Abstract

Objective

The purpose of the present meta-analysis was to evaluate the association between the inflammatory potential of diet, determined by the dietary inflammatory index (DII®) score, and depression.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science and EMBASE databases up to August 2018. All observational studies that examined the association of the DII score with depression/depressive symptoms were included.

Subjects

Four prospective cohorts and two cross-sectional studies enrolling a total of 49 584 subjects.

Results

Overall, individuals in the highest DII v. the lowest DII category had a 23 % higher risk of depression (risk ratio (RR)=1·23; 95 % CI 1·12, 1·35). When stratified by study design, the pooled RR was 1·25 (95 % CI 1·12, 1·40) for the prospective cohort studies and 1·16 (95 % CI 0·96, 1·41) for the cross-sectional studies. Gender-specific analysis showed that this association was observed in women (RR=1·25; 95 % CI 1·09, 1·42) but was not statistically significant in men (RR=1·15; 95 % CI 0·83, 1·59).

Conclusions

The meta-analysis suggests that pro-inflammatory diet estimated by a higher DII score is independently associated with an increased risk of depression, particularly in women. However, more well-designed studies are needed to evaluate whether an anti-inflammatory diet can reduce the risk of depression.

Keywords: Dietary inflammatory index, Diet, Depression, Meta-analysis

Depression is an important public health challenge worldwide(1). The estimated lifetime prevalence of depression is 3·3–21·4 % in the WHO’s World Mental Health Surveys(2). Depressive disorders not only impose a significant economic burden(3), but also account for substantial impairments in quality of life(4) and global disability(5). Therefore, identification of new preventive strategies is crucial.

Low-grade chronic inflammation has been linked to the pathophysiology of depression(6,7). Inflammatory cytokines can sometimes trigger depression in human subjects and are often associated with depression(8). Dietary patterns may have an influence on depression(9) partly through acting on inflammatory pathways(10). A decline in inflammation was associated with fewer depressive symptoms after a dietary intervention(11). A well-designed meta-analysis also concluded the antidepressant effects of anti-inflammatory agents(12). The dietary inflammation index (DII®) is a validated measure of the inflammatory potential of diet(13,14). This new dietary tool particularly focuses on the inflammatory potential of the overall diet. Lower DII score indicates a more anti-inflammatory diet and higher DII score reflects a more pro-inflammatory diet. There has been an increasing interest in investigating the association of lower DII score with depression. However, results from these available studies(15–21) are not consistent.

To our knowledge, there is currently no previous meta-analysis to evaluate the association between DII score and depression. Therefore, purpose of the present meta-analysis was to summarize the evidence on the association between the inflammatory potential of diet estimated by the DII score and depression.

Methods

Data source and searches

The MOOSE (Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were utilized for the current study(22). A computerized search strategy was utilized using PubMed, Web of Science and EMBASE databases up to August 2018. Search keywords included (‘dietary inflammatory index’ OR ‘anti-inflammatory diet’ OR ‘pro-inflammatory diet’ OR ‘inflammatory potential of diet’ OR ‘dietary pattern’) AND (‘depression’ OR ‘depressive symptoms’). References of retrieved articles were manually searched to identify any additional study.

Study selection

Included studies had to satisfy the following inclusion criteria: (i) observational study (cohort, case–control or cross-sectional design); (ii) inflammatory potential of the diet estimated by DII score as the exposure; (iii) incident depression/depressive symptoms as the outcome measure; and (iv) provide the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio or OR and CI of depression/depressive symptoms for the highest DII score (pro-inflammatory diet) v. the lowest DII score (anti-inflammatory diet). Studies were excluded if they: (i) failed to provide multivariable-adjusted risk estimates of depression; and (ii) had recurrence of depressive symptoms as the outcome. For multiple publications from the same participants, we selected the studies with the largest sample size.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction and quality assessment were conducted from the included studies by two independent authors. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or consultation with a third author.

The following information was collected from each included study: surname of the first author, year of publication, geographic region, study design, number of participants, proportion of women, mean age or age range of the participants at baseline, diagnosis of depression, DII measure, DII score comparison, most fully multivariable-adjusted risk estimate and length of follow-up for cohort studies. The methodological quality of the included studies was checked using the twenty-two-item STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) score(23). A study achieving a higher score represented the better methodological quality.

