Abstract

Background

Pancreatic cancer has a dismal prognosis. One reason is resistance to cytotoxic drugs. Molecularly matched therapies might overcome this resistance but the best approach to identify those patients who may benefit is unknown. Therefore, we sought to evaluate a molecularly guided treatment approach.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical outcome and mutational status of patients with pancreatic cancer who received molecular profiling at the West German Cancer Center Essen from 2016 to 2021. We carried out a 47-gene DNA next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel. Furthermore, we assessed microsatellite instability-high/deficient mismatch repair (MSI-H/dMMR) status and, sequentially and only in case of KRAS wild-type, gene fusions via RNA-based NGS. Patient data and treatment were retrieved from the electronic medical records.

Results

Of 190 included patients, 171 had pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (90%). One hundred and three patients had stage IV pancreatic cancer at diagnosis (54%). MMR analysis in 94 patients (94/190, 49.5%) identified 3 patients with dMMR (3/94, 3.2%). Notably, we identified 32 patients with KRAS wild-type status (16.8%). To identify driver alterations in these patients, we conducted an RNA-based fusion assay on 13 assessable samples and identified 5 potentially actionable fusions (5/13, 38.5%). Overall, we identified 34 patients with potentially actionable alterations (34/190, 17.9%). Of these 34 patients, 10 patients (10/34, 29.4%) finally received at least one molecularly targeted treatment and 4 patients had an exceptional response (>9 months on treatment).

Conclusions

Here, we show that a small-sized gene panel can suffice to identify relevant therapeutic options for pancreatic cancer patients. Informally comparing with previous large-scale studies, this approach yields a similar detection rate of actionable targets. We propose molecular sequencing of pancreatic cancer as standard of care to identify KRAS wild-type and rare molecular subsets for targeted treatment strategies.

Key words: KRAS wild-type, targeted therapy, Archer, targeted sequencing, NGS

Highlights

-

•

Combining a 47-gene NGS panel and a gene fusion panel may yield similar results as broader NGS panels in pancreatic cancer.

-

•

In case of KRAS wild-type, the RNA-based fusion assay found an actionable fusion in 38.5%.

-

•

Targeted therapy of pancreatic cancer patients can yield exceptional responses of >9 months on treatment.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer, and especially pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), is a deadly disease and projected to become the second leading cause of cancer-related death by 2030.1 Even with the currently best systemic combination chemotherapies, such as folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) and gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel (Gem/nP), the median overall survival (mOS) in metastatic disease is 11.1 and 8.5 months, respectively.2,3 These numbers demonstrate the need for improvement. To improve the treatment options, defining subgroups by molecular alterations for personalized treatment options might help.

Several studies have characterized pancreatic cancer molecularly, indicating actionable alterations in up to 40% of patients.4, 5, 6 One major subgroup is patients with (germline) mutations in the BRCA2 DNA repair-associated 1 and 2 genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2), components of the DNA damage repair (DDR) pathway.7 These patients may benefit from poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors8,9 and platinum-based chemotherapy.10 Next to these specific alterations in pancreatic cancer, some tumor-agnostic treatments have been approved such as larotrectinib for NTRK fusion-positive tumors11,12 and immune checkpoint inhibition for tumors with high microsatellite instability or DNA mismatch repair deficiency (MSI-H/dMMR).13 In addition, comprehensive analyses of KRAS wild-type pancreatic cancer revealed further potential targets, i.e. gene fusions of BRAF (4.0%-6.6%), FGFR2 (5.2%-5.3%), ALK (2.6%), RAF1 (2.2%), RET (1.3%) and NRG1 (1.3%).14,15 For two NRG1 fusion-positive pancreatic cancer patients, targeted therapies demonstrated a therapeutic response of ∼5 months until disease progression.16 While this shows the therapeutic potential of a precision oncology approach in pancreatic cancer, systematic evidence supporting the use of molecular data in this disease is sparse. In that regard, the large-scale Know Your Tumor (KYT) registry demonstrated improved survival for molecularly matched therapies.17 Apart from this large-scale registry, studies investigating therapeutic consequences of molecular diagnostics exclusively in pancreatic cancer patients are sparse.

