Abstract

Background & Objectives

Autoimmune encephalitis (AIE) may present with prominent cognitive disturbances without overt inflammatory changes in MRI and CSF. Identification of these neurodegenerative dementia diagnosis mimics is important because patients generally respond to immunotherapy. The objective of this study was to determine the frequency of neuronal antibodies in patients with presumed neurodegenerative dementia and describe the clinical characteristics of the patients with neuronal antibodies.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, 920 patients were included with neurodegenerative dementia diagnosis from established cohorts at 2 large Dutch academic memory clinics. In total, 1,398 samples were tested (both CSF and serum in 478 patients) using immunohistochemistry (IHC), cell-based assays (CBA), and live hippocampal cell cultures (LN). To ascertain specificity and prevent false positive results, samples had to test positive by at least 2 different research techniques. Clinical data were retrieved from patient files.

Results

Neuronal antibodies were detected in 7 patients (0.8%), including anti-IgLON5 (n = 3), anti-LGI1 (n = 2), anti-DPPX, and anti-NMDAR. Clinical symptoms atypical for neurodegenerative diseases were identified in all 7 and included subacute deterioration (n = 3), myoclonus (n = 2), a history of autoimmune disease (n = 2), a fluctuating disease course (n = 1), and epileptic seizures (n = 1). In this cohort, no patients with antibodies fulfilled the criteria for rapidly progressive dementia (RPD), yet a subacute deterioration was reported in 3 patients later in the disease course. Brain MRI of none of the patients demonstrated abnormalities suggestive for AIE. CSF pleocytosis was found in 1 patient, considered as an atypical sign for neurodegenerative diseases. Compared with patients without neuronal antibodies (4 per antibody-positive patient), atypical clinical signs for neurodegenerative diseases were seen more frequently among the patients with antibodies (100% vs 21%, p = 0.0003), especially a subacute deterioration or fluctuating course (57% vs 7%, p = 0.009).

Discussion

A small, but clinically relevant proportion of patients suspected to have neurodegenerative dementias have neuronal antibodies indicative of AIE and might benefit from immunotherapy. In patients with atypical signs for neurodegenerative diseases, clinicians should consider neuronal antibody testing. Physicians should keep in mind the clinical phenotype and confirmation of positive test results to avoid false positive results and administration of potential harmful therapy for the wrong indication.

Cognitive dysfunction can be the presenting and most prominent symptom in patients with autoimmune encephalitis (AIE).1,2 In contrast to neurodegenerative diseases, patients with antibody-mediated encephalitis might benefit from immunotherapy and improve considerably.3,4 The presence of neuronal antibodies has been reported predominantly in rapidly progressive dementia (RPD).5,6 However, AIE can present less fulminantly and is therefore potentially missed, resulting in diagnosis and treatment delay or even misdiagnosis.7,8 We hypothesized that a small—but not insignificant—part of dementia syndromes is indeed caused by antibody-mediated encephalitis and underdiagnosed, withholding these patients' available treatments. The wish to diagnose every single patient with autoimmune encephalitis is in opposition with the risk for false positive tests.9 Therefore, we strictly adhere to confirmation of positive test results with 2 different test techniques. In this study, we describe the frequency of neuronal antibodies in a cohort of patients diagnosed with various dementia syndromes in a memory clinic. In addition, we present clues to improve clinical recognition of AIE in dementia syndromes.

Methods

Patients and Laboratory Studies

In this retrospective multicenter study, we tested for the presence of neuronal antibodies in serum and CSF samples from patients diagnosed with neurodegenerative dementia diagnosis, included earlier prospectively in established cohorts at 2 large Dutch academic memory clinics (Erasmus University Medical Center, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, location VUmc)10 between 1998 and 2016 (84% last 10 years). All patients fulfilled the core clinical criteria for dementia, as defined by the National Institutes of Aging-Alzheimer Association workgroups.11 Patients were classified into 4 subgroups (based on diagnostic criteria): Alzheimer dementia (AD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD; both behavioral variant and primary progressive aphasia [PPA]), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and other dementia syndromes.11-14 Rapidly progressive dementia was defined as dementia within 12 months or death within 2 years after the appearance of the first cognitive symptoms.15 Patients with vascular dementia were not included. Clinic information was retrieved from the prospectively collected data. A subacute deterioration was defined as a marked progression of symptoms in 3 months and a fluctuating course as a disease course fluctuating over a longer period (e.g., weeks to months; different from the fluctuations within a day as seen in some patients with DLB). Dementia markers were scored according to the reference values (per year and per center; included in Table 1).

