Abstract

Background

Abdominal high-definition liposuction has been practiced for many years. However, problems such as low-lying, “sad-looking” umbilici and lower abdominal “pooches” remain unresolved. Additionally, the waistline, as the pivotal point connecting the chest and hips, deserves more attention and improvement.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to use polydioxanone (PDO) threads after liposuction: (1) to improve the shape and position of the umbilicus permanently; (2) to tighten the lower abdomen permanently; and (3) to redefine “high-definition” liposuction.

Methods

All patients underwent high-definition liposuction of the abdomen and waist. After liposuction, bidirectional, barbed PDO threads were placed in the upper central abdomen. The threads were pulled to cinch the upper abdominal skin and then tied. The resulting umbilicus elevation was measured for up to 12 months. Higher waistlines were also created to match higher-positioned umbilici.

Results

Fifty-two female subjects were included. The range of umbilicus elevation at 12 months was 0.8 to 3.6 cm. Most umbilici were converted to vertical orientation, and lower abdomens became lengthened, flattened, and tightened. Moreover, the enhanced waistlines and body curves created better body proportions.

Conclusions

This technique results in permanent elevation and shape enhancement of both umbilicus and lower abdomen. In addition, because the umbilicus is raised, a higher waistline can be created without any discordance, making the lower limbs appear longer. Overall, the maneuvers contributed to the restoration/rejuvenation of the abdomen and created a better overall body shape and proportion.

Level of Evidence: 4

See the Commentary on this article here.

High-definition liposuction of the abdomen has been practiced for many years with impressive results.1 However, umbilical shape and position, and lower abdominal “pooches”, cannot be easily corrected.1,2 In addition, the waistline, as the key point connecting the rib cage and hips, has been rarely mentioned in the literature, especially regarding its relationship to the umbilicus. Nonetheless, the importance of umbilicus position and its interplay with the waistline cannot be ignored when judging an abdomen for its attractiveness (Supplemental Figures 1, 2, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com).

The umbilicus, waistline, corset lines, and other key landmarks contribute to the beauty of a female body. A cosmetically attractive umbilicus is small, vertically oriented, and linear or oval in shape (Figure 1).2,3 Unfortunately, umbilicus shape changes because of aging, sunbathing, weight gain/loss, and pregnancy, often presenting as a “sad looking”, reversed “V”-shape (Figure 1F). Although the ideal position of the umbilicus has been debated for decades,3-6 it is safe to suggest that most aesthetic practitioners prefer umbilici at a level near the iliac crests (ICs).2-4

Figure 1.

Different shapes of umbilicus found in the general population. The vertically oriented oval shape is the most preferred (A, B), followed by C. D is typically the result of overweight. E and F usually exist in patients with aging or other conditions. G is an “outie,” which may contain a small hernia. H is an iatrogenic deformity that can present in different forms.

Humans experience undesirable downward migration of the umbilicus with age, accompanied by shortening of the lower abdomen and “pooch” formation. These changes can be further worsened after liposuction. Liposuction debulks the subcutaneous tissue and can cause descent of the loose abdominal skin and the umbilicus.4 Without a well-positioned umbilicus, the abdominal appearance becomes suboptimal, even with high-definition liposuction. In Figure 2, the lower abdominal “pooch” was barely improved, and a malformed and descended umbilicus (1.2 cm lower than before surgery) is also observed. Similarly, in Figure 3, although the abdomen was improved after high-definition liposuction, the lower abdominal “pooch” remained, and the “sad-looking” umbilicus looked the same and descended slightly (0.5 cm). Interestingly, the subject’s studio photograph (Figure 3C) did display a perfect, sculpted abdomen—demonstrating why we should always use medical, rather than studio, photographs for scientific purposes.

Figure 2.

This 36-year-old female, 162 cm, 59 kg, gravida 1, para 1, underwent high-definition liposuction of the abdomen and waist. A total of 800 mL of fat was removed. The 1-year postoperative photograph shows good improvement, except for the umbilicus and the lower abdominal “pooch.” Descent of the umbilicus was observed: the upper edge of the umbilicus sits below the iliac crests by 1.8 cm before (A) and 3 cm after (B) the liposuction.

Figure 3.

This 45-year-old female, 175 cm, 66 kg, gravida 2, para 2, underwent high-definition liposuction of the abdomen and waist. A total of 600 mL of fat was harvested. Subsequently, 250 mL of fat was grafted into each breast. The upper edge of the umbilicus sits below the iliac crests: 1.5 cm below before liposuction (A) and 2 cm below 1 year after liposuction (B). The lower abdominal “pooch” was only slightly improved. The patient’s studio photograph with special lighting is shown, demonstrating an artificially enhanced result (C).

