Abstract

Objective

The current study aimed to examine the impact of sociodemographic and health-service factors on breast-feeding in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries with high diarrhoea mortality.

Design

The study used the most recent and pooled Demographic and Health Survey data sets collected in nine SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality. Multivariate logistic regression models that adjusted for cluster and sampling weights were used to investigate the association between sociodemographic and health-service factors and breast-feeding in SSA countries.

Setting

Sub-Saharan Africa with high diarrhoea mortality.

Subjects

Children (n 50 975) under 24 months old (Burkina Faso (2010, N 5710); Demographic Republic of Congo (2013, N 6797); Ethiopia (2013, N 4193); Kenya (2014, N 7024); Mali (2013, N 3802); Niger (2013, N 4930); Nigeria (2013, N 11 712); Tanzania (2015, N 3894); and Uganda (2010, N 2913)).

Results

Overall prevalence of exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) and early initiation of breast-feeding (EIBF) was 35 and 44 %, respectively. Uganda, Ethiopia and Tanzania had higher EBF prevalence compared with Nigeria and Niger. Prevalence of EIBF was highest in Mali and lowest in Kenya. Higher educational attainment and frequent health-service visits of mothers (i.e. antenatal care, postnatal care and delivery at a health facility) were associated with EBF and EIBF.

Conclusions

Breast-feeding practices in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality varied across geographical regions. To improve breast-feeding behaviours among mothers in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality, breast-feeding initiatives and policies should be context-specific, measurable and culturally appropriate, and should focus on all women, particularly mothers from low socio-economic groups with limited health-service access.

Keywords: Breast-feeding, Diarrhoea, Sub-Saharan Africa, Infants, Breast milk

Optimal breast-feeding is a cost-effective and important measure to improve mother and infant health. Breast-fed infants have a lower risk for diarrhoeal diseases( 1 , 2 ), lower under-5 mortality rate( 3 ) and higher cognitive functioning( 2 ). Breast-feeding mothers have improved family planning and a reduced risk of breast and ovarian cancers( 4 , 5 ). Globally, efforts have been made to improve child health, including infant feeding. These initiatives include the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (referred to hereafter as ‘the Code’); the Innocenti Declaration; the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI); the Millennium Development Goals; and, more recently, the Global Nutrition Targets 2025 and Sustainable Development Goals.

Despite these sustained efforts, improvements in breast-feeding practices have been slow and disproportionate worldwide( 4 ). For example, exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) rates varied in Africa (35 %) and Asia (41 %) in 2010( 6 ). Diarrhoea is a major public health issue in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, accounting for approximately 46 % of the global diarrhoea burden( 7 ). The impact of optimal breast-feeding practices on diarrhoea-related morbidity and mortality has been documented in many developing countries( 8 – 11 ). A recent population-based study from SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality indicated that optimal breast-feeding practices were protective of diarrhoea in African children( 12 ).

In many SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality( 13 ), there is limited up-to-date evidence on the risk factors for suboptimal breast-feeding practices at the national level to scale up and guide efforts at improving breast-feeding practices. Studies from regional areas and three national reports from SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality have elucidated factors associated with suboptimal breast-feeding practices. These factors included: poverty, low maternal education, fewer health-service contacts( 14 , 15 ), young maternal age, home delivery, cultural beliefs held for breast-feeding( 15 – 17 ) and limited family support( 18 ). The nationwide studies on breast-feeding from Nigeria( 15 ) and Tanzania( 16 ) used older population-based data sets and only focused on EBF. Findings from these studies may be limited in providing up-to-date evidence on broader breast-feeding practices such as early initiation of breast-feeding, predominant breast-feeding or bottle-feeding for targeted interventions.

A study that is specific to the impact of sociodemographic and health service factors on breast-feeding across geographies in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality would be helpful for informing well-guided interventions. It is imperative that these approaches are evidence-based and directly connected to countries requiring those initiatives. Using the most recent nationally representative, consistent and reliable data, in the present study, we provide up-to-date information on risk factors for breast-feeding practices in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality. We take advantage of the standardised population-based breast-feeding data to better examine determinants of breast-feeding practices across SSA countries. Our study aimed to examine the impact of sociodemographic and health-service factors on breast-feeding in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality.

Methods

Data sources

The present study used the most recent and pooled Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data for 50 975 children under 24 months of age (Burkina Faso (2010, N 5710); Demographic Republic of Congo (2013, N 6797); Ethiopia (2013, N 4193); Kenya (2014, N 7024); Mali (2013, N 3802); Niger (2013, N 4930); Nigeria (2013, N 11 712); Tanzania (2015, N 3894); and Uganda (2010, N 2913)). These SSA countries were selected for the study because of previously published reports which showed that diarrhoea mortality was highest among those countries in the African continent( 13 , 19 ). The DHS project collects demographic, maternal and child health (including breast-feeding) information from a nationally representative sample of households. The data were collected by country-specific population commissions and departments of health in partnership with the Inner City Fund (ICF) International and Measure DHS, using standardised household questionnaires. A two-stage sampling strategy was used, where a country was divided into enumeration areas (clusters) based on the recent census frame for that country, and then households were randomly selected from each cluster. Household sociodemographic characteristics, maternal and child health data were obtained from eligible women aged 15–49 years in each household surveyed. The study used a total weighted sample of 50 975 maternal responses for children under 24 months of age (alive and living with the respondent), with response rate in the surveys ranging from 96 to 99 %. Many mothers in the selected SSA countries (except for Ethiopia and Niger) were in employment. Home delivery was prevalent in Ethiopia, Niger and Nigeria (Table 1). Additional information on the DHS and methodology for data collection has been described in country-specific DHS reports( 20 ).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population by country; data from the most recent and pooled Demographic and Health Survey data sets*

| Burkina Faso | DRC | Ethiopia | Kenya | Mali | Niger | Nigeria | Tanzania | Uganda | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Socio-economic | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mother's employment | ||||||||||||||||||

| Not working | 1495 | 26·2 | 2305 | 33·9 | 3097 | 73·9 | 1591 | 47·0 | 2243 | 59·0 | 3957 | 80·3 | 4479 | 38·3 | 966 | 24·8 | 916 | 31·5 |

| Working | 4213 | 73·8 | 4491 | 66·1 | 1095 | 26·1 | 1795 | 53·0 | 1559 | 41·0 | 973 | 19·7 | 7224 | 61·7 | 2928 | 75·2 | 1993 | 68·5 |

| Mother's education | ||||||||||||||||||

| No schooling | 4750 | 83·2 | 1234 | 18·2 | 2798 | 66·7 | 809 | 11·5 | 3109 | 81·8 | 4203 | 85·3 | 5573 | 47·6 | 758 | 19·4 | 371 | 12·7 |

| Primary education | 621 | 10·9 | 2886 | 42·5 | 1204 | 28·7 | 3845 | 54·7 | 335 | 8·8 | 474 | 9·6 | 2082 | 17·8 | 2483 | 63·8 | 1863 | 64·0 |

