Abstract

Objective

Limited information is available on the prevalence and effect of hypertriglyceridaemic–waist (HTGW) phenotype on the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in rural populations.

Design

In the present cross-sectional study, we investigated the prevalence of the HTGW phenotype and T2DM and the strength of their association among rural adults in China.

Setting

HTGW was defined as TAG >1·7 mmol/l and waist circumference (WC) ≥90 cm for males and ≥80 cm for females. Logistic regression analysis yielded adjusted odds ratios (aOR) relating risk of T2DM with HTGW.

Participants

Adults (n 12 345) aged 22·83–92·58 years were recruited from July to August of 2013 and July to August of 2014 from a rural area of Henan Province in China.

Results

The prevalence of HTGW and T2DM was 23·71 % (males: 15·35 %; females: 28·88 %) and 11·79 % (males: 11·15 %; females: 12·18 %), respectively. After adjustment for sex, age, smoking, alcohol drinking, blood pressure, physical activity and diabetic family history, the risk of T2DM (aOR; 95 % CI) was increased with HTGW (v. normal TAG and WC: 3·23; CI 2·53, 4·13; males: 3·37; 2·30, 4·92; females: 3·41; 2·39, 4·85). The risk of T2DM with BMI≥28·0 kg/m2, simple enlarged WC and simple disorders of lipid metabolism showed an increasing tendency (aOR=1·31, 1·75 and 2·32).

Conclusions

The prevalence of HTGW and T2DM has reached an alarming level among rural Chinese people, and HTGW is a significant risk factor for T2DM.

Keywords: Hypertriglyceridaemic–waist phenotype, BMI, Waist-to-height ratio, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Public health

Diabetes mellitus became the fourth leading cause of death by chronic non-communicable diseases worldwide in 2012( 1 ) and its prevalence in China is expected to increase from 98·4 to 142·7 million people from 2013 to 2035( 2 ). The disease has represented a significant economic burden for public health systems in recent decades, especially in many low- and middle-income countries( 3 ). In addition, 69·83 % of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) cases are estimated to be undiagnosed among Chinese adults( 4 ).

Mounting evidence suggests that waist circumference (WC) is a useful and easy-to-measure index for predicting T2DM risk( 5 – 7 ). Some researchers have combined WC with TAG level as a new indicator, named the hypertriglyceridaemic–waist (HTGW) phenotype, for T2DM screening( 8 – 10 ). Although some research has focused on the prevalence( 11 – 13 ) and association( 11 ) of HTGW and T2DM, limited evidence exists for Chinese people, especially rural adults.

With the rapid development of the economy and great changes in people’s lifestyle and dietary patterns in rural areas of China, chronic non-communicable diseases including T2DM and cardiometabolic disorders have been prevalent over the past decade( 2 , 4 ). In view of the seriousness of this problem, effective measures are urgently needed to strengthen prevention strategies. However, the density of health-care professionals is lower in rural than urban areas( 14 ). At present, the prevalence of HTGW and the association between HTGW and T2DM among rural Chinese adults are unknown, so knowledge on the epidemic status of HTGW and T2DM in rural areas of China is needed. In the present study, we investigated the prevalence of HTGW and T2DM among rural adults in China as well as the association of HTGW and T2DM and whether HTGW is a risk factor for T2DM.

Methods

Study design and participants

In the present population-based cross-sectional study, we excluded people who were pregnant, disabled, mentally disturbed, obese (caused by disease) or had cancer. A total of 16 155 participants were recruited by cluster randomization from eligible candidates listed in the residential registration record from July to August of 2013 and July to August of 2014 from a rural area of Henan Province in China. After excluding people with concurrent use of lipid-modified agents (n 1277) and those without complete data for diabetes ascertainment (n 2533), 12 345 participants (7628 females) aged 22·83 to 92·58 years were retained.