Statistical analyses

Meta-analysis was performed using the statistical software package Stata® version 12.0. To evaluate the relationship between the DII score and depression, the summary risk estimate was pooled for the highest v. the lowest category of DII score. Heterogeneity across studies was examined using the Cochrane Q test and I2 statistic. Statistical heterogeneity was set at P<0·1 for the Cochrane Q test or I2 statistic>50 %. A random-effects model was applied when pooled analysis resulted in statistical heterogeneity, or a fixed-effects model was used otherwise. Subgroup analyses were performed by study design and gender. Publication bias was examined by Begg’s rank correlation(24) and Egger’s linear regression test(25). A sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the robustness of the overall risk estimate by removing each single study in each turn.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

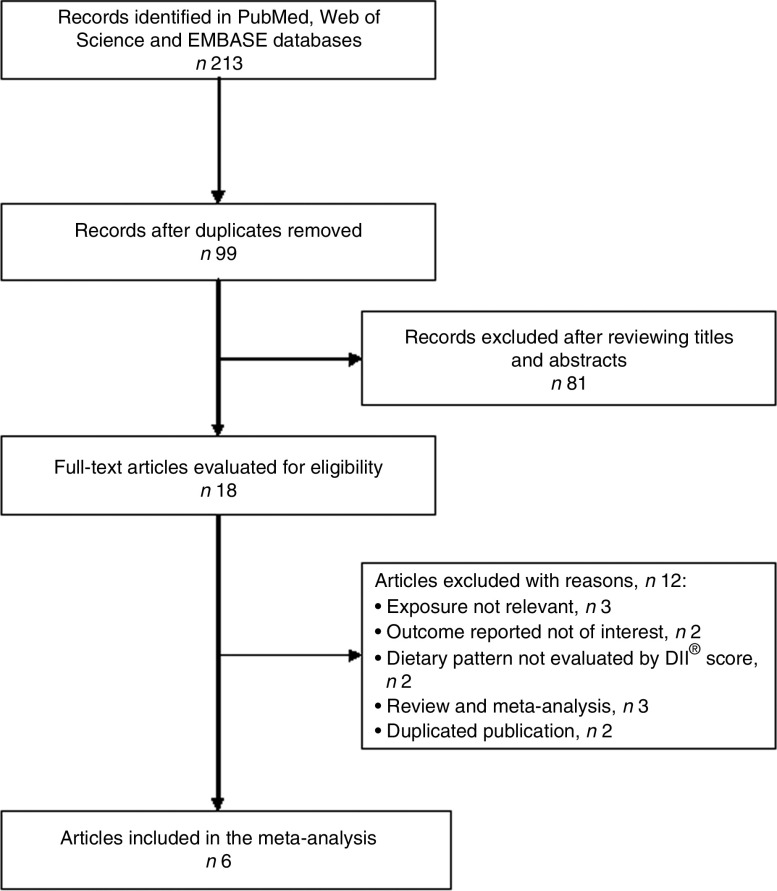

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the study selection process. Overall, a total of six studies(16,17,19–21,26) met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the included studies. Of six studies, four(16,17,19,26) used a prospective cohort design and two(20,21) were cross-sectional studies. All included studies were published between 2014 and 2017. These studies were conducted in the USA(21,26), Spain(16), France(19), Ireland(20) and Australia(17). The sample size ranged from 2047 to 18 875, with a total number of 49 584 individuals. The length of follow-up of the prospective cohort studies ranged from 8·0 to 12·6 years. The DII score was estimated by validated FFQ or dietary records. Depressive symptoms were evaluated by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) or self-reported antidepressant use. The quality assessment based on the STROBE score showed that the prospective cohort studies were grouped as high quality, whereas the cross-sectional studies were classified as moderate quality (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process for current meta-analysis on the association between the inflammatory potential of diet and depression

