Abstract

Objective:

Food environments may be contributing to the rapid increase in obesity occurring in most Latin American (LA) countries. The present study reviews literature from LA that (i) describes the food environment and policies targeting the food environment (FEP); and (ii) analytic studies that investigate associations between the FEP and dietary behaviours, overweight/obesity and obesity related chronic diseases. We focus on six dimensions of the FEP: food retail, provision, labelling, marketing, price and composition.

Design:

Systematic literature review. Three databases (Web of Science, SciELO, LILACS) were searched, from 1 January 1999 up to July 2017. Two authors independently selected the studies. A narrative synthesis was used to summarize, integrate and interpret findings.

Setting:

Studies conducted in LA countries.

Participants:

The search yielded 2695 articles of which eighty-four met inclusion criteria.

Results:

Most studies were descriptive and came from Brazil (61 %), followed by Mexico (18 %) and Guatemala (6 %). Studies were focused primarily on retail/provision (n 27), marketing (n 16) and labelling (n 15). Consistent associations between availability of fruit and vegetable markets and higher consumption of fruits and vegetables were found in cross-sectional studies. Health claims in food packaging were prevalent and mostly misleading. There was widespread use of marketing strategies for unhealthy foods aimed at children. Food prices were lower for processed relative to fresh foods. Some studies documented high sodium in industrially processed foods.

Conclusions:

Gaps in knowledge remain regarding policy evaluations, longitudinal food retail studies, impacts of food price on diet and effects of digital marketing on diet/health.

Keywords: Food environment, Latin America, Food retail, Food labelling, Food promotion, Food price, Systematic literature review

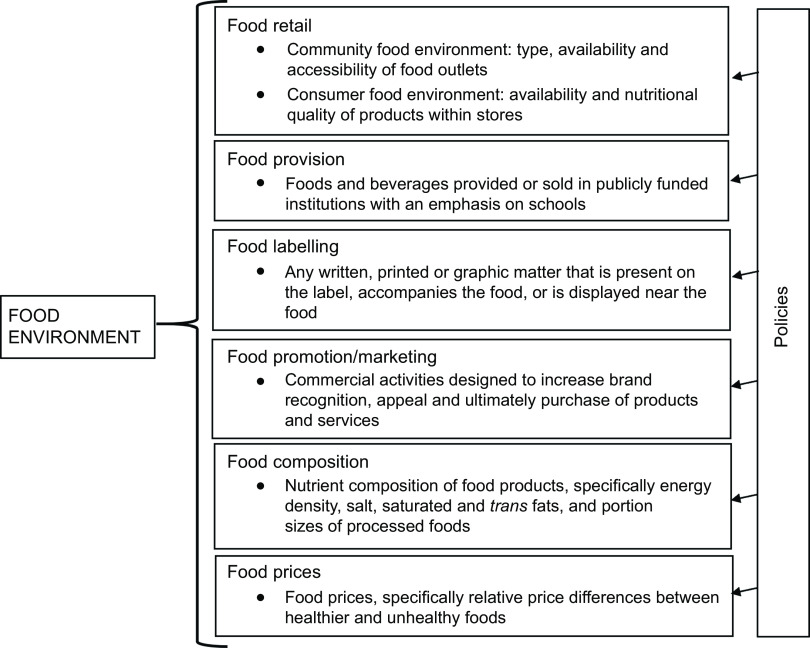

Food environments are the collective physical, economic and policy conditions that influence people’s food and beverage choices and nutritional status(1). They work as a bridge between the macro food system – food supply chains, processing, wholesale and logistics(2) – and people’s dietary choices. The International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support (INFORMAS) has provided a comprehensive framework to study the food environment, operationalizing it into seven distinct dimensions: food retail, provision, labelling, marketing/promotion, prices, composition, and trade and investment (Fig. 1)(1). These dimensions independently influence dietary behaviours, body weight and related health outcomes(3–9) and are amenable to intervention through health promotion policies. Examples of policies that modify the food environment include effective food labelling systems, regulation on the type and number of food outlets around schools, regulation of advertising of unhealthy foods to children, taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) and reformulation of food products(10).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual food environment framework adapted from INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support) for the current systematic review of food environments relevant to obesity and related chronic diseases in Latin America(1,18,20,67,125)

The Latin American region is comprised of thirty-three countries, home to 650 million people. Most Latin American countries are well underway in the nutrition transition(11) and face a large public health burden due to obesity and related chronic diseases(12). There is a growing body of literature on the food environment arising from Latin American countries which has not been summarized to date.

The objective of the current systematic review was to summarize the scientific literature on the food environment in Latin America. We focused on the following INFORMAS dimensions of the food environment: food retail, food provision, food labelling, food marketing, food price and food composition (Fig. 1). The INFORMAS framework is a fairly new framework (2013) and only in recent years have studies adopted it for monitoring the food environment(13,14). This framework is useful to examine and characterize the peer-reviewed literature on the food environment in Latin America because dimensions are clearly defined and strongly relate to policy options to prevent obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases. The current review includes: (i) descriptive studies of the food environment and policies targeting the food environment; and (ii) associations identified between one or more dimensions and dietary behaviours, BMI, obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases. We identify whether some of the work to date can be used to inform public health policy and areas where more research is needed.

Methods

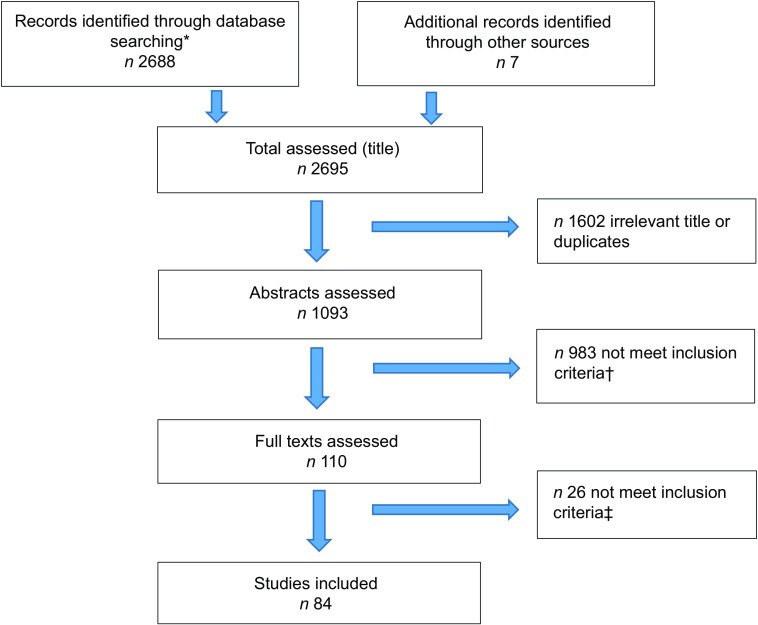

We followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for systematic reviews(15). We searched the literature published from 1 January 1999 up to July 2017 using Web of Science (which includes the indexes in PubMed), LILACS and SciELO. The search strategy and comprehensive list of search terms were developed with input from all members of the writing group (see Supplemental File S1 for keywords and example syntax). Our search strategy was broad in order to identify descriptive studies of the food environment and those which investigated the association between the food environment and a health outcome or policy. In brief, the search strategy was designed to include (diet-food AND spatial) OR food retail OR food composition OR food marketing OR food labelling OR food price AND Latin America. Keywords were translated into Portuguese and Spanish by native Portuguese/Spanish speakers and used for the SciELO and LILACS databases. After refining the search 2688 records were retrieved and the writing group identified seven more after consulting with food environment experts participating in a regional meeting in Antigua, Guatemala in May 2018. Titles were screened by the first author taking a conservative approach: only titles that were clearly unrelated to food, human nutrition or Latin America were excluded at this stage (1602 records). Two independent reviewers fluent in English and Spanish (C.P.-F., M.F.K.-L.) then screened the abstracts in English and Spanish. Abstracts in Portuguese were reviewed by two native Portuguese speakers (M.C.M., L.O.C.). In total, 1093 abstracts were reviewed. Upon disagreement, a third reviewer (A.H.A.) read the abstracts and decided whether to include them or not. Reasons for exclusion at each stage are presented in Fig. 2. One hundred and ten full texts were screened, and eighty-four studies met inclusion criteria. See Supplemental File S1 for the list of exclusion criteria and Supplemental File S2 for the full list of included studies.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of manuscript selection for the current systematic review of studies investigating the food environments relevant to obesity and related chronic diseases in Latin America. *Records were identified from the following databases: Web of Science (n 2265), Scielo (n 128) and LILACS (n 295). †The bases for exclusion of papers were as follows: context outside Latin America (n 80), not focused on food–diet–obesity–chronic diseases (n 351), no explicit link to food environment (n 339), not focused on empirical quantitative field data (n 119), consumer demand-side behaviours (n 54), home food environment (n 20), very small analytic sample (n 4), instrument or methodology development and/or validation (n 12), food environment as covariate (n 4). ‡The bases for exclusion of papers were as follows: not focused on food–diet–obesity–chronic diseases (n 3), no explicit link to food environment (n 1), not focused on empirical quantitative field data (n 7), consumer demand-side behaviours (n 4), trade and investment (n 11)

