Abstract

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by painful abscesses and nodules, has limited effective treatment options. However, adjuncts to standard therapeutics such as dietary modifications have been increasingly investigated in recent years. This comprehensive review aimed to analyze the literature concerning the relationship between HS and 28 essential vitamins and minerals. A literature search was performed via PubMed, Embase, Ovid, and Scopus using search terms related to HS and the essential vitamins and minerals. A total of 215 unique articles were identified and analyzed. Twelve essential nutrients had documented associations with HS; definitive supplementation or monitoring recommendations were identified for 7 of the 12 HS-associated nutrients in the literature. Evidence is growing that supports adjunct supplementation of zinc, vitamin A, and vitamin D in the treatment of HS. Further, obtaining serum levels of zinc, vitamin A, vitamin D, and vitamin B12 upon initial diagnosis of HS may be beneficial to optimize standard HS treatment. In conclusion, optimizing nutrition in addition to standard HS therapeutics may help reduce disease burden; however more research is needed.

Keywords: Hidradenitis suppurativa, Nutrition, Vitamins, Minerals, Supplements

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as acne inversa and Verneuil's disease, is a chronic, inflammatory disease characterized by painful abscesses and nodules that can rupture and form draining sinus tracts with scarring [1]. Currently, there are limited efficacious conventional treatment options for HS, which leads many patients to seek alternative approaches to manage their disease [2]. While the dietary factors contributing to the pathoetiology of HS are not well understood, dietary modification as a potential treatment for HS has only become more prevalent in recent years [3].

Recent literature examining the impact of dietary modifications on HS has been increasing [2]. The main topics of HS-associated nutrition studies include weight loss, zinc, vitamin D, vitamin B12, and dairy [4, 5]. With a growing interest in nutritional supplementation as an adjunct therapy for HS, identifying patterns of derangements in the essential vitamins and minerals in HS patients could highlight critical areas for further research. Macronutrients, such as proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates, are the highest energy-yielding form of nutrition, and micronutrients are vitamins and elements required in micro- or milligram quantities for metabolic pathways [6, 7]; optimizing macronutrients and micronutrients through supplementation or dietary modifications in HS patients could effectively decrease flares and promote lesion resolution.

The primary objective of this literature review is to identify which essential vitamins and minerals are proven to be beneficial in HS. Additionally, we aimed to evaluate patterns of vitamin and mineral derangements in HS patients and identify current supplementation recommendations.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Five Key Vitamins and Minerals

