ABSTRACT

Background:

Understanding the significance of adolescents’ mental health, school-based mental health interventions are being implemented with the help of teachers globally.

Aim:

Owing to the dearth of literature concerning the beliefs, and stigma among the teachers, the present study was conducted with an aim to study the mental health beliefs among teachers.

Methods:

This is a cross-sectional study conducted among randomly selected teachers teaching in government and private schools of Sikar city of Rajasthan. A general sociodemographic questionnaire, Beliefs Towards Mental Illness Scale, and a questionnaire about prior exposure to mental health issues was administered. Stata 15.0 was used for statistical analysis, and independent t-test and one-way analysis of variance test were applied to find out associations.

Results:

Majority of the participants were in age group of 31-40 years, married, and postgraduate. The mean Beliefs Towards Mental Illness Scale score of 147 teachers was 49.95 ± 17.34 of 105. Only 2% of the study participants have ever received training related to mental health issues. Teachers who had prior exposure to mental health issues, residing in semi-urban and urban areas showed more positive beliefs.

Conclusion:

Study participants have displayed negative beliefs toward mental health. This brings to light the important interventions like creating knowledge and awareness among the study population by conducting trainings. More research is needed to explore the mental health beliefs among the teachers.

Keywords: Adolescents, mental health beliefs, mental illness, teachers

INTRODUCTION

Mental health issues account for 16% of the global burden of disease and injury among people aged 10-19 years, and suicide is the third leading cause of death among them.[1] Almost half of the cases of mental illnesses usually begin before the age of 14 years.[2] In India, where one of seven Indians suffers from a mental illness, mental illness disproportionately affects children and adolescents.[3] In 2014, a systematic review and meta-analysis of child and adolescent psychiatric illnesses revealed a prevalence rate of 6.46% in the community and 23.33% in Indian schools.[4] More than half of people with mental illnesses in the world do not receive any treatment and this proportion rises to nearly 90% in low and middle income countries.[5]

Stigma and discrimination are most prominent barrier to seeking help and recovery for people suffering from mental illnesses.[6] One of the underlying causes of stigma is its relationship to mental illness beliefs. People hold various negative beliefs about mental illnesses, such as the etiology of mental illness being caused by misfortunes, spiritual imbalance, linking mental illness to dangerousness, severity, poor prognosis, failure to fulfill responsibilities, and many more.[7-10] The stigma associated with mental illness is a major public health issue due to its negative impact on treatment seeking, adherence, and effectiveness.

During the period of transition from child to adult, there are rapid physiological and psychological changes taking place. The struggles they face are many, including peer acceptance, identity struggles, stress related to education and career choices, and parental approval, which makes them more vulnerable to some form of mental illness, such as mood disturbances, eating disorders, substance abuse, depression, suicidal behaviors, and others.[11]

The key to preventing fatal consequences like suicides and decreasing the negative impacts of mental illnesses is early identification and timely intervention.[12,13] Schools, where children and adolescents spend much of their time, are an ideal setting for health promotion and preventive interventions.[14] Teachers have daily interactions with adolescent students and can detect changes in their behavior before they become full-blown symptoms. As a result, teachers can be a valuable resource in providing mental health services to adolescents.[15]

Teacher’s beliefs and awareness about mental illness affects their behavior toward students in the classroom. Better-aware teachers have favourable attitude towards their student’s mental health issues.[16] There are very few studies conducted in Indian context, that too have reported inadequate knowledge about mental illnesses and high levels of stigma among the teachers in India,[17,18] which emphasizes the need to study the mental health beliefs among teachers in India. Because levels of stigma vary significantly across different regions of India due to factors such as literacy rates and others, conducting studies across the country is important.[19] Hence, this study is designed to study the mental health beliefs among the teachers teaching in Sikar city of Rajasthan with the objectives to determine the mental health beliefs among them and to find out any associations between mental health beliefs, sociodemographic profile of the school teachers, school characteristics of the teachers, and their prior exposure to mental health issues. This study is first of its kind in the Sikar city which is a growing hub for education in Rajasthan and students from surrounding states and cities visit there for preparation of competitive examinations and we anticipate high risk of mental health issues among them and in that context exploring beliefs of teachers is of utmost importance.[20,21]

