Abstract

Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) shows excellent effects on relieving clinical symptoms in migraine patients. Nevertheless, the neurological mechanisms of taVNS for migraineurs remain unclear. In recent years, voxel-wise degree centrality (DC) and functional connectivity (FC) methods were extensively utilized for exploring alterations in patterns of FC in the resting-state brain. In the present study, thirty-five migraine patients without aura and thirty-eight healthy controls (HCs) were recruited for magnetic resonance imaging scans. Firstly, this study used voxel-wise DC analysis to explore brain regions where abnormalities were present in migraine patients. Secondly, for elucidating neurological mechanisms underlying taVNS in migraine, seed-based resting-state functional connectivity analysis was employed to the taVNS treatment group. Finally, correlation analysis was performed to explore the relationship between alterations in neurological mechanisms and clinical symptoms. Our findings indicated that migraineurs have lower DC values in the inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) and paracentral lobule than in healthy controls (HCs). In addition, migraineurs have higher DC values in the cerebellar lobule VIII and the fusiform gyrus than HCs. Moreover, after taVNS treatment (post-taVNS), patients displayed increased FC between the ITG with the inferior parietal lobule (IPL), orbitofrontal gyrus, angular gyrus, and posterior cingulate gyrus than before taVNS treatment (pre-taVNS). Besides, the post-taVNS patients showed decreased FC between the cerebellar lobule VIII with the supplementary motor area and postcentral gyrus compared with the pre-taVNS patients. The changed FC of ITG-IPL was significantly related to changes in headache intensity. Our study suggested that migraine patients without aura have altered brain connectivity patterns in several hub regions involving multisensory integration, pain perception, and cognitive function. More importantly, taVNS modulated the default mode network and the vestibular cortical network related to the dysfunctions in migraineurs. This paper provides a new perspective on the potential neurological mechanisms and therapeutic targets of taVNS for treating migraine.

Subject terms: Migraine, Sensory processing

Introduction

Migraine is defined as a severe throbbing headache accompanied by sensitivity to light and sound, decreased executive ability, memory and attention, which is persistent and has severe negative impacts on sufferers' life (e.g., marital breakdown, financial strain, health decline, etc.)1–6. According to a 2016 study on the burden of disease, migraine has become the second leading cause of disability7.

Recently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques have been employed in several migraine investigations8–11. The results revealed that migraineurs exhibited abnormalities in brain areas related to pain, including pain perception areas (e.g., cerebellum and brainstem) and nociceptive inhibition regions (e.g., periaqueductal gray)8–11. Meanwhile, migraineurs exhibited abnormalities in sensory-related areas, such as the fusiform gyrus (FFG) and insula12–15. Furthermore, other researches also reported unnormal brain regions relating to executive ability and attention in migraineurs, such as the paracentral lobule (PCL) and orbitofrontal gyrus (OFG)16–19. However, most previous researches only examined simple activation of the brain in migraine patients or performed regions of interest (ROIs) studies based on prior experience, which do not accurately reflect patterns for functional connectivity (FC) across the whole brain of migraine sufferers.

Voxel-wise degree centrality (DC) treats each voxel as an independent network node and calculates the time series correlation of each node with other voxels in the whole brain20. It has high retest reliability20. Voxels with higher DC values imply that they are located in the hub of the whole-brain network20,21. Thus, voxel-wise DC was used to construct brain functional connectomes and identify aberrant brain networks in certain diseases22–24. Specifically, DC of the cerebellum and parahippocampal gyrus was raised in elderly depressed patients compared to healthy controls (HCs); DC in the temporal lobe were found to be higher in Parkinson's patients than in HCs; brain network centrality was altered in the cerebellum and OFG of early blinded adolescents compared to normal controls22,24,25. Meanwhile, several studies have found that voxel-wise DC could reveal the differences in the brain networks between different subtypes of diseases, e.g., the late-onset and early-onset depression, Parkinson's syndrome in the presence or absence of cognitive impairment, schizophrenia responders and nonresponders22,24,26. Therefore, voxel-wise DC analysis may provide an objective and comprehensive approach to uncover specific brain FC patterns in migraine patients. Furthermore, it paves the way for further exploration of the brain mechanisms underlying transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) modulation of migraine patients.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) has demonstrated promising potential in treating migraine27–29. Migraine is a central neurological disease30–34. The vagus nerve participates in modulating a variety of bodily functions, including inflammation, mood, somatic response and pain35–40. Previous studies have demonstrated evidence of the effectiveness of VNS for treating central nervous system disorders, like epilepsy, ischemic stroke, depression, etc.41–44. Pieces of evidence have also supported the good potential of VNS in pain relief45,46. Notably, several studies have shown that VNS (both invasive and non-invasive) can be effective in relieving clinical symptoms in migraineurs29,47–49. A randomized controlled trial revealed that migraineurs in the real taVNS had reduced headache duration, headache attacks, and headache intensity compared to migraineurs in the sham taVNS47. Another study reported that chronic migraineurs had significantly decreased headache duration after 1 Hz taVNS29. A study showed that over 40% of episodic patients reported significant pain relief after cervical vagus nerve stimulation treatment50. These studies show that vagus nerve stimulation is a well-established and effective technique for treating migraine. However, the mechanisms by which vagus nerve stimulation modulates brain networks in migraineurs remain unclear.

TaVNS, developed from VNS, is painless, non-invasive, portable and easy to operate51. Sclocco and colleagues (2020) showed that 100 Hz taVNS evoked the strongest brainstem response in healthy participants compared to other stimulation frequencies (2 Hz, 10 Hz, 25 Hz)52. Another study found that 8 Hz taVNS immediately reduced activation in limbic system and increased activation in insula, precentral gyrus and thalamus in healthy participants53. An fMRI study found that taVNS at 4/20 Hz reduced regional coherence in the frontal cortex of depressed patients54. In addition, Garcia et al. found that 30 Hz exhalatory-gated taVNS enhanced the connectivity of the nucleus tractus solitarii with the anterior insula and anterior middle cingulate cortex in migraineurs55. Compared to 20 Hz taVNS, 1 Hz taVNS reduced the functional connectivity of the locus coeruleus between the insula and anterior cingulate gyrus in migraineurs and more greatly enhanced the functional connectivity of the periaqueductal gray with the insula and anterior cingulate gyrus in migraine patients56,57. The above studies shows that the brain networks in migraineurs are modulated differently by selecting different frequencies of taVNS.

However, Straube et al. found that migraineurs receiving 1 Hz taVNS had significantly fewer headache days per 4 weeks than migraineurs who received 25 Hz taVNS29. Cao et al. showed that 1 Hz taVNS modulated the functional connectivity of pain-related brain regions in migraineurs compared to 20 Hz taVNS56. Meanwhile, Zhang et al. confirmed that 1 Hz taVNS was effective in relieving clinical symptoms in migraineurs47. These studies have highlighted the potential of 1 Hz taVNS in the treatment of migraine. However, the underlying neural mechanism by which 1 Hz taVNS modulates migraineurs is unclear.

Recently, several researches have examined the brain mechanisms regulated by 1 Hz taVNS in migraineurs28,47,58. An investigation of the regions of interest discovered that significantly increasing FC of the locus coeruleus and the secondary somatosensory cortex were correlated to the frequent headache onset in migraine patients after taVNS treatment (post-taVNS) than in migraine patients before taVNS treatment (pre-taVNS)28. In addition, another study with FC analysis using the bilateral amygdala as the ROIs showed that the real taVNS modulated FC between the amygdala and the pain network than in the sham taVNS58. A recent investigation revealed that taVNS could modulate the FC between thalamus subregions and the postcentral gyrus (PoCG) in migraineurs, and the FC was strongly related to a reduction in migraine attack days47. Notably, most studies mentioned above have used the pain-related brain regions as the ROIs to uncover the neural mechanisms of taVNS modulation. However, the modulatory effect of 1 Hz taVNS on the whole-brain functional connectivity pattern at the voxel level for migraine patients has not been considered.