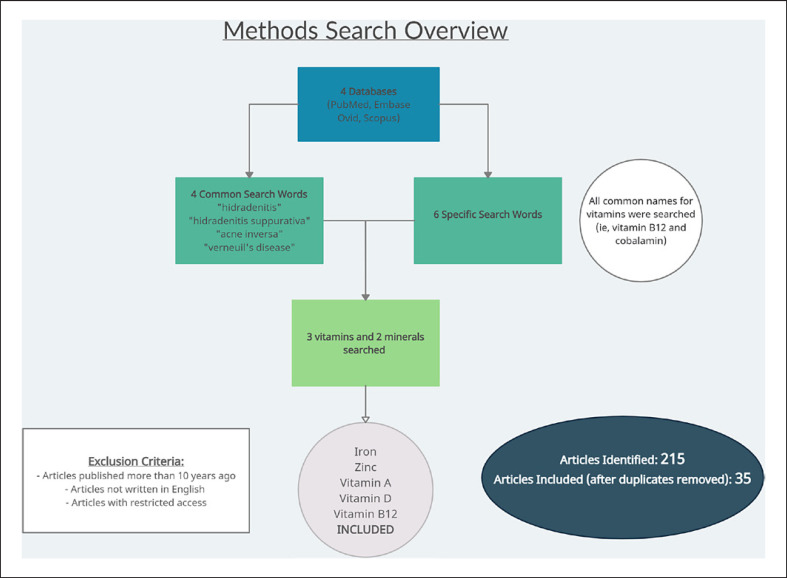

In our analysis of the currently available data, we performed an extensive literature search via PubMed, Embase, Ovid, and Scopus using the following search terms: “hidradenitis,” OR “hidradenitis suppurativa,” OR “acne inversa,” OR “verneuil's disease” AND one of the following search terms: “vitamin A,” OR “vitamin C,” OR “vitamin D,” OR “vitamin E,” OR “vitamin K,” OR “thiamin,” OR “vitamin B1,” OR “riboflavin,” OR “vitamin B2,” OR “niacin,” OR “vitamin B3,” OR “pantothenic acid,” OR “vitamin B5,” OR “pyridoxine,” OR “vitamin B6,” OR “cobalamin,” OR “vitamin B12,” OR “biotin,” OR “vitamin B7,” OR “folate,” OR “vitamin B9,” OR “calcium,” OR “phosphorus,” OR “potassium,” OR “sodium,” OR “chloride,” OR “magnesium,” OR “iron,” OR “zinc,” OR “iodine,” OR “sulfur,” OR “cobalt,” OR “copper,” OR “fluoride,” OR “manganese,” OR “selenium.” The searches were restricted to the past 10 years. Of the 215 unique articles that resulted from our literature search, 35 articles contained relevant information regarding the 5 vitamins and minerals that we will focus on in this review (Fig. 1). The 5 vitamins and minerals that most frequently were found to play a role in HS include zinc, iron, vitamin D, vitamin A, and vitamin B12, which are the focus of this review.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of literature review study design.

Zinc

Zinc supplementation is one of the most recommended non-pharmacologic approaches to treating HS [5, 6, 7, 8]. Multiple sources provide evidence that zinc levels are frequently deficient in HS [4, 9, 10]. According to a case-control study by Poveda et al. [11], low-serum zinc levels (≤83.3 μg/dL) were more common in HS patients than in controls.

Various retrospective studies have accounted for the efficacy of oral zinc treatment in improving symptoms and inflammatory skin lesions in HS [8, 12]. Zinc supplementation has been shown to induce a significant increase in the expression of many innate immunity markers, significantly improve dermatology life quality index scores, and lead to partial remission in greater than 60% of patients receiving the mineral [11, 13, 14]. Zinc treatment shows a dose-response relationship; studies have revealed that when zinc was reduced from 90 mg to 60 mg and below, HS patients in remission experienced relapsing lesions [15]. It is notable that serum zinc levels were not assessed prior to oral supplementation in these studies; it is unclear whether zinc supplementation is helpful for all patients or only for those with low zinc levels. Although zinc has shown promising results, there are currently no randomized controlled trials which have been conducted to establish the effectiveness of zinc supplementation in HS. Zinc supplementation is generally safe, with gastrointestinal symptoms being the most reported side effects, which can be prevented by consuming zinc with meals. Copper deficiency can rarely result from zinc supplementation, which can be resolved with zinc discontinuation and copper repletion [16]. Table 1 outlines the current clinical recommendations for zinc monitoring and supplementation.

Table 1.

Vitamin and mineral recommendations for patients with HS

| Vitamins/minerals | Levels in HS patients | Supplementation and other recommendations | Study type | Clinical considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | Low* | Acitretin, isotretinoin, and alitretinoin can be used as adjunct therapies for HS40: grade B recommendation**, level II evidencea Mild or moderate disease, combination therapy with isotretinoin and spironolactone or adalimumab [17] |

Systematic review [18] Retrospective chart review |

Vitamin A toxicity can occur with chronic ingestion of large amounts of synthetic vitamin A (approximately 10 times higher than the recommended dietary allowance, or approximately 50,000 international units) Retinoic acid, a vitamin A metabolite, is teratogenic in the first trimester of pregnancy [19] |

|

| ||||

| Vitamin D | Low | Check vitamin D levels at the time of initial diagnosis and document levels over time, noting low levels of 25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)D] below 20 ng/mL Vitamin D supplementation as HS treatment: grade B/C recommendation**b, level II/III evidence a, c Supplementation with cholecalciferol is preferred over ergocalciferol; cholecalciferol more efficaciously raises serum 25(OH)D [20] |