| Secondary education or above | 337 | 5·9 | 2677 | 39·4 | 191 | 4·5 | 2370 | 33·8 | 358 | 9·4 | 248 | 5·0 | 4057 | 34·6 | 654 | 16·8 | 679 | 23·3 |

| Household wealth | ||||||||||||||||||

| Poor | 2379 | 41·7 | 3004 | 44·2 | 1910 | 45·6 | 3162 | 45·0 | 1539 | 40·5 | 1950 | 39·6 | 5331 | 45·5 | 1779 | 45·7 | 1289 | 44·3 |

| Middle | 2465 | 43·2 | 2634 | 38·8 | 1614 | 38·5 | 2482 | 35·3 | 1587 | 41·8 | 2072 | 42·0 | 4337 | 37·0 | 1476 | 37·9 | 1107 | 38·0 |

| Rich | 866 | 15·2 | 1159 | 17·1 | 669 | 16·0 | 1380 | 19·7 | 676 | 17·8 | 908 | 18·4 | 2044 | 17·5 | 640 | 16·4 | 517 | 17·8 |

| Health service | ||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency of ANC visits | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 208 | 3·6 | 683 | 10·1 | 2373 | 56·6 | 276 | 3·9 | 954 | 25·1 | 617 | 12·5 | 4141 | 35·4 | 92 | 2·4 | 162 | 5·6 |

| 1–3 | 3629 | 63·6 | 2927 | 43·1 | 1085 | 25·9 | 2908 | 41·4 | 1277 | 33·6 | 2655 | 53·9 | 1556 | 13·3 | 1931 | 49·6 | 1408 | 48·3 |

| ≥4 | 1872 | 32·8 | 3185 | 46·9 | 735 | 17·5 | 3838 | 54·7 | 1571 | 41·3 | 1658 | 33·6 | 6015 | 51·4 | 1871 | 48·0 | 1343 | 46·1 |

| Place of birth | ||||||||||||||||||

| Home | 1484 | 26·0 | 1342 | 19·8 | 3717 | 88·6 | 2425 | 34·6 | 1597 | 42·0 | 3237 | 65·7 | 7296 | 62·3 | 1335 | 34·3 | 981 | 33·7 |

| Health facility | 4225 | 74·0 | 5453 | 80·3 | 476 | 11·4 | 4591 | 65·4 | 2205 | 58·0 | 1693 | 34·4 | 4416 | 37·7 | 2560 | 65·7 | 1931 | 66·3 |

| PNC visits | ||||||||||||||||||

| None | 847 | 14·8 | 3536 | 52·0 | 3825 | 91·2 | 5056 | 72·0 | 2067 | 54·4 | 2902 | 58·9 | 6815 | 58·2 | 2519 | 64·6 | 1873 | 64·3 |

| 0–2 d | 2210 | 38·7 | 1027 | 15·1 | 143 | 3·4 | 1150 | 16·4 | 1181 | 31·1 | 1328 | 26·9 | 3389 | 28·9 | 516 | 13·3 | 545 | 18·7 |

| 3–42 d | 2653 | 46·5 | 2234 | 32·9 | 225 | 5·4 | 818 | 11·6 | 554 | 14·6 | 701 | 14·2 | 1508 | 12·9 | 859 | 22·1 | 494 | 17·0 |

| Individual | ||||||||||||||||||

| Child gender | ||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 2894 | 50·7 | 3404 | 50·1 | 2166 | 51·7 | 3589 | 51·1 | 1924 | 50·6 | 2478 | 50·3 | 5869 | 50·1 | 1974 | 50·7 | 1448 | 49·7 |

| Female | 2816 | 49·3 | 3393 | 49·9 | 2027 | 48·4 | 3435 | 48·9 | 1878 | 49·4 | 2452 | 49·7 | 5843 | 49·9 | 1920 | 49·3 | 1465 | 50·3 |

| Child age (months) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0–5 | 1504 | 26·4 | 1935 | 28·5 | 1248 | 29·8 | 1673 | 23·8 | 974 | 25·6 | 1480 | 30·0 | 2926 | 25·0 | 855 | 22·0 | 784 | 26·9 |

| 6–11 | 1469 | 25·7 | 1747 | 25·7 | 1111 | 26·5 | 1871 | 26·6 | 1061 | 27·9 | 1279 | 25·9 | 3198 | 27·3 | 957 | 25·0 | 811 | 27·9 |

| 12–17 | 1451 | 25·4 | 1363 | 20·1 | 834 | 19·9 | 1589 | 22·6 | 890 | 23·4 | 841 | 17·1 | 2282 | 19·5 | 1074 | 28·2 | 637 | 21·9 |

| 18–23 | 1286 | 22·5 | 1753 | 25·8 | 1000 | 23·9 | 1892 | 26·9 | 877 | 23·1 | 1331 | 27·0 | 3306 | 28·2 | 918 | 24·8 | 680 | 23·4 |

| Mother's age (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 15–24 | 2005 | 35·1 | 2323 | 34·2 | 1282 | 30·6 | 2697 | 38·4 | 1287 | 33·8 | 1618 | 32·8 | 3629 | 31·0 | 1556 | 40·0 | 1120 | 38·5 |

| 25–34 | 2586 | 45·3 | 3201 | 47·1 | 2077 | 49·5 | 3307 | 47·1 | 1840 | 48·4 | 2385 | 48·4 | 5675 | 48·5 | 1606 | 41·3 | 1281 | 44·0 |

| 35–49 | 1118 | 19·6 | 1273 | 18·7 | 834 | 19·9 | 1020 | 14·5 | 675 | 17·8 | 927 | 18·8 | 2408 | 20·6 | 732 | 18·7 | 511 | 17·6 |

| Household | ||||||||||||||||||

| Household location | ||||||||||||||||||

| Urban | 982 | 17·2 | 2104 | 31·0 | 557 | 13·3 | 2456 | 35·0 | 768 | 20·2 | 677 | 13·7 | 4180 | 35·7 | 1059 | 27·2 | 419 | 14·4 |

| Rural | 4728 | 82·8 | 4694 | 69·1 | 3635 | 86·7 | 4568 | 65·0 | 3034 | 79·8 | 4254 | 86·3 | 7533 | 64·3 | 2835 | 72·8 | 2493 | 85·6 |

DRC, Demographic Republic of Congo; ANC, antenatal clinic; PNC, postnatal clinic.

Burkina Faso (2010), N 5710; DRC (2013), N 6797; Ethiopia (2013), N 4193; Kenya (2014), N 7024; Mali (2013), N 3802; Niger (2013), N 4930; Nigeria (2013), N 11 712; Tanzania (2015), N 3894; and Uganda (2010), N 2913.

Outcome

The main outcomes were the breast-feeding indicators (early initiation of breast-feeding, exclusive breast-feeding (EBF), predominant breast-feeding and bottle-feeding), selected based on previous published studies( 15 , 17 , 21 ), which were assessed based on the following WHO definitions for infant and young child feeding practices( 22 ).