Therefore, we analyzed molecular data and their clinical consequence in pancreatic cancer patients who received molecular profiling at our center from 2016 to 2021. These data indicate that a sequential targeted DNA and RNA sequencing and matched treatment can improve the survival outcome in a subgroup of patients.

Materials and methods

Patient cohort and clinical data

We retrospectively included patients from September 2016 until data cut-off at the end of October 2021. Patients were eligible in case of a confirmed diagnosis of any pancreatic cancer and at least one molecular analysis at our center. We excluded patients with exclusively neuroendocrine neoplasms (neuroendocrine tumor/carcinoma) of the pancreas. We retrieved continuously documented clinical data from the electronic health information system of the University Hospital Essen. Further processing and data analysis were carried out retrospectively. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The local ethics committee approved this study (17-7340-BO). A waiver of informed consent was given to collect deidentified data retrospectively. This study followed the reporting guideline for case series.

Sequencing analyses

We extracted DNA and RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples with the Maxwell RSC DNA or RNA FFPE Purification Kit (Promega, Walldorf, Germany). The libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (DNA sequencing: GeneRead DNAseq Custom Panel V2, QIAgen, Hilden, Germany; RNA sequencing: FusionPlex CTL Panel, Archer, Boulder, CO) and sequenced on the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). We carried out the analysis of data with the CLC Genomics Workbench (QIAgen). All samples showed a concentration of at least 1 ng/μl.

The DNA sequencing panel covered hotspot regions or regions of interest of the following genes (details in Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101539): BRAF, EGFR, ERBB2, GNAQ, IDH1, IDH2, KIT, KRAS, MET, NRAS, PDGFRa, PIK3CA, SF3B1, AKT1, AKT2, ARID1A, ARID1B, ATM, BAP1, BCLAF1, BRCA1, BRCA2, GNA11, GNAS, KDM6A, MAP2K1, MAP2K2, MAPK1, MAPK3, MDM2, MLH1, MSH2, NF1, PALB2, PBRM1, PTEN, RAF1, RNF43, RPA1, SMAD4, SMARCA2, SMARCA4, SMARCB1, STK11, TSC1, TSC2, TP53.

The gene fusion analysis covered the following fusion partners (details in Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101539): ALK, AXL, BRAF, CCND1, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, MET, NRG1, NTRK1, NTRK2, NTRK3, PPARG, RAF1, RET, ROS1, THADA.

MSI testing

DNA dMMR or MSI-H was identified either by loss of MMR proteins assessed by immunohistochemistry (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) or by multiplex PCR of mononucleotides with at least two instable markers (NR-21, BAT-26, BAT-25, NR-24, MONO-27). Due to upcoming evidence with regard to programmed cell death protein 1 blockade, dMMR/MSI-H was regularly assessed since 2019 and only in selected patients before 2019.

Statistical analysis and clinical endpoints

We carried out all statistical and descriptive analyses using R (version 4.1.2, https://www.r-project.org/). Survival analyses and Kaplan–Meier curves were done with the survival (version 3.2.13) and survminer (version 0.4.9) R packages. Multivariate analysis was carried out using the Cox regression model. OS was the time from diagnosis until death from any cause.

Results

Cohort description

From September 2016 to October 2021, we identified and included 190 patients with any pancreatic cancer for mutational profiling. The median age at diagnosis was 59 years; 81 patients were female (42.6%). The majority of these patients had stage IV pancreatic cancer at diagnosis (103/190, 54.2%) and 90% (171/190) had histologically confirmed PDAC. The remaining patients had periampullary carcinoma (9/190, 4.7%), acinar cell carcinoma (2/190, 1.1%) or mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma (1/190, 0.5%). Of 190 samples, 114 were obtained from the primary tumor, by either biopsy (n = 56) or resection (n = 58). The 76 samples from secondary sites were most often obtained from the liver (n = 51) or the peritoneum (n = 13) (Table 1). Only a small fraction of metastases were resected (n = 9). The median number of received systemic therapies was 2 (range 0-8). All patients, who received any targeted therapy, had received at least one systemic therapy before the targeted therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of this cohort and sample information (n = 190 patients)

