Synopsis:

Widespread uptake of a future gonorrhea vaccine could decrease the burden of disease and limit the spread of antibiotic resistance. In an internet-based cross-sectional survey, 74% of parents would get a gonorrhea vaccine for their child, and this was higher among those whose trust in pharmaceutical companies increased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. About 60% of adults 18-45 years would receive a vaccine for themselves. Acceptance was higher among those with higher risk sexual behaviors, such as having multiple sexual partners, and among those who expressed increased trust in pharmaceutical companies and scientists since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: gonorrhea, sexually transmitted diseases, sexual and gender minorities, vaccine hesitancy, trust, vaccine preventable disease

Key points:

-

•

Gonorrhea is the second most common reportable sexually transmitted infection in the US, with increasing cases of antibiotic resistance in young adults.

-

•

The gonorrhea vaccine could be used to decrease substantial morbidity in males and females, but its rollout would be in the shadow of the COVID-19 vaccine, for which there has been uneven acceptance.

-

•

Most parents (74%) would accept a gonorrhea vaccine for their child.

-

•

Parental acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine was associated with their increasing levels of trust in pharmaceutical companies since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

Most adults (∼60%) would receive a gonorrhea vaccine, with similar levels of acceptance regardless of framing of the vaccine as universally recommended vs targeted for high-risk groups.

-

•

Individuals with higher risk sexual behaviors had greater odds of gonorrhea vaccine acceptance, which did not substantially vary by framing of the vaccine recommendation as universal vs targeted.

-

•

Adults with greater trust in pharmaceutical companies or scientists since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to accept a gonorrhea vaccine when one becomes available.

INTRODUCTION

Sexual transmission of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhea) is common. In 2020, 677,769 cases of gonorrhea were reported in the US,1 making it the second most common reportable sexually transmitted infection (STI). Incidence is particularly high among young adults, with over 700 cases per 100,000 males and females 20-24 years.2(p19)

In females, gonococcal cervicitis may lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, which may be antecedent to ectopic pregnancy and infertility even among those who are asymptomatic. Infection during pregnancy may cause miscarriage or premature birth and gonococcal conjunctivitis of the newborn. In males, infection may result in urethritis and epididymo-orchitis.3 If left untreated, gonorrhea in rare cases may cause bacteremia and disseminated infection.4 For these reasons, mitigating its spread is of critical public health importance. Additionally, resistance to some antibiotics, like azithromycin, is also increasing among gonorrhea cases,1 while dual therapy with ceftriaxone and ceftriaxone plus azithromycin has also seen confirmed treatment failures.5

The spread of STIs, such as gonorrhea, is especially high among men who have sex with men (MSM),6, 7, 8 largely due to social and structural drivers of STI inequities such as sexual stigma.9 , 10 About 5.6% of MSM with no clinical symptoms test positive for gonorrhea at clinic visits.11 Expanded use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) since 2012 among MSM has reduced HIV transmission, but has also been accompanied by decreased condom usage12 and could impact efforts to control other STIs, especially the rapidly rising cases of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea cases among MSM.13

Widespread distribution of a future gonorrhea vaccine could reduce the burden of disease and positively impact health outcomes and quality of life for MSM, young adults, and others at risk of disease. Vaccines could also reduce the challenge of antimicrobial resistance, which has become progressively more widespread and complex over the last several decades.14 The currently available Neisseria meningitidis group B (MenB) vaccine is being evaluated in phase II clinical trials for its efficacy and safety in preventing gonorrhea.15 Yet, it is not a given that there will be widespread acceptance of any eventual gonorrhea vaccine.16

Examining success and failures in the rollout of the hepatitis B (HepB) and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines—two vaccines which protect against infections with sexual transmission, but which are characterized by substantially different trajectories of uptake—lends some insight into important factors to consider regarding uptake of a future gonorrhea vaccine. For example, success in the rollout of vaccines in the past has depended on whether a vaccine received a universal or targeted recommendation for use. These grades of recommendation are issued by the US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).17 Specifically, the ACIP distinguishes between “Category A” (vaccines broadly recommended) and “Category B” vaccines (vaccines that clinicians can decide to administer after a clinician-patient interaction).18 The ACIP recommended the first HepB vaccine for use in 1982, but only for those classified as ‘high-risk’ individuals (i.e., MSM, individuals with multiple sexual partners, and people who use injection drugs).19 Uptake was extremely low in these high-risk groups due to difficulties in identifying individuals at heightened risk.20 In successive statements in 1991, 1995, and 1999, the ACIP broadened its strategy to a universal recommendation for the vaccination of all children.20 By 2019, 3-dose coverage of the HepB vaccine was relatively high, at 91.4% in the US.21

The rollout of the HPV vaccine offers a stark contrast to the relative success of the HepB vaccine. Though introduced in 2006, only about half of adolescents in the US had been vaccinated by 2019 (53.7% of female and 48.7% of male adolescents).22 Coverage is low due in part to the focus on the HPV vaccine as an STI vaccine, since parents vary in their beliefs about the necessity of an STI vaccine for their adolescent children,23 and have strong dispreferences for STI vaccines in general.24 The ACIP’s 2006 recommendation that only females be vaccinated,25 which was not broadened to males until 2011,26 could also have exacerbated parental concerns about the vaccine.

Additionally, the roll-out of any future vaccine will now occur against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. Early in the pandemic, vaccine hesitancy in general and rejection of a COVID-19 vaccine specifically were tightly linked.27 Over the course of the pandemic, trust in the United States (US) government decreased.28 Concerns about the COVID-19 vaccination and how the government developed COVID-19 vaccine recommendations could seep into concerns about other vaccines and even further entrench vaccine hesitancy among those already concerned.

Given the recent COVID-19 vaccine roll-out, along with mixed past experiences in introducing STI vaccines, we sought to study acceptance of a potential future gonorrhea vaccine. This study aimed to estimate acceptance of a pediatric gonorrhea vaccine among parents and an adult vaccine among those 18-45 years old. Moreover, we examined how changes in trust towards health authorities since the COVID-19 pandemic, including government, doctors and nurses, pharmaceutical companies, and scientists who develop vaccines, were associated with acceptance of a vaccine for oneself or for one’s child.

