Abstract

Objective

Evidence suggests that health benefits are associated with consuming recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables (F&V), yet standardised assessment methods to measure F&V intake are lacking. The current review aims to identify methods to assess F&V intake among children and adults in pan-European studies and inform the development of the DEDIPAC (DEterminants of DIet and Physical Activity) toolbox of methods suitable for use in future European studies.

Design

A literature search was conducted using three electronic databases and by hand-searching reference lists. English-language studies of any design which assessed F&V intake were included in the review.

Setting

Studies involving two or more European countries were included in the review.

Subjects

Healthy, free-living children or adults.

Results

The review identified fifty-one pan-European studies which assessed F&V intake. The FFQ was the most commonly used (n 42), followed by 24 h recall (n 11) and diet records/diet history (n 7). Differences existed between the identified methods; for example, the number of F&V items on the FFQ and whether potatoes/legumes were classified as vegetables. In total, eight validated instruments were identified which assessed F&V intake among adults, adolescents or children.

Conclusions

The current review indicates that an agreed classification of F&V is needed in order to standardise intake data more effectively between European countries. Validated methods used in pan-European populations encompassing a range of European regions were identified. These methods should be considered for use by future studies focused on evaluating intake of F&V.

Keywords: Fruits and vegetables, Dietary assessment, Europe, DEDIPAC

A poor diet is associated with four major non-communicable diseases: cancer, CVD, diabetes and respiratory disorders( 1 – 4 ), which account for approximately 60 % of deaths globally per annum( 5 ). There is a growing body of research which highlights the benefits of fruit and vegetable (F&V) consumption, including the protective effect of F&V consumption on CVD( 6 , 7 ). The WHO Global Strategy on Diet and Physical Activity has made several key recommendations with respect to dietary intake, including increasing F&V consumption( 8 ). In the 2004 joint report of the FAO/WHO Workshop on Fruit and Vegetables for Health, the WHO outlined a framework for developing interventions to promote adequate consumption of F&V in Member States( 9 ).

However, in order to develop and assess such interventions, and moreover to monitor the consumption of F&V worldwide, reliable and comparable assessment methods are essential( 10 , 11 ). Methodological differences between studies which assess the intake of F&V, including differences in the units of serving size and frequency, and the definition of what constitutes a fruit or vegetable, can often hinder meaningful comparisons( 12 ). As highlighted by Roark et al. ( 12 ), the definition of vegetables poses a particular problem. Debate focuses on whether legumes, pulses and/or potatoes are considered to be vegetables( 10 , 12 ) and whether fruits should include nuts, olives and fruit juices which are 100 % juice( 10 ). While F&V can be defined by their nutritional content as ‘low energy-dense foods, relatively high in vitamins, minerals, and other bioactive compounds as well as being a good source of fibre’( 10 ) (p. 4), there is no agreed understanding of ‘fruit’ or ‘vegetable’ in terms of how they should be captured through dietary assessment methods; that is, what is considered a fruit or vegetable in one country may not be in another. This disparity may create issues when measuring and tracking intake across different regions( 10 ).

Previous and existing European projects have focused on the standardisation and harmonisation of food classification systems and food composition databases between countries (e.g. the International Food Data Systems Project, the Eurofoods initiative, the Food-Linked Agro-Industrial Research programme, COST Action 99, TRANSFAIR study, EUROFIR, etc.)( 11 , 13 – 18 ) and the IDAMES (Innovative Dietary Assessment Methods in Epidemiological Studies and Public Health) project has evaluated new-generation methods to assess dietary intake in Europe( 19 ), developing the European Food Propensity Questionnaire for use within European countries. Guidelines from the European Food Safety Authority recommend the use of a computerised method (e.g. EPIC-SOFT or similar) for collection of accurate, standardised, food consumption data at the European level( 20 , 21 ). However, standards have not, as yet, been developed for the assessment of dietary intake, including intake of F&V, as part of aetiological studies. Thematic Area 1 of the DEDIPAC (DEterminants of DIet and Physical Activity) project( 22 ) aims to address this gap and add to our understanding of the most effective, harmonised methods of dietary intake assessment by preparing a toolkit of the most useful measurement tools of dietary intake that can be used extensively across Europe( 22 , 23 ). The aim of the current systematic literature review was to identify suitable assessment methods that may potentially be used to measure intake of F&V in European children and adults in pan-European studies.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study selection

The current review adheres to the guidelines of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Statement. The protocol for the review can be accessed from PROSPERO (CRD42014012947)( 24 ). A systematic literature search for pan-European studies that assessed the intake of F&V was conducted. For this review, we used the definition of F&V proposed by Agudo( 10 ): ‘vegetables and foods used as vegetables’, with fruits taken to be fresh or preserved fruits. Our definition included nuts, legumes and potatoes, and only 100 % fruit juice was considered a fruit. Legumes and potatoes are not consistently included as vegetables across dietary assessment methods; therefore, where possible, it was reported whether the instrument in question excluded or included these items as vegetables. Two authors, F.R. and K.R., independently conducted a search of PubMed, EMBASE and Web of Science databases, using combinations of the following search terms: ‘fruit/s’ and ‘vegetable/s’, with keywords for dietary intake, including ‘diet’, ‘eating’, ‘consumption’, ‘intake’, and search terms for European countries. A full copy of the EMBASE search strategy is presented in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1. All searches were limited to English-language literature published from 1990 through to 7 July 2014.

Table 1.

Identified instruments according to criteria. Instruments which meet both criteria are shaded

| Study | Countries | Instrument(s) | Validated | >2 countries/country range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | ||||

| Baldini et al. ( 54 ) | 2 (Italy, Spain) | FFQ | X( 53 ) | |

| Baltic project( 55 ) | 3 (Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia) | 24-HDR | ||

| Standardised questionnaire | ||||

| Behanova et al. ( 56 ) | 2 (Slovakia, Netherlands) | FFQ | ||

| CNSHS( 57 , 58 ) | 4 (Germany, Denmark, Poland, Bulgaria) | FFQ | X | |

| ECRHS( 59 ) | 3 (Germany, UK, Norway) | FFQ (based on EPIC-UK and EPIC-Germany FFQ) | X( 59 ) | |

| EHBS( 60 ) | 21 in total | FFQ | X | |

| 17 European countries (Austria, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Scotland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland) | ||||

| ENERGY( 27 ) | 7 (Belgium, Greece, Hungary, Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Spain) | FFQ | X( 28 ) | X |

| EPIC( 18 , 28 , 29 , 61 , 62 ) | 10 (Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, France, Greece, Norway, England) | 24-HDR (EPIC-SOFT) | X( 63 ) | X |

| ESCAREL( 64 ) | 7 (France, Spain, Italy, UK, Finland, Latvia, Estonia) | FFQ | X | |

| Esteve et al. ( 65 ) | 4 (Spain, Italy, Switzerland, France) | Dietary questionnaire | ||

| Finbalt Health Monitor( 66 ) | 4 (Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania) | FFQ | ||

| Finnish and Russian Karelia study( 67 ) (2002 study) | 2 (Russia, Finland) | FFQ | ||

| Food4Me( 51 , 53 ) | 7 (Ireland, Netherlands Spain, Greece, UK, Poland, Germany) | FFQ (web-based) | X( 52 , 53 ) | X |

| ‘Food in later life’ project( 68 ) | 8 (Denmark, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK) | 7 d non-weighed food diaries | X | |

| Galanti et al. ( 69 ) | 2 (Sweden, Norway) | FFQ | ||

| North/South Food Consumption Survey( 45 , 81 ) | 2 (Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland) | 7 d record | ||

| HAPIEE( 70 )* | 3 (Russia, Poland, Czech Republic) | FFQ | X( 126 , 127 ) | |

| HTT( 71 ) | 9 (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Ukraine) | FFQ | ||

| Hupkens et al. ( 72 ) | 3 (Belgium, Netherlands, Germany) | FFQ | X( 128 ) | |

| I.Family Project( 50 , 73 , 74 ) | 8 (Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | Diet questionnaire (FFQ) which was included as part of the parent questionnaire | X | |

| Online 24-HDR (SACANA) | ||||

| IHBS( 75 ) | 17 (Austria, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Scotland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland) | FFQ | X | |

| IMMIDIET( 76 ) | 3 (Italy, Belgium, England) | EPIC-Italian FFQ | X( 39 , 129 ) | |

| EPIC-UK FFQ | ||||

| Specifically developed Belgian FFQ | ||||

| Kolarzyk et al. ( 48 ) | 4 (Poland, Belarus, Russia, Lithuania) | FFQ | X | |

| LiVicordia( 77 ) | 2 (Lithuania, Sweden) | 24-HDR | ||

| LLH( 71 ) | 8 (Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Ukraine) | FFQ | ||

| MEDIS( 78 ) | 2 (Cyprus, Greece) | FFQ | X( 138 ) | |

| MGSD( 79 ) | 6 (Greece, Italy, Algeria, Bulgaria, Egypt, Yugoslavia (only diabetics in Yugoslavia)) | Dietary history method using questionnaire | X( 79 ) | |

| NORBAGREEN( 41 , 80 ) | 8 (Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Iceland) | FFQ | X( 80 ) | |

| O’Neill et al. ( 82 ) | 5 (UK, Republic of Ireland, Spain, France, Netherlands) | FFQ | X | |

