Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To identify the perceived organizational resources required by healthcare workers to deliver geriatric primary care in a geriatric patient aligned care team (GeriPACT).

DESIGN:

Cross-sectional observational study using deductive analyses of qualitative interviews conducted with GeriPACT team members.

SETTING:

GeriPACTs practicing at eight geographically dispersed Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare systems.

PARTICIPANTS:

GeriPACT clinicians, nurses, clerical associates, clinical pharmacists, and social workers (n = 67).

MEASUREMENTS:

Semistructured qualitative interviews conducted in person, transcribed, and then analyzed using the PACT Resources Framework.

RESULTS:

Using the PACT Resources Framework, we identified facility-, clinic-, and team-level resources critical for GeriPACT implementation. Resources within each level reflect how the needs of older adults with complex comorbidity intersect with general population primary care medical home practice. GeriPACT implementation is facilitated by attention to patient characteristics such as cognitive impairment, ambulatory limitations, or social support services in staffing and resourcing teams.

CONCLUSION:

Models of geriatric primary care such as GeriPACT must be implemented with an eye toward the most effective use of our most limited resource-trained geriatricians. In contrast to much of the literature on medical home teams serving a general adult population, interviews with GeriPACT members emphasize how patient needs inform all aspects of practice design including universal accessibility, near real-time response to patient needs, and ongoing interdisciplinary care coordination. Examination of GeriPACT implementation resources through the lens of traditional primary care teams illustrates the importance of tailoring primary care design to the needs of older adults with complex comorbidity.

Keywords: patient-centered medical home, veterans, primary care, qualitative research

In 2010 the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) began the implementation of a patient-centered medical home model in all primary care settings. Known as patient aligned care teams, or PACTs, this systemic reorganization of primary care staff into teams was adopted to enhance care continuity, access, and the quality of chronic disease management.1 Although PACTs deliver primary care to veterans across the life course, the VA recognized the need for specialized PACTs to serve those patients with extensive care coordination needs or complex comorbidities.

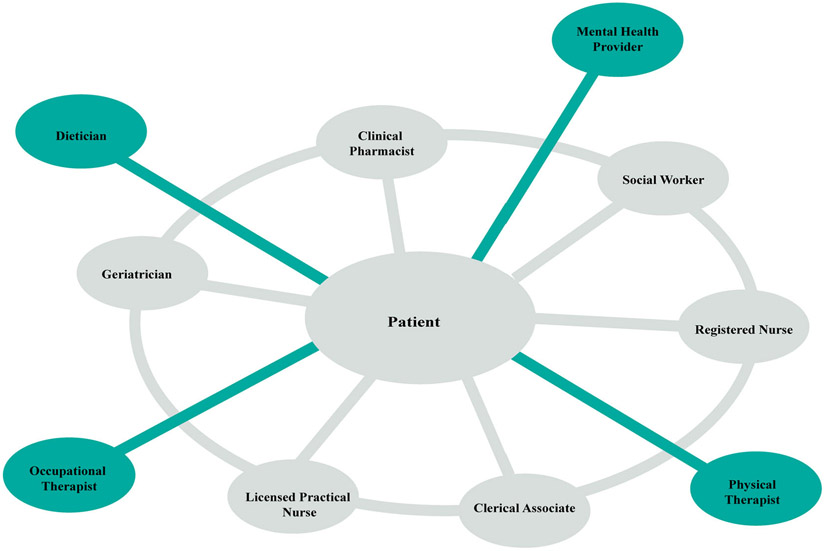

The geriatric patient aligned care team (GeriPACT) is “a collaborative partnership with an interdisciplinary team of suitably prepared healthcare professionals. It consists of the GeriPACT provider, a registered nurse, a social worker, a clinical pharmacist, a clinical associate (generally a licensed vocational nurse, licensed practical nurse, or health technician), and clerical staff. Following PACT terminology, this core team is referred to as the “GeriPACT teamlet; other clinicians (eg, mental health professional, dietician, occupational and physical therapist, audiologist, etc) are also involved in clinical care as patient needs or local preferences dictate.”2 In addition to a larger core team than PACTs, which do not include a social worker or clinical pharmacist as core members, GeriPACTs are supported with longer standard appointment times (eg, 45 or 60 instead of 30 minutes) and smaller panel sizes. Figure 1 shows the GeriPACT structure.

Figure 1.

Illustration of GeriPACT model. A GeriPACT is composed of six core members who share interprofessional knowledge, psychological safety, and a shared sense of urgency to meet the needs of older adults with complex comorbidity in near real time. GeriPACT core members (illustrated in gray) augment their expertise with that of extended team (illustrated in green) specialty provider members.

GeriPACTs belong to the VA’s extensive suite of innovative geriatrics-focused programs that serve patients with significant clinical complexity and care coordination needs. At the same time, GeriPACTs are primary care teams that may report implementation needs similar to PACTs. In prior work, our team developed the PACT Resources Framework (PRF) to characterize the capacities necessary for medical home implementation.3 The PRF is composed of 11 resources distributed across three levels (facility, clinic, and team) (Table 1).