Demographic characteristics and health-related behaviours such as sex, age, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, medical history and medication history were collected by face-to-face interviews. Body weight and height were measured twice to the nearest 0·5 kg and 0·5 cm, respectively, with the participant wearing light clothing and no shoes. WC was measured twice to the nearest 0·5 cm by a single examiner who used a standard tape measure placed horizontally 1·0 cm above the navel with participants wearing light clothing and standing. Blood pressure was measured three times for all participants, who were sitting after a rest of 5 min, by use of an electronic sphygmomanometer (Omron HEM-770AFuzzy, Kyoto, Japan). Overnight fasting blood samples were collected and stored at −20°C for measuring glucose and TAG by use of an automatic biochemical analyser (Hitachi 7060, Tokyo, Japan).

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University. All participants provided written informed consent.

Definition of terms

According to the new International Diabetes Federation definition of metabolic syndrome for Chinese people( 14 ), the HTGW phenotype was divided into four classes: (i) NTNW, i.e. normal TAG level (≤150 mg/dl (≤1·7 mmol/l)) and normal WC (<90 cm for males and <80 cm for females); (ii) NTGW, i.e. normal TAG level and enlarged WC (≥90 cm for males and ≥80 cm for females); (iii) HTNW, i.e. elevated TAG level (>150 mg/dl (>1.7 mmol/l)) and normal WC; and (iv) HTGW, i.e. elevated TAG level and enlarged WC.

According to the 2005 American Diabetes Association criteria( 15 ), T2DM was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l and/or the use of insulin or oral hypoglycaemic agents and/or a self-reported history of diabetes and without type 1 diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes mellitus or diabetes due to other causes.

BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres, and classified as normal weight (<24.0 kg/m2), overweight (24.0–27.9 kg/m2) and obesity (≥28.0 kg/m2)( 16 ). Waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) was calculated as waist in centimetres divided by height in centimetres, and classified as normal (<0.5) and abnormal (≥0.5)( 17 ). Smoking was defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes during the lifetime; alcohol drinkers were defined as consuming alcohol twelve or more times during the past year( 18 ). Physical activity level was classified as low, moderate or high based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (www.ipaq.ki.se). One or both parents having diabetes was considered a diabetic family history.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as number and percentage and were compared by the χ 2 test. Continuous data are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR; because of skewed distribution) and were compared by the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test. Age-standardized prevalence was calculated by using the age distribution of the Chinese population from the 2010 census data. Logistic regression was used to obtain OR, 95 % CI and corresponding P values for T2DM associated with BMI, WHtR and HTGW, with adjustment for potential confounding variables including sex, age, smoking, alcohol drinking, blood pressure, physical activity and diabetic family history. All data were analysed using the statistical software package SAS version 9.10 for Windows. P<0·05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant.

Results

The general characteristics of the 12 345 participants (4717 males) are presented in Table 1. Overall, 1455/12 345 participants (11·79 %) had T2DM. The prevalence of HTGW, obesity and abnormal WHtR was 23·71, 18·39 and 67·72 %, respectively. Obesity, abnormal WHtR, low physical activity, HTGW and positive family history of diabetes were more frequent among participants with than among those without T2DM. The corresponding age-standardized prevalence for HTGW and T2DM was 22·60 and 9.40 %, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants: adults (n 12 345) aged 22·83–92·58 years from a rural area of Henan Province in China, 2013 and 2014

| Total (n 12 345) | Non-T2DM (n 10 890) | T2DM (n 1455) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Median or n | IQR or % | Median or n | IQR or % | Median or n | IQR or % | P value |

| Age (years), median and IQR | 56.62 | 47.45–65.14 | 55.88 | 46.78–64.83 | 60.61 | 53.40–67.42 | <0.0001 |

| Male, n and % | 4717 | 38.21 | 4191 | 38.48 | 526 | 36.15 | 0.0853 |

| FBG (mmol/l), median and IQR | 5.17 | 4.75–5.67 | 5.10 | 4.70–5.49 | 7.94 | 6.87–10.14 | <0.0001 |

| SBP (mmHg), median and IQR | 123.67 | 112.00–138.67 | 123.00 | 111.33–138.00 | 130.33 | 118.00–146.33 | <0.0001 |

