Abstract

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is an acquired polyposis syndrome with gastrointestinal and extraintestinal manifestations. Given its rarity and lack of standard treatment, diagnosis and treatment are challenging. Steroid therapy and nutritional support are conventional treatments. There is no consensus on management of steroid-refractory cases. Here, we report the diagnosis and treatment course of a 54-year-old Asian male with CCS, whose initial treatment with prednisone 60 mg a day led to partial response and disease flare up during prednisone tapering. The use of infliximab and azathioprine led to promising remission of his symptoms.

Keywords: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, gastrointestinal polyps, cutaneous hyperpigmentation, onychodystrophy, steroid-resistant Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, gastroenterology

Introduction

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a noninherited polyposis disease which usually presents with abdominal pain and diarrhea accompanied by extra-gastrointestinal symptoms such as hyperpigmentation, alopecia, and onychodystrophy. 1 Diagnosis of CCS is challenging as its clinical, endoscopic, and even histological features overlap with other polyposis or inflammatory bowel diseases. 2

Given its rarity, there is no consensus regarding the etiology of the disease. However, immune dysregulation has been blamed due to its association with other autoimmune disorders and immunoglobulin G subclass-4 positivity on immunostaining of the polyps.3-5

While steroid administration accompanied by nutritional support is known as the conventional treatment, there are inconsistencies in the outcome. 6 About 16% of patients with CCS have been reported to be steroid resistant. 7 There are few emerging reports that patients with steroid-refractory CCS had satisfactory clinical response with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-a) medication. 8 Here, we present a patient with CCS who had clinical and endoscopic response to treatment with anti-TNF-a, infliximab, and immunosuppressive therapy, azathioprine.

Case Report

A 54-year-old Asian man with a history of hypertension presented with abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, and weight loss for several months. Before presenting to our gastroenterology clinic, he was initially seen at another facility 6 months prior and underwent colonoscopy which revealed a diffusely granular and nodular colon with polyposis. He was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis and was started on a 4-week course of prednisone and mesalamine. He returned to the hospital a few weeks later with persistent abdominal pain. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast showed nonspecific prominence of the gastric mucosal folds and diffuse colonic wall thickening with pericolonic edema suggestive of pancolitis. He underwent repeat upper endoscopy and colonoscopy and was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis with associated polyposis for which colectomy was recommended. Concerned about the colectomy and persistent symptoms, he presented to us for a second opinion. During initial evaluation, the patient reported loss of appetite, abdominal pain, diarrhea with 10 to 20 stools a day, and occasional melena. He also noticed generalized muscle loss, bilateral leg edema, progressive alopecia, onychodystrophy in all digits, and skin discoloration most notably on the palms, soles, and scalp (Figure 1A). He denied fever, night sweet, cough, or shortness of breath. The patient had a history of alcohol and tobacco use but quit both 24 years before presentation. The patient had exposure to chemical cleaning agents during his military service. He denies a family history of gastrointestinal malignancy.

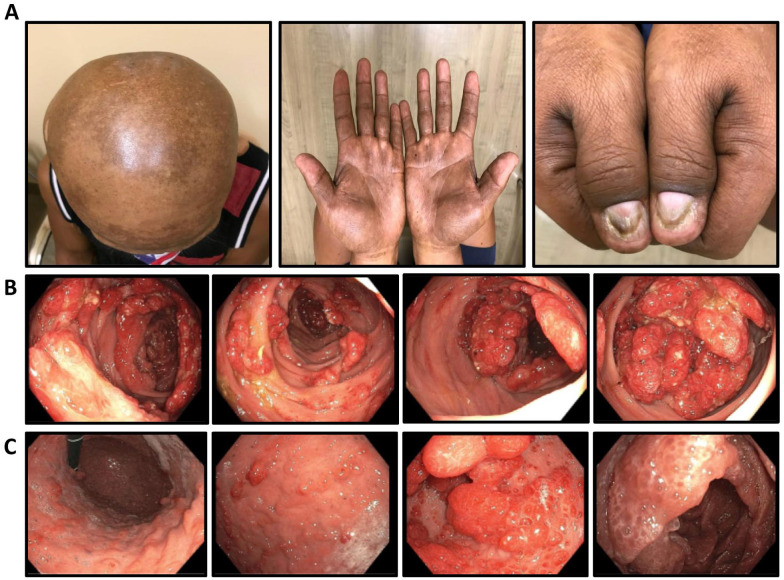

Figure 1.