In more than 200 high-definition abdominal liposuction procedures this author performed without any energy device since 2008, the same problems were encountered in almost every patient, namely, the descent of the umbilici by 0.2 to 1.5 cm. This phenomenon could be attributed to the loss of subcutaneous tissue support, causing the loose skin to slide down.

To overcome the loose skin problem, energy-based modalities have been advocated for many years. Promoters of ultrasound technology believe that ultrasound energy causes significant skin shrinkage,6 whereas others argue otherwise.7 Unfortunately, complications from ultrasound treatment can be quite high.6 Similar observations were made by other studies.8-10 I have used laser lipolysis combined with high-definition liposuction to treat loose abdominal skin. Although relatively good skin tightening can be achieved, many patients ended up having skin unevenness over time (probably due to uncontrollable tissue fibrosis and late-onset fat cell apoptosis). Furthermore, many patients’ umbilici became strange looking because of the scarring process (Figure 1H).

Non–energy-based technologies have also been used to treat the abdominal wall. One such is the use of polydioxanone (PDO) threads.11 Interestingly, PDO thread treatments are mostly provided by noncore physicians (Google search), who claim that barbed threads can “lift” the umbilicus and the periumbilical skin. However, no solid report on the long-term efficacy has ever been provided in a peer-reviewed journal.

The goal of aesthetic liposuction is to attain real “high-definition” results and restore the patients’ body shapes to their youthful forms. However, a major limiting factor for achieving such a goal are the low-lying, “sad-looking” umbilici in most patients.1,12 This study reports an innovative technique for permanent umbilicus elevation and lower abdomen improvement during high-definition liposuction. The concept of creating higher waistlines to further enhance body proportions is also described.

Methods

This study strictly followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. IRB approval was not required due to the retrospective nature of this study. Instead, an ethics committee approval (Ethics Committee, Rejuvenexx, Inc., Arcadia, CA) was obtained. The patients were educated about the nature of the surgery, and written informed consents were acquired. A total of 52 Asian female patients undergoing high-definition liposuction of the abdomen and waist between August 2018 and October 2020 were enrolled (another 23 patients were excluded for lack of follow-up). The inclusion criteria included patients who desired liposuction to improve their figures, without any contraindications such as chronic or acute diseases. Patients with a BMI >32 kg/m2 and with diabetes or other clinical issues such as cardiac problems, depression, or unstable weight were excluded. Patients with significant weight loss or who were obvious abdominoplasty candidates were also excluded. Age was not a limiting factor because no patients over the age of 60 years ever requested a liposuction procedure in my practice. The patients’ ages ranged from 25 to 53 years (mean, 36.9 years). Their BMIs ranged from 18.4 to 31.6 kg/m2 (mean, 23.6 kg/m2). Nine were nulliparous. Two patients had round-shaped umbilici, 3 had vertical-shaped umbilici, and all others had reversed “V”-shaped umbilici.

With the patients in a standing position, the distance from the xiphoid process to the upper edge of the umbilicus (XU) and the distance from the upper edge of the umbilicus to the pubis symphysis (UP) were measured. The distance of the upper edge of the umbilicus to the ICs (UIC) was also recorded.

The surgeries were carried out in an ambulatory surgery center with modest intravenous sedation. The super-wet technique was used for tumescent fluid (for each liter of normal saline, 20 mL of 2% lidocaine, 1 mL of 1:1000 epinephrine, 2 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate, and 50 mg clindamycin were added) infiltration. High-definition liposuction was performed1,8 with a MicroAire (Chicago, IL) power-assisted liposuction device, equipped with a 3-mm Mercedes cannula for ease of advancement and to reduce trauma to the tissues.

Liposuction was started by superficial fat removal from 5 ports (2 groin ports, 2 inframammary ports, and 1 umbilicus port at its upper pole). This was followed by deep fat removal below the Scarpa’s fascia. Etching (with the ports of the Mercedes cannula facing upward) was done to create corset lines and a midline trough above the umbilicus. For the creation of “six-packs,” only modest etching was performed at the tendinous intersections of the rectus abdominus area (Video 1, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com).

