Abstract

The results of the Phase III DESTINY-Breast04 trial of trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) are leading to a shift in both the classification and treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative metastatic breast cancer. In this trial, T-DXd was associated with a substantial survival benefit among patients with hormone receptor-positive and hormone receptor-negative disease and low expression of HER2, a biomarker previously considered unactionable in this treatment setting. Herein, we discuss the evolving therapeutic pathway for HER2-low disease, ongoing clinical trials, and the potential challenges and evidence gaps arising with treatment of this patient population.

Keywords: chemotherapy, HER2-low, HER2-targeted therapy, metastatic breast cancer, sacituzumab govitecan, trastuzumab deruxtecan, treatment sequencing

Introduction

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In 2020, an estimated 2.26 million women were diagnosed with the disease and 685,000 related deaths occurred globally. 1 Although more than 80% of breast cancer cases are early stage at diagnosis, approximately 5% present with incurable metastatic breast cancer (mBC) 2 ; even after completion of curative-intent treatment, 15–24% of patients ultimately develop mBC. 3 These patients have a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival ranging 22–29% and median overall survival (mOS) ranging from 8 months to 5 years, depending on patient and disease characteristics and therapeutic intervention.4–9

Overexpression and/or gene amplification of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is observed in approximately 15–20% of human breast cancers, which are categorized as HER2-positive disease.3,10,11 Although several targeted therapies have shown favorable efficacy in the HER2-positive setting of mBC, options have remained more limited for patients conventionally categorized as HER2-negative. However, the treatment paradigm for management of HER2-negative mBC is poised to transform in light of results from the Phase III trial DESTINY-Breast04. 12 In this study, treatment with the HER2-targeted antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) was associated with a clinically meaningful survival benefit in an mBC population with a biomarker not previously thought to be actionable: HER2-low. 12 This manuscript describes the evolving treatment pathway for patients with HER2-low mBC, as well as clinical trials and anticipated challenges for this population.

Conventional HER2 classification and use of targeted therapies

Classification of the HER2 biomarker

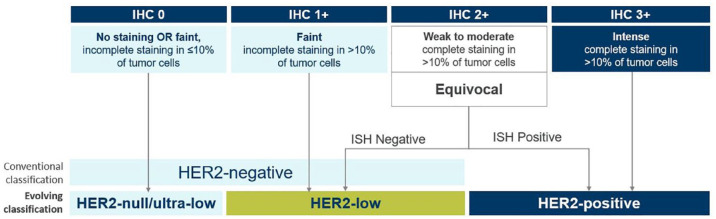

Evaluation of the expression of three key biomarkers – estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and HER2 – has been adopted to understand prognosis and individualize treatment options for patients with breast cancer.13–16 Assessment of HER2 status is recommended both at diagnosis and upon development of metastatic disease.14,16 Historically, classification of HER2 expression has been binary (Figure 1): HER2-positive disease was defined as the presence of tumors with an immunohistochemistry (IHC) score of 3+ or 2+ with HER2 gene (ERBB2) amplification by in situ hybridization (ISH) assay, 16 while tumors with IHC scores of 0+, 1+, or 2+/ISH-negative were defined as HER2-negative. Recent evidence, however, indicates that patients with low HER2 expression (IHC 1+ or 2+/ISH-negative) represent a new targetable category of breast cancer termed ‘HER2-low’ (Figure 1), a population with a heterogenous presentation and variable prognosis.17–19 Approximately half of all breast cancer cases are HER2-low,10,17,18 including approximately two-thirds of hormone receptor (HR)-positive patients and about 40% of those with HR-negative disease. 20 Although informally defined and more challenging to identify, another HER2 classification, ultra-low (e.g., IHC > 0 <1+), is also under investigation to understand whether patients with undetectable HER2 expression respond to HER2-targeted therapy. 21

Figure 1.

Evolving classification of mBC according to HER2 status.

HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ISH, in situ hybridization; mBC, metastatic breast cancer.

Efficacy of HER2-targeted therapies

HER2-targeted therapies used in the treatment of HER2-positive mBC include the monoclonal antibodies trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and margetuximab; the ADCs, trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and T-DXd; and the HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitors, tucatinib, lapatinib, and neratinib.13,14 The introduction of these agents has dramatically improved clinical outcomes in HER2-positive mBC: in the first-line (1L) setting, mOS increased from approximately 20 months with standard chemotherapy to 50 months with combination chemotherapy with pertuzumab and trastuzumab.22,23 However, clinical evaluations of trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and T-DM1 in HER2-low populations did not show meaningful benefits.24–30 As a result, until recently, patients with HER2-low disease remained categorized as HER2-negative for treatment decision-making18,31 and conventionally received therapy on the basis of HR expression and the presence of other drug-targeting biomarkers. 17

HER2-low: An actionable target

Activity of T-DXd

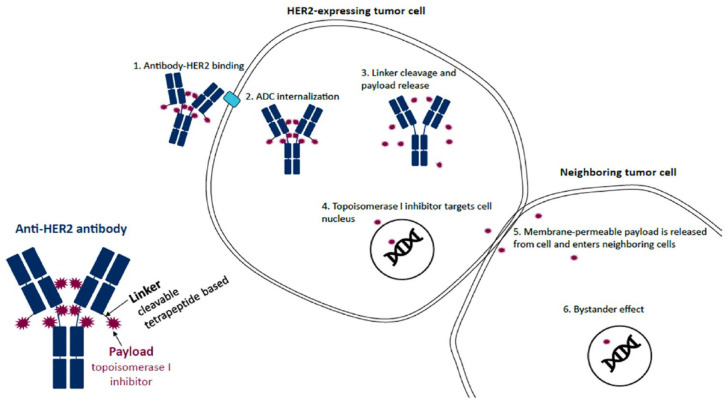

Although HER2 overexpression (i.e., IHC 3+ or IHC 2+/ISH positive) was long considered mandatory for the efficacy of HER2-targeted therapies, new evidence indicates this is no longer the case for novel and more potent agents such as T-DXd. This ADC therapy consists of a humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody (trastuzumab) joined to a membrane-permeable payload topoisomerase I inhibitor (DX-895) via a cleavable linker. Once bound to HER2 protein, T-DXd delivers its cytotoxic payload (8:1 drug-to-antibody ratio) to both the target cell and neighboring cells via a unique bystander effect, regardless of level of HER2 expression (Figure 2).32,33 This effect is thought to differentiate T-DXd from other HER2-targeted therapies such as T-DM1.32,33

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of T-DXd.

Source: Figure 1 from Swain et al. 34 Creative Commons license and disclaimer available from https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

ADC, antibody–drug conjugate; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; T-DXd, trastuzumab deruxtecan.

The impressive efficacy of T-DXd among patients with heavily pretreated, HER2-positive mBC in the single-arm, Phase II DESTINY-Breast01 trial was subsequently confirmed in the Phase III trial DESTINY-Breast02, which showed superiority of T-DXd over conventional HER2-targeted and chemotherapy-based regimens among patients previously treated with T-DM1.35,36 Another Phase III trial, DESTINY-Breast03, showed significantly improved survival outcomes with T-DXd versus T-DM1 in a less pretreated population, underscoring the clinical benefits of technological advances in ADC engineering. 37 Simultaneously, efforts were made to evaluate T-DXd in other HER2 populations, such as HER2-low mBC.38–40