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the current meta-analysis of the association between the inflammatory potential of diet, determined by dietary inflammatory index (DII®) score, and depression

| Study | Country | Study design | Sample size (n) | Female (%) | Mean age (years) | Diagnosis of depression | DII® measure | DII® score comparison | Depression events (n) | HR or OR | 95 % CI | Adjustment for covariates | Follow-up (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sánchez-Villegas et al. (2015)(16) | Spain | Prospective cohort | 15 093 | 58·7 | 38·3 (sd 12·1) | Self-reported physician- provided diagnosis | Twenty-eight-item FFQ | Quintile 5 v. 1; >0·66 v. <−3·16 (median) | Cases: 1051 | 1·37 | 1·09, 1·73 | Age, sex, BMI, smoking, PA, vitamin supplements, TEI, presence of CVD, DM, hypertension or dyslipidaemia | 8·5 |

| Shivappa et al. (2017)(17) | Australia | Prospective cohort | 6438 | 100·0 | 52 (sd 1·4) | CES-D≥10 | 101-item FFQ | Quartile 4 v. 1; >2·88 v. ≤−0·88 (median) | Cases: 1156 | 1·23 | 1·05, 1·45 | TEI, highest qualification completed, marital status, menopause, night sweats, major personal illness or injury, lifestyle factors, smoking, PA, BMI, depression diagnosis or treatment | 12 |

| Adjibade et al. (2017)(19) | France | Prospective cohort | 3523 | 42·3 | 49·5 (sd 6·2) | CES-D≥23 (W) CES-D≥17 (M) | 24 h dietary records | Quartile 4 v. 1; >1·77 v. <−0·76 | Cases: 172 | 1·07 0·72 2·32 | 0·66, 1·72 0·39, 1·33 (W) 1·01, 5·35 (M) | Age, sex, intervention group during the trial phase, education, energy intake, marital status, socio-professional status, number of 24 h dietary records, interval between two CES-D measures, smoking, PA, BMI | 12·6 |

| Phillips et al. (2017)(20) | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 2047 | 50·8 | 59·7 (sd 5·4) | CES-D > 16 | Forty-five-item FFQ | Tertile 3 v. 1 | Cases: NP | 1·36 2·23 0·78 | 0·83, 2·24 1·15, 4·36 (W) 0·36, 1·64 (M) | Age, BMI, PA, smoking, alcohol consumption, antidepressant use, history of depression | – |

| Wirth et al. (2017)(21) | USA | Cross-sectional | 18875 | 50·7 | 46·9 | PHQ-9≥10 | Food items in 24h dietary recalls | Quartile 4 v. 1; >1·99 v. <−0·84 | Cases: 1648 | 1·13 1·30 1·09 | 0·92, 1·39 1·00, 1·68 (W) 0·73, 1·63 (M) | Age, race, education, marital status, perceived health, current infection status, family history of smoking, smoking, past cancer diagnosis, arthritis, mean nightly sleep duration | – |

| Shivappa et al. (2018)(26) | USA | Prospective cohort | 3608 | 56·5 | 61·4 (sd 9·2) | CES-D≥16 | Twenty-four single food parameters from the FFQ | Quartile 4 v. 1 | Cases: 837 | 1·24 | 1·01, 1·53 | Age, sex, race, BMI, education, smoking habits, yearly income, PA, Charlson co-morbidity index, baseline CES-D, statins use, NSAID or cortisone use | 8 |

HR, hazard ratio; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; W, women; M, men; PHQ-9, nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire; NP, not provided; PA, physical activity; TEI, total energy intake; DM, diabetes mellitus; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