| Period | September 2016-October 2021 |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range), years | 59 (36-86) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 81 (42.6) |

| Male | 109 (57.4) |

| UICC stage at diagnosis, n (%) | |

| I | 7 (3.7) |

| II | 49 (25.8) |

| III | 21 (11.1) |

| IV | 103 (54.2) |

| Not available | 10 (5.3) |

| Initial treatment, n (%) | |

| Resection | 75 (39.5) |

| Palliative chemotherapy | 114 (60.0) |

| Not available | 1 (0.5) |

| Histology, n (%) | |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) | 178 (93.4) |

| Periampullary carcinoma | 9 (4.7) |

| Acinar cell carcinoma | 2 (1.1) |

| Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas (MANEC) | 1 (0.5) |

| Origin of samples, n (%) | |

| Primary tumor | 114 (60.0) |

| Secondary site | 76 (40.0) |

| Secondary sites of samples, n (%) | |

| Liver | 51 (67) |

| Peritoneum | 13 (13.1) |

| Lung | 7 (9.2) |

| Bone | 3 (3.9) |

| Distal lymph node | 2 (2.5) |

The PDACs include one sarcomatoid carcinoma and one squamous carcinoma. Four of the PDACs were undifferentiated. Proportions might not sum up to 100% as a result of rounding.

UICC, International Union Against Cancer (Union Internationale Contre le Cancer).

Mutational landscape

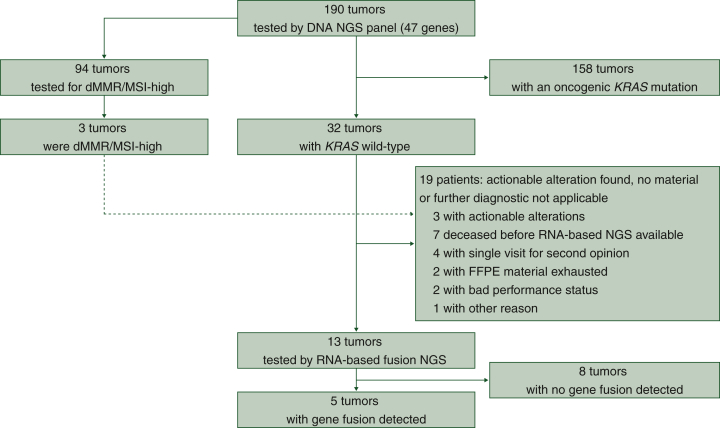

To determine actionable alterations, we carried out a stepwise approach investigating routinely collected FFPE material. As initial procedure, a customized DNA-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) 47-gene panel enriched for genes of KRAS downstream signaling and chromatin modifiers was carried out (Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101539, Figure 1). The most frequently identified mutations were KRAS (83.2%), TP53 (61.6%), SMAD4 (7.9%), ARID1A (7.9%) and BRCA2 (5.8%) (Figure 2A). Given the existing KRAS(G12C)-directed inhibition approaches, we evaluated the KRAS mutational spectrum. Of 158 patients with KRAS-mutated pancreatic cancer, we identified 8 patients with KRASG12C (8/158, 5.1%), while KRASG12D (66/158, 41.8%) was the most frequent KRAS mutation (Figure 2B). In addition, we assessed 94 tumors (49.5%) for MSI-H or DNA dMMR status. Of 94 patients, 3 patients had a tumor with MSI-H/dMMR (3/94, 3.2%).

Figure 1.

Patient selection and diagnostic work-up.

The dashed line describes one patient who received targeted therapy because of dMMR/MSI-H. Therefore, that sample was not further analyzed.

dMMR/MSI-H, deficient mismatch repair/high microsatellite instability; FFPE, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded; NGS, next-generation sequencing.

Figure 2.

Mutational landscape.

(A) Oncomap depicting mutations of 190 patients, including histology and microsatellite/mismatch repair status. (B) Subtypes of KRAS mutations (one patient had two KRAS mutations).

dMMR, deficient mismatch repair; MANEC, mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma; MMR, mismatch repair; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stability; pMMR, proficient mismatch repair.

