Abstract

Hydrogen/carbon dioxide (H2/CO2) separation for sustainable energy is in desperate need of reliable membranes at high temperatures. Molecular sieve membranes take their nanopores to differentiate sizes between H2 and CO2 but have compromised at a marked loss of selectivity at high temperatures owing to diffusion activation of CO2. We used molecule gatekeepers that were locked in the cavities of the metal-organic framework membrane to meet this challenge. Ab initio calculations and in situ characterizations demonstrate that the molecule gatekeepers make a notable move at high temperatures to dynamically reshape the sieving apertures as being extremely tight for CO2 and restitute with cool conditions. The H2/CO2 selectivity was improved by an order of magnitude at 513 kelvin (K) relative to that at the ambient temperature.

Molecule gatekeepers in membrane cavities impose a dynamic remediation of sieving apertures in response to temperatures.

INTRODUCTION

Hydrogen (H2) is shaping sustainable future energy worldwide. A prevalent and mature technology is steam reforming of fossil fuels (1, 2), coupled with renewable alcohol sources (e.g., liquid sunshine) as a complement (3). To dilute fears about the safety of H2 storage and transport, a smart station incorporating H2 production immediately linked to a fuel cell power generator is one of hopeful solutions (4). In this pilot station, the water-gas shift (WGS) reaction (473 to 573 K) was implemented to make H2 and CO2, which can be split into two streams (fig. S1): ultrapure H2 to feed a fuel cell (1) and CO2 to be sequestrated for net-zero emissions (5).

Membrane technology is a promising separation alternative (6, 7). In contrast with metallic Pd membranes, which are only feasible at high temperatures (573 to 873 K) to avoid H2 embrittlement (8), molecular sieve membranes, such as zeolite, metal-organic framework (MOF), and two-dimensional laminar membranes, seem more flexible as a “drop-in” separation technique between the WGS reactor and fuel cell. With angstrom-level pores, molecular sieve membranes can frequently discriminate H2 (0.289 nm) and CO2 molecules (0.33 nm) by their kinetic diameters (KD), giving H2 priority (fast gas) over CO2 (slow gas) to pass through their cavities (9–13). The big challenges and intellectual focus are to broaden the operating temperature windows of membranes for high energy efficiency and low equipment costs. First, thermal expansion of crystalline lattices might negatively affect molecular sieving accuracy. Second, CO2 diffusion through membranes must be accelerated more notably by temperature because of its much higher activation energy than H2, which results in a frequent loss of selectivity under hot conditions (9, 14–19), as shown in table S1 and fig. S2. It seems difficult to achieve better separation performances at high temperatures unless temperature could regulate pore size dynamically to prevent CO2 transport. There was an attempt to make the MOF linker reorient toward an aperture at a high temperature, but the effectiveness of this regulation concerning the pore size was limited by the crystalline lattice strain (20). These results prompted us to alter the course. We might need molecules that would be confined into membrane cavities but be allowed freedom of motion at high temperatures. Amid temperature modulation, they can impose a dynamic remediation toward the size of molecular sieving apertures.

As a showcase, we prepared a MOF membrane with a solvent-free vapor processing method based on a solid precursor, simultaneously locking precursor detritus evenly into membrane cavities. With advanced characterization techniques, crystalline lattice refinement modeling, ab initio calculations, and exhaustive gas permeation measurements, it was found that the detritus like gatekeepers in the membrane dynamically reshapes the molecular sieving apertures to prevent CO2 passing through, thus improving H2/CO2 selectivity by an order of magnitude at 513 K compared to that under ambient conditions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis of d-ZIF-L membranes

One-dimensional pore structured MOF-74 (fig. S3), with the formula of Zn18(dhtp)9 in one unit cell, was synthesized by coordinative reaction of divalent zinc ions and 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalatic acid (H4dhtp for short and a deprotonated form as dhtp) at room temperature (R.T.) (21). Using MOF-74 as a metal source, we adopted a hot vapor-solid processing (HVSP) method to synthesize laminar zeolitic imidazolate framework ZIF-L membranes (fig. S4). For comparison, the standard ZIF-L crystal powder was prepared by coordinative reaction of zinc ions and 2-methyl-1-H-imidazole (Hmim for short and a deprotonated form as mim) in water (22). Its topological details and the chemical formula are discussed in fig. S5. First, MOF-74 nanocrystals (~300 nm; figs. S6 and S7) were plugged into voids of the stainless steel net (SSN) substrate to form a closely packed grain layer (fig. S8) and then treated in Hmim vapor at 398 K to achieve one-step solid conversion. Note that lower temperatures (e.g., 348 and 373 K) limit the density of Hmim vapor and prevent the formation of continuous membranes, whereas higher temperatures (e.g., 423 K) can help produce Hmim supramolecule array membranes instead of highly compact MOF membranes (23). At 398 K, MOF-74 nanocrystals tend to fuse after 0.5 hours (fig. S8), but no new phase is detected (fig. S9). After 2 hours, MOF-74 nanocrystals are completely converted to plate-like crystals filling voids of the SSN substrate (fig. S8), which corresponds to a new phase resembling ZIF-L except for a shift of x-ray diffraction (XRD) peaks (002) and (111), as shown in fig. S9. It indicates a major structural distortion of ZIF-L prepared from the HVSP. Altering the duration of HVSP from 2 to 10 hours is one solution to optimize the morphology, size of distorted ZIF-L (d-ZIF-L) crystals, boundary connection between them, and crystal arrangements (fig. S8). These factors heavily influence the compactness and anisotropy of membranes, thus leading to variations in gas permeation results (fig. S10). White light interferometry (WLI) was used to map the three-dimensional morphology for the typical membrane prepared from the HVSP for 6 hours at the millimeter area. The woven net–like surface of the SSN substrate is completely covered by membrane layers, showing a uniform and even landscape (fig. S11). The thickness of this typical membrane is approximately 25 μm, which is reflected by the cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image coupled with the elemental energy-dispersive spectra (EDS) (fig. S12).