In this paper, we examined the brain network features of patients with migraine without aura (MwoA) at the voxel level and the modulatory effect of 1 Hz taVNS on the brain network in migraineurs. Firstly, we employed voxel-wise DC analysis to investigate specific functional brain networks in patients compared to HCs. Secondly, to further explore the underlying mechanisms by which taVNS affects patients, the current study compared the resting-state FC in the pre- and post-taVNS patients depending on the abnormal findings of voxel-wise DC. Finally, to explore the relationship between alterations in neurological function and efficacy, we performed the correlation analysis for changes in FC and changes in clinical assessment after treatment. Based on previous researches9,10,13,14, we hypothesized that an abnormal brain connectivity pattern might be displayed for MwoA patients in some pivotal regions, which are involved in multisensory information integration, nociception, and cognitive function. Finally, taVNS could alleviate the migraine symptoms and modulate the FC in these brain areas.

Participants and methods

Participants

This paper included thirty-eight healthy controls and thirty-five episodic MwoA patients. These episodic MwoA patients were screened by experienced neurologists. The diagnostic criteria were used the beta version of the International Classification of Headache, 3rd edition59. Patients were required to comply with the following standards: (a) the usual hand is the right hand; (b) age is over 18 years old; (c) symptoms of migraine have lasted more than 6 months; (d) headache attacks at least twice a month (validated by self-reports from migraineurs prior to the study); (e) patients were not taking any vasoactive or psychoactive drugs during three months before the experiment. In the meanwhile, the patients' criteria for exclusion analysis were as follows: (a) other diseases causing headaches; (b) migraine episodes within two days before the MRI scan or while the scan is in progress; (c) fetation or breastfeeding period; (d) presence of additional long-term pain conditions; (e) head shape deformity or intracranially occurring lesions; (f) contraindications to MRI; (g) Self-Rating Anxiety Scale or the Self-Rating Depression Scale scores over 50.

Thirty-eight HCs recruited through advertising. The standards for inclusion in the analysis were as follows: (a) the dominant hand is the right hand; (b) the age is over 18 years old. The standards for exclusion are as follows: (a) presence of one or more primary illnesses; (b) history of alcohol abuse or family history in hereditary mental illness; (c) contraindications to MRI; (d) pregnancy or lactation; (e) history of any vasoactive or psychotropic drugs; (f) any cranial deformities or intracranial lesions.

This research strictly followed the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine approved this research (Z2016-079-01).

Treatment procedure

The total duration of this study was 8 weeks. We observed the clinical presentation of the migraineurs during the first 4 weeks (baseline period) and instructed them to keep a headache diary. The content of diaries was as follows: headache duration, headache attacks, headache intensity (measured with Visual Analog Scale), quality of life for migraine (measured with Migraine Specific Quality-of-Life Questionnaire), depression status (measured with Self-Rating Depression Scale), and anxiety status (measured with Self-Rating Anxiety Scale). The patients were given the taVNS intervention and instructed to keep the diaries for the last four weeks (treatment period). Experienced acupuncturists treated patients with taVNS. The site of taVNS treatment was located in the left cymba concha, which has been shown to be a densely distributed area of the superficial vagus nerve60,61. The Huatuo brand electronic acupuncture treatment instrument (SDZII) was used in this study and two adjacent sites in the left cymba concha receive the taVNS stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S1). Each patient received a 4-week treatment period which included 12 sessions, with 30 min per session. Based on previous taVNS studies, patients were treated with therapy intensity of 0.2 ms and frequency setting of 1 Hz28,47,56. The intensity level of somatosensory stimulus was slowly adjusted to the strongest painless stimulus the patient could receive; HCs did not do any treatment.

Resting-state functional MRI data acquisition

Patients underwent functional and structural MRI scans before and after treatment. The time window between the MRI scan and treatment visit is one day, i.e. the pre-treatment MRI scan was completed first, and then the first treatment visit was performed on the next day; at the end of treatment, the last treatment visit was performed first, and then the post-treatment MRI scan was completed on the next day. The experiment for migraineurs is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. The HCs underwent only one scan. The same MRI scanner (Siemens MAGNETOM Verio 3.0 T, Erlangen, Germany) was used for all functional and structural MRI image scans. The scanner used a 24-channel phased-array head coil. The following parameters were employed for functional magnetic resonance imaging scans: repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, echo time (TE) = 30 ms, field of view (FOV) = 224 mm × 224 mm, matrix = 64 × 64, flip angle = 90°, slice thickness = 3.5 mm, interslice gap = 0.7 mm, 31 axial slices paralleled and 240 time points. The detailed scanning parameters of the T1-weighted high-resolution structural images are as follows: TR = 1900 ms, TE = 2.27 ms, flip angle = 9°, FOV = 256 mm × 256 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, and slice thickness = 1.0 mm. All participants have been asked to keep clear and keep their minds off specific things. We used pillows to immobilize the patients' heads and reduce head movement. Noise generated by the MRI instrument is decreased using ear plugs. Finally, participants have been instructed to maintain their eyes shut after the start of the MRI scan.

Data preprocessing

The preprocessing of the functional data was executed by the DPABI (V5.1) package using MATLAB62. The steps of preprocessing include removing the first ten time points, slice timing correction, head motion correction, normalization of the native space to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space with a final size of 3 × 3 × 3 mm3, regression of signals from white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and 24 head movement parameters, linear trend removal in time series from each voxel, and bandpass filtering (0.01–0.1 Hz). Notably, in the voxel-wise DC analysis, spatial smoothing using the 4-mm full width at a half-maximum Gaussian Kernel was performed after the DC calculation. Specifically, spatial smoothing with the same criteria used in DC was performed after the bandpass in the seed-based analysis.

Voxel-wise DC analysis for MwoA patients and HCs

We used the DPABI package to perform voxel-wise DC calculations by taking each voxel as a node. Specifically, the time course of each voxel was extracted first. Subsequently, we calculated each voxel’s Pearson correlation coefficient (r) of the time course between each voxel and all the other voxels. Finally, the threshold of the obtained Pearson correlation coefficient matrix was set to r > 0.258,24,25,63. In the present research, we used binary DC values24,64. To improve the normalization of the data, this research transformed the correlation coefficients to z-scores using Fisher's r-to-z transformation.

Seed-based FC analysis for patients before treatment and after treatment

We used the DPABI package to perform FC analysis. Here, this section analyzed the modulatory effects on brain function for patients by taVNS. Firstly, the brain regions where the clusters with increased or decreased DC values were displayed in migraineurs compared to HCs were defined as ROIs. Secondly, to obtain functional connectivity maps for the pre-taVNS and post-taVNS patients, this research calculated the correlation of time series of functional connectivity between each ROI and other voxels of the brain for the patients. Notably, we employed Fisher's r-to-z transformation to increase the normalization of the correlation coefficient.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical assessment information

This research tested differences in demographics and clinical assessments using SPSS 26.0. Normality tests were first performed on continuous data. The Mann–Whitney U-test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and paired samples t-test were performed on the demographic data and clinical assessment data, respectively. The chi-square test was adopted to examine differences between genders.

Degree centrality, functional connectivity

The DPABI toolbox was adopted to analyze the obtained DC and FC between groups. Independent samples t-test was performed to analyze the alteration of DC values in the pre-taVNS patients and the HCs groups with age, gender, and head motions as covariates. These comparisons were used to find brain areas that differed in the patients and the HCs. Here, the gaussian random field (GRF) correction was employed for correcting multiple comparisons (voxel p < 0.005, cluster p < 0.05)8,65,66. In the taVNS groups, we employed a paired samples t-test for analyzing differences in brain FC maps in migraineurs after the treatment, with head motions as a covariate. The results have also used the GRF correction (voxel p < 0.005, cluster p < 0.05). Furthermore, for measuring the correlation between the alterations in clinical indicators (headache duration, headache attacks, headache intensity, anxiety status, depression status, and quality of life) and the alterations in brain functional connectivity in the post-taVNS patients, we employed the Pearson correlation analysis in this study.

