ABSTRACT

Background and objectives: Multiple reforms aimed at improving the Chinese population’s health have been introduced in recent years, including several designed to improve access to innovative drugs. We sought to review current factors affecting access to innovative drugs in China and to anticipate future trends.

Methods: Targeted reviews of published literature and statistics on the Chinese healthcare system, medical insurance and reimbursement processes were conducted, as well as interviews with five Chinese experts involved in the reimbursement of innovative drugs.

Results: Drug reimbursement in China is becoming increasingly centralized due to the removal of provincial pathways, the establishment of the National Healthcare Security Administration and the implementation of the National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL), which is now the main route for drug reimbursement in China. There is also an increasing number of other channels via which patients may access innovative treatments, including various types of commercial insurance and special access. Health technology assessment (HTA) and health economic evidence are becoming pivotal elements of the NRDL decision-making process. Alongside the optimization of HTA decision making, innovative risk-sharing agreements are anticipated to be increasingly leveraged in the future to optimize access to highly specialized technologies and encourage innovation while safeguarding limited healthcare funds.

Conclusions: Drug public reimbursement in China continues to align more closely with approaches widely used in Europe in terms of HTA, health economics and pricing. Centralization of decision-making processes for public reimbursement of innovative drugs allows consistency in assessment and access, which optimizes the improvement of the Chinese population’s health.

KEYWORDS: National Reimbursement Drug List, innovative drug access, pricing, reimbursement, decision making, health technology assessment, risk-sharing

Introduction

Improving the health of Chinese citizens is a priority objective for the Chinese government [1,2] This is reflected by increased public investments in healthcare in recent years. Total healthcare expenditure (i.e., government funding, social health insurance and out-of-pocket spending by patients) reached RMB 7.23 trillion in 2020, representing 7.12% of GDP [3], compared to RMB 4.06 trillion in 2015 (6.0% of GDP). This increase has largely been driven by a rise in spending via social health insurance schemes, while out-of-pocket spending has remained stable during this period, accounting for approximately 30% of total healthcare expenditure [3,4–8].

Social health insurance schemes in China mainly comprise the basic medical insurance (BMI), which includes the basic medical insurance for urban employees (BMIUE) and the basic medical insurance for urban and rural residents (BMIURR). Together, these two schemes cover more than 95% of the population [2]. The BMIUE is funded by employers and employees, both of whom make contributions as per the employee’s salary. On the other hand, funds within the BMIURR are derived from contributions paid by urban and rural residents, as well as by the government [9]. In addition, social health insurance schemes in China include commercial health insurance, i.e., insurance that is privately funded via premiums paid by beneficiaries. Expenditure on commercial health insurance has increased steadily over time, from 6% in 2015 to 11% in 2019 [10].

Drugs reimbursed under the BMI schemes are listed on the National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL). NRDL drugs are reimbursed at different rates according to whether they are included in Category A (essential and affordable drugs) or Category B (innovative and relatively more expensive drugs) [11]. For patients who meet a particular reimbursement threshold (which in many provinces is set at the local average per capita annual disposable income), additional reimbursement may be available via Critical Illness Insurance schemes, funded within the BMI schemes [12,13].

While patients may access innovative treatments via multiple channels, the NRDL remains the main route of drug access and reimbursement for most patients in China. The process for revising drugs listed on the NRDL has undergone multiple and rapid reforms in recent years. In this context, we aimed to characterize pathways for access to innovative medicines in China, as well as current factors and future trends that may affect pricing and reimbursement, with a focus on recent developments in NRDL appraisal and decision-making processes.

Methods

Desk research

Relevant literature and statistics on the Chinese healthcare system, medical insurance, and reimbursement processes were identified via secondary desk research carried out between January and August 2021. Literature published in English or Chinese was obtained from sources including CNKI, EMBASE, PubMed and Google Scholar databases. We also searched for government reports and statistics via the National Health Commission (NHC), National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA) and the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA). Keywords searched included ‘China’, ‘Chinese healthcare system’, ‘Chinese health insurance system’, ‘National Reimbursement Drug List’, ‘reimbursement’, ‘health technology assessment’, ‘drug price’, ‘price negotiation’, ‘innovative medicine/treatment/drug/pharmaceutical’, and combinations of these terms.

Experts interviews

As a second step, primary research was conducted via semi-structured interviews (see Supplementary material for interview guide) conducted between March and June 2021 with five Chinese experts who have been involved in NRDL appraisal and decision-making processes. Interviews sought to validate the findings of the secondary desk research and to provide insights for filling information gaps and anticipating future trends.

One-hour interviews were carried out via teleconference in either Chinese or English. Experts included individuals from a range of professional backgrounds, including a specialist in HTA, a health economist, a pharmacist, and two clinicians. A discussion guide was developed covering topics on public and commercial health insurance schemes, HTA and health economics, pricing and reimbursement policies and usual practices, the NRDL drug appraisal and decision-making process, and future trends in these topics.

Findings from desk research and expert interviews were consolidated and are described as current factors affecting access to innovative medicines in China; factors affecting HTA, decision making and pricing; and future trends in HTA, decision-making and pricing.