Determination of H3dhtp detritus

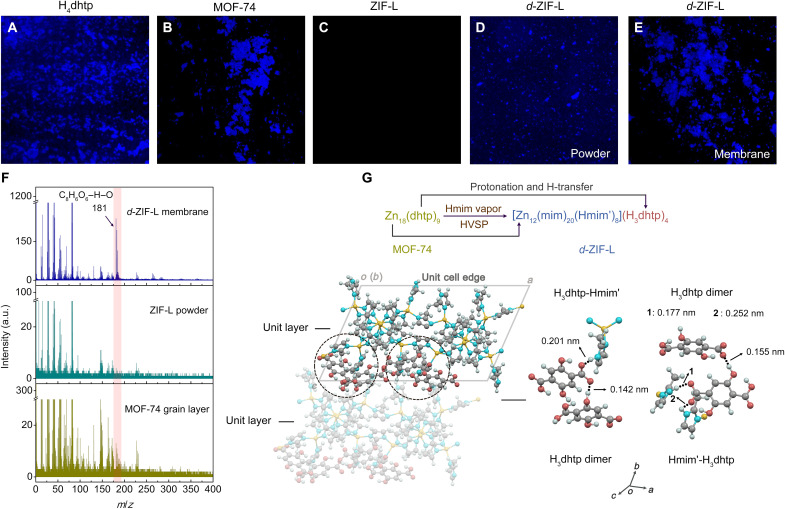

In addition to membranes, the powdery sample was prepared from the HVSP of MOF-74 for 6 hours. As confirmed by XRD (fig. S13), it has the same structure as membranes, resembling ZIF-L with a shift of (002) and (111) diffractions. Pawley refinement of the powder XRD in transmission mode was used to identify a distortion of ZIF-L prepared by HVSP (figs. S14 and S15), which takes a monoclinic AA stacking instead of orthorhombic ABAB stacking along the crystallographic c direction. Its plate-like morphology was also demonstrated by SEM, as distinct from the thin-leaf-like shape for ZIF-L (fig. S16). Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) provides fluorescence imaging of solid-state H4dhtp and dhtp-derived MOF-74 powders (Fig. 1, A and B). Unlike ZIF-L synthesized from solution without fluorescence imaging (Fig. 1C), d-ZIF-L derived from MOF-74 is pale yellow (fig. S17) and fluorescence active (Fig. 1, D and E). Furthermore, the secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) of the d-ZIF-L membrane shows greatly enhanced mass signals with respect to H4dhtp (Fig. 1F), which is the source of the fluorescence and the factor behind the structural distortion. Powdery d-ZIF-L was dissolved in acid to determine its composition by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy. The molar ratios of Zn to H4dhtp and Zn to Hmim are 2.06 and 0.38, respectively, very close to the relevant theoretical values of the MOF-74 precursor and standard ZIF-L (fig. S5). In light of the quantification and Pawley refinement, the chemical formula of the as-synthesized d-ZIF-L is identified to be [Zn12(mim)20(mim′)4(Hmim′)4]·4Hmim*·6H4dhtp in one unit cell. We infer that Hmim molecules in the vapor coordinated competitively with zinc nodes of the MOF-74 precursor amid the HVSP, which forced MOF-74 to take off dhtp linkers and finally resulted in a new phase formation. The dhtp was protonated, with charge-neutral H4dhtp as the dominant precursor detritus remaining in the final d-ZIF-L membrane. Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis shows that the free linkers (Hmim*) and one-third of the H4dhtp detritus can be easily removed from d-ZIF-L by vacuum or thermal treatment (fig. S18), just leaving only the bridge (mim) and monodentate linkers (mim′ and Hmim′) connected to zinc nodes, as well as hydrogen-bonded detritus locked in the interlaminar cavity. Structural optimization using the configurational bias Monte Carlo (CBMC) simulations and density functional theory (DFT) calculations further indicates that two-thirds of the H4dhtp detritus can transfer one proton of the carboxylic groups onto the neighboring monodentate mim′ linkers of d-ZIF-L. Both experimental and simulated evidence suggest a thermodynamically stable composite, namely, [Zn12(mim)20(Hmim′)8](H3dhtp)4 (Fig. 1G). Specifically, four H3dhtp detritus form two dimers in one unit cell. The dimer is not isolated, with one molecule directly linked to Hmim′ through a COO…HN hydrogen bond (Fig. 1G), thus leading to shifts of N─H, C─O, and C═O vibrations in the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra (fig. S19). These interactions also make the detritus firmly locked in the cavity of d-ZIF-L and thus insoluble in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (fig. S20). The simulated pore volume of d-ZIF-L is 0.26 cm3 g−1, very near the experimental value (0.25 cm3 g−1) determined by the CO2 saturation adsorption capacity at 195 K and 100 kPa (fig. S21), which further validates the rationality of the structural optimization. A group of gas adsorption measurements also unveils other structural peculiarities of d-ZIF-L; the detritus seems like struts to block adsorption sites for CO2 at 298 K but inhibits the lattice shrinkage (24) to some extent at cryogenic temperatures (figs. S22 and S23). In addition, d-ZIF-L and ZIF-L display similar zero-coverage adsorption enthalpies for CO2 (31.2 versus 24.2 kJ mol−1) and H2 (2.35 versus 3.00 kJ mol−1), as shown in figs. S24 to S27.

Fig. 1. Determination of H3dhtp detritus in d-ZIF-L from the perspective of experiments and simulation.

(A to F) CLSM images and SIMS signals for d-ZIF-L and a comparable group of counterparts. (G) Structural optimization of d-ZIF-L with H3dhtp detritus locked in the laminar cavity on the basis of CBMC simulations and DFT calculations. Close-up inspection of molecule aggregates (marked in dashed circles) by means of hydrogen bonds is placed on the right. This host-guest system is shown in ball-and-stick models with Zn in yellow, C in gray, N in cyan, O in red, and H in light blue. O···H─O and N─H···O interactions are displayed as dotted lines. a.u., arbitrary units; m/z, mass-charge ratio.