Retrospective study [21] Non-randomized controlled trials [20, 22] |

To assess vitamin D status: obtain serum 25(OH)D Deficiency: 25(OH)D levels <12 ng/mL (<30 nmol/L), insufficiency: 25(OH)D levels <20 ng/mL (<50 nmol/L) 25(OH)D target range for repletion: 20–40 ng/mL Vitamin D toxicity may occur with excessive doses. Monitor for symptoms of hypervitaminosis D. [22] |

|

| ||||

| Vitamin B12 | Low* | Check vitamin B12 levels in HS patients who are elderly, obese, have signs of cardiovascular disease or have alcohol use disorder to optimize management with standard HS therapeutics [5, 23] Biweekly supplementation with 1,000 µg vitamin B12 intramuscular in patients with HS and Chron's disease [24] |

Case series Case-control study |

There is no high-quality evidence that supplemental vitamin B12 is beneficial in patients with HS eating a balanced diet [25] |

|

| ||||

| Iron | Low | Serial hemoglobin measurements to assess HS disease severity and response to treatment Diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia [26] ↓Red blood cell (RBC) count ↓ Hemoglobin and hematocrit ↓ Absolute reticulocyte count ↓ Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) |

Case report | Numerous oral iron formulations are available and are equally effective. Liquid iron (allows for dose titration) or tablets containing ferrous salts are the most effective for treating iron deficiency anemia Gastrointestinal side effects are common with oral iron administration. Changing the frequency of supplementation to every other day and with meals may improve symptoms [26] |

|

| ||||

| Zinc | Low | No recommendations to measure or monitor serum zinc levels Zinc pharmacological forms: zinc gluconate [8], zinc glutamate [12], pyrithione zinc (grade C recommendation, b level III evidencec) [13, 27], oral zinc with niacinamide [6], zinc-sulfate-based regimens [5, 27], and in combination with antibiotics [7] Daily oral zinc gluconate supplementation of 90 mg (grade C recommendation,b level II evidencea) [12] Cleanser for hair-bearing areas: pyrithione zinc-containing (1%) shampoos [27] |

Systematic literature review CME article 13 | Gastrointestinal side effects are more common with zinc sulfate administration. Consuming zinc with meals or switching to zinc gluconate may improve symptoms [27] |

Accompanied by other micronutrient deficiencies.

Grade B recommendation: recommendation based on inconsistent or limited quality patient-oriented evidence (morbidity, mortality, symptom improvement, cost reduction, quality of life) [28].

Level II evidence: evidence provided from limited quality patient-oriented evidence [29].

Grade C recommendation: recommendation based on consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence (intermediate, physiologic, or surrogate endpoints that may or may not reflect improvements in patient outcomes), and case series for studies of diagnosis, treatment, prevention, or screening [28].

Level III evidence: evidence provided from consensus guidelines, extrapolations from bench research, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence (intermediate or physiologic outcomes only), and case series for studies of diagnosis, treatment, prevention, or screening [28].

Iron

Soliman et al. [30] and Parameswaran et al. [31] conducted large-scale retrospective studies that showed that HS patients are significantly more likely to have a diagnosis of anemia compared to the general population. With the higher prevalence of anemia in the HS population, derangement of iron status has been an important area of study. Anemia in HS typically comes in two forms, iron deficiency anemia and anemia of chronic disease (ACD) [32]. Iron deficiency anemia is characterized by a reduction in the body's total iron content, whereas ACD is found in individuals with diseases that induce active immune and inflammatory responses that lead to reduced iron uptake from varying sites [30, 32].

