Abstract

Objective

The present study reviewed the literature on iodine status among women of childbearing age and pregnant women in the UK. Particular attention was given to study quality and methods used to assess iodine status.

Design

A systematic review was conducted to examine the literature and critically evaluate study design.

Setting

Studies were identified in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and Ovid MEDLINE databases, as well as from secondary references.

Participants

Women of childbearing age or pregnant, living in the UK.

Results

Fifty-seven articles were identified and twelve articles were selected, including a total of 5283 women. Nine studies conducted urinary iodine assessments, three studies conducted dietary assessments only, and seven studies classified their target population as iodine deficient according to WHO criteria.

Conclusions

No single study from the selected articles could produce nationally representative results regarding the prevalence of iodine deficiency among the female population in the UK. Consideration of the evidence as a whole suggests that women of childbearing age and pregnant women in the UK are generally iodine insufficient. Further large-scale research is required for more accurate and reliable evidence on iodine status in the UK.

Keywords: Iodine status, Iodine deficiency, Pregnant women, Childbearing age, UK, Systematic review

Iodine is an essential element for the production of the thyroid hormones triiodothyronine and thyroxine, which both play a crucial role in brain development and neurological function during fetal and postnatal growth( 1 ). Severe maternal iodine deficiency is often associated with iodine deficiency in the fetus, which can affect cognition in childhood and later life. The effects of mild maternal iodine deficiency on cognition in childhood are less well understood. Intervention studies have shown significantly higher IQ scores (approximately 10 points) in iodine-sufficient groups compared with iodine-deficient groups( 2 ).

In a 2007 report on iodine deficiency in Europe, WHO refers to a Recommended Nutrient Intake for iodine of 150 μg/d for adolescents and adults, rising to 250 μg/d for pregnant and lactating women( 3 ), which is required to support the 50 % increase in thyroid hormone production during the early stages of pregnancy( 1 ). Although the body is capable of utilizing thyroid iodine stores during a phase of iodine insufficiency, thyroid iodine stores may not meet the higher iodine demand during conception and pregnancy( 4 ). Considering the importance of iodine sufficiency in women of childbearing age, and the need to meet higher iodine requirements during pregnancy and lactation, women of childbearing age may be at particular risk of iodine deficiency.

The WHO’s first global estimate in 1980 suggested that 20–60 % of the world’s population had iodine deficiency and/or goitre, with most of the burden in developing countries( 1 ). Salt iodization programmes were introduced in some industrialized countries as early as the 1920s( 3 ) but relatively few such countries were recognized as being iodine replete before 1990( 5 ). In a report on global iodine deficiency published in 2008, the WHO listed the UK as one the countries with insufficient iodine data for the population( 6 ). Prior to this, a review was published by Phillips in 1997 suggesting that the iodination of dairy herds resulted in a trend of declining endemic goitre and a trend of increasing iodine status in the UK since 1960s( 7 ). Thus, iodine status in the UK population was overlooked for many years. Following the 2008 WHO statement, an epidemiological study in 2011 of iodine status in 737 schoolgirls suggested that iodine deficiency was prevalent in the UK population, drawing academic and public attention( 8 ).

Iodine status is assessed through dietary intake and urinary excretion. Dietary iodine intake is not considered an accurate means of assessing population iodine status due to the variability of iodine content in food( 9 ). Rather, iodine status is preferentially determined by biomarkers which include urinary iodine concentration (UIC), goitre rate, serum thyroid-stimulating hormone and serum thyroglobulin( 1 ). With regard to estimating iodine intake, the four commonly used markers are 24 h urine collections, spot urine collections, urinary iodine-to-creatinine ratio and estimated 24 h iodine excretion( 10 ). WHO recommends median UIC for the assessment of population iodine status. According to the UNICEF 2007 guide for programme managers( 11 ), a median UIC of 100–199 μg/l reflects adequate iodine intake among school-age children, a range that may also be applied to women of reproductive age( 11 ); a median UIC of 150–249 μg/l is considered to reflect adequate iodine intake among pregnant women. A more recent UNICEF report supports the widening of this range (100–299 μg/l) for school-age children but not for other groups( 12 ). It is also stated that median UIC should not be used to quantify the proportion of a population with iodine deficiency, given the considerable day-to-day variation in individual UIC, but WHO proposes that not more than 20 % of a population should have UIC <50 μg/l( 12 ).

A number of studies conducted in the last decade have assessed UIC in women of childbearing age and pregnant women in the UK( 8 , 13 – 19 ). Findings generally showed low median UIC, suggestive of iodine deficiency in these groups. Findings in the most recent report from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) rolling programme (2014/15 to 2015/16) are indicative of adequate iodine intake in the general female population of childbearing age, but are suggestive of iodine insufficiency in pregnant and lactating women( 20 ).

