Abstract

Canadian beekeepers faced widespread levels of high honey bee colony mortality over the winter of 2021/2022, with an average winter loss of 45%. To understand the economic impact of winter colony mortality in Canada and the beekeeping management strategies used to mitigate these losses, we develop a profit model of commercial beekeeping operations in Alberta, Canada. Our model shows that for operations engaging in commercial pollination as well as honey production (compared to honey production alone), per colony profit is higher and operations are better able to withstand fluctuations in exogenous variables such as prices and environmental factors affecting productivity including winter mortality rates. The results also suggest that beekeeping operations that replace winter colony losses with splits instead of package bees accrue higher per colony profit than those importing packages to replace losses. Further, operations that produce their own queens to use in their replacement splits, accrue even higher profit. Our results demonstrate that the profitability of beekeeping operations is dependent on several factors including winter mortality rates, colony replacement strategies, and the diversification of revenue sources. Beekeepers who are not as susceptible to price and risk fluctuations in international markets and imported bee risks accrue more consistently positive profits.

Keywords: honey bee, colony loss, imported stock, beekeeping profit, pollination

Introduction

Canadian beekeepers manage approximately 765,000 honey bee colonies that produce nearly 75 million pounds of honey worth 253 million dollars (Stats Can 2022). Many of these colonies make an annual contribution to the pollination of agricultural crops such as canola and blueberries worth an estimated 4.5–6.1 billion dollars (adjusted for inflation; AAFC 2020, Stats Can 2021). The Western Canadian Province of Alberta produces over 30 million pounds of honey (nearly double that of any other province) and is the center of the lucrative canola seed production industry worth nearly 3 billion dollars in farm cash receipts between 2017 and 2021 (AAFC 2020). In 2022, there were 1,700 beekeepers managing 300,500 honey bee colonies in Alberta, representing 39% of all Canadian colonies (Stats Can 2021). However, fewer than 200 of these Alberta beekeeping operations operate over 100 colonies and are considered commercial operations (S. Muirhead, Alberta Provincial Apiculturist, personal communication, 14 July 2022). Approximately 55,000 to 75,000 honey bee colonies are rented out annually for hybrid canola seed pollination in Alberta, representing nearly 20% of all honey bee colonies in this province (Laate et al. 2020, Stats Can 2021, Alberta Beekeepers Commission, personal communication 1 August 2022, Alberta Beekeepers Commission, personal communication 1 August 2022). Between 2017 and 2021, Alberta honey bee colonies produced an average of 114 lbs of honey per colony, with the 2021 average being 110 lbs per colony (Stats Can 2021). However, honey production is regional. In the Peace region of northern Alberta, the average colony produced 147 lbs of honey in 2020 (Emunu 2020). While honey production is the dominant economic driver of commercial beekeeping in northern Alberta, canola seed production fields are exclusively located in southern Alberta. Pollinating this crop requires travel for beekeepers to scout, manage, and transport colonies before, during, and after pollination. In addition, a subset of commercial beekeepers from across the province also sends colonies to the neighboring province of British Columbia to overwinter and pollinate highbush blueberries, incurring higher transportation costs.

Honey bee colonies in Canada and around the world have experienced significant winter mortality rates over the past few decades due to several environmental and biological factors including the parasitic mite, Varroa destructor (Guzman-Novoa et al. 2010, Le Conte et al. 2010), and honeybee queen health (CAPA 2010, Genersch et al. 2010, Spleen et al. 2013, vanEnglesdorp 2013, Liu, et al. 2016, Bixby et al. 2019, Brown and Robertson 2019). Canadian beekeepers reported an average winter colony mortality of 45% in 2022 and a 15-yr average loss rate of 27% (CAPA 2022). US beekeepers have also experienced significant levels of winter mortality recently, with an estimated 24% loss over the 2021–2022 winter and a 33% loss the previous year (BIP 2022). The province of Alberta has experienced significant winter losses; nearly 50% of Alberta honeybee colonies died over the winter of 2021–2022 with an average colony mortality of over 37% since 2018 (CAPA 2022). Losing nearly half of all honeybee colonies in Alberta over the winter of 2021/2022 required large-scale colony replacements. It is important to consider that winter losses may be driven by the larger number of hobbyist beekeepers in Alberta, however, winter loss statistics are not specific to operation size. Further research parsing out the contribution towards winter loss by operation type and size would be illuminating. Historically, some Alberta beekeepers would kill their colonies in the autumn and import honey bee packages (1–2 kg of bees shipped in a cardboard or wooden container and installed in a hive) from beekeeping operations in the southern United States the following spring as replacements. These packages did not require overwintering and provided a replacement strategy for beekeepers until their importation was prohibited in 1987 due to importation risks (CFIA 2013). More recently, beekeepers in Alberta replace 75% of their dead colonies by splitting existing colonies within their operation and replacing the remaining 25% of losses with package bees imported from Australia, New Zealand, and Chile (Bixby et al. 2020, Laate et al. 2020). Colony losses occur at the beginning of the spring season, potentially in time for the beekeeper to have replacements (splits or packages) that will be productive that season. However, since population size and brood production are correlated with honey production (Farrar 1937, Szabo and Lefkovitch 1988, Pernal et al. 2008, Gabka 2014), the larger overwintered colonies will tend to produce more honey than the splits.

In an attempt to put these winter losses into context, several apicultural studies in Canada, the United States, and internationally have referenced a 1952 USDA publication (Currie et al 2010, AWLR 2018, Ferrier et al. 2018, Maucourt et al. 2018, Bixby et al. 2020) in which apiculturist C.L. Farrar suggests that a rate of 15% winter colony mortality would be economically sustainable by resulting in non-negative profits for a honeybee colony (Farrar 1952, Furgula 1992, Furgula and McCutcheon 1992). Despite the lack of any accompanying data or empirical study, Farrar’s 15% threshold has been widely accepted in apicultural circles as a benchmark for sustainable colony winter mortality. Since the Farrar publication in 1952, there have been no subsequent analyses of the economic impact of winter losses on colony profit. This paper presents a quantitative economic model that estimates the profit of commercial Alberta beekeeping operations given a range of winter colony mortality rates, colony replacement methods, and various management scenarios. We explore winter colony mortality and its impact on profitability through both estimating profit given colony loss rates and estimating the winter colony mortality rate at which an operation is no longer profitable. The objective of this study is to develop a model based on empirical beekeeping data to better understand how winter colony losses, management scenarios, and replacement strategies affect the profitability of beekeeping operations, using commercial operations in Alberta, Canada as a model location. Our intention is to provide a quantitative foundation of how winter colony loss and management decisions affect profitability for the apicultural community.

