Abstract

Accurate and efficient methods for identifying and tracking each animal in a group are needed to study complex behaviors and social interactions. Traditional tracking methods (e.g., marking each animal with dye or surgically implanting microchips) can be invasive and may have an impact on the social behavior being measured. To overcome these shortcomings, video-based methods for tracking unmarked animals, such as fruit flies and zebrafish, have been developed. However, tracking individual mice in a group remains a challenging problem because of their flexible body and complicated interaction patterns. In this study, we report the development of a multi-object tracker for mice that uses the Faster region-based convolutional neural network (R-CNN) deep learning algorithm with geometric transformations in combination with multi-camera/multi-image fusion technology. The system successfully tracked every individual in groups of unmarked mice and was applied to investigate chasing behavior. The proposed system constitutes a step forward in the noninvasive tracking of individual mice engaged in social behavior.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12264-022-00988-6.

Keywords: Noninvasive tracking, Deep learning, Multi-camera, Mouse group, Social interaction

Introduction

Animals typically live in social groups and display complex behavioral interactions that are of considerable importance to reproduction and the development of both individuals and social groups [1–3]. In addition to these behavioral patterns, which include maternal [4, 5], aggressive [6, 7], and reproductive behavior [8, 9], social interactions are known to be relevant in many psychiatric disorders [10, 11] (e.g., autism [12, 13], schizophrenia [14], depression [15], substance abuse [16], and anxiety [17]) in humans and modeled in non-human animals. To examine these patterns, animals are typically kept in controlled environments that restrict their movements and behaviors, such as the three-chamber test [18–20] and the tube test [21, 22], and these environmental restrictions usually alter or limit the behaviors being studied or result in artificial or contrived behaviors that are not necessarily related to natural behaviors [23, 24]. However, despite the growing literature evaluating behavioral and social interactions [25–30], accurately identifying and tracking an individual animal in a group has remained a major challenge because of the complexity of animal interaction patterns, including occlusion, crossing, and huddling [30, 31].

Video-based tracking systems play an important role in monitoring and tracking the behavior of individual animals and contribute positively to biology and neuroscience studies [32, 33]. Initially, thresholding and binarization techniques were widely used to track individuals [34, 35], and the methods used to track multiple individuals typically involved differentiating them based on physical differences (size or color or the presence of dyes of various colors). For example, marking mice by bleaching different patterns into their fur achieved a 99.4% recognition accuracy for a group of four mice [36]. Marking mice with composite dyes that emit different colors under ultraviolet light resulted in an identification accuracy of 99.6% for a group of four mice in 500 randomly-selected images taken by one color-sensitive camera [37]. Using a similar method, the trajectories of four mice using color markings for 12 h showed stable differences between individuals that were interpreted as representing different personalities [33]. Nevertheless, color markings are usually not permanent, and the gradually-fading color features would increase the risk of error when tracking multiple individuals.

The ability of video-based tracking to detect complex behaviors in animals can be enhanced through combination with other technologies. For instance, a video-based tracking model was implemented that incorporates radio-frequency identification (RFID) to monitor individual rodent behavior in complicated social settings [38]. RFID technology contributed to location-related (rather than trajectory-related) information on 40 mice in a large enriched environment; this approach was able to quantify the behavioral characteristics of individual mice [39]. Meanwhile, a combination of RFID and a camera achieved a tracking accuracy of 97.27% in a group of five mice in a semi-natural environment and was applied to the quantitative analysis of social levels within mouse populations [40]. However, implanted chip technology requires specific surgical skills, and invasive operations can affect animal recognition and behavior [41–43].

Non-invasive tracking of unmarked animals has been greatly aided by the development of machine learning algorithms. Using a foreground pixel-clustering and identity-matching algorithm, the trajectories of 50 individual fruit flies have been tracked, allowing differences in behavior to be identified at the individual level [44]. Subsequently, the MiceProfiler system used computer vision and an a priori geometrical constraints algorithm that permits tracking and quantitative evaluation of social interactions between two unlabeled mice by calculating mouse-body geometric characteristics [45]. Later, Hong et al. used depth-sensing technologies to track two mice with different fur colors and applied video-based tracking approaches to detect social behaviors such as mating and fighting in mice [29]. In 2014, Pérez-Escudero et al. established the idTracker system based on a color correlogram transformation that extracts data fingerprints, enabling it to differentiate among individual animals throughout the study; this method has been used to track unmarked animals and achieved recognition accuracy of 99.5% for five zebrafish and 99.3% for four mice [30]. In 2019, Romero-Ferrero et al. established the idTracker.ai system based on a convolutional neural network (CNN) and achieved recognition accuracy of >99.9% for groups of >60 zebrafish or fruit flies [25]. Besides, the idTracker.ai system is also able to track a group of mice, and we have compared it with our proposed system in the following study. Overall, video-based tracking methods have proven highly effective at detecting movements and social interactions even in large, unmarked groups, including zebrafish and flies. However, tracking groups of mice, the most widely-used experimental animals, is still challenging compared with zebrafish and flies. The motion patterns among rodents are more complicated due to their flexible bodies, and the tracked shape or size of the animal is usually continuously changing. The features of the same mouse in different behaviors (e.g., curled up in a ball or rearing) can vary greatly, making it difficult to extract efficient and stable data fingerprints to differentiate unmarked individuals. The study of mouse tracking is still challenging in identifying individual mice, especially when faced with crossing, huddling, and occlusion.

Driven by big data and high computing power, deep learning (DL) has achieved great performance in many challenging animal behavior tasks, such as pose estimation [32, 46–48], whole-body 3D-kinematic analysis [49–51], and chimpanzee face recognition [52]. In object-tracking problems, multi-camera systems have been widely used to increase tracking accuracy and robustness [53, 54]. Here, we established a multi-object tracker for mice (MOT-Mice) powered by multi-camera acquisition and a deep learning algorithm for the marker-free tracking of individuals within a group of up to six mice. Using the MOT-Mice system, we found that unfamiliar wild-type C57BL/6 male mice exhibited significantly more chasing (following) behavior, a typical social interaction behavior in mouse groups [36, 55, 56], than familiar mice. Our experimental results established that the MOT-Mice system is able to track a group of mice even though there were crossings, occlusions, and huddling.

Materials and Methods

Multi-Camera System Configuration

The multi-camera system included one experimental box without a lid, 4 cameras (Hikvision Digital Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China), and a set of multi-camera synchronization recording software programs (iVMS-4200, Hikvision Digital Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) (Fig. S1). The resolution of the camera was 1280 pixels × 720 pixels. The cameras had a lens focal length of 4 mm and an aperture of F2.0. The experimental box was made of transparent acrylic panels and its dimensions were 60 × 60 × 50 cm3. The primary camera was placed above the experimental box, while the three auxiliary cameras were distributed on three sides of the box. The computer with the synchronous recording software was connected to the 4 cameras through a 4-port Ethernet switch to implement video recording and to set camera parameters. The videos recorded by the cameras were temporally corrected to ensure that the videos acquired by all the cameras were completely synchronized (Fig. S2). In the positive control experiment, the videos included a timer display such that the same frame in the 4 videos all showed the same time, indicating that they were synchronized.

Single-Camera Modeling

Cameras were calibrated with the MatLab R2019b Computation Vision Toolbox (The MathWorks, Inc., Massachusetts, USA), including both single-camera modeling and multi-camera registration. We used checkerboard feature detection for calibration. The definitions and descriptions of the checkerboard feature extractor are shown in Fig. S3. The size of the checkerboard pattern used in this experiment was 16 × 17 squares (height × width), and the size of each square was 30 × 30 mm2. For camera calibration in three dimensions, the checkerboard-pattern board was placed inside the experimental box at 15 different angles, and each of the cameras took one picture at each placement. The 15 checkerboard images were used to establish a single-camera pinhole imaging model. A point was projected from the world coordinate system ([X Y Z 1]) to the pixel coordinate system of a camera ([x y 1]).

,

,

,

,

,

,

where P denotes the camera matrix, m denotes the scale factor, Q and K denote the extrinsic and intrinsic parameters, respectively, and R and T denote the rotation matrix and translation vector, respectively. The extrinsic parameters of the single-camera model represent a spatial transformation between the world coordinate system and the camera coordinate system (Fig. S4).