-

∙

Early (timely) initiation of breast-feeding: The proportion of children 0–23 months of age who were put to the breast within one hour of birth.

-

∙

Exclusive breast-feeding: The proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk as the only source of nourishment, but allows oral rehydration solution, drops, or syrups of vitamins and medicines.

-

∙

Predominant breast-feeding: The proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk as the main source of nourishment, but allows water, water-based drinks, fruit juice, oral rehydration solution, drops, or syrups of vitamins and medicines.

-

∙

Bottle-feeding: The proportion of infants 0–23 months of age who received any liquid (including breast milk) or semi-solid food from a bottle with a nipple/teat.

The WHO considered bottle-feeding an important breast-feeding measure because of its impact on optimal breast-feeding practices, and the association between bottle-feeding and increased diarrhoeal morbidity and mortality( 22 ).

Study factors

The independent variables included socio-economic, health service and individual variables selected based on previously published studies( 14 , 16 , 23 ). Socio-economic characteristics included the mother’s educational level (categorised as no education, primary education or secondary education or above), employment status (categorised as not working or working) and household wealth index (categorised as poor, middle or rich). The household wealth index was calculated as a score of household assets, which was derived from a principal component analysis conducted by each in-country population commission or department of health in collaboration with ICF International. Health service factors included the number of antenatal clinic (ANC) visits (categorised as no ANC visit, one to three ANC visits, or four or more ANC visits), the place of delivery (categorised as home or health facility) and the timing of postnatal clinic (PNC) visits (categorised as no PNC visits, 0–2 d PNC visits or 3–42 d PNC visits). The individual factor was maternal age (categorised as 15–24 years, 25–34 years or 35–49 years).

Statistical analysis

Preliminary analyses involved calculations of prevalence estimates and frequency tabulations to describe data for each study factor (i.e. socio-economic, health service and individual variables). Prevalence (and corresponding 95 % CI) of breast-feeding indicators were estimated using the ‘svy’ function to adjust for sampling weights to ensure generalisability of the survey results at the national level.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models that expressed country as an ordinal variable and adjusted for maternal marital status, place of residence, child’s age and gender as confounders were used to investigate the association between study factors and breast-feeding in the nine SSA countries, using ‘xlogit’ command to estimate the OR. The models were restricted to the youngest living child aged less than 24 months living with the respondent (woman aged 15–49 years) to minimise recall bias, consistent with previous studies( 8 , 24 ). All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical software package Stata version 13.0.

Ethics

Ethical approvals for data collection and subsequent analyses were obtained by Measure DHS project from country-specific research ethics committee before the surveys were conducted. These ethics committees included: Burkina Faso National Ethical Committee (Burkina Faso); Ethics Committee of the Demographic Republic of Congo Ministry of Planning (Demographic Republic of Congo); National Ethics Review Committee of the Ethiopia Science and Technology Commission (Ethiopia); Scientific and Ethical Review Committee of the Kenya Medical and Research Institute (Kenya); Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Odonto-stomatology, University of Bamako (Mali); National Consultative Ethics Committee of the Niger Ministry of Health (Niger); National Health Research Ethics Committee (Nigeria); National Health Research Ethical Committee (Tanzania); and Research and Ethics Committee, Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (Uganda). Permission to use the data was sought from Measure DHS/ICF International, and approval was granted.

Results

Prevalence of breast-feeding indicators

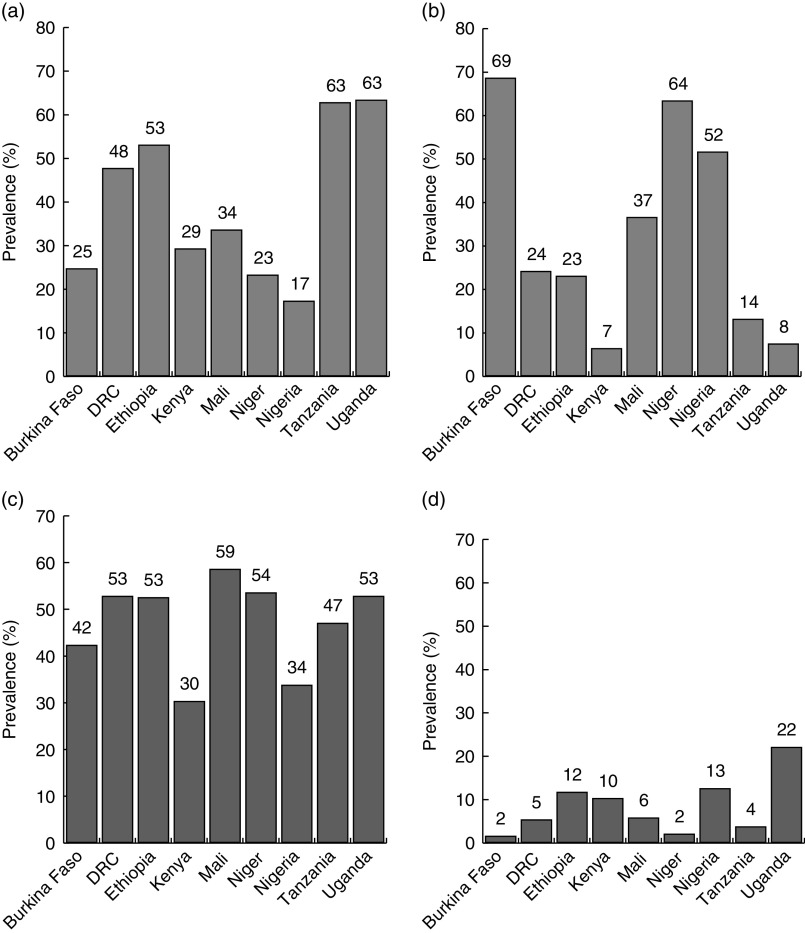

The overall prevalence of EBF in SSA with high diarrhoea mortality was 34·3 %; highest in Uganda at 63·4 %, Tanzania at 63·3 % and Ethiopia at 53·2 %, but lowest in Nigeria at 17·4 % and Niger at 23·4 % (Fig. 1). With the exception of Kenya at 6·5 %, Uganda at 7·6 % and Tanzania at 14·2 %, prevalence of predominant breast-feeding was higher for other countries, ranging from 23·3 % in Ethiopia to 68·7 % in Burkina Faso. Among the SSA countries, the prevalence of timely initiation of breast-feeding was highest in Mali (58·7 %), but lowest in Kenya and Nigeria (30·4 and 33·9 %, respectively). The prevalence of bottle-feeding was highest in Uganda (22·2 %), Nigeria (12·7 %) and Ethiopia (11·8 %), but lowest in Burkina Faso (1·7 %) and Niger (2·1 %).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of breast-feeding practices in sub-Saharan African countries with high diarrhoea mortality: (a) exclusive breast-feeding; (b) predominant breast-feeding; (c) early initiation of breast-feeding; (d) bottle-feeding. Data from the most recent and pooled Demographic and Health Survey data sets for 50 975 children under 24 months of age: Burkina Faso (2010), N 5710; Demographic Republic of Congo (DRC; 2013), N 6797; Ethiopia (2013), N 4193; Kenya (2014), N 7024; Mali (2013), N 3802; Niger (2013), N 4930; Nigeria (2013), N 11 712; Tanzania (2015), N 3894; and Uganda (2010), N 2913. Early initiation of breast-feeding=the proportion of children 0–23 months of age who were put to the breast within one hour of birth; exclusive breast-feeding=the proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk as the only source of nourishment, but allows oral rehydration solution, drops, or syrups of vitamins and medicines; predominant breast-feeding=the proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk as the main source of nourishment, but allows water, water-based drinks, fruit juice, oral rehydration solution, drops, or syrups of vitamins and medicines; bottle-feeding=the proportion of infants 0–23 months of age who received any liquid (including breast milk) or semi-solid food from a bottle with a nipple/teat

