Abstract

Objective:

While scholarship has investigated how to provide more healthy food options in choice pantry environments, research has just begun to investigate how pantry users go about making decisions regarding food items when the ability to choose is present. The present analysis sought to investigate the factors prohibiting and inhibiting food decision making in choice pantries from the perspective of frequent pantry users.

Design:

Six focus group interviews were conducted with visitors to choice food pantries, to discuss the decision-making process involved in food selection during choice pantry visits. Each was provided a $US 15 remuneration for taking part.

Setting:

A school-based choice food pantry in Anderson, Indiana, USA, a small Midwestern community.

Participants:

Thirty-one men and women, largely aged 45–64 years, who made use of choice food pantries at least once monthly to meet their family’s food needs.

Results:

Choice pantry visitors indicated that the motivation to select healthy food items was impacted by both individual and situational influences, similar to retail environments. Just as moment-of-purchase and place-of-purchase factors influence the purchasing of food items in retail environments, situational factors, such as food availability and the ‘price’ of food items in point values, impacted healthy food selection at choice pantries. However, the stigmatization experienced by those who visit pantries differs quite dramatically from the standard shopping experience.

Conclusions:

Choice pantries would benefit from learning more about the psychosocial factors in their own pantries and adapting the environment to the desires of their users, rather than adopting widely disseminated strategies that encourage healthy food choices with little consideration of their unique clientele.

Keywords: Choice pantry, Decision making, Food selection

Food insecurity, a socio-economic condition in which households have limited or uncertain access to adequate food, is a significant problem for over one million Indiana citizens each year. In fact, according to recent estimates provided in Feeding America’s 2017 report Map the Meal Gap, one in seven Indiana residents is food insecure( 1 ). In Delaware County, Indiana alone, over 33·4 % of community citizens live at or below the poverty line and over 66 % of children receive free or reduced-price school lunches( 2 ). Indiana figures exceed those available at the national level. Recent reports on 2016 food insecurity figures from the US Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service indicate that national levels remain at just over 12 % of US households experiencing food insecurity, a value that was ‘essentially unchanged’ from the previous year( 3 ).

Food-insecure individuals are at a higher risk for diet-related diseases such type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity( 4 ). The impact of poor nutrition, specifically, is directly associated with the cost of medical expenditures related to the diagnosis and treatment of illnesses connected to poor food choices. In their analysis of the 2011 National Health Interview Survey, Berkowitz et al. found that those with food insecurity had significantly greater estimated mean annualized health-care expenditures (an extra $US 1863 in health-care expenditures per year)( 5 ). Food insecurity was associated with greater emergency department visits, inpatient hospitalizations and days hospitalized. As a subgroup of the greater population of food-insecure citizens, individuals who rely on food pantries to meet their nutritional demands experience unique health risks. Research has found that food pantry clients may be at greater risk for poor health due to increased incidence of diet-related chronic diseases and foodborne illnesses. Food pantry clients tend to report higher BMI and lower fruit and vegetable consumption than their food-secure counterparts( 6 ). Establishing an understanding of the factors underlying the relationship between food pantry use and poor health outcomes has been an increasing area of interest for nutrition scholarship( 6 – 8 ).

Despite the connection between food pantry usage and poor health outcomes, scholarship has yet to define the moderating factors underlying this relationship. One potential factor includes the availability of healthy items within pantry spaces, which is often dictated by the amount of monetary resources, space and personnel a pantry possesses to provide for the acquisition and handling of such items. In many pantries, the decision of what foods to provide to clients is based on adherence to pre-existing state policies detailing the cost and availability of governmental commodity products. The Indiana State Department of Health, for example, allocates commodity food products to pantries by applying a formula, which is 60 % of the poverty level and 40 % of the unemployment population in each geographic service area living at 185 % of the poverty level. In order to receive government food commodities, distribution sites are to: (i) be established and in operation for a minimum of 2 years; (ii) be open to the public a minimum of 2 h each month; and (iii) have 501(c)3 status or be a local government entity( 9 ). In recent reference, Indiana expanded its Food Drop participation to include its nine largest hunger relief organizations across the state. As part of this programme, information regarding the nearest charitable assistance locations will be provided to perishable food delivery services whose products have been rejected from drop-off locations (often due to not meeting size or colour standards)( 10 ). Instead of paying fees for product disposal, drivers can receive tax-deductible receipts for providing perishable foods to emergency assistance locations.

Indiana is just one example in a myriad of varied food pantry policies related to the provision of nutritious items to clients. Handforth and Henninck assessed nutrition-related policies and practices among a sample of twenty food banks from the national Feeding America network( 11 ). Most food bank personnel reported efforts to provide more fresh produce to their communities, and several described nutrition-profiling systems to evaluate the quality of products. However, a number of obstacles to nutrition initiatives emerged, particularly in relation to the fear of reducing the total amount of non-perishable healthy items and discomfort choosing which foods should not be permitted( 12 ). Establishing strong nutrition policies at food banks and pantries is another suggested strategy to improve the nutritional quality of food distributed; however, such changes have the potential to alter relationships with existing donors, possibly reducing the total amount of food available for distribution( 12 ). Interviews with food bank and food pantry personnel suggest that other challenges to adopting healthy food initiatives include the procurement, handling and monitoring of large quantities of perishable foods( 12 ).

