Abstract

Purpose: Multiple Canadian jurisdictions have curtailed public funding for outpatient physiotherapy services, impacting access and potentially creating or worsening inequities in access. We sought to identify evaluated organizational strategies that aimed to improve access to physiotherapy services for community-dwelling persons. Method: We used Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review methods, including a systematic search of CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Embase for relevant peer-reviewed texts published in English, French, or German, and we performed a qualitative content analysis of included articles. Results: Fifty-one peer-reviewed articles met inclusion criteria. Most studies of interventions or system changes to improve access took place in the United Kingdom (17), the United States (12), Australia (9), and Canada (8). Twenty-nine studies aimed to improve access for patients with musculoskeletal conditions; only five studies examined interventions to improve equitable access for underserved populations. The most common interventions and system changes studied were expanded physiotherapy roles, direct access, rapid access systems, telerehabilitation, and new community settings. Conclusions: Studies evaluating interventions and health system changes to improve access to physiotherapy services have been limited in focus, and most have neglected to address inequities in access. To improve equitable access to physiotherapy services in Canada, physiotherapy providers in local settings can implement and evaluate transferable patient-centred access strategies, particularly telerehabilitation and primary care integration.

Key Words: health equity, health services accessibility, health services research, physical therapy specialty, review

Abstract

Objectif : de multiples régions sociosanitaires canadiennes ont limité le financement des services de physiothérapie ambulatoires, ce qui a des conséquences sur l’accès et qui risque de créer ou d’aggraver les inégalités en matière d’accès. Les chercheurs ont cherché à définir les stratégies organisationnelles évaluées afin d’améliorer l’accès aux services de physiothérapie pour les personnes qui vivent dans la communauté. Méthodologie : les chercheurs ont utilisé les méthodologies d’étude de portée, y compris des recherches systématiques dans les bases de données CINAHL, MEDLINE et Embase pour en extraire les textes révisés par un comité de lecture publiés en anglais, en français ou en allemand, et ont effectué une analyse qualitative du contenu des articles extraits. Résultats : au total, 51 articles révisés par un comité de lecture respectaient les critères d’inclusion. La plupart des études sur les interventions ou les changements systémiques visant à améliorer l’accès ont été réalisées au Royaume-Uni (17), aux États-Unis (12), en Australie (9) et au Canada (8). Ainsi, 29 études ont visé à améliorer l’accès aux patients atteints d’affections musculosquelettiques; seulement cinq ont porté sur des interventions pour améliorer l’accès équitable aux populations mal desservies. Les interventions et les changements systémiques les plus courants étudiés dans le présent article ont entraîné un élargissement des rôles physiothérapiques, des systèmes d’accès direct, de la téléréadaptation et de nouveaux milieux communautaires. Conclusions :les études sur les interventions et les changements aux systèmes de santé pour améliorer l’accès aux services physiothérapiques ont eu une portée limitée, et la plupart ont négligé d’aborder les inégalités en matière d’accès. Pour améliorer un accès équitable aux services physiothérapiques au Canada, les dispensateurs de soins physiothérapiques locaux peuvent adopter et évaluer des stratégies d’accès transférables axées sur les patients, notamment la téléréadaptation et l’intégration des soins de première ligne.

Mots-clés : : accessibilité des services de santé, analyse, équité en matière de santé, recherche sur les services de santé, spécialité de la physiothérapie

Access to health care is “the opportunity or ease with which consumers or communities are able to use appropriate services in proportion to their need.”1(p.2) Access is a focus of health system reforms in Canada, particularly since the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada most recently reaffirmed it in an August 2017 health policy statement.2,3 Canada is not alone in this policy emphasis. For example, one of the four strategic outcomes in Australia’s National Primary Health Care Strategic Framework4 is to improve access and reduce inequity. Similarly, the latest National Health Services (NHS) England constitution affirmed the core principle that “access to NHS services is based on clinical need,”5(Jan 14, 2021) and the related handbook6 outlines government pledges on wait times for selected services.

Most Canadian health system performance targets that the Canadian Institute of Health Information tracks emphasize access to physician care (specialists and primary care providers)7 or to medical diagnostics and treatments (e.g., radiation therapy, hip replacement surgery).8 However, access to medical care does not necessarily mean access to appropriate health care; sometimes other health professionals can best meet patients’ needs. For example, a Manitoba policy report recognized patients’ lack of access to rehabilitation professionals, including physiotherapists, as a cause of longer stays in acute care facilities, resulting in unnecessary health care expenditures.9 Current discussions addressing health system access and performance in Canada have focused on addiction, mental health, and home and community care.10 Indicator development is under way, but to date, the 12 newly identified priority topics have little connection to health conditions physiotherapists treat in outpatient services.10

Canada’s universal public health insurance systems are founded on the principle of equity: that need should drive access, not ability to pay. However, the federal public health care laws, including the Canada Health Act,11 do not mandate public insurance to insure physiotherapy services beyond inpatient care. Thus, public insurance in provincial and territorial systems does not ensure access to community-based physiotherapy.11 As a result, a combination of private and public funds pay for outpatient physiotherapy services in Canada. When publicly funded physiotherapy clinics were defunded by the Government of Ontario in 2005, 18% of patients on wait-lists at the time did not receive care due to lack of insurance or other means to pay.12 Patients financially unable to access private physiotherapy had poorer self-reported health status than those who accessed physiotherapy through private funds.12 This finding is consistent with a systematic review of allied health services use by people with chronic conditions that found that lack of insurance was an independent predictor of physiotherapy care utilization13 and that among those who were insured, covariates of access included race (non-white and minority populations accessed care less), education, and income.13 This review highlighted the need to consider equity of access within initiatives.