Then, the single-camera model was used to remove distortion in the checkerboard images and recorded videos caused by the lenses using the lens distortion model. The straight-line features in the world coordinate system were curved in the distorted images. The image correction operation corrected the points in pixel coordinates to recover the real features. Zooming out on the image to a proper scale ensured that the experimental region did not lie outside the edges of the images after correction.

Multi-Camera Registration

After detecting the feature points (the corners of squares in the checkboard image) in the undistorted checkerboard image, we transformed the feature points of the top-view and side-view cameras to the same coordinate system. The multi-camera registration was based on a general projective geometric transformation model. We projected each point in the original camera coordinate system ([u v 1]) to a unified coordinate system ([x y 1]).

,

,

where Tr is the transformation matrix. Then,

,

,

,

.

We solved , which consists of all the parameters in transformation matrix Tr, based on the checkboard image pattern for the kth feature point pair, the original point , and the projected point . The mathematical relationships for all the feature pairs are as follows:

.

The above matrix equations can be rewritten as:

,

.

The unified coordinate system was generated by fine-tuning the feature points of the top-view camera; then, all the feature points of the side-view cameras were projected to the unified coordinate system (Fig. S5). Although the registration errors of the auxiliary cameras [Camera 2 error: 0.347 ± 0.028 mm; Camera 3 error: 0.635 ± 0.040 mm; Camera 4 error: 0.175 ± 0.008 mm; n = 240 (15 × 14 checkerboard points)] were higher than the main camera error (Camera 1 error: 0.106 ± 0.005 mm) because the content in the side-view cameras had greater deformation (Fig. S6), all the multi-camera registration errors were very small compared to the average mouse body width (30.35 ± 0.45 mm; n = 15).

Mouse Detection by the Faster R-CNN Model

The MOT-Mice system, a mouse multi-object tracker, uses a Faster region-based CNN (R-CNN) model to detect all the individual mice in each image by marking them with bounding boxes. We constructed the Faster R-CNN model based on a pre-trained ResNet-18 model using transfer learning. During the model training process, data augmentation techniques based on various image transformation methods were used to improve model generalizability and avoid overfitting. These image transformation operations comprised image flipping (horizontal and vertical), image translation, saturation and brightness adjustment, and noise addition (Figs S7, S8). The image augmentation parameters were set as follows: random horizontal and vertical flipping with 50% probability, horizontal and vertical translation range [−40 40] pixels, random saturation modification range [−0.2 0.2], random brightness modification range [−0.2 0.2], and the addition of salt and pepper noise with a variance of 0.02 to each channel of the image. The deep learning architectures and experiments were implemented on a computer with MatLab R2019b software and configured with an NVidia GeForce GTX 1080 Ti GPU with 11 GB memory (NVIDIA Corp., Santa Clara, USA).

Evaluation of Mouse Detection Performance

Two criteria were used to evaluate the mouse detection performance: frame-based accuracy and individual-based accuracy. For an image with n mice and annotated bounding boxes (Bbox-n), the MOT-Mice system detected m mice and calculated their bounding boxes (Bbox-m). We determined the number of correct detections (K) by calculating the pairwise intersection over union (IoU) between Bbox-n and Bbox-m. A correct mouse detection meant that the IoU between Bbox-n and Bbox-m exceeded a threshold of 0.5. Then, the individual-based accuracy for this image was calculated as K/n. The average individual-based accuracy of >1,500 testing images for each group size (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, and 15) was used to evaluate the mouse detection performance. The original image size was 1280 pixels × 720 pixels. The distribution of the diagonal length of all the bounding boxes in the training and testing datasets is shown in Fig. S9A {diagonal length (pixels): median [interquartile range (IQR) Q1–Q3], 70.01 [IQR 79.76–98.86]}. The frame-based accuracy denotes the percentage of images with 100% individual-based accuracy (Fig. S9).

Comparison of Mouse Detection Performance Across Multiple Deep Learning Algorithms

We constructed Faster R-CNN models based on several excellent deep neural networks (SqueezeNet, GoogLeNet, and ResNet-18) to find the most appropriate model for the mouse detection task (Fig. S9). SqueezeNet is a compact 18-layer CNN architecture that has 50× fewer parameters than AlexNet but maintains AlexNet-level accuracy on the ImageNet dataset. GoogLeNet is a 22-layer CNN architecture designed with the Hebbian principle and the concept of multiscale processing to improve its computational efficiency. GoogLeNet consists of a repeated “Inception module” that moves from fully-connected to sparsely-connected architectures. Residual neural network (ResNet) uses identity mapping for all shortcuts and zero-padding to increase the dimensions without increasing the parameters. ResNet-18 is an 18-layer residual learning framework.

We constructed R-CNN, Fast R-CNN, and Faster R-CNN models based on ResNet-18 and compared their run-times for mouse detection (Fig. S10). All three models are gradually-optimized deep-learning algorithms [57]. The Faster R-CNN model achieved the best performance (the highest accuracy and lowest time consumption). The R-CNN model consists of three modules that generate region proposals and crop images, classify the cropped images, and refine the region proposal bounding boxes. Unlike the R-CNN model, the Fast R-CNN processes the entire image and then pools the CNN features to each region proposal for further classification. Fast R-CNN accelerates algorithm execution by sharing the computations for overlapping regions. Faster R-CNN is more efficient than the other models because its implemented region proposal network generates region proposals faster and more accurately.

To compare the performance of developed mouse detection models effectively, all the models used the same parameter settings: maximum number of strongest region proposals of 128, detection score threshold of 0.65, processing batch size of 16, and GPU execution environment.

Generating Tracklets From the Detection Results

The MOT-Mice system tracks individual mice detected by the Faster R-CNN model using a multi-object tracking algorithm, and it generates tracklets for each detected animal. In most cases, the mouse movements recorded by the camera (at a sampling frequency of 25 Hz) had smooth trajectories. As a result, the bounding boxes corresponding to the same mouse largely overlapped in two adjacent frames, while the bounding boxes corresponding to different mice had no or only small overlaps.

For two adjacent frames, we assumed that all the mice detected in the first frame have determined identities, while the mice in the next frame have only the detection results indicated by the bounding boxes but no identities. Then the core function of multi-object tracking is to assign identities to support the detection results of the next frame, or in mathematical terms, to identify the pairing method that maximizes the total IoU. We paired the bounding boxes in the two adjacent images and calculated the IoU matrix of these boxes. An IoU of 0 indicates that the two boxes do not overlap, while an IoU of 1 indicates that the two boxes overlap perfectly. We solved the identity assignment problem using the Munkres global nearest-neighbor assignment algorithm based on the pairwise IoU matrix.

To improve the tracking accuracy, the identity assignment operations were further optimized by setting two criteria according to the IoU. For the kth target bounding box (Bbox) in the previous frame (), the IoU between and each Bbox in the next frame () is denoted as , where i = 1, 2, …, n. The largest and second-largest values are denoted as and , respectively, denoting that the and in the next frame are the two Bboxes that overlap most with the in the previous frame. and are paired and considered to denote the same object when the following two criteria ( and ; Thre means threshold) are satisfied: (1) IoU value criterion: ≥ ; (2) IoU difference criterion: ≥ . Furthermore, we implemented a parameter optimization test on the parameters and . Our experimental results suggested that the optimal parameter settings are = 0.20 and = 0.15.

When no matching detection result occurred between the bounding boxes in the previous frame and the next frame, the corresponding trajectory segment in the previous frame was terminated. When a detection result occurred in the next frame and no matching bounding box could be found in the previous frame, a new trajectory segment was generated. This process was repeated iteratively until the entire video was analyzed and the tracklets of all the animals were obtained.

Mathematical Definitions of the Tracklets

Tracklets are the intermediate results of the multi-object tracking process. We fused the shorter tracklets to obtain longer trajectory segments until a complete trajectory was obtained. We used a 2D trace plot and a Gantt chart to describe the spatial and temporal information, respectively, contained in the tracklets (Fig. S11).