DII score and depression

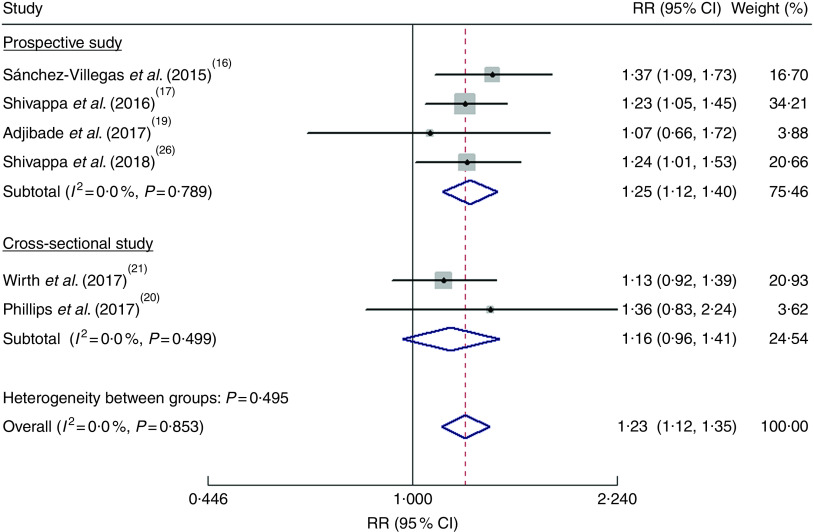

As shown in Fig. 2, the pooled RR was 1·23 (95 % CI 1·12, 1·35) for the highest v. the lowest DII score in a fixed-effects model, with no evidence of heterogeneity (I2=0·0 %, P=0·853). Sensitivity analysis indicated that no single study affected the pooled risk estimate significantly. When stratified by study design, the pooled RR was 1·25 (95 % CI 1·12, 1·40) for the prospective cohort studies(16,17,19,26) and 1·16 (95 % CI 0·96, 1·41) for the cross-sectional studies(20,21). Publication bias was not found according to Begg’s test (P=0·452) and Egger’s test (P=0·994).

Fig. 2.

(colour online) Forest plots showing the pooled risk ratio (RR) of depression for the highest v. the lowest category of dietary inflammatory index (DII®) score according to study design. The study-specific RR and 95 % CI are represented by the black diamond and the horizontal line, respectively; the area of the grey square is proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The centre of the blue open diamond and the red dashed vertical line represent the pooled RR; and the width of the blue open diamond represents the pooled 95 % CI

Gender-specific associations

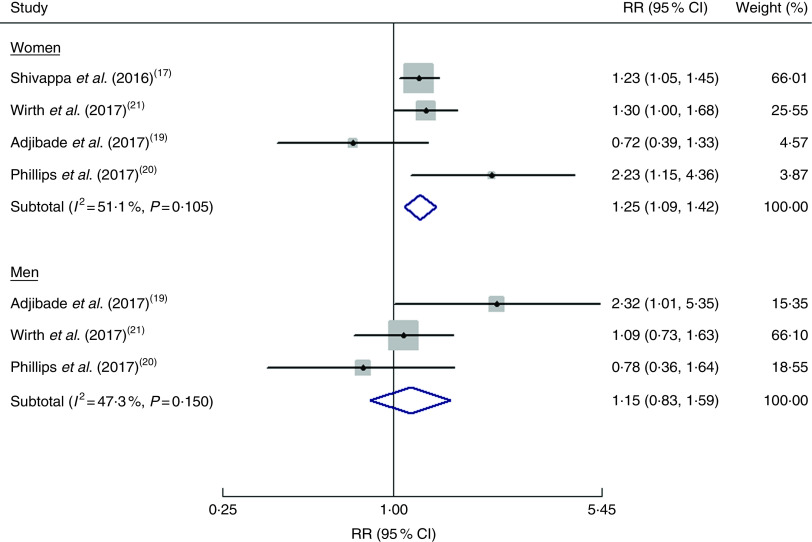

Three studies(19–21) reported the risk estimates by gender and one study(17) provided risk estimates among women. As shown in Fig. 3, the pooled RR of depression was 1·25 (95 % CI 1·09, 1·42; I2=51·1 %, P=0·105) for women and 1·15 (95 % CI 0·83, 1·59; I2=47·3 %, P=0·150) for men when the highest DII score was compared with the lowest DII score.

Fig. 3.

(colour online) Forest plots showing gender-specific risk ratio (RR) of depression for the highest v. the lowest category of dietary inflammatory index (DII®) score. The study-specific RR and 95 % CI are represented by the black diamond and the horizontal line, respectively; the area of the grey square is proportional to the specific-study weight to the overall meta-analysis. The centre of the blue open diamond represents the pooled RR and its width represents the pooled 95 % CI

Discussion

The current meta-analysis suggests that a pro-inflammatory diet as estimated by a higher DII score is independently associated with an increased risk of depression, especially among women. Overall, individuals with the highest DII score (representing the greatest pro-inflammatory dietary potential) had a 23 % higher risk of depression. This finding reveals that modifications of diet inflammatory potential may offer a feasible strategy for preventing depression.

The included epidemiological studies that investigated the association between DII score and depression applied the cross-sectional and prospective cohort designs. Subgroup analysis by study design showed that a significant association of DII score with depression was noted from the prospective cohort studies but it failed to detect an association among the cross-sectional studies. Nevertheless, in cross-sectional studies it is difficult to differentiate a causal association between diet inflammatory potential and depression. Given that the best evidence on this association came from prospective cohort studies, the positive association of the DII score with depression should be robust.

