Abstract

Objective:

Dietary guidelines are an essential policy tool for facilitating optimal dietary patterns and healthy eating behaviours. We report: (i) the methodological approach adopted for developing the National Dietary Guidelines of Greece (NDGGr) for Infants, Children and Adolescents; and (ii) the guidelines for children aged 1–18 years.

Design:

An evidence-based approach was employed to develop food-based recommendations according to the methodologies of the WHO, FAO and European Food Safety Authority. Physical activity recommendations were also compiled. Food education, healthy eating tips and suggestions were also provided.

Setting:

The NDGGr encompass food-based nutritional and physical activity recommendations for promoting healthy dietary patterns and eating behaviours and secondarily to serve as a helpful tool for the prevention of childhood overweight and obesity.

Results:

The NDGGr include food-based recommendations, food education and health promotion messages regarding: (i) fruits; (ii) vegetables; (iii) milk and dairy products; (iv) cereals; (v) red and white meat; (vi) fish and seafood; (vii) eggs; (viii) legumes; (ix) added lipids, olives, and nuts; (x) added sugars and salt; (xi) water and beverages, and (xii) physical activity. A Nutrition Wheel, consisting of the ten most pivotal key messages, was developed to enhance the adoption of optimal dietary patterns and a healthy lifestyle. The NDGGr additionally provide recommendations regarding the optimal frequency and serving sizes of main meals, based on the traditional Greek diet.

Conclusions:

As a policy tool for promoting healthy eating, the NDGGr have been disseminated in public schools across Greece.

Keywords: Dietary guidelines, Greece, Childhood obesity, Adolescent obesity

Healthy eating is important in all life stages. For children and adolescents, in particular, healthy eating is essential for ensuring optimal physical and cognitive development( 1 – 3 ). Dietary patterns and eating behaviours established during childhood and adolescence are likely to persist into adulthood( 4 ). Thus, promoting healthy eating as early as possible is of particular importance. Furthermore, achieving and maintaining normal body weight is vital for favourable health outcomes throughout the life course( 3 , 5 ). In more detail, childhood obesity is associated with a wide array of adverse health outcomes, both physical and psychosocial( 6 ). Not only is excess weight in childhood and adolescence associated with dental caries and asthma( 7 , 8 ), but is also likely to lead to lifelong overweight and obesity( 9 ). Furthermore, childhood obesity is associated with greater risk and earlier onset of chronic disorders such as hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and type 2 diabetes( 3 , 9 – 11 ).

Be that as it may, the dietary patterns of children and adolescents in Greece over the last decades are shifting away from the traditional Greek diet, towards an unhealthier direction( 12 – 16 ). At the same time, approximately 40 % of children and adolescents are either overweight or obese, exhibiting one of the highest prevalence rates of paediatric overweight and obesity in Europe( 16 – 18 ). Hence, the promotion of healthy dietary patterns, based on the principles of the traditional Greek diet, as well as prevention and control of childhood obesity, is of notable importance in this particular European region.

Dietary guidelines constitute an essential policy tool for facilitating optimal dietary patterns and healthy eating behaviours. An evidence-based approach was employed to develop the 2014 National Dietary Guidelines of Greece (NDGGr) for adults( 19 ), as well as for specific population groups, including (i) infants, children and adolescents( 20 ); (ii) women (including women during pregnancy, lactation and menopause)( 21 ); and (iii) adults aged 65 years or older( 22 ). We report here the methodology adopted for the development of the food-based National Dietary Guidelines of Greece for Infants, Children and Adolescents, as well as the innovative aspects adopted for promoting healthy eating. In the present work we focus on the guidelines for children and adolescents aged 1–18 years. It should be also noted that through the promotion of healthy dietary patterns and physical activity, the NDGGr aim to serve as a policy tool for preventing childhood obesity.

Materials and methods

The NDGGr( 19 – 22 ) were developed under the Operational Program ‘Human Resources Development’ 2007–2013 of the Hellenic Ministry of Health. The private non-profit scientific organization, the Institute of Preventive Medicine, Environmental and Occupational Health – Prolepsis, was selected to develop a methodological protocol for the optimal development and to compile the NDGGr. The WHO, FAO and European Food Safety Authority methodologies( 23 – 25 ) were used for the development of the food-based NDGGr, so as to take into consideration valuable experiences and relevant methodology for developing such guidelines. A multidisciplinary research team (including nutritionists, physicians, health promotion specialists and food technologists) was selected to implement the entailed research tasks, compilation and authorship of the NDGGr, as well as its production and dissemination following Scientific Committee approval. In more detail, the synthesis and critical appraisal of the most robust peer-reviewed epidemiological evidence was undertaken by the Prolepsis team, which was responsible for compiling the final NDGGr and related health promotion materials for the general and scientific publics.

Additionally, Prolepsis selected and appointed an independent multidisciplinary Scientific Committee, responsible for the critical review and appraisal of the compiled NDGGr. The Scientific Committee consisted of twenty-eight experts in the nutritional sciences, including physicians, research scientists and academics, as well as representatives of relevant Ministries. Financial compensation was not awarded for Committee participation. Committee members were assigned to four Subcommittees (i.e. NDGGr Subcommittees for: (i) Infants, Children and Adolescents (ages 0 to <18 years old); (ii) Adults; (iii) Women (including women during pregnancy, lactation and menopause); and (vi) Adults aged 65 years or older) based on their particular field of expertise. Subcommittee members were responsible for reviewing the critically appraised literature regarding the potential aetiological association between the consumption of nutrients, foods and/or dietary patterns and subsequent risk of developing the most prevalent diet-related chronic diseases (including CVD, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, obesity and most prevalent cancers) and for approving the final dietary guidelines, as will be discussed below. The Committee members met regularly with the Prolepsis team to discuss the critically appraised evidence until a consensus was reached.

Synthesis of evidence

First, for the development of the dietary guidelines, the following were taken into consideration: (i) the consumption of food items and/or food groups in Greece, particularly in relation to the traditional Greek diet, was assessed based on the FAO food balance sheets( 26 ), the Hellenic National Statistics Authority household budget surveys( 27 ) and food consumption surveys( 28 ); (ii) related scientific publications, including population-based epidemiological investigations regarding the consumption of food items and/or meals at the individual level in Greece; (iii) the regional seasonal availability, financial cost and related environmental considerations (i.e. including the bioeconomy and biodiversity of foods), when applicable; and (vi) the pre-existing Dietary Guidelines for Adults of the Supreme Scientific Health Council of the Hellenic Ministry of Health and Welfare( 29 ). In addition, a systematic literature search was conducted to identify the most recent and related scientific reports and dietary guidelines published by international organizations, governmental entities and scientific societies in Greece, Europe and worldwide( 30 – 33 ).

