Telemedicine in plastic surgery was rarely used prior to COVID-19, mainly for triage decisions in burn and trauma care. Efforts to minimize in-person encounters during the pandemic precipitated adoption of telehealth technologies, like Zoom Meetings™, expanding its use to routine surgical consultations. Survey results found that 79% of plastic surgeons implemented a telemedicine program during the pandemic, a dramatic increase from 19% pre-pandemic.1 This shift in telehealth use provided an opportunity to define which patients benefit most from telemedicine and which require in-person visits. We hypothesized that increased awareness of telehealth options would lead to their selection by patients and physicians, particularly when travel costs are high.

Methods

We obtained institutional review board approval for a retrospective chart review of 3237 patients seen in the plastic surgery clinic by three attending surgeons over the 3 months pre- and post-COVID-19 policy implementation in March 2020. T-Testing and Chi-squared analysis were used to compare patients evaluated over telehealth versus in person and to compare their characteristics before and after COVID-19 policies were implemented. Data collected included age, gender, ethnicity, home address, visit type (new, pre-operative, post-operative, return), visit attendance, visit indication (breast, upper extremity, craniofacial, wound care, other and reconstructive vs. cosmetic), and visit modality (telehealth vs in-person). Telehealth encounters were performed using Zoom™ software for either audio or video calls based on patient connectivity and available technology.

Results

Clinic visits fell by 29.8% from 1902 to 1335 in the 3 months following COVID-19 lockdown while telehealth use increased from 0% (n = 0) to 8.76% (n = 117) of all visits. No-show rates were 10% (n = 191) before and 13% (n = 158) after lockdown (p = 0.105), but comparing in-person to telehealth show rates, the no-show rate was 11% (n = 134) for in-person encounters and 20% (n = 23) for telehealth visits (p = 0.006). Telehealth utilization varied among providers, with 26 visits (4.7%) scheduled by attending one, 54 visits (11%) scheduled by attending two and 37 visits (13%) scheduled by attending three (p < 0.001). Most telehealth visits were for return patients (77%) though 12% were for new patients (Supplementary Table 1). Breast patients accounted for the largest portion of in-person visits (33%) while hand patients were the majority of telehealth visits (47%) (Supplementary Table 2). There were no significant differences in age or gender between patients seen via telehealth and in-person.

Pre-lockdown patients traveled an average of 63 kilometers (median 40 km) (Supplementary Material 3) and post-lockdown they traveled 59 kilometers (median 40 km) (Supplementary Material 4) (p = 0.19). When comparing the distance traveled post-lockdown for in-person visits ( Figure 1) vs the expected distance traveled for telehealth visits ( Figure 2) there was a trend towards increased distance in the telehealth group with a mean of 59 km versus 66 km and a median of 40 km versus 53 km (p = 0.26).

Figure 1.

This heatmap shows the number of patients seen in person from each Missouri zip code after lockdown.

Figure 2.

This heatmap shows the number of patients seen virtually from each Missouri zip code after lockdown.

The mean estimated one-way travel time pre-lockdown was 55 min and post-lockdown was 53 min (p = 0.16). Comparison between in-person travel time post-lockdown and expected travel time for telehealth visits demonstrated expected mean travel of 57 min for telehealth users and 52 min for in-person visits (median 47 min and 39 min respectively) (p = 0.14) (Supplementary Material 5). Of note, no out-of-state patients were seen via telehealth.

Discussion

Telemedicine benefits include reduced travel, increased convenience, reduced costs, and improved access for patients.2 As such, we hypothesized that patients living far from plastic surgery clinics, who face higher travel costs, would prefer telehealth options. While not statistically significant, patients who utilized telehealth saved an average of 114 min and 132 kilometers of travel. Using average hourly earnings of $21.41 and cost per kilometer of $0.385, this equates to a savings of $40.68 in lost wages and $50.85 in vehicle running cost per appointment.3, 4

The data support telehealth use for return visits, especially for upper extremity evaluations since range of motion and surgical incisions are easily assessed over videoconference. However, concerns regarding infrastructure capacity, limitations of physical examination, and data protection for virtual visits should not be understated.5 If we presume that patients’ and surgeons’ actions indicate their preferences then, from our data, patients and physicians still prefer in-person visits, particularly for surgical care.

We acknowledge the limitations of this study, which is a single-center study describing the experience of three surgeons in an academic hospital located in a suburban region of the United States, primarily serving a suburban and rural population. Experiences at other centers may differ from ours. In summary, COVID-19 triggered rapid implementation of a telehealth system to maintain access to healthcare while minimizing risk to patients and providers. Our plastic surgery division primarily used telehealth for return visits, with significant variation in utilization amongst providers. In-person visits remain the gold standard for plastic surgeons, and despite the monetary and temporal costs associated with those visits, patients are willing to make the trip.

Funding

No funding was obtained for completion of this work. Products used to complete the work include Zoom Meetings™ teleconferencing software, the Microsoft Office suite and Google Maps API.