Using an Excel template, we extracted study information including: country; sample size; study setting; study design; data collection methods; INFORMAS dimension; key variables; main findings; whether findings were stratified by a variable of socio-economic position; funding sources; and language. For each INFORMAS dimension we identified key aspects of the studies using as a guideline the extraction fields used for INFORMAS systematic reviews(16–20). See Supplemental File S1 for details on extraction. The retail and provision dimensions were combined because there was much overlap between them (e.g. sale of foods in schools would classify in both food retail and provision).

Narrative synthesis was used to summarize, integrate and interpret findings. Narrative synthesis was chosen because our review included a wide range of research designs, types of data and measures, which could not be summarized using quantitative methods. Narrative synthesis involved two steps(21). First, we classified studies according to INFORMAS dimension, country, study design and other general characteristics as detailed in Tables 1 and 2, then conducted a preliminary synthesis of findings. Second, we further classified studies within each INFORMAS dimension (see sub-headings in Tables 3, 4 and 5 and Supplemental Tables S1 and S2).

Table 1.

General characteristics of studies included in the current systematic review of food environments relevant to obesity and related chronic diseases in Latin America

| Study characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies included (total) | 84 | 100·0 | |

| Country | Brazil | 51 | 61·4 |

| Mexico | 15 | 18·1 | |

| Guatemala | 5 | 6·0 | |

| Costa Rica | 3 | 3·6 | |

| Chile | 2 | 2·4 | |

| El Salvador | 1 | 1·2 | |

| Honduras | 1 | 1·2 | |

| Paraguay | 1 | 1·2 | |

| Uruguay | 1 | 1·2 | |

| Peru | 1 | 1·2 | |

| Multi-country (LATAM) | 3 | 3·6 | |

| Language | English | 64 | 77·1 |

| Portuguese | 12 | 14·5 | |

| Spanish | 8 | 9·6 | |

| Year of publication | 1999–2004 | 1 | 1·2 |

| 2005–2007 | 3 | 3·6 | |

| 2008–2010 | 12 | 14·5 | |

| 2011–2013 | 21 | 25·3 | |

| 2014–2017 | 47 | 56·6 | |

| Funding declared | Yes | 56 | 67·5 |

| No | 28 | 33·7 | |

| Epidemiological design* | Descriptive study | 60 | 72·3 |

| Cross-sectional | 15 | 18·1 | |

| Ecological | 3 | 3·6 | |

| Quasi-experimental | 3 | 3·6 | |

| Randomized controlled trial | 2 | 2·4 | |

| Cohort | 1 | 1·2 | |

None were case–control.

Table 2.

Specific characteristics of studies included in the current systematic review of food environments relevant to obesity and related chronic diseases in Latin America

| Study characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| INFORMAS dimension | Food provision/retail | 27 | 32·1 |

| Food promotion | 16 | 19·0 | |

| Food labelling | 15 | 17·9 | |

| Food price | 8 | 9·5 | |

| Composition & labelling | 6 | 7·1 | |

| Food composition | 6 | 7·1 | |

| Retail & price | 3 | 3·6 | |

| Composition & price | 2 | 2·4 | |

| Promotion & labelling | 1 | 1·2 | |

| Policy/environment | Environment | 58 | 69·0 |

| Policy | 26 | 31·0 | |

| Urbanicity | Urban | 65 | 77·4 |

| National | 16 | 19·0 | |

| Rural | 3 | 3·6 | |

| Study setting* | Consumer FE | 36 | 42·9 |

| Community FE | 17 | 20·2 | |

| Schools and surrounding areas | 14 | 16·7 | |

| Hours of TV programming | 9 | 10·7 | |

| Other | 8 | 9·5 | |

| FE assessment method† | Direct | 70 | 83·3 |

| Indirect | 7 | 8·3 | |

| Perceived | 7 | 8·3 | |

| Association between FE and health outcome | No (descriptive study) | 60 | 71·4 |

| Yes: diet/dietary components | 13 | 15·5 | |

| Yes: weight/BMI/obesity | 7 | 8·3 | |

| Yes: BMI & diet | 3 | 3·6 | |

| Yes: non-communicable diseases | 1 | 1·2 | |

| Results stratified by SEP | No | 65 | 77·4 |

| Yes | 19 | 22·6 |

INFORMAS, International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support; FE, food environment; SEP, socio-economic position; TV, television.

Study setting: consumer FE studies investigate characteristics of products sold in supermarkets and shops; community FE studies investigate density of food shops, distance to shops, perceived FE in neighbourhoods; school studies investigate foods sold in schools and surrounding areas; hours of TV programming studies investigate foods advertised on TV; other studies use household budget surveys.

FE assessment method: direct studies counted and classified e.g. number of shops or TV advertisements, or analysed food composition in a laboratory; indirect studies deduced something about the FE from other measures e.g. food prices through household expenditure data; perceived studies asked the study participants about their environment.

Table 3.

Retail studies* included in the current systematic review of food environments relevant to obesity and related chronic diseases in Latin America

| First author, year, reference | Study design, sample size | Population | Perception or objective measure | Adjustment variables | Healthier food environment | Unhealthier food environment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favourable health outcome (A) | Unfavourable health outcome (B) | Unfavourable health outcome (C) | |||||

| Summary of associations | [+] [+] [+] [+] [+] [+] [−] [−] [−] | [+/−] [−] [−] [−] [−] [+ /−] | [+] [+] [+] [+] [−] [−] [−] | ||||

| Azeredo, 2016(37) | Cross-sectional, n 109 104 |

9th grade children, PeNSE 2012; Brazil | Perception | Sociodemographic characteristics, regular intake of a specific unhealthy food (e.g. soft drinks), sale of the same unhealthy food in the cafeteria and in an alternative outlet, student consumption of food provided by the school food programme | [+/−] Somewhat mixed results for whole fruit or natural juice sold at school and reduction in SSB/UPF (snacks, sugar/sweets) |

[+] Soft drinks and fried salty snacks sold at school (school, public or private) assoc. with higher consumption of UPF and SSB (and bagged snacks assoc. with UPF at private but not public) [−] No association between sweets sold and higher consumption of sweets (school, public or private) except at mobile vendor within or outside school |

|

| Chor, 2016(31) | Cross-sectional, n 14 749 |

35–74-year-olds, ELSA 2008–2011; Brazil | Perception | Age, gender, education, income |

[+] Perceived availability of healthy food (neighbourhood) assoc. with higher F&V consumption |

||

| Duran, 2016(32) | Cross-sectional, n 1842 |

20–59-year-olds, VIGITEL 2011; Brazil | Objective (GIS) | Individual-level variables (age, sex, education and income) + neighbourhood-level income + community (proximity to supermarkets and fresh produce markets) and consumer FE variables |

[+] Mostly found healthier foods in neighbourhood (fresh produce market distance and density, and availability at other stores) assoc. with more F&V consumption [−] But did not find that lower prices for F&V assoc. with more F&V consumption |

[−] Did not find density of healthier foods in neighbourhood or lower prices for F&V assoc. with less SSB consumption |

[+] Results suggest high variety of SSB assoc. with more SSB consumption: odds of regular SSB consumption (≥5 d/week) with ≥11 types/flavours v. less: 1·14; 95 % CI 0·98, 1·32 |

| Barrera, 2016(30) | Cross-sectional, n 725 |

9–11-year-old children, 2012/2013; Mexico | Objective (GIS) | Age, sex, type of school (i.e. public or private) as a proxy of SES, and whether the school complies with federal food-in-school regulations |

