systemic immune‐inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index.

Cox regression analysis for factors associated with PFS

Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that ALC (HR 0.29, p = 0.038) and SIRI (HR 2.82, p = 0.075) were significantly related to PFS of ESCC. Given the limitations of univariate analysis, multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to investigate the independent factors associated with PFS (Table 4). Our findings showed that ALC (HR 0.27, p = 0.028) and SIRI (HR 3.13, p = 0.048) were two independent predictors for PFS of ESCC treated with neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab (Table 4). Kaplan Meier analysis showed that the PFS of ESCC with high level of baseline ALC (LY ≥ 1.29 × 109/L) was significantly better than those with low baseline (LY <1.29 × 109/L) ALC groups (2‐year PFS: 77% vs. 47%, p = 0.027, Figure 2), but not for overall survival (2‐year OS: 96% vs. 87%, p = 0.46, Figure 3).

TABLE 4.

Univariate and multivariate Cox‐regression analysis for factors associated with PFS.

| Factors | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR, 95% CI | p‐value | HR, 95% CI | p‐value | |

| Age | ||||

| ≤60 | 1 | |||

| >60 | 0.81 (0.25–2.65) | 0.73 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 | |||

| Male | 0.59 (0.13–2.67) | 0.49 | ||

| KPS score | ||||

| 90 | 1 | |||

| 100 | 0.95 (0.31–2.94) | 0.93 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 0.48 (0.16–1.48) | 0.20 | ||

| Alcohol drinking status | ||||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.04 (0.34–3.19) | 0.95 | ||

| BMI | ||||

| ≤25 | 1 | |||

| >25 | 1.17 (0.62–6.67) | 0.24 | ||

| T stage | ||||

| cT3 | 1 | |||

| cT4 | 1.15 (0.32–4.21) | 0.83 | ||

| N stage | ||||

| cN0‐1 | 1 | |||

| cN2‐3 | 0.64 (0.22–1.92) | 0.43 | ||

| Stage | ||||

| III | 1 | |||

| IVA | 1.28 (0.42–3.93) | 0.66 | ||

| Time interval | ||||

| ≤53 days | 1 | |||

| >53 days | 1.19 (0.26–5.55) | 0.82 | ||

| Tumor length | ||||

| ≤2.8 cm | 1 | |||

| >2.8 cm | 0.92 (0.20–4.17) | 0.91 | ||

| CRP | ||||

| <10 | 1 | |||

| ≥10 | 1.44 (0.32–6.57) | 0.64 | ||

| Absolute lymphocyte count | ||||

| <1.29 × 109/L | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥1.29 × 109/L | 0.29 (0.088–0.94) | 0.038 | 0.27(0.08–0.87) | 0.028 |

| Absolute monocyte count | ||||

| <0.4 × 109/L | 1 | |||

| ≥0.4 × 109/L | 0.50 (0.17–1.48) | 0.21 | ||

| PLT | ||||

| <162 × 109/L | 1 | |||

| ≥162 × 109/L | 1.33 (0.37–4.83) | 0.67 | ||

| NLR | ||||

| <2.6 | 1 | |||

| ≥2.6 | 1.45 (0.47–4.47) | 0.52 | ||

| PLR | ||||

| <150.6 | 1 | |||

| ≥150.6 | 0.81 (0.27–2.40) | 0.70 | ||

| LMR | ||||

| <3.36 | 1 | |||

| ≥3.36 | 1.22 (0.41–3.65) | 0.72 | ||

| PNI | ||||

| <52.35 | 1 | |||

| ≥52.35 | 1.22 (0.41–3.65) | 0.72 | ||

| SII | ||||

| <373.8 | 1 | |||

| ≥373.8 | 0.78 (0.17–3.55) | 0.75 | ||

| SIRI | ||||

| <0.94 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥0.94 | 2.82 (0.90–8.85) | 0.075 | 3.13 (1.01–9.71) | 0.048 |

| PIV | ||||

| <232.8 | 1 | |||

| ≥232.8 | 0.48 (0.16–1.46) | 0.20 | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LMR, lymphocyte‐to‐monocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; PFS, progression‐free survival; PIV, pan‐immune inflammation value; PLR, platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutrition index; SII, systemic immune‐inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammation response index.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for progression‐free survival (PFS) according to baseline absolute lymphocyte count (ALC). Red line indicates patients with low lymphocytes (LY) (<1.29 × 109/L), and blue line indicates patients with high LY (≥1.29 × 109/L).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for OS according to baseline absolute lymphocyte count (ALC). Red line indicates patients with low lymphocytes (LY) (<1.29 × 109/L), and blue line indicates patients with high LY (≥1.29 × 109/L).