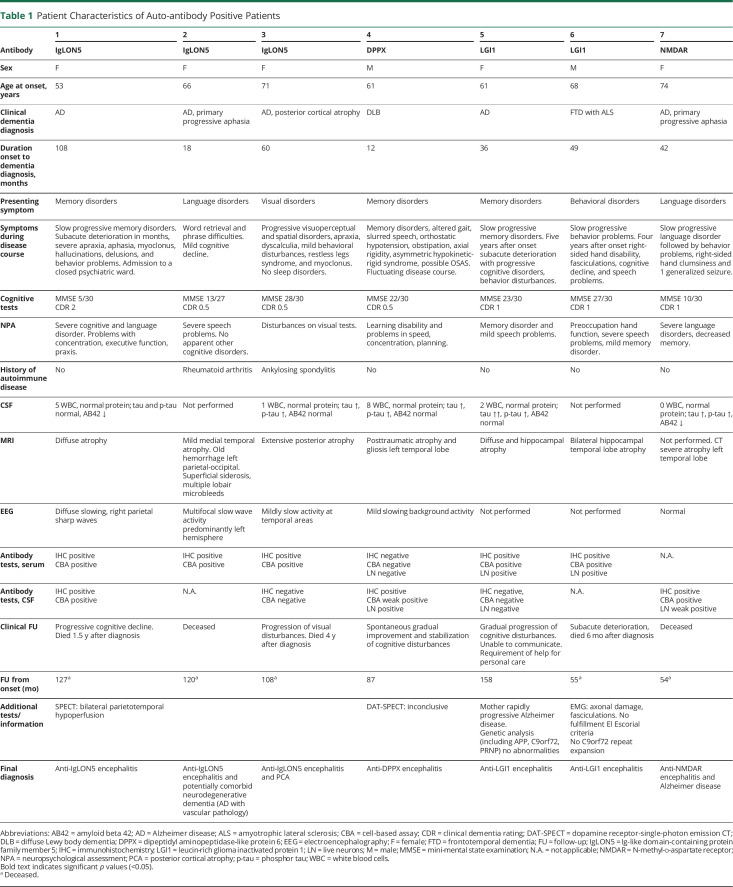

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics of Auto-antibody Positive Patients

All samples, stored in both cohorts' biobanks, were screened for immunoreactivity with immunohistochemistry (IHC), as previously described.16 Preferably, paired serum and CSF were tested for optimal sensitivity and specificity. Samples that were showing a positive or questionable staining pattern were tested more extensively using validated commercial cell-based assays (CBA) and in-house CBA (eTable 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A869). In addition, these samples were tested with live hippocampal cell cultures (LN).16,17 To ascertain specificity, only samples that could be confirmed by CBA or LN were scored as positive because there is a higher risk for false-positive test results in this population with a low a priori chance to have encephalitis.9,18 If IHC was suggestive for antibodies against intracellular (paraneoplastic) targets, this was explored by a different IHC technique.19 Anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO), voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC), or low titer glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies were not tested for because these are generally nonspecific at these ages and are not associated with dementia syndromes.

Antibody-positive patients were described exploratory and compared with a randomly selected antibody-negative group (ratio 1:4) matched for memory clinic, dementia subtype, sex, and age (±5 years). For these comparisons, medical records were additionally assessed for both the antibody-positive and antibody-negative patients. All antibody-positive patients were reviewed by a panel consisting of neurologists specialized in neurodegenerative (F.J., H.S., J.S.) or autoimmune diseases (J.V., P.S.S., M.T.), and a consensus classification of AIE vs AIE with a neurodegenerative dementia comorbidity was reached.