[+] Number of stores combined (convenience, minimarkets, supermarkets), and also mobile food vendors around schools, assoc. with higher BMI |

||

| Jaime, 2011(23) | Ecological,n 2122 | Adults ≥18 years old, VIGITEL 2003 (only São Paulo); Brazil | Objective | Only area-level SES |

[+] Density of F&V markets (including F&V street markets and public food markets) assoc. with more F&V consumption. But all other results were null [−] Large supermarkets, local grocery stores, retail (neighbourhood) not assoc. with F&V consumption |

[−] Large supermarkets, grocery stores, total retail food stores (excluding fast-food restaurants) not assoc. with overweight/obesity, or SSB consumption |

[−] Fast-food restaurants not assoc. with overweight/obesity, or SSB consumption |

| Mendes, 2013(35) | Cross-sectional, n 3404 |

Adults ≥18 years old, VIGITEL 2008–2009; Brazil | Objective (GIS) | Unclear from paper | [−] Presence of F&V markets or supermarkets not assoc. with overweight/obesity |

||

| Motter, 2015(36) | Cross-sectional, n 2506 |

7–14-year-old children;Florianopolis City, Brazil | Perception | Sex, age, whether interviewee is head of household, education | [−] Distance to fresh produce stores, supermarkets or other small specialty stores (butcher or bakery) not assoc. with overweight or obesity |

[−] Distance to convenience store not assoc. with overweight or obesity |

|

| Pessoa, 2015(33) | Cross-sectional, n 5611 |

Adults ≥18 years old, VIGITEL 2010; Brazil | Objective | Age, sex, education, smoking, SSB intake, neighbourhood income, density of the other type of food store |

[+] Combined density of F&V stores and F&V open-air markets assoc. with higher F&V consumption |

[+] Combined density of bars, snack bars, food trucks assoc. with lower F&V consumption |

|

| Vedovato, 2015(34) | Cross-sectional, n 538 |

Mothers of young children; Santos City, Brazil | Perceived | SES and mother’s education |

[+] Perception of F&V availability in neighbourhood assoc. with higher household purchases of minimally processed foods [−] But overall perceived availability of healthy foods and greater variety of F&V not assoc. with household purchases of minimally processed foods |

[+/−] Perception of higher variety of F&V assoc. with lower acquisition of UPF, but perception of overall availability of ‘healthy food’ – or F&V in particular – not assoc. with household purchases of UPF |

|

| Zuccolotto, 2015(38) | Cross-sectional, n 282 |

Pregnant women >20 years old, Brazilian National Health Service data, São Paulo; Brazil | Perceived | Age, education, socio-economic class and adequacy of BMI by gestational age | [−] Distance to farmers’ market, distance to supermarket, perceived distance to buy F&V and F&V quality or variety not assoc. with F&V intake |

||

+, association in the expected direction (association in agreement with hypothesis); –, null association (none were in opposite direction to hypothesis); PeNSE, National Survey of School Health (Pesquisa Nacional de Saude do Escolar); ELSA, Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (Estudo Longitudinal de Saúde do Adulto); VIGITEL, Chronic Disease Risk Factor Telephonic Monitoring System (Sistema de Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico); GIS, geographic information system; FE, food environment; SES, socio-economic status; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage; assoc., associated; F&V, fruit and vegetable; UPF, ultra-processed food.

Only studies that presented a measure of association and a health outcome are included (some studies(22,42,126) were excluded for this reason). Three experimental studies and one cohort study which evaluated a multicomponent intervention (i.e. changes to the FE plus nutrition education(40,41,127,128)) were excluded.

Table 4.

Labelling studies (including labelling and composition)* included in the current systematic review of food environments relevant to obesity and related chronic diseases in Latin America

| Labelling aspect | Labelling aspect | Country | Sampling | Compliance with legislation?†,‡ | Main findings | First author, year, reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retail outlets | No. of products | Sample design | ||||||

| Presence of food labels and food label reliability | Presence of packaged food labels and claims | Costa Rica | 1 (supermarket) | 2910 | Inventory | N | 58 % of products had nutrition information. More than 100 different nutrition and health claims identified | Blanco-Metzler, 2011(48) |

| Overall | Chile | 1 (supermarket) | 1020 | Random sample | Y | 9·6 % of nutrition labelling had some type of error, the groups with most errors were packaged vegetables | Urquiaga, 2014(46) | |

| Brazil | NS | 153 | Convenience | N | Low reliability of food labels (label v. measured composition), e.g. under-report of saturated fat. Could be due to composition methods used | Lobanco, 2009(44) | ||

| Colombia, Brazil, Chile & Argentina | Food shops (n NS) | 40 per country | Convenience | Y | Labels in countries with mandatory labelling more likely to comply with CODEX. Brazil most comprehensive labels and more frequent, Colombia least. Health claims most common in Brazil and Argentina | Mayhew, 2015(51) | ||

| Sodium | Costa Rica | Supermarkets and bakeries | 183 | Sample | Y | High compliance of bread labels with regulation regarding Na content. Lower compliance for snacks; 43 % labels report less Na than measured | Montero-Campos, 2015(47) | |

| Brazil | NS | 17 | Convenience | Y | In 8 of 17 samples Na content higher compared with label. Most labels did not comply with legislation | Ribeiro, 2013(45) | ||

| Trans fat | Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 2327 | Inventory | N | 50 % of products may have trans fats according to ingredients, only a small proportion of products declared trans fats on label | Silveira, 2013(43) | |

| Brazil | Supermarkets (n NS) | 150 | Convenience | Y | 55 % of food labels did not comply with trans fat labelling legislation | Dias, 2009(49) | ||

| Presence of restaurant food labels | Brazil | N/A | 114 (restaurants) | Stratified random sample | N | 25 % of restaurants provided nutritional information. More common in fast-food chains than full-service restaurants | Maestro, 2008(50) | |

| Nutrient/health food claims and other categories | Claims & composition | Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 3449 | Inventory | N | Food products with nutrition claims have higher median Na contents than the corresponding conventional products | Nishida, 2016(54) |

| Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 535 | Inventory | N | Foods with nutrient claims less healthy than those without according to NOVA and similar according to Ofcom | Rodrigues, 2017(52) | ||

| Claims & marketing to children | Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 5620 | Inventory | Y | 9·5 % of products targeted children (n 535), products with nutrient claims were less healthy than or similar to those without | Rodrigues, 2016(53) | |

| Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 535 | Inventory | Y | 88 % of foods targeting children were ultra-processed, 47 % had nutrient claim mostly about higher quantity of vitamins and minerals | Zucchi, 2016(55) | ||

| Nutrient adequacy | Sodium & serving size | Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 2945 | Inventory | Y | 14 % of foods did not comply with serving sizes, 37 % had Na ≥ 5 mg/g (considered high) | Kraemer, 2016(56) |

| Sodium | Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 1416 | Inventory | N | 58·8 % classified as high Na content, highest content in sauces, seasonings, broths, soups and prepared dishes | Martins, 2015(59) | |

| Sodium, fat, fibre | Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 100 | Convenience | N | Labelling using traffic light criteria, 2/3 of products would be red for fibre and Na and 1/4 for fat | Longo-Silva, 2010(58) | |

| Saturated fat | Brazil | NS | 9 | Convenience | N | Large concentration of saturated fats found in products and n-6:n-3 above recommended levels | Gagliardi, 2009(57) | |

| Serving size | Serving size | Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 2072 | Inventory | Y | Differences identified between Food Guide for the Brazilian Population and labelling law with respect to recommended serving sizes | Kliemann, 2014(63) |

| Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 1953 | Convenience | Y | Declared serving size in most products complied with regulation. Only 4·1 % of foods had larger than recommended serving sizes | Kliemann, 2016(62) | ||

| Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 1071 | Convenience | N | In 88 % of food groups the average serving size consumed by the Brazilian population was larger than the declared serving size | Kraemer, 2015(60) | ||

| Brazil | 1 (supermarket) | 451 | Inventory | Y | 76 % of dairy products met the law’s requirements for serving size but varied widely within categories | Machado, 2016(61) | ||

NS, not stated; N/A, not applicable; N, no; Y, yes.

All studies included were descriptive.

