Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) treatment is freely available in the Brazilian public health system. However, the prescription pattern and its associated factors have been poorly studied in our country. We reviewed all granted requests for AD treatment in the public health system in October 2021 in the Rio Grande do Sul (RS) state, Southern Brazil. We performed a spatial autocorrelation analysis with the population-adjusted patients receiving any AD medication as the outcome and correlated it with several socioeconomic variables. 2382 patients with AD were being treated during the period analyzed. The distribution of the outcome variable was not random (Moran's I 0.17562, P <.0001), with the most developed regions having a higher number of patients/100,000 receiving any AD medication. We show that although AD medications are available through the public health system, there is a clear disparity between regions of RS state. Factors related to socioeconomic development partly explain this finding.

Subject terms: Alzheimer's disease, Dementia

Introduction

Dementia is a leading cause of disability in the elderly, currently affecting around 60 million people worldwide, with an estimated prevalence to triple by 20501. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the main cause of dementia, accounting for 60–70% of cases, and is characterized clinically by progressive decline in cognition, behavior and functionality and biologically by brain accumulation of abnormal amyloid β and hyperphosphorylated tau2.

The pharmacological treatment for AD is fundamentally symptomatic and consists mainly of three acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEi) (donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine) and one antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, memantine. The effect size of these drugs is generally modest, although some patients may experience a more robust benefit3. In Brazil, these medications have been approved since 2002 and are freely available in the public health system (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS) through an evaluation conducted by a specific program known Specialized Component of Pharmaceutical Assistance). Under this program, all requests must meet specific criteria based on Clinical Practice Guidelines4. In the last version of that Guideline, AChEi are recommended to mild and moderate disease and memantine to moderate and severe stages5,6.

Although these medications are available throughout the country, there may be barriers to access of these treatments. Bureaucratic intricacies, geographic accessibility and other socioeconomic factors can affect the provision of these medications6–8. Patient-related factors such as formal education and race also appear to contribute to limited access9,10. In addition, the underdiagnosis of dementia in Brazil is probably a central component for the medications access, a phenomenon related, among other causes, to scarcity of physicians and their poor capacity to perform these diagnoses11. In a previous Brazilian study, Moraes et al. showed that there were more prescriptions for AD medications in the more developed regions of the country12, a probable indicator of the fragility of the diagnostic and therapeutic process of patients with dementia.

Although Brazil is a continental country with a well-structured and comprehensive public health system, few studies have evaluated possible disparities in the AD medications prescriptions and none were performed in Rio Grande do Sul (RS), the 6th most populous in the country. Therefore, our aim is to evaluate the spatial pattern of pharmacological treatment for AD in RS and possible factors associated with this pattern.

Methods

We performed a study with two different designs. A cross-sectional study, in which we analyzed the profile of patients receiving medication for AD in October 2021 in the state of RS, Brazil. And an ecological study, where we analyzed the prescription profile of AD medications in all municipalities of RS during this period. We reviewed all requests granted for medications for AD in the Health Department of the State of RS in October 2021. We evaluated requests for the four medications available in the public health system, in any formulation or dose: donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine. As recommended by the National Guidelines, in the state of RS the requests for medication for AD through the public system are initially performed by the attending physician through a web-based system called AME (Administração de Medicamentos Especiais), managed by the RS State Health Secretariat. Requests from all over the state are evaluated through an administrative process and centrally approved or denied by a trained team located in the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, the state capital. The established guidelines and process are necessary to prevent the irrational use of these drugs6. Within this administrative process, minimum clinical data, such as Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)13,14 and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale15,16 should be added, in addition to laboratory and imaging tests that attest that the patient has AD as the probable etiology for the dementia syndrome.

Study variables

In the cross-sectional study we evaluated the following variables: patients' age, sex, educational attainment, city of origin, total score on MMSE and CDR scales and type/dose of AD medication prescribed. All these variables were extracted from the web-based system (AME), the administrative system through each request is made and judged.