Inherent in the concept of access is the principle of equity. Equity in health care includes equal access to health care based on equal need.14,15 Access, from an equity perspective, implies that health systems mitigate barriers (e.g., affordability, geographical distribution) to obtaining appropriate, medically indicated services as much as possible to reduce inequities (defined as health inequalities that reflect injustice).14,15

Recent Canadian research has highlighted inequities in access to physiotherapy in Canada. Researchers in Saskatchewan documented gaps in access to physiotherapy in rural and remote areas, where population health needs tend to be higher,16,17 and providers are exploring the use of technologies to bridge geographical access gaps.18 In Quebec, researchers have highlighted disparities by examining the distribution of physiotherapy services in relation to need19 and exploring the methods hospital-based outpatient clinics use to manage wait-lists.20 A scoping review of unmet need for physiotherapy in Canada suggested that people living in rural areas and those with chronic conditions faced more barriers in accessing care,21 a finding reinforced by an analysis of the distribution of physiotherapists in Canada against utilization rates.22

To date, no review of the literature has explored strategies that health systems and physiotherapy providers can consider to improve access to physiotherapy services. The purpose of this scoping review was to identify organizational strategies that aimed to improve access to physiotherapy services. We did so to identify system opportunities that could help address access inequities in local systems, ensuring that the people most in need receive appropriate and timely services. We sought to answer the following question: What supply-side strategies have been evaluated that aimed to improve or resulted in improved access to physiotherapy services for community-dwelling persons?

Conceptual framework

Access to appropriate health care is influenced both by people’s ability to identify and seek health care to meet their needs and by the services organizations offer.14 We focused on the latter, supply-side influence, given our overarching objective to identify evaluated interventions that organizations have implemented to improve patient-centred access to physiotherapy care. We used Levesque and colleagues’14 patient-centred access to health care conceptual framework to guide our review.

The patient-centred access to health care conceptual framework highlights five interdependent dimensions that co-determine access: approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness.14 These five terms represent dimensions of access that are influenced by health care organizations; that is, these terms represent the supply-side of health care. Levesque and colleagues created the framework through a synthesis of published literature conceptualizing access, by identifying determinants and dimensions of access from each source to develop the framework. They did so to address a lack of conceptual clarity on the topic of access by creating a common conceptualization that operationalizes both demand- and supply-side factors in access and “better incorporat[es] patient-centred perspectives into population and system level approaches.”14(p. 2) Table 1 defines each of the five dimensions of the supply-side of patient-centred access to health care.

Table 1 .

Supply-Side Dimensions of the Patient-Centred Access to Health Care Conceptual Framework

| Dimension | Definition* |

|---|---|

| Approachability | “People facing healthcare needs can identify that some form of services exists, can be reached, and have an impact on their health.” |

| Acceptability | “Social and cultural factors determining the possibility for people to accept the aspects of a service.” |

| Availability and accommodation | “Health services (either the physical space or those working in healthcare roles) can be reached both physically and in a timely manner.” |

| Affordability | “The economic capacity for people to spend resources and time to use appropriate services.” |

| Appropriateness | “The fit between services and clients’ needs, its timeliness, the amount of care spent in assessing health problems and determining the correct treatment and the technical and interpersonal quality of the services provided.” |

According to the framework, health service providers should respond to population characteristics and ensure that individuals can reach services when they need care. This framework identifies various dimensions of access to consider when assessing whether a health care service is accessible to certain populations, and it can provide guidance for policies aimed at identifying and addressing gaps in access.14 Richard and colleagues1 considered this model to be a framework for equitable access to health care. The dimensions of access align with an equity perspective of access by considering factors such as geography, financial barriers, and cultural appropriateness, each of which may influence the opportunities different social groups have to access appropriate health care.1

Richard and colleagues1 applied the patient-centred access to health care framework to explore innovations to support access to primary health care for vulnerable populations, and to identify gaps in addressing different dimensions. In this scoping review, we applied the framework to the physiotherapy literature on access to identify what interventions have been evaluated and what supply-side access dimensions remain under-explored in the peer-reviewed, published studies of physiotherapy. We did so recognizing that studying access implies consideration of inequity of access.

Methods

We completed a scoping review using Arksey and O’Malley’s23 framework to identify and review peer-reviewed publications about organizational strategies that aimed to improve or resulted in improved patient access to physiotherapy services. Scoping reviews are useful to determine the amount and scope of literature available on a subject24 and identify gaps.23,25

Research questions

We sought to answer the following question: What supply-side strategies have been evaluated that aimed to improve or resulted in improved access to physiotherapy services for community-dwelling persons?

Our review sought to answer the research question above, by developing the following six queries:

What study designs were used?

In what countries were the studies completed?

What did the interventions seek to improve?

What outcomes were evaluated for the interventions?

What were the most common types of interventions studied?

What populations were studied?

Search strategy

We conducted a search of CINAHL, Embase, and MEDLINE with the support of an academic librarian. Search limits were publication year (2000–2019), languages spoken by our research team (English, French, and German), and format (we excluded conference abstracts). We did not review reference lists, search for related articles by authors of included studies, or complete a grey literature search due to time and funding limitations. We imported search results into EndNote, then eliminated duplications following Bramer and Giustini’s26 method.

Study selection

For studies published in English, we completed initial screening of titles and abstracts in a sequence of reviews. TC completed an initial sorting in Endnote, categorizing titles and abstracts of articles into the categories “include,” “exclude,” and “second review needed.” JP and SW each reviewed half of the titles and abstracts needing a second review. PT completed a third review when needed to decide on inclusion for full-text screening. For French and German articles, MF alone was responsible for title and abstract review.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria evolved as we collected more detailed data, consistent with the iterative nature of scoping reviews.27 Initial eligibility criteria for titles and abstracts were broad: Studies had to be original research published in a peer-reviewed academic journal, with a population of community-dwelling persons, examining the supply side of access to physiotherapy care.14 We excluded studies of inpatient or institutionalized patient populations and studies focused solely on health care utilization. After reviewing a subset of full-text articles, we developed an additional inclusion criterion: Studies had to include an evaluation of an intervention or system change that addressed one of the five dimensions of patient-centred access to health care according to Levesque and colleagues’1,14 framework and definitions, even if not the primary emphasis. This additional criterion prompted a second review of the full-text articles.

Charting the data

We created an Excel data extraction form and coding manual. For the included articles, we extracted information about study design, country, intervention details, the outcomes evaluated, and patient population (both medical conditions and demographics such as socio-economic status, age, and sex or gender, if specified). TC and PT reviewed TC’s data extraction for the first 20 articles to ensure consensus; TC then completed data extraction.