Study evaluates compliance of food labels with law or regulation on food labels.

Brazilian labelling regulation: the following nutrients must be declared in packaged products per portion; energy, carbohydrates, protein, total fat, saturated fat, trans fat and sodium. Additionally, if a nutrition claim is present in the label, nutrition information must report the quantity of the nutrient the nutrition claim refers to(64). Centro American (Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Costa Rica) nutrition labelling regulation: the following nutrients must be declared in food products per portion or 100 g or 100 ml; total energy, total fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates, sodium and protein. If a nutrition claim is present, the nutrient in question must be included. Nutrition claims definitions for different nutrients included in regulation(65,66). Former Chilean labelling law required nutrition facts table(129).

Table 5.

Promotion studies* included in the current systematic review of food environments relevant to obesity and related chronic diseases in Latin America

| Media platform | Country | No. of ads/products | Length of time recorded/other | Promotion element(s) identified† | System for defining healthy/ unhealthy | Monitoring of codes/laws | Key findings | First author, year, reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV | Brazil | 1618 (TV ads) | 162 h/6 channels | Prom char, Health claims, Offers, Appeal | FB | Y | 5·6 % of ads were for food. Some categories fully complied with law, others did not | Britto, 2016(69) |

| Brazil | 4127 (TV ads) | h NS/3 channels | FB | N | 11 % of TV ads in Brazil for food (lowest of all countries studied). 2 food ads/h per channel. 55 % of food ads for ultra-processed nutrient-poor foods | Kelly, 2010(70) | ||

| Chile | 83 (food TV ads) | 350 h/5 channels | Appeal | NP | N | 56 % of food ads targeted to children. 79 % of advertised foods considered not healthy | Castillo-Lancellotti, 2010(71) | |

| Mexico | 9178 (TV ads) | 336 h/10 channels | Health claims, Appeal | NP | N | 17 % of all ads related to food. Ads shown during programming targeted to children longer, and showed less healthy products | Perez-Salgado, 2010(72) | |

| Mexico | 8299 (TV ads) | 235 h/5 channels | Prom char, Appeal | FB | N | 22 % of ads food related and 50 % targeted children. Of those, 64 % were for energy-dense food products | Ramirez-Ley, 2009(73) | |

| Brazil | 2732 (TV ads) | 132 h/4 channels | Prom char, Health claims, Offers, Appeal | FB | N | Ultra-processed foods accounted for majority of food ads | Maia, 2017(74) | |

| Mexico | 2544 (TV ads) | 600 h/4 channels | Appeal | NP | N | 20 % of all ads for foods and beverages. 64 % of foods advertised did not comply with Mexican nutrition standards for foods that can be advertised to children. International standards are stricter | Patino, 2016(75) | |

| Honduras | 2272 (TV ads) | 80 h/4 channels | Prom char, Appeal | FB | N | 17 % were food or beverage ads. 70 % were for unhealthy foods or beverages and 30 % for healthy ones. Most ads for unhealthy foods on cable network targeted children | Gunderson, 2014(76) | |

| Brazil | 3972 (TV ads) | 432 h/3 channels | Appeal | FB | N | 27·4 % were food or beverage ads. 57·8 % were for foods in fats, sugar and sweets group of healthy eating pyramid, 21 % bakery products, 0 for fruits and vegetables. More weekday than weekend ads | Almeida, 2002(77) | |

| Food packages | Guatemala | 106 (cereal boxes) | 1 supermarket | Health claims, Appeal | NP | N | Cereals marketed at children had worse nutrition profile. Half of cereals had child-oriented marketing | Soo, 2016(79) |

| Guatemala | 106 (‘child oriented’ snacks) | 55 shops around 4 schools | Prom char, Offers, Appeal | NP | N | Most common marketing technique was promotional characters (92·5 % of packages) then premium offers (34 % of packages). 97 % of child-oriented snacks classified as ‘less healthy’ | Chacon, 2013(80) | |

| Uruguay | 180 (products) | 2 supermarkets | Prom char, Health claims, Appeal | NP | N | Common category was candy and chocolates, followed by cookies and pastries, dairy products and breakfast cereals. Common strategies were the inclusion of cartoon characters, bright colours, childish lettering | Gimenez, 2017(84) | |

| Fast-food combo meals | Guatemala | 116 (combo meals) | 6 fast-food chain restaurants | Prom char, Offers, Appeal, Price, Time to delivery | NP | N | Nutrition information available in 2 out of 6 restaurants. All combo meals classified as ‘less healthy’. Marketing strategies include licenced characters, certain words and health claims | Mazariegos, 2016(81) |

| Store ads e.g. posters | Guatemala | 321 (food ads) | 55 shops around 2 schools | Prom char, Offers, Appeal | N/A (selected packaged snack foods only) | N | Snack food ads very prevalent around schools. More child-oriented ads in stores that were closer (<170 m) to schools compared with those further away | Chacon, 2015(78) |

| Billboards & wall ads | El Salvador | 100 (ads) | 6 rural villages, roads and urban area | Prom char, Health claims, Offers, Appeal | N/A (did not classify) | N | In urban areas most ads for fast-food restaurant chains. In rural areas most ads for beverages followed by snack. Themes identified were Cheap Price, Fast, Large and Modern. Strategies employed included repetition, placement, redefining foods and meals | Amanzadeh, 2015(82) |

| Leaflets, posters | Brazil | 220 (ads) | 24 shops | Health claims | N/A (all formula milk) | Y | All of the foods analysed violated at least one of the 5 clauses of the law | Pagnoncelli, 2009(83) |

Ad, advertisement; TV, television; NS, not stated; FB, food based; NP, nutrient profiling; N/A, not applicable; Y, yes; N, no.

All studies included were descriptive. One intervention study on social marketing of water in schools(68) was excluded.

Prom char, promotional characters (e.g. cartoon figures or celebrities) on ads or packages; health claims, statement about a relationship between food and health (e.g. high source of fibre or plant sterols help lower cholesterol); offers, premium offers (e.g. two-for-one, extra product for the same price); appeal, product design, use of colour and fonts appeals to the target population group.

For descriptive studies, we looked for consistency of findings by INFORMAS domain. In analytic studies, we looked for consistency in the direction and strength of associations. Our summary of analytic studies was limited to the food retail dimension because other dimensions had too few analytic studies to attempt summarizing associations. We evaluated the direction and strength of each association and classified according to whether the association was in the expected direction (i.e. in agreement with hypothesis), null or in an unexpected direction (see Supplemental File S1 for details).

Results

Over 60 % of the eighty-four eligible studies were conducted in Brazil, followed by Mexico (18 %) and Guatemala (6 %). Other countries in Latin America contributed between one and three papers to the review (Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. S1). The number of papers published on this topic has increased gradually over time; more than half (n 47) of the studies identified were published between 2014 and 2017. Most studies (77·4 %) focused on urban areas (Table 2). Seventy-one per cent of included studies were descriptive. Seventy-five per cent of association studies (eighteen out of twenty-four) utilized a cross-sectional or ecological design to study associations between the food environment and health or nutrition outcomes/behaviours (Tables 1 and 2). Out of the twenty-four association studies, sixteen investigated the retail food environment.

In terms of INFORMAS dimensions, food provision/retail was the dominant topic (32 %) followed by promotion (19 %), labelling (18 %) and composition (14 %). Price was the least explored (10 %). Forty-three per cent of studies investigated the consumer food environment, 20 % the community food environment and a further 17 % the school food environment. Most studies (67 %) collected primary data. The following sections present more detail on the design and results of studies within each food environment dimension.

Food retail/provision

Twenty-seven studies related to the food retail/provision dimension. Descriptive studies of the community food environment mainly investigated the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods by area-level socio-economic position and consistently showed higher availability of healthy foods in more affluent neighbourhoods. Results were fairly consistent across diverse contexts in Brazil (three cities: São Paulo, Florianopolis and Belo Horizonte) and Mexico (four cities: Mazatlán, Guadalajara, Mexico City and Puerto Vallarta)(22–27). There were mixed results regarding the availability of unhealthy foods in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Relative to more advantaged neighbourhoods, higher availability of unhealthy foods was found in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods in four Mexican cities (as listed above) and in one Brazilian city (São Paulo)(22–25), but two other studies in Brazil found fewer food stores (both healthy and unhealthy) in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Belo Horizonte and Florianopolis)(26,27). The descriptive studies of the consumer food environment focused on evaluating and classifying food stores as healthy or unhealthy according to types of foods found in the stores. As can be seen in Supplemental Table S1, consumer food environment studies used a mix of instruments to evaluate food stores. Several studies adapted and validated the Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS-S)(28,29) while others used locally developed and validated instruments, for example the auditing tool for markets, supermarkets and grocery stores (ESAO)(22).