METHODOLOGY

A school-based cross-sectional study was carried out during February 2021 to May 2021 among teachers of both government and private schools of Sikar city of Rajasthan. Sikar city is located in the north-eastern part of the state of Rajasthan, India, and is the administrative headquarters of Sikar district. There are many coaching centers in Sikar city, so many students from neighboring villages and districts take admission in schools, colleges, and coaching institutions to prepare for competitive examinations. The inclusion criteria for the study were all teachers who were formally involved in teaching students and who gave their consent to participate.

A minimum sample size of 90 was required based on 95% confidence intervals, variability of 14.5 considering existing literature, and precision of 3.[22] The final sample size was 180 after adjusting for 50% nonresponse. The study used a multistage sampling technique. Initially, Sikar city was conveniently selected. A list of registered schools in the urban blocks of Sikar was compiled. Schools were contacted based on their proximity to the investigator’s residence and those who agreed to participate were included in the final list. On the final list, there were nine schools, six private schools and three government schools with teacher’s strength ranging from 32 to 58. For the final stage of the study, 20 teachers were randomly selected by lottery from the list of all teachers obtained from each school.

Ethical clearance for the study proposal and tools was taken from the institutional ethics committee. Permissions to collect data were obtained from the Directorate of School Education and schools administration. During data collection, a written informed consent was obtained from each participant before the administration of the questionnaire.

The selected teachers were administered a prestructured questionnaire in English divided into three parts. First part captured sociodemographic profile (age, gender, place of residence, marital status, educational qualification, and household income) and work characteristics (type of institution they are teaching in, teaching experience, classes taught, and subjects taught by them). Second part captured information related to prior exposure to mental health issues (any history of mental illness, treatment or therapy or consultation received for mental illness, any relationship with individual suffering from mental illness, any training received for mental illness, or any counseling provided to the student for mental illness). Prior exposure to mental health issues was operationally defined as ‘those who have replied yes to any of the questions related to exposure are prior exposed to mental health issues and those who have replied No to all of the questions are unexposed to mental health issues’.

Third part was Beliefs toward Mental Illness Scale (BMIS) developed by Hirai and Clum (2000) having Cronbach’s alpha 0.89 among American and 0.91among Asian respondents.[23] For each of the 21 statements in the BMIS, a six-point scale of agreement is used. The scale ranges from ‘0’ to ‘5’, indicating complete disagreement and complete agreement. The total score ranges from 0 to 105. Higher scores indicate negative beliefs. The questions are further categorized into four factors, creating subscales for the various dimensions of the beliefs.

Data were entered and coded on an excel sheet and statistical analysis was done with the help of Stata version 15.0. Sociodemographic profile and prior exposure to mental issues are expressed as percentages and frequencies. Mean score along with standard deviation is presented for beliefs toward mental illness. Independent t-test and one-way analysis of variance test are used to find associations between the mental health belief scores and sociodemographic factors, school characteristics, and prior exposure to mental health issues.

RESULTS

Of the selected nine schools, data collection was done from eight schools (6 private and 2 government) due to constraints caused by COVID-19. One hundred sixty teachers were approached for data collection, of which 147 completed the survey with consent. Nonresponse rate was around 8% (13 of 160).