| Parfitt et al. ( 83 ) | 2 (England, Italy) | 5–7 d record | ||

| PRIME( 84 ) | 2 (Northern Ireland, France) | FFQ | X | |

| PRO GREENS( 85 ) | 10 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Finland) | A pre-coded 24-HDR, FFQ (parents) | X | |

| Pro-Children study( 42 , 86 , 87 ) | 9 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden) | A pre-coded 24-HDR, FFQ (parents) | X( 130 ) | X |

| Rylander et al. ( 88 ) | 2 (Sweden, Switzerland) | FFQ | ||

| SENECA( 43 , 44 , 89 , 90 ) | 12 (Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland) | Modified dietary history method comprising a 3 d estimated record and meal-based frequency checklist | X( 89 ) | X |

| Seven Countries Study( 4 , 91 , 92 ) | 7 (Netherlands, Finland, Yugoslavia, Japan, Italy, Greece, USA) | Cross-check dietary history method | X( 131 ) | X |

| European cohorts (n 14) used 7 d records at baseline | ||||

| Terry et al. ( 93 ) | 6 (Germany, France, Canada, Sweden, Australia, USA) | FFQ | ||

| Tessier et al. ( 94 ) | 2 (Malta, Italy) | Open-ended qualitative questionnaire | ||

| ToyBox( 95 – 106 ) | 6 (Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Poland, Spain) | Primary caregiver’s FFQ (PCQ) | X( 100 ) | X |

| Van Diepen et al. ( 107 ) | 2 (Greece, the Netherlands) | 2× consecutive 24-HDR | ||

| WHO-MONICA EC/MONICA Project optional nutrition study( 46 , 108 ) | 9 (Northern Ireland, UK (Cardiff), Denmark, Finland, Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Spain) | 3 d record and 7-d record. One centre used 3× 24-HDR | X | |

| Adolescents | ||||

| Gerrits et al. ( 109 ) | 3 (Netherlands, Hungary, USA) | FFQ | ||

| HBSC( 31 , 110 ) | 37 (England, Norway, Macedonia, Iceland, Netherlands, Portugal, Wales, Italy, Sweden, Latvia, Switzerland, Denmark, Estonia, Scotland, Slovenia, Ukraine, Belgium, Finland, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, Greenland, Russia, Armenia, Austria, Belgium, Spain, France, Romania, Turkey, Czech Republic, Ireland, Luxembourg, Slovakia) | FFQ | X( 132 ) | X |

| HELENA( 32 – 36 , 47 , 111 , 112 ) | 9 (Greece, Germany, Belgium, France, Hungary, Italy, Sweden, Austria, Spain) | 24-HDR HELENA-DIAT (Dietary Assessment Tool) | X( 34 , 35 ) | X |

| 8 countries included for 24-HDR (as above, except Hungary) | Online FFQ | |||

| 5 (Austria, Belgium, Greece, Sweden, Germany) pilot-tested the online FFQ | ||||

| Larsson et al. ( 113 ) | 2 (Sweden, Norway) | FFQ | ||

| Szczepanska et al. ( 114 ) | 2 (Poland, Czech Republic) | FFQ | ||

| TEMPEST( 115 ) | 4 (Netherlands, Poland, UK, Portugal) | FFQ | X | |

| Children | ||||

| Antova et al. ( 116 ) | 6 (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia) | FFQ | ||

| ENERGY( 27 ) | 7 (Belgium, Greece, Hungary, Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Spain) | Questionnaire with FFQ and 24-HDR | X( 133 ) | X |

| EYHS( 30 , 117 ) | 4 (Denmark, Portugal, Estonia, Norway) | 24-HDR, qualitative food record | X† | |

| IDEFICS( 37 , 38 , 135 , 139 , 140 , 145 ) | 8 (Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | CEHQ-FFQ | X( 35 , 38 , 134 , 135 , 140 , 145 ) | X |

| SACINA 24-HDR( 50 ) | ||||

| I.Family Project( 50 ) | 8 (Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | Diet Questionnaire (FFQ) as part of children’s questionnaire | X* | X |

| Online 24-HDR (SACANA) | ||||

| ISAAC Phase II( 40 , 120 ) | 15 (Albania, France, Estonia, Germany, Georgia, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, UK) | FFQ* | X | |

| PRO GREENS( 85 ) | 10 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Finland) | A pre-coded 24-HDR, FFQ | X | |

| Pro-Children study( 42 , 86 , 87 ) | 9 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden) | A pre-coded 24-HDR, FFQ | X( 42 , 136 ) | X |

| ToyBox( 95 – 106 ) | 6 (Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Poland, Spain) | Children’s FFQ | X( 137 )‡ | X |

CNSHS, Cross National Student Health Survey; ECRHS, European Community Respiratory Health Survey; EHBS, European Health and Behaviour Survey; ENERGY, EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; ESCAREL, European Study in Non Carious Cervical Lesions; HAPIEE, Health, Alcohol and Psychosocial factors in Eastern Europe; HTT, Health in Times of Transition; IHBS, International Health and Behaviour Survey; LLH, Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health; MEDIS, MEDiterranean Islands Study; MGSD, Mediterranean Group for the Study of Diabetes; PRIME, Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction; SENECA, Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly; a Concerted Action; MONICA, Multinational MONItoring of trends and determinants in CArdiovascular disease; HBSC, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children; HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; TEMPEST, ‘Temptations to Eat Moderated by Personal and Environmental Self-regulatory Tools’; EYHS, European Youth Heart Study; IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS; ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; 24-HDR, 24h recall; PCQ, Primary Caregiver’s Questionnaire; CEHQ, Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire.

Based on the IDEFICS instruments which were validated.

24-HDR and qualitative 1 d food record method has been validated but not as part of the EYHS.

The reliability study on the FFQ is unpublished.

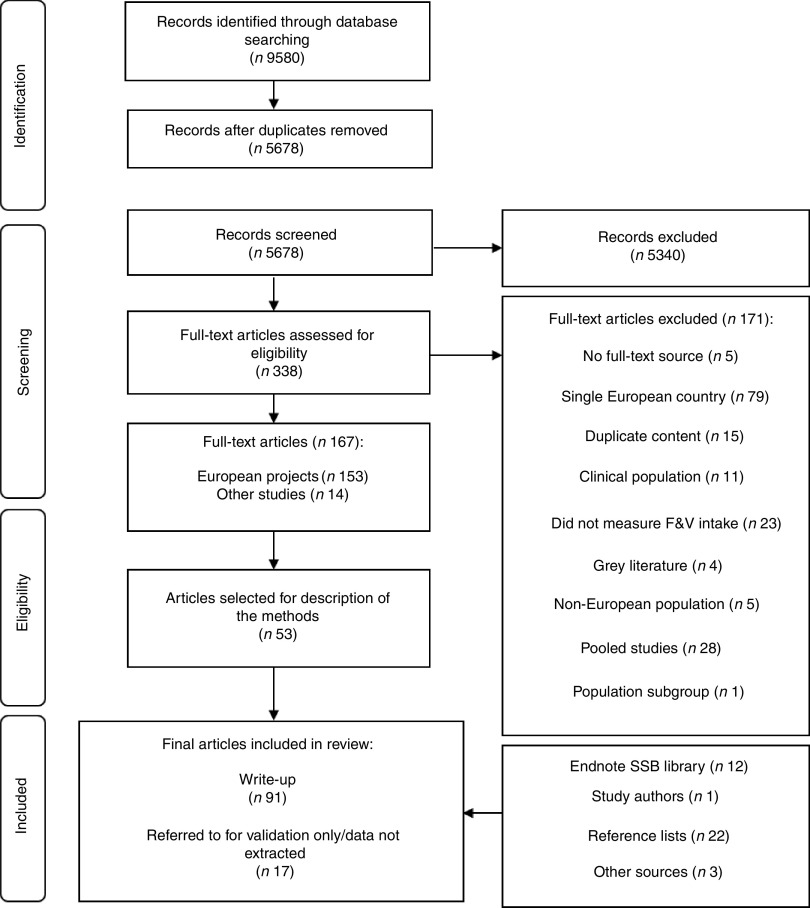

Titles and abstracts of the sourced articles were independently screened by F.R. and K.R. If in doubt regarding inclusion, the article was retained for full-text review. Any disagreement during the full-text review stage was resolved through consultation with a third author, J.M.H. Studies were included if they assessed the intake of F&V within two or more European countries, as defined by the Council of Europe( 25 ). Participants were required to be free-living, healthy populations of any age; therefore we excluded hospital-based populations and studies which focused on a specific disease subgroup (e.g. diabetic cohort) or any fixed societal subgroups (e.g. pregnant women). The review was not limited to certain study designs. If studies compared two groups, one of which was a healthy general population, they were included. Intervention studies were eligible if F&V intake was measured at baseline before any dietary intervention was undertaken. Similarly, case–control studies were included if intake was assessed in population-based controls. Studies were included only if they assessed intake of F&V at the level of the individual; that is, those which assessed household-level consumption of F&V were excluded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing study selection process for the current review (F&V, fruit and vegetable; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverages)

Reference lists of all included papers, along with relevant meta-analysis and literature reviews, were reviewed for further publications not identified by the original search. Databases were also searched using the names of individual European projects listed in the DEDIPAC Inventory of Relevant European Studies, a compilation which is an ongoing part of DEDIPAC. Authors were contacted to obtain full versions of the relevant instruments or questionnaires and some articles; and the Endnote library of a concurrently occurring systematic literature review on methods to assess intake of sugar-sweetened beverages was reviewed for further studies.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was carried out using a form that was developed, piloted and subsequently revised to capture the following data: study design; number and names of European countries involved; sample size (total and number for each country); age range of the included population; the method used and description (including frequency categories for FFQ, number of items/items that referred to F&V, details of portion estimation); mode of administration; and details on the validation or reproducibility. Originally sourced articles which described the assessment methods in the most detail were selected for inclusion in the review, with further information on the methods obtained from articles sourced from reference lists. One reviewer extracted the data for each study, which was confirmed by the other reviewer.