Institutional review board statement

The Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine approved this research.

Informed consent statement

This research strictly followed the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants mentioned above have informed and consented.

Results

Demographic and clinical features in migraine patients and healthy controls

The results of population statistics and clinical data are presented in Table 1. Migraineurs have a range of 1–10 headache attacks during the baseline period, and have a range of 0–10 headache attacks during the treatment period. Gender was analyzed as a categorical variable using the chi-square test, which revealed no statistical difference in gender between patients and healthy controls. Age, headache duration, headache attacks, headache intensity, depression status, and quality of life were non-normality data after the normality tests, and anxiety status were normality data. The Mann–Whitney U-test indicated that there was no statistically significant difference in age between the migraineurs and the healthy controls. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed that headache duration, headache attacks, headache intensity, depressed status, and quality of life were significantly improved in the post-taVNS patients compared to the pre-taVNS patients. Paired samples t-test suggested that patients had a significantly lower anxiety status after treatment.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics. The p-values for gender were obtained using chi-square tests for patients with migraines without aura group and the healthy controls. The p-values for age were obtained using Mann–Whitney U Tests for the MwoA patients and HCs. The p-values for the anxiety status were obtained using paired samples t-test for the pre- and post-taVNS patients. The p-values for the headache duration, headache attacks, headache intensity, depression status, and quality of life were obtained using Wilcoxon signed rank tests for the pre- and post-taVNS patients. SD standard deviation, MwoA migraine without aura, HCs healthy controls, taVNS transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, post-taVNS after taVNS treatment, pre-taVNS before taVNS treatment; a, chi-square test; b, Mann–Whitney U Tests; c, Wilcoxon signed rank tests; d, paired samples t-test.

| Characteristics | MwoA | HCs | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 10/25 | 14/24 | 0.45a | |

| Age | 31.97 ± 6.78 | 32.00 ± 11.16 | 0.16b | |

| pre-taVNS | post-taVNS | |||

| Headache intensity (mean ± SD) | 48.14 ± 17.13 | 27.71 ± 20.78 | < 0.001c | |

| Anxiety status (mean ± SD) | 39.55 ± 5.56 | 36.93 ± 6.39 | 0.002d | |

| Depression status (mean ± SD) | 41.54 ± 5.23 | 38.32 ± 5.58 | < 0.001c | |

| Quality of life for migraine (mean ± SD) | 60.40 ± 9.99 | 72.45 ± 8.89 | < 0.001c | |

| Headache duration (h) (mean ± SD) | 53.22 ± 49.19 | 30.91 ± 45.71 | < 0.001c | |

| Headache attacks (mean ± SD) | 3.89 ± 2.30 | 2.69 ± 2.31 | 0.009c | |

Pre-taVNS vs HCs

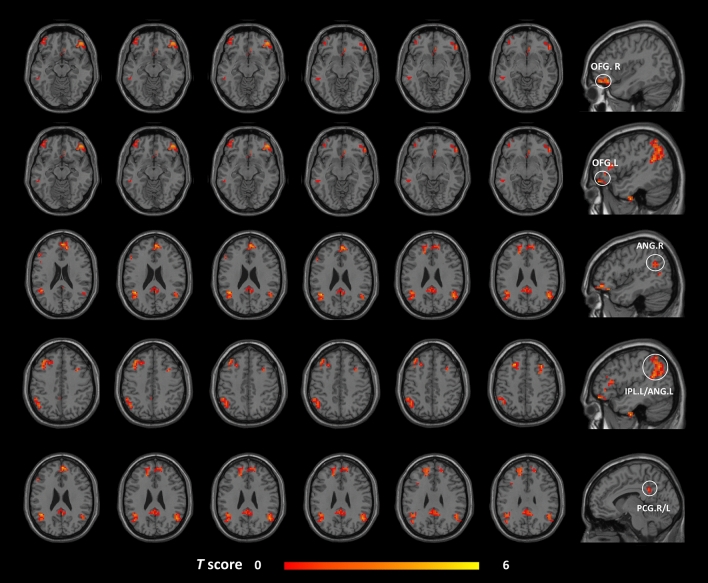

Voxel-wise DC analysis showed that the pre-taVNS patients had increased DC values at the right cerebellar lobule VIII and the right fusiform gyrus (FFG) compared to the HCs (Table 2, Fig. 1). In the meantime, the pre-taVNS patients had reduced DC values at the right inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) and the left paracentral lobule (PCL) than in HCs (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Brain regions with different DC values between MwoA patients and HCs (GRF corrected, voxel p < 0.005, cluster p < 0.05). DC degree centrality, MwoA migraine without aura, HCs healthy controls, GRF Gaussian random field, AAL automated anatomical labeling, MNI Montreal Neurological Institute, FFG fusiform gyrus, ITG inferior temporal gyrus, PCL paracentral gyrus, R right, L left.

| Cluster size | Brain region (AAL name) | MNI coordinates | Peak intensity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| 74 | FFG.R | 33 | − 57 | − 9 | 4.42 |

| 89 | Cerebellar lobule VIII.R | 21 | − 63 | − 48 | 3.78 |

| 70 | ITG.R | 57 | − 12 | − 42 | − 5.01 |

| 88 | PCL.L | − 9 | − 45 | 75 | − 4.22 |

Figure 1.

Brain regions exhibiting differences in voxel-wise DC between the MwoA patients and the HCs (GRF corrected, voxel p < 0.005, cluster p < 0.05). The color bar represents the t-score. Warm color represents regions with higher DC values in the patients compared to HCs; Cool color represents areas with lower DC values in the patients compared to HCs. DC degree centrality, MwoA migraine without aura, HCs healthy controls, GRF Gaussian random field, FFG fusiform gyrus, ITG inferior temporal gyrus, PCL paracentral lobule, R right, L left.

Pre-taVNS vs post-taVNS

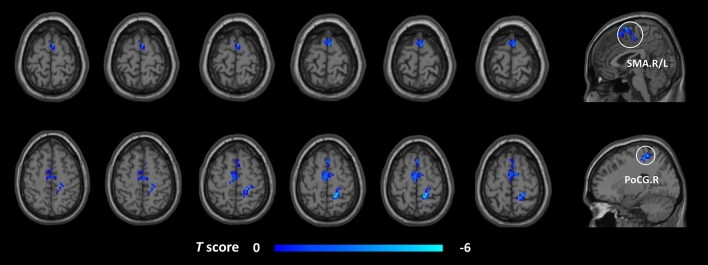

In the FC analysis, we used the right cerebellar lobule VIII, right FFG, right ITG, and left PCL as ROIs to analyze the changes in the whole-brain FC in these brain regions in the post-taVNS patients. Compared to the pre-taVNS patients, the post-taVNS patients had enhanced FC in the right ITG with the bilateral orbitofrontal gyrus (OFG), bilateral angular gyrus (ANG), left inferior parietal lobule (IPL), and bilateral posterior cingulate gyrus (PCG) (Table 3; Fig. 2). Meanwhile, compared to the pre-taVNS patients, the post-taVNS patients had reduced FC of the right cerebellar lobule VIII with the bilateral supplementary motor area (SMA) and right PoCG (Table 4; Fig. 3). The correlation analysis revealed that the changed FC of ITG-IPL was significantly and positively correlated with the changes in headache intensity.

Table 3.

Brain regions showing altered FC with the ITG in the post-taVNS patients compared to the pre-taVNS patients (GRF corrected, voxel p < 0.005, cluster p < 0.05). FC functional connectivity, ITG inferior temporal gyrus, taVNS transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, post-taVNS after taVNS treatment, pre-taVNS before taVNS treatment, GRF Gaussian random field, AAL automated anatomical labeling, MNI Montreal Neurological Institute, OFG orbitofrontal gyrus, ANG angular gyrus, IPL inferior parietal lobule, PCG posterior cingulate gyrus, L left, R right.

| Cluster size | Brain region (AAL name) | MNI coordinates | Peak intensity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| 79 | OFG.R | 36 | 33 | − 18 | 4.85 |

| 28 | OFG.L | − 39 | 21 | 12 | 4.61 |

| 52 | ANG.R | 51 | − 60 | 27 | 4.44 |

| 99 | ANG.L /IPL.L | − 42 | − 51 | 24 | 4.73 |

| 33 | PCG.R/L | − 6 | − 42 | 36 | 3.92 |

Figure 2.