Table 1.

PACT Resources Framework Mapped to GeriPACT Model

| Level | PACT | GeriPACT |

|---|---|---|

| System | Clear and unified message for PCMH goals Site-sensitive staff distribution and position descriptions |

Leadership support in meeting geriatrics-aligned goals Leadership support of staffing model |

| Clinic | Protected time for team administration Ongoing training Team-owned schedule Timely, actionable data for QI work Patient- and team-centered clinic space |

Protected time for team development and performance Training and professional development Appointment scheduling reflects team care processes Clinical and process data used to enhance performance Built environment and infrastructure reflects patient needs and supports team processes |

| Team | Demarcated group boundaries and collective team identity Shared goals and sense of purpose Mature communication characterized by psychological safety Ongoing and intentional role negotiation and development |

Identification as a cohesive interprofessional team Shared purpose Mature communication and psychological safety Clear and distinct roles |

Abbreviations: GeriPACT, Geriatric patient-aligned care team; PACT, patient-aligned care team; PCMH, patient-centered medical home; QI, quality improvement.

Although the work of others across sectors has confirmed the importance of these resources to medical home implementation (eg, mature communication,4,5 teamwork,5-8 leadership support,9-11 staffing,6 role clarity,12 or availability of clinical data to enhance performance13,14) and similar concepts are reflected in the literature on geriatric models of care (eg, leadership support,15,16 training,15,17,18 geriatric-friendly appointment scheduling,16,17,19 clinically appropriate performance metrics,16 geriatric-friendly built environment,17 interprofessional knowledge,16,17,20-24 shared purpose,20 mature communication,17 or role clarity16), to date few studies22 have examined the implementation needs at the intersection of geriatrics-informed delivery models with general population medical homes.1,16

Given the higher investment in human capital, the growing demand for geriatric primary care, and the limited number of geriatrics-trained providers, we must use our clinical resources effectively.15,25,26 The objective of this study was to identify which resources are necessary to support implementation of GeriPACTs by using the PRF as an analytic tool to identify and synthesize GeriPACT needs from the perspective of team members.

METHODS

To understand how serving a population of older adults with complex comorbidity intersects with the resources known to support general population PACT implementation, we analyzed qualitative interviews conducted with core members of eight GeriPACTs (n = 67). Interviews analyzed in this study were collected as part of a multi-method study of GeriPACT implementation. The parent study first administered a survey to all GeriPACTs to assess team structure and care practices.16 These data were analyzed to identify teams with high adherence to the GeriPACT model that were then recruited for additional study.

Eight geographically dispersed teams participated in further data collection, consisting of on-site structured observation of the built environment and semistructured qualitative interviews. Observations and interviews were designed using the “inner setting” domain from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).27 The CFIR is an exhaustive set of 5 domains and 39 research constructs to guide implementation scientists. The inner setting domain emphasizes the role of culture, readiness, climate, team structure, and communication in implementation (interview guides are available on request). Before the interviews, participants were provided the elements of consent. Research team members (S.L.S., O.A., M.H.S., J.M., and J.L.S.) conducted and audio-recorded the interviews on site.

Sample

Interviews were conducted with GeriPACT members at eight facilities. GeriPACTs were first debriefed with an e-mail from the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care, and then contacted by our study team to ascertain interest in participation. We completed on-site data collection over a 5-month period, resulting in 134 interviews and 8 site observations overall. Here we report our analysis of interviews conducted with core GeriPACT members (n = 67). These activities were determined to be nonhuman subjects research by the investigators’ respective institutional review boards.

Data Processing and Analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed deductively using consensus coding and then synthesis of coded data within MAXQDA, a qualitative software package.28 Members of the analytic team (S.L.S., M.J.A.S., and E.E.G.) drafted a codebook to identify each resource within the GeriPACT crosswalk of the PRF.3 The first column of Tables 2-4 liss specific resource definitions. Code clarity and fidelity were evaluated in an iterative fashion. The analytic team compared intercoder concordance using code lines, a segment-level graphic representation of code presence/absence that facilitates rapid identification of intercoder differences. Code lines facilitated identification of disagreement about interpretation of data, differences in application of codes to data, and differences in coding style (eg, including the interviewer’s question in the coded passage). After code review and discussion, the analytic team refined the codebook, coded additional interviews, and evaluated the refinement. The finalized codebook was then applied to previously coded interviews to ensure fidelity to updated code definitions. The remaining interviews were coded in sets of five, with four coded by a single analyst and the fifth coded by two. After each set, the analytic team met to review code lines for the double-coded interview to maintain code fidelity and minimize drift.

Table 2.