An increasing number of pantries across the USA are now adopting the ‘user-choice’ or ‘customer-choice’ model, where users are able to choose food items off shelves with the help of a volunteer instead of receiving a pre-packaged bag( 13 ). This gives users the opportunity to choose from a wide variety of foods to meet their own personal dietary needs and tastes. Alternatively, non-choice food pantries provide users with boxes or bags of pre-determined food with limited opportunity to exchange or select items of their own. While scholarship has investigated from various perspectives how to provide more healthy food options, research has just begun to investigate how pantry users go about making decisions regarding food items when the ability to choose is present. In the retail setting, low-income individuals often find it difficult to incorporate fruits and vegetables into meals because of high costs, unavailability of these foods in nearby markets and lack of experience with food preparation( 14 , 15 ). Low-income households purchase more discounted items and store brand products, take greater advantage of volume discounts and purchase less expensive versions of a given product compared with higher-income households( 16 ). In an investigation of ninety-two women making use of food stamps to meet their family’s food needs, Wiig and Smith found that food choices and grocery shopping behaviour were shaped by not only individual and family preferences, but also environmental factors( 17 ). Specifically, transportation and store accessibility were major determinants of shopping frequency. The participants engaged in a variety of tactics to ensure that their dollars ‘stretched’, including shopping based on specials in store. Meat was a priority, and fruits and vegetables were less often purchased, largely due to their short ability to stretch (due to spoiling).

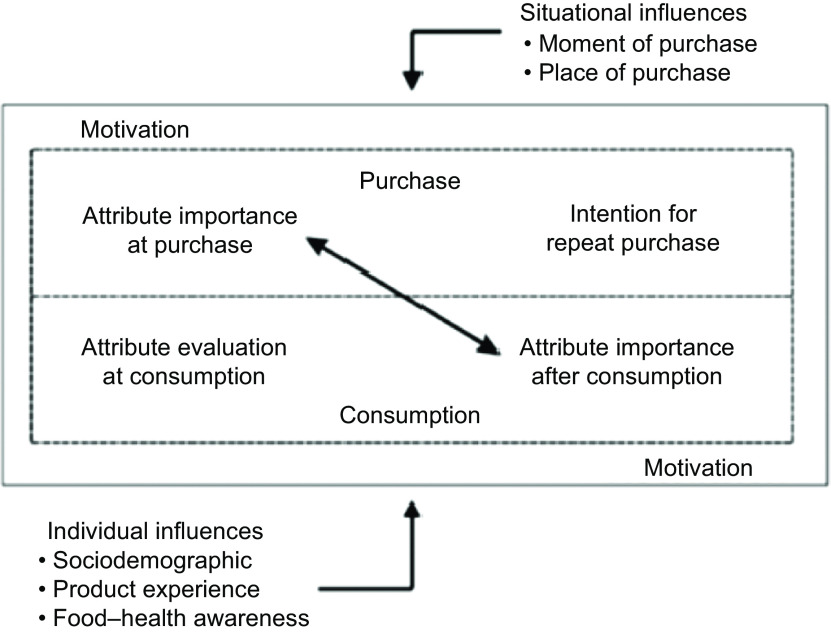

While less scholarship has investigated how choice pantry clients make food decisions and what factors influence decisions at the point of selection, a rich body of research has investigated what factors impact consumer food decisions in retail settings. Numerous variables have been found to influence consumer’s decision-making processes. Individual sociodemographic characteristics are commonly included as determinants of attitudes, perception and choice( 18 ). Furthermore, consumer motivation has been found to depend on both individual and situational characteristics, and motivation strongly relates to the formation of attitudes, preferences and ultimate food choice( 19 ). According to the class attitude–behaviour model (see Fig. 1) established by Engel et al., during their decision-making process consumers rely on different attributes or cues before deciding whether or not to buy and which product to choose( 20 ). Evaluative criteria may change depending on previous experience and the stage in the decision-making process because consumers may gradually become aware of product attributes that were not experienced before purchase( 21 ). Zeithaml reported that consumers tend to rely on extrinsic attributes such as the package and its specific characteristics in situations where relevant intrinsic attributes (like taste, odour and texture) could not be evaluated before buying the products( 22 ). Once experienced, these intrinsic (experience) attributes can be expected to gain importance as evaluative criteria in later food selections.

Fig. 1.