Results

Access to innovative medicines

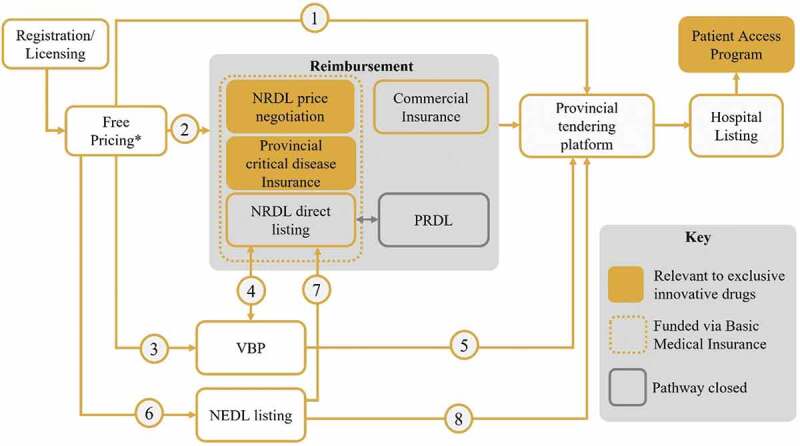

Multiple pathways exist in China to provide patients with access to drug treatments via hospitals. These pathways are described in Figure 1. Furthermore, access to drug treatments is influenced by key decision makers and follows regulations implemented by recent reforms.

Figure 1.

Drug access routes via hospitals in China. (1) Tendering of self-paid non-reimbursed drugs (2) Exclusive innovative drugs can enter the NRDL through price negotiation, other drugs can enter through direct listing (3) Patent-expired originators and generics that have passed consistency evaluations enter national VBP (4) Success in national VBP was one of the criteria to be considered for inclusion on the NRDL in 2020. NRDL products also have streamlined VBP (5) Hospitals are required to prioritize the usage of VBP drugs (6) the criteria for NEDL listing are urgent need and clinical necessity (7) Listing on the 2018 NEDL was one of the criteria to be considered for inclusion on the NRDL in 2020 (8) Hospitals are required to prioritize the usage of NEDL drugs. *Prices can be freely set at market entry. NEDL – National Essential Drug List; NRDL – National Reimbursement Drug List; PRDL – Provincial Reimbursement Drug List; VBP – Volume-based procurement.

Key decision makers for access to drug treatments

Three national-level decision makers influence access to innovative drugs in China, including the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA), the National Health Commission (NHC) and the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA). The NMPA is the regulatory body responsible for marketing authorization and monitoring drug standards. The NHC is responsible for public health services and for planning resource allocations, and also formulates national-level drug policies, including the National Essential Drug List (NEDL) – the list of essential, affordable drugs that meet basic healthcare needs. The NHSA is responsible for managing BMI schemes and for the NRDL process (review of manufacturer submissions and price negotiations).

Drug registration pathways

The NMPA describes four pathways to marketing approval in China [14,15], with review timelines for marketing authorization varying based on the level of priority granted. Of these four pathways, three are priority pathways with accelerated approval procedures. These pathways, their accessibility criteria, and timelines are detailed in Table 1. The priority approval pathway may apply to drugs used to treat rare diseases. Rare diseases in China are specified in a government-compiled list. Even if a disease is considered rare in the EU and US, it still is not a rare disease in China if it is not on this list [Experts insights].

Table 1.

| Pathway | Eligible drugs | Review timeline (days) |

|---|---|---|

| Priority approval pathway | Drugs with urgent clinical shortage used to prevent and treat major infectious diseases, rare diseases, etc. New types or new dosage forms of pediatric drugs Vaccines for disease prevention and control Drugs included in the breakthrough drug procedure Drugs that meet the conditional approval criteria Drugs that meet other unspecified priority approval situations |

70 to 130 |

| Breakthrough therapeutic drug pathway | Drugs used to prevent and treat diseases that are severely life-threatening, or which affect HRQoL, and for which there is no current effective prevention or treatment with significant clinical benefits | 130 |

| Conditional approval pathway | Drugs used for the prevention/treatment related to public health incidents (e.g., vaccines) | 130 |

| Standard approval pathway | All other drugs that cannot be categorized as outlined above | 200 |

HRQoL – Health-related Quality of Life; NMPA – National Medical Products Administration

Timelines for marketing approval should range from 70 to 200 days, depending on the pathway. However, actual approval timelines are often longer. For example, in 2019, the average time for approving imported new drugs was 341 days; this approval was further delayed in the case of domestic new drugs (514 days) [16]. Nonetheless, the number of drugs benefiting from priority review increased rapidly from 7 to 82 between 2016 and 2018 [17].

To accelerate approval and usage of innovative drugs, a regional pilot scheme in Hainan province, the Hainan Boao Lecheng International Medical Tourism Pilot Zone, has been operating since 2016. The Hainan Medical Zone Implementation Plan allows in-zone healthcare institutions to streamline the import of small amounts of urgently needed overseas drugs not yet approved by the NMPA. Furthermore, the in-zone real-world data generated using these drugs can be used to support the NMPA drug approval process and may significantly shorten registration timelines [18]. Chinese government introduced from March 2022 a new policy applicable to ‘Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area’, in which selected medical institutions in Guangdong province have been designated to use drugs and medical devices that have been listed in Hong Kong and Macao and that have urgent clinical need[19]. Up to April 2023, 23 innovative drugs and 13 medical devices are urgently imported and used in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. This policy is helpful to explore the registration of international innovative drugs according to real-world data and accelerate the listing process in the future.