We then conducted a qualitative content analysis to categorize three elements of each study: (1) patient-centred access to health care dimensions the intervention addressed, (2) type of intervention, and (3) outcomes evaluated. Qualitative content analysis is a method researchers use to interpret textual data using a systematic coding process.28 We also completed a conventional qualitative content analysis28 for type of intervention and corresponding outcome measures. Authors TC, JP, SW, and PT were involved. Conventional content analysis is an inductive process of category development based on patterns researchers notice when categorizing interventions and the outcome measures that were used to assess each intervention. Table 2 lists the categories of types of intervention and Table 3 the categories of evaluated outcomes that we developed and applied to the included studies; multiple outcome categories applied to some studies.

Table 2 .

Categories of Types of Intervention

| Type of intervention | Definition |

|---|---|

| Expansion of the physiotherapy role within the health care system | Physiotherapists took on new or expanded roles within the local health care system. |

| Direct access | Patients were able to self-refer to physiotherapy services rather than having to obtain a physician’s referral. |

| Rapid access for priority patients | The intervention used a prioritization system for certain patient populations. |

| Telerehabilitation | The intervention used technology to increase patients’ access to physiotherapy services. |

| Physiotherapy in new community settings | The intervention included co-locating physiotherapists in unconventional community spaces. |

Table 3 .

Categories of Evaluated Outcomes

| Outcome | Definition |

|---|---|

| Clinical outcomes | Measures of patients’ health, including but not limited to standardized outcome measures. |

| Non-clinical impacts on patients | Impacts on patients other than clinical outcomes (e.g., impact on days off work) |

| Health system costs | Any type of analysis of health system costs from the intervention. |

| Health system functioning | Any analysis of health system impact beyond the physiotherapy service itself (e.g., reduced wait-lists for surgery). |

| Physiotherapy clinic functioning | Measures of physiotherapy clinic functioning (e.g., wait-list duration, change in volume). |

| Quality and safety of physiotherapy care | Any evaluation of the quality or safety of physiotherapy care provided. |

| Patient and/or caregiver perspectives | Patient and/or caregiver opinions about the intervention, including satisfaction and concerns. |

| Provider perspectives | Physiotherapists’ and other clinicians’ opinions about the intervention, including satisfaction and concerns. |

We categorized the dimensions of patient-centred access to health care14 (Table 1) via a directed content analysis28 of each article. In directed content analyses, researchers categorize data by applying pre-existing frameworks.28 We considered whether the intervention aimed to improve approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability, and/or appropriateness. However, interventions in some studies did not focus solely on patient-centred access. We added another category of outcomes evaluated, health system effects, with two subcategories: health system functioning and health system costs. We coded health system functioning when the intervention directly addressed wait times or medical resource use (e.g., need for diagnostic imaging or physician appointments). We coded health system costs when the study measured the intervention’s direct financial impacts on the health care system.

Results

Through title and abstract review, we identified 219 potential full-text articles. Of these 219, we were unable to secure five through interlibrary loans within 3 months. Of the remaining 214, we identified 51 articles for inclusion, all published in English. See online Appendix 1 for the diagram showing the flow of articles through the inclusion process.

What study designs were used?

Nineteen descriptive29 studies30–48 had designs involving surveys, case reports, and retrospective record reviews. Seventeen studies16,49–64 had exploratory designs, including qualitative case studies, secondary data analysis, and prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Fifteen studies had experimental designs; based on the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) study design definitions,65 these studies included 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs),66–71 1 cluster RCT,72 3 controlled before–after studies,73–75 and 5 studies with “other” experimental designs.76–80 All of the RCTs and 1 controlled before–after study met the EPOC minimum recommended number of intervention sites and control sites.

In what countries were the studies completed?

The majority of studies took place in one of five countries: the United Kingdom (U.K.)(17),34,37,38,43,47,58,60,63,67,69–74,79,80 the United States (12),31,32,36,42,46,49,50,52,53,59,77,78 Australia (9),33,48,51,54,55,61,66,75,76 Canada (8),30,35,39–41,44,64,81 and Sweden (2).57,68 One study took place in each of the Netherlands,56 New Zealand,62 and Thailand.45

What did the intervention seek to improve?

Table 4 lists the conceptual framework dimensions that each study’s intervention addressed. Few interventions had a singular focus. All but 11 studies considered a health system effect in addition to a framework dimension.

Table 4 .

Dimensions of Focus in Study Interventions

| Intervention focus | No. of studies* | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-centred access dimensions | ||

| Approachability | 3 | 32 , 34 , 72 |

| Acceptability | 2 | 62 , 75 |

| Availability and accommodation | 31 | 32 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 39 – 41 , 46 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 54 – 56 , 58 , 60 – 64 , 66 – 71 , 73 , 75 , 78 – 80 |

| Affordability | 2 | 59 , 73 |

| Appropriateness | 44 | 30 – 33 , 35 – 49 , 51 – 53 , 55 – 58 , 60 , 61 , 63 , 64 , 66 , 67 , 69 – 79 , 81 |

| Health system effects | ||

| Health system functioning | 29 | 30 , 31 , 36 , 37 , 43 – 45 , 47 – 49 , 52 , 54 , 56 – 59 , 61 – 64 , 66 – 68 , 70 , 72 , 73 , 75 , 79 , 80 |

| Health system costs | 23 | 30 , 32 , 33 , 37 , 43 , 48 – 51 , 53 , 55 , 59 , 60 , 63 , 64 , 66 , 67 , 69 , 72 , 74 , 77 – 79 |

Some studies focused on >1 dimension of the patient-centred access to health care conceptual framework.

What outcomes were evaluated for the interventions?

