Abstract

Objective

Sufficient vitamin D status during infancy is important for child health and development. Several initiatives for improving vitamin D status among immigrant children have been implemented in Norway. The present study aimed to evaluate the vitamin D status and its determinants in children of immigrant background in Oslo.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Child health clinics in Oslo.

Subjects

Healthy children with immigrant background (n 102) aged 9–16 months were recruited at the routine one-year check-up from two child health clinics with high proportions of immigrant clients. Blood samples were collected using the dried blood spot technique and analysed for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (s-25(OH)D) concentration using LC–MS/MS.

Results

Mean s-25(OH)D was 52·3 (sd 16·7) nmol/l, with only three children below 25 nmol/l and none below 12·5 nmol/l. There was no significant gender, ethnic or seasonal variation in s-25(OH)D. However, compared with breast-fed children, s-25(OH)D concentration was significantly higher among children who were about 1 year of age and not breast-fed. About 38 % of the children were anaemic, but there was no significant correlation between s-25(OH)D and Hb (Pearson correlation, r=0·1, P=0·33).

Conclusions

Few children in the study had vitamin D deficiency, but about 47 % of the children in the study population were under the recommended s-25(OH)D sufficiency level of ≥50 nmol/l.

Keywords: Vitamin D, Hb, Children with immigrantbackground, Dried blood spot, Breast-feeding

Vitamin D is important for Ca absorption. Young children grow fast and have a high demand for Ca to build their skeleton. The classical outcome of severe vitamin D deficiency in children is rickets( 1 ). Vitamin D deficiency is far more prevalent among immigrants in Norway than among ethnic Norwegians( 2 – 4 ). In 2004–2006, we conducted a cluster randomized intervention study among children of non-Western immigrant background in Norway. The intervention provided free vitamin D drops at the ages of 6 weeks and 3 months, as well as information material in various languages about the importance of vitamin D and instructions for how the drops should be given to the infants. Blood samples were taken from the children and the vitamin D content in the blood was measured. Serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (s-25(OH)D) increased substantially more (28 nmol/l) in children who had received free vitamin D drops and whose mothers had received customized information compared with the control group that received standard care at the child health clinics( 5 ). Some of the children were also followed up at 8 months of age, which revealed that s-25(OH)D remained at a high level (data not published). Vitamin D supplementation is particularly important during the first 6 months, especially because exclusive breast-feeding is recommended during these months and the levels of vitamin D found in breast milk are not sufficient to meet the child’s needs.

Based on the positive results of the intervention study, the Norwegian Directorate of Health introduced in 2009 a nationwide package programme that provides free distribution of vitamin D drops to all infants of non-Western immigrant background and information material on vitamin D for their parents, available in six different languages. The package is available until the children reach 6 months of age (one bottle of vitamin D drops at the 6-week control and one bottle at the 3-month control), after which the parents are encouraged to continue the supplementation on their own. In addition, infant formula and most baby cereals are fortified with vitamin D. Given these measures for improving vitamin D status among immigrant children, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the vitamin D status of 1-year-old children of immigrant background in Oslo.

Material and methods

The Norwegian Directorate of Health recommends screening for anaemia in all Norwegian children of non-Western immigrant background at the routine one-year check-up. The first stage is to test Hb values for all children. Those with Hb<11 g/dl are referred to their doctors for further investigation. We wanted to utilize this existing, routine practice for recruiting children to the present study. After contacting all potential child health clinics in Oslo, we found out that a few with high proportions of immigrant clients did comply with the screening for anaemia. Of the three identified clinics, one declined to participate in our study due to inconvenience. We included, therefore, two clinics with high proportions of immigrant clients who agreed to participate.

The public health nurses at the child health clinics were requested to invite all mothers of immigrant background (Africa, Asia and Middle East) who brought their children for a routine one-year check-up to participate with their child in the study. Those willing to participate signed a form of consent and were included in the study. For those who declined to participate, the reasons for not participating should have been noted but that did not materialize. The study was conducted between February and September 2015 in Oslo, Norway.