METHODS

Study population

Adults resident in the US were eligible for inclusion and were selected into the study through online panels recruited by Dynata, a survey research panel. Panelists were recruited through social media and other advertising methods and received credits to use on gift cards through completing this survey. We used age and gender quotas, and oversampled individuals under 45, in order to obtain more individuals in the age groups higher at risk. We aimed for a sample size of 800 in order to estimate vaccination uptake of 50% (the most statistically conservative number) with sufficient precision – a margin of error of 4% - with an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 80%.

Subsequently we created weights to make the sample similar to the US 2020 Census29 in terms of age, gender, race/ethnicity, region of the country, education. We did this separately for our sample of all adults and for our sample of adults of children under 18 years old.

The survey ran from August 16th through September 2nd, 2022. A total of 806 clicked on the survey. Of these, 751 agreed to the informed consent, 715 spent at least three minutes on the survey (which we judged as a reasonable lower limit for comprehensively reading through the entire survey), and 700 completed the entire survey.

Questionnaire

The survey data and questionnaires are available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21797729.

All individuals received the following information: “Gonorrhea is a bacteria spread through sexual activity that can cause pelvic pain in both men and women. No vaccine is currently available.”

Subsequently, individuals were randomly entered into one of two experimental arms. One arm was presented with a universal recommendation including the following information: “If an advisory panel to the CDC were to review a safe, effective vaccine and recommend everyone to receive the gonorrhea vaccine, would you get it?” The other received a targeted recommendation: “If an advisory panel to the CDC were to review a safe, effective vaccine and recommend that certain groups receive the gonorrhea vaccine, would you get it? The recommended groups would include people with multiple sexual partners, people who have unprotected sex, or men who have sex with men.”

We asked individuals how many sexual partners they have had in the past year, from which we derived three categories: no sexual partners in past year, only one sexual partner in past year, and more than one sexual partner in past year. This last category we use as a representation of sexual concurrency.30

We also asked individuals about their gender and the sex of any prior sexual partner. From this information, we categorized individuals into the following categories: men who have sex with men, men who have sex with only women, women who have sex with men, and women who have sex with only women. These categories were based on stratification of screening guidelines for gonorrhea from the US Preventive Services Task Force.31 Notably, the guidelines recommend screening for women who have sex with men, and indicate more research among MSM is needed.

For individuals identifying themselves as parents of a child 0-17 years , we asked if they would accept a gonorrhea vaccine for their child (we did not divide individuals into universal versus targeted vaccine recommendation groups).

Our exposures included individuals’ self-reported change in trust since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We asked about change in trust in medical or health advice from government, in medical or health advice from doctors and nurses, in pharmaceutical companies, and in scientists who develop vaccines. Response options included more trust, no change, or less trust. Among parents we also asked if their perception of how important they thought pediatric vaccines were had changed, with the options of more important, no change, or less important. This last question was based on questions from the Vaccine Confidence Project.32

Statistical analysis

We conducted separate analyses for adults 18-45 years (i.e., the broad age range for which adults can receive an HPV vaccine in the US33) and parents (of any age) of children 0-17 years.

For parents, we estimated acceptance of a pediatric gonorrhea vaccine overall and stratified across sociodemographic group, and changes in trust in health institutions or authorities since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We measured precision of results with 95% confidence intervals (CI), and differences between categories through a Rao-Scott chi-square test. Logistic regression models were specified to assess the association between changes in trust in health institutions or authorities and the outcome of acceptance of a pediatric gonorrhea vaccine. We present unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) and ORs adjusted for respondent gender, age, education, income, region, race/ethnicity, political affiliation (Republican, Democrat, or Independent), and having heard of gonorrhea previously. These covariates / confounders were specified a priori. Note that we use separate models for each health institution or authority, given the potential for overlap and mediation.

For adults 18-45 years, we estimated acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine for oneself, stratified by the type of recommendation received (universal vs. targeted group recommendation). Our main independent variables were gender and sexuality, number of sexual partners, and changes in trust in institutions or authorities since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to the analyses for parents, we present unadjusted ORs, and adjusted ORs from logistic regression models including respondent gender, age, education, income, region, race/ethnicity, political affiliation, and having heard of gonorrhea previously. Like for the parental models, these covariates were entered into the final adjusted model for adults based on a priori considerations and not significant associations at a bivariate level.

All analyses accounted for sampling weights. The software used was SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethical approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (#HUM00217116). Participants read an informed consent form and had to click on a button with “I agree” before any data collection.

RESULTS

Parents:

Overall, 310 parents completed the survey, of whom 74% (95% CI: 67%, 80%) would obtain a vaccine for their child. Parents were more accepting of a vaccine for a child 9-17 years old (77%, 95% CI: 69%, 84%) than a child 0-8 years old (68%, 95% CI: 60%, 77%). Table 1 shows how acceptance differs across sociodemographic categories. Notably, acceptance was higher among males (84%, 95% CI: 77%, 91%) than females (64%, 95% CI: 54%, 74%) (P=0.0009). Families with the highest monthly household income (≥$8,000) had the greatest acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine (86%, 95% CI: 79%, 92%), compared to those making $3,000 to $7,999 or <$3,000 (both <70% acceptance, P=0.0029). Acceptance was relatively low among non-Hispanic Black parents (54%, 95% CI: 29%, 79%), and relatively high among Hispanic parents (78%, 95% CI: 66%, 90%), although there was no overall significant difference by race/ethnicity (P=0.2531).