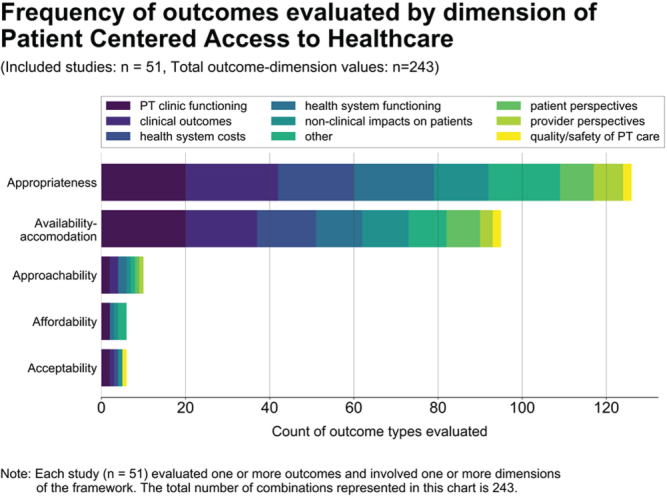

The majority of included studies evaluated impact in multiple ways. Common outcomes evaluated were physiotherapy clinic functioning (20% of 51 studies), patient and/or caregiver perspectives (18%), clinical outcomes (13%), health system costs (13%), provider perspectives (12%), and health system functioning (11%). Non-clinical impacts on patients (7%) and quality and safety of physiotherapy care (5%) were the least frequently evaluated outcomes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Outcome types evaluated in order of frequency, by dimension of the patient-centred access to health care framework.

PT = physiotherapy.

What were the most common types of interventions studied?

Expansion of the physiotherapy role within the health care system

The most common intervention was expansion of the physiotherapy role within the health care system. Fourteen studies conducted in multiple countries evaluated expansions in which physiotherapists practiced new roles, often collaboratively, within health care systems.30,35,39,43,44,48,51,52,55,57,58,61,63,81 In 13 (93%) of these studies, physiotherapists collaborated with a physician specialist30,35,39,43,44,48,51,52,55,58,61,63,81; the physiotherapists (1) assessed need for specialist care, placement on surgical wait-lists, or diagnostic imaging and/or (2) provided treatment or recommendations when appropriate. Six studies30,35,43,44,48,81 used physiotherapists to assess and triage patients to surgical wait-lists.

One study57 evaluated physiotherapists as primary assessors of patients presenting to primary care for a musculoskeletal complaint. Based on chart review results, 85% off the 432 patients the physiotherapists assessed did not require a physician visit. The researchers also compared satisfaction with care for subsample of 110 patients with musculoskeletal complaints; physiotherapist-assessed patients reported higher levels of satisfaction with the information they received than those who were assessed by a physician.

Outcomes evaluated for physiotherapy role expansion focused primarily on health system costs and health system functioning. Studies that considered patient and provider perspectives and clinical outcomes consistently demonstrated cost reductions and increases in health care system efficiency. Studies that evaluated satisfaction found that patients and providers were satisfied with the services the physiotherapists provided.

Direct access

Thirteen studies evaluated direct access to physiotherapy services.31,32,38,42,49,53,56,57,60,72–74,77 Direct access occurs when patients are able to self-refer to physiotherapy services rather than requiring referral by a physician. Studies conducted in the United States,31,32,42,49,53,77 the United Kingdom,38,60,72–74 the Netherlands,56 and Sweden57 evaluated direct access, primarily by evaluating costs incurred by the health system. For example, Holdsworth and colleagues74 compared the costs to NHS Scotland of self-referral versus general practitioner referral to physiotherapy services. Of the 8 studies that evaluated health system costs, 6 found lower costs per episode of care for direct-access patients,31,49,53,60,74,77 and 2 studies32,72 found no cost differences.

Three studies of direct access evaluated quality and safety of physiotherapy care.32,42,57 Mintken and colleagues42 performed a 10-year retrospective analysis to determine whether direct access to physiotherapy placed patients at greater risk for adverse events or negligent care. Of 12,976 patients who accessed physiotherapy without physician referral, there were no reported cases of unidentified serious medical pathology, no adverse events, and no cases of disciplinary action taken against a physiotherapist. All three studies concluded that physiotherapists provide high-quality and safe care.

Rapid access for priority patients

Seven studies evaluated rapid access for priority patients – that is, prioritization systems for physiotherapy to facilitate timely appointments for patients with specific conditions. Researchers in the U.K.,47,79,80 Australia,54 Canada,41 Sweden,68 and the United States78 conducted rapid access studies, evaluating wait-list times, health system costs, number of physiotherapy clinic visits, and both clinical and non-clinical (e.g., time off work) outcome measures. Of the studies that evaluated clinical outcomes,68,78–80 all found equivalent outcomes in both the rapid access and usual care groups. Other areas of improvement included reduced numbers of visits to physicians68 and physiotherapists.78,79

Telerehabilitation

Seven studies evaluated telerehabilitation, in which physiotherapists delivered care via video or telephone conferencing. Most telerehabilitation studies took place in the United Kingdom,37,60,69–71 with one each in Canada40 and the United States.46 All five U.K. telerehabilitation studies evaluated approaches to telephone-led assessment, triage, or treatment services in the NHS. 37,60,69–71 Physiotherapists provided patients with advice over the phone regarding their condition and screened them for the necessity of an in-person appointment. Outcomes evaluated focused on physiotherapy clinic functioning (e.g., reduction in wait times) and patient or provider perspectives. All studies determined that the telephone service improved patients’ timely access to physiotherapy care.

The two studies of telerehabilitation via videoconferencing40,46 sought to create or improve access to physiotherapy services. Kairy and colleagues40 used videoconferencing to provide twice-weekly physiotherapy services to patients after knee replacement. Patients interviewed at the conclusion of the sessions were supportive of the telerehabilitation intervention but thought the process should be complemented with occasional in-person visits.

Physiotherapy in new community settings

Seven studies evaluated physiotherapy in new community settings, which were unconventional community spaces physiotherapists moved into to offer services. Three studies were from Australia,48,66,75 two from the U.K.,34,67 and 1 each from Canada35 and New Zealand.62 The new settings included a home-based respiratory rehabilitation programme66 and a homeless shelter where physiotherapists initiated services.34 Two studies66,67 compared community-based cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation to hospital-based care; both studies found clinical outcomes and costs to be similar between settings. Three studies exploring patient or provider perspectives34,35,75 found that community-based physiotherapy increased patient satisfaction, provided a positive rehabilitation experience, and reduced barriers to accessing care.

What populations were studied?