Notably, we identified 32 patients with KRAS wild-type status (16.8%). To detect driver alterations not covered by DNA-based targeted NGS, we carried out RNA-based sequencing acknowledging the increasingly reported gene fusions. RNA-based NGS could be carried out in 13 cases (13/32, 41%). If the RNA-based sequencing was not carried out, the most frequent reasons were that the fusion panel had not been established at our site when the patient presented (n = 7) or only one single visit at our center for second opinion (n = 4). Three samples were not analyzed because alternative driver alterations were known: EGFR mutation and MSI-H/dMMR in one patient each. The third tumor had an up-regulation of ERBB3 [analyzed by whole-exome sequencing (WES) within the NCT/DKTK MASTER program18]. For the remaining 13 patients, we had sufficient material to carry out RNA-based sequencing. The sequencing revealed eight patients without a gene fusion and five patients with a therapeutically actionable gene fusion (5/13, 38.5%). The gene fusions were NOS1AP-NTRK1, TNS3-BRAF, FGFR2-CREB5, ERC1-RET and PDZRN3-RAF1.

DDR, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and epigenetic pathway alterations are among the most frequent driver alterations in PDAC. For this reason, we clustered subgroups based on the DNA panel sequencing. Most patients (163, 85.8%) had at least one mutation in the MAPK pathway. Alterations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT serine/threonine kinase (AKT) pathway were found in 32 patients (16.8%). The SWI/SNF complex plays an important role in chromatin remodeling with potential therapeutic implications. In our cohort, 39 patients (20.5%) had a mutation in genes encoding subunits of the SWI/SNF complex. In recent years, new insights enabled targeting the DDR pathway.8,10 In our cohort, the DDR pathway was affected in 28 patients (14.7%), with BRCA2 (5.8%, two patients had two BRCA2 mutations) and BRCA1 (3.7%) as the most frequently altered genes. Considering the continuous progress in drug development, these pathways are or may become relevant targets in the future.

