Abstract

Policy Points.

Local governments are increasingly adopting policies that earmark taxes for mental health services, and approximately 30% of the US population lives in a jurisdiction with such a policy.

Policies earmarking taxes for mental health services are heterogenous in their design, spending requirements, and oversight.

In many jurisdictions, the annual per capita revenue generated by these taxes exceeds that of some major federal funding sources for mental health.

Context

State and local governments have been adopting taxes that earmark (i.e., dedicate) revenue for mental health. However, this emergent financing model has not been systematically assessed. We sought to identify all jurisdictions in the United States with policies earmarking taxes for mental health services and characterize attributes of these taxes.

Methods

A legal mapping study was conducted. Literature reviews and 11 key informant interviews informed search strings. We then searched legal databases (HeinOnline, Cheetah tax repository) and municipal data sources. We collected information on the year the tax went into effect, passage by ballot initiative (yes/no), tax base, tax rate, and revenue generated annually (gross and per capita).

Findings

We identified 207 policies earmarking taxes for mental health services (95.7% local, 4.3% state, 95.7% passed via ballot initiative). Property taxes (73.9%) and sales taxes/fees (25.1%) were most common. There was substantial heterogeneity in tax design, spending requirements, and oversight. Approximately 30% of the US population lives in a jurisdiction with a tax earmarked for mental health, and these taxes generate over $3.57 billion annually. The median per capita annual revenue generated by these taxes was $18.59 (range = $0.04‐$197.09). Per capita annual revenue exceeded $25.00 in 63 jurisdictions (about five times annual per capita spending for mental health provided by the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration).

Conclusions

Policies earmarking taxes for mental health services are diverse in design and are an increasingly common local financing strategy. The revenue generated by these taxes is substantial in many jurisdictions.

Keywords: mental health, public policy, taxation, earmarked tax, excise tax

Introduction

Mental health services are financed through a complex mix of federal, state, and often local sources in the United States. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Scholars have argued that this financing model has historically been suboptimal and the consequence of a sociopolitical context in which mental health is valued less than physical health and stigma toward people with mental illness is pervasive. 1 , 5 , 6 Examples of policies that have been identified as being emblematic of the shortcomings of mental health financing in the United States include but are not limited to lack of parity insurance coverage for mental health conditions, 7 , 8 exclusion of “institutions for mental disease” from Medicaid coverage, 9 and low reimbursement rates for mental health services. 10 The sociopolitical context surrounding mental health, however, is changing.

Improving access to quality mental health services has become an increasingly salient public concern over the past decade, especially after the COVID‐19 pandemic. This shift has likely been prompted by worry about rising rates of suicide 11 , 12 and mental health problems 13 , 14 , 15 and decreases in stigma toward people with mental illness. 16 Public opinion research about mental health financing illustrates concern about the issue. Multiple studies have found that US adults are willing to pay higher taxes to increase funding for mental health services. 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 Surveys conducted in 2017 found that 42% of respondents were willing to pay an additional $50 annually to improve the mental health service system, 18 and 58% were willing to pay this for social services (e.g., supportive housing and employment) for people with serious mental illness. 19 A 2018 discrete choice experiment observed levels of support for policies and spending to improve mental health that were significantly higher than those to address other health and social issues. 21

Mental health has also risen on the agendas of state and local policymakers. The proportion of US state legislators identifying “mental health” as one of their top three health priorities, out of a list of 19, increased from 8% in 2012 22 to 37% in 2017. 23 A 2016 survey of US city mayors and their staff found that 55% (the largest proportion) identified mental health as one of their top two health priorities out of a list of seven, followed by substance misuse (52%). 24 It is from these contexts that earmarked taxes for mental health services have emerged as an increasingly popular financing strategy.

Earmarked Taxes and Health Policy

An earmarked tax is one for which revenue is dedicated to a specific purpose, as opposed to being allocated to a general fund where revenue is allocated based on political decision making. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Earmarked taxes have long been used as a financing strategy for policy issues that have broad public support. Revenue from excise taxes—which are imposed on specific goods and services (e.g., alcohol and tobacco)—are often earmarked to offset externalities (i.e., societal impacts) of these goods and services (e.g., alcohol and tobacco‐related health care costs). 29 Earmarked taxes have become increasingly common at state and local levels in the United States across a range of policy areas (e.g., transportation, education). 30

The growing popularity of state and local earmarked taxes corresponds with, and is likely in part the result of, declines in trust in government (especially at the federal level) and decreases in support for general tax increases. 31 , 32 A benefit of earmarked taxes is that they are often politically feasible because they guarantee that revenue will be spent on specific issues of public concern, 30 , 33 as opposed to being spent at the discretion of elected officials who are increasingly perceived as untrustworthy. 31 , 32 Other potential benefits of earmarked taxes include securing a stable revenue stream for specific issues—protected from the politics of general budget processes—to increase in overall funding. 34 However, evidence is mixed on whether earmarked taxes result in net increases in spending on the issue for which revenue is dedicated. 35 , 36 , 37 This is because of supplantation—a potential drawback of earmarked taxes—in which elected officials reduce allocations from the general fund for an issue because the issue already has a separate and dedicated (i.e., earmarked) revenue source. 38

In the area of health, earmarks have typically been applied to excise taxes on goods and services that produce harms to public health. 29 , 39 These taxes have typically had the dual goal of reducing consumption of the good or service and generating revenue for investments in public health. Widely studied examples include excise taxes on tobacco, 40 alcohol, 41 indoor tanning, 42 and sugar sweetened beverages. 43 , 44 Earmarked taxes have also been placed on a variety of goods and services to generate revenue for mental health services, but these taxes have received limited scholarly attention.

As reported in a 2019 commentary, two states adopted high‐profile earmarked taxes for mental health services in 2005. 25 In California, the Mental Health Services Act (also known as Proposition 63) increased the income tax rate by one percentage point for households with annual income over $1 million and earmarked this revenue for mental health services. In Washington state, E2SSB‐5763 granted counties the ability to increase their sales tax rate by 0.1% percentage point to increase funding for mental health services. The commentary identified other jurisdictions earmarking taxes for mental health services (e.g., Denver, Colorado; Chicago, Illinois; St. Louis, Missouri) but did not provide details about these taxes. A 2022 commentary described why earmarking recreational marijuana excise taxes might be a promising financing strategy for mental health crisis services and summarized the extent to which these taxes have been earmarked for mental health. 45 In sum, earmarked taxes for mental health services have received some scholarly attention but have not been the focus of systematic inquiry.