The majority of studies (29; 57%) evaluated interventions for patients with musculoskeletal conditions. Twelve focused on general musculoskeletal physiotherapy,37,49,51,52,54,57,58,69,70,72,77,78 11 on low back pain physiotherapy,30,47,48,53,59,63,68,71,79–81 4 on arthroplasty-related physiotherapy35,40,43,55 and one study each focused on physiotherapy for pelvic pain,61 and arthritic conditions.44

Only five studies34,35,46,50,62 evaluated interventions explicitly aimed at improving access to physiotherapy services for marginalized populations34,50,62 or individuals in rural and remote locations.35 These populations often lack access to services, contributing to health inequities. For example, Perry and colleagues62 found that the provision of outpatient physiotherapy services in a primary care clinic located in an under-served community in New Zealand served a population that was demographically similar to the surrounding community, while the hospital-based outpatient physiotherapy service did not. The hospital-based outpatient physiotherapy service disportionately cared for New Zealanders of european descent, across a range of socioeconomic levels. When compared to the city’s population, the hospital-based outpatient clinic lacked attendance from populations who experience health inequities, including ethnic minorities, indigenous peoples (Maori and Pacific Islanders), and people with low socioeconomic resources. The physiotherapy services provided in the community primary care clinic resulted in significantly increased attendance from the latter populations, reducing access disparities. The authors hypothesized that the location of the clinic addressed access barriers, including transportation, costs, cultural acceptability, and thus was better able to address community-specific needs.62

Discussion

The scoping review included 51 peer-reviewed, empirical evaluations of the impacts of organizational strategies that aimed to improve, or resulted in improved access to physiotherapy. System changes the studies evaluated included expanding the role of physiotherapy within the health system (either in new care pathways or in advanced practice roles), allowing patients direct access to services, providing rapid access for prioritized clinical populations, using telerehabilitation strategies, and moving physiotherapists into new community settings to improve access. While access to health care is multidimensional, most (91.5%) of the studies addressed the availability and appropriateness dimensions of patient-centred access, whereas few (8.5%) examined approachability, acceptability, and affordability. We interpret this finding, broadly, as indicating that health system priorities such as cost containment and efficiency are the emphasis of published studies to date.

Our review highlights possibilities to explore in the Canadian context. Telerehabilitation services for initial consultation and advice may be useful to strengthen access to physiotherapy given known access disparities in rural, remote, and northern communities.22 With the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, infrastructure for various forms of virtual care has expanded, and more researchers have begun to evaluate it. If the move to telerehabilitation made during the emergency becomes a more permanent health system redesign, physiotherapists may need support to improve delivery in order to maximize their impact.82

Embedding physiotherapists in primary care may be a useful direction in Canadian systems, given ongoing efforts to strengthen primary care delivery of comprehensive, coordinated, and person-focused care, as well as the known benefits of strong primary care systems for population health and health system sustainability.83 Physiotherapists’ scope of practice is well aligned with ambulatory care needs in primary care. NHS England has developed a “first contact practitioner” model of advanced musculoskeletal physiotherapy in primary care, which is similar to the intervention in Ludvigsson and colleagues’57 study in which physiotherapists directly managed all appointments for patients with musculoskeletal concerns in primary care without physician involvement preceding physiotherapy care. NHS England plans to ensure access to advanced-practice musculoskeletal physiotherapists for the entire patient population by 2023.84 In Canada, 14% of medically complex and 14% of high frequency health services users in Manitoba, for example, present to primary care for musculoskeletal concerns.85 Especially in the context of team-based primary care, physiotherapists can make a meaningful contribution to the care of these more complex populations.

In future evaluations of supply-side access interventions, we recommend that researchers attend to how supply-side changes to physiotherapy affect different populations, particularly those that are historically under-served and experience more barriers to access (e.g., geographical, financial, linguistic). This facet of evaluation is important because addressing one dimension of patient-centred access to health care may create new barriers and inequities.13 For example, timely access to medical specialist care, which physiotherapy assessment can support, may improve care for patients who need a medical specialist but leave the remainder without appropriate treatment opportunities, depending on what physiotherapy services are accessible in the local system. In light of the possibility that interventions create new inequities, we see the value of applying the patient-centred model of access to guide evaluation that explicitly considers known or plausible access disparities.

To date, no physiotherapy access studies have either compared the effects of different access strategies or examined combinations of strategies. In addition, the literature provides no clear guidance about what strategies work to address population-level needs. We use strategies, plural, because access is multidimensional and requires systems to create the fit of services with communities. Different communities have different population needs and barriers; thus, no one access strategy will be a best fit for all communities. Attempts to better address access gaps in other health sectors, such as primary care, have led to the design of sophisticated comparative studies across multiple jurisdictions.86 For the profession to begin to fill the large gap in physiotherapy access, we encourage learning from other professions and health system settings to design interventions that enhance the fit of services to the population served while taking into account profession-specific access barriers (e.g., two-tiered physiotherapy care in Canada).

Limitations

This scoping review has some limitations. First, we did not search reference lists or grey literature. We felt it would be difficult to delineate where to search for grey literature, given the many countries and health systems involved and the many publications in English, French, and German, though we recognize that this type of search may yield rich data. Physiotherapists and organizations looking to make local system changes may wish to delve into within-country and more context-specific grey literature to inform their interventions.

Second, we acknowledge the challenges inherent in applying the patient-centred access to health care conceptual framework; for example, we encountered difficulty categorizing direct access as one primary dimension. To manage this difficulty, we chose to focus on the stated purpose of the intervention: That is, which dimension of access did the intervention intend to address? Still, this intent was sometimes hard to ascertain, given the inconsistency within some articles between background information, purpose statements, descriptions of interventions, and outcome measures. Other categorization approaches might have shifted the distribution of dimensions of access addressed. Even if a different categorization approach was used, this would not change the outcomes studies evaluated, which highlight the emphasis on health system priorities rather than equity or patient-centred needs.

Third, we were unable to access five full-text articles to screen for inclusion. Although we were unlikely to include all five, these articles might have complemented our included articles. Finally, we excluded descriptive studies that lacked an evaluation. We recognize that such studies may have implemented additional strategies to improve access, but without evaluation of at least one outcome, we could not know whether such strategies hold promise.