The mathematical definition of a tracklet is , , where Z denotes a tracklet and denotes a point in the Z tracklet. For a point , denotes the current bounding box, () denotes the center of , and denotes the current frame, which is usually the video frame index. The duration of tracklet Z denotes the number of frames or the number of points it covers and is calculated as Duration(Z) = N − M. Tracklet Z is a continuous trajectory when Duration(Z) is equal to the total number of frames in the video.

Tracklet Evaluation

Before conducting the trajectory segment evaluation, the ground-truth trajectories were obtained by manually clicking the centers of the targeted mouse frame by frame for each mouse. The evaluation metrics for tracklets focus on two aspects: accuracy and completeness. We adopted the following four metrics based on the most popular multi-object tracking challenge (MOT challenge) to evaluate the validity and reliability of the system: (1) the number of identity switches (IDS) in a tracked trajectory that differs from its matched ground-truth identity, (2) the total number of times a trajectory is fragmented (Frag) during tracking, (3) mostly lost targets (ML) represent the ratio of ground-truth trajectories that are covered by a track hypothesis for at most 20% of their respective life spans; and (4) mostly tracked targets (MT) represent the ratio of ground-truth trajectories that are covered by a track hypothesis for at least 80% of their respective life spans. The perfect values for IDS, Frag, ML, and MT are 0, 0, 0, and 100%, respectively. In the subsequent steps, we tried to decrease the values of IDS, Frag, and ML, and increase the value of MT by tracklet assembly.

Matchability of Tracklet Pairs

To ensure tracking accuracy, we set strict thresholds for generating tracklets from the detection results. As a result, the initial tracking results were almost free of identity switch errors but consisted of several fragments. To obtain the complete trajectory for each animal, we needed to fuse the tracklets belonging to the same animal. We calculated the matchability of two tracklet fragments to judge whether two tracklets belong to the same mouse and should be fused. For two tracklets P and Q,

The matchability of tracklets P and Q [Match(P, Q)] was determined based on both temporal and spatial criteria. First, we characterized the temporal relationship between tracklets P and Q. Assume P is prior to Q so that and . In other words, the endpoints of and are temporal neighbors, and tracklet assembly would occur between and if tracklets P and Q refer to the same animal. The tracklets P and Q temporally overlap when and do not overlap when . The temporal distance between and is . If the temporal distance between and is larger than the threshold [ > TempThre], then Match(P, Q) = 0 (Fig. S12).

For each tracklet pair that satisfied the temporal criterion, we then calculated Match(P, Q) based on spatial and temporal information. When the tracklets P and Q are separate, only their endpoints ( and are counted, i.e., Match(P, Q) =, where denotes the function used to calculate the spatial relationship between two Bboxes.

If tracklets P and Q temporally overlap, Match(P, Q) is the average matchability value of all the overlapping segments:

Two kinds of were used in this study: distance-dominated and IoU-dominated functions. The distance-dominated uses the distance between the centers of two Bboxes to characterize matchability. A higher value denotes lower matchability between tracklets:

.

The IoU-dominated uses the IoU between two Bboxes to characterize matchability. A higher value denotes higher matchability between tracklets:

.

Here we determined the definition and calculation of tracklet pair matchability, then we used it to guide the tracklet assembly operations.

Tracklet Assembly by Spatial Information

Next, spatial information-based tracklet assembly operations were used to calculate the spatial information between a target tracklet Q and multiple tracklets that may be fused {} and identify pairs of tracklets belonging to the same individual that can be fused. {} denotes the set of tracklet P, and the definition and calculation of Match (, Q) is the same as Match(P, Q). The matchability of a tracklet pair Q and , Match(, Q), is denoted .

Distance-dominated tracklet assembly calculates tracklet pair matchability by . The smallest and the second-smallest are denoted and , respectively. Then, tracklets Q and denote the same animal and can be fused when the following two criteria are satisfied: (1) a distance value criterion: ≤ ; and (2) a distance difference criterion: ≥ .

IoU-dominated tracklet assembly calculates tracklet pair matchability by . The largest and second-largest are denoted and , respectively. Tracklets Q and denote the same animal and can be fused when the following two criteria are satisfied: (1) the tracklet IoU value criterion: ≥ ; and (2) the tracklet IoU difference criterion: ≥ .

Parameter Optimization Test for Tracklet Assembly

The parameter optimization test assesses system performance under different parameter settings by changing the values of a single key parameter or combinations of the values of multiple key parameters. The goal of this test is to find the relationship between parameter values and system performance and to provide a reference basis for the parameter settings. Here, we implemented a parameter optimization test for three operations: generating tracklets from the detection results, distance-dominated tracklet assembly, and IoU-dominated tracklet assembly. All three operations had two key parameters. We conducted parameter optimization tests by setting different combinations of values for these key parameters. During the parameter optimization test, the parameters are optimized based on the conditions that the multi-object tracking performance is improved insofar as possible while satisfying the fundamental no-identity-switch principle. To generate tracklets from the detection results, eight parameter sets were tested for (, ): (0.02, 0.01), (0.05, 0.05), (0.15, 0.10), (0.20, 0.10), (0.20, 0.15), (0.25, 0.15), and (0.30, 0.20). For distance-dominated tracklet assembly, six gradually increasingly strict parameter sets were tested (, ): (50, 5), (45, 5), (40, 5), (40, 10), (30, 10), and (30, 15). For IoU-dominated tracklet assembly, 6 gradually increasingly strict parameter sets were tested (, ): (0.05, 0.05), (0.15, 0.15), (0.25, 0.25), (0.30, 0.25), (0.30, 0.30), and (0.35, 0.30).

Tracklet Assembly by Trace Prediction

At the trajectory breakpoints, we used a cascade-forward artificial neural network (C-ANN) for trace prediction, tracklet length extension, and trajectory segment assembly. We constructed the C-ANN model to predict the position of the next point from K (K = 24) consecutive trajectory points. The C-ANN model contains an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. The nodes in each layer were fully connected in the forward direction with the nodes in surrounding other layers. In addition, there were direct connections between the input layer and the output layer. The input layer had 48 nodes and accepted the position coordinates (x, y) of the K consecutive trajectory points. The hidden layer had 32 nodes with a tansig transfer function: tansig(x) = 2/[1 + exp(−2x)] − 1. The output layer had 2 nodes with a linear transfer function that output the predicted position of the next point.

During C-ANN model training, the training and testing datasets were automatically generated based on the tracking results. Although most of the tracklets were still not the final complete trajectories, many had extended durations and could be used to train the C-ANN model. The tracklets were divided into standard segments of length K + P, where P is the number of points that needed to be predicted. In addition, we used the trace similarity (TraceSimi) algorithm based on Euclidean distance to evaluate the trace prediction accuracy.

For two traces, and , with N points that were temporally fully overlapped,

, ,

, ,

where t = 1, 2, …, N.

The traces and were normalized as follows:

,

, ,

,

,

and TraceSimi =, where TraceSimi .

When the number of predicted points was 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10, the trace prediction accuracy (the similarity between the observed and predicted traces) was 0.9727, 0.9627, 0.9535, 0.9449, and 0.9368, respectively. To ensure the reliability of trace prediction, we set 0.95 as the trace similarity threshold and predicted a maximum of 6 points for the subsequent tracklet assembly process by trace prediction.

The prerequisite for tracklet Z to use the C-ANN was set to Duration(Z) ≥24, . For the last K points of tracklet Z, we obtained the forward tracklet prediction by iteratively repeating the C-ANN P times (P = 6):

.

We input the first K points of tracklet Z into the C-ANN in reverse and obtained the backward predicted tracklet by iteratively repeating the C-ANN process P times:

.

Trace prediction was carried out both forward and backward for all the tracklets after the initial assembly; then, the operations described above were conducted on the tracklets. For the tracklets that still could not be fused after trace prediction, the trajectory predictions were deleted, and the original tracklets were retained.

