Abstract

Baby food marketing poses a substantial barrier to breastfeeding, which adversely affects mothers' and children's health. Over the last decade, the baby food industry has utilised various marketing tactics in Indonesia, including direct marketing to mothers and promoting products in public spaces and within the healthcare system. This study examined the marketing of commercial milk formula (CMF) and other breast‐milk substitute products during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Indonesia. Using a local, community‐based reporting platform, information on publicly reported violations of the International Code of Marketing of Breast‐milk Substitutes and subsequent World Health Assembly resolutions (the Code) was collected. It was found that a total of 889 reported cases of unethical marketing of such products were recorded primarily through social media from May 20 through December 31, 2021. Our results suggest that the COVID‐19 pandemic has provided more opportunities for the baby food industry in Indonesia to attempt to circumvent the Code aggressively through online marketing strategies. These aggressive marketing activities include online advertisements, maternal child health and nutrition webinars, Instagram sessions with experts, and heavy engagement of health professionals and social media influencers. Moreover, product donations and assistance with COVID‐19 vaccination services were commonly used to create a positive image of the baby food industry in violation of the Code. Therefore, there is an urgent need to regulate the online marketing of milk formula and all food and beverage products for children under the age of 3.

Keywords: aggressive marketing, code of marketing, COVID‐19, Indonesia, milk formula, online marketing, pandemic

This study examined the marketing of commercial milk formula and other breast milk substitute products during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Indonesia. The COVID‐19 pandemic has provided more opportunities for the baby food industry in Indonesia to attempt to circumvent the Code aggressively through online marketing strategies.

Key messages

While unethical marketing within the healthcare system and in public spaces remains prevalent, this study showed that in Indonesia, the COVID‐19 pandemic had provided more opportunities for commercial milk formula companies to market their products more aggressively on online social media platforms.

Involvement of healthcare professionals and their associations and social media influencers in marketing activities has been on the rise in violation of the Code.

This study indicated that formula companies offered assistance and donations during the COVID‐19 pandemic while placing their prominent brand identifier at the donation events.

There is an urgent need to regulate the online marketing of commercial milk formula and all food and beverage products for children under the age of 3.

1. INTRODUCTION

Indonesia is among the few Southeast Asian countries with the largest number of new COVID‐19 cases and deaths and the lowest testing rates (Puno et al., 2021). By the end of December 2021, the country reported a total of 4,262,720 cases with at least 144,094 COVID‐19‐associated deaths (World Health Organization, 2021). As part of the disease‐containment measures, the government of Indonesia implemented numerous health protocols, including large‐scale social restrictions and restrictions on social activity from March 2020 to December 2021. Consequently, there was a substantial decline in people's mobility, and most activities were done from home.

Breastfeeding plays a critical role in ensuring the health and survival of children. Researchers have found that it can protect children and their mothers from numerous illnesses and diseases (Victora et al., 2016). In Indonesia, when breastfeeding is inadequately practised, the health costs are significantly high for the government, at approximately US$118 million annually (Siregar et al., 2018). Moreover, recommended breastfeeding reduces the risks of morbidity and mortality. When practised optimally, it could save the lives of more than 5350 children and mothers in Indonesia or reduce almost half of the total number of maternal and child deaths in Southeast Asia every year (Walters et al., 2016). At the global level, it has been estimated that over 820,000 deaths of children younger than 5 could have been prevented by recommended breastfeeding (Victora et al., 2016). According to the WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) recommended breastfeeding implies that babies should be breastfed within the first hour after birth, exclusively for the first 6 months, and for an additional 18 months or longer, along with adequate complementary foods (World Health Organization, 2003).

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, the protective benefits that breastfeeding offers seem to be more crucial than ever; indeed, researchers have found that breastfeeding reduces the infection risk among young children (Verd et al., 2021). Recent studies have suggested that COVID‐19 is not transmitted through breast milk (Krogstad et al., 2021). Furthermore, there is strong evidence that secretory immunoglobulins A (IgA) and G (IgG) are present in the breast‐milk of mothers who have had COVID‐19 or received a COVID‐19 vaccine, suggesting a potential protective effect against infection in infants (Fox et al., 2020; Perl et al., 2021; Ramírez et al., 2021). Recognising the protective benefits of breastfeeding against severe COVID‐19 infection in young children, the risks of morbidity and mortality associated with suboptimal breastfeeding, and the inappropriate use of infant milk formula, WHO and UNICEF continue to recommend breastfeeding accompanied by the guidelines for appropriate precautions regarding mothers with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2020).

Despite clear WHO and UNICEF recommendations, the efforts to undermine breastfeeding practices have persisted and even proliferated in recent decades. These efforts have mainly been driven by the aggressive marketing practices of companies that produce milk formula and other products intended to replace breast milk. The marketing activities and messaging of these companies have resulted in increased product sales and are currently worth some US$55 billion (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2020). Compared with other commodities, the sales of baby milk formula have shown constant resilience to market downturns (Rollins et al., 2016). When the global growth of real gross domestic product turned negative in 2014, CMF sales continued to climb, growing by 8% that year to reach an estimated US$44.8 billion (Rollins et al., 2016).

In the developing nation of Indonesia, the size of the CMF market has expanded recently; for instance, from 2009 to 2014, its value grew by 96% (Vinje et al., 2017). The total value of all CMF sales in Indonesia in 2014 was approximately US$240 million (Rollins et al., 2016); in 2022, it skyrocketed to about US$2.8 billion (Statista, 2020). In the future, growth is projected to continue, with the market likely to reach a value of over US$5.1 billion by 2024 (Research and Markets, 2019). These large sales reflect successful marketing, which raises concern because, simultaneously, there has been a distinct change in infant and young child feeding patterns (Baker et al., 2016). According to the 2018 National Health Survey (Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan, 2019), infant formula consumption is the most frequent reason for exclusive breastfeeding disruption (81.4%). In addition, national data show a decline in exclusive breastfeeding from 2018 (74.5%) to 2021 (52.5%) (MoH, 2022).

Unlike other commodities, the marketing of CMF products interrupts recommended breastfeeding practices, adversely affecting maternal and child health and survival (Johnson & Duckett, 2020; Piwoz & Huffman, 2015; Rollins et al., 2016). Recognising this fact, the World Health Assembly (WHA) adopted the International Code of Marketing of Breast‐milk Substitutes in 1981 (World Health Organization, 1981) and its subsequent WHA resolutions in response to the need for global regulation of the aggressive promotion and marketing of products that directly compete with breastfeeding (International Code Documentation Centre [ICDC], 2008). Hereafter, the International Code of Marketing of Breast‐milk Substitutes and the subsequent WHA resolutions are collectively referred to as ‘the Code’, which calls for adherence by member countries.

1.1. The code and subsequent WHA resolutions

The ultimate objective of the Code is to prohibit any form of marketing of milk formula and other breast‐milk substitute products that undermine breastfeeding by describing the government's responsibilities, the healthcare system, health professionals and milk formula companies (World Health Organization, 1981). Following the adoption of WHA Resolution 58.32 (World Health Organization, 2005) and Resolution 63.23 (World Health Organization, 2010), the Code further prohibited companies from making unsubstantiated nutrition‐ and health‐related claims about milk formula and all breast‐milk substitutes and from providing financial support for programs and healthcare professionals working in infant and young child health that can create a conflict of interest (World Health Organization, 2005, 2010). Additionally, through WHA Resolution 69.9 (World Health Organization, 2016b), the Assembly called for manufacturers to end inappropriate, unethical and aggressive marketing practices of all foods for infants and young children aged 6–36 months (World Health Organization, 2016b).