Determinants of breast-feeding in sub-Saharan African countries with high diarrhoea mortality

Mothers with a secondary level of education or above were more likely to exclusively breast-feed their infants compared with mothers with no education (adjusted OR (AOR)=1·30; 95 % CI 1·14, 1·47; P<0·001; Table 2). Employed mothers were less likely to exclusively breast-feed compared with mothers not in employment (AOR=0·84; 95 % CI 0·77, 0·92; P<0·001). The odds for EBF were significantly higher in mothers who had frequent ANC visits (AOR=1·22; 95 % CI 1·07, 1·38; P=0·003 for 1–3 ANC visits and AOR=1·31; 95 % CI 1·14, 1·49; P<0·001 for ≥4 ANC visits). Delivery at a health facility and higher frequency of PNC visits were significantly associated with EBF (AOR=1·24; 95 % CI 1·11, 1·39; P<0·001 for health facility delivery and AOR=1·22; 95 % CI 1·10, 1·36; P<0·001 for 0–2 d PNC visits).

Table 2.

Determinants of exclusive breast-feeding and predominant breast-feeding in nine sub-Saharan African countries with high burden of diarrhoea mortality; data from the most recent and pooled Demographic and Health Survey data sets for 50 975 children under 24 months of age*

| Exclusive breast-feeding | Predominant breast-feeding | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Sample | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||||||

| Size (n †) | % | OR | 95 % CI | P | OR | 95 % CI | P | Size (n †) | % | OR | 95 % CI | P | OR | 95 % CI | P | |

| Socio-economic | ||||||||||||||||

| Maternal education | ||||||||||||||||

| No education | 1780 | 27·9 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 3221 | 50·4 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| Primary education | 1690 | 41·5 | 1·31 | 1·18, 1·45 | <0·001 | 1·18 | 1·06, 1·32 | 0·001 | 946 | 23·2 | 0·80 | 0·72, 0·91 | <0·001 | 0·87 | 0·77, 0·97 | <0·001 |

| Secondary education or above | 1107 | 38·3 | 1·58 | 1·40, 1·76 | <0·001 | 1·30 | 1·14, 1·47 | <0·001 | 721 | 24·9 | 0·54 | 0·48, 0·61 | <0·001 | 0·65 | 0·56, 0·74 | <0·001 |

| Maternal employment | ||||||||||||||||

| Not working | 2621 | 39·0 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 2642 | 39·3 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| Working | 1955 | 34·0 | 0·85 | 0·78, 0·92 | <0·001 | 0·84 | 0·77, 0·92 | <0·001 | 2248 | 39·1 | 0·95 | 0·87, 1·04 | 0·281 | 0·96 | 0·87, 1·05 | 0·395 |

| Household wealth | ||||||||||||||||

| Poor | 1865 | 31·6 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 2349 | 39·8 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| Middle | 1902 | 36·3 | 1·23 | 1·12, 1·34 | <0·001 | 1·01 | 1·00, 1·20 | 0·043 | 1894 | 36·1 | 0·78 | 0·71, 0·86 | <0·001 | 0·90 | 0·81, 0·99 | 0·043 |

| Rich | 810 | 36·6 | 1·27 | 1·13, 1·42 | <0·001 | 0·96 | 0·83, 1·11 | 0·632 | 647 | 29·3 | 0·61 | 0·54, 0·69 | <0·001 | 0·87 | 0·73, 1·02 | 0·106 |

| Health service | ||||||||||||||||

| ANC visits | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 743 | 28·7 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1077 | 41·7 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| 1–3 | 2028 | 35·6 | 1·40 | 1·23, 1·58 | <0·001 | 1·22 | 1·07, 1·38 | 0·003 | 2092 | 37·1 | 0·88 | 0·78, 0·99 | 0·037 | 1·05 | 0·92, 1·19 | 0·416 |

| ≥4 | 1806 | 35·2 | 1·58 | 1·40, 1·78 | <0·001 | 1·31 | 1·14, 1·49 | <0·001 | 1721 | 33·5 | 0·70 | 0·62, 0·78 | <0·001 | 0·95 | 0·84, 1·09 | 0·527 |

| Place of birth | ||||||||||||||||

| Home | 1900 | 30·0 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 2682 | 42·4 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| Health facility | 2677 | 38·1 | 1·42 | 1·30, 1·54 | <0·001 | 1·24 | 1·11, 1·39 | <0·001 | 2207 | 31·4 | 0·63 | 0·58, 0·69 | <0·001 | 0·77 | 0·68, 0·86 | <0·001 |

| PNC visits | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 2516 | 32·2 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 2652 | 33·9 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| 0–2 d | 1079 | 36·0 | 1·76 | 1·59, 1·95 | <0·001 | 1·22 | 1·10, 1·36 | <0·001 | 1272 | 42·4 | 0·77 | 0·70, 0·86 | <0·001 | 0·89 | 0·79, 1·00 | 0·056 |

| 3–42 d | 982 | 38·6 | 1·60 | 1·43, 1·78 | <0·001 | 1·02 | 1·02, 1·28 | 0·018 | 966 | 38·0 | 0·75 | 0·67, 0·85 | <0·001 | 0·69 | 0·60, 0·79 | <0·001 |

| Individual | ||||||||||||||||

| Maternal age | ||||||||||||||||

| 15–24 years | 1711 | 34·8 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1791 | 36·4 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| 25–34 years | 2117 | 34·7 | 1·02 | 0·94, 1·11 | 0·532 | 1·09 | 1·00, 1·20 | 0·051 | 2245 | 36·8 | 0·88 | 0·81, 0·97 | 0·011 | 0·86 | 0·79, 0·95 | 0·003 |

| 35–49 years | 749 | 32·1 | 0·91 | 0·81, 10·2 | 0·129 | 1·01 | 0·89, 1·14 | 0·838 | 854 | 36·6 | 0·88 | 0·78, 1·00 | 0·050 | 0·83 | 0·73, 0·94 | 0·003 |

DRC, Demographic Republic of Congo; ANC, antenatal clinic; PNC, postnatal clinic; Ref., reference category.