Studies hypothesize that the HS disease process leads to ACD via upregulation of IL-6 and hepcidin, an inflammatory mediator involved in mobilization and usage of iron from body stores [32]. While studies have used this evidence to support the assertion that anemia in the HS population is predominantly caused by chronic inflammation, one study showed that abnormalities in iron status were neither related to proinflammatory activation nor associated with disease severity [33, 34]. The results of this study did not present alternative associations for abnormal iron status. Overall, derangements in iron status in the HS population could potentially be caused by either iron sequestration in the setting of chronic inflammation or loss of blood via copious amounts of serosanguinous fluids seen in very severe disease states [32]. Our review of literature did not yield any evidence that iron deficiency may be implicated in the pathogenesis of HS.

Few studies suggest measuring HS patients' hemoglobin or hepcidin levels to establish the presence of anemia to guide supplementation and assess treatment response. Both hemoglobin and hepcidin have been proposed as biomarkers for active disease and inflammation in HS to measure disease severity objectively [21, 35]. Proposed iron recommendations for HS patients are shown in Table 1.

Vitamin D

There is a substantial amount of evidence in the literature demonstrating low vitamin D levels in patients with HS; HS patients are 5.47 times more likely to develop a vitamin D deficiency [36]. Numerous studies have also shown an inverse relationship between vitamin D levels and the number of HS lesions and disease severity [37]. In a pilot study from 2021, researchers measured 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels in the serum of 248 HS patients [38]. Results showed that 198 patients (79.84%) were vitamin D deficient, 50 patients (20.16%) were vitamin D insufficient, and two patients (0.8%) were vitamin D sufficient [38]. This study also correlated elevated C-reactive protein levels and increased disease severity with vitamin D levels less than 20 ng/mL [17, 24]. Additionally, recent research investigating the relationship between low vitamin D, HS, and obesity has revealed that low vitamin D levels are positively correlated with high body mass index (BMI) [39]. This supports the theory that obesity is a state of malnutrition and that low vitamin D levels in those with high BMIs may be associated with other micronutrient deficiencies [14].

Strong evidence suggests that vitamin D may play a role in the pathogenesis of HS in select patients; HS causes abnormal keratinocyte proliferation and hair growth cycles that may be correctable by exogenous vitamin D administration [5]. Supplementation of vitamin D in HS patients has led to a reduction of the number of HS-associated lesions in separate studies [4, 24]. One study demonstrated that supplementation of vitamin D in Vitamin D-deficient HS patients significantly decreased the number of nodules in 79% of patients, with 20% reporting fewer flares at 6-month follow-up on maintenance therapy [4, 24]. A summary of current vitamin D supplementation recommendations is provided in Table 1.

Vitamin B12

Few studies evaluating vitamin B12 status in HS patients have been published. Limited studies have identified an increased prevalence of low vitamin B12 levels in HS patients compared to controls [5, 40]. However, research suggests that isolated vitamin B12 deficiency is uncommon and is usually accompanied by other micronutrient deficiencies [4].

A recent systematic review by Hendricks et al. [5] hypothesized that adjunctive B12 therapy might aid HS treatment through immunomodulation. HS patients may have low levels of S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe), and methionine synthase activity, which are critical cobalamin-dependent enzymes revealed to reduce tumor necrosis factor levels in mouse models [40]. We speculate that HS patients may have lower levels of SAMe secondary to chronic inflammation; SAMe is a known inhibitor of the anti-inflammatory response, which may be impaired in chronic inflammatory states [41]. Researchers theorized that high-dose B12 supplementation would improve elevated tumor necrosis factor levels secondary to low SAMe in HS patients [5].

No randomized controlled trials that evaluate adjunctive vitamin B12 supplementation in HS patients exist. However, review of the literature found three case series reporting complete resolution of HS lesions in patients with concurrent Crohn's disease after biweekly supplementation with intramuscular 1,000 μg vitamin B12; two of the three cases reported the patient having normal B12 levels, and the third case did not comment on its patient's B12 level [4, 42]. A summary of current vitamin B12 supplementation recommendations is provided in Table 1.