Current Study

The current study seeks to address this knowledge gap through a legal mapping study—which entails the systematic identification and collection of information about a policy issue 46 , 47 —of earmarked taxes for mental health services at state and local levels in the United States. This cross‐sectional study sought to identify all jurisdictions in the United States that have these taxes at the time of the study (2021‐2022) and catalog information about the following: 1) the year the tax went into effect, 2) passage by ballot initiative (yes/no), 3) tax base (i.e., source), 4) tax rate, and 5) the amount of revenue generated annually (gross and per capita within the jurisdiction).

This study can contribute to mental health policy research, practice, and theory. First, many prior studies have assessed the effects of government mental health expenditures on mental health outcomes, service utilization, and service implementation. 3 , 48 , 49 To our knowledge, however, no studies have accounted for revenue generated by earmarked taxes for mental health in these analyses. The current study enables such research by creating a publicly accessible database with information about these taxes at the state and local level. Second, for policymakers and advocates, the study produces potentially useful information about the diversity of ways in which earmarked taxes have been designed to finance mental health services. Third, the study can contribute to theory about mental health politics and policy by characterizing the attributes of these taxes at different levels of government.

Methods

Our methods followed recommended practices for legal mapping studies. 46 , 47 , 50 The study was approved by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board.

Key Informant Interviews

We first conducted 11 key informant, semistructured Zoom/telephone interviews with national experts on earmarked taxes and mental health financing more broadly. Informants were identified through Internet searches and the investigators’ professional networks. Interview respondents included academics in schools of law and public administration, taxation experts at national government and budget organizations, and policy directors of national mental health professional and advocacy organizations. The interviews focused on three topics: 1) potential benefits of earmarking taxes for mental health services, 2) potential drawbacks of these taxes, and 3) suggestions about the search terms and legal databases we should use in our legal mapping study. The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed in NVivo 12 using qualitative content analysis. 51

Search Strategy for Policy Identification

We began our process to identifying all policies that earmarked taxes for mental health services and were effective in 2021–2022 in two databases of state and municipal laws: HeinOnline (which is limited to state laws) and Cheetah legal database (which includes local laws, now known as VitalLaw), a database dedicated to tax laws. Within the tax section of HeinOnline and Cheetah, we used the following search string, which was informed by the key informant interviews: (“mental health” “psychiatric” OR “psychol” OR “behavioral health” OR “emotional” OR “mental illness” OR “mental disorder” OR “behavioral disorder” OR “mental distress”) AND (“restricted” OR “special tax” OR “fee” OR “surcharge” OR “earmark”). We limited our search to laws that had been enacted and did not limit our search to a specific timeframe because we sought to identify all policies “on the books.” Based on feedback from key informants, we included fees earmarked for mental health services in addition to taxes.

Per suggestions from key informants, we also searched four types of sources in addition to legal databases. First, we searched for mental health and tax related terms on the following organizations’ websites: National Association of State Budget Officers, National League of Cities, National Association of Counties, American Tax Policy Institute, National Conference of State Legislatures, and the Tax Policy Center of the Urban Institute. Second, we searched for mental health terms in the ballot initiatives section of Ballotpedia (a continually updated encyclopedia of ballot and election outcomes). Third, we searched for mentions of “tax” in articles published in Mental Health Weekly, a trade publication for public mental health officials. Fourth, we reviewed information about the taxation of recreational/medical marijuana on Leafly (a marijuana industry news website). When jurisdictions with earmarked taxes for mental health were identified, we searched state and local government websites (e.g., department of revenue and treasury web pages) for mental health–related terms and also called and e‐mailed government officials and submitted Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to obtain information about tax revenue. Finally, we contacted organizations involved with tax implementation within the jurisdictions (e.g., state community mental health and county associations) to gain clarity about ambiguous aspects of the taxes.

Data Management and Extraction

Using the information generated from this search strategy, we created a database containing information about five key attributes of each tax: jurisdiction, year the tax went into effect, passage by ballot initiative (yes/no), tax base (e.g., income, property, sales), tax rate, and amount of annual revenue generated. US 2020 Decennial Census estimates of population size were used to calculate estimates of annual revenue per capita in each jurisdiction. We summed the county population sizes when taxes were collected and allocated via multicounty boards. Property tax “millage rates,” which are expressed dollars per $1,000 property valuation, were converted to percentages to facilitate consistent interpretation with sales and income tax rates. We also searched PubMed and conducted Internet searches to identify scholarly literature and reports about each tax.

Given substantial heterogeneity in the specifics of tax design across jurisdictions, we first present descriptive statistics for all taxes identified and then present results in case study format. These case studies describe earmarked taxes for mental health in five states—which vary in the design of their earmarked taxes for mental health—and two broad categories of taxes/fees that span multiple states. These case studies comprise 92% of the total number of taxes identified in the study.

Results

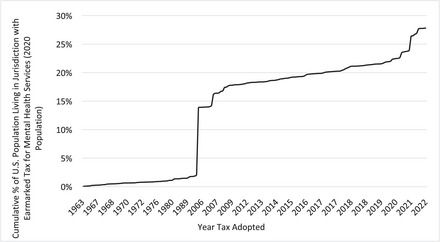

We identified 207 policies earmarking taxes for mental health services in the United States. The Appendix contains summary information about each tax (also available via open access: https://osf.io/6bt8y/). Eight (5.1%) of these taxes were at the state level, and 148 (94.9%) were at a county, city, or smaller municipality level. One hundred ninety‐eight (95.7%) of these taxes became law via a ballot initiative. The earliest tax identified became effective in 1963. Seventy‐seven (49.4%) of the taxes identified went into effect after 2000. Figure 1 shows the increase in the cumulative percentage of the US population living in jurisdictions with a tax earmarked for mental health services between 1963 and 2022, using 2020 Decennial Census data to produce estimates for consistency in comparison across years. The sharpest increase occurred in 2005 when California passed the Mental Health Services Act (detailed in the “California” section). Approximately 100,490,502 million people (about 30% of the US population) lived in a jurisdiction that had an earmarked tax for mental health in 2022.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Percentage of US Population Living in a Jurisdiction with an Earmarked Tax for Mental Health Services, 2020 Decennial Census Data. Notes: Chart excludes a 1967 Illinois law that earmarked a portion of Bingo proceeds income for mental health services, which generated $0.04 per capita in 2021. This was excluded because inclusion would mask the gradual diffusion of local “708 mental health board” taxes that have spread across Illinois (detailed in text). n = 192 jurisdictions; reliable information on tax effective year was not available for 15 jurisdictions. For Ohio jurisdictions, the effective year reflects the most recent renewal of the levy. The chart does not include Iowa counties.