Major reforms of the NRDL

Considerable reforms in HTA, pricing and reimbursement have been implemented since 2000 (Figure 2). The pace and scope of these reforms have increased considerably since 2015. Major reforms included the establishment of a national payer, responsible for public health coverage and reimbursement, the NHSA; the abolition of government price control measures affecting a majority of drugs, whereby price ceilings for drugs included in the NRDL were removed, with the exception of certain psychotropic and narcotic medications [20] the implementation of volume-based-procurement (VBP) for off-patent originators and generics; and the introduction of price negotiations for reimbursement of high-cost innovative drugs. These reforms, together with the removal of provincial reimbursement drug lists (PRDLs), rendered processes governing access to drugs in China highly centralized.

Figure 2.

Timeline of major reforms in pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement since 2000. *A number of products remain subject to price control, including drugs designated as Class I psychoactive drugs and narcotic drugs. Timeline is not to scale. Dashed lines indicate where the timeline has been contracted for brevity. NEDL – national essential drug list; NHSA – National Healthcare Security Administration; NRDL – National Reimbursement Drug List; PRDL – provincial reimbursement drug list.

Commercial insurance

Commercial health insurance in China supplements BMI schemes by covering indications and/or drugs that are not covered by the NRDL [Experts insights]. In this regard, many patients use commercial health insurance to cover out-of-pocket expenses, a practice that is being promoted by the state and commercial health insurance companies [Experts insights].

Consequently, premiums for commercial health insurance increased substantially in recent years, leading to revenues reaching RMB 800 billion in 2020 [21]. However, the amount paid out in claims represents only around a quarter of those revenues (~RMB 200 billion) [Experts insights]. Unfortunately, co-payments for patients are often high (~RMB 15,000 to 20,000), and not all patients can benefit from this type of insurance [Experts insights].

Commercial health insurance and pharmaceutical companies may implement pricing agreements that include discounts on sales or free-of-charge products [Experts insights]. Although implementation of more innovative risk-sharing schemes is seen to be complex, they may become possible in some instances with innovative high-cost technologies [Experts insights].

Further to traditional commercial health insurance, city-customized commercial medical insurance is a new type of commercial insurance supported by local governments [22], and which is available to those covered under the (public) BMI schemes. Under City Welfare Insurance, beneficiaries pay low premiums (often between RMB 60 and RMB 120 yearly) but reimbursement can be substantial, with most insurers setting reimbursement ceilings of RMB 2 million to RMB 3 million per year [22]. However, annual deductibles under this type of insurance are high, at around RMB 20,000 [22]. City Welfare Insurance can be used to cover the costs of in-patient and out-patient hospital care, as well as fees for specific high-cost drugs [22].

Critical Illness Insurance

Where patients meet a particular reimbursement threshold, they may be eligible for additional reimbursement under their local Critical Illness Insurance scheme, funded within the BMI.

Critical illness insurance was first implemented in 2012 [12]. As the Central Government provided only guidelines and a general framework for its implementation, the schemes are implemented differently in different regions [12,13]. In many regions, patients are eligible to receive additional reimbursement under the critical illness insurance scheme if their out-of-pocket expenses are more than the annual average disposable income per capita in the local area [12,13]. However, in some provinces the threshold for eligibility is below per capita disposable income, while in other provinces, the threshold may be equal to or exceed annual average disposable income per capita [12].

In some provinces, Critical Illness Insurance schemes may also provide additional reimbursement for patients with specific ‘major’ chronic diseases. For example, patients with diseases such as cancer, myocardial infarction and diabetes may be reimbursed at higher rates relative to patients with other diseases [Experts insights]. Reimbursement rates may exceed 90% for ‘major’ diseases [Experts insights]. Additional reimbursement may also be provided for patients with rare diseases (e.g., those included China’s list of rare diseases). In Zhejiang, for example, Critical Illness Insurance provides reimbursement for high-cost drugs to treat Gaucher’s disease and phenylketonuria [22].

Patient Access Programs (PAPs)

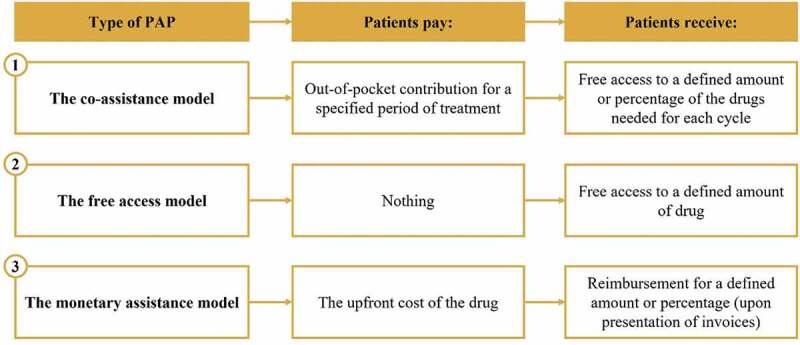

PAPs, which are donations through charitable organizations, also constitute a key pathway to accessing innovative drugs for Chinese patients. According to Jiang et al. (2020) [23], there are three main models of PAPs in China, from the free-access model to the partly paid out-of-pocket model (Figure 3). PAPs have become more common in China since the first one was initiated in 2003, particularly in recent years [23]. During the period of 2015 to 2019, between 15 and 29 PAPs were launched each year [24–27]. Very often, such programs are implemented by pharmaceutical companies from marketing authorization, before NRDL listing, to stimulate private sales before public ones.