Exclusive breast-feeding=infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk as the only source of nourishment (but allows oral rehydration solution, drops, or syrups of vitamins and medicines); predominant breast-feeding=infants 0–5 months of age who received breast milk as the predominant source of nourishment (but allows water and water-based drinks fruit juice, ritual fluids, oral rehydration solution, syrups or drops of vitamins).

Multivariate models adjusted for the potential confounding factors of maternal marital status, place of residence, child’s age and gender.

Burkina Faso (2010), N 5710; DRC (2013), N 6797; Ethiopia (2013), N 4193; Kenya (2014), N 7024; Mali (2013), N 3802; Niger (2013), N 4930; Nigeria (2013), N 11 712; Tanzania (2015), N 3894; and Uganda (2010), N 2913.

Number of children aged 0–5 months who were exclusively or predominantly breast-fed.

The odds for predominant breast-feeding were significantly lower in educated mothers (AOR=0·87; 95 % CI 0·77, 0·97; P<0·001 for primary education and AOR=0·65; 95 % CI 0·56, 0·74; P<0·001 for secondary education or above) and mothers who delivered at a health facility (AOR=0·77; 95 % CI 0·68, 0·86; P<0·001; Table 2). Higher frequency of PNC visits and higher maternal age were significantly associated with lower likelihood for predominant breast-feeding (AOR=0·69; 95 % CI 0·60, 0·79; P<0·001 for 3–42 d PNC visits; AOR=0·86; 95 % CI 0·79, 0·95; P=0·003 for age 25–34 years and AOR=0·83; 95 % CI 0·73, 0·94; P<0·003 for age 35–49 years).

Mothers who delivered their babies at a health facility were significantly more likely to initiate breast-feeding within the first hour of birth compared to those who delivered at home (AOR=1·48; 95 % CI 1·40, 1·56; P<0·001). Improved household wealth (rich) and higher frequency of ANC visits were significantly associated with timely initiation of breast-feeding (Table 3).

Table 3.

Determinants of early initiation of breast-feeding and bottle-feeding in nine sub-Saharan African countries with high burden of diarrhoea mortality; data from the most recent and pooled Demographic and Health Survey data sets for 50 975 children under 24 months of age*

| Timely initiation of breast-feeding | Bottle-feeding | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Sample | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||||||

| Size (n †) | % | OR | 95 % CI | P | OR | 95 % CI | P | Size (n †) | % | OR | 95 % CI | P | OR | 95 % CI | P | |

| Socio-economic | ||||||||||||||||

| Maternal education | ||||||||||||||||

| No education | 10 607 | 44·7 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1075 | 4·5 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| Primary education | 6731 | 43·7 | 1·07 | 1·02, 1·12 | 0·004 | 0·95 | 0·90, 1·00 | 0·061 | 1437 | 9·3 | 1·49 | 1·36, 1·63 | <0·001 | 1·19 | 1·08, 1·31 | 0·001 |

| Secondary education or above | 4829 | 43·3 | 1·21 | 1·15, 1·28 | <0·001 | 0·94 | 0·88, 1·00 | 0·074 | 1756 | 15·8 | 2·84 | 2·60, 3·11 | <0·001 | 1·64 | 1·46, 1·83 | <0·001 |

| Maternal employment | ||||||||||||||||

| Not working | 10 227 | 49·2 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1873 | 9·0 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| Working | 11 939 | 46·4 | 1·00 | 0·96, 1·04 | 0·883 | 0·99 | 0·95, 1·03 | 0·791 | 2393 | 9·2 | 0·98 | 0·92, 1·06 | 0·731 | 0·98 | 0·91, 1·05 | 0·667 |

| Household wealth | ||||||||||||||||

| Poor | 8970 | 40·8 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1235 | 5·6 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| Middle | 8949 | 45·8 | 1·16 | 1·11, 1·21 | <0·001 | 1·08 | 1·03, 1·14 | <0·001 | 1595 | 8·1 | 1·48 | 1·37, 1·61 | <0·001 | 1·20 | 1·09, 1·31 | <0·001 |

| Rich | 4252 | 49·1 | 1·44 | 1·36, 1·52 | <0·001 | 1·21 | 1·12, 1·31 | <0·001 | 1438 | 16·9 | 3·40 | 3·11, 3·71 | <0·001 | 2·02 | 1·78, 2·29 | <0·001 |

| Health service | ||||||||||||||||

| ANC visits | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 3725 | 39·3 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 694 | 7·3 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| 1–3 | 8790 | 45·6 | 1·24 | 1·17, 1·31 | <0·001 | 1·09 | 1·02, 1·16 | 0·004 | 1211 | 6·3 | 1·37 | 1·23, 1·52 | <0·001 | 1·01 | 0·90, 1·14 | 0·795 |

| ≥4 | 9655 | 45·1 | 1·43 | 1·35, 1·51 | <0·001 | 1·17 | 1·10, 1·25 | <0·001 | 2362 | 11·0 | 1·93 | 1·75, 2·13 | <0·001 | 1·14 | 1·02, 1·27 | 0·021 |

| Place of birth | ||||||||||||||||

| Home | 9328 | 39·5 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1592 | 6·7 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| Health facility | 12 842 | 48·3 | 1·52 | 1·45, 1·58 | <0·001 | 1·48 | 1·40, 1·56 | <0·001 | 2675 | 10·1 | 1·91 | 1·78, 2·06 | <0·001 | 1·04 | 0·94, 1·14 | 0·389 |

| PNC visits | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 11 368 | 40·1 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1982 | 6·8 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| 0–2 d | 5771 | 50·5 | 1·72 | 1·64, 1·80 | <0·001 | 1·18 | 1·12, 1·24 | <0·001 | 1286 | 11·2 | 2·34 | 2·16, 2·54 | <0·001 | 1·19 | 1·08, 1·31 | <0·001 |

| 3–42 d | 4762 | 48·9 | 1·47 | 1·39, 1·55 | <0·001 | 1·03 | 0·98, 1·09 | 0·206 | 1000 | 10·3 | 2·58 | 2·37, 2·82 | <0·001 | 1·33 | 1·20, 1·47 | <0·001 |

| Individual | ||||||||||||||||

| Maternal age | ||||||||||||||||

| 15–24 years | 7223 | 42·2 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1490 | 8·7 | 1·00 | Ref. | – | 1·00 | Ref. | – |

| 25–34 years | 10 705 | 45·2 | 1·15 | 1·10, 1·20 | <0·001 | 1·16 | 1·11, 1·22 | <0·001 | 2041 | 8·6 | 1·04 | 0·96, 1·11 | 0·275 | 1·02 | 0·95, 1·11 | 0·485 |

| 35–49 years | 4243 | 45·2 | 1·15 | 1·09, 1·21 | <0·001 | 1·18 | 1·11, 1·25 | <0·001 | 737 | 7·9 | 0·90 | 0·82, 0·99 | 0·041 | 1·01 | 0·91, 1·12 | 0·755 |

DRC, Demographic Republic of Congo; ANC, antenatal clinic; PNC, postnatal clinic; Ref., reference category.