Intestinal and extraintestinal clinical manifestation of the patient at presentation: (A) alopecia, hyperpigmentation of skin on the palms and scalp, and onychodystrophy in all digits most notably in thumbs. Multiple polyps accompanying mucosal edema and hyperemia were observed in the (B) stomach and (C) colon.

Physical examination was significant for alopecia, skin hyperpigmentation, and onychodystrophy. Complete blood count was significant for normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 12.4 g/dL. Comprehensive metabolic panel showed mild hypoalbuminemia (3.4 g/dL) with normal kidney function and liver enzymes. 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid, vasoactive intestinal peptide, and pancreatic elastase were normal. Stool culture, fecal examination for parasite, Giardia, and cryptosporidium immunoassay and serologies for HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis were all negative. Fecal calprotectin was elevated at 99 mcg/g.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy revealed multiple hyperemic polyps in the stomach, duodenum, terminal ileum, and colon (Figure 1B and C). Histological evaluation of gastric biopsies showed benign glandular mucosa with features of an inflammatory polyp. It was negative for intestinal metaplasia and Helicobacter pylori by immunoperoxidase stain. Duodenal biopsy showed benign glandular mucosa with dilated glands and mild chronic active inflammation with blunted intestinal villi. No evidence of dysplasia or malignancy was reported. Colon polyps were described as either tubular adenomas or inflammatory polyps. Genetic evaluation was negative for adenomatous polyposis coli mutation.

Given his endoscopic evaluation and clinical presentation, he was diagnosed with CCS and was started on prednisone 60-mg tablet once daily and azathioprine 50 mg daily. One month later, while he was only on prednisone 60 mg daily, his stool count decreased to 6 times a day; however, he still had abdominal pain. Multiple attempts to taper his prednisone dose lower than 20 mg a day led to flare of the symptoms. Two months later, he was started on infliximab (5 mg/kg at 0, 2, and 6 weeks as an induction dose, followed by 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks thereafter for maintenance therapy). The dose of azathioprine was increased to 150 mg daily. Following the induction regimen of infliximab, the patient reported significant clinical improvement. He stopped prednisone completely while continuing azathioprine 150 mg daily and infliximab 5 mg per kilogram every 8 weeks.

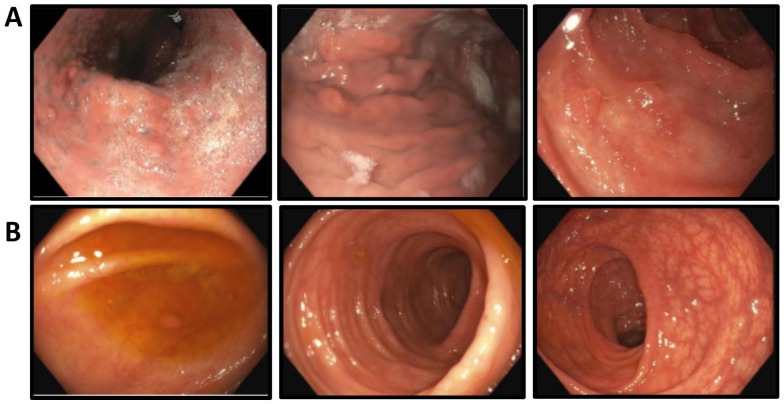

Gradually, his eyebrow, body hair, and nail beds regrew. Endoscopic evaluation 24 months after the initiation of infliximab showed significant regression of polyposis in the stomach and colon (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Follow-up endoscopic evaluation after treating with infliximab: Significant regression in both polyps’ size and number in the (A) stomach and (B) entire colon.