In the ecological analysis we evaluated the total number of patients/100,000 inhabitants (outcome variable) for each municipality who were receiving any AD medication. We performed a spatial autocorrelation analysis to assess the distribution pattern of the variable patients/100,000/municipality in the state of RS in October 2021. After this evaluation, we correlated the outcome variable with the following factors of each municipality: percentage of female patient sex, mean patients’ age, mean patients’ MMSE, percentage of patients ≥ 65 years, death records by AD, human development index (HDI), gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, income per capita, proportion of rural households, percentage of patients with elementary, high school, university education and illiterates, total number of physicians and the median time (in years) as a physician, a measure of experience as a physician. All variables related to the municipalities were obtained from the Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System (DATASUS) of Brazil17 and the Atlas of Human Development of Brazil18, both freely available. The experience as a physician was extracted from the open access State Medicine Council database19.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described by frequency and continuous ones by mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR), according to their distribution. The association between the continuous variables was evaluated by the Spearman coefficient. The pattern of distribution among the RS municipalities was evaluated by spatial autocorrelation using Moran's I index. All analyses were performed using the built-in functions and the packages "sf", "tmap" and "ggplot2" of the R software (V 4.2.1).

Ethics approval

This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (CAAE 43246921.7.0000.5327) and the State Health Secretariat (CAAE 43246921.7.3001.5312).

Consent to participate

A consent was not necessary as the patient’s data were obtained from databases, whose access was granted by the Health Department of the Rio Grande do Sul State.

Results

In October 2021, in the state of RS, Brazil, 2,382 AD patients were using any of the four drugs through the Brazilian public health system. The majority, 65.6% (1,562), were female, had a median age of 79 (73–84) years and 71.7% (1036) had incomplete elementary education. The patients' MMSE median was 15 (12–18) and most had a CDR = 2 (55.2%, 1133) (Table 1). The most prescribed medication was donepezil, 42.9% (1014), alone or in combination with memantine. We described all AD medications used in the sample in Online Resource 1. Most professionals who prescribed these medications were experienced physicians, with a median professional activity of 18 (9–30) years.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients receiving medication for Alzheimer's disease in the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Total sample | 2,382 |

| Female (%) | 1,562 (65.5) |

| Age median (IQR) | 79 (73–84) |

| Education (%) | |

| Illiteracy | 96 (6.6) |

| Elementary school complete | 134 (9.3) |

| Elementary school incomplete | 1,036 (71.7) |

| High school complete | 57 (3.9) |

| High school incomplete | 51 (3.5) |

| University education complete | 49 (3.4) |

| University education incomplete | 22 (1.5) |

| MMSE | |

| median (IQR) | 15 (12–18) |

| Clinical dementia rating (CDR) Scale (%) | |

| CDR 0 | 3 (0.1) |

| CDR 0.5 | 37 (1.8) |

| CDR 1 | 830 (40.4) |

| CDR 2 | 1,133 (55.2) |

| CDR 3 | 51 (2.5) |

MMSE Mini mental state examination.