Table 3 shows results for the analytic, observational food retail studies with a health or nutrition outcome/behaviour (n 10). All but one study(30) were carried out in Brazil and all studies had a cross-sectional design except for one which was ecological(22). There were consistent results regarding the association of healthier food environments, specifically those with a higher density of fruit and vegetable shops (measured or perceived), with higher consumption of fruits and vegetables (Table 3; column A)(23,31–34). There were mostly null findings for the association between healthier food environments and unfavourable health outcomes/behaviours such as overweight, obesity or SSB consumption (Table 3; column B)(23,32,34–36). However, a couple of studies found expected associations(34,37). Azeredo et al.(37) found selling fruit and natural fruit juice in private schools was associated with lower consumption of SSB and ultra-processed foods. Vedovato et al.(34) found that perceiving higher variety of fruits and vegetables (but not perceived availability of fruit and vegetables) was associated with lower purchases of ultra-processed foods. Finally, there were mixed findings regarding the association between unhealthy food environments and unfavourable health outcomes (Table 3; column C). Two studies found that the density of unhealthy food outlets (e.g. convenience stores and mobile food vendors) was associated with unfavourable health outcomes/behaviours (higher BMI and lower fruit and vegetable consumption)(30,33). On the other hand, Jaime et al.(23) found that the density of fast-food restaurants around individuals’ homes was not associated with overweight, obesity or SSB consumption and Motter et al.(36) found that the distance from home to convenience stores was not associated with overweight or obesity. Availability (density) and accessibility (distance) to supermarkets were not associated with nutrition outcomes/behaviours in Brazilian studies(23,35,38). Finally, regarding analytic retail food environment studies, there were three small, local experimental studies included (data not shown), which found that intervening on the food environment (i.e. cart offering fruits and vegetables in a neighbourhood(39) and changes to school food(40,41)) were associated with higher consumption of fruits and vegetables and a decline in energy intake.

Overall, results on the retail food environment were mostly limited to urban areas of Brazil. There was limited evidence for Mexico and virtually no studies published on the retail food environment for other Latin American countries with the exception of Paraguay that had one study that investigated the food environment in one low-income urban neighbourhood(42). Measurement of food availability, i.e. density of different shop types at neighbourhood level, was consistent across studies (Supplemental Table S2). However, neighbourhood definitions varied considerably. Four studies used administrative units (e.g. census tract as proxy for neighbourhood), while seven used different sized buffers around schools, homes or health facilities to define the local neighbourhood. One study used a qualitative description of neighbourhood (i.e. area around where you live) and three studies did not define neighbourhood (Supplemental Table S2). Availability (density of stores) was more frequently measured than accessibility (distance to stores). Only one study objectively measured distance using a geographic information system and found that living closer to supermarkets and fresh produce markets was associated with higher consumption of fruits and vegetables(32). Perception measures of distance to shops were not associated with nutrition or health outcomes/behaviours in two studies(36,38).

Food labelling

Nineteen out of twenty-one studies in this dimension (labelling, and composition and labelling together) were carried out in Brazil (Table 4). All food labelling studies were descriptive. In most studies, processed or packaged products from one supermarket were either selected for a sample (n 3 random; n 8 convenience) or inventoried (n 10). Studies ranged considerably in size from 100 to 5620 products. The most common themes studied were the presence of food labels and whether labels correctly reflected the nutrient composition of products(43–51), the nutrition quality of products with or without health or nutrition claims(52–55), nutrient adequacy(56–59) and serving size(60–63). An overarching theme was to evaluate compliance of food labelling with current legislation on these aspects. Labelling regulations in Brazil, Chile and Costa Rica require a nutrition facts table with at least five nutrients (total fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates, protein and sodium) and total energy declared on the label(64–66). Nutrient claims are allowed and, if present, the nutrition facts table must include the nutrient mentioned in the claim. Nine studies evaluated the presence of food labels and their reliability. Of them, three studies analysed labelling across all types of food in Chile, Brazil, Colombia and Argentina, finding that those with mandatory labelling were more likely to comply with the Codex Alimentarius Commission Guidelines(67); Brazil had the most comprehensive labels (6·4/7 nutrients required by CODEX and most readable), while Colombia had the least (4·6/7 nutrients required by CODEX)(51). In terms of reliability of labels, three Brazilian studies suggested inaccuracy in label contents compared with measured composition specifically for saturated fat, trans fat and sodium content(43–45) while one Costa Rican study reported accuracy in labels specifically for sodium content in breads(47). Four studies showed that the nutritional quality of foods with and without nutrition- and health-related claims was not different(52–55). Claims were used as a persuasive marketing technique for foods targeted to children, for example highlighting vitamin and mineral content in products that were high in sugar(52–55). Four studies from Brazil evaluated serving size reported in labels v. labelling law or the average serving size consumed by the population, finding that compliance with regulations was above 75 % of products but large differences were observed when compared with average serving sizes consumed by the population(60–63).

Food marketing/promotion

Table 5 shows the sixteen food promotion studies conducted in seven countries, their characteristics and findings. Except for one study(68), all were descriptive. Nine out of sixteen studies monitored food and beverage advertisements on television (TV) by recording TV programming, counting and classifying advertisements(69–77); four focused on food package design(78–81); and the rest evaluated advertisements on billboards and shops(78,82,83). The proportion of TV advertisements relating to foods and beverages ranged from 5·6 to 22 % depending on the channel and country (studies came from Brazil, Mexico and Honduras). Between 55 and 79 % of all food advertisements were for ultra-processed foods or foods considered unhealthy by the system used in the study(70,71,73,74,76,77). Advertisements shown during children’s TV programming tended to be longer and show more unhealthy products compared with those in adult programming(70,72,76). In Guatemala, breakfast cereals had worse nutrition profiles when cereal box messages were designed for children compared with when they were designed for adults(79); and stores that were nearer to schools were more likely to use child-oriented advertisements for unhealthy snack foods(78). Commonly used persuasive marketing techniques targeted to children included promotional characters, premium offers (e.g. competitions and toys), health or nutrition claims, and attractive package designs(79–81,84). The only analytic study in this dimension reported results from a social marketing intervention in four schools that aimed to increase water consumption. Water consumption was higher in intervention schools (v. control schools) but differences were not statistically significant(68).

Food price

Ten studies explored price (or price and composition of foods) of which six were from Brazil, three from Mexico and one from Guatemala. Seven out of ten studies were descriptive. Out of these, five focused on the price of food relative to its nutritional quality(85–89); with findings mostly consistent. Two studies suggested a higher relative price of processed and ultra-processed foods compared with healthier dry goods (e.g. beans, rice)(86); however, fresh foods (e.g. fruits, vegetables and meat) were more expensive than processed foods(86,88) and prepared foods made with processed ingredients were cheaper than similar items made from unprocessed ingredients(85). Furthermore, an analyses of price trends over 60 years found a relative increase in the prices of fresh fruits and vegetables and a relative decrease in the prices of sugars/sweets and processed foods(89).

The three analytic studies in this dimension were from Mexico and explored the effect of the Mexico SSB tax(90–92). They found the tax (excise tax of 1 peso ($US 0·05) per litre) was fully passed on to consumers and that it had the expected effect on sales: a reduction of between 6·2 and 8·7 %(90–92).

Food composition

Six studies reported on micro- or macronutrients in foods(93–98). Studies documented high sodium levels in fast foods(94) and found consumers did not reject processed foods after sodium was lowered via reformulation(97). One study found that meals offered at four workplace cafeterias in the city of São Paulo had higher fibre density, included more fruits and vegetables, and had a lower energy density than meals consumed at home or at restaurants. Restaurant meals had the highest content of fat and sugar(98). Three chemical analysis studies drew linkages between food supply and health conditions by reporting details on fatty acid and cholesterol content in foods(96); micronutrients in commonly consumed prepared foods(93); and compliance with Brazil’s regulatory limits on trans-fatty acids(95).