Dynamic remediation of pore limiting diameter

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations were applied to study the thermal response of this host-guest system in a typical heating-cooling cycle (298 K → 423 K → 298 K). Temperatures above 0 K can drive molecular motion and enable H3dhtp detritus dimers to undergo self-adaptive aggregation in the interlaminar cavity of d-ZIF-L. At 298 K, detritus dimers together with the monodentate linkers (Hmim′) dangling between layers define a cushion-like opening to the interlaminar cavity along the b axis, with the widest dimensions measured to be 0.33 nm by 0.35 nm (Fig. 2, A and G). Close-up inspection shows that two detritus dimers (I and II in Fig. 2, A to C) near this opening can flip during a heating-cooling program. Statistics using Python with respect to centroid distances for adjacent detritus imply that molecules of the dimer tend to depart from each other at 423 K (Fig. 2, D and E), most likely one molecule approaching the opening but the other moving oppositely. Accordingly, a heart-like aperture is reshaped with the pore limiting diameter measured for 0.24 nm by 0.33 nm (Fig. 2H). In situ FTIR spectra also reflect this motion of detritus dimers: The redshift of the hydrogen bond fingerprint band between the detritus and d-ZIF-L framework, namely, COO…HN, become notable at higher temperatures (fig. S28). However, centroid distances for adjacent detritus become short again when cooling to 298 K (Fig. 2F), meaning that dimers strive to return back to the original position. The quasi-reversible molecule migration again produces a cushion-like opening that is very near the original one at 298 K (Fig. 2I). In view of detailed computational modeling, we can speculate that the detritus dimers locked in d-ZIF-L like standby gatekeepers to dynamically determine a molecular sieving cutoff, which will contribute to unprecedented H2/CO2 separation properties at high temperatures.

Fig. 2. AIMD simulations of d-ZIF-L in a typical heating-cooling cycle.

(A to C) Modeling and close-up inspection of two detritus dimers defining the opening to the interlaminar cavity. (D to F) Statistic centroid distances for adjacent detritus. (G to I) Modeling of molecular sieving apertures shaped by detritus.

High-temperature H2/CO2 separation

Experimental gas permeation through membranes was conducted as a proof of concept. The d-ZIF-L membranes prepared through HVSP for 6 hours display the optimal average separation factor (SF) of H2/CO2 and gas permeance. Therefore, we focus on d-ZIF-L membranes synthesized under this condition. The optimal membranes yield the H2 permeance of 739 ± 289 gas permeation unit (GPU) and H2/CO2 SF of 179 ± 71 for the equimolar H2/CO2 mixture at 298 K (figs. S10 and S29 and table S2). In addition, from the perspective of the single-component gas permeation, we note a size exclusion behavior of the d-ZIF-L membrane for CO2 but a sharper cutoff for ethane (fig. S30), as the KD of ethane (0.395 nm) is much larger than the dimension of the opening (Fig. 2G). Although most molecular sieve membranes were subject to a drop of H2/CO2 SF with temperature, d-ZIF-L membranes show a contrary trend. When the temperature gradually rises to 423 K (the skeleton of the d-ZIF-L membrane maintains stability as proven by in situ XRD; fig. S31), the permeance of H2 increases steadily with a sharp drop for that of CO2. This marked divergence between the permeances of H2 and CO2 leads to a remarkable improvement in the H2/CO2 SF. One representative demonstration is shown in Fig. 3A, with reproductivity shown in figs. S32 and S33. The deactivation of CO2 permeation at high temperatures is quite understandable given the AIMD prediction that H3dhtp detritus dimers make a marked move at 423 K and reshape the opening as being extremely tight for CO2 (Fig. 2H). Furthermore, six heating-cooling separation cycles through the d-ZIF-L membrane were conducted immediately after a long-term H2/CO2 separation measurement at 423 K (Fig. 3B). When cooling the membrane to the ambient condition, the SF returns in response to the quasi-reversible migration of H3dhtp detritus dimers. As predicted by AIMD (Fig. 2I), the opening nearly recovers to the initial state, concomitant with the detritus dimers back to their balance position at R.T.

Fig. 3. High-temperature H2/CO2 separation through d-ZIF-L membranes.

(A and C) Performances with respect to gas permeances and SF in temperature ranges 298 to 423 K and 453 to 513 K, respectively. (B) The separation durability measurement at 423 K followed by six heating-cooling cycles. (D) Comparison of the d-ZIF-L membrane with other typical molecular sieve membranes in regard to the SF increment upon elevating temperatures above R.T. R.T. generally refers to 293 to 303 K in the literature, as shown in table S1. (E) Piecewise-defined linear Arrhenius plots reflecting the activation, deactivation, and steady-state behaviors of gas permeations. (F) The simulated three-stage membrane separator for producing ultrapure H2. ppm, parts per million.

Beyond our expectation, when the temperature is further elevated to 513 K (very close to the temperature of the industrial gas mixture), H2/CO2 SF through the d-ZIF-L membrane soars up to 989, with the H2 permeance (1330 GPU) nearly doubling that at R.T. (Fig. 3C). At this stage, H2 permeation is thoroughly activated by higher temperatures while CO2 permeation plateaus, which leads to an unprecedented change up to 1017% in the H2/CO2 SF at 513 K, unlike the previously reported trend in a wide range of molecular sieve membranes, including ZIF-L membranes prepared from solution (Fig. 3D and table S1). After high-temperature separation at 423 and 513 K, we find that the intrinsic crystal structure of the d-ZIF-L membrane is undamaged (fig. S34). A piecewise-defined linear Arrhenius equation was used to describe the typical gas permeations of the d-ZIF-L membrane with temperatures (Fig. 3E): The CO2 permeation is deactivated at the moderate temperatures (<423 K) but remains steady at higher temperatures (423 to 513 K). We attribute this hybrid permeation behavior to the detritus dimers, which serve as gatekeepers to constantly modulate the pore limiting diameter. Last, a full chemical process simulation was used to unlock the potential of d-ZIF-L membranes from an industrial viewpoint. A three-stage membrane separator at 513 K can be used to produce ultrapure H2 (CO2 concertation of only 1 part per million) for coupling the fuel cell (Fig. 3F and figs. S35 and S36).