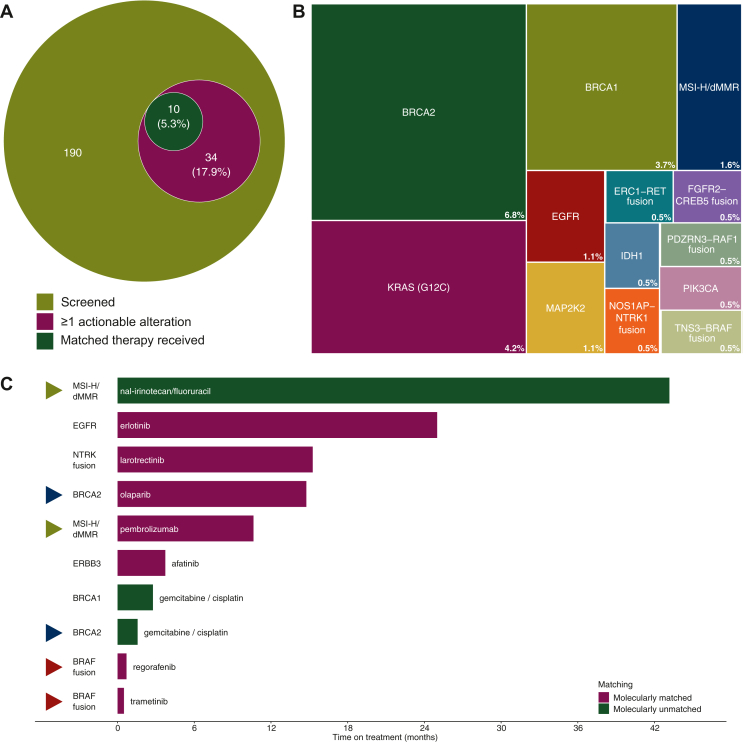

Therapeutic consequences and exceptional responders

Next, we evaluated these alterations for molecularly informed clinical decision making. We identified 42 actionable alterations in 34 patients (34/190, 17.9%, Figure 3A and B). Of these 34 patients, 24 patients did not receive a targeted therapy based on the molecular findings, although we could identify 15 patients with a BRCA1/2 mutation and another 6 patients with a KRASG12C mutation. Reasons for non-treatment were that (i) patients were not eligible for a study (n = 9), (ii) the drug was not available (n = 6), (iii) patients had a bad performance status (PS) (n = 3) or (iv) were treated in first line or without evidence of disease at data cut-off (n = 6). Treatment recommendations were proposed by a team of oncologists with expertise in molecular medicine (before mid-2019) and since mid-2019 by a newly formed molecular tumor board at our Comprehensive Cancer Center. Finally, 10 patients received at least one proposed treatment (10/34, 29.4%). Four patients received therapies within clinical trials. Of these, three patients received only the study drug and therefore treatment data are not shown here. One of these four patients also received another targeted therapy outside of a clinical trial which we included here. To estimate the efficacy, we defined a time on treatment of ≥9 months as an exceptional response because Gem/nP and FOLFIRINOX achieve a median progression-free survival (PFS) between 5.5 months3 and 6.4 months.2

Figure 3.

Actionable alterations and treatment implications.

(A) Venn diagram from patients screened to patients treated with matched therapy. (B) Actionable alterations identified in our cohort. White numbers mean the percentage of patients with this alteration related to all patients. (C) Swimmer’s plot of seven patients treated with matched therapies. If a patient received two matched therapies, the corresponding bar is marked with a triangle of same color. Data from patients in clinical trials are not shown.

Of seven patients receiving the proposed treatment, four (57%) had an exceptional response of >9 months on treatment (Figure 3C, additional clinical data on these patients provided in Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101539).

One patient with an EGFR (p.E746_S752delinsV) mutation received erlotinib for 25 months and one patient with an NTRK fusion was treated with larotrectinib for 15.2 months. Maintenance therapy with olaparib in a germline BRCA2-mutated tumor led to 14.7 months on treatment. A patient with an MSI-H/dMMR tumor received pembrolizumab for 10.6 months. Interestingly, the patient showed durable disease control over 43 months under nal-irinotecan and fluorouracil treatment following pembrolizumab therapy. Regorafenib and trametinib did not yield substantial benefit in the case of a detected BRAF fusion.

We also recommended a targeted therapy to another three patients. Unfortunately, the PS of these patients worsened rapidly, and the treatment was not given or we could not determine the efficacy.

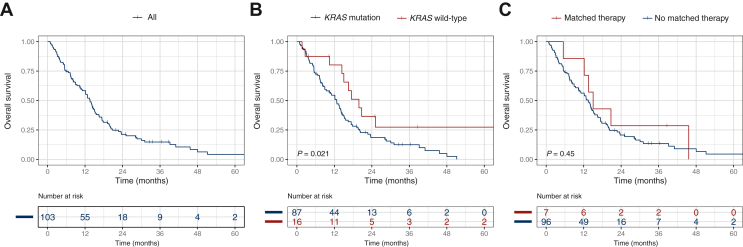

KRAS wild-type is independently associated with better overall survival

To estimate the effect of our approach, we assessed the OS regarding possible prognostic factors. Considering all patients, the mOS was 17.8 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 15.6-23.5 months]. For better comparison, we next analyzed only patients with stage IV tumors. The mOS for patients with stage IV pancreatic cancer was 13.6 months (95% CI 11.1-15.6 months) (Figure 4). The group of patients with KRAS wild-type had a significantly superior OS with an mOS of 19.9 versus 12.7 months in patients with KRAS-mutated pancreatic cancer [hazard ratio for death (HR) 0.46, 95% CI 0.24-0.90, P = 0.024]. TP53 mutational status did not have a significant impact on survival (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.49-1.2, P = 0.21) (Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101539). Next, we determined the OS in the subgroup of patients who had an actionable alteration and received the matched therapy. The mOS was 13.4 months without and 15.0 months with the matched therapy, but we could not identify a significant survival improvement (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.32-1.67, P = 0.449). We hypothesized that the site of metastases might influence the survival. Indeed, patients with hepatic metastasis had a significantly worse OS with 12.7 versus 23.5 months without hepatic metastasis (HR 2.06, 95% CI 1.17-3.65, P = 0.013), whereas other metastatic sites (lung, bones, peritoneal) did not influence the OS (data not shown). As expected, younger age (<65 years, HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.37-0.92, P = 0.02) and good PS (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 0-1, HR 0.36, 95% CI 0.2-0.66, P = 0.00094) were associated with a survival advantage.