Treatment complications

Of the 51 patients available with acute toxicity following neoadjuvant treatment, the most common hematological toxicities were leukocytopenia and lymphopenia (Table 5). Two patients experienced grade III leukocytopenia and one patient experienced grade IV leukocytopenia. A total of 17 patients experienced grade III lymphopenia and one patient experienced grade IV lymphopenia. The most common nonhematological toxicity was esophagitis (grade 1: 31.4% and grade 2: 19.6%). Additionally, six patients experienced grade I pneumonia.

TABLE 5.

Treatment toxicities of neoadjuvant CRT and pembrolizumab.

| Toxicities | NCI‐CTC grade (n = 51) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| Hematological | ||||||||||||

| Leukocytopenia | 6 | 11.8 | 11 | 21.6 | 31 | 60.8 | 2 | 3.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 17 | 33.3 | 21 | 41.2 | 9 | 17.6 | 2 | 3.9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anemia | 18 | 35.3 | 26 | 51 | 7 | 13.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 33 | 64.7 | 2 | 3.9 | 12 | 23.5 | 4 | 7.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Glutamic pyruvic transaminase increased | 46 | 90.2 | 2 | 3.9 | 2 | 3.9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase increased | 46 | 90.2 | 2 | 3.9 | 2 | 3.9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nonhematological | ||||||||||||

| Esophagitis | 25 | 49 | 16 | 31.4 | 10 | 19.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 45 | 88.2 | 6 | 11.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 40 | 78.4 | 8 | 15.7 | 3 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Immune dermatitis | 49 | 96.1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

DISCUSSION

During the past decade, the introduction of ICIs for the treatment of cancer has significantly changed the clinical treatment practice of solid tumors, including ESCC. The ATTRACTION‐3 trial 32 demonstrated that nivolumab as second‐line therapy for ESCC significantly improved long‐term OS compared with chemotherapy (median, 10.9 vs. 8.5 months; HR, 0.79; p = 0.0264), with three‐year OS rates of 15.3% and 8.7%, respectively. Similarly, KEYNOTE‐181 33 showed that pembrolizumab prolonged OS versus chemotherapy as second‐line therapy for advanced esophageal cancer in patients with PD‐L1 CPS ≥10 (median, 9.3 vs. 6.7 months; HR, 0.69, p = 0.0074). More recently, KEYNOTE‐590 34 found that pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy improved OS when compared with placebo plus chemotherapy as first‐line therapy for esophageal cancer with PD‐L1 CPS of 10 or more (median 13·9 vs. 8·8 months; HR 0·57, p < 0.0001). Recently, immunotherapy has gained increasing attention in the era of neoadjuvant treatment of ESCC, and several clinical trials have also reported a pCR with 25%–55.6%. However, the role of ICIs in the treatment for resectable EC remains unknown in the era of neo‐CRT.

Immunotherapy has gained increasing attention in the era of neoadjuvant treatment of ESCC, and several clinical trials have also reported pCR with 25%–55.6%. 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 As a result, our team performed PALACE trials to investigate the efficacy and toxicities of neo‐CRT combined with pembrolizumab in patients with locally advanced ESCC. In the present study of 51 patients, 35 patients achieved pCR (68.6%), which is encouraging. However, the clinical benefits obtained from neo‐CRT and ICI therapy is not universal for all EC patients. Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify the optimal candidate patients who could most benefit from neo‐CRT combined ICI therapy.