System-Level Resources

| Resource | Exemplar |

|---|---|

| Leadership support in meeting geriatrics-aligned goals | “This clinic is structured much differently from any other clinic.… [Y]ou have a nurse-aligned leadership that you have for nursing. And the social worker has her own manage[r]. And then the clerks… have their own clerk manager.… So [at our facility] you have all of these parallel lines of leadership for all these different service lines, but then who’s actually making any changes or addressing any issues within the actual team itself?” —GeriPACT Provider, Team B |

| Leadership support of staffing model | “We have a little shortage going on with our MSAs… [W]e do not have the ability to stop the [veteran and schedule their follow up appointment] because maybe there’s only one MSA there. We need to get an appointment [scheduled for return to clinic], but we cannot do it because [the MSA covering multiple teams has] a line for check-in and check-out that they have to address. I think that [not having a dedicated clerk] may be posing right now the biggest problem.” —GeriPACT RN, Team A |

Table 4.

Team-Level Resources

| Resource | Exemplar |

|---|---|

| Identification as a cohesive interprofessional team | “For the most part we all have our lanes to follow. But [teammate] will call… and say, “Hey, I think this is more, your thing. Could you check this out?” Same thing for [social work]… I had a grandson… called me and said, “My grandfather’s dementia suddenly became worse. He’s throwing things around in the house.” Well, I knew that it was a medical issue–I knew probably it was the UTI [urinary tract infection] or dehydration. So, you quickly assess that, get online with the geriatrician… and yep, “Let’s send him to the ED [emergency department],” that kind of thing. We really do bounce off each other for all of this.” —GeriPACT Social Worker, Team D |

| Shared purpose | “I think this team and this clinic is so special. It starts right from the top, because [the clerk is] able to identify once they check in, “Mr. J. is not looking himself,” or, you know, “He does not [seem right], usually he comes in, he’s more energetic. He’s able to check in at the kiosk.” So she’s able to report back some of the concerns she’s noticing right away. And I think that the team has been just very helpful, not for me as a professional, but I think more so for the veterans, because we are all able to understand [what’s happening with our patient]. We understand our role, and they have that contact. They know who to contact for that issue, so that they are not just trying to go to one person and that one person is trying to figure out how to get access to that resource.” —GeriPACT Clerical Associate, Team C |

| Mature communication and psychological safety | “I think the team concept in the teamlets are very essential. Because, if you have a question as it relates to a veteran it’s usually good 3 people that are in the know. So, between the provider, the RN, and the LPN, then you can pretty much get an understanding as to what’s going on, so that huddle and that communication is essential. I will say that understanding that each component of the team is important, the physician, the nurses, the [clerical associates]. Everybody’s so important, because as soon as there’s a gap in that communication, then things kind of tend to falter. When we have staff meetings there’s one that’s inclusive of the entire team, and I think that’s so important because sometimes… everybody on the team needs to understand where we are as far as nurse and staff and how that’s going to impact EVERYONE.” —GeriPACT RN, Team A |

| Clear and distinct roles | “If our PACT team was complete, I could definitely take on more.”—GeriPACT Provider, Team E “If there’s no nursing staff here in the morning I just go and get my own patients and… do vital signs–because I do not like to get behind.” —GeriPACT RN, Team E |

To analyze the coded data, the analytic team prepared code reports containing all narrative passages in a single document. Next, the team prepared code abstracts that consisted of a list of key observations for each coded passage, grouped by site. Abstracts were then synthesized into code summary documents by organizing all key observations from the abstracts by PRF resource and then by summarizing each resource in narrative form. Exemplars for each resource were selected from the code abstracts with attention paid to diversity of roles, sites, and negative examples. Exemplars were then reviewed by all authors for representativeness and fidelity (Tables 2-4).

RESULTS

In the following sections we summarize the GeriPACT experience of the key resources influencing team function, organized by level and then resource from the PRF. Tables 2-4 provide exemplars selected from the interviews to illustrate findings.

System-Level Resources (See Table 2)

Leadership Support in Meeting Geriatrics-Aligned Goals

Respondents viewed the GeriPACT model as consistent with the healthcare system mission and described how leadership support for GeriPACT appointment length and staffing facilitated the team’s ability to meet clinical goals. However, perceived support varied, with some sites reporting a feeling of invisibility to leadership and expressing leadership’s limited firsthand knowledge of GeriPACT patients’ clinical and social complexity. Respondents attributed limited leadership support to reporting structures in which individual team members reported to disparate supervisors. These reporting structures affected within-team coordination of priorities and alignment of team practices with leadership metrics (eg, a GeriPACT reporting to primary care leadership may be expected to meet primary care, rather than geriatrics metrics for appointment length).