Although the WHA Resolution 62.23 (World Health Organization, 2010) explicitly states that Member States are urged to strengthen legislation to control the marketing of breast‐milk substitutes, the government of Indonesia has not made substantial progress in reinforcing national regulations to give effect to the Code and relevant subsequent WHA resolutions. To date, Indonesia has partially adopted the Code (World Health Organization, 2022b) in its National Health Law No. 36/2009 and Food Labels and Advertising Government Decree (PP 69/1999). However, the National Health Law only provided some degree of protection for exclusive breastfeeding (Article 128), including penalties for a maximum of 1 year and fines up to IDR 100 million (USD 6 670) for those who intentionally discourage breastfeeding (Article 200). To guide the law implementation, a set of sub‐regulations was issued, including a Government Decree (PP 33/2012) on Exclusive Breastfeeding, along with its subsequent Ministry of Health regulations on milk formula, labelling and advertising, which incorporated some of the Code provisions. However, they only protect exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life.

Moreover, the Government Decree (PP 69/1999) on Food Labelling and Advertisement includes an element that prohibits the advertising of milk formula for infants aged 0–12 months. Although it covers broader products for up to 1 year of age, the decree has a lower possible fine of IDR 50 million (USD 3 204) than PP 33/2012 on Exclusive Breastfeeding.

Forty years after the Code adoption, unethical marketing practices of CMF companies have continued to evolve and have become increasingly sophisticated, exerting a powerful influence on families’ infant and young child feeding decisions (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2022). Recently, multinational CMF corporations have capitalised on the COVID‐19 pandemic to increase their sales. In direct violation of the Code, they have frequently and inappropriately presented themselves as public health and nutrition experts (Bhatt, 2020; Tulleken et al., 2020). Furthermore, milk formula companies have made unsubstantiated and misleading claims that their products can help combat COVID‐19 in babies or have donated their products to people affected by the pandemic along with the companies’ brand identifiers to bolster their public image (Ching et al., 2021). Clearly, the current global public health crisis has provided more opportunities for CMF companies to influence infant and young child‐feeding practices. To that end, this study examined how CMF companies marketed their products during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Indonesia, describing the marketing tactics used by baby food manufacturers according to the Code from May through December 2021.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data sources

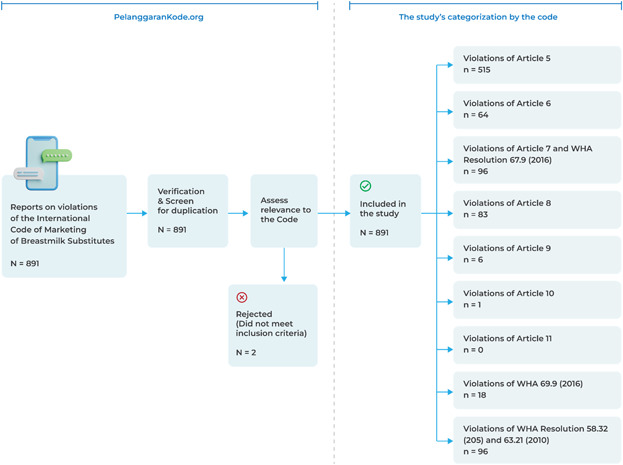

This study applied a concurrent mixed‐method design with a qualitative element providing context for descriptive quantitative components. Furthermore, it used data and information received from a platform called Pelanggaran Kode.org (PK) from May until December 31, 2021, in Indonesia (Pelanggaran Kode, 2020). PK is a local, community‐based reporting platform that receives and collects information on any violations of the Code reported by members of the public via an encrypted instant messaging platform: WhatsApp chatbot. Through regular social media promotion, people were encouraged to voluntarily report any instances of unethical marketing of CMF and other breast‐milk substitute products. For this study, researchers screened all reports to eliminate duplication and then ensured that they were relevant to the Code, before categorising them according to the Code articles and subsequent WHA resolutions (see Figure 1). Of the 891 total reports submitted to PK, 889 (N = 889) were found to be Code violations. The inclusion criteria were all reports showing marketing activities that violated the Code. Recognising the substantial national policy gap in Code provision, this study focused only on the Code, excluding national regulations.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study process.

Violation analysis was conducted in two steps. First, all eligible reports were categorised into the most appropriate articles to quantify the violation of each article and subsequent WHA resolutions. Next, because we found many types of violations in a single report, a directed approach of content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) was used to identify, describe and group multiple types of violations within each article or WHA resolution. The first and second authors were the primary coders who analysed keywords and/or images in each report relevant to each article and WHA resolution. Two coauthors then reviewed the data to ensure the reliability of the data yielded by the primary coders. The last step of the qualitative analysis was debriefing with three experts familiar with the study topic to ensure the analysis's validity.

2.2. Pelanggaran kode reporting platform

Established at the end of 2020, the PK platform is managed collectively by local breastfeeding advocacy networks in Indonesia, including the Indonesian Breastfeeding Mothers Association (AIMI), Breastfeeding Father Support group (Ayah ASI), and maternal and child health and nutrition advocacy group (GKIA). The platform received reports through a chatbot (WhatsApp) with a 23‐item questionnaire to identify the unethical marketing of CMF and all breast‐milk substitute products. The questions assessed a brief demographic characteristic (three questions), 17 types of Code violations, a description of violations, the location where the violation occurred (one question), and supporting documentation of violations (two questions). The questions were pilot tested and validated by local experts before the PK launch. Data collection contained respondents’ cell phone number information, which was protected by the platform system. This study is the first report‐generated platform, to the best of our knowledge.

3. RESULTS

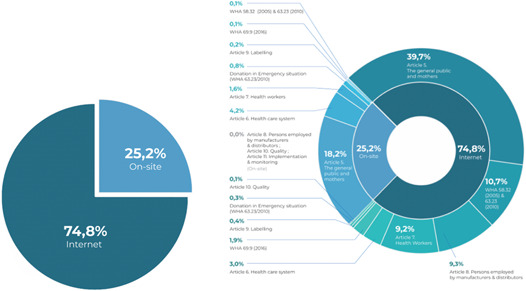

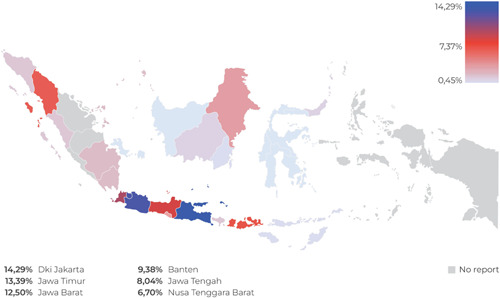

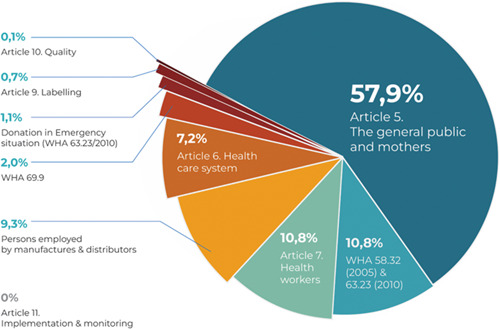

There were a total of 889 Code‐prohibited instances of marketing milk formulas for infants and young children, complementary foods, bottles, bottle nipples, and any foods and beverages for children aged 0–36 months from May through December 2021, with most of the reported violations (74.8%, or n = 665) occurring on the Internet (see Figure 2). As shown in Table 2 and Figure 3, of the 25.2% of on‐site violations, 32 occurred in the capital city of Jakarta (14.29%), West Java (12.5%), and Central Java (8.04%). As shown in Figure 4 and Table 1, marketing activities to the public were the most common type of reported violations (n = 515, 57.9%), followed by marketing practices involving health professionals (n = 96, 10.8%) and using health and nutrition claims (n = 96, 10.8%). Promotions of CMF by persons hired by CMF companies (n = 83 or 9.3%) and within the health system (n = 64 or 7.2%) were also among the most frequent Code circumventions.