Ethical approval

This project was approved by the University of Missouri institutional review board project # 2050142.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that there are no relevant conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Presentations: International Confederation of Plastic Surgery Societies 2022 in Lima, Peru; University of Missouri Health Science Research Day 2021 in Columbia, Missouri, USA.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2023.06.036.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary Material 1 and 2. Detailed description of visit types and indications by visit modality.

.

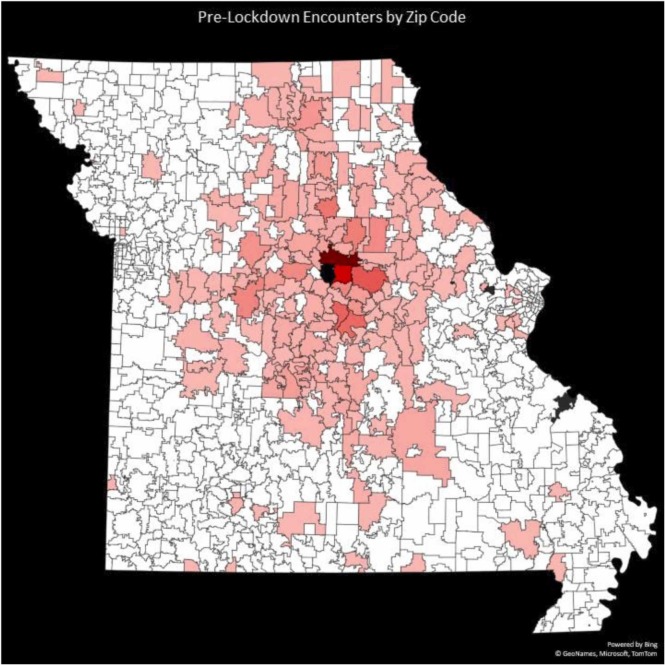

Supplemental Material 3. This heatmap shows the number of patients seen from each Missouri zip code before lockdown.

.

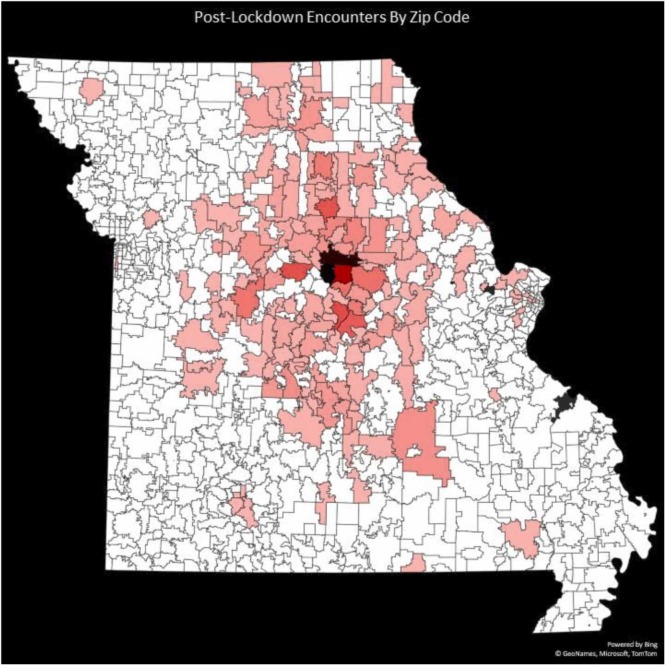

Supplemental Material 4. This heatmap shows the number of patients seen from each Missouri zip code after lockdown.

.

Supplemental Material 5. This box plot compares expected travel times for patients pre-lockdown, post-lockdown, and seen in person, to time avoided for patients seen via telehealth.

.

References

- 1.Calderon T., Skibba K.E.H., Langstein H.N. Plastic surgeons nationwide share experience regarding telemedicine in initial patient screening and routine postoperative visits. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(7) doi: 10.1097/gox.0000000000003690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saad N.H., Alqattan H.T., Ochoa O., Chrysopoulo M. Telemedicine and plastic and reconstructive surgery: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic and directions for the future. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;680E-683E doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistics BoT. Per-mile costs of owning and operating an automobile (current dollars). Transportation UDo.

- 4.Missouri Economic Research and Information Center. County average wages. 〈https://meric.mo.gov/data/county-average-wages〉.

- 5.Gillman-Wells C.C., Sankar T.K., Vadodaria S. COVID-19 reducing the risks: telemedicine is the new norm for surgical consultations and communications. Aestheti Plast Surg. 2021;45(1):343–348. doi: 10.1007/s00266-020-01907-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1 and 2. Detailed description of visit types and indications by visit modality.

Supplemental Material 3. This heatmap shows the number of patients seen from each Missouri zip code before lockdown.

Supplemental Material 4. This heatmap shows the number of patients seen from each Missouri zip code after lockdown.

Supplemental Material 5. This box plot compares expected travel times for patients pre-lockdown, post-lockdown, and seen in person, to time avoided for patients seen via telehealth.