Figure 3.

Types of Patient Access Programs in China, according to Jiang et al. (2020). PAP – patient access program.

Other pathways to access

In some situations, where a required drug is not on the NRDL, hospitals acquire the small amounts needed to treat individual patients on a temporary basis: ‘Once the clinician submits the procurement application, a small procurement plan can be generated through the pharmacy department, the drug procurement department, or the dean in charge.’ [Experts insights]

HTA decision making, reimbursement and price negotiation

The National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL)

The NRDL is the main pathway for pharmaceutical reimbursement in China, aimed at improving affordability of drug treatments. Since price negotiations were formally introduced in 2017, the average price reduction achieved during annual negotiations has ranged from 44% to 61%.

Entry into the NRDL is competitive. In 2020, 704 drugs passed the initial review, but only 162 were shortlisted for negotiation, of which 119 products were successful, giving an overall success rate of 17%.

Successful candidates significantly benefit from inclusion on the NRDL, reflected in sales volumes growth due to increased drug access and usage. For the 36 drugs listed on the NRDL after negotiation in 2017, sales reportedly increased from RMB 20.4 billion in 2017 (before inclusion on NRDL) to RMB 38.6 billion in 2019 [28]. A similar tendency was observed for the 17 oncology drugs listed on the NRDL after negotiation in 2018. Their sales increased from RMB 4.7 billion in 2017 (before inclusion on NRDL) to RMB 12.4 billion in 2019 [29].

Drugs with a successful price negotiation are listed on Category B of the NRDL. The reimbursement rate for drugs in Category B is around 50%, compared to 70%, 80% or 90% for drugs in Category A [Experts insights]. Patients who exceed a particular reimbursement threshold (defined at a regional level) may also benefit from Critical Illness Insurance as described above.

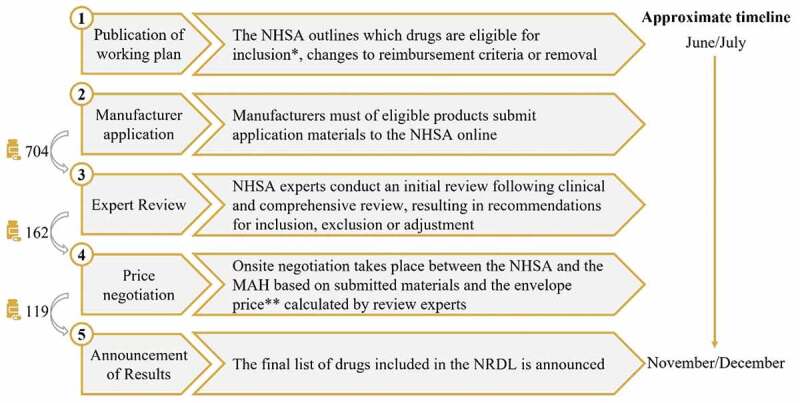

The NRDL submission process in 2020

The NRDL assessment process can be divided into five steps, as outlined in Figure 4. In 2020, the working plan [30] for the NRDL stated seven conditions for new drugs/indications to be considered for inclusion (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The NRDL 2020 process and timeline, showing the number of drugs included at each step.

*The working plan stated seven conditions for new drugs/indications to be considered for inclusion: treatments for COVID-19; drugs on the 2018 NEDL; drugs with marketing approval issued before August 17th, 2020, that are designated as urgently needed new overseas drugs, encouraged generics or encouraged pediatric drugs; drugs included in the second round of value-based purchasing; new generic drugs that received marketing approval between Jan 1st, 2015 and August 17th, 2020; drugs with major changes in indications and functions approved between Jan 1st, 2015 and August 17th, 2020; and drugs included in 5 or more PRDLs prior to Dec 31st, 2019.

**The envelope price calculated by NHSA’s review experts constitutes the NHSA’s target reimbursement price for the drug. MAH – marketing authorization holder; NHSA – National Healthcare Security Administration; NRDL – National Reimbursement Drug List; NEDL – National Essential Drug List; PRDL – provincial reimbursement drug list.

For drugs already included on the NRDL, reimbursement conditions could be re-assessed for potential adjustments if the contract period had expired, or if the drug had a higher price than other drugs within the same therapeutic area and was consuming a large portion of healthcare funds. In this context, price re-negotiations are usually informed by real-world evidence on drug’s sales volume and impact on healthcare budget [Experts insights].

Finally, currently listed drugs were eligible for delisting if they have been revoked, withdrawn or their risks outweighed their benefits.

In 2020, a key change occurred on the NRDL process. For the first time, manufacturers of eligible drugs could submit an application to the NHSA for assessment, while previously it was possible only after drugs were nominated by clinical experts.