Second, the epidemiological trends and public health importance of nutrition-related chronic diseases in Greece were evaluated based on a systematic literature search in PubMED, as well as the WHO European Health for All databases and GLOBOCAN database. Additionally, a systematic search was conducted to retrieve the most robust epidemiological evidence (i.e. meta-analyses of randomized trials or prospective cohort studies) regarding the consumption of nutrients, foods and/or dietary patterns, as well as physical activity, with the subsequent risk of developing the aforementioned most prevalent diet-related chronic diseases.

Evidence-level grading and compilation of the National Dietary Guidelines of Greece

The retrieved evidence was graded based on the methodology of the European Society of Cardiology (Recommendations for Guidelines Production; https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Guidelines-development/Writing-ESC-Guidelines)( 34 ), modified to accommodate for the particularities of nutritional data( 35 ). In particular, the following three Levels of Evidence were applied: (i) Level A, evidence arising from ≥1 meta-analysis of either prospective cohort studies or randomized clinical trials and/or ≥1 multi-centre randomized clinical trial; (ii) Level B, evidence arising from ≥2 randomized clinical trials or ≥ 2 prospective cohort studies or ≥5 case–control studies or ≥5 non-randomized clinical trials; or (iii) Level C, expert consensus and/or evidence arising from cross-sectional and/or case–control studies. The preliminary dietary guidelines were compiled based on the evidence-level grading and presented for review to all Subcommittee members. A series of expert panel meetings among Subcommittee members was conducted for the refinement of dietary guidelines until a consensus was reached. Finally, an analytical Report was compiled detailing the retrieved findings and associated strength of recommendation for each NDGGr food item/category. This Report served as the basis for further developing two volumes of the NDGGr targeting (i) the general public and (ii) health professionals, as detailed below.

Development of the National Dietary Guidelines of Greece

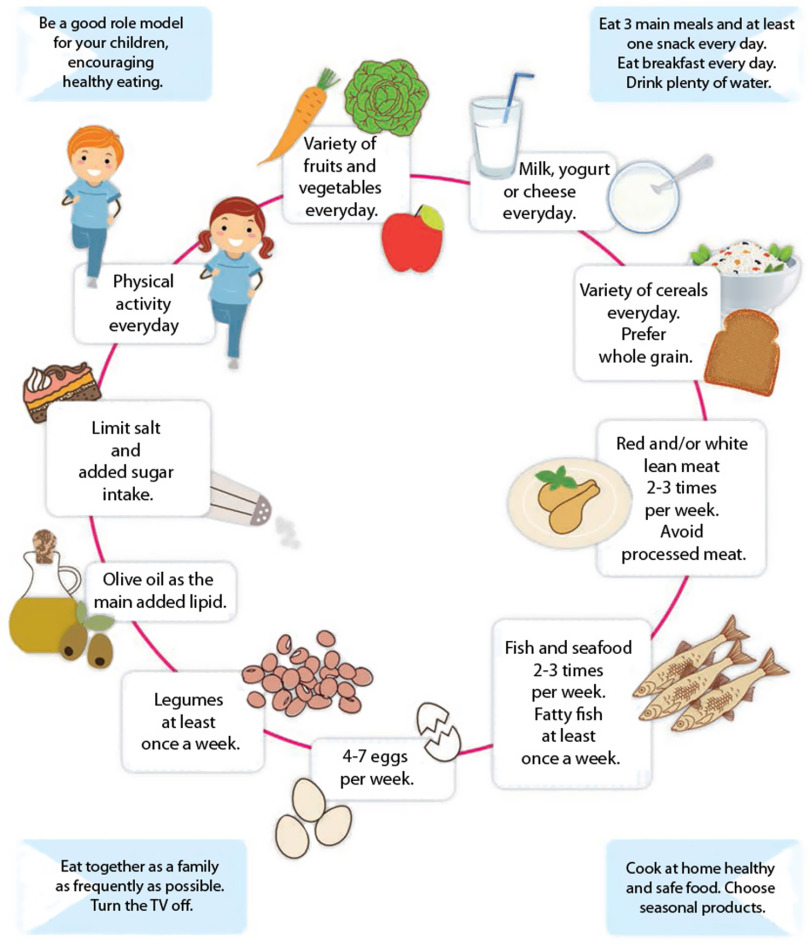

Food-based NDGGr, with nutritional education and health promotion messages for consumers, were subsequently developed, including the following food items/categories: (i) fruits; (ii) vegetables; (iii) milk and dairy products; (iv) cereals; (v) red and white meat; (vi) fish and seafood; (vii) eggs; (viii) legumes; (ix) added lipids, olives and nuts; (x) added sugars and salt; and (xi) water and beverages. Physical activity recommendations were also compiled. To facilitate uptake, a Nutrition Wheel consisting of the ten most vital nutrition and health promotion messages was developed (Fig. 1). Pictorial Healthy Meal recommendations were incorporated regarding the optimal frequency and serving sizes of main meals, based on the traditional Greek diet (Fig. 2). Specifically, the Healthy Meal depicts indicative serving sizes for adults and combinations of foods based on the traditional Greek diet (including a traditional main dish, salad and fruit) and prepared according to the NDGGr recommendations.

Fig. 1.

The 2014 Greek Dietary Guidelines for Infants, Children and Adolescents. The 2014 Greek Dietary Guidelines are depicted as a Nutrition Wheel entitled ‘Ten steps to healthy eating for children and adolescents’

Fig. 2.

Indicative examples of the Healthy Meals included in the Greek National Dietary Guidelines for Infants, Children and Adolescents

Finally, two volumes of the NDGGr were developed targeting (i) the general public and (ii) health professionals, respectively. Regarding the NDGGr for the general public, dietary recommendations were presented analytically in text and pictorial formats, as detailed above. With respect to the NDGGr for the health professionals, a detailed description of the evidence reviewed and strength of recommendations was compiled. To enhance uptake, the NDGGr were disseminated in print format and additionally made freely accessible in electronic format.