Differences in methods of assessment of iodine status have contributed to inconsistency in conclusions drawn by various studies. Therefore, the aim of the present systematic literature review was to critically analyse the quality of evidence on iodine status and draw considered conclusions regarding the prevalence of iodine deficiency among women in the UK.

Methods

The present systematic review was conducted based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement checklist( 21 ).

Search strategies

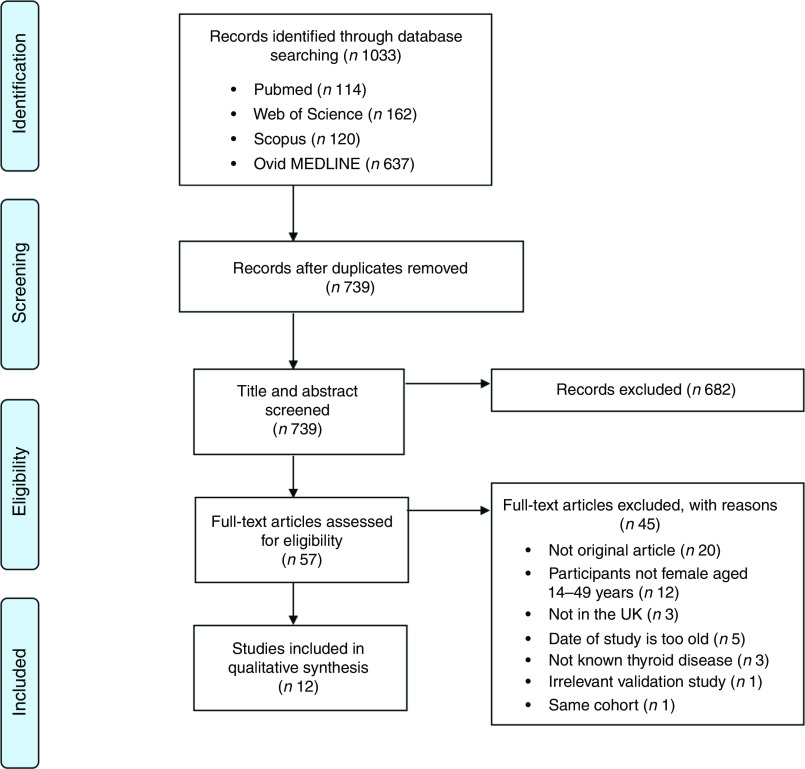

A systematic search of the literature was conducted on 14 September 2017 by two review authors (H.J. and G.S.R.) via four databases: Ovid MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus and PubMed. Keywords and Boolean operators utilized in each database were: ‘iodine deficiency’ OR ‘iodine status’ OR ‘iodine intake’ OR ‘iodine’ AND ‘women’ OR ‘young women’ OR ‘schoolgirl’ OR ‘childbearing age’ OR ‘pregnant women’ AND ‘UK’ OR ‘England’ OR ‘Scotland’ OR ‘Wales’ OR ‘Northern Ireland’. The search in Scopus was limited to ‘Keyword: Human, Humans’ and ‘Language: English’; the search in PubMed was limited to MeSH (Medical Subject Heading) terms ‘Humans’; and that in Ovid MEDLINE was refined by ‘English and Humans’. The literature search from all four databases generated a total of 1033 hits. The potential articles from each database were identified, exported and saved into EndNoteTM online version. Duplicates were removed, then relevant articles were scanned to confirm relevance by two authors (H.J. and G.S.R.). Eight authors were contacted for more detailed information related to their articles.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were developed by two authors (J.H. and R.S.G). Studies were selected according to the following eligibility criteria: (i) studies published as an original article with full text; (ii) participants are females classed as menstruating aged 14–49 years (data in females from mixed studies could be extracted independently); and (iii) primary outcome is iodine status of pregnant and non-pregnant females of childbearing age. Studies were excluded if: (i) the paper was secondary research, such as systematic reviews, review articles, author comments and conference abstracts; (ii) the article was not in the English language; (iii) the investigation did not take place in the UK or the participants had not lived in the UK for more than 1 year; and (iv) the participants were known to have thyroid disease or to have come from an identified iodine deficiency region.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The terms used for extracting the literature were discussed between all the authors; the data extraction was carried out independently by two authors (H.J. and G.S.R.) and reviewed by the other author (H.J.P.). Data were extracted as summarized below (Tables 1 and 2). The data collection aimed to gather the study characteristics of interest: study design, geographic region, characteristics of participants (age group and sample size), time of study, iodine status or estimated iodine status assessment method, and primary assessment results (urinary iodine status, dietary assessment results and other reference values).