Review of submitted dossiers

The first step of the submission review process involves an initial review of submitted material by clinical experts. Possible outcomes are ‘pass’, ‘additional material required’ or ‘fail’. In 2020, 704 drugs passed the initial review.

The following step involves a comprehensive review of submitted material by a group of professionals including clinical experts, pharmacists, health economists and specialists in healthcare funding (referred to as the ‘Comprehensive Group’). In a process called ‘Priority Setting’, the Comprehensive Group selected drugs that were eligible for price negotiation, prioritizing drugs according to their potential additional clinical benefits and ability to address high unmet medical needs. Other considerations of interest during prioritization include comparator price and health economic considerations, level of innovation, as well as considerations related to supply chain, and ease of drug usage and patient management.

In 2020, 162 drugs were selected for negotiation, and were further reviewed by clinical experts. An important consideration in the assessment for NRDL listing and which directly impacts pricing and health economic outcomes is the selection of a comparator, which was carried out by the clinical experts. This is generally based on the following criteria: 1) the comparator is currently on the NRDL; 2) it is recognized being the most effective treatment option; 3) it is the most frequently used option in clinical practice [Experts insights]. This third option is of particular interest when there is no consensus on the most effective option on the NRDL [Experts insights]. Also, in certain situations, comparator selection can identify the option on the NRDL which has the lowest price [Experts insights].

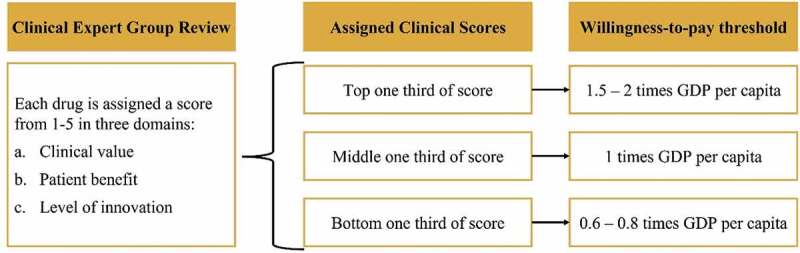

Following their review, clinical experts assigned a score to each drug (on a scale of one to five) according to its clinical value, patient benefit and level of innovation. The assigned scores impacted the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold used during economic evaluation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Willingness-to-pay thresholds. Selected according to the scores assigned to drugs by clinical experts, and used to inform the envelope price for NRDL negotiations. [Experts insights].

*In specific situations, such as for end-of-life treatments and treatments with high clinical benefits for rare/ultra-rare diseases, higher WTP thresholds may be considered, or treatment may be listed without referring to such thresholds [Experts insights]. NRDL – National reimbursement drugs list; GDP – gross domestic product.

Determining the reimbursement price

Before initiating negotiations with drug manufacturers, health economic experts (40 in 2020) and specialists in healthcare funding (12 in 2020) calculate an envelope price for each drug under assessment. Both groups work in parallel without interaction before comparing their conclusions for a decision on the envelope price. China Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations (2020) [30] should be followed during this step. Cost- effectiveness/utility analysis or cost-minimization analysis can be submitted with appropriate justification [Experts insights]. In the absence of head-to-head comparison, validated methods for indirect treatment comparison could be presented, again with appropriate justification [Experts insights].

For calculating the envelope price from a health economic perspective, the score given to each drug under the assessment by the clinical experts determines the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) WTP threshold to be considered [Experts insights] (Figure 5). Generally, drugs are categorized into three groups of WTP threshold according to whether the score assigned by the clinical experts falls into the upper, middle, or lower one third of all scores [Experts insights] (Figure 5). Importantly, in specific situations, such as for end-of-life treatments and treatments with high clinical benefits for rare/ultra-rare diseases, higher WTP thresholds may be considered, or treatment may be listed without referring to such thresholds [Experts insights].

In order to calculate the envelope price from a healthcare funding perspective, the annual increase rate of the basic health insurance fund is first defined. Then, the envelope price is calculated based on the budget impact analysis, giving consideration to the specific rate of budget increase for the therapeutic area [Experts insights].

The final envelope price per treatment is derived from health economic and budget impact assessments, while considering patient access programs and international reference pricing (IRP), especially the lowest treatment prices across the 12 reference markets: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom, plus (one of) New Zealand or Turkey [Experts insights]. Envelope prices are kept confidential and unsealed when negotiation starts. Negotiation usually includes 2 rounds of offer from manufacturers. After the first round, the authorities give the manufacturer a clear signal about the envelope price if the manufacturer’s bid does not meet their expectations [31]. Negotiations are often negative if the second offer is ~ 15% higher than the envelope price [31]. However, exceptions may apply for products with high clinical value or score (as per the clinical experts). In this context, the NHSA negotiation experts may give multiple opportunities (i.e., more than two) and hints to the manufacturers to facilitate offer-making and to eventually achieve a successful negotiation [31].

Apart from disagreements between the envelope price and manufacturers’ offer, negotiations can also fail due to inadequate clinical data presented during the application process or limited social need for the drug in question [Experts insights].

In terms of price transparency, it is possible for manufacturers to request that the negotiated net price of a drug remains confidential [Experts insights]. This is of interest for IRP. However, even if the NHSA keeps the negotiated net price confidential, it can be determined at the hospital or patient level [Experts insights].