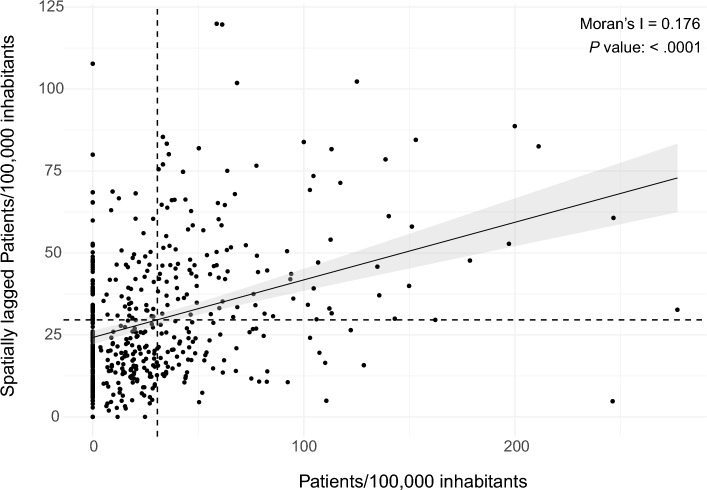

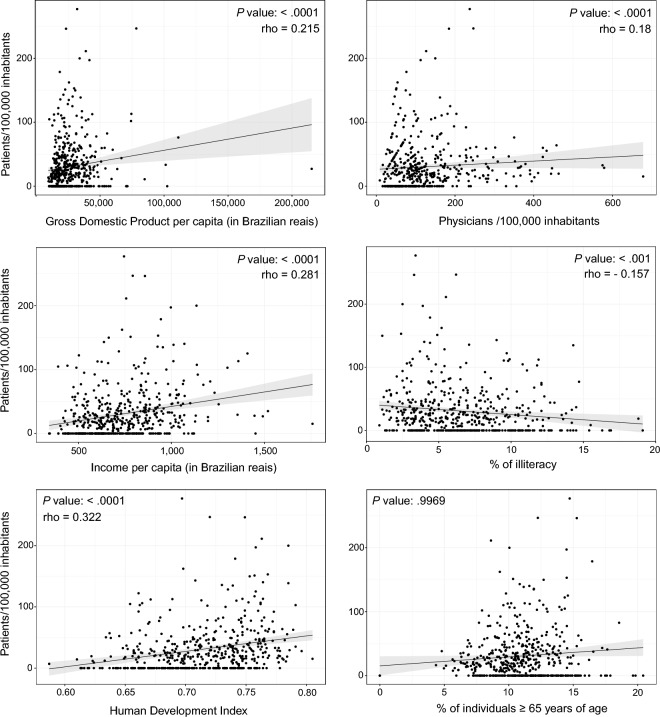

Most municipalities had at least one patient receiving an AD medication (339/498, 68.2%). The median of patients/100,000/municipality using any AD medication was 19.4 [0–42.8], ranging from 0 to 277. The sociodemographic of RS state municipalities are shown in Table 2. We found that the variable patient/100,000/municipality was clustered, with the Moran's I of 0.17562 (P < .001) (Figs. 1 and 2), with the North and Northeast regions concentrating the prescriptions. As the distribution of this variable was not random, we correlated it with municipalities sociodemographic variables. Several variables had weak correlation with patients/100,000/municipality such as HDI (rho = 0.32), GDP per capita (rho = 0.21), income per capita (rho = 0.281), physicians/100,000 inhabitants (rho = 0.17) and % of illiteracy (rho =−0.16) (Fig. 3). Table 3 presents the correlation of all variables.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic- and patient-related variables from municipalities in the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

| Median (IQR) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients/100,000 inhabitants | 19.4 (0–42.8) | 0–277 |

| HDI | 0.717 (0.685–0.746) | 0.587–0.805 |

| GDP per capita (in Brazilian reais) | 22,475 (17,509–31,372) | 9,597–215,394 |

| Income per capita (in Brazilian reais) | 714.3 (595.9–862.7) | 343.1–1758.3 |

| % Rural domicile | 47 (21–66.8) | 0–98.6 |

| Education | ||

| % Illiteracy | 6.1 (3.9–8.5) | 0.9–19.1 |

| % Elementary | 35.4 (28.4–43.3) | 14.1–73.5 |

| % High school | 20.5 (15.8–26.4) | 5.3–57.8 |

| % University | 5.4 (3.9–7.5) | 0.4–25.9 |

| % Female | 66.7 (50–100) | 0–100 |

| Patients' age | 78 (75–81) | 57–95 |

| % age ≥ 65 years | 10.9 (9.4–12.5) | 0–20.4 |

| MMSE | 15 (13–17) | 2–30 |

| Deaths from AD/100,000 inhabitants | 24.1 (15.7–38.6) | 2.6–261.8 |

| Physicians/100,000 inhabitants | 97.46 (60.8–156.2) | 9–678 |

| Experience as a physician (in years) | 18.7 (11.8–25.2) | 0–53 |

AD Alzheimer's disease, GDP Gross domestic product, HDI Human development index, MMSE Mini mental state examination.

Figure 1.

Choropleth map of spatial distribution of patients/100,000 inhabitants receiving Alzheimer's disease medications in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Maps created with R software, version 4.2.2, and Adobe Illustrator, version 27.5.

Figure 2.