Conclusion

In this scoping review, we applied Levesque and colleagues’14 patient-centred access to health care conceptual framework to identify which supply-side dimensions of access to physiotherapy services were well researched and where gaps in the literature were. To date, the published research as a whole has not evaluated all of the dimensions of patient-centred access equally. The majority of intervention strategies researchers have evaluated focused on (1) appropriateness of services and (2) availability and accommodation to better meet patients’ needs. Notably less research has focused on approachability, acceptability, and affordability. Studies rarely focused on or evaluated the intervention strategies’ impact on known access inequities; thus, the impact of the strategies on access inequities is unclear. This lack of attention to equity is especially relevant in Canada, where current funding constraints and service delivery models have the potential to worsen health inequities. Looking to the future, research on strategies to improve access to physiotherapy should attend to these gaps and use more robust study designs when possible. Without such research, the physiotherapy profession will be unable to demonstrate its value in supporting health system changes that explicitly address the unmet needs of under-served communities.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

In recent years, multiple Canadian jurisdictions have curtailed public funding for outpatient physiotherapy services. In addition, there are geographic disparities in the distribution of physiotherapists. Both factors impact access, potentially creating or worsening inequities in access.

What this study adds

In this scoping review, we highlight five supply-side strategies that can improve access to outpatient physiotherapy services based on a systematic search of published research. We also describe how equity concerns have, or have not, been considered in the empirical evaluations of the strategies and discuss how these strategies fit within a theoretical framework of equitable access to health care. The review can be used to help guide decisions about strategies to consider in local health systems and to inform future research to improve equitable access to physiotherapy for community-dwelling persons.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Richard L, Furler J, Densley K, et al. Equity of access to primary healthcare for vulnerable populations: the IMPACT international online survey of innovations. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15:64. 10.1186/s12939-016-0351-7. Medline:27068028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romanow RJ. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada: final report. Saskatoon (SK): Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Government of Canada . A common statement of principles on shared health priorities; 2018. [cited 2022. Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/health-agreements/principles-shared-health-priorities.html.

- 4.Australian Government, Department of Health . National primary health care strategic framework; 2013. [cited 2022. Feb 4]. Available from: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/nphc-strategic-framework.

- 5.Government of the United Kingdom, Department of Health and Social Care . The NHS Constitution for England; 2021. [cited 2022. Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-nhs-constitution-for-england/the-nhs-constitution-for-england#principles-that-guide-the-nhs.

- 6.Government of the United Kingdom, Department of Health and Social Care . Handbook to the NHS Constitution for England; 2021. [cited 2022. Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/supplements-to-the-nhs-constitution-for-england/the-handbook-to-the-nhs-constitution-for-england#nhs-values.