Results

The NDGGr for infants, children and adolescents primarily include food-based guidelines, as well as recommendations regarding the frequency of meals and parenting tips for promoting healthy dietary patterns and eating behaviours. Specifically, the NDGGr for children and adolescents (aged 1 to <18 years old) encompass age-specific recommendations regarding ten food groups and/or items, water and/or beverages, and physical activity. Age-specific recommended dietary intakes, as well as indicative serving/portion sizes, are summarized below and detailed in Table 1. In conjunction, a Nutrition Wheel, consisting of the ten most pivotal recommendations, was developed (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Recommendations and indicative serving sizes* for the consumption of food items and food groups based on the 2014 Greek Dietary Guidelines for children and adolescents

| Age | 12 to <24 months | 2 to 3 years | 4 to 8 years | 9 to 13 years | 14 to <18 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits† | 1 serving/d | 1 serving/d | 1–2 servings/d | 2–3 servings/d | 3 servings/d |

| Vegetables‡ | 1 serving/d | 1 serving/d | 1–2 servings/d | 2–3 servings/d | 3–4 servings/d |

| Milk and dairy products§ | 2 servings/d | 2 servings/d | 2–3 servings/d | 3–4 servings/d | 3–4 servings/d |

| Cereals║ | 2 servings/d | 3 servings/d | 4–5 servings/d | 5–6 servings/d | 6–8 servings/d |

| Red and white meat | 3–4 servings/week (serving size: 40–60 g) | 2–3 servings/week (serving size: 60g) | 2–3 servings/week (serving size: 60–90 g) | 2–3 servings/week (serving size: 90–120 g) | 2–3 servings/week (serving size: 120–150 g) |

| Fish and seafood | 2 servings/week (serving size: 60 g) | 2 servings/week (serving size: 60–90 g) | 2–3 servings/week (serving size: 90–120 g) | 2–3 servings/week (serving size: 120–150 g) | 2–3 servings/week (serving size: 150 g) |

| Eggs | 4–7 eggs/week | 4–7 eggs/week | 4–7 eggs/week | 4–7 eggs/week | 4–7 eggs/week |

| Legumes | 1–2 servings/week (serving size: 40–60 g) | ≤3 servings/week (serving size: 60–90 g) | 3 servings/week (serving size: 90–120 g) | >3 servings/week (serving size: 120–150 g) | >3 servings/week (serving size: 150–200 g) |

| Added lipids, olives and nuts¶ | 1 serving/d | 1–2 servings/d | 2–3 servings/d | 3–4 servings/d | 4–5 servings/d |

| Added sugars** and salt†† | Limit intake | Limit intake | Limit intake | Limit intake | Limit intake |

| Fluids | 5 glasses/d | 5 glasses/d | 6–7 glasses/d | 8–10 glasses/d | 10–12 glasses/d |

| Of them Water | 3–4 glasses/d | 3–4 glasses/d | 4–5 glasses/d | 6–8 glasses/d | 8–10 glasses/d |

The nutritional needs of children and adolescents may differ according to sex, physical activity level and stage of development.

1 serving corresponds to 120–200 g fruit or 125 ml fresh fruit juice without added sugars.

1 serving corresponds to 150–200 g raw or cooked vegetables.

1 serving corresponds to 150 ml milk or 200 g yoghurt or 30 g hard cheese or 60 g soft cheese.

1 serving corresponds to 1 slice bread, or 120 ml cooked rice or pasta, or 120–150 g cooked potatoes.

1 serving corresponds to 15 ml olive oil or vegetable oil, 15 ml margarine or butter, or 10–12 olives.

Avoid consumption of sweetened beverages, soft drinks and fruit juices with added sugars.

For table salt, it is recommended that infants aged 1–3 years old consume <2 g/d, children aged 4–6 years old consume <3 g/d, and children and adolescents aged 7–18 years old consume <5 g/d.

Vegetables and fruits

The category ‘Vegetables and Fruits’ encompasses all raw and cooked vegetables (including starchy vegetables, such as peas, corn and pumpkins), as well as raw and dried fruits and freshly squeezed fruit juices (i.e. without added sugars). Potatoes are not included in this category. Frequent consumption of vegetables and fruits is associated with a reduced risk of CVD, type 2 diabetes and gastrointestinal cancers in adulthood( 36 – 41 ). Additional health benefits of such consumption patterns include the prevention of overweight and obesity in both childhood and adulthood( 34 ). Hence, the NDGGr recommendation entails the consumption of a variety of fruits and vegetables (preferentially those in season) several times per day in every main meal (Fig. 2).

Milk and dairy products

This category includes milk and dairy products, including yoghurt and cheese. Butter is excluded as it pertains to an added source of oils and fats. Moderate consumption of milk and dairy products is associated with a reduced risk of CVD, type 2 diabetes and colorectal cancer in adulthood( 42 – 45 ). Additional health benefits include increased bone density and a reduced likelihood of hypertension( 46 ). Thus, the NDGGr recommendation endorses that children and adolescents consume milk and dairy products daily. Additionally, children >2 years old may consume either full-fat or semi-skimmed milk.

Cereals

Rice, potatoes, cereals and grains, as well as their by-products (e.g. flour, bread and rusks, pasta and traditional savoury pies), are included in this food category. Wholegrain cereals and their by-products are a rich source of carbohydrates, as well as dietary fibre, B-complex vitamins and minerals. Increased consumption of whole grains is associated with a reduced risk of CVD, type 2 diabetes and colorectal cancer, as well as a reduced likelihood of overweight and/or obesity( 36 , 47 – 49 ). The NDGGr recommend that children and adolescents consume a variety of grains and cereals (preferably wholegrain) daily.

Red meat and white meat

This category encompasses all red (e.g. beef, pork, lamb, goat, deer and wild boar) and white (e.g. chicken, turkey, duck, rabbit, pheasant and game birds) meats, as well as their related processed products. While meats are a rich source of proteins, Fe, vitamins B and E, Mg and Zn, increased consumption of processed meats is associated with several adverse health outcomes( 50 – 53 ). Hence, the NDGGr advise that children older than 2 years should consume red and/or white meats 2–3 times per week. However, all processed meats should be avoided at all ages.