Tracklet Assembly from Multiple Camera Recordings

During the process of tracklet assembly from multiple camera images, the tracklets from the top-view camera dominate the process, while the side-view camera recordings are used to assist in tracklet assembly in conjunction with the main camera recordings. We applied the same operations for the videos from the side-view cameras as were described previously for the top-view camera, including mouse detection, multi-object tracking, initial tracklet assembly, and tracklet assembly by trace prediction. Notably, due to the imaging angle, the fields of view of the side-view cameras had sensitive regions that were defined as one-third of the area farthest from the camera. In the sensitive regions, the mouse individuals were relatively small and often occluded by other mice. In addition, objects in the sensitive region of the images were substantially deformed after camera registration. Therefore, we deleted the detection results in the sensitive region before conducting multi-object tracking for the side-view cameras. For the side-view cameras, mouse detection and tracking were achieved before image registration, and tracklets were generated after image registration.

We used the distance matrices between the tracklets of the top-view camera and the side-view cameras to achieve multi-camera fusion (Fig. S13). The distance between a tracklet P from the top-view camera and a tracklet Q from a side-view camera was determined by the TrackDist(P, Q) function:

, ,

, ,

,

,

,

, where denotes the spatial distance, is a temporal indicator and a value of 1 means that and refer to the same time point. The symbol denotes the length of the temporally overlapped segment between tracklets P and Q. When two tracklets P and Q do not overlap (), the distance is infinite.

The implementation of tracklet assembly by multiple cameras consists of two steps. First, a set of tracklets , defined from the top-view camera, with small distances between the same tracklets identified by a side-view camera is found:

,

, where the tracklets are from the top-view camera and tracklet Q is from a side-view camera; DistThre denotes the distance threshold for tracklet assembly by multiple cameras, and is usually set to the average mouse body width. Then, the output tracklet set belongs to the same mouse and should therefore be fused into a single tracklet.

Post-processing by Manual Checking and Correction

In rare cases, we identified some tracklets that could not be fused or for which the identities of the mice associated with the trajectories switched. The MOT-Mice system post-processes the tracking results through the MOT checking and correction (MOT-CC) module.

For the trajectory breakpoints that could not be automatically fused by the algorithm, the MOT-Mice system achieves manual fusion by artificially inputting the indexes of the paired tracklets. Then, the MOT-CC module automatically calculates a risk factor (high risk usually refers to close interaction scenarios) for each frame of the video based on the tracking results. If the distance between the two nearest mice is less than the risk distance (RiskDist = average body width), the frame was automatically marked as a risk frame; then, the segment of risky tracking results was replayed to an investigator to determine whether an identity error existed. For the trajectories with identity switches, the misaligned trajectories were broken by manually marking the trajectory index and the frame index. Then, the broken trajectories were fused by manually pairing the tracklets belonging to the same individual. Finally, the correct trajectories of all the individual mice were obtained.

Comparison of Tracking Multiple Mice Between Three Methods

idTracker.ai is the most recently reported model and is the state-of-the-art CNN-based system for tracking unmarked animal groups. We applied both the idTracker.ai and MOT-Mice systems to process two videos (2 min) with five unmarked mice. The trajectory of each mouse in these videos was manually tracked by iteratively clicking the center of each mouse in each frame. During the manual tracking process, the trajectories of the five mice were extracted individually; then, these trajectories were used as ground truth to evaluate the performances of the idTracker.ai and MOT-Mice systems. A qualitative criterion was used to evaluate the identity error of the trajectories. If an identity error exists in a tracker’s tracking result (either idTracker.ai or MOT-Mice), some mice would be mismatched between the 2D trace plot of the tracker and the manual tracking results (Fig. S14); otherwise, the 2D trace plots of the tracker and the manual tracking results should overlap almost exactly.

Animals and Experimental Settings

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Capital Medical University and were performed according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All the mice used in this study were specific pathogen-free wild-type C57BL/6J male mice aged 8–9 weeks purchased from Vital River (Vital River Lab Animal Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The temperature of the colony room was maintained at 20–26°C, and the humidity at 40%–70% with light and darkness alternating every 12 h. The mice were habituated to the testing room for 1 h before the tests. We cleaned the apparatus with 70% ethanol after each experiment and conducted the next experiment after a 10-min interval.

In social experiments involving familiar and unfamiliar groups, two litters of mice were used in each experiment. Four mice in each litter had marked tails: Litter a (a1, a2, a3, and a4) and Litter b (b1, b2, b3, and b4). On the first day of the test, open-field experiments were conducted with the two litters (Familiar-1 group), and the activity of the familiar group was recorded for 10 min. Then, the mice were returned to their home cages. On the third day of the test, the two litters were regrouped to obtain a mixed group. Mice a1, a2, b3, and b4 constituted one group, and mice b1, b2, a3, and a4 constituted the other group. The activity of the mixed mouse groups in an open-field environment was recorded for 10 min; then, the mice were returned to their home cages. On day 5 of the test, the activity of the 2 familiar mouse groups in the open-field environment was again recorded for 10 min (Familiar-2 group).

Definition and Recognition of Chasing Behavior

Chasing is a typical social behavior in mice. Mice not only chase each other for play but also during fights. Chasing is associated with a specific spatiotemporal relationship between the movements of two mice and can be recognized via mouse trajectories. An analysis of chasing demonstrated the effectiveness and potential application of the MOT-Mice system. We defined and calculated chasing behavior from two trajectories using the spatiotemporal method. The chasing was directional for each pair of mice. We used three criteria to recognize chasing. First, the distance between two mice should be relatively small (ChaseDistThre). Second, neither mouse can be standing still, and both mice should exhibit real-time location changes (i.e., their location variations within a short time window [−Lag Lag] should be relatively large (ChaseVarThre)). Third, one mouse must be behind the other during the chasing process. Notably, crossing behavior (two mice quickly cross over in a head-to-head manner) usually satisfies these three criteria but has a very short duration. To increase the reliability of chasing recognition, only events that satisfied these three criteria and lasted for >0.75 s were counted as chasing behaviors.

Statistical Analyses

All the statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA). The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Differences were considered statistically significant at *P <0.05.

Code Availability

The associated codes in this study are available online. The source code is available at https://github.com/ZhangChenLab/Multi-Object-Tracker-for-Mice-V1.2.

Results

Establishment of the MOT-Mice System

The MOT-Mice system performs the following four steps (Fig 1A): (1) registering images taken from the primary (individual top-view) camera and auxiliary (multiple side-view) cameras and projecting the images onto a normalized coordinate system, (2) using a deep learning-based algorithm to detect multiple animals in every image, (3) generating tracklets, a trajectory segment without interruptions, that include mouse identity using a multi-object tracking algorithm based on the mouse detection results, and (4) generating the trajectories of all the individual mice by tracklet assembly. When animal aggregation or trajectory breakpoints (the time points at which the identity of a mouse is lost) were encountered, trace prediction was used for tracklet assembly. For the breakpoints that could not be solved by the primary camera during the tracking process, the MOT-Mice system used images taken by the auxiliary side cameras to reconstruct the tracklets and obtain a continuous trajectory.

Fig. 1.

Multi-object tracker for mice (MOT-Mice) powered by multi-camera acquisition and a deep learning (DL) algorithm extracts the tracklets of unmarked mice in a group. A Flowchart of the MOT-Mice system. B Image registration using a checkerboard pattern (Fig. S3). Left to right: original distorted checkerboard image of camera-X and its corresponding pixel coordinate system; image with distortion removed by single-camera modeling using a pinhole imaging model and a radial distortion model (Fig. S4); image registration by projective geometric transformation. All images from all cameras are projected to a normalized coordinate system (Figs S5, S6). C DL-based mouse detection. Left to right: implementation of the Faster R-CNN model for mouse detection (Figs S7–S10); mouse detection accuracy versus group size. D Pre-tracking of multiple mice by a single camera based on spatiotemporal information. The mice in the previous frame are labeled by bounding boxes (Bboxes) with a specific color and assigned an identity (ID-x); then, the mice detected in the current frame are labeled (label-y). The intersection over union (IoU) value reflects the spatial relationship between the Bbox for ID-x and label-y. The solutions to the identity assignment problem are indicated by the connecting lines. The algorithm is repeated iteratively to obtain the tracking results as tracklets, which are shown as a Gantt chart (temporal information) and a 2D trace plot (spatial information) (Fig. S11). E Criteria for tracklet evaluations. The criteria for identity switches, fragments, and mostly lost targets are illustrated. Dotted line and small circle, the ground truth of trajectory. Solid line and large circle, the tracking results. F Parameter optimization test for IoU in identity pairing. The plot shows IoU settings versus tracklet evaluation criteria. Dotted red line, the perfect value for each criterion. Blue dotted line, the chosen parameter settings. The optimization tests were conducted using videos recorded with five mice. G Plot of tracklet fragments versus animal group size.