As shown in Table 1, property taxes (153 taxes, 73.9% of those identified) and sales taxes/fees (52 taxes/fees, 25.1% of those identified) were most common. Among the 186 taxes for which revenue data were available, the aggregated amount of revenue generated was $3,569,878,474. The median per capita annual revenue generated within the jurisdictions was $18.59, ranging from $197.09 per capita in Pitkin County, Colorado (property tax) to $0.04 in Illinois (bingo proceeds tax). Per capita annual revenue exceeded $50.0 in 12 jurisdictions and $25.0 in 63 jurisdictions. The median annual per capita revenue generated was highest for income taxes ($35.10), followed by sales taxes/fees ($25.10) and property taxes ($17.15).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Earmarked Taxes for Mental Health Services, Stratified by Tax Base

| Tax Base | Number of Taxes Identified | Percentage of Taxes Identified | Mean Annual Per Capita Revenue | Standard Deviation of Annual Per Capita Revenue | Median Annual Per Capita Revenue | Range in Annual Per Capita Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 207 | 100% | $23.19 | $20.82 | $18.59 | $0.04, $197.09 |

| Property | 153 | 73.9% | $21.78 | $21.81 | $17.15 | $1.97, $197.09 |

| Sales/fees | 52 | 25.1% | $27.02 | $19.52 | $25.10 | $0.15, $115.93 |

| Income | 2 | 1.0% | $35.05 | $49.52 | $35.10 | $0.04, $70.07 |

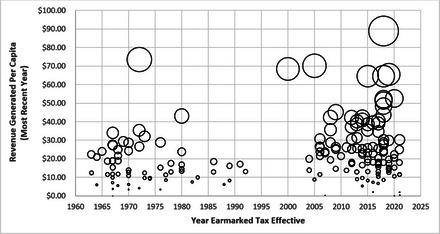

Figure 2 plots the year the tax went into effect (x axis) and annual per capita revenue generation (y axis), with the size of the circle being proportional to annual per capita revenue generation. The pattern illustrates an increase in the frequency of earmarked taxes for mental health going into effect over time, number of people living in a jurisdiction with an earmarked tax for mental health, and the magnitude of annual per capita revenue generation.

Figure 2.

Effective Year of A Tax Earmarked for Mental Health Services by Annual Per Capita Revenu Generated, n = 173 Taxes. Note: The size of circles is proportional to the amount of annual per capita revenue generated. The figure does not include two outlier jurisdictions that generated over $100 per capita annually (Pitkin County, Colorado, $197.09 per capita annually, and Mendocino, California, $115.93 per capita annually).

California

Created through a ballot initiative in 2005, the Mental Health Services Act (Proposition 63) increased the income tax rate by one percentage point for all state residents with taxable household income exceeding $1 million. Revenue from this tax is earmarked for five categories of mental health services: community services and support, prevention and early intervention, capital facilities and technological needs, workforce education and training, and innovation. Revenue is collected by the state and allocated to all counties using a formula that accounts for county population size and other characteristics. 52 Tax revenue is allocated by the California Mental Health Oversight and Accountability Commission, which also oversees spending and reporting requirements. In fiscal year 2020–2021, the tax generated a $2,770,427,035, which equates to 77.6% of the total annual revenue of earmarked taxes identified in the study. The California tax generates $70.07 per capita annually, among the largest per capita amounts identified.

The California tax has been the focus of more research than other taxes identified. For example, studies have used quasi‐experimental, multistate difference‐in‐difference designs to evaluate the effects of the tax on suicide death 53 ; single‐state pre‐post designs have compared client and provider outcomes between mental health clinics that did and did not receive tax revenu, 54 used claims data to assess the effect of the tax on the reach of prevention/early intervention services, 55 explored barriers and facilitators to the sustainment of evidence‐based treatments following tax adoption, 56 and evaluated a statewide mental illness stigma reduction campaign funded by the tax. 57 A study also assessed whether the mental health tax prompted households with income exceeding $1 million to leave the state, finding little evidence that the tax had this effect. 58

Washington

As enacted by the Washington State Legislature in 2005 (E2SSB‐5763, An Act Relating to the Omnibus Treatment of Mental and Substance Abuse Disorders act of 2005), counties have the ability to pass a 0.1% sales tax increase to expand funding for mental health services. Counties can adopt the tax by obtaining a majority vote in a ballot initiative. There are fairly loose restrictions regarding how tax revenue can be allocated, with the authorizing legislation stating that revenue must be spent on “treatment services, case management, transportation, and housing that are a component of a coordinated chemical dependency or mental health treatment program or services.” Every jurisdiction that adopts the tax must establish and operate a therapeutic court for substance use disorder proceedings. 59 Counties that adopt the tax must report revenue information to the Washington State Department of Revenue, but counties individually collect the revenue, make decisions about how it is allocated, and monitor spending.

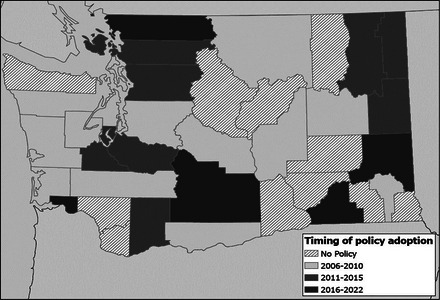

As of 2022, 28 of the 39 counties in the state had adopted the tax. Figure 3 shows the geographic distribution of counties by the year the tax went into effect, illustrating the gradual spread of adoption over the past two decades. In 2021, the most recent year for which tax revenue data were available, these taxes generated a total of $173,676,029. The amount of annual per capita revenue generated ranged from $11.04 in Pend Oreille County ($153,236 gross) to $44.99 in San Juan County ($803,106 gross).