Timely initiation of breast-feeding=children 0–23 months of age who were put to the breast within one hour of birth; bottle-feeding=children 0–23 months of age who received any liquid (including breast milk) or semi-solid food from a bottle with a nipple/teat.

Multivariate models adjusted for the potential confounding factors of maternal marital status, place of residence, child’s age and gender.

Burkina Faso (2010), N 5710; DRC (2013), N 6797; Ethiopia (2013), N 4193; Kenya (2014), N 7024; Mali (2013), N 3802; Niger (2013), N 4930; Nigeria (2013), N 11 712; Tanzania (2015), N 3894; and Uganda (2010), N 2913.

Number of children aged 0–23 months who were timely initiated to breast milk or bottle-fed.

Educated mothers were more likely to bottle-feed their babies compared with mothers with no education (AOR=1·64; 95 % CI 1·46, 1·83; P<0·001 for secondary education or above; Table 3). Improved household wealth (middle and rich) was significantly associated with higher likelihood for bottle-feeding (AOR=1·20; 95 % CI 1·09, 1·31; P<0·001 for middle household wealth and AOR=2·02; 95 % CI 1·78, 2·29; P<0·001 for rich household wealth). Higher frequency of PNC visits was associated with bottle-feeding (AOR=1·33; 95 % CI 1·20, 1·47; P<0·001 for 3–42 d visits).

Discussion

In SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality, EBF prevalence was higher in Uganda, Ethiopia and Tanzania, but lower in Nigeria and Niger. Predominant breast-feeding was lower in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, but higher in Burkina Faso. Prevalence of timely initiation of breast-feeding was highest in Mali, while bottle-feeding rate was highest in Uganda, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Kenya. Higher educational attainment and frequent health-service contacts of mothers (i.e. ANC visits, PNC visits and delivery at a health facility) were associated with EBF. Frequent ANC visits, higher household wealth and delivery at a health facility were associated with timely initiation of breast-feeding. Mothers with education and those from wealthier households were more likely to bottle-feed.

Epidemiology of breast-feeding in sub-Saharan African countries with high diarrhoea mortality

Previous population-based studies conducted in SSA countries reported that the overall prevalence of EBF was 36 %( 25 ) and that the proportion of mothers who continued to breast-feed at 12 months was among the highest globally( 26 ). The authors found that EBF prevalence was highest in Rwanda, Malawi, Burundi, Ghana and Zambia, but lowest in Guinea, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone and Gabon( 25 ). Consistent with a previous study( 25 ), our study – which was specific to countries with high diarrhoea mortality – found that EBF rates were higher in Tanzania and Ethiopia, but lower in Nigeria and Niger. The previous study did not provide estimates for Uganda, which had the highest EBF prevalence in our analysis. A study from Tanzania found that 46 % of mothers initiated breast-feeding within the first hour of birth and that 16 % predominantly breast-fed( 16 ), which is consistent with our findings.

Nationally representative epidemiological studies that focus on key breast-feeding practices are limited in many SSA countries, including Niger, Mali, Uganda and Democratic Republic of Congo, compared with Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania. The present findings were consistent with studies from SSA which showed that lower maternal education, maternal employment, young maternal age, fewer visits to health facilities and lower household wealth were associated with suboptimal breast-feeding( 16 , 17 , 25 , 27 ). Other contextual factors that have been shown to negatively impact optimal breast-feeding in SSA with high diarrhoea mortality include: a cultural belief system that seldom supports optimal breast-feeding( 23 ); parents’ preference for a male child; limited family and political support; poor financial investment; limited enforcement of the Code; and fragmented health systems with poor support for the BFHI( 28 , 29 ). Determinants of breast-feeding practices in SSA with high diarrhoea mortality are multifaceted; however, government measures, facility- and community-based initiatives that are comprehensive, measurable and culturally appropriate can be employed to ensure improvements in breast-feeding practices in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality( 28 ).

Policy and pragmatic implications of the findings

Our study found that countries such as Uganda (63 %), Tanzania (63 %) and Ethiopia (53 %) currently have higher EBF rates than Global Nutrition Target 5 (which is to increase the EBF rate to at least 50 % by 2025)( 30 ). Despite these in-country achievements, sustained efforts are still needed to ensure that EBF rates remain on an upward trajectory, particularly given the higher rates of bottle-feeding in Uganda and Ethiopia. A multicentre large-scale community-based initiative conducted in Bolivia, Ghana and Madagascar, with appropriate funding from an international donor, resulted in improvements in breast-feeding practices( 31 ). Evaluation of breast-feeding initiatives in countries such as Nigeria, Niger, Burkina Faso and Kenya (with low EBF rates), and the full implementation of context-specific and cost-effective community-based interventions that seek to improve breast-feeding practices, are warranted in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality. Improvements in breast-feeding practices will not only result in the achievement of Global Nutrition Target 5( 30 ), but also are a key aspect to attain Sustainable Development Goal 3 of ending preventable deaths among under-5s( 32 ).

Evidence from Sri Lanka revealed that improvements in breast-feeding practices were observed over a 10-year period as a result of interventions at national and sub-national levels. The initiatives included high-level political support for breast-feeding programmes, effective and clear transmission of breast-feeding messages through multiple communication networks, and a culture supportive of breast-feeding( 33 ). National-level policy, programme and coordination for breast-feeding interventions are present in many SSA countries, including Tanzania( 34 ), Nigeria( 35 ), Uganda( 36 ), Kenya( 37 ) and Ethiopia( 38 ). However, limited resources, a dependence on donor funding and a lack of sub-national breast-feeding committees have been flagged as challenges to improving breast-feeding outcomes in those countries. Scaling up efforts to achieving the Global Nutrition Targets in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality would require the creation and strengthening of sub-national breast-feeding committees and increased public health financing, galvanised by strong political resolve at all levels of government( 28 , 33 ). Integrated networks of both national and sub-national breast-feeding committees that coordinate and advocate for breast-feeding at the health system and community levels would also maximise impacts.

The present study found that maternal employment and lower household wealth were associated with suboptimal breast-feeding practices. In many SSA countries, employed mothers are entitled to 3 months of fully paid maternity leave, but this time period is inadequate for mothers to appropriately engage in optimal EBF. Evidence from Canada( 39 ) and Scotland( 40 ) has shown that the expansion of maternity leave and appropriate employer-driven support for female employees post-birth were associated with optimal breast-feeding behaviours. Legislative changes to employment regulations to allow employed mothers to appropriately breast-feed their infants are continuing in SSA countries. For instance, a regional Nigerian government recently increased paid maternity leave from 3 to 6 months for female public servants and initiated a 10 d paid paternity leave for male public workers, with a view to promote optimal infant feeding and improve household income and productivity( 17 ). Similarly, efforts are ongoing in Kenya to extend the maternity leave from 3 to 6 months, with the promotion of breast-feeding as part of the rationale for the proposed policy( 41 ). In Tanzania, labour regulations were recently amended to allow female employees to breast-feed for 2 h during working hours for at least six consecutive months, after 3 months of fully paid maternity leave( 42 ). These workplace changes in the form of legislation are needed at the national level in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality to improve breast-feeding practices.