Fish and seafood

All types of fish and seafood, including shellfish, are included in this food category. Fish and seafood are a primary source of high-biological-value proteins (while concomitantly a poor source of saturated fats) and a rich source of vitamin D, Se and Zn. The elevated consumption of oily fish rich in n-3 fatty acids is essential for optimal brain development and related health outcomes in adulthood( 36 , 54 – 59 ). Thus, the NDGGr recommendation endorses children and adolescents to consume a variety of fish and seafood, corresponding to 2–3 servings per week. Additionally, at least one serving per week ought to regard the consumption of oily fish rich in n-3 fatty acids.

Eggs

Eggs are a readily available protein source with high biological value. Due to their high nutrient content (e.g. vitamins A, D and B12, thiamin and riboflavin, as well as carotenoids, Se and choline), and taking into consideration the associations of egg consumption with various health outcomes( 36 , 60 – 62 ), children of all ages should consume 4–7 eggs per week. It is of note that children with hyperlipidaemia are advised to first consult with their physician.

Legumes

The ‘Legumes’ category, an integral component of the traditional Greek diet, includes lentils, beans, chickpeas, split peas and broad beans. Pulses and legumes constitute a rich source of proteins and fibre, as well as several vitamins and minerals, including Fe, Ca, Mg and Zn, with favourable health outcomes( 48 , 63 , 64 ). Hence, the NDGGr recommend that children and adolescents should consume pulses and legumes at least once per week.

Added lipids, olives and nuts

This category includes added fats and oils (e.g. olive oil, seed and/or other vegetable oils, margarine and butter), olives and nuts, as well as their by-products (e.g. tahini). The consumption of added fats and oils is essential for normal child development. In particular, olive oil is a vital component of the traditional Greek diet, being concomitantly a rich source of MUFA, vitamin E and polyphenols. In contrast, the consumption of saturated and trans-fatty acids is associated with hyperlipidaemia, CVD, as well as overweight/obesity( 32 , 36 , 66 – 69 ). Thus, the NDGGr recommend that olive oil ought to be the preferred choice of added oil in the preparation of cooked meals and/or salads. Furthermore, the consumption of added fats arising from animal sources (e.g. butter) should be limited and/or substituted with olive oil. Finally, the consumption of trans-fatty acids (e.g. in prepared food products, sweets and/or fast-food items) should be avoided.

Added sugars and salt

The ‘Added Sugars and Salt’ category encompasses all added sugars (e.g. granulated white and brown sugar, cane sugar, glucose powder and fructose powder) and honey, as well as table salt. Consumption of added sugars, including sweetened beverages and soft drinks, is associated with an increased risk of dental caries and childhood overweight/obesity( 70 – 72 ). Hence, the NDGGr recommend that the consumption of foods with added sugars should be limited to a minimum. In particular, it is recommended that the consumption of sweetened beverages, soft drinks and fruit juices with added sugars is avoided. In addition, table salt, as most often made available in the Greek market, is an essential source of iodine. However, consumption of elevated levels during childhood and adolescence is associated with an increased risk of hypertension and CVD in adulthood( 73 – 76 ). As a result, the dietary guideline developed was that consumption of salt should be limited in children and adolescents.

Physical activity

Physical activity is associated with a wide array of health benefits in childhood and adolescence, including optimal physical and psychosocial development, normal body weight and the prevention of several chronic diseases in adulthood, including hypercholesterolaemia and type 2 diabetes( 77 , 78 ). With respect to young children (aged 3–6 years old), the NDGGr recommend that total screen time should be limited to a minimum and children should be physically active, in a wide range of activities, for at least 1 h/d. Within this context, parental participation is also recommended. Regarding older children and adolescents (aged 7–18 years old), it is also recommended that total screen time is limited and at least 1 h/d is dedicated to either athletic and/or sports training activities. However, it is recommended that children aged younger than 10 years old should focus mainly on safe and fun activities rather than competitive sports.

Other recommendations

The NDGGr include several additional recommendations regarding the types and frequencies of meals. Particular emphasis is placed on the importance of consuming a healthy breakfast, including items from at least three food groups (i.e. dairy products, cereals, and fruits or vegetables). Additionally, for main meals, illustrations of a Healthy Meal (including a main dish, salad and fruit) based on the traditional Greek diet are illustrated for clarity. Furthermore, behavioural techniques are included as a separate chapter of the NDGGr, aiming to provide practical tips to parents for the promotion of healthy eating. The issues addressed include the influence of parental behaviours (e.g. acting as role models) for encouraging healthy dietary patterns( 79 , 80 ), the importance of consuming family meals( 81 , 82 ), tips and ideas for improving the consumption of less preferred foods, as well as specific tips for adolescents. The aforementioned recommendations are summarized in the Nutrition Wheel Guidelines as follows: ‘Be a role model for your children by encouraging healthy eating. Eat 3 main meals and at least one snack every day. Eat breakfast every day. Drink plenty of water. Eat together as a family as frequently as possible. Turn the TV off. Cook at home healthy and safe food. Choose seasonal products.’

Discussion

We report the methodological approach adopted for the development of the 2014 NDGGr for infants, children and adolescents. Within this context, an evidence-based approach was employed to develop recommendations for promoting healthy dietary patterns and physical activity, as well as a Nutrition Wheel, to ultimately enhance the adoption of the aforementioned recommendations and promote healthy eating habits. The NDGGr have been adopted by the Hellenic Ministry of Education, while the Hellenic Institute for Educational Policies has approved their use and widespread dissemination in public schools nationwide. Additionally, the Ministry of Health, as well as the Hellenic Central Health Council, has endorsed their use as a tool for promoting healthy dietary patterns through their widespread dissemination to the general public (including students, parents and educators), as well as health-care professionals. To enhance extensive uptake, the NDGGr have been disseminated nationwide and are electronically freely accessible (English summary available at http://www.diatrofikoiodigoi.gr/?Page=summary−children). Finally, scientific volumes of the NDGGr, including a detailed description of the evidence reviewed and strength of recommendation in both print and electronic forms, have been made accessible to nutritionists and health-care professionals alike.