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The information was available for 147 participants, ages ranging from 20 years to 60 years with mean age of 34.51 ± 8.06 years. Majority were in age group of 31-40 years. Of total participants, there were 57% females, 82% married, and 61% with postgraduation. School characteristics include 74% teachers from private schools, 36% teachers teaching science or physical education, and more than 50% were higher-secondary school teachers.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile and school characteristics of the teachers

| Variables (n=147) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 63 (42.86) |

| Female | 84 (57.14) |

| Age | |

| 20-30 years | 48 (32.65) |

| 31-40 years | 72 (48.98) |

| >40 years | 27 (18.37) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 121 (82.31) |

| Unmarried | 26 (17.69) |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban | 95 (64.63) |

| Semi-urban | 29 (19.73) |

| Rural | 23 (15.65) |

| Educational qualification | |

| Graduate | 57 (38.78) |

| Postgraduate | 90 (61.22) |

| Type of institution | |

| Government | 38 (25.85) |

| Private | 109 (74.15) |

| Teaching experience | |

| 1-5 years | 47 (31.97) |

| 6-10 years | 56 (38.10) |

| >10 years | 44 (29.93) |

| Classes taught | |

| Primary | 41 (27.89) |

| Secondary | 24 (16.33) |

| Higher secondary | 82 (55.78) |

| Subjects taught | |

| Science/Physical education | 53 (36.05) |

| Others | 94 (63.95) |

Of total, 29% teachers have counseled their students for mental health issues in their teaching career and only 2% have ever received training related to mental health issues. Less than 2% reported any history of mental illness and 13% reported having a relationship with an individual having a mental health problem. None of the participants have ever received any treatment due to mental health problems. As per operational definition, prior exposure to mental illness was present in 60 participants (41%), while the rest of 87 participants (59%) did not have any prior exposure regarding mental health issues as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prior exposure related to mental health issues

| Variable (n=147) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| History of mental problem | |

| Yes | 2 (1.36) |

| No | 145 (98.64) |

| Psychiatrist/Psychologist consultation | |

| Yes | 5 (3.40) |

| No | 142 (96.60) |

| Any treatment due to mental health problem | |

| Yes | 0 (0) |

| No | 147 (100) |

| Having a relationship with a person with mental health problem | |

| Yes | 19 (12.93) |

| No | 128 (87.07) |

| Relation with the individual having a mental problem | |

| Family member/relative | 11 (57.89) |

| Neighbour | 3 (15.79) |

| Friend | 3 (15.79) |

| Others | 2 (10.53) |

| Counselled a student with mental health problem | |

| Yes | 43 (29.25) |

| No | 104 (70.75) |

| Received any training related to mental health | |

| Yes | 3 (2.04) |

| No | 144 (97.96) |

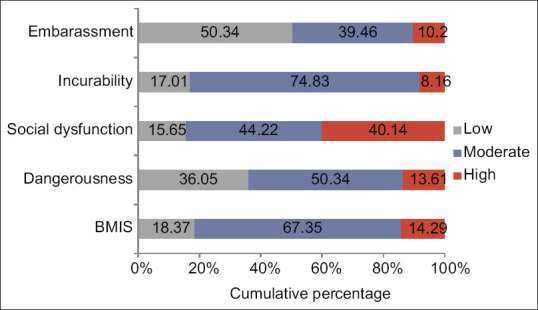

Table 3 shows the total BMIS and subscales scores for the teachers. The mean BMIS scores is 49.95 ± 17.34 (min-max 8-86) and 8.47 ± 4.56 for dangerousness subscale, 20.11 ± 7.65 for social dysfunction subscale, 14.39 ± 4.71 for incurability subscale, and 6.97 ± 4.7 for embarrassment subscale. To further explore the subscale dimensions, all the scales were categorized into tertiles (low, moderate, and high scores). On almost all dimensions of the scale, maximum participants scored moderate except for the embarrassment subscale. On high scores, dimension social dysfunction has maximum participants (40%); however, on low scores, embarrassment dimension have maximum (50%) participants [Figure 1].

Table 3.

Scores on the Beliefs toward Mental Illness Scale and subscales for the total teacher’s sample

| Scores (n=147) | Mean (SD) | Minimum scores- Maximum scores |

|---|---|---|

| Total BMI score (0-105) | 49.95 (17.34) | 8-86 |

| Dangerousness Subscale (0-20) | 8.47 (4.56) | 1-20 |

| Social dysfunction Subscale (0-35) | 20.11 (7.65) | 0-35 |

| Incurability Subscale (0-30) | 14.39 (4.71) | 2-28 |

| Embarrassment subscale (0-20) | 6.97 (4.7) | 0-18 |

Figure 1.