Moran scatter plot, showing the correlation between the patients/100,000 variable and its spatial lag.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots between patients/100,000 inhabitants and socioeconomic variables.

Table 3.

Correlation between patients/100,000/municipality and sociodemographic-, patient- and medical-related variables.

| Spearman’s rho (P value) * | |

|---|---|

| HDI | 0.32 (< .0001) |

| GDP per capita | 0.21 (< 0.001) |

| Income per capita | 0.28 (< 0.0001) |

| % Rural domicile | ns |

| Education | |

| % Illiteracy | −0.16 (< 0.001) |

| % Elementary | 0.19 (< 0.0001) |

| % High school | 0.19 (< 0.0001) |

| % University | 0.17 (< 0.001) |

| % Female | ns |

| Patients' age | ns |

| % age ≥ 65 years | ns |

| MMSE | ns |

| Deaths from AD/100,000 inhabitants | ns |

| Physicians/100,000 inhabitants | 0.17 (< 0.001) |

| Experience as a physician (in years) | ns |

*P value threshold after Bonferroni correction (< .002), ns not significant, AD Alzheimer's disease, GDP Gross domestic product, HDI Human development index, MMSE Mini mental state examination.

Discussion

In our study, we were able to assess the pattern of AD medications granted by the Brazilian health system in the state of RS. We showed that although these medications are available to all patients through the Brazilian public health system, there is a clear disparity between regions. Previous Brazilian studies had already shown that there was some disparity in the supply of these medication, but none of them had evaluated a whole state or attempted to assess factors related to possible disparities7,12; moreover, the evaluation through spatial autocorrelation is innovative in this regard, since it is the first time that an ecological approach had been performed to evaluate the spatial distribution of drugs for AD.

We showed that the number of patients/100,000 inhabitants did not have a random pattern (Moran's I of 0.17562, P < .001), with the north and northeast regions having more patients/prescriptions, adjusted for the population, than other regions of the state. Such an uneven pattern of prescription of AD drugs has already been demonstrated in other countries. Hausner et al. evaluated the distribution of dementia drugs in several European countries and showed that southern countries had fewer patients using these drugs9. As the pattern was not random, we were able to correlate the variable patients/100,000 inhabitants with some sociodemographic characteristics of the municipalities. Several socioeconomic development variables showed weak correlation with the outcome variable, such as the Human Development Index and Gross Domestic Product. This finding is similar to previous studies that showed that economic disadvantages were determinant for the distribution of AD medications. In an Australian study, patients from more developed regions were 2.4 times more likely to receive some medication for AD than less developed regions8. Copper et al., despite not having assessed a regional pattern of prescription in London, showed that people who did not own a home receive less medication for AD from the British public health system20.

Another factor related to the number of patients/100,000 inhabitants was the formal education. We showed that there was a positive correlation between the percentage of patients who had elementary, high school and university education with the outcome variable. This finding corroborates previous studies that showed that years of formal education were related to the prescription of AD medications. In a large Swedish study, Johnell et al. identified that patients with more that 15 years of schooling receive more prescriptions than those with less than 9 years of education21. Similar findings were seen in US22 and UK23 patients. Certainly, years of formal education is a marker of sociodemographic development and therefore it is not surprising that these variables are also related to the distribution of AD medications.

Remoteness and living in rural areas are factors usually associated with probability of prescription of AD medications, either with fewer prescriptions24 or more prescriptions25. In our study, there was no association between the percentage of rural households and the number of patients/100,000 inhabitants. A possible explanation for this finding is that the supply of AD medications is carried out at the health department of each municipality and not at a regional center, i.e., access is close and similar in every town.

Finally, we tried to assess whether factors related to the patients or to the physicians who prescribed the medications could correlate with the number of patients receiving AD medications in each municipality. Patient's age, sex, MMSE scores and AD deaths records were not associated with the outcome. These are in line with previous findings23,26. One hypothesis is that the characteristics of the patients are usually similar between different regions, therefore not being a determining factor for the spatial distribution pattern of AD medications. We showed that the total number of physicians/100,000 per municipality, but not the experience as a physician, was weakly associated (rho=0.17) with the number of patients receiving any medication. Although we did not find a previous study that showed a similar result, we consider it to be a straightforward finding, since fewer physicians in a municipality indicate a lower chance of these drugs being prescribed.