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of parents and parental acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine, August 2022.

| Count | Weighted % (95% CI) | Acceptance of gonorrhea vaccine for child 0-17 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Weighted % (95% CI) | P-value | ||||

| Overall | 310 | 236 | 74% (67%, 80%) | |||

| Respondent's gender | Woman | 158 | 50% (43%, 57%) | 110 | 64% (54%, 74%) | 0.0009 |

| Man | 152 | 50% (43%, 57%) | 126 | 84% (77%, 91%) | ||

| Respondent's age | 18-29 years | 79 | 15% (11%, 20%) | 60 | 76% (64%, 88%) | 0.8782 |

| 30-34 years | 82 | 22% (17%, 27%) | 61 | 74% (63%, 85%) | ||

| 35-39 years | 64 | 22% (16%, 27%) | 51 | 77% (65%, 89%) | ||

| ≥40 years | 85 | 41% (33%, 48%) | 64 | 71% (59%, 84%) | ||

| Gender of child(ren) | Any gender | 93 | 30% (23%, 36%) | 80 | 85% (74%, 95%) | 0.0924 |

| Only daughters | 75 | 25% (19%, 31%) | 52 | 66% (53%, 80%) | ||

| Only sons | 142 | 45% (38%, 52%) | 104 | 71% (61%, 81%) | ||

| Age of child(ren) | 0-8 years old | 180 | 50% (43%, 57%) | 124 | 68% (60%, 77%) | a |

| 9-17 years old | 214 | 73% (67%, 79%) | 172 | 77% (69%, 84%) | ||

| Education | ≤High school | 85 | 33% (26%, 40%) | 59 | 73% (62%, 85%) | 0.1511 |

| Associate's degree | 55 | 26% (19%, 32%) | 38 | 64% (49%, 80%) | ||

| Bachelor's degree | 170 | 42% (35%, 49%) | 139 | 80% (72%, 88%) | ||

| Monthly household income | <$3,000 | 79 | 27% (21%, 33%) | 49 | 62% (48%, 75%) | 0.0029 |

| $3,000 to $7,999 | 85 | 29% (23%, 36%) | 64 | 67% (53%, 81%) | ||

| ≥$8,000 | 146 | 44% (37%, 51%) | 123 | 86% (79%, 92%) | ||

| Region | Midwest | 46 | 21% (15%, 27%) | 32 | 74% (59%, 89%) | 0.4313 |

| Northeast | 81 | 22% (16%, 27%) | 68 | 82% (70%, 94%) | ||

| South | 120 | 34% (27%, 41%) | 88 | 67% (55%, 79%) | ||

| West | 63 | 23% (17%, 29%) | 48 | 75% (63%, 88%) | ||

| Race / ethnicity | NH Black | 30 | 9% (5%, 14%) | 19 | 54% (29%, 79%) | 0.2531 |

| NH white | 205 | 58% (51%, 66%) | 161 | 74% (66%, 83%) | ||

| Hispanic | 59 | 25% (18%, 31%) | 45 | 78% (66%, 90%) | ||

| Other | 16 | 7% (3%, 12%) | 11 | 78% (58%, 98%) | ||

| Political affiliation | Democratic | 161 | 50% (43%, 57%) | 125 | 72% (62%, 82%) | 0.2268 |

| Independent | 58 | 17% (12%, 22%) | 36 | 66% (53%, 80%) | ||

| Republican | 91 | 33% (26%, 40%) | 75 | 81% (71%, 91%) | ||

| Having heard of gonorrhea previously | No | 54 | 14% (10%, 19%) | 40 | 81% (71%, 92%) | 0.1980 |

| Yes | 256 | 86% (81%, 90%) | 196 | 72% (65%, 80%) | ||

a P-value not computed because parents could have multiple children across different age categories.

Table 2 shows acceptance and its relation to changes in perceptions of vaccine importance and trust in health institutions or authorities since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, 46% (95% CI: 39%, 53%) of parents mentioned thinking vaccines are more important now than at the start of the pandemic, and these parents had higher acceptance of a pediatric gonorrhea vaccine (82%, 95% CI: 73%, 90%) than those who had no change in their thinking about the importance of vaccines (66%, 95% CI: 55%, 78%). However, this was not significant in a multivariable logistic regression model (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parental acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine, by changes in perceptions and trust since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, August 2022.

| Count | Weighted % (95% CI) | Acceptance of gonorrhea vaccine for child 0-17 years old |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Weighted % (95% CI) | Unadjusted model OR (95% CI) | Adjusted modelsa OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Change in perception of pediatric vaccine importance since COVID-19 | More important | 149 | 46% (39%, 53%) | 124 | 82% (73%, 90%) | 2.33 (1.10, 4.95) | 1.78 (0.79, 3.98) |

| No change | 121 | 42% (35%, 49%) | 86 | 66% (55%, 78%) | ref | ref | |

| Less important | 40 | 12% (8%, 17%) | 26 | 70% (53%, 86%) | 1.23 (0.48, 3.14) | 0.96 (0.36, 2.59) | |

| Change in trust in medical or health advice from government since COVID-19 | More trust | 126 | 36% (30%, 43%) | 105 | 83% (74%, 92%) | 2.38 (1.08, 5.24) | 1.69 (0.71, 4.05) |

| No change | 132 | 47% (40%, 54%) | 96 | 68% (58%, 78%) | ref | ref | |

| Less trust | 52 | 17% (11%, 22%) | 35 | 70% (53%, 86%) | 1.13 (0.45, 2.84) | 1.01 (0.40, 2.51) | |

| Change in trust in medical or health advice from doctors and nurses since COVID-19 | More trust | 158 | 47% (40%, 54%) | 129 | 82% (75%, 90%) | 2.50 (1.19, 5.24) | 1.82 (0.82, 4.05) |

| No change | 113 | 41% (34%, 48%) | 82 | 66% (54%, 77%) | ref | ref | |

| Less trust | 39 | 12% (7%, 16%) | 25 | 66% (48%, 85%) | 0.99 (0.37, 2.64) | 0.73 (0.26, 2.04) | |

| Change in trust in pharmaceutical companies since COVID-19 | More trust | 140 | 43% (36%, 50%) | 120 | 86% (79%, 94%) | 2.93 (1.29, 6.65) | 2.36 (0.98, 5.66) |

| No change | 120 | 40% (33%, 47%) | 89 | 69% (58%, 80%) | ref | ref | |

| Less trust | 50 | 16% (11%, 22%) | 27 | 52% (34%, 70%) | 0.52 (0.21, 1.28) | 0.41 (0.17, 0.99) | |

| Change in trust in scientists who develop vaccines since COVID-19 | More trust | 143 | 44% (37%, 51%) | 118 | 84% (76%, 92%) | 2.87 (1.36, 6.08) | 2.34 (1.09, 5.02) |

| No change | 131 | 47% (40%, 54%) | 95 | 65% (54%, 76%) | ref | ref | |

| Less trust | 36 | 9% (5%, 13%) | 23 | 71% (54%, 87%) | 1.31 (0.51, 3.36) | 1.14 (0.40, 3.21) | |