Percentage of teachers plotted against scores on BMIS scale and subscale. Low score, Moderate score, and High score

Detailed comparison of sociodemographic characteristics and body mass index (BMI) scores and subscales scores are presented in Table 4. Total BMI scores of teachers teaching primary classes were significantly lower than those teaching secondary and higher secondary classes (P <.05). When subscales were evaluated, dangerousness, social dysfunction, and embarrassment subscales showed significant differences (P <.05) among the three groups with primary teachers having comparatively less negative beliefs than other two. Those who resided in rural areas showed negative beliefs that are higher BMI scores as compared to those resided in semi-urban and urban areas (P <.05). On the further subscales evaluation, all the parameters except incurability showed statistically significant differences among the rural, semi-urban, and urban people (P <.05). Those who were exposed to mental health issues showed less negative beliefs as compared to those who are not exposed (P <.05).

Table 4.

Association of scores teachers obtained from the beliefs towards mental illness (BMI) scale and its subscales according to their socio-demographic profile, school characteristics, and prior exposure to mental health issues

| Variables | Dangerousness Subscale Mean (sd) P | Social dysfunction Subscale Mean (sd) P | Incurability Subscale Mean (sd) P | Embarrassment subscale Mean (sd) P | Total BMIS score Mean (sd) P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender* | |||||

| Male | 7.87 (4.09) | 21.11 (6.26) | 14.44 (3.94) | 8.13 (3.97) | 51.55 (14.59) |

| Female | 8.92 (4.86) | 19.36 (8.49) | 14.36 (5.24) | 6.11 (5.03) | 48.74 (19.14) |

| 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.91 | < 0.01 | 0.31 | |

| Age (years)** | |||||

| 20-30 | 8.14 (4.45) | 20.04 (8.25) | 14.17 (4.73) | 7.56 (4.96) | 49.92 (18.89) |

| 31-40 | 8.68 (4.47) | 20.40 (7.44) | 14.57 (4.53) | 7.15 (4.73) | 50.80 (17.08) |

| >40 | 8.48 (5.11) | 19.44 (7.30) | 14.33 (5.29) | 5.44 (3.91) | 47.70 (15.45) |

| 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.16 | 0.73 | |

| Marital status* | |||||

| Married | 8.57 (4.56) | 20.45 (7.35) | 14.48 (4.69) | 6.97 (4.72) | 50.47 (17.03) |

| Unmarried | 8.00 (4.60) | 18.5 (8.86) | 14 (4.89) | 7.00 (4.70) | 47.5 (18.86) |

| 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.64 | 0.97 | 0.43 | |

| Place of residence** | |||||

| Rural | 9.30 (4.66) | 22.17 (6.15) | 15.00 (3.93) | 8.91 (5.31) | 55.39 (15.36) |

| Semi-urban | 6.55 (4.64) | 16.69 (7.38) | 13.24 (5.14) | 4.72 (4.59) | 41.21 (17.88) |

| Urban | 8.85 (4.39) | 20.65 (7.79) | 14.60 (4.74) | 7.19 (4.35) | 51.29 (16.84) |

| 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.32 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |

| Qualification* | |||||

| Graduate | 8.53 (4.53) | 20.17 (8.48) | 13.82 (5.08) | 6.89 (4.49) | 49.42 (18.79) |

| Postgraduate | 8.43 (4.60) | 20.06 (7.12) | 14.75 (4.45) | 7.02 (4.85) | 50.28 (16.45) |

| 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.24 | 0.87 | 0.77 | |

| School type* | |||||

| Government | 7.92 (5.14) | 20.31 (7.04) | 14.82 (4.86) | 6.39 (4.68) | 49.45 (15.08) |