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes of studies on iodine deficiency among pregnant/lactating women in the UK

| Study | Study design | Location and setting | Sample size (n) | Sampling season | Assessment method of iodine status | Median UIC (μg/l) | Dietary assessment results | Other reference value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath et al. (2013)( 19 ) | Cohort | South West England | 1040 | Whole year | Spot urine | 91·1 | NA | Median UIC/Creat = 110 μg/g |

| Bath et al. (2014)( 13 ) | Cross-sectional | South East England, local hospital | 100 | Summer | Spot urine | 85·3 | Use of iodine supplement (P <0·0001)* | Estimated 24 h iodine excretion = 151·2 μg/d |

| FFQ | Milk consumption (P = 0·007)* | Median UIC/Creat = 122·9 μg/g | ||||||

| Bath et al. (2015)( 16 ) | Cohort | Oxford, local hospital | 230 | Whole year | Spot urine | 56·8 | Milk consumption (P <0·001)* | Estimated 24 h iodine excretion = 143 μg/d |

| FFQ | Median UIC/Creat = 116 μg/g | |||||||

| Combet et al. (2015)( 36 ) | Cross-sectional | Glasgow and parts of the UK, local community or online survey | 1026 | Summer to winter | FFQ | NA | Median iodine intake = 190 μg/d | NA |

| Derbyshire et al. (2009)( 37 ) | Prospective observational | London | 42 | Unknown | 4 d food diary | NA | Mean daily iodine intake = 105 μg/d | NA |

| Kibirige et al. (2004)( 23 ) | Cross-sectional | North East England, local community | 227 | Unknown | Spot urine | NA | NA | Urinary iodide excretion (UIE) |

| Knight et al. (2017)( 17 ) | Cross-sectional | South West England, local hospital | 308 | Whole year | Spot urine | 88 | Increased milk intake (P = 0·02)* | NA |

| Dietary questionnaire | ||||||||

| Pearce et al. (2010)( 18 ) | Cross-sectional | Cardiff, local hospital | 480 | Unknown | Spot urine | 117 | NA | NA |

UIC, urinary iodine concentration; NA, not available; UIC/Creat, urinary iodine-to-creatinine ratio.

Associated with high iodine status.

Table 2.

Characteristics and outcomes of studies on iodine deficiency among non-pregnant/non-lactating women in the UK

| Study | Study design | Location and setting | Sample size (n) | Sampling season | Assessment method of iodine status | Median UIC (μg/l) | Dietary assessment results | Other reference value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath et al. (2014)( 14 ) | Cross-sectional | South East England, local community | 57 | Winter | 24 h urine collection | 63·1 | Median estimated iodine intake = 167 μg/d (urinary excretion); 123 μg/d (48 h food diary) | Median total 24 h urinary excretion = 149·8 μg/d |

| 48 h food diary | ||||||||

| Combet and Lean (2014)( 15 ) | Validation | Glasgow | 43 | Summer | 24 h urine collection | 74 | Median daily iodine intake = 103 μg/d (food diary); 110 μg/d (FFQ) | Median estimated iodine intake = 107·3 μg/d |

| 4 d food diary | ||||||||

| FFQ | ||||||||

| O’Kane et al. (2016)( 34 ) | Cross-sectional | UK and Ireland, online survey | 520 | Winter | FFQ | NA | Median estimated iodine intake = 152 μg/d | |

| Vanderpump et al. (2011)( 8 ) | Cross-sectional | Nine cities cross the UK | 737 | Winter | Spot urine | 80·1 | Low urinary iodine excretion linked to: | |

| Dietary questionnaire | Low intake of milk (P <0·03) High intake of eggs (P <0·02) |

UIC, urinary iodine concentration; NA, not available.

Following data extraction, the studies were critically appraised by focusing on the study design and the methods of iodine status assessment. Evidence was critically appraised by two authors (G.S.R. and H.J.) using the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)( 22 ) checklist tool and independently reviewed by the other authors. The quality assessment aims to assess strengths and limitations of observational research and a study’s generalizability. More specifically, the tool reviews items that relate to the different study sections (title, abstract, introduction, methods and discussion). The quality assessment related to the included studies (Table 3) comprised: description of contextual information, potential sources of bias, reporting of results and statistical analysis. Following study quality analysis, all aforementioned information was classed under ‘yes’ (which meant the source was provided) and ‘no’ (which meant the source was not provided). In instances where details of studies were not clear or unavailable, the ratings ‘not available’ and ‘not clear’ were used. The quality assessment relating to iodine status measurements (Table 4) were conducted by one author (H.J.) and independently reviewed by the other two authors. This assessment comprised the characteristics of iodine intake measurements in the targeted population. Overall quality rating of articles was expressed as ‘good’, ‘fair’ or ‘poor’. All disagreements related to eligibility criteria and quality assessment were discussed and resolved between the review authors.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of studies included in the present systematic review on iodine deficiency among women in the UK