The aim of the current systematic literature review was to identify and describe assessment methods that have been used to assess intake of F&V. Therefore, a comprehensive quality appraisal of each included article was not conducted as part of the current review. However, it was recorded whether or not the instrument in question had been tested for validity and/or reproducibility, and relevant validation studies were referenced where possible. Data were extracted from these studies by P.D., S.E. and N.W.-D. to inform the instrument selection. In order to determine which instruments would be appropriate to use in pan-European studies, two selection criteria were applied: (i) the instrument was reviewed for validity and/or reproducibility, of which a summary of its indicators is presented; and (ii) the instrument was used in more than two countries simultaneously that represented a range of European regions. A ‘range’ meant that at least one country from at least three of the Southern, Northern, Eastern and Western European regions, as defined by the United Nations, were included( 26 ). The results of this selection are shown in Table 1.

Results

Description of the included studies

As shown in Fig. 1, 5678 papers remained once duplicates were removed, and 167 were retained after screening titles and abstracts and following full-text screening. These articles were grouped according to the major European project to which they belonged (n 153) or grouped as ‘Other’ (n 14) if they did not belong to a project. From these 167 articles, fifty-three articles were selected, typically one to three articles per project, which best described the background to the project or the methods used (Fig. 1).

Reviewing the reference lists yielded twenty-two further articles in which the methods were described( 18 , 27 – 47 ). Twelve further articles were obtained from the Endnote library on sugar-sweetened beverages in which two additional studies assessing the intake of F&V, the ToyBox study and a study by Kolarzyk et al. ( 48 ), were described. One article was obtained from authors( 49 ). Unpublished details on the instruments used as part of the I.Family Project( 50 ), the IDEFICS (Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS) study follow-up, were obtained through contact with the IDEFICS group. Articles on the background and validation of the Food4Me project, published after the search dates, were also added to the review( 51 – 53 ) . The term ‘study’ is used in the current review to refer to the larger project, rather than individual analyses/publications that may arise from the same project, and therefore use the same methodology.

Taking together the articles sourced and selected from our original search (n 53), from reference lists (n 22), from the concurrent review on sugar-sweetened beverages (n 12), from authors (n 1) and articles added subsequently (n 3), a total of ninety-one articles covering fifty-one studies were included in the review. For each of the methods identified, article(s) which described the validation or reliability testing performed for that method were recorded. As a result, seventeen further articles were sourced in which validation and/or reliability testing for the identified methods was described. The characteristics of the included studies( 4 , 18 , 27 – 48 , 50 – 145 ) are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the included studies: design, population studied, dietary assessment instruments used and details of validation and/or reproducibility. Studies selected according to the two criteria are shaded. Where validation or reliability data was not available for fruit and vegetables specifically, this is highlighted in bold font

| Study | Design | Population | Countries | Instrument(s) | Validation | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | ||||||

| Baldini et al. ( 54 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/students (n 210) Age range NR | 2 (Italy, Spain) | FFQ | Based on the Willett FFQ Validated against diet records( 124 ) No validation data for F&V | No details‡ |

| Baltic project( 55 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 4571) 19–65 years | 3 (Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia) | 24-HDR Standardised questionnaire | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Behanova et al. ( 56 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 210) 19–64 years | 2 (Slovakia, Netherlands) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| CNSHS( 57 , 58 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/students (n 2651) Age range NR | 4 (Germany, Denmark, Poland, Bulgaria) | FFQ | No test of validity was performed, but the questionnaire was similar to other FFQ that have been validated | |

| ECRHS( 59 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 1174) 30–70 years | 3 (Germany, UK, Norway) | FFQ (based on EPIC-UK and EPIC-Germany FFQ) | German and UK FFQ validated against 24-HDR( 125 , 141 ) The Norwegian FFQ was not assessed for repeatability or validity | Reproducibility of German FFQ obtained by a repeated administration of the FFQ at a 6-month interval( 125 ). Repeatability of the UK FFQ using two assessments separated by an interval of 5–23 months( 59 ) |

| EHBS( 60 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/students (n 7115) 17–30 years | 21 in total 17 European countries (Austria, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Scotland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland) | FFQ† | No details‡ | Reliability of the measures are described( 142 ) but no reliability data on F&V |

| ENERGY( 27 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/parents or guardians (n 6002) Age range NR | 7 (Belgium, Greece, Hungary, Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Spain) | FFQ† | No details‡ | The reliability and content validity of the parent questionnaires were tested separately in all participating countries, in five schools per country using approximately fifty parents per country for the reliability study and twenty parents for the construct validity study (unpublished results) |

| EPIC( 18 , 28 , 29 , 61 – 63 ) | Cohort | Adults (n 519 978) 30–70 years | 10 (Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Germany, Sweden (Malmo)/Sweden (Umea), Denmark, France, Greece, Norway, England) | FFQ†, 24-HDR (EPIC-SOFT) | EPIC-SOFT was validated against biomarkers for F&V consumption( 63 ) Assessed by crude correlations Weak to moderate association between biomarkers and F&V intake | No details‡ |

| ESCAREL( 64 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 3187) 18–35 years | 7 (France, Spain, Italy, UK, Finland, Latvia, Estonia) | FFQ† | Bartlett et al.( 64 ) report that all questionnaires were validated in pilot studies No reference or data available | |

| Esteve et al. ( 65 ) | Case–control | Adults/controls (n 3057) Age range NR | 4 (Spain, Italy, Switzerland, France) | Dietary questionnaire | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Finbalt Health Monitor( 66 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 25 044) 20–64 years | 4 (Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Finnish and Russian Karelia study( 67 ) (2002 study) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 1201) 25–64 years | 2 (Russia, Finland) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| ‘Food in later life project’( 68 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 644) 65–98 years | 8 (Denmark, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, UK) | 7 d non-weighed food diaries | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Food4Me( 51 – 53 ) | Randomised controlled trial | Adults (n 5562) 17–79 years | 7 (Ireland, Netherlands, Spain, Greece, UK, Poland, Germany) | FFQ (web-based) | Validated against 4 d non-consecutive weighed records( 53 ) and by comparing with the validated EPIC-Norfolk FFQ( 52 ) Assessed by crude correlations, energy-adjusted correlations, and mean or median differences in F&V consumption Moderate agreement with 4 d weighed food record | Interval: 4 weeks( 53 ) Assessed by correlations Reproducible for nutrient and food group intake |

| Galanti et al. ( 69 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 440) | 2 (Sweden, Norway) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| HAPIEE( 70 )* | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 28 947) | 3 (Russia, Poland, Czech Republic) | FFQ† | Based on the Whitehall II questionnaire. Validated against a 7 d diet diary and biomarkers of nutrient intake by Brunner et al. ( 126 ). Whitehall II questionnaire was originally developed by Willett et al. ( 127 ) Assessed by energy-adjusted correlations, mean or median differences, and exact level of agreement. Good correlation of intakes estimated by FFQ with biomarkers Overestimation of vitamin C and carotenes by FFQ relative to 7 d diet diary | No details‡ |

| HTT( 71 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 18 000) | 9 (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Ukraine) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Hupkens et al. ( 72 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/women (n 849) | 3 (Belgium, Netherlands, Germany) | FFQ† (based on Netherlands Cohort Study FFQ) | Validated using diet records( 128 ) Assessed by crude correlations, mean or median differences FFQ can rank individuals according to food groups and nutrient intake | No details‡ |

| I.Family Project( 50 , 73 , 74 ) | Prospective cohort study (successor of IDEFICS study) | Adults/parents (n>7000) | 8 (Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | Diet questionnaire as part of the parent questionnaire Online 24-HDR (SACANA) | Similar to validated instruments used in the IDEFICS project | No details‡ |

| IHBS( 75 ) | Cross-national | Adults (n 17 246) | 17 (Austria, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Scotland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| IMMIDIET( 76 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 802) | 3 (Italy, Belgium, England) | EPIC-Italian FFQ† EPIC-UK FFQ† Specifically developed Belgian FFQ | Based on EPIC UK and Italian FFQ which have been validated using weighed diet records( 141 ), biomarkers( 141 , 143 ) and 24-HDR( 143 ). Belgian FFQ validated using 7 d diet records and 24-HDR( 39 , 129 ) Assessed by energy-adjusted correlations, de-attenuated correlation coefficients, and mean or median differences Generally good correlation between FFQ and diet records | No details‡ |

| Kolarzyk et al. ( 48 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/students (n 1517) | 4 (Poland, Belarus, Russia, Lithuania) | FFQ† | Validated and recommended by the National Food and Nutrition Institute in Warsaw, Poland( 49 ) | No details‡ |

| LiVicordia( 77 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/men (n 150) | 2 (Lithuania, Sweden) | 24-HDR | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| LLH( 71 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 18 428) | 8 (Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Ukraine) | FFQ | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| MEDIS( 78 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/elderly (n 1190) | 2 (Cyprus, Greece) | FFQ | Validated using diet records( 138 ) Assessed by crude correlations, mean or median differences and exact level of agreement Moderate agreement for fruit and low agreement for vegetables | Interval: 10–30 d( 138 ) Reproducibility of FFQ is fair |