Figure 2.

Comparison of reported on‐site and Internet violations.

Table 2.

On‐site location.

| Provinces | Violations (%) |

|---|---|

| Dki Jakarta | 14.29 |

| Jawa Timur | 13.39 |

| Jawa Barat | 12.50 |

| Banten | 9.38 |

| Jawa Tengah | 8.04 |

| Other locations | 42.41 |

| Total | 100.00 |

Figure 3.

Geographical location of the violation reports.

Figure 4.

Total reported violations based on the code articles and WHA resolutions.

Table 1.

Summary of reported code violations.

| Code article | Violations to the international code | Place | n | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet | On‐site | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Article 5. The general public and mothers | 5.1 Promotion to the general public | 105 | 11.8 | 27 | 3.0 | 132 | 14.8 |

| 5.2 Sample distribution | 29 | 3.3 | 12 | 1.3 | 41 | 4.6 | |

| 5.3 Point‐of‐sale advertising, giving of samples, or any other promotion device, special displays, discount coupons, premiums, special sales, loss‐leaders and tie‐in sales | 126 | 14.2 | 17 | 1.9 | 143 | 16.1 | |

| 5.4. Gifts distribution to mothers | 41 | 4.6 | 11 | 1.2 | 52 | 5.8 | |

| 5.5. Direct contact with mothers | 52 | 5.8 | 95 | 10.7 | 147 | 16.5 | |

| Subtotal | 353 | 39.7 | 162 | 18.2 | 515 | 57.9 | |

| Article 6. Health care system | 6.1 Promotion at hospitals, health clinics and other health facilities | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.4 |

| 6.3 Display of products within the scope of the Code (placards or posters concerning such products, or for the distribution of material provided by a manufacturer or distributor) | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.4 | |

| 6.4 The use by the health care system of ‘professional service representatives’, ‘mothercraft nurses’ or similar personnel provided or paid for by manufacturers or distributors | 20 | 2.2 | 10 | 1.1 | 30 | 3.4 | |

| 6.6 Donations or low‐price sales to institutions or organisations of supplies of infant formula or other products within the Code scope | 7 | 0.8 | 13 | 1.5 | 20 | 2.2 | |

| 6.8 Equipment and materials donated to a health care system that refers to any proprietary product within the Code scope | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.7 | 6 | 0.7 | |

| Subtotal | 27 | 3.0 | 37 | 4.2 | 64 | 7.2 | |

| Article 7. Health workers | 7.2 Manufacturers provide information that creates a belief that bottle‐feeding is equivalent or superior to breastfeeding | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.2 |

| 7.3 Manufacturers or distributors provide financial or material inducements to promote products to health workers | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.2 | |

| 7.4 Health workers provide samples of infant formula to pregnant women, mothers of infants and young children, or members of their families | 1 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.6 | |

| 7.5 Undisclosed support by manufacturers for fellowships, study tours, research grants, attendance at professional conferences, or the like to health workers | 81 | 9.1 | 6 | 0.7 | 87 | 9.8 | |

| Subtotal | 82 | 9.2 | 14 | 1.6 | 96 | 10.8 | |

| Article 8. Persons employed by manufacturers and distributors | 8.2 Persons employed by manufacturers perform educational functions in relation to pregnant women or mothers of infants and young children | 83 | 9.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 83 | 9.3 |

| Subtotal | 83 | 9.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 83 | 9.3 | |

| Article 9. Labelling | 9.1 Labels do not provide information about the appropriate use of the product | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 9.2 A clear, conspicuous, easily readable and understandable message printed on the label | 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.3 | |

| 9.3 Statement warning that the product is the sole source of nourishment for an infant | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 9.4 Clear information on the product compositions, ingredients, storage requirements, batch number and taking into account the climate of the country concerned | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.3 | |

| Subtotal | 4 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.2 | 6 | 0.7 | |

| Article 10. Quality | 10.2 Food products meet applicable standards recommended by the Codex Alimentarius Commission and the Codex Code of Hygienic Practice for Foods for Infants and Children | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Subtotal | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Article 11. Implementation and monitoring | Article 11. Implementation and monitoring | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Donation in emergency situation and WHA 63.32 (2010) | Supplies or donations by manufacturers during emergency situations | 3 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.8 | 10 | 1.1 |

| WHA 69.9 (World Health Organization, 2016b) | Marketing products for children aged 6–36 months | 17 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.1 | 18 | 2.0 |

| WHA 58.32 (2005); 63.32 (World Health Organization, 2010) | The use of unsubstantiated health and nutrition claims | 81 | 9.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 82 | 9.2 |

| 14 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 1.6 | ||

| Subtotal | 95 | 10.7 | 1 | 0.1 | 96 | 10.8 | |

| Grand total | 665 | 74.8 | 224 | 25.2 | 889 | 100.0 | |

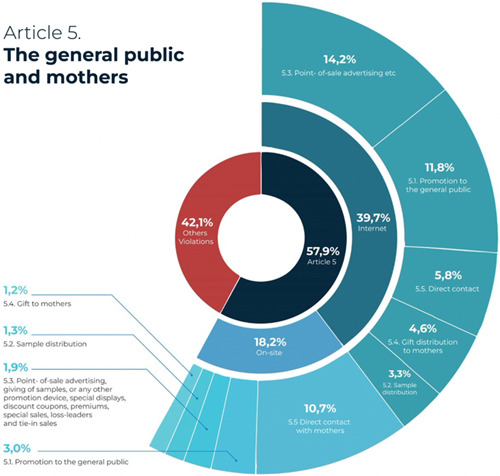

3.1. Reported violations of Article 5: Promotion to the general public

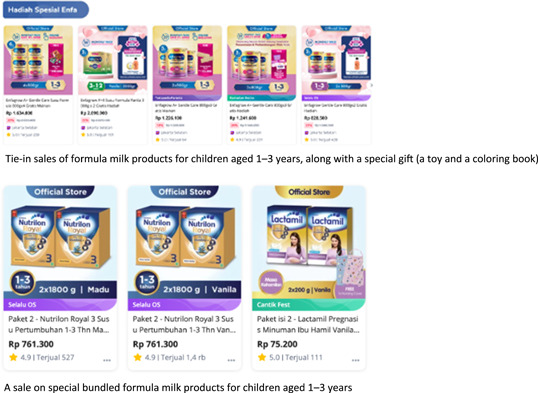

More than half of the reported incidents (57.9%) involved promotion to the public, which is prohibited by Article 5 of the Code. As shown in Figure 5, out of 515 reported incidences of CMF marketing to the public, 147 involved sales personnel directly contacting mothers through private messages on Instagram and Facebook, WhatsApp chats text messages and direct calls to mobile phones. Another 143 reports showed point‐of‐sale advertising, discounted or special prices, bundling and tie‐in sales of CMF products that the Code explicitly prohibits. Moreover, people found and reported 132 CMF online and offline advertisements in public spaces.

Figure 5.

Reported violations of Article 5: Promotion to the general public.