- 7.Canadian Institute for Health Information . How Canada compares: results from the Commonwealth Fund 2015 international health policy survey of primary care physicians. Ottawa (ON): The Institute; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Health care in Canada, 2012: a focus on wait times. Ottawa (ON): The Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peachey D, Tait N, Adams O, et al. Provincial clinical and preventive services planning for Manitoba: doing things differently and better. Winnipeg (MB): Government of Manitoba, Ministry of Health, Seniors, and Active Living; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Common challenges, shared priorities: measuring access to home and community care and to mental health and addictions services in Canada. Ottawa (ON): The Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Government of Canada . Canada Health Act. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 1985. [cited 1 Mar 2022]. Available from https://canlii.ca/t/532qv. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landry MD, Deber RB, Jaglal S, et al. Assessing the consequences of delisting publicly funded community-based physical therapy on self-reported health in Ontario, Canada: a prospective cohort study. Int J Rehabil Res. 2006;29(4):303–7. 10.1097/mrr.0b013e328010badc. Medline:17106346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skinner EH, Foster M, Mitchell G, et al. Effect of health insurance on the utilisation of allied health services by people with chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust J Prim Health. 2014;20(1):9–19. 10.1071/py13092. Medline:24079301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):18. 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18. Medline:23496984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):429–45. 10.2190/986l-lhq6-2vte-yrrn. Medline:1644507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bath B, Gabrush J, Fritzler R, et al. Mapping the physiotherapy profession in Saskatchewan: examining rural versus urban practice patterns. Physiother Can. 2015;67(3):221–31. 10.3138/ptc.2014-53. Medline:26839448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFadden B, Jones McGrath K, Lowe T, et al. Examining the supply of and demand for physiotherapy in Saskatchewan: the relationship between where physiotherapists work and population health need. Physiother Can. 2016;68(4):335–45. 10.3138/ptc.2015-70. Medline:27904233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grona SL, Bath B, Busch A, et al. Use of videoconferencing for physical therapy in people with musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(5):341–55. 10.1177/1357633x17700781. Medline:28403669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deslauriers S, Raymond MH, Laliberte M, et al. Variations in demand and provision for publicly funded outpatient musculoskeletal physiotherapy services across Quebec, Canada. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(6):1489–97. 10.1111/jep.12838. Medline:29063716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deslauriers S, Raymond MH, Laliberte M, et al. Access to publicly funded outpatient physiotherapy services in Quebec: waiting lists and management strategies. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(26):2648–56. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1238967. Medline:27758150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wojkowski S, Smith J, Richardson J, et al. Scoping review of need and unmet need for community-based physiotherapy in Canada. J Crit Rev. 2016;3(4):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah TI, Milosavljevic S, Trask C, et al. Mapping physiotherapy use in Canada in relation to physiotherapist distribution. Physiother Can. 2019;71(3):213–9. 10.3138/ptc-2018-0023. Medline:31719717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616. Medline:34396482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. Medline:19490148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colquhoun HL, Jesus TS, O’Brien KK, et al. Study protocol for a scoping review on rehabilitation scoping reviews. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(9):1249–56. 10.1177/0269215516688514. Medline:28118743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bramer W, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, et al. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240–3. 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014. Medline:27366130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. Medline:20854677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687. Medline:16204405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portney LG. Foundations of clinical research: applications to evidence-based practice. 4th ed.Philadelphia (PA): F.A. Davis Company; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bath B, Grona SL, Janzen B. A spinal triage programme delivered by physiotherapists in collaboration with orthopaedic surgeons. Physiother Can. 2012;64(4):356–66. 10.3138/ptc.2011-29. Medline:23997390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boissonnault WC, Lovely K. Hospital-based outpatient direct access to physical therapist services: current status in Wisconsin. Phys Ther. 2016;96(11):1695–704. 10.2522/ptj.20150540. Medline:27277495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boissonnault WG, Badke MB, Powers JM. Pursuit and implementation of hospital-based outpatient direct access to physical therapy services: an administrative case report. Phys Ther. 2010;90(1):100–9. 10.2522/ptj.20080244. Medline:19892855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cant RP, Foster MM. Investing in big ideas: utilisation and cost of Medicare Allied Health services in Australia under the Chronic Disease Management initiative in primary care. Aust Health Rev. 2011;35(4):468–74. 10.1071/ah10938. Medline:22126951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawes J, Brydson G, McLean F, et al. Physiotherapy for homeless people: unique service for a vulnerable population. Physiotherapy. 2003;89(5):297–304. 10.1016/s0031-9406(05)60042-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillis K, Augruso A, Coe T, et al. Physiotherapy extended-role practitioner for individuals with hip and knee arthritis: patient perspectives of a rural/urban partnership. Physiother Can. 2014;66(1):25–32. 10.3138/ptc.2012-55. Medline:24719505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanley A, Ali MT, Murphy J. Early experience of a fall and fracture prevention clinic at Mayo General Hospital. Ir J Med Sci. 2010;179(2):277–8. 10.1007/s11845-009-0444-z. Medline:19847591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harland N, Blacklidge B. Physiotherapists and general practitioners attitudes towards “PhysioDirect” phone based musculoskeletal physiotherapy services: a national survey. Physiotherapy. 2017;103(2):174–9. 10.1016/j.physio.2016.09.002. Medline:27913062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holdsworth LK, Webster VS, McFadyen AK. Physiotherapists’ and general practitioners’ views of self-referral and physiotherapy scope of practice: results from a national trial. Physiotherapy. 2008;94(3):236–43. 10.1016/j.physio.2008.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hurtubise K, Shanks R, Benard L. The design, implementation, and evaluation of a physiotherapist-led clinic for orthopedic surveillance for children with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2017;37(4):399–413. 10.1080/01942638.2017.1280869. Medline:28266885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kairy D, Tousignant M, Leclerc N, et al. The patient’s perspective of in-home telerehabilitation physiotherapy services following total knee arthroplasty. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(9):3998–4011. 10.3390/ijerph10093998. Medline:23999548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller Mifflin T, Bzdell M. Development of a physiotherapy prioritization tool in the Baffin Region of Nunavut: a remote, under-serviced area in the Canadian Arctic. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(2):1466. 10.22605/rrh1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mintken PE, Pascoe SC, Barsch AK, et al. Direct access to physical therapy services is safe in a university student health center setting. J Allied Health. 2015;44(3):164–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parfitt N, Smeatham A, Timperley J, et al. Direct listing for Total Hip Replacement (THR) by primary care physiotherapists. Clin Governance Int J. 2012;17(3):210–6. 10.1108/14777271211251327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Passalent LA, Kennedy C, Warmington K, et al. System integration and clinical utilization of the Advanced Clinician Practitioner in Arthritis Care (ACPAC) program-trained extended role practitioners in Ontario: a two-year, system-level evaluation. Healthc Policy. 2013;8(4):56–70. 10.12927/hcpol.2013.23396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pimdee A, Nualnetr N. Applying the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health to guide home health care services planning and delivery in Thailand. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2017;36(2):81–95. 10.1080/01621424.2017.1326332. Medline:28481683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savard L, Borstad A, Tkachuck J, et al. Telerehabilitation consultations for clients with neurologic diagnoses: cases from rural Minnesota and American Samoa. NeuroRehabilitation. 2003;18(2):93–102. 10.3233/nre-2003-18202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevenson K, Hay E. An integrated care pathway for the management of low back pain. Physiotherapy. 2004;90(2):91–6. 10.1016/s0031-9406(03)00009-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moi JHY, Phan U, de Gruchy A, et al. Is establishing a specialist back pain assessment and management service in primary care a safe and effective model? Twelve-month results from the Back pain Assessment Clinic (BAC) prospective cohort pilot study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e019275. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019275. Medline:30309987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Badke MB, Sherry J, Sherry M, et al. Physical therapy direct patient access versus physician patient-referred episodes of care: comparisons of cost, resource utilization & outcomes. HPA Resour. 2014;14(3):J1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bove AM, Gough ST, Hausmann LRM. Providing no-cost transport to patients in an underserved area: impact on access to physical therapy. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;35(7):645–50. 10.1080/09593985.2018.1457115. Medline:29601223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Comans T, Raymer M, O’Leary S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a physiotherapist-led service for orthopaedic outpatients. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2014;19(4):216–23. 10.1177/1355819614533675. Medline:24819380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crowell MS, Dedekam EA, Johnson MR, et al. Diagnostic imaging in a direct-access sports physical therapy clinic: a 2-year retrospective practice analysis. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11(5):708–17. 10.2519/jospt.2005.35.11.708. Medline:16355913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Denninger TR, Cook CE, Chapman CG, et al. The influence of patient choice of first provider on costs and outcomes: analysis from a physical therapy patient registry. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(2):63–71. 10.2519/jospt.2018.7423. Medline:29073842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harding KE, Bottrell J. Specific timely appointments for triage reduced waiting lists in an outpatient physiotherapy service. Physiotherapy. 2016;102(4):345–50. 10.1016/j.physio.2015.10.011. Medline:26725373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harding P, Burge A, Walter K, et al. Advanced musculoskeletal physiotherapists in post arthroplasty review clinics: a state wide implementation program evaluation. Physiotherapy. 2018;104(1):98–106. 10.1016/j.physio.2017.08.005. Medline:28964524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leemrijse CJ, Swinkels ICS, Veenhof C. Direct access to physical therapy in the Netherlands: results from the first year in community-based physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2008;88(8):936–46. 10.2522/ptj.20070308. Medline:18566108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ludvigsson ML, Enthoven P. Evaluation of physiotherapists as primary assessors of patients with musculoskeletal disorders seeking primary health care. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(2):131–7. 10.1016/j.physio.2011.04.354. Medline:22507363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maddison P, Jones J, Breslin A, et al. Improved access and targeting of musculoskeletal services in northwest Wales: Targeted Early Access to Musculoskeletal Services (TEAMS) programme. BMJ. 2004;329(7478):1325–7. 10.1136/bmj.329.7478.1325. Medline:15576743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maeng DD, Graboski A, Allison PL, et al. Impact of a value-based insurance design for physical therapy to treat back pain on care utilization and cost. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1337–46. 10.2147/jpr.s135813. Medline:28615965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mallett R, Bakker E, Burton M. Is physiotherapy self-referral with telephone triage viable, cost-effective and beneficial to musculoskeletal outpatients in a primary care setting? Musculoskeletal Care. 2014;12(4):251–60. 10.1002/msc.1075. Medline:24863858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nucifora J, Howard Z, Jackman A, et al. Outcomes of a physiotherapy-led pelvic health clinic. Aust NZ Continence J. 2018;24(2):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perry M, Featherston S, McSherry T, et al. Musculoskeletal physiotherapy provided within a community health centre improves access. NZ J Physiother. 2015;43(2):40–6. 10.15619/nzjp/43.2.03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith J, Yeowell G, Fatoye F. Clinical and economic evaluation of a case management service for patients with back pain. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(6):1355–60. 10.1111/jep.12797. Medline:28762623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wittmeier KDM, Restall G, Mulder K, et al. Central intake to improve access to physiotherapy for children with complex needs: a mixed methods case report. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):455. 10.1186/s12913-016-1700-3. Medline:27578196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care . What study designs can be considered for inclusion in an EPOC review and what should they be called? 2017. [cited 2022. Feb 4]. Available from: https://epoc.cochrane.org/resources/epoc-resources-review-authors.