Data collection

Background information about the infants, including breast-feeding practices, introduction of complementary feeding and current use of vitamin D and other vitamin/mineral supplements, was collected by public health nurses using a short interviewer-administered questionnaire. Generally, the public health nurses knew the mothers and were confident completing the questionnaire without using interpreters.

Dried blood spot and vitamin D analysis

Capillary blood was collected after the fingertip was pierced, using an automated lancet. The first drop of blood was removed with a sterile cotton swab. Next, blood was collected for Hb measurement and then a few blood drops were applied directly on to the sampling filter card within pre-marked circles. The sample cards were then air dried for 2 h and thereafter stored in low-gas-permeable zip-lock bags with desiccant packages. Samples were kept refrigerated and delivered to Vitas AS in Oslo (www.vitas.no) for analysis. Serum concentrations of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (s-25(OH)D3) were quantified using LC–MS/MS. Punches from the dried blood spots (DBS) were added to water, shaken, and diluted with 2-propanol containing the internal standard 26,27-[2H]6-labelled 25(OH)D3. After mixing and centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to an insert and centrifuged again, and an aliquot of 100 μl was injected into the HPLC system. HPLC was performed with an Agilent 1260/1290 liquid chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alta, CA, USA) interfaced by atmospheric pressure chemical ionization to an Agilent mass spectrometric detector operated in Multiple Reaction Monitoring mode. Vitamin D analogues were separated on a 4·6 mm×150 mm reversed-phase column with 2·7 μm particles. The column temperature was 20°C. A one-point calibration curve was made from analysis of DBS calibrators with known vitamin D concentrations. The LC–MS/MS DBS method was internally validated. The intra- and inter-assay CV were 11·1 and 4·0 %, respectively. The detection limit was 5 nmol/l. The analysis refers only to s-25(OH)D3, but in the text we have used s-25(OH)D. The LC–MS/MS DBS method was chosen as a minimally invasive and convenient technique for paediatric research participants. The laboratory performing the analysis is part of the Vitamin D Quality Assessment Scheme (DEQAS) and is compliant.

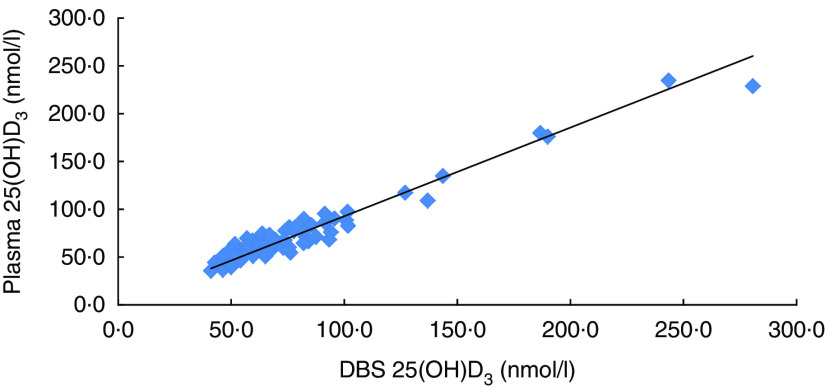

The DBS assay for 25(OH)D has been fully validated according to the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency guidelines for validation of bioanalytical methods( 6 ) and included specificity, precision, accuracy, matrix effects and DBS stability at 25 and 50°C (see online supplementary material). As a part of the validation, a comparison between DBS and the corresponding plasma from seventy-eight human volunteers was performed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Correlation of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (25(OH)D3) in plasma and dried blood spots (DBS) in seventy-eight samples: y=0.8491x+7.7529

To measure Hb concentration, a HemoCue system was used in the two child health clinics. The concentration of Hb was recorded on the study questionnaire by the nurse. The HemoCue was calibrated daily using the calibration cuvette provided by the manufacturer. Anaemia was defined as Hb concentration<11 g/dl for children( 7 ).