Figure 4.

Overall survival and prognostic value of KRAS status and matched therapy. Kaplan–Meier estimates for overall survival of all stage IV patients (A), based on KRAS status (B) and receipt of matched therapy (C).

Next, we carried out multivariate analysis for OS and included all significant factors from the univariate analyses. We confirmed KRAS wild-type, better PS and no hepatic metastasis as independent prognosticators for OS (KRAS wild-type: HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.23-0.90, P = 0.023; PS 0/1: HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.28-0.97, P = 0.04; no hepatic metastasis: HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.26-0.84, P = 0.011) (Supplementary Figure S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101539). In contrast, age was no independent prognostic factor (HR 1.52, 95% CI 0.96-2.38, P = 0.072). These data indicate that KRAS mutational status is an important prognostic parameter, and patients with KRAS wild-type pancreatic cancer benefit from further molecular characterization and matched treatment.

Discussion

To improve clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer patients, we here evaluated a sequential approach for molecular profiling to guide therapeutic decisions after standard-of-care therapy. Using a dedicated gene panel with a high coverage focusing on the MAPK pathway, PI3K/AKT pathway and chromatin modifiers, we could not detect targetable mutation for the majority of patients. A key reason is that KRAS is a strong driver rendering other targetable alterations less probable. In our series we found KRAS mutations in 84% of cases, which is in line with a very recent large molecular analysis of over 16 000 PDAC patients, in which oncogenic KRAS mutations were reported in 85%.15 These frequencies are slightly lower than what has often been reported previously. For a rational diagnostic step-up approach, initial screening for a small selection of relevant genes, especially KRAS and BRCA1/2, was implemented in our center. In case of KRAS wild-type, we carried out RNA panel sequencing with one known, targetable gene fusion partner. This approach enables the detection of unknown gene fusion partners and consequently of therapeutically relevant gene fusions but might miss some translocations. For instance, NTRK fusions despite KRAS mutations are rare but not mutually exclusive.19 Due to the rare incidence of gene fusions despite KRAS mutation, it seems a rational way of assessment in pancreatic cancer patients. Another major advantage of this approach is the usage of FFPE material that is clinically feasible and applicable by more caregivers than whole-genome sequencing (WGS) or transcriptome analyses.

Pancreatic cancer patients with KRAS wild-type benefited from further molecular characterization as we found a potentially targetable gene fusion in almost 40% of our patients. For the other 60% of patients, we could not determine an alternative driver. On the one hand, this is due to pre-analytical reasons such as insufficient material or death before fusion panel sequencing was conducted. On the other hand, our targeted sequencing approach may miss other potentially targetable fusions due to the selection of fusion partners. In the group of KRAS wild-type and fusion-negative tumors, WGS might help to detect driver alterations and possible treatments. However, other studies have not provided convincing evidence for such an approach given the lack of other identified driver alterations.

In contrast, tumors with an oncogenic KRAS mutation remain difficult to treat. Sotorasib and adagrasib, two KRAS(G12C) inhibitors, showed efficacy in lung cancer,20,21 and sotorasib could also show a modest efficacy in pancreatic cancer patients.22 However, their frequency is low with 5.0% (8/158) in our and 0.95% (29/3051) and 1.6% in another series.15,23 The higher frequency in our center may have resulted from referred patients as we could offer a study for this specific KRAS mutation. As this is a minor subgroup of pancreatic cancer patients and with modest efficacy, other specific KRAS inhibitors for the largest subgroups in pancreatic cancer, KRAS(G12D) and KRAS(G12V), would have great therapeutic potential and are under development.24,25

Another relevant subgroup is patients whose tumors feature alterations of the DDR pathway. In the POLO trial, patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations benefited from the PARP inhibitor olaparib after platinum-based chemotherapy in terms of PFS.8 Although demonstrating a favorable PFS and superiority in some secondary endpoints (for instance, time to first subsequent cancer therapy or death), maintenance therapy with olaparib did not achieve a superior OS.9 For patients with BRCA1/2 or PALB2 alterations, gemcitabine and cisplatin yielded an mOS of 15.5 months,10 exceeding common first-line therapies such as FOLFIRINOX (mOS 11.1 months)2 and Gem/nP (mOS 8.5 months).3 As this subgroup comprises a relevant fraction of patients, analysis of DDR pathway genes and evaluation of platinum-based and PARP inhibitor approaches are an important current and future task for diagnostic and therapeutic evaluation in pancreatic cancer patients.