Prior to the present study, multiple studies have demonstrated that various clinical IBs, such as NLR, LMR, and PLR, are significantly associated with clinical outcomes in numerous types of cancer, as cancer‐related inflammation plays an important role in cancer development and disease progression. 38 Recent research has focused on the potential predictor for cancer patients treated with ICIs, and several inflammatory indexes, such as the NLR, 39 , 40 nutritional index, 41 LMR, 42 have also been reported as potential predictors of the effectiveness of anti‐PD‐1 antibody therapy. However, the prognostic of inflammatory and nutritional indexes in ESCC treated with neo‐CRT and ICIs remains unknown. In the present study, we demonstrate that a higher level of baseline peripheral ALC indicates a better survival outcome and archiving pCR when compared to low level of ALC among ESCC patients treated with neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab. One possible explanation for this finding is that lymphocytes play an essential role in mediating cellular immunity against tumor cells. A high level of lymphocytes could enhance the lymphocyte‐medicated antitumor immune response when concurrently used with pembrolizumab. Another possible explanation is that pretreatment ALC might be associated with disease status. Van Rossum et al. reported that patients with a lower baseline ALC were found to have the highest probability of developing grade 4 lymphopenia during CRT for esophageal cancer. 43 Ray‐Coquard et al. reported that lymphopenia was significantly more frequent (p < 0.05) in metastatic breast cancer patients with performance status of >1. 44 Fogar et al. found that lower circulating lymphocytes were found in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who presented at advanced stages (stage IIB–IV, p < 0.05) compared with stages 0 to IIA. 45 Based on our findings, for patients with baseline low level of ALC, radiation oncologists should pay more attention to the radiation field in order to protect the lymphocytes and the host immune system. In the present study, all patients were treated with involved field irradiation (IFI), CTV consisting of GTV with 3‐cm craniocaudal margin and only the malignant node is irradiated in order to decrease irradiation volume and achieve a pCR of 68.4%. Consistent with previous findings, 46 , 47 we also found that cT stage and baseline PLT count are two independent predictors for achieving pCR among ESCC patients treated with neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab.

The major strength of the present study is that it is an analysis based on a prospective cohort. Therefore, all patients included were treated with the predefined neo‐CRT with pembrolizumab according to the trial protocol. However, there are several limitations. First, despite the prospective nature of the included patients, this was a retrospective analysis of the prospective trial and baseline IBs were not the primary endpoints for analysis. Second, the sample size is small, and patients might be highly selected and from a single center; therefore, these factors may have restricted the generalizability of our results. Third, the median follow‐up time for the present study is 20 months. Therefore, the 2‐year survival outcomes of the present study might be inadequate, and the long‐term outcomes should be reported in order to confirm our findings. Finally, the cutoff value of ALC might vary among different studies and further studies are still needed to confirm our findings and identify the optimal value of baseline ALC value.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that pretreatment ALC is an independent predictor for achieving pCR and favorable outcomes among ESCC treated with neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab. We also determined that clinical T stage and baseline PLT are two independent predictors for achieving pCR in ESCC patients treated with neo‐CRT and pembrolizumab. Further multicenter and larger clinical trials should be performed to confirm our findings.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Jiayi Chen, Shengguang Zhao and Hecheng Li; Project administration: Jiayi Chen and Shengguang Zhao; Methodology: Wei‐Xiang Qi, Shengguang Zhao, Jiayi Chen; Data Curation: Xiaoyan Wang, Huan Li, and Shuyan Li; Formal analysis: Wei‐Xiang Qi. Manuscript preparation: Wei‐Xiang Qi, Chengqiang Li, Huan Li, Jiayi Chen, Shengguang Zhao prepared Figures 1–5: Feifei Xu and Xiaoyan Wang. All authors reviewed the manuscript; Final approval of manuscript: all authors.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (SHDC2020CR2052B, SHDC2020CR4070); Special construction of integrated Chinese and Western medicine in general hospital (ZHYY‐ZXYJHZ X‐2‐201913).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Qi W‐X, Wang X, Li C, Li S, Li H, Xu F, et al. Pretreatment absolute lymphocyte count is an independent predictor for survival outcomes for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and pembrolizumab: An analysis from a prospective cohort. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14(17):1556–1566. 10.1111/1759-7714.14898

Wei‐Xiang Qi, Xiaoyan Wang, and Chengqiang Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jiayi Chen, Email: cjy11756@rjh.com.cn.

Shengguang Zhao, Email: zsg10935@rjh.com.cn.