Brain regions showing increased seed-based FC between the post- and pre-taVNS patients (GRF corrected, voxel p < 0.005, cluster p < 0.05). The warm color bar represents areas where the FC of the post-taVNS patients is greater than the pre-taVNS patients; FC functional connectivity, taVNS transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, post-taVNS after taVNS treatment, pre-taVNS before taVNS treatment, MwoA migraine without aura, GRF Gaussian random field, OFG orbitofrontal gyrus, ANG angular gyrus, IPL inferior parietal lobule, PCG posterior cingulate gyrus, R right, L left.

Table 4.

Brain areas indicating changed FC with the cerebellar lobule VIII in the post-taVNS patients compared to the pre-taVNS patients (GRF corrected, voxel p < 0.005, cluster p < 0.05). FC functional connectivity, taVNS transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, post-taVNS after taVNS treatment, pre-taVNS before taVNS treatment, GRF Gaussian random field, AAL automated anatomical labeling, MNI Montreal Neurological Institute, SMA supplementary motor area, PoCG postcentral gyrus, L left, R right.

| Cluster size | Brain region (AAL name) | MNI coordinates | Peak intensity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||

| 200 | SMA.R/L | 3 | 3 | 69 | − 4.10 |

| 33 | PoCG.R | 18 | − 39 | 60 | − 5.10 |

Figure 3.

Brain regions indicating reduced seed-based FC between the post- and pre-taVNS patients (GRF corrected, voxel p < 0.005, cluster p < 0.05). The cool color bar represents areas where the FC of the post-taVNS patients is smaller than the pre-taVNS patients. FC functional connectivity, taVNS transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, post-taVNS after taVNS treatment, pre-taVNS before taVNS treatment, MwoA migraine without aura, GRF Gaussian random field, SMA supplementary motor area, PoCG postcentral gyrus, R right, L left.

Discussion

A study has suggested that the neural mechanisms of episodic migraine were different to chronic migraine67. However, our study focused on patients with episodic migraine without aura. This research first examined specific brain network patterns in episodic migraineurs without aura than in the HCs with a DC method at the voxel level. Using the areas that had alterations in DC values of the pre-taVNS patients compared to the HCs, we performed whole-brain FC analysis to test whether the taVNS could modulate the neural mechanisms underlying the patients before and after treatments. We found increased DC of FFG and cerebellar lobule VIII, and decreased DC of ITG and PCL in the pre-taVNS patients than HCs. Previous studies have shown that taVNS can modulate brainstem regions in migraine patients55. However, our study focused on abnormal brain networks in migraineurs compared with HCs and explored the modulation of these abnormal brain networks by taVNS. Our study showed that compared with the pre-taVNS patients, taVNS can significantly modulate the FC of these specific brain regions in migraineurs. Headache duration, headache attacks, and headache intensity were significantly reduced in patients after treatment. Finally, we discovered a correlation between the changes in FC of the ITG-IPL and the changes in headache intensity in the patients.

Altered brain connectivity in MwoA patients than healthy controls

We found elevated DC values of the FFG, cerebellar lobule VIII, and reduced DC values of the ITG in the patients than in the HCs. It suggested that alterations in central locations of the brain network in these brain regions are associated with migraine. The FFG is an important part of higher visual function and participates in injurious/anti-injurious sensory processing68–70. In agreement with our study, previous researches have demonstrated that FFG is abnormally altered in migraineurs compared to HCs, including reduced cortical thickness and decreased amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF)13,71. The cerebellum is a multi-modal region involved in integrated sensory information processing, pain processing, and motor control72–74. The finding in our paper is consistent with other earlier studies9,13. To be specific, a functional MRI (fMRI) study has shown that ALFF and fractional ALFF in the cerebellum were significantly reduced in migraineurs compared to HCs13. A hemodynamic investigation of migraine patients showed ischemic lesions in the cerebellar lobes9. The ITG is a multisensory information integration brain region associated with visual perception8,75,76. An MRI study on migraine indicated an increased FC of ITG and lingual gyrus in migraineurs than in HCs77. The FFG and ITG belong to the visual cortex, and they are adjacent to the anatomical location of the cerebellum68,78. Migraine sufferers experienced sensory hypersensitivity, including abnormal multisensory integration, both during and between headache attacks79–81. Visual and auditory stimuli could enhance the intensity of headaches in migraineurs82. Compared to non-migraineurs, migraineurs are hyper-aware of everyday sounds (car horns, bells), which could cause migraine attacks83–85. Therefore, altered DC values in the FFG, ITG and cerebellar lobule VIII might suggest aberrant multisensory integration and pain perception in MwoA patients.

In addition, the pre-taVNS patients had reduced DC values in the PCL compared to HCs. This finding suggested an association between altered brain connectivity in PCL and migraine. The PCL is primarily associated with memory and attentional functions86–88. The majority of migraineurs have exhibited abnormal cognitive functions in certain brain regions1,2. Compared to normal individuals, migraineurs had decreased sustained attention89. In the word recall experiment, migraineurs had lower memory scores than the HCs1,2,89. Additionally, prolonged migraine headaches might impair cognitive ability90. Compared to the HCs, migraineurs had lower scores on the Montreal Cognitive Scale2,89. Consistent with our study, a previous retrospective fMRI study found altered PCL cortex thickness in childhood migraineurs14. Thus, the altered brain connectivity in the PCL might be related to cognitive impairment in MwoA patients.

Behavioral and neural modulation effects of the taVNS treatments for MwoA patients

Clinical symptoms

We found that taVNS significantly alleviated headache and concomitant symptoms in the post-taVNS patients. In other words, it mainly reduced headache intensity, headache attacks, and headache duration. These results aligned with previous studies27,29,47. Zhang et al. found a significant reduction in headache symptoms in migraineurs after taVNS treatment47. Other research discovered that taVNS of 1 Hz could reduce the days of the migraine attack in chronic migraineurs compared to 25 Hz29. Therefore, we believe that taVNS is promising for treating migraine.

Altered FC of the ITG in the post-taVNS MwoA patients

In this study, the taVNS significantly modulated the FC of the temporal lobe in patients following treatments. The FC of the ITG with the ANG, IPL, PCG, and OFG were enhanced in the post-taVNS patients compared to the pre-taVNS patients. The ITG is connected to the ANG by the arcuate fasciculus76. The ITG, ANG, PCG, and IPL are included in the default mode network (DMN)91,92. When it comes to pain processing, the DMN is crucial93. In the studies of pain disorders, it has been proved that the DMN may be involved in multiple chronic pain disorders94–97. Similar to our study, previous researches revealed altered FC within the DMN of migraineurs8,98. The IPL, including the ANG, is regarded as a hub for information transmission and integration99. Numerous investigations have revealed that IPL is associated with a wide variety of cognitive impairments100–102. Meanwhile, several studies have found altered FC of the IPL in migraineurs than in healthy controls103–105. The PCG is also thought to be involved in transmitting and integrating information106. A study proved that cortical thickness of PCG in treated migraine patients was negatively associated with improvements in headache index107. It has been proposed that migraine affects the nervous system mainly in terms of sensory information transmission and integration; in other words, migraine may be a disorder with altered multisensory integration108. For example, the perception of normal touch, sound, smell and light is amplified in migraineurs109. Meanwhile, hyper-perception may lead to headaches or worsen headaches' intensity83–85. As a result, altered FC between the ITG with the ANG, PCG, and IPL in post-taVNS patients may indicate that the DMN might be involved in the modulatory effect of taVNS on MwoA patients. TaVNS might be able to modulate abnormal multisensory (light, sound, pain perception) information integration and transmission on migraineurs.