A universal standard for the normal range of s-25(OH)D does not exist; however, we chose to use the commonly used cut-off points with respect to which vitamin D status is classified as severely deficient (<12·5 nmol/l), moderately deficient (12·5–25·0 nmol/l), mildly deficient (25–49·9 nmol/l) and sufficient (>50 nmol/l). Serum concentrations below 25 nmol/l are often accompanied by elevated levels of parathyroid hormone and disturbances in Ca homeostasis and bone mineralization, and are therefore frequently considered as beyond the cut-off for vitamin D deficiency( 8 – 10 ).

Statistical methods

Analysis of the data was performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 22. Descriptive statistics are presented as means and sd. To compare the mean s-25(OH)D concentrations according to explanatory variables, we used an independent-sample t test (two-tailed) and one-way ANOVA. The relationships between s-25(OH)D and potentially associated variables were tested primarily using linear regression models.

Ethical clearance

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (study code: 2014/408). All parents gave written informed consent for participation in the study.

Results

A total of 102 children with a mean age of 12·5 months were included in the study, but samples were not available from two of the children because their samples were spoiled when the blood drops were applied within the pre-marked circles on the sampling filter card. Characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population of healthy children with non-Western immigrant background (n 102), Oslo, Norway, February–September 2015

| Age (months), mean and min–max | 12·5 | 9·3–16·1 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n and % | ||

| Girls | 55 | 55 |

| Boys | 47 | 45 |

| Ethnic background, n and % | ||

| Africa | 31 | 30 |

| Asia | 34 | 33 |

| Middle-East | 26 | 26 |

| Others* | 11 | 11 |

| Vitamin D supplements, % and n | ||

| Yes | 94 | 92 |

| No | 8 | 8 |

| Proportion currently breast-feeding, % and n | 50 | 49 |

| Proportion formula-feeding, % and n | 56 | 57 |

| Season blood taken, % and n | ||

| April–September | 64 | 64 |

| February–March | 36 | 36 |

| s-25(OH)D (nmol/l), mean and sd † | ||

| Total | 52·3 | 16·3 |

| Girls | 51·5 | 17·2 |

| Boys | 53·2 | 17·2 |

| Hb (g/dl), mean and sd | ||

| Total | 11·3 | 1·1 |

| Girls | 11·2 | 1·1 |

| Boys | 11·3 | 1·1 |

s-25(OH)D, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

Including Turkey, Kosovo.

Range=22–109 nmol/l.

Feeding practices

Fifty per cent of the children were currently breast-fed and 56 % used infant formula (Table 1). Furthermore, 30 % were currently using cow’s milk/milk products, about 62 % of the children were introduced to solid food at the age of 4 months while 34 % were introduced between the age of 5 and 6 months. The majority of the children (84 %) ate porridge/gruel and over 86 % ate fruits and vegetables every day. The mothers reported that about 20 % of the children ate fatty fish daily.

Supplements

The majority of the children (94 %) took vitamin D-containing supplements and only three children had never used vitamin D-containing supplements. Among those taking D-containing supplements, 82 % took the supplement daily. Most of the children took either vitamin D drops (42%) or cod-liver oil (47%; Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage using vitamin D-containing supplements among the study population of healthy children with non-Western immigrant background (n 94)*, Oslo, Norway, February–September 2015

| Frequency | Vitamin D drops† | Cod-liver oil | Other vitamin D-containing supplements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | 34 | 40 | 3 |

| 4–6 times/week | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| 1–3 times/week | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Total | 42 | 47 | 5 |

Only children who used vitamin D supplementation are included.

The drops are oil based and contain cholecalciferol (vitamin D3).

Vitamin D status

Children’s s-25(OH)D concentration ranged from 22 to 109 nmol/l, with a mean of 52·3 (sd 16·7) nmol/l. For infants sampled in April–September and February–March, the mean concentration of s-25(OH)D was 52 (sd 15·2) and 53 (sd 18·3) nmol/l, respectively, and did not vary significantly with season (P=0·70). As shown in Table 3, only three children had s-25(OH)D concentration below 25 nmol/l, while 50 % of children had s-25(OH)D concentration above 50 nmol/l. Six per cent of the participants had deficiency according to the US Institute of Medicine definition (25(OH)D<30 nmol/l). Concentration of s-25(OH)D did not differ significantly with respect to the variables gender, age and ethnic background (data not shown).