Statistical Analysis

We used IBM SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc) and Prism 8.4.3 (GraphPad) for statistical analysis. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using the Fisher exact test, the Fisher-Freeman-Halton test, or the Kruskal-Wallis test, when appropriate. For group comparisons, encompassing categorical data, we used the Pearson χ2 test or the Fisher-Freeman-Halton test, when appropriate. Continuous data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. All p-values were two-sided and considered statistically significant when below 0.05. We applied no correction for multiple testing, and therefore, p values between 0.05 and 0.005 should be interpreted carefully.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study was approved by The Institutional Review Boards of Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam and Amsterdam University Medical Center, location VUmc. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Data Availability

Any data not published within this article are available at the Erasmus MC University Medical Center. Patient-related data will be shared on reasonable request from any qualified investigator, maintaining anonymization of the individual patients.

Results

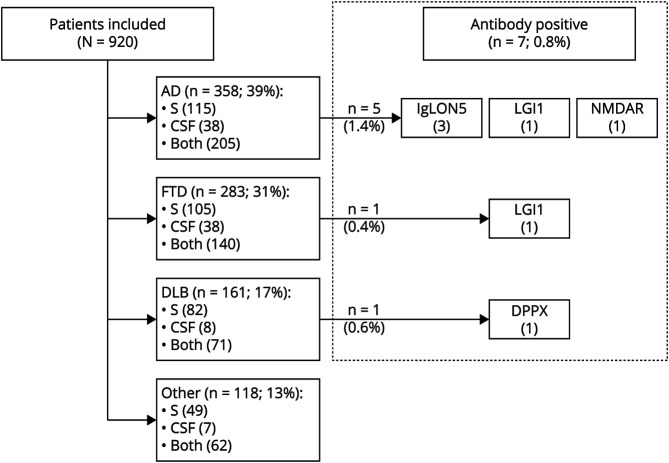

In total, 1,398 samples from 920 patients were tested (Figure; in 478, both CSF and serum [52%]). Three-hundred fifty-eight patients were classified as AD (39%), 283 FTD (31%), and 161 DLB (17%). The fourth subgroup with other dementia syndromes consisted of 118 patients (13%), including progressive supranuclear palsy (n = 48, 5%) and corticobasal syndrome (n = 29, 3%). The median age at disease onset was 62 years (range 16–90 years). Male patients were overrepresented (n = 542, 59%), and 60 patients (7%) fulfilled the criteria for rapidly progressive dementia (RPD; eTable 2, links.lww.com/NXI/A869).

Figure. Flowchart of Patient Inclusion With Antibody Results.

In total, 920 patients (1,398 samples) with a presumed neurodegenerative dementia syndrome were tested for the presence of neuronal antibodies in serum and CSF. Neuronal antibodies were detected in 7 patients (0.8%, 95% CI 0.2–1.3); five among the 358 Alzheimer disease patients. Subclassification of the ‘other’ group is provided in supplementary table eTable 2 (links.lww.com/NXI/A869). AD = Alzheimer disease; DLB = diffuse Lewy body dementia; DPPX = dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like protein 6; FTD = frontotemporal dementia; IgLON5 = Ig-like domain-containing protein family member 5; LGI1 = leucin-rich glioma inactivated protein 1; NMDAR = N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor; S = serum.