Methods and Materials

For this analysis, we describe a commercial honey and/or commercial pollinating operation based in northern Alberta, Canada. In our model, a representative beekeeping operation produces and sells honey from their colonies. In addition to honey production, the beekeeping operation in our analysis can choose to rent colonies to canola seed companies to fulfill pollination contracts each summer or can send colonies to British Columbia for blueberry pollination. Although in practice, a single honey bee colony can be rented for multiple pollination contracts in a single season, each colony in our representative beekeeping operation engages in only one commercial pollination contract per season, either canola or blueberry, as this is the more common practice in Alberta. Beekeeper profit is broken down into total revenues accrued from honey production and pollination rentals. Total costs include operation costs to feed and maintain a healthy colony as well as replacement costs for any lost colonies, which may include a purchased package of bees or making a split from an existing colony to create 2 colonies. We assume that the package of bees arrives with a queen and that for the split, the beekeeper must either use a queen from their own operation (paying the cost of queen production) or purchase a domestic or imported queen at the current market price. For the modeling scenarios, we explore a range of winter losses that reflect recent colony mortality in Alberta: colony mortality rates in the model range from 15%, a mortality rate often referenced in apicultural literature; to 29%, a 5-yr low occurring in 2019; to 37%, a 5-yr average (2018–2022); to 50%, the 2022 winter loss rate. The revenue, cost, and profit functions for a representative commercial beekeeper in Alberta are below.

-

A) The beekeeper’s total revenue, total cost, and profit functions for a beekeeper using packages to replace lost colonies:

Total Revenue (TR):

| (1) |

Total Cost (TC):

| (2) |

Profit (π):

| (3) |

Where N is the total number of colonies in the operation, is the number of dedicated honey producing colonies, is the number of commercially pollinating colonies and

| (4) |

-

B) The beekeeper’s total revenue, total cost, and profit functions for a beekeeper making splits to replace lost colonies:

Total Revenue (TR):

| (5) |

Total Cost (TC):

| (6) |

Profit: TR-TC

| (7) |

Equations (1) and (5) describe the revenue accrued to the beekeeper from honey production and pollination rentals, equations (2) and (6) describe the total cost incurred by the beekeeper to maintain these colonies, and equations (3) and (7) represent the operation’s profit. Tables 1 and 2 present the parameter values used in the profit analysis. We assume the representative beekeeping operation assesses their colonies for overwintering mortality in the early spring and the beekeeper chooses between replacing all lost colonies with either packages or splits. This is a simplifying assumption that allows us to measure the preliminary impact of replacement decisions on profitability, however, future modeling of complex replacement strategies including timing of replacement and/or a mix of packages and splits would be valuable. Based on empirical studies, when the beekeeper replaces lost colonies with packages early in the season, our model assumes the packages build up in a time to produce 87% of the honey that a successfully overwintered colony would produce (Nelson and Jay 1982, Pernal et al. 2008). When the beekeeper replaces a lost colony with a split, we assume that an existing colony is split in 2 with both parent and offspring colonies producing 75% of the amount of honey that the dedicated honey producing colonies produce that season based on evidence that there is a later buildup resulting in a delayed honey crop (Farrar 1937, Szabo and Lefkovitch 1988, Pernal et al. 2008, Gabka 2014). Based on recent data from beekeepers in Alberta, colonies that engage in commercial canola pollination contracts produce on average two-thirds the amount of honey produced by non-commercially pollinating colonies in Alberta (Emunu 2020, S. Hoover 2022 unpublished data). As a result, in our analysis, when a colony is rented out for pollination, they produce 68% of the honey produced by a non-commercially pollinating colony. The average number of honey-producing colonies per beekeeping operation in Alberta in 2016 was 719, whereas the average number of honey production colonies per beekeeping operation in the Peace region was substantially higher at 1205. The number of colonies managed per commercial pollinating operation was even higher, at 3157 (Laate 2017). In our study, we are focused on the economic impact of winter losses affecting commercial beekeeping operations and as a result, our representative beekeeping operation manages 3,000 colonies. When we introduce commercial pollination, 1,500 colonies remain in dedicated honey production and 1,500 colonies are rented for either canola or blueberry pollination while still producing a reduced honey crop. Historically, honey prices have been variable in Canada. From 2016 to 2020, honey prices in Canada rose from $1.78/lb to $3.04/lb (Stats Can 2021), a 70% increase in 6 yr, with inflation accounting for only half of that. In 2022, Canada produced 74,394,000 lbs of honey, valued at $253,505,000, a per pound price of $3.41 (Stats Can 2022). In Alberta, honey prices have increased recently from $1.76/lb in 2017 to $3.11 in 2022 (Stats Can 2022). The initial honey price used for our analysis is consistent with the all-time high 2022 honey price in Alberta of $3.11/lb (Stats Can 2022). Between 2017 and 2021, Alberta honey bee colonies produced an average of 114 lbs of honey per colony, with the 2021 average being 110 lbs per colony (Stats Can 2021). However, in the Peace region of northern Alberta, the average colony produced 147 lbs of honey in 2020, a relatively high average yield compared to the province (Emunu 2020, Stats Can 2022). The rental rates for commercial pollination range from $120 per colony for blueberries in British Columbia (Bee CSI data 2020) to $245 per colony for canola in Alberta (Alberta Beekeepers Commission (ABC) unpublished data 14 July 2022), rates that are subject to market fluctuations. Alberta beekeepers reported purchasing packages in bulk in the spring, with the average beekeeping operation importing 40 packages a year at a bulk package price of $240/package (Emunu 2020, UBS 2020, WCBS 2022). In 2016, an economic study of beekeeping in Alberta reported that the average cost of production on a colony level in Alberta was consistent for colonies in commercial honey production and commercial pollination (Laate 2017). The operating cost for a beekeeper to maintain a honey bee colony in Alberta was estimated to be $248 in 2016, or $280 when adjusted for inflation today (Laate 2017). When making splits to replace colony losses, the total labor to make the split including transportation to the yard, finding the queen, and preparing the equipment, was estimated to be half an hour (Heather Higo, President BC Honey Producers Association, personal communication, 25 April 2022) at a wage of $20/h (Laate et al. 2020), for a total cost of $10/split. The time it takes to make a split depends on the beekeeper’s experience, travel distances, and other variables. All other costs to maintain the split colonies are included in the operating cost per colony. The price to purchase an imported or domestic queen for our beekeeper is $45/queen, a price that is consistent with the current retail market as well as the 2020 Alberta survey results (Laate 2020, CBS 2023, DBE 2023, RQ 2023). If the beekeeper produces their own queens within their operation, we assign a cost to this production of $18.75/queen, an inflation-adjusted cost based on a recent Canadian queen production cost case study (Bixby et al. 2019). Different queen producers will have a range of production costs, and these should be factored into any customized economic analysis. When an operation loses more than 50% of their colonies, replacing with splits is not typically feasible as remaining colonies are likely not adequately strong given the high losses. As well, these weakened colonies would need to be split multiple times to compensate for the high mortality levels, an unviable practice. In our model, when the beekeeper replaces losses with splits and mortality rates are greater than 50%, we assume that the beekeeping operation will be required to choose an alternate replacement strategy (i.e., packaged bees).