One might argue that all variables that were associated with the number of patients/100,000 inhabitants had weak correlation coefficients. However, this finding may be related to the fact that there are multiple determining factors in the chain of events necessary for a patient with AD to receive one of these medications. The correct clinical suspicion by family members, the availability and access to health services capable of performing the diagnosis and the correct completion of the form by the physician, all these steps can be barriers to accessing these medications. We hypothesize that all these steps may work more quickly and efficiently in more developed regions.

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients receiving an AD drug in our study were similar to what had been seen in other studies, as most were women with low education27,28. In addition, most of the patients had moderate dementia (CDR = 2). Although we know that patients with dementia usually have a diagnostic delay in Brazil29, we could not assess whether this delay was associated with our results. We also found 3 patients with CDR = 0 receiving AD medication. We were unable to assess whether it was a typo in the web system or an error in evaluating the request. Regarding the type of medication prescribed, most patients were using donepezil, a change in prescription pattern in the state of RS, since a previous study performed in 2010 showed that rivastigmine was the most prescribed medication, 86.1%6. However, it is similar to a more recent Brazilian study12.

Our study has some limitations. First and foremost, we have only evaluated AD medications through the public health system, and they can be purchased at pharmacies with a prescription. Thus, it is possible that the prescription pattern can be different in the state of RS. However, if we consider the economic difficulties of our country, we expected that, in relation to the treatment of AD, the less developed regions of the state would in fact be the ones that depended most on public health. We found the opposite, suggesting that the process of diagnosis and treatment of less developed regions was more determinant of the pattern we found. In addition, as we obtained the data from records of deferred processes filled in by prescribing physicians, it is possible that some information was recorded incorrectly. Finally, we were unable to assess the race/ethnicity of the patients, as this information was not available in the database. This assessment could have added additional perspective on the disparity.

In conclusion, we showed that the pattern of prescription of AD medications by the public health system in the state of RS, Brazil is uneven and more socioeconomically developed regions have higher frequency of prescriptions. Assessing the roots of this disparity can lead to public policy changes aiming to improve diagnosis and treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease here and abroad.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by [M.M.], [A.L.B.] and [R.M.C]. R codes were developed and implemented by [A.B.]. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [M.M.] and [R.M.C]; and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos (FIPE), Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre [grant number 2021-0067].

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: Andrei Bieger was omitted from the author list in the original version of this Article. Full information regarding the correction made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/29/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-023-41252-9

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-36604-4.

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. (2022) 7:e105–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M, Holstege H, Chételat G, Teunissen CE, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2021;397:1577–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32205-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehret MJ, Chamberlin KW. Current practices in the treatment of alzheimer disease: Where is the evidence after the phase III trials? Clin Ther. 2015;37:1604–16. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.05.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa, A.F., Picon, P.D., Amaral, K.M., Chaves, M.L.F. Protocolo clínicos e diretrizes terapêuticas. [cited 2023 Jan 19]. Available from: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/protocolos_clinicos_diretrizes_terapeuticas_v1.pdf

- 5.Protocolos Clínicos e Diretrizes Terapêuticas. [cited 2022 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/pcdt/arquivos/2020/portaria-conjunta-13-pcdt-alzheimer-atualizada-em-20-05-2020.pdf