Projecting Multiple Cameras onto the Same Coordinate System

Since the MOT-Mice system incorporates images from different cameras and the images are usually distorted [especially when those from multiple cameras (Figs S1, S2) are processed together], each image needs to be calibrated to generate a normalized image. As such, we calibrated and normalized the images using a checkerboard feature-based spatial geometric transformation method (Figs 1B and S3–S6). Image distortion caused by the camera lens was first removed through image correction by a pinhole camera model and a radial distortion algorithm. Then, the images from different cameras were aligned by projection onto a single target coordinate system (Fig. 1B). In this manner, the image calibration module transformed the images from multiple cameras into a unified framework, providing a basis for the subsequent mouse detection process.

Detecting All Mouse Individuals in Each Frame

To detect individual mice in each frame, the MOT-Mice system uses deep learning object detection methods [i.e., the MOT-Mice object detection (MOT-OD) module] to detect the bounding boxes, the smallest rectangles enclosing each mouse (Fig. 1C). To train the MOT-OD model, we first established a large mouse image dataset. We assigned each mouse to a training or testing set before recording the videos (Fig. S7). For recorded videos with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, and 15 mice, we extracted frames at 2-s intervals. The images were then annotated with bounding boxes using MatLab; the training dataset consisted of 12,244 labeled original images with a total of 67,096 annotations, and the test dataset included 1,000 labeled images with a total of 5,324 annotations. The MOT-OD module used the Faster R-CNN model to detect the mice; a pre-trained deep learning network (ResNet-18) was used as the basis of the Faster R-CNN model. We used transfer learning and data augmentation techniques (Fig. S8) to fine-tune the model parameters. After training, the MOT-OD module achieved an average accuracy of 99.8% with transfer learning and 97.6% without transfer learning on the test dataset. We evaluated the accuracy of the MOT-OD module with transfer learning using an individual-based accuracy criterion (where the error reflects incorrect mouse detections) and a frame-based accuracy criterion (where the error reflects an image exhibiting incorrect mouse detection). The MOT-OD module analyzed 1,500 images under each experimental setting, namely, the presence of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, and 15 mice, and achieved gradually decreased individual-based accuracy (from 100% down to 97.75%) and frame-based accuracy (from 100% down to 91.27%) with increased group size (Fig. S9). We compared the three most popular and widely-used CNNs (ResNet-18, GoogLeNet, and SqueezeNet) and found that the ResNet-18 model achieved the highest mouse detection accuracy. We further compared the time consumption of R-CNN, Fast R-CNN, and Faster R-CNN. The Faster R-CNN model used a region proposal network to search for features and dramatically improved the mouse detection speed [the average detection times for each image by the R-CNN, Fast R-CNN, and Faster R-CNN models were 1.86, 0.53, and 0.18 s (10.39:2.94:1), respectively; Fig. S10]. The MOT-OD module achieved highly accurate performance in detecting all mouse individuals in each image and provided a sound basis for subsequently generating tracklets.

Tracklet Generation Based on Mouse Detection Results

To obtain a tracklet (Fig. S11), the same animal in two adjacent images was recognized by comparing the bounding boxes using the MOT-Mice identity pairing (MOT-IP) module. The mice detected in the two images (images A and B) were assigned identities (A-Mousei and B-Mousej). The pairing of IDs between two adjacent images was determined by the Munkres global nearest neighbor algorithm [58, 59], which solved the identity assignment problem by maximizing the total IoU between pairs (Fig. 1D).

Arguably, the most significant difficulty in multi-animal tracking is reflected in identity switches and fragments of varying lengths in the tracked trajectories. This phenomenon can occur when one mouse is occluded by another. The uncorrected and unsuccessful matches found by the MOT-IP module resulted in identity switches and tracklet fragments, respectively.

Trajectory accuracy, which is represented by identity switching, and trajectory completeness, which is represented by the numbers of tracklet fragments, mostly lost targets, and mostly tracked targets, are two important types of evaluation metrics in multi-object tracking (Fig. 1E). The parameter optimization test for IoU in identity pairing reflected the relationship between the performance of the MOT-IP module and the value of the key parameter pair (, ). We set the optimized value of (, ) to (0.20, 0.15) to ensure no identity switch and as few fragments as possible (Fig. 1F). By analyzing 3 sets of 5-min videos containing 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, or 10 animals (for a total of 21 videos) and validating the MOT-IP module, we found that on average, there were 0, 5.33 ± 0.58, 5.67 ± 1.53, 7.33 ± 1.53, 15.67 ± 4.04, 18.33 ± 2.08, and 106.67 ± 20.82 fragments in the 5-min videos containing 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 10 animals, respectively (Fig. 1G). To ensure tracking accuracy, we set strict rules for the MOT-IP process that led to no identity switches but resulted in several fragments. The MOT-IP module achieved relatively few tracklet fragments for the videos containing 1–6 mice and had great potential to be further assembled to obtain complete trajectories for each individual.

Parameter Optimization Test for Tracklet Assembly Using Spatial Information

We further explored trajectory completeness by tracklet assembly using spatial information that did not lead to a loss of trajectory accuracy (Figs 2 and S12). Both distance-dominated (Fig. 2A, B) and IoU-dominated (Fig. 2C, D) tracklet assemblies were adopted in this study, and a parameter optimization test was applied using the recorded videos with five mice. We tested two sets of gradually strict parameters for distance-dominated and IoU-dominated tracklet assemblies to find the optimized parameter settings. The optimized value of the key parameter pair (, ) for distance-dominated tracklet assembly was set to (30, 10) pixels to ensure that no identity switches occurred and to result in as few fragments as possible (Fig. 2B). The optimized value of the key parameter pair (, ) for IoU-dominated tracklet assembly was set to (0.30, 0.30) (Fig. 2D). We optimized the key parameters for distance-dominated and IoU-dominated tracklet assembly algorithms to increase the trajectory completeness without the loss of trajectory accuracy.

Fig. 2.

Parameter optimization test to achieve optimal performance in tracklet assembly by spatial information. A Processes of distance-dominated tracklet assembly. Left to right: Gantt chart and a 2D trace plot of six tracklets; a calculated distance-based spatial information matrix; the rule and results of distance-dominated tracklet assembly. Inf, infinite distance. B Parameter optimization test for distance-dominated tracklet assembly. The plots show distance settings versus the tracklet evaluation criteria. Dotted red line, the perfect value for each criterion. Blue dotted line, the selected parameter settings. The parameter optimization tests were conducted using recorded videos with five mice. C IoU-dominated tracklet assembly. From left to right: Gantt chart and a 2D trace plot of six tracklets; calculated IoU-based spatial information matrix; the rule and results of IoU-dominated tracklet assembly. D Parameter optimization test for IoU-dominated tracklet assembly. The plots show tracklet IoU settings versus the tracklet evaluation criteria. Dotted red line, the perfect value for each criterion. Blue dotted line, the selected parameter settings.

Trajectory Generation by Tracklet Assembly

The main problem in tracklet assembly is to find the tracklet that belongs to the same individual on both sides of a breakpoint. The MOT-Mice system uses two steps to solve this problem. First, it uses a trace prediction module (the MOT-TP module) to extend the tracklet at the breakpoint for both the overhead and auxiliary cameras (Fig. 3A). The MOT-TP module is a cascade-forward artificial neural network (C-ANN) trained to predict extended trajectory points in both the forward and backward directions through 24 consecutive trajectory points. After training the MOT-TP module with 7,838 automatically-generated training and testing tracklets, the trace prediction accuracy of the MOT-TP module (i.e., the similarity between the original and predicted traces) significantly improved. As the prediction length increased from 1 to 10 based on 24 consecutive points, the prediction accuracy gradually decreased. The accuracy for a prediction length of 6 points was 19.17% ± 3.09% in pre-training and 95.68% ± 0.25% in post-training. We then used the MOT-TP module to process 18 5-min videos containing 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 10 animals. The MOT-TP module successfully connected 68.89% ± 10.18%, 53.17% ± 12.22%, 54.23% ± 30.66%, 32.78% ± 15.12%, 41.95% ± 1.88%, and 13.22% ± 3.28% of the fragmented tracklets by identifying that they are attributed to the same mouse, but the performance degraded as the number of animals increased.