| Research question | Description of setting, participant recruitment | Outline of eligibility criteria | Probability sampling | Justification of sample size | Standardization, validation of methods | Different levels of exposure measurement | Exposure measurement and assessment | Report outcome events | Statistical analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bath et al. (2013)( 19 ) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y |

| Bath et al. (2014)( 13 ) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bath et al. (2015)( 16 ) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Combet et al. (2015)( 36 ) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Derbyshire et al. (2009)( 37 ) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Kibirige et al. (2004)( 23 ) | Y | Y | NC | N | N | Y | Y | Y | NC | Y |

| Knight et al. (2017)( 17 ) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | NA | NC | Y |

| Pearce et al. (2010)( 18 ) | Y | Y | Y | NA | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bath et al. (2014)( 14 ) * | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| O’Kane et al. (2016)( 34 ) * | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Vanderpump et al. (2011)( 8 ) * | Y | Y | NC | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Y, yes; NC, not clear; N, no; NA, not available

Study in non-pregnant/non-lactating women.

Table 4.

Quality assessment of iodine status measurements of relevant studies on iodine deficiency among women in the UK

| Bath et al. (2013)( 19 ) | Bath et al. (2014)( 13 ) | Bath et al. (2014)( 14 ) * | Bath et al. (2015)( 16 ) | Combet and Lean (2014)( 15 ) * | Combet et al. (2015)( 36 ) | Kibirige et al. (2004)( 23 ) | Knight et al. (2017)( 17 ) | O’Kane et al. (2016)( 34 ) * | Pearce et al. (2010)( 18 ) | Vanderpump et al. (2011)( 8 ) * | Derbyshire et al. (2009)( 37 ) | NDNS (2018)( 20 ) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spot urinary sample collection | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| 24 h Urinary sample collection | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| UIC corrected by creatinine concentration | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Adequate sample size | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Preassessment of thyroid disease | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Nationally representative | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Reduced seasonal bias | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y |

| No contaminated urine sample | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | NA | N | Y | NA | Y |

| Overall quality rating | Good | Good | Fair | Good | Fair | Poor | Poor† | Fair | Poor | Poor | Fair | Poor | Good |

NDNS, National Diet and Nutrition Survey; UIC, urinary iodine concentration; Y, yes; N, no; NA, not available.

Study in non-pregnant/non-lactating women.

The inappropriate data reporting in Kibirige et al.’s study( 23 ) suggests a poor quality of iodine assessment design.

Results

Study selection

The records identified through the database searches yielded 1033 results. After removing 294 duplicates, 739 articles were eligible for further screening. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 682 articles were excluded, including non-original articles, studies on other diseases, studies not in the UK and participants with known thyroid disease. Fifty-seven articles were screened as full-text and assessed for eligibility. After excluding forty-five articles, a qualitative synthesis of twelve studies was performed. The process of study selection along with the number of included and excluded studies in the systematic review is depicted in the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(colour online) Flow diagram illustrating the screening process of eligible studies for the present systematic review on iodine deficiency among women in the UK

Study characteristics

The study characteristics are displayed in two tables, as the WHO iodine requirements differ between pregnant and non-pregnant women. Tables 1 and 2 present the main characteristics of the twelve included studies.

Eight out of twelve articles specifically targeted pregnant women, including one study( 16 ) which collected data from three trimesters of pregnancy, aiming to determine the changing iodine status throughout gestation. The remaining studies collected data once, at either the first trimester or final trimester of gestation. Six of those studies used urinary iodine assessment to measure iodine status. Four studies targeted the general female population of childbearing age. These studies mainly focused on women between 18 and 49 years of age, except for one study( 8 ) which investigated schoolgirls aged 14–15 years. A total of 5283 participants were included in the twelve studies, with sample sizes ranging from forty-two to 1040.

Eight out of twelve studies were cross-sectional studies. Two studies( 16 , 19 ) were cohort studies. Although the study by Kibirige et al. ( 23 ) was designated as having a case group and a control group, correspondence with the author determined that it should be classed as a cross-sectional study. Thus, that study was assessed and included in the present review as a cross-sectional study. However, considering the lack of appropriate statistical analysis and inappropriate reporting of UIC, that study’s data were not included when drawing conclusions. One validation study was also included in the present review( 24 ). Unlike the validation study by Combet and Lean( 15 ) that specifically validated the dietary assessment method for iodine status, the validation study by Mouratidou et al. ( 24 ) covered a broad range of nutrient assessments for pregnancy, not specifically focusing on iodine intake. Therefore, the latter study was not considered appropriate for inclusion in the present review. The validation study of Combet and Lean( 15 ) was not included in the quality assessment as it was not an observational study.