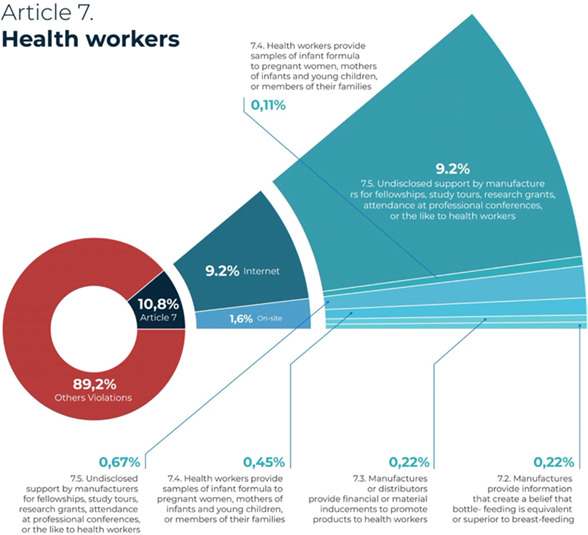

3.2. Reported violations of Articles 6 and 7: Healthcare systems and health workers

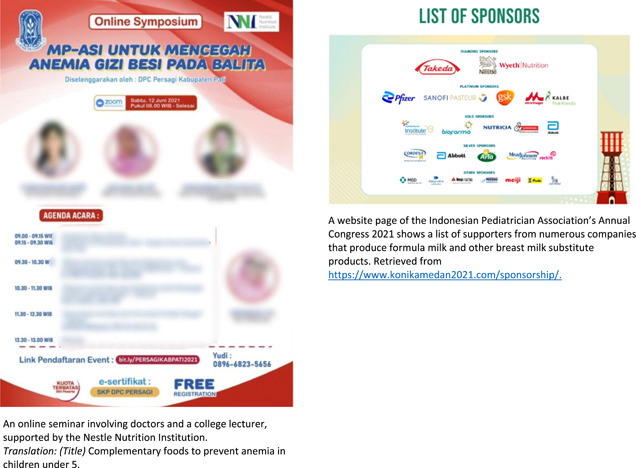

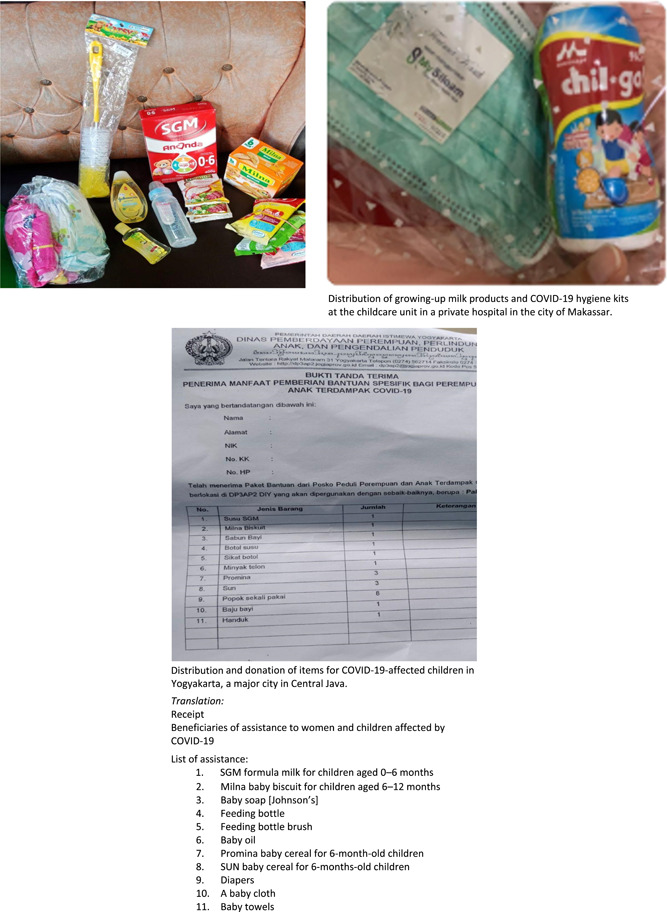

There were 64 incidences of promotion of CMF and other products within the scope of the Code in a healthcare facility. Among those cases, the facilities were used for company‐sponsored infant feeding‐related seminars (n = 30), in which companies made CMF donations to healthcare facilities in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic (n = 20).

A total of 96 (or 10.8%) marketing practices were reported that involved marketing through healthcare workers, which is prohibited by Article 7 of the Code. Overall, 87 of these violations were in the form of sponsorship of a conference or workshop, and the rest involved practitioners’ distribution of CMF or complementary foods to mothers. Of the 96 reports on marketing that involved health professionals, the majority were from the Internet (n = 82) and 14 occurred on‐site (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Reported violations of Article 7: Health workers.

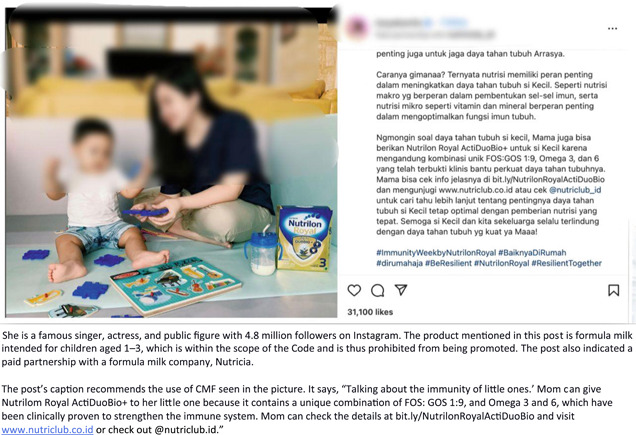

3.3. Reported violations of Article 8: Persons employed by CMF companies

People reported a total of 83 online educational sessions focusing on health and infant and young child feeding activities performed by persons hired by milk formula companies, distributors, or their affiliations. Figure 7 shows examples of promotions of products within the scope of the Code, along with health and nutrition education captions posted by social media influencers (SMIs) on their Instagram accounts in violation of Article 8. People reported numerous SMIs posting promotional materials for CMF within the scope of the code, being speakers at company‐sponsored health‐related events and conveying educational information regarding maternal health, child health and nutrition‐related topics.

Figure 7.

Sample of social media influencers promoting products within the scope of the code.