In 2020, negotiations were successful for 119 drugs (Figure 4), of which 96 were newly included on the NRDL and 23 were listed before 2020 but renewed their contract [32]. In 2021, 94 drugs were successfully negotiated, of which 74 were newly included and 20 renewed their contract [33].

Repricing of NRDL drugs

The prices of drugs included in the NRDL are renegotiated two years after entry, with the original price having been calculated based on projections [Experts insights]. During renegotiation, the real-world evidence on sales volume and healthcare budget impact during the first two years of reimbursement will be used to inform the negotiation of a new price [Experts insights].

The price of a drug may also change if a generic drug appears during the price renegotiation [Experts insights]. In this case, the new price will fall to the price of the generic drug. If a generic drug appears after the re-negotiation, both the drug under negotiation and the generic drug should go through the volume-based procurement process whether the generic drug is in the NRDL or not.

After NRDL entry: hospital listing and reimbursement prices

According to interviewed experts, hospital listing after NRDL listing is not straightforward, and not every hospital is able to include all NRDL drugs on its formulary [Experts insights]. In many situations, this is because hospitals are covering different populations, and doctors have different prescribing habits in different regions [Experts insights]. Therefore, for hospital listing, the hospital’s Pharmaceutical Affairs Committee seeks doctors’ opinions and selects frequently used drugs for the hospital formulary [Experts insights].

Regarding hospital reimbursement of NRDL drugs, it is believed that manufacturers may strategically reduce drug costs at the regional level in order to increase market shares, which may occur through group purchasing organizations and may be negotiated based on sales quantities [Experts insights]. Based on regulation, NRDL negotiated prices at national level should be respected. This is leading to alternative arrangements benefiting hospitals such as agreements on quantities or provision of additional services [Experts insights].

Additional pricing insights and future trends in reimbursement for innovative treatments

Regarding the reimbursement of additional indications for NRDL-listed drugs, experts noted that the process is similar to listing new drugs. Applying a different price per indication for drugs on the NRDL is currently not possible. As such, reimbursement of an additional indication for a drug may likely lead to a decrease in the reimbursement price, because adding a new indication will lead to increased utilization [Experts insights]. However, it is believed that, in the future, sub-prices for different indications may be considered during negotiations to fairly recognize the different value of drugs in different indications [Experts insights]. It is possible that this would be implemented in the form of a weighted-average of the prices for all indications [Experts insights], i.e., a price that considers the level of utilization per indication.

In the current context of the NRDL, it is not possible to implement risk-sharing agreements such as financial caps, volume agreements or pay-by-performance agreements [Experts insights]. Nevertheless, it is believed by some that such types of agreement should be implemented by the Chinese government in the future, especially in the context of expensive and highly specialized technologies [Experts insights], in order to support budget sustainability while managing treatment effectiveness uncertainty. To this end, the NHSA should dedicate a team to evaluate such innovative payment models, which will require the support of solid data [Experts insights]. In the meantime, decision making should be aligned with best practices in HTA and health economics, appropriately acknowledging treatment value with pricing to encourage innovation, while ensuring budget sustainability with appropriate pricing agreements [Experts insights].

Discussion

Although multiple access pathways have developed in recent years, the NRDL remains the key route for access to innovative drugs for patients in China. In this context, the NRDL has been repeatedly reviewed and optimized by the NHSA, striving to provide patients with affordable access to these innovative treatments, while also preserving access to basic care via sustainable BMI schemes.

NRDL practices and policies are expected to continue to evolve in coming years, in continued alignment with those established in many European countries. In this way, it is expected that decision making, and pricing will be more influenced by systematic implementations and considerations of HTA and health economic evidence, and that innovative pricing approaches will be implemented in the form of risk-sharing agreements. All these practices will facilitate the increasing arrival of highly specialized technologies on the market and encourage innovation while supporting budget sustainability.

Following recent reforms, public reimbursement of innovative drugs in China is becoming increasingly centralized. This is demonstrated by the recent abolition of PRDLs. Despite this, this research demonstrates opportunities for manufacturers to offer further discounts at the regional or hospital level in ways that do not affect prices, for example in the format of volume agreements, or by providing other services.

Sparse publicly available information related to the NRDL review and update process represents a limitation of this research, especially with regard to specific criteria for decision making and the degree to which different types of HTA and health economic evidence are considered. These gaps were supplemented by interviewing five experts in China with direct experience of advising NRDL national decision makers.

Overall, the factors supporting the determination of a positive decision for national reimbursement in China are similar in some aspects to many other national HTA systems in the world, taking into account the level of innovation and magnitude of additional clinical and cost-effectiveness benefits versus standard of care, and this in context of the level of unmet medical needs and the ability of the intervention to address it. The budget impact is in addition a key driver, taking into account the price of comparators and the annual increase rate of the basic medical insurance funds needed for the reimbursement of the new intervention. Considerations related to supply chain, and ease of drug usage and patient management are also influential. There could be less rigidity for a positive decision in some specific situations such as where a clinical benefit from an intervention is seen for a rare/ultra-rare condition, as well as in certain cases for end-of-life treatments. At hospital level, doctors’ opinions and preferences, and the ease of drug usage and patient management, are factors which would support hospital listing and access to patients after an NRDL positive decision for reimbursement. In this context, special arrangements with hospitals such as agreements on quantities or provision of additional services may help obtaining hospital listing.