Table 1.

Variables for initial profitability analysis

| Price of honey per pound ($/lb) | |

| Honey yield per colony (lbs/colony) | |

| Rental price per colony pollinating either canola or blueberries ($/colony) | |

| Cost to purchase a package of bees ($/package) | |

| Proportion of colonies that die in each winter season | |

| Additional costs (proportion) to manage commercial pollinating colonies (including supplementary fuel, feed, labor etc.) | |

| Operating cost for a colony ($/colony) | |

| Proportion of honey produced by the parent and offspring split colonies each year compared to a successfully overwintered colony | |

| Proportion of honey that the colony replaced with a package produces each year compared to a successfully overwintered colony | |

| Proportion of total honey produced by the commercial pollinating colonies compared to an overwintered dedicated honey producing colony | |

| Cost (labor only) of making a split ($/split) | |

| Price to purchase a queen ($/queen) | |

| Cost for the beekeeper to produce their own queen within their operation ($/queen) | |

| Number of colonies used in dedicated honey production (h) and honey with commercial pollination (p) |

Table 2.

Variable parameter values for initial profitability analysis

| Model variables | Initial profit model scenarios | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1

Honey-Split |

2

Honey-Package |

3

Honey Canola- Split |

4

Honey Canola-Package |

5

Honey Blueberry-Split |

6

Honey Blueberry- Package |

||||

| Winter loss, | Losses range from Alberta’s 5-yr low of 29% (2019) to 37% (5-yr average), to the 5-yr high mortality rate in Alberta of 50% (2022), as well as 15%, an often- cited sustainability threshold | ||||||||

| # Honey colonies, | 3,000 | 3,000 | 1,500 | 1,500 | 1,500 | 1,500 | |||

| # Pollination Colonies, | 0 | 0 | 1,500 | 1,500 | 1,500 | 1,500 | |||

| Price of honey ($/lb), | $3.11 | $3.11 | $3.11 | $3.11 | $3.11 | $3.11 | |||

| Full honey yield (lbs), | 147 lbs | 147 lbs | 147 lbs | 147 lbs | 147 lbs | 147 lbs | |||

| Rental Fee Can ($/Col), | n/a | n/a | $245 | $245 | n/a | n/a | |||

| Rental Fee Blue ($/Col), | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | $120 | $120 | |||

| % Full honey yield-pollinating, a | n/a | n/a | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.68 | |||

| % Full honey yield-split, | 0.75 | n/a | 0.75 | n/a | 0.75 | n/a | |||

| % Full honey yield-package, | n/a | 0.87 | n/a | 0.87 | n/a | 0.87 | |||

| Package cost ($/pckg), | n/a | $240 | n/a | $240 | n/a | $240 | |||

| Cost of split ($/split), b | $10 | n/a | $10 | n/a | $10 | n/a | |||

| Price of queen ($/queen), | a.Buy Queen | $45 | n/a | a.Buy Queen | $45 | n/a | a.Buy Queen | $45 | n/a |

| Production cost of queen ($/queen), | b.Own Queen | $18.75 | n/a | b.Own Queen | $18.75 | n/a | b.Own Queen | $18.75 | n/a |

| Operating cost ($/col), | $280 | $280 | $280 | $280 | $280 | $280 | |||

aFull honey yield is the amount of honey produced by a surviving/strong overwintered colony in the operation.

bSplit cost is labor only, based on 30 min labor @ $20/h.

Sensitivity Analysis

Several of the model’s initial parameter values capture a snapshot of current environmental and market conditions, however, variability in parameter values is common. Honey yield and honey price fluctuate dramatically from year to year with these variations having an effect on an operation’s profitability. To evaluate the effect of these and other parameter values’ variability on colony profit, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. Table 3 shows the parameter values used in the sensitivity analysis. (A) represents the initial values used in the economic model and (B) and (C) represent increases or decreases in the values to reflect fluctuations in specific revenue and cost variables. Parameter values for honey yield and price are adjusted in the sensitivity analysis based on recent data from Alberta beekeepers (Emunu 2020, Stats Can 2021). Honey price decreases from $3.11/lb to $2.51 (5 yr avg) and $1.97 (2018) in the sensitivity analysis reflects lower prices in Alberta in recent years. Honey yield is a function of many factors including environmental variables such as weather, colony health, and management, resulting in variability in honey yield from year to year (Stats Can 2021). Honey yield adjustments in the model mirror regional variability: from 147 lbs/colony in 2020 to 114 lbs/colony (5 yr average) to 100 lbs/colony (5-yr low). The model includes a variable that captures a cost for commercially pollinating colonies in addition to the operating cost to maintain a honey production colony. Many Alberta beekeepers who send bees into commercial pollination incur additional costs to prepare and transport bees to fulfill canola and blueberry pollination contracts. In northern Alberta, bees are often sent either to the south for canola pollination or into British Columbia for overwintering and highbush blueberry pollination, requiring higher fuel costs and increased travel costs including increased wages for workers to accompany colonies. Since 2016, gas prices in Alberta have increased by 100% from 1.02 cents/liter in June 2016 to 2.04 cents/liter in June 2022 (NJC 2016, Stats Can 2022), further increasing the cost of transporting pollinating colonies. Alberta beekeepers who currently engage in commercial pollination have reported that in addition to the higher transportation costs, there are other costs associated with commercial pollination including preparing colonies for pollination inspections as stronger colonies accrue a higher rental premium requiring additional feed, as well as additional labor costs associated with managing colonies before, during and after colonies are in the pollination fields (Sagili and Burgett 2011, Jeremy Olthof, Past President, Alberta Beekeepers Commission and commercial pollinator, personal Communication, 6 June 2022). Recent unpublished survey data also suggests that commercially pollinating colonies require higher treatment costs than honey production colonies (Bixby et al. 2023 unpublished data). For this analysis, the additional pollination cost parameter adds 25% and 50% in total operating costs per commercially pollinating colony. These increases in cost are likely lower bound estimates of the increase in total costs to prepare and manage a commercial pollinating colony in Alberta, particularly as honey bee health risks from pesticide exposure and transportation are not explicitly being considered. Per colony operating costs are function of labor and other costs such as fuel and equipment that have been highly variable in recent years. Operating costs are increased/decreased by 25% in the sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of higher and lower costs to manage a colony (as feed, treatment, labor, and other costs change overtime). Even at a 50% increase in operating cost, the per colony cost of $350 may not reflect the full increase in beekeeping costs in some years. Based on higher recent input prices such as labor, fuel, equipment, and housing among others, a recent Canadian beekeeping survey suggests that actual operating costs may be significantly higher (Bixby 2023, unpublished data). As the risk of pollination deficiencies proliferates with the loss of available pollinators (Li et al. 2022), there is likely to be an increased demand and price to rent pollinating colonies in certain markets. Conversely, in some Canadian markets, pollination-dependent crop producers have expressed that their industry’s increasing operating costs necessitate lower rental rates, resulting in potentially lower pollination fees (Miriam Bixby 2023, unpublished data), a discrepancy that is captured in the model with 25% increases and 25% decreases in pollination rental fees. Beekeepers can purchase local queens or can import queens from outside of Canada, however this latter practice poses additional risks to queen health and productivity (CFIA 2013, Pettis et al. 2016, McAfee et al. 2020). Purchased queen prices (domestic and imported) have been increasing in recent years (Bixby et al. 2020) and are adjusted in the model to reflect increasing health risks in queens, increasing costs of production as well as international market fluctuations. Increases in the cost of purchased queens are captured with a 25% and 50% increase in queen purchase costs. Packaged bees are primarily imported into Canada from Australia, New Zealand, or Chile, carrying additional importation and transportation risks (Kiheung et al. 2012). The impact of greater health risks from importation for packages bees is explored through a 25% and 50% higher costs in the sensitivity analysis.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis parameter values