The OFG is a brain region closely related to cognitive and executive functions110. Migraineurs have significantly high cerebral blood flow in OFG than in HCs111. Most migraineurs struggle with executive function or decision-making112,113. Compared to the HCs, migraineurs showed executive dysfunction related to headache duration and intensity114. Therefore, the post-taVNS patients with enhanced FC of the ITG and OFG indicated that taVNS might regulate the connectivity in these brain regions related to multisensory information processing and executive functions in MwoA patients.

In addition, the changed FC of the ITG and IPL was significantly correlated to changes in headache intensity. We supposed that symptomatic clinical remissions in post-taVNS patients might be explained by FC changes in the ITG and IPL.

Altered FC of the posterior cerebellar lobes in MwoA patients after taVNS treatments

Our study indicated that the cerebellum of patients after taVNS has fewer functional connectivity to SMA and PoCG. The cerebellum, SMA, and PoCG are part of the vestibular cortical network (VCN)115. The vestibular cortical network involves motor balance and spatial navigation116. Abnormal activation of the VCN is found in migraine patients compared to HCs105. Follow-up of migraineurs shows that they often feel persistent vertigo, affecting their quality of life117. Vertigo symptoms in migraine patients may persist throughout the illness118,119. Regarding neural projections, the SMA receives fibre projections from the cerebellum120. Several pain-related studies have identified abnormal alterations in the SMA121,122. PoCG is involved in identifying pain information123. Meanwhile, the PoCG is the primary somatosensory cortex that regulates the corresponding behaviors based on sensory information124. Moreover, the FC of the PoCG was altered in resting-state fMRI investigations of migraine8,27,125. Thus, taVNS might participate in modulating the intrinsic connectivity within the VCN of MwoA patients, which is a brain network associated with homeostasis. Meanwhile, taVNS may modulate the brain functional connectivity patterns associated with the pain of MwoA patients.

Limitations

A few limitations are associated with this research. First of all, our study lacked an additional control group (migraineurs undergoing shame treatment or healthy subjects undergoing real treatment). On the one hand, our experiment was conducted in the hospital, which has a high mobility of healthy participants who are unwilling to participate in long-term experimental tasks. On the other hand, many migraineurs have feelings of anxiety or depression, they are unwilling to undertake additional experimental tasks. In addition, we have only studied the short-term effects of taVNS on migraineurs in the present study. However, some studies have also considered the long-time effect of taVNS126,127. For future research, it should be considered to investigate the long-term effects of taVNS in migraineurs. Finally, gender differences were not considered in our fMRI study. An epidemiological study revealed that women get migraines at considerably greater rates than males do128. Exploring the effects of taVNS on gender-specific migraine patients is an interesting idea that we will explore further in a subsequent study.

Conclusion

Our research suggested that MwoA patients have altered brain connectivity patterns in several hub regions, including ITG, FFG, cerebellar lobule VIII, and PCG, which are related to multisensory integration, pain perception, and cognitive function. Meanwhile, we found that taVNS significantly modulates the specific functional brain networks in MwoA patients, such as the default mode network and the vestibular cortical network. The discoveries in this research might help provide insight into the neurological mechanics of migraine and provide some evidence to explore neural therapeutic targets of taVNS against migraine.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the following funding bodies: the General Project of Humanities and Social Science Research, Ministry of Education (Grant Number: 22YJC190013), the Philosophy and Social Science Project of Guangdong Province (Grant Number: GD20YXL01), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant Number: 2020A1515110737), the Project of Guangzhou Philosophies and Social Sciences (Grant Number: 2020GZQN43), the Humanities and Social Sciences Project of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (Grant Number: 2020SKYB07), the Philosophy and Social Science Innovation Team Project of Guangdong Department of Education (Grant Number: 2022WCXTD004), and the Project of Guangzhou Philosophy and Social Science (Grant Number: 2022GZGJ177).

Author contributions

J.B.L., Y.Y.R., W.T.L., and L.J.M. designed the study. Q.W.L., C.Y.K., B.Q.J., and H.Y.H. conducted data collection. J.B.L., L.J.M., Y.Y.R., and W.T.L. performed data analyses and interpretation. J.B.L., Y.Y.R., W.T.L., and L.J.M. drafted the manuscript. J.B.L., Y.Y.R., W.T.L., C.Y.K., Q.W.L., H.Y.H., B.Q.J., and L.J.M. provided critical revisions. Y.P.Z., Y.Y.R., and J.B.L. provided revisions to the revised manuscript, participated in the writing of the revised manuscript, collated references to the revised manuscript, corrected grammatical errors, prepared supplementary figures for the article, and participated in responding to reviewers' comments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yuyang Rao and Wenting Liu.

Contributor Information

Lijun Ma, Email: malj@gzucm.edu.cn.

Jiabao Lin, Email: jiabaolingzucm@163.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-36437-1.