The waistline was created higher than before (1 cm above the ribcage/costal margins at the sides, with the range of height increase from 1 to 3 cm). The waistline follows a 10° to 15° (upward) angle as it flows from the lateral aspect of the linea semilunaris (usually at the level of the second tendinous intersection of the rectus abdominus) to the back (ending at a point that coincides with the intersection between the latissimus dorsi and the bulk of external and internal oblique muscles). Care was taken to preserve enough fat below the newly created waistline so that a smooth and attractive curve forms from the waist to the hips. When trochanteric depressions were encountered that prevented the easy flow of this curve, fat grafting was utilized to correct the depression defect. When breast tails were present, liposuction was extended to remove the fat and to contour the lateral breasts. This way, a pair of streamlined, appealing curves could be created, extending from the upper chest to the thighs in most patients. A pinch test was then performed to determine skin evenness and the end point of the procedure. Any unevenness was corrected by grafting fat back. The volume of fat removed ranged from 250 to 2000 mL.

After liposuction, a double open-ended 16G cannula was inserted through an entry point in the midline of the upper abdomen. The entry point was made with a 16G needle at about 16 cm from the umbilicus. The cannula traveled 1.5 to 2 mm under the dermis at about 5 mm away from the midline on one side and exited the umbilicus port, followed by passing 1 arm of a 43-cm-long, U-shaped, bidirectional, 1-0 barbed MINT43 PDO thread (MINT, Santa Fe Springs, CA). The other arm was passed through a different path, 5 mm away from the midline on the other side using the same entry point (Figure 4A and Video 2, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com). The same maneuver was repeated with another thread, via more laterally placed paths (1 cm lateral to the midline; Figure 4B and Video 2). Afterwards, the thread ends were pulled to capture the subcutaneous tissue. After the cinching effect was maximized, the paired thread ends were tied. The knots retract and become buried inside the umbilical port (Figure 4C and Video 2). The umbilicus port was then closed with a 5-0 plain gut suture.

Figure 4.

(A) Insertion of the first barbed PDO thread. The entry point is about 16 cm from the umbilicus, and the exit point is immediately behind the hooding of the upper umbilicus. (B) Insertion of the second barbed PDO thread. The first PDO thread is already in place. (C) The paired thread ends are tied, and the knots retract into the exit point at the umbilicus. PDO, polydioxanone.

The immediate XU distance was shortened by 2 to 8 cm, with most umbilici changed to tight vertical “slit” forms. Significant upper abdominal skin bunching took place immediately. Also noticeable was the elongation and flattening of the lower abdomen, as it became stretched up (Figures 5, 6).

Figure 5.

This 31-year-old female patient, 174 cm, 62 kg, BMI 20.5 kg/m2, gravida 2, para 2, underwent high-definition liposuction of the abdomen and waist. A total of 750 mL of fat was removed; 300 mL of fat was grafted to each breast. PDO-thread-assisted umbilicus elevation was performed at the same time. The shape of the umbilicus changed from horizontal to vertical. The XU/UP was 21.2/13.9 cm before surgery, 14.7/20.4 cm at 3 weeks postsurgery, and 16.5/15 cm at 12 months postsurgery. The UIC was 2 cm below the ICs before surgery, 4.5 cm above the ICs at 3 weeks postsurgery, and 1.6 cm above the ICs at 12 months postsurgery. Umbilicus elevation was 8 cm on the operating room table, 6.5 cm at 3 weeks postsurgery, and 3.6 cm at 12 months postsurgery. The lower abdomen was elongated and flattened. The abdomen was successfully restored to a more youthful form. (A, E) Before surgery, (B, F) at 3 weeks postsurgery, (C, G) at 3 months postsurgery, and (D, H) at 12 months postsurgery. The divot/extra crease-like change above the umbilicus was a result of scarring from her previous piercing, which disappeared over time. IC, iliac crest; UIC, distance from the upper edge of the umbilicus to the ICs; UP, distance from the upper edge of the umbilicus to the pubis symphysis; XU, distance from the xiphoid process to the upper edge of the umbilicus.

Figure 6.