Figure 3.

Counties in Washington State that Adopted a 0.1% Sales Tax Increase Earmarked for Mental Health Services, By Effective Year Map credit: Brent Langellier, Drexel University.

Although we did not identify any studies focused on the implementation and impacts of the earmarked taxes for mental health in Washington state, studies have assessed the impacts of services that were exclusively funded by the tax. For example, evaluation of a tax‐funded family treatment drug court in King County found that the program improved outcomes for both parents and children. 59

Missouri

There are three state laws in Missouri that explicitly allow counties and the City of St. Louis to earmark taxes for mental health services via ballot initiatives. The first state law was passed in 1969 (RSMo 205.977). The law allows counties and the city to increase their property tax by up to 40 cents per $100 property valuation to furnish revenue to a Community Mental Health Fund for mental health services, with no explicit restrictions regarding services that cannot be funded. 60 In 1993, an additional state law (RSMo 210.860–861) allowed local jurisdictions to increase their property tax by an additional 50 cents per $100 property valuation to create a Community Children's Services Fund that finances mental health and social services for youth. There are no restrictions on the types of services that cannot be funded, with the exceptions of inpatient treatment and transportation. A Missouri Local Tax Match Fund provides state funds to local governments equivalent to the amount of the mental health property tax revenue that was allocated to services for Medicaid recipients. 61 Eleven counties and the City of St. Louis have adopted a property tax earmarked for mental health. These taxes generated $30,883,285 in 2019. Annual per capita revenue ranged from $25.02 in Sainte Genevieve County ($462,260 gross) to $13.10 in St. Louis City ($3,951,333 gross).

In 2000, a third state law (RSMo 67.1775.1) permitted counties to impose a sales taxes increase, in addition to any property taxes earmarked for mental health, with this revenue dedicated to youth mental health services. In 2022, eight counties had adopted the sales tax increase. The amount of per capita revenue ranged from $42.29 in St. Louis County ($42,462,150 gross) to $8.82 in Lafayette county ($310,933 gross).

We identified two reports focused on taxes earmarked for mental health in Missouri60,61—one by Missouri KIDS COUNT, a local nonprofit, and one by the Center for Economics and Health Policy at Washington University in St. Louis. Both reports include case studies describing how tax revenue has been used in adopting jurisdictions. We did not identify any studies evaluating the implementation or impacts of the taxes.

Illinois

Enacted by the Illinois state legislature in 1967, the Community Mental Health Services Act (405 ILCS 20) explicitly allows local governments to increase their property tax by up to 0.15% to create a Community Mental Health Fund. Some counties had already adopted such taxes before passage of the state law (e.g., Moultrie County and St. Clair County in 1963). A majority vote in a ballot initiative is needed to pass the tax, and there are not explicit restrictions on mental health services that cannot be funded with tax revenue.

Spending and oversight are carried out by seven‐member community mental health boards, colloquially known as “708 mental health boards” and named after the legislative resolution that authorized creation of the boards. Boards must prepare an annual report with information about revenue and spending and submit a copy to the Illinois Department of Human Services (IDHS) on the department's request. We submitted an FOIA request to IDHS requesting these reports, but the response stated that the reports were not collected annually or maintained in a central repository.

Drawing from a 2019 report by the Association of Community Mental Health Authorities of Illinois, 62 supplemented by additional Internet searches, we identified 71 jurisdictions in Illinois that had 708 mental health boards—51 counties, 17 townships, and 3 cities. Some of these jurisdictions have established a regional approach to revenue allocation. 62 We obtained information about tax revenue for 63 of the jurisdictions. The median per capita revenue generated annually was $12.73 and ranged from $2.56 in Clay County ($34,000 gross) to $73.52 in Riverside Township ($683,607 gross).

In 2012, the Illinois legislature passed an additional law, the Community Expanded Mental Health Services Act (405 ILCS 22), which permits “territories” within a municipality with a population >1 million to increase the local property tax by 0.025% to 0.044% to create an Expanded Mental Health Services Program that provides mental health services to residents at no cost. The City of Chicago is the only municipality meeting the population size criterion and “community areas” within the city are the geopolitical units that serve as “territories.” Four territories in Chicago have adopted property tax increases of 0.025%: North River (2012); West Side (2016); Bronzeville (2020); and Logan Square, Avondale, and Hermosa (2018). Revenue data were only available for the West Side jurisdiction, where the tax generated $2.10 per capita annually ($938,642 gross). We did not identify any studies examining the impact or implementation of earmarked mental health taxes in Illinois.

Colorado

In Colorado, 10 local jurisdictions have adopted policies earmarking taxes for mental health, without state legislation explicitly authorizing such taxes. These taxes were recently adopted, with nine going into effect in 2018 and one going into effect in 2017. Six of these taxes are property taxes, and four are sales tax increases. These taxes are heterogenous in terms of their design, extent to which they are focused on mental health, and magnitude of revenue generation. The largest of these taxes in gross revenue generation is a 0.25% sales tax increase adopted by the City and County of Denver ($51.46 per capita, $36,822,629 gross). The tax is broadly intended to fund mental health, suicide prevention, and substance use services with limited restrictions on the services that can be funded. Per the tax policy, revenue is distributed by a nonprofit organization that was created by the tax. In contrast, a 0.185% sales tax increase in Boulder County was less directly focused on mental health. The tax increase, which sunsets after five years, is earmarked to finance the construction of an alternative sentencing facility at the county jail that meets the “mental and physical health needs of inmates.” Property tax increases in three counties—Adams, Douglas, and Jefferson—were earmarked for initiatives that included mention of student mental health and school‐based mental health services.

A report by Mental Health Colorado details case studies of many of these taxes, highlighting social and political factors surrounding their passage. 63 We did not identify any studies focused on the earmarked taxes for mental health within the state.