When stratified by gender the association was stronger in women. While suggestive of a positive association between DII score and depression, results in men were not statistically significant. Similar to the current findings with respect to gender differences, data from the Whitehall II Study(27) also displayed a gender-specific association between DII and recurrence of depressive symptoms. These results suggest that dietary sources of inflammation contribute more strongly to depressive symptoms among women than men. Women’s susceptibility to inflammation and its mood effects may account for gender differences in depressive symptoms(28). To clarify the gender-specific inflammatory potential of the diet–depression relationship, more prospective longitudinal studies are needed before a definitive conclusion can be drawn.

Our findings generally are in line with previous meta-analyses(29,30) and support that healthy and Mediterranean dietary patterns could reduce depression risk. The healthy dietary pattern is mainly characterized by high intakes of fruits and vegetables, fish, seafood and wholegrain products. The Mediterranean dietary pattern is characterized by high intakes of fruits, vegetables, legumes, wholegrain products and fish, low to moderate intakes of meat, dairy products and alcohol, and consumption of olive oil. Several foods in these two dietary patterns have anti-inflammatory properties. The DII score is a novel dietary quality tool that specifically focuses on the dietary inflammatory potential. The anti-depressive effect of the healthy and Mediterranean dietary patterns is at least partly owing to the effect of specific food parameters on influencing inflammatory pathways(31). The pro-inflammatory effect of the diet may increase activation of the inflammatory response system. In addition, mechanisms underlying diet that may influence depression or depressive symptoms include effects on neurotransmitters, oxidative stress and the gut–brain axis(32,33).

In practice, it is important to know whether depression can be prevented by changing dietary patterns. Our meta-analysis holds important implications for clinical practice. With diet as a modifiable factor, limiting pro-inflammatory diets and/or favouring anti-inflammatory diets may be an approach for preventing depression and reducing depressive symptoms. For example, dietary supplementation with PUFA could improve inflammation-associated depressive symptoms(34). In addition, nutritional interventions targeting the gut microbiota also could modulate depression(35). Substantial evidence from animal and human research supports a beneficial effect of anti-inflammatory add-on therapy in depression(36). However, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) did not recommend anti-inflammatory diets alone or add-on therapy in depression(37). More well-designed interventional trials are needed to investigate the efficacy of anti-inflammatory diets for the management of depression.

Some potential limitations of the current review should be mentioned. First, the use of various measures of depression is a potential limitation. The included studies applied the CES-D, PHQ-9 or self-reported antidepressant use to determine depression, which may have led to misclassification of participants with depression at enrolment. Second, the DII score was computed by self-report from FFQ or 24h dietary records, which carries an inherent recall bias. Third, the included studies used different cut-off values of DII score for their comparisons of inflammatory diets, which may lead to overestimate or underestimate the pooled risk summary. Fourth, we did not perform subgroup analyses due to the small number of studies included and the results may be unreliable. Finally, generalizability of our findings to diverse populations should be taken with caution because most of the analysed participants were of European descent.