Food-based dietary guidelines for children and/or adolescents have been previously published by twenty-nine (including Greece) out of fifty-one countries in the WHO European Region (57 %). Of the other twenty-eight countries (presented in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S1)( 83 – 115 ), twenty-four adopt a pictorial illustration for the presentation of the guidelines; twelve adopt the pyramid; ten use other forms of pictorial models (mostly circles, plates or pies); and two countries (Finland( 83 ) and Slovenia( 84 )) use both the food pyramid and plate. The NDGGr also use two types of illustration: a Nutrition Wheel and pictorial Healthy Meal recommendations (Figs 1 and 2). Furthermore, the NDGGr are one of the few guidelines which encompass the greatest number of distinct food categories, including ten food groups, as well as physical activity (other dietary guidelines with eight or nine distinct food categories are those of Belgium( 85 ), Finland( 83 ), Luxembourg( 86 ), Netherlands( 87 ) and Slovenia( 84 )).

It should be also noted that despite different geographical, socio-economic and cultural contexts among countries, the majority of the pivotal nutritional recommendations are similar. In fact, the principal messages include daily consumption of adequate amounts of fruits, vegetables, dairy products, as well as starches, cereals and grains, and moderate-to-limited intake of fats. In more detail, guidelines from all countries include recommendations regarding fruit and vegetable intake, most of which suggest the intake of five servings daily or at least 500 g/d. The NDGGr are one of the guidelines recommending the highest suggested intake of fruits and vegetables, as the lowest suggested intake (for children 1–3 years) is >300 g/d, reaching for adolescents more than 1000 g/d. Furthermore, nineteen of the twenty-eight countries (68 %) incorporate specific recommendations regarding the increased consumption of whole grains or provide the recommended dietary fibre intake. The NDGGr also promote the intake of wholegrain cereals with specific tips facilitating their consumption. Furthermore, it should be noted that even if the recommended intake of protein food and red meat is more or less common in the majority of the countries, it is noteworthy that only eleven of the twenty-eight guidelines (39 %) explicitly recommend the avoidance of processed meat. Finally, it should be mentioned that the majority of the WHO European Region countries (twenty-two out of twenty-eight) provide physical activity recommendations. Of these countries, only eleven recommend physical activity for 60 min/d (or longer) – the highest recommendation, similarly to the NDGGr.