Ohio

Per ORC 5705.191, multicounty Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health boards and, in single counties, boards of county commissioners in Ohio have the ability to propose tax levies to supplement the general fund and generate and allocate revenue for mental health and substance use services and facilities. 64 Levies are adopted via local ballot initiatives. The office of the Ohio Auditor of State and the Ohio Association of County Behavioral Health Authorities (OCCBHA) published a detailed description of this earmarked mental health financing model. 64 We obtained data on local tax levies from a database maintained by OCCBHA. The effective year reflects the most recent renewal of the levy and accompanying rate. Many multicounty boards and counties have had levies in place before the documented effective year (e.g., 1970 in Franklin County 65 ), and the tax rates have fluctuated within jurisdictions over time.

In 2022, 75 of the 88 counties in Ohio had a property tax levy earmarked for mental health. For 35 counties, revenue was collected and allocated through a multicounty board, whereas the remainder operated as independent counties. In 2021, the most recent year for which tax revenue data were available, these taxes generated an estimated total of $252,775,724. The amount of annual per capita revenue ranged from $7.37 in Jefferson County ($485,000 gross) to $65.60 in Summit County ($35,552,323 gross).

Iowa

Iowa is a unique case because it recently, in July 2021, eliminated a local property tax levy‐driven mental health financing system and adopted a state‐based financing structure. 66 For over 150 years—since the passage of a state “Poor Law” in 1842—Iowa counties levied property taxes, with varying rates, earmarked for mental health asylums and services. In July 2013, SF2315 went into effect and capped the amount of revenue a county could generate with its property tax levy at $47.28 per capita. 67 In July 2021, SF619 eliminated the county property tax levies earmarked for mental health and created a new financing structure in which the state assumes the primary responsibility for financing mental health services.

As described in a Fiscal Note by the Fiscal Services Division of the Iowa Legislative Services Agency, the local earmarked levies have been phased out over two years, with counties permitted to levy an amount not exceeding $21.14 per capita in fiscal year 2022, which decreased to $0 in fiscal year 2023. Moving forward, the state will make appropriations to counties comparable with those that were generated by the tax (e.g., $42.00 per capita in fiscal year 2025). Given that the earmarked tax policies were no longer in effect at the time of our analysis (2021‐2022), we do not include Iowa counties in our quantitative analysis or legal mapping database.

Earmarked Recreational Cannabis Excise Tax Revenue

We identified states that mentioned mental health in the statutory language that permits the cultivation, sale, and possession of recreational cannabis. As of 2020, six states—Connecticut, Illinois, Montana, New York, Oregon, and Washington—mentioned mental health within the context of recreational cannabis excise tax revenue allocation requirements. 68 However, in all of these instances, the statutory language related to mental health was very ambiguous and appeared of secondary priority to spending on substance use services and prevention programs. For these reasons, it was not possible to precisely quantify the amount of revenue earmarked for mental health in these taxes. The most specific state earmark for mental health in recreational cannabis excise tax legislation was in Connecticut, which earmarked revenue for the epidemiologic surveillance and study of the impact of recreational cannabis on mental health (SB 1201, Sec. 146). Two local sales tax policies—Mendocino, California ($115.93 per capita, the second largest per capita rate identified) and Eagle Valley, Colorado ($11.72)—were earmarked for mental health.

Cell Phone Use Fees to Finance 988 and Mental Health Crisis Services

We identified five states—California Colorado, Nevada, Virginia, and Washington—that passed cell phone user fee legislation to finance mental crisis services. A unique feature of these fees, relative to the taxes identified in our study, is that they were adopted as a strategy to finance projected increases in service demand in direct response to a federal law—the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020 (Pub. Law 116–172), which designated “988” as the three digit dialing code for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline effective July 16, 2022. The 988 dialing code is projected to potentially triple Lifeline call volume, 69 and volume increased by approximately 45% in the weeks after the launch of the new dialing code. 70 The federal legislation that created the 988 dialing code, however, does not provide funding for the costs of increases in crisis service demand. 71 This funding responsibility falls to states, and the federal legislation explicitly authorizes—and in effect encourages—states to pass cell phone user fee legislation to meet increases in demand. 72 The user fee legislation adopted by the five states impose flat monthly fees that apply to every cell phone plan sold in the in the state. The initial fee amount ranges from $0.80 per month in California to $0.24 per month in Washington. At the time of the study, reliable revenue data (2021) were only available for Virginia ($0.42 per capita, $3,593,935 gross) and Washington ($0.58 per capita, $4,476,685 gross). 73

Discussion

This study provides the first systematic, national assessment of the prevalence and characteristics of earmarked taxes for mental health services in the United States. We find that a sizable portion of the US population (about 30%) lives in a jurisdiction that has an earmarked tax for mental health and that these taxes generate over $3.41 billion annually. Although we find that the number of jurisdictions with an earmarked tax for mental health has increased sharply over the past two decades, we also find that many jurisdictions had adopted earmarked taxes for mental health before the turn of the 21st century. For example, counties in Iowa had levied property taxes for mental health since the 1850s, counties in Illinois adopted property tax increases earmarked for mental health in 1963, Missouri passed authorizing legislation for these taxes in 1969, and local jurisdictions adopted these taxes through the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Overall, the study's results illustrate a movement of state and local tax increase, via ballot initiatives, to meet community mental health needs that are perceived as being unmet by the existing financing arrangements.

We find that the amount of revenue generated by earmarked taxes for mental health is relatively substantial in many jurisdictions. For example, per capita annual revenue exceeded $50 in 12 jurisdictions and $25 in 63 jurisdictions. To put these figures into context, the Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration's mental health spending in 2021 ($1.8 billion) equates to $5.38 per capita among US residents. 74 , 75 As such, the study signals that earmarked taxes at state and local levels are a meaningful, if not major, source of mental health financing in many jurisdictions. Thus, state and local earmarked taxes warrant more attention in mental health policy research.