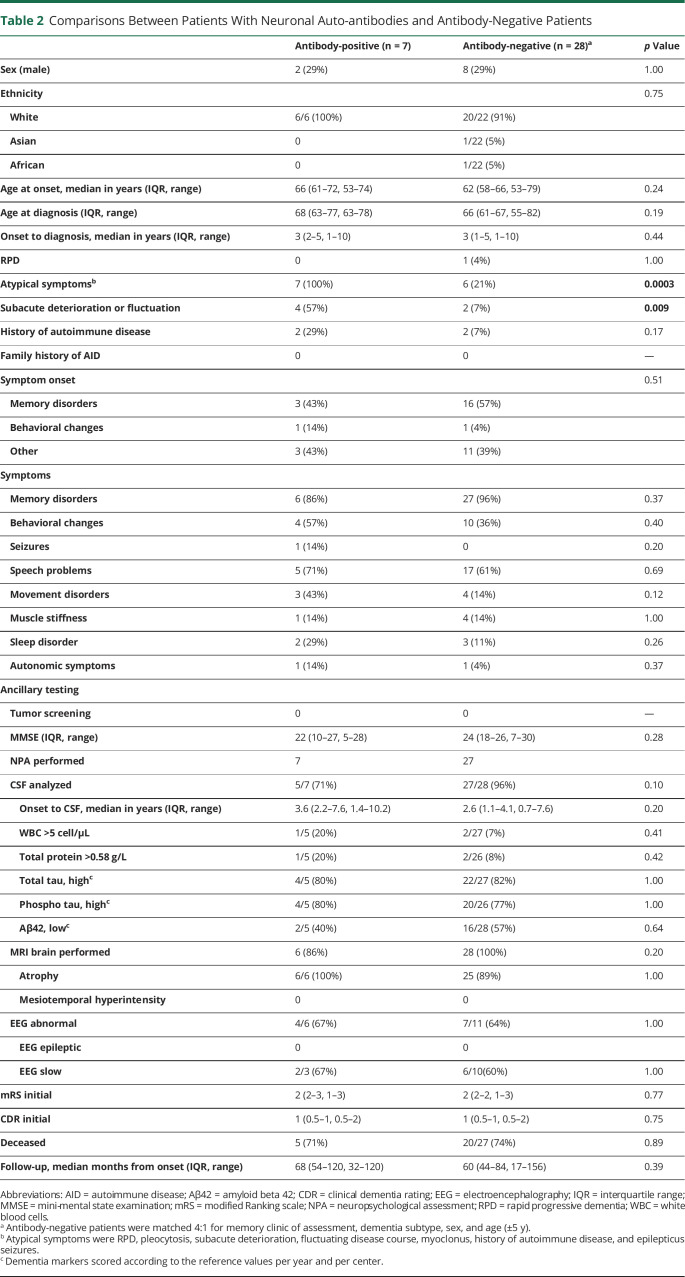

Neuronal antibodies were detected in 7 patients (0.8%; 5 in the AD group: 1.4%; Figure), including anti-IgLON5 (n = 3), anti-LGI1 (n = 2), anti-DPPX (n = 1), and anti-NMDAR antibodies (n = 1; Table 1). Among these 7, 4 patients were diagnosed retrospectively with an exclusive diagnosis of AIE, while 3 patients were classified to have AIE (anti-IgLON5 [n = 2] and anti-NMDAR antibodies [n = 1]) with a neurodegenerative dementia comorbidity. No patients with antibodies fulfilled the criteria for RPD, yet a subacute deterioration later in the disease was reported in 3 patients. Atypical clinical signs for neurodegenerative diseases were present in 7 of 7 antibody-positive patients (100% vs 21% in antibody-negative patients, p = 0.0003; Table 2). These included a subacute deterioration (n = 3), myoclonus (n = 2), a fluctuating disease course over months (n = 1), a history of autoimmune disease (n = 2), and epileptic seizures (n = 1; Table 1). Brain MRI of none of the patients demonstrated abnormalities suggestive for active AIE, in particular no hippocampal swelling nor increased T2-signal intensity. CSF pleocytosis was found in 1 patient. CSF biomarkers (t-tau, p-tau, and Aβ42) were tested in 5 of 7 patients, and t-tau and p-tau were increased in 4, while a low Aβ42 was seen in 2. Of note, only 1 patient had the combination of reduced Aβ42 and increased p-tau/t-tau, and was diagnosed with a comorbid AD. No patient received immunotherapy. Two patients still alive (1 anti-LG1, 1 anti-DPPX positive) were contacted but refused to visit our clinic to try very delayed immunotherapy trials. It is of interest that the patient with anti-DPPX antibodies showed spontaneous improvement of cognitive disturbances, atypical for a pure neurodegenerative disease.

Table 2.