Conclusion

The current meta-analysis suggests that pro-inflammatory diet, as estimated by the DII score, is independently associated with an increased risk of depression, particularly in women. This finding highlights the potential of limiting pro-inflammatory diets and/or favouring anti-inflammatory diets in decreasing depression risk. However, more prospective longitudinal studies with improved methodology are warranted confirm the current findings.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was supported by Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant number 2014021075). The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: J.W., Y.Z. and K.C. contributed equally to this article. J.W., Y.Z. and Y.T.J. conducted the literature research, extracted the data and evaluated the quality of studies. J.A.H. and K.C. performed the statistical analysis. Y.Z. and K.C. drafted/revised the manuscript. H.X.S. revised the manuscript. X.H.H. designed the study and interpreted the results. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Jian Wang, Yao Zhou and Kang Chen contributed equally to this article.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018002628.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Vermeulen E, Stronks K, Visser M et al. (2016) The association between dietary patterns derived by reduced rank regression and depressive symptoms over time: the Invecchiare in Chianti (InCHIANTI) study. Br J Nutr 115, 2145–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC et al. (2007) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 6, 168–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T et al. (2015) The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry 76, 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Villoro R, Merino M & Hidalgo-Vega A (2016) Quality of life and use of health care resources among patients with chronic depression. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 7, 145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (2017) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390, 1211–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu CS, Adibfar A, Herrmann N et al. (2017) Evidence for inflammation-associated depression. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 31, 3–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leonard BE (2018) Inflammation and depression: a causal or coincidental link to the pathophysiology? Acta Neuropsychiatr 30, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lotrich FE (2015) Inflammatory cytokine-associated depression. Brain Res 1617, 113–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rahe C, Unrath M & Berger K (2014) Dietary patterns and the risk of depression in adults: a systematic review of observational studies. Eur J Nutr 53, 997–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM & Fagundes CP (2015) Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry 172, 1075–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perez-Cornago A, de la Iglesia R, Lopez-Legarrea P et al. (2014) A decline in inflammation is associated with less depressive symptoms after a dietary intervention in metabolic syndrome patients: a longitudinal study. Nutr J 13, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kohler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M et al. (2014) Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 1381–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cavicchia PP, Steck SE, Hurley TG et al. (2009) A new dietary inflammatory index predicts interval changes in serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. J Nutr 139, 2365–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG et al. (2014) Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr 17, 1689–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lucas M, Chocano-Bedoya P, Schulze MB et al. (2014) Inflammatory dietary pattern and risk of depression among women. Brain Behav Immun 36, 46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sánchez-Villegas A, Ruiz-Canela M, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C et al. (2015) Dietary inflammatory index, cardiometabolic conditions and depression in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra cohort study. Br J Nutr 114, 1471–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shivappa N, Schoenaker DA, Hebert JR et al. (2016) Association between inflammatory potential of diet and risk of depression in middle-aged women: the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Br J Nutr 116, 1077–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bergmans RS & Malecki KM (2017) The association of dietary inflammatory potential with depression and mental well-being among US adults. Prev Med 99, 313–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adjibade M, Andreeva VA, Lemogne C et al. (2017) The inflammatory potential of the diet is associated with depressive symptoms in different subgroups of the general population. J Nutr 147, 879–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Phillips CM, Shivappa N, Hebert JR et al. (2018) Dietary inflammatory index and mental health: a cross-sectional analysis of the relationship with depressive symptoms, anxiety and well-being in adults. Clin Nutr 37, 1485–1491. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Wirth MD, Shivappa N, Burch JB et al. (2017) The Dietary Inflammatory Index, shift work, and depression: results from NHANES. Health Psychol 36, 760–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al. (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283, 2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al. (2007) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 147, 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Begg CB & Mazumdar M (1994) Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50, 1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M et al. (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shivappa N, Hebert JR, Veronese N et al. (2018) The relationship between the dietary inflammatory index (DII®) and incident depressive symptoms: a longitudinal cohort study. J Affect Disord 235, 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Akbaraly T, Kerlau C, Wyart M et al. (2016) Dietary inflammatory index and recurrence of depressive symptoms: results from the Whitehall II Study. Clin Psychol Sci 4, 1125–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Derry HM, Padin AC, Kuo JL et al. (2015) Sex differences in depression: does inflammation play a role? Curr Psychiatry Rep 17, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lai JS, Hiles S, Bisquera A et al. (2014) A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. Am J Clin Nutr 99, 181–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Y, Lv MR, Wei YJ et al. (2017) Dietary patterns and depression risk: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 253, 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martinez-Gonzalez MA & Sanchez-Villegas A (2016) Food patterns and the prevention of depression. Proc Nutr Soc 75, 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Foster JA & McVey Neufeld KA (2013) Gut–brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci 36, 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lopresti AL, Hood SD & Drummond PD (2013) A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: diet, sleep and exercise. J Affect Disord 148, 12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hastings CN, Sheridan H, Pariante CM et al. (2017) Does diet matter? The use of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and other dietary supplements in inflammation-associated depression. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 31, 321–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koopman M, El Aidy S & consortium MI (2017) Depressed gut? The microbiota–diet–inflammation trialogue in depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry 30, 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Adzic M, Brkic Z, Mitic M et al. (2018) Therapeutic strategies for treatment of inflammation-related depression. Curr Neuropharmacol 16, 176–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Depression in adults: recognition and management. Clinical guideline [CG90]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 (accessed September 2018). [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018002628.

click here to view supplementary material