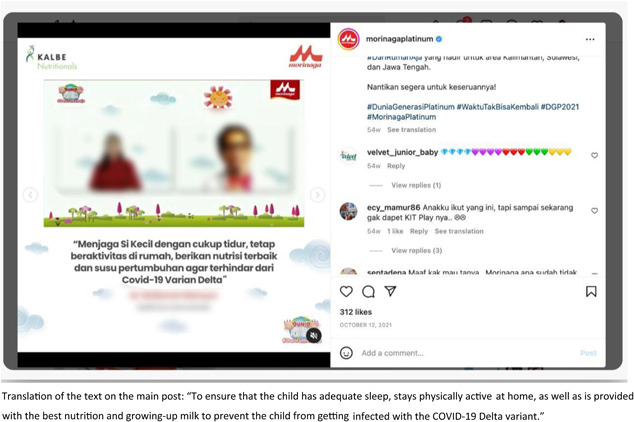

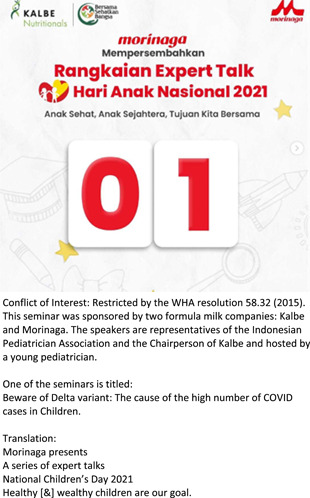

3.4. Violations of relevant WHA resolutions

There were a total of 96 reported instances of marketing activities that included health and nutrition claims, mostly on social media, in violation of WHA 58.32 (World Health Organization, 2005) and 63.23 (World Health Organization, 2010). The reports indicated promotion using words such as immunity, resilience, infection, and respiratory diseases, claiming that the products could prevent infants from contracting an infection. Some of the reported marketing activities did not explicitly mention the correlation between the product and COVID‐19 in the caption; however, they included some hashtags that referred to the COVID‐19 pandemic health protocol, such as #newhabitadaptation, #newnormal and #stayathome. Others were explicitly correlated with COVID‐19. For example, an Instagram post on the Morinaga Platinum account showing a video clip of a talk from a doctor stating to ‘ensure that the child has an adequate sleep, stays physically active at home and is provided with the best nutrition and growing‐up milk to prevent from getting the COVID‐19 Delta variant’ as shown in Figure 8. Similarly, another report shows an article edited by a doctor on the Growhappy of Nestle Indonesia's website, emphasising the importance of milk consumption in maintaining a child's immune system. This article highlights the crucial nutrient composition to help boost immunity in Lactogrow 3, a CMF for children aged 1–3 years, which includes inulin, Limosilactobacillus reuteri, 13 vitamins, and seven minerals. At the end of the article, the author recommends using Lactogrow 3 to improve nutrition and immunity in children.

Figure 8.

Examples of COVID‐19‐related claims.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Aggressive online marketing

This study found that the CMF industry engaged in intensive and aggressive marketing practices in Indonesia during the COVID‐19 pandemic. While the marketing of milk formula and other products within the scope of the Code has been endemic for over four decades (Baby Milk Action UK, 2017; Brady, 2012; Hidayana et al., 2017; Taylor, 1988), the pandemic has provided more opportunities for evolving promotional tactics in Indonesia. This study indicated that despite aggressive marketing practices in public spaces, retail shops and healthcare facilities remaining prevalent (n = 224, or 24.20% of reported incidences), the majority of unethical reported marketing (n = 665, or 74.80%) was conducted via the Internet. It is important to note that since the beginning of the pandemic, there has been evidence of a diverse array of Code‐violating marketing activities becoming more prevalent on online platforms (Asosisasi Ibu Menyusui Indonesia AIMI, 2021). Consistent with the recent WHO report on digital marketing practices by CMF companies (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2022), this study indicated that the heavy use of social media, combined with the stay‐at‐home order as a COVID‐19 containment measure, offered companies more opportunities to aggressively market CMF and all breast‐milk substitute products in a highly targeted manner.

The frequent use of free online platforms such as Instagram and Facebook, as well as WhatsApp instant messaging, as marketing channels to promote their products echoes the findings of previous research by Senkal and Yildiz (2019), who noted that companies commonly use Instagram to promote CMF products through the platform's three main features: feed, story, private message and Instagram Lives. Consistent with evidence from previous research (Asosisasi Ibu Menyusui Indonesia [AIMI], 2021; Ching et al., 2021; World Health Organization, 2020, 2022a; World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2022), this study identified the heavy use of online platforms as marketing media. Frequently, companies reached out to mothers and hosted online seminars, workshops, or talks with doctors, midwives, nurses, nutritionists and company representatives who were presented as experts on a wide range of maternal and child health and nutrition issues.

4.2. Online marketing: SMIs and online shopping

In 83 identified instances of online CMF marketing, celebrities or SMIs were involved. Such instances are known as influencer marketing, in which companies repeatedly approach and hire SMIs to endorse, advertise and promote products or ideas on their social media account because they appear to influence their followers (De Veirman et al., 2017). In the various instances identified in this study, SMIs posted promotional materials for CMF within the scope of the Code, served as speakers at company‐sponsored events, and conveyed educational information about maternal health, child health and nutrition‐related topics. Clearly, such activities violate Article 8.2 of the Code, which prohibits any person employed by a company or entity to promote any products covered by the Code to perform any educational function (Shubber, 1998). These SMIs, who are paid by manufacturers to promote their products, should be treated as personnel employed in the marketing of products within the scope of the Code, who are restricted by Article 8.2 for any promotion activities. Moreover, such practices are prohibited by WHA Resolution 69.9 (World Health Organization, 2016b), which calls for an end to marketing all complimentary food and milk products for children under the age of 3 (World Health Organization, 2016b). CMF companies’ use of paid SMIs is considered an effective way to achieve marketing goals because these influencers’ interactions with their followers are more engaging and personalised than those involving a company (Becker et al., 2022).

Moreover, this study found a total of 143 instances of marketing activities using online shopping platforms, an indicator that CMF companies see these as promising marketing tools. This also suggests that COVID‐19 social distancing and mobility restrictions in many areas of Indonesia have intensified people's shift toward online purchasing and have allowed online shopping platforms to circumvent the Code. Frequently, the shopping site will place a long narrative containing unsubstantiated and misleading health and nutritional claims related to immunity within the product description. In many cases, as in Figure 9, they also use applied marketing tactics, such as specific discounts, special sales, loss leaders, and tie‐in sales, restricted by Article 5 of the Code (Asosisasi Ibu Menyusui Indonesia AIMI, 2021; Becker et al., 2022). As indicated in Figure 3, a relatively high number (n = 143) of the incidences reported in this study involved discounts on all types of CMF products, point‐of‐sale advertising, giving out free samples, cross‐promotion, or another type of direct‐to‐consumer promotion at the retail level; of these, 88% occurred in online shops.

Figure 9.

Geographical location of the violation reports.

Such marketing strategies are clearly prohibited by Article 5.5 and the WHA Resolution 69.7 (2016a), which particularly prohibits any cross‐promotion or brand stretching where customers of one product or service are targeted with the promotion of a related product (World Health Organization, 2016a). Nevertheless, while Resolution 69.7 (2016a) and Article 5.5 of the Code prohibit cross‐promotion, special displays, discount coupons, premiums, special sales, loss leaders, and tie‐in sales for formula products, there has been no subsequent WHA resolution pertaining to these practices on Internet shopping platforms. This finding highlights the urgent need to fully implement the Code on online channels saturated by rambunctious unethical marketing activities. It should be noted that the Code prohibits all forms of marketing of all products that are specially geared toward feeding infants and young children up to the age of 3, meaning it does not exclude online marketing. WHA Resolution 69.7 clearly prohibits online marketing (World Health Organization, 2016a). Moreover, as such products play a critical role in the development of young children, safeguarding their health against unethical marketing practices on digital platforms should be a top priority for member states, including Indonesia (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2022).