This 47-year-old female patient, 168 cm, 74 kg, BMI 26.2 kg/m2, gravida 1, para 1, with a history of C-section, and unsuccessful liposuction of the abdomen (with significant skin unevenness and depressed scars at the adits), underwent high-definition liposuction of the abdomen, waist, accessory breasts, breast tails, and mons pubis. A total of 1950 mL of fat was removed. She had breast and buttock fat grafting. Areolar lift and umbilicus elevation with PDO threads were also done. The XU/UP was 17.2/14.3 cm before the surgery, 13.0/18.5 cm at 3 weeks postsurgery, and 14.0/17.5 at 12 months postsurgery. The upper edge of the umbilicus was 1.2 cm below the ICs before the surgery, 3.0 cm above the ICs at 3 weeks postsurgery, and 1.9 cm above the ICs at 12 months postsurgery. The elevation of the umbilicus was 4.2 cm at 3 weeks postsurgery and 3.1 cm at 12 months postsurgery. The abdomen was successfully restored to a more youthful form. The dimple-like change above the umbilicus was a result of her previous piercing. The depressed adit scars were treated with subcision and fat grafting at 6 months. (A, E) Before surgery, (B, F) at 3 weeks postsurgery, (C, G) at 3 months postsurgery, and (D, H) at 12 months postsurgery. IC, iliac crest; UIC, distance from the upper edge of the umbilicus to the ICs; UP, distance from the upper edge of the umbilicus to the pubis symphysis; XU, distance from the xiphoid process to the upper edge of the umbilicus.

After cleansing, the wounds were cared for with a Xeroform dressing. Combined pads were used, and the abdomen wrapped with an abdominal binder, applying very gentle pressure, to prevent impediment of blood circulation. The patients were seen for 2 consecutive days postsurgery. At these 2 days of follow-up, if any skin divot is found, the harvested fat (kept in a refrigerator) could be grafted back without any anesthesia. Starting from postoperative day 1, a 1.5-inch-thick eggshell foam pad was used to compress the abdominal skin under a garment with modest pressure. The garment was kept on for 24 hours a day, except when showering. All patients were started on a fast-walking exercise regimen. Because the skin in the treated areas became dry easily, an ample amount of oil-based body lotion was applied twice a day. After 3 weeks, a 0.5-inch foam pad was used for better comfort, and the garment was required to be worn for 16 hours a day from this point on. At 3 months, patients were changed to home-wear compression garments. The patients were followed up at 3-week, 3-month, and 12-month points. XU, UP, and UIC were measured at 3 weeks and 12 months, and the elevation of the umbilicus was determined by the change in XU distance. For statistical analysis, t-tests with Microsoft Excel were performed.

Results

At 3 weeks, some “cheese-wiring” effect was expected, reflected by some descent of the substantially lifted umbilici. Nonetheless, the “cheese-wiring” effect was limited because the skin cinching remained significant and the umbilical positions stayed high (Figures 5, 6). In the next 3 to 6 months, the skin gradually smoothened without residual skin irregularity. Whereas the mean XU/UP ratio was 1.29 before surgery, it became 0.8 at 3 weeks, and stabilized at 0.98 after 12 months. The mean UIC was –2.3 cm (below the ICs) before surgery, 1.4 cm (above the ICs), at 3 weeks post surgery, and –0.1 cm at 12 months postsurgery. The mean umbilicus elevation was 3.7 cm at 3 weeks and 2.3 cm at 12 months. All the changes were statistically significant (P < 0.001). Regarding umbilical shapes, 49 turned vertical or more vertical, and only 3 stayed reversed “V”-shaped, but with appreciable improvement.

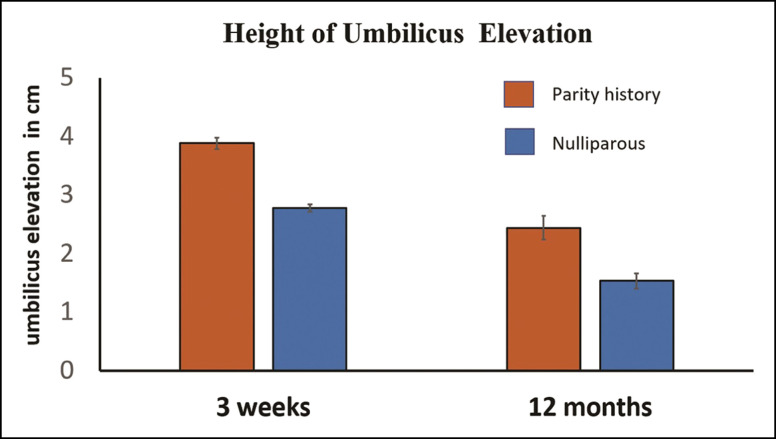

Interestingly, although the extent of umbilicus elevation varied widely (from 0.8 to 3.6 cm at 12 months), the variation was unrelated to the weight, height, or BMI of the patients (P > 0.05). Rather, the only significant difference (P < 0.001) was found between the parity group and the nulliparous group (Figure 7). Results from patients with different body habitus are shown in Figures 5 and 6. In both groups of patients, divots were observed just above the original umbilici. These divots were a result of previous naval piercing scars, and disappeared by 12 months (Figure 5) or became significantly smaller (Figure 6). This deformity was not encountered in any patients who never had naval piercings.