| DBP (mmHg), median and IQR | 76.67 | 69.67–85.00 | 76.67 | 69.67–84.67 | 78.33 | 71.33–86.33 | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median and IQR | 24.61 | 22.24–27.13 | 24.43 | 22.07–26.94 | 25.88 | 23.44–28.40 | <0.0001 |

| BMI category, n and % | |||||||

| <24.0 kg/m2 | 5427 | 43.96 | 4958 | 45.53 | 469 | 32.23 | <0.0001 |

| 24.0–27.9 kg/m2 | 4648 | 37.65 | 4057 | 37.25 | 591 | 40.62 | |

| ≥28.0 kg/m2 | 2270 | 18.39 | 1875 | 17.22 | 395 | 27.15 | |

| WHtR, median and IQR | 0.53 | 0.49–0.58 | 0.53 | 0.48–0.57 | 0.56 | 0.52–0.61 | <0.0001 |

| WHtR category, n and % | |||||||

| <0.5 | 3985 | 32.28 | 3741 | 34.35 | 244 | 16.77 | <0.0001 |

| ≥0.5 | 83.60 | 67.72 | 7149 | 65.65 | 1211 | 83.23 | |

| Smoking status, n and %† | |||||||

| Non-smoker | 8952 | 72.59 | 7846 | 72.13 | 1106 | 76.07 | 0.0016 |

| Smoker | 3380 | 27.41 | 3032 | 27.87 | 348 | 23.93 | |

| Alcohol drinking status, n and %† | |||||||

| Non-drinker | 10 931 | 88.67 | 9594 | 88.23 | 1337 | 91.95 | <0.0001 |

| Drinker | 1397 | 11.33 | 1280 | 11.77 | 117 | 8.05 | |

| Physical activity, n and %† | |||||||

| Low | 5485 | 48.83 | 4762 | 47.57 | 723 | 59.12 | <0.0001 |

| Moderate | 779 | 6.93 | 714 | 7.13 | 65 | 5.31 | |

| High | 4969 | 44.24 | 4534 | 45.29 | 435 | 35.57 | |

| Family history of diabetes, n and % | 949 | 7.69 | 776 | 7.13 | 173 | 11.89 | <0.0001 |

| Waist/TAG combination, n and % | |||||||

| NTNW | 4537 | 36.75 | 4250 | 39.03 | 287 | 19.73 | <0.0001 |

| NTGW | 3535 | 28.64 | 3109 | 28.55 | 426 | 29.28 | |

| HTNW | 13.46 | 10.90 | 1196 | 10.98 | 150 | 10.31 | |

| HTGW | 2927 | 23.71 | 2335 | 21.44 | 592 | 40.69 | |

T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; IQR, interquartile range; FBG, fasting blood glucose; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; WHtR, waist-to-height-ratio; NTNW, normal TAG level (≤150 mg/dl (≤1.7 mmol/l)) and normal waist circumference (WC; <90 cm for men and <80 cm for women); NTGW, normal TAG level and enlarged WC (≥90 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women); HTNW, elevated TAG level (>150 mg/dl (>1.7 mmol/l)) and normal WC; HTGW, elevated TAG level and enlarged WC.

†Data were missing for some participants.