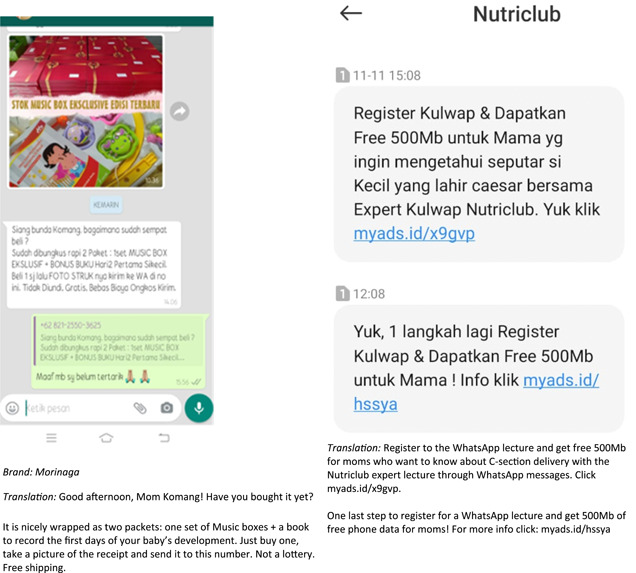

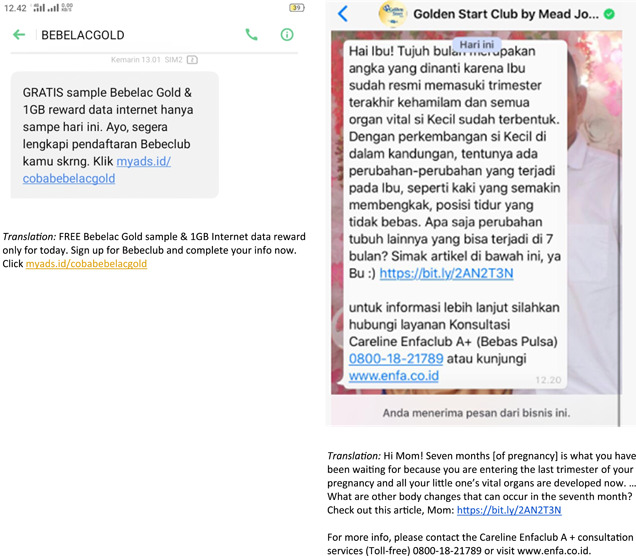

4.3. Direct contact with mothers

Another important finding of this study is the number of reported instances in which companies directly reached out to mothers. Despite being prohibited by Article 5.5, making direct contact continues to be one of the main strategic tools that formula sales personnel use to build relationships with mothers and thus make them dependent on their products (Figure 10). This study found a total of 147 reports of direct contact between CMF companies and mothers: online through private messaging on Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, text messages and direct calls to mobile phones. Some specifically promoted a discounted product to purchase, which demonstrated a more direct approach or a ‘hard sell’, recommending the use of a specific product or brand and emphasising sales orientation (Okazaki et al., 2010). In other cases, salespeople indirectly approached mothers by encouraging them to join a series of online lectures on pregnancy, infant feeding, and child development, which reflected a ‘soft sell’ marketing strategy. This finding echoes an earlier study showing that formula companies market a wide variety of milk products at every stage, from pregnancy milk to infant formula and follow‐on, toddler and growing‐up milk (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2022). Moreover, direct contact with mothers through online messaging services evades scrutiny from public and regulatory authorities (Jones et al., 2022). Consistent with previous research from Hastings et al. (2020), the use of these approaches suggests that companies are employing both a hard sell and a soft sell to build a faux relationship between themselves and mothers in efforts to maintain product sales.

Figure 10.

Examples of direct contact with mothers.

4.4. Engaging health professionals

Although Article 7 of the Code and its WHA Resolution 67.9 (World Health Organization, 2016b) prohibits such practices, this study identified a total of 96 cases in which healthcare professionals were involved in an array of marketing activities, from company‐sponsored seminars to milk formula distribution. There were a total of 87 seminars reported supported by CMF companies that featured healthcare providers, 81 of which were conducted online. Most were focused on a wide range of topics related to maternal and child health, infant and young child feeding, parenting and COVID‐19. Such events represent clear attempts to circumvent the Code and, more specifically, subsequent WHA Resolution 67.9 (World Health Organization, 2016b), which thoroughly details the prohibition of health professionals and their health associations from engaging in any activities supported by baby food companies (World Health Organization, 2016a). Evidently, such marketing activities reflect companies’ conflicting interests by employing indistinguishable colourizations of the event's promotional materials from their products (Berry et al., 2010). Using tactics such as these in their designs is another way for corporations to promote entire lines of their milk formula products, including maternal, infant, follow‐on, toddler and growing‐up formulas (Berry et al., 2012a, 2012b; Cattaneo et al., 2014). Moreover, many seminars or talks reported in this study included the phrase ‘breast milk is best’, to be seen as their support for breastfeeding and compliance with the Code. However, using such a statement is a clever marketing tactic; it could present companies with a positive image, suggesting that their materials are aligned with WHO recommendations (Hastings et al., 2020).

One of the incidences reported was an online talk co‐hosted by the Indonesian Pediatric Society and Kalbe Nutritional, a local formula company that partnered with the Japan‐based company Morinaga to produce and sell various CMF products. During the event, the doctors involved were presented as expert sources of information as they discussed the Delta variant and COVID‐19 cases in children. This finding echoes a previous study showing that paediatric associations regularly received financial support from CMF companies to sponsor conferences and meetings (Grummer‐Strawn et al., 2019). Incentivizing healthcare professionals to speak at a formula company‐sponsored event is highly problematic; it creates a conflict of interest, which is why WHA Resolution 58.32 (World Health Organization, 2005) prohibits it. In addition, numerous CMF companies sponsored the 18th Indonesian Congress of Paediatrics, suggesting that another subtle marketing strategy was at play: portraying the companies as supportive of breastfeeding and child health and development (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2022). However, their participation could adversely affect the adoption of breastfeeding and other recommended infant and young child feeding practices (Piwoz & Huffman, 2015).

Recently, the baby food industry has systematically targeted healthcare professionals to convey information regarding particular CMF products (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2022). Companies involving doctors, midwives and other healthcare professionals in their advertising practices are attempting to depict themselves (through their products) in a positive light because medical providers are typically seen as trusted sources of health advice, including advising that formula is safe or recommending a certain brand to use, which adversely affects infant feeding decisions (Gage et al., 2012; Piwoz & Huffman, 2015; Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Sample of online classes or seminars offered by commercial milk formula companies that involved healthcare professionals.

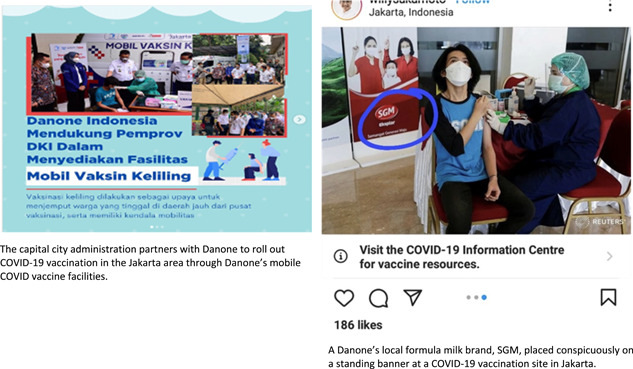

Finally, this study's findings raise another concern, specifically, the veiled marketing that the companies engage in by offering assistance and donations during the COVID‐19 pandemic. There were 20 identified cases of donations from CMF companies to healthcare facilities, billed as part of their COVID‐19 response, among those reported via PK; in these cases, companies offered numerous items from their lines of milk formula and complementary foods alongside regular food items and COVID‐19 hygiene kits. In one instance, Danone provided assistance in rolling out the national COVID‐19 vaccination program while placing prominent standing and digital banners bearing their milk formula brand identifier at the vaccination site (see Figure 12). The use of these unethical marketing practices suggests that companies have used the COVID‐19 pandemic to bolster their profits. Indeed, providing assistance to public health programs is not a new practice for CMF companies. Previously, using Indonesia's national stunting problem as its vehicle, Danone supported a health and nutritional education program for infants younger than 2. In doing so, they placed brand identifiers in the program materials, manipulating their image for marketing purposes through nutritional assistance (Hidayana, 2015). Donation inflicts an obligation to reciprocate, which is potentially harmful to successful breastfeeding (IBFAN‐ICDC, 2018). Recognising this dependency effect, Article 6.6 of the Code and WHA Resolution 47.5 (World Health Organization, 1994) prohibited donations of CMF products that substitute breast‐milk in healthcare facilities and during emergencies (World Health Organization, 1994).

Figure 12.

Sample of ‘faux’ assistance and donations during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

4.5. Limitations

This study might not have captured every instance of the CMF industry's unethical marketing practices across Indonesia, as data were collected via a crowd‐based reporting platform and relied on what was voluntarily reported by members of the general public. Therefore, it affects the distribution and nature of reports and thus cannot reflect the full extent and range of marketing activities. This study might contain duplicated reports where one report has multiple violations of the Code; thus, a more exhaustive content analysis approach is required for future research to investigate the scale and magnitude of Code violations. Additionally, due to the substantial national regulation gaps in Code provisions, the focus on the Code and the exclusion of national regulations should be noted as another limitation of this study.

5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study illustrates the aggressive marketing of milk formula and other products within the scope of the Code during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Indonesia. Despite aggressive advertising within the healthcare system and public spaces, companies’ marketing efforts on social media and online shopping platforms have been intensifying. CMF milk companies frequently engage healthcare professionals and SMIs in marketing activities. Moreover, companies often donate CMF products alongside COVID‐hygiene‐related items and vaccination services. This study highlights the need for stronger national policies that fully adopt the Code to end the unethical marketing of CMF and all food and beverage products for children under the age of 3 in all forms, specifically online marketing. Moreover, the findings of this study resonate with the need for a new WHA or higher approach that specifically addresses digital marketing and conflicts of interest in the health system. Further research is required to continue documenting the formula industry's evolving marketing strategies and analyse and explore the relationship between the prevalence of aggressive marketing and infant‐feeding practices in ways that negatively impact mother–child health outcomes.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Irma Hidayana led the development of the protocol, reporting the methods of the review, and overall coordination for writing the paper; Lianita Prawindarti and Nia Umar made substantial contributions to the data collection and the review of the results. Fitria Rosatriani verified the collected data; Kusmayra Ambarwati carried out screening and recategorizing of all data collected. All authors participated in discussions, reviewed, and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Asosiasi Ibu Menyusui (AIMI), AyahASI ID, Gerakan Kesehatan Ibu dan Anak (GKIA), and St. Lawrence University for their overall support in this publication. We are indebted and would like to thank Sonny Prayogo, Fikry Nashiruddin, and Fakhriy Fathur Rohim for their significant contribution to the development of the PelanggaranKode platform; Yemiko Happy and Rahmat Hidayat, for their support in data collection; and Sri Sukotjo of UNICEF Indonesia for her technical input and support for the reporting platform and the manuscript. We thank Patti Rundal and David Clark for their valuable feedback for improving this manuscript. We would also like to thank colleagues for their feedback and edit: Michael Garcia of Clarkson University, NY, USA and Mindy Pitre, Aswini Pai, and Adam Harr of St. Lawrence University, NY, USA. Finally, we thank Utami Roesli and Tan Shot Yen for their valuable support of the study. The development of the reporting platform, PelanggaranKode, was supported by UNICEF Indonesia, however, it had no role in the analyses or interpretation of data. The views and opinions set out in this article represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the donor.

Hidayana, I. , Prawindarti, L. , Umar, N. , Ambarwati, K. , & Rosatriani, F. (2023). Marketing of commercial milk formula during COVID‐19 in Indonesia. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 19, e13491. 10.1111/mcn.13491

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in an Indonesian‐based community reporting platform, Pelanggaran Kode, at https://pelanggarankode.org/en/statistik. Images of online content and the data that support the findings of this study are openly available and accessible to the public at https://pelanggarankode.org/en/statistik.

REFERENCES

- Asosisasi Ibu Menyusui Indonesia (AIMI) . (2021). Breaking the code: International code violations on digital platforms and social media in Indonesia during the COVID‐19 pandemic (April 2020‐ April 2021). Asosisasi Ibu Menyusui Indonesia AIMI.

- Baby Milk Action UK . (2017). Look what they're doing in the UK. How marketing of feeding products for infants and young children in the UK breaks the rules. http://www.babymilkaction.org/monitoringuk17

- Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan . (2019). Laporan Nasional Riskesdas 2018. Lembaga Penerbit Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan (LPB) Kementerian Kesehatan RI.

- Baker, P. , Smith, J. , Salmon, L. , Friel, S. , Kent, G. , Iellamo, A. , & Renfrew, M. J. (2016). Global trends and patterns of commercial milk‐based formula sales: Is an unprecedented infant and young child feeding transition underway? Public Health Nutrition, 19(14), 2540–2550. 10.1017/S1368980016001117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G. E. , Zambrano, P. , Ching, C. , Cashin, J. , Burns, A. , Policarpo, E. , Datu‐Sanguyo, J. , & Mathisen, R. (2022). Global evidence of persistent violations of the international code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes: A systematic scoping review. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 18(S3), e13335. 10.1111/mcn.13335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry, N. J. , Jones, S. , & Iverson, D. (2010). It's all formula to me: Women's understandings of toddler milk ads. Breastfeeding Review, 18(1), 21–30. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.011907450248010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry, N. J. , Jones, S. C. , & Iverson, D. (2012a). Toddler milk advertising in Australia: Infant formula advertising in disguise? Australasian Marketing Journal, 20(1), 24–27. 10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.10.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry, N. J. , Jones, S. J. , & Iverson, D. (2012b). Circumventing the WHO code? An observational study. BMJ, 97(4), 320–325. 10.1136/adc.2010.202051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, N. (2020). Breastfeeding in India is disrupted as mothers and babies are separated in the pandemic. BMJ, 370, m3316. 10.1136/bmj.m3316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady, J. P. (2012). Marketing breast milk substitutes: Problems and perils throughout the world. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 47(2), 529–532. 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, A. , Pani, P. , Carletti, C. , Guidetti, M. , Mutti, V. , Guidetti, C. , & Knowles, A. (2014). Advertisements of follow‐on formula and their perception by pregnant women and mothers in Italy. BMJ, 100(4), 323–328. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching, C. , Zambrano, P. , Nguyen, T. T. , Tharaney, M. , Zafimanjaka, M. G. , & Mathisen, R. (2021). Old tricks, new opportunities: How companies violate the international code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes and undermine maternal and child health during the COVID‐19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2381. 10.3390/ijerph18052381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Veirman, M. , Cauberghe, V. , & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828. 10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, A. , Marino, J. , Amanat, F. , Krammer, F. , Hahn‐Holbrook, J. , Zolla‐Pazner, S. , & Powell, R. L. (2020). Evidence of a significant secretory‐IgA‐dominant SARS‐CoV‐2 immune response in human milk following recovery from COVID‐19. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.05.04.20089995 [DOI]

- Gage, H. , Williams, P. , Hoewel, J. V. R.‐V. , Laitinen, K. , Jakobik, J. , Martin‐Bautista, E. , Schmid, M. , Egan, B. , Morgan, J. , Decsi, T. , Campoy, C. , Koletzko, B. , & Raats, M. (2012). Influences on infant feeding decisions of first‐time mothers in five European countries. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66, 914–919. 10.1038/ejcn.2012.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grummer‐Strawn, L. M. , Holliday, F. , Jungo, K. T. , & Rollins, N. (2019). Sponsorship of national and regional professional paediatrics associations by companies that make breast‐milk substitutes: Evidence from a review of official websites. BMJ Open, 9(8), e029035. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, G. , Angus, K. , Eadie, D. , & hunt, K. (2020). Selling second best: How infant formula marketing works. Globalization and Health, 16(77), 1–12. 10.1186/s12992-020-00597-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidayana, I. (2015). Stop manipulation at expense of infant nutrition. The Jakarta Post. The Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/11/28/stop-manipulation-expense-in