Figure 7.

Significant difference exists between the parity groups and the nulliparous group when umbilicus elevation levels are compared. Standard errors are represented by vertical bars on the columns. At 3 weeks postsurgery, the mean umbilicus elevation was 3.886 cm for the parity group, and 2.778 for the nulliparous group. At 12 months postsurgery, the numbers were 2.444 and 1.533 cm, respectively (P < 0.001).

A survey of patient satisfaction was performed by administering a questionnaire at 3-week, 3-month, and 12-month follow-ups, with ratings stratified as “bad,” “fair,” “good,” or “perfect” (Appendix, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com). The paper questionnaire was administered in my office when the patients came back for visits. The survey was done anonymously (without signature), and was administered by my patient care coordinators. At 3 weeks, 1 patient expressed dissatisfaction because of upper abdominal bunching and edema on 1 side of the lower abdomen. However, at 3 months, she was happy with the result. Only 1 patient, with the highest BMI (31.6 kg/m2), rated her result “fair” at the 12-month point. In the end, patient satisfaction was high at 98% (“good” or “perfect”) at 12 months. The positive changes that patients liked (ranked from important to unimportant) were: (1) flatter and tighter lower abdomen; (2) higher waistline with appearance of longer lower limbs and better body proportions; (3) improved umbilicus shape; (4) elevated umbilicus; (5) clear corset lines; (6) evident upper abdomen midline trough; (7) improved groin lines; and (8) “six-packs.”

No health-related complications were encountered in the postoperative period. No seroma, hematoma, or infection was seen, nor was thread extrusion observed. The threads were all absorbed at 12 months, except for the knots just above the umbilicus which could usually be palpated at about 0.5 cm above the upper edge of the umbilici in almost every patient. One patient had occasional pain (2-3 on a scale of 0-10) in the upper abdomen for 2 months. Twelve patients (23%) reported soreness in the upper abdomen for the first 2 months. One patient developed 2 depressed scars in the groin ports, which were successfully treated with needle subcision and fat grafting. As many as 33 (63%) patients had pinpoint skin discoloration at the needle entry point. However, at 12 months, all but 4 (7%) of these pigmentations disappeared. These 4 patients were not concerned, however, because the discoloration had already become faint. The longest follow-up was 25 months, and this patient’s umbilicus shape and position stayed stable after the 12-month point (the PDO knots were confirmed to have been completely absorbed in this patient).

Discussion

In the first 2 years of my practice, liposuction was mainly performed for local fat reduction. Starting from 2008, I adopted Dr Hoyos’s principles for high-definition liposuction,1 and the results were quite gratifying. However, some dissatisfaction remained, especially regarding low-lying umbilici and lower abdominal “pooches” (Figures 2, 3). Subsequently, I tried to use SmartLipo (Cynosure, Westford, MA) laser lipolysis to solve these problems. In most cases, the abdominal skin did become tighter, and the umbilici could be elevated for a few millimeters. However, most umbilical shapes became worsened due to thermal injuries. Moreover, skin irregularities were common.

Borille et al tried to tackle the problem of the “sad umbilicus” after liposuction. They introduced 2 long 3-0 nylon sutures into the upper abdomen through the umbilicus. The sutures were tied over bolsters and removed 12 days later. Out of 62 patients, they saw increases in umbilicus length in 51 (mean increase, 3 mm at 9 months). Regrettably, umbilicus positional change was not mentioned.2 Nevertheless, the study did provide a plausible remedy for umbilicus deformities after liposuction.

Whereas there is little dispute exist as to what can be considered better-looking umbilicus shapes, the ideal umbilical position has been the subject of constant debate with hugely different opinions being expressed.3-6,12,13,14-16 XU/UP ratios of 1.12 and 1.13 were found in 2 separate studies,5,15 and the highest XU/UP ratio ever reported for a general population was 1.59.16 Note that these 3 studies were done in general populations, not models. Regardless of the arguments, optimizing umbilicus position unquestionably helps to achieve better results with abdominal rejuvenation.