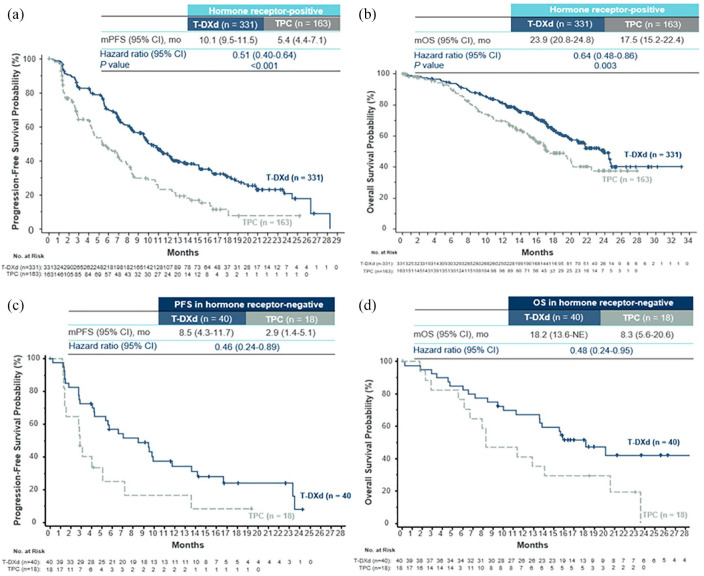

Efficacy of T-DXd in HER2-low mBC: DESTINY-Breast04

Initial evaluations of T-DXd in Phase Ib and II studies showed promising outcomes among heavily pretreated patients with HER2-low mBC.38–40 Across these investigations, overall response rates ranged 33–38% and median progression-free survival (mPFS) ranged 6.3–11.1 months (Table 1).38–40 These findings supported the design of the Phase III DESTINY-Breast04 trial of patients with HER2-low mBC. 12 This study included a total of 557 patients (HR-positive or HR-negative) who had received chemotherapy for mBC or had disease recurrence during or within 6 months of completion of adjuvant chemotherapy; HR-positive patients had to have received ⩾1 line of endocrine therapy (ET). Patients were randomized 2:1 to T-DXd or physician’s choice chemotherapy (capecitabine, gemcitabine, eribulin, paclitaxel, or nab-paclitaxel). 12 The primary endpoint was PFS in the HR-positive subgroup; key secondary endpoints included PFS (all patients) and OS (HR-positive and all patients). In the overall population, patients had received a median of three prior lines of therapy in the metastatic setting and 88.7% had HR-positive disease; 57.6% had IHC 1+; and 42.4% had IHC 2+/ISH-negative disease. The median duration of follow-up was 18.4 months. In the HR-positive subgroup, the confirmed objective response rate (cORR) was substantially higher with T-DXd than with physician’s choice chemotherapy (52.6% versus 16.3%, respectively). Furthermore, median PFS was nearly doubled with T-DXd (10.1 months versus 5.4 months; hazard ratio: 0.51 [95% CI: 0.40–0.64]; p < 0.001) and mOS was significantly prolonged (23.9 months versus 17.5 months; hazard ratio: 0.64 [95% CI: 0.48–0.86]; p = 0.003) (Figure 3; Table 1). Results for treatment response and survival were generally comparable in the full patient population and in an exploratory analysis of patients with HR-negative disease. In the HR-negative cohort (n = 58), cORR was 50% with T-DXd versus 16.7% with physician’s choice chemotherapy. mPFS was also improved with T-DXd (8.5 months versus 2.9 months; hazard ratio: 0.46 [95% CI: 0.24–0.89]), as was mOS (18.2 months versus 8.3 months; hazard ratio: 0.48 [95% CI: 0.24–0.95]). Among all patients, the most common drug-related adverse events (AEs; any grade) associated with T-DXd included nausea (73.0%), fatigue (47.7%), and alopecia (37.7%). The overall rate of grade 3+ AEs was lower with T-DXd than with physician’s choice therapy (52.6% versus 67.4%). Drug-related interstitial lung disease (ILD) or pneumonitis was observed in 45 (12.1%) T-DXd-treated patients compared with 1 (0.6%) patient who received physician’s choice chemotherapy. Although the majority of these events were mild or moderate (12 [3.5%] grade 1; 24 [6.5%] grade 2) in the T-DXd group, grade 5 toxicity was observed in three patients (0.8%). Collectively, the results of DESTINY-Breast04 and the earlier Phase Ib and II trials emphasized that, in contrast to previous thinking, low expression of HER2 is in fact an actionable target in mBC.

Table 1.

Completed and ongoing clinical trials of T-DXd and other therapies in HER2-low advanced/mBC.

| Intervention | Study name, design, NCT number | Phase | Patient population | N | Trial status a | Key results (or estimated primary completion date) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADC: monotherapy and combination therapy | ||||||

| T-DXd versus physician’s choice CTX | DESTINY-Breast0412 (randomized, multicenter, two-group, open-label) | III | HER2-low mBC | 557 (89% HR+, 11% HR−) | Active, not recruiting | T-DXd versus physician’s choice chemotherapy: |

| NCT03734029 | after 1–2 standard therapies | HR+ patients, | ||||

| cORR: 52.6% versus 16.3% | ||||||

| mPFS: 10.1 versus 5.4 mo | ||||||

| mOS: 23.9 versus 17.5 mo | ||||||

| HR− patients, | ||||||

| cORR: 50.0% versus 16.7% | ||||||

| mPFS: 8.5 versus 2.9 mo | ||||||

| mOS: 18.2 versus 8.3 mo | ||||||

| Full population, | ||||||

| ILD: 12.1% versus 0.6% | ||||||

| T-DXd | DEBBRAH41–44 (multicenter, open-label, two-stage) | II | Pretreated HER2+/HER2-low unresectable locally advanced or mBC with untreated BMs or LMC (5 cohorts) | 41 | Completed | ORR-IC b : |

| NCT04420598 | Cohort 2 (HER2± low): 66.7% | |||||

| Cohort 4 (HER2-low): 33.3% | ||||||

| PFS (both cohorts): 5.7 mo | ||||||

| T-DXd | DAISY 39 (open-label) | II | HER2+, HER2-low, and HER2-null advanced BC | 176 (FAS) (72 HER2-low) | Active, not recruiting | HER2-low (HER2-null): |

| NCT04132960 | BOR: 33.3% (30.6%) | |||||

| mPFS: 6.7 mo (4.2 mo) | ||||||

| ILD: n = 4 (full population) | ||||||

| T-DXd | Dose-expansion study 38 | Ib | HER2-low advanced/mBC refractory to standard therapies | 54 (87% HR+, 13% HR−) | Active, not recruiting | cORR: 37.0% |

| NCT02564900 | mPFS: 11.1 mo | |||||

| mOS: 29.4 mo | ||||||

| ILD: 14.8% | ||||||

| T-DXd + nivolumab | Two-part, open-label study 40 | Ib | HER2-expressing mBC after standard therapy | Part 2: 45 (16 HER2-low; 13 HR+) | Active, not recruiting | HER2-low: |

| NCT03523572 | ORR: 37.5% | |||||

| mPFS: 6.3 mo | ||||||

| ILD: 10.4% (full population) | ||||||

| T-DXd + durvalumab (+ others) | BEGONIA 45 (Two-part, multicenter, multi-arm, open-label) | Ib/2 | Untreated, unresectable, locally advanced/metastatic HER2-low TNBC (IHC 0 excluded) breast cancer | Arm 6 (Durvalumab + T-DXd): 11 | Active, not recruiting | cORR: 100% (4/4; only four pts have completed two on-treatment assessments; remaining seven pts still on treatment) |

| NCT03742102 | ILD: NR | |||||

| T-DXd versus physician’s choice CTX | DESTINY-Breast0621 (randomized, multicenter, open-label) | III | HR+, HER2-low (IHC 2+/ISH-, IHC 1+, and IHC > 0 <1+) mBC progressed on ⩾2 lines of ET | 850 (est.) | Recruiting | July 2023 |

| NCT04494425 | ||||||

| T-DXd combinations c | DESTINY-Breast0846–48 (multicenter, open-label, modular, two-part) | Ib | HR+ and HR−, HER2-low advanced or mBC (Part 2: 5 cohorts) | 182 (est.) | Active, not recruiting | Preliminary results, modules 4 and 5, |