Table 3 displays the quality assessment of all studies, of which most were cross-sectional and cohort studies, so the assessment and scoring were conducted using the STROBE checklist tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies( 22 ). Table 4 reports the critical assessment of methods used for iodine status assessment for each study with reference to the NDNS. UIC is considered the most suitable method for assessing dietary iodine intake( 10 , 25 ). According to WHO guidelines( 11 ), median UIC is the most satisfactory method for identifying whether a population is at risk of iodine insufficiency. In this quality assessment, the studies that did not employ urinary iodine assessment were rated as ‘poor’ compared with other studies.

Discussion

The present systematic review is the first to appraise the evidence for poor iodine status among pregnant women and women of childbearing age in the UK. Heterogeneity in the initial iodine status measurements and study design make it difficult to draw an overall conclusion.

24 h Urinary iodine collection

Although 24 h urine collection is considered the reference standard for the estimation of iodine intake in an individual( 10 ) as it is more precise than spot urinary assessment, a single 24 h urine collection is considered to be a poor index for population data due to the day-to-day variation of iodine intake. A study suggested that, in a population, 24 h urine collection requires at least ten repeat collections from an individual to assess iodine status, with only 20 % precision rate( 26 ). Only two of our selected studies had used 24 h urine collection, with one study having done 24 h urine collection once( 14 ) and another study having done 24 h urine collection twice( 15 ). A notable feature of these two studies is that both of them had a relatively small sample size, with fifty-seven women( 14 ) and forty-three women( 15 ), respectively. There are practical constraints to conducting a large number of 24 h urine sample collections at a population level, but the small sample size in these studies constitutes a significant limitation and precludes generalizability to women of childbearing age in the UK population.

In the study of Bath et al. ( 14 ), although the median UIC (63·1 μg/l) indicates iodine deficiency, the median estimated iodine intake extrapolated from 24 h urinary excretion (149·8 μg/24 h) was 167 μg/d, suggesting adequate intake. The difference between these findings may be explained by the urine samples being dilute. In contrast, iodine intake estimated from 48 h food diaries was 123 μg/d, suggestive of deficient intake. The study is subject to selection bias as the participants were mainly students of nutrition and dietetics, who understood the importance of adequate iodine intake and its sources. Furthermore, samples were collected during the winter months when the iodine concentration in milk is higher than in summer( 7 ). Overall the findings of Bath et al.’s( 14 ) study should be treated as a best-case scenario of iodine status of women of childbearing age in the UK. The study by Combet and Lean( 15 ) reported median UIC of 74 μgl, also suggestive of iodine deficiency. While urine samples were collected during only summer and there would have been some seasonal bias, that study has only minimal selection bias because the participants were recruited randomly from the local community.

Spot urine sample collection

Conducting a spot urine sample collection in a population is far less cumbersome than a 24 h urine collection. There are three methods to report the iodine status value from spot urinary collection, which include simple UIC, iodine-to-creatinine ratio and age/sex-adjusted 24 h iodine excretion. The reporting of simple UIC is commonly used and recommended by the WHO for reporting iodine status in a population, as a median UIC( 11 ). The purpose of applying iodine-to-creatinine ratio is to minimize the variation that is caused by differences in urinary volume( 10 ). However, creatinine excretion is influenced by factors such as sex, age and genetic background( 27 ). When the groups are similar in age and of the same sex, correcting by creatinine concentration is valid( 28 ). In developed countries, the 24 h urine iodine excretion can be estimated from spot urinary samples and corresponding mathematical formulae( 28 ). Estimated 24 h urine iodine excretion can often be interpreted and extrapolated using the Estimated Average Requirement criteria.

Simple urinary iodine concentration from spot urine sample collection

Three of the selected studies were conducted using spot urine sample collection and reported simple UIC values only. To estimate iodine status in a population using spot urine samples it is recommended that 125 spot UIC samples are used, which is considered adequate to achieve a precision of ±10 %( 29 ). The sample size of these three selected studies all meet this recommendation, with sample sizes of 308( 17 ), 480( 18 ) and 737( 8 ), respectively.

A median UIC of 88·0 μg/l from a hospital-based study conducted in the south-west of the UK involving 308 pregnant women suggested this population had iodine deficiency( 17 ). However, that study showed a lack of detailed reporting of iodine assessment, such as the appropriate adjusted variation in UIC. That and a further hospital-based study( 18 ) did not generate nationally representative data.