Table 3.

Vitamin D status based on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (s-25(OH)D) concentration among the study population of healthy children with non-Western immigrant background (n 100), Oslo, Norway, February–September 2015

| s-25(OH)D cut-off (nmol/l) | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe deficiency | >12·5 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate deficiency | 12·5–25·0 | 3* | 3 |

| Mild deficiency | 25–49·9 | 47 | 47 |

| Sufficient | >50 | 50 | 50 |

s-25(OH)D range=22–24 nmol/l.

Feeding practices and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D

Mean s-25(OH)D concentration was significantly higher among children who were currently not breast-fed (55·7 (sd 15·6) nmol/l) compared with those currently breast-fed (48·6 (sd 16·4) nmol/l; P<0·001). All three children with s-25(OH)D<25 nmol/l were currently breast-fed.

Hb

The mean Hb concentration was 11·3 (sd 1·1) g/dl. Approximately 38 % (40 % of girls and 36 % of boys) of the children were anaemic (Hb<11 g/dl; Table 4). There was no significant correlation between s-25(OH)D and Hb (Pearson correlation, r=0·1, P=0·33).

Table 4.

Hb levels among the study population of healthy children with non-Western immigrant background (n 102), Oslo, Norway, February–September 2015

| Hb value (g/dl) | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe deficiency | <7 | 0 | 0·0 |

| Moderate deficiency | 7·0–9·9 | 17 | 16·6 |

| Mild deficiency | 10–10·9 | 22 | 21·6 |

| Non-anaemic | ≥11 | 63 | 61·8 |

Discussion

In this sample of 1-year-old children with non-Western immigrant background living in Oslo, mean s-25(OH)D concentration was 52·3 nmol/l, which is higher than what we observed previously among 6-week-old infants of immigrant background (mean concentration of 41·7 nmol/l)( 2 ). Only three children had a s-25(OH)D concentration less than 25 nmol/l. There are limited data on vitamin D status among children in Norway, but our results are similar to those observed in a study of 1-year-old ethnic Norwegian children that was conducted in Oslo from April to June 2000 (n 249)( 10 ).

In Norway, exclusive breast-feeding for 6 months and vitamin D supplementation (10 µg/d) from the age of 4 weeks are recommended. A scheme of free vitamin D drops for all Norwegian infants of non-Western immigrant background until 6 months of age is in place. Although we have not calculated the vitamin D intake of the children, over 90 % of the children reported taking vitamin D supplements. The majority reported taking supplements daily, indicating that the official recommendations are followed.

There is, at present, no common consensus as to which levels should be regarded as optimal with regard to health( 8 , 11 – 13 ). In accordance with the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations, the Norwegian Directorate of Health recommends that serum 25(OH)D concentrations, in the population in general and including in infants and children, should be maintained at 50 nmol/l( 14 ). This cut-off point is also suggested by the US Institute of Medicine and others as well( 11 , 12 ). We found that nearly 50 % of children included in the present study, regardless of season, had s-25(OH)D concentration below 50 nmol/l. Low vitamin D status may have negative consequences for the skeletal development of young children. However, clinical signs of vitamin D deficiency, such as rickets, are rarely seen in Norway today. We have recently carried out a nationwide register-based cohort study of nutritional rickets in Norway showing that nutritional rickets is rare in the Norwegian population. Although nearly all cases had non-Western immigrant background, the number of children with rickets was also low in these groups( 15 ). Apart from rickets, the other health consequences of low vitamin D status in these age groups are poorly described.

Various factors that contribute to the increased risk for vitamin D deficiency in children of non-Western immigrant background have been documented, such as prolonged breast-feeding, consumption of cow’s milk, poor diet, low intake of vitamin D-enriched formula milk, high degree of skin pigmentation and low intake of vitamin D supplements or fortified foods( 13 , 16 – 20 ). The WHO recommends exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months of life and introduction of complementary food after 6 months along with continued breast-feeding up until 2 years( 21 ). In the current study, the proportion of partially breast-fed children at 1 year was 50 % while about 46 % of ethnic Norwegian children are still breast-fed at 1 year( 22 ). In the WHO European Region, the proportion of continued breast-feeding at 1 year varies from 1 to 78 %( 23 ).