By indirect comparison with large-scale studies, our approach yields similar results.17,26,27 In the KYT cohort, 46 of 1082 patients with pancreatic cancer and molecular profiling received a matched therapy (4.3%).17 Two pan-cancer studies evaluated the clinical utility of NGS to determine targeted treatments. The MET1000 cohort included 42 pancreatic cancer patients (of 1015 patients with available NGS data). Four of these 42 patients (2 PDAC, 2 neuroendocrine tumor, each 4.8%) received a targeted therapy and were <5 months on targeted treatment.26 The NCI-MATCH trial included 334 pancreatic cancer patients (of 5540 patients screened) and 14 of these received targeted therapy (14/334, 4.2%).27 In our study, 5.3% (10/190) of patients were treated according to molecular profile and recommendation. This is similar to the three mentioned studies and underscores the rationale of sequential diagnostics.

Our study bears some limitations. Firstly, the major limitation is the retrospective design that impairs the completion of missing data and identification of potential confounders. Logically, we could not offer later approved drugs to patients who had already deceased. Secondly, as our study includes only single-center data, it might have an institutional bias regarding therapy and prognosis. Thirdly, the comparison of our approach to other published studies is indirect. Although we cannot provide a direct comparison, we consider this indirect comparison sound enough to state that similar results can be achieved with a smaller panel.

In the future, the list of actionable alterations will likely extend and thereby increase the odds to offer targeted therapies to pancreatic cancer patients. We here used a considerably small panel focusing on selected pathway, followed by additional testing dependent on KRAS status for further alterations, especially fusions. While this stepwise approach lacks the width of large targeted NGS panels or WES approaches, the frequency of identified actionable alterations and matched therapy approaches and the fraction of patients benefiting are highly similar to previous larger trials such as the KYT registry.17

Overall, our presented approach shows that a dedicated NGS panel diagnostic may achieve similar results as extensive sequencing approaches in large-scale studies. Thus, molecularly informed treatment decisions should be implemented in clinical care beyond established treatment lines to extend therapeutic options for selected pancreatic cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding

JTS is supported by the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) [grant numbers #405344257/SI 1549/3-2, SI1549/4-1], by the German Cancer Aid [grant numbers #70112505/PIPAC, #70113834/PREDICT-PACA] and by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) [grant number 01KD2206A/SATURN3]. The West German Cancer Center receives grant support from the Oncology Center of Excellence Program of German Cancer Aid [grant number 110534], and as a partner site of the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), it receives support from the German federal and state governments. The funding sources had no influence on the analysis and interpretation of data or on the contents of the manuscript.