| MGSD( 79 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 4254) Non-diabetics (n 1833) | 6 (Greece, Italy, Algeria, Bulgaria, Egypt, Yugoslavia (only diabetics in Yugoslavia)) | Dietary history method using questionnaire† | Validated using diet records( 79 ) | No details‡ |

| NORBAGREEN( 41 , 80 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults and adolescents (n 8397) | 8 (Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Iceland) | FFQ† | Validated using 3 d diet records in Finland and four 24-HDR in Lithuania( 80 ) Assessed by crude correlations, mean or median differences, and exact level of agreement FFQ is valid to rank individuals according to F&V intake | Interval: 6–8 months( 80 ) Provides reproducible estimates of food group intake |

| North/South Food Consumption Survey( 45 , 81 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 1379) | 2 (Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland) | 7 d record | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| O’Neill et al. ( 82 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 400) | 5 (UK, Republic of Ireland, Spain, France, Netherlands) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Parfitt et al. ( 83 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/students (n 48) | 2 (England, Italy) | 5–7 d record | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| PRIME( 84 ) | Cohort | Adults (n 8087 used for present study) | 2 (Northern Ireland, France) | FFQ | Not validated against another dietary assessment method. A correlation analysis between the frequency of fruit and/or vegetable intake and plasma vitamins was performed in 100 men to assess the ability of the questionnaire to discriminate large v. small consumers of fruits and vegetables( 84 ) | No details‡ |

| PRO GREENS( 85 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/parents | 10 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Finland) | A pre-coded 24-HDR†, FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Pro-Children study( 42 , 86 , 87 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/parents Number NR | 9 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway Portugal, Spain, Sweden) | A pre-coded 24-HDR†, FFQ† | Validated using 7 d diet records (1 d weighed record and 6 d record using household measures)( 130 ) Assessed by crude correlations, mean or median differences, and exact level of agreement FFQ valid for ranking adults according to usual intake | No details‡ |

| Rylander et al. ( 88 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/women (n 6785) | 2 (Sweden, Switzerland) | FFQ | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| SENECA( 43 , 44 , 89 , 90 ) | Mixed design (longitudinal and cross-sectional) | Adults/elderly (n≈2600) 70–75 years | 12 (Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland) | Modified dietary history method comprising a 3 d estimated record and meal-based frequency checklist | Validated against a 3 d weighed record( 89 ) No validation data for F&V | No details‡ |

| Seven Countries Study( 4 , 91 , 92 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/men (n 12 763 (enrolled)) 40–59 years (at enrolment) | 7 (Netherlands, Finland, Yugoslavia, Japan, Italy, Greece, USA) | Cross-check dietary history method European cohorts (n 14) used 7 d records at baseline | No details‡ | Interval: 3 and 12 months after the initial surveys( 104 ) Small differences in reproducibility estimates |

| Terry et al. ( 93 ) | Case–control | Adults/controls (n 2486) 20–82 years | 6 (Germany, France, Canada, Sweden, Australia, USA) | FFQ | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Tessier et al. ( 94 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/women (n 123 mother/daughter pairs) 50–91 years 22–60 years | 2 (Malta, Italy) | Open-ended qualitative questionnaire† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| ToyBox( 95 – 106 ) | Intervention multifactorial study | Adults/parents Number NR Age range NR | 6 (Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Poland, Spain) | Primary caregiver’s FFQ (PCQ)† | No details‡ | Test–retest reliability of the PCQ was assessed after 2-week interval( 112 ) No data for F&V |

| Van Diepen et al.( 107 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults/students (n 185) Age range NR | 2 (Greece, Netherlands) | 2×consecutive 24-HDR | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| WHO-MONICA EC/MONICA Project optional nutrition study( 46 , 108 , 123 ) | Cross-sectional | Adults (n 7226) 45–64 years | 9 (Northern Ireland, UK (Cardiff), Denmark, Finland, Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Spain) | 3 d record and 7 d record One centre used 3×24-HDR | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Adolescents | ||||||

| Gerrits et al. ( 109 ) | Cross-sectional | Adolescents (n 537) 14–19 years | 3 (Netherlands, Hungary, USA) | FFQ | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| HBSC( 31 , 110 ) | Cross-sectional | Adolescents (n 209 320) 11-, 13- and 15-year-olds | 37 (England, Norway, Macedonia, Iceland, Netherlands, Portugal, Wales, Italy, Sweden, Latvia, Switzerland, Denmark, Estonia, Scotland, Slovenia, Ukraine, Belgium, Finland, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, Greenland, Russia, Armenia, Austria, Belgium, Spain, France, Romania, Turkey, Czech Republic, Ireland, Luxembourg, Slovakia) | FFQ† | Validated using 24 h food behaviour checklist and a 7 d food diary( 132 ) Assessed by crude correlations, energy-adjusted correlations, and mean or median differences in F&V consumption Good agreement but overestimation of intakes by FFQ v. 7 d diary | Interval: 7–15 d( 123 ) Provides reproducible estimates of food group intake |

| HELENA( 32 – 36 , 50 , 111 , 112 ) | Cross-sectional | Adolescents (n 3000) 13–17 years | 9 (Greece, Germany, Belgium, France, Hungary, Italy, Sweden, Austria, Spain) 8 countries included for 24-HDR (as above, except Hungary) Only Belgium tested the online FFQ 5 (Austria, Belgium, Greece, Sweden, Germany) pilot-tested the online FFQ | 24-HDR HELENA-DIAT (Dietary Assessment Tool)†Online FFQ | YANA-C validated using food records and 24 h dietary recall interviews( 35 )Assessed by crude correlations and median or mean differences Good agreement between intakes assessed by 24-HDR administered by self-report and interview Validated using four computerised 24-HDR( 35 , 121 ) Overestimation for vegetables | Interval: 1–2 weeksHELENA FFQ has adequate reliability |

| Larsson et al. ( 113 ) | Cross-sectional | Adolescents (n 2041) Age range NR | 2 (Sweden, Norway) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| Szczepanska et al. ( 114 ) | Cross-sectional | Adolescents (n 404) Age range NR | 2 (Poland, Czech Republic) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| TEMPEST( 115 ) | Cross-sectional | Adolescents (n 2764) 12–17 years | 4 (Netherlands, Poland, UK, Portugal) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| I.Family Project( 50 , 73 , 74 ) | Prospective cohort study (successor of IDEFICS study) | Adolescents (n >9000 children of IDEFICs study and their siblings) 12–17 years | 8 (Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | Diet questionnaire as part of the parent questionnaire Online 24-HDR (SACANA) | Instruments are similar to validated instruments used in the IDEFICS project | No details‡ |

| Children | ||||||

| Antova et al. ( 116 ) | Cross-sectional | Children (n 20 271) 7–11 years | 6 (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| ENERGY( 27 ) | Cross-sectional | Children (n 7234) 10–12 years | 7 (Belgium, Greece, Hungary, Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Spain) | Questionnaire with FFQ and 24-HDR† | No details‡ | The reliability and content validity of the child questionnaires were tested separately in all participating countries( 143 ) Reliability tested using a test–retest design was used by comparing data from two completions of the questionnaire conducted 1 week apart( 130 ) No reliability data for F&V |

| EYHS( 30 , 117 ) | Cross-sectional | Children (n≈4000) 9 and 15 years | 4 (Denmark, Portugal, Estonia, Norway) (sourced study involves only Sweden) | 24-HDR, qualitative food record | Children’s ability to recall what they consumed during a 24 h period was compared with observational data collected during the same period( 144 ) Not conducted among European population | No details‡ |

| IDEFICS( 37 , 38 , 118 , 119 ) | Prospective cohort study with an embedded intervention | Children (n 16 224) 2–9 years | 8 (Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | CEHQ-FFQ† SACINA 24-HDR† ( 50 ) | Validity was assessed using biomarkers( 140 ) and 24-HDR( 38 ). No biomarker validation data for F&V Assessed against 24-HDR by crude correlations, de-attenuated correlation coefficients, mean or median differences, and exact level of agreement Association between FFQ and 24-HDR varied by food group and age. Low agreement of FFQ with 24-HDR High relative validity between FFQ and 24-HDR. FFQ can reliably estimate food group intake among Spanish children SACINA is based on the YANA-C instrument validated as part of the HELENA study( 35 , 135 ). SACINA was validated using the doubly labelled water technique( 134 ). No validation data on F&V | Interval: 0–354 d (no fixed time period)( 145 ) CEHQ-FFQ provides reproducible estimates of food group intake |

| I.Family Project( 50 , 73 , 74 ) | Prospective cohort study (successor of IDEFICS study) | Children (n >9000 children of IDEFICS study and their siblings) 2–11 years | 8 (Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | Diet Questionnaire (FFQ) as part of the children’s questionnaire Online 24-HDR (SACANA) | Instruments are similar to validated instruments used as part of the IDEFICS project | No details‡ |

| ISAAC Phase II( 40 , 120 ) | Cross-sectional | Children (n ≈63 000 including international countries) 8–12 years | 15 (Albania, France, Estonia, Germany, Georgia, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, UK) | FFQ† | No details‡ | No details‡ |

| PRO GREENS( 85 ) | Cross-sectional | Children (n 8159) 11 years | 10 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Finland) | A pre-coded 24-HDR†, FFQ† | Validity of 24-HDR and FFQ was tested in 4 countries (Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Portugal) using a 1 d weighed food record and 7 d food records Assessed by crude correlations, mean or median differences, and exact level of agreement FFQ: Moderately good ranking of F&V food groups in 4 countries 24-HDR: Valid estimates for fruit in 3 countries (exception Portugal) Valid estimates for vegetables in 2 countries (exception Iceland and Norway) | Assessed in 6 countries (Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Portugal, Spain) Interval: 7–12 d( 42 ) Good reproducibility for FFQ Test–retest reliability carried out in 5 countries (Norway, Spain, Denmark, Portugal, Belgium) with a 1-week interval( 136 ) No information on F&V intake |

| Pro-Children study( 42 , 86 , 87 ) | Cross-sectional | Children (n 15 404) 11 years | 9 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway Portugal, Spain, Sweden) | A pre-coded 24-HDR†, FFQ† | As per PRO-GREENS( 42 , 136 ) | As per PRO-GREENS( 42 , 136 ) |

| ToyBox( 95 – 106 ) | Intervention multifactorial study | Children (n 5472) 3·5–5·5 years | 6 (Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Poland, Spain) | Children’s FFQ† | Validated using estimated 3 d diet records( 137 ) Assessed by crude correlations, de-attenuated correlation coefficients, mean or median differences, and exact level of agreement Moderate relative validity between FFQ and diet records | Interval: at least 5 weeks( 137 ) FFQ provides reproducible estimates of food group intake |