Notes:

a Separate logistic regression models for each measure of perception or trust; adjusted for respondent gender, age, education, income, region, race/ethnicity, political affiliation, and having heard of gonorrhea previously

Similarly, among those who reported more trust in health advice in the government, 83% (95% CI: 74%, 92%) would accept a vaccine, versus 68% with no change in trust (95% CI: 58%, 78%); and among those who reported more trust in advice from doctors or nurses, 82% (95% CI: 75%, 90%) would accept a vaccine, versus 66% with no change in trust (95% CI: 54%, 77%). But these variables were also not significant in a multivariable logistic regression model. Stated change in trust in scientists who develop vaccines was significantly related to acceptance of a pediatric gonorrhea vaccine in a multivariable model (more trust vs no change, OR: 2.34, 95% CI: 1.09, 5.02; Table 2).

Adults 18-45 years

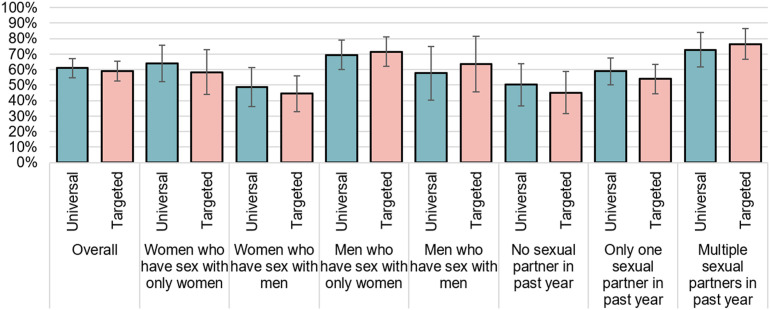

Among adults 18-45 years, 304 were randomized to universal recommendation for a gonorrhea vaccine group, and 269 the targeted recommendation group. Acceptance of a vaccine was similar across both groups (61%, 95% CI: 55%, 67%; vs 59%, 95% CI: 53%, 66%; Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine for oneself among adults 18-45 years old, stratified by gender / sexuality, and number of sexual partners, August 2022.

Acceptance based on stated changes in trust in various health institutions or authorities is found in Table 3 . In the group with the universal recommendation, acceptance was higher among those with more trust in the government since COVID-19 (74% vs 53% among those with less trust), in doctors and nurses (71% vs 55%), in pharmaceutical companies (75% vs 45%), and in scientists (76% vs 51%). In logistic regression models, we collapsed together both experimental arms given the absence of a large effect (Table 4 ). We found those with more trust in pharmaceutical companies and those with more trust in scientists had significantly greater odds of acceptance of a vaccine (OR: 2.03 95% CI: 1.03, 3.98; and OR: 2.35, 95% CI: 1.20, 4.59, respectively).

Table 3.

Acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine for oneself among adults 18-45 years old, stratified by type of vaccine recommendation, August 2022.

| Acceptance under universala recommendation |

Acceptance under targetedb recommendation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Weighted % (95% CI) | Count | Weighted % (95% CI) | |||

| Overall | 182/304 | 61% (55%, 67%) | 154/269 | 59% (53%, 66%) | ||

| Gender | Woman | 54% | 90/159 | 56% (47%, 65%) | 70/141 | 50% (41%, 59%) |

| Man | 45% | 90/143 | 66% (58%, 75%) | 83/127 | 70% (61%, 78%) | |

| Other | <0.5% | 2/2 | 1/1 | |||

| Age | 18-29 years | 37% | 81/129 | 63% (53%, 72%) | 63/109 | 61% (50%, 71%) |

| 30-34 years | 27% | 48/78 | 65% (54%, 76%) | 31/56 | 57% (43%, 70%) | |

| 35-39 years | 16% | 21/40 | 54% (37%, 71%) | 27/51 | 57% (43%, 71%) | |

| ≥40 years | 20% | 32/57 | 57% (41%, 73%) | 33/53 | 61% (48%, 75%) | |

| Education | ≤High school | 35% | 58/105 | 61% (50%, 71%) | 40/77 | 59% (46%, 71%) |

| Associate's degree | 21% | 49/73 | 67% (55%, 78%) | 32/66 | 51% (38%, 63%) | |

| Bachelor's degree | 44% | 75/126 | 58% (48%, 68%) | 82/126 | 63% (54%, 72%) | |

| Monthly household income | <$3,000 | 36% | 61/114 | 55% (45%, 65%) | 45/93 | 54% (42%, 65%) |

| $3,000 to $7,999 | 31% | 63/98 | 63% (51%, 75%) | 39/82 | 46% (34%, 58%) | |

| ≥$8,000 | 33% | 58/92 | 66% (56%, 76%) | 70/94 | 75% (66%, 85%) | |

| Region | Midwest | 19% | 24/46 | 57% (39%, 75%) | 25/46 | 58% (42%, 74%) |

| Northeast | 24% | 43/71 | 65% (53%, 76%) | 47/68 | 73% (62%, 84%) | |

| South | 37% | 78/127 | 60% (50%, 69%) | 53/105 | 52% (41%, 62%) | |

| West | 20% | 37/60 | 62% (49%, 76%) | 29/50 | 56% (41%, 71%) | |

| Race / ethnicity | NH Black | 20% | 29/47 | 62% (48%, 77%) | 18/35 | 49% (32%, 67%) |

| NH white | 47% | 101/177 | 55% (46%, 63%) | 95/167 | 58% (51%, 66%) | |

| Hispanic | 26% | 37/59 | 68% (55%, 80%) | 34/50 | 71% (58%, 84%) | |

| Other | 8% | 15/21 | 70% (50%, 91%) | 7/17 | 45% (21%, 70%) | |

| Political affiliation | Democratic | 49% | 102/148 | 70% (62%, 77%) | 89/128 | 68% (59%, 77%) |