Discussion

We aimed to systematically review and summarize the literature about the food environment in Latin America that relates to risk factors for obesity and associated chronic diseases. We identified eighty-four studies analysing six out of seven dimensions proposed by INFORMAS(1): food retail/provision, labelling, promotion, price and composition. The most studied areas were food retail/provision followed by promotion and labelling. Cross-sectional results consistently found associations between healthy food retail environments and better diet; and descriptive studies consistently reported a high prevalence of health claims and marketing strategies that aimed to promote unhealthy products to children. Notable gaps in research were in longitudinal studies and analytic studies more generally along all dimensions of the food environment.

The current review consistently found a positive association between the availability of healthy foods or healthy food outlets (such as specialty fruit and vegetable shops and markets) and better diet quality; these studies were cross-sectional. Although more robust study designs are needed to confirm this association (i.e. longitudinal studies), these findings could potentially represent an opportunity for health promotion. Policies that support the continued presence of specialty fruit and vegetable shops and markets may support dietary quality. The retail food environment in Latin America is similar to North America and Europe in that there is a strong presence and growth of large supermarket chains and convenience stores at the expense of traditional retail channels such as local markets(99). However, in contrast to more developed countries, the traditional non-chain channels remain an important source of food in Latin America(2,32,36).

Studies investigating the food environment in developed countries tend to focus on fast-food restaurants and convenience stores but rarely explore the effect of healthy food shops other than supermarkets(4). Consistent with findings from systematic reviews from the USA, our findings were inconclusive on whether convenience stores and fast-food restaurants are associated with low quality diet or BMI in Latin America(4,100). Further, there was no evidence that density of supermarkets was associated with weight (overweight or obesity)(101). In Latin America, store type alone may be a poor indicator for healthfulness(3) given that there is great heterogeneity within categories such as supermarkets, grocery stores or even fast-food restaurants.

Food marketing studies included in the current review consistently found that regardless of country or TV channel, unhealthy food products were more likely to be advertised than healthy food products. Further, marketing of unhealthy products to children via advertisements in children’s TV programmes, food packages and stores near to schools, using a series of persuasive marketing techniques, was common practice in the countries studied. These findings are salient since there is a large body of literature that has demonstrated associations between aggressive food marketing and food preferences, especially among children(9,102). The channels and strategies used in Latin America are very similar to those in developed countries (i.e. TV, food package design, use of promotional characters, premium offers and heath claims). For example, widely used licensed characters are associated with taste preferences and food selection(103) and exposure to TV food advertisements is associated with food intake in children(104). Health claims are often used to market unhealthy food to mothers and as the current review has found, foods with nutrition- or health-related claims are often less healthy than those without them. Ten of the sixteen promotion studies included in our review were carried out after the adoption of the WHO’s Resolution WHA63.14 that aims to restrict the marketing of unhealthy food products to children and adolescents(105). This resolution was accompanied by a set of twelve recommendations for national governments(105,106). Our findings suggest that governments in the region have not taken the necessary actions to protect children from the harmful impact of unhealthy food marketing and that voluntary codes adopted by the food industry have not been effective.

Brazil was the first country in the region to introduce mandatory labelling in 2001(107). Other Mercosur countries (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay and Uruguay) followed suit with slightly different labelling requirements(107,108). Studies identified in the current systematic review show that when food labelling is mandatory, food products are more likely to have labels and comply with the basic Codex Alimentarius Commission guidelines(51,67,107). However, in some contexts, compliance with labelling laws was low or mediocre (in Brazil, studies reported less than half of products complying on some aspect of the label(45,49)). Further, even when compliance is high(10,46), the impact of labels on food choices depends on the design and interpretability of the label(46,109,110). In order to have a larger impact on food choice, some countries have converted traditional nutrition facts tables into graphical nutrition labels that may be better understood(10,111). In the future it will be crucial to monitor compliance with labelling regulations, consumer understanding of the labels and their effect on food choices.

We identified five key areas of opportunity where more research is warranted to better inform public health policy in the region. The first is to carry out more policy evaluations. Policy evaluations were largely absent from the literature, with the exception of evaluations of the soda tax in Mexico(90–92). Upcoming policy evaluations of the Chilean and Peruvian labelling laws, the regulation of school food in Mexico and the banning of trans fats in Argentina, for example, will enhance the literature. Further on this point, research should also monitor existing regulations so that governments and industry can be held accountable. The second area of opportunity identified is to strengthen the design of studies in the food retail dimension in order to improve causal inference; this will increase their relevance to policy makers. This could be done by designing cohort/panel studies and experiments rather than cross-sectional and ecological studies(112). The two experiments identified in the present review suggested that a change in the food environment had the expected effect on diet; however, both studies were small and at a local level(39,41). Causal inference can also be improved by better measurement of the neighbourhood food environment; for example, by using standardized instruments(28,113) to measure and characterize the consumer food environment. Further research on the retail food environment could also assess whether it is availability or accessibility through which healthy food outlets or traditional retail channels affect diet and ultimately health. Only one study assessed accessibility objectively (distance using a geographic information system)(32). A third area of opportunity for research is to better explore the role of food price. We found few studies investigating price and relative price of healthy v. unhealthy foods. Controversy exists on whether the price of healthy foods is a determinant of obesity and obesity inequalities in Latin American countries. While this has been demonstrated in the USA(114,115), the price of the traditional diet composed of staple foods and seasonal fruits and vegetables in Latin American countries may be cheaper than packaged ultra-processed foods. The fourth area of opportunity is regarding marketing and advertising on other media platforms not only TV and printed media. We do not yet know the reach of food marketing in digital media, i.e. through online video platforms, advergames, popular websites and apps, or its effects on food choices. Emerging evidence from other countries suggests that it has the same persuasive effect as marketing through traditional channels(116,117). Finally, a fifth area of opportunity for research is investigating the role of worksite food environments for health. Only one study on the worksite environment was found in the current literature review(98).

It is important to acknowledge that in order to conduct more and better research on the food environment in Latin America, funding for these types of studies is necessary. Research funding in Mexico and Brazil has traditionally supported basic science, infections and parasitic diseases, and health services(118,119). Health research funding priorities are not in line with the most pressing public health problems(118) which in these countries are poor diets, obesity and non-communicable diseases(12). Research funding for food environment studies must also be independent of conflict of interest. Evidence suggests that research funded by the food industry tends to be biased in favour of the industry(120,121). At minimum, the field would benefit from more transparency(122). In the current review of the literature, a third of studies did not declare the source of funding. Out of those that declared it, one was funded by the food industry(123).

Now we weigh the evidence thus far and comment on potential policy options. The research on the food labelling and food marketing dimensions in Latin America highlights the need for policy interventions in these two areas. Some policy options include stricter regulation of health and nutrition claims, graphical food labels such as the ones introduced by Chile and Ecuador, and mandatory (as opposed to industry-led) regulations on food marketing that comply with WHO recommendations(10,14). Further context-specific research should inform the finer details of marketing and labelling regulations (i.e. what to regulate: type of product, content of advertisements) and their effectiveness(70). Policy options in the food price dimension relate to food taxes and subsidies. The evidence for Mexico shows that taxes are viable and effective to reduce the consumption of SSB. Alternative pricing strategies such as subsidies were not studied and could be evaluated in future. In terms of food composition, reformulation as a policy option was understudied but could be promising(124). Finally, if associations between healthier food retail environments and diet are confirmed with more robust research designs, protecting and promoting local fruit and vegetable stores could be tested as a retail policy option. In addition to new policies it is of utmost importance to monitor existing codes and regulations around labelling, marketing, price/taxes and provision of foods in schools, among others, to ensure compliance and to determine whether the regulation is beneficial or not.