Individual and situational influences on consumer food selection. (Adapted from Engel et al.( 20 ))

One might suggest that, in situations where choice is available, some of the factors impacting food decisions in retail settings might also be present in evaluating food selections in a choice pantry environment. As the above model suggests, sociodemographic factors, product experience, awareness of the healthfulness of food selections and one’s own health status all function as individual influences on motivation, purchase and consumption. The model also argues that situational influences, like the place of purchase, may impact motivation in similar fashion as individual factors. While choice pantry environments have been structured to appear like grocery stores, the amount and variety of foods are much more limited, which may serve to alter what foods are selected in-moment. As noted above, there is a paucity of scholarship addressing the decision making that takes place on behalf of choice food pantry clients, and research has yet to consider the potential ways that an understanding of consumer food selection could apply to situations where pantry clients have the ability to shop for items among a variety of healthy and unhealthy options. The present analysis sought to investigate if the class attitude–behaviour model of product selection could be applied in a setting where price was removed as a consideration, namely the choice pantry environment. In application, the research aimed to uncover how the motivators to food selection (at the individual influence level and situational influence level) apply in ways similar to and different from the retail setting.

Methodology

Recruitment

To assess the decision-making processes involved in food selections at choice food pantries, the present analysis targeted those individuals who make use of one or more choice food pantries to meet their food needs. Our recruitment of study participants took place at one choice food pantry within a county-service area reaching over 20 000 individuals in poverty across twenty-one operating food pantries. However, of those twenty-one pantries, only three make use of the choice model of distribution. Considering the limited sample of choice pantries, no attempt was made to randomize selection of sites. While all three were approached, only one agreed to permit the recruitment of participants at the pantry. However, a number of individuals taking part indicated their use of the other choice food pantries in the area. Participants were notified of the study by a flyer that announced participant criteria and that a $US 15 cash remuneration would be provided for participating. Qualifying participants were responsible for purchase of food and preparation of meals for the family, were English speaking, and had made use of at least one choice pantry in the past 30 d to meet their food needs. Clients were personally screened by one of four programme staff and given consent forms prior to their participation. All study documents are procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board.

Data collection

Up to twelve participants were recruited for each focus group session to help ensure an actual focus group size of eight to ten. A total of six focus groups were held with participants of the pantry. The primary faculty investigator on the project worked collaboratively with pantry staff and food bank administrators to design the discussion guide, and this same faculty member served as the moderator of all focus groups at the pantry site. The discussion guide included warm-up questions about overall health and wellness activities, obtaining food and preparing meals. Core questions tapped participants’ typical experiences making food decisions at choice pantries, asking each to reflect upon the last time they ‘shopped’ at a choice pantry. Each was asked to provide insight into the kinds of foods they routinely chose, what items were reserved as ‘non-essential’, and when and how they made choices (e.g. ‘When you’re considering what to pick at the pantry, what do you think about that helps you decide?’). In addition, participants were invited to discuss sources of nutrition education for the family, as well as choose nutrition education topics that were of greatest interest. Participants were also asked about their use of and experiences with food and nutrition services available in the area. Demographic information (age, race, gender and household characteristics) was collected using a short questionnaire designed by the research team and administered after the focus group session. The focus groups ranged in duration from 36 min to 1 h and 24 min, and all were audio-recorded (after discussing the informed consent document with participants) to permit data transcription and analysis. Each focus group was presented the same questions from the moderator guide, with no additional questions presented to any group uniquely.

Content analysis

Audio tapes from the focus group sessions were transcribed and then reviewed by the focus group moderator for accuracy. Transcribed focus group data were analysed by using methods informed by qualitative content analysis, which is widely used to interpret text data through systematic coding and identification of content themes or patterns( 23 , 24 ). Two investigators with complementary skills served as primary coders. First, coders independently read each transcript and noted initial impressions of the data. Next, each reread the transcripts and developed line-by-line coding. Coders then compared codes, jointly developed a preliminary coding scheme and operationalized codes. After independently coding each transcript, coders debriefed and revised the coding scheme. Codes were grouped into themes appearing across all six groups. Microsoft Word cut-and-paste functions were used to organize coded data. A number of major themes emerged from the analysis. At this point, a seventh focus group was held with participants not otherwise represented in the broader pool. During this group, participants were presented with the list of themes devised by the coding team and asked to provide feedback regarding the consistency of the broader themes represented with their own experiences. The participants confirmed the categorization, adding to the content validity of the data. Illustrative quotations, edited for clarity and anonymity, are provided to characterize each theme.

Threats to external validity were minimized by using the same recruitment techniques and focus group moderator for all group sessions. In addition, attempts were made to address ‘setting effects’ by offering sufficient compensation such that participants could make accommodations for children or other dependants during that time. Prior to content analysis, content categories and their definitions were reviewed to establish face and content validity. Comments that were unique to one group were noted and reported in an attempt to minimize inaccurate generalizations and expose important data about a particular experience or pantry setting.