The NRDL and other healthcare practices and policies are highly dynamic and evolving in China. Although this research seeks to investigate future trends, additional assessments are essential to follow future public and private payer initiatives supporting access to innovative treatments in China, which is key to improving the Chinese population’s health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Xue Chen, a former employee of Amaris Consulting Ltd., assisted on the conduction of the expert interviews.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Pierre Fabre Group.

Disclosure statement

Bérengère Macabeo, Linda Zheng, and Philippe Laramée were employees of Pierre Fabre Group at the time of the conduction of this study. Liam Wilson and Petar Atanasov were employees of Amaris Consulting Ltd., a paid consultant to Pierre Fabre Group to support the conduction of this study.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, data analysis, writing, and review of manuscript: B.M., P.L., L.Z., L.W., P.A. and C.; conduction of desk research and expert interviews: L.W.; expert insight contribution: J.X. and R.G.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No patient data was used in this study and therefore research approval by an Institutional Review Board and informed consent for participation were not required. Research involving expert interview is exempt from ethics approval and informed consent according to Chinese national regulation (涉及人的生物医学研究伦理审查办法).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/20016689.2023.2218633.

References

- [1].Wang L, Wang Z, Ma Q, et al. The development and reform of public health in China from 1949 to 2019. Global Health. 2019;15:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sun J, Lyu S.. The effect of medical insurance on catastrophic health expenditure: evidence from China. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2020;18:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].National Health Commission . 2020年我国卫生健康事业发展统计公报 [2020 Statistical Bulletin on the Development of my country's Health Care]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10743/202107/af8a9c98453c4d9593e07895ae0493c8.shtml. Chinese. 2021. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- [4].National Health Commission . 2015年我国卫生和计划生育事业发展统计公报 [2015 Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Health and Family Planning in my country]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10748/201607/da7575d64fa04670b5f375c87/b6229b0.shtml. Chinese. 2016. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- [5].National Health Commission . 2016年我国卫生和计划生育事业发展统计公报 [2016 Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Health and Family Planning in my country]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10748/201708/d82fa7141696407abb4ef764f3edf095.shtml. Chinese. 2017. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- [6].National Health Commission . 2017年我国卫生健康事业发展统计公报 [2017 Statistical Bulletin on the Development of my country's Health Care]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10743/201806/44e3cdfe11fa4c7f928c879d435b6a18.shtml. Chinese. 2018. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- [7].National Health Commission . 2018年我国卫生健康事业发展统计公报 [2018 Statistical Bulletin on the Development of my country's Health Care]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10748/201905/9b8d52727cf346049de8acce25ffcbd0.shtml. Chinese. 2019. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- [8].National Health Commission . 2019年我国卫生健康事业发展统计公报 [2019 Statistical Bulletin on the Development of my country's Health Care]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10748/202006/ebfe31f24cc145b198dd730603ec4442.shtml. Chinese. 2020. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- [9].Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China . 《中华人民共和国社会保险法》[”Social Insurance Law of the People's Republic of China”]. 2018. Accessed 15 July 2021. Chinese: http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-10/29/content_5647616.htm

- [10].Cinda Securities . Research Report: 医保专题分析报告——2019年各省医保收支分析 [Special Analysis Report on Medical Insurance——Analysis of Provincial Medical Insurance Revenue and Expenditure in 2019]. 2020. . https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202011261433406799_1.pdf?1606420017000.pdf. Chinese. Accessed July 20, 2021.

- [11].National Healthcare Security Administration . 基本医疗保险用药管理暂行办法》已经国家医疗保障局局务会审议通过,现予公布,自2020年9月1日起施行 [The Interim Measures for the Administration of Drugs in Basic Medical Insurance have been reviewed and approved by the executive meeting of the National Medical Security Administration, and are hereby promulgated and will come into force on September 1, 2020]. 2020. http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2020/7/31/art_37_3387.html. Chinese. Accessed February 16, 2022.

- [12].Fang P, Pan Z, Zhang X, et al. The effect of critical illness insurance in China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(27):e11362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Li Y, Duan G, Xiong L. Analysis of the effect of serious illness medical insurance on relieving the economic burden of rural residents in China: a case study in Jinzhai County. BMC Health Serv Res. 20(1):809. 2020 Aug 28. 10.1186/s12913-020-05675-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].National Medical Products Adminstration . NMPA 2020. https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/xxgk/fgwj/bmgzh/20200330180501220.html. Chinese. AccessedAccessed July 20, 2021.

- [15].National Medical Products Administration . 国家药监局关于发布《突破性治疗药物审评工作程序(试行)》等三个文件的公告(2020年第82号)[Announcement of the State Food and Drug Administration on the release of three documents including the ”Working Procedures for the Review of Breakthrough Therapy Drugs (Trial)” (2020 No. 82)]. 2020. https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/yaopin/ypggtg/ypqtgg/20200708151701834.html. Chinese. Accessed July 20, 2021.