- 66.Holland AE, Mahal A, Hill CJ, et al. Home-based rehabilitation for COPD using minimal resources: a randomised, controlled equivalence trial. Thorax. 2017;72(1):57–65. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208514. Medline:27672116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jolly K, Taylor R, Lip GY, et al. The Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation Study (BRUM): home-based compared with hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation in a multi-ethnic population: cost-effectiveness and patient adherence. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(35):1–118. 10.3310/hta11350. Medline:17767899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nordeman L, Nilsson B, Moller M, et al. Early access to physical therapy treatment for subacute low back pain in primary health care: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(6):505–11. 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210696.46250.0d. Medline:16788335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salisbury C, Foster NE, Hopper C, et al. A pragmatic randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of “PhysioDirect” telephone assessment and advice services for physiotherapy. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(2):1–157. 10.3310/hta17020. Medline:23356839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salisbury C, Montgomery AA, Hollinghurst S, et al. Effectiveness of PhysioDirect telephone assessment and advice services for patients with musculoskeletal problems: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f43. 10.1136/bmj.f43. Medline:23360891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Taylor S, Ellis I, Gallagher M. Patient satisfaction with a new physiotherapy telephone service for back pain patients. Physiotherapy. 2002;88(11):645–57. 10.1016/s0031-9406(05)60107-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bishop A, Ogollah RO, Jowett S, et al. STEMS pilot trial: a pilot cluster randomised controlled trial to investigate the addition of patient direct access to physiotherapy to usual GP-led primary care for adults with musculoskeletal pain. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e012987. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012987. Medline:28286331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Holdsworth LK, Webster VS. Direct access to physiotherapy in primary care: now? – and into the future? Physiotherapy. 2004;90(2):64–72. 10.1016/j.physio.2004.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Holdsworth LK, Webster VS, McFadyen AK. What are the costs to NHS Scotland of self-referral to physiotherapy? Results of a national trial. Physiotherapy. 2007;93(1):3–11. 10.1016/j.physio.2006.05.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McNamara RJ, McKeough ZJ, Mo LR, et al. Community-based exercise training for people with chronic respiratory and chronic cardiac disease: a mixed-methods evaluation. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2839–50. 10.2147/copd.s118724. Medline:27895476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Long SH, Eldridge BJ, Harris SR, et al. Challenges in trying to implement an early intervention program for infants with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2015;27(1):38–43. 10.1097/pep.0000000000000101. Medline:25461764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ojha HA, Brandi JA, Finn KM, et al. Cost efficiency of direct access physical therapy for Temple University employees with musculoskeletal injuries. Orthop Phys Ther Pract. 2015;27(4):228–33. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Phillips TD, Shoemaker MJ. Early access to physical therapy and specialty care management for American workers with musculoskeletal injuries. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(4):402–11. 10.1097/jom.0000000000000969. Medline:28628049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pinnington MA, Miller J, Stanley I. An evaluation of prompt access to physiotherapy in the management of low back pain in primary care. Fam Pract. 2004;21(4):372–80. 10.1093/fampra/cmh406. Medline:15249525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stanley I, Miller J, Pinnington MA, et al. Uptake of prompt access physiotherapy for new episodes of back pain presenting in primary care. Physiotherapy. 2001;87(2):60–7. 10.1016/s0031-9406(05)60442-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bath B, Janzen B. Patient and referring health care provider satisfaction with a physiotherapy spinal triage assessment service. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:1–15. 10.2147/jmdh.s26375. Medline:22328826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prvu Bettger J, Resnik LJ. Telerehabilitation in the age of COVID-19: an opportunity for learning health system research. Phys Ther. 2020;100(11):1913–6. 10.1093/ptj/pzaa151. Medline:32814976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. Medline:16202000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chartered Society of Physiotherapy . First contact physiotherapy phase 3 evaluation data; 2020. [cited 2022. Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.csp.org.uk/professional-clinical/improvement-innovation/fcp-phase-3-evaluation-data.

- 85.Chateau D, Katz A, Metge C, et al. Describing patient populations for the My Health Team initiative. Winnipeg (MB): Manitoba Centre for Health Policy; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Russell G, Kunin M, Harris M, et al. Improving access to primary healthcare for vulnerable populations in Australia and Canada: protocol for a mixed-method evaluation of six complex interventions. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e027869. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027869. Medline:31352414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.