Results

In recognizing the contribution that may be afforded by directly comparing and contrasting retail settings and the choice pantry environment in light of individual and situational influences on food selection, the results are organized with the attitude–behaviour model discussed previously in mind. The first subsection details the important family food allocation guidelines and point value designations at the pantry, to provide insight into the context of the study and analysis. Then, the ‘Individual influences on motivation to select healthy foods’ subsection elaborates on those individual influences motivating the selection of food in choice pantry environments, and the ‘Situational influences on motivation to select healthy foods’ subsection attends to those situational factors external to the participant that appeared to impact food selection in the pantry environment. As will be discussed, while many of the internal influences on motivation mirror those motivations encouraging food selection in retail settings, there are a variety of situational influences, unique to each person, that impact motivation in different ways from those present in retail settings. Quotes are provided, when appropriate, to elaborate these emergent themes; parenthetical citations are noted, following each quote, to designate from which each focus group (in chronological order; e.g. FG1, FG2) the quote originated.

In consideration of our focus group respondents, a total of thirty-one individuals participated in the focus groups (see Table 1). With a range of 18 to 65 years or older, the most common age group was 45–64 years old (49 %). Most of the participants were female (58 %) and African American (49 %). Many stated that they were unemployed (51 %) and utilized food pantries at least once monthly (45 %).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of focus group participants: men and women (n 31) attending a school-based choice food pantry in Anderson, Indiana, USA, July 2017

| Characteristic | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 | 39 |

| Female | 18 | 58 |

| Did not answer | 1 | 3 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 0 | 0 |

| 25–44 | 9 | 28 |

| 45–64 | 15 | 49 |

| ≥65 | 6 | 20 |

| Did not answer | 1 | 3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American | 15 | 49 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 3 |

| Caucasian | 12 | 38 |

| Did not answer | 3 | 10 |

| Frequency of utilizing food pantries | ||

| Only when needed (<6 times/year) | 2 | 6 |

| Every other month | 2 | 6 |

| Once monthly | 14 | 45 |

| More than once monthly | 6 | 20 |

| Volunteer | 1 | 3 |

| Did not answer | 6 | 20 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 4 | 13 |

| Unemployed | 16 | 51 |

| Disabled | 3 | 10 |

| Retired | 2 | 6 |

| Did not answer | 6 | 20 |

| Utilization of food share or other forms of government assistance to help with food and food costs | ||

| Yes | 10 | 33 |

| No | 17 | 54 |

| Did not answer | 4 | 13 |

Food allocation and point value guidelines

In Indiana, households are eligible to receive federal commodity food products if the total gross household income is within federal income guidelines of 185 % of the poverty level, which is a requirement of all food pantries in a service area. Indiana uses the method of self-declaration to determine eligibility, in that food outlets will not require specific documentation (social security numbers, for example) for income verification purposes. All eligible recipients must also be residents of Indiana for at least one day, and food outlets may not stipulate an additional length of the residency requirement. Food outlets may require recipients be residents of the county in which they receive product, and some food outlets require further residency requirements within zip codes or neighbourhoods.

At most client choice pantries, the rules for obtaining products are set forward by each pantry administrator, who often makes decisions regarding point values and food selection based upon momentary item availability from food banks, commodity prices and personal judgement. At this particular pantry, the administrator shared that items received in greater quantity (due to their low cost from the food bank) were priced with lesser point values, whereas items received in lower quantity (due to their cost from the food bank) were priced with higher point values. There was no consideration of matching point values to actual product prices, and the type and price of food items varied across different pantry distribution days. Across days, the nature of healthy options could range from fresh fruits and vegetables to only canned options, lean bacon and turkey to fatty ground beef, or wholegrain breads to sugary cupcakes and muffins. On one day, for example, every food item was worth 1 point. The only limitation to selection was placed on the availability of one whole turkey per family. On another day, fruit and vegetable items were worth 2 points, proteins were worth 2 points, and all other items were worth 1 point. Those families with a household size of two to four members were provided 16 points to use, with 4 provided to protein and 4 to produce. The remaining points were to be allocated to all other items, with the stipulation that any unused protein and produce points could be used in the ‘other items’ category. Households of five to seven members saw an increase to 24 total points, with 6 to protein and 6 to produce. Households of eight members were allocated 34 points, with 8 to protein and 8 to produce. Household size was often self-reported to an attendant at a check-in desk, with no requirement for documentation to establish the size of family reported.

Individual influences on motivation to select healthy foods

Participants described a number of influences on motivation to select healthy foods, such as wholegrain breads, lean meats, fruits and vegetables. These influences were unique to each participant, personalized to their individual attitudes, experience and interest in food items. Several participants indicated that product experience was a significant factor impacting whether or not they choose a healthy food item. They often noted an interest to select ‘what I’m familiar with’ or ‘what I know how to cook’. As one participant discussed:

‘I don’t get things that look complicated. I know others that don’t get it because they’ve never heard of it before.’ (FG2)

In their conversations regarding experience, participants often integrated thoughts regarding how their own childhood experiences and family eating environments impacted their selections and willingness to try new food items that might be healthier. When asked explicitly regarding how food selections were made, one participant went so far as to say:

‘I get the main things like eggs, milk and bread, the stuff that your parents would always get.’ (FG4)

Another noted:

‘We never had fruits or vegetables. Prunes were candy to us. We didn’t look at it as healthy, but it was. If I had meat and potatoes, I was good. That’s probably why I don’t eat vegetables.’ (FG1)

The authors were struck by moments where participants would become boisterous in their agreement over those foods that were common during their childhood that they desired as adults. One of those items noted across half of our focus groups was ‘government’ cheese. In FG2, three participants discussed their interest in the cheese that was no longer available at the pantry. Their discussion follows:

‘I wish they wouldn’t have gotten rid of that cheese.’