Discussion

Since the introduction of CCS in 1995, around 500 cases have been reported in the literature. It has been described as a disease of middle-age and male predominance. 9 The polyposis can involve the whole gastrointestinal tract with characteristic esophageal sparing. While the polyposis is typically hamartomatous, pathologic features of polyps can vary between hyperplastic, tubular adenomas, juvenile polyps, inflammatory polyps, and hamartomas polyps. 10 Gastrointestinal symptoms are often nonspecific and may mimic symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease. Ectodermal lesions including alopecia, skin hyperpigmentation, and onychodystrophy are often the clues that lead to a diagnosis. Early diagnosis is important because 5-year mortality is about 55% if it remains untreated. 11 At the present, there are no standardized treatments for CCS. It has been treated conventionally with extensive nutritional support and steroids, but emerging data show relapse of disease after steroid tapering. 12 Steroid-sparing immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine and azathioprine have been shown to be successful in induction and treatment maintenance in patients with steroid resistance.7,13 Recently, TNF-a inhibitors have attracted a lot of attention as expression of TNF-a was found to be high in intestinal mucosa of patients with CCS.14,15 Germline whole genome sequencing analysis of patients with CCS showed a mutation in the PRKDC gene, which can lead to higher expression of TNF-a and other cytokines and plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.16,17 To our knowledge, including our report, this is the fifth case that showed drastic clinical response to anti-TNF-a medication in patients with CCS. Here, we report a patient with partial response to steroid therapy and symptom recurrence during steroid tapering, whose disease got controlled after adding infliximab and azathioprine. In addition to clinical improvement in his appetite, weight, and ectoderm changes, we found endoscopic improvement in resolution of mucosal fold hypertrophy and polyposis. Although more studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of TNF-a inhibitors in treating CCS, considering a superior side effect profile, dramatic response, and possible role of TNF-a in the pathogenesis of the CCS, this treatment should be investigated as a possible first-line treatment.

Conclusion

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome may share features of familial adenomatous polyposis or inflammatory bowel disease. Careful evaluation is necessary to accurately diagnose CCS and prevent unnecessary colectomy. Although traditional immunosuppressive agents usually control symptoms of affected individuals, this case demonstrated that infliximab is effective in inducing clinical and endoscopic remission in CCS.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed Consent: Verbal informed consent was obtained from the patient for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Roham Salman Roghani  https://orcid.org/0009-0006-4479-6145

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-4479-6145

References

- 1.Murata K, Sato K, Okada S, Suto D, Otake T, Kohgo Y.Cronkhite-Canada syndrome successfully treated by corticosteroids before presenting typical ectodermal symptoms. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14(3):561-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slavik T, Montgomery EA.Cronkhite-Canada syndrome six decades on: the many faces of an enigmatic disease. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(10):891-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, et al. The Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. An analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1982;61(5): 293-309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ota S, Kasahara A, Tada S, et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome showing elevated levels of antinuclear and anticentromere antibody. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8(1):29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan RY, Wang XW, Xue LJ, et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps infiltrated with IgG4-positive plasma cells. World J Clin Cases. 2016;4(8):248-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sweetser S, Ahlquist DA, Osborn NK, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: support for autoimmunity. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(2):496-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamakawa K, Yoshino T, Watanabe K, et al. Effectiveness of cyclosporine as a treatment for steroid-resistant Cronkhite-Canada syndrome; two case reports. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016; 16(1):123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor SA, Kelly J, Loomes DE.Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: sustained clinical response with anti-TNF therapy. Case Rep Med. 2018;2018:9409732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dore MP, Satta R, Murino A, et al. Long-lasting remission in a case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2018; 2018:bcr2017223527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweetser S, Alexander GL, Boardman LA.A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome presenting with adenomatous and inflammatory colon polyps. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(8):460-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Zhang L, Yang Y, et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of a rare case and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(5):300060520922427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang D, Tang GD, Lai MY, et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with steroid dependency: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(14):3466-3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao EJ, Hyder SM, DeNucci TD, Fine S.A successful steroid-sparing approach in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6(3):1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu ZY, Sang LX, Chang B.Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: from clinical features to treatment. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2020;8(5):333-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinek J, Chvatalova T, Zavada F, Vankova P, Tuckova I, Zavoral M.A fulminant course of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Endoscopy. 2010;42(Suppl. 2):E350-E351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boland BS, Bagi P, Valasek MA, et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: significant response to infliximab and a possible clue to pathogenesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(5):746-748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathieu AL, Verronese E, Rice GI, et al. PRKDC mutations associated with immunodeficiency, granuloma, and autoimmune regulator-dependent autoimmunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(6):1578-1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]