Comparisons Between Patients With Neuronal Auto-antibodies and Antibody-Negative Patients

Compared with the patients without neuronal antibodies, subacute cognitive deterioration or fluctuating course was present more frequently (4/7 [57%] vs 2/28 [7%], p = 0.009). Although movement disorders (myoclonus) and autoimmune disorders were present in 2 of 7 patients each, this did not reach significance (Table 2).

Discussion

In this large, multicenter, cohort study consisting of patients with a presumed neurodegenerative dementia diagnosis, we show that a small, but clinically relevant proportion (0.8%) have neuronal antibodies. In this particular group, 4 of 7 antibody-positive patients presented with an atypical clinical course (subacute deterioration or fluctuating disease course), which is considered as a clinical clue (‘red flag’) for an antibody-mediated etiology of dementia.4 It is important that a fluctuating disease course was observed over a longer period (e.g., weeks or months) in AIE and should not be confused with shorter fluctuations of cognition or alertness (over the day) in DLB. Other known red flags, which we observed in these 7 patients, were myoclonus, epilepsy, pleocytosis, or a history of autoimmune disorders, as described earlier.1,4-6 Compared with antibody-negative patients, no significant difference was found related to these symptoms alone, probably due to the low number of positive patients and related low power. However, atypical clinical signs for neurodegenerative diseases together were seen significantly more frequently in the antibody-positive group. Within this cohort mostly devoid of patients with RPD, none of the antibody-positive patients fulfilled the criteria for RPD, nor ancillary testing showed specific signs for AIE in most patients. This implicates that AIE can resemble more protracted, progressive neurodegenerative dementia syndromes, as we reported earlier.1

Three antibody-positive patients had IgLON5 antibodies, which is a very rare and known to have heterogeneous (chronic) clinical manifestations, including pronounced sleep problems, cognitive dysfunction, and movement disorders.20,21 Misdiagnosis with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is reported, mainly associated with the preceding movement disorders. In addition, half of the patients have cognitive impairment of whom 20% fulfilled clinical criteria for dementia.21 It is of interest that IgLON5 disease shares features with neurodegeneration because autopsy studies showed tau deposits.22 However, there is a strong HLA association,20 and studies show that antibodies directly bind to surface IgLON5 on neurons and directly alter neuronal function and structure,23 suggesting a primary inflammatory disease.

In previous research, a notably higher frequency (14%) of neuronal antibodies in patients with dementia was reported by Giannocaro et al.24 The discrepancy with our test results is probably explained by differences in patient selection and antibody testing methodology. First, 30% of the patients in the cohort described by Giannocaro et al. demonstrated CSF inflammatory abnormalities, indicating a relatively high pretest probability of antibody-positivity compared with our study.24 A lack of CSF pleocytosis probably better represents the population of memory clinics. Second, the previous study exclusively tested serum by cell-based assay without confirmatory tests nor testing antibodies in CSF.24 We only considered antibody test results positive when confirmed by additional techniques to avoid suboptimal specificity and false-positive test results.9

Previous studies, including our own, suggested RPD as a relevant red flag for AIE,1,4,9,25 but we cannot determine this from our study based on the design of our study. We included patients at tertiary memory clinics without overt signs or symptoms suggestive for encephalitis. Therefore, the amount of patients with RPD included was very limited (7%), comparable with other large dementia cohort studies, as was the amount of patients with abnormal ancillary testing suggestive for AIE because this would have prompted a different approach than referral to a tertiary memory clinic. These patients with RPD and ancillary testing suggestive of AIE were not included in our study. Inclusion of those patients would have likely increased our rate of positivity.