| NCT04556773 | Recommended doses for expansion: | |||||

| T-DXd (5.4 mg/kg) Q3W + | ||||||

| anastrozole (1 mg QD) or | ||||||

| fulvestrant (500 mg Q4W d ) | ||||||

| No DLTs reported, both combinations generally well tolerated | ||||||

| T-DXd + pembrolizumab | Two-part, open-label study 49 | I | HER2-low, advanced/mBC with failure on prior standard therapy | 105 | Recruiting | 2023 |

| NCT04042701 | ||||||

| T-DM1 | Single-arm study 25 | II | HER2+ mBC with progression after prior HER2 treatment and previous CTX | 112 e | Completed | Analysis of confirmed |

| NCT00509769 | HER2+ versus HER2-normal, | |||||

| ORR: 33.8% versus 4.8% | ||||||

| mPFS: 8.2 mo versus 2.6 mo | ||||||

| ILD: NR | ||||||

| T-DM1 | Single-arm study 30 | II | HER2+ mBC previously treated with trastuzumab, lapatinib, an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine | 110 f | Unknown | Analysis of confirmed |

| NCT: N/A | HER2+ versus HER2-normal, | |||||

| ORR: 41.3% versus 20.0% | ||||||

| mPFS: 7.3 mo versus 2.8 mo | ||||||

| ILD: 1 related death (full population) | ||||||

| Sacituzumab govitecan versus physician’s choice CTX | ASCENT50,51 | III | TNBC (local advanced or mBC) RR to ⩾2 previous CTX regimens | 468 (post hoc analysis: HER2-low: 123, IHC 0: 293) | Completed | SG versus physician’s choice (post hoc analyses): |

| NCT02574455 | HER2-low patients, | |||||

| ORR: 32% versus 8% | ||||||

| mPFS: 6.2 versus 2.9 mo | ||||||

| mOS: 14.0 versus 8.7 mo | ||||||

| IHC 0 patients, | ||||||

| ORR: 31% versus 3% | ||||||

| mPFS: 4.3 versus 1.6 mo | ||||||

| mOS: 11.3 versus 5.9 mo | ||||||

| ILD: n = 1 (SG group; full population) | ||||||

| Sacituzumab govitecan versus physician’s choice CTX | TROPiCS-0252,53 | III | HR+, HER2-advanced BC, heavily pretreated, ET-resistant | 543 (post hoc analysis: HER2-low: 283, IHC 0: 217) | Active, not recruiting | SG versus physician’s choice: |

| NCT03901339 | HER2-low patients, | |||||

| ORR: 26% versus 12% | ||||||

| mPFS: 6.4 versus 4.2 mo | ||||||

| IHC 0 patients, | ||||||

| ORR: 16% versus 15% | ||||||

| mPFS: 5.0 versus 3.4 mo | ||||||

| ILD: 0% versus 1% (full population) | ||||||

| MRG002 | Multicenter, open-label study 54 | II | HER2-low locally advanced or mBC | 66 (est.) | Recruiting | February 2023 |

| NCT04742153 | ||||||

| Disitamab vedotin (RC48) versus physician’s choice | Randomized, parallel-control, multicenter study 55 | III | HER2-low mBC, previous use of anthracyclines, and 1–2 systemic CTX regimens | 366 (est.) | Recruiting | December 2022 |

| NCT04400695 | ||||||

| Disitamab vedotin (RC48) | Open-label study 56 | II | HER2+ and HER2-low mBC with abnormal PAM pathway activation | 64 (est.) | Recruiting | December 2023 |

| NCT05331326 | ||||||

| Disitamab vedotin (RC48) + penpulimab | Open-label study 57 | II | Neoadjuvant treatment of HER2-low early or locally advanced breast cancer | 20 (est.) | Not yet recruiting | August 2024 |

| NCT05726175 | ||||||

| Monoclonal antibodies | ||||||

| Trastuzumab + CTX versus CTX | NSABP B-4724 randomized) | III | High-risk primary invasive BC, HER2 IHC 1+ or 2+/FISH < 2.0 | 3270 | Active, not recruiting | 5-year event rates, trastuzumab/CTX versus CTX: |

| NCT01275677 | IDFS: 89.8% versus 89.2% | |||||

| DRFI: 92.7% versus 93.6% | ||||||

| OS: 94.8% versus 96.3% | ||||||

| ILD: NR | ||||||

| Margetuximab | Single-arm, open-label study58,59 | II | R/R advanced BC with IHC 1+ or 2+ without gene amplification | 25 | Completed | Results not yet reported |

| NCT01828021 | ||||||

| Bispecific and trispecific antibodies | ||||||

| Zenocutuzumab combinations | Open-label study 60 | II | HR+, HER2-low mBC refractory to ET/CDK4/6i | 42 (evaluable for efficacy) | Active, not recruiting | DCR: 45% |

| NCT03321981 | ILD: NR | |||||

| Various | ||||||

| Drug selection based on genome signature/ drug sensitivity of PDO model g | Open-label, parallel assignment study 61 | III | Refractory HER2+ (including low) mBC resistant to trastuzumab | 120 (est.) | Recruiting | February 2024 |

| NCT05429684 | ||||||

Other than studies of T-DXd, only Phase II and III trials are presented; numerous additional phase I and I/II trials are ongoing.

Status accurate as of 20 April 2023.

Cohort 2 includes HER2+/HER2-low mBC patients with asymptomatic, untreated BMs (current data reflect all HER2-low patients). Cohort 4 includes HER2-low mBC patients with progressive BMs after local treatment and had a higher proportion of HR-negative patients than Cohort 2. PFS data remain immature.

T-DXd used in combination with durvalumab + paclitaxel, capivasertib, anastrozole, fulvestrant, or capecitabine.

Fulvestrant loading dose: 500 mg on C1D15.

95 efficacy-evaluable patients had HER2 status reassessed: 74 were confirmed HER2+ and 21 were classified as HER2-normal.

95 patients had HER2 status reassessed: 80 were confirmed HER2+ and 15 were classified as HER2-normal.

HER2-low patients will receive trastuzumab + pertuzumab + paclitaxel.

ADC, antibody–drug conjugate; BC, breast cancer; BM, brain metastases; BOR, best overall response; CDK4/6, cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6; CI, confidence interval; cORR, confirmed objective (or overall) response rate; CTX, chemotherapy; DCR, disease control rate; DLT, dose-limiting toxicities; DRFI, distant recurrence-free interval; est., estimated; FAS, full analysis set; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; GEJ, gastroesophageal; HER2, human epidermal growth factor 2; HR, hormone receptor; IDFS, invasive disease-free survival; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ILD, interstitial lung disease (or pneumonitis); LMC, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis; mBC, metastatic breast cancer; mo, months; mOS, median overall survival; mPFS, median progression-free survival; N/A, not available; NR, not reported; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; ORR(-IC), overall response rate (intracranial); PDO, patient-derived organoids; pts, patients; Q3/4W, every 3/4 weeks; QD, every day; R/R, relapsed or refractory; SG, sacituzumab govitecan; T-DM1, trastuzumab emtansine; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; PAM, PI3K/Akt/mTOR.

Figure 3.

DESTINY-Breast04: Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival outcomes associated with T-DXd versus physician’s choice chemotherapy among patients with HR-positive (a, b) and HR-negative (c, d) HER2-low mBC.

Source: Figures compiled from Modi et al. 62 Permission for use granted by the authors.

CI, confidence interval; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; mBC, metastatic breast cancer; mo, months; NE, not estimable; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; T-DXd, trastuzumab deruxtecan; TPC, physician’s choice chemotherapy.

Impact of DESTINY-Breast04 on treatment of HER2-low mBC

The results of DESTINY-Breast04 mark a new era in the management of mBC, with the reinterpretation of low HER2 status as a targetable disease entity. The trial’s results indicate that T-DXd is an important treatment option that should be incorporated into standard of care therapy for patients with HER2-low mBC.