This study demonstrated that PDO-thread-enabled umbilicus elevation after liposuction is highly effective and is accompanied by beautification of the umbilicus. The mean UIC was −0.1 cm at 12 months, close to the IC height, suggesting that this procedure restored the umbilical positions.2-4 It is remarkable that the mean XU/UP stabilizes at 0.98 after 12 months. Interestingly, this ratio is close to the finding by Dubou et al, who studied 100 nonobese subjects and found that the average XU/UP ratio was 1.03.17

Further analysis showed that the lower abdomen became elongated and tightened. Consequently, “pooch” appearances in the lower abdomen were drastically reduced (Figures 5, 6). Moreover, because the umbilici were elevated, higher waistlines could be created to match the elevated umbilici (a low-lying umbilicus does not match a high waistline aesthetically) (Supplemental Figures 1, 2). This raised waistline visually increased lower limb lengths (Figure 6G), which is vital for patients with shorter limbs.

Because most of the superficial fat is removed by liposuction and fibrous tissues remain, the long lifetime of the PDO threads (6-8 months) helps the lifted skin and umbilicus to heal in a lifted position. It is intriguing that the bunched upper abdominal skin became shortened and smoothened after PDO thread absorption (Figures 5, 6, 8). DeLorenzi believes that barbed threads capture tissues and compress them, and the threads subsequently become encased in fibrous tissues, eliciting a biologic response. The response achieved by the diminution of tensile forces on skin is the opposite of the response achieved when tension is applied (tissue expansion). This effect may entail programmed cell death or apoptosis in tissues that have had tensile forces reduced, eventually resulting in attrition of excess skin.18 Based on this theory, liposuction-induced “honeycombing” of the subcutaneous tissue may make this effect more pronounced, because of less tissue burden and resistance. Hence, more significant skin attrition/reduction could be achieved (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Sagittal view of the changes of the abdominal wall after the insertion of bidirectional polydioxanone threads for elevation of the umbilicus and the lower abdomen. Note that after the upper abdominal tissue is engaged by the cogs on the threads and cinching takes effect, the upper abdominal skin becomes bunched, while the umbilicus is lifted, and the lower abdomen is stretched up. After 6 to 8 months, the polydioxanone threads are absorbed, yet the umbilicus remains lifted. The upper abdomen becomes shortened, flattened, and smoothened, and the lower abdomen stays stretched up and flat.

Another crucial factor that might have contributed to the success of this innovation is the preservation of the Scarpa’s fascia. Lancerotto et al found that the Scarpa’s fascia contains abundant well-organized elastic fibers. They suggest that the Scarpa’s fascia plays a key role in the mechanical homeostasis of the abdominal wall and participates in balancing the outward-directed abdominal pressure. Further, it may also be important in the skin “contraction effect” after liposuction.19 The importance of Scarpa’s fascia could further be inferred from the findings in patients who had all abdominal fat and fascia layers destroyed by improperly performed liposuctions (confirmed during abdominoplasties on these patients by the author; data not shown). When examined, their skin lacks turgor and feels doughy, likely due to loss of elasticity of the Scarpa’s fascia.

It is interesting to note that in the survey, 3 of the top 4 higher-ranked positive changes (rated by the patients themselves) were related to the use of PDO threads (ie, umbilicus improvement and lifted lower abdomen), and the changes directly associated with high-definition liposuction were ranked lower. This is surprising, yet understandable. After all, sculpted “six-packs” are visible only when flexed. Further, the beauty of female bodies lies in their curves and proportions, not in their masculine features. Based on the above findings, it is probably safe to suggest that this study might have identified some crucial missing elements of high-definition liposuction, at least in the eyes of these female patients. It is quite possible that if male patients were studied with this technical innovation, their preferences for the positive changes would be completely different from those in this study. For instance, male patients may not pay as much attention to umbilical shape as females do. On the other hand, “six-packs” could prove to be much more important than anything else to males. Additionally, waistlines might not be as important to the male patients. However, improvements in umbilicus positioning and lower abdominal “pooch” should be an important consideration for them. These points should be easily observable in studies with male patients.1,8

This study has some issues that need to be considered: (1) no energy device was used;2,7,8 (2) no attempt was made to aggressively etch the apical fat layer, because this layer contains abundant skin organelles and lymphatics;20 (3) the liposuction ports, except for the umbilicus, were left open for drainage, limiting seroma formation;8 (4) only a small (3-mm, Mercedes-type) cannula was used with power-assisted liposuction, which greatly reduced tissue trauma; (5) whenever any skin irregularity or divots were found after liposuction, fat was grafted back immediately or during the first 2 postoperative visits; (6) only modest pressure was applied on the abdomen, limiting impediment of blood circulation.