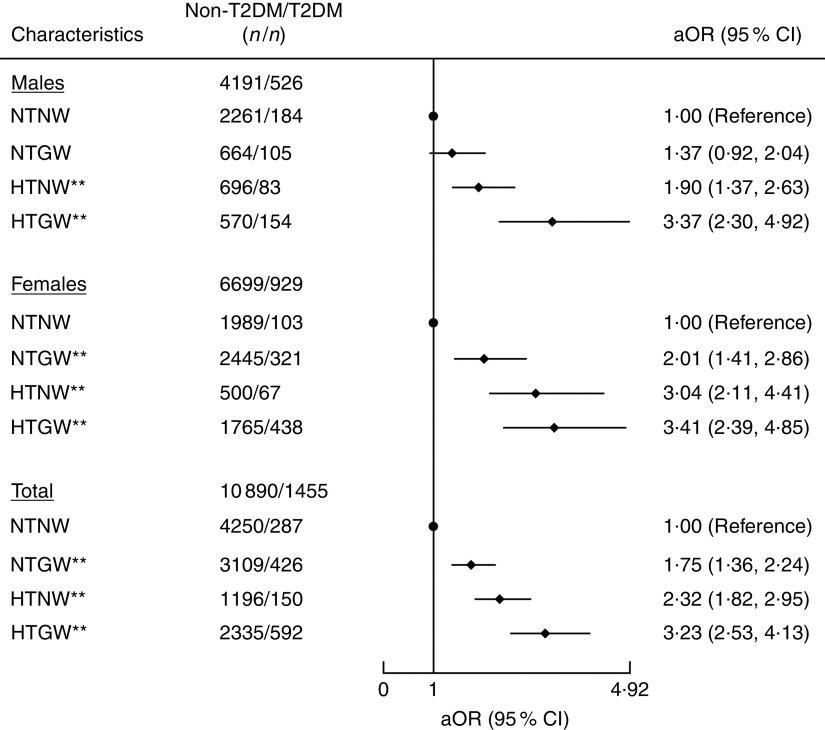

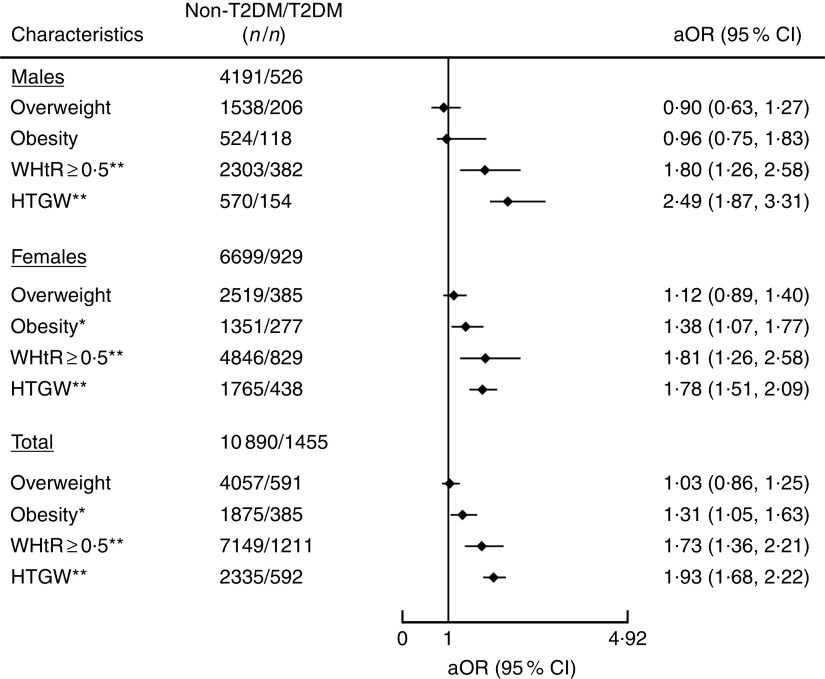

After adjustment for age, sex, smoking, alcohol drinking, blood pressure, physical activity and diabetic family history, NTGW, HTNW and HTGW were all significantly associated with T2DM. The risk of T2DM was increased with NTGW, HTNW and HTGW as compared with the reference category of NTNW (adjusted OR (aOR)=1·75; 95 % CI 1·36, 2·24, aOR=2·32; 95 % CI 1·82, 2·95 and aOR=3·23; 95 % CI 2·53, 4·13, respectively; Fig. 1), as well as with obesity as compared with the reference category of BMI<24·0 kg/m2 (aOR=1·31; 95 % CI 1·05, 1·63) and with WHtR≥0·5 as compared with reference category of WHtR <0·5 (aOR=1·73; 95 % CI 1·36, 2·21; Fig. 2). Among these risk factors, including obesity, abnormal WHtR, HTNW, NTGW and HTGW, the risk of T2DM was highest with HTGW (Figs 1 and 2). As compared with all other participants, for HTGW participants, the risk of T2DM was increased for males (OR=2·49; 95 % CI 1·87, 3·31), females (OR=1·78; 95 % CI 1·51, 2·09) and overall (OR=1·93; 95 % CI 1·68, 2·22; Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Association of hypertriglyceridaemic–waist phenotype with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) among adults (n 12 345) aged 22·83–92·58 years from a rural area of Henan Province in China, 2013 and 2014. Adjusted OR (aOR; ♦), with their 95 % CI indicated by horizontal bars, adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol drinking, blood pressure, physical activity and diabetic family history. **P<0·001 (NTNW, normal TAG level (≤150 mg/dl (≤1·7 mmol/l)) and normal waist circumference (WC; <90 cm for men and <80 cm for women); NTGW, normal TAG level and enlarged WC (≥90 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women); HTNW, elevated TAG level (>150 mg/dl (>1·7 mmol/l)) and normal WC; HTGW, elevated TAG level and enlarged WC)