| Honey price, Ph ($/lb) | Honey yield, Qh (lbs/co) | Addt’l pollination costs, | Operating costs, Cop ($/col) | Canola rental fees, PRc ($/col) | Blueberry rental fees, PRb ($/col) | Purchased queen cost, pq ($/Q) | Imported package cost, cpk ($/pckg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Initial | $3.11 | 147 lbs | 0 | $280 | $245 | $120 | $45 | $240 |

| B. Value | $1.97 (2018) | 114 lbs (ABa5-yr avg) | 0.25 | $210 (−25%) | $184 (−25%) | $90 (−25%) | $56.25 (+25%) | $300 (+25%) |

| C. Value | $2.51 (5-yr avg) | 100 lbs (5-yr low 2019) | 0.50 | $350 (+25%) | $306 (+25%) | $150 (+25%) | $67.5 (+50%) | $360 (+50%) |

aAB stands for the province of Alberta.

Results

Initial Parameter Results

Our model demonstrates that profit in beekeeping operations is a function of winter colony mortality, management decisions about replacement strategies, and the types of activities that provide revenue to the operation. As would be predicted, with increasing winter losses, our model shows profits decreasing for each activity and replacement strategy scenario. The per colony profit associated with a specific rate of colony winter loss as well as each modeling scenario for beekeeping by activity type (honey only, honey, and canola/blueberry pollination) and colony replacement strategy (package, split with a purchased queen, and split with an in-house queen) is shown in Table 4. The winter colony mortality rate at which an operation’s profit is zero is also included. Given the initial parameter values, for an operation focused on honey production and no commercial pollination, per colony profit ranges from $27 with a 50% loss rate (5 yr maximum) and package replacement, to $103 with a 29% winter loss rate (5 yr low), and $139 with 15% colony winter loss rate, both using a replacement strategy of making splits and using in-house queens. For an operation renting colonies for canola pollination, per colony profit ranges from $67 at a 50% overwinter loss rate using package replacement, to $163 at 29% winter loss, and $193 at 15% colony winter mortality, both scenarios again making splits with in-house queens to replace lost colonies. For an operation renting colonies for blueberry pollination, per colony profit ranges from $4 when 50% of colonies are lost over winter and packages are used to replace losses, to $100 at a 29% winter mortality rate and $131 at 15% colony loss, both with splits and in-house queens as the replacement strategy. The results in Table 4 show that for all mortality rates, profit is highest when replacing winter losses with splits, and particularly if using an in-house queen. The lowest profit accruing in each activity and winter mortality is those operations that replace colony losses with package bees. Those operations that rent colonies for canola pollination are the most profitable, with blueberry pollination in most cases more profitable than an operation focusing on honey production alone. For all management and replacement scenarios, operations accrue non-negative profits at 50% loss or greater.

Table 4.

Profit model results: initial values

| Initial profit model scenarios | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Honey-split |

2 Honey-package |

3 Honey canola-Split |

4 Honey canola-package |

5 Honey blueberry-split |

6 Honey blueberry-package |

||||

| Winter Loss, | Profit ($/Colony) | ||||||||

| Buy Queen | Own Queen | Queen included | Buy Queen | Own Queen | Queen included | Buy Queen | Own Queen | Queen included | |

| 15% loss | $135 | $139 | $132 | $189 | $193 | $158 | $127 | $131 | $95 |

| 29% loss | $95 | $103 | $90 | $155 | $163 | $121 | $92 | $100 | $59 |

| 37% loss | $72 | $82 | $66 | $135 | $145 | $101 | $73 | $82 | $38 |

| 50% loss | $35 | $49 | $27 | $103 | $116 | $67 | $41 | $54 | $4 |

| Zero-profit threshold | >50%a | >50%a | 59% | >50%a | >50%a | 76% | >50%a | >50%a | 52% |

aDue to reduced colony numbers and colony health, when colony mortality rates exceed 50%, our representative beekeeper will replace lost colonies with packages instead of splits.