| Independent | 25% | 38/73 | 52% (39%, 65%) | 34/82 | 45% (32%, 57%) | |

| Republican | 26% | 42/83 | 52% (38%, 65%) | 31/59 | 59% (45%, 73%) | |

| Having heard of gonorrhea previously | No | 22% | 36/78 | 48% (36%, 61%) | 15/47 | 30% (16%, 44%) |

| Yes | 78% | 146/226 | 65% (58%, 72%) | 139/222 | 65% (58%, 72%) | |

| Change in trust in medical or health advice from government since COVID-19 | More trust | 38% | 48/66 | 74% (63%, 85%) | 43/58 | 77% (66%, 88%) |

| No change | 44% | 38/64 | 62% (49%, 74%) | 43/64 | 70% (58%, 82%) | |

| Less trust | 18% | 12/26 | 53% (32%, 74%) | 13/23 | 51% (29%, 74%) | |

| Change in trust in medical or health advice from doctors and nurses since COVID-19 | More trust | 52% | 56/81 | 71% (60%, 81%) | 52/74 | 72% (61%, 83%) |

| No change | 35% | 32/54 | 61% (47%, 75%) | 35/54 | 66% (53%, 79%) | |

| Less trust | 13% | 10/21 | 55% (32%, 77%) | 12/17 | 69% (45%, 92%) | |

| Change in trust in pharmaceutical companies since COVID-19 | More trust | 44% | 53/73 | 75% (65%, 85%) | 47/64 | 78% (67%, 88%) |

| No change | 39% | 34/57 | 62% (48%, 76%) | 35/59 | 59% (45%, 72%) | |

| Less trust | 16% | 11/26 | 45% (25%, 66%) | 17/22 | 76% (57%, 95%) | |

| Change in trust in scientists who develop vaccines since COVID-19 | More trust | 46% | 57/78 | 76% (66%, 86%) | 46/61 | 78% (67%, 89%) |

| No change | 41% | 31/56 | 56% (42%, 70%) | 44/70 | 64% (51%, 76%) | |

| Less trust | 13% | 10/22 | 51% (27%, 74%) | 9/14 | 59% (31%, 87%) | |

Notes:

a If an advisory panel to the CDC were to review a safe, effective vaccine and recommend everyone to receive the gonorrhea vaccine, would you get it?

b If an advisory panel to the CDC were to review a safe, effective vaccine and recommend that certain groups receive the gonorrhea vaccine, would you get it? The recommended groups would include people with multiple sexual partners, people who have unprotected sex, or men who have sex with men.

Table 4.

Acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine for oneself, by sexual behaviors and changes in trust since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, August 2022

| Acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine for oneselfa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model OR (95% CI) | Adjusted modelsb OR (95% CI) | ||

| Gender and sexuality | Women who have sex with only women | 2.16 (1.04, 4.46) | 2.37 (1.06, 5.27) |

| Women who have sex with men | ref | ref | |

| Men who have sex with only women | 2.66 (1.38, 5.14) | 1.83 (0.82, 4.08) | |

| Men who have sex with men | 1.37 (0.58, 3.25) | 0.63 (0.19, 2.05) | |

| Sexual behaviors | No sexual partner in past year | ref | ref |

| Only one sexual partner in past year | 1.60 (0.64, 4.00) | 1.54 (0.48, 4.94) | |

| Multiple sexual partners in past year | 5.10 (1.82, 14.28) | 4.82 (1.37, 16.98) | |

| Change in trust in medical or health advice from government since COVID-19 | More trust | 1.62 (0.91, 2.88) | 1.80 (0.91, 3.60) |

| No change | ref | ref | |

| Less trust | 0.57 (0.27, 1.19) | 0.74 (0.35, 1.59) | |

| Change in trust in medical or health advice from doctors and nurses since COVID-19 | More trust | 1.43 (0.81, 2.53) | 1.13 (0.57, 2.25) |

| No change | ref | ref | |

| Less trust | 0.89 (0.40, 1.97) | 0.99 (0.40, 2.43) | |

| Change in trust in pharmaceutical companies since COVID-19 | More trust | 2.12 (1.19, 3.77) | 2.03 (1.03, 3.98) |

| No change | ref | ref | |

| Less trust | 0.95 (0.45, 1.99) | 0.94 (0.43, 2.03) | |

| Change in trust in scientists who develop vaccines since COVID-19 | More trust | 2.18 (1.24, 3.83) | 2.35 (1.20, 4.59) |

| No change | ref | ref | |

| Less trust | 0.75 (0.33, 1.72) | 0.92 (0.40, 2.13) | |

Notes:

a N=Models exclude individuals non-binary or an “other” gender (n=3).

b Separate logistic regression models for each measure of sexual behavior or trust; adjusted for respondent gender and sexuality, age, education, income, region, race/ethnicity, political affiliation, and having heard of gonorrhea previously.

Figure 1 shows relatively low acceptance of the vaccine among those with lower risk sexual behaviors: among those with no sexual partner in past year, acceptance was 50% in the universal group and 45% in the targeted group; among those with only one sexual partner, acceptance was 59% and 54%, respectively, and among those with multiple sexual partners in past year, acceptance was 73% and 77%, respectively. In a multivariable model (Table 4), those with multiple sexual partners in the past year had 4.82 times higher odds of gonorrhea vaccine acceptance compared to those with no sexual partners in the past year (95% CI: 1.37, 16.98). By gender and sexuality, acceptance was highest among men who have sex with only women (69% and 72%, respectively), and relatively low among women who have sex with men (49% and 45%, respectively). In a multivariable model (Table 4), vaccine acceptance was higher among women who have sex with only women compared to other women (OR: 2.37, 95% CI: 1.06, 5.27), and there were no significant differences across other gender / sexuality categories.