CNSHS, Cross National Student Health Survey; ECRHS, European Community Respiratory Health Survey; EHBS, European Health and Behaviour Survey; ENERGY, EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; ESCAREL, European Study in Non Carious Cervical Lesions; HAPIEE, Health, Alcohol and Psychosocial factors in Eastern Europe; HTT, Health in Times of Transition; IHBS, International Health and Behaviour Survey; LLH, Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health; MEDIS, MEDiterranean Islands Study; MGSD, Mediterranean Group for the Study of Diabetes; SENECA, Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly; a Concerted Action; MONICA, Multinational MONItoring of trends and determinants in CArdiovascular disease; HBSC, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children; HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; TEMPEST, ‘Temptations to Eat Moderated by Personal and Environmental Self-regulatory Tools’; EYHS, European Youth Heart Study; IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS; ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; NR, not reported; 24-HDR, 24 h recall; PCQ, Primary Caregiver’s Questionnaire; F&V, fruit and vegetables; YANA-C, Young Adolescents’ Nutrition Assessment on Computer; CEHQ, Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire.

Funded by the Wellcome Trust programme grant entitled ‘Determinants of Cardiovascular Diseases in Eastern Europe: A multi-centre cohort study’ (reference number 064947/Z/01/Z) and developed by Martin Bobak, Anne Peasey, Hynek Pikhart (UCL), Ruzena Kubinova, Lubomíra Milla Novosibirsk, Sofia Malyutina, Oksana Bragina (Prague), Andrzej Pajak, Aleksandra Gilis-Januszewska (Krakow).

Original instrument obtained for review.

Validation or reproducibility of the instrument was not reported in the article and no reference to validation or reproducibility studies were provided.

From the sourced articles, fifty-one pan-European studies in total were identified: thirty-five named projects and sixteen smaller projects( 48 , 54 , 56 , 65 , 69 , 72 , 82 , 83 , 88 , 93 , 94 , 107 , 109 , 113 , 114 , 116 ). Most studies assessed dietary intake of F&V among adults( 18 , 41 , 44 , 46 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 54 – 57 , 59 , 60 , 64 – 66 , 68 , 69 , 71 , 72 , 75 – 79 , 81 – 84 , 86 , 88 , 92 – 94 , 107 , 146 , 147 ). Five assessed parents or caregivers( 27 , 50 , 85 – 87 , 102 ). Four studies examined intake among older adults, namely MEDIS (MEDiterranean Islands Study)( 78 ), the Seven Countries Study( 4 , 91 , 92 ), SENECA (Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly; a Concerted Action)( 43 , 90 , 148 , 149 ) and the ‘Food in later life’ study( 68 ). Nine studies assessed intake among children( 27 , 30 , 37 , 50 , 85 , 86 , 101 , 116 , 120 ) in age ranges 2–9 years( 37 , 118 , 119 ), 3–6 years( 95 – 106 ), 2–11 years( 50 ), 7–11 years( 116 ), 11 years( 85 ) and 10–12 years( 27 ), and seven assessed intake among adolescents( 32 , 50 , 109 , 110 , 113 – 115 ).

Validation

Table 2 provides detail on the instruments’ validation. Of the studies which were validated or tested for reproducibility and fulfilled inclusion criterion 1 (Table 1), validity and reliability of the FFQ was assessed using biomarkers( 63 , 126 ), FFQ( 52 ), food records( 42 , 53 , 80 , 128 – 132 , 137 , 138 ) or 24 h recalls (24-HDR)( 36 , 38 , 80 , 129 , 135 ) as the reference method. In fifteen studies, validity was assessed by crude correlations( 35 , 36 , 38 , 42 , 53 , 63 , 80 , 126 , 128 , 130 , 132 , 137 , 138 ), energy-adjusted correlations( 52 , 53 , 126 , 129 ), de-attenuated correlation coefficients( 36 , 38 , 129 , 137 ), mean or median differences in F&V consumption( 35 , 36 , 38 , 42 , 52 , 53 , 80 , 126 , 128 – 130 , 132 , 137 , 138 ), exact level of agreement of F&V consumption( 38 , 42 , 52 , 53 , 80 , 126 , 130 , 132 , 137 , 138 ), Bland–Altman plots( 36 , 52 , 53 , 129 ) or weighted kappa( 38 , 137 ) between the FFQ and reference instrument. In nine studies, reliability of F&V consumption was assessed by correlations( 36 , 42 , 53 , 80 , 131 , 132 , 137 , 145 ), mean/median differences( 36 , 80 , 137 , 138 , 145 ), weighted kappa( 132 , 138 , 145 ) or intraclass correlation coefficients( 137 ) between subsequent assessments of the FFQ. Where available, data were extracted and are provided in detail in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2.

Dietary intake assessment methods

Types of methods

Several methods were used to assess dietary intake of F&V in the identified studies. The vast majority of the pan-European studies used FFQ (n 42)( 27 , 29 , 30 , 36 , 41 , 48 , 50 , 52 , 54 – 56 , 58 – 60 , 64 – 66 , 69 , 71 , 72 , 75 , 76 , 78 , 79 , 82 , 84 – 86 , 88 , 93 , 104 , 109 , 110 , 113 – 116 , 120 , 139 , 146 , 150 ). Since a common FFQ instrument was not used across all countries in the EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) study, only the EPIC-SOFT instrument is discussed in the current review.

According to the two selection criteria (i.e. whether tested for validity or reproducibility and used in more than two countries representing a range of European regions; Table 1), six instruments were appropriate to assess intake of F&V in future pan-European studies among adults: EPIC-SOFT, the Food4Me FFQ, the ToyBox Primary Caregiver’s Questionnaire, the ENERGY (EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth) parent questionnaire, and the dietary history methods used by the SENECA study and Seven Countries Study. Three instruments used to assess intake among adolescents, HELENA-DIAT (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence–Dietary Assessment Tool), HELENA online FFQ and the HBSC (Health Behaviour in School-aged Children) FFQ, fulfilled the criteria. The ENERGY children’s questionnaire and the instruments used by the IDEFICS, Pro-Children and ToyBox studies appeared appropriate to measure F&V among children. Although not validated separately, the I.Family instruments were based closely on those of the IDEFICS study and also met the criteria. The 24-HDR preceded by the 1 d qualitative food record used in the EYHS (European Youth Heart Study) was a validated method but not tested in the study population( 144 ). While Table 1 indicates the selected methods, in the interest of comprehensiveness, details on all the identified methods are provided.

Instruments which met the two selection criteria for which validation data on F&V intake were available are summarized in Table 3. Of those for use among adults, F&V intakes assessed by EPIC-SOFT were described by authors as having weak to moderate correlation with biomarkers( 63 ). The Food4Me FFQ was reported to demonstrate moderate agreement with a 4 d weighed food record( 53 ) and good agreement with the EPIC-Norfolk FFQ( 52 ). While the ToyBox Primary Caregiver’s Questionnaire was tested for reliability there were no data available for F&V. Similarly, the ENERGY parent questionnaire was tested for reliability but data were unpublished. The Seven Countries Study dietary history instrument was not validated but reproducible( 131 ). HELENA-DIAT, administered by self-report, was reported to have good agreement with intakes when administered by interview( 35 ). The HELENA-FFQ was found to have adequate reliability( 36 ). The HBSC FFQ was found to be reproducible and reported to have good agreement with a 7 d food diary( 132 ).

Table 3.