‘Yeah, I remember that, you’re right! Why did they stop that?’

‘They shipped it overseas, that and peanut butter. They shipped it overseas for other people to have.’

Conversely, one participant noted how her consumption of the cheese as a child led to her current dislike, noting:

‘I can’t eat spam or that cheese because we had it so much growing up. We were poor growing up. We had spam for breakfast, lunch and dinner.’ (FG5)

It was clear that experience with a healthier food item at some point prior to the pantry visit led to increased familiarity and greater interest in selecting the healthy item. This matches the work of Monsivais and Drewnowski, which confirmed the role that experience with food items played in their selection by low-income shoppers in the retail environment( 15 ). When a healthier food item was not familiar to a client, due to a lack of personal experience with the item, the item was not often selected.

Similar to experience, a number of participants discussed how routine would impact their selections in the choice pantry, as well as in retail settings. Participants often indicated the value in sticking to a routine when they noted that something was selected because it was ‘what they usually cooked’ (FG2), with some even explicitly noting that it was ‘part of my routine’ (FG4). For those participants who were also parents, the routineness of items when cooking for their children also influenced their decisions regarding whether or not to choose the food at the pantry. One mother discussed:

‘I like to stick with stuff I know they like. It’s very rare we try different foods. They eat a lot of pasta, chicken alfredo and hamburger helper. I choose things I know they will eat.’ (FG2)

Even in the choice pantry environment, where price is removed as a barrier, the foods that participants said their families often selected were those that matched existing routines. These routine foods, as constrained by budgeting concerns in the retail settings, were often inexpensive, highly processed convenience foods that were quick to prepare. Many of those foods discussed as routine pantry selections for one individual were shared across participants, including items like macaroni and cheese, beans for chilli, frozen chicken for chicken and noodles, and snack cakes. While participants noted some difficultly in accessing these items consistently across different pantries, there was generally very little variety in food items individuals would commonly select.

Another individual influence on the selection of food in the choice pantry environment was one’s perception of the ability to stretch the food item across multiple meals. Ways of stretching foods in the home included making food in bulk, using up leftovers and freezing foods for later use. Starchy foods were often consumed to fill up a family, and meat and dairy portions were reduced significantly on a regular basis. As one mother noted:

‘I always choose the stuff to make pancakes because that always fills the kids up. Things that stretch.’ (FG2)

Multiple participants mentioned serving smaller portions each night out of a bigger prepared meal as a way to stretch the food supply. One noted:

‘I choose foods at the pantry and use what I have from food pantries to meal plan, to stretch it out and last longer. I make big portions so it will last longer.’ (FG6)

Even though food is not purchased at a choice pantry, the use of the point system to allocate how much of and what foods individuals can select still serves to impact food decision making. In one instance, if meat items are ‘priced’ at a higher point value than snack items, it seemed as though clients underwent a similar decision-making process as in the retail environment regarding what foods will provide the most longevity. The use of points here presents a similar consideration to that of monetary cost in the retail environment. The role of product cost (whether that be in money or points) is bargained in connection to the ability of the item to stretch across multiple meals. Alternatively, when a wider variety of options was present at a choice pantry, participants noted an interest in selecting items at the pantry that were of higher monetary value in retail settings and passing on those items of lesser value (often provided for free or at a low point value in the pantry). This was justified by the premise that the potential to purchase those items in the retail setting would be high. This internal point-to-cash value exchange was expressed as a common factor influencing what items were selected. As one participant clearly noted:

‘I buy the cheap foods at the grocery store with what money I have. I use the pantry for the expensive things that I know will last a while, like chicken or burger. I don’t waste my points on the easy things I still can get from Walmart.’ (FG5)

A final individual factor influencing one’s motivation to choose more nutritious food in the choice pantry related to an individual’s personal interest in planning meals. This factor connects closely with both routine food selection and the choice of items that can stretch, as many individuals noted that they planned out their meals around what was routine and what could stretch. Their accompanying decisions in the choice pantry matched to these plans. Some participants noted that they would investigate what food items would be on sale in stores for a given week, and then their pantry choices would match what other items they would need to plan for those meals. One participant suggested:

‘My husband gets paid on weekends, so we plan weekly. What I look for at the pantry depends what is left in the cabinets and fridge, then how much money we have, and then I make the menu. I stick to the list unless certain things are on sale at the store that we can afford.’ (FG1)

The decision to plan was quite unique to the individual, as some participants indicated a need to plan while others argued that their purchases were always spontaneous. As one noted:

‘I’m not a planner when it comes to my meals. I am a very picky eater that’s why it took me a while to get used to eating vegetables, especially zucchini.’ (FG3)

Another noted:

‘I’m spontaneous. I never plan. I go to the store two times a week for something small. Usually something I forgot to grab at the pantry that week.’ (FG3)

Regardless of whether or not a user decided to plan ahead for shopping at the choice pantry, the need to be intentional about purchases was often highlighted as more significant to food pantry users than others not relying on pantries to meet their food needs.