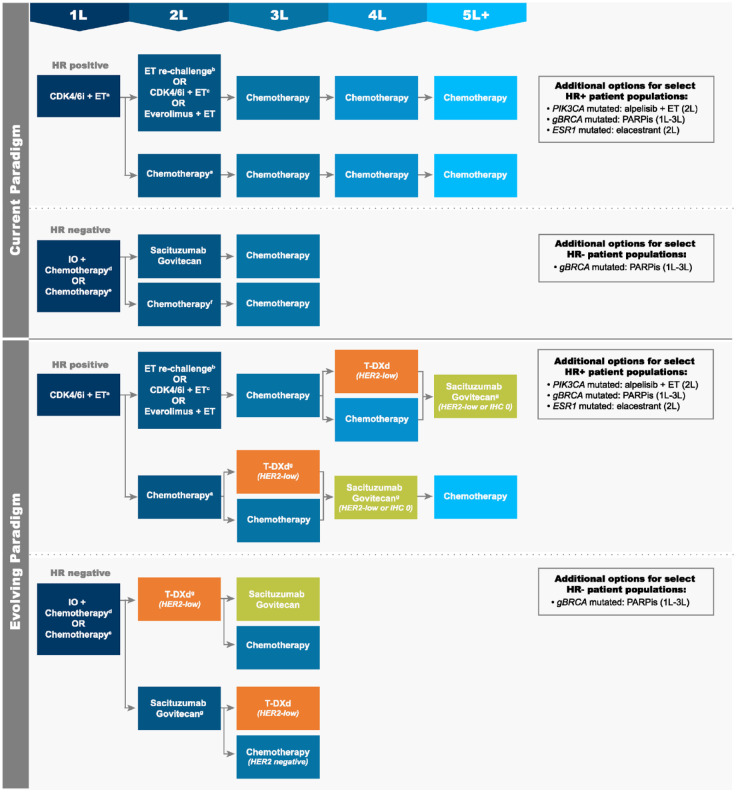

Current treatment paradigm

The current treatment paradigm for HER2-negative (IHC 0, 1+, or 2+/ISH-negative) mBC varies on the basis of HR status (Figure 4). Among patients with HR-positive disease, therapy typically includes the following sequence of agents13,15,16: 1L, ET + cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i) (or chemotherapy among patients with imminent organ failure); second-line (2L), ET rechallenge (monotherapy), ET + CDK4/6i (if not received 1L), ET + everolimus, or chemotherapy; third-line (3L) to fifth-line (5L) chemotherapy. Select patient populations may be eligible for additional treatment options, such as 2L alpelisib + fulvestrant if tumors harbor a PIK3CA mutation, 63 2L elacestrant for ESR1 mutations, 64 or an oral poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase inhibitor (PARPi) in the 1L to 3L if a germline BRCA mutation (gBRCAm) exists. 65 Phase II data are also available for use of PARPi in somatic BRCA mutations. 66 Patients with HR-negative disease have even fewer treatment options: 1L, immunotherapy + chemotherapy (if programmed death-ligand 1 [PD-L1] positive) or chemotherapy; 2L, sacituzumab govitecan (SG) or chemotherapy; 3L, chemotherapy. In each line, treatment selection is dependent on individual patient characteristics, previously received therapies, and reimbursement/access restrictions. Importantly, the number of effective treatment options becomes increasingly limited in later lines of therapy, and response rates and survival impact diminish with each subsequent line.67,68 Patients who progress to late-line, single-agent chemotherapy have an mPFS of only 2–5 months.69–71 As such, these individuals have a substantial need for new, targeted therapeutics that can safely improve clinical outcomes.

Figure 4.

Current and evolving treatment paradigms for HER2-negative mBC, including HER2-low disease. (a) Chemotherapy to be used among patients with imminent organ failure. (b) Rechallenge with ET monotherapy. (c) Option if not received in 1L. (d) Option for PD-L1-positive patients. (e) PARPi preferred over chemotherapy for appropriate patients. (f) SG preferred over chemotherapy. (g) Optimal sequencing of T-DXd and SG in HER2-low disease has yet to be determined.

Standard chemotherapies (2L and beyond) may include taxanes, platinum agents, capecitabine, gemcitabine, anthracyclines, eribulin, and vinorelbine. Patients receiving 1L or 2L CDK4/6i therapy may not be eligible for funding of subsequent therapy with everolimus + exemestane, alpelisib + fulvestrant, single-agent fulvestrant or elacestrant, or PARPi in some countries (e.g., Canada).

1L/2L/3L/4L/5L, first/second/third/four/fifth line of therapy; CDK4/6i, cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor; ET, endocrine therapy; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; IO, immunotherapy; mBC, metastatic breast cancer; PARPi, poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase inhibitor; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; SG, sacituzumab govitecan; T-DXd, trastuzumab deruxtecan.

Evolving treatment paradigm

In DESTINY-Breast04, most patients were classified as having hormone-refractory mBC, as the majority had HR-positive disease and had received ⩾3 prior lines of systemic therapy (including hormone therapy) in the metastatic setting. 12 Approximately 60% of patients had received one prior line of chemotherapy and 40% had received two. Therefore, initial use of T-DXd in the HER2-low population will likely focus on the fourth or later line of mBC therapy (Figure 4). However, as observed in the HER2-positive treatment setting, it is anticipated that treatment with T-DXd will also be beneficial in earlier lines. The Phase III trial DESTINY-Breast06 is currently evaluating T-DXd versus investigator’s choice chemotherapy in HR-positive HER2-low and ultra-low mBC after progression on CDK4/6 + ET within 6 months or two prior lines of ET ± targeted therapy in the metastatic setting (Table 1). 21

In post hoc analyses, the TROP2-targeted ADC SG also recently showed efficacy in HER2-low mBC within clinical trials of conventionally defined HER2-negative disease (0+, 1+, or 2+/ISH-negative). The Phase III TROPiCS-02 trial (NCT03901339) included heavily pretreated patients with HR-positive, ET-resistant, locally recurrent inoperable or mBC (N = 543) who had previously received a CDK4/6i and 2–4 lines of chemotherapy; SG was compared to physician’s choice chemotherapy.52,72 Most study patients had visceral metastases (95%) and prior treatment with a CDK4/6i (99%); the median number of prior lines of chemotherapy was three. The trial’s primary endpoint was PFS, and secondary endpoints included OS and ORR. In the full study population at a median follow-up of 10.2 months, mPFS was 5.5 months with SG and 4.0 months with physician’s choice chemotherapy (hazard ratio: 0.66 [95% CI: 0.53–0.83]; p = 0.0003). 52 At 12.5 months of follow-up, mOS was 14.4 and 11.2 months, respectively, in these groups (hazard ratio: 0.79 [95% CI: 0.65–0.96]; p = 0.02). 71 Objective response rates were 21% and 14% with SG and physician’s choice, respectively. In a post hoc analysis of outcomes among patients with HER2-low disease (n = 283) and those with IHC 0 (n = 217), 53 the clinical benefit of SG was consistent with that in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population (Table 1). The ORR was 26% with SG versus 12% with chemotherapy among HER2-low patients (IHC 0 cohort: 16% versus 15%), and mPFS was 6.4 months versus 4.2 months, respectively (hazard ratio: 0.58 [95% CI: 0.42–0.79]; p < 0.001) (IHC 0 cohort: 5.0 months versus 3.4 months; hazard ratio: 0.72 [95% CI: 0.51–1.00]; p = 0.05). In the overall study population, the most common drug-related AEs associated with SG included neutropenia (70%), diarrhea (57%), nausea (55%), alopecia (46%), and fatigue (37%). No cases of ILD were observed in the SG group (1% with chemotherapy).