References

- 1.Vuralli D, Ayata C, Bolay H. Cognitive dysfunction and migraine. J. Headache Pain. 2018;19:109. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latysheva NV, Filatova EG, Osipova DV. Memory and attention deficit in migraine: Overlooked symptoms. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2019;119:39–43. doi: 10.17116/jnevro201911902139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashina M, Katsarava Z, Do TP, Buse DC, Pozo-Rosich P, Özge A, Krymchantowski AV, Lebedeva ER, Ravishankar K, Yu S, et al. Migraine: Epidemiology and systems of care. Lancet. 2021;397:1485–1495. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leonardi M, Raggi A. A narrative review on the burden of migraine: When the burden is the impact on people's life. J. Headache Pain. 2019;20:41. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-0993-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buse, D.C., Scher, A.I., Dodick, D.W., Reed, M.L., Fanning, K.M., Manack Adams, A., Lipton, R.B. Impact of migraine on the family: Perspectives of people with migraine and their spouse/domestic partner in the CaMEO study. Mayo Clin Proc. (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML, Murray S, Dumas PK, Adams AM, Lipton RB. Life with migraine: effects on relationships, career, and finances from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache. 2019;59:1286–1299. doi: 10.1111/head.13613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abdulkader RS, Abdulle AM, Abebo TA, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ke J, Yu Y, Zhang X, Su Y, Wang X, Hu S, Dai H, Hu C, Zhao H, Dai L. Functional alterations in the posterior insula and cerebellum in migraine without aura: A resting-state MRI study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2020;14:567588. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2020.567588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerwig M, Rauschen L, Gaul C, Katsarava Z, Timmann D. Subclinical cerebellar dysfunction in patients with migraine: Evidence from eyeblink conditioning. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:904–913. doi: 10.1177/0333102414523844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, Chen X, Liu M, Liu S, Ma L, Yu S. Disrupted functional connectivity of periaqueductal gray subregions in episodic migraine. J. Headache Pain. 2017;18:36. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0747-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin Z, He XW, Zhang J, Xu S, Li GF, Su J, Shi YH, Ban S, Hu Y, Liu YS, et al. Structural changes of cerebellum and brainstem in migraine without aura. J. Headache Pain. 2019;20:93. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1045-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui W, Zhang J, Xu F, Zhi H, Li H, Li B, Zhang S, Peng W, Wu H. MRI evaluation of the relationship between abnormalities in vision-related brain networks and quality of life in patients with migraine without aura. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021;17:3569–3579. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S341667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang JJ, Chen X, Sah SK, Zeng C, Li YM, Li N, Liu MQ, Du SL. Amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) and fractional ALFF in migraine patients: A resting-state functional MRI study. Clin. Radiol. 2016;71:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guarnera A, Bottino F, Napolitano A, Sforza G, Cappa M, Chioma L, Pasquini L, Rossi-Espagnet MC, Lucignani G, Figa-Talamanca L, et al. Early alterations of cortical thickness and gyrification in migraine without aura: A retrospective MRI study in pediatric patients. J. Headache Pain. 2021;22:79. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01290-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borsook D, Veggeberg R, Erpelding N, Borra R, Linnman C, Burstein R, Becerra L. The insula: A "Hub of Activity" in migraine. Neuroscientist. 2016;22:632–652. doi: 10.1177/1073858415601369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei M, Zhang J. Brain function state in different phases and its relationship with clinical symptoms of migraine: An fMRI study based on regional homogeneity (ReHo) Ann. Transl. Med. 2021;9:928. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baksa D, Szabo E, Kocsel N, Galambos A, Edes AE, Pap D, Zsombok T, Magyar M, Gecse K, Dobos D, et al. Circadian variation of migraine attack onset affects fmri brain response to fearful faces. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022;16:842426. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.842426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soheili-Nezhad S, Sedghi A, Schweser F, Babaki ES, A., Jahanshad, N., Thompson, P.M., Beckmann, C.F., Sprooten, E., Toghae, M. Structural and functional reorganization of the brain in migraine without aura. Front. Neurol. 2019;10:442. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin Z, Su J, He XW, Ban S, Zhu Q, Cui Y, Zhang J, Hu Y, Liu YS, Zhao R, et al. Disrupted functional connectivity between sub-regions in the sensorimotor areas and cortex in migraine without aura. J. Headache Pain. 2020;21:47. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01118-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuo XN, Ehmke R, Mennes M, Imperati D, Castellanos FX, Sporns O, Milham MP. Network centrality in the human functional connectome. Cereb. Cortex. 2012;22:1862–1875. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valdes-Sosa PA, Wu G-R, Stramaglia S, Chen H, Liao W, Marinazzo D. Mapping the voxel-wise effective connectome in resting state fMRI. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Gong H, Xu H, Ding Q, He N, Huang Y, Jin Y, Zhang C, Voon V, Sun B, et al. Abnormal voxel-wise degree centrality in patients with late-life depression: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;10:1024. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong J, Yu C, Su T, Ge QM, Shi WQ, Tang LY, Shu HY, Pan YC, Liang RB, Li QY, et al. Altered brain network centrality in patients with mild cognitive impairment: An fMRI study using a voxel-wise degree centrality approach. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:15491–15500. doi: 10.18632/aging.203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li MG, Bian XB, Zhang J, Wang ZF, Ma L. Aberrant voxel-based degree centrality in Parkinson's disease patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci. Lett. 2021;741:135507. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen Z, Kang Y, Zhang Y, Yang H, Xie B. Alteration of degree centrality in adolescents with early blindness. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022;16:935642. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.935642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Jiang Y, Su W, Xu L, Wei Y, Tang Y, Zhang T, Tang X, Hu Y, Cui H, et al. Temporal dynamics in degree centrality of brain functional connectome in first-episode schizophrenia with different short-term treatment responses: A longitudinal study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021;17:1505–1516. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S305117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng M, Zhang Y, Wen Z, Hou X, Ye Y, Fu C, Luo W, Liu B. Early fractional amplitude of low frequency fluctuation can predict the efficacy of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation treatment for migraine without aura. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022;15:778139. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.778139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Liu B, Li H, Yan Z, Liu X, Cao J, Park J, Wilson G, Liu B, Kong J. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation at 1Hz modulates locus coeruleus activity and resting state functional connectivity in patients with migraine: An fMRI study. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;24:101971. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straube A, Ellrich J, Eren O, Blum B, Ruscheweyh R. Treatment of chronic migraine with transcutaneous stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagal nerve (auricular t-VNS): A randomized, monocentric clinical trial. J. Headache Pain. 2015;16:543. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0543-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kruit MC, van Buchem MA, Hofman PA, Bakkers JT, Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD, Launer LJ. Migraine as a risk factor for subclinical brain lesions. JAMA. 2004;291:427–434. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amin FM, Asghar MS, Hougaard A, Hansen AE, Larsen VA, de Koning PJH, Larsson HBW, Olesen J, Ashina M. Magnetic resonance angiography of intracranial and extracranial arteries in patients with spontaneous migraine without aura: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:454–461. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70067-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai KL, Niddam DM. Brain metabolism and structure in chronic migraine. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2020;24:69. doi: 10.1007/s11916-020-00903-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charles A. The pathophysiology of migraine: Implications for clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:174–182. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Messina R, Filippi M, Goadsby PJ. Recent advances in headache neuroimaging. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2018;31:379–385. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan H, Silberstein SD. Vagus nerve and vagus nerve stimulation, a comprehensive review: Part III. Headache. 2016;56:479–490. doi: 10.1111/head.12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan H, Silberstein SD. Vagus nerve and vagus nerve stimulation, a comprehensive review: Part I. Headache. 2016;56:71–78. doi: 10.1111/head.12647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foreman RD, Garrett KM, Blair RW. Mechanisms of cardiac pain. Compr. Physiol. 2015;5:929–960. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonaz B, Sinniger V, Pellissier S. Vagal tone: Effects on sensitivity, motility, and inflammation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016;28:455–462. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serhan CN, de la Rosa X, Jouvene C. Novel mediators and mechanisms in the resolution of infectious inflammation: Evidence for vagus regulation. J. Intern. Med. 2019;286:240–258. doi: 10.1111/joim.12871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farmer AD, Albusoda A, Amarasinghe G, Ruffle JK, Fitzke HE, Idrees R, Fried R, Brock C, Aziz Q. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation prevents the development of, and reverses, established oesophageal pain hypersensitivity. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;52:988–996. doi: 10.1111/apt.15869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez-Carbonell L, Faulkner H, Higgins S, Koutroumanidis M, Leschziner G. Vagus nerve stimulation for drug-resistant epilepsy. Pract. Neurol. 2020;20:189–198. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2019-002210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez HFJ, Yengo-Kahn A, Englot DJ. Vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2019;30:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Senova S, Rabu C, Beaumont S, Michel V, Palfi S, Mallet L, Domenech P. Vagus nerve stimulation and depression. Press. Med. 2019;48:1507–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2019.