Hecheng Li, Email: lihecheng2000@hotmail.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Raw data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (S.Z.) on request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof M, van Hagen P, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BPL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long‐term results of a randomised controlled trial, the lancet. Oncology. 2015;16:1090–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. New Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang H, Liu H, Chen Y, Zhu C, Fang W, Yu Z, et al. Long‐term efficacy of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery for the treatment of locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the NEOCRTEC5010 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surgery. 2021;156:721–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang H, Liu H, Chen Y, Zhu C, Fang W, Yu Z, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery versus surgery alone for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (NEOCRTEC5010): a phase III multicenter, randomized, open‐label clinical trial. Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eyck BM, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof M, van der Wilk BJ, Shapiro J, van Hagen P, et al. Ten‐year outcome of Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy plus surgery for esophageal cancer: the randomized controlled CROSS trial. Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1995–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buque A, Bloy N, Aranda F, Castoldi F, Eggermont A, Cremer I, et al. Trial watch: immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies for oncological indications. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;4:e1008814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gou Q, Dong C, Xu H, Khan B, Jin J, Liu Q, et al. PD‐L1 degradation pathway and immunotherapy for cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li C, Zhao S, Zheng Y, Han Y, Chen X, Cheng Z, et al. Preoperative pembrolizumab combined with chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (PALACE‐1). Eur J Cancer. 2021;144:232–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feng JF, Huang Y, Chen QX. Preoperative platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is superior to neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a predictive factor in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen MF, Chen PT, Kuan FC, Chen WC. The predictive value of pretreatment neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:190–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fu X, Li T, Dai Y, Li J. Preoperative systemic inflammation score (SIS) is superior to neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a predicting indicator in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo Q, Shao Z, Xu D, Fan L, Xiong H, Ding X, et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio in peripheral blood and pathological tissue in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Medicine. 2020;99:e21306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoshino S, Takeuchi M, Kawakubo H, Matsuda S, Mayanagi S, Irino T, et al. Usefulness of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio at recurrence for predicting long‐term outcomes in patients with recurrent esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:3001–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sun Y, Zhang L. The clinical use of pretreatment NLR, PLR, and LMR in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: evidence from a meta‐analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:6167–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhi X, Jiang K, Shen Y, Su X, Wang K, Ma Y, et al. Peripheral blood cell count ratios are predictive biomarkers of clinical response and prognosis for non‐surgical esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with radiotherapy. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang C, Tong J, Tang M, Lu Y, Liang G, Zhang Z, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio and platelet‐to‐lymphocyte ratio as prognostic factors and reference markers of treatment options for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma located in the middle and upper esophagus. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:1075–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cai G, Yu J, Meng X. Predicting prognosis and adverse events by hematologic markers in patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:8497–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shang QX, Yang YS, Hu WP, Yuan Y, He Y, Zhao JY, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of preoperative lymphocyte‐monocyte ratio, neutrophil‐lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil‐monocyte ratio on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9:3903–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu Y, Chen J, Zhao L, Li Q, Zhu J, Yang H, et al. Prediction of pathologic response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma incorporating hematological biomarkers. Cancer Res Treatment. 2021;53:172–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu X, Han R, Zhong Y, Weng N, Zhang A. Post treatment NLR is a predictor of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Valero C, Lee M, Hoen D, Weiss K, Kelly DW, Adusumilli PS, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio and mutational burden as biomarkers of tumor response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2021;12:729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xiao L, Li L, Chen G, Zhang Y, Gao Q. The lymphocyte‐to‐monocyte ratio could predict the efficacy of PD‐1 inhibitors in patients with advanced cancer, Transl. Cancer Res. 2020;9:4111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Qi WX, Xiang Y, Zhao S, Chen J. Assessment of systematic inflammatory and nutritional indexes in extensive‐stage small‐cell lung cancer treated with first‐line chemotherapy and atezolizumab. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021;70:3199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shoji F, Takeoka H, Kozuma Y, Toyokawa G, Yamazaki K, Ichiki M, et al. Pretreatment prognostic nutritional index as a novel biomarker in non‐small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 2019;136:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Giorgi U, Procopio G, Giannarelli D, Sabbatini R, Bearz A, Buti S, et al. Association of Systemic Inflammation Index and Body Mass Index with survival in patients with renal cell cancer treated with Nivolumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3839–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bauckneht M, Genova C, Rossi G, Rijavec E, Dal Bello MG, Ferrarazzo G, et al. The role of the immune metabolic prognostic index in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in radiological progression during treatment with Nivolumab. Cancers. 2021;13:3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhao M, Duan X, Han X, Wang J, Han G, Mi L, et al. Sarcopenia and systemic inflammation response index predict response to systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and are associated with immune cells. Front Oncol. 2022;12:854096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Corti F, Lonardi S, Intini R, Salati M, Fenocchio E, Belli C, et al. The Pan‐immune‐inflammation value in microsatellite instability‐high metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2021;150:155–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zeng R, Liu F, Fang C, Yang J, Luo L, Yue P, et al. PIV and PILE score at baseline predict clinical outcome of anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitor combined with chemotherapy in extensive‐stage small cell lung cancer patients. Front Immunol. 2021;12:724443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cortellini A, Bersanelli M, Santini D, Buti S, Tiseo M, Cannita K, et al. Another side of the association between body mass index (BMI) and clinical outcomes of cancer patients receiving programmed cell death protein‐1 (PD‐1)/ programmed cell death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) checkpoint inhibitors: a multicentre analysis of immune‐related adverse events. Eur J Cancer. 2020;128:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Okada M, Kato K, Cho BC, Takahashi M, Lin CY, Chin K, et al. Three‐year follow‐up and response‐survival relationship of nivolumab in previously treated patients with advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ATTRACTION‐3). Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:3277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kojima T, Shah MA, Muro K, Francois E, Adenis A, Hsu CH, et al. K.‐. investigators, randomized phase III KEYNOTE‐181 study of Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced esophageal cancer. Clin Oncol. 2020;38:4138–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sun JM, Shen L, Shah MA, Enzinger P, Adenis A, Doi T, et al. K.‐. investigators, Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first‐line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE‐590): a randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2021;398:759–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu J, Li J, Lin W, Shao D, Depypere L, Zhang Z, et al. Neoadjuvant camrelizumab plus chemotherapy for resectable, locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (NIC‐ESCC2019): a multicenter, phase 2 study. Int J Cancer. 2022;151:128–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yan X, Duan H, Ni Y, Zhou Y, Wang X, Qi H, et al. Tislelizumab combined with chemotherapy as neoadjuvant therapy for surgically resectable esophageal cancer: a prospective, single‐arm, phase II study (TD‐NICE). Int J Surg. 2022;103:106680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shen D, Chen Q, Wu J, Li J, Tao K, Jiang Y. The safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant PD‐1 inhibitor with chemotherapy for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer‐related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Petrova MP, Eneva MI, Arabadjiev JI, Conev NV, Dimitrova EG, Koynov KD, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a potential predictive marker for treatment with pembrolizumab as a second line treatment in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer. Biosci Trends. 2020;14:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matsubara T, Takamori S, Haratake N, Toyozawa R, Miura N, Shimokawa M, et al. The impact of immune‐inflammation‐nutritional parameters on the prognosis of non‐small cell lung cancer patients treated with atezolizumab. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:1520–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ohba T, Takamori S, Toyozawa R, Nosaki K, Umeyama Y, Haratake N, et al. Prognostic impact of the controlling nutritional status score in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:3757–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Failing JJ, Yan Y, Porrata LF, Markovic SN. Lymphocyte‐to‐monocyte ratio is associated with survival in pembrolizumab‐treated metastatic melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2017;27:596–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Rossum PSN, Deng W, Routman DM, Liu AY, Xu C, Shiraishi Y, et al. Prediction of severe Lymphopenia during chemoradiation therapy for esophageal cancer: development and validation of a pretreatment nomogram. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2020;10:e16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ray‐Coquard I, Cropet C, Van Glabbeke M, Sebban C, Le Cesne A, Judson I, et al. Bone sarcoma, Lymphopenia as a prognostic factor for overall survival in advanced carcinomas, sarcomas, and lymphomas. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5383–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fogar P, Sperti C, Basso D, Sanzari MC, Greco E, Davoli C, et al. Decreased total lymphocyte counts in pancreatic cancer: an index of adverse outcome. Pancreas. 2006;32:22–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xie J, Pang Y, Li X, Wu X. The log odds of negative lymph nodes/T stage: a new prognostic and predictive tool for resected gastric cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2021;147:2259–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Deng J, Chu X, Ren Z, Wang B. Relationship between T stage and survival in distantly metastatic esophageal cancer: a STROBE‐compliant study. Medicine. 2020;99:e20064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (S.Z.) on request.