In our study three children had s-25(OH)D below 25 nmol/l. All were 12 months old and currently breast-fed, and two of them were not taking any vitamin D supplements. Only prolonged breast-feeding was associated with vitamin D status in the present study. Non-breast-fed children had 7·1 nmol/l higher s-25(OH)D concentration than those currently breast-fed. According to the Norwegian regulations infant formula and cereal-based baby foods for infants and young children should be fortified with vitamin D (1·1 µg/418 kJ (100 kcal)) and Fe (1–3 mg/418 kJ (100 kcal)). In our study, over 50 % of the children were reported to consume infant formula and 84 % to consume cereal-based porridges daily. We have not measured the amount of cereal-based products consumed by the children daily and therefore could not estimate the contribution of baby food to vitamin D intake, but among 12-month-old ethic Norwegian infants who were not breast-fed infant formulas contributed 16 % of the intake of vitamin D( 24 ). Other sources of vitamin D in the Norwegian diet are fatty fish. About 20 % of our study children reported consuming fatty fish daily; this is similar to what is reported among ethnic Norwegian children where 22 % eat fatty fish daily, but the mean intake is only 0·4 g/d. We believe this will not contribute much to the vitamin D intake of the children.

Non-modifiable factors, such as ethnicity and skin pigmentation, did not appear to explain the observed difference. Similar high prevalence of low s-25(OH)D concentration has been observed among breast-fed 1-year-old ethnic Norwegian children, where 34 % of the children had levels below 50 nomol/l( 10 ). Comparable results were found among Danish infants, of whom 53 % were partly breast-fed at 9 months( 25 ). In this context, Ca intake is important and although we have not calculated the Ca intake of the children in the present study, results from a recent study found that the median daily Ca intake was 777 mg in Norwegian-Somali and 633 mg Norwegian-Iraqi infants, which is in accordance with Norwegian dietary recommendations. The same study revealed that vitamin D supplements and fortified infant formula are frequently used( 26 ).

Strengths and limitations of the study

A strength of the current study is that the data were collected by public health nurses as part of their existing routines. Drawing blood samples from young children is always difficult, so to avoid additional discomfort for children and a high workload for the nurses, we utilized the existing, routine blood collection at the child health clinics. By using the DBS method, we were able to collect the blood sample simultaneously with the collection of blood for Hb concentration determination. DBS is a minimally invasive means of obtaining s-25(OH)D measurements, particularly in blood handling, sample storage and transport. However, DBS requires proper training. DBS has been found to be suitable for the status determination of 25(OH)D and the DBS assay for 25(OH)D has been fully validated according to international guidelines. Due to assay variability, it might be difficult to differentiate the categories of mild or moderate deficiency. However, the analysis was done in one batch by means of LC–MS/MS, which is considered the gold standard assay, and Vitas AS complies with international standardization efforts.

The present study has several limitations. First, the recruitment took place at only two of the child health clinics. We hence lack information about vitamin D status and the status of routine distribution of vitamin D drops at other child health clinics. However, according to the public health nurses, very few mothers declined to participate and children of diverse ethnic backgrounds, which reflect the district’s immigrant population, were included. Second, to make the study feasible and demand as little extra effort from the nurses as possible, we included only a short questionnaire. Therefore, we could not calculate the intake of vitamin D and Ca. We also did not collect information about sun exposure and time spent outdoors, which are factors that previous studies have identified as affecting s-25(OH)D concentrations in children. The validation data show that performing the analysis of s-25(OH)D in whole blood and converting this to serum values returns results comparable to values obtained by direct analysis of serum from the same subjects. The conversion does, however, rely on a normal haematocrit in the subjects. In the case of a very high or low haematocrit, the calculation of the serum values will be somewhat less accurate.