Summary of the selected instruments which were validated (n 8) for assessment of fruit and vegetables

| Study/instrument | Design | Age group | Countries | Mode | Portion estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | |||||

| EPIC( 18 , 28 , 29 , 61 – 63 ) | Cohort | 30–70 years | 10 (Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Germany, Sweden (Malmo)/Sweden(Umea), Denmark, France, Greece, Norway, England) | Face-to-face interviewComputerised | X |

| EPIC-SOFT 24-HDR | |||||

| Food4Me( 51 – 53 ) | Randomised controlled trial | 17–79 years | 7 (Ireland, Netherlands, Spain, Greece, UK, Poland, Germany) | Self-admin. | X |

| Web-based FFQ | |||||

| Adolescents | |||||

| HBSC( 31 , 110 ) | Cross-sectional | 11-, 13- and 15-year-olds | 37 (England, Norway, Macedonia, Iceland, Netherlands, Portugal, Wales, Italy, Sweden, Latvia, Switzerland, Denmark, Estonia, Scotland, Slovenia, Ukraine, Belgium, Finland, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, Greenland, Russia, Armenia, Austria, Belgium, Spain, France, Romania, Turkey, Czech Republic, Ireland, Luxembourg, Slovakia) | Self-admin. | |

| FFQ | |||||

| HELENA( 32 – 36 , 50 , 111 , 112 ) | Cross-sectional | 13–17 years | 8 (Greece, Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Sweden, Austria, Spain) | Self-admin.Computerised | X |

| 24-HDR | |||||

| HELENA-DIAT | |||||

| HELENA( 32 – 36 , 50 , 111 , 112 ) | 13–17 years | 5 (Austria, Belgium, Greece, Sweden, Germany) | Self-admin. | X | |

| Online FFQ | |||||

| Children | |||||

| IDEFICS( 37 , 118 , 119 ) | Prospective cohort study with an embedded intervention | 2–9 years | 8 (Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany Hungary, Italy, Spain, Sweden) | Self-admin. (parents) | |

| CEHQ-FFQ* | |||||

| Pro-Children study( 42 , 86 , 87 ) | Cross-sectional | 11 years | 9 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway Portugal, Spain, Sweden) | Self-admin. | X |

| A pre-coded 24-HDR*, FFQ* | |||||

| ToyBox( 95 – 106 ) | Intervention multifactorial study | 3·5–5·5 years | 6 (Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Poland, Spain) | Self-admin. | X |

| Children’s FFQ* | |||||

EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; 24-HDR, 24 h recall; HBSC, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children; HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infants; CEHQ, Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire; self-admin., self-administered.

Original instrument obtained for review.

The IDEFICS FFQ was compared with two 24-HDR but had low agreement with 24-HDR according to the authors, and agreement varied by food group and age of child in a population across eight survey sites( 38 ). However, the instrument had good agreement with 24-HDR in a sample of Spanish children( 135 ) and has been demonstrated to be reproducible( 145 ). The Pro-Children instrument, when compared with 7 d( 130 ) and 1 d( 42 ) diet records, was reported to have moderate to good validity for ranking individuals according to usual intake and was reproducible( 42 ). The ToyBox study instrument was shown to be reproducible and was reported to have moderate relative validity when compared with 3 d diet records( 137 ).

FFQ

Range of items and definitions

Characteristics of the identified FFQ are summarised in Table 4. FFQ were used to assess dietary intake, identify determinants of dietary intake, or test diet–disease associations and identify disease risk factors. The number of food items listed on these FFQ ranged between sixty-six and 322, with the number of items relating to fruit and vegetables ranging from one item( 27 , 60 ) to ninety-five items( 82 ). Several FFQ used non-itemised terms such as ‘fruit’, ‘vegetables’, ‘fresh fruit’, ‘raw vegetables’ and ‘cooked vegetables’( 37 , 42 , 48 , 56 , 58 , 64 , 66 , 67 , 69 , 75 , 84 , 100 , 109 , 110 , 114 – 116 , 120 ), while others listed individual fruits and vegetables( 30 , 39 , 41 , 52 , 53 , 82 , 150 ). FFQ could be classed as having low (<5 items relating to fruit or vegetables) or high (>5 items relating to fruit or vegetables) comprehensiveness based on the cut-off used by Cook et al. ( 151 ). Thirteen FFQ were classed as having low comprehensiveness for F&V, including the ENERGY and HBSC questionnaires( 27 , 31 , 48 , 56 , 57 , 64 , 66 , 71 , 75 , 114 – 116 , 120 ).

Table 4.

Summary of FFQ: instrument purpose and characteristics

| Study | Type/no. of items | Purpose | Population | F&V items & classification | Reference period | Mode | Categories | Portion estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | ||||||||

| Baldini et al. ( 54 )* | Semi-quantitative Sixty-one-item FFQ | Assess dietary habits Assess influence of lifestyle on energy balance and BMI | Adults/students Age range NR | Exact classification unknown† Used Willett FFQ( 127 ) | Previous month | Self-admin. | Detailed record of food consumption, starting from breakfast and ending at bedtime 9 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘6 or more times per day’ | Yes Assessed separately Pictures of standard meal/food sizes Used natural units if possible A full description of usual serving size was provided for each item |

| Behanova et al. ( 56 )* | Semi-quantitative General questionnaire | Determine prevalence of health-risk behaviours | Adults 19–64 years | Non-itemised Two items: ‘Portions of vegetables’ ‘Portions of fruits’ (including dried fruit, fruit juice) | NR | Self-admin. | Open-ended Subject to report a number of portions | Yes Assessed in-line Examples given for 1 portion, e.g. handful of dried fruit, heaped tablespoon of carrots |

| CNSHS( 57 , 58 ) | Non-quantitative General questionnaire | Test association between food patterns and living arrangements( 57 ) Test association between diet and stress/depressive symptoms( 58 ) | Adults/students Age range NR | Four items: ‘Fresh fruits’ ‘Raw vegetables’ ‘Cooked vegetables’ ‘Salads’ | NR | Self-admin. | 5 categories, ranging from ‘several times a day’ to ‘1–4 times a month’ and ‘never’ | No |

| ENERGY( 27 )* | Semi-quantitative General questionnaire | Determine prevalence of EBRB Identify personal, family and school environmental correlates of EBRB | Adults/caregivers Age range NR | One item: Fruit juices. ‘When we say fruit juices we mean the packed fruit juice and freshly blended juice at home (100 % fruit juice)’ Examples provided | Previous week Usual consumption on a day on which fruit juices are drunk | Self-admin. | 7 categories per week 6 categories per day | Yes Assessed in-line Subject can select number of glasses/small cartons (250 ml) and regular cartons (330 ml) drank on a day of consumption |

| EHBS( 60 ) | Refer to IHBS | Test association between health locus of control and health behaviour | Refer to IHBS | One item: ‘Fruit consumption’ | Refer to IHBS | Refer to IHBS | Refer to IHBS | Refer to IHBS |

| ESCAREL( 64 )* | Non-quantitative Five-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Assess the prevalence of tooth wear on buccal/facial and lingual/palatal tooth surfaces Identify related risk factors (i.e. fresh fruit and juice intake) | Adults18–35 years | Two items: ‘Fresh fruit, e.g. lemon, orange, apple, pear, grapes, mango, etc.’ ‘Fruit and vegetable juice, e.g. orange, apple, grape, pineapple, carrot, multivitamin, etc.’ | NR | Self-admin. | 4 categories: ‘often’, ‘rarely’, ‘never’ and ’don’t know’ For items ranked as ‘often’ a choice of 5 categories, ranging from ‘more than 3 times per week’ to ‘less than once per week’ | No |

| Esteve et al. ( 65 ) | Semi-quantitative Dietary questionnaire | Test association between diet and cancers of the larynx and hypopharynx | Adults Age range NR | Exact classification unknown† Seasonality of F&V assessed | 12 months | Face-to-face interview | Structured by meals, i.e. breakfast, lunch, dinner, as well as early morning, mid-morning, mid-afternoon and late evening snacks | Yes Assessed separately Usual portion size estimated during interview. Method NR |

| Finbalt Health Monitor( 66 )* | Non-quantitative Seventeen-item FFQ within general questionnaire | Assess gender differences in F&V consumption | Adults 20–64 years | Four items: ‘Fresh vegetables’ ‘Other vegetables’ ‘Fresh fruit/berries’ ‘Other fruit/berries’ Potatoes assessed separately | Previous week | Self-admin. | 4 categories: ‘never’, ‘1–2 days’, ‘3–5 days’ and ‘6–7 days’ | No |

| Food4Me( 51 – 53 )‡ | Semi-quantitative Web-based 157-item FFQ | Determine impact of personalised dietary advice on eating patterns and health outcomes | Adults 18–79 years | Previous month | Self-admin. | 9 categories, ranging from ‘never or less than once a month’ to ‘5–6 times per day’ and ‘>6 times per day’ | Yes 3 photographs representing small, medium and large portions Participants could select one of the following options: very small, small, small/medium, medium, medium/large, large or very large, which were linked electronically to portion sizes (in grams) | |

| Galanti et al. ( 69 ) | Semi-quantitative Sixty-item FFQ (Norway) Fifty-six-item FFQ (Sweden) | Test association between diet and papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma | Adults 18–60+ years | Exact classification unknown† Six items: ‘All vegetables’ ‘Vegetables, excluding cruciferous’ ‘Cruciferous vegetables’ ‘All fruit (piece)’ ‘Apple’ ‘Citrus fruit’ | NR | Self-admin. | For foods which traditionally are consumed more often and for all beverages, average number of servings was requested, per day, week or month Less frequently consumed foods: 6 pre-coded frequencies, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘once a day or more often’ | Yes Assessed in-line Asked to specify number of servings |