All things considered, the recently developed NDGGr for infants, children and adolescents have employed an evidence-based approach to develop food-based nutritional and physical activity recommendations. The NDGGr novel aspects lie in the evidence-based approach applied, as well as the development of an age-specific Nutrition Wheel and indicative examples of Healthy Meals with pictorial depictions providing recommendations regarding the optimal frequency and serving sizes of main meals, based on the traditional Greek diet. Future longitudinal investigations are necessary to elucidate whether the application of the NDGGr is effective for promoting healthy dietary patterns and serves as a useful tool for childhood obesity prevention and maintenance of an optimal body weight throughout adolescence and subsequent adulthood.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Enav Horwitz for her valuable contribution for the preparation of Supplemental Table S1. The authors would like to express their gratitude to all members of the National Dietary Guidelines Scientific Committee for generous contribution of their time and valuable knowledge: Ioannis Alamanos4 (Former Associate Professor, Patras Medical School); Maria Alevizaki1 (Professor of Endocrinology, Athens Medical School); Aristides Antsaklis3 (Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Athens Medical School); Vassiliki Benetou1,2,3,4 (Paediatrician, Associate Professor of Hygiene and Epidemiology, Athens Medical School); Maria Chasapidou2 (Professor of Nutrition – Dietetics, Alexander Technological Educational Institute of Thessaloniki); George P. Chrousos2 (Professor of Paediatrics, Athens Medical School); Aikaterini Dakou-Voutetaki2 (Professor Emeritus of Paediatric Endocrinology, Athens Medical School); George Dedoussis4 (Professor of Human Cellular and Molecular Biology, Harokopio University); Evanthia Diamanti-Kandarakis1 (Professor of Internal Medicine – Endocrinology, Athens Medical School); Stella Egglezou3 (Paediatrician–Neonatologist, Director of the Neonatal Department of the ‘Elena Venizelou’ Hospital, Athens); Eustathia Fouseki1,2,3,4 (Director of Directorate of Counselling, Career Guidance and Educational Activities of the Ministry of Culture, Education and Religious Affairs); Ioannis Karaitianos4 (Unr. Associate Professor of Surgery, Athens Medical School; Director of the ‘Agios Savvas’ Cancer Hospital; Chairman of the Board of Directors, Hellenic Association of Gerontology & Geriatrics); Eugenio Koumantakis3 (Professor Emeritus of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Crete); Dimitrios Linos1,2,3,4 (Professor of Surgery, Athens Medical School); Evangelia Magklara-Katsilabrou4 (Clinical Nutritionist – Dietitian); Ioannis Manios1,2 (Associate Professor in Nutrition Education – Assessment, Harokopio University); Anastasios Mortoglou1 (Internist – Endocrinologist, Head of Endocrinology Department, Athens Medical Center); Demosthenes Panagiotakos1 (Professor in Biostatistics – Epidemiology of Nutrition, Harokopio University); Permanthia Panani3 (Midwife, President of SEMMA, ICM (International Confederation of Midwives) representative, European Midwives Association representative); Anastasia Pantazopoulou-Foteinea1,2,3,4 (Public Health Physician – Occupational Physician, former General Principal of Public Health, Ministry of Health); Evangelos Polychronopoulos3,4 (Associate Professor in Preventive Medicine & Nutrition, Harokopio University); Theodora Psaltopoulou1,4 (Internist, Associate Professor of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Athens Medical School); Eleftheria Roma-Giannikou2 (Professor Emeritus of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Athens Medical School); Panagiota Sourtzi4 (Professor, Faculty of Nursing, University of Athens; Secretary, Board of Directors, Hellenic Association of Gerontology & Geriatrics); Chrysa Tzoumaka-Mpakoula2,3 (Professor Emeritus of Pediatrics, Athens Medical School); Antonis Zampelas1,3 (Professor of Human Nutrition, Agricultural University of Athens). 1Committee of the National Dietary Guidelines for Adults. 2Committee of the National Dietary Guidelines for Infants, Children and Adolescents. 3Committee of the National Dietary Guidelines for Women (including women during pregnancy, lactation and menopause). 4Committee of the National Dietary Guidelines for Adults aged 65 years or older. The National Dietary Guidelines of Greece Scientific Implementation Team (http://www.diatrofikoiodigoi.gr/?Page=summary-who-we-are): Scientific Coordinator: Athena Linos, MD, MPH, PhD (Professor & Chair of Department of Hygiene, Epidemiology & Medical Statistics, Athens Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens). Team of Authors: Vassiliki Benetou, MD, PhD (Scientific consultant) (Paediatrician, Assistant Professor of Hygiene and Epidemiology, University of Athens Medical School); Dina (Konstantina) Zota, MSc (Project manager) (Health Promotion Specialist, Prolepsis Institute); Katerina Belogianni, MSc (Clinical Nutritionist – Dietitian, Prolepsis Institute); Anna Kandaraki, MSc (Clinical Psychologist); Christina-Maria Kastorini, PhD (Clinical Nutritionist – Dietitian, Prolepsis Institute); Rena Kosti, MSc, PGCert, PhD (Food Scientist – Dietitian); Eleni Papadimitriou, MD, PhD (Physician, Prolepsis Institute); Fani Pechlivani, MSc, PhD (Midwife, Assistant Professor, Midwifery Department, Technological Educational Institute of Athens); Anastasia Samara, PhD (Clinical Nutritionist – Dietitian); Ioannis Spyridis, PhD (Health Promotion Specialist, Prolepsis Institute); Panagiota Karnaki, MSc (Health Promotion Specialist, Prolepsis Institute); Afroditi Veloudaki, MA (Health Communications Specialist, Prolepsis Institute). Financial support: The development of the 2014 National Dietary Guidelines of Greece was funded by the NSRF 2007–2013 Program (MIS code 346818, as part of the Operational Program ‘Human Resources Development’), the Hellenic Ministry of Occupation, Social Insurance and Welfare, and the Hellenic Ministry of Health. The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: All authors report no conflict of interest. Authorship: A.L.C. and M.K.N. contributed equally to this work. E.C., A.L.C. and M.K.N. drafted the first version of the manuscript; C.M.K. and D.Z. drafted the revised version of the manuscript; D.Z., C.M.K., E.P., K.B., V.B. and A.L. are part of the scientific team of the national dietary guidelines. All authors contributed to the revising of the manuscript for important content and gave their final approval of the version submitted for publication. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019001034.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Jacka FN, Kremer PJ, Berk M et al. (2011) A prospective study of diet quality and mental health in adolescents. PLoS One 6, e24805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shepherd J, Harden A, Rees R et al. (2006) Young people and healthy eating: a systematic review of research on barriers and facilitators. Health Educ Res 21, 239–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Park MH, Falconer C, Viner RM et al. (2012) The impact of childhood obesity on morbidity and mortality in adulthood: a systematic review. Obes Rev 13, 985–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scaglioni S, De Cosmi V, Ciappolino V et al. (2018) Factors influencing children’s eating behaviours. Nutrients 10, E706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lloyd LJ, Langley-Evans SC & McMullen S (2010) Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 34, 18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Quek YH, Tam WW, Zhang MW et al. (2017) Exploring the association between childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 18, 742–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hayden C, Bowler JO, Chambers S et al. (2013) Obesity and dental caries in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 41, 289–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tashiro H & Shore SA (2018) Obesity and severe asthma. Allergol Int. Published online: 20 November 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW et al. (2008) Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 9, 474–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Friedemann C, Heneghan C, Mahtani K et al. (2012) Cardiovascular disease risk in healthy children and its association with body mass index: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 345, e4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abdullah A, Wolfe R & Stoelwinder JU (2011) The number of years lived with obesity and the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Int J Epidemiol 40, 985–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tambalis KD, Panagiotakos DB, Moraiti I et al. ; EYZHN Study Group (2018) Poor dietary habits in Greek schoolchildren are strongly associated with screen time: results from the EYZHN (National Action for Children’s Health) Program. Eur J Clin Nutr 72, 572–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kastorini CM, Lykou A, Yannakoulia M et al. ; DIATROFI Program Research Team (2016) The influence of a school-based intervention programme regarding adherence to a healthy diet in children and adolescents from disadvantaged areas in Greece: the DIATROFI study. J Epidemiol Community Health 70, 671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Manios Y, Kourlaba G, Kondaki K et al. (2009) Diet quality of preschoolers in Greece based on the Healthy Eating Index: the GENESIS study. J Am Diet Assoc 109, 616–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kontogianni MD, Vidra N, Farmaki AE et al. (2008) Adherence rates to the Mediterranean diet are low in a representative sample of Greek children and adolescents. J Nutr 138, 1951–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farajian P, Risvas G, Karasouli K et al. (2011) Very high childhood obesity prevalence and low adherence rates to the Mediterranean diet in Greek children: the GRECO study. Atherosclerosis 217, 525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tambalis KD, Panagiotakos DB, Kavouras SA et al. (2010) Eleven-year prevalence trends of obesity in Greek children: first evidence that prevalence of obesity is leveling off. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18, 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2014) Obesity update. http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Obesity-Update-2014.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 19. Eu Dia … Trofin (2014) Greek National Dietary Guidelines for Adults. http://diatrofikoiodigoi.gr/?page=summary-adults (accessed June 2017).

- 20. Eu Dia … Trofin (2014) Greek National Dietary Guidelines for Infants, Children and Adolescents. http://diatrofikoiodigoi.gr/?Page=summary-children (accessed June 2017).

- 21. Eu Dia … Trofin (2014) Greek National Dietary Guidelines for Women, including Women in Pregnancy, Lactation & Menopause. http://diatrofikoiodigoi.gr/?page=summary-women (accessed June 2017).

- 22. Eu Dia … Trofin (2014) Greek National Dietary Guidelines for Adults aged 65 Years or Older. http://diatrofikoiodigoi.gr/?Page=summary-elderly (accessed June 2017).

- 23. European Food Safety Authority Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies (2010) Scientific Opinion on establishing food-based dietary guidelines. EFSA J 8, 1460. [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization (2004) Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Resolution WHA 55.23. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization (WHO) (1998) Preparation and Use of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Consultation. Geneva: WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2013) FAOSTAT. http://faostat.fao.org/site/291/default.aspx.%202013 (accessed July 2013).

- 27. WHO Collaborating Center for Food and Nutrition Policies & Department of Hygiene, Epidemiology, and Medical Statistics, University of Athens (2013) Data Food Networking Project (DAFNE). http://www.nut.uoa.gr/dafnesoftweb (accessed July 2013).