Vanderpump et al. ( 8 ) conducted a survey across nine centres in the UK. The study collected 737 urine samples from schoolgirls aged 14–15 years, with a median UIC of 80·1 μg/l, suggesting a mild iodine deficiency in this group. The data may be considered nationally representative, with some caveats. The nutritional status of adolescent girls in the UK is generally poorer than for other age groups and poorer than for adolescent boys. NDNS data reported in 2018( 20 ) show 27 % of girls aged 11–18 years had an iodine intake from food sources less than the Lower Reference Nutrient Intake compared with only 14 % of boys of the same age and 15 % of women aged 19–64 years.

Vanderpump et al.’s study( 8 ) was the first nationwide survey of iodine status in young females and the findings did raise public attention and concern regarding iodine status and the consequences of iodine deficiency in the general population.

The latest report from the NDNS rolling programme (2014/15 to 2015/16)( 20 ) includes urinary iodine assessment in 426 women of childbearing age (16–49 years). The survey reported a median UIC of 102 μg/l, with 17 % below 50 μg/l. The findings suggest generally adequate iodine intake in this group, but values do not meet the WHO criterion of iodine adequacy in pregnant or lactating women. Although the method used in the NDNS( 20 ) of spot urine sample collection has limitations (as it uses only a single method of urinary iodine collection), NDNS data are considered to be representative of the UK population.

Urinary iodine concentration corrected by creatinine and estimated 24 h urine iodine excretion

Adjusting iodine concentration with creatinine can minimize the variation caused by differences in urinary volume( 10 ). Although urinary creatinine excretion is affected by protein intake, sex and age, the influence of these factors in the studies under scrutiny is likely to be low( 30 , 31 ). A sample size of 100 spot UIC samples with the value corrected by creatinine concentration satisfies requirements for a precision of ±10 %( 29 ).

Four of the studies( 13 , 16 , 19 , 23 ) in the present review reported iodine status using urinary iodine-to-creatinine ratio. Two of these studies( 13 , 16 ) estimated 24 h iodine excretion by adjusting for sex and age of the individual. All these studies had a sample size of more than 100, giving greater credibility to the findings of these studies compared with smaller studies. In the 2013 study by Bath et al. ( 19 ) (sample size n 1040), the median UIC was 91·1 μg/l and the adjusted median iodine-to-creatinine ratio was 110 μg/g, indicating that this group of pregnant women was mildly-to-moderately iodine deficient. The urine samples were collected in the early 1990s, when the consumption of milk, a good dietary source of iodine, was higher than the present day( 8 ), suggesting that current iodine status in this group may actually be lower. Potential contamination of urine samples with urine test strips containing iodine in Bath et al.’s study( 19 ) reduced the sample size for analysis to 958( 32 ), but this remains a much larger sample than in most other studies of this nature. The study suggests a high risk of iodine deficiency in pregnant women in the UK.

A further study( 16 ) from Bath et al. in 2015 involving 230 pregnant women aimed to investigate the change in iodine status during pregnancy. A median iodine-to-creatinine ratio of 116 μg/g classified this group as mildly-to-moderately deficient, and the median Estimated Average Requirement was 143 μg/24 h, which had 55·7 % of participants below the cut-off of 160 μg/24 h. The study reduced seasonal bias by using year-round recruitment, but the sample collection was conducted locally and could not be generalized to the national population. A smaller study also carried out by Bath et al. in 2013( 13 ) drew similar conclusions regarding the likelihood of mild to moderate iodine deficiency among pregnant women in the south-east of England. The study by Kibirige et al. ( 23 ), which was conducted in the north-east of the UK involving 227 pregnant and 227 non-pregnant women, reported a small proportion with moderate iodine deficiency in its target groups (3·5 % of pregnant women, 5·7 % of non-pregnant women) on the basis of urinary iodine-to-creatinine ratio. However, that study did not show figures for median UIC and median iodine-to-creatinine ratio, limiting the strength of the evidence.

Overall, these studies, which were all conducted with spot urine samples and used the iodine-to-creatinine ratio, suggested a risk of iodine deficiency in pregnant women.