We found that approximately 37 % of the children in the present study had anaemia, but none of the children had severe anaemia. These results are similar to those from a previous Norwegian study, where the proportion of Norwegian children aged 12 months with anaemia (Hb<11 g/dl) was 39 %( 27 ). According to the Norwegian regulations, infant formula and cereal-based baby foods for infants and young children should be fortified with Fe (1–3 mg/418 kJ (100 kcal)). As mentioned above, it was reported that the majority of the children consume infant formula and porridges, but we cannot estimate the contribution of these commodities to the Fe status of the children. However, improved Fe status among Icelandic infants (6–12-month-olds) was explained by consumption of Fe-fortified foods such as infant porridges and Fe-fortified formulas( 28 ). We have used the HemoCue system, which is the method generally recommended for use in surveys to determine the population prevalence of anaemia. However, results from studies among children have been inconclusive regarding assessments of Hb concentrations in capillary blood and in venous blood. Some studies found that Hb concentrations in capillary blood are lower than concentrations in venous blood when analysed with the same method( 29 ), while others showed that Hb concentrations in capillary blood from HemoCue measurements are higher than assessments of Hb concentrations in venous blood( 30 ). However, Hb determined by the HemoCue method is comparable to that determined by the other methods( 31 ). Although the HemoCue system used for Hb determination was standardized, we did not measure other Fe parameters and did not correct for haematocrit content; therefore the results should be used carefully. Young children are particularly vulnerable to the effects of Fe deficiency because the first 3 years of life is a period of rapid growth and development of the brain and nervous system. Therefore, a package of public health measures addressing all aspects of anaemia is needed.

Conclusion

None of the children in the present study had severe vitamin D deficiency, but almost half of the children in the study population were under the recommended s-25(OH)D sufficiency level of ≥50 nmol/l. Vitamin D supplementation and prolonged breast-feeding appeared to be the strongest explanatory factors for the observed difference in s-25(OH)D concentrations, suggesting that targeted interventions to improve vitamin D supplementation among immigrant children beyond the first half-year of life may be successful at increasing the vitamin D status of non-Western immigrant children.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank all the mothers, the public health nurses and Vigdis Brit Skulberg, Kari Andreassen and Kirsten Berge from the Agency for Health, Oslo municipality, for their help with the study. They also thank Christina Brux for language editing and proofreading of this manuscript. Financial support: None of the authors’ research is supported by industry and this study was supported by the Norwegian Health Directorate. The Norwegian Health Directorate had no influence on the performance of the trial, analysis of the data, writing, or the publication of the results. Conflict of interest: T.E.G. and A.M.H. work at Vitas AS. T.E.G. is a CEO of the contract laboratory Vitas AS (www.vitas.no), where he also is a stock owner. Authorship: A.A.M. and H.E.M. planned the study. A.A.M. carried out the data collection, performed data analysis and prepared the manuscript. A.M.H. performed the analysis of DBS samples. H.E.M. and T.E.G. commented on the draft, contributed to the interpretation of the findings and approved the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (study code: 2014/408). All parents gave written informed consent for participation in the study.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001700180X.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Heaney RP (2003) Long-latency deficiency disease: insights from calcium and vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr 78, 912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Madar AA, Stene LC & Meyer HE (2009) Vitamin D status among immigrant mothers from Pakistan, Turkey and Somalia and their infants attending child health clinics in Norway. Br J Nutr 101, 1052–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holvik K, Meyer HE, Haug E et al. (2005) Prevalence and predictors of vitamin D deficiency in five immigrant groups living in Oslo, Norway: the Oslo Immigrant Health Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 59, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eggemoen AR, Knutsen KV, Dalen I et al. (2013) Vitamin D status in recently arrived immigrants from Africa and Asia: a cross-sectional study from Norway of children, adolescents and adults. BMJ Open 3, e003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Madar AA, Klepp KI & Meyer HE (2009) Effect of free vitamin D2 drops on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in infants with immigrant origin: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr 63, 478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zimmer D (2014) New US FDA draft guidance on bioanalytical method validation versus current FDA and EMA guidelines: chromatographic methods and ISR. Bioanalysis 6, 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization (2008) Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005. http://www.who.int/vmnis/publications/anaemia_prevalence/en (accessed May 2017).