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dibue M, Greco T, Spoor JKH, Tahir Z, Specchio N, Hanggi D, Steiger HJ, Kamp MA. Vagus nerve stimulation in patients with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome: A meta-analysis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2021;143:497–508. doi: 10.1111/ane.13375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Courties A, Berenbaum F, Sellam J. Vagus nerve stimulation in musculoskeletal diseases. Jt. Bone Spine. 2021;88:105149. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2021.105149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi, X., Hu, Y., Zhang, B., Li, W., Chen, J.D., Liu, F. Ameliorating effects and mechanisms of transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation on abdominal pain and constipation. JCI Insight.6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Zhang Y, Huang Y, Li H, Yan Z, Zhang Y, Liu X, Hou X, Chen W, Tu Y, Hodges S, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) for migraine: An fMRI study. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2021;46:145–150. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2020-102088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinfe TM, Pintea B, Muhammad S, Zaremba S, Roeske S, Simon BJ, Vatter H. Cervical non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for preventive and acute treatment of episodic and chronic migraine and migraine-associated sleep disturbance: A prospective observational cohort study. J. Headache Pain. 2015;16:101. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0582-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grazzi L, Egeo G, Liebler E, Padovan AM, Barbanti P. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) as symptomatic treatment of migraine in young patients: A preliminary safety study. Neurol. Sci. 2017;38:197–199. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-2942-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tassorelli C, Grazzi L, de Tommaso M, Pierangeli G, Martelletti P, Rainero I, Dorlas S, Geppetti P, Ambrosini A, Sarchielli P, et al. Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation as acute therapy for migraine: The randomized PRESTO study. Neurology. 2018;91:e364–e373. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Li SY, Wang D, Wu MZ, He JK, Zhang JL, Zhao B, Hou LW, Wang JY, Wang L, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation: From concept to application. Neurosci. Bull. 2021;37:853–862. doi: 10.1007/s12264-020-00619-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sclocco R, Garcia RG, Kettner NW, Fisher HP, Isenburg K, Makarovsky M, Stowell JA, Goldstein J, Barbieri R, Napadow V. Stimulus frequency modulates brainstem response to respiratory-gated transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2020;13:970–978. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kraus T, Hosl K, Kiess O, Schanze A, Kornhuber J, Forster C. BOLD fMRI deactivation of limbic and temporal brain structures and mood enhancing effect by transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna). 2007;114:1485–1493. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0755-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma Y, Wang Z, He J, Sun J, Guo C, Du Z, Chen L, Luo Y, Gao D, Hong Y, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve immediate stimulation treatment for treatment-resistant depression: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Front. Neurol. 2022;13:931838. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.931838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia RG, Lin RL, Lee J, Kim J, Barbieri R, Sclocco R, Wasan AD, Edwards RR, Rosen BR, Hadjikhani N, et al. Modulation of brainstem activity and connectivity by respiratory-gated auricular vagal afferent nerve stimulation in migraine patients. Pain. 2017;158:1461–1472. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cao J, Zhang Y, Li H, Yan Z, Liu X, Hou X, Chen W, Hodges S, Kong J, Liu B. Different modulation effects of 1 Hz and 20 Hz transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on the functional connectivity of the periaqueductal gray in patients with migraine. J. Transl. Med. 2021;19:354. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-03024-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sacca V, Zhang Y, Cao J, Li H, Yan Z, Ye Y, Hou X, McDonald CM, Todorova N, Kong J, et al. Evaluation of the modulation effects evoked by different transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation frequencies along the central vagus nerve pathway in migraines: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuromodulation. 2022;26:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.neurom.2022.08.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luo W, Zhang Y, Yan Z, Liu X, Hou X, Chen W, Ye Y, Li H, Liu B. The instant effects of continuous transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation at acupoints on the functional connectivity of amygdala in migraine without aura: A preliminary study. Neural. Plast. 2020;2020:8870589. doi: 10.1155/2020/8870589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache, S., The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia.33. 629–808 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Henry TR. Therapeutic mechanisms of vagus nerve stimulation. Neurology. 2002;59:S3–14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.59.6_suppl_4.S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peuker ET, Filler TJ. The nerve supply of the human auricle. Clin. Anat. 2002;15:35–37. doi: 10.1002/ca.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yan CG, Zang YF. DPARSF: A MATLAB toolbox for "pipeline" data analysis of resting-state fMRI. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2010;4:13. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin J, Chen Y, Xie J, Mo L. Altered brain connectivity patterns of individual differences in insightful problem solving. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022;16:905806. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.905806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeng M, Yu M, Qi G, Zhang S, Ma J, Hu Q, Zhang J, Li H, Wu H, Xu J. Concurrent alterations of white matter microstructure and functional activities in medication-free major depressive disorder. Brain Imaging Behav. 2021;15:2159–2167. doi: 10.1007/s11682-020-00411-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu W, Yue Q, Gong Q, Zhou D, Wu X. Regional and remote connectivity patterns in focal extratemporal lobe epilepsy. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021;9:1128. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang W, Lv Z, Pang X, Nie L, Zheng J. The local neural markers of MRI in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy presenting ictal panic: A resting resting-state postictal fMRI study. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;129:108490. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gomez-Pilar J, Garcia-Azorin D, Gomez-Lopez-de-San-Roman C, Guerrero AL, Hornero R. Exploring EEG spectral patterns in episodic and chronic migraine during the interictal state: Determining frequencies of interest in the resting state. Pain Med. 2020;21:3530–3538. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weiner KS, Zilles K. The anatomical and functional specialization of the fusiform gyrus. Neuropsychologia. 2016;83:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glass JM, Williams DA, Fernandez-Sanchez ML, Kairys A, Barjola P, Heitzeg MM, Clauw DJ, Schmidt-Wilcke T. Executive function in chronic pain patients and healthy controls: Different cortical activation during response inhibition in fibromyalgia. J. Pain. 2011;12:1219–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bonanno L, Lo Buono V, De Salvo S, Ruvolo C, Torre V, Bramanti P, Marino S, Corallo F. Brain morphologic abnormalities in migraine patients: An observational study. J. Headache Pain. 2020;21:39. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01109-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petrusic I, Dakovic M, Kacar K, Zidverc-Trajkovic J. Migraine with aura: Surface-based analysis of the cerebral cortex with magnetic resonance imaging. Korean J. Radiol. 2018;19:767–776. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.19.4.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sathyanesan A, Zhou J, Scafidi J, Heck DH, Sillitoe RV, Gallo V. Emerging connections between cerebellar development, behaviour and complex brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019;20:298–313. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0152-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coombes SA, Misra G. Pain and motor processing in the human cerebellum. Pain. 2016;157:117–127. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ruscheweyh R, Kuhnel M, Filippopulos F, Blum B, Eggert T, Straube A. Altered experimental pain perception after cerebellar infarction. Pain. 2014;155:1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Conway BR. The organization and operation of inferior temporal cortex. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2018;4:381–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev-vision-091517-034202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin YH, Young IM, Conner AK, Glenn CA, Chakraborty AR, Nix CE, Bai MY, Dhanaraj V, Fonseka RD, Hormovas J, et al. Anatomy and white matter connections of the inferior temporal gyrus. World Neurosurg. 2020;143:e656–e666. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wei HL, Li J, Guo X, Zhou GP, Wang JJ, Chen YC, Yu YS, Yin X, Li J, Zhang H. Functional connectivity of the visual cortex differentiates anxiety comorbidity from episodic migraineurs without aura. J. Headache Pain. 2021;22:40. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01259-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang H, Li Q, Liu L, Qu X, Wang Q, Yang B, Xian J. Altered microstructure of cerebral gray matter in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder-optic neuritis: A DKI study. Front. Neurosci. 2021;15:738913. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.738913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vingen JV, Pareja JA, Storen O, White LR, Stovner LJ. Phonophobia in migraine. Cephalalgia. 1998;18:243–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1805243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harriott AM, Schwedt TJ. Migraine is associated with altered processing of sensory stimuli. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18:458. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sebastianelli G, Abagnale C, Casillo F, Cioffi E, Parisi V, Di Lorenzo C, Serrao M, Porcaro C, Schoenen J, Coppola G. Bimodal sensory integration in migraine: A study of the effect of visual stimulation on somatosensory evoked cortical responses. Cephalalgia. 2022;42:654–662. doi: 10.1177/03331024221075073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kelman L, Tanis D. The relationship between migraine pain and other associated symptoms. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:548–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Riyazuddin M, Shahid A, Nagaraj RB, Alam MA. Migraine (Shaqeeqa) and its management in Unani medicine. Drug Metab. Pers. Ther. 2021;37:1–5. doi: 10.1515/dmpt-2021-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ishikawa T, Tatsumoto M, Maki K, Mitsui M, Hasegawa H, Hirata K. Identification of everyday sounds perceived as noise by migraine patients. Intern. Med. 2019;58:1565–1572. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2206-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Friedman DI, Dever Dye T. Migraine and the environment. Headache. 