This study concentrates efforts on broadening the operating temperature windows of molecular sieve membranes and paves the way for designing membranes that can be self-adaptive in harsh conditions and respond positively to environmental challenges. As an extension of the concept of this positive host-guest response, “modular design” of MOFs and molecule gatekeepers might be a direction to develop membranes with wide operating windows in relation to moisture and pressure. In addition, given its ultraprecise separation ability, our d-ZIF-L membrane can be coupled with adsorption or ultrapermeable membrane techniques to prepare high-purity H2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Zinc nitrate hexahydrate [Zn(NO3)2·6H2O; 98%], Hmim (98%), and terephthalic acid (H2tp; 98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. 2,5-Dihydroxyterephthalic acid (H4dhtp; >95%) was commercially supplied by Beijing HWRK Chem Co. Ltd. N,N′-dimethylformamide (DMF), triethylamine, ethanol, and methanol were supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. Deuterium DMSO (DMSO-D6) was provided by Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co. Ltd. SSN substrates (3AL3; thickness: 0.37 mm) were purchased from Bekaert (China) Co., consisting of top, intermediate, and bottom layers with average pore sizes of 6.5, 2.0, and 6.5 μm, respectively.

Preparations

Preparation of MOF-74 nanocrystals

MOF-74 nanocrystals were synthesized according to the previous literature (21). A total of 5.05 mmol of H4dhtp and 15.6 mmol of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved in the mixed solvents composed of 400 ml of DMF, 27 ml of ethanol, and 27 ml of water. The mixture was thoroughly stirred under a N2 atmosphere for 12 hours after a quick injection of triethylamine (5 ml). The product was collected by centrifugation and washed with DMF (round 1) and ethanol (round 2) three times, respectively. Last, the product was dried in an oven at 333 K for 12 hours.

Pretreatment of substrates

SSN substrates were cut into small pieces (2 cm by 2 cm), submerged in DMF at R.T. for 24 hours to remove impurities, and then dried at 333 K for 48 hours.

Preparation of d-ZIF-L membranes by HVSP

The procedure for HVSP is shown in fig. S4. The MOF-74 nanocrystal powder through a 200-mesh screen was first plugged into the SSN substrate by hand-scrubbing (~1.18 mg cm−2), forming a uniform layer of closely packed grains on the substrate surface. Then, the SSN substrate with the MOF-74 grain layer was cautiously cut into an 18-mm-diameter disk and fixed in a homemade Teflon holder, facing down the Hmim powder (~3.00 g) that was placed at the bottom of the stainless steel autoclave (100 ml). Then, the sealed autoclave was heated at 398 K for a period of time and cooled down naturally in an oven (DGG-9070GD, Shanghai Sumsung Laboratory Instrument).

Preparation of powdery d-ZIF-L from MOF-74

Powdery d-ZIF-L was synthesized from MOF-74 by a modified HVSP method. To avoid anisotropic diffusion of the Hmim vapor through the MOF-74 powder, 0.300 g of the MOF-74 nanocrystal powder and 3.00 g of the Hmim solid were ground and mixed well in an agate mortar in advance. Then, the mixture was transferred to a stainless steel autoclave (100 ml). The sealed autoclave was heated at 398 K for 6 hours and cooled down naturally in an oven. The excess of the Hmim reactant was completely washed with methanol at least three times. The product was collected by centrifugation and dried in an oven at 333 K for 12 hours.

Preparation of powdery ZIF-L from solution

The powdery ZIF-L was synthesized by coordinative reaction of divalent Zn ions and Hmim linkers in water according to the previous literature (22). First, 16.1 mmol of Hmim and 1.99 mmol of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved in 40 ml of water. Then, the two solutions were mixed at R.T. and stirred for 4 hours. The product was collected by centrifugation, washed with water three times, and dried in an oven at 333 K for 12 hours.

Characterizations

Powder XRD measurements in reflection mode

XRD measurements in reflection mode at R.T. were performed on a Rigaku D/MAX 2500/PC instrument with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm at 40 kV and 200 mA). The data were recorded from 2° to 50° with a scan speed of 5° min−1.

Powder XRD measurements in transmittance mode

First, the microcrystalline sample of d-ZIF-L was fixed in a specific holder, and the high-quality powder XRD in transmittance mode was collected on an Empyrean-100 instrument with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm at 40 kV and 40 mA). The 2θ range was 2° to 80° with a 2θ step of 0.039° and a scan speed of 45.1350 s per step.

In situ XRD measurements in reflection mode

High-temperature in situ XRD patterns were obtained on a Rigaku D/MAX 2500/PC instrument. The sample was heated from 298 to 423 K with a ramp rate of 1 K min−1 and swept by an equimolar H2/CO2 mixture at a flow rate of 10 ml min−1. The patterns were collected from 2° to 50° with a scan speed of 5° min−1. Cryogenic-temperature in situ XRD patterns were obtained on an Empyrean-100 instrument. The patterns were collected with a 2θ step of 0.026° and a scan speed of 296.5650 s per step.

Dynamic light scattering measurements

Number-averaged particle size distributions were collected using a dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument (Zetasizer Nano ZS90, Malvern). Approximately 2 mg of as-prepared MOF-74 nanocrystals without drying were redispersed into 20 ml of methanol with the aid of a horn sonicator for the DLS analysis.

SEM and EDS analysis

The microscopic morphology of the membranes was observed by SEM (JSM-7900F, Japan Electronics) with an acceleration voltage of 2 kV. To avoid electron accumulation, Pt nanoparticles were sputter-coated on the skin layer of the membrane and powder sample before the experiment. EDS was performed to map the element distribution through the cross section of the d-ZIF-L membrane.

WLI analysis

The surface morphology of the SSN substrate and d-ZIF-L membrane was probed by the nondestructive WLI technique at an interferometer with a 3D surface profiler (Micro XAM-3D, KLA-ADE, USA).