There is tremendous opportunity to develop research in this area. With the exception of California's millionaire's tax 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 —which is unique in terms of its design and the amount of revenue it generates—virtually no research has assessed the impacts of earmarked taxes on mental health, clinical, or service outcomes. Studies have also generally not assessed policymaking or implementation processes related to these taxes or examined factors that could improve tax design or implementation outcomes. Questions pertaining to how earmarked tax revenue could fund implementation strategies to support the adaptation and delivery of evidence‐based mental health treatments have also not been explored, nor have questions related to the political dynamics of tax adoption—which are important given that most of the taxes identified were passed via ballot initiatives. Similar knowledge gaps exist in research about policies that earmark sugar sweetened beverage excise tax revenue 43 and in the field of health policy implementation research more broadly. 76 , 77 Future research should assess how variation in earmarked tax design, spending requirements and restrictions, implementation processes, and community contexts influence outcomes. Research is also needed to quantify the impacts of local mental health financing initiatives and how they interact with state and federal financing structures 78 because research to date has primarily focused on federal and state financing in isolation. The legal database of earmarked taxes for mental health created through this study (Appendix) can provide a foundation for future work in these areas.

It is worth considering the study's results within the context of devolution and health policy in the United States. 79 , 80 Devolution relates to the official transfer of power and responsibility for specific issues from higher (e.g., federal) to lower (e.g., state and local) levels of government. Although the passage of state and local earmarked taxes for mental health is not technically devolution because these taxes are adopted voluntarily, they can be perceived as a response to inadequate funding for mental health services from higher levels of government. Consistent with prior survey research, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 the results of our legal mapping study indicate that citizens are willing to increase taxes on themselves to enhance the fiscal ability of their state or local government to address community mental health needs.

Our findings related to state laws imposing cell phone user fees earmarked for mental health crisis services and 988 implementation are an example of this type of “soft” devolution in mental health financing. As noted above, the federal law that created 988 does not provide funding to cover the cost of increased demand for mental health crisis services—despite the intent of the law to increase demand for these services and indicators of meaningful increases in demand. 69 , 70 , 71 Instead, the statutory text (Sec. 4) encourages states to adopt earmarked user fee legislation to finance increases in service demand. Similar arguments related to devolution in mental health policy have been made in reference of the federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, for which enforcement responsibility falls to states without federal funding to support oversight activities. 81

Limitations

Our results should be considered within the context of the scope of the study and its limitations. First, our study was focused on earmarked taxes for mental health; we did not systemically search for taxes earmarked for substance use services. Many of the taxes identified in our study permitted, and in some cases required, the use of funds for substance use services. We did not seek to identify or include earmarked taxes exclusively focused on substance use, such as excise taxes on opioids earmarked for opioid use disorder treatment 82 or excise taxes on recreational cannabis for drug use prevention programs. 68 Revenue data also generally did not differentiate between that which will be allocated for mental health as opposed to substance use services.

Second, because of the inconsistency with which local policies, revenue data, and spending data are tracked across the United States, our data set is inherently incomplete. For example, we were unable to identify revenue data for 18 jurisdictions with an earmarked tax for mental health services (8.7% of those identified) and only identified the most recent effective year for renewable earmarked levies in Ohio. There are also detailed intricacies in tax spending requirements and implementation processes that we did not seek to catalog. Our study highlights the challenges of conducting legal mapping research at county and subcounty levels.

Third, it should be emphasized that our study was not designed to shed light on benefits or drawbacks of earmarked taxes for mental health services. Although we document revenue generation, our results do not provide indication of whether supplantation of other state or local funds has occurred because of the earmarked tax. As described in the protocol for the larger study, 83 we are conducting surveys and interviews with individuals involved with the implementation of earmarked taxes for mental health services to explore this and other issues.

Fourth, it should be emphasized that our study is cross‐sectional in nature—seeking to identify policies actively in effect at the time of analysis in 2021–2022—and does not provide a longitudinal data set that would capture variation in the presence/absence of earmarked taxes for mental health over time or changes in tax rates.

Conclusion

Policies earmarking taxes for mental health services are heterogenous in their design and are an increasingly common financing strategy in the United States, especially at the local level. The amount of revenue generated by these taxes is substantial in many jurisdictions. These taxes warrant greater attention in mental health policy and services research. Key areas for future research relate to understanding the determinants of tax policy proposal and passage, quantifying the impact of these taxes on clinical and service outcomes, identifying features of tax design that contribute to these outcomes, and characterizing how local earmarked taxes interact with state financing models and local service environments.

Supporting information

References

- 1. Frank RG, Glied SA. Better but Not Well: Mental Health Policy in the United States Since 1950. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alegría M, Frank RG, Hansen HB, Sharfstein JM, Shim RS, Tierney M. Transforming mental health and addiction services: commentary describes steps to improve outcomes for people with mental illness and addiction in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):226‐234. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dopp AR, Narcisse M‐R, Mundey P, et al. A scoping review of strategies for financing the implementation of evidence‐based practices in behavioral health systems: state of the literature and future directions. Implement Res Pract. 2020;1:2633489520939980. 10.1177/2633489520939980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grob GN. Government and mental health policy: a structural analysis. Milbank Q. 1994:471‐500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Purtle J, Nelson KL, Counts NZ, Yudell M. Population‐based approaches to mental health: history, strategies, and evidence. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:201. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eaton WW, Fallin MD. Public Mental Health. Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Realizing parity, reducing stigma, and raising awareness: increasing access to mental health and substance use disorder coverage. 2022 MHPAEA Report to Congress. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/laws‐and‐regulations/laws/mental‐health‐parity/report‐to‐congress‐2022‐realizing‐parity‐reducing‐stigma‐and‐raising‐awareness.pdf

- 8. Barry CL, Huskamp HA, Goldman HH. A political history of federal mental health and addiction insurance parity. Milbank Q. 2010;88(3):404‐433. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00605.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glickman A, Sisti DA. Medicaid's Institutions for Mental Diseases (IMD) Exclusion Rule: a policy debate—argument to repeal the IMD rule. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(1):7‐10. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176‐181. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martínez‐Alés G, Jiang T, Keyes KM, Gradus JL. The recent rise of suicide mortality in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;43:99‐116. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-051920-123206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Suicide Rates in the United States Continue to Increase. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. Trends in extreme distress in the United States, 1993–2019. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(10):1538‐1544. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goldman N, Glei DA, Weinstein M. Declining mental health among disadvantaged Americans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(28):7290‐7295. 10.1073/pnas.1722023115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daly M. Prevalence of psychological distress among working‐age adults in the United States, 1999–2018. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(7):1045‐1049. 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pescosolido BA, Halpern‐Manners A, Luo L, Perry B. Trends in public stigma of mental illness in the US, 1996–2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2140202. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Purtle J, Nelson KL, Bruns EJ, Hoagwood KE. Dissemination strategies to accelerate the policy impact of children's mental health services research. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(11):1170‐1178. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McGinty EE, Goldman HH, Pescosolido BA, Barry CL. Communicating about mental illness and violence: balancing stigma and increased support for services. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2018;43(2):185‐228. 10.1215/03616878-4303507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stone EM, McGinty EE. Public willingness to pay to improve services for individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(8):938‐941. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raising the next generation: a survey of parents and caregivers. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://everyfamilyforward.org/special‐reports/raising‐the‐next‐generation