Fig. 2.

Association of different metabolic types with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) among adults (n 12 345) aged 22·83–92·58 years from a rural area of Henan Province in China, 2013 and 2014. Adjusted OR (aOR; ♦), with their 95 % CI indicated by horizontal bars, adjusted for age, sex, smoking, alcohol drinking, blood pressure, physical activity and diabetic family history. *P<0·05, **P<0·001 (overweight, BMI=24·0–27·9 kg/m2; obesity, BMI≥28·0 kg/m2; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio; HTGW, elevated TAG level (>150 mg/dl (>1·7 mmol/l)) and enlarged waist circumference WC (≥90 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women))

Discussion

In the present study, we found that among adults in rural China the prevalence of HTGW and T2DM has reached an alarming level. We found increased risk of T2DM with obesity, abnormal WHtR, low physical activity, HTGW or family history of diabetes. Of note, the risk of T2DM with BMI ≥28·0 kg/m2, simple enlarged WC or simple disorders of lipid metabolism showed an increasing tendency, and the risk was higher with HTGW than with obesity, abnormal WHtR, HTNW or NTGW.

As a specific metabolic abnormality, HTGW was first reported as a marker of atherosclerosis in 2000( 19 ). Studies over the last 16 years have shown that the prevalence of HTGW is increasing substantially( 11 ). Although the age-standardized prevalence of HTGW in China is lower than in Iran (age ≥30 years: 22·06 v. 32·7 %)( 20 ), it is higher now than in China in 2013 (age 25–64 years: 22·06 v. 11·79 %)( 21 ). As well, our age-standardized prevalence results for T2DM are slightly lower than those from the 2012 national health survey results (9·4 v. 9·7 %) but slightly higher than the prevalence in India in 2013 (age 20–79 years: 9·4 v. 9·1 %)( 2 ). According to epidemiological studies, HTGW( 22 , 23 ) and T2DM( 1 ) are both leading causes of death from non-communicable diseases; thus, China is currently facing an epidemiological transition with a double burden of HTGW and T2DM, as we showed. Intervention and screening of HTGW and diabetic high-risk groups have become the key measures to control non-communicable diseases.

BMI and WHtR are significantly associated with risk of T2DM( 24 , 25 ). Overweight, obesity and WHtR≥0.5 are appropriate for defining the diabetes risk. Also, we found the association to be stronger in participants with abnormal WHtR than in those with overweight or obesity. The association between body weight and T2DM is more properly attributed to the quantity and distribution of body fat, and our research testifies that ‘abdominal obesity is highly correlated with T2DM’( 26 ). From our results, risk of T2DM was higher with HTNW than with abnormal WHtR or NTGW, which suggests that the risk of T2DM was stronger with simple disorders of lipid metabolism than with simply enlarged WC. Among these risk factors, including obesity, abnormal WHtR, HTNW, NTGW and HTGW, the association was strongest with HTGW for males and overall. For females, the risk of T2DM was higher with abnormal WHtR than with HTGW (OR=1·81 v. 1·78). This result suggests the potential benefits of using HTGW over abnormal WHtR for men only. In a recent cohort study of 2908 Chinese urban adults followed for 3 years, HTGW was associated with a 3·77-fold increased risk of diabetes for males and a 6·08-fold increased risk for females( 27 ). Another 4-year longitudinal study of 2900 Korean adults showed increased risk of diabetes with HTGW (hazard ratio=4·113; 95 % CI 2·397, 7·059) after adjustment( 28 ), which agrees with our study and a study by Janghorbani and Amini( 29 ). Although previous studies did not mention the direct mechanism of the association between HTGW and T2DM, the underlying mechanism of T2DM caused by HTGW might be that excessive abdominal fat accumulation and elevated TAG level increase the risk of insulin resistance( 30 – 32 ), and HTGW is associated with overstimulation of β-cell function( 33 ), which contributes to blood glucose metabolism disorder and T2DM.