Vitamin A

Limited studies have highlighted the use of vitamin A or its derivatives for managing patients with HS. Although vitamin A derivatives are not a first-line therapy for HS, some studies have found them beneficial with recognized standard HS therapeutics. An analysis by McPhie et al. [43] in 2019 concluded that combination therapy with isotretinoin was helpful in treating mild to moderate HS. Over the years, select retrospective studies have conjectured that isotretinoin may be beneficial for patients with mild to moderate HS who are female, young, have lower BMIs, and have a personal history of acne [43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49].

Acitretin and alitretinoin, two vitamin A derivatives, have been identified as potential HS therapy adjuncts. A systematic review conducted in 2012 determined that acitretin was superior to isotretinoin in treating HS; however, the acitretin group had a significantly smaller sample size than the isotretinoin group [47]. A prospective study found acitretin beneficial in nine patients who took it for 9 months at a mean dose of 0.56 ± 0.08 mg/kg, with clinical improvement exhibited after the first month [50]. However, while acitretin may be efficacious in some patients, other patients may not tolerate side effects such as cheilitis, dry skin, hair loss, and arthralgias [18, 50]. Other studies suggest that acitretin fails to show therapeutic benefit when used in isolation; however, when used as adjuvant therapy with standard HS medications, clinical response is observed and ranges from partial to complete resolution of HS lesions [51].

In addition to treating the lesions associated with HS, a recent study found vitamin A analogs to help treat arthritis associated with HS when used alongside NSAIDs and immunosuppressive agents [20]. A summary of current vitamin A supplementation recommendations is provided in Table 1.

Conclusion

Of the essential vitamins and minerals, zinc, vitamin D, vitamin B12, and vitamin A have been shown to have beneficial effects in HS patients. While more studies are needed to assess vitamin and mineral supplementation as adjunct therapies with standard medications, evidence is mounting that supplementation of zinc, vitamin A, vitamin B12, and vitamin D has the potential to improve HS disease burden. Additionally, studies have shown that HS patients are at an increased risk for low iron, zinc, vitamin D, and vitamin B12. With the knowledge that HS patients are at risk for certain micronutrient deficiencies, it may be reasonable to evaluate micronutrient levels in select populations to optimize nutrition while initiating standard HS therapeutics.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Author Contributions

Sydney Alexis Weir conceptualized the project and participated in data collection and all aspects of writing and editing of the manuscript. Brittany Roman, Victoria Jiminez, and Meredith Burns participated in data collection and writing and editing of the manuscript. Adaugo Sanyi participated in conceptualization of the project, supervision of data collection, and writing and editing of the manuscript. Boni Elewski: participated in conceptualization and writing and editing of the manuscript. Tiffany Mayo participated in conceptualization of the project, supervision of data collection, and editing and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