Sensitivity Analysis Results

Table 5 shows the initial (A) per colony profit and zero-profit winter loss threshold under each scenario and lists the per colony profit and zero-profit winter colony loss threshold with the adjusted parameter values (B, C). All profit is calculated at a 37% winter colony loss rate. As expected, with a lower honey price and lower honey yield, profit decreases, with the amount of reduction in profit a function of parameter values, beekeeping activity, and replacement strategy. For those operations focusing on honey production and producing honey while renting colonies for blueberry pollination, a honey price of $1.97/lb accrues no positive profits in any of the scenarios, with a zero-profit winter colony loss of 15% or below, a winter loss rate 14 points below the 16-yr Alberta average and 22 points below the 5-yr Alberta average. At a price of $2.51/lb, only operations engaging in canola pollination accrue positive profits in all scenarios, however, profits fell significantly from the initial honey price of $3.11. At a honey price of $2.51/lb, operations focused on honey production and honey with blueberry pollination rentals have negative per colony profit with package replacement and per colony profit ranging from $0 to $22 depending on the replacement scenario and beekeeping activity.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis: per colony profit and zero-profit winter colony loss results based on a range of parameter values

| Sensitivity analysis: profit model results | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Honey-split |

2 Honey-package |

3 Honey canola-split |

4 Honey canola-package |

5 Honey blueberry-split |

6 Honey blueberry-package |

||||

| 37% Winter loss | Profit ($/Colony) | ||||||||

| Buy queen | Own queen | Queen included | Buy queen | Own queen | Queen included | Buy queen | Own queen | Queen included | |

| A. Initial 0-profit Loss % |

$72 >50% |

$82 >50% |

$66 59% |

$135 >50% |

$145 >50% |

$101 76% |

$73 >50% |

$82 >50% |

$38 52% |

| Honey price, Ph ($/lb) Initial value: $3.11 | |||||||||

| B. $1.97 0-profit Loss % |

−$64 5% |

−$54 6% |

−$93 3% |

$20 49% |

$30 >50% |

−$27 26% |

−$42 13% |

−$32 15% |

−$89 2% |

| C. $2.51 0-profit Loss % |

$0 37% |

$10 42% |

−$18 31% |

$75 >50% |

$84 >50% |

$34 50% |

$12 43% |

$22 49% |

−$29 26% |

| Honey yield, Qh (lbs/col) Initial value: 147 lbs | |||||||||

| B. 114 lbs 0-profit Loss % |

−$11 32% |

−$2 37% |

−$31 26% |

$65 >50% |

$75 >50% |

$23 46% |

$2 38% |

$12 44% |

−$40 21% |

| C. 100 lbs 0-profit Loss % |

−$47 15% |

−$37 17% |

−$73 11% |

$35 >50% |

$45 >50% |

−$10 33% |

−$27 22% |

−$18 26% |

−$73 8% |

| Pollination costs, Initial value: $0 | |||||||||

| B. 0.25 0-profit Loss % |

n/a | n/a | n/a | $100 >50% |

$110 >50% |

$66 62% |

$38 >50% |

$47 >50% |

$3 38% |

| C. 0.5 0-profit Loss % |

n/a | n/a | n/a | $65 >50% |

$75 >50% |

$31 49% |

$3 38% |

$12 43% |

−$32 25% |

| Operating costs, Cop ($/col) Initial value: $280 | |||||||||

| B. $210 0-profit Loss % |

$142 >50% |

$152 >50% |

$136 83% |

$205 >50% |

$215 >50% |

$171 100% |

$143 >50% |

$152 >50% |

$108 79% |

| C. $350 0-profit Loss % |

$2 38% |

$12 42% |

−$4 36% |

$65 >50% |

$75 >50% |

$31 49% |

$3 38% |

$12 43% |

−$32 25% |

| Canola rental fees, PRc ($/col) Initial value: $245 | |||||||||

| B. $184 0-profit Loss % |

n/a | n/a | n/a | $103 >50% |

$114 >50% |

$70 64% |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| C. $306 0-profit Loss % |

n/a | n/a | n/a | $166 >50% |

$175 >50% |

$131 87% |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Blueberry rental fees, PRb ($/col) Initial value: $120 | |||||||||

| B. $90 0-profit Loss % |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | $58 >50% |

$67 >50% |

$23 46% |

| C. $150 0-profit Loss % |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | $88 >50% |

$97 >50% |

$53 57% |

| Queen price, pq ($/queen) Initial value: $45 | |||||||||

| B. $56.25 0-profit Loss % |

$68 >50% |

n/a | n/a | $131 >50% |

n/a | n/a | $68 >50% |

n/a | n/a |

| C. $67.50 0-profit Loss % |

$64 >50% |

n/a | n/a | $127 >50% |

n/a | n/a | $64 >50% |

n/a | n/a |

| Imported package price, Cpk ($/package) Initial value: $240 | |||||||||

| B. $300 0-profit Loss % |

n/a | n/a | $44 49% |

n/a | n/a | $78 61% |

n/a | n/a | $16 42% |

| C. $360 0-profit Loss % |

n/a | n/a | $22 42% |

n/a | n/a | $56 52% |

n/a | n/a | −$6 35% |

For the sensitivity analysis, a winter colony mortality rate of 37% (5-yr average) is used in all scenarios.

Negative per colony profit is highlighted in gray.