| Private | 8.66 (4.35) | 20.03 (7.88) | 14.25 (4.67) | 7.17 (6.28) | 50.12 (18.12) |

| 0.39 | 0.85 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.84 | |

| Experience in teaching** | |||||

| 0-5 years | 7.62 (4.57) | 19.00 (8.63) | 14.28 (4.86) | 6.53 (5.35) | 47.42 (19.66) |

| 6-10 years | 8.59 (4.29) | 20.66 (6.97) | 14.48 (4.54) | 7.30 (3.96) | 51.03 (15.79) |

| >10 years | 9.23 (4.82) | 20.59 (7.39) | 14.41 (4.88) | 7.02 (4.90) | 51.25 (16.67) |

| 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.48 | |

| Subjects taught* | |||||

| Physical education or science | 8.13 (4.64) | 21.30 (7.18) | 15.21 (4.52) | 8.11 (3.89) | 52.75 (16.55) |

| Others | 8.66 (4.53) | 19.44 (7.85) | 13.94 (4.78) | 6.33 (5.01) | 48.36 (17.65) |

| 0.50 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.14 | |

| Classes taught** | |||||

| Primary classes | 7.41 (4.54) | 17.66 (9.62) | 13.88 (6.18) | 5.07 (4.98) | 44.02 (21.93) |

| Secondary classes | 10.25 (4.84) | 22.67 (6.34) | 13.75 (4.41) | 7.33 (4.69) | 54.00 (14.89) |

| Senior secondary classes | 8.47 (4.37) | 20.58 (6.56) | 14.84 (3.89) | 7.82 (4.33) | 51.72 (14.68) |

| 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.43 | < 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| Prior Exposure to mental health issues* | |||||

| Yes | 7.75 (4.51) | 18.43 (7.59) | 14.03 (4.47) | 6.38 (4.64) | 46.6 (16.33) |

| No | 8.96 (4.45) | 21.26 (7.51) | 14.64 (4.88) | 7.38 (4.84) | 52.25 (17.73) |

| 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

*Independent t-test, **one-way analysis of variance test. SD, standard deviation

DISCUSSION

Attitude toward mental illness is an important factor influencing mental health. Many studies have been conducted to study the negative beliefs, attitudes, and stigma associated with mental health in India and around the world, but very few studies have been conducted in the teacher’s population. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the very few studies conducted till now in India which assesses the beliefs of teachers. This study investigated the beliefs of teachers toward mental illness using a questionnaire survey. In this study, more than 80% of the teachers showed moderate and high scores on belief toward mental illness scale. This highlights the negative beliefs about mental illness among the study population. These findings are concordant with the previous studies conducted among higher secondary school teachers in Ahmedabad and Puducherry, India, highlighting negative attitudes and stigma among the teachers.[17,18] The mean BMI score of the study population in this study came out to be approximately 50 which is very much similar to the scores of the study conducted in Istanbul among primary school teachers using the same instrument.[24] After exploring the subscale dimensions, the study population showed more negative beliefs on the dimension of social dysfunction dealing with the beliefs on failure in fulfilling the responsibilities and social roles by people suffering from mental illnesses. The beliefs held by the study population could be due to the fact that unless trained specifically, they are an integral part of the general community, and therefore have imbibed the beliefs prevalent in the general society. Perpetuating negative beliefs about mental illness in the general community are highlighted by the different community-based studies conducted in different parts of India.[25,26]

There is evidence of the impact of characteristics such as age, gender, and educational level on beliefs and attitude.[27,28] However, in this study, any significant effect of gender, age, marital status, and educational qualification on beliefs toward mental illness could not be detected. Few studies have also reported no significant difference in beliefs among their study populations on the basis of age, gender, or marital status.[18,29] The sociocultural factors are more prevalent in the rural areas such as superstitious beliefs of linking the causation of mental illness with supernatural powers.[30] In this study, residence in the rural area displayed significant findings of negative beliefs as compared to semi-urban and urban areas.