The strength of our study is the large number of paired samples (serum and CSF combined) from a cohort with various presumed neurodegenerative diseases without AIE suspicion, representative for academic memory clinics. A limitation is the lack of neuropathologic data to support our findings and make diagnoses of neurodegeneration or inflammation definite. To confirm if the symptoms are related to the presence of antibodies, we tried to overcome this concern in different ways. First, the presence of antibodies in serum and CSF was confirmed by different techniques (cell-based assay, tissue immunohistochemistry, and cultured live neurons), indicating optimal test specificity. Second, afterward patients were thoroughly reviewed by a panel of neurologists specialized in neurodegenerative or autoimmune disease to detect atypical signs and symptoms related to AIE. This is a very large cohort of patients with dementia examined for the presence of neuronal antibodies. Nevertheless, an important limitation of this study is the small number of antibody-positive patients, underpowering the probability to identify significant differences between antibody-positive and antibody-negative patients. The low number of patients with RPD has probably added to this small number, and a prospective study including patients with RPD is recommended. Nevertheless, several probable red flags could be identified. Diagnosing AIE in patients with dementia is highly relevant because these patients might respond to immunotherapy. Therefore, clinicians should test for neuronal antibody in patients demonstrating red flags suggestive for an autoimmune etiology, if possible early in disease course. When profound temporal lobe atrophy already has developed, little effect is to be expected. Red flags identified in this study are subacute deterioration or fluctuating course. Other red flags described previously, we also see reflected in our study, are autoimmune disorders, myoclonus, seizures, and pleocytosis,1,4-6 Preferably, both serum and CSF should be tested and confirmed by additional techniques. Always consider the possibility of a false positive test result, especially when only using a single technique (like the commercial cell-based assay). If the clinical phenotype is atypical, confirmation in a research laboratory should be mandatory. The use of antibody panels is discouraged, especially including the paraneoplastic blots, because these are associated with higher risks of lack of clinical relevance.26 This caution is even more warranted for tests not associated with neurodegenerative syndromes, but with a history of nonspecificity, including VGKC (in the absence of LGI1 or CASPR2), VGCC, anti-TPO, and low-titer anti-GAD65.27-30 Further research should focus on improving clinical recognition of AIE in patients with dementia determining the effect of immunotherapy in this specific patient category and assessing the frequency of AIE in RPD.

In conclusion, we have shown that a clinically relevant, albeit small proportion of patients with a suspected neurodegenerative disease and nonrapidly progressive course have neuronal antibodies indicative of AIE.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all patients for their participation. The authors also thank Esther Hulsenboom and Ashraf Jozefzoon-Aghai for their technical assistance. M.W.J. Schreurs, F. Leypoldt, P.A.E. Sillevis Smitt, J.M. de Vries, and M.J. Titulaer of this publication are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Immunodeficiency, Autoinflammatory, and Autoimmune Diseases—Project ID No. 739543 (ERN-RITA; HCP Erasmus MC and University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein). H. Seelaar, J.C. van Swieten, and F.J. de Jong of this publication are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases—Project ID 73910. Research of the VUmc Alzheimer center is part of the neurodegeneration research program of Amsterdam Neuroscience. The Alzheimer Center VUmc is supported by Alzheimer Nederland and Stichting VUmc Fonds. The clinical database structure was developed with funding from Stichting Dioraphte.

Glossary

- AD

Alzheimer dementia

- AIE

autoimmune encephalitis

- CBA

cell-based assays

- DLB

dementia with Lewy bodies

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- LN

live hippocampal cell cultures

- PPA

primary progressive aphasia

- PSP

progressive supranuclear palsy

- RPD

rapidly progressive dementia

- VGCC

voltage-gated calcium channel

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

M.J. Titulaer was supported by an Erasmus MC fellowship and has received funding from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO, Veni incentive), ZonMw (Memorabel program), the Dutch Epilepsy Foundation (NEF 14-19 & 19-08), Dioraphte (2001 0403), and E-RARE JTC 2018 (UltraAIE, 90030376505). F. Leypoldt has received funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research (01GM1908A) and the Era-Net funding program (LE3064/2-1).