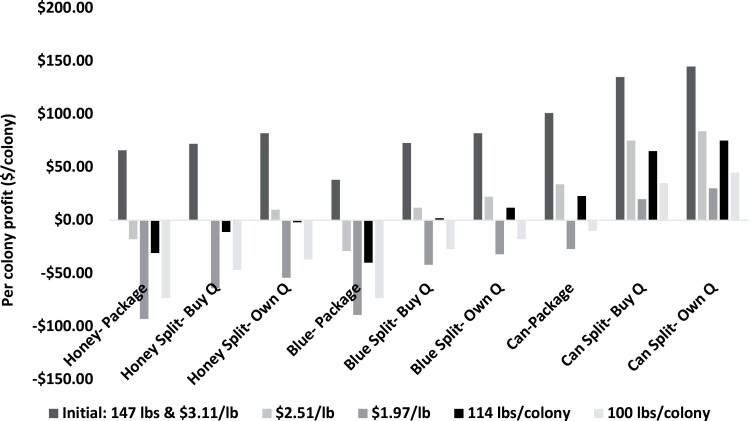

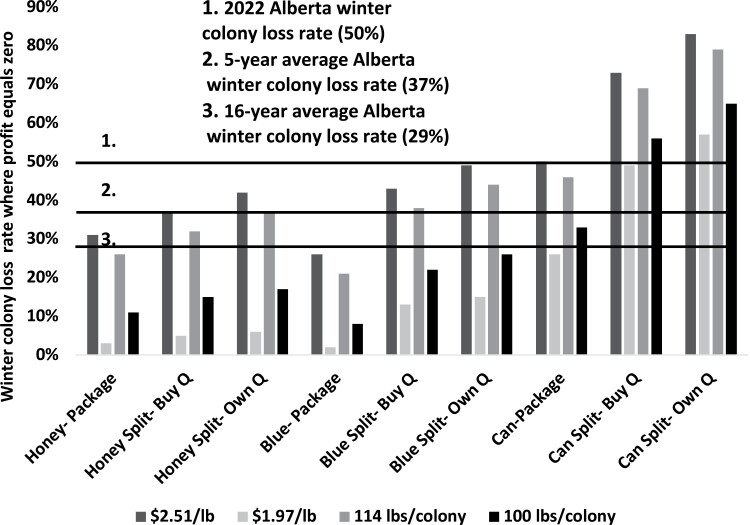

When honey yields decrease, profitability impacts follow a similar pattern to those with higher honey prices. At 114 lbs of honey per colony, honey producers who do not engage in commercial pollination accrue negative profits for all replacement strategies, with the colony unable to accrue positive profits at colony winter loss levels of between 26% and 37%. Beekeepers who sell honey and engage in commercial blueberry pollination also accrue negative profits at 114 lbs of honey per colony when packaged bees are used for replacement. Using splits to replace lost colonies yields profits between $2 and $12 a colony for operations who produce 114 lbs of honey per dedicated honey producing colony and rent bees for blueberry pollination. At this lower honey yield, for beekeeping operations renting bees for canola pollination, replacing with package bees results in lower profits of $23/colony with the colony accruing negative profits at a winter loss rate of greater than 46%, lower than the average Alberta colony mortality rate in 2022. With an even lower honey yield of 100 lbs/colony, only beekeeping operations renting colonies for commercial canola pollination and replacing losses with splits accrue non-negative profits of between $35 and $45/colony, with negative profit when these operations replace losses with packages. Dedicated honey producers who do not rent colonies for pollination as well as those who rent colonies for blueberry pollination accrue negative profits between −$73 and −$18 per colony when honey yields are 100 lbs per colony, with non-positive profit accrued with winter losses between 26% and 8%, losses that are well below recent Alberta winter colony mortality rates. Figure 1 shows the colony profit for this range of honey prices and honey yields at a 37% colony winter loss rate by beekeeping activity and replacement strategy. For each management scenario (beekeeping activity and replacement strategy), Fig. 2 shows the estimated winter colony mortality rate that would accrue zero profits to the beekeeping operation. 1, 2, and 3 show the average Alberta winter loss rates for 2022 (1), 2018–2022 (2), and 2007–2022 (3).

Fig. 1.

Per colony profit by beekeeping activity, replacement strategy, honey price, and honey yield at a 37% colony winter loss rate.

Fig. 2.

Winter colony loss rates that generate zero-profit for operations with variability in honey prices and yields for different beekeeping activities and colony replacement strategies.

When pollination costs are increased by 25% and 50%, beekeepers engaging in blueberry pollination and replacing losses with packages accrue per colony profits of between $3 and −$32 with zero-profit accrued at winter loss rates of 38% and 25%, respectively, again both below the 2022 Alberta colony winter loss rate. Lower operating costs result in higher per colony profit while higher operation costs result in decreased profits for all beekeeping activities and replacement strategies. At a per colony operating cost of $350, operations that produce honey with no pollination contracts and those that produce honey and rent colonies for blueberry pollination see lower per colony profits from −$32 to $12 depending on replacement strategy and activity, with zero-profit for their colony when winter loss rates are between 25% and 43%. As expected, when the rental fees for blueberry pollination and canola pollination increase, per colony profit increases, and conversely, with lower rental rates, profits fall. With the cost of a purchased queen increasing, profits remain positive and mortality thresholds remain above 50%. With higher package bee costs, operations producing honey and renting bees for canola pollination see profits fall and zero-profit winter loss rates ranging from 52% to 61%, again depending on the increase in package cost and beekeeping activity. However, as prices of package bees increase, profits for honey production alone and honey with blueberry pollination contracts fall to between −$6 and $44 per colony with the colony unable to make positive profits at winter loss rates of between 35% and 49%, depending on the increase in package cost and beekeeping activity.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the profitability of commercial beekeeping operations in Alberta, Canada is dependent on operational management decisions including the source of replacement bees and the diversification of the operation, as well as external factors, such as the environment as well as market demand and supply that reinforces the economic impact of these decisions. Beekeeping operations for which revenue is less affected by price fluctuations in international markets and for which the costs associated with imported bee health are minimized, more consistently achieve profitability. The more operations were self-sufficient in producing stock (queens and splits), the greater their profitability. Specifically, for operations that replaced losses with imported packages, there was a larger decrease in per colony profit with increased winter colony mortality than for operations replacing losses with splits. For operations that purchase rather than produce queens, profit decreased more as winter colony loss increased compared to the operations who produced queens with their splits. Diversity of income streams also affected profitability, with operations that engage in pollination, especially canola pollination, having higher profit. For beekeeping operations that engaged in commercial canola pollination as well as honey production, per colony profit was higher for all replacement strategies compared to both honey production alone and honey production with blueberry pollination. For beekeeping operations that engage in honey production with blueberry pollination, per colony profit is higher than for those beekeeping operations choosing not to rent out colonies for pollination when the operation replaces losses with splits. However, when losses are replaced with packages, honey production without commercial pollination contracts yields higher per colony profit than honey production with blueberry pollination. As the parameter values were adjusted in the sensitivity analysis, the effects of replacement strategy and diversification of beekeeping activity (i.e., pollination) on profit remained. As revenues decreased from lower honey prices and yields, so too did per colony profit. The opportunity to accrue additional income from pollination rental contracts, particularly lucrative contracts such as canola, provides a beekeeping operation with stable income to supplement the less predictable profits provided by honey production; yield and price are largely exogenous variables beyond the control of the beekeeper. As the costs for imported packages increased, profits fell for operations dependent on imported stock. As queen prices increased however, due to the relatively small cost of a queen compared to a package, profit remained positive with operations able to sustain winter losses of >50%. This result suggests that even if an operation does not produce queen bees, by making splits and purchasing a more expensive queen (domestic or imported), the operation is more profitable than for operations dependent on imported packages when package prices increase. An operation that is even partly self-reliant for their bee supply therefore has a similar directional effect as the income insurance afforded by diversifying an operation into pollination. Although there is no explicit difference in the price of a domestic or imported queen purchased by the representative beekeeper in our model, because of increasing risks associated with imported bee stock, the full impact of poor imported queen health on a beekeeper’s operation would likely be higher than what our model predicts. As a result, a beekeeping operation importing queens would likely have greater reductions in profit than those purchasing less risky domestic queens. Further research into the effect of capturing the full cost of poor imported queen health on profitability should be explored.