A limitation of the current review is that it does not include the trade and investment dimension because most studies in this area were reviews or qualitative studies that did not meet inclusion criteria. Trade and investment studies are crucial to understand recent changes in the food system and the food environment in Latin America. For example, in Mexico, the North American Free Trade Agreement led to a twenty-five-fold increase in foreign direct investment in the food processing industry in the 1990s, as well as exponential growth of multinational retailers(2,99). Another limitation relates to the representativeness of studies. Most studies were representative of neighbourhoods or cities but not entire countries or regions. There were very few multi-city or multi-country studies; these could have given a better picture of differences and similarities in the food environment within the region. Because most studies were descriptive, we did not conduct a detailed assessment of study rigour besides providing information about sample size and sampling design. Even among the analytic studies, we did not conduct meta-analyses due to high heterogeneity in epidemiological design, measures and food environment dimensions. Nevertheless, we were able to provide a narrative summary of the direction of associations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the literature on the food environment in Latin American countries has grown in size over the past few years, probably as a result of the rising obesity prevalence and increasing recognition of the food environment’s role. This body of literature had not been systematically summarized to date. Our literature review contributes to the literature in two ways. First, it highlights areas where evidence is consistent enough to inform policy making; for example, evidence on marketing of unhealthy food to children and inadequate use of health claims. Second, it identifies knowledge gaps which should be addressed by future research: evaluations of policies which aim to modify some aspect of the food environment; monitoring of existing regulations; improving causal inference of food retail studies; further investigating the relative cost of healthy v. unhealthy foods; exploring other marketing and advertising channels such as digital marketing; and investigating the role of worksite food environments.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge the support of SALURBAL investigators. For more information on SALURBAL and to see a full list of investigators, please visit https://drexel.edu/lac/salurbal/team/. Financial support: This work is part of the Salud Urbana en América Latina (SALURBAL)/Urban Health in Latin America project funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 205177/Z/16/Z). More information about the project can be found at www.lacurbanhealth.org. The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: A.H.A. and C.P.-F. designed the study. C.P.-F., A.H.A., M.F.K.-L., M.C.M. and L.O.C. ran searches in the different databases. All authors read a subset of abstracts to discuss inclusion and exclusion criteria. C.P.-F. wrote the article with key input from T.B.-G. and A.H.A. (data interpretation and analysis). All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final version and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019002891.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1.Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S et al. (2013) INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable Diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev 14, Suppl. 1, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popkin BM & Reardon T (2018) Obesity and the food system transformation in Latin America. Obes Rev 19, 1028–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV et al. (2012) The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place 18, 1172–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobb LK, Appel LJ, Franco M et al. (2015) The relationship of the local food environment with obesity: a systematic review of methods, study quality, and results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23, 1331–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Moore KAB, Auchincloss AH et al. (2017) Neighborhood physical environment and changes in body mass index: results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol 186, 1237–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cecchini M & Warin L (2016) Impact of food labelling systems on food choices and eating behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized studies. Obes Rev 17, 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kern DM, Auchincloss AH, Stehr MF et al. (2017) Neighborhood prices of healthier and unhealthier foods and associations with diet quality: evidence from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14, E1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern DM, Auchincloss AH, Stehr MF et al. (2018) Neighborhood price of healthier food relative to unhealthy food and its association with type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Prev Med 106, 122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadeghirad B, Duhaney T, Motaghipisheh S et al. (2016) Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes Rev 17, 945–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez-Escamilla R, Lutter CK, Rabadan-Diehl C et al. (2017) Prevention of childhood obesity and food policies in Latin America: from research to practice. Obes Rev 18, Suppl. 2, 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivera JA, Barquera S, Gonzalez-Cossio T et al. (2004) Nutrition transition in Mexico and in other Latin American countries. Nutr Rev 62, 7Pt 2, S149–S157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR et al. (2015) Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386, 2287–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieto C, Rodriguez E, Sanchez-Bazan K et al. (2019) The INFORMAS healthy food environment policy index (Food-EPI) in Mexico: an assessment of implementation gaps and priority recommendations. Obes Rev. Published online: 7 January 2019. doi: 10.1111/obr.12814. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kelly B, Vandevijvere S, Ng S et al. (2019) Global benchmarking of children’s exposure to television advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages across 22 countries. Obes Rev. Published online: 11 April 2019. doi: 10.1111/obr.12840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6, e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee A, Mhurchu CN, Sacks G et al. (2013) Monitoring the price and affordability of foods and diets globally. Obes Rev 14, Suppl. 1, 82–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ni Mhurchu C, Vandevijvere S, Waterlander W et al. (2013) Monitoring the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods and non-alcoholic beverages in community and consumer retail food environments globally. Obes Rev 14, Suppl. 1, 108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rayner M, Wood A, Lawrence M et al. (2013) Monitoring the health-related labelling of foods and non-alcoholic beverages in retail settings. Obes Rev 14, Suppl. 1, 70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neal B, Sacks G, Swinburn B et al. (2013) Monitoring the levels of important nutrients in the food supply. Obes Rev 14, Suppl. 1, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly B, King L, Baur L et al. (2013) Monitoring food and non-alcoholic beverage promotions to children. Obes Rev 14, Suppl. 1, 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A et al. (2006) Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. Lancaster: Lancaster University. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duran AC, Diez Roux AV, Latorre M et al. (2013) Neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics and differences in the availability of healthy food stores and restaurants in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Health Place 23, 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaime PC, Duran AC, Sarti FM et al. (2011) Investigating environmental determinants of diet, physical activity, and overweight among adults in Sao Paulo, Brazil. J Urban Health 88, 567–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bridle-Fitzpatrick S (2015) Food deserts or food swamps?: a mixed-methods study of local food environments in a Mexican city. Soc Sci Med 142, 202–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soltero EG, Ortiz Hernandez L, Jauregui E et al. (2017) Characterization of the school neighborhood food environment in three Mexican cities. Ecol Food Nutr 56, 139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Correa EN, Padez CMP, de Abreu AH et al. (2017) Geographic and socioeconomic distribution of food vendors: a case study of a municipality in the Southern Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 33, e00145015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pessoa MC, Mendes LL, Caiaffa WT et al. (2015) Availability of food stores and consumption of fruit, legumes and vegetables in a Brazilian urban area. Nutr Hosp 31, 1438–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE et al. (2007) Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS-S): development and evaluation. Am J Prev Med 32, 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martins PA, Cremm EC, Leite FH et al. (2013) Validation of an adapted version of the nutrition environment measurement tool for stores (NEMS-S) in an urban area of Brazil. J Nutr Educ Behav 45, 785–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrera LH, Rothenberg SJ, Barquera S et al. (2016) The toxic food environment around elementary schools and childhood obesity in Mexican cities. Am J Prev Med 51, 264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chor D, Cardoso LO, Nobre AA et al. (2016) Association between perceived neighbourhood characteristics, physical activity and diet quality: results of the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). BMC Public Health 16, 751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duran AC, de Almeida SL, Latorre M et al. (2016) The role of the local retail food environment in fruit, vegetable and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in Brazil. Public Health Nutr 19, 1093–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pessoa MC, Mendes LL, Gomes CS et al. (2015) Food environment and fruit and vegetable intake in an urban population: a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health 15, 1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vedovato GM, Trude ACB, Kharmats AY et al. (2015) Degree of food processing of household acquisition patterns in a Brazilian urban area is related to food buying preferences and perceived food environment. Appetite 87, 296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendes LL, Nogueira H, Padez C et al. (2013) Individual and environmental factors associated for overweight in urban population of Brazil. BMC Public Health 13, 988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motter AF, de Vasconcelos FDG, Correa EN et al. (2015) Retail food outlets and the association with overweight/obesity in schoolchildren from Florianopolis, Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 31, 620–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azeredo CM, de Rezende LFM, Canella DS et al. (2016) Food environments in schools and in the immediate vicinity are associated with unhealthy food consumption among Brazilian adolescents. Prev Med 88, 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuccolotto DCC, Barbieri P & Sartorelli DS (2015) Food environment and family support in relation to fruit and vegetable intake in pregnant women. Arch Latinoam Nutr 65, 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Constante Jaime P, Sarti Machado FM, Faria Westphal M et al. (2006) Impacto de una intervención basada en la comunidad, en el mayor consumo de frutas y vegetales en familias de bajos ingresos, Sao Paulo, Brasil. Rev Chil Nutr 33, 266–271. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Safdie M, Jennings-Aburto N, Levesque L et al. (2013) Impact of a school-based intervention program on obesity risk factors in Mexican children. Salud Publica Mex 55, Suppl. 3, S374–S387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alvirde-García U, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Gómez-Pérez FJ et al. (2013) Resultados de un programa comunitario de intervención en el estilo de vida en niños. Salud Publica Mex 55, 406–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gartin M (2012) Food deserts and nutritional risk in Paraguay. Am J Hum Biol 24, 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silveira BM, Gonzalez-Chica DA & Proenca RPD (2013) Reporting of trans-fat on labels of Brazilian food products. Public Health Nutr 16, 2146–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lobanco CM, Vedovato GM, Cano C et al. (2009) Reliability of food labels from products marketed in the city of Sao Paulo, Southeastern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica 43, 499–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ribeiro VF, Ribeiro MD, Vasconcelos MAD et al. (2013) Processed foods aimed at children and adolescents: sodium content, adequacy according to the dietary reference intakes and label compliance. Rev Nutr 26, 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Urquiaga I, Lamarca M, Jimenez P et al. (2014) Assessment of the reliability of food labeling in Chile. Rev Med Chil 142, 775–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montero-Campos MDL, Blanco-Metzler A & Chan VC (2015) Sodium in breads and snacks of high consumption in Costa Rica. Basal content and verification of nutrition labeling. Arch Latinoam Nutr 65, 36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blanco-Metzler A, Rosello-Araya M & Nunez-Rivas HP (2011) Basal state of the nutritional information declared in labels of foods products marketed in Costa Rica. Arch Latinoam Nutr 61, 87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dias JR & Goncalves E (2009) Consumption and analysis of nutritional label of foods with high content of trans fatty acids. Cienc Tecnol Alim 29, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maestro V & Salay E (2008) Nutritional and health information released to consumers by commercial fast food and full service restaurants. Cienc Tecnol Alim 28, 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mayhew AJ, Lock K, Kelishadi R et al. (2016) Nutrition labelling, marketing techniques, nutrition claims and health claims on chip and biscuit packages from sixteen countries. Public Health Nutr 19, 998–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodrigues VM, Rayner M, Fernandes AC et al. (2017) Nutritional quality of packaged foods targeted at children in Brazil: which ones should be eligible to bear nutrient claims? Int J Obes (Lond) 41, 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodrigues VM, Rayner M, Fernandes AC et al. (2016) Comparison of the nutritional content of products, with and without nutrient claims, targeted at children in Brazil. Br J Nutr 115, 2047–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishida W, Fernandes AC, Veiros MB et al. (2016) A comparison of sodium contents on nutrition information labels of foods with and without nutrition claims marketed in Brazil. Br Food J 118, 1594–1609. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zucchi ND & Fiates GMR (2016) Analysis of the presence of nutrient claims on labels of ultra-processed foods directed at children and of the perception of kids on such claims. Rev Nutr 29, 821–832. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kraemer MVD, de Oliveira RC, Gonzalez-Chica DA et al. (2016) Sodium content on processed foods for snacks. Public Health Nutr 19, 967–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gagliardi ACM, Mancini J & Santos RD (2009) Nutritional profile of foods with zero trans fatty acids claim. Rev Assoc Med Bras 55, 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Longo-Silva G, Toloni MHD & Taddei J (2010) Traffic light labeling: translating food labeling. Rev Nutr 23, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martins CA, de Sousa AA, Veiros MB et al. (2015) Sodium content and labelling of processed and ultra-processed food products marketed in Brazil. Public Health Nutr 18, 1206–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kraemer MVD, Machado PP, Kliemann N et al. (2015) The Brazilian population consumes larger serving sizes than those informed on labels. Br Food J 117, 719–730. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Machado PP, Kraemer MVD, Kliemann N et al. (2016) Serving sizes and energy values on the nutrition labels of regular and diet/light processed and ultra-processed dairy products sold in Brazil. Br Food J 118, 1579–1593. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kliemann N, Veiros MB, Gonzalez-Chica DA et al. (2016) Serving size on nutrition labeling for processed foods sold in Brazil: relationship to energy value. Rev Nutr 29, 741–750. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kliemann N, Veiros MB, Gonzalez-Chica DA et al. (2014) Reference serving sizes for the Brazilian population: an analysis of processed food labels. Rev Nutr 27, 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Agencia Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária – Anvisa (2003) Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada – RDC nº 360 de 22/12/2003. http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/legislacao#/visualizar/27327 (accessed May 2019).