Leadership Support of Staffing Model

All sites reported variable leadership support for the GeriPACT staffing model. Generally, fewer staff was attributed to limited clinic hours, which in turn was tied to greater emergency department use; however, staff shortages affected care differently according to role. Shortage of clinicians was thought to reduce the ability of GeriPACT providers to accept new patients. Understaffing of nurses was considered to limit their ability to provide group education, rooming efficiency, and in-clinic vaccinations. Limited clerical staffing was described as reducing capacity for care coordination and pre-appointment reminder calls. Shortage of social workers meant existing staff had less capacity for identifying, establishing, and coordinating social services. Team members were commonly shared with specialty clinics, general population PACTs, or geriatrics-aligned services (eg, palliative care teams or long-term care) in addition to their GeriPACT. Cross assignment of personnel across GeriPACTs or geriatrics-aligned services was reported as less disruptive than sharing across non–geriatrics-aligned services. GeriPACT personnel who were split across patient populations reported challenges with feeling “pulled” or “split” across competing priorities. They linked multiple team membership to decreased GeriPACT team development, quality improvement (QI) initiatives, and lower patient satisfaction with care.

Clinic-Level Resources (See Table 3)

Table 3.

Clinic-Level Resources

| Resource | Exemplar |

|---|---|

| Protected time for team development and performance | “I do [administrative work] as I go, but it depends on what kind of paperwork.… For instance, home health orders… if you do not sign the orders [the agency does not] get paid, so there’s a little bit of a higher priority on that end, so as you get those home health care orders… you sign those.” —GeriPACT Provider, Team A |

| Training and professional development | “Yeah, I wish that we could get together with other geriatric clinics or something. Because one time… they had a geriatric thing going on, but we would not have been able to [get permission from leadership] go. But that would have been nice to share ideas and be with the… and they could come and see ours… that would be really great to share.” —GeriPACT Clinical Associate, Team D |

| Appointment scheduling reflects team care processes | “I think [patients are] really happy to be here.… Not that [in other clinics] it’s not caring and they do not have a good doctor there, it’s just we– number one we have forty-five-minute blocks of time with the geriatrician. Who has that, you know? So [patients] do not feel pressure to get their concerns out–the block of time is there.” —GeriPACT Social Worker, Team D |

| Clinical and process data used to enhance performance | “[Primary care clinical performance measures are] not all that helpful [in GeriPACT] because there’s a lot of things where once you are over the age of seventy-five [do not apply. For example,]… holding all of my patients to having their A1C less than eight and like a blood pressure under a hundred and thirty-nine over eighty-nine, which for some of my geriatric patients just is not feasible or reasonable.… But we do not or at least I have not heard any metrics about [access to care].… [In primary care they] keep close tabs on that. I do not really hear anything about that in geriatrics.… Ido not think anyone has ever waited more than probably a few days [for an appointment] and that’s like if it can wait.” —GeriPACT Provider, Team H |

| Built environment and infrastructure reflect patient needs and supports team processes | “The literature’s actually declared that if every exam room is identical… yes there can be increased efficiency in clinic. But the problem with geriatric primary care, and [for my nurse] who does lot of case management of patients with chronic disease, is that she has a lot of education material. I have my walker and cane (laughs) in the exam room. How do you move that between rooms?” —GeriPACT Provider, Team E |

Protected Time for Team Development and Performance

Few respondents had dedicated time for administrative tasks, QI, or team development, and clinicians who reported “protected time” typically used it to provide direct patient care. Respondents’ comments emphasized both the time-consuming and time-sensitive nature of administrative work, particularly coordination of specialty or supportive services care with other agencies and providers outside of the team. Response time for these needs was characterized as being immediate due to patients’ advanced age and vulnerability.

Training and Professional Development

Respondents typically received general population PACT training at team launch, and a few received GeriPACT-specific training beyond attending geriatrics-relevant conferences. Training needs described by interviewees included discipline-specific training for geriatric populations (eg, nutrition for older adults), GeriPACT model training, and GeriPACT peer-to-peer training. Facility-level support for training needs varied. Teams associated with geriatrics training programs reported a great deal of support and many opportunities for continuing education, whereas others described few professional development activities.

Appointment Scheduling Reflects Team Care Processes

Across sites, empanelment was routed through a registered nurse (RN) to ensure that the patient’s needs were matched to the GeriPACT model. The appointment grid and staff access to GeriPACT scheduling influenced teams’ ability to maintain same-day access and care continuity. Appointment length varied from 30 to 60 minutes, but even sites with hour-long slots discussed time constraints in meeting patient needs. For example, appointment length needed to reflect patients’ clinical complexity, the need to answer patient and caregiver questions, provision of care from multiple team members, and patient’s physical and cognitive speed during the appointment. Respondents emphasized the importance of confirming the patient’s next appointment while the patient was still on site. This was done to address cognitive, hearing, and other problems associated with reaching a patient by phone, and to maximize the team’s ability to coordinate patient appointments with caregiver needs, within the team, and across the facility. Efforts were made to group appointments on the same day and to serve as a hub for patients to accommodate those issues, as well as to reduce potential out-of-pocket expenses and to enhance access by reducing the overall number of encounters.