Notably, SG is already approved for use among patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who relapse after or are refractory to ⩾2 prior chemotherapy regimens, including therapy in the adjuvant setting. Approval was based on the landmark Phase III ASCENT trial (NCT02574455), which compared SG (n = 235) to physician’s choice chemotherapy (eribulin, vinorelbine, capecitabine, or gemcitabine; n = 233). 50 At a median follow-up of 17.7 months, mPFS was 4.8 months with SG versus 1.7 months with chemotherapy (hazard ratio: 0.43 [95% CI: 0.35–0.54]) in the full study population (with or without brain metastases), and mOS was 11.8 months versus 6.9 months, respectively (hazard ratio: 0.51 [95% CI: 0.41–0.62]) (both secondary endpoints). Objective response rates were 31% with SG and 4% with chemotherapy. In a post hoc analysis of this trial, similar clinical efficacy of SG was observed in HER2-low and IHC 0 subgroups compared with the ITT population (HER2-low, SG versus chemotherapy: PFS, hazard ratio: 0.44 [95% CI: 0.27–0.72]; p = 0.002; OS, hazard ratio: 0.43 [95% CI: 0.28–0.67]; p < 0.001]; ORRs: 32% versus 8%) (Table 1). 51 The safety profile of SG was similar to that reported in TROPiCS-02. Considering these findings from the post hoc analyses of ASCENT and TROPiCS-02, SG is another important option for patients with HER2-low disease (Figure 4). As discussed below, optimal sequencing of T-DXd and SG remains to be determined.

Ongoing studies in HER2-low

Numerous other studies are assessing targeted therapies in HER2-low advanced and mBC populations, either as single-agent or combination treatments (e.g., with other ADCs, immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and/or endocrine therapy). Table 1 summarizes completed and ongoing trials of T-DXd and other relevant Phase II and III studies in HER2-low. For example, DESTINY-Breast08 is an open-label, Phase Ib study of the safety, tolerability, and recommended expansion dose for T-DXd used in combination with either capecitabine, durvalumab and paclitaxel, capivasertib, anastrozole, or fulvestrant.46,47 The trial includes five HER2-low patient cohorts, which vary on the basis of HR expression and previously received therapy. Preliminary findings indicate that T-DXd can be used safely in combination with anastrozole or fulvestrant; additional results are expected in late 2023. 46 Another open-label study, the Phase II, five-cohort DEBBRAH trial, is evaluating T-DXd among patients with HER2-positive or HER2-low advanced breast cancer with central nervous system involvement.41–44 Data are available for two cohorts that included HER2-low patients: in Cohort 2 (HER2-positive/low mBC with asymptomatic, untreated brain metastases), intracranial overall response rate was 67%; in Cohort 4 (HER2-low mBC with progressing brain metastases after treatment), this outcome was 33% (Table 1). 42 PFS was 5.7 months in these groups combined, although the data are still maturing. The Phase II, open-label DAISY study is also evaluating T-DXd in HER2-positive, HER2-low, and null populations; in the latter two groups, best overall response rates ranged 31–33% and mPFS was 4.2–6.7 months. 39 Evaluation of T-DXd is also underway in Phase I trials of combination immunotherapy with nivolumab 40 and durvalumab 45 (results available; Table 1) and pembrolizumab (primary results expected in 2023). 49 Additional trials of interest in HER2-low include those evaluating MRG002, 54 disitamab vedotin (RC48-ADC),55–57 margetuximab,58,59 zenocutuzumab combinations, 60 and precise targeted therapy (based on genome sequencing and patient-derived organoid modeling) for refractory HER2-expressing disease. 61 Read-outs are expected over the next 1–2 years.

Although not captured in Table 1, it should be noted that several other studies are investigating additional HER2-targeted therapies in Phase I trials and in the early-stage setting (e.g., adjuvant, neoadjuvant) of HER2-low breast cancer.73–77 Moreover, real-world data analyses are aiming to increase understanding of HER2-low epidemiology, treatment patterns, and clinical outcomes in daily clinical practice (e.g., RetroBC-HER2L,20,78,79 RosHER, 80 and PALBO01/2021 81 ).

Evidence gaps and challenges

Testing for HER2-low disease

Despite the favorable findings of the DESTINY-Breast04 trial, several questions and challenges remain related to the management of HER2-low mBC. Perhaps most importantly, the accuracy of conventional IHC testing for HER2 has been questioned given its potentially critical impact on identifying suitable patients.82,83 In DESTINY-Breast04, the VENTANA HER2/neu (4B5) assay system was used to identify patients with HER2-low disease in accordance with current guideline recommendations.12,16 The study’s results indicate that this test can accurately identify patients who may benefit from T-DXd therapy; regardless, no validated assay is currently available for evaluation of 1+ and 2+/ISH-negative disease. Additionally, IHC scores are influenced by a multitude of pre- and post-analytical factors, such as variations in tumor expression of HER2 over time, tumor heterogeneity, test sensitivity, and laboratory and reader site/experience, among others.38,82 Concerns have arisen regarding differentiation of lower ranges of HER2 expression (0 and 1+) and reports of poor score concordance rates21,82,83 – standardization is needed. Regardless, standard IHC alone may be suboptimal to define the lower boundary of HER2 expression necessary to predict the clinical activity of some therapies. 38 While novel quantification methods 84 are evaluated (e.g., using DNA/mRNA, protein-based assays, artificial intelligence17,85–87) and the minimum HER2 expression threshold required for T-DXd is determined in clinical trials,21,39 pathologists must be aware that IHC 1+ and 2+/ISH-negative results (and possibly IHC > 0 <1+) are now actionable in mBC, irrespective of HR status.

Treatment-related toxicities: Focus on ILD

ILD is a heterogenous group of more than 200 lung disorders that manifest as inflammation and/or fibrosis of the lungs. Although the spectrum of clinical symptoms and radiographic patterns vary, these disorders are increasingly being recognized as adverse drug events associated with certain anti-cancer therapies. Defining drug-related ILD is challenging, as it is a diagnosis of exclusion and requires careful consideration of patient history, radiographic imaging, pulmonary function tests, and lab findings to exclude other etiologies such as infection. In the T-DXd arm of DESTINY-Breast04, 12.1% of patients experienced ILD or pneumonitis, an incidence rate generally consistent with those reported in previous analyses.35,88–90 Although these events were typically of low or moderate grade, three patients (0.8%) had a fatal grade 5 event. Furthermore, the time to onset of ILD was variable, with a median of 129 days (range, 26–710 days). 12 These findings are not unique – occurrence of ILD has also been reported with use of other anti-cancer therapies.34,91

The molecular mechanism underlying ADC-induced ILD and pneumonitis remains under investigation. Lung epithelial cells express HER2 protein, 92 but whether such expression plays a role in on-target AEs is unclear. Off-target mechanisms have been suggested on the basis of animal studies, in which T-DXd was localized in alveolar macrophages rather than pulmonary epithelial cells. The release of payload and subsequent bystander effect resulting in cytotoxic lung injury is currently hypothesized to cause T-DXd-related ILD. 34 Until more information is available, clinicians must be aware of treatment and patient characteristics that may increase the risk of ILD and pneumonitis, such as drug dose, baseline oxygen saturation, moderate/severe renal impairment, certain lung comorbidities, and time since diagnosis.86,90 Proactive monitoring can successfully identify the symptoms of these AEs and should include regular imaging; active management should involve early administration of glucocorticoids (even among asymptomatic patients) and treatment interruption.34,88 As noted by other groups, the optimal approach to ADC rechallenge after interruption is still unknown: rechallenge is presently only recommended for patients with grade 1 ILD/pneumonitis that resolves, as evidence is limited to those with grade 2+ events. 93 Additional clinical data are needed to further improve patient safety during treatment with T-DXd.

Efficacy of T-DXd in HR-negative disease

Another question is whether HER2-low targetability and outcomes are dependent on HR expression. In DESTINY-Breast04, similar cORRs were reported among HR-positive and HR-negative patients who received T-DXd (52.6% versus 50.0%, respectively); however, a greater difference was observed between groups for OS (hazard ratios: 0.64 [95% CI: 0.48–0.86] versus 0.48 [95% CI: 0.24–0.95]; Table 1, Figure 3). 12 Although the number of HR-negative patients in DESTINY-Breast04 was relatively small in terms of fully understanding this difference (63 randomized patients; 11.3%), the proportion aligns with the general prevalence of these patients in the overall HER2-low population. Further evaluation may be warranted; nonetheless, T-DXd still appears to be an important treatment option for these individuals.