One of the limitations of this study is the small number of patients enrolled. On top of that, not all patients could be followed. Some were from out of state or abroad, and others may simply not care. Even worse, some may be unsatisfied with the results. Although the latter was rare, as the patients were seen at least 2 days in a row after surgery, and the initial satisfactory results were confirmed by both the patients and our team, this limitation should nonetheless be noted.

The retrospective nature of this study is another limitation. A paired study for patients undergoing high-definition liposuction with or without PDO-thread-assisted umbilicus elevation could help to fully assess the exact effectiveness and the extent of umbilicus improvement. Further, because patients with higher BMI and loose skin were treated with abdominoplasty, the effectiveness of this treatment modality regarding the patients’ BMI and skin laxity could not be fully evaluated. The fact that the only patient who rated her result “fair” had a BMI of 31.6 kg/m2 suggests that a weight limit might be appropriate for the procedure. In this regard, a prospective study could help to clarify this issue and the definitive differences in various aspects of abdominal improvement between groups with or without PDO thread usage.

In this study, only the central upper abdomen, the umbilicus, and the immediate lower abdomen benefited from the PDO-thread-assisted lifting effect. At present, I have already started placing PDO threads after liposuction in 3 vectors: one as described here, and 2 along the corset lines, with the anchoring points at the inframammary folds, utilizing the strong circum-mammary ligaments.21 Patients with high BMIs are being treated with this new protocol to save them from abdominoplasties. Preliminary results are very encouraging and will be reported in due course. I am hoping that in the future more vectors could be added as we accumulate more experience—of course, with the prerequisite of not causing additional complications.

Yet another limitation is that our survey questionnaires were not validated by a third party and only limited questions were supplied to the patients. This issue will be addressed in our future cases. At least 1 more limitation does exist as far as the thread length. Ideally, the entry point should be high enough for the threads to catch the robust circum-mammary ligaments,21 just under the xyphoid process. However, for exceedingly long upper abdomens, the 43-cm threads could be too short to accommodate such a requirement. Consequently, the entry points were lower than the circum-mammary ligaments for these patients. Accordingly, this could have resulted in less efficient umbilical elevation.

The reason for tying the threads, instead of utilizing the bidirectional nature of the PDO threads as done in most clinical applications for PDO thread facelift (ie, no tying), is based on the author’s clinical observation. Tying the thread ends significantly increased the efficacy of the cinching effect on the upper abdominal skin, by at least 50% or more. Further, when threads were left untied after insertion and tissue catching, the lifting effect disappears rapidly, most likely due to the “cheese-wiring” effect from both directions, instead of one direction. On the other hand, by tying the thread ends, the threads became “looped,” lessening the “cheese-wiring” effect, especially on the lower end, with the presence of the “big knots” just above the umbilicus. As stated in the Results, in many patients, the knots could still be palpated at about 0.5 cm just above the umbilicus at 12 months, suggesting that no “cheese-wiring” ever took place from this end, even though the rest of the threads were already absorbed as per my examination. This phenomenon promoted me to think that for patients who need extremely effective umbilicus and lower abdominal elevation, a specially designed long PDO thread with thickened midsection could help to minimize the “cheese-wiring” effect and thereby offer much better results. My practice not only follows the manufacturer’s recommendations for applying MINT43 threads, and for fixing the threads on the superficial temporal fascia with knotting, but also avoids any thread extrusion or “spitting” (no free thread end for any “spitting” or extrusion to take place). I therefore routinely tie the thread ends for PDO thread facelift, and find that the facelifting effect is more significant and lasts much longer (data not shown).

Before this study, meaningful umbilicus elevation could only be achieved with abdominoplasty or reverse abdominoplasty. It is possible that the application of this PDO-thread-assisted high-definition liposuction technique could avoid many abdominoplasties, especially for some borderline candidates. In addition to the advantages of higher waistline creation, this procedure restores the umbilicus shape and position and flattens the lower abdominal “pooches.” The result is that most patients could obtain a result that resembles their original abdominal shapes and forms as when they were young or before their pregnancy/pregnancies. Consequently, I would like to name this procedure “restoration liposuction” or “restoration high-definition liposuction,” to emphasize its restorative nature and to differentiate it from traditional high-definition liposuction (Video 3, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com).