Clinical and Process Data Used to Enhance Performance

Respondents’ description of data resources to inform clinical practice varied. Some discussed specific data quality issues, whereas others simply noted receiving performance reports from leadership. Respondents actively reviewed clinical or process data to triage face-to-face encounters, proactively coordinate care with inpatients and recently discharged patients, or to garner leadership support for the GeriPACT by providing supervisors with panel-level cost data. However, several clinical and process measures were described as being misaligned with geriatric standards of care, such as age-related standards for mammograms or glycemic control.

Built Environment and Infrastructure Reflects Patient Needs and Supports Team Processes

Physical co-location of team members and geriatrics-aligned space were described as central to team functioning and patient-centered care. Co-location was associated with team identity; more frequent within-team communication and “curbside” consultations; easier care coordination; fewer alerts and phone calls; and reduced burden on patients to travel within the facility, patient confusion, and anxiety. Geriatrics-aligned space needs encompassed various accessibility issues.

Examination rooms were described as too small to accommodate patients arriving for care using walkers, wheelchairs, or gurneys, or those patients arriving for care with family or other care providers. The availability of scales, lifts, and examination tables designed to accommodate patients of all mobility, ability, and sizes varied across sites. Shortage of examination rooms was reported to create inefficiencies in care processes, whereby patients may be asked to move to and from the waiting area to various examination spaces during their visit rather than the preferred model, which was to room the patient and bring care team members to a single room. Such space limitations were worse for teams with embedded clinical learners or for appointments involving multiple team members.

Shortage of meeting room space was also reported as a barrier to providing educational sessions or group encounters, and it sometimes limited the team’s ability to meet. Respondents noted patient barriers to accessing the team included limited public transportation and on-site parking challenges. Some GeriPACTs addressed these challenges by moving some care from in-person to telephone encounters, but poor hearing and cognitive acuity limited patients’ ability to communicate by phone.

Team-Level Resources (See Table 4)

Identification as a Cohesive Interprofessional Team

Team cohesion was demonstrated by examples of within-team delegation to match patient needs with clinical role. Respondents connected delegation to patient satisfaction and trust, as well as to trust and psychological safety within the team. Team members valued a work climate that fostered open dialogue and the knowledge that others on the team recognized their unique role and would proactively lend support during busy times. The importance of interprofessional knowledge was illustrated when respondents described recognizing that a patient’s needs could be better met by another team member, such as a social worker identifying a medical concern. However, pharmacists and social workers varied as to whether they felt included as core team members, and some reported that they received insufficient nursing and clerical support.

Shared Purpose

Respondents discussed the importance of their role in providing quality care to geriatric patients that was operationalized as clear, accessible veteran-to-GeriPACT communication; GeriPACT ownership of care coordination; and development of meaningful relationships with individual patients. GeriPACTs reduced communication barriers by ensuring that patients and families knew their GeriPACT team members and direct phone numbers; using daily huddles to ensure patients arrive to clinic with necessary labs and tests in hand; using multiple communication channels to provide information on next steps in cases (ie, personal phone calls, automated reminder calls, letters); and taking extra time to speak with patients to confirm their understanding.

This emphasis on communication carried over into discussions of care coordination. Respondents considered care coordination an essential component of geriatrics: coordination activities reflected recognition of age-associated travel burden, memory impairment, and acuity. Geriatrics training, temperament, and team “chemistry” were viewed as essential to the team’s purpose, due to the unique emotional demands of caring for vulnerable, declining, or dying patients. Recognition of the unique needs of older adults is further enhanced by respondents’ belief that the GeriPACT model facilitated the development of long-term personal relationships with their patients. Team-patient relationships, in turn, were described as both fostering proactive care because team members can readily identify meaningful changes in patient behaviors and because serving older adults was part of their professional calling to care for a vulnerable population and those at the end of life.

Mature Communication and Psychological Safety

Respondents described near-constant within-team communication throughout the day (eg, in person, via in-house instant messaging tools, by phone, or through the electronic health record [EHR]). Huddles were routinized aspects of team culture that provided opportunities to proactively coordinate warm handoffs and other activities to optimize the patient’s time in clinic and to accommodate unexpected acute care needs. Clinical members of the GeriPACTs participated in larger clinic-level team meetings to learn about policy changes, discuss interprofessional issues, and develop QI initiatives. Limited physical co-location of team members and clinic space were reported to impact team communication negatively. GeriPACTs tried to surmount this challenge by using the phone or computer messaging, but these technologies could not replace huddles and in turn introduced their own unique issues (eg, not all team members had dedicated office space or phone extensions).

Clear and Distinct Roles

GeriPACT roles were differentiated according to clinical licensure. GeriPACT providers saw scheduled, walk-in, and admitted GeriPACT patients, as well as non-GeriPACT patients residing in community living centers, enrolled in home-based primary care, or for geriatrics assessments. RNs functioned as the team hub and the point of contact for patients and their families. RNs primarily coordinated care, provided chronic disease management, triaged walk ins, and reviewed scheduled appointments to identify in-person visits that could be converted to telephone care or canceled to improve same-day access for acute needs. Licensed practical nurses provided more hands-on clinical care, such as rooming patients (eg, vitals, clinical reminders, medication reconciliation) and administering screeners, injections, bladder scans, vision tests, or identifying the patient’s clinical priorities.