Situational influences on motivation to select healthy foods

Apart from those individual factors influencing motivation to select particular food items at the choice pantry, participants also revealed a variety of factors that were situationally driven. It was evident, however, that while these factors were present across participants, the way in which the factor influenced motivation could be very different. One such factor was the variety of items available at the pantry on the day of shopping. The availability of specific items could vary quite dramatically from month to month, and participants indicated that their choice of what items to select was largely dictated by what specific items ‘looked good’ on the day of shopping. One participant pointed out how different pantries can be in the kinds of food they provide. The choice of what pantry to attend could dictate the kinds of foods taken home and consumed. The participant stated that while he has an interest in consuming some healthier items (like fruits and vegetables), his ability to obtain them was dictated by what the pantry makes available. He discussed:

‘I am tired of going there because they give out whatever they have, the same things each time, you have to wait forever, and you never get any fruits or vegetables, only expired meat. One time I got asparagus from another which I don’t like. And they gave out a recipe with a sauce, but I tried it anyways and it was good.’ (FG5)

Another participant pointed out how pleased she was with the selection at another pantry:

‘I go to two food pantries a month and I can pick out everything I want to eat because I picked it. The Mission always has a bunch of vegetables. I prefer to pick better foods that look good the day that I shop rather than just getting a sack full. A lot of times they put stuff in there that I don’t want, and I hate to throw food away.’ (FG1)

This comment also speaks to another assumption regarding the food insecure, namely the idea that being food insecure also entails that one’s preferences and tastes will be sacrificed in place of the consumption of any food made available.

The participants also discussed the ways in which the allocation of points and specific point values assigned to food items could dictate what items they selected. Albeit having less influence than others, participants did seem to make decisions relative to what certain items ‘cost’ at the pantry. Different from the selection of foods that would enable a participant to stretch one food item across multiple meals, participants would choose lesser-pointed items in the pantry that could be more costly in the retail setting. As one participant brought forward:

‘They think of both ways on that. I can’t afford this in the store, but I can go here and it only costs 2 points – they will get it that way. It varies based on the person. Typically, that’s how it usually works. They pick things that they are most likely unable to afford at the store.’ (FG5)

The participants pointed out, however, that the selection of point values for specific items could vary widely across pantries or even the same pantry across different distribution times. One participant discussed:

‘I like the lean turkey and turkey bacon they give out here but if I go to the one downtown, they make it worth almost half of the points that I have. I have to think about what I can get to feed my kids and usually I try to make my points last. I can’t afford to pick that kind of stuff down there.’ (FG4)

Similar to arguments regarding appropriate food pricing in retail settings, such a response entails that food pantry administrators should attend closely to the values they assign to items, especially those items of better nutritional value.

One the most widely discussed situational influences was that of place-related constraints. The participants noted that the time they have available to shop, transportation schedules and what they had available to help in transporting food items might dictate what items they chose at a particular pantry. An exchange by participants in FG4 shed light on these barriers.

‘I think transportation is a huge issue for a lot of people in Muncie.’

‘Yeah I ride the bus.’

‘It used to be once a month here, once a month at Union Missionary because we could walk or ride their bikes. It’s harder to get here. Riding the bus is hard because I don’t have anything to do with my boxes.’

‘I have to look at the bus line access. If I can’t find a bus close to the pantry, I can’t go period. Then even if I can go, I can only choose light things. No cans. I have to carry it all.’

In another group, one participant noted that the time of operation for the pantry made it difficult to choose items that needed refrigeration, like fresh produce. She discussed:

‘I love coming here, but they are only open in the afternoon. I always come right before I head to work on Thursdays, but I don’t have time to go home, and I get a ride with one of my co-workers. So, I have to pick things that will last in the car for my shift.’ (FG6)

Lastly, one of the livelier conversations across participants was in relation to how experiences of stigmatization and suspicion at the pantry could influence their willingness to be thoughtful about food items. Interestingly, there were no specific interview questions posed relative to these experiences. However, when asked about the quality of food at particular pantries or the policies that most needed updating, participants often shifted the conversation to reflect on their personal treatment while shopping. Some of these conversations were focused on negative experiences, while others involved praise for pantries and volunteers for their comfort and reassurance. These responses add to scholarship discussing the potential role that stigmatization can play in one’s choice to make use of emergency food assistance( 25 , 26 ). In one exchange, a participant began by noting:

‘Some are ashamed to go because of the label and stigma they receive from it. But I think if you’re in need you’re in need. That’s what pantries are for. But some people’s prides won’t let them. Or if they go, they are just in and out. They don’t take the time to really think about what they want or need or deserve. They are just in and out.’ (FG2)

In FG6, a similar exchange began, but the conversation tone quickly shifted to a negative experience shared by two of the participants.