Disclosure

A.E.M. Bastiaansen reports no disclosures. R.W. van Steenhoven reports no disclosures. Research programs of Wiesje van der Flier have been funded by ZonMW, now, EUFP7, EU-JPND, Alzheimer Nederland, Hersenstichting CardioVascular Onderzoek Nederland, Health∼Holland, Topsector Life Sciences & Health, stichting Dioraphte, Gieskes-Strijbis fonds, stichting Equilibrio, Edwin Bouw fonds, Pasman stichting, stichting Alzheimer & Neuropsychiatrie Foundation, Philips, Biogen MA Inc, Novartis-NL, Life-MI, AVID, Roche BV, Fujifilm, and Combinostics. W.M. van der Flier holds the Pasman chair. W.M. van der Flier is recipient of ABOARD, which is a public-private partnership receiving funding from ZonMW (#73305095007) and Health Holland, Topsector Life Sciences & Health (PPP-allowance; #LSHM20106). All funding is paid to her institution. WF has performed contract research for Biogen MA Inc and Boehringer Ingelheim. All funding is paid to her institution. W.M. van der Flier has been an invited speaker at Boehringer Ingelheim, Biogen MA Inc, Danone, Eisai, WebMD Neurology (Medscape), and Springer Healthcare. All funding is paid to her institution. W.M. van der Flier is consultant to Oxford Health Policy Forum CIC, Roche, and Biogen MA Inc. All funding is paid to her institution. W.M. van der Flier participated in advisory boards of Biogen MA Inc and Roche. All funding is paid to her institution. W.M. van der Flier is a member of the steering committee of PAVE and Think Brain Health. W.M. van der Flier was an associate editor of Alzheimer, Research & Therapy in 2020/2021. W.M. van der Flier is an associate editor at Brain. Research of C. Teunissen was supported by the European Commission (Marie Curie International Training Network, Grant Agreement No. 860197 (MIRIADE)), Innovative Medicines Initiatives 3TR (Horizon 2020, Grant No. 831434), EPND (IMI 2 Joint Undertaking (JU) under Grant Agreement No. 101034344) and JPND (bPRIDE), National MS Society (Progressive MS alliance) and Health Holland, the Dutch Research Council (ZonMW), Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, The Selfridges Group Foundation, Alzheimer Netherlands, and Alzheimer Association. C. Teunissen is recipient of ABOARD, which is a public-private partnership receiving funding from ZonMW (#73305095007) and Health∼Holland, Topsector Life Sciences & Health (PPP-allowance, #LSHM20106). ABOARD also receives funding from Edwin Bouw Fonds and Gieskes-Strijbisfonds. C. Teunissen has a collaboration contract with ADx Neurosciences, Quanterix, and Eli Lilly, performed contract research or received grants from AC-Immune, Axon Neurosciences, Bioconnect, Bioorchestra, Brainstorm Therapeutics, Celgene, EIP Pharma, Eisai, Grifols, Novo Nordisk, PeopleBio, Roche, Toyama, and Vivoryon. She serves on editorial boards of Medidact Neurologie/Springer, Alzheimer Research and Therapy, and Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation and is an editor of a Neuromethods book Springer. She had speaker contracts for Roche, Grifols, and Novo Nordisk. E. de Graaff holds a patent for the detection of anti-DNER antibodies. M.M.P. Nagtzaam reports no disclosures. M. Paunovic reports no disclosures. S. Franken reports no disclosures. M.W.J. Schreurs reports no disclosures. F. Leypoldt has received speakers honoraria from Grifols, Roche, Novartis, Alexion, and Biogen and serves on an advisory board for Roche and Biogen. He works for an academic institution (University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein) which offers commercial autoantibody testing. P.A.E. Sillevis Smitt holds a patent for the detection of anti-DNER and received research support from Euroimmun. J.M. de Vries reports no disclosures. H. Seelaar reports no disclosures. J.C. van Swieten reports no disclosures. F.J. de Jong reports no disclosures. Y.A.L. Pijnenburg Research of Alzheimer center Amsterdam is part of the neurodegeneration research program of Amsterdam Neuroscience. Alzheimer Center Amsterdam is supported by Stichting Alzheimer Nederland and Stichting VUmc fonds. The chair of Wiesje van der Flier is supported by the Pasman stichting. M.J. Titulaer has filed a patent, on behalf of the Erasmus MC, for methods for typing neurologic disorders and cancer, and devices for use therein, and has received research funds for serving on a scientific advisory board of Horizon Therapeutics, for consultation at Guidepoint Global LLC, for consultation at UCB, for teaching colleagues by Novartis. MT has received an unrestricted research grant from Euroimmun AG and from CSL Behring. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosure.