CLSM analysis

CLSM (CSU-W1, Andorra) provided fluorescence imaging of samples in a spinning disk field scanning confocal system. The excitation wavelength of the laser was 405 nm. The powder samples were evenly spread on the slide during the test. The disk-like membrane supported by the nontransparent SSN substrate was not suitable for direct operation in the apparatus. Before imaging, we scratched the membrane surface carefully, collected the powder chips, and then spread them on the slide.

SIMS analysis

High-resolution SIMS of samples was performed using a spectrometer (Surface Seer-I, Kore Tech, UK) equipped with a liquid Au ion gun. Secondary ions were generated as a result of the impact of the pulsed primary Au2+ ion beam (voltage of 25 kV and current of 4 μA) on the sample surface. The disk-like membrane can be directly fixed in the device for surface analysis. The mass signals arise from the analysis area of 500 μm by 500 μm on the sample surface. The acquisition time was 4 min.

FTIR analysis

The chemical structures of the samples were characterized by ex situ FTIR (Nicolet iS50 spectrometer, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode. All samples were pretreated at 373 K in a vacuum oven for 48 hours to remove adsorbed water before measurements. The spectra were collected from 400 to 4000 cm−1 under 32 scans and 4-cm−1 resolution. In situ infrared spectra measurements in the ATR mode were performed on a VERTEX 80-V infrared spectrometer. The heating rate was set as 10 K min−1 from 303 to 513 K. The spectra were collected once a minute.

1H NMR spectra analysis

1H NMR spectra were obtained on an NMR spectrometer (AVAVCE III HD, 700 MHz, Bruker). The solids were dissolved in DCl/DMSO-d6 mixed solvents for the analysis of compositions or soaked in DMSO-d6 for extraction of the H4dhtp detritus. In each measurement, H2tp as an internal standard component was added into the solution for quantification.

ICP-OES analysis

The contents of Zn ions in the acidolysis solution were determined through ICP-OES on a Shimadzu ICPS-8100 (160 to 850 nm, 1.8 kW, 27.12 MHz).

TG analysis

TG analysis of powdery ZIF-L and d-ZIF-L was conducted under a N2 flow (10 ml min−1) with a heating rate of 10 K min−1 on a PerkinElmer instrument (Pyris diamond TG/DTA).

Gas adsorption experiments

Gas adsorption at 0 to 110 kPa was conducted on a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 Plus physisorption analyzer.

Calculation of adsorption enthalpies

Virial equation (Eq. 1) was frequently used to describe the adsorption isotherms of H2 and CO2 at a specific temperature. On the basis of experimental adsorption points at two different temperatures, viral isotherms can be fitted, and the value of coefficients ai can be determined

| (1) |

Here, p is the pressure expressed in Pa, N is the amount absorbed in mol g−1, T is the temperature in K, ai and bj are virial coefficients, and m and n represent the number of coefficients required to adequately describe the isotherms. The values of the virial coefficients a0 through am were then used to calculate adsorption enthalpies (ΔH) using Eq. 2

| (2) |

When N = 0, Eq. 2 was converted into Eq. 3 to calculate zero-coverage adsorption enthalpies (ΔH0)

| (3) |

Gas permeation tests

Gas separation

H2/CO2 gas separation performances were measured with the Wicke-Kallenbach method. The membranes were sealed in a homemade stainless steel permeation cell with silicone rubber O-rings. The ambient temperature of the membranes was controlled using an external mini oven. An equimolar binary gas mixture was introduced into the permeation cell with a total flow rate constant at 100 ml min−1 at 100 kPa. Ar (99.99%) was used as the sweep gas. A gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890A) equipped with a packed column (TDX-01, Analytical Technology, Lanzhou, China), and a highly sensitive thermal conductivity detector was used for online monitoring of the concentration of penetrants. The gas permeance (Pi) and SF (α) were determined using Eqs. 4 and 5, respectively

| (4) |

where Pi is the gas permeance (mol m−2 s−1 Pa−1) of component i, Ni is the volume flow rate (mol s−1) of the gas under standard conditions, S is the effective membrane area (m2), and ΔPi is the transmembrane pressure difference (Pa) of component i. Here, gas permeance is given in units of GPU

The SF was calculated according to the following equation (Eq. 5)

| (5) |

where Pi and Pj represent the permeance of component i and component j in mixed gas separation, respectively.

Single-component gas permeation

The single-component gas permeations of H2, CO2, CH4, and C2H6 were conducted at 298 K with a constant feed flow rate of 100 ml min−1. A gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890B) equipped with a capillary column (HP-PLOT Al2O3 KCl, Agilent) and a highly sensitive flame ionization detector was used for online monitoring of the concentration of alkanes. The ideal selectivity was also determined by the ratio of gas permeances (Eq. 5).

Structural determination and simulation of d-ZIF-L

Structural refinement based on the powder XRD pattern

The crystal structure of d-ZIF-L was determined from the combination of Pawley refinement based on high-quality powder XRD patterns in transmittance mode and multiple computational simulations and calculations (including CBMC simulations and DFT calculations) performed using the Materials Studio 5.5 Package. The detailed process was as follows: High-quality powder XRD data of d-ZIF-L were collected in transmittance mode. After that, indexing was performed using the Reflex module. The pattern was well indexed in a P-lattice monoclinic space group rather than the C-lattice orthogonal space group of standard ZIF-L. Then, Pawley refinement was performed in the 2θ range of 3° to 80° on the unit cell parameters, zero point, and background terms with the Pseudo-Voigt profile function and Berar-Baldinozzi asymmetry correction function and yielded the following cell parameters: P21/m, a = 26.79 (2) Å, b = 13.84 (1) Å, c = 16.67 (1) Å, Rp = 4.10%, and Rwp = 7.37%. Considering that d-ZIF-L and ZIF-L have similar powder XRD patterns and the contractive c axis of d-ZIF-L was determined from the Pawley refinement, a neutral layered structure in an AA stacking mode rather than ABAB stacking mode was built for d-ZIF-L, with the composition of [Zn12(mim)20(mim′)4(Hmim′)4] in one unit cell [mim stands for the bridge linker and mim′ (or Hmim′ for charge balance) stands for the monodentate linker]. Nonetheless, the layer is twofold disordered in the P21/m space group, which is difficult for further Rietveld refinements and calculations. Therefore, we built an ordered structure with the P1 space group with the same parameters as those of P21/m and carried out periodic DFT calculations to optimize the single-layered structure mode, which was used for further simulations and calculations. Note that randomly distributed free linkers (Hmim*) were not included in d-ZIF-L for simplification of the model. Because the experimental TG analysis suggests that the free linkers can be easily removed from d-ZIF-L by vacuum or thermal treatment, this simplification is reasonable for further high-temperature structural calculations.