2009;49:941–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Forss N, Merlet I, Vanni S, Hamalainen M, Mauguiere FO, Hari R. Activation of human mesial cortex during somatosensory target detection task. Brain Res. 1996;734:229–235. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li K, Huang X, Han Y, Zhang J, Lai Y, Yuan L, Lu J, Zeng D. Enhanced neuroactivation during working memory task in postmenopausal women receiving hormone therapy: A coordinate-based meta-analysis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015;9:35. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fang Z, Smith DM, Houldin E, Ray L, Owen AM, Fogel S. The relationship between cognitive ability and BOLD activation across sleep-wake states. Brain Imaging Behav. 2022;16:305–315. doi: 10.1007/s11682-021-00504-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pozhidaev KA, Parfenov VA. Cognitive and emotional disorders in patients with migraine and signs of leukoencephalopathy. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2021;121:7–12. doi: 10.17116/jnevro20211210317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huang L, Juan Dong H, Wang X, Wang Y, Xiao Z. Duration and frequency of migraines affect cognitive function: Evidence from neuropsychological tests and event-related potentials. J. Headache Pain. 2017;18:54. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0758-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Andrews-Hanna JR, Smallwood J, Spreng RN. The default network and self-generated thought: component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014;1316:29–52. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mohan A, Roberto AJ, Mohan A, Lorenzo A, Jones KL, Carney MJ, Liogier-Weyback LER, Hwang S, Lapidus KAB. The significance of the default mode network (DMN) in neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders: A review. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2016;89:49–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Argaman Y, Kisler LB, Granovsky Y, Coghill RC, Sprecher E, Manor D, Weissman-Fogel I. The endogenous analgesia signature in the resting brain of healthy adults and migraineurs. J. Pain. 2020;21:905–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hemington KS, Wu Q, Kucyi A, Inman RD, Davis KD. Abnormal cross-network functional connectivity in chronic pain and its association with clinical symptoms. Brain Struct. Funct. 2016;221:4203–4219. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bosma RL, Kim JA, Cheng JC, Rogachov A, Hemington KS, Osborne NR, Oh J, Davis KD. Dynamic pain connectome functional connectivity and oscillations reflect multiple sclerosis pain. Pain. 2018;159:2267–2276. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Aytur SA, Ray KL, Meier SK, Campbell J, Gendron B, Waller N, Robin DA. Neural mechanisms of acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: A network-based fMRI approach. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021;15:587018. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.587018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Iwatsuki K, Hoshiyama M, Yoshida A, Uemura J-I, Hoshino A, Morikawa I, Nakagawa Y, Hirata H. Chronic pain-related cortical neural activity in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2021;10:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ibneur.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tessitore A, Russo A, Giordano A, Conte F, Corbo D, De Stefano M, Cirillo S, Cirillo M, Esposito F, Tedeschi G. Disrupted default mode network connectivity in migraine without aura. J. Headache Pain. 2013;14:89. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-14-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Seghier ML. The angular gyrus: Multiple functions and multiple subdivisions. Neuroscientist. 2013;19:43–61. doi: 10.1177/1073858412440596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhao Z, Lu J, Jia X, Chao W, Han Y, Jia J, Li K. Selective changes of resting-state brain oscillations in aMCI: an fMRI study using ALFF. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014;2014:920902. doi: 10.1155/2014/920902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Moretti DV. Increase of EEG Alpha3/Alpha2 power ratio detects inferior parietal lobule atrophy in mild cognitive impairment. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2018;15:443–451. doi: 10.2174/1567205014666171030105338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen PY, Hsu HY, Chao YP, Nouchi R, Wang PN, Cheng CH. Altered mismatch response of inferior parietal lobule in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A magnetoencephalographic study. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2021;27:1136–1145. doi: 10.1111/cns.13691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tian Z, Guo Y, Yin T, Xiao Q, Ha G, Chen J, Wang S, Lan L, Zeng F. Acupuncture modulation effect on pain processing patterns in patients with migraine without aura. Front. Neurosci. 2021;15:729218. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.729218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Qin ZX, Su JJ, He XW, Zhu Q, Cui YY, Zhang JL, Wang MX, Gao TT, Tang W, Hu Y, et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity between subregions in the thalamus and cortex in migraine without aura. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020;27:2233–2241. doi: 10.1111/ene.14411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhe X, Zhang X, Chen L, Zhang L, Tang M, Zhang D, Li L, Lei X, Jin C. Altered gray matter volume and functional connectivity in patients with vestibular migraine. Front. Neurosci. 2021;15:683802. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.683802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tomasi D, Volkow ND. Association between functional connectivity hubs and brain networks. Cereb. Cortex. 2011;21:2003–2013. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Amaral VCG, Tukamoto G, Kubo T, Luiz RR, Gasparetto E, Vincent MB. Migraine improvement correlates with posterior cingulate cortical thickness reduction. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2018;76:150–157. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x20180004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Brennan KC, Pietrobon D. A systems neuroscience approach to migraine. Neuron. 2018;97:1004–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Burstein R, Noseda R, Borsook D. Migraine: Multiple processes, complex pathophysiology. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:6619–6629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0373-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rudebeck PH, Rich EL. Orbitofrontal cortex. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:R1083–R1088. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang D, Huang X, Mao C, Chen Y, Miao Z, Liu C, Xu C, Wu X, Yin X. Assessment of normalized cerebral blood flow and its connectivity with migraines without aura during interictal periods by arterial spin labeling. J. Headache Pain. 2021;22:72. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01282-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Biagianti B, Grazzi L, Gambini O, Usai S, Muffatti R, Scarone S, Bussone G. Orbitofrontal dysfunction and medication overuse in patients with migraine. Headache. 2012;52:1511–1519. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schmitz N, Arkink EB, Mulder M, Rubia K, Admiraal-Behloul F, Schoonman GG, Kruit MC, Ferrari MD, van Buchem MA. Frontal lobe structure and executive function in migraine patients. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;440:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Camarda C, Monastero R, Pipia C, Recca D, Camarda R. Interictal executive dysfunction in migraineurs without aura: Relationship with duration and intensity of attacks. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:1094–1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dieterich M. Functional brain imaging: A window into the visuo-vestibular systems. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2007;20:12–18. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328013f854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Teggi R, Colombo B, Rocca MA, Bondi S, Messina R, Comi G, Filippi M. A review of recent literature on functional MRI and personal experience in two cases of definite vestibular migraine. Neurol. Sci. 2016;37:1399–1402. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2618-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Radtke A, von Brevern M, Neuhauser H, Hottenrott T, Lempert T. Vestibular migraine: long-term follow-up of clinical symptoms and vestibulo-cochlear findings. Neurology. 2012;79:1607–1614. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e264f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lampl C, Rapoport A, Levin M, Brautigam E. Migraine and episodic Vertigo: A cohort survey study of their relationship. J. Headache Pain. 2019;20:33. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-0991-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Swaminathan A, Smith JH. Migraine and vertigo. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2015;15:515. doi: 10.1007/s11910-014-0515-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cavada C, Goldman-Rakic PS. Posterior parietal cortex in rhesus monkey: II. Evidence for segregated corticocortical networks linking sensory and limbic areas with the frontal lobe. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;287:422–445. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wilcox CE, Mayer AR, Teshiba TM, Ling J, Smith BW, Wilcox GL, Mullins PG. The subjective experience of pain: An FMRI study of percept-related models and functional connectivity. Pain Med. 2015;16:2121–2133. doi: 10.1111/pme.12785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wang WE, Ho RLM, Gatto B, van der Veen SM, Underation MK, Thomas JS, Antony AB, Coombes SA. Cortical dynamics of movement-evoked pain in chronic low back pain. J. Physiol. 2021;599:289–305. doi: 10.1113/JP280735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rushworth MF, Johansen-Berg H, Gobel SM, Devlin JT. The left parietal and premotor cortices: motor attention and selection. Neuroimage. 2003;20(Suppl 1):S89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ngo GN, Haak KV, Beckmann CF, Menon RS. Mesoscale hierarchical organization of primary somatosensory cortex captured by resting-state-fMRI in humans. Neuroimage. 2021;235:118031. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wei HL, Chen J, Chen YC, Yu YS, Guo X, Zhou GP, Zhou QQ, He ZZ, Yang L, Yin X, et al. Impaired effective functional connectivity of the sensorimotor network in interictal episodic migraineurs without aura. J. Headache Pain. 2020;21:111. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01176-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Dalgleish AS, Kania AM, Stauss HM, Jelen AZ. Occipitoatlantal decompression and noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation slow conduction velocity through the atrioventricular node in healthy participants. J. Osteopath. Med. 2021;121:349–359. doi: 10.1515/jom-2020-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Straube A, Eren O. tVNS in the management of headache and pain. Auton. Neurosci. 2021;236:102875. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Allais G, Chiarle G, Sinigaglia S, Benedetto C. Menstrual migraine: A review of current and developing pharmacotherapies for women. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2018;19:123–136. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1414182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.