Optimal sequencing of ADCs

As highlighted above, given overlapping treatment populations, determination of optimal sequencing of T-DXd and SG represents another important evidence gap in mBC. Among the HER2-low patients in the respective clinical trials of these agents, hazard ratios for PFS were 0.51 and 0.46 with T-DXd in HR-positive and HR-negative disease, 12 respectively, and 0.58 53 and 0.44 51 with SG. However, naïve cross-trial comparison of results is inappropriate, given differences in study design and baseline patient characteristics. For example, SG-treated patients were more heavily pretreated with chemotherapy (TROPiCS-02: 57% with ⩾3 lines; ASCENT: 71% with two or three lines) than those treated with T-DXd in DESTINY-Breast04 (~60% received one prior line). Only a head-to-head, randomized-controlled clinical trial could elucidate the true comparative efficacy of these agents. Other issues include development of drug resistance while receiving ADC therapy, and whether post-progression sequencing of ADCs will provide clinical benefit. 94 Failure or reduction of the effectiveness of both T-DXd and SG has been reported, although the underlying mechanism(s) remains under investigation.43,95 Numerous theories have been proposed regarding the cause of such resistance, such as reduction of antigen levels/presentation, defective drug internalization and trafficking, aberrant lysosomal function, increased expression of drug efflux pumps, and various alterations in the cell cycle and signaling pathways.43,95 As these changes are hypothesized to be unique to the specific construct of a particular ADC’s antibody, linker, and payload, they may not confer broad resistance to ADCs. 95 Indeed, data indicate that patients with disease that becomes refractory to trastuzumab + taxane therapy still respond to T-DM1, suggesting no relationship between the activity of T-DM1 and previously received anti-HER2 therapy. 96 Additional investigation is needed, potentially derived from real-world data analysis, to understand feasible and effective treatment sequence options, as well as ways to improve the constructs of new ADCs. In the absence of head-to-head comparisons, the authors favor use of T-DXd over SG for HR+/HER2-low patients who would meet the eligibility criteria for these therapies in the DESTINY-Breast04 and TROPiCS-02 trials. T-DXd is preferred in this setting given its higher level of evidence in the HER2-low population (Phase III versus post hoc analyses for SG), as well as the lower number of prior lines of chemotherapy received by patients in DESTINY-Breast04. As always, treatment selection must consider patient risk and preferences and drug side effect profiles, and may also incorporate prescribers’ perceptions and experience with efficacy in the HER2-low population.

Conclusions

The results of DESTINY-Breast04 underscore that in contrast to previous thinking, HER2-low is an actionable target for patients with mBC. The trial’s findings for T-DXd are practice-changing, shifting both the classification of mBC and treatment algorithms for HER2-expressing disease worldwide. Additional research is needed to further refine HER2-low testing and classification, understand the mechanisms underlying drug-induced ILD and drug resistance, and identify the most effective treatment-sequencing pathways. Ongoing investigations of promising novel agents will further expand effective treatment options for this newly identified subset of patients with mBC.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dana L. Anger of WRITRIX Medical Communications Inc. for medical writing assistance, which was funded by AstraZeneca Canada in accordance with Version 3 of the Good Publication Practice guidelines (https://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Christine Brezden-Masley  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4818-318X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4818-318X

Sandeep Sehdev  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7434-2263

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7434-2263

Christine Simmons  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6571-4587

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6571-4587

Contributor Information

Charlie Yang, Tom Baker Cancer Centre, University of Calgary, 1331 29 Street NW, Calgary, AB T2N 4N2, Canada.

Christine Brezden-Masley, Sinai Health System, Mountain Sinai Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Anil Abraham Joy, Cross Cancer Institute, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada.

Sandeep Sehdev, The Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Shanu Modi, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Christine Simmons, BC Cancer Agency – Vancouver Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Jan-Willem Henning, Tom Baker Cancer Centre, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contribution(s): Charlie Yang: Conceptualization; Project administration; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Christine Brezden-Masley: Investigation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Anil Abraham Joy: Investigation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Sandeep Sehdev: Investigation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Shanu Modi: Investigation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Christine Simmons: Investigation; Visualization; Writing – review & editing.

Jan-Willem Henning: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Development and publication of this work were supported by AstraZeneca Canada.

CY had no conflicts to disclose. CB-M reports serving in a consultancy or advisory role and receiving honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Knight Therapeutics, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Seagen, and Taiho and has received research funding from Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca. AAJ has served in a consultancy or advisory role and has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, BMS, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Knight Therapeutics, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Teva. SS reports participating in advisory boards and/or receiving speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Gilead, Roche, Novartis, and Merck. SM has been a scientific advisor for AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Macrogenics, Puma Biotechnology, Seagen, and Zymeworks. SM also reports attending speaking engagements for AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech, Novartis, and Seagen and being a primary investigator on trials for AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech, and Seagen. CS has served in a consultancy or advisory role and received honoraria from Eli Lilly, Mylan, Pfizer, and Roche, and CS has received research funding from AstraZeneca Global, Knight Therapeutics, Roche, Pfizer, and Viatris. J-WH reports serving in a consultancy or advisory role and receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Knight Therapeutics, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Seagen. J-WH also reports having speaking arrangements with Gilead and receiving research grant support from AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Pfizer.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021; 71: 209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryan S, Masoud H, Weir HK, et al. Cancer in Canada: stage at diagnosis. Health Rep 2018; 29: 21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bredin P, Walshe JM, Denduluri N. Systemic therapy for metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer. Semin Oncol 2020; 47: 259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Cancer Society. Survival statistics for breast cancer. Available at: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/breast/prognosis-and-survival/survival-statistics. (2022, accessed 4 October 2022).

- 5.Savard MF, Kornaga EN, Kahn AM, et al. Survival in women with de novo metastatic breast cancer: a comparison of real-world evidence from a publicly-funded Canadian province and the United States by insurance status. Curr Oncol 2022; 29: 383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang R, Zhu Y, Liu X, et al. The clinicopathological features and survival outcomes of patients with different metastatic sites in stage IV breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2019; 19: 1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seung SJ, Traore AN, Pourmirza B, et al. A population-based analysis of breast cancer incidence and survival by subtype in Ontario women. Curr Oncol 2020; 27: e191–e198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swain SM, Miles D, Kim SB, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA): end-of-study results from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: 519–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 942–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giuliani S, Ciniselli CM, Leonardi E, et al. In a cohort of breast cancer screened patients the proportion of HER2 positive cases is lower than that earlier reported and pathological characteristics differ between HER2 3+ and HER2 2+/Her2 amplified cases. Virchows Arch 2016; 469: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lal P, Salazar PA, Hudis CA, et al. HER-2 testing in breast cancer using immunohistochemical analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization: a single-institution experience of 2,279 cases and comparison of dual-color and single-color scoring. Am J Clin Pathol 2004; 121: 631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modi S, Jacot W, Yamashita T, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, et al. ESMO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2021; 32: 1475–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: breast cancer. Version 3. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf (2023, accessed March 25, 2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.BC Cancer. 6.9 metastatic breast cancer. Revised November2017. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/books/breast/management/metastatic-breast-cancer (2017, accessed 5 October 2022).