Dietary iodine assessment

Dietary iodine intake can be used to estimate iodine status, although this approach has limitations. Estimates of the iodine content of foods vary substantially; such variability is seen between similar foods, geographical location (as iodine content in soil differs between regions and countries), and even within the same (fish) species reared under different farming conditions( 33 ). Additionally, there are only a few food composition databases containing information on iodine-rich foods( 25 ) and the studies included in the present systematic review generally failed to report the selected dietary database or provide detail about dietary analysis. Five studies( 13 – 16 , 34 ) selected for the systematic review included dietary assessment for salt intake, and four studies indicated the iodized salt consumption by their participants( 13 , 14 , 16 , 34 ). None of these studies reported an association between salt intake and iodine status. This may be due to the fact that iodized salt is not widely available in the UK. Also, dietary assessment methods (such as FFQ) have been shown to be inaccurate for estimating iodized salt intake because of the difficulty in capturing the exact amount of ingested salt( 25 , 35 ). However, the food diary method seemed to be a reliable approach to estimating iodine intake in the small study among women of childbearing age by Bath et al. ( 14 ), as a strong correlation (P <0·001) was found between iodine intake assessed from 48 h food diaries (123 μg/d) and 24 h urinary iodine excretion (149·8 μg/24 h). The 4 d food diary used in the NDNS also produced high-quality data for iodine intake by extending the collection period and thereby reducing the day-to-day variation. Findings showed an average iodine intake of 101 μg/d in girls aged 11–18 years and 140 μg/d in women aged 19–64 years (27 and 15 %, respectively, being below the Lower Reference Nutrient Intake)( 20 ). All of the nine studies that included dietary assessment of iodine intake, and the dietary assessment of NDNS( 20 ), suggested that milk consumption was associated with higher iodine status. In a study among pregnant women in the UK, Combet et al. ( 36 ) reported poor awareness of iodine-specific recommendations (12 %) and that only a minority of women (28 %) expressed confidence in knowing how to achieve adequate iodine intake.

Iodine status

It is not possible to generalize data from single studies of iodine status to the UK population. Based on the quality ranking of the iodine assessment in Table 4, the present review drew conclusions about iodine status in women in the UK from the studies that had been rated as ‘good’ and ‘fair’. The use of different biomarkers for iodine status as well as thresholds for deficiency makes it difficult to compare data across studies. According to the latest UNICEF guidelines, median UIC should not be used to determine the proportion of a population with inadequate iodine intake( 12 ). Two of the selected studies( 8 , 23 ) made potentially misleading statements regarding the proportion with inadequate iodine intake in their sample population. However, the consistent reporting of low iodine intake among the selected studies should be enough to raise concerns about iodine status in women of childbearing age and pregnant women in the UK.

Limitations

The main limitation in the present systematic review is the absence of statistical analysis which was due to the heterogeneity in methods of iodine status assessment within the various studies.

Notwithstanding limitations in the data, on the basis of dietary assessment and biomarkers of iodine intake, the present review concludes that women of childbearing age and pregnant women in the UK are generally iodine insufficient.

Conclusion

Adequate iodine intake is important for women of childbearing age, particularly if pregnant/lactating or if planning pregnancy, as this may affect fetal brain development, cognitive function and IQ levels in the offspring. In the present review, most papers described small-scale studies with various limitations in study design and methods used for assessing iodine status. Although the present systematic review highlights methodological limitations and an overall lack of strong evidence on the topic, findings are consistent with generally poor iodine status in women of childbearing age and pregnant women in the UK. This indicates a need for implementing programmes to monitor iodine status in the general population. Further large-scale research is required for more accurate and reliable evidence on iodine status in the UK.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The study did not receive any specific non-financial support. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: H.J., H.J.P. and G.S.R. contributed to the research design. H.J. and G.S.R. conducted the database searching and the screening procedure. H.J. and G.S.R. completed data extraction and quality ratings and drafted the manuscript. All authors provided analytical support, commented on drafts and read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required.