References

- 1.Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, Shear N, Yeung J. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63((2)):114–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020 Aug 26;9:F1000. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.26083.1. Faculty Rev-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silfvast-Kaiser A, Youssef R, Paek SY. Diet in hidradenitis suppurativa a review of published and lay literature. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58((11)):1225–1230. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi F, Lehmer L, Ekelem C, Mesinkovska NA. Dietary and metabolic factors in the pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59((2)):143–153. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendricks AJ, Hirt PA, Sekhon S, Vaughn AR, Lev-Tov HA, Hsiao JL, et al. Non-pharmacologic approaches for hidradenitis suppurativa - a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32((1)):11–18. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1621981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.San-Cristobal R, Navas-Carretero S, Martínez-González MÁ, Ordovas JM, Martínez JA. Contribution of macronutrients to obesity implications for precision nutrition. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16((6)):305–320. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opara EC, Rockway SW. Antioxidants and micronutrients. Dis Mon. 2006;52((4)):151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molinelli E, Brisigotti V, Campanati A, Sapigni C, Giacchetti A, Cota C, et al. Efficacy of oral zinc and nicotinamide as maintenance therapy for mild/moderate hidradenitis suppurativa a controlled retrospective clinical study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83((2)):665–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poveda I, Vilarrasa E, Martorell A, Garcia-Martinez FJ, Segura JM, Hispan P, et al. Serum zinc levels in hidradenitis suppurativa a case-control study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19((5)):771–777. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcovich S, De Simone C, Giovanardi G, Robustelli E, Marzano AV, Peris K. Post-bariatric surgery hidradenitis suppurativa a new patient subset associated with malabsorption and micronutritional deficiencies. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44((3)):283–289. doi: 10.1111/ced.13732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hessam S, Sand M, Meier NM, Gambichler T, Scholl L, Bechara FG. Combination of oral zinc gluconate and topical triclosan an anti-inflammatory treatment modality for initial hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84((2)):197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Straalen KR, Schneider-Burrus S, Prens EP. Current and future treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183((6)):e178–e187. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brocard A, Knol AC, Khammari A, Dreno B. Hidradenitis suppurativa and zinc a new therapeutic approach. A pilot study. Dermatology. 2007;214((4)):325–327. doi: 10.1159/000100883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dreno B, Khammari A, Brocard A, Moyse D, Blouin E, Guillet G, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa the role of deficient cutaneous innate immunity. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148((2)):182–186. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa current and emerging treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82((5)):1061–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melamed E, Kiambi P, Okoth D, Honigber I, Tamir E, Borkow G. Healing of chronic wounds by copper oxide-impregnated wound dressings-case series. Medicina. 2021;57((3)):296. doi: 10.3390/medicina57030296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cetinarslan T, Turel Ermertcan A, Ozyurt B, Gunduz K. Evaluation of the laboratory parameters in hidradenitis suppurativa can we use new inflammatory biomarkers? Dermatol Ther. 2021;34((2)):e14835. doi: 10.1111/dth.14835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LiverTox Clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury. Bethesda (MD) 2020.