- 21. Johnson FR, Gonzalez JM, JC YANG, Ozdemir S, Kymes S. Who would pay higher taxes for better mental health? Results of a large‐sample national choice experiment. Milbank Q. 2021;99(3):771‐793. 10.1111/1468-0009.12523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Purtle J, Dodson EA, Brownson RC. Uses of research evidence by state legislators who prioritize behavioral health issues. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(12):1355‐1361. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Purtle J, Lê‐Scherban F, Wang X, Shattuck PT, Proctor EK, Brownson RC. Audience segmentation to disseminate behavioral health evidence to legislators: an empirical clustering analysis. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):121. 10.1186/s13012-018-0816-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Purtle J, Henson RM, Carroll‐Scott A, Kolker J, Joshi R, Diez Roux AV. US mayors’ and health commissioners’ opinions about health disparities in their cities. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(5):634‐641. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Purtle J, Stadnick NA. Earmarked taxes as a policy strategy to increase funding for behavioral health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(1):100‐104. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilkinson M. Paying for public spending: is there a role for earmarked taxes? Fisc Stud. 1994;15(4):119‐135. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bös D. Earmarked taxation: welfare versus political support. J Public Econ. 2000;75(3):439‐462. 10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00075-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buchanan JM. The economics of earmarked taxes. J Polit Econ. 1963;71(5):457‐469. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wright A, Smith KE, Hellowell M. Policy lessons from health taxes: a systematic review of empirical studies. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):583. 10.1186/s12889-017-4497-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martin IW, Lopez JL, Olsen L. Policy design and the politics of city revenue: evidence from California municipal ballot measures. Urban Aff Rev. 2019;55(5):1312‐1338. 10.1177/1078087417752474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leland S, Chattopadhyay J, Maestas C, Piatak J. Policy venue preference and relative trust in government in federal systems. Governance (Oxf). 2021;34(2):373‐393. 10.1111/gove.12501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Public trust in government: 1958–2022. Pew Research Center. June 6, 2022. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2022/06/06/public‐trust‐in‐government‐1958‐2022/

- 33. Tahk SC. Public choice theory and earmarked taxes. Tax Law Rev. 2014;68:755. 10.2139/ssrn.2311372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organization . Health Taxes: A Primer for WHO Staff. World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dye RF, McGuire TJ. The effect of earmarked revenues on the level and composition of expenditures. Public Finance Rev. 1992;20(4):543‐556. 10.1177/109114219202000410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bell E, Wehde W, Stucky M. Supplement or supplant? Estimating the impact of state lottery earmarks on higher education funding. Educ Finance Policy. 2020;15(1):136‐163. 10.1162/edfp_a_00262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nguyen‐Hoang P. Volatile earmarked revenues and state highway expenditures in the United States. Transportation (Amst). 2015;42(2):237‐256. 10.1007/s11116-014-9534-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Crowley GR, Hoffer AJ. Earmarking tax revenues: leviathan's secret weapon? In: Hoffer AJ, Nesbit T, eds. For Your Own Good: Taxes, Paternalism, and Fiscal Discrimination in the Twenty‐First Century. Mercatus Center at George Mason University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chaloupka FJ, Powell LM, Warner KE. The use of excise taxes to reduce tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverage consumption. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):187‐201. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):172‐180. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Elder RW, Lawrence B, Ferguson A, et al.; Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(2):217‐229. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jayakumar KL, Lipoff JB. Tax collections and spending as a potential measure of health policy association with indoor tanning, 2011–2016. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):613‐614. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Forberger S, Reisch L, Meshkovska B, et al.; PEN Consortium. Sugar‐sweetened beverage tax implementation processes: results of a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(1):33. 10.1186/s12961-022-00832-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Purtle J, Langellier B, Lê‐Scherban F. A case study of the Philadelphia sugar‐sweetened beverage tax policymaking process: implications for policy development and advocacy. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(1):4‐8. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Purtle J, Brinson K, Stadnick NA. Earmarking excise taxes on recreational cannabis for investments in mental health: an underused financing strategy. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(4):e220292. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ramanathan T, Hulkower R, Holbrook J, Penn M. Legal epidemiology: the science of law. J Law Med Ethics. 2017;45(suppl 1):69‐72. 10.1177/1073110517703329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Burris S, Wagenaar AC, Swanson J, Ibrahim JK, Wood J, Mello MM. Making the case for laws that improve health: a framework for public health law research. Milbank Q. 2010;88(2):169‐210. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00595.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hendryx M. State mental health funding and mental health system performance. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2008;11(1):17‐25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Robinson RJ, Palka JM, Brown ES. The relationship between state mental health agency and Medicaid spending with outcomes. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(2):307‐314. 10.1007/s10597-020-00649-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burris S. A technical guide for policy surveillance. Temple University Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2014–34. 2014. 10.2139/ssrn.2469895 [DOI]