| HAPIEE( 70 )* | Semi-quantitative Czech=136-item FFQ Russian=147-item FFQ Polish=148-item FFQ | Test association between socio-economic indicators and diet( 147 ) | Adults 45–69 years | As per generic FFQ (note: number of items differs slightly for each local adaption) Fifty-three items: Twenty-one items under ‘Fresh fruit’ ‘Tinned or bottled fruit’ Thirty-one items under ‘Vegetables’ (Pulses included) 1 fruit juice Potatoes assessed separately | Previous 3 months | Interview (Russia & Poland) Self-admin. (Czech Republic) | 9 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘six or more times per day’ Open-ended section where subjects could add any further foods not listed | Yes Assessed in-line A country-specific portion size for each food was specified Participants were asked how often, on average, they had consumed a ‘medium serving’ of the items – defined as about 100 g or 50 g depending on the food in question |

| HTT( 71 )* | Non-quantitative Ten-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Identify factors associated with low consumption of F&V | Adults Age range NR | Two items: ‘Fresh fruit’ ‘Fresh vegetables (except for potatoes)’ | Previous week | Face-to-face interview | 4 categories, ranging from ‘daily/almost daily’ to ‘less than once a week’ | No |

| Hupkens et al. ( 72 ) | Semi-quantitative 150-item FFQ used for NCS | Test association between social class factors and fat and fibre consumption | Adults 55–69 years | Twenty-eight items: Thirteen boiled veg items Five raw veg items Seven fruit items Three juice items Potatoes assessed separately Vegetable seasonality assessed | 12 months | Self-admin. | 6 categories (veg), ranging from ‘never’ to ‘3 or 7 times per week’ 6 categories (fruit), ranging from ‘never’ to ‘6 or 7 times per week’ Open-ended section for foods not on the FFQ | NR |

| I.Family Project( 50 ) | Non-quantitative Sixty-item FFQ | Assess determinants of eating behaviour | Adults/parents No age range determined | Nine items: Four veg items (including legumes and potatoes) Two fruit items (fresh with or without sugar) One fruit juice item Nuts and dried fruits separately (two items) under ‘snacks’ | Typical week over the previous month | Self-admin. | 7 categories, ranging from ‘never/less than once a week’ to ‘4 or more times per day’ | No |

| IHBS( 75 )* | Non-quantitative Two-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Test association between life satisfaction and health behaviours | Adults 17–30 years | One item: ‘Fruit’ | NR | Self-admin. | 5 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘at least once every day’ | No |

| IMMIDIET( 39 , 76 ) | Semi-quantitative 322-item EPIC-Italy FFQ (as above) EPIC-UK FFQ (as above) | Identify determinants (diet, genetic) of risk of myocardial infarction( 39 ) Determine role of dietary patterns in plasma and red blood cell fatty acids variation( 76 ) | Adults 26–65 years | Sixty-three items: Twenty-one cooked veg items Ten raw veg items Thirty-two fruit items (including fresh, tinned, dried) Potatoes and legumes assessed separately | 12 months | Face-to-face interview Self-admin. in validity study( 40 ) | 9 categories, ranging from ‘never/rarely’, ‘1–3 days/month’ to ‘1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 days per week’ | Yes Assessed separately Recorded as absolute weights or as household measurements Photo book to estimate small, average and large portions for spreads, bread spreads, and milk in coffee and tea |

| LLH( 71 )* | Non-quantitative Nine-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Identify factors associated with low consumption of F&V | Adults Age range NR | Two items: ‘Fruit’ ‘Vegetables (except for potatoes’ | Previous week | Face-to-face interview | 4 categories, ranging from ‘extremely seldom’ to ‘daily’ | No |

| NORBAGREEN( 41 , 80 )* | Non-quantitative Fifty-six-item FFQ | Assess the frequency of consumption of vegetables, potatoes, fruit, bread and fish | Adults and adolescents 15–74 years | Thirty-nine items: Questions on global ‘Vegetables and roots’ and ‘Fruits and berries’ consumption (including pulses) Nineteen veg items Fourteen fruit items Four potato items Potatoes assessed separately | 12 months | Using CATI in the Nordic countries and PAPI in the Baltic countries | Times per month, ranged from ‘<1 or not at all’ to ‘3’ Times per week, ranged from ‘1’ to ‘6’ Times per day, ranged from ‘1’ to ‘4 or more’ | No |

| MGSD( 79 )* | Semi-quantitative Dietary history questionnaire with seventy-eight items | Compare the nutritional habits among six Mediterranean countries and with official recommendations | Adults 35–60 years | Eleven items: Three ‘Cooked veg’ non-itemised questions, each with different veg group One ‘Raw veg’ item Two itemised veg (onions, garlic) Two ‘Cooked legumes’ items One ‘Fruit’ item One ‘Juice’ item One ‘Dried fruit’ item Potatoes assessed separately | NR | Face-to-face interview | Enter number per day or per week for pre-coded itemsOpen-ended section structured by seven meals, whereby subject enters the time, description, quantity, and whether food eaten at home or in a restaurant | Yes Assessed in-line 15 g or about 1 tablespoon 100 g or 1 cup (raw veg) 200 g or 1 cup (cooked veg A) 100 g or 1 cup (cooked veg B) 200 g or 1 cup (cooked veg C) 150 g (fruit) 200 g or 1 glass (juice) Assessed separately Household measures |

| O’Neill et al. ( 82 )* | Semi-quantitative 107-item FFQ | Determine and compare carotenoid intakes across European countries | Adults 25±45 years | Ninety-five items: Twenty-eight green veg items (including pulses) Seventeen red-orange vegetable items Seventeen white-yellowish coloured veg items (including potatoes) Twenty-seven individual fruit items Six F&V relevant items under ‘Other products’ (mainly tomato products and soups and orange juice) | Past 3–4 months | Self-admin. | If high frequency, range from 1 to 7 per week If low consumption frequency, 4 categories ranging from ‘never’ to ‘once per fortnight’ | Yes Assessed separately Asked to quantify intake for each food item by tablespoons for vegetables and by large, small or medium in terms for fruit |

| PRIME( 84 ) | Non-quantitative No. of items NR | Assess relationship between F&V intake and CVD | Adults/men 50–59 years | Exact classification unknown† ‘Citrus fruit’, ‘Other fruit’, ‘Raw vegetables’ ‘Baked vegetables’ | NR | Self-admin. | 7 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘more than once per day’ (subject reports number per day) | Assessed in-line Frequency of consumption of a ‘standard portion’ |

| Finnish and Russian Karelia study( 146 )* (2002 survey) | Non-quantitative Forty-three-item FFQ (FINRISK) and two-item FFQ (Pitkaranta town) within a general questionnaire | Determine impact of socio-economic differences on consumption of F&V and berries | Adults 25–64 years | Finnish FFQ: Nine items: Six ‘Vegetables’ items (including pulses, potatoes) Three ‘Fruits/berries’ items Russian FFQ: Six items: Four ‘Vegetables’ items (including pulses, potatoes) Two ‘Fruits and berries’ items | 12 months | Self-admin. | 6 categories, ranging from ‘less than once a month’ to ‘once a day or more often’ | No |

| Rylander et al. ( 88 ) | Non-quantitative Ninety-item FFQ | Test association of dietary habits and smoking status | Adults 35–65 years | Exact classification unknown† | 12 months | Self-admin. | 10 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘six or more times per day’ | No |

| ToyBox Caregiver’s Questionnaire( 95 – 106 )* | Semi-quantitative. Five-item FFQ (drinking behaviour) and fourteen-item FFQ (snacking behaviour) within a general questionnaire | Measure the effectiveness of an intervention to prevent obesity | Adults/caregivers Age range NR | Three items: Drinking behaviour: Examples provided. ‘Fruit juice, home-made, freshly squeezed’ Snacking behaviour: ‘Fresh fruits’ ‘Vegetables’ | 12 months | Self-admin. | 7 categories, ranging from ‘1–3 days per month’ to ‘every day’ | Yes Assessed in-line Portion size specified for fruit juice as beaker=225 ml, 1 small plastic bottle =500 ml, 1 carton=1 litre Aided by a photo book |

| MEDIS( 78 ) | Non-quantitative No. of items NR | Test association between energy-generating nutrients and obesity | Adults/elderly 65–80+ years | Exact classification unknown† ‘Fruits’, ‘Vegetables’, ‘Greens and salads’ Potatoes and legumes assessed separately | NR | NR | Frequency assessed on a daily, weekly or monthly basis | No |

| Terry et al. ( 93 ) | Semi-quantitative Dietary questionnaire No. of items NR | Test association between diet and brain tumour risk | Adults 20–82 years | Exact classification unknown† | NR | Face-to face interview | Exact classification unknown† | Yes Assessed separately Abstract food models or photographs used to aid portion size estimation |

| Pro-Children( 86 )* | Non-quantitative Six-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Assess F&V consumption Identify determinants of F&V consumption patterns | Adults/parents Age range NR | Six items: ‘Fresh fruit’ ‘Salad or grated vegetables’ ‘Raw vegetables’ ‘Cooked vegetables’ ‘100 % fruit juice’ Potatoes assessed separately | NR | Self-admin. | 8 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘every day, more than twice a day’ | No |

| Kolarzyk et al. ( 48 )* | Non-quantitative Thirty-nine-item FFQ | Assess diet and the prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity | Adults/students Age range NR | Four items: ‘Fruit’ ‘Vegetables’ ‘Fruit juice’ ‘Vegetable juice’ Pulses and potatoes assessed separately | Previous month | Self-admin. | 7 categories, ranging from ‘not eaten at all’ to ‘eaten every day’ | No |