- 6.Picon PD, Camozzato AL, Lapporte EA, Picon RV, Moser Filho H, Cerveira MO, et al. Increasing rational use of cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease in Brazil: Public health strategy combining guideline with peer-review of prescriptions. Int. J. Technol. Assess Health Care. 2010;26:205–10. doi: 10.1017/S0266462310000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almeida-Brasil, C.C., Costa J. de O, Aguiar, V.C.F.D.S., Moreira, D.P., Moraes E.N. de, Acurcio. F. de A, et al. Access to medicines for Alzheimer’s disease provided by the Brazilian Unified national health system in minas Gerais State, Brazil]. Cad. Saude Publica. (2016) 32:e00060615. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Zilkens RR, Duke J, Horner B, Semmens JB, Bruce DG. Australian population trends and disparities in cholinesterase inhibitor use, 2003 to 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:310–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausner L, Frölich L, Gardette V, Reynish E, Ousset P-J, Andrieu S, et al. Regional variation on the presentation of alzheimer’s disease patients in memory clinics within Europe: Data from the ICTUS Study. J Alzheimers Dis. IOS Press. 2010;21:155–65. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilligan AM, Malone DC, Warholak TL, Armstrong EP. Racial and ethnic disparities in alzheimer’s disease pharmacotherapy exposure: An analysis across four state medicaid populations [Internet] Am. J. Geriat. Pharmacother. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura AE, Opaleye D, Tani G, Ferri CP. Dementia underdiagnosis in Brazil. Lancet. 2015;385:418–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Moraes FS, de Souza MLC, Lucchetti G, Lucchetti ALG. Trends and disparities in the use of cholinesterase inhibitors to treat Alzheimer’s disease dispensed by the Brazilian public health system—2008 to 2014: A nation-wide analysis. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2018;76:444–51. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x20180064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kochhann R, Varela JS, de LisboaM CS, Chaves MLF. The mini mental state examination: Review of cutoff points adjusted for schooling in a large Southern Brazilian sample. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2010;4:35–41. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642010DN40100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maia ALG, Godinho C, Ferreira ED, Almeida V, Schuh A, Kaye J, et al. Aplicação da versão brasileira da escala de avaliação clínica da demência (Clinical Dementia Rating—CDR) em amostras de pacientes com demência [Internet] Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2006 doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2006000300025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Informações em Saúde (TABNET) [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 24]. Available from: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/menu_tabnet_php.htm

- 18.Atlas Brasil [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 24]. Available from: http://www.atlasbrasil.org.br/

- 19.Médicos Ativos [Internet]. Conselho regional de medicina do estado do rio grande do sul. CREMERS; 2019 [cited 2022 Nov 24]. Available from: https://cremers.org.br/medicos-ativos/

- 20.Cooper C, Blanchard M, Selwood A, Livingston G. Antidementia drugs: Prescription by level of cognitive impairment or by socio-economic group? Aging Ment. Health. 2010;14:85–9. doi: 10.1080/13607860902918256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnell K, Weitoft GR, Fastbom J. Education and use of dementia drugs: A register-based study of over 600,000 older people. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2008;25:54–9. doi: 10.1159/000111534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giebel, C., Cations, M., Draper, B., Komuravelli, A. Ethnic disparities in the uptake of anti-dementia medication in young and late-onset dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. Cambridge University Press:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Matthews FE, McKeith I, Bond J, Brayne C, Cfas MRC. Reaching the population with dementia drugs: What are the challenges? Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2007;22:627–31. doi: 10.1002/gps.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abner EL, Jicha GA, Christian WJ, Schreurs BG. Rural-urban differences in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders diagnostic prevalence in Kentucky and West Virginia. J. Rural Health. 2016;32:314–20. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohlken J, Selke GW, van den Bussche H. Antidementivaverordnungen in stadt und land—ein vergleich zwischen ballungszentren und flächenstaaten in deutschland. Psychiatr. Prax. Georg. Thieme Verlag KG. 2011;38:232–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1266020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hessmann P, Dodel R, Baum E, Müller MJ, Paschke G, Kis B, et al. Use of antidementia drugs in German patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018;33:103–10. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.César KG, Brucki SMD, Takada LT, Nascimento LFC, Gomes CMS, Almeida MCS, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia and dementia in tremembé Brazil. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2016;30:264–71. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrera E, Caramelli P, Silveira ASB, Nitrini R. Epidemiologic survey of dementia in a community-dwelling Brazilian population [Internet] Alzheimer Disease Assoc. Disord. 2002 doi: 10.1097/00002093-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de JaegerB B, Oliveira ML, Castilhos RM, Chaves MLF. Tertiary center referral delay of patients with dementia in Southern Brazil: Associated factors and potential solutions. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2021;15:210–215. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642021dn15-020008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.