Structural optimization of d-ZIF-L with Hxdhtp detritus

Considering that the molar ratio of Zn to dhtp-based detritus in d-ZIF-L was 2:1, we loaded six H4dhtp into one unit cell of d-ZIF-L by CBMC and performed DFT calculations to further optimize the host-guest structure. Partial protons of H4dhtp can transfer onto the exposed N atom of mim′ to generate a cationic coordination framework [Zn12(mim)20(Hmim′)8]4+, with four deprotonated H3dhtp− (per uni -cell) interacting with the monodentate Hmim′ units through hydrogen bonds and two additionally charge neutral H4dhtp remaining in the interlaminar cavity, namely, [Zn12(mim)20(Hmim′)8](H3dhtp)4·2H4dhtp in one unit cell. Furthermore, experimental TG analysis (fig. S18) showed that one-third of the dhtp-based detritus was easily removed by vacuum or thermal treatment, which corresponded exactly to the neutral H4dhtp weakly interacting with d-ZIF-L, giving a stable chemical formula of [Zn12(mim)20(Hmim′)8](H3dhtp)4. Considering the above analysis, we further optimized the structure by using periodic DFT calculations. In addition, the above calculations can be used to explain why only partial Hxdhtp detritus rather than all Hxdhtp can be removed after vacuum or thermal treatment. The optimized structure had a pore volume of 0.26 cm3 g−1, consistent with the experimental data (0.25 cm3 g−1), which indicated that the optimized structure should be right and appropriate for later computational simulations.

CBMC simulations were performed with the fixed loading and fixed pressure task in the sorption module. The simulation box consisted of one unit cell, and the Metropolis method based on the universal force field was used. Mulliken and electrostatic potential charges calculated from DFT were adopted for the host frameworks and the guests, respectively. The cutoff radius was chosen to be 18.5 Å for the Lennard-Jones interactions, and the electrostatic interactions and van der Waals interactions were handled using Ewald and atom-based summation methods, respectively. All equilibration steps and production steps were 5 × 106. Periodic DFT calculations were performed using the Dmol3 module. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Emzerhof (PBE) functional and the double numerical plus d-functions basis set and DFT semicore pseudopots were used. The energy, gradient, and displacement convergence criteria were set as 2 × 10−5 Ha, 4 × 10−3 Å, and 5 × 10−3 Å, respectively.

Structural calculation of d-ZIF-L at higher temperatures

Because the optimized structure by conventional DFT was obtained at 0 K and 0 bar, which is not appropriate for analyzing pore changes during real conditions (≥298 K), we used AIMD simulations to obtain structures at different temperatures (during a typical heating-cooling cycle 298 K → 423 K → 298 K). The AIMD simulations were performed using DFT within the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (25). For the calculations, the PBE-GGA was used for the exchange-correlation interactions (26). The kinetic energy cutoff of the plane wave basis was set as 450 eV. The canonical ensemble (NVT) with a Nosé thermostat was used during the simulations (27). The simulations were carried out at 298 and 423 K with a time step of 1 fs. The Γ-point was sampled in the Brillouin zone. After 30 ps of the simulation, the evolution of the system was analyzed by the movement of the atoms.

Chemical process simulation

Aspen Plus v7.2 software was used to conduct a chemical process simulation for membrane-based H2/CO2 separation. The feed of the gas mixture (molar ratio, H2/CO2 = 1:1) was at a volume of 10 N m3 hours−1 (N stands for 1 normal atmosphere pressure and 273 K).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 22090060 (to W.Y. and X.-M.C.), National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 21721004 (to W.Y.), National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 21978283 (to Y.B.), National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 22071272 (to D.-D.Z.), and Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS grant 2021179 (to Y.B.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Y.B. and W.Y. Methodology: Y.B., M.Z., D.-D.Z., P.C., Y.W., Z.H., Y.L., and M.-Y.Z. Investigation: Y.B. and M.Z. Funding acquisition: W.Y., X.-M.C., Y.B., and D.-D.Z. Supervision: Y.B. and W.Y. Writing—original draft: Y.B. Writing—review and editing: W.Y., D.-D.Z., and X.-M.C.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S36