DISCUSSION

The potential future availability of a gonorrhea vaccine could prevent disease in young adults, particularly among MSM and individuals with high-risk sexual behaviors that increase chances for infection. It could also help limit the spread of gonorrheal antibiotic resistance which has become both more widespread geographically while also resulting in resistance to a progressively greater number of anti-microbial agents. This cross-sectional survey from August 2022, did not find a significant effect on vaccine acceptance based on whether the hypothetical gonorrhea vaccine came with a universal vs targeted recommendation. However, we did find significant variation in how accepted the vaccine was based on stated changes in trust in scientific institutions, particularly pharmaceutical companies and the scientists who develop vaccines.

Parental acceptance of a pediatric or adolescent gonorrhea vaccine

Since the turn of the century, a number of new early childhood vaccine have been introduced.34 These include the rotavirus vaccine for infants in 2006,35 the hepatitis A vaccine for children 1 year old in 2006,36 the influenza vaccine for everyone >6 months in 2010,37 and the COVID-19 vaccine for children as young as 6 months in 202238. There have also been several newly recommended adolescent vaccines over this same time period comprising the meningitis vaccination for those 11-12 in 2005,39 the HPV vaccine for females 11-12 years old since 2006 and for males 11-12 years old since 201133, and the COVID-19 vaccine for those 12-15 years old in 2021.40 During the last decade, uptake of these vaccines has remained stubbornly lower (for example, rotavirus at 77% or influenza at 64%) than vaccines introduced much early in the US such as polio, diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis, and measles-mumps-rubella vaccines which all have achieved contemporary vaccination coverage of greater than 90%.41 , 42 There are a variety of explanations for these changes in uptake of pediatric vaccines – including known experiences with the disease.43 As formulated through models of behavior change like the Health Belief Model,44 lower acceptance could be due to lower perceived risk and lower perceived benefit, particularly if individuals assume that they or their children are not at risk of the sexually transmitted infection.

The response to pediatric COVID-19 vaccination could be an additional harbinger of potential difficulties in rolling out new vaccines. As of February 2023, only about 12% of children 6 months-4 years, 39% of those 5-11 years, and 68% of those 12-17 years old had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, despite intense and sustained promotions on local, state, and national levels.45 Yet, the COVID-19 pandemic has arguably been the most prominent manifestation of vaccine development in most individuals’ lifetimes. Unfortunately, during the COVID-19 pandemic, administration of routine childhood vaccines, including doses provided through the Vaccines-for-Children program, decreased.46 , 47 Although this is at least partially resulted from difficulty in obtaining certain health care visits, or reticence in doing so during a pandemic, it also denotes the potential for increased vaccine hesitancy. For example, compared to adults who have received a COVID-19 vaccine, unvaccinated adults believe that pediatric measles-mumps-rubella vaccination is riskier.48 And in a series of surveys conducted over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, Opel et al. found fluctuations in negative vs positive attitudes towards childhood vaccines.49 Another study found an increase in hesitancy,50 although changes in the degree and direction of vaccine hesitancy over the course of the pandemic may vary by location and the exact time under study.

It could be that for some individuals, the COVID-19 pandemic has strengthened pro-vaccination views, whereas for others, anti-vaccine sentiment has been reinforced or solidified. Results from this study show that a plurality of individuals stated that they believed vaccines to be more important, or that they had more trust in recommendations from healthcare providers. This study also shows a likely relationship between these changes in perception and stated trust, and acceptance of future vaccines. Given substantial regional differences in the COVID-19 response51 and in vaccine uptake45, this finding intimates the possibility of substantial clustering in the uptake of future vaccines, like for gonorrhea, which could lead to increased outbreak potential in local areas.52

Adult acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine

Our study randomized individuals to one of two groups receiving universal versus targeted vaccine recommendations. We found no significant effect, although there was possible evidence that targeted recommendations dampened acceptance among those with less risky sexual behaviors and enhanced levels of acceptance among MSMs. Our sample also may not be generalizable if individuals with a certain set of sexual behaviors were more or less likely to complete the survey. Moreover, our experiment was limited. In reality, individuals’ exposures to vaccine recommendations are complex and multifaceted, filtered, for example, through a range of public service announcements,53, 54, 55 through communications with doctors, nurses, and other health professionals,56 , 57 and through individual research and influences from one’s social network58 , 59.

We found overlap between adult gonorrhea vaccine acceptance and stated changes in trust in the government, doctors and nurses, pharmaceutical companies, and scientists. Similar to the findings in parents, among adults, few (<20%) indicated having less trust, but these were the individuals much less likely to be receptive to a gonorrhea vaccine. Even before the pandemic, Sarathchandra et al. found that vaccine hesitancy was highly correlated with trust in biologists and political affiliation.60 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbating this issue potentially speaks to additional challenges in rolling out vaccines in the future.

The recent mpox (formerly, monkeypox) outbreak is a case study in how to roll-out a vaccine under a targeted recommendation for vaccination against an infection spread during sexual activities.61 In particular, increasing uptake of the mpox vaccine among MSMs has been a major public health goal. One study in summer 2022 reported that 82% of MSM would accept an mpox vaccine.62 However, actual uptake of the vaccine was more constrained among MSM (around 19% by the end of August 202263). Even beyond supply issues, the rollout of the mpox vaccine shows that more research is needed in developing a more comprehensive understanding of best practices to encourage uptake of an STI vaccine.

In a multivariate model examining acceptance of a gonorrhea vaccine for oneself based on sexual behaviors, we found that women who have sex with only women had higher odds of accepting a vaccine relative to women who have sex with men. This finding runs counter to how providers often view women who have sex with only women as having low perceived STI risk, and suggests future research is needed to understand this groups’ sexual risk practices.64 Moreover, that MSM, a group disproportionately affected by gonorrhea, did not have statistically significantly higher odds of accepting a gonorrhea vaccine, is of concern and suggests that future research is needed to develop targeted MSM-specific gonorrhea vaccine uptake interventions.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study. As a cross-sectional study with a hypothetical vaccine recommendation scenario, we cannot clearly distinguish temporality of the exposure or assess causality; we are interested in changes in levels of trust, but measured these only at one point, not across multiple time points. In this convenience sample, there could also be bias in who responded to the survey. We also had a limited sample size, particularly among MSM, and were not able to break down high risk sexual behaviors by sexuality. Our gender question did not include options for nonbinary and/or other transgender identities, meaning all our presented results assume cisgender identities. As transgender people are also disproportionately affected by STIs, future studies may ask more nuanced gender questions.