Pharmacists provided chronic disease management, nonformulary requests, and polypharmacy reduction. Social workers saw patients on an ad hoc walk-in basis or through consultations to assist them in completing paperwork for benefits, advanced directives, and transportation, homemaker, and caregiver support services. Respondents from all roles described how clerical and nursing shortages limited their ability to perform their own roles to the fullest extent within the GeriPACT.

DISCUSSION

GeriPACT is one component of a rich continuum of geriatrics care in VA including geriatrics consultations to support care in traditional PACTs, home-based primary care, and residential community living centers.1 GeriPACT is a VA innovation using an interprofessional team to use geriatrics expertise efficiently to care for adults with complex comorbidity. GeriPACT draws from patient-centered medical home objectives to provide patient-centered,29 accessible, and high-quality primary care. Although the literature on PACT implementation and teamwork in geriatrics models of care are robust, before this study they were relatively siloed. The current PRF3-structured analysis of interviews with GeriPACTs describes facility-, clinic-, and team-level resources critical for GeriPACT implementation and brings greater attention to the importance of appropriately resourcing healthcare delivery systems tailored to the needs of older adults with complex comorbidity. Accordingly, the following discussion contextualizes the study findings within both PACT and geriatrics models of care.

At the system-level, GeriPACTs reported leadership challenges such as perceived support for team objectives, stable team membership with minimal sharing, and co-location of team members. Study of PACTs showed how leadership support limits the ability to build high-functioning teams.3,5,10,11,14 GeriPACTs described leadership support as limiting the ability of the team to provide geriatrics care by putting staffing, scheduling, and space needs in the context of patient characteristics, such as clinical complexity. Longer standard appointment times, smaller panel sizes, and team member continuity were considered by interviewees as not simply workload issues, but as central to being able to provide care for patients accompanied by caregivers, and patients with dementia, mobility limitations, or anxiety.16

These reports are consistent with the work of Hinton et al demonstrating that typical primary care appointments are too brief to manage aspects of dementia care that involve family members or care partners or referral to community services.19 Primary care providers may have greater reliance on psychiatry consults to manage dementia,19 whereas GeriPACTs with mental health providers have within-team expertise that enables them to provide behavioral counseling, care management, and referral within their practice.22,24,30 Evaluation of a primary care model in which a geriatrician was co-located with a PACT trialed in the VA Boston Healthcare System showed a reduction in some subspecialty visits.31

At the clinic level, GeriPACT members reported time constraints regarding their ability to engage in QI activities, participate in training, and accommodate both acute same-day and scheduled encounters, as well as preferences for all team member co-location to facilitate teamwork and warm handoffs. Despite studies reporting similar implementation issues in PACTs,14,16,32 we note important differences in the rationale of the GeriPACT for QI, discussion of role clarity, administrative and EHR labor, and features of the built environment. Research examining QI work within PACTs emphasizes the role of primary care providers in leading within-team care processes and role redesign.8,12 Within GeriPACT, QI was often led by embedded learners and used strategically to demonstrate the GeriPACT business case to facility management (eg, a GeriPACT-associated reduction in emergency department use).

Prior work examining medical home team use of EHRs across sectors showed infrastructure issues with data acquisition, data specificity, availability of actionable or team-level data, and reliability.13,14,33 GeriPACTs’ discussion of data needs emphasized performance metrics that are better calibrated to their panel’s advanced age. Others34 have noted that EHR data do not include factors indicating patient need for more intensive support that would facilitate empanelment in programs such as GeriPACT.

Across sectors, medical home implementation research has illustrated the importance of role redesign and clarity8,35-38 that is likely in part due to the traditional organization of primary care staff by discipline rather than team. GeriPACTs did not describe role clarity as a core implementation issue, potentially because many were working in an interdisciplinary team environment before GeriPACT implementation1 or because of their recognition that clinically complex patients required interprofessional expertise. Such recognition is reflected in respondents’ discussion of care coordination as central to high-quality care for complex patients.

For example, both PACTs3,33 and GeriPACTs report overload from EHR and administrative tasks, but where PACTs report need for “protected” nonclinical time, GeriPACT providers report the need to complete this work in near real time due to the immediacy of patient needs. PACTs3 and GeriPACTs report similar needs for physical co-location of team members and adequate number of assigned examination rooms, but GeriPACT respondents noted additional space needs related to their patient population. GeriPACTs also need examination rooms that can accommodate wheelchairs, lifts, and a larger number of people. Adjustable examination tables are also helpful because they are more comfortable for patients with mobility limitations, provide safer transfer, and may facilitate more thorough physical exams.17,39

At the team level, GeriPACT respondents noted the importance of psychological safety, warm handoffs and huddles, and personal investment in caring for older veterans. Effective communication style and frequency, particularly huddles, were also associated with better PACT implementation.4-6,37 GeriPACT features of teamwork were associated with patient outcomes, such as reducing patient anxiety, a finding also demonstrated in the Embrace model that reported “being supported, being monitored, being informed, and being encouraged provided participants with a sense of being in control and of being safe and secure.”40 Research on team implementation in general population primary care demonstrates there are significant challenges to within-team delegation deriving from lack of trust and team member continuity.7,32,35,37,8 Poor teamwork contributes to provider burnout, as reported in several PACT studies.12,38 GeriPACT respondents in this study did report burnout. However, it was generally related to the emotional labor of caring for older adults than within-team conflict.