Tables S1 and S2

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.H. Nazir, C. Louis, S. Jose, J. Prakash, N. Muthuswamy, M. E. M. Buan, C. Flox, S. Chavan, X. Shi, P. Kauranen, T. Kallio, G. Maia, K. Tammeveski, N. Lymperopoulos, E. Carcadea, E. Veziroglu, A. Iranzo, A. M. Kannan, Is the H2 economy realizable in the foreseeable future? Part I: H2 production methods. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 45, 13777–13788 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.N. W. Ockwig, T. M. Nenoff, Membranes for hydrogen separation. Chem. Rev. 107, 4078–4110 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.C. F. Shih, T. Zhang, J. Li, C. Bai, Powering the future with liquid sunshine. Joule 2, 1925–1949 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.K. Jiao, J. Xuan, Q. Du, Z. Bao, B. Xie, B. Wang, Y. Zhao, L. Fan, H. Wang, Z. Hou, S. Huo, N. P. Brandon, Y. Yin, M. D. Guiver, Designing the next generation of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. Nature 595, 361–369 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.H. C. Lau, S. Ramakrishna, K. Zhang, A. V. Radhamani, The role of carbon capture and storage in the energy transition. Energy Fuel 35, 7364–7386 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.D. S. Sholl, R. P. Lively, Seven chemical separations to change the world. Nature 532, 435–437 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.H. B. Park, J. Kamcev, L. M. Robeson, M. Elimelech, B. D. Freeman, Maximizing the right stuff: The trade-off between membrane permeability and selectivity. Science 356, eaab0530 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.S. Adhikari, S. Fernando, Hydrogen membrane separation techniques. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 45, 875–881 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 9.H. Li, Z. Song, X. Zhang, Y. Huang, S. Li, Y. Mao, J. P. Harry, Y. Bao, M. Yu, Ultrathin, molecular-sieving graphene oxide membranes for selective hydrogen separation. Science 342, 95–98 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.J. Hou, H. Zhang, G. P. Simon, H. Wang, Polycrystalline advanced microporous framework membranes for efficient separation of small molecules and ions. Adv. Mater. 32, 1902009 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.C. Zhang, R. P. Lively, K. Zhang, J. R. Johnson, O. Karvan, W. J. Koros, Unexpected molecular sieving properties of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 2130–2134 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.K. Eum, M. Hayashi, M. D. De Mello, F. Xue, H. T. Kwon, M. Tsapatsis, ZIF-8 membrane separation performance tuning by vapor phase ligand treatment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 16390–16394 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.M. Kanezashi, Y. S. Lin, Gas permeation and diffusion characteristics of MFI-type zeolite membranes at high temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 3767–3774 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 14.A. W. Thornton, T. Hilder, A. J. Hill, J. M. Hill, Predicting gas diffusion regime within pores of different size, shape and composition. J. Membr. Sci. 336, 101–108 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Y. Peng, Y. Li, Y. Ban, H. Jin, W. Jiao, X. Liu, W. Yang, Metal-organic framework nanosheets as building blocks for molecular sieving membranes. Science 346, 1356–1359 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Y. Sun, C. Song, X. Guo, Y. Liu, Concurrent manipulation of out-of-plane and regional in-plane orientations of NH2-UiO-66 membranes with significantly reduced anisotropic grain boundary and superior H2/CO2 separation performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 4494–4500 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.J. Hou, X. Hong, S. Zhou, Y. Wei, H. Wang, Solvent-free route for metal–organic framework membranes growth aiming for efficient gas separation. AIChE J. 65, 712–722 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 18.F. Zhang, X. Zou, X. Gao, S. Fan, F. Sun, H. Ren, G. Zhu, Hydrogen selective NH2-MIL-53(Al) MOF membranes with high permeability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 3583–3590 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.L. Ding, Y. Wei, L. Li, T. Zhang, H. Wang, J. Xue, L. –X. Ding, S. Wang, J. Caro, Y. Gogotsi, MXene molecular sieving membranes for highly efficient gas separation. Nat. Commun. 9, 155 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.X. Wang, C. Chi, K. Zhang, Y. Qian, K. M. Gupta, Z. Kang, J. Jiang, D. Zhao, Reversed thermo-switchable molecular sieving membranes composed of two-dimensional metal-organic nanosheets for gas separation. Nat. Commun. 8, 14460 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.J. E. Bachman, Z. P. Smith, T. Li, T. Xu, J. R. Long, Enhanced ethylene separation and plasticization resistance in polymer membranes incorporating metal-organic framework nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 15, 845–849 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.R. Chen, J. Yao, Q. Gu, S. Smeets, C. Baerlocher, H. Gu, D. Zhu, W. Morris, O. M. Yaghi, H. Wang, A two-dimensional zeolitic imidazolate framework with a cushion-shaped cavity for CO2 adsorption. Chem. Commun. 49, 9500–9502 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. Zhao, Y. Ban, K. Yang, Y. Zhou, N. Cao, Y. Wang, W. Yang, A highly selective supramolecule array membrane made of zero-dimensional molecules for gas separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 20977–20983 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.J. Hao, D. J. Babu, Q. Liu, P. A. Schouwink, M. Asgari, W. L. Queen, K. V. Agrawal, Mechanistic study on thermally induced lattice stiffening of ZIF-8. Chem. Mater. 33, 4035–4044 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.G. Kresse, J. Furthmüller, Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.J. P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzerhof, Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.M. Tuckerman, B. J. Berne, G. J. Martyna, Reversible multiple time scale molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 1990–2001 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 28.S. R. Caskey, A. G. Wong-Foy, A. J. Matzger, Dramatic tuning of carbon dioxide uptake via metal substitution in a coordination polymer with cylindrical pores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 10870–10871 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.T. M. McDonald, W. Ram Lee, J. A. Mason, B. M. Wiers, C. S. Hong, J. R. Long, Capture of carbon dioxide from air and flue gas in the alkylamine appended metal-organic framework mmen-Mg2(dobpdc). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7056–7065 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.R. L. Siegelman, T. M. McDonald, M. I. Gonzalez, J. D. Martell, P. J. Milner, J. A. Mason, A. H. Berger, A. S. Bhown, J. R. Long, Controlling cooperative CO2 adsorption in diamine-appended Mg2(dobpdc) metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10526–10538 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Y. Lin, C. Kong, Q. Zhang, L. Chen, Metal-organic frameworks for carbon dioxide capture and methane storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1601296 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Z. X. Low, J. Yao, Q. Liu, M. He, Z. Wang, A. K. Suresh, J. Bellare, H. Wang, Crystal transformation in zeolitic-imidazolate framework. Cryst. Growth Des. 14, 6589–6598 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 33.R. P. Kavali, J. Tonannavar, J. Bhovi, J. Y., Study of O H···O bonded-cyclic dimer for 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalic acid as aided by MD, DFT calculations and IR, Raman, NMR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 1264, 133174 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 34.J. Liu, Y. Wang, H. Guo, S. Fan, A novel heterogeneous MOF membrane MIL-121/118 with selectivity towards hydrogen. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 111, 107637 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 35.C. Chi, X. Wang, Y. Peng, Y. Qian, Z. Hu, J. Dong, D. Zhao, Facile preparation of graphene oxide membranes for gas separation. Chem. Mater. 28, 2921–2927 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 36.K. Yang, S. Hu, Y. Ban, Y. Zhou, N. Cao, M. Zhao, Y. Xiao, W. Li, W. Yang, ZIF-L membrane with a membrane-interlocked-support composite architecture for H2/CO2 separation. Sci. Bull. 66, 1869–1876 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Y. Peng, Y. Li, Y. Ban, W. Yang, Two-dimensional metal-organic framework nanosheets for membrane-based gas separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 9757–9761 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.X. Wang, C. Chi, J. Tao, Y. Peng, S. Ying, Y. Qian, J. Dong, Z. Hu, Y. Gu, D. Zhao, Improving the hydrogen selectivity of graphene oxide membranes by reducing non-selective pores with intergrown ZIF-8 crystals. Chem. Commun. 52, 8087–8090 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Z. Li, P. Yang, S. Yan, Q. Fang, M. Xue, S. Qiu, A robust zeolitic imidazolate framework membrane with high H2/CO2 separation performance under hydrothermal conditions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 15748–15755 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.J. Hao, D. J. Babu, Q. Liu, H. Y. Chi, C. Lu, Y. Liu, K. V. Agrawal, Synthesis of high-performance polycrystalline metal-organic framework membranes at room temperature in a few minutes. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 7633–7640 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 41.S. Wang, J. Liu, B. Pulido, Y. Li, D. Mahalingam, S. P. Nunes, Oriented zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF) nanocrystal films for molecular separation membranes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 3839–3846 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Z. Zhou, C. Wu, B. Zhang, ZIF-67 membranes synthesized on α-Al2O3-plate-supported cobalt nanosheets with amine modification for enhanced H2/CO2 permselectivity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 3182–3188 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.B. Ghalei, K. Wakimoto, C. Y. Wu, A. P. Isfahani, T. Yamamoto, K. Sakurai, M. Higuchi, B. K. Chang, S. Kitagawa, E. Sivaniah, Rational tuning of zirconium metal-organic framework membranes for hydrogen purification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 19034–19040 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Y. Li, X. Zhang, X. Chen, K. Tang, Q. Meng, C. Shen, G. Zhang, Zeolite imidazolate framework membranes on polymeric substrates modified with poly(vinyl alcohol) and alginate composite hydrogels. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 12605–12612 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.H. Li, J. Hou, T. D. Bennett, J. Liu, Y. Zhang, Templated growth of vertically aligned 2D metal-organic framework nanosheets. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 5811–5818 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 46.P. Nian, H. Liu, X. Zhang, Bottom-up fabrication of two-dimensional Co-based zeolitic imidazolate framework tubular membranes consisting of nanosheets by vapor phase transformation of Co-based gel for H2/CO2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 573, 200–209 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.P. Yang, Z. Li, Z. Gao, M. Song, J. Zhou, Q. Fang, M. Xue, S. Qiu, Solvent-free crystallization of zeolitic imidazolate framework membrane via layer-by-layer deposition. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 4158–4164 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 48.C. Liu, Y. Jiang, C. Zhou, J. Caro, A. Huang, Photo-switchable smart metal-organic framework membranes with tunable and enhanced molecular sieving performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 24949–24955 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Y. Li, H. Liu, H. Wang, J. Qiu, X. Zhang, GO-guided direct growth of highly oriented metal-organic framework nanosheet membranes for H2/CO2 separation. Chem. Sci. 9, 4132–4141 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.P. Nian, Y. Li, X. Zhang, Y. Cao, H. Liu, X. Zhang, ZnO nanorod-induced heteroepitaxial growth of SOD type Co-based zeolitic imidazolate framework membranes for H2 separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 4151–4160 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.S. Friebe, B. Geppert, F. Steinbach, J. Caro, Metal–organic framework UiO-66 layer: A highly oriented membrane with good selectivity and hydrogen permeance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 12878–12885 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.S. Zhang, Z. Wang, H. Ren, F. Zhang, J. Jin, Nanoporous film-mediated growth of ultrathin and continuous metal–organic framework membranes for high-performance hydrogen separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 1962–1966 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 53.S. Hurrle, S. Friebe, J. Wohlgemuth, C. Wöll, J. Caro, L. Heinke, Sprayable, large-area metal-organic framework films and membranes of varying thickness. Chem. A Eur. J. 23, 2294–2298 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.A. Knebel, S. Friebe, N. C. Bigall, M. Benzaqui, C. Serre, J. Caro, Comparative study of MIL-96(Al) as continuous metal-organic frameworks layer and mixed-matrix membrane. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 7536–7544 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Y. Sun, F. Yang, Q. Wei, N. Wang, X. Qin, S. Zhang, B. Wang, Z. Nie, S. Ji, H. Yan, J.-R. Li, Oriented nano-microstructure-assisted controllable fabrication of metal-organic framework membranes on nickel foam. Adv. Mater. 28, 2374–2381 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Q. Li, G. Liu, K. Huang, J. Duan, W. Jin, Preparation and characterization of Ni2(mal)2(bpy) homochiral MOF membrane. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 11, 60–69 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Y. Sun, Y. Liu, J. Caro, X. Guo, C. Song, Y. Liu, In-plane epitaxial growth of highly c‐oriented NH2-MIL-125(Ti) membranes with superior H2/CO2 selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 16088–16093 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Y. Liu, N. Wang, J. H. Pan, F. Steinbach, J. Caro, In situ synthesis of MOF membranes on ZnAl-CO3 LDH buffer layer-modified substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14353–14356 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.H. Guo, G. Zhu, I. J. Hewitt, S. Qiu, “Twin copper source” growth of metal-organic framework membrane: Cu3(BTC)2 with high permeability and selectivity for recycling H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 1646–1647 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S36

Tables S1 and S2

References