Although the present study involved 12 345 participants, representing a large population study in a rural area in China, it has several limitations. First, the causal relationship between HTGW and T2DM cannot be concluded because of the cross-sectional study design. Second, participants did not undergo an oral glucose tolerance test, so the prevalence of T2DM might be underestimated. Third, dietary intake information was not included in the analysis, so we cannot eliminate its potential effect on the association of HTGW with T2DM. Finally, to have an explicit distinction of the HTGW phenotype, we excluded participants with concurrent use of lipid-modifying agents because of their indistinct dyslipidaemia, which might have underestimated the prevalence of HTGW. We eliminated some treated HTGW cases and reduced observational bias, but the impact of use of lipid-modifying agents on the association between HTGW and T2DM is unclear.

In summary, the prevalence of HTGW and T2DM is relatively high among rural adult Chinese people. People with obesity, abnormal WHtR, NTGW, HTNW or HTGW are all at high risk of T2DM. Early screening is of great significance among these high-risk populations for an early diagnosis and treatment of T2DM. The association between HTGW and T2DM was stable and significant. HTGW might be a simple and effective index for screening for people at high risk of T2DM, and higher-level evidence could be obtained with more cohort study designs.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors express thanks to all the individuals who participated in the study. They are particularly grateful to the doctors and nurses involved in this study for their assistance. They also thank Laura Smales (BioMedEditing) for copyediting the manuscript. Financial support: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81373074, 81402752 and 81673260); the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant number 2017A03013452); the Medical Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant number A2017181); and the Science and Technology Development Foundation of Shenzhen (grant numbers JCYJ20140418091413562, JCYJ20160307155707264, JCYJ20170302143855721 and JCYJ20170412110537191). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study. Authorship: Y.-C.R., M.Z. and D.-S.H. substantially contributed to the design and drafting of the study and the analysis and interpretation of the data. Yu.L, X.-Z.S., B.-Y.W., Yi.L., H.N., Y.Z., D.-C.L., X.-J.L., D.-D.Z., F.-Y.L., C.C., L.-L.L. and Q.-G.Z. revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors were involved in the collection of data and approved the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (2014) Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I et al. (2014) Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 103, 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seuring T, Archangelidi O & Suhrcke M (2015) The economic costs of type 2 diabetes: a global systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 33, 811–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xu Y, Wang L, He J et al. (2013) Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. JAMA 310, 948–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wei W, Xin X, Shao B et al. (2015) The relationship between anthropometric indices and type 2 diabetes mellitus among adults in north-east China. Public Health Nutr 18, 1675–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Luo W, Guo Z, Hu X et al. (2013) 2 years change of waist circumference and body mass index and associations with type 2 diabetes mellitus in cohort populations. Obes Res Clin Pract 7, e290–e296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shiwaku K, Anuurad E, Enkhmaa B et al. (2005) Predictive values of anthropometric measurements for multiple metabolic disorders in Asian populations. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 69, 52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Daniel M, Paquet C, Kelly SJ et al. (2013) Hypertriglyceridemic waist and newly-diagnosed diabetes among remote-dwelling Indigenous Australians. Ann Hum Biol 40, 496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Díaz-Santana MV, Suárez Pérez EL, Ortiz Martínez AP et al. (2016) Association between the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype, prediabetes, and diabetes mellitus among adults in Puerto Rico. J Immigr Minor Health 18, 102–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carlsson AC, Risérus U & Ärnlöv J (2014) Hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype is associated with decreased insulin sensitivity and incident diabetes in elderly men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22, 526–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ren Y, Luo X, Wang C et al. (2016) Prevalence of hypertriglyceridemic waist and association with risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 32, 405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Han C, Zhang M, Luo X et al. (2016) Secular trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in adults in China from 1995 to 2014: a meta-analysis. J Diabetes 9, 450–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gong H, Pa L, Wang K et al. (2015) Prevalence of diabetes and associated factors in the Uyghur and Han population in Xinjiang, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12, 12792–12802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. International Diabetes Federation (2006) The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome. Belgium: IDF. [Google Scholar]