In addition, a cohort study from the UK revealed that incentives for employers to support breast-feeding mothers promulgate employer-driven support for optimal breast-feeding( 43 ). In SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality, economic incentives (such as tax rebates) to private employers and self-employed mothers may be required to provide environments conducive for breast-feeding (such as provision of crèches or breast-feeding breaks). The enforcement of the Labour Act to maternity protection (particularly among private employers) and establishment of measures to monitor compliance are also proposed as adjuncts to improve breast-feeding behaviours of employed mothers( 28 ).

Our study showed that bottle-feeding rates were highest in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda (≥10 %). This was despite Uganda’s high rate of EBF at 63 %. The Code seeks to protect, promote and support breast-feeding at the facility and community levels and has been adopted and streamlined as legislation in all SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality, with the exception of Kenya, where compliance to the Code remains voluntary( 44 ). For example, in Nigeria, the Code was ratified as the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control Act (as amended)( 35 ), and as the Food and Drugs Act of 1997 in Uganda( 44 ). Reports of violation of the Code are numerous in many developing countries( 35 , 45 – 48 ), including Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Uganda, with subsequent increase in infant formula sales and impact on bottle-feeding( 49 ). The Code violation has been largely attributed to a lack of enforcement and training for officers( 50 ), as well as the marketing strategies of infant food manufacturers( 51 ). Capacity development for enforcement officials, health workers and key stakeholders, as well as proper enforcement of the Code and adequate funding for enforcement institutions, are also needed as strategies to reduce the increasing trends in utilisation of infant formula in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality( 28 , 49 ).

Previous studies from developing countries (including Kenya, Nigeria and Uganda) have indicated that the BFHI has been influential in improving breast-feeding behaviours( 52 – 56 ). The present study found that fewer contacts with the health facility (i.e. limited ANC and PNC visits or home birthing) were associated with suboptimal breast-feeding practices. Strengthening the BFHI in the form of continued training for health professionals and traditional birth attendants, as well as the incorporation of the Baby Friendly Community Initiative (BFCI) in scale-up efforts would maximise breast-feeding outcomes in SSA countries, particularly in communities with a higher proportion of home birthing and poor health-service use. Monitoring and evaluation strategies of BFHI-certified facilities as set out in the establishment of the BFHI will also have a positive impact on breast-feeding rates.

The WHO and UNICEF developed the BFCI to promote and support optimal breast-feeding at the community level( 57 ). In SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality, family members have an influence on new mothers and provide necessary support to mothers post-birth, but their advice may reflect cultural beliefs which may not promote optimal breast-feeding( 58 ). Studies have indicated that community-based interventions that involved a close family member and postnatal home visits resulted in improvement in breast-feeding behaviours( 33 , 59 ). Our study showed that most mothers gave birth at home in Ethiopia, Niger and Nigeria. Aspects of the BFCI may increase utilisation of health services among mothers, with subsequent impact on breast-feeding rates. Community-based breast-feeding initiatives (e.g. BFCI) should be incorporated into infant nutrition programmes in high-priority areas and should be tailored to the specific sociocultural and socio-economic environment in which mothers live to maximise health outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

The present study has specific limitations. First, the breast-feeding indicators were collected as self-reported measures, and this may have resulted in a recall and/or measurement bias. These measures may have underestimated and overestimated the association between study factors and breast-feeding practices. Second, unmeasured confounding factors (e.g. culture, partner support or maternal health status following childbirth) may have affected the study results. Finally, the establishment of a temporal association between study factors and breast-feeding indicators is challenging given that we employed cross-sectional data. Despite these limitations, the study findings are nationally representative for each country studied. We believe that selection bias is unlikely to have affected the study findings because of the high response rates in the surveys (96–99 %). Our study provided evidence on key breast-feeding practices in nine SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality, using reliable and comparable data that were collected with a standardised questionnaire across geographical regions.

Conclusion

The present study found that EBF prevalence was low and varied across SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality; higher in Uganda, Ethiopia and Tanzania, but lower in Nigeria and Niger. Determinants of suboptimal breast-feeding included no maternal education, low household wealth and limited contact with health services. Mothers from wealthier households and those with higher educational attainment engaged in bottle-feeding. To improve breast-feeding practices in SSA countries with high diarrhoea mortality, infant feeding initiatives should target all mothers, particularly women from poor households and those with limited access to health services. In addition, targeting mothers from high-income households will also increase breast-feeding rates.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to Measure DHS/ICF International for providing the data for the analysis. Financial support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Authorship: F.A.O. conceptualised the study, obtained the data, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript and critically revised the manuscript. K.E.A., A.P. and J.E. contributed to the conceptualisation of the study, analyses and interpretation of the data, and critically revised the manuscript. All other authors contributed to acquisition and interpretation of data, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approvals for data collection and subsequent analyses were obtained by Measure DHS project from each country-specific research ethics committee before the surveys were conducted. Measure DHS/ICF International granted permission to use the data.

References

- 1. Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R et al. (2015) Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Paediatr 104, 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (2013) Short-Term Effects of Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review of the Benefits of Breastfeeding on Diarhoea and Pneumonia Mortality. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Edmond KM, Zandoh C, Quigley MA et al. (2006) Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics 117, 380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ et al. (2016) Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 387, 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horta B, Bahl R, Martines JC et al. (2013) Evidence on the Long-Term Effects of Breastfeeding: Systematic Reveiew and Meta-Analysis. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cai X, Wardlaw T & Brown DW (2012) Global trends in exclusive breastfeeding. Int Breastfeed J 7, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. UNICEF/World Health Organization (2010) Diarrhoea: Why Children Are Still Dying and What Can Be Done. New York/Geneva: UNICEF/WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ogbo FA, Page A, Idoko J et al. (2016) Diarrhoea and suboptimal feeding practices in nigeria: evidence from the National Household Surveys. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 30, 346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clemens J, Elyazeed RA, Rao M et al. (1999) Early initiation of breastfeeding and the risk of infant diarrhea in rural Egypt. Pediatrics 104, e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arifeen S, Black RE, Antelman G et al. (2001) Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute respiratory infection and diarrhea deaths among infants in Dhaka slums. Pediatrics 108, e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hajeebhoy N, Nguyen H, Mannava P et al. (2014) Suboptimal breastfeeding practices are associated with infant illness in Vietnam. Int Breastfeed J 9, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogbo FA, Agho K, Ogeleka P et al. (2017) Infant feeding practices and diarrhoea in sub-Saharan African countries with high diarrhoea mortality. PLoS One 12, e0171792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boschi-Pinto C, Velebit L & Shibuya K (2008) Estimating child mortality due to diarrhoea in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 86, 710–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Agho K, Dibley M, Odiase J et al. (2011) Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 11, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ogbo FA, Agho KE & Page A (2015) Determinants of suboptimal breastfeeding practices in Nigeria: evidence from the 2008 demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 15, 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Victor R, Baines SK, Agho KE et al. (2013) Determinants of breastfeeding indicators among children less than 24 months of age in Tanzania: a secondary analysis of the 2010 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey. BMJ Open 3, e001529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ogbo FA, Page A, Agho KE et al. (2015) Determinants of trends in breast-feeding indicators in Nigeria, 1999–2013. Public Health Nutr 18, 3287–3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bezner KR, Laifolo D, Shumba L et al. (2008) ‘We grandmothers know plenty’: breastfeeding, complementary feeding and the multifaceted role of grandmothers in Malawi. Soc Sci Med 66, 1095–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. UNICEF & World Health Organization (2012) Pneumonia and Diarrhoea: Tackling the Deadliest Diseases for the World’s Poorest Children. New York: UNICEF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. The Demographic and Health Survey Program (2016) Publications by country. https://dhsprogram.com/Publications/Publications-by-Country.cfm (accessed March 2017).