- 16.Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Allison KH, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 2105–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarantino P, Hamilton E, Tolaney SM, et al. HER2-low breast cancer: pathological and clinical landscape. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 1951–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schettini F, Chic N, Braso-Maristany F, et al. Clinical, pathological, and PAM50 gene expression features of HER2-low breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021; 7: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Won HS, Ahn J, Kim Y, et al. Clinical significance of HER2-low expression in early breast cancer: a nationwide study from the Korean breast cancer society. Breast Cancer Res 2022; 24: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viale G, Niikura N, Tokunaga E, et al. Retrospective study to estimate the prevalence of HER2-low breast cancer (BC) and describe its clinicopathological characteristics. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40: 1087–1087. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bardia A, Barrios C, Dent R, et al. Abstract OT-03-09: trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd; DS-8201) vs investigator’s choice of chemotherapy in patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR+), HER2 low metastatic breast cancer whose disease has progressed on endocrine therapy in the metastatic setting: a randomized, global phase 3 trial (DESTINY-Breast06). Cancer Res 2021; 81: OT-03-09. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim SB, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 724–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fehrenbacher L, Cecchini RS, Geyer CE, Jr., et al. NSABP B-47/NRG oncology phase III randomized trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab in high-risk invasive breast cancer negative for HER2 by FISH and with IHC 1+ or 2. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 444–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burris HA, 3rd, Rugo HS, Vukelja SJ, et al. Phase II study of the antibody drug conjugate trastuzumab-DM1 for the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer after prior HER2-directed therapy. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yazaki S, Hashimoto J, Ogita S, et al. Lower response to T-DM1 in metastatic breast cancer patients with HER2 IHC score of 2 and FISH positive compared with IHC score of 3. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: v102–v103. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hickerson A, Clifton GT, Hale DF, et al. Final analysis of nelipepimut-S plus GM-CSF with trastuzumab versus trastuzumab alone to prevent recurrences in high-risk, HER2 low-expressing breast cancer: a prospective, randomized, blinded, multicenter phase IIb trial. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 1.30422740 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filho OM, Viale G, Trippa L, et al. HER2 heterogeneity as a predictor of response to neoadjuvant T-DM1 plus pertuzumab: results from a prospective clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 502. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gianni L, Llado A, Bianchi G, et al. Open-label, phase II, multicenter, randomized study of the efficacy and safety of two dose levels of pertuzumab, a human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 dimerization inhibitor, in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1131–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krop IE, LoRusso P, Miller KD, et al. A phase II study of trastuzumab emtansine in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer who were previously treated with trastuzumab, lapatinib, an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 3234–3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cronin KA, Harlan LC, Dodd KW, et al. Population-based estimate of the prevalence of HER-2 positive breast cancer tumors for early stage patients in the US. Cancer Invest 2010; 28: 963–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogitani Y, Aida T, Hagihara K, et al. DS-8201a, a novel HER2-targeting ADC with a novel DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor, demonstrates a promising antitumor efficacy with differentiation from T-DM1. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22: 5097–5108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogitani Y, Hagihara K, Oitate M, et al. Bystander killing effect of DS-8201a, a novel anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 antibody-drug conjugate, in tumors with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterogeneity. Cancer Sci 2016; 107: 1039–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swain SM, Nishino M, Lancaster LH, et al. Multidisciplinary clinical guidance on trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd)-related interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis-Focus on proactive monitoring, diagnosis, and management. Cancer Treat Rev 2022; 106: 102378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 610–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krop I, Park YH, Kim SB, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan vs physician’s choice in patients with HER2+ unresectable and/or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with trastuzumab emtansine: primary results of the randomized, phase 3 study DESTINY-Breast02. Abstract GS2-01. In: Presented at San Antonio Breast Cancer SymposiumSan Antonio, TX, 6–10December2022. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurvitz S, Hegg R, Chung W, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan versus trastuzumab emtansine in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: updated survival results of the randomized, phase 3 study DESTINY-Breast03. Abstract GS2-02. In: Presented at San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, TX, 6–10December2022. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Modi S, Park H, Murthy RK, et al. Antitumor activity and safety of trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2-low-expressing advanced breast cancer: results from a Phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 1887–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diéras V, Deluche E, Lusque A, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) for advanced breast cancer patients (ABC), regardless HER2 status: a phase II study with biomarkers analysis (DAISY). Cancer Res 2022; 82: PD8-02. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamilton E, Shapiro CL, Petrylak D, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd; DS-8201) with nivolumab in patients with HER2-expressing, advanced breast cancer: a 2-part, phase 1b, multicenter, open label study. Cancer Res 2021; 81: PD3-07. [Google Scholar]

- 41.NIH. DS-8201a for trEatment of aBc, BRain mets, and Her2[+] disease (DEBBRAH). NCT04420598. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04420598?term=her2-low&cond=Breast+Cancer&draw=2&rank=18 (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 42.Pérez-Garcia J, Vaz Batista M, Cortez P, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with active central nervous system involvement from HER2-low advanced breast cancer: the DEBBRAH trial. Poster PD7-02. In: San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, TX, 6–10December2022. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez-Garcia JM, Batista MV, Cortez P, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with central nervous system involvement from HER2-positive breast cancer: the DEBBRAH trial. Neuro Oncol 2022; 25: 157–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaz Batista MC, Patricia RM, Cejalvo JM, et al. Abstract PD4-06: trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2[+] or HER2-low-expressing advanced breast cancer and central nervous system involvement: preliminary results from the DEBBRAH phase 2 study. Cancer Res 2022; 82: PD4-06. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmid P, Im S-A, Armstrong A, et al. BEGONIA: phase 1b/2 study of durvalumab (D) combinations in locally advanced/metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)—Initial results from arm 1, d+paclitaxel (P), and arm 6, d+trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd). J Clin Oncol 2021; 39: 1023. [Google Scholar]

- 46.NIH. A phase 1b study of T-DXd combinations in HER2-low advanced or metastatic breast cancer (DB-08). NCT04556773. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04556773?term=her2-low&cond=breast+cancer&draw=2&rank=3 (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 47.Jhaveri K, Hamilton E, Loi S, et al. Abstract OT-03-05: trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd; DS-8201) in combination with other anticancer agents in patients with HER2-low metastatic breast cancer: A phase 1b, open-label, multicenter, dose-finding and dose-expansion study (DESTINY-Breast08). Cancer Res 2021; 81: OT-03-05. [Google Scholar]

- 48.André F, Hamilton EP, Loi S, et al. Dose-finding and expansion studies of trastuzumab deruxtecan in combination with other anticancer agents in patients with advanced/metastatic HER2+ (DESTINY-Breast07) and HER2-low (DESTINY-Breast08) breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40: 3025. [Google Scholar]

- 49.NIH. DS5204a and pembrolizumab in participants with locally advanced/metastatic breast or non-small cell lung cancer. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04042701. (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 50.Bardia A, Hurvitz SA, Tolaney SM, et al. Sacituzumab govitecan in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1529–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hurvitz SA, Bardia A, Punie K, et al. 168P - Sacituzumab govitecan (SG) efficacy in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) by HER2 immunohistochemistry (IHC) status: findings from the phase 3 ASCENT study. Ann Oncol 2022; 33: S194–S223. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rugo HS, Bardia A, Marmé F, et al. Sacituzumab govitecan in hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor negative metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40: 3365–3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmid P, Cortés J, Marmé F, et al. 214MO Sacituzumab govitecan (SG) efficacy in hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (HR+/HER2-) metastatic breast cancer (MBC) by HER2 immunohistochemistry (IHC) status in the phase III TROPiCS-02 study. Ann Oncol 2022; 33: S635–S636. [Google Scholar]

- 54.NIH. A study of MRG002 in the treatment of patients with HER2-low locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (BC). NCT04742153. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04742153. (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 55.NIH. A study of RC48-ADC for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer with low expression of HER2. NCT04400695. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04400695. (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 56.NIH. A study of RC48-ADC for the treatment of HER2-expression metastatic breast cancer with abnormal activation of PAM pathway. NCT05331325. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05331326?term=her2-low&cond=Breast+Cancer&draw=2&rank=15. (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 57.NIH. Disitamab vedotin (RC48) combined with penpulimab (AK105) for neoadjuvant treatment of HER2-low breast cancer. NCT05726175. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05726175 (2023, accessed 20 March 2023).