Conclusions

Despite strong population dispreferences for STI vaccines,24 the introduction of a future vaccine for gonorrhea has a significant potential for reducing disease in adolescents and young adults and preventing antibiotic resistance. The COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to participant perceptions about the roll-out of a new STI vaccine. This study found majorities of parents in the US would accept a gonorrhea vaccine for their child, and most young adults would have themselves vaccinated. Yet a minority have become less trusting of vaccine recommendations from the government, doctors and nurses, pharmaceutical companies, and scientists. The population benefits of a gonorrhea vaccine may be limited if there is substantial non-vaccination clustering or otherwise inequitably low uptake of the vaccine.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01AI137123. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Uncited reference

2..

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC. National Overview of STDs, 2020. Published April 11, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020/overview.htm

- 2.CDC. Gonorrhea - Rates of Reported Cases by Age Group and Sex, United States, 2018. Published April 14, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/figures/19.htm

- 3.Tsevat D.G., Wiesenfeld H.C., Parks C., Peipert J.F. Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Infertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(1):1. doi: 10.1016/J.AJOG.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unemo M., Seifert H.S., Hook E.W., Hawkes S., Dillon J.A.R. Gonorrhoea. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5(1):80. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang F., Yan J. Antibiotic Resistance and Treatment Options for Multidrug-Resistant Gonorrhea. Infect Microbes Dis. 2020;2(2):67–76. doi: 10.1097/IM9.0000000000000024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safren S.A., Devaleenal B., Biello K.B., et al. Geographic and behavioral differences associated with sexually transmitted infection prevalence among Indian men who have sex with men in Chennai and Mumbai. Int J STD AIDS. 2021;32(2):144–151. doi: 10.1177/0956462420943016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siahaan I., Sudaryo M.K. Association between Syphilis and HIV in the Men Sex with Men (MSM) Population in Indonesia in 2015: Secondary Data Analysis of Integrated Behavior and Biological Survey (IBBS) 2015. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2020;11(3):2298–2303. doi: 10.37506/IJPHRD.V11I3.2730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu G.F., Jiang N., Hu H.Y., et al. The epidemic of HIV, syphilis, chlamydia and gonorrhea and the correlates of sexual transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Jiangsu, China, 2009. PloS One. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0118863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez-Hart C., Nowak R.G., Musci R., et al. Pathways from sexual stigma to incident HIV and sexually transmitted infections among Nigerian MSM. AIDS. 2017;31(17):2415–2420. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earnshaw V.A., Reed N.M., Watson R.J., Maksut J.L., Allen A.M., Eaton L.A. Intersectional internalized stigma among Black gay and bisexual men: A longitudinal analysis spanning HIV/sexually transmitted infection diagnosis. J Health Psychol. 2021;26(3):465–476. doi: 10.1177/1359105318820101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mimiaga MJ, Helms DJ, Reisner SL, et al. Gonococcal, chlamydia, and syphilis infection positivity among MSM attending a large primary care clinic, Boston, 2003 to 2004. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(8):507-511. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a2ad98 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Montaño M.A., Dombrowski J.C., Dasgupta S., et al. Changes in Sexual Behavior and STI Diagnoses Among MSM Initiating PrEP in a Clinic Setting. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(2):548–555. doi: 10.1007/S10461-018-2252-9/TABLES/3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott H.M., Klausner J.D. Sexually transmitted infections and pre-exposure prophylaxis: challenges and opportunities among men who have sex with men in the US. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13(1) doi: 10.1186/S12981-016-0089-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent L.R., Jerse A.E. Biological feasibility and importance of a gonorrhea vaccine for global public health. Vaccine. 2019;37(50):7419–7426. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haese E.C., Thai V.C., Kahler C.M. Vaccine Candidates for the Control and Prevention of the Sexually Transmitted Disease Gonorrhea. Vaccines. 2021;9(7):804. doi: 10.3390/VACCINES9070804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey S.M., Gibbs S.E., Sikora A.E. A Critical Need for Research on Gonorrhea Vaccine Acceptability. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48(8):E116–E118. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickering L.K., Orenstein W.A., Sun W., Baker C.J. FDA licensure of and ACIP recommendations for vaccines. Vaccine. 2017;35(37):5027–5036. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed F, Temte JL, Campos-Outcalt D, Schünemann HJ. Methods for developing evidence-based recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for the ACIP Evidence Based Recommendations Work Group (EBRWG) 1. Vaccine. 2011;29:9171-9176. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Recommendation of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP). Inactivated hepatitis B virus vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31(24):317-322, 327-328. [PubMed]

- 20.National Immunization Program; Div of Viral Hepatitis, National Center for Infectious Diseases CDC. Achievements in Public Health: Hepatitis B Vaccination --- United States, 1982--2002. MMWR Wkly. 2002;51(25):549-552,563.

- 21.Hill H.A., Yankey D., Elam-Evans L.D., Singleton J.A., Pingali S.C., Santibanez T.A. Vaccination Coverage by Age 24 Months Among Children Born in 2016 and 2017 — National Immunization Survey-Child, United States, 2017–2019. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(42):1505. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM6942A1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elam-Evans L.D., Yankey D., Singleton J.A., et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2019. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(33):1109. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM6933A1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markowitz L.E., Gee J., Chesson H., Stokley S. Ten Years of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in the United States. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/J.ACAP.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner A.L., Lu Y., Janusz C.B., et al. Preferences for Sexually Transmitted Infection and Cancer Vaccines in the United States and in China. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2023;26(2):261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markowitz L.E., Dunne E.F., Saraiya M., Lawson H.W., Chesson H., Unger E.R. Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1–24. doi: 10.1037/e601292007-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroger A.T., Sumaya C.V., Pickering L.K., Atkinson W.L. General recommendations on immunization; recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunizations Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(2):3–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shih S.F., Wagner A.L., Masters N.B., Prosser L.A., Lu Y., Zikmund-Fisher B.J. Vaccine Hesitancy and Rejection of a Vaccine for the Novel Coronavirus in the United States. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.558270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suhay E., Soni A., Persico C., Marcotte D.E. Americans’ Trust in Government and Health Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic. RSF Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci. 2022;8(8):221–244. doi: 10.7758/RSF.2022.8.8.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Census Bureau. America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2020. Census.gov. Published 2020. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/families/cps-2020.html