The resources we identified as critical to GeriPACTs echo delivery model and internal resources were reported by Ganz et al in their discussion of high-quality primary care of vulnerable older adults.17 Yet our cross-sectional study of the organizational resources required to support GeriPACT functioning is not without its limitations. Our analytic frame drew on our extensive experience studying PACT implementation; however, we did not conduct a true head-to-head comparison. We also note that our analysis lacks attention to patient experiences that were regrettably beyond the scope of this ambitious study.

Given the confluence of an aging population and downward trend in the number of geriatrics-trained clinicians,15 healthcare systems must identify innovative approaches to stewarding clinical expertise while providing high-quality care to the most vulnerable older adults and middle-aged adults with complex comorbidity. Our study illustrates the organizational resources GeriPACTs need to support their work and the potential value added for geriatric primary care patients, but further research is warranted to (1) demonstrate GeriPACT’s cost effectiveness25 and establish a business case for reimbursement models in the private sector15,26,41; (2) identify the patients most likely to benefit from GeriPACT and the extent to which GeriPACT can “effectively decompress primary care by removing Veterans who require more attention from the primary care patient mix”1; and (3) understand patient experience and satisfaction with such delivery models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Ken Shay and the VA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care for instrumental support in site recruitment; members of the Primary Care Analytics Team, Iowa City, Monica Paez and Brenda Boese for assistance with data processing; Enzo Yaksic for assistance collecting data in the larger evaluation; and the participating GeriPACT members.

Financial Disclosure:

Samantha L. Solimeo, Melissa J.A. Steffen, Omonyêlé Adjognon, Marlena H. Shin, Jennifer Moye, and Jennifer L. Sullivan received support for this research from VA QUERI (Award PEI-15-468) (principal investigator Jennifer L. Sullivan). Samantha L. Solimeo is a VA HSR&D Career Development awardee at the Iowa City VA (Award CDA 13-272). Samantha L. Solimeo and Melissa J.A. Steffen received partial support for this work from the Center for Access & Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE), Department of Veterans Affairs, Iowa City VA Health Care System, Iowa City, IA (Award CIN 13-412) and the Primary Care Analytics Team-Iowa City, Iowa City VA Health Care System, Iowa City, IA, which is funded by the VA Office of Patient Care Services.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All the authors except Ellen E. Gardner are employees of the Department of Veterans Affairs. All the authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

Sponsor’s Role: None of the funding sources had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors anddo not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US government or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Related presentations: A presentation related to this article was presented at the VA Health Services Research & Development Scientific Meeting (October 29, 2019) and at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America (November 16, 2019).