- 51. Hsieh H‐F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277‐1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) Allocation and Methodology for FiscalYear (FY) 2021–22. Department of Health Care Services. September 17, 2021. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/Documents/CSD_YV/BHIN/BHIN‐21‐057.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 53. Thom M. Can additional funding improve mental health outcomes? Evidence from a synthetic control analysis of California's millionaire tax. PLoS One. 2022;17(7):e0271063. 10.1371/journal.pone.0271063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Starks SL, Arns PG, Padwa H, et al. System transformation under the California Mental Health Services Act: implementation of full‐service partnerships in L.A. County. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(6):587‐595. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ashwood JS, Kataoka SH, Eberhart NK, et al. Evaluation of the Mental Health Services Act in Los Angeles County: implementation and outcomes for key programs. Rand Health Q. 2018;8(1):2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brookman‐Frazee L, Stadnick N, Roesch S, et al. Measuring sustainment of multiple practices fiscally mandated in children's mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43(6):1009‐1022. 10.1007/s10488-016-0731-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Collins RL, Wong EC, Breslau J, Burnam MA, Cefalu M, Roth E. Social marketing of mental health treatment: California's mental illness stigma reduction campaign. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S3):S228‐S235. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Varner C, Young C, Prohofsky A. Millionaire migration in California: administrative data for three waves of tax reform. Paper presented at: 111th Annual Conference on Taxation; November 15–17, 2018; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bruns EJ, Pullmann MD, Weathers ES, Wirschem ML, Murphy JK. Effects of a multidisciplinary family treatment drug court on child and family outcomes: results of a quasi‐experimental study. Child Maltreat. 2012;17(3):218‐230. 10.1177/1077559512454216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Martinez M, Hines L, Carlo G. Missouri's Tax for Children: An Investment That Counts. Family and Community Trust (FACT)—Missouri KIDS COUNT. March 2017. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://mokidscount.org/wp‐content/uploads/2017/03/Childrens‐Tax‐Fund‐Article_REV‐3‐15‐17.pdf

- 61. Barker A, Kempton L, Kemper L. Addressing local mental health need via county‐level property tax. Center for Health Economics and Policy, Institute for Public Health at Washington University. December 2021. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://cpb‐us‐w2.wpmucdn.com/sites.wustl.edu/dist/1/2391/files/2021/05/MO‐Mill‐Tax‐Brief_December‐2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 62. History . INC Mental Health Alliance. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.incmha.org/history/

- 63. 2017–2018 mental health ballot measures in Colorado counties. Mental Health Colorado. 2021. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.mentalhealthcolorado.org/wp‐content/uploads/2021/01/Denver‐Foundation‐Report.pdf

- 64. Behavioral Health Handbook. Ohio Association of County Behavioral Health Authorities. January 2016. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://ohioauditor.gov/publications/docs/BH%20Handbook%20January%202016.pdf

- 65. 2020 Levy Fact Book Presented to the Franklin County Board of Commissioners and the Human Services Levy Review Committee. Alcohol Drug and Mental Health Board of Franklin County. 2020. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://budget.franklincountyohio.gov/OMB‐website/media/Documents/Human%20Services%20Levy%20Review%20Committee/Alcohol,%20Drug%20and%20Mental%20Health%20Board/2020‐ADAMH‐Levy‐Fact‐Book.pdf

- 66. Curry S. Removing the mental health tax burden from Iowa Counties: did counties pass on the property tax savings? ITR Foundation. September 2022. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://itrfoundation.org/wp‐content/uploads/2022/09/Removing‐the‐Mental‐Health‐Tax‐Burden‐From‐Iowa‐Counties.pdf

- 67. Issue review: adult mental health and disability services system funding history. Iowa Department of Human Services. February 1, 2019. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/publications/IR/970935.pdf

- 68. Cannabis taxes. Urban Institute. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.urban.org/policy‐centers/cross‐center‐initiatives/state‐and‐local‐finance‐initiative/state‐and‐local‐backgrounders/marijuana‐taxes

- 69. 988 Appropriations report. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. December 2021. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/988‐appropriations‐report.pdf?mkt_tok=NzczLU1KRi0zNzkAAAGB‐R05HteqsRrupuzcoWkQfjYOLAn9DLIwUQXMMGJpt0yjTdMqP4oj2IrHkwDFVhAaTpTu8H‐6MyAzF22_gWEASOKCOzB_ANvHtxTR2mhE5Q

- 70. 988 Lifeline performance metrics. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/find‐help/988/performance‐metrics

- 71. Purtle J, Ortego JC, Bandara S, Goldstein A, Pantalone J, Goldman M. Implementation of the 988 suicide and crisis lifeline at the state‐level: estimating costs of increased call demand at lifeline centers and quantifying state financing. J Ment Health Policy Econ. Forthcoming 2023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Stephenson AH. States’ experiences in legislating 988 and crisis services systems. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. 2022. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/2022_nasmhpd_StatesLegislating988_022922_1753.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 73. 988 Fee accountability report—National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020. Wireline Competition Bureau. October 26, 2022. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.fcc.gov/document/988‐fee‐accountability‐report

- 74. Fiscal year 2023 budget. Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/samhsa‐fy‐2023‐cj.pdf

- 75. New vintage 2021 population estimates available for the Nation, States and Puerto Rico. United States Census Bureau. December 21, 2021. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press‐releases/2021/2021‐population‐estimates.html

- 76. McGinty EE, Seewald NJ, Bandara S, et al. Scaling interventions to manage chronic disease: innovative methods at the intersection of health policy research and implementation science. Prev Sci. Forthcoming 2023. 10.1007/s11121-022-01427-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Allen P, Pilar M, Walsh‐Bailey C, et al. Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):47. 10.1186/s13012-020-01007-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. As Schnake‐Mahl, JL Jahn, Purtle J, Bilal U. Considering multiple governance levels in the epidemiological analysis of public policies. Soc Sci Med. 2022;314:115444. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Anton TJ. New federalism and intergovernmental fiscal relationships: the implications for health policy. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1997;22(3):691‐720. 10.1215/03616878-22-3-691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sparer MS, France G, Clinton C. Inching toward incrementalism: federalism, devolution, and health policy in the United States and the United Kingdom. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2011;36(1):33‐57. 10.1215/03616878-1191099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. El‐Sabawi T. MHPAEA & marble cake: parity & the forgotten frame of federalism. Dick Law Rev. 2019;124(3):591. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Harris RA, Mandell DS, Gross R. A national opioid tax for treatment programs in the US: funding opportunity but problems ahead. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(1):e214316. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Purtle J, Stadnick NA, Wynecoop M, Bruns EJ, Crane ME, Aarons G. A policy implementation study of earmarked taxes for mental health services: study protocol. Implement Sci Commun. Forthcoming 2023. 10.1186/s43058-023-00408-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials