Abstract

Background:

India has launched Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM), to provide an integrated digital health infrastructure. The success of digital health systems lies in their ability to achieve universal healthcare and incorporate all levels of disease prevention. The objective of this study was to develop an expert consensus on how Community Medicine (Preventive and Social Medicine) can be integrated into ABDM.

Methods:

A total of 17 and 15 participants, who were Community Medicine professionals with more than 10 years experience in the Public Health Sector and/or Medical Education in various parts of India, participated in round 1 and 2 of this Delphi study respectively. The study explored three domains: 1. Advantages and challenges of ABDM, and possible solutions; 2. Intersectoral convergence in Unified Health Interface (UHI) and 3. Way ahead in medical education and research.

Results:

Participants envisaged improved accessibility, affordability, and quality of care due to ABDM. However, awareness generation, reaching out to marginalized populations, human resource constraints, financial sustainability, and data security issues were anticipated challenges. The study identified plausible solutions addressing six broad challenges of ABDM and classified them based on the priority of implementation. Participants listed out nine key roles of Community Medicine professionals in digital health. The Study identified about 95 stakeholders who play direct and indirect roles in public health and can be connected to the general public through the Unified Health Interface of ABDM. Further, the study explored the future of medical education and research in the digital era.

Conclusion:

The Study contributes to broadening the scope of India’s digital health mission, with elements of Community Medicine in its cornerstone.

Keywords: Delphi technique, digital health, eHealth, medical education, national digital health mission, preventive and social medicine

INTRODUCTION

The health care delivery system in India is evolving, to keep up with the pace of the era of digitalization.[1] Telemedicine platforms are now established in both private and public health sectors. The COVID-19 pandemic further underlined the purpose of digital health, to ensure availability, accessibility, and affordability in times of war, disaster, and peace.[2] Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) aims to “develop the backbone necessary to support the integrated digital health infrastructure of the country” and to “bridge the existing gap amongst different stakeholders of Healthcare ecosystem through digital highways.”[3] The Government of India has also assigned 500 crores to its States and Union Territories for supporting manpower to implement ABDM in the next five years.[4]

ABDM ecosystem includes citizen Ayushman Bharat Health Account (ABHA) and Personal Health Record (PHR), Healthcare Professionals Registry (HPR), Health Facility Registry (HFR), and Unified Health Interface (UHI). While the HPR and HFR create a list of available professionals, labs, hospitals, and other healthcare facilities, UHI is a digital platform where the patients using different End-User applications can connect with the Health Service Provider applications.[5] PHR is patient-controlled, can be accessed digitally by providers with the patient’s consent. Thus, ABDM is envisaged as an attractive patient-centric add-on to the traditional healthcare delivery systems.

While the emphasis is largely on diagnostic and curative aspects of health in ABDM, we believe that there is immense opportunity in this digital platform for quality-assured preventive and promotive healthcare as well. With aim of broadening the scope of ABDM to involve Community Medicine (Preventive and Social Medicine), we designed this study with the objective of developing an expert consensus on how Community Medicine can be integrated into ABDM.

METHODS

This study was designed using the Delphi technique, which is an “iterative process designed to combine opinion into group consensus”.[6] Participants of the study were professionals who are working in the fields of Public Health and Medical Education (Community Medicine) for 10 years or more, selected by purposive sampling by the authors by the way of previous acquaintance. A total of 22 professionals were initially contacted[7] telephonically to brief them about the study and obtain their verbal consent to participate, among whom, 17 completed the first round and 15 completed both rounds of the study.

In Round-1 (February 2022) of the study, participants were sent a Google form, explaining the purpose of the study, confidentiality, data management, and procedure. They were requested to proceed to the questionnaire after reading through the instructions to fill out. Continuation of the Delphi participant-to-study questionnaire was assumed as consent to participate. Reminders were sent twice during each round and the participants were requested to answer the questionnaire within 30 days. The questionnaire was divided into three domains: 1. Advantages and challenges of ABDM, and possible solutions; 2. Intersectoral convergence in UHI and 3. Way ahead in medical education and research; with questions to rate on the Likert scale as well as open-ended questions in each domain. Content validation of the questionnaire was done by two subject experts. The responses were collated, summarized, and sent back to the participants in Round-2 (March 2022) as a second Google form. Round-2 consisted of a questionnaire where the questions of Round 1 were repeated, indicating the highest chosen rating on the Likert scale. Additionally, newer themes that had been identified through open-ended questions of Round 1 were presented to participants for rating. Round-2 allowed participants to change, add or retain their previous responses and also present their arguments for their opinion. Responses of Round 2 were considered as their final opinions and used for content analysis. While 100% consensus (all 15 participants arrived at the same rating to a question) was considered as ‘complete consensus’, consensus above 75% (at least 11 participants or more arrived at the same rating to a question) was considered ‘partial consensus’. When responses to a question did not reach a consensus (less than 75% agreement), it was presented as a ‘suggestion of the majority, with no consensus’. Individual suggestions have also been presented.

All participants remained anonymous to the identity of other participants. Responses received were strictly confidential and accessed only by the study team. A copy of the responses in both Rounds 1 and 2 was sent back to the respective participant upon successful submission of the forms. Institutional human research ethics committee approval was obtained (No. GMCS/STU/ETHICS-3/Approval/21833/22). No patient data were collected for this study, and the study was completely based on the feedback provided by experts in the field regarding ABDM.

RESULTS

Envisaged impact of ABDM on the healthcare system, challenges, and solutions

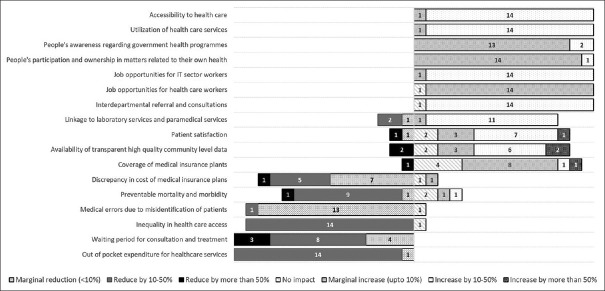

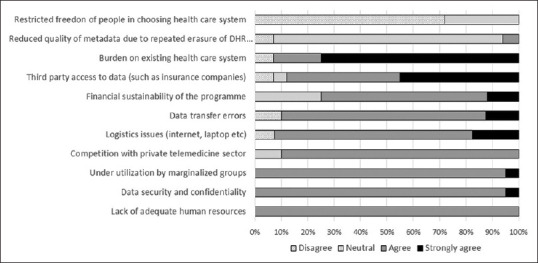

Participants estimated the extent to which ABDM would impact different aspects of the existing healthcare system [Figure 1] and the challenges expected [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Impact of ABDM on existing healthcare system

Figure 2.

Challenges anticipated in the implementation of ABDM

a. Accessibility to healthcare: While most participants agreed that ABDM would increase accessibility and utilization of healthcare services by 10-50%, they estimated that people’s awareness regarding healthcare programs would increase only marginally. ABDM would also, to a marginal extent, stimulate people’s participation and ownership in health. Even when most participants opined that inequality in healthcare access would reduce by 10-50%, participants agreed that under-utilization by marginalized groups would be a major challenge. The waiting period for consultation and treatment was agreed to decline, while 27% of participants felt that there would be a decrease or no impact on patient satisfaction. One participant opined that the “human touch must not be forgotten” in the transition to digital health.

b. Quality of care: Partial consensus was reached on the opinion that medical errors due to misidentification of patients would decline and linkage to the lab and paramedical services would improve. One participant opined, “One of (the) benefits of NDHM (ABDM) could be that patient can access their data anywhere using UHID (ABHA), provided they are educated on it.” Meanwhile, data transfer errors and logistics shortages (like laptops and internet facilities) were agreed by the majority as challenges of ABDM, that would compromise the quality of care.

c. Human resources: Job opportunities for IT sector professionals were estimated to rise by 10-50%, while that for health care workers was estimated to increase only marginally. Lack of adequate human resources was unanimously agreed to as a challenge, and about 73% of participants strongly agreed that ABDM could burden the existing healthcare system, in terms of “workload”.

d. Out-of-pocket expenditure (OOP) and private sector engagement: It was estimated by the participants that OOP on health would decrease by 10-50%. Participants attributed this to the expected increase in healthcare providers for patients to choose from, transparency in the system, improved insurance coverage, and savings on travel expenses. While the majority of participants agreed that ABDM will have to compete with the private telemedicine sector, individual participants also opined that it would lead to integration rather than competition.

e. Health insurance packages and coverage: While no consensus was reached on the impact of ABDM on health insurance coverage, 66% of participants opined that there would be a marginal to more than 50% increase in coverage. It is expected that ABDM would act as the “single source of truth” for health data. The participants opined that if this is achieved, then discrepancies and differences in health insurance packages in the private sector can be resolved. Data security and confidentiality issues was considered a challenge, and unauthorized data access by a third party (such as insurance companies) was considered a threat.

f. Quality of public health data: The majority of participants also agreed that ABDM could be a good source of transparent, high-quality community level data which would be useful for “Policy planners, Researchers and Insurance companies”, provided the IT platform of ABDM is designed for this purpose, with systems for data retrieval and analysis, while maintaining the confidentiality and defining the margin of error. ABDM allows the patients to create and delete digital health records (ABHA) at their convenience and about 87% of the participants remained neutral as to whether the quality of meta-data would reduce due to this, and commented that this would be a topic to be “explored when ABDM is rolled-out”.

Participants were asked to suggest plausible solutions for the challenges that were identified and classify them based on the priority of implementation, as “Critical level” (actions/steps that should be ensured before the launch of ABDM), “Important level” (actions/steps that should be undertaken during implementation and maintained thereafter), “Normal level” (that can be undertaken when the system is established) and “Not required”. Here we have presented interventions as classified by the majority of participants (given as a percentage of participants in brackets in Table 1).

Table 1.

Plausible solutions for the challenges and priority of implementation {original}

| Critical level priority | Important level priority | |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility to healthcare | Strong political will and commitment (67%) Integrating Community Medicine professionals (academic and non-academic) to ABDM (67%) Setting up ABDM kiosks at village level and Health and Wellness Centres (47%) | Identify and concentrate on marginalized population (60%) Phase wise implementation of the programme (53%) Patient education and awareness generation/intensified IEC aiming at demand generation (53%) |

| Quality of care | Setting up a dedicated team of Health and IT professionals for ABDM (93%) Logistics supply and maintenance (80%) | Resolve technical issues of all the existing Government apps and keeping websites updated and responsive (53%) |

| Human resources | Capacity building of existing human resources (93%) Filling up existing vacancies in health care system (67%) | Improving digital/computer literacy among medical and paramedical students and staff (67%) |

| Out of pocket expenditure and private sector engagement | Identify stakeholders and include them in Unified Health Interface (47%) Set criteria for quality of services provided by partnering stakeholders (47%) | Private sector involvement (40%) |

| Health insurance packages and coverage | Establish and disseminate guidelines for telemedicine, digital health data generation, maintenance and use (60%) | Government regulations in mandating the use of public health data to devise affordable health insurance packages and social support schemes (individual suggestion) |

| Quality of public health data | Build IT platform that ensures data confidentiality and defines access levels (53%) | Identify internal and external quality indicators and agencies to monitor the same (47%) |

Role of Community Medicine professionals in digital health

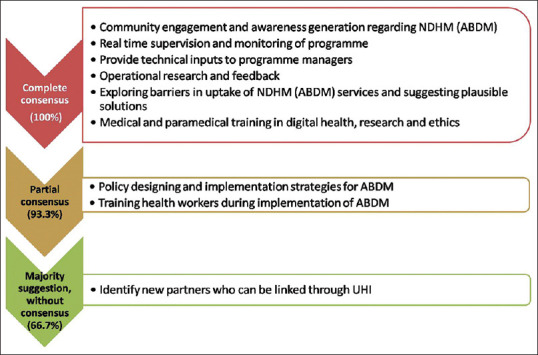

Participants identified contributions Community Medicine professionals can make in ABDM and the responses have been classified based on the consensus reached [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Role of Community Medicine professionals in ABDM

Expanding the scope of Unified Health Interface

UHI is an interface of End Users (citizens) and healthcare providers who offer diagnostic and therapeutic services. Participants named about 44 MOHFW and healthcare agencies and 51 other agencies/services which can be linked through the UHI to citizens [Table 2].

Table 2.

Existing agencies/services to be linked to the end user through UHI {original}

| Domain | MOHFW and Public/Private Healthcare agencies/services | Other ministries and Public/Private agencies/services |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrition | RBSK, Registered dieticians, Yoga practitioners, Gyms, Nutritional Rehabilitation Centre PHC health team* | Anganwadi, ICDS officials (CDPO), Local Govt. approved farmers/food producers (individual/NGO)® District Agricultural Officer, Sub divisional Agricultural Officer, Govt apps for agricultural produces ® Ministry of Fisheries, Animal husbandry and dairying, Veterinary doctor® Ministry of Food Processing Industries® PDS registration and grievance system |

| Water related (water borne, water washed, water based) diseases | Health Inspector/Sanitary Inspector/MPHW, Health Assistant PHC health team* | PWD, Autonomous facilitating organizations, such as Water Supply & Management Organisation (WASMO), Panchayat (PRI) and municipality/village grievance system/website, CPCB, ® Public health laboratories, Meteorological centre® |

| Vector borne diseases | Health Inspector/Sanitary Inspector/MPHW, Health Assistant PHC health team* | Panchayat (PRI) and municipality/village grievance system/website, Entomologist (District/Government Medical College/Research Institute), Ministry of Fisheries, Animal husbandry and dairying ® District Agricultural Officer, Sub divisional Agricultural Officer, Local Govt.approved NGOs, dealers of insecticides® Meteorological centre® |

| Maternal and child health, Reproductive and sexual health, family planning | ASHA, Laboratory services, Blood banks, Ambulance services, Milk banks PHC health team* | Anganwadi, Ministry of Women and Child Development |

| Adolescent health | PHC health team* RBSK ARSH clinic | ICDS, ® DEO, ® Youth affairs and Sports Local Govt.approved NGOs |

| Primodial and primary prevention of Non communicable diseases | National/state Tobacco cell® NCD cell, RBSK, Certified NGOs/persons facilitating Yoga and Meditation, Medicosocial workers, ASHA, Health Inspector/Sanitary Inspector/MPHW, Health Assistant PHC health team* | Ministry of Women and Child Development Inspector cum Facilitator (Occupational health and Health Safety Code) ® |

| Tertiary prevention of Non Communicable diseases | Tertiary hospitals (Govt/Private) for Rehabilitation, Certified NGOs/persons facilitating rehabilitation NCD cell | UDID portal, Department of Social justice and empowerment, ® Inspector cum Facilitator (Occupational health and Health Safety Code) ® |

| Waste management | Health Inspector/Sanitary Inspector/MPHW, Health Assistant PHC health team* | Panchayat Raj Institutions (PRI) and municipality/village PWD, CPCB, Public Health laboratories, Certified NGOs/persons/agencies® |

| Climate change and health | Research Institutes, Universities® PHC health team* | Certified NGOs/persons/agencies, ® CPCB, Public Health laboratories, ® Meteorological centre, Ministry of Environment and Forests, |

| Food borne diseases | Health Inspector/Sanitary Inspector/MPHW®, Health Assistant PHC health team* | Food Safety and Drug Control, Food Safety Officers, Food Inspectors, Hotel and Restaurant associations Ministry of Food Processing Industries, Ministry of Agriculture Ministry of Fisheries, Animal husbandry and dairying, Quality control cells (Dept of Food and Public distribution) ® |

| Airborne/droplet infections and communicable diseases not included in any other section | Health Inspector/Sanitary Inspector/MPHW, Health Assistant PHC health team* Epidemiology division of Research Institutes, Universities | CPCB, ® Certified NGOs/persons/agencies, ® |

| Occupational health | ESI hospitals Blood banks®, Ambulance services, Tertiary hospital for Disability certification & Rehabilitation, ® PHC health team* | Ministry of Labour and Employment, Inspector cum Facilitator (Occupational health and Health Safety Code), Certified NGOs/persons facilitating rehabilitation, ® UDID portal® |

| Road traffic accidents and accidents in other means of transport | Blood banks, ® Ambulance services, PHC health team* Tertiary hospital for Disability certification and rehabilitation, Certified NGOs/persons facilitating rehabilitation, ® | Traffic police, Railway police (Police department), Ministry of Road and Transport, Railways, UDID portal, ® National Handicapped Finance Development Corporation® |

| Mental health (including substance abuse) | Psychology counsellors, Certified NGOs/persons/agencies/apps, District/Taluk Mental Health Programme, ® Rehabilitation/Deaddiction centres District Tobacco Control cell PHC health team* | UDID portal, ® National Handicapped Finance Development Corporation, ® Narcotic Control bureau, Special schools® |

| Women and child abuse, juvenile delinquency | Psychology counsellors, PHC health team* District/Taluk Mental Health Programme | Police department, Protection Officer, National commission for women, Certified NGOs/persons/agencies, ® Rehabilitation homes, orphanages, rescue centres, Department of Social justice and empowerment® |

| Genetic disorders | RBSK team, ® Blood bank, ® Stem cell therapy facilities, Genetic labs, ® NIDAN Kendras, Antenatal screening and diagnostic facilities, PHC health team* | Certified NGOs/persons/agencies |

| Geriatric health | Blood bank, ® Ambulance services, Old Age homes, Rehabilitation centres, Hospices, palliative care homes PHC health team* | Certified NGOs/persons/agencies |

| Disasters and outbreaks | Blood bank, Ambulance services PHC health team* | Fire and safety, Police Disaster management cell, State Disaster Management Authority ® Mass media and communication cell® Water authority, PDS Panchayat Raj Institutions (PRI) and municipality/village system/website, ® Meteorological centre® Certified NGOs/persons/agencies® |

| Gateways to portals related to Health Insurance, Social support and related schemes | PMJAY Ayushman Bharat card Authorized Health Insurance companies® Disease specific support schemes® | Indian Post Office, Nationalized banks, Pension (Old age, Widow pension etc) schemes, State specific social support schemes Insurance Regulatory and Development Authorityᶺ |

| Others | Certified outlet for non-pharmaceutical products (eg. Sanitary napkins, condoms, bed nets, Indoor residual spray etc) produced by the Govt/Govt approved agencies, Jan Aushadhi outlet (Pharmacy) | |

| IHIP (IDSP) link with option for self reporting of cases/disease outbreaks by general public® Community Medicine Department of medical colleges ® Implementation agencies for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)^ Tribal District Subplan^ | ||

*PHC Health team-including PHC Medical Officer, Nursing staff, other PHC staff. The table shows options that were chosen by all the participants (100% consensus), except for those marked with ®, which represents Partial consensus (87-93%) and ^, which represents individual suggestion

Envisaged changes in medical and paramedical training

As the presence of digital health becomes more marked, medical and paramedical training must evolve to incorporate, utilize and deliver digital health facilities. All participants opined that there should be infrastructure installation and upgradation, including high-speed internet connection, computers, etc., in all medical and paramedical colleges for practical demonstration of digital platforms. There was partial consensus (87%) on making hands-on training in implementation, functioning, and use of ABDM interface at the undergraduate level compulsory. Only 73% felt that compulsory projects in digital health should be included in exam eligibility criteria for undergraduate students. Instead, 87% of participants suggested using skill labs for training students and developing other methods of assessment of digital health skills and certification. The use of patient-related data and a sample database for training students was supported by 80% of the participants.

One participant emphasized that “Digital health is not just using of computers and technology to interact with patients. It is also the use of correct communication strategies and guiding the patient. It requires training.” This was reflected by other participants (87%) who felt that culture inclusivity and cultural appropriateness must be promoted. Participants (93%) also agreed that students must be sensitized on the importance of digital health, with emphasis on the objectives of ABDM, including the importance of preventive and promotive aspects in digital health delivery (87%).

Regular training of trainers (teachers) in digital health was suggested by 87% of participants. About 87% stressed guiding students in medicolegal aspects of digital health. In order to avoid data discrepancies, the development of a universal content coding system for patient diagnosis, management, and training, was suggested by 93% of participants.

Future of medical research in the era of digital health

Participants commented on the Methods, Ethics, and Reliability of research in digital health.

All participants agreed that real-time data availability through ABDM would invariably stimulate actions and research studies based on digital self-monitoring tools, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. About 87% of participants also opined that this new research avenue would require training and capacity building in Big data analysis and its uses.

Upholding ethics in research was highlighted by all participants, who emphasized patient autonomy in data sharing for research, with an inbuilt mechanism in the ABDM platform. About 87% of participants suggested that detailed guidelines should be prepared regarding access to digital health records of patients for research purposes with accountability and legal provisions for any breach. It was suggested (80%) that there should be different levels of metadata so that anonymized, aggregated data can be accessed for research, whereas individual patient-level data would require permission from the patient to access. Participants (93%) also suggested that Institutional Ethical committees should be trained in the ethics of using digital data.

All participants anticipated errors in data of ABDM due to inaccuracy in entry and reporting. It was suggested by 93% that interface itself should be designed to ease relevant data collection, regular entry, and updation. The use of unique identifiers, such as cards and electronic devices for data entry was suggested to improve data reliability. Participants (93%) suggested that measures for monitoring the quality of data, regular analysis, and feedback to health officials and policymakers at different levels should be planned.

DISCUSSION

The 73rd World Health Assembly in 2020 endorsed Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020-25. WHO urged Member States to develop country-specific, eHealth mechanisms.[8] Further, it was emphasized that digital health services would be valued if it stands for accessibility, equitability, affordability, and sustainability in healthcare and is inclusive of all levels of disease prevention, including health promotion and specific protection.

In India, National Health Policy 2017, which conceptualized National Digital Health Authority (NDHA) for digital healthcare delivery, also highlighted the role of “preventive and promotive health care orientation in all developmental policies” in “achieving highest possible level of health and well-being”.[9] The vision of Digital health, thus, should not be restricted to diagnostic and curative health but include promotive and preventive health, research and development, innovation, and intersectoral collaboration.[8]

The results of this study converge at three important points. Firstly, the current ABDM platform can be upgraded, so that it can be utilized by various agencies for research, medical education, and policy-making. This calls for additional protocols for big data generation, analysis and utilization, quality monitoring, and resource strengthening. This study also advocates for generating various levels of datasets, with appropriate deanonymization, which could be used ethically for research and quality control purposes.[8] Further, the study identifies challenges such as underutilization by vulnerable people[10] and how human resources are exceedingly important in generating public awareness regarding ABDM, developing public ownership in health, and sustaining the ABDM ecosystem.[11]

Secondly, the Community Medicine fraternity can contribute to digital health research, education, and health policy. This would require the integration of Community Medicine professionals at various levels of ABDM development and implementation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind, where the perspectives of Community Medicine professionals on ABDM have been recorded.

Thirdly, in order to aim at holistic healthcare delivery and address social determinants of health, intersectoral convergence can be achieved by diversifying stakeholders and partners in UHI. Intersectoral cooperation is a guiding principle of primary healthcare. The people’s access to different stakeholders in public and private sectors through UHI ensures that they get access to not only diagnosis and treatment but also support in prevention and health promotion. In short, it can be envisaged that a citizen with ABHA entering the ABDM ecosystem, will be directed by an interactive platform to diagnostic and curative health services and to location-specific, culturally appropriate, health-promotive, and disease prevention services as well.

This study included a small group of purposively selected Community Medicine professionals to participate using the Delphi technique. Hence the study results may not be representative of other professionals in the field. Similarly, the ideas presented here are not exhaustive and can be developed further. However, this study calls for revisiting the scope of ABDM to include the expertise of Community Medicine.

CONCLUSION

ABDM can become a powerful tool in healthcare delivery. However, its design must include various aspects and agencies of preventive and social medicine also, with Community Medicine professionals in strategic positions in policy-making, implementation, medical education, and research.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to all the Community Medicine subject experts who consented and participated in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Board of Governors: In supersession of the Medical Council of India, NITI AYOG. Telemedicine Practice Guidelines. MOHFW. 2020 Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Telemedicine.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: A systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1193. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health Authority, Government of India. Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission. 2022. [Last accessed on 2022 Apr 13]. Available from: https://abdm.gov.in/

- 4. [Last accessed on 2022 Apr 13];National Health Authority, Government of India. Guidelines for Setting up of State Office for Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission. 2022 4 Available from: https://abdm.gov.in:8081/uploads/State_Guidelines_ABDM_Final_f766c3b11c.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Authority. Consultation Paper on Unified Health Interface. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2021. [Last accessed on 2022 Apr 18]. Available from: https://abdm.gov.in/assets/uploads/consultation_papersDocs/UHI_Consultation_Paper.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKenna HP. The Delphi technique: A worthwhile research approach for nursing? J Adv Nurs. 1994;19:1221–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clayton MJ. Delphi : A technique to harness expert opinion for critical decision-making tasks in education. Educ. Psychol. 1997;17:373–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020-2025. Geneva: 2021. doi:Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare India. National Health Policy 2017. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith B, Magnani JW. New technologies, new disparities: The intersection of electronic health and digital health literacy. Int J Cardiol. 2019;292:280–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.05.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Declerck G, Aimé X. Reasons (not) to Spend a Few Billions More on EHRs: How Human Factors Research Can Help. Yearb Med Inform. 2014;9:90–6. doi: 10.15265/IY-2014-0033. doi: 10.15265/IY-2014-0033. PMID: 25123727; PMCID: PMC4287089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]