- Hidayana, I. , Februhartanty, J. , & Parady, V. A. (2017). Violations of the international code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes: Indonesia context. Public Health Nutrition, 20(1), 165–173. 10.1017/S1368980016001567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.‐F. , & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBFAN‐ICDC . (2018). Code Essentials 1–4 (2nd ed). IBFAN‐ICDC. [Google Scholar]

- International Code Documentation Centre [ICDC] . (2008). Annotated international code of marketing of breastmilk substitutes and subsequent WHA resolutions. ICDC. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. A. , & Duckett, L. J. (2020). Advocacy, strategy, and tactics used to confront corporate power: The Nestlé boycott and international code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes. Journal of Human Lactation, 36(4), 568–578. 10.1177/0890334420955158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. , Bhaumik, S. , Morelli, G. , Zhao, J. , Hendry, M. , Grummer‐Strawn, L. , & Chad, N. (2022). Digital marketing of breast‐milk substitutes: A systematic scoping review. Current Nutrition Reports, 11(3), 1–15. 10.1007/s13668-022-00414-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad, P. , Contreras, D. , Ng, H. , Tobin, N. , Chambers, C. D. , Bertrand, K. , Bode, L. , & Aldrovandi, G. M. (2021). No infectious SARS‐CoV‐2 in breast milk from a cohort of 110 lactating women. Pediatric Research, 92, 1140–1145. 10.1038/s41390-021-01902-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health (MoH) . (2022). Nutritional status survey results in Indonesia. The Indonesian Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, S. , Mueller, B. , & Taylor, C. R. (2010). Measuring soft‐sell versus hard‐sell advertising appeals. Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 5–20. 10.2753/JOA0091-3367390201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelanggaran Kode . (2020). https://pelanggarankode.org/

- Perl, S. H. , Uzan‐Yulzari, A. , & Klainer, H. (2021). SARS‐CoV‐2–specific antibodies in breast milk after COVID‐19 vaccination of breastfeeding women. JAMA Network, 325(19), 2013–2014. 10.1001/jama.2021.5782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwoz, E. G. , & Huffman, S. L. (2015). The impact of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes on WHO‐recommended breastfeeding practice. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 36(4), 373–386. 10.1177/0379572115602174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puno, G. R. , Puno, R. C. C. , & Maghuyop, I. V. (2021). COVID‐19 case fatality rates across Southeast Asian countries (SEA): A preliminary estimate using a simple linear regression model. Journal of Health Research, 35(3), 286–294. 10.1108/JHR-06-2020-0229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, D. S. R. , Pérez, M. M. L. , Pérez, M. C. , Hernández, M. I. S. , Pulido, S. M. , Villacampa, L. P. , Vilar, A. M. F. , Falero, M. R. , Carretero, P. G. , Millán, B. R. , Roper, S. , & Bello, M. Á. G. (2021). SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies in breast milk after vaccination. Pediatrics, 148(5), e2021052286. 10.1542/peds.2021-052286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research and Markets . (2019). Indonesia baby food market ‐ Forecasts from 2019 to 2024 [2019 Report]. Research and Market. https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/4835457/indonesia-baby-food-market-forecasts-from-2019

- Rollins, N. C. , Bhandari, N. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Horton, S. , Lutter, C. K. , Martines, J. C. , & Group, T. L. B. S. (2016). Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? The Lancet, 387(10017), 491–550. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkal, E. , & Yildiz, S. (2019). Violation of the international code of marketing of breastfeeding substitutes (WHO Code) by the formula companies via social media. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 104, A143. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-rcpch.338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shubber, S. (1998). The International code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes: An international measure to protect and promote breast‐feeding. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Siregar, A. Y. M. , Pitriyan, P. , & Walters, D. (2018). The annual cost of not breastfeeding in Indonesia: The economic burden of treating diarrhea and respiratory disease among children (<24mo) due to not breastfeeding according to recommendation. International Breastfeeding Journal, 13(10), 1–10. 10.1186/s13006-018-0152-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statista . (2020). Retail sales value of baby food in Indonesia from 2014 to 2019. Statista.com. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1227645/indonesia-baby-food-sales-value/

- Taylor, A. (1988). Violations of the international code of marketing of breast milk substitutes: Prevalence in four countries. BMJ, 316(7138), 1117–1122. 10.1136/bmj.316.7138.1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulleken, C. v , Wright, C. , Brown, A. , McCoy, D. , & Costelo, A. (2020). Marketing of breastmilk substitutes during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The Lancet, 396, e58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32119-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verd, S. , Ramakers, J. , Vinuela, I. , Martin‐Delgado, M.‐I. , Prohens, A. , & Díez, R. (2021). Does breastfeeding protect children from COVID‐19? An observational study from pediatric services in Majorca, Spain. International Breastfeeding Journal, 16(83), 1–6. 10.1186/s13006-021-00430-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. J. , França, G. V. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , & Group, T. L. B. S. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinje, K. H. , Phan, L. T. H. , Nguyen, T. T. , Henjum, S. , Ribe, L. O. , & Mathisen, R. (2017). Media audit reveals inappropriate promotion of products under the scope of the international code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes in South‐East Asia. Public Health Nutrition, 20(8), 1333–1342. 10.1017/S1368980016003591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters, D. , Horton, S. , Siregar, A. Y. M. , Pitriyan, P. , Hajeebhoy, N. , Mathisen, R. , & Rudert, C. (2016). The cost of not breastfeeding in Southeast Asia. Health Policy and Planning, 31(8), 1107–1116. 10.1093/heapol/czw044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (1981). International code of marketing of breast‐milk substitutes. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/code_english.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (1994). World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution 47.5. Infant and Young Child Nutrition. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_R23-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2003). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding: The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. WHO. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/78801 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2005). World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution 58.32. Infant and Young Child Nutrition. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/20398 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2010). World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution 62.23. Infant and Young Child Nutrition. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_R23-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2016a). World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution 69.7. Maternal, infant and young child nutrition: Guidance on ending the inappropriate promotion of foods for infants and young children. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_7Add1-en.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2016b). World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution 69.9 ending inappropriate promotion of foods for infants and young children. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252789 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020). Marketing of breast‐milk substitutes: National implementation of the international code, status report 2020. WHO. http://apps.who.int/iris/

- World Health Organization . (2021). WHO Coronavirus (COVID‐19) dashboard. WHO. https://covid19whoint/region/searo/country/id

- World Health Organization . (2022a). Scope and impact of digital marketing strategies for promoting breastmilk substitutes. WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240046085

- World Health Organization . (2022b). Marketing of breast‐milk substitutes: National implementation of the international code, status report 2022. WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240048799

- World Health Organization & UNICEF . (2020). Breastfeeding and COVID‐19 [scientific brief]. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/breastfeeding-and-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization & UNICEF . (2022). How the marketing of formula milk influences our decisions on infant feeding. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/teams/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-health-and-ageing/formula-milk-industry [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in an Indonesian‐based community reporting platform, Pelanggaran Kode, at https://pelanggarankode.org/en/statistik. Images of online content and the data that support the findings of this study are openly available and accessible to the public at https://pelanggarankode.org/en/statistik.