School-related factors such as type of school in which they are teaching, years of experience, and subjects taught were not associated with the beliefs. However, this study showed significantly less negative beliefs among the teachers teaching the primary classes as compared to secondary and senior secondary classes. To our knowledge, no studies have found or specifically explored differences in beliefs, knowledge, or attitude among the teachers teaching the primary, secondary, and senior secondary classes. This finding needs to be explored further. Many studies have highlighted the issue of depression, anxiety, and stress among secondary and senior secondary students in India primarily due to academics.[31-33] In such cases, teachers teaching such students are in a unique position of identifying such students, providing support to them, and helping them in receiving timely apt interventions. However, lacunae in their knowledge of mental issues and negative beliefs perpetuating among them can adversely affect their role and the golden opportunity to catch such students at an early stage could be missed.

More positive attitudes were displayed by the people with personal experience of mental health.[34] In this study, prior exposure to mental health issues was found to be significantly associated with positive beliefs. Those who had not any prior exposure in terms of mental health showed more negative beliefs. This was in similar lines as highlighted by the study conducted among Turkish physiotherapy students in which students having a relationship with an individual having a mental problem showed less negative beliefs.[22] In a meta-analysis to examine the effects of antistigma approaches, exposure in terms of education and contact with mentally ill persons have been considered as an effective strategy to reduce stigma toward mental illness.[35] Both retrospective and prospective interaction with the people who have mental illness tends to diminish stigmatizing attitudes and negative beliefs about mental illness.[36] More positive beliefs among those having prior exposure to mental health issues hints toward the opportunity for interventions such as interactions with the mentally ill people in which people share their experience and views about the illness, to reduce the stigma associated with mental illness.

However, there are few limitations of this study. The calculated sample size of 180 could not be achieved due to rising COVID-19 cases in the area. However, the sample size was adequate for the findings on beliefs about mental illness, because of less nonresponse (around 8%) than expected (50%). The self-reported nature of the questionnaire has its own limitation of ‘desirability bias’ in which participants are more likely to respond in a manner that is more socially desirable.[37]

CONCLUSION

This study indicated that there are negative beliefs about mental illness among the study population and there is a need for training among the study population. Participants residing in rural areas showed more negative beliefs. Primary school teachers and those having prior exposure to mental health issues showed comparatively more positive beliefs.

IMPLICATIONS

More studies should be conducted to explore the beliefs about mental illness among the teachers. This study brings to light the important interventions like creating knowledge and awareness among the study population by conducting trainings. Training the teachers could benefit in two ways. First, by improving their knowledge and awareness, we can strengthen the school-based screenings of the students who are at risk and provide timely interventions minimizing the future burden. Second, schools provide an ideal environment for students to learn and imbibe values and beliefs from role models, such as teachers. So teachers will influence their students positively and the pool of the generation will be better aware of the mental health issues and will reduce the stigmatization of mental illness and make society more acceptable to the mentally ill.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Adolescent mental health. 2020. [[Last accessed on 2021 Jun 15]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health .

- 2.Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, De Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Gasquet I, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sagar R, Dandona R, Gururaj G, Dhaliwal RS, Singh A, Ferrari A, et al. The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:148–61. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malhotra S, Patra B. Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2014;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370:878–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bright P. Stigma and mental illness: A review and critique. J Ment Health. 2009;6:345–54. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne P. Stigma of mental illness and ways of diminishing it. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2000;6:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman M. The stigma of mental illness is making us sicker. Psychology Today. 2014. [[Last accessed on 2021 Jun 15]]. Available from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brick-brick/201405/the-stigma-mental-illness-is-making-us-sicker .

- 10.Sood A. The Global Mental Health movement and its impact on traditional healing in India: A case study of the Balaji temple in Rajasthan. Transcult Psychiatry. 2016;53:766–82. doi: 10.1177/1363461516679352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Adolescent mental health. 2019. [[Last accessed on 2021 Sep 15]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health .