- 15. American Diabetes Association (2005) Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care 28, Suppl. 1, S4–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Corporative Meta-Analysis Group of China Obesity Task Force (2002) Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference to risk factors of related diseases in Chinese adult population. Chin J Epidemiol 23, 5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guangdong Provincial Co-operation Group for Diabetes Epidemiological Study (2004) Waist/height ratio: an effective index for abdominal obesity predicting diabetes and hypertension. Chin J Endocrinol Metab 3, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang C, Li J, Xue H et al. (2015) Type 2 diabetes mellitus incidence in Chinese: contributions of overweight and obesity. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 107, 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lemieux I, Pascot A, Couillard C et al. (2000) Hypertriglyceridemic waist: a marker of the atherogenic metabolic triad (hyperinsulinemia; hyperapolipoprotein B; small, dense LDL) in men? Circulation 102, 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Samadi S, Bozorgmanesh M, Khalili D et al. (2013) Hypertriglyceridemic waist: the point of divergence for prediction of CVD vs. mortality: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Int J Cardiol 165, 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. He S, Zheng Y, Shu Y et al. (2013) Hypertriglyceridemic waist might be an alternative to metabolic syndrome for predicting future diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 8, e73292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hobkirk JP, King RF, Gately P et al. (2013) The predictive ability of triglycerides and waist (hypertriglyceridemic waist) in assessing metabolic triad change in obese children and adolescents. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 11, 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gasevic D, Carlsson AC, Lesser IA et al. (2014) The association between ‘hypertriglyceridemic waist’ and sub-clinical atherosclerosis in a multiethnic population: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis 13, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu Z, Qi X, Dahl AK et al. (2013) Waist-to-height ratio is the best indicator for undiagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 30, e201–e207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hsu WC, Araneta MR, Kanaya AM et al. (2015) BMI cut points to identify at-risk Asian Americans for type 2 diabetes screening. Diabetes Care 38, 150–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ohlson LO, Larsson B, Svardsudd K et al. (1985) The influence of body fat distribution on the incidence of diabetes mellitus. 13.5 years of follow-up of the participants in the study of men born in 1913. Diabetes 34, 1055–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang M, Gao Y, Chang H et al. (2012) Hypertriglyceridemic-waist phenotype predicts diabetes: a cohort study in Chinese urban adults. BMC Public Health 12, 1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Han KJ, Lee SY, Kim NH et al. (2014) Increased risk of diabetes development in subjects with the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype: a 4-year longitudinal study. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 29, 514–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Janghorbani M & Amini M (2016) Utility of hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype for predicting incident type 2 diabetes: the Isfahan Diabetes Prevention Study. J Diabetes Investig 7, 860–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scott R A, Fall T, Pasko D et al. (2014) Common genetic variants highlight the role of insulin resistance and body fat distribution in type 2 diabetes, independent of obesity. Diabetes 63, 4378–4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kassi E, Pervanidou P, Kaltsas G et al. (2011) Metabolic syndrome: definitions and controversies. BMC Med 9, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kahn SE, Hull RL & Utzschneider KM (2006) Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 444, 840–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shadid S, Kanaley J A, Sheehan M T et al. (2007) Basal and insulin-regulated free fatty acid and glucose metabolism in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292, E1770–E1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]