REFERENCES

- 1.Shay K, Schectman G. Primary care for older veterans. Generations. 2010;34(2):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Veterans Affairs. Geriatric Patient-Aligned Care Team (GeriPACT). Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.True G, Stewart GL, Lampman M, Pelak M, Solimeo SL. Teamwork and delegation in medical homes: primary care staff perspectives in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29((suppl 2):S632–S639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim LY, Giannitrapani KF, Huynh AK, et al. What makes team communication effective: a qualitative analysis of interprofessional primary care team members? Perspectives. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(6):836–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stout S, Zallman L, Arsenault L, Sayah A, Hacker K. Developing high-functioning teams: factors associated with operating as a “real team” and implications for patient-centered medical home development. Inquiry. 2017; 54:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez HP, Chen X, Martinez AE, Friedberg MW. Availability of primary care team members can improve teamwork and readiness for change. Health Care Manage Rev. 2016;41(4):286–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrod M, Weston LE, Robinson C, Tremblay A, Greenstone CL, Forman J. “It goes beyond good camaraderie”: a qualitative study of the process of becoming an interprofessional healthcare “teamlet”. J Interprof Care. 2016; 30(3):295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiscella K, McDaniel SH. The complexity, diversity, and science of primary care teams. Am Psychol. 2018;73(4):451–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giannitrapani KF, Soban L, Hamilton AB, et al. Role expansion on interprofessional primary care teams: barriers of role self-efficacy among clinical associates. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4:321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giannitrapani KF, Leung L, Huynh AK, et al. Interprofessional training and team function in patient-centred medical home: findings from a mixed method study of interdisciplinary provider perspectives. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(6):735–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giannitrapani KF, Rodriguez H, Huynh AK, et al. How middle managers facilitate interdisciplinary primary care team functioning. Healthc (Amst). 2019;7(2):10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards ST, Helfrich CD, Grembowski D, et al. Task delegation and burn-out trade-offs among primary care providers and nurses in veterans affairs patient aligned care teams (VA PACTs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(1):83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen DJ, Dorr DA, Knierim K, et al. Primary care practices’ abilities and challenges in using electronic health record data for quality improvement. Health Aff. 2018;4:635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solimeo SL, Stewart KR, Stewart GL, Rosenthal G. Implementing a patient centered medical home in the Veterans health administration: perspectives of primary care providers. Healthc (Amst). 2014;2(4):245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flaherty E, Bartels SJ. Addressing the community-based geriatric healthcare workforce shortage by leveraging the potential of interprofessional teams. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S400–S408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan JL, Eisenstein R, Price T, Solimeo S, Shay K. Implementation of the geriatric patient-aligned care team model in the Veterans health administration (VA). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):456–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganz DA, Fung CH, Sinsky CA, Wu SY, Reuben DB. Key elements of high-quality primary care for vulnerable elders. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):2018–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harlow EN, Bishop KI, Crowe JD, Potter JF, Jones KJ. Using team training to transform practice within a geriatrics-focused patient-centered medical home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(7):1529–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinton L, Franz CE, Reddy G, Flores Y, Kravitz RL, Barker JC. Practice constraints, behavioral problems, and dementia care: primary care physicians’ perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):1487–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoff T, DePuccio M. Medical home implementation gaps for seniors: perceptions and experiences of primary care medical practices. J Appl Gerontol. 2018;37:817–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warshaw G. Providing quality primary care to older adults. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(3):239–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasin-Waters D, Abel V, Kearney LK, Zeiss A. The integrated care team approach of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA): geriatric primary care. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2018;33(3):280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns R, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Graney MJ. Interdisciplinary geriatric primary care evaluation and management: two-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moye J, Harris G, Kube E, et al. Mental health integration in geriatric patient aligned care teams in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(2):100–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards ST, Peterson K, Chan B, Anderson J, Helfand M. Effectiveness of intensive primary care interventions: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1377–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reuben DB. Better ways to care for older persons: is anybody listening? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(12):2348–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, Kirsh S, Alexander J, Lowery J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Sci. 2009;4(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VERBI software. MAXQDA Plus. Version 18.2.0. Berlin, Germany; 2018. maxqda.com. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kogan AC, Wilber K, Mosqueda L. Person-centered care for older adults with chronic conditions and functional impairment: a systematic literature review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):E1–E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraser MW, Lombardi BM, Wu SY, Zerden LD, Richman EL, Fraher EP. Integrated primary care and social work: a systematic review. J Soc Soc Work Res. 2018;9(2):175–215. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engel PA, Spencer J, Paul T, Boardman JB. The geriatrics in primary care demonstration: integrating comprehensive geriatric care into the medical home: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(4):875–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patterson BJ, Solimeo SL, Stewart KR, Rosenthal GE, Kaboli PJ, Lund BC. Perceptions of pharmacists’ integration into patient-centered medical home teams. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015;11(1):85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solimeo SL, Hein M, Paez M, Ono S, Lampman M, Stewart GL. Medical homes require more than an EMR and aligned incentives. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):132–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia ME, Uratsu CS, Sandoval-Perry J, Grant RW. Which complex patients should be referred for intensive care management? A mixed-methods analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(9):1454–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solimeo SL, Ono SS, Lampman MA, Paez MB, Stewart GL. The empowerment paradox as a central challenge to patient centered medical home implementation in the Veteran’s health administration. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(1):26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart KR, Stewart GL, Lampman M, Wakefield B, Rosenthal G, Solimeo SL. Implications of the patient-centered medical home for nursing practice. J Nurs Adm. 2015;45(11):569–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solimeo SL, Ono SS, Stewart KR, Lampman MA, Rosenthal GE, Stewart GL. Gatekeepers as care providers: the care work of patient-centered medical home clerical staff. Med Anthropol Q. 2017;31(1):97–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart GL, Astrove SL, Reeves CJ, Crawford ER, Solimeo SL. Those with the most find it hardest to share: exploring leader resistance to the implementation of team-based empowerment. Acad Manage J. 2017;60(6):2266–2293. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maragh-Bass AC, Griffin JM, Phelan S, Rutten LJF, Morris MA. Healthcare provider perceptions of accessible exam tables in primary care: implementation and benefits to patients with and without disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2018;11(1):155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spoorenberg SLW, Wynia K, Fokkens AS, Slotman K, Kremer HPH, Reijneveld SA. Experiences of community-living older adults receiving integrated care based on the chronic care model: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0137803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruikes FGH, Adang EM, Assendelft WJJ, Schers HJ, Koopmans R, Zuidema SU. Cost-effectiveness of a multicomponent primary care program targeting frail elderly people. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]