‘Coming here, it helps. but I am embarrassed to go. We went to one a few days ago and the people there were not nice. Not the people at the church but the other people waiting.’

‘Yeah they were so rude. We told the people at the church.’

‘Yeah they have a rule about not being able to get on the property at 1:00. We got there at 1:30 and got yelled at by other food pantry people.’

‘The workers only worry about the inside, not the outside. They say we just have to deal with it. But by the time I do with the outside, when I get inside, I just don’t want to be there anymore. I just want to get my food as quick as I can and go home.’

Discussion

The findings of our focus group analysis involving food-insecure community members who make use of client choice pantries to meet their food needs indicated that the motivation to select food items at the choice pantry was individually and situationally driven, similar to retail environments. Just as moment-of-purchase and place-of-purchase factors affect the purchasing of food items in retail environments( 18 ), situational factors, such as food availability and the ‘price’ of food items in point values, impacted food selection at choice pantries. However, the stigmatization and suspicion experienced by those who visit pantries differ quite dramatically from the standard shopping experience. In terms of individual factors, experience and familiarity with food items and food taste preferences similarly influence the food selection of individuals in the retail setting( 19 ) and in choice pantries. However, while in retail settings the saliency and awareness of the healthfulness of food items has been shown to impact healthy food selection( 21 , 22 ), in the food pantry the ability to stretch foods is a unique challenge experienced by those facing significant barriers to the acquisition of food itself, apart from what is healthy.

It seems as though when the true cost of food is removed as a barrier in the choice environment, constraints to food selection emerge that point to the role of other factors in motivating food selection. For example, food preference, taste and familiarity seem to take an important role in dictating if a healthy food item will be selected among all other options, even if the point value for that item is higher than others. The participants often indicated that knowing how to prepare a healthy food item, particularly certain kinds of vegetables, was the factor that impacted whether or not they chose it, regardless of its point value or outright nutritional quality. The participants also indicated that the importance of familiarity stretched to retail settings as well. Such a finding speaks to the potential impact of teaching pantry clients that experimentation is okay. When item cost is removed as a barrier, the flexibility to choose new foods is at lesser risk than wasting a monetary purchase. Overall, choice pantries do seem to mimic retail settings more so than standard, box pantries, which may be why so many of the themes speaking to food selection were discussed in a consistent way across both settings. What was surprising, however, was that even in the choice pantry environment where food price is not a factor, many participants still relied on the same individual motivators behind food selection as in the retail setting. These included experience with food items, fit with existing routines and plans, and the ability of the item to stretch across multiple meals.

Our analysis was not without its limitations and, in that, additional research is necessary to expand upon our existing findings. Our sample of focus group participants was drawn from only one choice pantry in one community, leaving us with conclusions that may not be generalizable to other food pantry clients in other settings. Additional research should work to assess if our themes match those of individuals in other environments where choice pantries are common. Our sample was predominantly individuals who frequent pantries once monthly to supplement food they are able to purchase from low-cost grocers. Clients who do not rely on the food pantry to meet a majority of their food needs may have different premises underlying their decision making than those who rely on food assistance to meet most of their food needs. Drawing conclusions regarding the decision-making processes of only retail v. pantry clients may also lend to an overestimation of the similarities between spaces across those clients, as the use of food pantries only might indicate that a client lacks the ability to purchase retail items and thus would not possess an equitable reference frame for making comparisons. A more targeted understanding of the differences between retail shopping and choice pantry food selection could be offered by contrasting a sample of participants who engage in a majority of their shopping in the retail setting with a group who relies more heavily on food pantries.

The findings from our analysis entail some important implications for those who work to improve food pantry experiences for the food insecure, including those who work and volunteer in emergency food assistance locations as well as scholars who research food pantry environments. More attention needs to be paid towards creating environments in choice pantries that consider situational influences on food selection and encourage healthy food decisions. The situational element is likely what makes the pantry experience different from retail settings. Specifically, participants noted that the stigmatization experienced by those in pantry environments is unique to that setting. No one discussed negative judgement for shopping in retail settings, even considering some settings that feature low-cost food items. Much of the negativity experienced by the participants was afforded by those in volunteer and administrator roles in pantries who closely monitor shopping experiences. Such a finding speaks to a continued need to attend to the ways in which pantry clients are treated before and during their shopping. Training a volunteer workforce to be more considerate of the personal challenges experienced uniquely by each visitor seems paramount.

Additionally, we must also attend more closely to the motivations that impact food selection. Encouraging healthy food selection is any environment has proved difficult, and choice pantries have proved to be unique from other settings. Choice pantries would benefit from learning more about the psychosocial factors in their own pantries and adapting the environment and choices to the desires of their users, rather than adopting widely disseminated strategies that encourage healthy food choices without a consideration of their unique client perceptions. In some settings, this may entail being more thoughtful regarding the allocation of point values to certain food items, perhaps encouraging experimentation by placing more unique food items at lesser value. In others, it may be fitting to recognize the barriers pantry clients experience away from the actual shopping (transporting large amounts of food items on buses, for example) and encourage solutions that involve other community stakeholders.