- 21. Bahl R, Frost C, Kirkwood BR et al. (2005) Infant feeding patterns and risks of death and hospitalization in the first half of infancy: multicentre cohort study. Bull World Health Organ 83, 418–426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization, UNICEF, US Agency for International Development et al. (2008) Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices. Part I: Definitions. Conclusions of a Consensus Meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington, DC, USA. Geneva: WHO.

- 23. Agho KE, Ogeleka P, Ogbo FA et al. (2016) Trends and predictors of prelacteal feeding practices in Nigeria (2003–2013). Nutrients 8, 462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ogbo FA, Page A, Idoko J et al. (2015) Trends in complementary feeding indicators in Nigeria, 2003–2013. BMJ Open 5, e008467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yalçin SS, Berde AS & Yalçin S (2016) Determinants of exclusive breast feeding in sub‐Saharan Africa: a multilevel approach. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 30, 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Victora CG, Horta BL, de Mola CL et al. (2015) Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Health 3, e199–e205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kimani-Murage EW, Madise NJ, Fotso J-C et al. (2011) Patterns and determinants of breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in urban informal settlements, Nairobi Kenya. BMC Public Health 11, 396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N et al. (2016) Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 387, 491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ogbo FA, Page A, Idoko J et al. (2017) Have policy responses in Nigeria resulted in improvements in infant and young child feeding practices in Nigeria? Int Breastfeed J 12, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization (2014) Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Policy Brief Series (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.2). Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Quinn VJ, Guyon AB, Schubert JW et al. (2005) Improving breastfeeding practices on a broad scale at the community level: success stories from Africa and Latin America. J Hum Lact 21, 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. United Nations (2016) Sustainable development goals. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed December 2016).

- 33. UNICEF (2010) Consolidated Report of Six-Country Review of Breastfeeding Programmes. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ministry of Health, Tanzania (2015) The World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative (WBTi) – Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria (2015) The World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative (WBTi) – Nigeria. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ministry of Health, Uganda (2015) The World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative (WBTi) – Uganda. Kampala: Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Kenya (2012) The World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative (WBTi) – Kenya. Nairobi: Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute (2013) Assessment of Status of Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) Practice, Policy and Programs: Achievements and Gaps, in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baker M & Milligan K (2008) Maternal employment, breastfeeding, and health: evidence from maternity leave mandates. J Health Econ 27, 871–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Skafida V (2012) Juggling work and motherhood: the impact of employment and maternity leave on breastfeeding duration: a survival analysis on Growing Up in Scotland data. Matern Child Health J 16, 519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Igadwah L (2017) Bill proposes three more maternity leave months. Business Daily, 1 May. http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/news/Bill-proposes-three-more-maternity-leave-months/539546-3909704-fhker1/index.html (accessed July 2017).

- 42. Velma Law V (2017) Employment And Labour Relations (General) Regulations 2017 (GN 47 2017). https://www.velmalaw.com/new-labour-regulations-2017/ (accessed July 2017).

- 43. Hawkins SS, Griffiths LJ & Dezateux C (2007) The impact of maternal employment on breast-feeding duration in the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr 10, 891–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. World Health Organization (2013) Country Implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes: Status Report 2011. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 45. UNICEF (2009) Infant and Young Child Feeding Programme Review: Study Uganda. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Aguayo VM, Ross JS, Kanon S et al. (2003) Monitoring compliance with the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes in west Africa: multisite cross sectional survey in Togo and Burkina Faso. BMJ 326, 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Salasibew M, Kiani A, Faragher B et al. (2008) Awareness and reported violations of the WHO International Code and Pakistan’s national breastfeeding legislation; a descriptive cross-sectional survey. Int Breastfeed J 3, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sokol E, Aguayo V & Clark D (2007) Protecting Breastfeeding in West and Central Africa: 25 Years Implementing the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes. Dakar: UNICEF Regional Office for West and Central Africa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Piwoz EG & Huffman SL (2015) The impact of marketing of breast-milk substitutes on WHO-recommended breastfeeding practices. Food Nutr Bull 36, 373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Taylor A (1998) Violations of the international code of marketing of breast milk substitutes: prevalence in four countries. BMJ 316, 1117–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brady JP (2012) Marketing breast milk substitutes: problems and perils throughout the world. Arch Dis Child 97, 529–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Braun MLG, Giugliani ER, Soares MEM et al. (2003) Evaluation of the impact of the baby-friendly hospital initiative on rates of breastfeeding. Am J Public Health 93, 1277–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ojofeitimi EO, Esimai OA, Owolabi OO et al. (2000) Breast feeding practices in urban and rural health centres: impact of baby friendly hospital initiative in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Nutr Health 14, 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abrahams SW & Labbok MH (2009) Exploring the impact of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative on trends in exclusive breastfeeding. Int Breastfeed J 4, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Venancio SI, Saldiva SRDM, Escuder MML et al. (2012) The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative shows positive effects on breastfeeding indicators in Brazil. J Epidemiol Community Health 66, 914–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pérez-Escamilla R (2007) Evidence based breast-feeding promotion: the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. J Nutr 137, 484–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cattaneo A, Bettinelli ME, Chapin E et al. (2016) Effectiveness of the Baby Friendly Community Initiative in Italy: a non-randomised controlled study. BMJ Open 6, e010232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Grassley J & Eschiti V (2008) Grandmother breastfeeding support: what do mothers need and want? Birth 35, 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. de Oliveira MIC, Camacho LAB & Tedstone AE (2001) Extending breastfeeding duration through primary care: a systematic review of prenatal and postnatal interventions. J Hum Lact 17, 326–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]