Fig. 3.

Tracklet assembly by trace prediction and multi-camera fusion. A Single-camera tracklet assembly obtained by trace prediction using a cascade-artificial forward neural network (C-ANN). Left to right: two non-continuous tracklets are extended by the C-ANN and fused; C-ANN architecture and a trace prediction accuracy versus prediction length (PL) plot. B Multi-camera tracklet merging. Left: non-continuous tracklets from the top-view camera and simultaneously continuous tracklets from the side-view Camera X; seven tracklets (A to G) extracted from the video fragment from the top-view camera, and three tracklets (AX, BX, and CX) extracted from the video fragment from the side-view Camera X (for the side-view cameras, mouse detection and tracking were achieved before image registration, and the tracklets were generated after image registration). Middle: pairwise tracklet distances between the top-view camera and side-view Camera X; tracklets A and F in the top-view camera belong to the same mouse, while tracklets D and G belong to a different mouse. Right: in the Gantt chart, the connecting arrows indicate that tracklets A and F and tracklets D and G should be connected; the mathematical model of tracklet merging by multiple cameras. The details regarding the two other side-view cameras in the same video segment are shown in Fig. S13. C Performance of the MOT-Mice system: remaining fragments versus the mouse group size. Black, only the main camera was used. Blue, the tracklet was generated by the main camera and fused by trace prediction. Red, the MOT-Mice multi-camera system was used. D Mouse group trajectories. Left: trajectories tracked by MOT-Mice. The trajectory of one mouse is highlighted in red, while the trajectories of the other four mice are denoted in gray. Right: comparison of the three tracking methods (black, manual tracking; blue, idTracker.ai; red, MOT-Mice; Fig. S14).

Next, to fix the remaining tracklets that could not be fixed by the MOT-TP methods, the MOT-Mice system used images collected by the auxiliary cameras to fuse the tracklets (Figs 3B and S13). For those images, the tracklets are obtained and processed in the same way as the images collected by the main camera. Specifically, the MOT-Match module aligns the broken trajectory with a trajectory obtained from auxiliary camera images. If the trajectory from the main camera at both ends of the breakpoint can be aligned with a continuous trajectory from an auxiliary camera, these two broken trajectories can be regarded as trajectories from the same animal. The data showed that the ability to repair breakpoints was significantly improved using the three auxiliary cameras relative to the repair ability using the main camera alone (Fig. 3C). The remaining trajectory breakpoints that could not be adequately resolved/fused for the 18 5-min videos containing 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 10 animals were 0.67% ± 0.58%, 0.33% ± 1.53%, 3.33% ± 1.53%, 4.67% ± 2.31%, 5.00% ± 1.00%, and 23.52% ± 5.27%, respectively, and we determined that the breakpoint-fixing performance depended on the number of animals and the number of cameras. In a 5-min video with 6 animals, the MOT-Mice system was able to track nearly complete trajectories of all the animals; only 0.117 breakpoints/(mouse per min) remained (3.51 remaining breakpoints in the 5-min video of 6 animals) (Fig. 3C).

The MOT-Mice system post-processed the tracking results through the semiautomatic checking and correction (MOT-CC) module. The MOT-CC module fuses the remaining trajectory breakpoints by human intervention and automatically finds the high-risk video segments in which two or more mice are very close to allow manual verification of whether an identity switch occurred. In an experiment tracking five mice, the trajectories generated by idTracker.ai exhibited identity errors, while all the trajectories generated by the MOT-Mice system without manual correction maintained correct identities (Figs 3D and S14). Hence, the MOT-Mice system achieved noninvasive tracking of every individual in unmarked mouse groups.

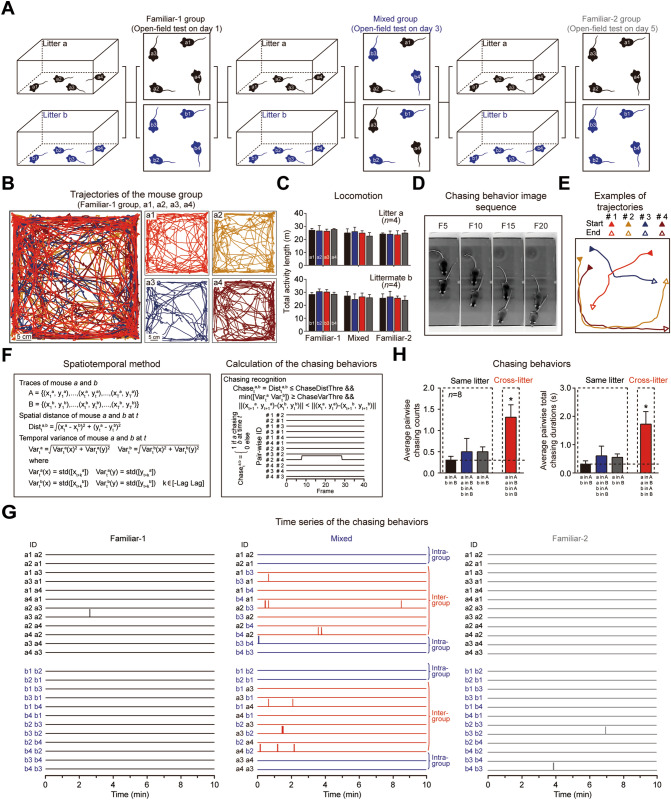

Application of the MOT-Mice System to Social Behavior (Chasing)

Finally, as proof of principle, we used the MOT-Mice system to investigate chasing behavior, which is a typical social interaction behavior in mouse populations (Fig. 4). Four mice were placed in an open field; then their chasing behavior over a 10-min period was investigated using the MOT-Mice system (Fig. 4A–D). Chasing behavior typically involves one mouse following directly behind another and was defined as the trajectories of two animals with a concomitant relationship. The accompanying relationship satisfies a distance and time threshold (in this study, these thresholds were defined as a distance between the two mice <30 mm that lasted for >0.75 s; Fig. 4E, F). We found that animals that had been housed together since birth rarely chased each other during the recording on the first day (rate: 0.3125 ± 0.0799 times/mouse pair, duration: 0.3264 ± 0.1013 s/mouse pair; Fig. 4G, H); however, when 4 mice from two different litters were put into the open field together, the cross-litter chasing count was significantly higher than the same-litter chasing count (rate: 1.3125 ± 0.2941 times/mouse pair, P <0.05; duration: 1.7238 ± 0.4460 s/mouse pair, P <0.05). This result demonstrated a social preference of mice for chasing novel peers. Thus, the MOT-Mice system provides a reliable and precise method for simultaneously tracking the movement trajectories of multiple mice that can facilitate the study of social behavior in mice.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the chasing behavior between two litters. A Experimental protocol. The experimental animals comprise two litters, each with 4 mice. The behaviors of the familiar-1, mixed, and familiar-2 groups were recorded for 10 min in the open field on days 1, 3, and 5. B Trajectories of the familiar-1 mouse group in the open field (10 min). Scale bar, 5 cm. C Summary graph of the total activity length for the mice in the familiar-1, mixed, and familiar-2 groups. D Image sequence of chasing behavior. FX, the Xth frame. E Sample trajectories from the mouse groups with 4 mice in the open field. The solid triangles indicate the start point for each mouse and the empty triangles indicate the endpoints for each mouse. F Mathematical definitions of the spatiotemporal method and the calculation of chasing behavior. Mathematical implementation of chasing behavior recognition and the time series of pairwise chasing behaviors for the trajectories in panel E. G Time series of the pairwise chasing behaviors for the familiar-1, mixed, and familiar-2 groups. Two sessions are shown for each group. Each session contains 12 pairwise directed chasing behavior of four mice. Each horizontal line denotes the chasing behavior of a mouse pair. The vertical lines denote the occurrence of chasing behavior. H Statistics of the chasing behaviors between the same-litter and cross-litter mice in the familiar-1, mixed, and familiar-2 groups. Left: average pairwise chasing counts. Right: average pairwise total chasing durations. Black, Familiar-1 group; Blue, Mixed group; Gray, Familiar-2 group; Red, Mixed group. Student’s t-test, n = 8, *P <0.05. Horizontal black dashed line, baseline of chasing behaviors in the Familiar-1 group.