Conclusion

Our analysis of focus group responses indicated that choice pantry clients may possess similar individual premises underlying the decision to select food items in the choice pantry space to those who select similar food items in retail settings. The findings above confirm that the class attitude–behaviour model established by Engel et al., which details that the premises driving retail food purchases can be applied similarly to the individual premises driving food decisions in choice pantry environments( 22 ). However, situational elements present for those making selections in the pantry space are often dramatically different from for those in retail settings, pointing to the importance of applying the model across different food selection environments. Additional application of the model to understand the premises underlying food selection in a broader sample of choice pantries is necessary to create a comprehensive picture of how healthy foods are selected. When understood, this information will be useful in creating targeted approaches to encourage healthy food choices in choice pantry settings.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the staff, volunteers and clients of the 10th Street Elementary School Food Pantry in Anderson, Indiana, as well as the contributions of student research assistants Kailey Adkins and Sara Kruszynski. Financial support: This work was supported by an internal grant from the Ball State University College of Health. Ball State University College of Health had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: C.L.J. conceptualized and supervised the study, obtained funding, provided overall programme management and led the writing of the manuscript. M.C.C. provided data management and contributed to analyses. Both authors contributed to manuscript preparation and approved the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ball State University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

References

- 1. Feeding Indiana’s Hungry, Indiana’s State Association of Food Banks (2017) Homepage. https://www.feedingindianashungry.org/ (accessed June 2018).

- 2. STATSIndiana (2015) Indiana Department of Education. http://www.stats.indiana.edu/topic/education.asp (accessed June 2018).

- 3. Coleman-Jenson A, Gregory C & Rabbit M (2014) Household food security in the United States in 2014. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/45425/53740_err194.pdf (accessed March 2019).

- 4. Seligman HK, Bindman AB & Vittinghoff E (2007) Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med 22, 1018–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berkowitz S, Seligman HK & Basu S (2017) Impact of food insecurity and SNAP participation on healthcare utilization and expenditures. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ukcpr_papers/103 (accessed June 2018).

- 6. Robaina KA & Martin KS (2013) Food insecurity, poor diet quality, and obesity among food pantry participants in Hartford, CT. J Nutr Educ Behav 45, 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daponte BO, Lewis LH, Sanders S et al. (1998) Food pantry use among low-income households in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. J Nutr Educ Behav 30, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dammann KW & Smith C (2009) Factors affecting low-income women’s food choices and the perceived impact of dietary intake and socioeconomic status on their health and weight. J Nutr Educ Behav 41, 242–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Indiana State Department of Health (2017) Food Assistance Programs (TEFAP) and (CSFP). https://www.in.gov/isdh/24779.htm (accessed October 2018).

- 10. Indianapolis Hunger Network (2018) Food Drop. http://www.indyfooddrop.org (accessed October 2018).

- 11. Handforth B & Hennick M (2013) A qualitative study of nutrition-based initiatives at selected food banks in the Feeding America network. J Acad Nutr Diet 113, 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwab L (2013) Food insecurity from the providers’ perspective. PhD Thesis, Miami University. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Remley NT, Kaiser ML & Osso T (2013) A case study of promoting nutrition and long-term food security through choice pantry development. J Hunger Environ Nutr 8, 324–336. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Block JP, Scribner RA & DeSalvo KB (2004). Fast food, race/ethnicity, and income. Am J Prev Med 27, 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Monsivais P & Drewnowski A (2007) The rising cost of low-energy-density foods. J Acad Nutr Diet 107, 2071–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leibtag ES & Kaufman PR (2003) Exploring Food Purchase Behavior of Low-Income Households: How Do They Economize? Agricultural Information Bulletin no. AIB-33711. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wiig K & Smith C (2014) The art of grocery shopping on a food stamp budget: factors influencing the food choices of low-income women as they try to make ends meet. Public Health Nutr 12, 1726–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shepherd R (editor) (1989) Factors influencing food preferences and choice. In Handbook of the Psychophysiology of Human Eating, pp. 3–24. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mowen JC (1993) Consumer Behavior, 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Engel JF, Blackwell RD & Miniard PW (1995) Consumer Behavior, 6th ed. Chicago, IL: Dryden Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gardial SF, Clemons DS, Woodruff RB et al. (1994) Comparing consumers’ recall of pre-purchase and post-purchase product evaluation experiences. J Consum Res 20, 548–560. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zeithaml VA (1988. ) Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J Market 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krueger RA (1994) Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hsieh HF & Shannon FE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15, 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Algert SJ, Reibel M & Renvall MJ (2006) Barriers to participation in the food stamp program among food pantry clients in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health 96, 807–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nooney LL, Giomo-James E, Kindle PA et al. (2013) Rural food pantry users’ stigma and safety net food programs. Contemp Rural Soc Work 5, 104–109. [Google Scholar]