Disclosure

MW: honoraria and advisory role: Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda; research funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda. SK: discloses honoraria (self) from Amgen, Merck, BMS, MSD, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier and Lilly; honoraria (institution) from Amgen, Merck, Roche and Lilly; advisory/consultancy roles with Amgen, Merck, BMS, MSD, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Novartis and Lilly; research grants/funding (self) from Merck, BMS, Roche and Lilly; research grants/funding (institution) from BMS, Roche, Merck and Lilly. MS: consultant (compensated): Amgen, AstraZeneca, BIOCAD, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Takeda; stock ownership: none; honoraries for CME presentations: Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Novartis; research funding to institution: AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers-Squibb. HUS: Targos Molecular Pathology, Inc. (employment); Roche, Novartis Oncology, MSD, BMS, Pfizer, ZytoVision, Zytomed (honoraria); AstraZeneca, Agilent, Molecular Health, MSD (advisory boards); Novartis Oncology (research funding—outside of this study). JTS: honoraria (consultant or for continuing medical education presentations): AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Immunocore, MSD Sharp Dohme, Novartis, Roche/Genentech and Servier; institutional research funding: Abalos Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisbach Bio and Roche/Genentech; he holds ownership and serves on the Board of Directors of Pharma15, all outside the submitted work. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author JTS. The data are not publicly available due to information that could compromise research participant privacy/consent.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Rahib L., Smith B.D., Aizenberg R., Rosenzweig A.B., Fleshman J.M., Matrisian L.M. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conroy T., Desseigne F., Ychou M., et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Hoff D.D., Ervin T., Arena F.P., et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguirre A.J., Nowak J.A., Camarda N.D., et al. Real-time genomic characterization of advanced pancreatic cancer to enable precision medicine. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(9):1096–1111. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Raphael B.J., Hruban R.H., et al. Integrated genomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(2):185–203.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aung K.L., Fischer S.E., Denroche R.E., et al. Genomics-driven precision medicine for advanced pancreatic cancer: early results from the COMPASS trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(6):1344–1354. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waddell N., Pajic M., Patch A.M., et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518(7540):495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golan T., Hammel P., Reni M., et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):317–327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kindler H.L., Hammel P., Reni M., et al. Overall survival results from the POLO trial: a phase III study of active maintenance olaparib versus placebo for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(34):3929–3939. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Reilly E.M., Lee J.W., Zalupski M., et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase II trial of gemcitabine and cisplatin with or without veliparib in patients with pancreas adenocarcinoma and a germline BRCA/PALB2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(13):1378–1388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drilon A., Laetsch T.W., Kummar S., et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion–positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):731–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Reilly E.M., Hechtman J.F. Tumour response to TRK inhibition in a patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma harbouring an NTRK gene fusion. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl 8):viii36–viii40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le D.T., Uram J.N., Wang H., et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philip P.A., Azar I., Xiu J., et al. Molecular characterization of KRAS wild type tumors in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(12):2704–2714. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umemoto K., Yamamoto H., Oikawa R., et al. The molecular landscape of pancreatobiliary cancers for novel targeted therapies from real-world genomic profiling. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(9):1279–1286. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heining C., Horak P., Uhrig S., et al. NRG1 fusions in KRAS wild-type pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(9):1087–1095. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pishvaian M.J., Blais E.M., Brody J.R., et al. Overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer receiving matched therapies following molecular profiling: a retrospective analysis of the Know Your Tumor registry trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):508–518. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horak P., Heining C., Kreutzfeldt S., et al. Comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic analysis for guiding therapeutic decisions in patients with rare cancers. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(11):2780–2795. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen M.J., Zhang A., Bavi P., et al. Molecular characterisation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with NTRK fusions and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2023;76(3):158–165. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2021-207781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skoulidis F., Li B.T., Dy G.K., et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2371–2381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jänne P.A., Riely G.J., Gadgeel S.M., et al. Adagrasib in non–small-cell lung cancer harboring a KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(2):120–131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strickler J.H., Satake H., George T.J., et al. Sotorasib in KRAS p.G12C–mutated advanced pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):33–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2208470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nassar A.H., Adib E., Kwiatkowski D.J. Distribution of KRASG12C somatic mutations across race, sex, and cancer type. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(2):185–187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2030638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koltun E, Cregg J, Rice MA, et al. Abstract 1260: first-in-class, orally bioavailable KRASG12V (ON) tri-complex inhibitors, as single agents and in combinations, drive profound anti-tumor activity in preclinical models of KRASG12V mutant cancers. Experimental and Molecular Therapeutics. Proceedings of the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021; April 10-15, 2021 and May 17-21, 2021. Philadelphia, PA: American Association for Cancer Research; 2021(81):1260. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2021-1260. [DOI]

- 25.Hallin J., Bowcut V., Calinisan A., et al. Anti-tumor efficacy of a potent and selective non-covalent KRASG12D inhibitor. Nat Med. 2022;28(10):2171–2182. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cobain E.F., Wu Y.M., Vats P., et al. Assessment of clinical benefit of integrative genomic profiling in advanced solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(4):523–533. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flaherty K.T., Gray R.J., Chen A.P., et al. Molecular landscape and actionable alterations in a genomically guided cancer clinical trial: National Cancer Institute Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(33):3883–3894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.