Our results indicate that there is no one fixed profitable level of colony winter loss in commercial Canadian beekeeping. Beekeeping operations’ profitability is a function of many endogenous and exogenous variables. Colony replacement strategy, revenue sources of a beekeeping operation, environmental and market variability as well as colony winter loss rates are some of the important variables that play a role in colony profit. It is important that apiculturists and beekeepers recognize the multi-faceted nature of a colony’s profitability and how colony winter loss rates play a role in a beekeeping operation’s economic viability, as do many other factors. Commercial beekeepers in Alberta have historically experienced variable winter loss rates and this variability in colony losses from year to year creates uncertainty for the beekeeper in terms of operational planning and investing in the industry both in the short and long term. In some years, a low winter mortality rate may result in positive profits, particularly for beekeepers who pollinate crops, make splits and produce in-house queens to replace their losses. In these profitable years, a beekeeper could invest in new vehicles, extractors, and other equipment, modernizing and scaling up their operation, and/or focusing on increasing domestic breeding of queens and bees. However, with high average losses over the past 5 yr, negative or zero profits would preclude any investment in the present or future of the operation. Highly unpredictable variables such as honey prices, fuel, and labor costs, prices of packages and queens and honey output year to year, are susceptible to external factors, further contributing to yearly fluctuations in profitability. Our modeling results show that when faced with uncertainty in revenue and costs, a beekeeping operation can be more profitable through being less susceptible to external fluctuations by (i) diversifying beekeeping activities into avenues such as commercial pollination (other diversifications avenues may include bee sales and bee products) and (ii) increasing self-reliance on bee sources by minimizing imported stock. Understanding how beekeeping decisions affect colony profit will enable Canadian beekeepers and policy makers to strive for both profitability and growth. Beekeepers can leverage this research to make informed management decisions such as engaging in lucrative commercial pollination contracts, participating in educational programs that teach and encourage queen rearing and split making, and advocating for policy changes that support long-term growth. These actions will ultimately support a future of healthy bees, profitable beekeeping operations, and enhanced domestic food security.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Government of Canada through Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (GRDI, J-002368), Genome Canada and the Ontario Genomics Institute (OGI-185) and the following funding partners: Genome British Columbia, Genome Québec, and the Ontario Ministry of Colleges and Universities, awarded to MB and SEH, and through the support of Results Driven Agriculture grants awarded to SEH and the University of Lethbridge.

Contributor Information

Miriam Bixby, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of British Columbia, 2125 East Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada.

Rod Scarlett, Canadian Honey Council, #218, 51519 RR 220, Sherwood Park, AB T8E 1H1, Canada.

Shelley E Hoover, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Lethbridge, 4401 University Dr W, Lethbridge, AB T1K 3M4, Canada.

Authors Contributions

Miriam Bixby (Conceptualization-Lead, Data curation-Lead, Formal analysis-Lead, Investigation-Lead, Methodology-Lead, Writing – original draft-Lead, Writing – review & editing-Lead), Rod Scarlett (Conceptualization-Supporting), Shelley Hoover (Conceptualization-Lead, Methodology-Supporting, Writing – original draft-Supporting, Writing – review & editing-Supporting)

References Cited

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). Statistical overview of the Canadian and honey bee industry 2021; 2020. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/sector/horticulture/reports/statistical-overview-canadian-honey-and-bee-industry-2021.

- AWLR. 2018 Apiculture Winter Loss Report. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Government of Ontario; 2018. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://www.ontario.ca/document/annual-apiculture-winter-loss-reports/2018-apiculture-winter-loss-report. [Google Scholar]

- Bee CSI Data. Contact corresponding author for more information; 2020.

- BIP. Bee Informed Partnership Team. United States honey bee colony losses 2021-2022: preliminary results;2022. [accessed 2022 Aug 15]. https://beeinformed.org/2022/07/27/united-states-honey-bee-colony-losses-2021-2022-preliminary-results-from-the-bee-informed-partnership/.

- Bixby M, Guarna MM, Hoover SE, Pernal SF.. Canadian Honey Bee Queen Breeders’ Reference Guide. Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists. p. 55; 2019. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. http://honeycouncil.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/FinalQueenBreederReferenceGuide2018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bixby M, Hoover SE, McCallum R, Ibrahim A, Ovinge L, Olmstead S, Pernal SF, Zayed A, Foster LJ, Guarna MM.. Honey bee queen production: Canadian costing case study and profitability analysis. J Econ Entomol. 2020:113(4):1618–1627. [accessed 2022 Jul 13] 10.1093/jee/toaa102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Robertson T.. Report on the 2018 New Zealand Colony Loss Survey Draft Report, MPI Technical Paper No: 2019/02. Prepared for the Ministry for Primary Industries: Manaaki Whenua, Landcare Research and Coco Analytics; 2019. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/33663-2018-bee-colony-loss-survey-report. [Google Scholar]

- Canada Beekeeping Supply (CBS). A HIVERITE Company; 2023. 2022 [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://canadabeekeepingsupply.com/collections/bees.

- Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists (CAPA). Annual Colony Loss Reports: CAPA Statement on Honey Bee Losses in Canada: (2007–2022); 2022. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://capabees.com/shared/CAPA-preliminary-report-on-winter-losses-2021-2022_FV.pdf.

- Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists (CAPA). AGM Proceedings. In Proceedings 2010/2011, Markham, Ontario; 2010. http://www.capabees.com/shared/2017/09/2010_11-CAPA-Proceedings-Markham-ON.pdf.

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Risk assessment on the importation of honey bee (Apis mellifera) packages from the United States of America. Animal Health Risk Assessment, Animal Health Division; 2013. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://www.ontariobee.com/sites/ontariobee.com/files/Final%20V13%20Honeybeepackages%20from%20USA_Oct21_2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Risk assessment on the importation of honey bee (Apis mellifera) packages from the United States of America (V13), September 2013; 2013. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://www.ontariobee.com/sites/ontariobee.com/files/Final%20V13%20Honeybeepackages%20from%20USA_Oct21_2013.pdf.

- Currie RW, Pernal SF, Guzmnn-Novoa E.. Honey bee colony losses in Canada. J Apic Res. 2010:49:104–106. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.18. [Google Scholar]

- Dancing Bee Equipment (DBE); 2023. 2022 [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://dancingbeeequipment.com/collections/queen-bees.