- 30.Adimora A.A., Schoenbach V.J., Doherty I.A. Concurrent Sexual Partnerships Among Men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2230–2237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;326(10):949-956. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.14081 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.de Figueiredo A., Simas C., Karafillakis E., Paterson P., Larson H.J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. The Lancet. 2020;396(10255):898–908. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meites E. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Adults: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wodi A.P., Murthy N., Bernstein H., McNally V., Cineas S., Ault K. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:234–237. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7107a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parashar U., Alexander J., Glass R. Prevention of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis Among Infants and Children: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR12):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-7):1-23. [PubMed]

- 37.Fiore A., Uyeki T., Broder K., et al. Prevention and Control of Influenza with Vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(RR08):1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleming-Dutra K.E., Wallace M., Moulia D.L., et al. Interim Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccines in Children Aged 6 Months–5 Years — United States, June 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(26):859–868. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7126e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bilukha O., Rosenstein N. Prevention and Control of Meningococcal Disease: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(RR07):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wallace M., Woodworth K.R., Gargano J.W., et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Interim Recommendation for Use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine in Adolescents Aged 12–15 Years — United States, May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(20):749–752. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7020e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill H.A., Chen M., Elam-Evans L.D., Yankey D., Singleton J.A. Vaccination Coverage by Age 24 Months Among Children Born During 2018–2019 — National Immunization Survey–Child, United States, 2019–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(2):33–38. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7202a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagner A.L., Eccleston A.M., Potter R.C., Swanson R.G., Boulton M.L. Vaccination timeliness at age 24 months in Michigan children born 2006-2010. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(1):96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner AL, Pinckney LC, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Vaccine Decision-making and Vaccine Hesitancy. In: Boulton ML, Wallace RB, eds. Maxcy-Rosenau-Last Public Health and Preventive Medicin2. McGraw-Hill Publishing; 2020. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?sectionid=257463543&bookid=3078

- 44.Janz N.K., Becker M.H. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19 Vaccination Trends. Published 2023. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-vaccination-trends/

- 46.Olusanya O.A., Bednarczyk R.A., Davis R.L., Shaban-Nejad A. Addressing Parental Vaccine Hesitancy and Other Barriers to Childhood/Adolescent Vaccination Uptake During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.663074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker B., Anderson A., Stoecker C., Shao Y., LaVeist T.A., Callison K. COVID-19 and Routine Childhood and Adolescent Immunizations: Evidence from Louisiana Medicaid. Vaccine. 2022;40(6):837–840. doi: 10.1016/J.VACCINE.2021.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopes L, Schumacher S, Presiado M, 2022. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2022. KFF. Published December 16, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2022/

- 49.Opel D.J., Furniss A., Zhou C., et al. Parent Attitudes Towards Childhood Vaccines After the Onset of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(8):1407–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He K., Mack W.J., Neely M., Lewis L., Anand V. Parental Perspectives on Immunizations: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Childhood Vaccine Hesitancy. J Community Health. 2022;47(1):39–52. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-01017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(4):529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Masters N.B., Eisenberg M.C., Delamater P.L., Kay M., Boulton M.L., Zelner J. Fine-scale spatial clustering of measles nonvaccination that increases outbreak potential is obscured by aggregated reporting data. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(45):28506–28514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2011529117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kepka D., Coronado G.D., Rodriguez H.P., Thompson B. Evaluation of a Radionovela to Promote HPV Vaccine Awareness and Knowledge Among Hispanic Parents. J Community Health. 2011;36(6):957–965. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9395-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reinhardt A., Rossmann C., Engel E. Radio public service announcements to promote vaccinations for older adults: Effects of framing and distraction. Vaccine. 2022;40(33):4864–4871. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nan X., Futerfas M., Ma Z. Role of Narrative Perspective and Modality in the Persuasiveness of Public Service Advertisements Promoting HPV Vaccination. Health Commun. 2017;32(3):320–328. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1138379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Milkman K.L., Patel M.S., Gandhi L., et al. A megastudy of text-based nudges encouraging patients to get vaccinated at an upcoming doctor’s appointment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(20) doi: 10.1073/PNAS.2101165118/-/DCSUPPLEMENTAL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Attwell K., Smith D.T. Hearts, minds, nudges and shoves: (How) can we mobilise communities for vaccination in a marketised society? Vaccine. 2017;36(44):6506–6508. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Betsch C., Brewer N.T., Brocard P., et al. Opportunities and challenges of Web 2.0 for vaccination decisions. Vaccine. 2012;30(25):3727–3733. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ni L., wang Chen Y., de Brujin O. Towards understanding socially influenced vaccination decision making: An integrated model of multiple criteria belief modelling and social network analysis. Eur J Oper Res. 2021;293(1):276–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2020.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sarathchandra D., Navin M.C., Largent M.A., McCright A.M. A survey instrument for measuring vaccine acceptance. Prev Med. 2018;109:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poland G.A., Kennedy R.B., Tosh P.K. Prevention of monkeypox with vaccines: a rapid review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(12):e349–e358. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reyes-Urueña J., D’Ambrosio A., Croci R., et al. High monkeypox vaccine acceptance among male users of smartphone-based online gay-dating apps in Europe, 30 July to 12 August 2022. Eurosurveillance. 2022;27(42) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.42.2200757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Delaney K.P. Strategies Adopted by Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men to Prevent Monkeypox virus Transmission — United States, August 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7135e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McNair RP. Lesbian, Bisexual, Queer and Transgender Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health. In: Routledge International Handbook of Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health. Routledge; 2019.