References

- 1. Zimmermann MB (2009) Iodine deficiency. Endocr Rev 30, 376–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fierro-Benitez R, Cazar R, Stanbury JB et al. (1988) Effects on school children of prophylaxis of mothers with iodized oil in an area of iodine deficiency. J Endocrinol Invest 11, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andersson M, De Benoist B, Darnton-Hill I et al. (2007) Iodine Deficiency in Europe: A Continuing Public Health Problem: Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bath SC & Rayman MP (2015) A review of the iodine status of UK pregnant women and its implications for the offspring. Environ Geochem Health 37, 619–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zimmermann MB (2010) Iodine deficiency in industrialised countries. Proc Nutr Soc 69, 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Benoist B, McLean E, Andersson M et al. (2008) Iodine deficiency in 2007: global progress since 2003. Food Nutr Bull 29, 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Phillips DI (1997) Iodine, milk, and the elimination of endemic goitre in Britain: the story of an accidental public health triumph. J Epidemiol Community Health 51, 391–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vanderpump MPJ, Lazarus JH, Smyth PP et al. (2011) Iodine status of UK schoolgirls: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 377, 2007–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ovesen L & Boeing H (2002) The use of biomarkers in multicentric studies with particular consideration of iodine, sodium, iron, folate and vitamin D. Eur J Clin Nutr 56, Suppl. 2, S12–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vejbjerg P, Knudsen N, Perrild H et al. (2009) Estimation of iodine intake from various urinary iodine measurements in population studies. Thyroid 19, 1281–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization/UNICEF/International Council for Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders (2007) Assessment of Iodine Deficiency Disorders and Monitoring their Elimination: A Guide for Programme Managers: Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 12. UNICEF (2018) Guidance on the Monitoring of Salt Iodization Programmes and Determination of Population Iodine Status. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bath SC, Walter A, Taylor A et al. (2014) Iodine deficiency in pregnant women living in the South East of the UK: the influence of diet and nutritional supplements on iodine status. Br J Nutr 111, 1622–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bath SC, Sleeth ML, McKenna M et al. (2014) Iodine intake and status of UK women of childbearing age recruited at the University of Surrey in the winter. Br J Nutr 112, 1715–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Combet E & Lean ME (2014) Validation of a short food frequency questionnaire specific for iodine in UK females of childbearing age. J Hum Nutr Diet 27, 599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bath SC, Furmidge-Owen VL, Redman CW et al. (2015) Gestational changes in iodine status in a cohort study of pregnant women from the United Kingdom: season as an effect modifier. Am J Clin Nutr 101, 1180–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knight BA, Shields BM, He X et al. (2017) Iodine deficiency amongst pregnant women in South-West England. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 86, 451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pearce EN, Lazarus JH, Smyth PP et al. (2010) Perchlorate and thiocyanate exposure and thyroid function in first-trimester pregnant women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95, 3207–3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bath SC, Steer CD, Golding J et al. (2013) Effect of inadequate iodine status in UK pregnant women on cognitive outcomes in their children: results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Lancet 382, 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roberts C, Steer T, Maplethorpe N et al. (2018) National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Results from Years 7 and 8 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2014/2015–2015/2016). London: Public Health England. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62, e1–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al. (2008) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61, 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kibirige MS, Hutchison S, Owen CJ et al. (2004) Prevalence of maternal dietary iodine insufficiency in the north east of England: implications for the fetus. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 89, F436–F439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mouratidou T, Ford F & Fraser RB (2006) Validation of a food-frequency questionnaire for use in pregnancy. Public Health Nutr 9, 515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rohner F, Zimmermann M, Jooste P et al. (2014) Biomarkers of nutrition for development – iodine review. J Nutr 144, issue 8, 1322S–1342S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Konig F, Andersson M, Hotz K et al. (2011) Ten repeat collections for urinary iodine from spot samples or 24-hour samples are needed to reliably estimate individual iodine status in women. J Nutr 141, 2049–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haddow JE, McClain MR, Palomaki GE et al. (2007) Urine iodine measurements, creatinine adjustment, and thyroid deficiency in an adult United States population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92, 1019–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Knudsen N, Christiansen E, Brandt-Christensen M et al. (2000) Age-and sex-adjusted iodine/creatinine ratio. A new standard in epidemiological surveys? Evaluation of three different estimates of iodine excretion based on casual urine samples and comparison to 24 h values. Eur J Clin Nutr 54, 361–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andersen S, Karmisholt J, Pedersen KM et al. (2008) Reliability of studies of iodine intake and recommendations for number of samples in groups and in individuals. Br J Nutr 99, 813–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bourdoux P (1998) Evaluation of the iodine intake: problems of the iodine/creatinine ratio – comparison with iodine excretion and daily fluctuations of iodine concentration. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 106, Suppl. 3, S17–S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kesteloot H & Joossens JV (1996) On the determinants of the creatinine clearance: a population study. J Hum Hypertens 10, 245–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pearce EN, Lazarus JH, Smyth PP et al. (2009) Urine test strips as a source of iodine contamination. Thyroid 19, 919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rasmussen LB, Ovesen L, Bulow I et al. (2002) Dietary iodine intake and urinary iodine excretion in a Danish population: effect of geography, supplements and food choice. Br J Nutr 87, 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O’Kane SM, Pourshahidi LK, Farren KM et al. (2016) Iodine knowledge is positively associated with dietary iodine intake among women of childbearing age in the UK and Ireland. Br J Nutr 116, 1728–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zimmermann MB & Andersson M (2012) Assessment of iodine nutrition in populations: past, present, and future. Nutr Rev 70, 553–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Combet E, Bouga M, Pan B et al. (2015) Iodine and pregnancy – a UK cross-sectional survey of dietary intake, knowledge and awareness. Br J Nutr 114, 108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Derbyshire E, Davies GJ, Costarelli V et al. (2009) Habitual micronutrient intake during and after pregnancy in Caucasian Londoners. Matern Child Nutr 5, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]