- 28. De Henauw S, Brants HA, Becker W et al. (2002) Operationalization of food consumption surveys in Europe: recommendations from the European Food Consumption Survey Methods (EFCOSUM) Project. Eur J Clin Nutr 56, Suppl. 2, S75–S88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hellenic Ministry of Health and Welfare (1999) Dietary guidelines for adults in Greece. Arch Hell Med 16, 516–524. [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization (2003) Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation WHO Technical Report Series no. 916. Geneva: WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Cancer Research Fund & American Institute for Cancer Research (2007) Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: AICR. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2010) Fats and Fatty Acids in Human Nutrition: Report of an Expert Consultation. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper no. 91. Rome: FAO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Health and Medical Research Council (2011) A Review of the Evidence to Address Targeted Questions to Inform the Revision of the Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H et al. (2012) European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 33, 1635–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mann JI (2010) Evidence-based nutrition: does it differ from evidence-based medicine? Ann Med 42, 475–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS et al. (2009) A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 169, 659–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cooper AJ, Forouhi NG, Ye Z et al. (2012) Fruit and vegetable intake and type 2 diabetes: EPIC-InterAct prospective study and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 66, 1082–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dauchet L, Amouyel P & Dallongeville J (2005) Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Neurology 65, 1193–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. He FJ, Nowson CA, Lucas M et al. (2007) Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables is related to a reduced risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Hum Hypertens 21, 717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carter P, Gray LJ, Troughton J et al. (2010) Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 341, c4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aune D, Lau R, Chan DS et al. (2011) Nonlinear reduction in risk for colorectal cancer by fruit and vegetable intake based on meta-analysis of prospective studies. Gastroenterology 141, 106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Soedamah-Muthu SS, Ding EL, Al-Delaimy WK et al. (2011) Milk and dairy consumption and incidence of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 93, 158–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aune D, Lau R, Chan DS et al. (2012) Dairy products and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ann Oncol 23, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huncharek M, Muscat J & Kupelnick B (2009) Colorectal cancer risk and dietary intake of calcium, vitamin D, and dairy products: a meta-analysis of 26,335 cases from 60 observational studies. Nutr Cancer 61, 47–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Elwood PC, Pickering JE, Givens DI et al. (2010) The consumption of milk and dairy foods and the incidence of vascular disease and diabetes: an overview of the evidence. Lipids 45, 925–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ralston RA, Lee JH, Truby H et al. (2012) A systematic review and meta-analysis of elevated blood pressure and consumption of dairy foods. J Hum Hypertens 26, 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ye EQ, Chacko SA, Chou EL et al. (2012) Greater whole-grain intake is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and weight gain. J Nutr 142, 1304–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aune D, Chan DS, Lau R et al. (2011) Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 343, d6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hauner H, Bechthold A, Boeing H et al. (2012) Evidence-based guideline of the German Nutrition Society: carbohydrate intake and prevention of nutrition-related diseases. Ann Nutr Metab 60, Suppl. 1, 1–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen GC, Lv DB, Pang Z et al. (2013) Red and processed meat consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr 67, 91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kaluza J, Wolk A & Larsson SC (2012) Red meat consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Stroke 43, 2556–2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Feskens EJ, Sluik D & van Woudenbergh GJ (2013) Meat consumption, diabetes, and its complications. Curr Diabetes Rep 13, 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aune D, Chan DS, Vieira AR et al. (2013) Red and processed meat intake and risk of colorectal adenomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cancer Causes Control 24, 611–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Innis SM (2009) Omega-3 fatty acids and neural development to 2 years of age: do we know enough for dietary recommendations? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 48, Suppl. 1, S16–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McCann JC & Ames BN (2005) Is docosahexaenoic acid, an n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid, required for development of normal brain function? An overview of evidence from cognitive and behavioral tests in humans and animals. Am J Clin Nutr 82, 281–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zheng J, Huang T, Yu Y et al. (2012) Fish consumption and CHD mortality: an updated meta-analysis of seventeen cohort studies. Public Health Nutr 15, 725–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chowdhury R, Stevens S, Gorman D et al. (2012) Association between fish consumption, long chain omega 3 fatty acids, and risk of cerebrovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 345, e6698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Larsson SC & Orsini N (2011) Fish consumption and the risk of stroke: a dose–response meta-analysis. Stroke 42, 3621–3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Xun P, Qin B, Song Y et al. (2012) Fish consumption and risk of stroke and its subtypes: accumulative evidence from a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr 66, 1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Li Y, Zhou C, Zhou X et al. (2013) Egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 229, 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rong Y, Chen L, Zhu T et al. (2013) Egg consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 346, e8539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shin JY, Xun P, Nakamura Y et al. (2013) Egg consumption in relation to risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 98, 146–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bernstein AM, Pan A, Rexrode KM et al. (2012) Dietary protein sources and the risk of stroke in men and women. Stroke 43, 637–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bazzano LA, Thompson AM, Tees MT et al. (2011) Non-soy legume consumption lowers cholesterol levels: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 21, 94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jakobsen MU, O’Reilly EJ, Heitmann BL et al. (2009) Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 89, 1425–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mozaffarian D, Micha R & Wallace S (2010) Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med 7, e1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bendsen NT, Christensen R, Bartels EM et al. (2011) Consumption of industrial and ruminant trans fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr 65, 773–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. European Food Safety Authority Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies (2010) Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol. EFSA J 8, 1461. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Psaltopoulou T, Kosti RI, Haidopoulos D et al. (2011) Olive oil intake is inversely related to cancer prevalence: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of 13,800 patients and 23,340 controls in 19 observational studies. Lipids Health Dis 10, 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Anderson CA, Curzon ME, Van Loveren C et al. (2009) Sucrose and dental caries: a review of the evidence. Obes Rev 10, Suppl. 1, 41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Te Morenga L, Mallard S & Mann J (2012) Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ 346, e7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB & Brownell KD (2007) Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 97, 667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L et al. (2013) Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 346, f1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB et al. (2009) Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 339, b4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Li XY, Cai XL, Bian PD et al. (2012) High salt intake and stroke: meta-analysis of the epidemiologic evidence. CNS Neurosci Ther 18, 691–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. D’Elia L, Rossi G, Ippolito R et al. (2012) Habitual salt intake and risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin Nutr 31, 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Goran MI & Treuth MS (2001) Energy expenditure, physical activity, and obesity in children. Pediatr Clin North Am 48, 931–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Must A & Tybor DJ (2005) Physical activity and sedentary behavior: a review of longitudinal studies of weight and adiposity in youth. Int J Obes (Lond) 29, Suppl. 2, S84–S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Schwartz C, Scholtens PA, Lalanne A et al. (2011) Development of healthy eating habits early in life. Review of recent evidence and selected guidelines. Appetite 57, 796–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Krolner R, Rasmussen M, Brug J et al. (2011) Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Part II: qualitative studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8, 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hammons AJ & Fiese BH (2011) Is frequency of shared family meals related to the nutritional health of children and adolescents? Pediatrics 127, e1565–e1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Scaglioni S, Arrizza C, Vecchi F et al. (2011) Determinants of children’s eating behavior. Am J Clin Nutr 94, 6 Suppl., 2006S–2011S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Finnish National Nutrition Council (2014) Finnish nutrition recommendations. http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/finland/en (accessed June 2017).