- 19.Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, Alhusayen R, Brassard A, Burkhart C, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: Part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81((1)):76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The articular manifestations of hidradenitis suppurativa J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;3((AB282)) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghias M, Cameron S, Shaw F, Soliman Y, Kutner A, Chaitowitz M, et al. Anemia in hidradenitis suppurativa hepcidin as a diagnostic tool. Am J Clin Pathol. 2019;152((Suppl ment_1)):S15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blok JL, van Hattem S, Jonkman MF, Horvath B. Systemic therapy with immunosuppressive agents and retinoids in hidradenitis suppurativa a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168((2)):243–252. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tripkovic L, Lambert H, Hart K, Smith CP, Bucca G, Penson S, et al. Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95((6)):1357–1364. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.031070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guillet A, Brocard A, Bach Ngohou K, Graveline N, Leloup AG, Ali D, et al. Verneuil's disease innate immunity and vitamin D a pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29((7)):1347–1353. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marasca C, Donnarumma M, Annunziata MC, Fabbrocini G. Homocysteine plasma levels in patients affected by hidradenitis suppurativa an Italian experience. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44((3)):e28–e29. doi: 10.1111/ced.13798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fairfield K. Vitamin supplementation in disease prevention. Waltham, MA. UpToDate. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auerbach M. Treatment of iron deficiency anemia in adults. Waltham, MA. 2023 UpToDate. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danesh MJ, Kimball AB. Pyrithione zinc as a general management strategy for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73((5)):e175. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, Woolf SH, Susman J, Ewigman B, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT) a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17((1)):59–67. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soliman YS, Chaitowitz M, Hoffman LK, Lin J, Lowes MA, Cohen SR. Identifying anaemia in a cohort of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34((1)):e5–e8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parameswaran A, Garshick MS, Revankar R, Lu CPJ, Chiu ES, Sicco KIL. Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with iron deficiency anemia anemia of chronic disease and sickle cell anemia-A single-center retrospective cohort study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7((5 Part B)):675–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghias MH, Johnston AD, Babbush KM, Kutner AJ, Hosgood HD, Lowes MA, et al. Hepcidin levels can distinguish anemia of chronic disease from iron deficiency anemia in a cross-sectional study of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86((4)):954–956. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deckers IE, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Severe fatigue based on anaemia in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa report of two cases and a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30((1)):174–175. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponikowska M, Matusiak L, Kasztura M, Jankowska EA, Szepietowski JC. Deranged iron status evidenced by iron deficiency characterizes patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2020;236((1)):52–58. doi: 10.1159/000505184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braunberger TL, Lowes MA, Hamzavi IH. Hemoglobin as an indicator of disease activity in severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58((9)):1090–1091. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vekic DA, Woods J, Lin P, Cains GD. SAPHO syndrome associated with hidradenitis suppurativa and pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with adalimumab and methotrexate a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57((1)):10–18. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanchez-Diaz M, Salvador-Rodriguez L, Montero-Vilchez T, Martinez-Lopez A, Arias-Santiago S, Molina-Leyva A. Cumulative inflammation and HbA1c levels correlate with increased intima-media thickness in patients with severe hidradenitis suppurativa. J Clin Med. 2021;10((22)):5222. doi: 10.3390/jcm10225222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moltrasio C, Tricarico PM, Genovese G, Gratton R, Marzano AV, Crovella S. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D serum levels inversely correlate to disease severity and serum C-reactive protein levels in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol. 2021;48((5)):715–717. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirsten N, Augustin M, Hilbring C, Girbig G, Sensen J, Zyriax B-C. Vitamin D and its correlation with BMI and MEDAS score in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa− results of a unicentric cross-sectional study. European Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. 2020;Vol. 9 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brescoll J, Daveluy S. A review of vitamin B12 in dermatology. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16((1)):27–33. doi: 10.1007/s40257-014-0107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfalzer AC, Choi S-W, Tammen SA, Park LK, Bottiglieri T, Parnell LD, et al. S-adenosylmethionine mediates inhibition of inflammatory response and changes in DNA methylation in human macrophages. Physiol Genomics. 2014;46((17)):617–623. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00056.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mortimore M, Florin THJ. A role for B(1)(2) in inflammatory bowel disease patients with suppurative dermatoses? An experience with high dose vitamin B(1)(2) therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4((4)):466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McPhie ML, Bridgman AC, Kirchhof MG. Combination therapies for hidradenitis suppurativa a retrospective chart review of 31 patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23((3)):270–276. doi: 10.1177/1203475418823529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel N, McKenzie SA, Harview CL, Truong AK, Shi VY, Chen L, et al. Isotretinoin in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa a retrospective study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32((4)):473–475. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1670779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jørgensen AHR, Thomsen SF, Ring HC. Isotretinoin and hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44((4)):e155–e156. doi: 10.1111/ced.13953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soria A, Canoui-Poitrine F, Wolkenstein P, Poli F, Gabison G, Pouget F, et al. Absence of efficacy of oral isotretinoin in hidradenitis suppurativa a retrospective study based on patients' outcome assessment. Dermatology. 2009;218((2)):134–135. doi: 10.1159/000182261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheinfeld N. Hidradenitis suppurativa a practical review of possible medical treatments based on over 350 hidradenitis patients. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19((4)):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boer J, van Gemert MJ. Long-term results of isotretinoin in the treatment of 68 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40((1)):73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70530-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang CM, Kirchhof MG. A new perspective on isotretinoin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa a retrospective chart review of patient outcomes. Dermatology. 2017;233((2–3)):120–125. doi: 10.1159/000477207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matusiak L, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Acitretin treatment for hidradenitis suppurativa a prospective series of 17 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171((1)):170–174. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan MG, Shear NH, Walsh S, Alhusayen R. Acitretin. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21((1)):48–53. doi: 10.1177/1203475416659858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]