- 8. Lips P (2004) Which circulating level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is appropriate? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 89–90, 611–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Braegger C, Campoy C, Colomb V et al. (2013) Vitamin D in the healthy European paediatric population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 56, 692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holvik K, Brunvand L, Brustad M et al. (2008) Vitamin D status in the Norwegian population. Solar Radiat Hum Health, 216–228. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ross AC (2011) The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Public Health Nutr 14, 938–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pearce SH & Cheetham TD (2010) Diagnosis and management of vitamin D deficiency. BMJ 340, 5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mithal A, Wahl DA, Bonjour JP et al. (2009) Global vitamin D status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos Int 20, 1807–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nordic Council of Ministers (2013) Nordic Nutrition Recommendations. http://www.ravitsemusneuvottelukunta.fi/files/images/vrn/9789289326292_nnr-2012.pdf (accessed May 2017).

- 15. Meyer HE, Skram K, Berge IA et al. (2017) Nutritional rickets in Norway: a nationwide register-based cohort study. BMJ Open 7, e015289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greer FR (2008) 25-Hydroxyvitamin D: functional outcomes in infants and young children. Am J Clin Nutr 88, issue 2, 529S–533S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clemens TL, Adams JS, Henderson SL et al. (1982) Increased skin pigment reduces the capacity of skin to synthesise vitamin D3 . Lancet 1, 74–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carpenter TO, Herreros F, Zhang JH et al. (2012) Demographic, dietary, and biochemical determinants of vitamin D status in inner-city children. Am J Clin Nutr 95, 137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hintzpeter B, Scheidt-Nave C, Muller MJ et al. (2008) Higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency is associated with immigrant background among children and adolescents in Germany. J Nutr 138, 1482–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maguire JL, Birken CS, O’Connor DL et al. (2011) Prevalence and predictors of low vitamin D concentrations in urban Canadian toddlers. Paediatr Child Health 16, e11–e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization (2003) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42590/1/9241562218pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (accessed May 2017).

- 22. Kristiansen AL, Lande B, Overby NC et al. (2010) Factors associated with exclusive breast-feeding and breast-feeding in Norway. Public Health Nutr 13, 2087–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bagci Bosi AT, Eriksen KG et al. (2016) Breastfeeding practices and policies in WHO European Region Member States. Public Health Nutr 19, 753–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lande B & Frost Andersen L (2005) Spedkost 12 måneder. Landsomfattende kostholdsundersøkelse blant spedbarn i Norge. IS-1248. Oslo: Sosial- og helsedirektoratet. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ostergard M, Arnberg K, Michaelsen KF et al. (2011) Vitamin D status in infants: relation to nutrition and season. Eur J Clin Nutr 65, 657–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grewal NK, Andersen LF, Sellen D et al. (2016) Breast-feeding and complementary feeding practices in the first 6 months of life among Norwegian-Somali and Norwegian-Iraqi infants: the InnBaKost survey. Public Health Nutr 19, 703–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hay G, Sandstad B, Whitelaw A et al. (2004) Iron status in a group of Norwegian children aged 6–24 months. Acta Paediatr 93, 592–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thorisdottir AV, Thorsdottir I & Palsson GI (2011) Nutrition and iron status of 1-year olds following a revision in infant dietary recommendations. Anemia 2011, 986303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moe PJ (1970) Hemoglobin, hematocrit and red blood cell count in ‘capillary’ (skin-prick) blood compared to venous blood in children. Acta Paediatr Scand 59, 49–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boghani S, Mei Z, Perry GS et al. (2017) Accuracy of capillary hemoglobin measurements for the detection of anemia among US low-income toddlers and pregnant women. Nutrients 9, 253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nkrumah B, Nguah SB, Sarpong N et al. (2011) Hemoglobin estimation by the HemoCue® portable hemoglobin photometer in a resource poor setting. BMC Clin Pathol 11, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001700180X.

click here to view supplementary material