| Adolescents | ||||||||

| Gerrits et al. ( 109 ) | Non-quantitative Two items within a general questionnaire | Test association of psychological variables with consumption of fatty foods and F&V | Adolescents 14–19 years | Exact classification unknown† ‘Servings of fruit’ ‘Servings of vegetables’ | Usual consumption per day | Self-admin. | 4 categories, ranging from ‘less than one serving a day’ to ‘3 or more servings a day’ | Yes Assessed in-line Asked to specify number of servings |

| HELENA( 47 , 121 ) | Semi-quantitative 137-item FFQ | Assess effectiveness of an intervention to enhance the physical activity and diet of adolescents | Adolescents 13–17 years | Exact classification unknown† Groups: ‘Vegetables’ (pulses included), ‘Fruit’ One F&V juices item Potatoes assessed separately | NR | Self-admin. | 10 categories Then select frequency of: ‘Units per day’, ‘Units per week’ or ‘Units during the last 30 d’ | Yes Assessed in-line Frequency and portion selected together for fruit juices; i.e. 1 glass/2 glass, 10 glass Photos, 4 portion sizes (amorphous foods) |

| TEMPEST( 115 )* | Semi-quantitative Five-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Test association of ‘subjective peer norms’ with eating intentions and diet | Adolescents 12–17 years | Two items: ‘Fruit’ ‘Cooked or raw vegetables’ | Per average day | Self-admin. | 5 categories, ranging from ‘less than 1’ to ‘more than 4’ | Yes Assessed in-line Participants asked to report ‘servings’ of fruit or ‘serving spoons’ of cooked or raw vegetables |

| HBSC 2009/10( 31 , 110 )* | Non-quantitative Four-item FFQ within general questionnaire | Determine health and health behaviours and the factors that influence them( 31 ) Investigate influence of chronological period of data collection on dietary intake( 110 ) | Adolescents 11-, 13- and 15-year-olds | Two items: ‘Fruits’ ‘Vegetables’ | Habitual intake over a week | Self-admin. | 7 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘every day, more than once’ | No |

| I.Family Project( 50 ) | Non-quantitative Sixty-item FFQ | Assess determinants of eating behaviour | Adolescents 12–17 years | Nine items: Four veg items (including legumes, and potatoes) Two fruit items (fresh with or without sugar) One fruit juice item Nuts and dried fruits separately (two items) under ‘snacks’ | Typical week over the previous month | Self admin. | 7 categories, ranging from ‘never/less than once a week’ to ‘4 or more times per day’ | No |

| Szczepanska et al. ( 114 )* | Non-quantitative Twelve-item FFQ | Assess and compare dietary habits | Adolescents Age range NR | Two items: ‘Fruit’ ‘Vegetables’ | Not stated | Self-admin. | 5 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘3–4 times per week’ | No |

| Larsson et al. ( 113 )* | Non-quantitative Thirty-three-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Determine prevalence of vegetarianism Compare food habits among vegetarians and omnivores | Adolescents Age range NR | Fifteen items: ‘Vegetables (all except potatoes)’ Eight vegetable items ‘Fruits and berries (including frozen)’ Five fruit items Potatoes assessed separately | 12 months | Self-admin. | 6 categories, ranging from ‘never/rarely’ to ‘several times a day’ | No |

| Children | ||||||||

| Antova et al. ( 116 )* | Non-quantitative Five-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Test association between diet and respiratory health | Children 7–11 years | Two items: ‘Fresh fruit’ (in Winter, in Summer) ‘Fresh vegetables’ (in Winter, in Summer) F&V seasonality assessed | NR | Self-admin. | 4 categories, ranging from ‘>4 times per week’ to ‘less than once per month’ | No |

| ENERGY( 27 )* | Semi-quantitative General questionnaire | Determine prevalence of EBRB Identify personal, family and school environmental correlates of EBRB | Children 10–12 years | One item: Fruit juices. ‘When we say fruit juices we mean the packed fruit juice and freshly blended juice at home (100 % fruit juice)’ Examples provided | Previous week Usual consumption on a day on which fruit juices are drunk | Self-admin. | 7 categories per week 6 categories per day | Yes Assessed in-line Subject can select number of glasses/small cartons (250 ml) and regular cartons (330 ml) drank on a day of consumption |

| IDEFICS( 37 , 118 , 122 )* | Non-quantitative Forty-three-item FFQ | Determine the aetiology of overweight, obesity and related disorders Test association between diet and cardiovascular risk factors( 139 ) Test association between diet and body mass( 118 ) | Children 2–9 years (parents or guardians as proxies) | Eight items: Four vegetable items (including legumes, and potatoes) Two fruit items (fresh with or without sugar) One fruit juice item Nuts and dried fruits separately under ‘snacks’ | Typical week over the previous month | Self-admin. | 8 categories, ranging from ‘never/less than once a week’ to ‘4 or more times per day’ ‘I have no idea’ was also an option | No |

| I.Family Project( 50 ) | Non-quantitative Fifty-nine-item FFQ | Assess determinants of eating behaviour | Children 2–11 years (parents or guardians as proxies) | Eight items: Four vegetable items (including legumes, and potatoes) Two fruit items (fresh with or without sugar) One fruit juice item Nuts and dried fruits separately (two items) under ‘snacks’ | Typical week over the previous month | Self admin. | 7 categories, ranging from ‘never/less than once a week’ to ‘4 or more times per day’ | No |

| ISAAC( 120 )* | Non-quantitative Eight-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Test association between dietary factors, asthma and allergy | Children 8–12 years (parents or guardians) | Four items: ‘Fresh fruit’ ‘Raw green vegetables’ ‘Cooked green vegetables’ ‘Fruit juice’ | NR | Self-admin. | 5 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘once per day or more often’ | No |

| Pro-Children/PRO GREENS( 42 , 85 – 87 , 136 )* | Non-quantitative Six-item FFQ within a general questionnaire | Assess F&V consumption and determinants of F&V consumption patterns | Children 11 years | Five items: ‘Fresh fruit’ ‘Salad or grated vegetables’ ‘Raw vegetables’ ‘Cooked vegetables’ ‘100 % fruit juice’ Potatoes assessed separately | NR | Self-admin. | 8 categories, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘every day, more than twice a day’ | No |

| ToyBox Children’s FFQ( 95 – 106 )* | Semi-quantitative Forty-four-item FFQ | Measure the effectiveness of an intervention to prevent obesity | Children 3·5–5·5 years (parents or guardians as proxies) | Six items: ‘Fruit juice, home-made, freshly squeezed’ Global groups used: ‘Dried fruit’, ‘Canned fruit’, ‘Fresh fruit’, ‘Raw veg’ and ‘Cooked veg’ Potatoes and legumes assessed separately | 12 months | Self-admin. | 6 categories, ranging from ‘1–3 days per month’ to ‘every day’ | Yes Assessed separately Subjects asked to select from a range of portion for each food, e.g. from ‘100 ml or less’ to ‘1000 ml or more’. Examples of corresponding portions (g or ml) provided for each food item Photo book in appendix of the FFQ |

CNSHS, Cross National Student Health Survey; ENERGY, EuropeaN Energy balance Research to prevent excessive weight Gain among Youth; EHBS, European Health and Behaviour Survey; ESCAREL, European Study in Non Carious Cervical Lesions; HAPIEE, Health, Alcohol and Psychosocial factors in Eastern Europe; HTT, Health in Times of Transition; IHBS, International Health and Behaviour Survey; LLH, Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health; MGSD, Mediterranean Group for the Study of Diabetes; PRIME, Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction; MEDIS, MEDiterranean Islands Study; HELENA, Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence; TEMPEST, ‘Temptations to Eat Moderated by Personal and Environmental Self-regulatory Tools’; HBSC, Health Behaviour in School-aged Children; IDEFICS, Identification and prevention of Dietary- and lifestyle-induced health EFfects In Children and infantS; ISAAC, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; NR, not reported; EBRB, energy balance-related behaviours; F&V, fruit and vegetables; veg, vegetables; self-admin., self-administered; CATI, computer-assisted telephone interview; PAPI, paper-assisted personal interview.

Original instrument obtained for review.

Original instrument not obtained.

Information on Food4Me instrument was obtained from study authors.

Some FFQ further subdivided F&V into ‘raw/fresh’, ‘cooked’ or ‘tinned’, each with separate items listed underneath( 150 ). The NORBAGREEN FFQ( 41 ) and the FFQ used by Larsson et al.( 113 ) assessed the consumption of individual fruits and vegetables, but also included a cross-check question on the total consumption of vegetables and fruits. The NORBAGREEN FFQ assessed consumption within different contexts and using different cooking styles; for example, asking participants to report the frequency of consumption of ‘cooked, canned or steamed vegetables’ and of ‘dried fruit or berries’.

Where individual F&V items were listed, FFQ also varied in terms of whether pulses( 38 , 82 ) or potatoes( 58 , 109 ) were included under ‘vegetables’. Some FFQ listed potatoes as ‘cooked vegetables’( 38 , 67 ), ‘white-yellowish vegetables’( 82 ) or specified ‘vegetables (potatoes excluded)’( 71 , 113 ). Many FFQ listed separate potato items or ‘potatoes’ and ‘legumes/pulses’ as separate group headings with their own items listed below( 30 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 66 , 100 , 113 , 150 ). With some exceptions( 52 , 53 , 86 , 104 ), if an FFQ listed fruit or vegetable juice it did not always specify 100 % fruit or vegetable juice( 27 , 86 , 100 ). Therefore, participants could interpret this as including fruit squash and dilutions.

Mode and structure