- [16].CEWEEKLY . 全国人大代表丁列明国产新药平均审批时间比进口新药慢173天,迫切要求审批效率再提升 [Ding Lieming, deputy to the National People's Congress: The average approval time for domestic new drugs is 173 days slower than that of imported new drugs, and it is urgent to improve the approval efficiency] http://www.ceweekly.cn/2020/0529/299337.shtml. Chinese. 2020. Accessed August 23 2021.

- [17].National Medical Products Administration . 2019年度药品审评报告发布 [Drug Evaluation Report 2019]. Accessed 2020. 20 July . https://www.cde.org.cn/main/news/viewInfoCommon/dabff6d422fa216cb1715de06e2f3c13. Chinese.

- [18].Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China .《关于支持建设博鳌乐城国际医疗旅游先行区的实施方案》[”Implementation Plan on Supporting the Construction of Boao Lecheng International Medical Tourism Pilot Zone”]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-09/17/content_5430452.htm. Chinese. 2019. Accessed July 20, 2021.

- [19].Guangdong provincial government website . 粤港澳大湾区内地临床急需进口港澳药械批件3月正式启用 [The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area clinically urgently needs approval documents for the import of Hong Kong and Macao medical devices to be officially launched in March]. 2022. accessed 19 May 2022. http://mpa.gd.gov.cn/ztzl/dwq/mtbd/content/post_3813247.html. Chinese.

- [20].National Development and Reform Commission . 发展改革委关于公布废止药品价格文件的通知 [Notice of the National Development and Reform Commission on announcing the abolition of drug price documents]. 2015. . http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2015-05/05/content_2857223.htm. Chinese. Accessed March 21, 2022.

- [21].EqualOcean Intelligence . 2021年中国健康险行业创新研究报告 [2021 China Health Insurance Industry Innovation Research Report]. https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202103041468369951_1.pdf?1614864635000.pdf. Chinese. 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021.

- [22].Chen X. 2021. 从惠民保全国生态预判城市定制型商业医疗保险未来发展路径——《城市定制型商业医疗保险(惠民保)知识图谱》解读. 伤害保险,2021年6月 [Judging the future development path of urban customized commercial medical insurance from Huiminbao's national ecology——Interpretation of ”Urban Customized Commercial Medical Insurance (Huiminbao) Knowledge Map”. Injury Insurance, June 2021]. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-SHBX202106003.htm. Chinese. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- [23].IQVIA . 前沿视点View Point,总第42期 [Frontier viewpoint View Point, total issue 42]. https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/china/viewpoints/viewpoint-issue-42.pdf. Chinese. 2019. Accessed March 25, 2022.

- [24].蒋蓉, 陈童, & 邵蓉 . 中美药品患者援助项目实施方式比较研究. 中国卫生政策研究. 2020;13(10):73–11. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hospital Authority . Drug formulary management manual. Chinese: https://www.ha.org.hk/hadf/Portals/0/Docs/HADF_manual_Eng_2018.pdf. 2018. Accessed 15 September 2021.

- [26].Government of Macao . Healthcare Factsheet. 2018. https://www.gcs.gov.mo/files/factsheet/Health_EN.pdf. Accessed: 15 September 2021.

- [27].Health Bureau of Macao . Conde de São Januário General Hospital Guide to Service Procedures. 2021. https://www.ssm.gov.mo/Portal/portal.aspx?lang=en Accessed15th September 2021.

- [28].Trinity Life Sciences . Is the Pricing Discount for Chinese NRDL Inclusion Worth it? NRDL Commercial Impact Assessment. 2021. https://trinitylifesciences.com/is-the-pricing-discount-for-chinese-nrdl-inclusion-worth-it-nrdl-commercial-impact-assessment/. Accessed December 17, 2021.

- [29].National Healthcare Security Administration . 2020. 2020 年国家医保药品目录调整工作方案 [National Medical Insurance Drug Catalog Adjustment Work Plan]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-08/18/5535560/files/10dac7b91fe545da9d49d3e0201bd86c.pdf. Chinese. Accessed January 29, 2021.

- [30].Liu G, Hu S, Wu J, et al. China guidelines for pharmacoeconomic evaluations 2020. Beijing: China Market Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [31].China Central Television . 《焦点访谈》 20201228 医保目录: 如何进 为何出 [”Focus Interview” 20201228 Medical Insurance Directory: How to enter and why to exit]. 2020. https://tv.cctv.com/2020/12/28/VIDECd5xhGRZD7uvKn8yO0GY201228.shtml?spm=C45404.PhRThW8bw020.EToagw7mjlwm.9. Chinese AccessedAccessed Mar 15, 2021.

- [32].The State Council of the People’s Republic of China . 国家医保目录再升级 119种新药以“较高性价比”入围 [The national medical insurance catalog has been upgraded again, and 119 new drugs have been shortlisted with ”higher cost performance”]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-12/28/content_5574069.htm. Chinese. AccessedAccessed March 23, 2022.

- [33].The State Council of the People’s Republic of China . 74种新药进医保 谈判成功率再创新高——解读2021年新版国家医保药品目录 [The success rate of 74 new drugs entering medical insurance negotiations has reached a new high——interpretation of the new version of the National Medical Insurance Drug Catalog in 2021]. 2021. AccessedAccessed March 23, 2022 2022. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-12/04/content_5655779.htm. Chinese. AccessedAccessed March 23, 2022 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.