- 58.Pegram MD, Tan-Chiu E, Miller K, et al. A single-arm, open-label, phase 2 study of MGAH22 (margetuximab) [fc-optimized chimeric anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody (mAb)] in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced breast cancer whose tumors express HER2 at the 2+ level by immunohistochemistry and lack evidence of HER2 gene amplification by FISH. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: TPS671. [Google Scholar]

- 59.NIH. Phase 2 study of the monoclonal antibody MGAH22 (Margetuximab) in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced breast cancer. NCT01828021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01828021?term=NCT01828021&draw=2&rank=1 (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 60.Pistilli B, Wildiers H, Hamilton EP, et al. Clinical activity of MCLA-128 (zenocutuzumab) in combination with endocrine therapy (ET) in ER+/HER2-low, non-amplified metastatic breast cancer (MBC) patients (pts) with ET-resistant disease who had progressed on a CDK4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i). J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 1037. [Google Scholar]

- 61.NIH. Precise therapy for refractory HER2 positive advanced breast cancer. NCT05429584. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05429684?term=her2-low&cond=Breast+Cancer&draw=2&rank=21 (2022, accessed 25 October 2022).

- 62.Modi, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) vs treatment of physician’s choice in patients with HER2-low unresectable and/or metastatic breast cancer: Results of DESTINY-Breast04, a randomized, phase 3 study. Presented at ASCO 2022, June 5, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 63.André F, Ciruelos E, Rubovszky G, et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 1929–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bidard F-C, Kaklamani VG, Neven P, et al. Elacestrant (oral selective estrogen receptor degrader) versus standard endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced breast cancer: results from the randomized phase III EMERALD trial. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40: 3246–3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robson M, Goessl C, Domchek S. Olaparib for metastatic germline BRCA-mutated breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1792–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tung NM, Robson ME, Ventz S, et al. TBCRC 048: phase II study of olaparib for metastatic breast cancer and mutations in homologous recombination-related genes. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 4274–4282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bonotto M, Gerratana L, Iacono D, et al. Treatment of metastatic breast cancer in a real-world scenario: is progression-free survival with first line predictive of benefit from second and later lines? Oncologist 2015; 20: 719–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matikas A, Kotsakis A, Perraki M, et al. Objective response to first-line treatment as a predictor of overall survival in metastatic breast cancer: a retrospective analysis from two centers over a 25-year period. Breast Care 2022; 17: 264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cortés J, O’Shaughnessy J, Loesch D, et al. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet 2011; 377: 914–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kaufman PA, Awada A, Twelves C, et al. Phase III open-label randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perez EA, Lerzo G, Pivot X, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixabepilone (BMS-247550) in a phase II study of patients with advanced breast cancer resistant to an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 3407–3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rugo HS, Bardia A, Marmé F, et al. LBA76 - overall survival (OS) results from the phase III TROPiCS-02 study of sacituzumab govitecan (SG) vs treatment of physician’s choice (TPC) in patients (pts) with HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer (mBC). Ann Oncol 2022; 33: S808–S869. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gianni L, Colleoni M, Bisagni G, et al. Effects of neoadjuvant trastuzumab, pertuzumab and palbociclib on Ki67 in HER2 and ER-positive breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022; 8: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.NIH. Therapeutic cancer vaccine (AST-301, pNGVL3-hICD) in patients with breast cancer (Cornerstone001). NCT05163223. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05163223?term=her2-low&cond=Breast+Cancer&draw=2&rank=6 (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 75.NIH. Phase II neoadjuvant pyrotinib combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-low-expressing and HR positive early or locally advanced breast cancer: a single-arm, non-randomized, single-center, open label trial. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05165225?term=her2-low&cond=Breast+Cancer&draw=2&rank=8. NCT05165225. (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 76.NIH. Trastuzumab deruxtecan alone or in combination with anastrozole for the treatment of early stage HER2 low, hormone receptor positive breast cancer. NCT04553770. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04553770?term=her2-low&cond=Breast+Cancer&draw=2&rank=9 (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 77.NIH. Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center breast cancer precision platform series study- neoadjuvant therapy (FASCINATE-N). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05582499?term=her2-low&cond=Breast+Cancer&draw=2&rank=26 (2022, accessed 25 October 2022).

- 78.Spitzmüller A, Kapil A, Shumilov A, et al. Computational pathology-based HER2 expression quantification in HER2-low breast cancer. Poster P6-04-03. In: San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, TX, 6–10December2022. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Viale G, Basik M, Niikura N, et al. Retrospective study to estimate the prevalence and describe the clinicopathological characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcomes of HER2-low breast cancer. Poster HER2-15. In: San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, TX, 6–10December2022. [Google Scholar]

- 80.NIH. Real-world data of clinicopathological characteristics and management of breast cancer patients according to HER2 status (RosHER). NCT05217381. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05217381?term=her2-low&cond=Breast+Cancer&draw=2&rank=20. (2022, accessed 24 October 2022).

- 81.NIH. Study of real-world evidence in patients treated with palbociclib during a 2.5 year follow-up period (PALBO). NCT05135104. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05135104?term=her2-low&cond=Breast+Cancer&draw=2&rank=27 (2022, accessed 25 October 2022).

- 82.Fernandez AI, Liu M, Bellizzi A, et al. Examination of low ERBB2 protein expression in breast cancer tissue. JAMA Oncol 2022; 8: 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tarantino P, Curigliano G, Tolaney SM. Navigating the HER2-low paradigm in breast oncology: new standards, future horizons. Cancer Discov 2022; 12: 2026–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moutafi M, Robbins CJ, Yaghoobi V, et al. Quantitative measurement of HER2 expression to subclassify ERBB2 unamplified breast cancer. Lab Invest 2022; 102: 1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zoppoli G, Garuti A, Cirmena G, et al. Her2 assessment using quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction reliably identifies Her2 overexpression without amplification in breast cancer cases. J Transl Med 2017; 15: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wu S, Yue M, Zhang J, et al. The role of artificial intelligence in accurate interpretation of HER2 immunohistochemical scores 0 and 1+ in breast cancer. Mod Pathol 2023; 36: 100054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hicks DG, Buscaglia B, Goda H, et al. A novel detection methodology for HER2 protein quantitation in formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded clinical samples using fluorescent nanoparticles: an analytical and clinical validation study. BMC Cancer 2018; 18: 1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Powell CA, Modi S, Iwata H, et al. Pooled analysis of drug-related interstitial lung disease and/or pneumonitis in nine trastuzumab deruxtecan monotherapy studies. ESMO Open 2022; 7: 100554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cortés J, Kim SB, Chung WP, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan versus trastuzumab emtansine for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 1143–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yin O, Iwata H, Lin CC, et al. Exposure-response relationships in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer and other solid tumors treated with trastuzumab deruxtecan. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021; 110: 986–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hackshaw MD, Danysh HE, Singh J, et al. Incidence of pneumonitis/interstitial lung disease induced by HER2-targeting therapy for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020; 183: 23–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Press MF, Cordon-Cardo C, Slamon DJ. Expression of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in normal human adult and fetal tissues. Oncogene 1990; 5: 953–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rugo HS, Bianchini G, Cortés J, et al. Optimizing treatment management of trastuzumab deruxtecan in clinical practice of breast cancer. ESMO Open 2022; 7: 100553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ocaña A, Amir E, Pandiella A. HER2 heterogeneity and resistance to anti-HER2 antibody-drug conjugates. Breast Cancer Res 2020; 22: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Collins DM, Bossenmaier B, Kollmorgen G, et al. Acquired resistance to antibody-drug conjugates. Cancers (Basel) 2019; 11: 394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Amiri-Kordestani L, Blumenthal GM, Xu QC, et al. FDA approval: ado-trastuzumab emtansine for the treatment of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 4436–4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]