Discussion

To overcome challenging problems in tracking unmarked mice in groups (such as the flexible bodies of rodents and close interactions), we established the noninvasive MOT-Mice tracking system based on artificial intelligence and multi-camera image fusion technology. The MOT-Mice system accurately detects unmarked individual mice using a deep CNN algorithm, and it also applies both multi-camera fusion and C-ANN technologies to assemble the fragmented tracklets and obtain complete trajectories.

Tracklet fragments are common in multi-object tracking. The MOT-Mice system used the MOT-TP module to assemble tracklets of the main camera first, then used multi-camera fusion technology to assemble the tracklets when the MOT-TP method failed. In the idTracker.ai system, animal crossing and occlusion scenarios are detected and abandoned; abandonment leads to the loss of critical information during social interaction and a high risk of misidentification [25]. The MOT-Mice system solved these problems directly by continuously detecting and tracking animals even when they engaged in close interactions such as crossing and huddling. This approach is more robust than single-camera tracking systems and can be applied to scenarios of different complexities (different arena sizes and numbers of animals, and environmental enrichment) and excellent scalability can be achieved by increasing or decreasing the number of monitoring cameras. Besides, this approach has the potential to fuse information from different kinds of cameras, such as infrared and regular cameras.

Many existing tracking systems detect animals using traditional image-processing methods such as image binarization based on thresholding algorithms. However, the existing systems have major limitations for use in experimental environments because their traditional image-processing methods are susceptible to the contrast between animals and environments. The MOT-Mice system applies the state-of-the-art Faster R-CNN model, which has won numerous competitions such as the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) and Common Objects in Context (COCO) [57], to achieve mouse detection. Furthermore, the ResNet-18 model [60] used to extract features has proven to be powerful in many complex tasks, such as natural image and medical image recognition [61, 62]. As a result, the MOT-Mice system can detect animals even from images with low contrast between the fur color and background (such as detecting black mice against a black background panel), as well as detecting individual mice in enriched environments (Fig. S15). The incorporation of deep learning techniques greatly extends the application potential of the MOT-Mice system.

There are also several reported DL-based solutions for animal pose estimation [32, 46–48], and animal whole-body 3D kinematic analysis [49–51]. DeepLabCut [46] and LEAP (LEAP estimates animal pose) [32] are powerful DL-based animal pose estimation tools, both of which require only a few data annotations and achieved high-performance prediction of animal body parts. In addition, the successors of the two tools, Multi-animal DeepLabCut (maDLC) [63] and social LEAP (SLEAP) [48], achieve multi-animal pose tracking. Both maDLC and SLEAP tools adopt a bottom-up approach to identify key body points and then assign them to individuals [64]. Although these tools (DeepLabCut, LEAP, maDLC, and SLEAP) have proven to be powerful and are widely used, they still lack detailed 3D behavioral descriptions of animal bodies. The CAPTURE (Continuous Appendicular and Postural Tracking Using Retroreflector Embedding) tool achieves week-long timescale tracking of the 3D kinematics of a rat’s head, trunk, and limbs [49]. The MouseVenue3D tool provides a hierarchical 3D-motion learning framework to acquire a markerless animal skeleton with tens of body parts [50, 51]. Notably, both the CAPTURE and MouseVenue3D tools applied multi-camera techniques and were designed for the individual animal. The MOT-Mice system was developed to track multiple animals using multi-camera fusion and deep learning techniques, and it may work cooperatively with these reported solutions to achieve a more sophisticated analysis of animal behavior.

There are two main limitations in this study. First, like the reported maDLC and SLEAP tools, the MOT-Mice system lacks an identity maintenance approach for animal identification [64]. When the number of animals increases and the animals interact closely and more frequently, the probability of identity-switch errors increases, leading to additional manual correction tasks. A possible solution is to use invasive RFID technology to ensure identity maintenance in the long-term tracking of multiple animals. Although the non-invasive MOT-Mice system has shown stronger adaptability to the experimental environment than traditional RFID-based solutions [38, 40], the combination of DL and RFID may enhance the system’s applicability for hours and even days of multi-animal behavioral video recording.

Another limitation of the MOT-Mice system lies in its inability to automatically mine complex interactions. In applying the MOT-Mice system to chasing behavior, it was necessary to define the chasing behavior before exploring the differences between same- and cross-litter chasing behaviors. There are many other important fine social behaviors, such as mating, fighting, and sniffing. However, when analyzing various fine behaviors, centroid-based metrics may not be accurate enough because of the lack of information. Combining the MOT-Mice system with pose estimation [48], whole-body 3D kinematics [50, 51], and visual features from original videos [65] would be more efficient for fine behavior analysis. Most importantly, advanced DL-based animal behavior analysis systems can recognize complex individual behaviors and social interactions from video recordings, and have great potential to facilitate research on psychiatric disorders, such as autism, schizophrenia, depression, substance abuse, and anxiety. In a study that analyzed spontaneous behavior, although the whole-body 3D kinematics approach analyzed individual animals’ behavior, it achieved accurate identification of behavioral phenotypes for transgenic animal models that showed autistic-like behaviors [50]. The animal group analysis systems have the advantages that they can provide more complicated features for social interaction, and it will be compelling to extend the technology to psychiatric disorders research.

In summary, the MOT-Mice system is strongly generalizable to different experimental environments, such as a large arena with occlusions or several chambers connected by a corridor that need multiple cameras to monitor the activities of animals all the time. The system provides a step forward in the noninvasive tracking of unmarked individual animals within groups and has great potential for providing insights into the patterns and mechanisms of animal social interactions.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0105201); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81925011, 92149304,31900698, 32170954, and 32100763; the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2019B030335001); The Youth Beijing Scholars Program (015), Support Project of High-level Teachers in Beijing Municipal Universities (CIT&TCD20190334); Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Big Data-based Precision Medicine, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China (PXM2021_014226_000026).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Feng Su, Yangzhen Wang, Mengping Wei, and Chong Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Peijiang Yuan, Email: itr@buaa.edu.cn.

Dong-Gen Luo, Email: dgluo@pku.edu.cn.

Chen Zhang, Email: czhang@188.com.