- 84. CINDI-Slovenia (2011) Zdrav Kroznik. http://www.fao.org/3/a-az910o.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 85. Belgian Federal Public Service of Public Health (2005) Practical Guidelines for Healthy Eating. http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/belgium/en/ (accessed June 2017).

- 86. Alkerwi A, Sauvageot N, Nau A et al. (2012) Population compliance with national dietary recommendations and its determinants: findings from the ORISCAV-LUX study. Br J Nutr 108, 2083–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kromhout D, Spaaij CJ, de Goede J et al. (2016) The 2015 Dutch food-based dietary guidelines. Eur J Clin Nutr 70, 869–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Albanian Ministry of Health Department of Public Health (2008) Recommendations on Healthy Nutrition in Albania. http://www.fao.org/3/a-as658e.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 89. Austrian Ministry of Health (2010) Die österreichische Ernährungspyramide. http://www.bmgf.gv.at/cms/home/attachments/7/3/0/CH1046/CMS1290513144661/folder_erpyr_web.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 90. Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina Institute of Public Health (2004) Vodic o ishrani za odraslu populaciju. http://www.fao.org/3/a-as669o.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 91. Bulgarian Ministry of Health National Center of Public Health Protection (2006) Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Adults in Bulgaria. http://ncpha.government.bg/files/hranene-en.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 92. Croatian Ministry of Health (2012) Croatian Dietary Guidelines. http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/croatia/en/ (accessed June 2017).

- 93. Cypriot Ministry of Health (2007) Cypriot National Guidelines for Diet and Physical Activity in Children Aged 6–12 Years Old. http://www.fao.org/3/a-as674o.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 94. Danish Ministry of Food Agriculture and Fisheries (2013) Die officiele Kostrad. http://www.fao.org/3/a-as675o.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 95. Estonian Society of Nutritional Sciences (2009) Laste ja Noorte Toidusoovitused. http://www.fao.org/3/a-as678o.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 96. French National Nutrition and Health Programme (2011) La santé vient en mangeant et en bougeant: Le guide Parents 0–18 ans. http://www.mangerbouger.fr/PNNS/Guides-et-documents/Guides-nutrition (accessed June 2017).

- 97. German Nutrition Society (2013) 10 guidelines of the German Nutrition Society (DGE) for a wholesome diet. https://www.dge.de/index.php?id=322 (accessed June 2017).

- 98. Hungarian Ministry of Health (2004) Táplálkozási ajánlások a magyarországi felnőtt lakosság számára felnőtt lak. http://www.fao.org/3/a-as684o.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 99. Icelandic Directorate of Health (2014) Ráðleggingar um mataræði: Fyrir fullorðna og börn frá tveggja ára aldri. http://www.landlaeknir.is/servlet/file/store93/item25796/radleggingar-um-mataraedi-2015.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 100. Irish Department of Health (2015) Healthy Food for Life. http://www.healthyireland.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/M9481-Food-Pyramid-Leaflet.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 101. Israeli Ministry of Health Public Health Services (2008) Moving to a healthy lifestyle. http://www.fao.org/3/a-as685e.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 102. Italian National Research Institute on Diet and Nutrition (2003) Linee Guida per una Sana Alimentazione Italiana. http://www.fao.org/3/a-as686o.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 103. Latvian Ministry of Health (2008) Veselīga uztura ieteikumi zīdaiņu barošanai. http://www.fao.org/3/a-as689o.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 104. Maltese Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Directorate (2016) Dietary Guidelines for Maltese Adults. https://health.gov.mt/en/health-promotion/Documents/library/publications/Dietary%20Guidelines%20for%20Professionals%20final.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 105. Nordic Council of Ministers (2014) Anbefalinger om kosthold, ernæring og fysisk aktivite. https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/806/Anbefalinger-om-kosthold-ernering-og-fysisk-aktivitet-IS-2170.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 106. Polish National Food and Nutrition Institute (2010) Principles of healthy eating. http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/poland/en/ (accessed June 2017).

- 107. Portuguese Health Directorate (2003) Dia Alimentar. http://www.fao.org/3/a-ax434o.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 108. Romanian Ministry of Health & Romanian Nutrition Society (2006) Guidelines for a healthy diet. http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/romania/en/ (accessed June 2017).

- 109. Public Health Authority of the Slovak Republic (2014) 10 Rules of a Healthy Plate. http://www.uvzsr.sk/en/docs/info/Letak_Zdravy_tanier_EN.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 110. Spanish Ministry of Health and Social Services (2005) Eat healthy and move: 12 healthy decisions. http://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/educanaos/alimentacion_ninos.pdf (accessed June 2017).

- 111. Swedish National Food Agency (2015) Find your way to eat greener, not too much and to be active! http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/sweden/en/ (accessed June 2017).

- 112. Swiss Nutrition Society (2016) Nutrition disk for children. http://www.sge-ssn.ch/ich-und-du/essen-und-trinken/von-jung-bis-alt/jugend/ (accessed June 2017).

- 113. The FYROM Institute of Public Health (2014) The FYROM Dietary Guidelines. http://zdravstvo.gov.mk/vodich-za-ishrana/ (accessed June 2017).

- 114. Turkish Ministry of Health (2006) Dietary Guidelines for Turkey. http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/turkey/en (accessed June 2017).

- 115. Public Health England (2016) Eatwell Guide. http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/united-kingdom/en/ (accessed June 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019001034.

click here to view supplementary material