References

- 1.Bastiaansen AEM, van Steenhoven RW, de Bruijn M, et al. Autoimmune encephalitis resembling dementia syndromes. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(5):e1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lancaster E, Lai M, Peng X, et al. Antibodies to the GABA(B) receptor in limbic encephalitis with seizures: case series and characterisation of the antigen. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(1):67-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12(2):157-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flanagan EP, McKeon A, Lennon VA, et al. Autoimmune dementia: clinical course and predictors of immunotherapy response. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(10):881-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geschwind MD, Tan KM, Lennon VA, et al. Voltage-gated potassium channel autoimmunity mimicking creutzfeldt-jakob disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(10):1341-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grau-Rivera O, Sanchez-Valle R, Saiz A, et al. Determination of neuronal antibodies in suspected and definite Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(1):74-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Late-onset anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Neurology. 2013;81(12):1058-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaig C, Graus F, Compta Y, et al. Clinical manifestations of the anti-IgLON5 disease. Neurology. 2017;88(18):1736-1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastiaansen AEM, de Bruijn M, Schuller SL, et al. Anti-NMDAR encephalitis in The Netherlands, focusing on late-onset patients and antibody test accuracy. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9(2):e1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Flier WM, Scheltens P. Amsterdam dementia cohort: performing research to optimize care. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(3):1091-1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2456-2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geschwind MD. Rapidly progressive dementia. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016;22(2 Dementia):510-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ances BM, Vitaliani R, Taylor RA, et al. Treatment-responsive limbic encephalitis identified by neuropil antibodies: MRI and PET correlates. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 8):1764-1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gresa-Arribas N, Titulaer MJ, Torrents A, et al. Antibody titres at diagnosis and during follow-up of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(2):167-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Martinez P, Titulaer MJ. Autoimmune psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(2):122-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Coevorden-Hameete MH, Titulaer MJ, Schreurs MW, et al. Detection and characterization of autoantibodies to neuronal cell-surface antigens in the central nervous system. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016;9:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabater L, Gaig C, Gelpi E, et al. A novel non-rapid-eye movement and rapid-eye-movement parasomnia with sleep breathing disorder associated with antibodies to IgLON5: a case series, characterisation of the antigen, and post-mortem study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):575-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaig C, Compta Y, Heidbreder A, et al. Frequency and characterization of movement disorders in anti-IgLON5 disease. Neurology. 2021;97(14):e1367–e1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelpi E, Hoftberger R, Graus F, et al. Neuropathological criteria of anti-IgLON5-related tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132(4):531-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landa J, Gaig C, Plaguma J, et al. Effects of IgLON5 antibodies on neuronal cytoskeleton: a link between autoimmunity and neurodegeneration. Ann Neurol. 2020;88(5):1023-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giannoccaro MP, Gastaldi M, Rizzo G, et al. Antibodies to neuronal surface antigens in patients with a clinical diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;96:106-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermann P, Zerr I. Rapidly progressive dementias - aetiologies, diagnosis and management. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022;18(6):363-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dechelotte B, Muniz-Castrillo S, Joubert B, et al. Diagnostic yield of commercial immunodots to diagnose paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(3):e701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Sonderen A, Schreurs MW, de Bruijn MA, et al. The relevance of VGKC positivity in the absence of LGI1 and Caspr2 antibodies. Neurology. 2016;86(18):1692-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muñoz Lopetegi A, Boukhrissi S, Bastiaansen A, et al. Neurological syndromes related to anti-GAD65: clinical and serological response to treatment. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(3):e696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattozzi S, Sabater L, Escudero D, et al. Hashimoto encephalopathy in the 21st century. Neurology. 2020;94(2):e217-e224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flanagan EP, Geschwind MD, Lopez-Chiriboga AS, et al. Autoimmune encephalitis misdiagnosis in adults. JAMA Neurol. 2023;80(1):30-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any data not published within this article are available at the Erasmus MC University Medical Center. Patient-related data will be shared on reasonable request from any qualified investigator, maintaining anonymization of the individual patients.