- Emunu JP. Alberta 2020 Beekeepers’ Survey Results. Statistics and Data Development Section Alberta Agriculture and Forestry; 2020. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/a854e8c2-37cf-4c3e-a99f-3bc8e477ca8d/resource/17975c43-c079-48ee-ac80-d464e066d932/download/af-irtb-alberta-2020-beekeepers-survey-results.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- vanEngelsdorp D, Tarpy DR, Lengerich EJ, Pettis JS.. Idiopathic brood disease syndrome and queen events as precursors of colony mortality in migratory beekeeping operations in the eastern United States. Prev Vet Med. 2013:108(2-3):225–233. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar CL. The influence of colony population on honey production. J Agric Res. 1937:54(12):945–954. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar CL. Ecological studies on overwintered honey bee colonies. J Econ Entomol. 1952:45(33):445–449. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://academic.oup.com/jee/article/45/3/445/830110. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier PM, Rucker RR, Thurman WN, Burgett M.. Economic effects and responses to changes in honey bee health ERR-246. United States Department of Agriculture: A report summary from the Economic Research Service; 2018. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/88117/err-246.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Furgala B, McCutcheon DM.. Wintering productive colonies. In: Graham JM, editor. The hive and the honey bee. revised ed. Hamilton (IL): Dadant and Sons; 1992. p. 829–868. [Google Scholar]

- Furgula. Fall Management and the wintering of productive colonies. In: Graham JM, editor. The hive and the honey bee. revised ed. Hamilton (IL): Dadant and Sons; 1992. p. 471–490. [Google Scholar]

- Gabka J. Correlations between the strength, amount of brood, and honey production of the honey bee colony. Med Weter. 2014:70(12):754–756. [Google Scholar]

- Genersch E, von der Ohe W., Kaatz H, Schroeder A, Otten C, Büchler R, Berg S, Ritter W, Mühlen W, Gisder S.. The German bee monitoring project: a long term study to understand periodically high winter losses of honey bee colonies. Apidologie. 2010:41:332–352. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Novoa E, Eccles L, Calvete Y, Mcgowan J, Kelly PG, Correa-Benítez A.. Varroa destructor is the main culprit for the death and reduced populations of overwintered honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies in Ontario, Canada. Apidologie. 2010:41:443–450. 10.1051/apido/2009076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiheung A, Xianbing X, Riddle J, Pettis J, Huang ZY.. Effects of long-distance transportation on honey bee physiology. Psyche J Entomol. 2012:2012, Article ID 193029, 9 pages. 10.1155/2012/193029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laate EA. Economics of Beekeeping in Alberta 2016. 2017. Agdex 921-62. AgriProfit Economics Section, Economics and Competitiveness Branch, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry; 2017. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$Department/deptdocs.nsf/all/econ16542/$FILE/Beekeeping2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Laate EA, Emunu JP, Duering A, Ovinge L.. Potential economic impact of European and American Foulbrood on Alberta’s Beekeeping Industry. Economics and Competitiveness Branch and Plant and Bee Health Surveillance Section. Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, Agriculture and Forestry, Government of Alberta; 2020. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/029a345b-8621-4986-ad78-7fc6ddcd8b17/resource/25f7b78d-a359-428c-9648-9175c3634720/download/af-potential-economic-impact-european-american-foulbrood-on-albertas-beekeeping-industry.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Le Conte Y, Ellis M, Ritter W.. Varroa mites and honey bee health: can Varroa explain part of the colony losses? Apidologie. 2010:41(3):353–363. 10.1051/apido/2010017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Sun M, Liu Y, Liu B, Bianchi FJJA, van der Werf W, Lu Y.. High pollination deficit and strong dependence on honeybees in Pollination of Korla Fragrant Pear, Pyrus sinkiangensis. Plants (Basel). 2022:11(13):1734. 10.3390/plants11131734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Chen C, Niu Q, Qi W, Yuan C, Su S, Liu S, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Ji T.. Survey results of honey bee (Apis mellifera) colony losses in China (2010–2013). J Apic Res. 2016:55: 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Maucourt S, Fournier V, Giovenazzo P.. Comparison of three methods to multiply honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies. Apidologie. 2018:49:314–324. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. 10.1007/s13592-017-0556-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAfee A, Chapman A, Higo H, Underwood R, Milone J, Foster L, Guarna MM, Tarpy DR, Pettis JS.. Vulnerability of honey bee queens to heat-induced loss of fertility. Nat Sustain. 2020:3:367–376. [accessed 2023 Feb 136]. 10.1038/s41893-020-0493-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DL, Jay SC.. Producing honey in the Canadian prairies using package bees. Bee World. 1982:63:110–117. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0005772X.1982.11097874. [Google Scholar]

- NJC. CFS Report Fuel Price Update- May 2016. National Joint Council; 2016. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://www.njc-cnm.gc.ca/s3/d649/en#:~:text=Average%20gasoline%20prices%20per%20litre,April%201st%2C%202016. [Google Scholar]

- Pernal SF, Albright RL, Melathopoulos AP.. Evaluation of the shaking technique for the economic management of American foulbrood disease of honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J Econ Entomol. 2008:101(44):1095–1104. 10.1603/0022-0493(2008)101[1095:eotstf]2.0.co;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettis JS, Rice N, Joselow K, vanEngelsdorp D, Chaimanee V.. Colony failure linked to low sperm viability in honey bee (Apis mellifera) queens and an exploration of potential causative factors. PLoS One. 2016:11(22):e0147220. [accessed 2023 Feb 16] https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0147220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revival Queens (RQ). 2023. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://revivalqueenbees.com/shop/.

- Sagili RR, Burgett DM.. Evaluating honey bee colonies for pollination: a guide for commercial growers and beekeepers. A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication Oregon State University, University of Idaho, Washington State University, PNW62; 2011. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/sites/catalog/files/project/pdf/pnw623.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Spleen AM, Lengerich EJ, Rennich K, Caron D, Rose R, Pettis JS, Henson M, Wilkes JT, Wilson M, Stitzinger J, et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2011–2012 winter colony losses in the United States: results from the Bee Informed Partnership. J Apic Res. 2013:52:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada (Stats Can). Production and Value of Honey; 2021. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. 10.25318/3210035301-eng. [DOI]

- Statistics Canada (Stats Can). Monthly average retail prices for gasoline and fuel oil, by geography; 2022. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000101&pickMembers%5B0%5D=2.2&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=06&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2016&cubeTimeFrame.endMonth=06&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20160601%2C20220601.

- Szabo TI, Lefkovitch LP.. Effect of brood production and population size on honey production of honeybee colonies in Alberta, Canada. Apidologie. 1988:20:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Bee Supply 2022; 2020. [accessed 2023 Feb 16]. https://urbanbeesupplies.ca/products/tasmanian-packaged-bees-2022?variant=39626742169700.

- West Coast Bee Supply (WCBS); 2022. [accessed 2023 Feb 136]. https://westcoastbeesupply.ca.