- 12.Auger RW. The accuracy of teacher reports in the identification of middle school students with depressive symptomatology. Psychol Sch. 2004;41:379–89. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langeveld J, Joa I, Larsen TK, Rennan JA, Cosmovici E, Johannessen JO. Teachers'awareness for psychotic symptoms in secondary school: The effects of an early detection programme and information campaign. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5:115–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Prevention of Mental Disorders. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Caring for children and adolescents with mental disorders: Setting WHO directions. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamel A, Haridi HK, Alblowi TM, Albasher AS, Alnazhah NA. Beliefs about students'mental health issues among teachers at elementary and high schools, Hail Governorate, Saudi Arabia. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2020;27:30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkataraman S, Patil R, Balasundaram S. Stigma toward mental illness among higher secondary school teachers in Puducherry, South India. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8:1401–7. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_203_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parikh N, Parikh M, Vankar G, Solanki C, Banwari G, Sharma P. Knowledge and attitudes of secondary and higher secondary school teachers toward mental illness in Ahmedabad. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;32:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zieger A, Mungee A, Schomerus G, Ta TM, Dettling M, Angermeyer MC, et al. Perceived stigma of mental illness: A comparison between two metropolitan cities in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:432–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shekhawati region fast emerging as education hub | Jaipur News-Times of India. The Times of India. 2020. [[Last accessed on 2022 Dec 19]]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/jaipur/shekhawati-region-fast-emerging-as-edu-hub/articleshow/79481493.cms .

- 21.Sikar district-Wikipedia. Sikar district-Wikipedia. 2019. [[Last accessed on 2022 Dec 19]]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sikar_district .

- 22.Yildirim M, Demirbuken I, Balci B, Yurdalan U. Beliefs towards mental illness in Turkish physiotherapy students. Physiother Theory Pract. 2015;31:461–5. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2015.1025321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirai M, Clum GA. Development, reliability, and validity of the beliefs toward mental illness scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2000;22:221–36. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gur K, Sener N, Kucuk L, Cetindag Z, Basar M. The beliefs of teachers toward mental illness. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;47:1146–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu R, Sau A, Saha S, Mondal S, Ghoshal PK, Kundu S. A study on knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding mental health illnesses in Amdanga block, West Bengal. Indian J. Public Health. 2017;61:169. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_155_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salve H, Goswami K, Sagar R, Nongkynrih B, Sreenivas V. Perception and attitude towards mental illness in an urban community in south Delhi-A community based study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:154–8. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.116244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breuer C. High School Teachers’ Perceptions of Mental Health and Adolescent Depression. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Midlarsky E, Pirutinsky S, Cohen F. Religion, ethnicity, and attitudes toward psychotherapy. J Relig Health. 2012;51:498–506. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9599-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jombo HE, Idung AU, Iyanam VE. Attitudes, beliefs and social distances towards persons with mental illness among health workers in two tertiary healthcare institutions in Akwa Ibom State, South-South Nigeria. Int J Health Sci Res. 2019;9:252–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauber C, Rössler W. Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:157–78. doi: 10.1080/09540260701278903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar KS, Akoijam BS. Depression, anxiety and stress among higher secondary school students of Imphal, Manipur. Indian J Community Med Off Publ Indian Assoc Prev Soc Med. 2017;42:94–6. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_266_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porwal K, Kumar R. A study of academic stress among senior secondary students by Kartiki Porwal. Int J Indian Psychol. 2014;1:133–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prabu PS. A study on academic stress among higher secondary students. Int J Humanities Soc Sci Interv. 2015;4:63–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brockington IF, Hall P, Levings J, Murphy C. The community's tolerance of the mentally ill. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 1993;162:93–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2012;63:963–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Couture S, Penn D. Interpersonal contact and the stigma of mental illness: A review of the literature. J Ment Health. 2003;12:291–305. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salters-Pedneault K. Can psychological self-report information be trusted? Verywell Mind. [[Last accessed on 2021 Jan 06]]. Available from: https://www.verywellmind.com/definition-of-self-report-425267 .