- 65.Reglamento técnico Centroamericano (2012) RTCA 67.01.01.10 Etiquetado general de los alimentos previamente envasados. https://www.mineco.gob.gt/sites/default/files/rtca_de_etiquetado_general_de_alimentos.pdf (accessed May 2019).

- 66.Reglamento técnico Centroamericano (2012) RTCA 67.01.60:10: Etiquetado nutricional de productos alimenticios preenvasados para consumo humano para la población a partir de 3 años de edad. https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/files/COMIECO%202011%20Etiquetado%20Nutricional%20de%20Productos%20Alimenticios%20Preenvasados%20para%20Consumo%20Humano.pdf (accessed May 2019).

- 67.Codex Alimentarius Commission (2010) Codex General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods. CODEX STAN 1-1985. http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/list-standards/en/ (accessed August 2018).

- 68.Carriedo Á, Théodore FL, Bonvecchio A et al. (2013) Uso del mercadeo social para aumentar el consumo de agua en escolares de la Ciudad de México. Salud Publica Mex 55, 388–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Britto SDR, Viebig RF & Morimoto JM (2016) Analysis of food advertisements on cable television directed to children based on the food guide for the Brazilian population and current legislation. Rev Nutr 29, 721–729. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kelly B, Halford JCG, Boyland EJ et al. (2010) Television food advertising to children: a global perspective. Am J Public Health 100, 1730–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Castillo-Lancellotti C, Perez-Santiago O, Rivas-Castillo C et al. (2010) Analysis of food advertising aimed at children and adolescents in Chilean open channel television. Rev Esp Nutr Comun 16, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perez-Salgado D, Rivera-Marquez JA & Ortiz-Hernandez L (2010) Food advertising in Mexican television: are children more exposed? Salud Publica Mex 52, 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramirez-Ley K, De Lira-Garcia C, Souto-Gallardo MD et al. (2009) Food-related advertising geared toward Mexican children. J Public Health 31, 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maia EG, Costa BVD, Coelho FD et al. (2017) Analysis of TV food advertising in the context of recommendations by the Food Guide for the Brazilian Population. Cad Saude Publica 33, e00209115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rincón-Gallardo Patiño S, Tolentino-Mayo L, Flores Monterrubio EA et al. (2016) Nutritional quality of foods and non-alcoholic beverages advertised on Mexican television according to three nutrient profile models. BMC Public Health 16, 733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gunderson MD, Clements D & Neelon SEB (2014) Nutritional quality of foods marketed to children in Honduras. Appetite 73, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Almeida SD, Nascimento P & Quaioti TCB (2002) Amount and quality of food advertisement on Brazilian television. Rev Saude Publica 36, 353–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chacon V, Letona P, Villamor E et al. (2015) Snack food advertising in stores around public schools in Guatemala. Crit Public Health 25, 291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Soo J, Letona P, Chacon V et al. (2016) Nutritional quality and child-oriented marketing of breakfast cereals in Guatemala. Int J Obes (Lond) 40, 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chacon V, Letona P & Barnoya J (2013) Child-oriented marketing techniques in snack food packages in Guatemala. BMC Public Health 13, 967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mazariegos S, Chacon V, Cole A et al. (2016) Nutritional quality and marketing strategies of fast food children’s combo meals in Guatemala. BMC Obes 3, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amanzadeh B, Sokal-Gutierrez K & Barker JC (2015) An interpretive study of food, snack and beverage advertisements in rural and urban El Salvador. BMC Public Health 15, 521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pagnoncelli MGB, Batista AM, Da Silva MCM et al. (2009) Analysis of advertisements of infant food commercialized in the city of Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil. Braz J Pharmaceut Sci 45, 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gimenez A, de Saldamando L, Curutchet MR et al. (2017) Package design and nutritional profile of foods targeted at children in supermarkets in Montevideo, Uruguay. Cad Saude Publica 33, e00032116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pulz IS, Martins PA, Feldman C et al. (2017) Are campus food environments healthy? A novel perspective for qualitatively evaluating the nutritional quality of food sold at foodservice facilities at a Brazilian university. Perspect Public Health 137, 122–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Claro RM, Maia EG, Costa BVD et al. (2016) Food prices in Brazil: prefer cooking to ultra-processed foods. Cad Saude Publica 32, e00104715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]