References

- 1.Dunbar RI, Shultz S. Evolution in the social brain. Science. 2007;317:1344–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.1145463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sallet J, Mars RB, Noonan M, Andersson JL, O’Reilly J, Jbabdi S, et al. Social network size affects neural circuits in macaques. Science. 2011;334:697–700. doi: 10.1126/science.1210027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Ami Bartal I, Decety J, Mason P. Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats. Science. 2011;334:1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.1210789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller M, Vandenberg LN, Charlier TD. The parental brain and behavior: A target for endocrine disruption. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2019;54:100765. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridges RS. Neuroendocrine regulation of maternal behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2015;36:178–196. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jager A, Maas DA, Fricke K, de Vries RB, Poelmans G, Glennon JC. Aggressive behavior in transgenic animal models: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;91:198–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manchia M, Carpiniello B, Valtorta F, Comai S. Serotonin dysfunction, aggressive behavior, and mental illness: Exploring the link using a dimensional approach. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8:961–972. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safran RJ, Levin II, Fosdick BK, McDermott MT, Semenov GA, Hund AK, et al. Using networks to connect individual-level reproductive behavior to population patterns. Trends Ecol Evol. 2019;34:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Port M, Schülke O, Ostner J. Reproductive tolerance in male primates: Old paradigms and new evidence. Evol Anthropol. 2018;27:107–120. doi: 10.1002/evan.21586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bass C, Halligan PW. Illness related deception: Social or psychiatric problem? J R Soc Med. 2007;100:81–84. doi: 10.1177/014107680710000223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene RW, Biederman J, Zerwas S, Monuteaux MC, Goring JC, Faraone SV. Psychiatric comorbidity, family dysfunction, and social impairment in referred youth with oppositional defiant disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1214–1224. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shultz S, Klin A, Jones W. Neonatal transitions in social behavior and their implications for autism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2018;22:452–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu B, Yuan B, Dai JK, Cheng TL, Xia SN, He LJ, et al. Reversal of social recognition deficit in adult mice with MECP2 duplication via normalization of MeCP2 in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Bull. 2020;36:570–584. doi: 10.1007/s12264-020-00467-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J, McCleery A, Reddy LF, Wynn JK. Social disconnection in schizophrenia and the general community. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:242–249. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-Theoduloz G, Paz V, Nicolaisen-Sobesky E, Pérez A, Buunk AP, Cabana Á, et al. Social avoidance in depression: A study using a social decision-making task. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128:234–244. doi: 10.1037/abn0000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemyre A, Gauthier-Légaré A, Bélanger RE. Shyness, social anxiety, social anxiety disorder, and substance use among normative adolescent populations: A systematic review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:230–247. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2018.1536882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romano M, Moscovitch DA, Ma RF, Huppert JD. Social problem solving in social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;68:102152. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.102152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rein B, Ma KJ, Yan Z. A standardized social preference protocol for measuring social deficits in mouse models of autism. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:3464–3477. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0382-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ariyasiri K, Choi TI, Kim OH, Hong TI, Gerlai R, Kim CH. Pharmacological (ethanol) and mutation (Sam2 KO) induced impairment of novelty preference in zebrafish quantified using a new three-chamber social choice task. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;88:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng J, Tian Y, Xu H, Gu L, Xu H. A standardized protocol for the induction of specific social fear in mice. Neurosci Bull. 2021;37:1708–1712. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00754-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan Z, Zhu H, Zhou T, Wang S, Wu Y, Hu H. Using the tube test to measure social hierarchy in mice. Nat Protoc. 2019;14:819–831. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou T, Zhu H, Fan Z, Wang F, Chen Y, Liang H, et al. History of winning remodels thalamo-PFC circuit to reinforce social dominance. Science. 2017;357:162–168. doi: 10.1126/science.aak9726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez-Marin A, Paton JJ, Kampff AR, Costa RM, Mainen ZF. Big behavioral data: Psychology, ethology and the foundations of neuroscience. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1455–1462. doi: 10.1038/nn.3812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crabbe JC, Morris RG. Festina lente: Late-night thoughts on high-throughput screening of mouse behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1175–1179. doi: 10.1038/nn1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero-Ferrero F, Bergomi MG, Hinz RC, Heras FJH, de Polavieja GG. Idtracker ai Tracking all individuals in small or large collectives of unmarked animals. Nat Methods. 2019;16:179–182. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai YX, Zhang SH, Fan Z, Liu XY, Zhao X, Feng XZ, et al. Automatic multiple zebrafish tracking based on improved HOG features. Sci Rep. 2018;8:10884. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orger MB, de Polavieja GG. Zebrafish behavior: Opportunities and challenges. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2017;40:125–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-033857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egnor SE, Branson K. Computational analysis of behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2016;39:217–236. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070815-013845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong W, Kennedy A, Burgos-Artizzu XP, Zelikowsky M, Navonne SG, Perona P, et al. Automated measurement of mouse social behaviors using depth sensing, video tracking, and machine learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E5351–E5360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515982112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pérez-Escudero A, Vicente-Page J, Hinz RC, Arganda S, de Polavieja GG. idTracker: Tracking individuals in a group by automatic identification of unmarked animals. Nat Methods. 2014;11:743–748. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolado R, Gimeno E, Beltran FS, Quera V, Pertusa JF. A method for resolving occlusions when multitracking individuals in a shoal. Behav Res Methods. 2015;47:1032–1043. doi: 10.3758/s13428-014-0520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira TD, Aldarondo DE, Willmore L, Kislin M, Wang SS, Murthy M, et al. Fast animal pose estimation using deep neural networks. Nat Methods. 2019;16:117–125. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forkosh O, Karamihalev S, Roeh S, Alon U, Anpilov S, Touma C, et al. Identity domains capture individual differences from across the behavioral repertoire. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:2023–2028. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0516-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noldus LP, Spink AJ, Tegelenbosch RA. EthoVision: A versatile video tracking system for automation of behavioral experiments. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2001;33:398–414. doi: 10.3758/BF03195394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spink A, Tegelenbosch R, Buma M, Noldus L. The EthoVision video tracking system—a tool for behavioral phenotyping of transgenic mice. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:731–744. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohayon S, Avni O, Taylor AL, Perona P, Egnor SR. Automated multi-day tracking of marked mice for the analysis of social behaviour. J Neurosci Methods. 2013;219:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shemesh Y, Sztainberg Y, Forkosh O, Shlapobersky T, Chen A, Schneidman E. High-order social interactions in groups of mice. Elife. 2013;2:e00759. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howerton CL, Garner JP, Mench JA. A system utilizing radio frequency identification (RFID) technology to monitor individual rodent behavior in complex social settings. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;209:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freund J, Brandmaier AM, Lewejohann L, Kirste I, Kritzler M, Krüger A, et al. Emergence of individuality in genetically identical mice. Science. 2013;340:756–759. doi: 10.1126/science.1235294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weissbrod A, Shapiro A, Vasserman G, Edry L, Dayan M, Yitzhaky A, et al. Automated long-term tracking and social behavioural phenotyping of animal colonies within a semi-natural environment. Nat Commun. 2018;2013:4. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavković Ž, Potrebić M, Kanazir S, Pešić V. Motivation, risk-taking and sensation seeking behavior in propofol anesthesia exposed peripubertal rats. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;96:109733. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jin X, Ji L, Chen Q, Sheng R, Ji F, Yang J. Anesthesia plus surgery in neonatal period impairs preference for social novelty in mice at the juvenile age. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;530:603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.07.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stratmann G, Lee J, Sall JW, Lee BH, Alvi RS, Shih J, et al. Effect of general anesthesia in infancy on long-term recognition memory in humans and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:2275–2287. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Branson K, Robie AA, Bender J, Perona P, Dickinson MH. High-throughput ethomics in large groups of Drosophila. Nat Methods. 2009;6:451–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Chaumont F, Coura RD, Serreau P, Cressant A, Chabout J, Granon S, et al. Computerized video analysis of social interactions in mice. Nat Methods. 2012;9:410–417. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mathis A, Mamidanna P, Cury KM, Abe T, Murthy VN, Mathis MW, et al. DeepLabCut: Markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1281–1289. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bala PC, Eisenreich BR, Yoo SBM, Hayden BY, Park HS, Zimmermann J. Automated markerless pose estimation in freely moving macaques with OpenMonkeyStudio. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4560. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18441-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pereira TD, Tabris N, Matsliah A, Turner DM, Li J, Ravindranath S, et al. SLEAP: A deep learning system for multi-animal pose tracking. Nat Methods. 2022;19:486–495. doi: 10.1038/s41592-022-01426-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marshall JD, Aldarondo DE, Dunn TW, Wang WL, Berman GJ, Ölveczky BP. Continuous whole-body 3D kinematic recordings across the rodent behavioral repertoire. Neuron. 2021;109:420–437.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang K, Han Y, Chen K, Pan H, Zhao G, Yi W, et al. A hierarchical 3D-motion learning framework for animal spontaneous behavior mapping. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2784. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22970-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han Y, Huang K, Chen K, Pan H, Ju F, Long Y, et al. MouseVenue3D: A markerless three-dimension behavioral tracking system for matching two-photon brain imaging in free-moving mice. Neurosci Bull. 2022;38:303–317. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00778-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schofield D, Nagrani A, Zisserman A, Hayashi M, Matsuzawa T, Biro D, et al. Chimpanzee face recognition from videos in the wild using deep learning. Sci Adv. 2019;5:0736. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu WQ, Camps O, Sznaier M. Multi-camera multi-object tracking. 2017: arXiv: 1709.07065. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1709.07065.

- 54.Wang X. Intelligent multi-camera video surveillance: A review. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2013;34:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2012.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]