Conclusions

Due to its novelty and the fact that this study is from a single clinic, the results here should be viewed as a preliminary report. This novel technique uses absorbable, barbed PDO threads after high-definition liposuction to engage the upper abdominal skin, causing the tissues to heal at an elevated level. It enables permanent lifting of the umbilicus and the lower abdomen. At the same time, the umbilical shape is also optimized. Furthermore, because the umbilicus is elevated, higher waistlines can be created without any discordance, making the lower limbs appear longer. As a result, ultimate “high-definition” liposuction of the abdomen becomes a true possibility. I hope that this innovation will usher in a new wave of ideas and perhaps another revolution to follow that of Dr Alfredo Hoyos’s modern concepts in body sculpting.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material located online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

References

- 1.Hoyos AE, Millard JA. VASER-assisted high-definition liposculpture. Aesthet Surg J. 2007;27(6):594–604. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borille G, Neves PMA, Filho GP, Kim R, Miotto G. Prevention of umbilical sagging after medium definition liposuction. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41(4):463–473. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjaa051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee SJ, Garg S, Lee HP. Computer-aided analysis of the “beautiful” umbilicus. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34(5):748–356. doi: 10.1177/1090820X14533565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig SB, Faller MS, Puckett CL. In search of the ideal female umbilicus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(1):389–392. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200001000-00062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parnia R, Ghorbani L, Sepehrvand N, Hatami S, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Determining anatomical position of the umbilicus in Iranian girls and providing quantitative indices and formula to determine neo-umbilicus during abdominoplasty. Indian J Plast Surg. 2012;45(1):94–96. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.96594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoyos A, Perez ME, Guarin DE, Alvaro M. A report of 736 high-definition lipoabdominoplasties performed in conjunction with circumferential VASER liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(3):662–675. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wall SH Jr, Claiborne JR. Discussion: a report of 736 high-definition lipoabdominoplasties performed in conjunction with circumferential VASER liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(3):676–678. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Husain TM, Salgado CJ, Mundra LS, et al. Abdominal etching: surgical technique and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(4):1051–1060. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohrich RJ, Beran SJ, Kenkel JM, Adams WP Jr, DiSpaltro F. Extending the role of liposuction in body contouring with ultrasound-assisted liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(4):1090–1102; discussion 1117-1119. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199804040-00033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YH, Cha SM, Naidu S, Hwang WJ. Analysis of postoperative complications for superficial liposuction: a review of 2398 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):863–871. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318200afbf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul MD. Barbed sutures in aesthetic plastic surgery: evolution of thought and process. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(3_Supplement):17S–31S. doi: 10.1177/1090820X13499343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wall SH Jr, Lee MR. Separation, aspiration, and fat equalization: SAFE liposuction concepts for comprehensive body contouring. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(6):1192–1201. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruekers SE, van der Lei B, Tan TL, Luijendijk RW, Stevens HP. “Scarless” umbilicoplasty: a new umbilicoplasty technique and a review of the English language literature. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63(1):15–20. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181877b60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez E, Alvarez D, Caldeira A. Non-scarring minimal incision neo-omphaloplasty in abdominoplasty: the Alvarez technique. A new proposal. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:e3956. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambardar S, Cabot J, Cekic V, et al. Abdominal wall dimensions and umbilical position vary widely with BMI and should be taken into account when choosing port locations. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(9):1995–2000. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9965-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abhyankar SV, Rajguru AG, Patil PA. Anatomical localization of the umbilicus: an Indian study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(4):1153–1157. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000204793.70787.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubou R, Ousterhout DK. Placement of the umbilicus in an abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1978;61(2):291–293. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197802000-00030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLorenzi CL. Barbed sutures: rationale and technique. Aesthet Surg J. 2006;61(2):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2006.01.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancerotto L, Stecco C, Macchi V, Porzionato A, Stecco A, De Caro R. Layers of the abdominal wall: anatomical investigation of subcutaneous tissue and superficial fascia. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011;33(10):835–842. doi: 10.1007/s00276-010-0772-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrade M, Jacomo A. Anatomy of the human lymphatic system. Cancer Treat Res. 2007;135(2):55–77. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69219-7_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rehnke R, Groening R, Buskirk E, Clarke J. Anatomy of the superficial fascia system of the breast: a comprehensive theory of breast fascial anatomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(11):1135–1144. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.